Abstract

This study investigates the high-precision numerical simulation technology of passenger cars based on a numerical wind tunnel, develops a virtual numerical wind tunnel model based on the existing vehicle wind tunnel in China, and simulates the flow field characteristics in the actual wind tunnel by choosing the appropriate mesh strategy and boundary conditions. The realizable k-ɛ, shear stress transport (SST) k-ω, and SST detached eddy simulation turbulence models are used to simulate numerically the aerodynamic drag and lift of the real vehicle. These simulated values are compared with the actual wind tunnel test values. Results show that the numerical wind tunnel can successfully simulate the flow field characteristics in the wind tunnel, such as turbulence degree, airflow deflection angle, pressure gradient, and boundary layer displacement thickness. Moreover, the simulation accuracy of the numerical wind tunnel is higher than that of the traditional rectangular open-domain simulation. This study confirms the capability of the numerical wind tunnel in simulating the flow field characteristics in wind tunnels, thereby improving the numerical simulation accuracy and providing a new perspective for the numerical simulation study of automotive aerodynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is a comprehensive discipline combining computational science and fluid mechanics. CFD, wind tunnel test, and theoretical analysis constitute the three major research tools of fluid mechanics. Compared with the wind tunnel test, CFD is low-cost, time-saving, and not limited by wind tunnel conditions; compared with theoretical analysis, CFD can deal with complex problems without simplifying the flow problems.

In the current numerical simulation, the numerical model of the real vehicle is placed into a simple rectangular open domain for meshing and boundary condition setting. After the calculation converges, the aerodynamic data of the whole model are obtained and then analysed. The accuracy of the simulation results must be verified by comparing them with the aerodynamic data obtained from the wind tunnel test to verify the accuracy of the CFD simulation results. Discrepancies between tests and simulations can usually be attributed to the fitness of the turbulence model or the setting of the boundary conditions in the test domain. Existing studies usually revolve around the inadequacy of the numerical model. Yi C took the CAERI Aero Model as the research object and proposed the automated calculation process based on the grid adaptive encryption method by improving the grid scheme1. The results are as follows: The simulation accuracy of the method is high, and the number of volume meshes of the whole vehicle can be reduced by approximately 13%; and the computation time efficiency can be improved by approximately 9.6%. Irigaray explored the application of adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) in automotive aerodynamic design2. Based on different hydrodynamic criteria for the DrivAer model, a comparison of the results obtained using AMR showed that the use of AMR improves the computational resources by optimizing the mesh height in the desired region.Xiaojing W proposed a vehicle shape optimization design method based on a multi-fidelity deep neural network to reduce the number of high-precision data required in the optimization design3. The method can fully integrate the information contained in the data with different accuracies, accelerate the process of aerodynamic shape optimization by applying the developed optimization method to the drag reduction optimization of the fastback MIRA standard model. Numerical simulation solution methods continue to evolve and become feasible as computational power increases.

Regarding the test domain and boundary conditions, a common approach to CFD simulation of vehicle aerodynamics involves the of use open-road conditions. The numerical test area is a large rectangular rectangle with uniform inlet flow, a perfectly moving ground plane, and a negligible obstruction ratio, i.e., the open domain. However, the open domain is not exactly similar to the test section of a wind tunnel, the wind tunnel inlet flow is not completely uniform, and the motion of the ground with respect to the vehicle has to be simulated using a different technique, which usually covers only the area underneath and directly in front of the vehicle. A common approach to the discrepancies caused by wind tunnel disturbances involves correcting the physical measurements using a correction method based on the theory of inviscid flow. Rijns evaluated the simulation performance of four RANS turbulence models4, which are related to experimental and high-fidelity delayed detached eddy simulation (DES) data, for the aerodynamic evaluation of a high-performance variant of the DrivAer model. A new CFD-based clogging correction method is presented and applied to evaluate the accuracy of conventional clogging correction methods. Xin S constructed a numerical wind tunnel model based on the structural parameters of the real vehicle wind tunnel5. They also conducted a comparative analysis of the numerical wind tunnel simulation of 12 vehicle forms and the OR simulation with the open-source model DrivAer. They found that the numerical wind tunnel can effectively simulate the flow field characteristics in the wind tunnel, such as shear layer and nozzle obstruction effect. Huang conducted digital wind tunnel (DWT) simulations and OR simulations6. They verified them with experimental results and concluded that DWT simulations with the same geometry as the real wind tunnel perform better than OR simulations. The maximum difference between the experimental results and the DWT simulation results is not more than 2%. Josefsson performed numerical simulations of the DrivAer model by using different tires and rims to simulate the flow field characteristics in the open computational domain versus the wind tunnel model7. The comparison of the simulated force and flow field results with experimental data revealed that the inclusion of a wind tunnel in the calculations improves the prediction of the flow field. Fu simulated the flow field of the MIRA model in the rectangular computational domain and the virtual wind tunnel computational domain8. The numerical wind tunnel predicts the flow field at the rear of the car body, and the results are highly consistent with the experimental results. Qiang F conducted numerical simulation calculations in the numerical wind tunnel computational domain and the traditional rectangular computational domain using the real vehicle model9. Moreover, the numerical simulation results are compared and analyzed with the wind tunnel measured results in terms of velocity distribution, wind tunnel pressure, equilibrium port flow field, buffer port flow field, other representative flows and pressures, and other characteristic physical quantities. Xiaochong W compared the differences between the traditional rectangular computational domain and the Tongji University whole-vehicle aerodynamic wind tunnel computational domain in the numerical simulation of automobile aerodynamics based on the DrivAer model10. The results showed that the wind tunnel computational domain can be used as an effective tool to study the differences in results between wind tunnels. Xu established a high-precision digital automotive climatic wind tunnel based on an actual climatic wind tunnel.Numerical wind tunnel improved on the inherent shortcomings of the open domain11, such as neglecting wind tunnel wall effects, incomplete moving ground simulations, and inhomogeneity of inlet flow.

The open domain structure is very different from the structure of the actual wind tunnel; thus, some differences occur when the results of the open domain numerical simulation are compared with the wind tunnel test results. In recent years, numerical wind tunnels have received extensive attention in the field of numerical simulation technology for automotive aerodynamics. Stoll experimentally and numerically investigated the unsteady aerodynamic properties of a 25% scale DrivAer slant-back model12, and the effect of the wind tunnel environment on the nonconstant aerodynamic forces and the moments generated under crosswind excitation were determined. Fu simulated the flow field of the MIRA model in the virtual wind tunnel computational domain9.Existing validation focuses on simplified models and generalizability to complex real-vehicle geometries is unvalidated.Sebald investigated the constant and nonconstant flow in full-size automobile open-ended wind tunnels with and without a car, and two approaches to solving the problem of insufficient turbulent kinetic energy were proposed13. Ljungskog conducted a numerical simulation of a car under different operating conditions using a complete model of the test section of a slotted-wall wind tunnel14. The results showed that the absolute drag coefficient can be predicted very accurately by simulating a car in a wind tunnel. Fu tested a detailed full-scale model of the Hyundai Veloster using a CFD-based virtual wind tunnel15. They found that the simulation results of the flow field at the rear of the vehicle in the computational domain of the numerical wind tunnel agree well with the experimental results. Xu X established a CFD numerical model of the environmental wind tunnel and investigated the distribution of the flow field in the environmental wind tunnel16,17. The results provided a reference for the development of the digitalized automotive environmental wind tunnel and its engineering application in 2022.There are imperfections in these studies, such as the questionable reliability of the traditional obstruction correction method in strongly separated flow fields, the unclear mechanism of the effect of wind tunnel wall disturbances on nonconstant aerodynamic forces, and the lack of evaluation of flow field indices in empty wind tunnels. In 2018, China launched the National Numerical Wind Tunnel (NNW) project18,19,20,21,22,23,24. The NNW project consists of five subsystems: basic science problem research, integrated framework and generalized CFD software, multidisciplinary coupling software, verification and validation, and high-performance computers. However, it mainly addresses aerospace issues.

Based on Tongji University’s whole-vehicle aerodynamic wind tunnel, this study develops a virtual numerical wind tunnel with targeted innovations to address existing limitations. First, the full-scale wind tunnel prototype is improved by adding a three-stage boundary layer removal device, enabling the virtual model to achieve advanced performance metrics. Its structural dimensions are designed per wind tunnel principles, while boundary conditions are optimized to make test section airflow parameters (turbulence, airflow deflection angle, pressure gradient, boundary layer displacement thickness) match actual wind tunnel conditions, and overcome open-domain flaws.

To resolve the issue that existing validation focuses on simplified models, a Hong Qi real-vehicle model is used for aerodynamic characteristic simulation. An optimized mesh strategy enhances numerical simulation accuracy, and three common automotive simulation methods (realizable k-ε, SST k-ω, SST DES) are compared to analyze aerodynamic drag and lift accuracy. Moreover, this study addresses the gap in existing research regarding the evaluation of flow field metrics in wind tunnels, thereby comprehensively assessing the accuracy of vehicle aerodynamic performance in both computational wind tunnels and open areas.

Introduction to numerical wind tunnel

Numerical wind tunnel model

The numerical wind tunnel is a typical 3/4 opening return automobile wind tunnel, which is built with reference to the size and structure of the real car wind tunnel and simplified appropriately,Tongji University whole-vehicle aerodynamic wind tunnel.The wind tunnel is a full-size aerodynamic acoustic wind tunnel (AAWT) equipped with boundary layer control systems (BLCs). The BLCs effectively control the thickness of the boundary layer in the wind tunnel to minimize the interference of the boundary layer on the experimental results and ensure the reliability of the experimental data. Thus, the stable section, contraction section, nozzle, resident room, air collection port, and diffusion section are kept to be the same as those of the numerical wind tunnel model. The mass flow flows in from the inlet of the stable section and then flows out from the outlet of the diffusion section after being collected in the air collection port after passing through the resident room. Comprehensive domestic mainstream wind tunnel structure and wind tunnel design principles, after several rounds of modeling and iterative optimization, the numerical wind tunnel dimensions are shown in Table 1.

The nozzle area of the 3/4 opening reflux wind tunnel is 27.6 m2, the length of the test section is 15.5 m, and the exit area of the test section is 55.14 m2, which can provide aerodynamic tests for passenger cars. The basic model of the numerical wind tunnel is established, as shown in Fig. 1.

Numerical simulation setup

The overall mesh arrangement of the numerical wind tunnel is shown in Fig. 2. Given that the generation of the actual boundary layer is related to the local flow velocity and structure, the hexahedral mesh is generated by using the cut body mesh generator, and the thickness of the boundary layer is set up by partitioning.

The encrypted domain is selected mainly for the nozzle, the test section, the air collection port, and other flows with highly complex region settings. Given the different attachment states of the inner and outer walls of the nozzle, the graded encryption on both sides of the nozzle must be adopted. For the inner wall of the nozzle, the incoming flow is about to flow separation occurs. Thus, the fine surface flow must be captured. As a result, it adopts a 20 mm grid, and the outer wall of the nozzle adopts a 40 mm grid. The grid of the test section from the nozzle to the air collector is encrypted in the shape of a trapezoid, and an 80 mm grid is used for this part of the encryption. Given the separation caused by the impact of the airflow on the air inlet, a 40 mm encryption domain is adopted for the shape of the outer edge of the air inlet. The boundary layer is encrypted with anisotropic mesh, the near-ground encryption + Z direction mesh is 4 mm, and the overall encryption + Z direction mesh is 40 mm. After the mesh of each part of the numerical wind tunnel is encrypted according to the above, the final amount of mesh of the overall air wind tunnel is 70 million.

The ground boundary layer is thick in the initial simulation. Thus, a three-level boundary layer elimination device is used. The first level is the incoming boundary layer elimination device. However, the boundary layer elimination at the same time generates the vortex structure, which in turn generates a new boundary layer. Moreover, other boundary layer elimination devices are needed. Thus, the second level of boundary layer suction device is set. The outlet pressure of the first stage of suction is set to be greater than the outlet pressure of the second stage by using a two-stage suction device, and the elimination effect of the boundary layer is significantly improved. However, the device has a great effect on the axial static pressure gradient, and a great degree of suction produces a strong airflow deflection angle. Thus, a third-stage boundary layer blowing device is set. This device carries out flow supplementation to the low-velocity zone, thereby reducing the low-velocity zone in front of the moving floor. As a result, the thickness of the boundary layer displacement is reduced. The third-stage boundary layer elimination device is set up as in Fig. 3.

According to the principle of the three-stage boundary layer elimination system, the boundary conditions are set for three-stage devices to eliminate the boundary layer. The numerical wind tunnel boundary conditions are shown in Table 2.

First stage pressure outlet is 0pa; Second stage asymptotic function Synthetic velocity in the x, y and z directions are 38.89 m/s, 0,− 0.074*x− 0.428 m/s; Third stage velocity in the x, y and z directions are 38.89 m/s, 0.0, 2.0 m/s.

Optimize the y + value: Control the y + value in the range of 30–100 to balance the mesh accuracy and computational cost, too large or too small y + value will affect the accuracy and convergence of the turbulence model, reasonable optimization of the y + value can improve the accuracy of the turbulence simulation.Fig. 4 shows a view of the y + value of the empty wind tunnel.

Flow field quality in the empty wind tunnel

The turbulence degree that can measure the degree of pulsation of airflow velocity, the deflection angle of airflow, the pressure gradient that characterizes the horizontal buoyancy distribution in the test section, and the displacement thickness that can describe the maintenance of fluid continuity are selected to evaluate the flow field in the virtual wind tunnel through the appropriate boundary condition settings. Thus, the quality of the flow field in the test section of the wind tunnel is ensured is up to the standard, and the requirements of the military standard of the country are met. The indicators of the flow field of virtual wind tunnels are shown in Table 3.

Numerical settings

Geometric modeling and mesh strategies

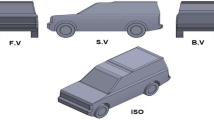

The size and shape of the test vehicle considerably affect the wind tunnel test results and the wind tunnel calibration. In this study, we investigate a certain model of Hong Qi. The length × width × height is 5.04 m × 1.91 m × 1.569 m,To validate the simulation accuracy, wind tunnel tests were conducted on the same vehicle model in the afore-mentioned baseline full-scale wind tunnel. The testing procedure initiated at 60 km/h, with incremental speed increases of 20 km/h per test cycle, ultimately reaching 140 km/h. This study presents the 140 km/h case as an example.

The wind tunnel tests measured a drag coefficient of 0.2945 for this vehicle model at 140 km/h. A corresponding full-vehicle numerical model was developed based on the actual vehicle, and the real vehicle is shown in Fig. 5.

The software used in this study is STAR-CCM + , and the mesh type is cut body mesh. The mesh encryption settings are listed in Table 4.

The dimensions and numerical encryption zones of the numerical wind tunnel computational domain and the rectangular computational domain are set up in the same way to minimize the influence of numerical errors on the results. For the numerical simulation of this model, a trimmed mesh was employed with surface cell sizes maintained between 4-16mm. The grid distribution of the sample vehicle is shown in Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9.

Figure. 9 shows the dimensionless wall distance distribution around the vehicle,along the vehicle surface, focusing on near-wall regions. Y + values indicate the suitability of near-wall meshes for turbulence models, which is critical for accurately capturing boundary layer flow and wall shear stress, thus ensuring reliable prediction of aerodynamic forces like drag.

Boundary condition

Two computational domains are set up in this study to verify the difference in results between the numerical wind tunnel and the rectangular computational domain commonly used in automobile development and to represent an OR surface (a horizontal, dry, and undisturbed road surface).

Rectangular open field

The dimensions of the traditional rectangular computational domain are set as follows to develop the fluid in the computational domain fully and reduce the interference of the wall with the flow field around the vehicle: length × width × height of 60 m × 10 m × 20 m. Moreover, the prototype model is placed at a distance of 15 m from the inlet, and the model is placed in the open domain as shown in Fig. 10.

The front of the rectangle is the velocity inlet at 140 km/h, the rear is the pressure outlet, and the rest of the setup is the wall condition. The open domain boundary conditions are set as shown in Table 5.

Numerical wind tunnel

The numerical wind tunnel computational domain model boundary conditions are set, as shown in Table 6, and the boundary conditions of the three-level boundary layer elimination system are set in the same way as those of the empty wind tunnel, as shown in Table 1.

Numerical method

The accurate and timely prediction of the airflow separation on the smooth surface of the car is important in the computational simulation of the automobile’s external flow field. Thus, the selection of a turbulence model is relatively demanding. For comparative analysis, this study selects three numerical simulation methods, namely, realizable k-ε, SST k-ω, and SST DES, which are commonly used in automotive simulation, to establish a numerical wind tunnel simulation model with a good fit to the actual wind tunnel experimental values.

As the most widely used turbulence model in the solution of automobile winding problems, the steady-state k-ε two-equation model is a high-Reynolds-number model derived under fully developed turbulent flow conditions and is suitable for regions with sufficiently large turbulent Reynolds numbers. The automobile turbulent flow field calculation involves the wall and the boundary layer covering the wall. The viscous bottom layer and the transition zone exist near the wall. The turbulent Reynolds number is very small, and the Reynolds stress and molecular viscous stress are of the same order of magnitude. The calculation must consider the effect of molecular viscosity.

Therefore, the realizable k-ε turbulence model is chosen, which has new turbulence control equations and transfer equations for the dissipation rate. It is also capable of highly accurate predictions in complex flows involving rotations, boundary layer separations under strong backpressure gradients, and reflux. Moreover, it is highly suitable for designing the automotive flow field in walled boundary layers for simulation25.

The steady-state k-ω two-equation turbulence model allows the transport equations for turbulent kinetic energy k and unit dissipation rate ω to be solved, thereby determining the aerodynamic coefficients without involving complex nonlinear decay functions like those required in the k-ε model. The SST k-ω turbulence model combines the advantages of the k-ε turbulence model, which performs well in the region outside the boundary layer, and the k-ω model, which is suitable for the near-wall treatment of the low Reynolds number case. Thus, the SST k-ω turbulence model can accurately predict the incoming flows and accurately simulate the separation phenomena under various pressure gradients. It also has advantages in the simulation of automotive flow fields. However, the two turbulence models are time averaged. Thus, the features of various sizes of vortices are erased, thereby failing to reflect the real vortex shedding phenomenon.

DES methods are common for hybrid RANS/LES models. Menter proposed a DES method based on the SST model26. The SST DES turbulence model introduces DES features to reduce turbulence viscosity, thereby realizing a smooth transition from RANS to LES with a sufficiently fine mesh. Combining the advantages of RANS and LES provides high accuracy and efficiency in complex flow simulations. Moreover, this combination is suitable for flow fields that require transient analysis.

Comparison of simulation results

This study evaluates the differences in the aerodynamic characteristics of different computational domains from the viewpoint of wind resistance coefficient and lift coefficient. The wind resistance coefficient CD is calculated, as shown in Eq. (1).

The lift coefficient CL is calculated, as shown in Eq. (2).

After several simulations, the simulation values of the wind resistance coefficient and lift coefficient under different calculation domains and numerical method settings are obtained. The results in Table 7 are obtained by comparing the simulation values with the test values.

The drag simulation accuracy and lift simulation accuracy obtained from different working conditions are compared, as shown in Fig. 11. The comparison of the numerical wind tunnel with the open domain shows that the accuracy of the numerical wind tunnel results is higher than that of the open domain results.

For numerical wind tunnel computational domain,as shown in Fig. 12, abundant small-scale vortices form around the wheels, underbody, and side skirts. This is due to the interaction between the vehicle and the wind tunnel floor, which enhances local flow shear and turbulence.The wake shows fragmented, less coherent vortices. Wind tunnel walls restrict horizontal diffusion of the wake, causing vortices to dissipate more rapidly.

Figure 13 shows the open-field Q-criterion diagram.Open-domain computational domain exhibit fewer small-scale vortices; flow around the body is smoother without lateral constraints from wind tunnel walls.The wake develops large-scale, highly coherent vortex structures that extend much farther downstream. Without wall constraints, vortices retain energy longer and evolve into more organized, elongated patterns. flow expands freely in all directions.

Conclusion

The following conclusions are drawn through the numerical simulation of the prototype vehicle model in the traditional rectangular computational domain and the virtual numerical wind tunnel computational domain and by comparing the simulation results of both and the test data in the real-vehicle wind tunnel:

-

(1)

With the lack of criteria for evaluating the quality of flow fields in empty wind tunnels in currently available studies,the numerical wind tunnel with three-stage suction device built based on the real-vehicle wind tunnel can better simulate the flow field characteristics in the real-vehicle wind tunnel, such as turbulence degree, airflow deflection angle, pressure gradient and boundary layer displacement thickness, which can be used as a calibration for the calibration of the empty wind tunnel, and provide a more accurate and reliable research methodology and research basis for the simulation of the vehicle simulation of numerical wind tunnels, and it can be used as an important tool for the study of automotive aerodynamics.

-

(2)

CFD simulations based on the quality of the flow field in a good empty wind tunnel are more reliable than existing studies.Based on the constructed numerical wind tunnel, the simulation accuracies of wind resistance coefficient and lift coefficient obtained by CFD simulation with different numerical methods are higher than the open-domain simulation accuracies. Under the condition of the same grid strategy and turbulence model, the use of a numerical wind tunnel can simulate the aerodynamic coefficients accurately. This finding is crucial to the development of new car models by enterprises.

In this study, the accuracy of vehicle aerodynamic performance prediction is improved by combining the realism of wind tunnel experiments and the flexibility of computational fluid dynamics simulation. The calculation ranges of the open and virtual wind tunnels are determined, the boundary conditions are accurately determined, and the mesh strategy is optimized, so that the virtual wind tunnel simulation technique can effectively improve the prediction accuracy of vehicle aerodynamic performance.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yi, C. et al. The application study of adaptive mesh refinement in automotive CFD. J. Chongqing Univ. Tech. (Natural Science) 38(5), 95–101 (2024).

Irigaray, O. et al. Adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) criteria comparison for the DrivAer model. Heliyon 10(11), 31966 (2024).

Xiaojing, W., Ran, G. & Long, M. Optimization design method of automobile aerodynamic shape based on multi-fidelity deep neural network. Acta Aerodynamica Sinica. 42(7), 103–111 (2024).

Rijns, S. et al. Integrated numerical and experimental workflow for high-performance vehicle aerodynamics In Automotive Technical Papers. (SAE International, 2024)

Xin, S. et al. Study on the correlation between digital wind tunnel simulation and open road simulation. Automot. Eng. 42(6), 759–764 (2020).

Huang, T. et al. Extended study of full-scale wind tunnel test and simulation analysis based on drivaer model. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 236(10–11), 2433–2447 (2021).

Josefsson, E., Hobeika, T. & Sebben, S. Evaluation of wind tunnel interference on numerical prediction of wheel aerodynamics. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 224, 104945 (2022).

Fu Y, Zhao Z, Ma X. Simulation calculation of aerodynamic performance of Mira model based on virtual wind tunnel. In 2nd International Conference on Applied Mathematics, Modelling, and Intelligent Computing (CAMMIC 2022): Vol. 12259. SPIE, 2022: 872–882.

Fu, Q. et al. Numerical simulation of vehicle aeroacoustics wind tunnel. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci. Edit.) 50(S1), 107–113 (2025).

Xiaochong, W.et.al Numerical wind tunnel simulation based on DrivAer model. In Annual Meeting of the Automotive Aerodynamics Branch of the Chinese Society of Automotive Engineering. Chongqing, China, 208-216 (2024)

Xu, X. et al. Research on the thermal flow field of automobile based on numerical climatic wind tunnel. In SAE Technical Paper Series (2024).

Stoll, D. & Wiedemann, J. Active crosswind generation and its effect on the unsteady aerodynamic vehicle properties determined in an open jet wind tunnel. SAE Int. J. Passenger Cars Mech. Syst. 11(5), 429–446 (2018).

Sebald J, Reiss J, Kiewat M, et al. Experimental and numerical investigations on time-resolved flow field data of a full-scale open-jet automotive wind tunnel. In SAE WCX Digital Summit. (SAE International, 2021)

Ljungskog, E., Sebben, S. & Broniewicz, A. Inclusion of the physical wind tunnel in vehicle CFD simulations for improved prediction quality. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 197, 104055 (2020).

Fu, C., Uddin, M. & Zhang, C. Computational analyses of the effects of wind tunnel ground simulation and blockage ratio on the aerodynamic prediction of flow over a passenger vehicle. Vehicles 2(2), 318–341 (2020).

Xu, X. et al. Experimental and numerical simulation of flow field characteristics in automotive environmental wind tunnel. In Chinese Society of Automotive Engineering Annual Conference and Exhibition, Shanghai, China 55–60 (2022).

Xu, X. et al. Research on the thermal flow field of automobile based on numerical climatic wind tunnel. In SAE Technical Paper Series. (2024)

Chen, Q. et al. Progress of national numerical wind tunnel (NNW) engineering for hypersonic applications. J. Aeronaut. 42(9), 625746 (2021).

Chen, Q. et al. FlowStar: National Numerical Wind Tunnel (NNW) general purpose CFD software for engineering nonstructures. J. Aeronaut. 42(9) 625739.

Hao, C. et al. Advances in viscous adaptive Cartesian grid methodology of NNW Project. Acta Aeronautica et Astronautica Sinica. 42(9), 625732 (2021).

Chen, Q. Progress of key technology research on national numerical wind tunnel (NNW) project. Sci. China: Tech. Sci. 51(11), 1326–1347 (2021).

Chen Q, Jianqiang C, Ma Y, et al. Design of a general-purpose software isomorphic hybrid solver for national numerical wind tunnel (NNW). J. Aerodynm.

Lei, H. et al. Design and development of national numerical wind tunnel (NNW) software automation integration and testing platform. J. Aerodynm. 38(6), 1158–1164 (2020).

Hanli, B., Xiaomeng, C. & Qiao, P. Development of a national numerical wind tunnel (NNW) integrated framework system. J. Aerodyn. 38(6), 1149–1157 (2020).

Tsan-Hsing, S. et al. A new kt Eddy viscosity model for high: Reynolds number turbulent flows. Comput. Fluid. 24(3), 227–238 (1995).

Menter, F. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 32(8), 1598–1605 (1994).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Major Science and Technology Program of Jilin Province (Project supported by the Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Program, China Grant No. 20220301013GX).The project number is No. 20220301013GX

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.M. and Y.L. wrote the main manuscript text. J.D. and J.Z. provided technical guidance and amendment, revised it critically for important intellectual content R.M., Y.Z. and X.Y. prepared Figs. 1–4. X.H. and S.H. prepared Figs. 5–8. P.G. and Z.W. drafted the work, prepared all tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding.

author on reasonable reguest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Y., Li, Y., Zhao, J. et al. High precision numerical simulation of passenger cars based on numerical wind tunnel. Sci Rep 15, 36033 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20040-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20040-7