Abstract

Extensive dam development and climate change have altered seasonal stage variation patterns, which are critical to residents in the riparian zone along the Lancang–Mekong River. However, the effects of morphological changes and reservoirs on stage variability are not clear due to data-scarce fluvial systems. In this work, discharge and water level data from five hydrological stations (1960–2020) were acquired to assess temporal shifts in rating curves during different disturbance periods. The contribution of channel geometry adjustment to the stage variance of the extreme flow regime under high- and low-flow conditions were empirical analysed by rating-curve method. Analysis revealed that the stage variance along the main channel was modulated by channel geometry adjustment under both high- and low-flow conditions, even though discharge was the dominant factor. Moreover, the degree of modulation resulting from geometric adjustment varied under different flow and reach conditions, which varied in the ranges of -0.57 ~ 0.27 m and − 0.41 ~ 0.39 m under low- and high-flow conditions, respectively. Furthermore, an inverse channel geometry adjustment response was observed for 60% of the high-flow conditions versus 40% of the low-flow conditions. The Luang Prabang–Vientiane reach was transitional in terms of the effects of channel geometry adjustment on stage variation. Our findings quantified how channel geometry adjustment modulated water levels across various extreme regimes, offering insights into the morphological processes of data-scarce river reaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Lancang–Mekong (LM) River basin has experienced increasing extremes in its hydrological properties, with intensified flood‒drought cycles posing systemic risks to human security and socioecological systems 1,2,3,4,5. The 2000 megaflood, which was a catastrophic event, resulted in 800 fatalities and inundations of thousands of hectares of agricultural land across Cambodia and Vietnam 5,6. These perturbations disproportionately impact over 20 million residents in the riparian zone who work in the flood recession agriculture and capture fishery industries; these peoples’ livelihoods are highly sensitive to stage variability across discharge regimes 7,8,9,10,11.

Floods in the LM river basin have undergone pronounced changes since 1950, with significant increases in the frequency and magnitude of floods 12. Anthropogenic modifications, including dams, infrastructure (interbasin transfers and diversions) and similar disturbances (land use changes, digging, and sand extraction), have fundamentally altered the seasonal variations in the water level 13,14,15,16. Moreover, since 2008, the frequencies and magnitudes of floods at different locations in the LM River have declined to varying degrees as anthropogenic modifications increased, with the greatest decline occurring in the upper reaches 16. Analyses of climate models have shown that precipitation should increase in the river basin, and the flood flow, water level and inundated area should increase as well, which indicates an increase in the flood risk 17,18,19,20,21,22. Moreover, reservoir operation (i.e., flood control and dry season augmentation) reduces downstream flooding and increases water levels under drought conditions to varying degrees, but it may not be sufficient to offset the increase in flooding caused by climate change 16,17,18,19. Therefore, effective assessment of future flood‒drought risk requires a comprehensive understanding of the hydrogeomorphic relationship of the LM River under changing conditions.

Despite the urgent need to understand the hydrogeomorphic characteristics along the main stream of the LM River, the morphological effects on stage variability and the different effects of reservoirs under extreme flow regimes are not clear as those under data-scarce fluvial systems (see Supplementary Table S1 online). For example, Chua and Lu 23 analysed the water level change due to channel alternation during the dry season and wet season, and the analysed water level change considered the gap between the two stage curves over the entire range of discharge. The discharge range during wet season is indicated by the minimum discharge and maximum discharge from June to November, while the range during dry season is indicated by the minimum discharge and maximum discharge from December to May. In addition, the scholars focused only on Chiang Saen, Mukdahan and Pakse, which is insufficient for describing the effects of climate change and human activities on stage variation in the main stream of the river reach. However, the impacts of climate change and reservoir operation on the flow regime differ spatially and monthly along the main stream 1,24,25,26. For example, climate change increases the variability of preflood streamflow (with a maximum increase in magnitude of 18%), while reservoir operations replenish dry season flows (flow from July to November, with magnitudes decreasing from 34.5 to 36% at 660 km) and reduce extremely high pulses (flow from January to May, with magnitudes decreasing from − 9.5 to − 8% at 660 km) 24. Therefore, understanding the hydrogeomorphic relationship (the contribution of channel geometry adjustment to stage variance under extreme flow regimes and the different effects of reservoirs) along the main stream of the LM River can benefit the management and risk prediction of water resources under low- and high-flow conditions, which are key for adaptive watershed management 27,28,29.

Stage–discharge rating curves (RCs) serve as critical hydrodynamic indicators for channel geometry adjustment 30,31. Their temporal evolution provides diagnostic evidence of cumulative geomorphic change 32,33. In data-scarce systems such as the LM River 27, RC analysis offers a proxy approach for quantifying morphological controls of stage variability 34,35. This study is aimed at partitioning hydrological and geomorphic contributions to stage variation across discharge regimes (extreme flow regimes during high-flow and low-flow conditions) in the LM River. First, the studied reach of the LM river and the hydrological data (water level and discharge) from the five selected hydrological stations are presented. Second, a method for exploring the contributions of changes in discharge and channel geometry adjustments to stage variation is presented. Finally, the contributions of changes in discharge and channel geometry adjustments to stage variations in the extreme flow regime under high-flow and low-flow conditions are analysed and discussed.

Study area, data and methodology

Studied river reach

The length of the main stream of the LM River is 4909 km 36. This river originates on the Qinghai‒Tibet Plateau, and it runs through China, Myanmar, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR), Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam before flowing into the South China Sea. This monsoonal system exhibits extreme hydrologic seasonality 37, and the annual discharge varies considerably 17.

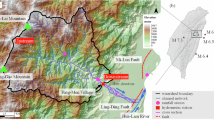

Five benchmark hydrological stations along the main stream of the LM River were selected (Fig. 1) on the basis of longitudinal representativeness and data continuity (> 60 year daily records with < 7% missing values). Chiang Saen is located on the Thai–Myanmar border. The Chiang Saen–Luang Prabang reach and Luang Prabang–Vientiane reach constitute the upper part of the Mekong River, whereas the Vientiane–Mukdahan reach and Mukdahan–Pakse reach constitute the middle reaches.

Data

Hydrometric time series (daily discharge and water level) spanning 1960–2020 were acquired from the Mekong River Commission (MRC) (https://portal.mrcmekong.org/) for the five benchmark stations (Chiang Saen, Luang Prabang, Vientiane, Mukdahan and Pakse) (Table 1, see Supplementary Fig. S1 online). The dataset exhibits two temporal discontinuities: Luang Prabang records were discontinued after 2018, and Vientiane observations were unavailable in 2016. The consistency and accuracy of water level data were checked by the MRC 38. This dataset has been widely employed to analyse the geographical and hydrologic conditions in relevant river regions (see Supplementary Table S1 online) 12,39.

Changing the location of hydrological stations leads to inconsistencies in water level data. Thus, the water level measured at Chiang Saen after 15 December 1993 should have been reduced by 0.62 m after the hydrological station Chiang Saen was moved in 1993 40. In addition, the water level data measured during September and October 2006 at Chiang Saen were notably abnormal 41, and the data measured during this period were removed. The water level data drawn from this website were above the corresponding local datum, and these data were modified to metres above sea level according to the values provided by the MRC http://ffw.mrcmekong.org/.

The LM river basin has undergone phased reservoir development. The cumulative storage capacity before 1992 was rather small (for example, the Manwan reservoir was commissioned on 30 June 1993). Until 2007 (for example, the Dachashao reservoir was commissioned in 2003), the total capacity of reservoirs was limited (only 20 km3), and the cumulative storage capacity accounted for only 2% of the annual discharge at Pakse 16,42. After 2008 (for example, the Xiaowan reservoir was commissioned in September 2009, the Nuozhadu reservoir was commissioned in September 2012, the Xayaburi reservoir was commissioned in 2019, and the Don Sahong hydropower plant was commissioned in 2019), the cumulative storage capacity increased to 400 km3 in 2015, accounting for 22% of the annual runoff at Pakse 38,42,43,44,45. Therefore, in this study, the discharge series was divided into three different periods to compare the effects of reservoirs (see Supplementary Fig. S2 online): the reference period (Period I, pre-1992), the low-intensity disturbance period (Period II, 1993–2007) and the high-intensity disturbance period (Period III, 2008–2020).

Methodology

The RC methodology served as a critical proxy for reconstructing channel morphodynamics in data-scarce fluvial systems 46. This approach has been successfully implemented for flood risk 47 and water resource management 48. To quantify multidecadal stage variations under evolving channel geometry, the RC form was as follows:

where WL is the water level (m); Q is the discharge (m3/s); and parameters a, b, and c are coefficients estimated via the nonlinear method in the MATLAB curve fitting toolbox. The coefficient of determination is denoted as R2.

Following the method of Mei et al. 49, the stage variation during each period compared with the previous period was analysed. As shown in Fig. 2, Q1is the value of discharge during the reference period, and Q2 is the value of discharge during the study period. For the reference period, WL1 is the water level of Q1, whereas WL3 is the water level of Q2. For the study period, WL2 is the water level of Q2. Thus, WL3–WL1 is the change in water level associated with the change in discharge (i.e., the discharge decreases from Q1 to Q2), with a negative value indicating a decrease in the water level as the discharge decreases. WL2–WL3 is the change in water level associated with changes in channel geometry (the same discharge of Q2 with a changed RC), where a positive value indicates an increased water level due to channel geometry adjustment. Thus, WL2–WL1 indicates a decreased water level as a combined effect of changes in both discharge and channel geometry.

Schematic diagram of the method used to determine the change in water level. Q1 and Q2 are the average values in the reference and study periods, respectively. Under high-flow conditions, Q1 and Q2 are the averages of the extreme flow regime. Under low-flow conditions, Q1 and Q2 are the averages of the extreme flow regime. WL3–WL1 is the change in water level associated with the change in discharge, where a negative value indicates a decrease in the water level as the discharge level decreases. WL2–WL3 is the change in water level caused by a changed channel geometry, and a positive value indicates an increase in the water level caused by channel geometry adjustment. The change in RC is a combined effect of discharge and channel geometry adjustment.

The 1-day maximum (\({\text{Q}}_{1\text{d}}\)) and 90-day maximum (\({\text{Q}}_{90\text{d}}\)) discharges were chosen as the extreme flow regimes during high-flow conditions, and the 1-day minimum (\({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\)) and 90-day minimum (\({\text{Q}}_{90\text{m}}\)) discharges were chosen as the extreme flow regimes under low-flow conditions 33,45. The values in each period were calculated as follows:

where \({Q}_{i,k}\) indicates the measured discharge of the \(i\)–th day in the \(k\)–th year, the subscript d indicates the maximum value, the subscript m indicates the minimum value, the subscript k indicates the k-th year, and \(N\) indicates the number of years.

Results

Hydrological variation

The RCs for the five hydrological stations exhibited spatiotemporal divergence across the three periods (Fig. 3; the parameters are shown in Supplementary Table S2 online). The hysteretic RC shifts revealed specific hydrological responses to disturbances. At the same water level, the discharge levels at Chiang Saen and Pakse were the highest in Period III and lowest in Period I, whereas Mukdahan exhibited the opposite pattern. Moreover, the Luang Prabang and Vientiane stations showed different water level‒discharge relationships between the study periods (with the highest discharge for a given depth occurring in Periods I and II, respectively), confirming that the RCs differed in space and time between the LM reaches.

The spatiotemporal evolution of the extreme flow regime (high-flow and low-flow conditions) revealed contrasting responses across the LM River (Fig. 4, see Supplementary Table S3 online). The \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{d}}\) and \({\text{Q}}_{90\text{d}}\) discharges at Chiang Saen, Vientiane and Pakse decreased significantly after 2007 (− 8 ~ − 38%), whereas the discharges of \({\text{Q}}_{1d}\) and \({\text{Q}}_{90d}\) at Luang Prabang and Mukdahan remained relatively unchanged after 1992 (− 5 ~ 8%). The \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\) and \({\text{Q}}_{90\text{m}}\) discharges along the Chiang Saen–Pakse reach increased significantly after 2007 (9% ~ 80%). Lu and Chua 41 reported similar results. Our results suggested flow regime homogenization in the LM River as the difference in the extreme flow regime between the high-flow (maximum) and low-flow (minimum) conditions decreased, especially in the river reach around Chiang Saen.

Extreme flow regime under high-flow and low-flow conditions from 19,602,020 at hydrological stations: Chiang Saen (a), Luang Prabang (b), Vientiane (c), Mukdahan (d) and Pakse (e). The dashed lines are the mean discharges (\({\text{Q}}_{1\text{d}}\), \({\text{Q}}_{90\text{d}}\), \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\) and \({\text{Q}}_{90\text{m}}\)) for Periods I, II, and III.

Contribution to water level changes

The hydrogeomorphic attribution framework (Fig. 5) quantifies the relative contribution of discharge versus channel geometry adjustment to stage variations in \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{d}}\). The contributions to stage variations for \({\text{Q}}_{90\text{d}}\), \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\) and \({\text{Q}}_{90\text{m}}\) are summarized in Supplementary Table S4. The analyses below are based on the calculated water levels.

Changes in the water levels for \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{d}}\) at Chiang Saen (a), Luang Prabang (b), Vientiane (c), Mukdahan (d) and Pakse (e) during Periods I, II and III. The dashed bars are the corresponding water levels of \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{d}}\) during Periods I, II and III. The water level change is divided into contributions by discharge (indicated by green bars) and channel geometry adjustment (indicated by red bars). The numbers above/below the bars are the values of the water level or water level change.

The contribution to stage variation by channel geometry adjustment at the Chiang Saen–Pakse reach varies in the ranges of − 0.57 ~ 0.27 m under low-flow conditions and − 0.41 ~ 0.39 m under high-flow conditions. In comparison, the stage variation linked to discharge varies in the ranges of − 0.37 ~ 1.3 m under low-flow conditions and − 2.36 ~ 0.66 m under high-flow conditions (see Supplementary Table S4 online). This finding indicates that stage variations along the main stream of the LM River under both high-flow and low-flow conditions are caused mainly by discharge.

The spatiotemporal patterns of geometry-driven stage adjustments reveal three distinct response regimes (Fig. 6).

Heatmap of changes in water level under high-flow and low-flow conditions in Periods II and III. Changes in the combined (i.e., influenced by both discharge and channel geometry adjustment) water level (a and b) and changes in the water level linked to channel geometry adjustment (c and d) at the five hydrological stations are shown.

The stage variation ranges linked to channel geometry adjustment under low-flow conditions at these five hydrological stations are 0.02 ~ 0.23 m for Chiang Saen, − 0.57 ~ 0.27 m for Luang Prsabang, − 0.33 ~ 0.17 m for Vientiane, − 0.35 ~ –0.12 m for Mukdahan, and − 0.18 ~ 0.12 m for Pakse, whereas the corresponding ranges under high-flow conditions are 0 ~ 0.32 m for Chiang Saen, − 0.37 ~ 0.25 m for Luang Prabang, − 0.07 ~ 0.39 m for Vientiane, − 0.41 ~ − 0.25 m for Mukdahan, and 0.05 ~ 0.35 m for Pakse. Channel geometry adjustments under high-flow and low-flow conditions after 1992 increase the water level in the river reach around Chiang Saen and decrease the water level in the river reach around Mukdahan (Fig. 6c and d). The results suggest that the river reach of Luang Prabang–Vientiane is a transitional reach in terms of the effects of channel geometry adjustment on water level changes. Specifically, under both low-flow and high-flow conditions, the water level linked to channel geometry adjustment at Vientiane is positive during Period II (Fig. 6c), whereas it is negative during Period III (Fig. 6d). This finding indicates that the effects of reservoirs on the variation in water level are linked to channel geometry adjustment.

Overall, discharge is a dominant factor influencing stage variation at the five hydrological stations under both high-flow and low-flow conditions (Fig. 6, see Supplementary Table S4 and Supplementary Fig. S3 online), whereas the contribution of channel adjustment modulates it. The proportion of channel geometry adjustment that corresponds to a counteractive adjustment of stage variation differs under different conditions, with values of 60% and 40% under low-flow and high-flow conditions, respectively.

Discussion

Our analyses show the modulation of channel geometry adjustment to stage variation along the main stream of the LM River under both high-flow and low-flow conditions. The uncertainties and implications are discussed in this section.

Uncertainties

Stage variability emerges from the coupled effects of discharge and channel morphodynamics 32. RC extrapolation is associated with uncertainties due to multiple sources of error (17 ~ 37% for automated river gauges) 28,46,50,51,52. The uncertainties of RCs are greater during flood events 27,53. For example, the RCs for floods lasting several days vary during the rising and falling periods. However, the uncertainties are minimized by the use of reliable daily discharge data. The daily discharge data analysed here are estimated on the basis of updated RCs 54,55, and the quality of the data is assured 56. The daily calculated discharge has been considered the observed discharge when measured data are not available. For example, Räsänen et al. 56 used the calculated discharge at Chiang Saen for the period 1960–1990 as the observed discharge. Uncertainties can be partially examined by comparing the calculated water levels with the measured values (Fig. S4). The difference between the calculated and observed water levels is limited, and the difference under high-flow conditions (in the range of − 0.09 ~ 0.14 m) is greater than that under low-flow conditions (in the range of − 0.03 ~ 0.06 m). Importantly, the relative errors induced by the RC curve uncertainties are considerably smaller than the magnitudes of the changes in the \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{d}}\) and \({\text{Q}}_{90\text{d}}\) water levels. For example, the change in the water level for \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{d}}\) at Chiang Saen under high-flow conditions after 2010 is − 2.25 ~ − 1.24 m, and the value for \({\text{Q}}_{90\text{d}}\) at Chiang Saen under high-flow conditions from 2008 to 2020 is − 1.55 ~ − 1.44 m; these values are variable but considerably larger than the RC uncertainty values in this study and in the literature 23,41.

With many more dams being constructed in the future 57,58, RCs should be updated accordingly with field surveys to make more accurate discharge estimates and minimize the influences of these uncertainties. And the satellite-derived morphology and flume experiments should be analyzed to directly address morphology-stage linkages.

Implications for high-flow conditions

The effects of channel geometry adjustments on changes in water levels can be discussed even with these uncertainties.

Under high-flow conditions, the positive change in water level along the Chiang Saen–Mukdahan reach in Period II switches to a negative change in Period III (Fig. 6). The positive change in water level that is linked to discharge along Chiang Saen–Luang Prabang under high-flow conditions (0.06 ~ 0.66 m in Period II) is transformed into a negative change (− 2.36 ~ 0.93 m in Period III). Moreover, the changes in water levels under low-flow conditions (\({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\)) linked to channel geometry adjustments along the Luang Prabang–Vientiane reach, which vary from positive (0.12 ~ 0.18 m in Period II) to negative (− 0.53 ~ − 0.33 m in Period III), follow the same pattern. A sharp decrease in discharge at Chiang Saen under high-flow conditions in Period III (larger than 30%) indicates that the stream power and sediment load are reduced because of the effects of upstream dams. There is a corresponding reduction in the effects on channel geometry adjustment. The limited decrease in discharge along Luang Prabang–Mukdahan under high-flow conditions in Period III (less than 10%) indicates that the effects of sediment trapping and discharge attenuation are reduced by upstream dams. Our results indicate that channel geometry adjustment has a modulating effect, with the exception of the effect of discharge on water level changes, which decreases in the reach around Luang Prabang and almost disappears in the reach downstream at Vientiane.

Erosion in the Chiang Saen–Mukdahan reach under high-flow conditions is related to the differences in the suspended sediment loads compared with those under mean conditions. For example, the suspended sediment loads around the Chiang Saen River reach under high-flow conditions in Period I range from 350 to 1200 mg/L, whereas the values decrease during Period II 59,60.

In addition to changes in channel geometry adjustment (e.g., riverbed erosion and deposition and bank erosion) and stream power 61, geometric constraints may contribute to the effects of channel geometry adjustment on changes in the water level 62,63,64,65. For the river cross section at the Chiang Saen hydrological station (Fig. 7, see Supplementary Fig. S5 online, cross-sectional data from Hou 2021 37), the water levels for \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{d}}\) in Periods I and II are higher than those of the bankfull elevation (water stage of 1.5 return period discharge 66); these characteristics differ from those of Period III (Fig. 7). There are also planform changes in the river reach around hydrological stations (see Supplementary Fig. S6 online), and this planform change in the river reach also contributes to the stage variation as well 67.This finding indicates that at Chiang Saen, the hydrodynamic properties of floods and the effects of channel geometry adjustments on water level changes differ during Period III.

Water level and threshold of bank full elevation at Chiang Saen. For \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{d}}\) and \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\), both the measured and calculated water levels are illustrated, whereas only those calculated for \({\text{Q}}_{90\text{d}}\) and \({\text{Q}}_{90\text{m}}\) are illustrated. The bankfull elevation are estimated by 1.5 return period discharge (363.89–364.25 m). The cross-sectional data are drawn from Hou, S.Y. (2021).

Implications for low-flow conditions

Water levels for \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\) under low-flow conditions in Period II decrease along the Chiang Saen–Luang Prabang reach (− 0.09 m for Chiang Saen and − 0.18 m for Luang Prabang) and increase along the Vientiane–Pakse reach (0.01 m for Vientiane, 0.11 m for Mukdahan, and 0.21 m for Pakse). An increase in the annual sediment load along the Mukdahan–Pakse reach (Fig. 8; data from Wang 2008 68, Wang et al. 2011 69 and Liu et al. 70) leads to a positive change in water levels along the Mukdahan–Pakse reach in Period II. For the reach around Vientiane, the erosion of river islands (near the Vientiane hydrological station) is severe (0.6 m/a for 1961–1992 and 6.4 m/a for 1992–2005) 71. This severity results in increased stream power at Vientiane, which attenuates the effects of a small decrease in \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\) (− 6%, see Supplementary Table S3 online) in Period II and leads to a limited increase in water levels (0.01 m) under low-flow conditions. Similarly, there are sediment-contributing areas in the Chiang Saen–Luang Prabang reach in Periods I and II due to the expansion of cultivated land and plantations 70. However, the effects of decreased \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\) (− 20%, see Supplementary Table S2 online) for the reach around Chiang Saen outweigh the increased annual sediment load (Fig. 8a) in Period II. For the reach around Luang Prabang, the effects of decreased \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\) (− 17%, see Supplementary Table S3 online) lead to a large change in water level (− 0.18 m), whereas the related channel geometry adjustments include the erosion of islands and bars as the LM River has a stable bank line 71. This finding suggests that the effects of channel geometry adjustment downstream from the Vientiane hydrological station (namely, the Vientiane–Pakse reach) on the water level offset the effects of increased suspended sediment load. Cochrane et al. 40 reported a diminished effect of dams, which is negligible at Vientiane.

Water levels for \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\) under low-flow conditions from 2008 to 2020 increased along Chiang Saen–Pakse (0.48 ~ 0.56 m for Chiang Saen, 0.54–0.62 m for Luang Prabang, − 0.02 m for Vientiane, 0.28 ~ 0.37 m for Mukdahan, and 0.15 ~ 0.35 m for Pakse). The stage variations in \({\text{Q}}_{90\text{m}}\) along the Chiang Saen–Luang Prabang reach after 1992 are positive: 0.12 ~ 0.66 m for Chiang Saen and 0.14 ~ 0.73 m for Luang Prabang. The water levels under low-flow conditions along the Vientiane–Pakse reach have increased after 1992: − 0.02 ~ 0.23 m for Vientiane, 0.11 ~ 0.41 m for Mukdahan, and 0 ~ 0.55 for Pakse. In total, the stage variation along the Chiang Saen–Pakse reach under low-flow conditions is influenced mainly by discharge (see Supplementary Fig. S3 online), and the channel has a homogenized flow regime (Fig. 4) and reduced erosive capacity (from runoff changes) during the high-intensity disturbance period.

During the high-intensity disturbance period (2008–2020), the change in the water level linked to channel geometry adjustment at Chiang Saen (0 ~ 0.11 m) was limited. Under low-flow conditions, the change in the water level of \({\text{Q}}_{90\text{m}}\) discharge at Chiang Saen during the low–intensity disturbance period (1993–2007) was variable at + 0.12 ~ 0.202 m, whereas the change in the water level of \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\) discharge during the high-intensity disturbance period (2008–2020) was 0.48–0.56 m, as shown in the literature and this study 41,48. Moreover, the stage variation in \({\text{Q}}_{1\text{m}}\) discharge linked to channel geometry adjustment was 0.06 m during the high-intensity disturbance period (2008–2020). The reported percentage contribution of channel geometry adjustment to water level change by Lu and Chua 41 was 4% at Chiang Saen (3.53 m water level from 20,102,020 versus 3.37 m water level from 19,601,991). Channel geometry adjustment around Chiang Saen station has mainly been caused by new sandbar formation resulting from bedload transport 59.

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to explore the magnitude and range of the contribution of channel geometry adjustment to stage variance along the main stream of the LM River under an extreme flow regime. Therefore, historical daily discharge and water levels at five hydrological stations (Chiang Saen, Luang Prabang, Vientiane, Mukdahan and Pakse) from 1960–2020 were acquired. Four parameters (1-day maximum discharge, 90-day maximum discharge, 1-day minimum discharge, and 90-day minimum discharge) were adopted to represent the historical extreme flow regimes under high- and low-flow conditions. Variations in RCs were adopted to distinguish the effects of discharge and channel geometry adjustment on water level variation. The conclusions were as follows:

-

(1)

Overall, under high-flow conditions, the water level along the Chiang Saen–Mukdahan reach decreased between 1960 and 2020. Our analysis revealed that the water level increased between 1993 and 2007 (low-intensity disturbance period) but decreased with increasing magnitude between 2008 and 2020 (high-intensity disturbance period). However, the change in the water level under low-flow conditions varied across different reaches and different flow conditions. Overall, the results differed between the reaches upstream and downstream from the Luang Prabang reach.

-

(2)

Our analysis revealed that discharge was the dominant factor influencing stage variance under both high-flow and low-flow conditions along the main stream of the LM River, whereas it was further modulated by channel geometry adjustment. Our analysis showed that the modulation by channel geometry adjustment varied under high-flow and low-flow conditions. The modulation by channel geometry adjustment at minimum discharge varied in the range of − 0.57 ~ 0.27 m (0.02 ~ 0.23 m for Chiang Saen, − 0.57 ~ 0.27 m for Luang Prabang, − 0.33 ~ 0.17 m for Vientiane, − 0.35 ~ − 0.12 m for Mukdahan and − 0.18 ~ − 0.12 m for Pakse). Moreover, the modulation by channel geometry adjustment under high-flow conditions varied in the range of − 0.41 ~ 0.39 m (0 ~ 0.32 m for Chiang Saen, − 0.37 ~ 0.25 m for Luang Prabang, − 0.07 ~ 0.39 m for Vientiane, − 0.41 ~ − 0.25 m for Mukdahan and 0.05 ~ 0.35 m for Pakse).

-

(3)

Across the five hydrological stations analysing the four extreme flow regimes, inverse channel geometry adjustment responses (opposing water level trends) were observed in 60% of the high-flow conditions versus in 40% of the low-flow conditions. In addition, the river reach of Luang Prabang–Vientiane was a transitional reach in terms of the effects of channel geometry adjustment on water level changes under an extreme flow regime.

At Chiang Saen, changes in discharge and limited channel geometry adjustment influenced by upstream dams, along with cross-sectional geometry, could contribute to stage variation, and field surveys could further verify these claims. Luang Prabang–Vientiane was considered a transitional reach, as the combined effect (discharge, sediment and sediment–discharge regimes) on the change in water level decreased in the Luang Prabang reach and almost disappeared downstream at the Vientiane reach.

Data availability

Data from the Mekong River Commission (MRC) (https://portal.mrcmekong.org/) were utilized for the analysis in this study.

References

Long, D., Han, Z. Y. & Wang, Y. M. Projection of future droughts across the Lancang-Mekong River under a changing environment. Adv. Water Sci. 33(5), 766–779 (2022).

Gong, G.Q. Evolution trends and driving mechanisms of flash droughts under changing environment in the Lancang-Mekong River Basin. South University of Science and Technology (2024).

Palanisamy, B. et al. Development and propagation of hydrologic drought from meteorological and agricultural drought in the Mekong River Basin. Hydrol. Process. 37(7), e14935. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.14935 (2023).

Chen, X. R., Wang, X. Y. & Bai, Y. B. Analysis of spatial and temporal distribution of flood losses in Mekong River basin since 1962. J. Catastrophol. 34(1), 113–116. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-811X.2019.01.021 (2019).

Chen, X. R., Wang, X. Y. & Bai, Y. N. Flood and drought losses in Mekong River basin. J. Econ. Water Resour. 37(1), 54–58. https://doi.org/10.3880/j.issn.1003-9511.2019.01.010 (2019).

Hou, S. Y. et al. Potential role of coordinated operation of transboundary multi-reservoir system to reduce flood risk in the Lancang-Mekong River basin. Adv. Water Sci. 32(1), 68–78 (2021).

Sok, S., Chhinh, N., Hor, S. & Nguonphan, P. Climate change impacts on rice cultivation: A comparative study of the Tonle Sap and Mekong River. Sustainability 13(16), 8979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168979 (2021).

Sok, T., Oeurng, C., Ich, I., Sauvage, S. & Sanchez-Perez, J. M. Assessment of hydrology and sediment yield in the Mekong River Basin using SWAT model. Water 12(12), 3503. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12123503 (2020).

Liu, H. et al. Drought in Lancang-Mekong River basin and the impact of upstream reservoirs. J. China Inst. Water Resourc. Hydropower Res. 18(6), 479–485. https://doi.org/10.13244/j.cnki.jiwhr.20200058 (2020).

Chinh, D. T., Gain, A. K., Dung, N. V., Haase, D. & Kreibich, H. Multi-variate analyses of flood loss in Can Tho City, Mekong Delta. Water 8(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/w8010006 (2015).

Arias, M. E. et al. Impacts of hydropower and climate change on drivers of ecological productivity of Southeast Asia’s most important wetland. Ecol. Model. 272, 252–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2013.10.015 (2014).

Pokhrel, Y. et al. A review of the integrated effects of changing climate, land use, and dams on Mekong riverical. Water 10(3), 266 (2018).

Yuan, X. et al. Influence of cascade reservoir operation in the Upper Mekong River on the general hydrological regime: A combined data-driven modeling approach. J. Environ. Manag. 324, 116339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116339 (2022).

Phung, D. et al. Hydropower dams, river drought and health effects: A detection and attribution study in the lower Mekong Delta Region. Clim. Risk Manag. 32, 100280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100280 (2021).

Hecht, J. S., Lacombe, G., Arias, M. E., Dang, T. D. & Piman, T. Hydropower dams of the Mekong River basin: A review of their hydrological impacts. J. Hydrol. 568, 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.10.045 (2019).

Yun, X. et al. Impacts of climate change and reservoir operation on streamflow and flood characteristics in the Lancang-Mekong River basin. J. Hydrol. 590, 125472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125472 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Impacts of summer monsoons on flood characteristics in the Lancang-Mekong River Basin. J. Hydrol. 604, 127256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.127256 (2022).

Yun, X. et al. Can reservoir regulation mitigate future climate change induced hydrological extremes in the Lancang-Mekong River Basin?. Sci. Total Environ. 785, 147322 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Flood Inundation in the Lancang-Mekong River Basin: Assessing the Role of Summer Monsoon. J. Hydrol. 612, 128075 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Dam construction in Lancang-Mekong River Basin could mitigate future flood risk from warming-induced intensified rainfall. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44(20), 10378–10386 (2017).

Try, S. et al. Comparison of gridded precipitation datasets for rainfall-runoff and inundation modeling in the Mekong River Basin. PLoS ONE 15(1), e0226814 (2020).

Triet, N. V. K. et al. Future projections of flood dynamics in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Sci. Total Environ. 742, 140596 (2020).

Chua, S. D. X. & Lu, X. X. What can stage curves tell us about water level changes? Case study of the Lower Mekong Basin. CATENA 216, 106385 (2022).

Liu, H. Q. et al. Projection of the impact of climate change and reservoir on the flow regime in the Yangtze River basin. Acta Geogr. Sin. 80(1), 41–60 (2025).

Zhang, D. D., Dai, M. L., Li, Y. Q., Chen, X. & Wang, H. Influence of upstream cascade reservoir impoundment on the water level in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River. J. Water Resour. Res. 10(1), 74–82 (2021).

Su, C. et al. Lateral seepage scope of downstream of Yellow River after the operation of Xiaolangdi reservoir and its impact on groundwater environment. Geol. China 48(6), 1669–1680 (2021).

Gensen, M. R. A., Warmink, J. J., Berends, K. D., Huthoff, F. & Hulscher, S. J. M. H. Improving rating curve accuracy by incorporating water balance closure at river bifurcations. J. Hydrol. 610, 127958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.127958 (2022).

Krajewski, A., Banasik, K. & Sikorska, A. E. Stormflow and suspended sediment routing through a small detention pond with uncertain discharge rating curves. Hydrol. Res. 50, 1177–1188 (2019).

Kim, Y., Oh, S., Lee, S., Byun, J. & An, H. Application of stage-fall-discharge rating curves to a reservoir based on acoustic doppler velocity meter measurement data. Water 13, 2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13172443 (2021).

Budhathoki, B. R. et al. Application of hydrological models to streamflow estimation at ungauged transboundary Himalayan River basin, Nepal. Hydrol. Res. 55(9), 859–872. https://doi.org/10.2166/nh.2024.026 (2024).

Jalbert, J., Mathevet, T. & Favre, A. C. Temporal uncertainty estimation of discharges from rating curves using a variographic analysis. J. Hydrol. 397(1–2), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2010.11.031 (2011).

Ma, H. B. et al. Amplification of downstream flood stage due to damming of fine-grained rivers. Nat. Commun. 13, 3054. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30730-9 (2022).

Binh, D. V., Kantoush, S. & Sumi, T. Changes to long-term discharge and sediment loads in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta caused by upstream dams. Geomorphology 353, 107011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2019.107011 (2020).

Liu, C., He, Y., Li, Z. W., Chen, J. & Li, Z. J. Key drivers of changes in the sediment loads of Chinese rivers discharging to the oceans. Int. J. Sediment Res. 36, 747–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsrc.2020.05.0051001-6279 (2021).

Binh, D. V. et al. Long-term alterations of flow regimes of the Mekong River and adaptation strategies for the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2020.100742 (2020).

Liu, S., Lu, P., Liu, D. & Jin, P. D. Pinpointing source of Mekong and measuring its length through analysis of satellite imagery and field investigations. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 10, 51–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11806-007-0011-6 (2007).

Hou, S.Y. Research on characteristics of water and sediment and their responses to environment changes in Lancang-Mekong River basin. PhD Thesis, Tsinghua University (2021).

MRC The Council Study: Study on the sustainable management and development of the Mekong River, including impacts of mainstream hydropower projects, BioRA Final Tech. Rep. Ser. Vol. 4 Assess. Plan. Dev. Scenar. MRC Vientiane Lao PDR 145 (2017).

Gunawardana, S. K., Shrestha, S., Mohanasundaram, S., Salin, K. R. & Piman, T. Multiple drivers of hydrological alternation in the transboundary Srepok River Basin of the Lower Mekong Region. J. Environ. Manag. 278, 111524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111524 (2021).

Cochrane, T. A., Arias, M. E. & Piman, T. Historical impact of water infrastructure on water levels of the Mekong River and the Tonle Sap system. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 4529–4541. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-4529-2014 (2014).

Lu, X. X. & Chua, S. D. X. River discharge and water level changes in the Mekong River: Droughts in an era of mega-dams. Hydrol. Process. 35, e14265. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.14265 (2021).

Tang, Y. & Wang, Z. G. Derivation of the relative contribution of the climate change and human activities to mean annual streamflow change. J. Hydrol. 595, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125740 (2021).

Chua, S. D. X., Lu, X. X., Oeurng, C., Sok, T. & Grundy-Warr, C. Drastic decline of flood pulse in the Cambodian floodplain (Mekong River and Tonle Sap system). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 26, 609–625. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-26-609-2022 (2022).

Chua, S. D. X. & Lu, X. X. Sediment load crisis in the Mekong River Basin: Severe reductions over the decades. Geomorphology 419, 108484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2022.108484 (2022).

Binh, V. D. et al. Effects of riverbed incision on the hydrology of the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Hydrol. Process. 35, e14030. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.14030 (2021).

Pedersen, Ø., Aberle, J. & Rüther, N. Hydraulic scale modelling of the rating curve for a gauging station with challenging geometry. Hydrol. Res. 50(3), 825 (2019).

Bormann, H., Pinter, N. & Elfert, S. Hydrological signatures of flood trends on German rivers: Flood frequencies, flood heights and specific stages. J. Hydrol. 404(1–2), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.04.019 (2011).

Petaccia, G. & Fenocchi, A. Experimental assessment of the stage-discharge relationship of the Heyn siphons of Bric Zerbino dam. Flow Meas. Instrum. 41, 36–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flowmeasinst.2014.10.012 (2015).

Mei, X. F. et al. Modulation of extreme flood levels by impoundment significantly offset by floodplain loss downstream of the Three Gorges Dam. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 3147–3155. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL076935 (2017).

Hrafnkelsson, B. et al. Generalization of the power-law rating curve using hydrodynamic theory and Bayesian hierarchical modeling. Environmetrics 33, e2711 (2022).

Haile, A. T., Geremew, Y., Wassie, S., Fekadu, A. G. & Taye, M. T. Filling streamflow data gaps through the construction of rating curves in the Lake Tana sub-basin. Nile basin. J. Water Clim. Chang. 14(4), 1162. https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2023.372 (2023).

Fortesa, J. et al. Comparison of stage/ discharge rating curves derived from different recording systems: consequences for streamflow data and water management in a Mediterranean island. Sci. Total Environ. 665, 968–981 (2019).

Di Baldassarre, G. & Montanari, A. Uncertainty in river discharge observations: a quantitative analysis. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 13, 913–921 (2009).

Galelli, S., Dang, T. D., Ng, J. Y., Chowdhury, A. F. M. K. & Arias, M. E. Opportunities to curb hydrological alterations via dam re-operation in the Mekong. Nat. Sustain. 5, 1058–1069 (2022).

Arias, M. E., Piman, T., Lauri, H., Cochrane, T. A. & Kummu, M. Dams on Mekong tributaries as significant contributors of hydrological alterations to the Tonle Sap Floodplain in Cambodia. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 5303–5315 (2014).

Räsänen, T. A. et al. Observed river discharge changes due to hydropower operations in the Upper Mekong Basin. J. Hydrol. 545, 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.12.023 (2017).

Grumbine, R. E. Using transboundary environmental security to manage the Mekong River: China and South-East Asian Countries. Int. J. Water Resour. D. 34(5), 792–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2017.1348938 (2018).

MRC. Development of Guidelines for Hydropower Environmental Impact Mitigation and Risk Management in the Lower Mekong Mainstream and Tributaries. Mekong River Comm, Vientiane Lao PDR (2015).

Wood, S. H., Ziegler, A. D. & Bundarnsin, T. Floodplain deposits, channel changes and riverbank stratigraphy of the Mekong River area at the 14th-Century city of Chiang Saen, Northern Thailand. Geomorphology 101, 510–523 (2008).

Lu, X. X. & Siew, R. Y. Water discharge and sediment flux changes over the past decades in the Lower Mekong River: Possible impacts of the Chinese dams. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 10, 181–195 (2006).

Lea, D. M. & Legleiter, C. J. Mapping spatial patterns of stream power and channel change along a gravel-bed river in northern Yellowstone. Geomorphology 252(SI), 66–79 (2016).

Mclntyre, N., Warner, N. H., Gupta, S., Kim, J. R. & Muller, J. P. Hydraulic modeling of a distributary channel of Athabasca Valles, Mars, using a high-resolution digital terrain model. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 117, E03009. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JE003939 (2012).

Abderrezzak, K. E. K. & Paquier, A. One-dimensional numerical modeling of sediment transport and bed deformation in open channels. Water Resour. Res. 45(5). https://doi.org/10.1029/2008WR007134 (2009).

Duan, J.G., Engel, F.L. & Cadogan, A. Numerical simulation of sediment transport in unsteady open channel flow. Water 15(14). https://doi.org/10.3390/w15142576 (2023).

He, L., Duan, J., Wang, G. Q. & Fu, X. D. Case study: Numerical simulation of unsteady hyperconcentrated sediment-laden flow in the Lower Yellow River. J. Hydraul. Eng. 138(11), 958–969 (2012).

Rosca, S., Bilasco, S., Petrea, D., Fodorean, I. & Vescan, I. Bankfull discharge and stream power influence on the Niraj river morphology. Carpath. J. Earth and Environ. Sci. 10(1), 133–146 (2015).

Omar, P. J., Rai, S. P. & Tiwari, H. Study of morphological changes and socio-economic impact assessment: a case study of Koshi River. Arab. J. Geosci. 15, 1426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-022-10723-0 (2022).

Walling, D. E. The changing sediment load of the Mekong River. Ambio 37(3), 150–157 (2008).

Wang, J. J., Lu, X. X. & Kummu, M. Sediment load estimates and variations in the Lower Mekong River. River Res Appl. 27(1), 33–46 (2011).

Liu, C., He, Y., Walling, D. E. & Wang, J. J. Changes in the sediment load of the Lancang-Mekong River over the period 1965–2003. Sci. China 56, 843–852 (2013).

Kummu, M., Lu, X. X., Rasphone, A., Sarkkula, J. & Koponen, J. Riverbank changes along the Mekong River: Remote sensing detection in the Vientiane-Nong Khai area. Quat. Int. 186, 100–112 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA20060402), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51979264, U2243226), and the Key Collaborative Research Program of the Alliance of International Science Organizations (Grant No. ANSO-CR-KP-2021-09). The discharge and water level data were from the Mekong River Commission and Mekong River Commission website (https://portal.mrcmekong.org/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Li He: Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Qiuhong Tang: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing. Dong Chen: Writing—review & editing. Paul P.J. Gaffney: Writing—review & editing. Gaohu Sun: Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, L., Tang, Q., Chen, D. et al. Contribution of channel geometry adjustments to stage variance based on rating-curves in the main stream of the Lancang–Mekong river. Sci Rep 15, 35988 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19822-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19822-w