Abstract

The association between the ratio of uric acid relative to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (UHR) and abdominal aortic calcification (AAC), and the mediating effect of diabetes, is not fully understood. The ultimate assessment encompassed 2,731 participants (average age: 58.64 years; 51.59% women) from the 2013–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The presence of abdominal aortic calcification (AAC) was evaluated employing Kauppila’s (1997) semi-quantitative scoring system, with the results expressed in Kauppila semi-quantitative units. In the analysis, AAC scores were treated as continuous variables. AAC was also categorised as a binary variable, with non-zero scores assigned a value of 1 and zero scores assigned a value of 0. Similarly, SAAC was categorised as a binary variable, with scores greater than to 6 assigned a value of 1 and scores less than or equal to 6 assigned a value of 0. The present study employed weighted multiple logistic regression and linear regression analysis to investigate the association between UHR and AAC scores, as well as between AAC and SAAC. Subgroup and interaction analyses were conducted in order to investigate whether these associations varied by different confounders. The present study employed causal mediation analysis to assess the mediating effect of diabetes between UHR and abdominal aortic calcification (AAC). Sensitivity analysis was performed to determine the robustness of the association results between UHR and AAC. A one-unit rise in the log2-transformed UHR led to a 0.53 increase in the AAC scores [β(95% confidence interval, CI): 0.53 (0.31, 0.75)] and a 43% higher risk of AAC [odds ratio (OR) (95% CI): 1.43 (1.22, 1.67)], and the risk of SAAC increased by 60% [OR (95% CI): 1.60 (1.21, 2.12)]. The findings of this study indicate that diabetes mediated 7.5% of the association between UHR and AAC scores, and 14% of the association between UHR and SAAC risk. This study found significant positive correlations between UHR and AAC scores, and between UHR and the risk of AAC and SAAC. It also found that diabetes partially mediated the association between UHR and AAC scores, as well as between UHR and SAAC. These results imply that UHR could be a useful clinical biomarker for predicting AAC risk and identifying AAC and SAAC, while diabetes partly explains this association.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arterial calcification (AC) is defined as the pathological deposition of calcium salts in arterial walls1,2,3. As a hallmark of atherosclerosis, abdominal aortic calcification (AAC) has been observed to increase with age4,5 and is closely associated with the development of cardiovascular diseases6,7. Research has indicated that in excess of 50% of the elderly population (aged 60 and above) exhibit varying degrees of aortic calcification8. In diabetic patients, the likelihood and severity of coronary artery disease is higher and more severe9.AAC has been identified as an independent predictor of cardiovascular events and is closely associated with all-cause mortality10,11. On a global scale, cardiovascular diseases are responsible for approximately one-third of all deaths12,13. In the context of an ageing population and the increasing prevalence of metabolic diseases, the early detection and intervention of AAC have emerged as pivotal strategies for mitigating the impact of cardiovascular diseases.

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) plays a key protective role in cardiovascular health by promoting cholesterol reverse transport and reducing plaque formation14, but its dysfunction (characterized by impaired cholesterol efflux capacity) exacerbates the progression of atherosclerosis15, and such dysfunction is commonly observed in metabolic disorders such as diabetes16,17; In fact, diabetes has become a well-established risk factor for vascular calcification due to its pro-inflammatory and pro-calcification effects on vascular smooth muscle cells18,19, and elevated serum uric acid levels are also associated with pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and vascular calcification20,21; Additionally, lipid metabolism is closely related to glucose homeostasis22, and dyslipidemia exacerbates insulin resistance leading to diabetes23,24, creating a vicious cycle that increases cardiovascular risk. These metabolic abnormalities highlight the need for integrated biomarkers that comprehensively reflect multiple pathways of early vascular damage; In this context, the uric acid-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (UHR) emerges as a novel composite indicator that captures both oxidative stress and metabolic dysfunction25,26,27. Compared to traditional imaging modalities such as CT, which are limited by cost, radiation exposure, and accessibility for population screening28,29, UHR offers a simple, cost-effective, and scalable method for assessing glucose and lipid metabolic disorders in vivo30; Although previous studies have identified associations between UHR and broader cardiovascular risk factors30,31, the specific relationship between UHR and AAC (as an early marker of vascular calcification) has not been thoroughly explored, nor has the potential mediating role of diabetes in this relationship been elucidated.

This study is the first to use data from the 2013–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to examine the relationship between UHR and AAC using cross-sectional analysis. A causal mediation analysis was then used to explore the impact of diabetes on this association further. The aim of this study is to provide new insights into the association between UHR and AAC in individuals aged 40 years and older, as well as the potential mediating role of diabetes.

Methods

Study population

The research data were sourced from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), gathered from 2013 to 2014, adhering to the ethical guidelines set forth in the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. This NHANES database is a population-based survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) in the U.S, and the NCHS Ethics Review Board provided support for this study. During the period under investigation, the study sample comprised 10,175 subjects, of whom 3,140 had valid AAC scores and 3,016 had undergone serum uric acid and HDL testing.The study excluded participants with missing data on personal marital status, education level, PIR, smoking, BMI, serum calcium, and questionnaire surveys of diabetes and hypertension (total = 285). The final study population comprised 2,731 subjects aged 40 and over who did not have any missing data, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (UHR)

The ratio of uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (UHR) is calculated from a blood specimen that is subjected to rigorous laboratory testing following a standardised sampling protocol to ensure validity and comparability of data. The DxC 800 employs a timed endpoint technique to determine uric acid levels in serum, plasma, or urine. The procedure for assessing high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) entails the elimination of non-HDL-C by adding magnesium/dextran sulfate, and then adding reagent 2 to convert HDL-C to a measurable form. The concentration of HDL is then measured photometrically by the catalytic reaction of PEG cholesterol oxidase and peroxidase to produce violet/blue chromogen. The UHR is calculated based on an accurate formula: UHR = UA (mg/dL)/HDL (mg/dL)32,33, which NHANES employs to evaluate the inflammatory and metabolic conditions of participants.

Abdominal aortic calcification

Abdominal aortic calcification (AAC) was quantified using the Kauppila scoring system based on lateral spine images obtained by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). The Kauppila AAC scoring system divides the aortic wall into eight anatomical segments, corresponding to the anterior and posterior regions of the lumbar vertebrae L1-L4. Each segment is graded on a scale of 0–3 according to the severity of calcification, with a cumulative score ranging from 0 to 24, which is proportional to the atherosclerotic burden. In this study, a score of 0 was defined as no AAC, otherwise it was defined as having AAC; an AAC scores of more than 6 was considered to have severe abdominal aortic calcification (SAAC). The calculation method and details of this scoring system can be found on the official CDC NHANES website (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Data/Nhanes/Public/2013/DataFiles/DXXAAC_H.htm).

Covariables

Based on the results of previous studies34,35, we incorporated various confounding elements that could influence the relationship between UHR and AAC. This study encompassed a broad array of covariates, such as sex, age, ethnicity, income-to-poverty ratio (PIR), marital status, educational attainment, and body mass index (BMI). Additionally, we considered smoking history, diabetes, hypertension, and biochemical markers Like serum calcium, serum phosphorus, serum creatinine, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D. People who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes were classified as having a smoking history, while people who denied smoking were recorded as ‘no’. Participants were defined as drinkers if they answered ‘yes’ to the question of drinking at least 12 times per year. Participants were classified as having a history of hypertension if they answered ‘yes’ when asked by a medical professional about hypertension status; otherwise, they were classified as ‘no’. Diabetes was identified through self-reported professional diagnosis and a fasting plasma glucose level of at least 126 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5%36,37.

Statistical analysis

UHR was log2-transformed to reduce skewness of the distribution, and participants were categorized into three groups based on UHR tertiles. For continuous variables that followed a normal distribution, the average and standard deviation (SD) were used for description. For skewed continuous data, the median and interquartile range were utilized. Categorical variables were presented through frequencies and percentages. To examine significant group differences in UHR tertiles, Kruskal-Wallis H, one-way ANOVA, and chi-square tests were employed. Weighted multivariate logistic regression or Linear regression analysis was employed to explore the association between UHR and AAC scores, the risks of AAC and SAAC. In the first multivariate model, we controlled sex, race and age. In multivariate model 2, a further adjustment was made for all other variables (see Table 2). Monotonic trends were assessed by introducing the median of the tertiles of UHR as a continuous variable into the model. A restricted cubic spline function was used to investigate the log-linear dose-response relationship between log2-UHR and AAC scores, as well as the risk of AAC and SAAC. The relationship between UHR, AAC scores, and the Likelihood of AAC and SAAC was further investigated through subgroup and interaction analyses to ascertain if these connections varied based on sex, age, PIR, BMI, smoking status, hypertension, and diabetes. Sensitivity analysis was conducted on 3,016 samples with complete AAC and UHR data after multiple imputation of missing values to validate the robustness of the results on the association between AAC and UHR. The evaluations were conducted using R (version 4.4.1) alongside Empowerstats (version 4.2) or Zstats v1.0 (www.zstats.net). A two-tailed p-value below 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Among the 2,731 participants aged 40 and above, the average age was 58.64 years with a standard deviation of 12.02, 51.59% were female, and 45.73% identified as non-Hispanic white. The mean AAC scores for the entire group was 1.66, with a standard deviation of 3.53. A total of 827 (30.28%) participants had AAC, defined as an AAC scores of 1 or higher, while 252 (9.23%) were classified with severe AAC, having an AAC scores of more than 6. Subsequent analysis divided into three parts according to the UHR scores, revealing significant differences (p < 0.05) in sex, PIR, education level, marital status, smoking history, diabetes, hypertension, serum creatinine, serum phosphorus, BMI, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, AAC scores, and the difference between AAC and SAAC. Individuals with elevated UHR scores tended to be male and living with a partner, and they were also more prone to smoking, diabetes, and hypertension than those with the lowest UHR scores. In addition, participants with higher UHR scores tended to have higher body mass index (BMI), serum creatinine and AAC scores as well as AAC prevalence (including SAAC) and lower PIR (Table 1 for details).

Association between UHR and AAC

As shown in Table 2, in the fully adjusted model, a 1 unit rise in log2-UHR corresponded to a 0.53 [β (95% CI): 0.53 (0.31, 0.75)]increase in the AAC scores. The risks of AAC and SAAC increased by 43% [OR (95% CI): 1.43 (1.22, 1.67)] and 60% [OR (95% CI): 1.60 (1.21, 2.12)], respectively. After dividing the UHR into three equal groups, the participants in the top tertile exhibited a markedly higher AAC scores compared to those in the bottom tertile [β(95% CI): 0.87 (0.51, 1.23)]. In addition, the risks of AAC and SAAC in the highest UHR tertile was 85% [OR (95% CI): 1.85 (1.37, 2.48)] and 108% [OR (95% CI): 2.08 (1.39, 3.11)] higher than in the lowest tertile, respectively. A restricted cubic spline was employed to illustrate the log-linear dose-response relationship between UHR and AAC scores, as well as the risk of AAC and SAAC. This analysis consistently revealed a positive and linear correlation between log2-UHR and both the AAC scores and the risks of AAC and SAAC (Fig. 2A-C).

The nonlinear associations between UHR and AAC. Sex, age, race, PIR, marital status, education level, BMI, smoked, diabetes, hypertension, serum calcium, serum phosphorus, serum creatinine and 25-hydroxyvitamin D were adjusted. PIR, the ratio of income to poverty; BMI, Body Mass Index; AAC, abdominal aortic calcification; SAAC, Severe abdominal aortic calcification.

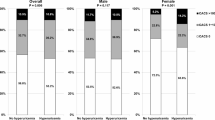

Subgroup analyses

To examine whether the observed associations differed based on factors such as age, sex, PIR, educational attainment, BMI, smoking status, diabetes, and hypertension, we conducted subgroup and interaction analyses. The findings indicated that the relationships in certain subgroups were not uniform. As shown in Fig. 3, when performing a subgroup analysis of the association between log2-UHR and AAC scores, we found that the association varied among subgroups of sex, BMI, age, and smoking history (interaction test p-value < 0.05). In the subgroups of female, no smoking history, > 60 years old, and (BMI ≦ 25 or BMI > 30), log2-UHR was significantly positively associated with AAC scores, while in other cases, this association was not significant. Figure 4 demonstrates that in a subgroup analysis examining the association between log2-UHR and the risk of AAC prevalence, every subgroup classification reveals a positive correlation between log2-UHR and the risk of AAC prevalence. This association also varies in subgroups of sex, smoking status and age (P < 0.05 for interaction). The positive association was significant in the female, never-smoker and over-60 age groups. As shown in Fig. 5, upon conducting a subgroup analysis to examine the association between log2-UHR and the risk of SAAC prevalence, every subgroup demonstrated a positive correlation between log2-UHR and the risk of AAC prevalence. The association also differed in the sex and smoking status subgroups (interaction P < 0.05). This positive association persisted notably within the female and non-smoker subgroups, while it was not significant in the male and smoking history subgroups. Subgroup/interaction analyses were conducted using unweighted data to maximise statistical power and preserve original variability, while the population representativeness estimates in Table 2 were obtained through Weighted regression analysis. It was established that the correlation coefficients in Model 2 of the association analyses of UHR and AAC scores, AAC, and SAAC in Table 2 differed from those of the total population in subgroup analyses (Figs. 3, 4 and 5). However, it was concluded that all were significantly positively correlated.This result further validates the robustness of the findings.

Subgroup analysis of the association between log2-UHR and AAC scores. Sex, age, race, PIR, marital status, education level, BMI, smoked, diabetes, hypertension, serum calcium, serum phosphorus, serum creatinine and 25-hydroxyvitamin D were adjusted. Unweighted data were used for subgroup/interaction analyses. PIR, the ratio of income to poverty; BMI, Body Mass Index; AAC, abdominal aortic calcification.

Subgroup analysis of the association between log2-UHR and AAC. Sex, age, race, PIR, marital status, education level, BMI, smoked, diabetes, hypertension, serum calcium, serum phosphorus, serum creatinine and 25-hydroxyvitamin D were adjusted. Unweighted data were used for subgroup/interaction analyses. PIR, the ratio of income to poverty; BMI, Body Mass Index; AAC, abdominal aortic calcification.

Subgroup analysis of the association between log2-UHR and SAAC. Sex, age, race, PIR, marital status, education level, BMI, smoked, diabetes, hypertension, serum calcium, serum phosphorus, serum creatinine and 25-hydroxyvitamin D were adjusted. Unweighted data were used for subgroup/interaction analyses. PIR, the ratio of income to poverty; BMI, Body Mass Index; SAAC, Severe abdominal aortic calcification.

The mediating role of diabetes

We performed a causal mediation analysis to investigate the relationship between diabetes, UHR, and AAC scores, as well as the possible mediating influence on AAC occurrence(Figs. 6). In the mediation model and path, log2-UHR intake was considered as the independent variable, diabetes as the mediating variable, and AAC scores and prevalence as the dependent variables. After taking into account the confounding variables, the results of the study proved that log2-UHR had a significant indirect effect on AAC scores and the risk of severe AAC, producing indirect effects of 0.031 (P = 0.022) and 0.003 (P = 0.002) respectively through diabetes. In addition, log2-UHR and AAC scoress and the prevalence of AAC and SAAC were also found to have significant direct effects (P < 0.05), suggesting that diabetes plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between UHR and AAC scores, as well as in the occurrence of SAAC. As illustrated in Figs. 6, diabetes accounted for about 7.5% of the connection between log2-UHR and AAC scores, and 14.0% of the link between log2-UHR and SAAC prevalence. The findings from the mediation analysis, such as direct impact, indirect influence, overall effect, and mediation proportion, are detailed in Table 3.

Diabetes Mellitus: Mediation analysis in the association between UHR and AAC scores and the prevalence of AAC and SAAC. In the mediation analysis, adjustments were made for sex, age, race, PIR, marital status, education level, BMI, smoked, diabetes, hypertension, serum calcium, serum phosphorus, serum creatinine and 25-hydroxyvitamin D. UHR, the ratio of uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; AAC, abdominal aortic calcification. SAAC, severe abdominal aortic calcification.

Sensitivity analysis

Following the multiple interpolation of missing values in 3,016 samples containing complete AAC and UHR data(Missing values include 2 for education, 1 for marital status, 240 for PIR, 22 for BMI, 19 for serum calcium, 3 for hypertension, 2 for diabetes, and 2 for smoking), the results of the association analysis between UHR and AAC scores, and between AAC, SAAC and disease risk, remained consistent with the current findings. This further validates the robustness of the results of this study (see Table 4).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional analysis involving 2,731 representative individuals, a positive relationship was noted between log2-UHR and AAC scores, as well as the occurrence of AAC and SAAC. This indicates that elevated log2-UHR levels are linked to higher AAC scores and a greater incidence of both AAC and SAAC.

This study is the first to confirm an independent association between UHR and AAC, providing a novel perspective on the regulation of cardiovascular disease risk. While previous studies have demonstrated that UHR is closely linked to cardiovascular disease30,38,39, they have not yet addressed the subclinical vascular lesion stage of abdominal aortic calcification.This finding fills a critical gap: UHR serves as an early reliable marker for subclinical atherosclerosis and a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events31,40. Additionally, this study identified diabetes as a significant mediator in the association between UHR and AAC. Previous studies have primarily examined the role of insulin resistance41, lipid metabolism disorders42,43, or hyperuricemia44 with vascular lesions. This study is the first to confirm a direct association between UHR and AAC, with diabetes partially mediating this association.

The association between UHR and AAC may result from a multi-pathway synergistic effect: first, insulin resistance plays a crucial role in atherosclerosis45, and UHR is associated with insulin resistance46,47,48, so insulin resistance may act as a pathway linking UHR to AAC.Previous studies have shown that better insulin signaling is associated with stronger antioxidant defense capabilities, which helps inhibit the formation of atherosclerotic plaques and promote plaque stability49. Additionally, hyperuricemia is associated with insulin resistance, and reducing uric acid levels can improve insulin sensitivity50,51. Existing studies also indicate that insulin resistance is closely associated with cardiovascular disease52,53. Furthermore, metabolic abnormalities and inflammation are associated with insulin resistance. Experimental studies show that metabolic dysfunction and inflammation are accompanied by reduced insulin sensitivity, manifested as decreased Akt/GSK3β phosphorylation levels54. An effective siRNA formulation can alleviate related inflammatory responses by reducing lipoprotein concentrations55.Existing studies also indicate that a prospective study found targeted anti-inflammatory treatment in patients with acute myocardial infarction reduced the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events56; another study also noted that an inflammatory diet is associated with cardiovascular disease and proposed that the dietary inflammation index could serve as an important indicator of cardiovascular disease risk57, and that an inflammatory marker model could be used to predict mortality after cardiac valve surgery58.Finally, lipid metabolism abnormalities associated with UHR may be a potential mechanism underlying the development of aortic atherosclerosis. It is known that high-density lipoprotein promotes cholesterol efflux and reverse cholesterol transport59. However, dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein may accelerate the atherosclerotic process due to reduced cholesterol efflux capacity15. In existing cohort studies, elevated HDL-C/Apo AI ratios have been found to be closely associated with cardiovascular disease60. Another prospective cohort study of patients with angina pectoris showed that triglyceride levels are associated with cardiovascular risk in women61. A case-control study by Wadhwa et al. found that PASI was significantly positively correlated with lipoprotein-a and atherosclerosis indices62.

In this study, we found that diabetes partially mediated the association between UHR and AAC scores and the occurrence of SAAC, particularly explaining 14.0% of the association between UHR and the frequency of SAAC occurrence. Previous studies have shown that hyperuricemia induces oxidative stress in pancreatic β-cells, leading to β-cell apoptosis and reduced insulin secretion21,63, while controlling uric acid levels can alleviate β-cell apoptosis, a phenomenon commonly observed in type 2 diabetes64. Animal studies have shown that uric acid triggers excessive nitric oxide production in pancreatic β-cells via the NF-κB signaling pathway65. On the other hand, lipid metabolism disorders can also lead to impaired glucose tolerance, and hyperglycemia, in turn, can cause increased transcription of apolipoprotein A-II66, further indicating that reduced HDL-C is associated with insulin resistance67,68, which may influence diabetes. UHR, as a comprehensive indicator reflecting uric acid and lipid metabolism abnormalities, can accurately reflect impaired pancreatic β-cell function and glucose metabolism abnormalities, and is closely associated with diabetes. Additionally, the impact of diabetes on arterial calcification has been confirmed69,70. Therefore, UHR indirectly impairs insulin function by elevating uric acid and abnormal lipid levels, thereby promoting the progression of arterial calcification—diabetes is both a downstream manifestation of UHR-related metabolic abnormalities and a direct driver of vascular calcification, ultimately exhibiting a significant mediating effect on the UHR-AAC association.

The strength of our study is that NHANES is a nationally representative sample survey, which improves the reliability and representativeness of the study. AAC uses a standardised Kauppila scoring system based on DXA for assessment, ensuring the reliability of quantitative measurements; UHR is measured using strictly standardised laboratory protocols, providing stable biomarker data; hypertension status is determined through self-reporting, enabling large-scale analysis. Of course, there are still some limitations to this study. First, because this is a cross-sectional study, it is impossible to determine the causal relationship between UHR and AAC. Second, the Kauppila score may underestimate the extent of early calcification, UHR measurements are limited by single-time-point sampling and the influence of lipid-lowering and uric acid-lowering medications, while hypertension status based on self-reporting may introduce potential underdiagnosis bias. Third, hypertension and diabetes were defined based on self-reported diagnostic results, which may lead to underdiagnosis or misclassification. In reality, some individuals classified as “non-hypertensive” or “non-diabetic” might have undiagnosed hypertension or diabetes, resulting in a blurring of the true distinction between the affected and non-affected groups. This non-differential misclassification could weaken the observed associations: for hypertension, residual confounding might persist due to incomplete control of its true prevalence, potentially underestimating its role in the relationship between UHR and AAC. For diabetes, as a key mediator, such misclassification may dilute the actual mediating effect, as part of the indirect pathway from UHR to AAC via diabetes could be masked. Overall, this limitation might lead to an underestimation of the true associations or mediating effects, though it reflects a common challenge in observational studies relying on self-reported health data. In addition, due to the limitations of the database, to keep a sufficiently large sample, we couldn’t incorporate all the data related to factors influencing heart health, inflammatory responses, and metabolic rates. The validity of these conclusions is dependent on further validation with larger sample sizes and prospective cohort studies, which are required to establish causal relationships.

Conclusion

In summary, the study results indicate that UHR is positively correlated with AAC scores and with the risk of both AAC and SAAC. Additionally, diabetes plays a partial mediating role in the association between UHR and AAC scores as well as the incidence of SAAC. As a low-cost routine diagnostic marker, UHR may help identify high-risk populations for AAC, particularly those with diabetes.The study results suggest that UHR may have potential clinical applications in assessing AAC scores and determining the risk of AAC and SAAC, but further cohort studies are needed to validate the causal relationship.

Data availability

The survey data can be accessed publicly online for users and researchers globally (www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/).

Abbreviations

- UHR:

-

Uric Acid to High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Ratio

- AAC:

-

Abdominal aortic calcification

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PIR:

-

Income-to-Poverty Ratio

References

Wang, W. et al. Association between periodontitis and carotid artery calcification: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 3278351 (2021).

Jiang, W. et al. The cell origin and role of osteoclastogenesis and osteoblastogenesis in vascular calcification. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 639740 (2021).

Van den Bergh, G. et al. Endothelial contribution to warfarin-induced arterial media calcification in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11615 (2021).

Sheng, C., Cai, Z. & Yang, P. Association of the abdominal aortic calcification with all-cause and cardiovascular disease-specific mortality: prospective cohort study. PloS One. 20, e0314776 (2025).

Qin, Z. et al. Greater dietary inflammatory potential is associated with higher likelihood of abdominal aortic calcification. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 720834 (2021).

Imaoka, K. et al. Effect of abdominal aortic calcification on the prognosis and recurrence of colorectal cancer stages II–III: A retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 38, 21 (2023).

He, S. et al. Association between cardiovascular health and abdominal aortic calcification: analyses of NHANES 2013–2014. Int. J. Cardiol. 403, 131878 (2024).

Demer, L. L. & Tintut, Y. Interactive and multifactorial mechanisms of calcific vascular and valvular disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metabolism. 30, 646–657 (2019).

Zhang-wei, C., Qian, J., Ma, J., Ge, L. & Liu, X. Shu X-h, ge J: prevalence and severity of coronary artery disease in diabetic patients with aortic valve calcifi cation. Acta Cardiol. 66, 15–20 (2011).

Wang, F. & Zheng, J. Association between serum alpha-Klotho and severe abdominal aortic calcification among civilians in the united States. Nutr. Metabolism Cardiovasc. Dis. 32, 1485–1492 (2022).

Dalla Via, J. et al. Machine-Learning assessed abdominal aortic calcification is associated with Long‐Term fall and fracture risk in Community‐Dwelling older Australian women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 38, 1867–1876 (2023).

Alhamdow, A. et al. Cardiovascular disease-related serum proteins in workers occupationally exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Toxicol. Sci. 171, 235–246 (2019).

Kim, J. O. et al. Machine learning-based cardiovascular disease prediction model: a cohort study on the Korean National health insurance service health screening database. Diagnostics 11, 943 (2021).

Sphitzen, S. et al. Missing in action: the genetic mysteries of extremely low HDL cholesterol. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12, 1553259 (2025).

Hoekstra, M. et al. LXR agonist T0901317′ s hepatic impact overrules its atheroprotective action in macrophages, driving early atherogenesis in Chow-Diet-Fed male Apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Biomolecules 14, 429 (2024).

Zhao, D. et al. Different relationship between ANGPTL3 and HDL components in female non-diabetic subjects and type-2 diabetic patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 15, 132 (2016).

Kashyap, S. R. et al. Glycation reduces the stability of ApoAI and increases HDL dysfunction in diet-controlled type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 103, 388–396 (2018).

Cade, W. T. Diabetes-related microvascular and macrovascular diseases in the physical therapy setting. Phys. Ther. 88, 1322–1335 (2008).

Baba, I. et al. EVs-miR-17-5p attenuates the osteogenic differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells potentially via Inhibition of TGF-β signaling under high glucose conditions. Sci. Rep. 14, 16323 (2024).

Han, M. et al. Serum uric acid is associated with coronary artery calcification in early chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 22, 247 (2021).

Lai, S-W., Hwang, B-F., Kuo, Y-H., Liu, C-S. & Liao, K-F. Allopurinol use and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A Meta-Analysis of cohort studies. Dose-Response 20, 15593258221123677 (2022).

Brittain, E. L. et al. Fatty acid metabolic defects and right ventricular lipotoxicity in human pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 133, 1936–1944 (2016).

González Hernández, M. A., Canfora, E. E., Jocken, J. W. & Blaak, E. E. The short-chain fatty acid acetate in body weight control and insulin sensitivity. Nutrients 11, 1943 (2019).

Guo, Y. et al. Triglyceride glucose index influences platelet reactivity in acute ischemic stroke patients. BMC Neurol. 21, 409 (2021).

Jiang, F. et al. Correlation between uric acid/high density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and postoperative AKI in patients with CABG. International J. Gen. Medicine 2024, 6065–6074 (2024).

Wu, M. B. et al. Association between uric acid to High-Density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and kidney function in patients with primary aldosteronism: A Cross‐Sectional study. J. Clin. Hypertens. 27, e14960 (2025).

Li, W. et al. The serum uric acid/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio: a novel predictor for the presence of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1481872 (2024).

Wu, M. et al. Computed tomography (CT) calcium scoring in primary prevention of acute coronary syndrome and future cardiac events in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Cureus 15, 10(2023).

Han, C. et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled ECG algorithm for the prediction of coronary artery calcification. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 849223 (2022).

Wang, X., Shi, Y., Zi, Y., Long, J. & Shi, R. Association of serum uric acid-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with cardiovascular disease risk in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: a cross-sectional NHANES analysis. Front. Nutr. 12, 1561594 (2025).

Cui, Y. & Zhang, W. Long-term cardiovascular risk and mortality associated with uric acid to HDL-C ratio: a 20-year cohort study in adults over 40. Sci. Rep. 15, 14242 (2025).

Han, X. et al. Association between serum uric acid/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and hypertension among reproductive-aged women. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 42, 123 (2023).

Xie, Y. et al. Association of serum uric acid-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in American adults: a population-based analysis. Front. Med. 10, 1164096 (2023).

Zhou, Y., Zhi, F., Gao, B. & Liao, S. Triglyceride glucose index was linearly associated with abdominal aortic calcification based on NHANES 2013–2014. BMC Endocr. Disorders. 22, 318 (2022).

Qin, Z. et al. Higher visceral adiposity index is associated with increased likelihood of abdominal aortic calcification. Clinics 77, 100114 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Trends in prevalence of diabetes and control of risk factors in diabetes among US adults, 1999–2018. Jama 326, 704–716 (2021).

Liu, B. et al. Association between plasma concentrations of Elaidic acid, a major trans fatty acid, and depression in a nationally representative sample of US adults. J. Affect. Disord. 249, 301–306 (2019).

Liu, G. et al. Correlation between serum uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and atrial fibrillation in patients with NAFLD. PLoS One. 19, e0305952 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. The interaction between uric acid and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol on the prognosis of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1226108 (2023).

Lai, X. & Chen, T. Association of serum uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes: a prospective cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1476336 (2024).

Bornfeldt, K. E. 2013 Russell Ross memorial lecture in vascular biology: cellular and molecular mechanisms of diabetes Mellitus–Accelerated atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34, 705–714 (2014).

Kresanov, P. et al. The associations of oxidized lipoprotein lipids with lipoprotein subclass particle concentrations and their lipid compositions. The cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 162, 225–232 (2021).

Azarpazhooh, M. R. et al. Triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio: a clue to metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and severe atherosclerosis. Lipids 56, 405–412 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Establishment and evaluation of a nomogram prediction model for the risk of vascular calcification in stage 5 chronic kidney disease patients. Sci. Rep. 14, 1025 (2024).

Reddy, K. J., Singh, M., Bangit, J. R. & Batsell, R. R. The role of insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: an updated review. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 633–647 (2010).

Lan, W. et al. Association between serum uric acid to High-Density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and pneumonia after endovascular treatment of vertebrobasilar artery occlusion. Journal Inflamm. Research 2025, 2899–2908 (2025).

Liu, A. et al. Association between the ratio of serum uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and liver fat content: evidence from a Chinese health examination dataset. Sci. Rep. 14, 31397 (2024).

Zhou, X. & Xu, J. Association between serum uric acid-to‐high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and insulin resistance in an American population: A population‐based analysis. J. Diabetes Invest. 15, 762–771 (2024).

Peteliuk, V., Rybchuk, L., Bayliak, M., Storey, K. B. & Lushchak, O. Natural sweetener stevia rebaudiana: functionalities, health benefits and potential risks. EXCLI J. 20, 1412 (2021).

Hossain, I. et al. Elevated levels of serum uric acid and insulin resistance are associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among prediabetic subjects. Trop. Gastroenterol. 37, 101–111 (2016).

Zong, Q., Ma, G. & Wang, T. Uric acid Lowering improves insulin sensitivity and lowers blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized parallel-controlled clinical trials. Afr. Health Sci. 21, 82–95 (2021).

Lu, M-C. et al. The association between insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease risk: a community-based cross-sectional study among Taiwanese people aged over 50 years. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17, 7195 (2020).

Tahara, N., Imaizumi, T., Takeuchi, M. & Yamagishi, S. -i: insulin resistance is an independent correlate of high serum levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and low testosterone in non-diabetic men. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 3, 262–265 (2010).

Deng, W. et al. Loss of regulator of G protein signaling 5 exacerbates obesity, hepatic steatosis, inflammation and insulin resistance. PLoS One. 7, e30256 (2012).

Simantiris, S. et al. Lipoprotein (a) and inflammation-pathophysiological links and clinical implications for cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Lipidol. 17, 55–63 (2023).

Wei, X., Zhang, Z., Wei, J. & Luo, C. Association of systemic immune inflammation index and system inflammation response index with clinical risk of acute myocardial infarction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1248655 (2023).

Li, T. et al. Prognostic significance of inflammation in patients with coronary artery disease at low residual inflammatory risk. Iscience 26, 11. (2023).

Cho, J. S. et al. Risk stratification model integrating nutritional and inflammatory factors for predicting 1-year mortality after valvular heart surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 110, 287–295 (2024).

Yin, Q., Chang, H., Shen, Q. & Xing, D. Photobiomodulation therapy promotes the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1‐dependent cholesterol efflux in macrophage to ameliorate atherosclerosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 25, 5238–5249 (2021).

Sung, K-C., Ryu, S., Wild, S. H. & Byrne, C. D. An increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol/apolipoprotein AI ratio is associated with increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. Heart 101, 553–558 (2015).

Prasad, M. et al. Triglyceride and triglyceride/hdl (high density lipoprotein) ratio predict major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in women with non-obstructive coronary artery disease. J. Am. Heart Association. 8, e009442 (2019).

Wadhwa, D. et al. Malondialdehyde, lipoprotein-a, lipoprotein ratios, comprehensive lipid tetrad index and atherogenic index as surrogate markers for cardiovascular disease in patients with psoriasis: a case–control study. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 311, 287–297 (2019).

Anothaisintawee, T. et al. Direct and indirect effects of serum uric acid on blood sugar levels in patients with prediabetes: a mediation analysis. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 6830671 (2017).

Keles, U., Ow, J. R., Kuentzel, K. B., Zhao, L. N. & Kaldis, P. Liver-derived metabolites as signaling molecules in fatty liver disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 80, 4 (2023).

Jia, L. et al. Hyperuricemia causes pancreatic β-cell death and dysfunction through NF-κB signaling pathway. PloS One. 8, e78284 (2013).

Florea, G. et al. Apolipoprotein A-II, a player in multiple processes and diseases. Biomedicines 10, 1578 (2022).

Kim, J. Y. & Kim, N. H. New therapeutic approaches to the treatment of dyslipidemia 1: ApoC-III and ANGPTL3. J. Lipid Atherosclerosis. 12, 23 (2022).

Ibrahim, S. L., Al-Dawah, N. K. J. & Al-Barqaawi, M. A. Comparative analysis of antioxidant status in diabetic patients with and without insulin resistance. J. Med. Life. 16, 1321 (2023).

Chen, W. et al. Diabetes mellitus modifies the associations of serum magnesium concentration with arterial calcification and stiffness in incident Hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. Rep. 4, 806–813 (2019).

Alappan, H. R., Vasanth, P., Manzoor, S. & O’Neill, W. C. Vascular calcification slows but does not regress after kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. Rep. 5, 2212–2217 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants in this study.

Funding

This study did not obtain any specific financial support from any funding organizations in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL led the research design and framework development, was responsible for data collection and analysis, drafted the results and discussion sections of the manuscript, and conducted the final revision of the manuscript. LB assisted with the research design, participated in data collection and organization, was responsible for the literature review and writing the relevant background, provided analysis and discussion comments on the results, and contributed to manuscript revision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The parts of this research that included human participants, materials, or data were carried out following the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the NCHS Ethics Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to take part in this research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Bai, L. Diabetes mediates the association between uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio and abdominal aortic calcification: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 35307 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19388-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19388-7