Abstract

The relationship between blastocyst morphological quality and the risk of congenital malformations in assisted reproductive technology (ART) remains poorly understood, limiting clinical decision-making for embryo selection. We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 3986 frozen embryo transfer cycles (January 2014–June 2023) to evaluate whether blastocyst morphological quality influences the risk of congenital malformations. Blastocysts were classified according to Gardner’s grading system, and 1:2 propensity score matching was applied to control for maternal age, BMI, infertility characteristics, and other potential confounders. After matching, 1743 singleton births were analyzed (1162 good-quality vs. 581 poor-quality blastocysts). Baseline characteristics were well balanced between groups. The risk of congenital malformations was similar between good- and poor-quality groups (aOR 1.14, 95% CI 0.54–2.41, P = 0.7310; 1.72% vs. 2.07%), with no significant between-group differences in any ICD-10 organ-specific categories (all P > 0.10). Secondary outcomes showed no significant differences: preterm birth (aOR 0.80, 95% CI 0.57–1.12, P = 0.1976), low birth weight (aOR 1.26, 95% CI 0.72–2.19, P = 0.4172), other neonatal outcomes, and obstetric complications (aOR 0.89, 95% CI 0.64–1.22, P = 0.4629). These findings indicate that blastocyst morphological quality does not influence the risk of congenital malformations, supporting the use of morphologically poor blastocysts when high-quality alternatives are unavailable, which may reduce unnecessary discarding of embryos, alleviate patient anxiety, and improve treatment accessibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) has transformed the landscape of infertility treatment worldwide, with frozen-thawed embryo transfer (FET) cycles emerging as the predominant approach in modern fertility practice1,2. Despite progress in time‑lapse imaging and AI‑assisted evaluation, morphological assessment continues to serve as the cornerstone of embryo selection in IVF laboratories globally3,4.

The clinical implications of transferring morphologically poor-quality embryos have garnered increasing attention, particularly concerning potential birth defects. This issue has become increasingly pertinent as approximately 30–40% of available embryos are classified as poor quality according to standard morphological criteria5,6. The decision-making process becomes especially challenging in scenarios of limited embryo availability or within jurisdictions imposing regulatory restrictions on embryo creation7.

The relationship between embryo quality and congenital malformation risk remains controversial in current literature. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have produced conflicting results, with some investigations suggesting increased risks associated with poor-quality embryo transfers8,9, while others demonstrate comparable safety profiles between poor- and good-quality embryos10,11. These disparate findings may be attributed to substantial methodological heterogeneity across studies, including variations in embryo quality classification systems and insufficient control for potential confounding factors12.

The interpretation of existing research is further complicated by several methodological limitations. Current evidence is constrained by non-standardized embryo grading systems, limited statistical power for detecting rare congenital anomalies, and the conflation of fresh and frozen-thawed cycle outcomes. Moreover, inadequate adjustment for critical parental factors and insufficient long-term developmental follow-up have undermined the reliability of available data13. These methodological challenges underscore the necessity for more rigorously designed investigations.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the association between embryo quality and congenital malformation risk in frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer cycles.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Reproductive Medical Center of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University between January 2014 and June 2023. For each patient, only the first FET cycle with single blastocyst transfer that resulted in a singleton live birth was included. We excluded cycles involving donor sperm or oocytes, chromosomal abnormalities, endometriosis, Müllerian duct anomalies, endocrine disorders (including diabetes and thyroid disorders), or preimplantation genetic testing (PGT). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (approval number: 2024-KY-1203-001). The study design and implementation followed the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines14.

Blastocyst evaluation and group assignment

Blastocysts were graded according to the Gardner system15. Based on the 2022 Chinese Expert Consensus on Human Cleavage-stage Embryo and Blastocyst Morphological Evaluation16, good-quality blastocysts were defined as those achieving ≥ grade 3 expansion with inner cell mass and trophectoderm grades of AA, AB, BA, or BB on day 5, or ≥ grade 4 expansion with the same quality grades on day 6. All other blastocysts were classified as poor quality. Following these criteria, 3023 transfers were classified into the good-quality group and 963 into the poor-quality group.

Outcome measures and data collection

The primary outcome was congenital malformations, identified and classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10; codes Q00–Q99)17. Secondary outcomes included neonatal and obstetric outcomes. For neonatal outcomes, birth weight categories followed WHO standards18: low birth weight (LBW, < 2500 g), very low birth weight (VLBW, < 1500 g) and high birth weight (HBW, ≥ 4000 g). Fetal growth centiles were derived from the sex- and gestational age–specific Chinese birth weight-for-gestational-age reference curves19, and neonates were classified as small for gestational age (SGA, < 10th percentile), very SGA (VSGA, < 3rd percentile), large for gestational age (LGA, ≥ 90th percentile) and very LGA (VLGA, ≥ 97th percentile). NICU admission was defined as any transfer to a neonatal intensive care unit after birth.

For obstetric outcomes, gestational age was estimated by imputing the last menstrual period (LMP) as 14 days plus embryo age before the transfer date. Mode of delivery was categorized as spontaneous vaginal delivery or cesarean section. Preterm birth was defined as delivery before 37 completed weeks of gestation. Obstetric complications included premature rupture of membranes (PROM; rupture of membranes before the onset of labor); stillbirth (fetal death at ≥ 20 weeks’ gestation); placenta previa; gestational hypertension; gestational diabetes mellitus; cervical insufficiency; fetal distress; and amniotic fluid abnormalities, including oligohydramnios and polyhydramnios.

Clinical and laboratory data were retrospectively extracted from the electronic medical record (EMR). EMR variables included demographic characteristics (age, body mass index), infertility-related parameters (primary/secondary infertility, infertility factors, duration), treatment-related parameters (fertilization method, endometrial preparation protocol, embryo development day). For all EMR variables, we used the values documented on the day of embryo transfer. Follow-up data were collected through standardized telephone interviews conducted by trained nurses and included pregnancy complications, delivery details, neonatal outcomes, and congenital malformations.

Statistical analysis

To minimize selection bias, propensity score matching was performed20. The propensity score model included maternal age, body mass index, infertility type, fertilization method, endometrial preparation protocol, and embryo development day. A 1:2 nearest-neighbor matching algorithm with a caliper width of 0.05 standard deviations was applied. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median [Q1–Q3], as appropriate, and categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. Within-group normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test together with Q–Q plots, and homogeneity of variances was assessed using Brown–Forsythe (Levene-type) test. Summary results of normality and variance homogeneity tests are provided in Supplementary Table S1, and Q–Q plots with histograms are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. Based on these diagnostics, Welch’s t-test was used for approximately normal data and/or unequal variances, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for skewed distributions; categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the association between embryo quality and perinatal outcomes, with results presented as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical analyses were performed using EmpowerStats (EmpowerROS; X&Y Solutions, Inc., Boston, MA, USA), version 4.2 (https://www.empowerstats.com), which is based on R (version 4.3.1; https://www.r-project.org). Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 6265 patients who underwent single blastocyst transfer in their first cycle and delivered a singleton during the study period were initially screened. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: donor sperm/oocyte cycles (n = 149), chromosomal abnormalities (n = 1058), endometriosis (n = 250), Müllerian duct anomalies (n = 167), endocrine disorders including diabetes and thyroid disorders (n = 174), or preimplantation genetic testing cycles (n = 481). After applying these exclusion criteria, 3986 patients were included in the final analysis.

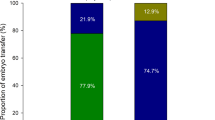

Baseline characteristics

As presented in Table 1, the study demonstrated that significant differences in baseline characteristics were observed between the good-quality (N = 3023) and poor-quality (N = 963) blastocyst groups prior to propensity score matching (PSM). The good-quality group had a higher proportion of younger women (< 30 years: 43.04% vs. 33.33%) and men (< 30 years: 37.16% vs. 26.06%), lower basal FSH levels (6.25 ± 1.50 vs. 6.54 ± 1.64 IU/L, P < 0.001), higher basal AMH levels (5.02 ± 3.08 vs. 4.07 ± 2.90 ng/mL, P < 0.001), and a greater proportion of primary infertility (43.86% vs. 32.50%, P < 0.001). Additionally, the good-quality group had a shorter infertility duration (≤ 2 years: 38.31% vs. 28.05%, P < 0.001), a higher proportion of primiparous women (68.38% vs. 54.41%, P < 0.001), and more conventional IVF cycles (73.77% vs. 69.57%, P = 0.011). Treatment-related parameters also differed, with the good-quality group having more hormone therapy cycles for endometrial preparation (67.85% vs. 57.63%, P < 0.001) and a higher proportion of day 5 embryo transfers (87.83% vs. 61.99%, P < 0.001). After PSM, 1,743 cycles were included (1,162 good-quality and 581 poor-quality blastocyst transfers), and baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the two groups, with no significant differences in maternal age (32.4 ± 4.0 vs. 32.5 ± 4.1 years, P = 0.4326), BMI (21.8 ± 3.1 vs. 21.9 ± 3.1 kg/m2, P = 0.5495), paternal age (P = 0.9133), basal FSH (6.40 ± 1.53 vs. 6.36 ± 1.51 IU/L, P = 0.6169), basal AMH (4.51 ± 2.76 vs. 4.50 ± 3.11 ng/mL, P = 0.9417), primary infertility (34.60% vs. 34.60%, P = 1.0000), infertility duration (≤ 2 years: 29.00% vs. 28.74%, P = 0.9553), or primiparity (55.77% vs. 56.97%, P = 0.6696). Treatment-related parameters, including the proportion of conventional IVF cycles (73.41% vs. 71.77%, P = 0.5051), hormone therapy cycles (60.93% vs. 60.07%, P = 0.7682), and day 5 embryo transfers (91.48% vs. 89.67%, P = 0.2514), were also comparable, indicating that PSM effectively minimized baseline differences between the two groups.

Neonatal and obstetric outcomes

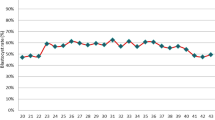

As shown in Table 2, after PSM, the incidence of congenital malformations was comparable between the good-quality (N = 1162) and poor-quality (N = 581) blastocyst groups (1.72% vs. 2.07%, P = 0.7525). Birth weight categories, including very low birth weight (VLBW, 0.60% vs. 0.86%, P = 0.7587), low birth weight (LBW, 3.10% vs. 3.96%, P = 0.4260), and high birth weight (HBW, 0.86% vs. 1.72%, P = 0.1765), were also similar. Other neonatal outcomes, such as mean gestational age at birth (37.89 ± 2.63 vs. 38.00 ± 2.51 weeks, P = 0.4025), birth weight (3407.32 ± 524.86 vs. 3442.86 ± 559.61 g, P = 0.2110), and birth length (50.39 ± 2.02 vs. 50.42 ± 2.12 cm, P = 0.8202), showed no significant differences. The rates of very small for gestational age (VSGA, 0.69% vs. 0.52%, P = 0.9148), small for gestational age (SGA, 2.75% vs. 3.10%, P = 0.7998), large for gestational age (LGA, 30.72% vs. 33.91%, P = 0.1966), and very large for gestational age (VLGA, 14.29% vs. 16.01%, P = 0.3784) were also comparable. NICU admission rates were extremely low, with no admissions in the good-quality group and only one case (0.17%) in the poor-quality group (P = 0.7236). Stillbirth rates were similarly low and showed no significant differences (0.34% vs. 0.52%, P = 0.8935).

Obstetric outcomes were also comparable between the two groups. The overall rate of obstetric complications (12.56% vs. 11.88%, P = 0.7378) and specific complications, including gestational hypertension (4.82% vs. 3.10%, P = 0.1202), gestational diabetes mellitus (3.01% vs. 4.65%, P = 0.1095), fetal distress (0.43% vs. 0.00%, P = 0.2677), and premature rupture of membranes (3.44% vs. 2.58%, P = 0.4102), showed no significant differences. These findings indicate that blastocyst quality was not associated with significant differences in neonatal or obstetric outcomes. Detailed test statistics for continuous outcomes after PSM are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Multivariate analysis of neonatal and obstetric outcomes

Multivariate analysis confirmed that blastocyst quality was not significantly associated with adverse neonatal or obstetric outcomes after adjusting for confounders (Table 3). For neonatal outcomes, no significant differences were observed in congenital malformations (adjusted OR = 1.14, 95% CI 0.54–2.41, P = 0.7310), preterm birth (adjusted OR = 0.80, 95% CI 0.57–1.12, P = 0.1976), or birth weight categories, including VLBW, LBW, and HBW (all P > 0.05). Obstetric outcomes, including mode of delivery (adjusted OR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.68–1.12, P = 0.2806) and overall complications (adjusted OR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.64–1.22, P = 0.4629), were also comparable.

Congenital malformation analysis

Detailed analysis of congenital malformations based on ICD-10 codes (Table 4) revealed no significant differences between the good-quality (N = 1162) and poor-quality (N = 581) blastocyst groups. The overall rate of congenital malformations was low and comparable (1.72% vs. 2.07%, P = 0.6138). Specific malformations, including congenital heart defects (Q21), spina bifida (Q05), and chromosomal abnormalities (Q90, Q99), occurred at very low frequencies, with no statistically significant differences (all P > 0.05). Rare malformations, such as congenital skin anomalies (Q82) and musculoskeletal anomalies (Q79), were observed only in the poor-quality group (0.34% each), but these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.2110 for both). Cases of multiple malformations were extremely rare, with only one case (0.09%) in the good-quality group and none in the poor-quality group (P = 0.4794), further confirming that blastocyst quality was not associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations.

Discussion

In this propensity score-matched cohort study of 1,743 frozen-thawed single blastocyst transfer cycles, we found no significant difference in congenital malformation rates between good- and poor-quality embryo groups (1.72% vs. 2.07%, P = 0.7525). This finding remained consistent when congenital malformations were categorized by organ system according to ICD-10 codes, suggesting that poor embryo morphology alone may not be associated with an increased risk of birth defects.

Previous studies investigating the relationship between embryo quality and offspring safety are relatively limited. In a case–control study comparing 74 very poor quality (VPQ) embryos with 1507 top quality (TQ) embryos, Mendoza et al. demonstrated that VPQ embryo transfer was not associated with increased congenital malformations (1.35% vs. 1.72%) or perinatal complications21. A recent prospective study by Zhang et al. provided valuable long-term follow-up data, demonstrating that children aged 4–6 years conceived from poor-quality embryos exhibited comparable metabolic indicators and cognitive development to those from good-quality embryos in fresh cleavage-stage transfers22. Consistent findings were reported in several studies focusing on fresh embryo transfer cycles. Oron et al. analyzed 1541 fresh single embryo transfers and found no association between poor embryo quality and adverse obstetric or perinatal outcomes after adjusting for maternal variables23. Similarly, both Bouillon et al. and Akamie et al. demonstrated that single poor-quality blastocyst transfer did not adversely affect obstetric or perinatal outcomes compared to good-quality blastocysts13,24. Although these supporting studies were conducted in fresh transfer cycles rather than frozen-thawed embryo transfers as in our study, their findings collectively suggest the safety of poor-quality embryo transfers.

In contrast, some studies have reported different results. In a large-scale population-based registry study, Abel et al. reported that poor-quality embryos were associated with higher rates of abnormalities, particularly major anomalies and musculoskeletal abnormalities25. However, several methodological limitations warrant consideration when interpreting these results. First, the study design did not distinguish between fresh and frozen-thawed cycles in the analysis, and twin pregnancies were included in the study population. Second, data collection from multiple IVF centers (central, satellite and interstate clinics) may introduced potential inter-observer variations in embryo grading. Third, significant baseline differences existed between the study groups, including ICSI utilization rates, FET proportions, and treatment locations (P < 0.001). Additionally, the embryo grading was performed using an in-house system that did not separately assess trophectoderm and inner cell mass quality, which might have affected the accuracy of embryo quality classification and limited both the generalizability of their findings and the possibility for independent validation in other centers.

Birth weight outcomes have also been a focus of investigation in relation to embryo quality. Two independent studies reported an association between poor-quality embryos and reduced birth weight. Zhang et al. and Huang et al. both found that singletons born from poor-quality blastocysts had lower birth weights compared to those from good-quality blastocysts26,27. However, the interpretation of these findings requires careful consideration of their methodological limitations. Both studies enrolled relatively small cohorts (Huang 2020, n = 1306; Zhang 2020, n = 1207) and exhibited marked between-group imbalances in key baseline covariates, including day of embryo transfer (day 5 vs. day 6), year of treatment, and oocyte yield per cycle (total and MII oocytes). While Zhang et al. focused specifically on frozen–thawed transfers, they applied embryo-quality classification criteria that differ from those used in other reports, complicating direct comparisons. By contrast, our study retained a larger analytic sample after propensity-score matching (n = 1743) and achieved balance across these critical variables. In addition, the prior studies restricted outcomes to birth weight and did not interrogate the broader spectrum of perinatal endpoints, particularly congenital malformations. Finally, considering the research locations, investigative teams and periods of data collection, the datasets used in the two reports may partially overlap, limiting the independence of their findings and warranting caution in interpretation and cross-study comparison.

Several potential mechanisms might explain why poor embryo morphology alone does not necessarily translate to increased congenital malformation risks. First, embryo morphological assessment is primarily based on static observations at specific time points, which may not fully reflect the dynamic nature of embryonic development and the embryo’s intrinsic developmental potential28,29. Second, studies have shown that embryos possess remarkable developmental plasticity and compensatory mechanisms during early development. Poor morphological features such as fragmentation or irregular blastomere size may not necessarily indicate compromised genetic integrity or developmental potential30. Furthermore, the successful implantation of a poor-quality embryo might itself indicate the embryo’s inherent viability despite suboptimal morphological appearance31.

Several limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, despite propensity score matching, unmeasured confounding factors might still exist. Second, our follow-up period was limited to birth outcomes and early infancy; therefore, long-term developmental outcomes remain unknown. Third, although our sample size was substantial, some rare congenital malformations might have been missed due to their extremely low incidence rates. Fourth, our study was conducted at a single center, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings to other populations or centers using different embryo grading systems.

Future research directions should focus on several aspects. First, large-scale multicenter studies with standardized embryo grading systems are needed to validate our findings across different populations and clinical settings32. Second, long-term follow-up studies should be conducted to evaluate developmental, cognitive, and health outcomes beyond the perinatal period33. Third, the integration of time-lapse imaging and artificial intelligence-based assessment tools might provide more objective and comprehensive evaluation of embryo quality34. Finally, investigation of molecular and genetic markers in conjunction with morphological assessment might help better understand the relationship between embryo quality and developmental outcomes35.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that poor-quality embryo transfer does not significantly increase the risk of congenital malformations compared to good-quality embryo transfer. These findings provide reassuring evidence for the use of poor-quality embryos in cases where embryo selection is limited. However, given the limitations of this study, larger multicenter studies with longer follow-up periods are needed to validate these results further. Long-term assessment of offspring health and developmental outcomes remains a critical area for future investigation.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Assisted reproductive technology

- AMH:

-

Anti-Müllerian hormone

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FET:

-

Frozen embryo transfer

- FSH:

-

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- GQE:

-

Good-quality embryo

- HBW:

-

High birth weight

- ICD:

-

International classification of diseases

- ICSI:

-

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection

- IVF:

-

In vitro fertilization

- LBW:

-

Low birth weight

- LGA:

-

Large for gestational age

- NICU:

-

Neonatal intensive care unit

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCOS:

-

Polycystic ovary syndrome

- PQE:

-

Poor-quality embryo

- PSM:

-

Propensity score matching

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SGA:

-

Small for gestational age

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology

- VLBW:

-

Very low birth weight

- VLGA:

-

Very large for gestational age

- VSGA:

-

Very small for gestational age

- VPQ:

-

Very poor quality

- TQ:

-

Top quality

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Bosch, E., De Vos, M. & Humaidan, P. The future of cryopreservation in assisted reproductive technologies. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 67 (2020).

Xiong, F. et al. Clinical outcomes after transfer of blastocysts derived from frozen–thawed cleavage embryos: A retrospective propensity-matched cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 300, 751–761 (2019).

Hanassab, S. et al. The prospect of artificial intelligence to personalize assisted reproductive technology. npj Digit. Med. 7, 55 (2024).

Salih, M. et al. Embryo selection through artificial intelligence versus embryologists: A systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Open 2023, hoad031 (2023).

Zou, H. et al. Blastocyst quality and reproductive and perinatal outcomes: A multinational multicentre observational study. Hum. Reprod. 38, 2391–2399 (2023).

Capalbo, A. et al. Correlation between standard blastocyst morphology, euploidy and implantation: An observational study in two centers involving 956 screened blastocysts. Hum. Reprod. 29, 1173–1181 (2014).

Guidance on the limits to the number of embryos to transfer: A committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 116, 651–654 (2021).

Wen, J. et al. Birth defects in children conceived by in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection: A meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 97, 1331–1337 (2012).

Davies, M. J. et al. Reproductive technologies and the risk of birth defects. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 1803–1813 (2012).

Zhu, J. et al. Does IVF cleavage stage embryo quality affect pregnancy complications and neonatal outcomes in singleton gestations after double embryo transfers?. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 31, 1635–1641 (2014).

Huang, X., Bi, B., Lu, X., Chao, L. & Cui, Q. Effect of low-quality embryo on adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes. RHS 9, p37 (2024).

Glujovsky, D. et al. Cleavage-stage versus blastocyst-stage embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, (2022).

Bouillon, C., Celton, N., Kassem, S., Frapsauce, C. & Guérif, F. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes of singletons after single blastocyst transfer: Is there any difference according to blastocyst morphology?. Reprod. Biomed. Online 35, 197–207 (2017).

Von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull. World Health Organ. 85, 867–872 (2007).

Gardner, D. K. & Schoolcraft, W. B. In vitro culture of human blastocysts. In: Jansen, R. & Mortimer, D. (eds.) Towards Reproductive Certainty: Fertility and Genetics Beyond 1999: The Plenary Proceedings of the 11th World Congress on In Vitro Fertilization & Human Reproductive Genetics 378–388 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 1999).

Chinese Association of Reproductive Medicine, Li D. & Li R. Expert consensus on human embryo morphological assessment: cleavage-stage embryos and blastocysts grading criteria. Chin. J. Reprod. Contracept. 42, 1218–1225 (2022).

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision. (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2019).

World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 12. UNICEF–WHO Low Birthweight Estimates: Levels and Trends 2000–2015. (2019).

Zhu, L. et al. Chinese neonatal birth weight curve for different gestational age. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 53, 97–103 (2015).

Austin, P. C. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar. Behav. Res. 46, 399–424 (2011).

Mendoza, R. et al. congenital malformations, chromosomal abnormalities and perinatal results in IVF/ICSI newborns resulting from very poor quality embryos: A case-control study. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 79, 83–89 (2015).

Zhang, C.-X. et al. Embryo morphologic quality in relation to the metabolic and cognitive development of singletons conceived by in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection: A matched cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 227(479), e1-479 (2022).

Oron, G., Son, W.-Y., Buckett, W., Tulandi, T. & Holzer, H. The association between embryo quality and perinatal outcome of singletons born after single embryo transfers: A pilot study. Hum. Reprod. 29, 1444–1451 (2014).

Akamine, K. et al. Comparative study of obstetric and neonatal outcomes of live births between poor- and good-quality embryo transfers. Reprod. Med. Biol. 17, 188–194 (2018).

Abel, K., Healey, M., Finch, S., Osianlis, T. & Vollenhoven, B. Associations between embryo grading and congenital malformations in IVF/ICSI pregnancies. Reprod. Biomed. Online 39, 981–989 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. The impact of embryo quality on singleton birthweight in vitrified-thawed single blastocyst transfer cycles. Hum. Reprod. 35, 308–316 (2020).

Huang, J. et al. Poor embryo quality is associated with a higher risk of low birthweight in vitrified-warmed single embryo transfer cycles. Front. Physiol. 11, 415 (2020).

Lundin, K. & Ahlström, A. Quality control and standardization of embryo morphology scoring and viability markers. Reprod. Biomed. Online 31, 459–471 (2015).

Gardner, D. K. & Balaban, B. Assessment of human embryo development using morphological criteria in an era of time-lapse, algorithms and ‘OMICS’: Is looking good still important?. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 22, 704–718 (2016).

Hnida, C. & Ziebe, S. Total cytoplasmic volume as biomarker of fragmentation in human embryos. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 21, 335–340 (2004).

Zhan, Q., Ye, Z., Clarke, R., Rosenwaks, Z. & Zaninovic, N. Direct unequal cleavages: Embryo developmental competence, genetic constitution and clinical outcome. PLoS ONE 11, e0166398 (2016).

Alpha Scientists in Reproductive Medicine and ESHRE Special Interest Group of Embryology et al. The Istanbul consensus workshop on embryo assessment: Proceedings of an expert meeting. Hum. Reprod. 26, 1270–1283 (2011).

Racowsky, C., Kovacs, P. & Martins, W. P. A critical appraisal of time-lapse imaging for embryo selection: Where are we and where do we need to go?. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 32, 1025–1030 (2015).

Zaninovic, N. & Rosenwaks, Z. Artificial intelligence in human in vitro fertilization and embryology. Fertil. Steril. 114, 914–920 (2020).

Munné, S. & Wells, D. Detection of mosaicism at blastocyst stage with the use of high-resolution next-generation sequencing. Fertil. Steril. 107, 1085–1091 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the medical and nursing staff at the Reproductive Medical Center of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University for their valuable assistance with patient follow-up and data collection.

Funding

This study was supported by the 2024 Joint Construction Project of the Health Commission of Henan Province (Grant No. LHGJ20240235).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.D. conceptualized and designed the study protocol, performed the primary data analysis, and drafted the original manuscript. T.Y. participated in data collection and conducted statistical analyses. W.F. contributed to data interpretation, performed data validation and manuscript revision. H.K. developed the research methodology, provided overall supervision, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (approval number: 2024-KY-1203–001). At the time of initial treatment, all patients provided written informed consent for the use of their medical records in future research studies. Patient data were anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis to ensure confidentiality.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, L., Ye, T., Fan, W. et al. Blastocyst quality and congenital malformation risk in singleton births after frozen embryo transfer. Sci Rep 15, 36326 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20150-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20150-2