Abstract

Flooding caused by Hurricane María promoted fungal growth in homes across Puerto Rico, raising concerns about indoor air quality and health risks. This study focuses on identifying Aspergillus species from water-impacted homes in San Juan using culture-based and molecular methods. Aspergillus is a common indoor contaminant in moisture-damaged environments, with some species associated with significant health risks. However, species-level identification is often limited. To address this, we collected samples from 14 homes, identifying 28 Aspergillus isolates through morphological examination and gene sequencing of ITS2, beta-tubulin (benA), and calmodulin (CaM) genes. Species-level identifications of 22 isolates revealed species belonging to the subgenera Aspergillus, Nidulantes, and Circumdanti. We highlighted the CaM gene’s importance in molecular identification by phylogenetic analyses, which showed superior resolution in species differentiation. Culture-based methods also played a crucial role in differentiating closely related species, such as A. flavus and A. oryzae, which molecular methods alone could not reliably separate. Our findings underscore the challenges of Aspergillus identification in post-hurricane, water-impacted indoor environments and emphasize the value of integrating phenotypic and genotypic techniques for accurate species identification. These results contribute to a better understanding of fungal composition and its potential public health implications in disaster-affected settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hurricane María, which struck Puerto Rico in September 2017, caused widespread devastation, including severe flooding that damaged homes across the island. The floods created the ideal conditions for indoor fungal growth, prompting air quality concerns and potential respiratory health repercussions for the residents. Our previous research confirmed a significant increase in fungal proliferation inside flooded homes in San Juan, with Aspergillus species being the most predominant1. This finding aligned with existing literature, which identifies Aspergillus species as common fungi in water-damaged environments2,3,4,5.

Aspergillus is a large genus of filamentous fungi within the Ascomycota division, comprising around 350 species6,7. The genus is subdivided into six subgenera, 27 sections, and about 75 series, holding significance as both a pathogen and a source of pharmaceuticals, as well as in agriculture and food production8,9. Given its medical and economic importance, accurate identification of Aspergillus species is essential, as different species vary in pathogenicity and ability to produce harmful mycotoxins. Species-level identification is especially crucial in environments affected by flooding, where Aspergillus can pose serious health risks ranging from allergic reactions to severe respiratory infections, depending on the species and the vulnerability of exposed individuals9,10,11,12.

Traditionally, Aspergillus classification has relied on macro- and micromorphological features, such as colony diameter, spore color, and microscopic structures like conidial head arrangement and vesicle size13. However, identifying closely related species remains challenging and requires specialized training in fungal taxonomy and microscopy14. Since the early 2000s, molecular techniques have increasingly complemented morphological approaches, with DNA sequencing becoming a standard tool for species identification6. The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region is the official DNA barcode for fungi. However, secondary markers like calmodulin (CaM) and beta-tubulin (benA) are often necessary for distinguishing closely related Aspergillus species6,15. These molecular markers offer greater precision in species differentiation, with amplified sequences typically compared against databases like GenBank6.

Despite the well-documented role of Aspergillus in moisture-damaged indoor environments, research on species-level identification in post-flood conditions remains limited5,16,17. Following extreme weather events such as hurricanes, there is a critical need for studies integrating phenotypic and genotypic techniques to accurately identify Aspergillus species in water-impacted homes. This work addresses that gap by using culture-based and molecular methods to characterize Aspergillus composition in post-Hurricane María homes in San Juan, Puerto Rico. By combining traditional morphological and molecular approaches, it offers a more comprehensive view of fungal presence and species composition in settings susceptible to flooding. This study enhances our understanding of Aspergillus species in water-impacted environments and demonstrates the value of integrating both phenotypic and genotypic methods to improve species identification accuracy. Accurate identification is essential for assessing health risks and informing public health interventions to mitigate fungal contamination in flood-affected areas.

Results

Morphological characteristics of Aspergillus isolates

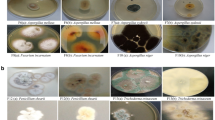

We selected 28 Aspergillus isolates from the sampled homes and two positive controls (A. fumigatus isolate and A. brasiliensis genomic DNA) to achieve species-level identification. The isolates were obtained from 13 different homes (classified as water-impacted, including both flooded and rain-infiltrated homes), with most samples collected approximately one year after the hurricane. Isolates were taken from various locations within the homes (seven from living rooms, seven from kitchens, six from bedrooms, six from bathrooms, and two from outdoor areas). Six isolates originated from sites with > 1000 CFU/m3 total Aspergillus spp., and eighteen from sites where Aspergillus spp. accounted for > 50% of total filamentous fungi (Supplementary Table S1). To provide a culture-based identification to the species level of the Aspergillus isolates selected, we collected a comprehensive description of macro and micromorphological characteristics applicable to the identification of common Aspergillus species (Tables 1 and 2). Colony growth rates on various standardized media and microscopical characteristics are taxonomically informative (Fig. 1). Through the culture-based approach and using three different identification keys (Klich, Klich & Pitt, Samson), we were able to identify 22 out of 28 of our Aspergillus isolates and the positive control (A. fumigatus) (Table 2). The identified isolates belong to different subgenera (Aspergillus, Circumdanti, and Nidulantes). Isolates A50, A77, A111, A143, A159, A293 and A299 remained unidentified.

DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of Aspergillus isolates obtained

To begin the molecular identification approach, we successfully extracted the genomic DNA of all 28 Aspergillus isolates and positive control (A. fumigatus). The genomic DNA concentration from our samples ranged from 11 to 120 ng/µL; 50 µL of the product was used for PCR amplification experiments. To achieve fungal identification to the species level of Aspergillus isolates, we amplified the internal transcribed spacer region 2 (ITS2), beta-tubulin (benA), and calmodulin (CaM) target genes via PCR. Twenty-two out of twenty-eight Aspergillus isolates were positive to PCR amplification of ITS2, benA, and caM genes with amplicon sizes ranging between 300–400 base pairs (bps), 400–5660 bps, and 400–580 bps, respectively. Annealing temperature troubleshooting results for Aspergillus isolates A27, A73, A273, A276, A277, and A299 were unsuccessful.

Gene sequence homology of Aspergillus isolates

We employed Basic Logical Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) results from the ITS2, benA, and CaM gene sequences of this study on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) to assess their sequence similarity with reference sequences in GenBank. The results in Table 3 revealed that most isolates had an identity above 99% similar to reference sequences in GenBank.

Comparison between culture and molecular-based methods for Aspergillus isolates identification

Results from culture-based and molecular-based approaches matched for eleven (11) out of the twenty-eight (28) Aspergillus isolates compared (isolates A19, A33, A75, A137, A139, A150, A155, A215, A226, and A229) and the positive control (A. fumigatus). The culture-based approach provided preliminary species identification to isolates A27, A73, A273, A276, and A277, which couldn’t be identified through molecular-based approaches (no PCR products were obtained). More importantly, macro and micromorphological characteristics were very useful in distinguishing the closely related species A. flavus and A. oryzae (isolates A155 and A372), where ITS2, benA, and CaM genes showed > 100% similarity to both A. flavus and A. oryzae. Although culture-based techniques yielded incorrect species identification to five isolates (A20, A173, A232, 321, and 323), the species identified were classified under the same subgenera and/or section (Supplementary Table S2). For example, isolate A20 (A. steynii) was incorrectly classified as A. westerdijkiae through culture techniques, but both species belong to the Circumdanti subgenera. The same is observed for isolate A323 (A. brunneoviolaceus), identified as A. japonicus through the culture approach, but both species are members of the Nigri section. Isolates A173 (A. gracilis) and A232 (A. hordei) are both incorrectly classified as A. penicillioides through culture-based techniques, but they all belong to the Restricti section. In terms of isolate A321 (A. pseudoglaucus), which was incorrectly identified through macromorphological characterization as A. rubrum (formerly Eurotium rubrum), a note was highlighted in the identification key stating the close resemblance of this species to Eurotium repens, now known as A. pseudoglaucus.

Phylogenetic analysis of Aspergillus isolates

We inferred the evolutionary history of the Aspergillus species isolated from the sampled homes using the Maximum Likelihood method and the Tamura-Nei model in MEGA1218. To measure the consistency of the phylogenetic tree, we employed a bootstrap of 1000 replications. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered is shown next to the branches. Sequences generated in this study are marked with a red diamond in the phylogenetic tree, while reference sequences obtained from GenBank are unmarked. Hamigera avellanea (Aspergillaceae) was used as the outgroup in all trees. The phylogenetic analysis of Aspergillus isolates showed that they grouped into distinct clusters, indicating close genetic relationships.

The phylogenetic tree based on the ITS2 gene revealed that the alignment matrix contained 70 sequences, comprising 28 isolates from this study and 42 representative sequences from GenBank (Supplementary Table S3). After applying a 95% site coverage threshold to exclude positions with gaps or missing data in more than 5% of sequences, the final dataset consisted of 242 nucleotide positions. Isolates from Aspergillus species classified under the same taxonomical section had above 83% bootstrap support, with several species-level clusters reaching 99% (e.g., A. versicolor, A. sydowii, A. westerdijkiae) (Fig. 2).

The beta-tubulin (benA) gene alignment matrix contained 69 sequences (28 isolates from this study and 41 reference sequences from GenBank). To reduce the influence of poorly aligned regions, the partial deletion option was applied, excluding positions with less than 95% site coverage, resulting in a final dataset of 277 positions. All isolates showed > 83% bootstrap-supported clustering with known reference species from GenBank (Fig. 3). High-confidence clusters were observed for species such as A. versicolor, A. sydowii, and the closely related pair A. flocculosus / A. ochraceopetaliformis, each receiving 99–100% support. In contrast, some members of the Nigri section showed weaker support, ranging from 57–70%.

The phylogenetic tree based on the CaM gene had an alignment matrix that also included 70 sequences (28 isolates from this study and 42 reference sequences from GenBank). The partial deletion option was applied to eliminate positions with less than 95% site coverage, resulting in a final alignment of 366 positions. All isolates, except for A. petersonii, showed over 80% cluster similarities with representative sequences from GenBank (Fig. 4). Different but closely related species like A. flocculosus/A. ochraceopetaliformis (series Steynorium) and A. flavus/A. oryzae (series Flavi) were still clustered together in their respective clades.

Discussion

In this study, we applied both phenotypic and genotypic methods to achieve species-level identification of 28 Aspergillus isolates from homes affected by Hurricane María in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Using molecular techniques, we identified 22 isolates at the species level, categorizing them into the subgenera Circumdanti (n = 12), Aspergillus (n = 8), and Nidulantes (n = 3). The Circumdanti and Nidulantes subgenera, each encompassing over 100 species, represent some of the most diverse Aspergillus species19,20. Meanwhile, the Aspergillus subgenus, characterized by xerophilic species, thrives in low-moisture environments, making it prevalent indoors21,22. Beyond identification, documenting the variety of Aspergillus species in post-hurricane homes provides a regional baseline for Puerto Rico that can support environmental health surveillance and future longitudinal analyses to track fungal populations over time. This information is particularly important in the Caribbean, where post-disaster mycological studies are scarce and the warm/humid climate supports the growth of fungi. Moreover, because different Aspergillus species may have varying levels of pathogenic potential23, species-level identification can help assess public health risks and better prepare for future hurricane events.

Our phylogenetic analysis of ITS2, benA, and CaM sequences showed distinct clustering patterns. ITS2-based trees showed strong bootstrap support (≥ 83%) for most section-level groupings, with species like A. versicolor, A. sydowii, and A. westerdijkiae forming distinct clades supported at 99–100%. The benA gene tree also produced high-confidence clusters, particularly for A. versicolor, A. sydowii, and the pair A. flocculosus / A. ochraceopetaliformis, though bootstrap support was lower (57–70%) for some Nigri section members. The CaM gene tree resolved most isolates at the species level, except for A. petersonii, with species-level clusters for A. flavus, A. oryzae, and A. westerdijkiae supported at 98–100%. These results reinforce the CaM gene’s superior discriminatory power compared to ITS2 and benA, consistent with previous studies24,25.

However, six isolates, likely belonging to the black Aspergilli in the Nigri section, could not be identified at the species level due to the limitations of both molecular and phenotypic methods26,27. While sequence-based identification is the gold standard, morphological traits remain essential for resolving closely related species. For example, in this study, differentiating A. flavus from A. oryzae required morphological analysis, as molecular results alone were inconclusive28. Additionally, morphology-based methods allowed for preliminary identification of five black Aspergilli isolates that molecular methods could not identify, underscoring the complementary role of culture techniques in complex identifications29. Despite identifying 22 isolates through morphological keys, five showed discrepancies with molecular results but remained in the same subgenus or section, highlighting limitations of morphological identification for certain taxonomic groups30. Expanding morphological keys is critical for identifying emerging Aspergillus species in indoor air environments.

Most isolates identified in this study, such as A. flavus (A155), A. niger (A33), A. penicillioides (A137), A. sydowii (A139), A. tamarii (A229), A. versicolor (A19, A150), and A. westerdijkiae (A215), have previously been reported as common indoor fungal contaminants19,31. Specifically, A. versicolor, A. sydowii, and A. penicillioides, all from xerophilic or primary colonizer sections, are often associated with building dust and are well adapted to indoor environments21,22. In Puerto Rico, these species have been detected at high concentrations in indoor fungal population studies32,33. Taxonomic classification of our isolates revealed representation across sections, including Circumdanti, Nigri, Petersoniorum, Candidi, and Flavi. For example, isolates from section Circumdanti, such as A. steynii (A20) and A. westerdijkiae (A215), are known producers of the mycotoxin ochratoxin A34. Members of the Nigri section, such as A. niger and A. brunneoviolaceus, are also prevalent indoor contaminants35,36. Finally, Flavi section members like A. flavus and A. oryzae highlight the health implications of mycotoxigenic Aspergillus species in indoor air37. While many of these species are recognized as typical indoor fungi, their frequent recovery in this study suggests they may become more dominant or persistent in post-flood indoor environments, particularly under the warm and humid conditions typical of Puerto Rico. Though Aspergillus species have been broadly reported after hurricanes1,2,5,38,39, this study provides one of the few species-level analyses of indoor Aspergillus communities in a post-hurricane setting4,17,40. Our findings highlight A. versicolor, A. flavus, A. niger, A. westerdijkiae, and A. sydowii as prevalent species in water-impacted homes, warranting further study into their environmental persistence and potential health risks.

The species we detected are consistent with organisms that proliferate in house dust and can contribute to adverse respiratory outcomes31,41. Moisture intrusion and damaged building materials sustain colonization and elevate airborne spores, which are linked to upper- and lower-airway symptoms and asthma exacerbations42,43,44. Beyond air, Aspergillus can persist in plumbing biofilms and building water systems and be released into the air during activities like showering, providing an indoor exposure route that is especially relevant after flooding45,46. Several of the species we recovered (e.g., A. versicolor, A. flavus, A. niger, A. westerdijkiae, A. sydowii) are common in indoor dust41; some are also toxigenic (e.g., A. versicolor → sterigmatocystin; A. westerdijkiae → ochratoxin A, indole alkaloids), underscoring potential combined allergenic, infectious, proinflammatory and toxic exposures in water-impacted homes47,48. Although A. fumigatus was not isolated in our set (included only as a control), sensitization to A. fumigatus is a recognized severe-asthma phenotype associated with worse airflow obstruction, higher treatment requirements, and structural airway disease, reinforcing the broader clinical importance of Aspergillus exposures in post-disaster settings49. Hot, humid conditions such as those in the Caribbean favor indoor fungal growth. Across studies from varied geographies, indoor Aspergillus exposure is associated with allergic rhinitis and asthma symptoms/exacerbations50,51; among susceptible hosts, it is linked to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA)23, and invasive aspergillosis remains a risk for immunocompromised individuals44,52. Non-pulmonary diseases relevant to the region include otomycosis (frequently due to A. niger and related species) and fungal keratitis (often involving A. flavus in tropical climates)53,54; cutaneous/wound aspergillosis can occur where the skin barrier is disrupted after disasters55. Complementing these exposure–response patterns, recent work in Puerto Rican infants born after Hurricane María showed nasal mycobiome dysbiosis within the first year post-hurricane, indicating the potential of disaster-related fungal exposures to shape early-life airways56.

The growth of indoor Aspergillus spp. and other filamentous fungi is best controlled by eliminating and removing moisture sources. Key measures include: (i) fixing leaks and venting moisture-generating appliances to the outdoors57,58,59; (ii) drying all wet materials within 24–48 hours58,59; (iii) discarding porous items that remained wet (e.g., gypsum board, carpets, furniture)58,59; (iv) cleaning hard, non-porous surfaces with detergent and using a High-Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA)-vacuum after drying58; and (v) keeping the indoor relative humidity below ~ 60% (ideally 30–50%) via dehumidification and improved ventilation59. Given the clinical relevance of Aspergillus in asthma and allergy, remediation should also protect occupants and workers with at least an N95 respirator, eye protection, and gloves during debris removal and cleaning58. Additionally, the use of portable HEPA filter air purifiers in occupied rooms helps to reduce airborne spore levels in the air59,60. Consistent with our prior work in naturally ventilated Puerto Rican homes, outdoor fungal levels significantly influenced indoor levels, highlighting an outdoor–indoor air continuum after disasters1. Control must therefore extend beyond the building envelope: prompt removal of organic debris (fallen branches, wood piles, water-damaged materials) from yards, sidewalks, and immediate surroundings, along with community-scale debris pickup, can reduce neighborhood reservoirs of filamentous fungi that otherwise re-enter homes through open windows and doors.

This study has several strengths, notably the combined use of phenotypic and genotypic techniques for Aspergillus identification. The integration of morphological methods with molecular analysis using ITS2, ß-tubulin (benA), and especially the calmodulin (CaM) gene, which provided superior resolution for species differentiation, allowed for more accurate species-level identification and phylogenetic analysis of Aspergillus isolates. Morphological characterization using culture techniques also played a key role in distinguishing closely related species like A. flavus and A. oryzae, which were difficult to tell apart using molecular methods alone28. This combined strategy is especially important in post-flood indoor settings, where precise identification can help guide effective public health responses.

However, there are limitations to consider. Molecular techniques, while powerful, did not fully resolve all isolates, especially black Aspergilli in the Nigri section, where species-specific differentiation remains challenging27,61. Additionally, the final datasets used in our Maximum Likelihood trees were reduced through partial deletion (to 95% site coverage), resulting in 242, 277, and 366 nucleotide positions for ITS2, benA, and CaM, respectively. While these are generally acceptable for fungal phylogenetics, the limited variability in some regions may contribute to lower support values in specific branches. The study’s sample size was limited to 28 isolates from a specific geographic area (San Juan, Puerto Rico), potentially limiting the generalizability of findings to broader environments affected by flooding, such as those that are not hot and humid. Additionally, exclusively relying on morphological keys can lead to unsuccessful identifications, especially when dealing with newly described Aspergillus species. The need to revise these keys is indicated as more species are being discovered. We also acknowledge that we did not quantify species-specific airborne concentrations (CFU/m3) for each Aspergillus isolate. Air sampling produced CFU/m3 at the genus level during culture, whereas species identification was performed later on representative isolates; because several taxa are phenotypically indistinguishable by routine macro-/micromorphology, colony counts cannot be retrospectively attributed to species. To provide quantitative context, we included per-site total Aspergillus spp. CFU/m3 and the proportion of Aspergillus within total filamentous fungi for the room/areas from which these isolates were recovered (Supplementary Table S1). These are genus-level values for context and should not be interpreted as species-specific concentrations. Future post-disaster studies requiring species-resolved exposure estimates should pair air sampling with parallel molecular quantification at the time of collection (e.g., targeted qPCR). Finally, we did not perform antifungal susceptibility testing; future work should evaluate resistance patterns of environmental Aspergillus isolates in the Caribbean, given growing global concern about azole resistance62.

In conclusion, this study provides essential insights into the variety of Aspergillus species in water-impacted homes in a hot and humid environment. It stresses the need for a combination of molecular and morphological techniques for robust fungal identification. Our results on species like A. versicolor, A. flavus, and A. sydowii point to serious implications for indoor air quality and public health in the disaster zone, in favor of extensive identification strategies to inform effective health measures.

Methods

Characterization of Aspergillus isolates

Collection of Aspergillus isolates. Approximately 400 Aspergillus isolates were cryopreserved in 2.0 mL tubes containing 1 mL of culture media (MEA or G25N) and stored at -80 °C until further use. To lower the quantity of Aspergillus isolates to study, we selected Aspergillus isolates from sampled homes that —after aggregating across all sampled rooms/areas within the home—met a priori screening criteria of > 1000 CFU/m3 total Aspergillus spp. or > 50% Aspergillus spp. of total filamentous fungi. These thresholds were used to account for higher-burden homes and are not health-based exposure limits, as major guidelines do not endorse quantitative cutoff values for indoor mold contamination57. Supplementary Table S1 reports the per-site (room/area) Aspergillus spp. concentration (CFU/m3) and percentage for the specific location from which each isolate was recovered, home-level aggregates were used only for selection. Approximately 210 Aspergillus isolates recovered from the sampled homes met these criteria. We randomly selected 28 Aspergillus isolates from this list for further testing to balance feasibility and resource constraints, ensuring a manageable sample size for in-depth species identification. These Aspergillus isolates were grown on G25N media for up to 14 days at 25 ± 2 °C to generate sufficient growth to identify them at the species level and to perform experiments evaluating their pro-inflammatory potential.

Macromorphological characterization of Aspergillus isolates

To identify the selected 28 Aspergillus isolates to species level through culture techniques, we followed Maren A. Klich’s morphologically based system14. Colonies were grown on four media to describe the fungal isolates macromorphologically. The media used were the following: Czapek Yeast Agar (CYA, K2HPO4 0.5 g, Czapek concentrate 5.0 mL, yeast extract 2.5 g, sucrose 30.0 g, agar 7.5 g, distilled water 500 mL), Czapek Yeast Agar with 20% sucrose (CY20S, K2HPO4 0.5 g, Czapek concentrate 5.0 ml, yeast extract 2.5 g, sucrose 100.0 g, agar 7.5 g, distilled water 500 mL) and commercial Malt Extract Agar (MEA, Hardy Diagnostics). Twenty-five mL of sterilized media were poured into standard (100 mm) Petri dishes. Four plates were used for each culture: two of CYA and one of CY20S and MEA. To prevent stray colonies on the plates, we prepared spore suspensions using a medium consisting of 0.2% agar and 0.05 Tween 80. Briefly, we pipetted 1 mL aliquots of the sterilized medium into small 2.5 mL cryovials. We mixed conidia from 7 to 14-day-old growth into the medium. Then, we placed 2 µL aliquots at three equidistant points from the center of the plate. We incubated each plate for seven days, with one CYA plate at 37 °C and the remaining at 25 °C. Incubation at 25 °C represents a typical indoor room temperature, whether incubation at 37 °C is done to simulate human body temperature. After the 7-day incubation, we collected data on conidial color, colony diameter, mycelial color, exudate presence, reverse color, soluble pigment, sclerotia, and cleistothecia.

Micromorphological characterization of Aspergillus isolates

We used the microculture technique to describe the micromorphological features of the selected Aspergillus isolates. Briefly, we inoculated two parallel lines of the Aspergillus conidia from a 7 to 14-day-old colony in a 60 mm Petri Dish with G25N media using an inoculating needle. Then, we inserted a sterile coverslip at a 45-degree angle in each inoculated line. We incubated the microcultures at 25 ± 2 °C for 7 days. After incubating, we gently collected the coverslips using stained (with lactophenol cotton blue) and unstained slide preparations. We used the NIKON 80i microscope to observe and collect micromorphology features such as seriation type (predominantly uniseriate or biseriate), vesicle shape, conidia characteristics (shape, size, and surface texture), stipe (length, color, and surface texture) and ascospores (color, size, ornamentation, and surface texture).

Molecular identification of Aspergillus isolates

We extracted fungal genomic DNA using the standard protocol of Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (QIAGEN LLC, Germantown Road, Maryland, USA). For sample preparation, we grew each fungal isolate on G25N and incubated them at 25 ± 2 °C for 7 to 14 days. Then, we transferred fungal growth from the surface of the plate using a sterile swab or a sterile scalpel blade to the bead tube of the DNAeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit and followed the manufacturer’s instructions. We quantified the genomic DNA using the Qubit® dsDNA HS (High Sensitivity) Assay at room temperature (Waltham, Massachusetts, US) and stored at − 20 °C until genomic DNA amplification and sequencing.

PCR amplification of target genes

For PCR amplification, we used primers specific for Internal Transcribed Spacer Region 2 (ITS2), beta-tubulin gene (benA), and calmodulin gene (CaM) (Table 4). We performed PCR amplification of the extracted DNA in a 100 µL reaction mixture as follows: 5 µL gDNA template, 50 µL Qiagen HotStarTaq Master Mix (QIAGEN LLC, Germantown Road, Maryland, USA), 5 µL of each forward and reverse primers, and 35 µL RNase free water. We included a non-template negative and a positive control (genomic DNA from Aspergillus brasiliensis, ATCC 16404D-2) in each amplification reaction. We programmed the thermocycler to the following PCR conditions: HotStarTaq DNA Polymerase activation incubation step at 95 °C for 15 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s, annealing at 55 °C for 45 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. After complete amplification, we analyzed the PCR products for gel electrophoresis using 1.5% agarose gel (1.5 g of agarose in 100 ml of TAE 1 × buffer) with ethidium bromide as the staining agent.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

We purified the PCR products using the Qiagen QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN LLC, Germantown Road, Maryland, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and sequenced with the primers used for amplification. Sequencing was outsourced using the Big Dye X Terminator Sequencing Kit 3.1 and the ABI 3500 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems) at the Molecular Biology Core Facility from the RCMI Program at the University of Puerto Rico—Medical Sciences Campus. We verified and cleaned the sequences using FinchTV (Geospiza, Inc.) Version 1.5.0 chromatogram viewer software. We assigned species names to the Aspergillus isolates after comparing the contigs (created from forward and reverse complement sequences) with representative sequences available in NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information). For phylogenetic analysis, we aligned sequences for each gene region (ITS2, beta-tubulin [benA], and calmodulin [CaM]) using the ClustalW algorithm with default parameters in MEGA version 1218. Multiple sequence alignments were visually inspected and trimmed using the partial deletion method with a 95% site coverage cutoff to exclude positions with significant gaps or missing data. Evolutionary relationships were inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Tamura-Nei model. The best tree topology was selected based on log-likelihood scores from a heuristic search that compared Neighbor-Joining and Maximum Parsimony starting trees. Robustness of the phylogenetic trees was assessed with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Branches with < 50% support were collapsed. Reference sequences for each gene were downloaded from GenBank and are listed in Supplementary Table S3. Hamigera avellanea (family Aspergillaceae) was used as the outgroup in all phylogenetic trees.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings, including datasets generated and analyzed during the research, are available upon request. Due to privacy considerations regarding sample locations and specifics, data access is restricted but can be granted to the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Any shared data will include the minimal dataset necessary to interpret, replicate, and build upon the findings reported in this article.

References

Vélez-Torres, L. N. et al. Hurricane María drives increased indoor proliferation of filamentous fungi in San Juan, Puerto Rico: A two-year culture-based approach. PeerJ 10, 1–24 (2022).

CDC. Health concerns associated with mold in water-damaged homes after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita—New Orleans area, Louisiana, October 2005. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2, 41–44 (2006).

Barbeau, D. N., Grimsley, L. F., White, L. E., El-Dahr, J. M. & Lichtveld, M. Mold exposure and health effects following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Annu. Rev. Public Health 31, 165–178 (2010).

Chew, G. L. et al. Mold and endotoxin levels in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: A pilot project of homes in New Orleans Undergoing Renovation. Environ. Health Perspect. 114, 1883–1889 (2006).

Solomon, G. M., Hjelmroos-Koski, M., Rotkin-Ellman, M. & Hammond, S. K. Airborne mold and endotoxin concentrations in New Orleans, Louisiana, after flooding, October through November 2005. Environ. Health Perspect. 114, 1381–1386 (2006).

Samson, R. A. et al. Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 78, 141–173 (2014).

Tsang, C.-C., Tang, J. Y. M., Lau, S. K. P. & Woo, P. C. Y. Taxonomy and evolution of Aspergillus, Penicillium and Talaromyces in the omics era—Past, present and future. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 16, 197–210 (2018).

Houbraken, J. et al. Classification of Aspergillus, Penicillium, Talaromyces and related genera (Eurotiales): An overview of families, genera, subgenera, sections, series and species. Stud. Mycol. 95, 5–169 (2020).

Kendrick, B. Fungi: Ecological importance and impact on humans. eLS. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470015902.a0000369.pub2 (2011).

Balloy, V. & Chignard, M. The innate immune response to Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbes Infect. 11, 919–927 (2009).

Seyedmousavi, S., Lionakis, M. S., Parta, M., Peterson, S. W. & Kwon-Chung, K. J. Emerging Aspergillus species almost exclusively associated with primary immunodeficiencies. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 5, 213 (2018).

Rudramurthy, S. M., Paul, R. A., Chakrabarti, A., Mouton, J. W. & Meis, J. F. Invasive Aspergillosis by Aspergillus flavus: Epidemiology, diagnosis, antifungal resistance, and management. J. Fungi 5, 55 (2019).

Klich, M. A. Identification of Common Aspergillus Species. (Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, 2002).

Klich, M. A. Identification of clinically relevant aspergilli. Med. Mycol. 44, 127–131 (2006).

Schoch, C. L. et al. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 6241–6246 (2012).

Jakšić, D. et al. Fungi and their secondary metabolites in water-damaged indoors after a major flood event in eastern Croatia. Indoor Air 31, 730–744 (2021).

Rao, C. Y. et al. Characterization of airborne molds, endotoxins, and glucans in homes in New Orleans after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita▿. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 1630–1634 (2007).

Kumar, S. et al. MEGA12: Molecular evolutionary genetic analysis version 12 for adaptive and green computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 41, 1–9 (2024).

Chen, A. J. et al. Aspergillus section Nidulantes (formerly Emericella): Polyphasic taxonomy, chemistry and biology. Stud. Mycol. 84, 1–118 (2016).

Sun, B. et al. Four new species of Aspergillus Subgenus Nidulantes from China. J. Fungi 8, 1205 (2022).

Sklenář, F. et al. Phylogeny of Xerophilic aspergilli (subgenus Aspergillus) and taxonomic revision of section Restricti. Stud. Mycol. 88, 161–236 (2017).

Visagie, C. M. et al. A survey of xerophilic Aspergillus from indoor environment, including descriptions of two new section Aspergillus species producing eurotium-like sexual states. MycoKeys 19, 1–30 (2017).

Stemler, J. et al. Aspergillus-associated diseases from an infectious diseases and allergological perspective. Allergo J. Int. 33, 140–152 (2024).

Alshehri, B. & Palanisamy, M. Evaluation of molecular identification of Aspergillus species causing fungal keratitis. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 751–756 (2020).

Ashtiani, N. M., Kachuei, R., Yalfani, R., Harchegani, A. B. & Nosratabadi, M. Identification of Aspergillus sections Flavi, Nigri, and Fumigati and their differentiation using specific primers. Le Infez. Med. 25, 127–132 (2017).

Abarca, M. L., Accensi, F., Cano, J. & Cabañes, F. J. Taxonomy and significance of black aspergilli. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 86, 33–49 (2004).

D’hooge, E. et al. Black aspergilli: A remaining challenge in fungal taxonomy? Med. Mycol. 57, 773–780 (2018).

Nargesi, S. et al. Differentiation of Aspergillus flavus from Aspergillus oryzae targeting the cyp51A gene. Pathogens 10, 1279 (2021).

Wickes, B. L. & Wiederhold, N. P. Molecular diagnostics in medical mycology. Nat. Commun. 9, 5135 (2018).

Lass-Flörl, C., Dietl, A.-M., Kontoyiannis, D. P. & Brock, M. Aspergillus terreus species complex. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 34, e00311-e320 (2021).

Mousavi, B. et al. Aspergillus species in indoor environments and their possible occupational and public health hazards. Curr. Med. Mycol. 2, 36–42 (2016).

Bolaños-Rosero, B., Betancourt, D., Dean, T. & Vesper, S. Pilot study of mold populations inside and outside of Puerto Rican residences. Aerobiologia (Bologna). 29, 537–543 (2013).

Vesper, S. et al. Mold populations and dust mite allergen concentrations in house dust samples from across Puerto Rico. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 26, 198–207 (2016).

Visagie, C. M. et al. Ochratoxin production and taxonomy of the yellow aspergilli (Aspergillus section Circumdati). Stud. Mycol. 78, 1–61 (2014).

Jurjević, Ž et al. Two novel species of Aspergillus section Nigri from indoor air. IMA Fungus 3, 159–173 (2012).

Varga, J. et al. Occurrence of black Aspergilli in indoor environments of six countries. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 65, 219–223 (2014).

Flores, M. E. B. et al. Fungal spore concentrations in indoor and outdoor air in university libraries, and their variations in response to changes in meteorological variables. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 24, 320–340 (2013).

Riggs, M. A. et al. Resident cleanup activities, characteristics of flood-damaged homes and airborne microbial concentrations in New Orleans, Louisiana, October 2005. Environ. Res. 106, 401–409 (2008).

Schwab, K. J. et al. Microbial and chemical assessment of regions within New Orleans, LA impacted by Hurricane Katrina. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 2401–2406 (2007).

Bolaños-Rosero, B., Hernández-González, X., Cavallín-Calanche, H. E., Godoy-Vitorino, F. & Vesper, S. Impact of Hurricane Maria on mold levels in the homes of Piñones, Puerto Rico. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 16, 661–668 (2022).

Visagie, C. M. et al. Aspergillus, Penicillium and Talaromyces isolated from house dust samples collected around the world. Stud. Mycol. 78, 63–139 (2014).

Andersen, B., Frisvad, J. C., Søndergaard, I., Rasmussen, I. S. & Larsen, L. S. Associations between fungal species and water-damaged building materials. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 4180–4188 (2011).

Jakšić, D. et al. Post-flood impacts on occurrence and distribution of mycotoxin-producing Aspergilli from the sections Circumdati, Flavi, and Nigri in indoor environment. J. Fungi 6, 282 (2020).

Toda, M. et al. Invasive mold infections following Hurricane Harvey—Houston, Texas. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 10, ofad093 (2023).

Richardson, M. & Rautemaa-Richardson, R. Exposure to Aspergillus in home and healthcare facilities’ water environments: Focus on biofilms. Microorganisms. 7, (2019).

Anaissie, E. J. et al. Pathogenic Aspergillus species recovered from a hospital water system: A 3-year prospective study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34, 780–789 (2002).

Engelhart, S. et al. Occurrence of toxigenic Aspergillus versicolor isolates and sterigmatocystin in carpet dust from damp indoor environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 3886–3890 (2002).

Mikkola, R., Andersson, M. A., Hautaniemi, M. & Salkinoja-Salonen, M. S. Toxic indole alkaloids avrainvillamide and stephacidin B produced by a biocide tolerant indoor mold Aspergillus westerdijkiae. Toxicon 99, 58–67 (2015).

Heena, M., et al. The clinical implications of Aspergillus fumigatus sensitization in difficult-to-treat asthma patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pr. 9, 4254–4267 (2021).

Behbod, B. et al. Asthma and allergy development: contrasting influences of yeasts and other fungal exposures. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 45, 154–163 (2015).

Sharpe, R. A., Bearman, N., Thornton, C. R. & Husk, K. Indoor fungal diversity and asthma: A meta-analysis and systematic review of risk factors. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 135, 110–122 (2013).

Wurster, S., et al. Invasive mould infections in patients from floodwater-damaged areas after hurricane Harvey—a closer look at an immunocompromised cancer patient population. 84, 701–709 (2024).

Bojanović, M. et al. Etiology, predisposing factors, clinical features and diagnostic procedure of Otomycosis: A literature review. J. Fungi 9, (2023).

Ahmadikia, K. et al. Distribution, prevalence, and causative agents of fungal Keratitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis (1990 to 2020). Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 698780 (2021).

Gupta, A. K., Thornbush, M. & Wang, T. Climate change, natural disasters, and cutaneous fungal infections. Int. J. Dermatol. 64, 1349–1355 (2025).

Wang, R. et al. Dysbiosis in the nasal mycobiome of infants born in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. Microorganisms. 13, (2025).

WHO, Regional, Office, for & Europe. WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Dampness and Mould. Moisture Control & Ventilation, vol. 3 (2009).

Brandt, M. et al. Mold Prevention Strategies and Possible Health Effects in the Aftermath of Hurricanes and Major Floods. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5508a1.htm (2006).

EPA. A Brief Guide to Mold, Moisture and Your Home. https://www.epa.gov/mold/brief-guide-mold-moisture-and-your-home.

Cox, J. et al. Effectiveness of a portable air cleaner in removing aerosol particles in homes close to highways. Indoor Air 28, 818–827 (2018).

Samson, R. A. et al. Diagnostic tools to identify black aspergilli. Stud. Mycol. 59, 129–145 (2007).

Verweij, P. E. et al. The one health problem of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: current insights and future research agenda. Fungal Biol. Rev. 34, 202–214 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank all the families participating in this research and Dr. Edna E. Aquino for her invaluable support with the molecular-based experiments. This research project partially fulfilled Lorraine N. Vélez-Torres’s doctoral dissertation at the University of Puerto Rico—Medical Sciences Campus.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) number R21 ES029762-0101, and partial funds were received from MBRS-RISE program of UPR-MSC (award number R25GM061838), PR-INBRE BiRC NIH/NIGMS P20 GM103475, NIMHD CCRHD grant number U54 MD007600, and NIGMS-NIH COBRE Puerto Rico Center for Microbiome Sciences award number 1P20GM156713-01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.N.V.T. contributed substantially to the study’s conception and design, performed the primary experiments, acquired, analyzed, and interpreted data, created tables and figures, and drafted the manuscript. B.B.R. supported acquiring and analyzing the culture-based experimental approach and contributed to manuscript revisions. F.G.V. assisted in the design of molecular experiments and contributed to manuscript revisions. F.E.R.M., J.P.M., K.K., and H.C. contributed to the review and substantive revisions of the manuscript. Each author has approved the submitted version with their contributions. All authors agree to be personally accountable for their contributions and to address any questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the study, ensuring any concerns are investigated and appropriately documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vélez-Torres, L.N., Bolaños-Rosero, B., Godoy-Vitorino, F. et al. Molecular and culture-based identification of Aspergillus species in water-impacted homes following Hurricane María in Puerto Rico. Sci Rep 15, 35922 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19869-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19869-9