Abstract

Retinal artery occlusion (RAO) results in severe visual impairment and may indicate cerebral infarction and extracranial carotid artery stenosis at onset. RAO-related genetic factors remain understudied. We investigated the association between RAO and RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys (c.14429G > A), a genetic variant recently identified as a susceptibility factor for moyamoya disease, a risk factor for stroke. Patients diagnosed with non-arteritic (NA)-RAO at our department between May 2020 and April 2021 underwent magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography angiography. Sanger sequencing revealed that RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys was significantly more frequent in the NA-RAO group (10.7%) than in the control group (1.1%). We conducted a logistic regression analysis adjusted for age and sex to compare the NA-RAO (n = 28) and healthy control groups (n = 1,202), which indicated a significant association between RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys and NA-RAO (P = 0.001, odds ratio 13.52, 95% confidence interval [3.09–59.18]). Among patients with NA-RAO, 50%, 76%, and 40% had simultaneous strokes, hypertension, and diabetes, respectively. There were no significant differences between groups in medical history, biomarkers, imaging characteristics, or ophthalmic artery diameter. RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys was significantly associated with NA-RAO, indicating genetic susceptibility to systemic vascular diseases. Further studies can elucidate broader implications of RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys in vascular disease pathogenesis, particularly in East Asian populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Retinal artery occlusion (RAO) is a disease that causes severe visual dysfunction due to ischaemia and necrosis of the retina caused by the occlusion of the retinal artery. The incidence of RAO in Japan is relatively high (5.84 per 100,000 person-years)1 compared with that in other countries, such as the United States (1.62–1.82 per 100,000 person-years) and Croatia (0.70 per 100,000 person-years)2,3. RAO has long been thought to be associated with extracranial carotid artery stenosis; recent studies have suggested that RAO may serve as a clinical marker for complications of cerebral infarction and extracranial artery stenosis (ECAS) at the onset of RAO4. Furthermore, studies on prognosis after RAO have shown an increased risk of death, stroke, and myocardial infarction in both short and long terms5. To our knowledge, no previous studies have analysed the genetic factors associated with non-arteritic RAO (NA-RAO). The RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys (c.14429G > A) variant, a susceptibility factor for moyamoya disease (MMD), is primarily characterised by idiopathic intracranial artery stenosis (ICAS) and has been reported as an important genetic factor for stroke in East Asian populations6,7. Additionally, RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys has been shown to be associated with systemic artery stenosis, including ECAS and pulmonary artery stenosis8,9, as well as ICAS10. Furthermore, recent reports have suggested an association between MMD and NA-RAO11. Therefore, we hypothesised that RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys is associated with NA-RAO. In this study, we aimed to analyse the association between NA-RAO and RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

This retrospective study included consecutive patients over a one-year period (May 2020 to April 2021) who presented with acute, painless visual impairment and were suspected of having retinal artery occlusion (RAO) at the Department of Ophthalmology, Kyorin University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants (Fig. 1).

Flowchart of patient enrollment and evaluation process. Figure 1 Patients with suspected non-arteritic retinal artery occlusion (NA-RAO) presenting with acute visual impairment were referred from the ophthalmology department to the stroke center over a one-year period. NA-RAO was diagnosed based on fundus examination and fluorescein angiography. All patients underwent same-day stroke center consultation, where they received MRI and carotid ultrasonography. Blood tests and RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys genetic testing were performed in all cases. Two patients were excluded owing to incomplete evaluations. The final NA-RAO group included 28 patients. The control group comprised 1,202 healthy individuals from the University of Tokyo Medical Genome Center, for whom only age, sex, and RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys status were available. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Diagnosis of NA-RAO

All patients underwent a comprehensive ophthalmologic evaluation, including funduscopy and fluorescein angiography, performed by retinal specialists. The diagnosis of non-arteritic retinal artery occlusion (NA-RAO) was based on characteristic retinal findings, including retinal whitening in the distribution of the affected artery and/or a cherry-red spot in the macula (Fig. 2), in the absence of systemic signs or symptoms suggestive of arteritic causes (e.g., giant cell arteritis). Patients with suspected arteritic RAO or vasculitis were excluded from the study (Fig. 1).

Representative fundus photographs comparing normal and RAO eyes. (a) Fundus image of a healthy eye demonstrating normal retinal structures. (b, c) Fundus image of a patient who presented to our ophthalmology department with painless vision loss and was subsequently diagnosed with non-arteritic retinal artery occlusion (NA-RAO) based on (b) fundus findings and (c) fluorescence ophthalmography (44 s). Note the pallor of the retina in the macular region and attenuation of the retinal vessels, characteristic of NA-RAO. NA-RAO, non-arteritic retinal artery occlusion

Stroke evaluation and genetic testing

All patients received an immediate same-day referral to the stroke center for further evaluation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed by a skilled stroke physician (K.N., T.J., H.M.) on the day of RAO diagnosis to rule out/identify intracranial lesions. If a stroke was detected, the patient was admitted for further testing, including blood sampling and carotid ultrasonography. For patients without stroke, neck ultrasonography was performed within two weeks on an outpatient basis. Blood samples were collected at the time of the initial visit for biomarker analysis and cardiovascular risk factor evaluation. Genetic testing for the RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys variant was also performed (Fig. 1). ICAS was primarily diagnosed based on magnetic resonance angiography and three-dimensional computed tomography angiography findings and the degree of stenosis. The degree of ICAS was determined according to the criteria of the Warfarin Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) trial12. The degree of ECAS was determined according to the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST); stenosis of 50% or more was considered "stenotic”13. Maximum intima-media thickness (max-IMT) was defined as the localised thickest area of the intima-media (IM) found when evaluating the bilateral internal carotid arteries.

Genetic analysis of RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys

Genomic DNA was obtained from peripheral blood leukocytes. The coding region bearing the p.Arg4810Lys variant of RNF213 was amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). We used the primers (forward: 5′-CTGCATCACAGGAAATGACACTG-3’; reverse: 5′-TGACGAGAAGAGGCTTTCAGACGA-3’, product size: 782 bp) for amplification and sequencing, as reported previously14. A KAPA Taq Extra PCR Kit (Cat No. KK3009; Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA) was utilised. PCR-purified products were treated with Illustra ExoProStar, Enzymatic PCR, Sequence Reaction Clean-up Kit (US78225; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL), and BigDye XTerminator Purification Kit (4,376,484; Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA) before sequencing. Mutational analysis of exon 60, which includes the p.Arg4810Lys variant of RNF213 (National Center for Biotechnology Information Reference Sequences NM_001256071 and NP_00124300), was performed using direct Sanger sequencing with the Applied Biosystems 3730 DNA Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

As control data from the general population with a frequency of RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys, we used the genetic analysis data of healthy individuals (without a history of stroke) from the database of exome-sequenced samples at the Medical Genome Research Support Center, University of Tokyo Hospital.

Statistical analyses

We compared the background factors between two groups—those with and without the presence of RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys—using the two-tailed Fisher’s exact test; the Mann–Whitney U test was used for age comparisons. Logistic regression analysis was employed to analyse the association between RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys and NA-RAO while adjusting for age and sex. SPSS version 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for statistical analysis. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committees for Human Genome Gene Analysis Research of Kyorin University of Medicine (approval number: 771), The University of Tokyo (approval number: G10026), and Koyama Memorial Hospital (approval number: 0200316–1). All procedures followed were in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Results

Characteristics of NA-RAO

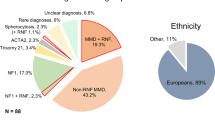

The study included 30 patients with RAO, two of whom were excluded (one who was insufficiently examined and one with vasculitis), resulting in a final count of 28 patients. Patients with NA-RAO had a mean age of 66 ± 13 years (range, 40–84), and 67% (2/28) were female. A history of hypertension was found in 76% (20/28) of the patients, while 40% (10/28) had diabetes, 12% (3/28) had a history of heart disease, and 16% (5/28) had a history of stroke. The subtypes of these previous strokes were as follows: cardioembolic infarction (n = 2), atherothrombotic infarction (n = 2), and lacunar infarction (n = 1). Among the 12 patients with NA-RAO who experienced concomitant stroke, the subtypes of cerebral infarction were further classified as follows: atherothrombotic infarction (n = 7), cardioembolic infarction (n = 2), and lacunar infarction (n = 1). In addition, one patient presented with intracerebral haemorrhage (Supplementary Table S1). Patients with RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys had lower HbA1c levels than those without. Among the 28 patients with NA-RAO, 14 were diagnosed with central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) and 14 with branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO). The mean initial logMAR visual acuity was 2.21 ± 0.86 in the CRAO group and 0.44 ± 0.55 in the BRAO group. There were no significant differences in medical history, biomarkers, imaging characteristics, or ophthalmic artery diameter (Table 1, Supplementary Table S2).

Consideration of complicated intracranial and extracranial artery stenoses

Of the 28 patients with NA-RAO, 18% (5/28) had ICAS exclusively, 11% (3/28) had ECAS exclusively on the same side as the NA-RAO, and 18% (5/28) had both ICAS and ECAS. Fifteen patients had no ICAS or ECAS. The max-IMT of the cervical echo was 2.7 ± 1.6 mm on the affected side and 2.5 ± 1.4 mm on the unaffected side. No significant differences were found in the presence or absence of RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys between patients with ICAS and ECAS or between the affected and unaffected sides (Table 1). Notably, none of the patients in the NA-RAO group fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for MMD. Specifically, no individuals exhibited steno-occlusive lesions at the terminal portion of the internal carotid artery (ICA) accompanied by the abnormal vascular networks (so-called “moyamoya vessels”) typically observed in MMD.

Association study of NA-RAO and RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys

The case group (n = 28) comprised patients with RAO, of whom 25 were RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys wild-type (GG group; n = 1,189), and three were RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys variant carriers (GA group; n = 13). The control group (n = 1,202) had a mean age of 49 ± 17 years (range 19–90) and 52% (628/1,202) were female. No homozygous cases (AA group) were found in either group (Table 1). The frequency of RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys was 10.7% (3/28) in the case group and 1.1% (13/1,202) in the control group. Interestingly, all three patients carrying the RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys variant were classified in the BRAO subgroup. In the logistic regression analysis adjusted for age and sex, RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys was significantly associated with NA-RAO (P = 0.001, odds ratio 13.52, 95% confidence interval [CI, 3.09–59.18]) (Table 2). We conducted a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis by removing one carrier of the RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys variant from the NA-RAO group at a time. The odds ratios remained consistently high (range: 7.30–9.16), with all 95% confidence intervals excluding unity, indicating that the association was not driven by a single individual. Fisher’s exact test also demonstrated a statistically significant association between RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys and NA-RAO (two-sided P = 0.0049), with a phi coefficient of 0.103 (Yates’ correction applied), suggesting a moderate degree of association. The effect size, as measured by Cohen’s h, was 0.608, consistent with a medium-to-large effect (small = 0.2, medium = 0.5, large = 0.8). The corresponding odds ratio was 10.98 (95% CI: 2.94–40.94).

Discussion

This study found that RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys was a genetic factor associated with NA-RAO, with a prevalence of 10.7% among patients with NA-RAO. To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify a genetic factor of NA-RAO. The RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys variant was first identified in MMD, and we recently reported that this variant is also prevalent among patients with stroke in the Japanese population15. RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys is associated with MMD and is prevalent in 80–90% of the Japanese population16. This variant has also been found in approximately 20% of patients with localised intracranial stenoses10,17 and 5% of patients with non-cardiogenic strokes in the Japanese population18. RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys has also been associated with systemic vascular diseases, including coronary19, pulmonary9, and renal artery stenoses8. One study suggested that RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys is associated with arteries throughout the body20.

Several studies have been conducted on the association between MMD and NA-RAO21. A Korean study of 49 patients with MMD reported that 6.1% (3/49) of the patients were diagnosed with retinal vascular occlusion, indicating a potentially strong association between MMD and retinal vascular occlusion. Furthermore, a large-scale nationwide population-based cohort study in Korea suggested that patients with MMD have an elevated risk of retinal vascular occlusion, indicating that MMD serves as a risk factor for this condition11. The study also reported that nine patients with unilateral MMD developed retinal vascular occlusion on the same side22. However, MMD primarily affects the carotid artery at the ophthalmic artery bifurcation, and reports of retinal vascular abnormalities in patients with MMD are rare23. Recent quantitative optical coherence tomography angiography studies have found a trend toward decreased microvascularity in the central fossa and decreased vascular density in patients with MMD compared with healthy participants. Despite these previous reports, the role of these microvascular changes in indicating cerebrovascular abnormalities in MMD remains unclear21. In the present study, we examined RAO patients with and without RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys and observed no differences in the ocular arterial vascular diameter or retinal vascular abnormalities. To our knowledge, previous studies have not investigated the role of genetic factors, including RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys, in the association between MMD and NA-RAO.

Furthermore, the RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys variant has been found to be associated with cerebral artery stenosis in the anterior circulation24. Considering its developmental anatomy, the retina is primarily supplied by the first branch of the internal carotid artery, also known as the ocular artery. Embryological differences have been suggested, with vessels of the anterior circulatory system originating from the neural crest and those of the posterior circulatory system originating from the mesoderm during embryonic development25. Furthermore, the central retinal artery is thought to originate from the forebrain and mesencephalon, which originate in the neural crest26.

The strengths of this study are that magnetic resonance imaging and genetic testing were performed in all patients at the time of onset, and the relationship with RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys was revealed, possibly for the first time.

Nevertheless, this study also had some limitations. First, the RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys variant is prevalent in East Asian populations but has a low incidence in Caucasians (maximum allele frequency: 0.0006) and other ethnic populations27. Therefore, our findings may not apply to populations outside East Asian countries. Second, although the presence of ICAS and ECAS may influence the arterial haemodynamics, we did not directly evaluate the flow pattern of the ophthalmic artery, which can be affected by intracranial or extracranial arterial stenosis. Techniques such as laser speckle flow graphy (LSFG) may be useful in future studies to directly assess ocular perfusion in relation to vascular lesions. Nevertheless, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of ICAS, ECAS, or combined ICAS + ECAS between RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys carriers and non-carriers, nor were there differences in maximum IMT. Third, while RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys was significantly associated with NA-RAO, our analysis was limited to intra-cohort comparisons within the NA-RAO group. This was owing to the restricted clinical information available for the control group, which only included age, sex, and RNF213 genotype. As a result, we were unable to perform phenotype comparisons or adjust for potential confounders such as comorbidities or vascular imaging findings between variant carriers in the NA-RAO and control groups. Future studies that include more comprehensive clinical and imaging data from both case and control variant carriers are essential to further elucidate the phenotype-specific implications of RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys. Nevertheless, the robustness of the observed association was supported by multiple lines of evidence. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the elevated odds ratios were not attributable to a single influential data point. The results remained statistically significant and directionally consistent across all iterations. Furthermore, the Fisher’s exact test confirmed the association (P = 0.0049), and the effect size (Cohen’s h = 0.608) suggested a medium-to-large association despite the limited number of variant carriers in the NA-RAO group. Although the sample size was small, the combination of traditional sensitivity provides a reasonably strong case for the validity of the association between RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys and NA-RAO. Therefore, owing to the low prevalence of RAO and the small sample size of our study, future studies investigating similar cases collected at other facilities over several years are necessary to validate and further elucidate the associations and mechanisms of RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys and NA-RAO.

Conclusion

We identified RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys as a genetic factor associated with NA-RAO. However, owing to the low prevalence of RAO and the ethnic specificity of RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys, further studies with larger samples across multiple facilities are warranted.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Kido, A. et al. Nationwide incidence of central retinal artery occlusion in Japan: an exploratory descriptive study using the National Database of Health Insurance Claims (2011–2015). BMJ Open 10, e041104 (2020).

Leavitt, J. A., Larson, T. A., Hodge, D. O. & Gullerud, R. E. The incidence of central retinal artery occlusion in Olmsted County. Minnesota. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 152, 820-823.e822 (2011).

Ivanisevic, M. & Karelovic, D. The incidence of central retinal artery occlusion in the district of Split. Croatia. Ophthalmologica. 215, 245–246 (2001).

Chodnicki, K. D. et al. Stroke risk before and after central retinal artery occlusion: a population-based analysis. Ophthalmology 129, 203–208 (2022).

Wai, K. M. et al. Risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and death after retinal artery occlusion. JAMA Ophthalmol. 141, 1110–1116 (2023).

Liu, W. et al. Identification of RNF213 as a susceptibility gene for moyamoya disease and its possible role in vascular development. PLoS ONE 6, e22542 (2011).

Kamada, F. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies RNF213 as the first Moyamoya disease gene. J. Hum. Genet. 56, 34–40 (2011).

Hara, S. et al. De novo renal artery stenosis developed in initially normal renal arteries during the long-term follow-up of patients with moyamoya disease. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 29, 104786 (2020).

Gamou, S. et al. Genetics in pulmonary arterial hypertension in a large homogeneous Japanese population. Clin. Genet. 94, 70–80 (2018).

Miyawaki, S. et al. Genetic variant RNF213 c.14576G>A in various phenotypes of intracranial major artery stenosis/occlusion. Stroke. 44, 2894–2897 (2013).

Kim, M. S. et al. Moyamoya disease increased the risk of retinal vascular occlusion: a nationwide cohort study in Korea. Ophthalmol. Retina. 9, 386–391 (2025).

Chimowitz, M. I. et al. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 1305–1316 (2005).

European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet 351, 1379–1387 (1998).

Ishigami, D. et al. RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys heterozygosity in moyamoya disease indicates early onset and bilateral cerebrovascular events. Transl. Stroke Res. 13, 410–419 (2022).

Shimada, D. et al. S. RNF213 p.Arg4810Lys (c.14429G>A) is associated with extracranial arterial stenosis. Brain Commun. 7, fcaf049 (2025).

Takamatsu, Y. et al. Differences in the genotype frequency of the RNF213 variant in patients with familial moyamoya disease in Kyushu Japan. Neurol. Med. Chir. (Tokyo) 57, 607–611 (2017).

Miyawaki, S. et al. Identification of a genetic variant common to moyamoya disease and intracranial major artery stenosis/occlusion. Stroke 43, 3371–3374 (2012).

Okazaki, S. et al. Moyamoya disease susceptibility variant RNF213 p.R4810K increases the risk of ischemic stroke attributable to large-artery atherosclerosis. Circulation. 139, 295–298 (2019).

Koyama, S. et al. Population-specific and trans-ancestry genome-wide analyses identify distinct and shared genetic risk loci for coronary artery disease. Nat. Genet. 52, 1169–1177 (2020).

Yamaguchi, E. et al. Association of the RNF213p.R4810K variant with the outer diameter of cervical arteries in patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke Vasc. Interv. Neurol. 2, 298 (2022).

Khan, H. M. et al. Quantitative optical coherence tomography angiography in patients with moyamoya vasculopathy: a pilot study. Neuroophthalmology. 45, 386–390 (2021).

Seong, H. J. et al. Clinical significance of retinal vascular occlusion in moyamoya disease: case series and systematic review. Retina 41, 1791–1798 (2021).

Ushimura, S., Mochizuki, K., Ohashi, M., Ito, S. & Hosokawa, H. Sudden blindness in the fourth month of pregnancy led to diagnosis of moyamoya disease. Ophthalmologica 207, 169–173 (1993).

Zhou, H. et al. Detailed phenotype of RNF213 p.R4810K variant identified by the Chinese patients with acute ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 8, 503–510 (2023).

Komiyama, M. RNF213 genetic variant and the arterial circle of Willis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 27, 2892–2893 (2018).

Suri, K. et al. Outcomes and readmission in patients with retinal artery occlusion (from the Nationwide Readmission Database). Am. J. Cardiol. 183, 105–108 (2022).

Grami, N. et al. Global assessment of Mendelian stroke genetic prevalence in 101 635 individuals from 7 ethnic groups. Stroke 51, 1290–1293 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (grant number: 23H03018 to Dr. Miyawaki). This study was also supported by grants from the Charitable Trust Mihara Cerebrovascular Disorder Research Promotion Fund to Dr. Miyawaki and grants from the MSD Life Science Foundation (Public Interest Incorporated Foundation) to Dr. Hongo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DS had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. DS and SM contributed equally to the works co-first authors. Concept and design: DS, SM, SD, TH, and YS. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: DS, SM, SD, HH, JM, YT, MD, KO, DI, YS, DI, and YK. Drafting of the manuscript: DS and SM. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: DS, SM, SD, HH, YT, KO, DI, YS, DI, YK. Statistical analysis: DS and SM. Obtained funding: SM, HH, and YS. Administrative, technical, or material support: SM, KN, TJ, HM, TK, YM, SD, and MD. Supervision: SM, HK, AN, NS, TH, MD, and YS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shimada, D., Miyawaki, S., Nakanishi, K. et al. RNF213 c.14429G > A (p.Arg4810Lys) is associated with non-arteritic retinal artery occlusion. Sci Rep 15, 35513 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19517-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19517-2