Abstract

Escalating levels of insecticide resistance and adaptive changes in mosquito populations threaten recent gains in malaria control. Understanding the molecular, ecological, and evolutionary processes driving these transformations is important for extending the effectiveness of current insecticides and informing the development of effective strategies and tools for vector control and insecticide resistance management. This study analyzed 103 whole-genome sequences from Anopheles funestus s.s. mosquitoes collected before the implementation of non-pyrethroid-based vector control tools in Kenya in 2017. Mosquito samples were collected from the western Kenya region (Bungoma, Migori and Kisumu Counties), the region with the highest malaria prevalence and the coastal region (Kilifi County), which has the second-highest malaria prevalence in Kenya. The study determined the population structure, evaluated the presence of insecticide-resistant alleles associated with pyrethroid insecticides and identified patterns of gene flow. Based on our results, Anopheles funestus s.s. from the western Kenya region were highly differentiated from the coastal population with a mean FST of 0.117 (P = 0.002). Genetic differentiation between the western and coastal regions is likely attributed to ecological and geographic barriers such as the Great Rift Valley, which may limit gene flow. The presence of selection signals at insecticide resistance loci and high frequencies of key cytochrome P450 genes, particularly at the Cyp6p rp1 locus and Cyp9k1, are major contributors to metabolic resistance to pyrethroids. Populations of An. funestus s.s. from western Kenya shared selection signals at the CYP6p rp1 on chromosome 2 and at the Cyp9k1 on the X chromosome, which were absent in the coastal region (Kilifi) samples. Anopheles funestus s.s. populations from coastal Kenya are genetically distinct from those in western Kenya, suggesting diverse bionomics and the critical need for region-specific vector control strategies. Increased pyrethroid resistance and negative Tajima’s D indicate a selective sweep, further highlighting the potential for vector resurgence. These findings emphasize the value of integrating genomics into routine An. funestus surveillance in Kenya.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vector control interventions such as the use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS) averted 79% of malaria cases between 2000 and 2015 in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)1. Despite increasing coverage of these tools, malaria remains the most prevalent vector-borne disease, resulting in 263 million cases in 83 malaria-endemic Countries in 2023, an increase of 11 million malaria cases compared to 2022, with 597,000 deaths2. Several countries in sub-Saharan Africa reported a resurgence of malaria prevalence post-2015 owing to a mix of factors influencing the transmission and infection efficiency of Anopheles species and Plasmodium falciparum3,4. The reasons associated with the resurgence of malaria include, but are not limited to the emergence and spread of vector resistance to insecticides5,6parasite resistance to antimalarial drugs and the deletion of histidine-rich protein 2 and 3 genes (HRP2/3)7; the occurrence of residual transmission attributed to behavioral changes in malaria vectors8,9; and lately, the emergence of invasive vector species such as Anopheles stephensi10.

The most significant malaria burden occurred in the WHO African region in 2023 with 94% and 95% of estimated malaria cases and deaths respectively, with an increase of 23 million cases and 24,000 deaths over the past five years in this region2. Kenya had 3,419,000 malaria cases and was ranked as the fourteenth country with the highest mortality, with more than 11,000 deaths reported in 20232. According to the Kenya Malaria Indicator Survey (KMIS) 2020, the country has a prevalence of 6% and three-quarters of the population is at risk of malaria, with the highest burden in lake (19%), and coastal (5%) malaria-endemic regions11. In these endemic parts of Kenya, the most predominant malaria vectors are Anopheles funestus sensu stricto (An. funestus s.s.), An. arabiensis and An. gambiae s.s.

Anopheles funestus densities in Kenya were greatly reduced following the distribution of ITNs in the early 2000s12but the vector has since resurged13 and phenotypically portrays high-intensity resistance to pyrethroid insecticides14. Anopheles funestus demonstrates remarkable adaptability and anthropophilic behavior. In some regions, it also possesses a higher vectorial capacity than Anopheles gambiae15. This, combined with its preference for stable, permanent breeding sites16,17suggests that An. funestus may have greater resilience to environmental change compared to Anopheles gambiae sensu lato (An. gambiae s.l.) This resilience poses a significant challenge to malaria control efforts, particularly given the ability of An. funestus to transmit malaria even during dry seasons.

In Africa, the widespread and sustained use of insecticides for malaria vector control has driven the rapid evolution of insecticide resistance in Anopheles funestus, a major malaria vector. This resistance is predominantly mediated by a complex interplay of molecular mechanisms. A key contributor is metabolic resistance, primarily involving the overexpression of detoxification enzymes such as cytochrome P450 monooxygenases and Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs)18. Specifically, elevated expression of genes within the Cyp6p cluster (e.g., Cyp6p9a, Cyp6p9b ), the Cyp9k1 gene, and GSTe2 has been strongly linked to the enhanced detoxification of pyrethroid insecticides across various An. funestus populations19,20. Target-site resistance also plays a crucial role. This includes kdr mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel (Vgsc) gene, whose emergence in An. funestus has been more recently documented21. Additionally, resistance to cyclodiene insecticides like dieldrin, mediated by mutations in the GABA receptor gene (Rdl), particularly the A296S substitution, has been reported in certain African populations22. Understanding the precise molecular drivers and their geographical distribution is therefore critical for developing and deploying effective, resistance-breaking interventions to sustain malaria control gains.

Genomic surveillance incorporating whole-genome sequencing (WGS) allows control programs to not only identify species and analyze genetic variation but also enables the detection of known and novel resistance alleles and loci in mosquito populations before the resistance allele becomes widespread23,24,25. This could lead to the implementation of tailored effective vector control strategies.

Despite the importance of Anopheles funestus in malaria transmission, detailed genomic insights into its population structure and resistance allele distribution across Kenya remain limited. To address this gap, we conducted whole-genome sequencing on 103 samples from western and coastal regions, aiming to identify key insecticide resistance markers for targeted vector control.

Results

Study specimens and geographic distribution

Our analysis examined 103 Anopheles funestus s.s. whole-genome sequences that passed quality control from the MalariaGEN vector observatory project. These specimens represented two distinct malaria-endemic regions: the western lake-endemic zone with 81 samples (Kisumu n = 37, Migori n = 23, Bungoma n = 21) and the coastal endemic zone with 22 samples (Kilifi County). This geographic distribution captures populations from Kenya’s highest and second-highest malaria burden regions, separated by approximately 700 km and the Great Rift Valley (see Fig. 1). All specimens originated from the 2012–2016 period, providing genomic data from vector populations after pyrethroid ITN and IRS scale-up but before the introduction of non-pyrethroid insecticides in operational control programs.

Map of Kenya showing sample collection sites and the Lake Malaria Endemic counties in western Kenya and coastal Malaria Endemic counties as categorized by the National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) in the Kenya Malaria Indicator Survey (KMIS) 2020. The map of Kenya indicating the sampling location was designed using Q-GIS 3.28. with the ocean and lake base layer derived from Natural Earth (http://www.naturalearthdata.com/, a free GIS data source). The GPS location data were collected using personal digital assistant (PDA) for mosquito sampling, and the county boundaries for Kenya were derived from AfricaOpendata (https://africaopendata.org/dataset/kenya-counties-shapefile).

Population structure

To understand the population structure of Anopheles funestus s.s. sampled in Kenya, we explored the genetic relatedness between samples from Kenya with a population of previously sequenced samples from neighboring Countries, Uganda and Tanzania. The principal Component Analysis (PCA) and neighbor-joining tree (NJT) analyses on the 2 L chromosome revealed distinct genetic clustering of Anopheles funestus s.s. populations. Specifically, populations from Kisumu, Bungoma and Migori counties in western Kenya grouped with the Uganda population. In contrast, the Kilifi county population from coastal Kenya clustered closely with the Tanzania population (Fig. 2A B and C). PCA distribution on the 2R, 3R and 3 L were impacted by the presence of autosomal inversions; 2Rh, 3Ra, 3Rb and 3La (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). We also observe distinct and unique karyotype frequencies on samples from coastal Kenya (Kilifi County) compared to western Kenya (Kisumu, Bungoma and Migori Counties) (Supplementary Fig. 2). These findings are consistent with the genetic differentiation FST analysis which indicates that An. funestus from western Kenya region are highly differentiated from the coastal population with a mean FST 0.117 (P = 0.002). Low FST (< 0.0005) was observed between Kisumu, Bungoma, and Migori counties in Kenya and Eastern Uganda. Conversely, populations from Kilifi County in Kenya and Morogoro in Tanzania show a much higher FST (~ 0.073–0.142) when compared to populations from Kisumu, Bungoma, Migori Counties and Eastern Uganda (Fig. 2D). These results collectively indicate a significant difference in population structure between An. funestus s.s. from the western and coastal regions of Kenya, suggesting reduced gene flow between these two regions.

(A) Map showing the sample collection location. (B) Principal component analysis showing the genetic structure of An. funestus s.s. population. (C) Neighbor joining tree comparing An. funestus s.s. population. The samples were colored by population cohort. (D) Pairwise FST between An. funestus s.s. population from Bungoma, Migori, Kisumu and Kilifi regions in Kenya, Eastern Uganda region and Morogoro in Tanzania.

Genetic diversity

Analysis of genetic diversity revealed 25.6 million segregating sites in An. funestus s.s. genome that passed quality filters (~ 11.4% of these sites were multiallelic). Approximately 23.1 million of these single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified on the autosomes and 2.5 million SNPs were identified on the X chromosome. We found high nucleotide diversity (θπ) in Kisumu (0.0134), Migori (0.0129) and Bungoma (0.0129) and a lower nucleotide diversity (θπ) in Kilifi (0.0093) (Fig. 3A). Watterson’s estimator, theta (θw) showed a similar trend, with higher values for Kisumu (0.0315), Migori (0.0294) and Bungoma (0.0295) and a lower value for Kilifi (0.0101) (Fig. 3B). The analysis demonstrated that nucleotide diversity (θπ) and Watterson’s theta (θw), were high and stable in An. funestus s.s. collected from the western region, potentially suggesting similar demographic histories among these populations. Conversely, An. funestus s.s. from the coastal region showed low diversity, suggesting a demographic history divergent from that of the western region. Genome-wide negative Tajima’s D values (Fig. 3C), indicating an excess of rare variants due to either positive selection or population expansion, were also observed in all populations but were significantly lower in the western region populations than in the coastal region population.

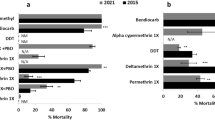

Insecticide resistance

An. funestus s.s. Population displays signatures of selection signals at Cyp6 rp1 gene cluster and Cyp9k1 gene loci associated with insecticide resistance

Selection signatures were present on the 2RL and X chromosomes but absent on the 3RL chromosome in all the populations. Populations from the western Kenya region shared selection signatures on chromosome 2RL within/near a major pyrethroid resistance locus containing a cluster of cytochrome P450 monooxygenases of the Cyp6 rp1 family as well as carboxylesterase genes (Fig. 4A, B and C). These clusters are under positive selection in both An. funestus and An. gambiae19,26. No selection signal in this genomic region was observed in the population from the coastal region (Fig. 4D and H).

Signatures of positive selection (Garud H12) in Kenyan Anopheles funestus s.s. populations. H12 values are shown for the 2RL chromosome (A–D) and the X chromosome (E–H). Elevated H12 values, indicative of positive selection, were detected in the Cyp6p rp1 gene region (2RL chromosome) and the Cyp9k1 gene region (X chromosome) within samples from western Kenya.

We also found evidence of a positive selection signal encompassing the Cyp9k1 gene on the X chromosome in populations from the western Kenya region (Fig. 4E, F and G) but not on the coast.

Differential distribution of the Cyp6 rp1 gene cluster and Cyp9k1 gene variants between Western and coastal Kenya An. funestus s.s. Populations

Copy number variations (CNVs) in key malaria vector resistance genes have been demonstrated to enhance insecticide resistance phenotypes in Anopheles gambiae and An. coluzzii26. Using the hidden Markov model (HMM), we examined CNV amplification and deletion in two critical genomic regions: the Cyp6 rp1 gene cluster and the cyp9k1 gene.

Within the Cyp6 rp1 gene cluster, we detected amplification of the LOC125764726 gene across populations from western Kenya (Bungoma, Kisumu, and Migori), with near-fixed amplification of (93.75%-100%), while Kilifi County on the coast of Kenya had a frequency of (81.83%). Additionally, we observed deletion of the LOC125764700 gene at variable frequencies (43.75-75%) throughout western Kenya, in contrast with the minimal presence (4.55%) in the coastal region (Supplementary Fig. 3). Our analysis also revealed several SNP variants (T262I, A125T, E426K, V418L, D315E, A160S, S154A, and T151S) that warrant further investigation to determine their contribution to insecticide resistance in Anopheles funestus s.s. (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Analysis of the cyp9k1 region revealed complete duplication of the LOC125764232 gene throughout western Kenya populations, while this duplication was entirely absent in Kilifi County on the coast (Supplementary Fig. 5). Furthermore, we detected the G454A SNP mutation in the cytochrome P450 Cyp9k1 gene at near-fixation (98–100%) in western Kenya populations, compared to a significantly lower frequency (18%) in coastal populations (Fig. 5).

Diplotype clustering analysis of the Cyp6 rp1 gene cluster and Cyp9k1 gene revealed genetic differentiation between coastal and Western Kenya An. funestus s.s. Populations

Diplotype clustering analysis revealed two distinct major groupings based on heterozygosity, CNVs and nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms. Samples from Kilifi exhibited high heterozygosity, indicating genetic differentiation from the Kisumu, Bungoma and Migori populations. While both geographical groups shared similar CNV frequencies at the LOC125764726 locus, western Kenya populations exhibited unique high-frequency SNPs, notably A125T and T262I, which were absent or less frequent in coastal samples. Evidence of a selective sweep was detected in samples from Kisumu, Migori, and Bungoma (western Kenya region), suggesting shared genetic material and gene flow among these western populations but not extending to Kilifi on the coast (Fig. 6A). This pattern indicates regional genetic isolation between the coastal and western An. funestus s.s. populations despite sharing some resistance-associated genetic elements.

Diplotype clustering of (A) Cyp6 rp1 and (B) Cyp9k1 the gene cluster of An. funestus s.s. population from Kenya. The clustering dendrogram is accompanied by heterozygosity in shades of blue, SNP frequency in shades of grey and copy number variant frequencies in shades of brown. Clusters with low sample heterozygosity or inter-sample distances of zero are indicative of a selective sweep. The substitutions present in each individual are shown with blocks of the same colour indicating a shared variant. The darker the shade the higher the frequency.

Further analysis of diplotype clustering at the cyp9k1 gene (LOC125764232) on the X chromosome revealed distinct regional patterns. In addition, western Kenya samples had low heterozygosity coupled with high CNV, while coastal samples exhibited high heterozygosity with no CNVs detected. Additionally, the G454A SNP was fixed in western Kenya populations but occurred at low frequencies in coastal Kenya. These patterns further support the genetic differentiation between coastal and Western Kenya An. funestus s.s. populations. The evidence of a selective sweep across the western Kenya cohort (Kisumu, Migori, and Bungoma) indicates shared genetic material and ongoing gene flow among these western populations, contrasting with their isolation from the coastal population (Fig. 6B).

Discussion

The evolution of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors represents one of the most pressing challenges facing contemporary vector control programs, particularly as resistance mechanisms become increasingly sophisticated and geographically heterogeneous. While much research has focused on identifying resistance alleles and understanding their biochemical functions, the population-level dynamics that govern how these alleles spread across landscapes remain poorly understood. Geographic barriers, ecological gradients, and differential selection pressures can create complex evolutionary scenarios where neighboring vector populations may follow divergent resistance trajectories, ultimately undermining the effectiveness of uniform control strategies. Understanding these spatial patterns of resistance evolution is essential for developing sustainable vector management approaches that account for local population dynamics and can adapt to the evolutionary responses of target species. The implications extend beyond immediate control efficacy to encompass fundamental questions about how landscape features shape pathogen transmission networks and influence the long-term sustainability of public health interventions. The results of this study provide insights into the genetic structure of An. funestus s.s. revealing a clear differentiation between populations from two geographically distinct regions of Kenya: the western and coast regions. Using genetic analyses, specifically principal component analysis (PCA), neighbor-joining tree (NJT), and the fixation index (FST), we found significant genetic differentiation between mosquito samples collected from the western Kenya region (comprising Bungoma, Kisumu, and Migori) and those from the coastal region (Kilifi). These results suggest that the genetic makeup of An. funestus s.s. populations from these regions is distinct. The distinction is potentially shaped by ecological and geographical factors. These factors appear to limit gene flow implying potential differences in bionomics consistent with An. arabiensis strains found in the same region27.

One of the most prominent physical barriers between the western Kenya and the coastal region of Kenya is the Great Rift Valley, a massive geological feature that spans much of the country from north to south. This geographical divide likely plays a critical role in restricting gene flow between populations in these two regions. The observed population structure of An. funestus s.s. is consistent with findings from earlier studies on An. funestus s.l.28,29,30 and An. arabiensis31which have also suggested that the Great Rift Valley serves as a significant barrier to genetic exchange among mosquito populations. In addition to acting as a physical barrier, the Great Rift Valley likely influences mosquito population differentiation through a variety of environmental factors. Differences in climate, vegetation, and habitat suitability, as observed in Anopheles arabiensis27contributed to the isolation of populations and enhanced the observed genetic divergence. This isolation across such a significant geographic feature has potential implications for malaria transmission dynamics within Kenya11. Local adaptations may arise, affecting both vectorial capacity and the effectiveness of control measures. However, our current analysis focused solely on the genetic characteristics of these populations, and further research is necessary to fully explore these broader ecological and epidemiological effects.

The observed negative Tajima’s D values across all cohorts suggest an abundance of rare genetic variants, potentially resulting from positive selection or recent population expansion. This pattern, coupled with the increase in insecticide resistance detected, indicates the recent resurgence of Anopheles funestus s.s. as the dominant malaria vector in Kenya. An. funestus species are predominantly anthropophilic, endophilic, and endophagic32making them highly susceptible to insecticide pressure from indoor-based vector control measures(ITNs and IRS). Historically, prior to the large-scale implementation of ITNs in the late 1990s, An. funestus s.s. was the primary malaria vector in Kenya13. The introduction of pyrethroid-treated ITNs significantly reduced the population size and led to a marked decline in malaria incidence, particularly in western Kenya, where cases dropped by 73% between 2008 and 2015, coinciding with large-scale ITN distributions13,33. However, despite high ITN coverage, reports of malaria resurgence post-2016 have emerged9. This trend mirrors similar patterns observed in East and Southern Africa, where increasing malaria prevalence has been linked to insecticide-resistant An. funestus s.s. populations3,4,15. These findings underscore the need to address the challenges posed by insecticide resistance and the resurgence of An. funestus s.s. in malaria control efforts.

The resurgence of An. funestus s.s. as the dominant malaria vector in Kenya can also be attributed to its increasing resistance to pyrethroids, the primary class of insecticides used in ITNs and IRS13. Results from this study suggest that key cytochrome P450 genes, particularly Cyp6p rp1 and Cyp9k1, play a significant role in conferring metabolic resistance to pyrethroids in An. funestus s.s. populations in Kenya. Although genome wide selection scan (GWSS) did not show any signal of selection at Cyp6p rp1 and Cyp9k1 for samples from the coast, diplotype clustering indicated low frequencies of SNPs and CNVs with high heterozygosity suggesting that there is some resistance in this population, however, resistance has not yet been established as compared to that in the western Kenya region.

The presence of recent selection signals and duplication of cytochrome P450 genes within Cyp6p rp1 locus in the western Kenya region can be linked to the enhanced detoxification of pyrethroids34reducing their efficacy and compromising the impact of ITNs. This locus, which is part of the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase family, is involved in breaking down pyrethroid molecules, thereby allowing An. funestus to survive exposure to insecticide-treated surfaces35. Upregulation of Cyp6p rp1 gene, is particularly prevalent in regions where ITN coverage is high, indicating strong selection pressure exerted by vector control interventions36,37.

Similarly, another cytochrome P450 gene family member, Cyp9k1, has emerged as a critical resistance marker, contributing to both metabolic and target-site (single mutation G454A that increases the catalytic effect of metabolizing pyrethroids) resistance mechanisms in the western Kenya region. Its overexpression in Kenyan An. funestus s.s. populations further underscore the adaptive response of this vector to sustained insecticide pressure. The role of Cyp9k1 in pyrethroid resistance has been well documented, with evidence suggesting its ability to metabolize pyrethroids and DDT insecticides reducing bed net efficacy20,38,39. These findings align with studies in sub-Saharan Africa that reported widespread insecticide resistance driven by the selection of resistance genes, including Cyp6p rp1 and Cyp9k136,39. The emergence of such resistance mechanisms poses a significant challenge to current malaria control strategies. While ITNs remain a critical intervention, the effectiveness of pyrethroids is increasingly undermined by the metabolic resistance conferred by these genes. The persistence of resistant An. funestus s.s. population highlights the urgent need for integrated vector management (IVM) approaches that involves the combination of alternative insecticide classes, innovative control tools, and resistance monitoring. For instance, the introduction of next-generation bednets incorporating piperonyl butoxide (PBO) synergists, which inhibit cytochrome P450 activity40could mitigate the impact of metabolic resistance mediated by Cyp6p rp1 and Cyp9k1.

In the western Kenya region, the observed selective sweeps at Cyp6p rp1 and Cyp9k1 indicate recent positive selection most likely driven by intense insecticide pressure. The widespread use of ITNs which dates back to the early 2000s12 and IRS, which dates from as early as 200541 in this region likely exerted strong selection pressure on An. funestus s.s., favoring individuals with mutations or overexpression of these genes. This selective advantage has led to a significant reduction in genetic variation around the Cyp6p rp1 and Cyp9k1 loci, a hallmark of selective sweeps. The presence of these selective sweeps in the western Kenya region, coupled with evidence of gene flow, suggested that resistant alleles have spread across local populations, enhancing the fitness of An. funestus s.s. under continued insecticide exposure. This gene flow may have been facilitated by the movement of resistant individuals between geographically connected populations, particularly in areas with overlapping breeding sites and human activity that promotes vector migration such as Kisumu Migori and Bungoma in western Kenya as demonstrated by this analysis.

In contrast, An. funestus s.s. populations from the coastal Kenya show a different evolutionary trajectory. This is indicated by the lack of selection sweeps at Cyp6p rp1 and Cyp9k1, despite the region having the second highest malaria burden in the country and relying on pyrethroid ITNs for vector control. This absence may be attributed to lower levels of insecticide pressure, reduced gene flow, or differences in the ecological and operational context of vector control interventions. While the precise mechanisms underlying these differences require further investigation beyond the scope of the current study, we propose several potential factors. For instance, variations in ITN coverage, agricultural insecticide usage, or environmental factors such as breeding habitats may have limited the selection and spread of resistance alleles in coastal populations. Additionally, the genetic isolation of An. funestus s.s. populations in the coastal region may have restricted the movement of resistant alleles observed in the western Kenya region.

The contrasting patterns between the western and coastal regions underscore the complex interplay between local selection pressures, gene flow, and ecological factors in shaping the evolution of insecticide resistance. The strong selection sweeps observed in the western Kenya region highlight the urgent need for region-specific vector control strategies that address the spread of resistance alleles. In particular, monitoring the spread of resistance alleles at Cyp6p rp1 and Cyp9k1 through genomic surveillance will be critical for understanding the dynamics of resistance evolution and gene flow.

Conclusion

This study underscores the importance of considering geographical and ecological barriers when evaluating the impact of population structure and evolutionary dynamics of malaria vectors in Kenya such as Anopheles funestus s.s. The genetic distinctness observed between populations in different regions highlights the need for region-specific strategies in the monitoring and control of this vector.

Our findings demonstrate the adaptive evolution of Anopheles funestus under insecticide pressure, evidenced by high CNV and SNP of key metabolic resistance genes, Cyp6p rp1 and Cyp9k1. This adaptive response, particularly evident in the western region where selection sweeps were detected, signifies the strong impact of sustained insecticide pressure and the role of gene flow in spreading resistance alleles. In contrast, the absence of selective sweeps in the coastal region highlights regional variation in insecticide pressure and evolutionary responses.

These findings emphasize the necessity for targeted, region-specific interventions and resistance management strategies to effectively address the growing challenge of insecticide resistance. Sustaining malaria control in Kenya will require continued surveillance of resistance markers, diversification of insecticide-based tools, and the development of innovative approaches to mitigate the impact of metabolic resistance mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

The Anopheles funestus s.s. samples used in this study were obtained from archived mosquitoes collected as part of nationwide malaria surveillance. The collections were from two malaria endemic regions namely, the western region, which comprises Migori (34.596, − 0.686); Kisumu (34.920, − 0.174); Bungoma (34.543, 0.980); and the coastal region which comprises of Kilifi (39.909, − 3.511) in Kenya. The mosquitoes were collected between 2012 and 2016, prior to the implementation of non-pyrethroid IRS in Kenya32using indoor pyrethroid spray collection (PSC) and larval sampling method. PSC was done using 0.025% Pyrethrum and 0.1% piperonyl butoxide mixed in kerosene to knock down mosquitoes collected from Kisumu County between 0600 and 1100 h. In Migori, Bungoma and Kilifi mosquitoes were collected from multiple habitats using standard larval 350 ml dipper. The larvae were then transported to the insectary lab and reared to adults. Larvae were reared in rainwater at a temperature between 28℃ and 31℃ and humidity between 75% and 85%. After collection, the mosquito samples were morphologically identified using morphological keys42. The mosquito legs of the samples morphologically identified as An. funestus were DNA extracted according to Collins et al., 198743 and identified to species using PCR44. The remaining body parts were preserved individually in Eppendorf tubes in -20 ℃ freezers.

The main agricultural practice in the Western Kenya region is large scale rice farming in Ahero Kisumu and sugarcane farming in Migori and Bungoma utilizing large amounts of chemical fertilizers on farms45. Malaria transmission peaks in these two regions during long rains from April to June, with small peaks following the short rains between October and November. The daily annual average maximum temperature was 25.5 °C, and the minimum temperature was 16.1 °C, while the coastal region had temperatures of 29.2 °C and 25.3 °C respectively. The rainfall averages were 8.7 mm/day and 4.5 mm/day in the western and coastal regions of Kenya, respectively, and daily humidity averaging 74% and 80% respectively. These weather patterns create ideal conditions for malaria vector proliferation, potentially leading to year-round malaria transmission in these areas. The weather data are derived from the 2023 NASA prediction of worldwide energy resources (https://power.larc.nasa.gov/).

Whole genome sequencing

The study samples were processed following the Anopheles funestus genome surveillance MalariaGEN Vector Observatory project (https://www.malariagen.net/mosquito). Detailed methods for DNA extraction, sequence data processing, variant calling and population quality control can be found in Bodde et al. 202446. Briefly, the mosquito sample were DNA extracted using nondestructive Buffer C47 and lysate purified using Qiagen MinElute kit. Extracted DNA was quantified using Quant-iT picogreen dsDNA assays (ThermoFisher Scientific™) following manufacturer protocols. Standard library preparation was performed beginning shearing to 450 bp using a Covaris LE220 instrument. Purification by SPRlselect Beads on alignment Bravo station. Library construction using a custom protocol for the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina on an Agilent Bravo Workstation Finally, tagging with KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix and custom Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) primers with Illumina UDI 1–96 barcodes. Pools containing 30 individual samples were whole-genome-sequenced on three lanes of an Illumina HiSeq X10 platform using PE150 kits, targeting for 30x coverage per individual. The reads were aligned to the An. funestus reference genome AfunGA148 with MalariaGEN alignment and genotyping pipeline version 0.0.7.49. Genotypes were independently called for each sample, in genotyping mode, given all possible alleles at all genomic sites where the reference base was not “N.” Identifying high-quality SNPs and haplotypes was conducted using BWA mem version 0.7.15 and GATK version 3.7. Quality control involved the removal of samples with low mean coverage with a threshold minimum coverage of 10%, as a conservative estimate 85% of the reference genome was covered by at least 1 read. removing samples with an estimated maximum of 4.5% cross-contaminated sites, running PCA to identify and remove population outliers, and sex confirmation by calling the sex of all samples based on the modal coverage ratio between the X chromosome and the autosomal chromosome arm 3RL of between 0.4 and 0.6 for males and 0.8 and 1.2 for females.

Data analysis

For seamless access and analysis of genomic data, MalariaGEN-data package (https://github.com/malariagen/malariagen-data-python) version 14.0.0, the scikit-allele (https://github.com/cggh/scikit-allel) version 1.3.13 and the python standard data management package version 3.9.1 were used. This approach eliminates the need for manual download, streamlining the process and enhancing the efficiency of data exploration and analysis. Additionally, the use of the MalariaGEN-data package facilitated access to the reference data for An. funestus, which included not only the reference genome but also the transcripts of all the identified genes within the mosquito genome. Such comprehensive access ensures holistic exploration of the genomic landscape and gene expression within An. funestus.

Population structure

To investigate the genetic relationship of Kenyan Anopheles funestus s.s. to populations across East Africa, we compared them with 49 previously sequenced individuals from Eastern Uganda and 10 from Morogoro, Tanzania, utilizing publicly available MalariaGEN Af1.0 data46. We performed a PCA dimensionality reduction on the allele count of 200,000 biallelic SNPs equally distributed across chromosome 2 L (2RL:58,200,000-102,882,611) reported to be free of polymorphic chromosomal inversions. The chosen SNPs had a minor allele frequency of ≥ 0.02 and no missing data. We then compared the genetic relationships of East African An. funestus s.s. using the same criteria of SNP selection by constructing an unrooted neighbour-joining tree with a city-block distance metric. To determine whether An. funestus s.s. from East Africa were connected, we quantified the genetic differences between populations using Hudson’s pairwise FST50. To further explore the demographic history of Kenyan An. funestus s.s., we calculated key genetic diversity metrics at a 95% confidence interval by randomly down-sampling to 20, which is the size of the cohort with the least samples. These metrics included Nucleotide diversity (θπ), Watterson’s theta (θW) and Tajima’s D. All the analyses were conducted using the open source malariagen_data package.

Selection scans using H12

Exposure to insecticides imposes considerable selective pressure on mosquito populations, resulting in genetic signatures of positive directional selection (such as diminished genetic diversity and an abundance of rare variants). This phenomenon aids in identifying and delineating genomic regions linked to resistance. We posit that insecticide pressure likely represents the most potent recent selective pressure acting on mosquito populations, thereby underlying the most significant selection signals.

A genome wide selection scan was conducted following Garud H12 statistics, and the H12 homozygosity statistic was calculated51 across windows of the genome using the malariagen_data python package. The optimal window size was chosen for each population cohort by plotting the values produced for each window and identifying the distribution of H12 values less than 0.1 for the 95th percentile. The statistical peaks in H12 represent either a hard or soft sweep. We also plotted the difference in the observed H12 values between individual cohorts. A significant peak in H12 indicates differential selection acting on the cohorts.

Insecticide resistance

We used the malariagen_python package to calculate the frequency of amino acid substitutions at Cyp6 rp1 (the LOC125764726, LOC125764682, LOC125764700, LOC125764717, LOC125764714, LOC125764712 and LOC125764711 among other trascript) and cyp9k1 (LOC125764232 transcript), which are genes associated with pyrethroid insecticide resistance in Anopheles funestus. To minimize the impact of sequencing errors and focus on substitutions likely under selection, we retained only amino acid substitutions present at a frequency greater than 5% in at least one population. Copy number variation (CNV) frequency analysis was performed on the cyp6p gene cluster (2RL: 8.61 Mbp – 8.73 Mbp) and the cyp9k1 gene (X:8.38–8.51 Mbp) using the gene_cnv_frequencies function from the malariagen_data_package API https://malariagen.github.io/malariagen-data-python/latest/index.html via the Hidden Markov Model (HMM)23. Only CNV frequencies greater than 5% were retained in at least one population.

Diplotype clustering

To explain the patterns of selection, hierarchical clustering of diplotypes was conducted using city block (Manhattan) genetic distance with complete linkage methodology. Diplotype clusters exhibiting low heterozygosity indicate selection pressure acting on specific haplotypes. To identify variants associated with these clusters, we mapped the observed amino acid substitutions and copy number variations (CNVs) onto the resulting dendrogram, enabling visualization of their distribution patterns across the genetic clusters52.

Inversion karyotype

We determined the chromosomal inversion karyotypes of our mosquito samples following the method described in Bodde et al. 202446. In brief, In silico inversion was performed by establishing distinct thresholds on PC1 and PC2 to delineate and assign individual samples to three karyotypic states: homozygous inverted, heterozygous, and homozygous standard. This method previously applied to Kisumu Bungoma and Migori populations (AF1.0 release), was extended to determine the karyotypes of our Kilifi samples. For Kilifi, PCA was conducted on the genomic regions containing the inversions 2Ra (2RL: 25,458,000–29,454,000), 2Rh (2RL: 29,517,507 − 39,362,207), 3Ra (3RL: 2,219,305 − 12,234,590), 3Rb (3RL: 21,361,107 − 34,095,918), and 3La (3RL: 57,224,763 − 76,882,000). The resulting Kilifi PCA clusters were then compared known karyotype clusters from the other locations to verify the corresponding karyotypes.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in ENA repository (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/home) BioProjects PRJEB1670 and PRJEB2141 and from the *Anopheles* Genome Variation Project and Vector Observatory Project. The ENA accession IDs for each sample can be found in Supplementary Table 1. The processed data can be accessed through the malariagen_data python API (https://malariagen.github.io/malariagen-data-python/latest/index.html) with the following 2 sample sets 1232-VO-KE-OCHOMO-VMF00044 and AG1000G-KE.

References

Bhatt, S. et al. The effect of malaria control on plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature 526 (7572), 207–211 (2015).

WHO World. Malaria Reoprt 2024 (World Health Organization, 2024). https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2024.

Abiodun, G. J. et al. Investigating the resurgence of malaria prevalence in South Africa between 2015 and 2018: a scoping review. Open Public. Health J ;13(1). (2020).

Epstein, A. et al. Resurgence of malaria in Uganda despite sustained indoor residual spraying and repeated long lasting insecticidal net distributions. PLOS Glob Public. Health. 2 (9), e0000676 (2022).

Coetzee, M. & Koekemoer, L. L. Molecular systematics and insecticide resistance in the major African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 393–412 (2013).

Liu, N. Insecticide resistance in mosquitoes: impact, mechanisms, and research directions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 60, 537–559 (2015).

Fola, A. A. et al. Plasmodium falciparum resistant to Artemisinin and diagnostics have emerged in Ethiopia. Nat. Microbiol. 8 (10), 1911–1919 (2023).

Odero, J. I. et al. Early morning anopheline mosquito biting, a potential driver of malaria transmission in Busia county, Western Kenya investigators. Published online 2023.

Omondi, S. et al. Late morning biting behaviour of Anopheles funestus is a risk factor for transmission in schools in siaya, Western Kenya. Published online 2023.

Ochomo, E. et al. Detection of Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes by molecular surveillance, Kenya. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 29 (12), 2498 (2023).

Kenya Malaria Indicator Survey. Division of National Malaria Programme (DNMP) [Kenya] and ICF. Nairobi, Kenya and Rockville, Maryland, USA: DNMP and ICF; 2021. Division of National Malaria Programme (DNMP) [Kenya] and ICF. Nairobi, Kenya and Rockville, Maryland, USA: DNMP and ICF; 2021. (2020).

Gimnig, J. E. et al. Impact of permethrin-treated bed Nets on entomologic indices in an area of intense year-round malaria transmission. Published online 2003.

McCann, R. S. et al. Reemergence of Anopheles funestus as a vector of plasmodium falciparum in Western Kenya after long-term implementation of insecticide-treated bed Nets. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 90 (4), 597 (2014).

Agumba, S. et al. Experimental hut and field evaluation of a metofluthrin-based Spatial repellent against pyrethroid-resistant Anopheles funestus in Siaya county, Western Kenya. Parasit. Vectors. 17 (1), 6 (2024).

Msugupakulya, B. J. et al. Changes in contributions of different Anopheles vector species to malaria transmission in East and Southern Africa from 2000 to 2022. Parasit. Vectors. 16 (1), 408 (2023).

Li, L., Bian, L., Yakob, L., Zhou, G. & Yan, G. Temporal and Spatial stability of Anopheles Gambiae larval habitat distribution in Western Kenya highlands. Int. J. Health Geogr. 8, 1–11 (2009).

Nambunga, I. H. et al. Aquatic habitats of the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in rural south-eastern Tanzania. Malar. J. 19, 1–11 (2020).

Assatse, T. et al. Anopheles funestus populations across Africa are broadly susceptible to neonicotinoids but with signals of possible Cross-Resistance from the GSTe2 gene. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 8 (5). https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8050244 (2023).

Weedall, G. D. et al. An Africa-wide genomic evolution of insecticide resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus involves selective sweeps, copy number variations, gene conversion and transposons. PLoS Genet. 16 (6), e1008822 (2020).

Hearn, J. et al. Multi-omics analysis identifies a CYP9K1 haplotype conferring pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in East Africa. Mol. Ecol. 31 (13), 3642–3657 (2022).

Odero, J. O. et al. Discovery of Knock-Down resistance in the major African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Mol. Ecol. 33 (22), e17542. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.17542 (2024).

Wondji, C. S. et al. Identification and distribution of a GABA receptor mutation conferring dieldrin resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in Africa. Spec. Issue Toxicol. Resist. 41 (7), 484–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.03.012 (2011).

Lucas, E. R. et al. Copy number variants underlie major selective sweeps in insecticide resistance genes in Anopheles arabiensis. PLoS Biol. 22 (12), e3002898. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002898 (2024).

Nagi, S. C. et al. Parallel evolution in mosquito Vectors—A duplicated esterase locus is associated with resistance to Pirimiphos-methyl in Anopheles Gambiae. Mol. Biol. Evol. 41 (7), msae140. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msae140 (2024).

Odero, J. O. et al. Genetic markers associated with the widespread insecticide resistance in malaria vector Anopheles funestus populations across Tanzania. Parasit. Vectors. 17 (1), 230 (2024).

Lucas, E. R. et al. Genome-wide association studies reveal novel loci associated with pyrethroid and organophosphate resistance in Anopheles Gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 4946 (2023).

Polo, B. et al. Genomic surveillance reveals geographical heterogeneity and differences in known and novel insecticide resistance mechanisms in Anopheles arabiensis across Kenya. BMC Genom. 26 (1), 599. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-025-11788-3 (2025).

Djuicy, D. D. et al. CYP6P9-Driven signatures of selective sweep of metabolic resistance to pyrethroids in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus reveal contemporary barriers to gene flow. Genes 11 (11), 1314 (2020).

Koekemoer, L. L. et al. Impact of the rift Valley on restriction fragment length polymorphism typing of the major African malaria vector Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 43 (6), 1178–1184 (2006).

Ogola, E. O., Odero, J. O., Mwangangi, J. M., Masiga, D. K. & Tchouassi, D. P. Population genetics of Anopheles funestus, the African malaria vector, Kenya. Parasit. Vectors. 12, 1–9 (2019).

Kamau, L. et al. Analysis of genetic variability in Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles Gambiae using microsatellite loci. Insect Mol. Biol. 8 (2), 287–297 (1999).

Dulacha, D. et al. Reduction in malaria burden following the introduction of indoor residual spraying in areas protected by long-lasting insecticidal Nets in Western kenya, 2016–2018. Plos One. 17 (4), e0266736 (2022).

Nyawanda, B. O. et al. The relative effect of climate variability on malaria incidence after scale-up of interventions in Western kenya: A time-series analysis of monthly incidence data from 2008 to 2019. Parasite Epidemiol. Control. 21, e00297 (2023).

Mugenzi, L. M., Tekoh, A. & Ibrahim, T. S. The duplicated P450s CYP6P9a/b drive carbamates and pyrethroids cross-resistance in the major African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. PLoS Genet. 19 (3), e1010678 (2023).

Sandeu, M. M., Mulamba, C., Weedall, G. D. & Wondji, C. S. A differential expression of pyrethroid resistance genes in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus across Uganda is associated with patterns of gene flow. Plos One. 15 (11), e0240743 (2020).

Ibrahim, S. S. et al. Pyrethroid resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus is exacerbated by overexpression and overactivity of the P450 CYP6AA1 across Africa. Genes 9 (3), 140 (2018).

Yunta, C. et al. Cross-resistance profiles of malaria mosquito P450s associated with pyrethroid resistance against WHO insecticides. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 161, 61–67 (2019).

Djoko Tagne, C. S. et al. A single mutation G454A in P450 CYP9K1 drives pyrethroid resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus reducing bed net efficacy. bioRxiv. Published online 2024:2024-04.

Vontas, J. et al. Rapid selection of a pyrethroid metabolic enzyme CYP9K1 by operational malaria control activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115 (18), 4619–4624 (2018).

Joseph, R. N. et al. Insecticide susceptibility status of Anopheles Gambiae mosquitoes and the effect of pre-exposure to a piperonyl butoxide (PBO) synergist on resistance to deltamethrin in Northern Namibia. Malar. J. 23 (1), 77 (2024).

Kenya Malaria Indicator Survey. Division of Malaria Control [Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation], Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, and ICF Macro. Nairobi, Kenya: DOMC, KNBS and ICF Macro.; 2011. Division of Malaria Control [Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation], Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, and ICF Macro. Nairobi, Kenya: DOMC, KNBS and ICF Macro.; 2011. (2010).

Gillies, M. T. & Coetzee, M. A supplement to the anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara. Publ Afr. Inst. Med. Res. 55, 1–143 (1987).

Collins, F. H. et al. A ribosomal RNA gene probe differentiates member species of the Anopheles Gambiae complex. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 37 (1), 37–41 (1987).

Koekemoer, L., Kamau, L., Hunt, R. & Coetzee, M. A cocktail polymerase chain reaction assay to identify members of the Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66 (6), 804–811 (2002).

Russo, T., Tully, K., Palm, C. & Neill, C. Leaching losses from Kenyan maize cropland receiving different rates of nitrogen fertilizer. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems. 108, 195–209 (2017).

Bodde, M. et al. Genomic diversity of the African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. bioRxiv. Published online January 1, 2024:2024.12.14.628470. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.12.14.628470.

Korlević, P. & Lawniczak, M. SOP - Lysis C plate based DNA extraction. Published online January 26, (2023). https://www.protocols.io/view/sop-lysis-c-plate-based-dna-extraction-ewov1o3molr2/v1.

Ayala, D. et al. The genome sequence of the malaria mosquito, Anopheles funestus, giles, 1900. Wellcome Open. Res 7. (2022).

MalariaGEN Pipelines, v0.0.7 Release. (Github). Published online December 11, (2021). https://github.com/malariagen/pipelines/releases

Hudson, R. R., Slatkin, M. & Maddison, W. P. Estimation of levels of gene flow from DNA sequence data. Genetics 132 (2), 583–589 (1992).

Garud, N. R., Messer, P. W., Buzbas, E. O. & Petrov, D. A. Recent selective sweeps in North American drosophila melanogaster show signatures of soft sweeps. PLoS Genet. 11 (2), e1005004 (2015).

Nagi, S. C. et al. Parallel evolution in mosquito vectors-a duplicated esterase locus is associated with resistance to pirimiphos-methyl in An. gambiae. bioRxiv. Published online 2024:2024-02.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Grand Challenges Grant No. INV024969 and Investment Grant OPP1210769 to E.O. This study was also supported by MalariaGEN, an international collaboration working to build the capacity of malaria vector genomics research and surveillance. It involves contributions by the following teams: Wellcome Sanger Institute: Lee Hart, Kelly Bennett, Anastasia Hernandez-Koutoucheva, Jon Brenas, Menelaos Ioannidis, Chris Clarkson, Alistair Miles, Julia Jeans, Paballo Chauke, Victoria Simpson, Eleanor Drury, Osama Mayet, Sónia Gonçalves, Katherine Figueroa, Tom Maddison, Kevin Howe, Mara Lawniczak; Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine: Eric Lucas, Sanjay Nagi, Martin Donnelly; Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT: Jessica Way, George Grant; Pan-African Mosquito Control Association: Jane Mwangi, Edward Lukyamuzi, Sonia Barasa, Ibra Lujumba, Elijah Juma. The authors would like to thank the staff of the Wellcome Sanger Institute Sample Logistics, Sequencing, and Informatics facilities for their contributions.The MalariaGEN Vector Observatory is supported by multiple institutes and funders. The Wellcome Sanger Institute’s participation was supported by funding from Wellcome (220540/Z/20/A, ‘Wellcome Sanger Institute Quinquennial Review 2021-2026’) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (INV-001927). The Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine’s participation was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases ([NIAID] R01-AI116811), with additional support from the Medical Research Council (MR/P02520X/1). The latter grant is a UK-funded award and is part of the EDCTP2 programme supported by the European Union. Martin Donnelly is supported by a Royal Society Wolfson Fellowship Martin Donnelly is supported by a Royal Society Wolfson Fellowship funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (INV-031595). The findings and conclusions within this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions or policies of the funders listed above.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EO, JM, AM and ML conceptualized and supervised this project.BP, EO, SM, DNO, CAO, JN, AM, DO, MB and ML designed the study, identified and processed the samples.BP, EO, DO, SM, DNO, SN, AM, JN, AM, LK, DO, MB and ML conducted data analysis and interpretation and assisted in drafting the manuscript.All authors read, reviewed and approved of this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this trial was obtained from the Kenya Medical Research Institute Ethics Review Committee (KEMRI/SERU/3875).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Polo, B., Milanoi, S., Omoke, D.N. et al. Genetic isolation drives divergent insecticide resistance between coastal and western Kenya Anopheles funestus populations. Sci Rep 15, 35920 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19795-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19795-w