Abstract

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors provide new opportunities to reduce global burden of lung cancer. However, adverse drug events (ADEs) pose significant risks to patient health, warranting systematic attention. Data on ADEs associated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for lung cancer treatment were collected from FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database between January 2014 and June 2023. Logistic regression was used to explore potential factors related to death. Signal mining for ADEs was performed using reporting odds ratio (ROR) and Bayesian Confidence Propagation Neural Network (BCPNN) methods, which revealed toxicity characteristics of these inhibitors among different system organ classes (SOCs) in terms of the number of both ADEs and ADE signals, and the signal strength. Additionally, factors associated with the timing of the first ADE were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis tests. A total of 36,387 reports were collected. It is indicated that patients aged 65 years above, male, with small-cell lung cancer, treated with PD-1 inhibitors, without chemotherapy combination, experiencing earlier first ADE occurrence, and with more ADEs were at higher risk of death. Signal mining revealed 175, 189, 74, and 123 ADE signals for nivolumab (N), pembrolizumab (P), durvalumab (D), and atezolizumab (A), respectively. For SOC characteristics, ADEs associated with N were most frequently distributed in ‘General disorders and administration site conditions’, with the highest signal strength in ‘Endocrine disorders’. P had the highest ADE signal frequency and strength in ‘Immune system disorders’. For D, the highest frequency of ADEs and ADE signals, and the highest signal strength were in ‘Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders’. Uniquely, A exhibited significant signal strength in ‘Blood and lymphatic system disorders’. ‘Blood and lymphatic system disorders’ and ‘Endocrine disorders’ had the earliest and latest ADE onset respectively. Death outcome and chemotherapy combinations were associated with earlier onset. And significant timing differences existed among different inhibitors. Based on 36,387 reports, this study comprehensively reveals the characteristics of ADEs associated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, providing valuable reference for their future clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer is a highly malignant tumor that ranks first and second globally in terms of new deaths and new cases, respectively, accounting for 18% of all cancer-related deaths and 11.4% of new cases1.

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, two types of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), function by competitively binding to PD-1/PD-L1, preventing tumor cells from escaping immune surveillance, and restoring T-cell-mediated tumor suppression2. Although the safety profile of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors is significantly better than that of chemotherapy3,4, they still carry a considerable risk of immune-related adverse events (irAEs)4. Severe adverse drug events (ADEs) can substantially impact patient survival and quality of life5. ADEs associated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in lung cancer treatment affect multiple organs or tissues6. Early identification and intervention can prevent the progression to severe complications7. However, due to the relatively short time since their introduction and the stringent standards of randomized controlled trials (RCTs)8, large-scale data on ADEs remain limited. While pharmacovigilance studies can partially address this gap, they often focus on ADEs in specific organs or systems9,10,11 or are limited to organ/system levels without examining specific ADEs12. Given the differences in ADE frequency across cancer types13,14, more detailed and comprehensive studies on ADEs specifically in lung cancer are needed.

This study focuses on lung cancer patients and aims to analyze ADEs following PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors treatment using real-world data. By examining serious events, ADE frequency and strength characteristics, and ADE onset timing, the study seeks to provide insights for early identification and management of ADEs.

Methods

Data collection and processing

Considering that the first PD-1 inhibitor, nivolumab (N), was approved in the United States at the end of 2014, data from the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) database from January 2014 to June 2023 were collected. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) The drug indication was lung cancer (search terms listed in Table S1). (2) The primary suspect (PS) drug causing the ADE was the PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor (search terms listed in Table S1). And the exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Reports withdrawn from the FAERS database. (2) Duplicate reports. Notably, ADEs were represented by preferred terms (PT). These PTs were derived by converting the ‘PT’ field in the FAERS database using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA).

Analysis of serious events

The proportions of serious events, including death, life-threatening events, disability, hospitalization, and other serious events (corresponding to the ‘DE’, ‘LT’, ‘DS’, ‘HO’ and ‘OT’ codes in the ‘OUTC_COD’ field, respectively), were compared across different drugs. Logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs), using N as the reference. Furthermore, differences in characteristics between the deceased and non-deceased groups (α = 0.05) were analyzed to identify potential factors associated with death. The definition of combination chemotherapy is that ‘PROD_AI’ field includes both the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor studied and chemotherapy. The search terms of chemotherapy in FAERS database are detailed in Table S115.

ADE signal mining and system organ class (SOC) distribution

ADE signal mining was conducted using two methods16: (1) Reporting odds ratio (ROR): Criteria included a ≥ 3, the lower 95% confidence interval (CI) limit of ROR(ROR025) > 1, and the false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. (2) Bayesian Confidence Propagation Neural Network (BCPNN): Criteria included a ≥ 3, the lower limit of the 95%CI of the information component (IC025) > 0, and FDR < 0.05. The ROR method has the advantages of simple calculation, reduced selection bias in the control group, and high sensitivity, but it has relatively low specificity and is prone to false positives. The BCPNN method combines Bayesian logic and neural network structure to achieve more stable results and higher specificity. The intersection of signals identified by both methods was used as the final ADE signal set (Table S2, Table S3) to reduce result bias caused by a single algorithm17. Calculations were performed using R software.

SOC classification of PTs was based on MedDRA, excluding ADEs related to non-drug factors or indications, such as ‘Congenital, familial and genetic disorders’, ‘Pregnancy, puerperium, and perinatal conditions’, ‘Product issues’, ‘Neoplasms benign, malignant, and unspecified (including cysts and polyps) ‘, ‘Surgical and medical procedures’, and ‘Social circumstances’.

Only ADEs with a reporting frequency ≥ 0.1% or a signal strength of IC025 > 1.5 (moderate or higher signal strength) were presented and a summary of ADE signals was plotted. High mortality ADEs were defined as ADEs with a mortality reporting frequency higher than that of other ADEs associated with the drug (based on chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, α = 0.05). ADE signals with 1.5 < IC025 ≤ 3 were classified as moderate strength, and those with IC025 > 3 as high strength18.

SOC characteristics of ADEs

The SOC characteristics of ADEs for N, pembrolizumab (P), durvalumab (D), and atezolizumab(A) were analyzed in three aspects: (1) The number of ADEs reported in each SOC and the SOC distribution of ADE signals. (2) Signal strength of SOCs, calculated using ROR02518 (Table S2 and Table S3). (3) Differences in ADEs within each SOC across different age and gender groups were analyzed using logistic regression models.

Analysis of ADE onset time

The timing of ADEs in each SOC was analyzed. Timing was calculated as the interval between the ADE onset date and the drug initiation date. Only reports with a single ADE and complete ADE onset and drug initiation dates (specified to year, month, and day) were included. Median and interquartile range (IQR) of ADE onset times were calculated for each SOC.

Among the population with onset and drug initiation dates, factors related to the timing of the first ADE were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests.

Results

Basic characteristics of patients

A total of 36,387 reports were included, with the following distribution of patients treated by drug: N (15,175), P (10,632), D (4,589), and A (5,991). Reports from patients aged ≥ 65 years accounted for the highest proportion (47.6%). Male patients outnumbered females by a ratio of 1.97:1. The primary indication was non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), accounting for 71.3%. And serious events (except for ‘non-serious events’) made up 92.7% of reports. Detailed characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Analysis of serious events

Comparison between drugs

The study compared the proportions of serious events among ICIs of N, P, D, and A (see Fig. 1).

Death: Compared to N, the death proportions were lower for P (OR = 0.68 [95% CI: 0.64–0.72]), D (OR = 0.66 [0.62–0.72]), and A (OR = 0.60 [0.56–0.64]). Life-threatening: P (OR = 1.48 [1.35–1.63]) and D (OR = 1.28 [1.13–1.45]) had higher proportions than N, while A (OR = 0.72 [0.63–0.82]) had lower proportions. Disability: Higher proportions were observed for P (OR = 2.32 [2.00-2.70]) and D (OR = 1.35 [1.08–1.67]) than N, but there was no statistical difference for A (OR = 0.84 [0.65–1.05]). Hospitalization: P (OR = 1.20 [1.14–1.26]) and A (OR = 1.14 [1.07–1.21]) had higher proportions, while D (OR = 0.70 [0.65–0.75]) had lower proportions compared to N. Other serious events: All three drugs showed lower proportions compared to N (The ORs of P, D, A were 0.54 [0.51–0.58], 0.22 [0.21–0.24], and 0.17 [0.16–0.18], respectively).

Differences in characteristics of deceased and Non-Deceased populations

Logistic regression analysis revealed the following factors associated with higher death risk: (1) Age ≥ 65 years, (2) small cell lung cancer (SCLC), (3) Male patients, (4) PD-1 inhibitors, (5) Patients not receiving combination chemotherapy, (6) Earlier onset of the first ADE, (7) A greater number of ADEs reported (Table 2).

ADE signals mining and SOC distribution

Using combined ROR and BCPNN methods, ADE signals were identified as follows:

N: 175 signals. P: 189 signals. D: 74 signals. A: 123 signals. ADEs with a reporting frequency ≥ 0.1% or a signal strength of IC025 > 1.5 (moderate or higher signal strength) were presented (Figure S1-Figure S4).

SOC characteristics of ADEs

Distribution of ADEs and ADE signals across SOCs

The SOC distribution characteristics of ADEs were detailed based on the reported number of ADEs and the identified ADE signals (Table S4 and Fig. 2).

For N, the highest numbers of ADEs were observed in ‘General disorders and administration site conditions’ (7192 ADEs), while the highest numbers of ADE signal was observed in ‘Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders’ (30 signals).

In the case of P, ADEs were distributed relatively evenly among SOCs, but ‘Immune system disorders’ exhibited a significantly higher frequency of ADE signals (61 signals) compared to other SOCs.

For D, both the number of ADEs (2678) and ADE signals (27) were predominantly concentrated in ‘Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders.’

Finally, for A, the distribution of both ADEs and ADE signals was relatively balanced across SOCs. The highest numbers were recorded in ‘General disorders and administration site conditions’ (2750 ADEs) and ‘Immune system disorders’ (22 signals), respectively.

Signal strength of ADEs occurring in SOCs

The SOCs with ADE signal strength exceeding the background level for all four ICIs (N, P, D, and A) were ‘Endocrine disorders’, ‘Hepatobiliary disorders’, ‘Immune system disorders’, and ‘Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders’. Specifically, in N, the signal strength for ‘Endocrine disorders’ was significantly higher than that of other SOCs. For P, both ‘Endocrine disorders’ and ‘Immune system disorders’ exhibited higher signal strength. In D, ‘Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders’ demonstrated the highest signal strength. Notably, A was the only drug that showed a higher signal strength than the background in ‘Blood and lymphatic system disorders’. Details were provided in Table S5 and Fig. 3.

Population characteristics of SOC in ADEs

A multivariate logistic regression model was developed using age, gender, and specific PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor as independent variables to compare the distribution of SOC in ADEs by age and gender (α = 0.05). The results indicate that, among the ADEs reported in the FAERS database (See details in Table S6):

ADEs associated with the SOC categories of ‘Ear and labyrinth disorders’, ‘Eye disorders’, ‘Gastrointestinal disorders’, ‘General disorders and administration site conditions’, ‘Metabolism and nutrition disorders’, ‘Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders’, ‘Nervous system disorders’, and ‘Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders’ were more frequently reported in females than in males. In contrast, ADEs related to ‘Immune system disorders’, ‘Infections and infestations’, and ‘Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders’ were less frequently reported in females than in males.

Furthermore, when comparing patients aged 65 years or older to those under 65, the following trends were observed: ADEs in the categories of ‘Immune system disorders’, ‘Infections and infestations’, ‘Investigations’, and ‘Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders’ were more commonly reported in patients aged 65 or older. Conversely, ADEs categorized as ‘Gastrointestinal disorders’ were reported less frequently in patients aged 65 or older.

Analysis of ADE onset time

Distribution of ADE events across SOCs

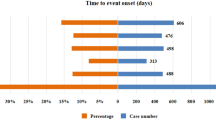

Two SOCs with very few cases were excluded from the analysis: ‘Ear and labyrinth disorders’ (9 cases) and ‘Reproductive system and breast disorders’ (11 cases). Among the remaining SOCs, ‘Blood and lymphatic system disorders’ had the earliest onset, with a median time of 26 days, whereas ‘Endocrine disorders’ had the latest onset, with a median time of 115 days. The median onset times for ADEs in the other SOCs ranged from 36 to 92 days (Fig. 4).

Factors associated with the onset time of the first ADE

An analysis of factors potentially associated to the first ADE revealed that, in patients with a death outcome and those receiving combination chemotherapy, the first ADE occurred significantly earlier (P < 0.001 for both factors). Additionally, the onset of the first ADE varied significantly depending on the specific PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor used: the median time from earliest to latest onset for the four ICIs is P, A, D, and N (Fig. 5).

Analysis of factors associated with the onset of the first ADE (A) Time of the first ADE in different age groups. (B) Time of the first ADE in different gender. (C) Time of the first ADE in those who died or not. (D) Time of the first ADE in cancer subtype groups. (E) Time of the first ADE after treatment with different ICIs. (F) Time of the first ADE with or without combination chemotherapy

Discussion

Based on FAERS database, we explored the ADE characteristics of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors used in the treatment of lung cancer patients from three perspectives, including serious events, ADE frequency and strength characteristics, and ADE onset timing.

The analysis of factors potentially associated with death revealed that advanced age, male gender, SCLC, treatment with PD-1 inhibitors, absence of combination chemotherapy, earlier ADE onset, and a greater number of ADEs are high-risk factors for death. There is ongoing debate about whether age can be a predictor of survival rates following ICIs treatment19. As physiological reserves decline with age, older patients are less equipped to manage the impacts of ADEs, exacerbating their effects20. Regarding gender, finding from Jin et al.21 suggests that female lung cancer patients have a significantly lower risk of death following ICIs treatment, consistent with the conclusions of this study. Compared to NSCLC, the higher malignancy of SCLC22 likely contributes to the higher mortality in this subgroup. Although PD-1 inhibitors are more effective than PD-L1 inhibitors23, they are associated with a higher risk of severe irAEs24, partially explaining the higher mortality observed among patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors. Furthermore, this study confirmed that combination therapy with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and chemotherapy was associated with higher survival rates, consistent with previous research25,26.

This study identified both common and specific ADE patterns associated with different PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in lung cancer treatment.

Commonalities: In terms of the number of ADEs, the number of ADE signals, and signal intensity distributed across SOCs, ADEs in respiratory system disorders were consistently reported at high frequencies across all four drugs. Previous studies have shown that PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors increase the risk of pneumonitis compared to chemotherapy27, particularly in lung cancer patients13,28, which is consistent with our results. Signals associated with endocrine, hepatobiliary, immune, and respiratory system disorders were also prominent, especially endocrine and immune system. These findings align with the ADE profiles for ICIs in solid tumors12,29. Notably, irAEs remain the hallmark ADEs of ICIs30, often exhibiting relatively high signal strength (e.g., psoriatic arthropathy, immune-mediated liver dysfunction and pulmonary disease).

Specificities: D exhibited particularly significant pulmonary toxicity, notably radiation pneumonitis (n = 637, ROR025 = 51.49, IC025 = 4.18). The FDA has approved it for consolidative treatment after chemoradiotherapy in unresectable stage III NSCLC. Compared with chemoradiotherapy alone, the combined use of durvalumab increases the risk of radiation pneumonitis31,32. Radiation pneumonia and immune-related lung injury share common pathways, and is easy to induce lung infection33,34, which explains the significant pulmonary toxicity of D. A was unique in showing greater hematologic toxicity, such as febrile neutropenia, leukopenia, and myelosuppression. This is primarily observed when it is used in combination with chemotherapy. Studies show that A in combination with chemotherapy for treatment of lung cancer has higher risk of hematological adverse reactions of any grade14,35,36 or grade 3–437, consistent with this study.

The demographic analysis of ADE distribution across SOCs revealed considerable organ-specific differences by age and gender. These findings highlight the importance of considering demographic differences to better understand and mitigate the toxic burden of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Unlike most studies focusing solely on ADE incidence, this research systematically explored the timing of ADE onset. Findings showed that ADEs affected the skin, respiratory system or gastrointestinal tract earlier and the kidneys or endocrine systems later. These results align with previous studies38,39. However, this study only analyzed the timing of single ADEs and did not account for interactions between multiple ADEs, warranting further investigation.

Limitations

-

1.

The ADE frequency mentioned in the study only represents the proportion of ADE reports among all FAERS reports for a particular drug (reporting frequency) and does not represent true clinical incidence.

-

2.

Reporting biases may exist due to variability in the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare professionals responsible for submitting reports16.

-

3.

ROR and BCPNN cannot quantify the actual risk of ADEs or establish causality.

-

4.

A smaller sample size may lead to an overestimation of mortality rates, which could result in the misidentification of high mortality ADEs. We have provided a detailed list of high mortality ADEs in Table S7 for readers’ reference.

-

5.

The analysis of onset-timing was based solely on ADE reports with complete onset time information, the analysis of the timing of ADEs in each SOC was further limited to single-ADE reports, which introduces reporting bias. Furthermore, the above studies did not consider the severity of ADEs, so the analyses are preliminary.

Conclusion

Based on data from the FAERS database, this study systematically elucidates the ADE characteristics of four PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors from three perspectives: serious events, ADE frequency and strength, and ADE onset timing. The findings provide evidence for the future clinical application of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in lung cancer treatment.

Data availability

All data is publicly available in website of https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers-database.

Abbreviations

- A:

-

atezolizumab

- ADE(s):

-

Adverse drug event(s)

- BCPNN:

-

Bayesian Confidence Propagation Neural Network

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- D:

-

durvalumab

- FAERS:

-

FDA Adverse Event Reporting System

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- ICI(s):

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitor(s)

- IC025 :

-

Lower limit of the 95% confidence interval of information component

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- irAE(s):

-

immune-related adverse event(s)

- MedDRA:

-

Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities

- N:

-

nivolumab

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- OR(s):

-

Odds ratio(s)

- P:

-

pembrolizumab

- PS:

-

Primary suspect

- PT(s):

-

Preferred term(s)

- RCT(s):

-

Randomized Controlled Trial(s)

- ROR:

-

Reporting odds ratio

- ROR025 :

-

Lower limit of the 95% confidence interval of reporting odds ratios

- SCLC:

-

Small-cell lung cancer

- SOC(s):

-

System organ class(s)

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3), 209–249 (2021).

Bagchi, S., Yuan, R. & Engleman, E. G. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 16, 223–249 (2021).

Huang, Q. et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for patients with solid tumors: A systematic review and bayesian network Meta-analysis. J. Cancer. 12 (4), 1133–1143 (2021).

García Campelo, M. R. et al. PD-L1 Inhibitors as Monotherapy for the First-Line Treatment of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in PD-L1 Positive Patients: A Safety Data Network Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(19). (2021).

Botticelli, A. et al. Immune-related toxicity and soluble profile in patients affected by solid tumors: a network approach. Cancer Immunol. Immunotherapy: CII. 72 (7), 2217–2231 (2023).

Hoffner, B., Leighl, N. B. & Davies, M. Toxicity management with combination chemotherapy and programmed death 1/programmed death ligand 1 inhibitor therapy in advanced lung cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 85, 101979 (2020).

Puzanov, I. et al. Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the society for immunotherapy of cancer (SITC) toxicity management working group. J. Immunother. Cancer. 5 (1), 95 (2017).

Sherman, R. E. et al. Real-World Evidence - what is it and what can it tell us?? N. Engl. J. Med. 375 (23), 2293–2297 (2016).

Zhai, Y. et al. Endocrine toxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a real-world study leveraging US food and drug administration adverse events reporting system. J. Immunother. Cancer. 7 (1), 286 (2019).

Mota, J. M. et al. Pretreatment Eosinophil Counts in Patients With Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma Treated With Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Checkpoint Inhibitors. Journal of Immunotherapy (Hagerstown, Md.: 2021. 44(7): pp. 248–253. (1997).

Cui, C. et al. Respiratory system toxicity induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: A real-world study based on the FDA adverse event reporting system database. Front. Oncol. 12, 941079 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: an updated comprehensive disproportionality analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int. Immunopharmacol. 95, 107498 (2021).

Abdel-Rahman, O. Association between PD-L1 inhibitor, tumor site and adverse events of potential immune etiology within the US FDA adverse event reporting system. Immunotherapy 13 (17), 1407–1417 (2021).

Yang, F. et al. Patterns of toxicity burden for FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors in the united States. J. Experimental Clin. Cancer Research: CR. 42 (1), 4 (2023).

Guo, X. J. et al. Interstitial pneumonitis associated with combined regimen of immunotherapy and conventional therapies-pharmacovigilance database analysis with real-world data validation. BMC Med. 21 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02713-6 (2023).

Sakaeda, T. et al. Data mining of the public version of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int. J. Med. Sci. 10 (7), 796–803 (2013).

Sun, W. et al. Adverse event reporting of four anti-Calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies for migraine prevention: a real-world study based on the FDA adverse event reporting system. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1257282. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1257282 (2023).

Guan, Y. et al. Development of a drug risk analysis and assessment system and its application in signal excavation and analysis of 263 cases of fluoroquinolone-induced adverse reactions. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 892503 (2022).

Abedian Kalkhoran, H. et al. A text-mining approach to study the real-world effectiveness and potentially fatal immune-related adverse events of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in older patients with stage III/IV non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 23 (1), 247 (2023).

Clegg, A. et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet (London England). 381 (9868), 752–762 (2013).

Jin, J. et al. Male sex and pretreatment weight loss are associated with poor outcome in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with immunotherapy: a retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 17047 (2023).

Chan, J. M. et al. Signatures of plasticity, metastasis, and immunosuppression in an atlas of human small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 39(11), 1479–1496 (2021).

Duan, J. et al. Use of immunotherapy with programmed cell death 1 vs programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors in patients with cancer: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 6 (3), 375–384 (2020).

Sun, X. et al. Immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 and programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors for non-small cell lung cancer: a PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 19 (1), 558 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors for advanced non-small cell lung cancer with or without PD-L1 selection: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Chin. Med. J. 136 (18), 2156–2165 (2023).

Zhang, F. et al. Efficacy and safety of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors plus nab-paclitaxel for patients with non-small cell lung cancer who have progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy. Therapeutic Adv. Med. Oncol. 12, 1758835920936882 (2020).

Su, Q. et al. Risk of pneumonitis and pneumonia associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors for solid tumors: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 10, 108 (2019).

Nishino, M. et al. Incidence of programmed cell death 1 Inhibitor-Related pneumonitis in patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2 (12), 1607–1616 (2016).

Raschi, E. et al. Toxicities with immune checkpoint inhibitors: emerging priorities from disproportionality analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Target. Oncol. 14 (2), 205–221 (2019).

Tison, A. et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibitor use in patients with cancer and pre-existing autoimmune diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 18 (11), 641–656 (2022).

Shaverdian, N. et al. Radiation pneumonitis in lung cancer patients treated with chemoradiation plus durvalumab. Cancer Med. 9 (13), 4622–4631 (2020).

Jung, H. A. et al. Real world data of durvalumab consolidation after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer (Amsterdam Netherlands). 146, 23–29 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Crossed pathways for Radiation-Induced and Immunotherapy-Related lung injury. Front. Immunol. 12, 774807 (2021).

Mei, T. et al. Secondary infections after diagnosis of severe radiation pneumonitis (SRP) among patients with Non-Small cell lung cancer: pathogen distributions, choice of empirical antibiotics, and the value of empirical antifungal treatment. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 112 (1), 179–187 (2022).

Gürbüz, M. et al. Atezolizumab combined with chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: a real-life data of the Turkish oncology group. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 148 (12), 3547–3555 (2022).

Shiono, A. et al. Real-world data of Atezolizumab plus carboplatin and Etoposide in elderly patients with extensive-disease small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 12 (1), 73–83 (2023).

Lee, S. et al. Efficacy and safety of atezolizumab, in combination with Etoposide and carboplatin regimen, in the first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: a single-center experience. Cancer Immunol. Immunotherapy: CII. 71 (5), 1093–1101 (2022).

Tang, S. Q. et al. The pattern of time to onset and resolution of immune-Related adverse events caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer: A pooled analysis of 23 clinical trials and 8,436 patients. Cancer Res. Treat. 53 (2), 339–354 (2021).

Weber, J. S. et al. Safety profile of nivolumab monotherapy: A pooled analysis of patients with advanced melanoma. J. Clin. Oncology: Official J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 35 (7), 785–792 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who build and maintain FAERS database, and Chief Physician Qiu Li and Pharmacist-in-charge Hanrui Zheng in West China Hospital for their guidance in clinical interpretation.

Funding

This study was supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Grant Number: 2021YFS0091) and the 1⋅3⋅5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Grant Number: ZYAI24070).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design of the work: XY. Acquisition, transformation, verification, analysis or interpretation of data: CJ, YL, ZW, WH and XH. Drafting the article: CJ and YL. The manuscript was reviewed and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, C., Lai, Y., Wang, Z. et al. A study on adverse drug events of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in lung cancer treatment: a decade-long data mining. Sci Rep 15, 35744 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20157-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20157-9