Abstract

Neurological impairments resulting from bilirubin encephalopathy represent a hallmark of bilirubin’s neurotoxic effects. Earlier research suggests that bilirubin may contribute to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology by inducing neuronal necrosis and abnormal tau phosphorylation. Nevertheless, the precise mechanisms linking bilirubin to neurodegeneration in both neonates and adults remain unclear. To address this, we established two complementary models: a pathological jaundice model using UGT1A1⁻/⁻ neonatal mice and an adult bilirubin exposure model via lateral ventricle injection, followed by brain tissue sequencing. Integrating bioinformatics analyses with multiple AD datasets, we uncovered regulatory effects of bilirubin exposure on neurodegenerative processes across age groups. Machine learning approaches identified two key genes, BCL2-binding component 3 (Bbc3) and Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 10 (Map3k10), as central mediators of bilirubin-induced neuroinjury in pathological jaundice. In adults, bilirubin exposure also promoted neuroinflammation. Notably, effector memory CD8⁺ T cells emerged as critical drivers of AD-associated neuroinflammation, and four additional biomarkers were identified to construct a high-performance diagnostic model. Together, these findings highlight potential biomarkers for diagnosing and monitoring bilirubin-induced neurological damage and provide a basis for developing targeted diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

AD is a prevalent age-related neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive memory loss, cognitive decline, and impaired daily functioning, severely impacting quality of life1,2. Its pathogenesis involves the interplay of multiple pathways, such as amyloid-β (Aβ) accumulation, tau pathology, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and genetic predisposition, yet the core driver remains elusive3,4,5,6,7,8. Due to this multifactorial etiology, most current therapies provide only symptomatic relief without altering disease progression. The global burden of AD continues to rise, imposing profound personal, social, and economic consequences9. East Asia bears the highest absolute burden due to rapid population aging10,11with the total cost of AD in China projected to increase from US $248.71 billion in 2020 to US $1.89 trillion in 2050. Worldwide, the costs of dementia were estimated at US $957.56 billion in 2015 and are expected to reach US $9.12 trillion by 2050¹². In 2018, AD International estimated that ~ 50 million people were living with dementia globally, a number projected to triple by 2050124. Despite extensive research, the pathogenesis of AD remains contentious, necessitating further investigation into its mechanisms, the identification of novel biomarkers, and the improvement of diagnostic models to enhance intervention and treatment strategies.

Neuroinflammation is a recognized hallmark of AD and other neurodegenerative disorders13. The blood-brain barrier (BBB), choroid plexus, and meninges facilitate communication between the brain and the peripheral immune system14,15,16. Among these, the BBB is crucial for protecting neurons from systemic influences and maintaining central nervous system homeostasis. In AD patients, BBB integrity is compromised, leading to increased capillary permeability, degeneration of barrier-associated cells, and infiltration of circulating leukocytes and erythrocytes into the brain parenchyma14. Although the immune system’s involvement in AD pathogenesis is established, the precise role of immune cells and their genetic components in AD diagnosis remains unclear. Thus, identifying novel biomarkers and developing a more accurate diagnostic framework for AD are critical for early detection and improved patient outcomes.

Bilirubin, a byproduct of hemoglobin metabolism, possesses antioxidant properties but also exhibits immunomodulatory and neurotoxic effects17. Elevated serum bilirubin levels are observed in AD patients18. Under normal physiological conditions, bilirubin does not cause neurotoxicity; however, significant increases in bilirubin levels, as seen in pathological jaundice, can lead to neurotoxicity due to BBB disruption19,20. Clinical evidence indicates that neonatal hyperbilirubinemia increases the risk of bilirubin-induced neurological dysfunction21with severe cases potentially resulting in irreversible neurological damage22. Bilirubin encephalopathy refers to acute and chronic neurological dysfunctions associated with severe hyperbilirubinemia. Previous studies suggest that bilirubin-induced neurotoxicity may involve neuronal necrosis, tau protein hyperphosphorylation, increased Aβ production, and neuroinflammation23,24. Nonetheless, the molecular basis of bilirubin-induced neurodegeneration remains incompletely understood.

In this study, we applied integrated machine learning analyses to identify novel biomarkers associated with bilirubin-induced AD-like pathology in both neonatal and adult models. Our findings provide new insights into the pathophysiological functions of bilirubin and suggest potential diagnostic and therapeutic targets for AD.

Result

Pathological jaundice regulates multiple signaling pathways in the brain

Deletion of the UGT1A1 gene, essential for bilirubin metabolism, results in severe hyperbilirubinemia25. UGT1A1-deficient mice typically die within seven days of birth and exhibit pronounced signs of hyperbilirubinemia, such as jaundice, within 12 to 36 h postnatally26. Severe hyperbilirubinemia leads to bilirubin deposition in brain tissue, causing kernicterus. To investigate the effects of pathological jaundice on brain regulation, we sequenced various brain tissues from three-day-old suckling mice. Fig. S1A shows the differential gene expression across these tissues.

Gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses revealed significant differences in bilirubin regulation across the cerebral cortex, brainstem, cerebellum, hippocampus, and midbrain (Fig. 1A and B). GO-biological process (GO-BP) analysis indicated that the cerebral cortex and brainstem were associated with secondary metabolic processes, steroid metabolic processes, and chromosome segregation. Multiple immune-related pathways were enriched in the cerebellum and midbrain, whereas hippocampal tissues were enriched in mitochondrial processes and mitochondria-associated apoptosis. GO-cellular component (GO-CC) and GO-molecular function (GO-MF) analyses showed enrichment in various extracellular matrix-related pathways, such as collagen content and structural components conferring compressive resistance.

Although KEGG results varied among tissues, several infection-related pathways were enriched, including herpes simplex virus 1 infection, malaria, and human T-cell leukemia virus 1 infection. This implies that bilirubin may be involved in triggering brain inflammation. Additionally, pathways associated with neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD and Parkinson’s disease, were enriched in hippocampal tissues, suggesting that bilirubin may induce Alzheimer’s-like lesions by affecting hippocampal function.

Overall, our gene sequencing and assays in UGT1A1-deficient mice suggest that pathological jaundice regulates multiple signaling pathways in the brain.

Construction of weighted gene co-expression networks and identification of pathological jaundice-related modules

To identify module eigengenes (MEs) associated with pathological jaundice, we performed weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) on both our sequencing dataset and the GSE28146 dataset. The soft-threshold power was set to 12 for our dataset (Fig. 2A) and 7 for GSE28146 (scale-free R² = 0.85; Fig. S1B). In our dataset, three modules were strongly correlated with pathological jaundice: bisque4 (COR = 0.57, P = 0.001), turquoise (COR = 0.75, P = 3e-6), and ivory (COR = 0.52, P = 0.004) (Fig. 2B). In GSE28146, three modules were highly correlated with AD: saddlebrown, lightpink3, and turquoise (Fig. S1C). Scatterplots further confirmed strong correlations between gene significance (GS) and module membership (MM), including bisque4 (COR = 0.63, P = 6.5e-5), turquoise (COR = 0.83, P = 1e-200), and ivory (COR = 0.81, P = 4e-14) in our dataset (Fig. 2C), as well as saddlebrown (COR = 0.55, P = 2.7e-15), lightpink3 (COR = 0.47, P = 0.00044), and turquoise (COR = 0.52, P = 2.1e-92) in GSE28146 (Fig. S1D).

WGCNA identifies gene modules associated with pathological jaundice. (A) Scale-free network construction with soft-threshold power = 12 (scale-free R² = 0.85). (B) Module–trait heatmap showing correlations between gene modules, KO mice, and WT controls. Each cell displays the correlation coefficient and p-value. (C) Scatter plots of bisque4, turquoise, and ivory modules, showing strong positive correlations with KO mice. (D, E) KEGG enrichment analyses of genes from the bisque4, turquoise, and ivory modules.

To investigate the regulatory mechanisms implicated in pathological jaundice and AD, we performed KEGG clustering analysis on the gene modules from the self-assessment dataset and GSE28146. The results revealed a similarity in the KEGG clustering outcomes between the module strongly associated with pathological jaundice and the module highly linked to AD. Pathways such as autophagy, mitophagy, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) signaling pathway, pathways of neurodegeneration, and other signaling pathways exhibited significant enrichment in both datasets (Fig. 2D and S1E). Further examination of neurodegenerative disease and nervous system showed substantial enrichment of multiple pathways relevant to neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 2E), mirroring the findings in GSE28146 (Fig. S1F).

To delve deeper into the signaling pathways implicated in AD, we performed differential analysis on GSE5281, GSE37263, and hippocampal tissue datasets from GSE36980. Genes meeting the criteria of |logFC| > 0.5 and P-value < 0.05 were selected for KEGG pathway analysis. The results revealed significant enrichment of pathways linked to neurodegenerative disorders, including the pathways of neurodegeneration, within the context of AD (Fig. S1G).

These findings further suggest that pathological jaundice may contribute to the pathogenesis of neurological impairments by activating various pathways associated with neurodegenerative diseases.

Screening of hub genes for pathologic jaundice-induced nerve damage

Initially, a novel gene set was generated by amalgamating the AD, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Pathways of Neurodegeneration gene sets. This combined gene set was then cross-referenced with the key module genes from the WGCNA to identify shared genes, resulting in the identification of 84 intersecting genes (Fig. 3A). The Random Forest (RF) algorithm was subsequently employed to assess the relative importance of these 84 genes, focusing on the top 10 genes based on %IncMSE and IncNodePurity (Fig. 3B). Additionally, the support vector machine-recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE) algorithm was applied to these 84 candidate genes, leading to the identification of 5 core genes and the presentation of the top 5 hub genes (Fig. 3C). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was then conducted to determine the top 10 genes based on the area under the curve (AUC) for further examination. The results from the Random Forest, SVM-RFE, and ROC analyses were intersected, identifying BBC3 and MAP3K10 as common genes (Fig. 3D). The expression levels of BBC3 and MAP3K10 were elevated in the jaundice group compared to the control group (Fig. 3E). The ROC outcomes showed AUC values of 0.948 for BBC3 and 0.952 for MAP3K10, indicating their excellent diagnostic performance in pathological jaundice (Fig. 3F). This suggests that pathological jaundice might contribute to nerve damage by modulating the expression of BBC3 and MAP3K10, potentially triggering neurodegenerative conditions.

Identification of potential diagnostic biomarkers. (A) Venn diagram of candidate variables screened by KEGG gene sets and module genes. (B) Selection of diagnostic markers using the RF algorithm. (C) Selection of diagnostic markers using the SVM-RFE algorithm. (D) Venn diagram showing the overlap of variables identified by ROC, RF, and SVM-RFE analyses. (E, F) Expression levels and ROC curves of BBC3 and MAP3kK10. (G) Expression levels and ROC curves of BBC3 and MAP3K10 in the GSE15222 dataset. (H) KEGG pathway enrichment of candidate genes. (I) Correlation analysis between BBC3, MAP3K10, and enriched pathways.

We validated the expression of these genes in an additional AD-related dataset. This assay revealed a significant elevation in the expression levels of Bbc3 and Map3k10 in AD patients from the GSE15222 dataset compared to the control group (Fig. 3G). AUC values show that BBC3 and MAP3K10 also have some diagnostic values. Through Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) analysis, several pathways with differential expression were enriched, and they were shown in a heatmap. The Notch signaling pathway was significantly upregulated in both the hyperbilirubinemia group and AD patients (Fig. 3H). Meanwhile, we performed a correlation analysis examining the relationship between pathway and the genes of BBC3 and MAP3k10 (Fig. 3I). In both the hyperbilirubinemia model and the GSE15222 dataset, the expression of MAP3K10 showed a significant positive correlation with the Notch signaling pathway. Previous studies have demonstrated that excessive activation of the Notch signaling pathway is closely linked to amyloid-beta production and the onset of AD27–29.

In conclusion, our findings suggest a potential link between pathological jaundice and the initiation of neurological damage through the modulation of the Notch signaling pathway.

Bilirubin contributes to AD-like lesions in the brain by inducing neuroinflammation

Free bilirubin has been implicated in compromising BBB integrity by impairing glutathione function and increasing endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity via cytokine release19,20. Consequently, severe hyperbilirubinemia in adults may allow bilirubin infiltration into the brain. To investigate its neurological impact, we established a lateral ventricle injection model, which revealed activation of multiple immune-related signaling pathways in brain tissues following bilirubin exposure (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, KEGG enrichment analysis highlighted the significant enrichment of signaling pathways, such as the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signaling pathway, viral protein interaction with cytokine and cytokine receptor, and cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions in several tissues following bilirubin exposure (Fig. 4B). These pathways are recognized as fundamental components of the immune system, suggesting a potential role for bilirubin in neuroinflammatory responses.

Functional enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the lateral ventricle injection model and AD. (A, B) GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of DEGs across different brain regions. (C) KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs from datasets GSE29378, GSE53679, and GSE122063. (D) GSEA of datasets GSE29378 and GSE122063.

To extend these findings, we analyzed datasets GSE29378, GSE53697, and GSE122063 using the limma package (|logFC| > 0.5, P < 0.05). Consistent with our model, KEGG enrichment analysis showed significant enrichment of TNF signaling and cytokine-related pathways in AD patients (Fig. 4C). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) also confirmed activation of immune and innate immune pathways in AD (Fig. 4D).

Collectively, these findings suggest a potential involvement of bilirubin in the onset and progression of AD through the induction of neuroinflammation.

Construction of weighted gene co-expression networks and identification of AD-related modules

Next, we investigated the disparities in immune cell infiltration between individuals with AD and controls using single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA). We analyzed the distribution of 28 immune cells in the GSE122063 dataset (Fig. 5A). Subsequently, we utilized WGCNA to identify relevant modules potentially regulating AD and immune cells, with the soft threshold set at 6 (scale-free R2 = 0.85) (Fig. 5B). The heatmap in Fig. 5C displays the associations between these modules and related traits. Among these identified modules, grey60 (COR = 0.44, P = 8e-6), pink (COR = 0.52, P = 5e-8), tan (COR = 0.46, P = 2e-6), saddlebrown (COR = 0.53, P = 2e-8), and lightcyan (COR = 0.58, P = 5e-10) exhibited a pronounced positive correlation with AD. Further examination through scatterplot analysis revealed significant positive correlations between GS and MM for the grey60 module (COR = 0.63, P = 3.5e-25), pink module (COR = 0.61, P = 6.4e-78), tan module (COR = 0.61, P = 2e-41), saddlebrown module (COR = 0.53, P = 1.7e-8), and lightcyan module (COR = 0.77, P = 2.2e-46) (Fig. 5D).

WGCNA identifies AD- and immune cell–related gene modules. (A) (A) Proportions of 28 immune cell types in control and AD groups. (B) Scale-free network construction with soft-threshold power = 6 (scale-free R² = 0.85). ( C) Module–trait heatmap showing correlations between gene modules, AD, and immune cells. (D) Scatter plots of grey60, pink, tan, saddlebrown, and lightcyan modules, showing strong positive correlations with AD. (E, F) GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of module genes. (G) Correlation between GS and MM in activated dendritic cells, effector memory CD8⁺ T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, natural killer T cells, neutrophils, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells.

Subsequent GO and KEGG enrichment analyses conducted on genes within these modules indicated significant enrichment in leukocyte proliferation, adhesion, and major histocompatibility complex processes for GO analysis (Fig. 5E). Similarly, the KEGG pathway analysis showcased significant enrichment in signaling pathways, such as cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, viral protein interaction with cytokine and cytokine receptor, and TNF signaling pathway (Fig. 5F). These findings aligned with the outcomes from the lateral ventricle injection model we established.

Upon scrutinizing heatmaps illustrating the associations between modules and their respective traits, we discerned significant positive correlations of the grey60, pink, tan, saddlebrown, and lightcyan modules with various immune cells concurrently. Figure 5G depicts the correlation between GS and MM concerning activated dendritic cells, effector memory CD8+ T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, natural killer T cells, neutrophils, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Consequently, we postulate that these immune cells might play a role in neuroinflammatory processes and potentially trigger AD.

Identification of core immune cells in AD patients

To identify the key immune cells implicated in neuroinflammation, we utilized least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO), RF, and SVM-RFE algorithms for screening. Following a 10-fold cross-validation, the LASSO algorithm pinpointed 5 immune cells (Fig. 6A). The Random Forest algorithm subsequently assessed the relative importance of the 28 immune cells, selecting the top five based on %IncMSE and IncNodePurity for further scrutiny (Fig. 6B). Additionally, the SVM-RFE algorithm identified four immune cells, visually represented in Fig. 6C. Subsequent ROC analysis of these 28 immune cells led to the selection of the top 5 immune cells based on the AUC for more detailed investigation. By integrating findings from LASSO, Random Forest, SVM-RFE, and ROC analyses, we identified three core immune cells (Fig. 6D). Noteworthy were the AUC values for effector memory CD8+ T cells (0.873), effector memory CD4+ T cells (0.798), and immature B cells (0.872) (Fig. 6E).

Identification of core immune cells in AD patients. (A) Screening of diagnostic immune cells using the LASSO logistic regression algorithm. (B) Selection of diagnostic immune cells using the RF algorithm. (C) Diagnostic immune cells identified by the SVM-RFE algorithm. (D) Venn diagram showing overlap of immune cells identified by LASSO, RF, ROC, and SVM-RFE analyses. (E) ROC curves of effector memory CD8⁺ T cells, effector memory CD4⁺ T cells, and immature B cells.

By synthesizing the outcomes of WGCNA, we conclusively determined that effector memory CD8+ T cells are the central immune cells involved in neuroinflammation.

Screening hub genes by machine learning

We screened genes meeting the criteria of |logFC| ≥ 1 and P-value < 0.05, identifying 76 common genes by intersecting them with genes from the relevant module (Fig. 7A). Subsequently, LASSO, RF, and SVM-RFE methods were employed to further pinpoint core genes. LASSO regression identified a total of 12 genes (Fig. 7B). Concurrently, Fig. 7C displayed the screening outcomes of Random Forest, with genes co-occurring in the top 10 rankings of %IncMSE and IncNodePurity selected for detailed analysis. The SVM-RFE algorithm highlighted 57 key genes (Fig. 7D, left), with the top 10 genes ranked by importance (Fig. 7D, right). Integration of results from LASSO, RandomForest, and SVM-RFE analysis led to the identification of four core genes: complement component 4 (C4A), fibronectin type III and SPRY domain containing 2(FSD2), human leukocyte antigen- DR beta 4 chain (HLA-DRB4), and fc of igG binding protein (FCGBP) (Fig.7E). Analysis of their expression revealed significantly higher levels in AD compared to the normal group (Fig. 7F). Additionally, the areas under the ROC curves for C4A, FSD2, HLA-DRB4, and FCGBP were 0.951, 0.848, 0.826, and 0.91, respectively (Fig. 8A), suggesting their potential as valuable biomarkers.

Establishment of diagnostic models and identification of potential biomarkers. (A) Venn diagram of candidate variables identified from DEGs and module genes. (B) Screening of diagnostic markers using the LASSO logistic regression algorithm. (C) Selection of diagnostic markers using the RF algorithm. (D) Selection of diagnostic markers using the SVM-RFE algorithm. (E) Venn diagram showing the overlap of markers identified by LASSO, RF, and SVM-RFE. (F) Expression levels of C4A, FSD2, HLA-DRB4, and FCGBP.

Construction and validation of a nomogram model for AD diagnosis (A) ROC curves of C4A, FSD2, HLA-DRB4, and FCGBP. (B) Nomogram integrating diagnostic markers for AD; each variable corresponds to a score, and the total score is obtained by summing across variables. (C) ROC curve demonstrating the diagnostic performance of the nomogram. (D) Calibration curve assessing the predictive accuracy of the nomogram. (E) Decision curve analysis (DCA) evaluating the clinical utility of the nomogram. (F) Expression levels and ROC curves of C4A, FSD2, HLA-DRB4, and FCGBP in the GSE33000 dataset.

Utilizing the ‘rms’ R package, we constructed a nomogram for AD diagnosis based on the core genes C4A, FSD2, HLA-DRB4, and FCGBP (Fig. 8B). Subsequent ROC curve analysis of the nomogram yielded an AUC of 0.9987 (Fig. 8C), while the calibration curve indicated minimal deviation between actual AD risk and predicted risk, signifying the nomogram’s high predictive accuracy (Fig. 8D). Results from decision curve analysis (DCA) demonstrated the superior clinical benefits provided by the nomogram (Fig. 8E). In the validation set GSE33000, the expression levels of C4A, HLA-DRB4, and FCGBP were significantly elevated compared to the control group, and ROC curve analysis also demonstrated excellent diagnostic value. (Fig. 8F), further reinforcing their potential as diagnostic markers.

Additionally, we performed a correlation analysis examining the relationship between immune cells and the genes C4A, HLA-DRB4, and FCGBP (Fig. S3). This assay revealed a significant positive correlation between effector memory CD8+ T cells and C4A, FSD2, HLA-DRB4, and FCGBP, with C4A exhibiting the strongest correlation (COR = 0.76, P < 0.001), followed by FSD2 (COR = 0.54, P < 0.001), and FCGBP (COR = 0.54, P < 0.001).

Discussion

Hyperbilirubinemia is a commonly observed condition in newborns, typically physiological and resolving without intervention. However, significantly elevated bilirubin levels pose a risk of severe brain damage, leading to short- and long-term neurodevelopmental impairments and the potential development of acute or chronic bilirubin encephalopathy, known as kernicterus19,30. Kernicterus is characterized by the accumulation of bilirubin in the brain, though the precise pathogenesis and mechanisms of bilirubin-induced neuronal damage remain unclear.

In this study, we developed a model of neonatal pathological jaundice using UGT1A1 knockout mice. Our bioinformatics analysis revealed a significant resemblance between nerve injury induced by pathological jaundice and neurodegenerative diseases. We employed LASSO regression, random forest algorithm, and SVM-RFE to identify key genes associated with pathological jaundice-induced neurological damage, pinpointing BBC3 and MAP3K10 as crucial genes. The diagnostic accuracy of these biomarkers was evaluated using ROC curves.

Our data from neurodegenerative diseases showed a significant increase in the expression of BBC3 and MAP3K10 in patients with AD. BBC3 is a direct activator of BAX, playing a vital role in both p53-dependent and p53-independent apoptosis31,32,33. Additionally, BBC3 regulates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal apoptosis and is implicated in apoptosis regulation in the developing brain34,35,36. Multiple studies have shown that BBC3 is a key regulator of oxidative stress-induced BAX activation and neuronal apoptosis, suggesting that BBC3 may be a critical therapeutic target for neuroprotection37,38. BBC3 deficiency significantly protects neurons from ER-stress-induced apoptosis for neurodegenerative diseases39,40. MAP3K10, a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) family, regulates the MAPK signaling pathway, including the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) /p38MAPK and ERK pathways. MAPK pathway has been shown to regulate Notch signaling41. Dysregulation of neuronal cell signaling can lead to neurodegeneration and cognitive decline42,43. Pathway analysis results indicate that the Notch signaling pathway is activated in both hyperbilirubinemia models and AD patients. Notch signaling plays a critical role in neurogenesis during both embryonic and adult brain development, and is closely associated with synaptic remodeling, memory, and learning44,45,46,47. In AD patients, both Notch-1 and its target genes show significantly elevated expression, while Notch-1 signaling also interacts with amyloid beta production48. These findings collectively suggest a significant correlation between aberrant Notch signaling and Alzheimer’s disease.

Our findings suggest that pathological jaundice may disrupt the Notch signaling pathway by influencing BBC3 and MAP3K10 expression, potentially leading to neuronal cell apoptosis and contributing to the development of nuclear jaundice.

Maintaining blood-brain barrier integrity is crucial to prevent the entry of macromolecules, including bilirubin, into the brain, thereby maintaining brain homeostasis49. Free bilirubin can compromise BBB integrity by interfering with glutathione19,20. Conditions, such as autoimmune hemolytic anemia, drug-induced states, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency typically result in unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in adults50.

In our investigation of the potential pathogenesis of AD, we analyzed various AD-related sequencing data, revealing significant activation of signaling pathways such as neuroactive ligand-receptor interactions, cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, and viral protein interactions with cytokines and cytokine receptors in AD patients. GSEA indicated an upregulation of the immune system, suggesting that neuroinflammation may play a significant role in AD induction. We simulated adult bilirubin exposure by injecting bilirubin into the lateral ventricle. Bioinformatics analysis demonstrated that bilirubin treatment markedly activated signaling pathways, including cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction and viral protein interaction with cytokine and cytokine receptor. Bilirubin-induced neuroinflammation has been reported in multiple studies51,52,53,54. In rat models of bilirubin encephalopathy, bilirubin excessively activates microglia, leading to upregulated expression of MHCII, CCL2, IL-6, TNF-a, and IL-1b, along with downregulated IL-10 levels, thereby triggering inflammation in the hippocampus52,55,56. Consequently, adult bilirubin exposure may contribute to the initiation of neuroinflammation.

Numerous studies have shown the role of neuroinflammation in AD initiation and progression. Increased levels of inflammatory mediators have been documented in the cerebral tissues of AD patients, indicating a significant role of bilirubin in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, specifically AD57.

Neuroinflammation is a key feature of several neurodegenerative diseases, particularly in the pathogenesis and progression of AD58. It is typically initiated by microglial activation59,60. As the resident immune cells of the central nervous system (CNS), microglia coordinate innate immune responses within the brain and interact with peripheral immunity through the BBB. Under physiological conditions, the BBB protects the CNS by regulating the passage of neurotoxins and serum factors via specialized tight junctions and transport proteins61. In AD, BBB disruption has been reported in multiple regions, including the hippocampus, gray matter, and white matter62,63,64,65and may occur at early stages of disease progression62,66,67. Evidence of plasma extravasation, peripheral macrophage infiltration, and neutrophil infiltration in AD brain tissue further supports a role for immune infiltration in disease development68,69,70,71. Analysis of the GSE122063 data indicates that effector memory CD8+ T cells, effector memory CD4+ T cells, and immature B cells may contribute to neuroinflammation. Coupled with the results of WGCNA, it is suggested that effector memory CD8+ T cells are significant immune cells involved in AD. Other studies also demonstrated that effector memory CD8+ T cells participate in AD through their proinflammatory and cytotoxic functions72.

We employed various machine learning techniques to identify key genes associated with neuroinflammation. C4A, FSD2, HLA-DRB4, and FCGBP were identified as hub gene. The analysis of ROC curves indicated that these genes could serve as novel potential diagnostic markers for neuroinflammatory AD. Based on these genes, we developed a diagnostic model for AD, which demonstrated good accuracy through validation with calibration curves and decision curves.

C4A, a component of the classical complement pathway, is a marker of inflammation, and associated with an increased risk of schizophrenia. Overexpression of C4A promotes excessive synaptic loss and behavioral changes in mice73. Elevated expression of C4A in AD patients, potentially related to disease pathogenesis74,75. The FCGBP gene encodes an IgG Fc-binding protein crucial for immune and inflammatory processes, including the regulation of immune protection and inflammation in the gut76. Abnormalities in gut microbes may trigger mucosal immune activation, leading to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration77,78. FCGBP might play a crucial role in both intestinal and brain inflammation, potentially contributing to neurodegenerative processes79. While no studies have yet reported on HLA-DRB4 and FSD2 in AD, further experimental confirmation of their functions is necessary. Nonetheless, our analysis suggests that these key genes may serve as potential diagnostic markers for AD.

While this study provides important insights, several limitations should be noted. First, the inclusion of multiple tissue types (cerebral cortex, hippocampus, midbrain, cerebellum, and brainstem) may introduce bias. Future studies integrating larger numbers of samples from the same tissue type will improve detection power and robustness. Second, as our analyses were primarily bioinformatics-based, further validation using clinical data and experimental models is required to confirm these findings. Finally, although autophagy and neuroinflammation in AD have been widely studied, the six genes highlighted here remain relatively unexplored in the context of AD, and their functional roles warrant further experimental investigation.

Material and method

Graphical abstract

To analyze the hub genes of AD, we designed a flowchart. The workflow of the analysis is shown in Fig. 9.

Animals and injections

UGT1A1-/- mice were generated by mating heterozygous UGT1A1+/- mice. Littermate wild-type (WT) mice served as controls (n = 3 per group). On postnatal day 3, UGT1A1-/- and WT mice were euthanized, and brains were immediately harvested into ice-cold PBS (4 °C). The hippocampus, cerebral cortex, midbrain, brainstem, and cerebellum were dissected, transferred to RNAlater, and stored at − 80 °C. Mice were maintained under a 12 h light/dark cycle with ad libitum food and water. All procedures followed the ARRIVE guidelines and the regulations of the Guangzhou Medical University Animal Experimentation Committee, with ethical approval (NO. GY2022-020).

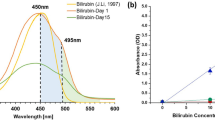

Male C57BL/6J mice (6 weeks old; Jiangsu GemPharmatech Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were randomly assigned to two groups (n = 3 per group). Bilirubin was administered by stereotaxic injection into the lateral ventricle. Mice were anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate (5 mL/g) and secured in a stereotaxic apparatus. Coordinates were AP = − 0.5 mm, ML = − 1.0 mm, DV = − 2.5 mm. Based on cerebrospinal fluid volume in mice (~ 35 µL)80, 560 nL of bilirubin solution (50 µM) was injected at a rate of 4 nL/s, with the needle left in place for 10 min post-injection. Bilirubin was prepared as described previously24: bilirubin (100 mg; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was dissolved in 0.5 M NaOH (1 mL), diluted in ddH₂O to 10 mg/mL, and pH-adjusted to 8.5 with 0.5 M HCl. For injections, the solution was further diluted to 3.175 mM.

Twelve hours post-injection, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused transcardially with pre-cooled PBS until blood-free. Brains were rapidly removed, and the hippocampus, cerebral cortex, midbrain, brainstem, and cerebellum were dissected on ice, placed in RNAlater, and stored at − 80 °C.

RNA extraction and library preparation

Total RNA was extracted from tissue samples (20–50 mg) using 1 mL TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen™, cat. no. 15596018) followed by mechanical homogenization at low temperature with a Tissuelyser-24. For RNA purification, 0.2 mL chloroform was added per 1 mL TRIzol-lysate, vortexed for 15 s, incubated at room temperature for 5 min, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube, and RNA was precipitated with isopropanol. For cell samples, RNA was extracted directly using the phenol–chloroform method.

mRNA was captured and purified using Epi™ mRNA Capture Beads (Epibiotek, cat. no. R2020-96), and libraries were constructed with the Epi™ mRNA Library Fast Kit (Epibiotek, cat. no. R1810). Final libraries were purified with Epi™ DNA Clean Beads (Epibiotek, cat. no. R1809). Library quality was assessed on a Bioptic Qsep100 Analyzer to confirm fragment size distribution within the expected range.

RNA-seq

RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the VAHTS Stranded mRNA-seq Library Prep Kit for Illumina V2 (Vazyme Biotech, NR612-02) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing reads were aligned to the mouse Ensembl genome (GRCm38) using HISAT2 (v2.1.0) with the parameter --rna-strandness RF. Read counts mapped to the genome were quantified using featureCounts (v1.6.3). Differential gene expression analysis was performed with the DESeq2 R package.

Data downloads and pre-processing

We extracted the gene expression profiles of AD (GSE29378, GSE53697, GSE122063, GSE33000, GSE28146, GSE37263, GSE5281 and GSE36980) from the GEO database using the GEOquery package (v2.70.0)81.

GSE series | AD | Control |

|---|---|---|

GSE29378 | 31 | 32 |

GSE53697 | 9 | 8 |

GSE122063 | 56 | 44 |

GSE33000 | 310 | 157 |

GSE28146 | 8 | 22 |

GSE37263 | 8 | 8 |

GSE5281 | 87 | 74 |

GSE36980 | 8 | 10 |

Gene co-expression analysis

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was performed using the WGCNA R package (v1.72-5) to identify gene modules, determine hub genes, and assess module–phenotype relationships82. The optimal soft-threshold power was selected using the pickSoftThreshold function, and the most relevant modules associated with pathological jaundice, AD, and immune cell populations were identified for downstream analysis.

Screening of DEGs

To further assess gene expression differences between groups, differential expression analysis was performed using the limma package83. Genes with P < 0.05 and |log₂FC| > 0.5 (or > 1, where specified) were considered differentially expressed. Results were visualized using volcano plots.

Functional enrichment analysis

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of DEGs and module genes were performed using the clusterProfiler R package (v4.10.0) 84. GO analysis was conducted for biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), and cellular components (CC), while KEGG analysis was used to identify enriched pathways. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

GSVA

GSVA is a nonparametric, unsupervised method used to assess gene set enrichment in microarray or RNA-seq data85. KEGG gene sets were obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database. Normalized enrichment scores were calculated using the GSVA and GSEABase packages86. Differential pathway activity between the pediatric sepsis and control groups was identified using the limma package. Pathways with P < 0.05 were considered significant and ranked by log₂|FC|.

Evaluation of subtype distribution among immune-infiltrated cells

We assessed the immunological characteristics of each sample using ssGSEA, an extension of the GSEA method widely applied in immune infiltration studies87. The GSVA, GSEABase, and limma packages were used to estimate the abundance of 28 immune cell types in each tissue85,88based on immune cell gene sets derived from published literature89. Pearson’s correlation analysis was then applied to evaluate the associations between hub genes and immune cell populations.

Machine learning screening of hub immune cells and hub gene

Three machine learning algorithms, RF90, LASSO91and SVM-RFE92,93were applied to identify key immune cells and candidate genes associated with bilirubin and AD diagnosis. RF is an ensemble method capable of handling numerous input variables while evaluating their relative importance. LASSO is a regression approach well suited for high-dimensional data. SVM-RFE classifies data by constructing hyperplanes and employs regularization to reduce overfitting. Genes consistently selected across all three algorithms were defined as hub genes.

ROC curves of hub genes

The logistic regression model of hub genes was constructed using glm function in R software, and the ROC curves were plotted using R package pROC (v1.18.5). The ROC curve helps us determine whether the model has diagnostic value. The AUC is used to determine predictive accuracy.

Column chart construction and diagnostic effectiveness assessment

A diagnostic model for predicting AD incidence was constructed using logistic regression and visualized as a nomogram94. Model performance was evaluated by calibration curves (accuracy) and decision curve analysis (clinical utility). Finally, biomarker expression and model performance were validated in an independent dataset.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed in R (v4.3.2). Differences between two groups were assessed using either the Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Student’s t-test. Correlations between variables were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus, the primary accession code GSE29378,GSE53697,GSE122063,GSE33000,GSE28146,GSE37263,GSE5281,GSE36980.

Abbreviations

- Aβ:

-

Amyloid-β (Aβ)

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- BBB:

-

Blood-brain barrier

- Bbc3:

-

BCL2-binding component 3

- C4A:

-

Complement component 4

- cAMP:

-

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- DCA:

-

Decision curve analysis

- DEG:

-

Differential gene expression

- FCGBP:

-

Fc of igG binding protein

- FSD2:

-

Fibronectin type III and SPRY domain containing 2

- GSEA:

-

Gene set enrichment analysis

- GSVA:

-

Gene set variation analysis

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- GS:

-

Gene significance

- HLA-DRB4:

-

Human leukocyte antigen- DR beta 4 chain

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- KO:

-

Knock out

- LASSO:

-

Least absolute shrinkage selection

- Map3k10:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 10

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEs:

-

Module eigengenes

- MM:

-

Module membership

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- RF:

-

Random forest

- SVM-RFE:

-

Support vector machine recursive feature elimination

- ssGSEA:

-

Single-sample gene set enrichment analysis

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- UGT1A1:

-

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1

- WGCNA:

-

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

References

Kukull, W. A. & Bowen, J. D. Dementia epidemiology. Med. Clin. North. Am. 86, 573–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0025-7125(02)00010-x (2002).

Yan, Y. et al. Research progress on alzheimer’s disease and Resveratrol. Neurochem Res. 45, 989–1006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-020-03007-0 (2020).

Jucker, M. & Walker, L. C. Alzheimer’s disease: from immunotherapy to Immunoprevention. Cell 186, 4260–4270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.021 (2023).

Scheltens, P. et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 397, 1577–1590. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32205-4 (2021).

Bai, R., Guo, J., Ye, X. Y., Xie, Y. & Xie, T. Oxidative stress: the core pathogenesis and mechanism of alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 77, 101619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2022.101619 (2022).

Si, Z. Z. et al. Targeting neuroinflammation in alzheimer’s disease: from mechanisms to clinical applications. Neural Regen Res. 18, 708–715. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.353484 (2023).

Zhao, J. et al. Brain 5-hydroxymethylcytosine alterations are associated with alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Nat. Commun. 16, 2842. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58159-w (2025).

Course, M. M. et al. Aberrant splicing of PSEN2, but not PSEN1, in individuals with sporadic alzheimer’s disease. Brain 146, 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac294 (2023).

Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 19, 1598–1695 (2023). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13016

Li, X. et al. Global, regional, and National burden of alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2019. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 937486. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.937486 (2022).

Hao, M. & Chen, J. Trend analysis and future predictions of global burden of alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: a study based on the global burden of disease database from 1990 to 2021. BMC Med. 23, 378. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-025-04169-w (2025).

Jia, J. et al. The cost of alzheimer’s disease in China and re-estimation of costs worldwide. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2017.12.006 (2018).

Jorfi, M., Maaser-Hecker, A. & Tanzi, R. E. The neuroimmune axis of alzheimer’s disease. Genome Med. 15, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-023-01155-w (2023).

Sweeney, M. D., Sagare, A. P. & Zlokovic, B. V. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14, 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.188 (2018).

Shechter, R. et al. Recruitment of beneficial M2 macrophages to injured spinal cord is orchestrated by remote brain choroid plexus. Immunity 38, 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.012 (2013).

Dani, N. et al. A cellular and Spatial map of the choroid plexus across brain ventricles and ages. Cell 184, 3056–3074e3021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.003 (2021).

Wen, G., Yao, L., Hao, Y., Wang, J. & Liu, J. Bilirubin ameliorates murine atherosclerosis through inhibiting cholesterol synthesis and reshaping the immune system. J. Transl Med. 20, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-021-03207-4 (2022).

Zhong, X. et al. Abnormal serum bilirubin/albumin concentrations in dementia patients with Aβ deposition and the benefit of intravenous albumin infusion for alzheimer’s disease treatment. Front. Neurosci. 14, 859. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00859 (2020).

Brites, D. The evolving landscape of neurotoxicity by unconjugated bilirubin: role of glial cells and inflammation. Front. Pharmacol. 3, 88. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2012.00088 (2012).

Palmela, I. et al. Elevated levels of bilirubin and long-term exposure impair human brain microvascular endothelial cell integrity. Curr. Neurovasc Res. 8, 153–169. https://doi.org/10.2174/156720211795495358 (2011).

Ahlfors, C. E., Bhutani, V. K., Wong, R. J. & Stevenson, D. K. Bilirubin binding in jaundiced newborns: from bench to bedside? Pediatr. Res. 84, 494–498. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-018-0010-3 (2018).

Johnson, L. & Bhutani, V. K. The clinical syndrome of bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction. Semin Perinatol. 35, 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2011.02.003 (2011).

Cayabyab, R. & Ramanathan, R. High unbound bilirubin for age: a neurotoxin with major effects on the developing brain. Pediatr. Res. 85, 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-018-0224-4 (2019).

Chen, H. et al. Short term exposure to bilirubin induces encephalopathy similar to alzheimer’s disease in late life. J. Alzheimers Dis. 73, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-190945 (2020).

Fujiwara, R., Nguyen, N., Chen, S. & Tukey, R. H. Developmental hyperbilirubinemia and CNS toxicity in mice humanized with the UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1 (UGT1) locus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107, 5024–5029. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0913290107 (2010).

Bortolussi, G. et al. Impairment of enzymatic antioxidant defenses is associated with bilirubin-induced neuronal cell death in the cerebellum of Ugt1 KO mice. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1739. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2015.113 (2015).

Nagarsheth, M. H., Viehman, A., Lippa, S. M. & Lippa, C. F. Notch-1 Immunoexpression is increased in alzheimer’s and pick’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 244, 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2006.01.007 (2006).

Fischer, D. F. et al. Activation of the Notch pathway in down syndrome: cross-talk of Notch and APP. Faseb J. 19, 1451–1458. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.04-3395.com (2005).

Oh, S. Y. et al. Amyloid precursor protein interacts with Notch receptors. J. Neurosci. Res. 82, 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.20625 (2005).

Shapiro, S. M. Definition of the clinical spectrum of Kernicterus and bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction (BIND). J. Perinatol. 25, 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211157 (2005).

Ren, D. et al. BID, BIM, and PUMA are essential for activation of the BAX- and BAK-dependent cell death program. Sci. (New York N Y). 330, 1390–1393. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1190217 (2010).

Yu, J., Zhang, L., Hwang, P. M., Kinzler, K. W. & Vogelstein, B. PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol. Cell. 7, 673–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00213-1 (2001).

Follis, A. V. et al. PUMA binding induces partial unfolding within BCL-xL to disrupt p53 binding and promote apoptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.1166 (2013).

Galehdar, Z. et al. Neuronal apoptosis induced by Endoplasmic reticulum stress is regulated by ATF4-CHOP-mediated induction of the Bcl-2 homology 3-only member PUMA. J. Neurosci. 30, 16938–16948. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1598-10.2010 (2010).

Ghosh, A. P., Klocke, B. J., Ballestas, M. E. & Roth, K. A. CHOP potentially co-operates with FOXO3a in neuronal cells to regulate PUMA and BIM expression in response to ER stress. PLoS One. 7, e39586. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039586 (2012).

Harder, J. M. & Libby, R. T. BBC3 (PUMA) regulates developmental apoptosis but not axonal injury induced death in the retina. Mol. Neurodegener. 6, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1326-6-50 (2011).

Steckley, D. et al. Puma is a dominant regulator of oxidative stress induced Bax activation and neuronal apoptosis. J. Neurosci. 27, 12989–12999. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3400-07.2007 (2007).

Gomez-Lazaro, M. et al. 6-Hydroxydopamine activates the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway through p38 MAPK-mediated, p53-independent activation of Bax and PUMA. J. Neurochem. 104, 1599–1612. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05115.x (2008).

Li, M. The role of P53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) in ovarian development, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Apoptosis 26, 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10495-021-01667-z (2021).

Kieran, D., Woods, I., Villunger, A., Strasser, A. & Prehn, J. H. Deletion of the BH3-only protein Puma protects motoneurons from ER stress-induced apoptosis and delays motoneuron loss in ALS mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 104, 20606–20611. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707906105 (2007).

Zeng, Q. et al. Crosstalk between tumor and endothelial cells promotes tumor angiogenesis by MAPK activation of Notch signaling. Cancer Cell. 8, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.004 (2005).

Kumari, S., Dhapola, R. & Reddy, D. H. Apoptosis in alzheimer’s disease: insight into the signaling pathways and therapeutic avenues. Apoptosis 28, 943–957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10495-023-01848-y (2023).

Jadiya, P., Garbincius, J. F. & Elrod, J. W. Reappraisal of metabolic dysfunction in neurodegeneration: focus on mitochondrial function and calcium signaling. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 9, 124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-021-01224-4 (2021).

Chambers, C. B. et al. Spatiotemporal selectivity of response to Notch1 signals in mammalian forebrain precursors. Development 128, 689–702. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.128.5.689 (2001).

Hitoshi, S. et al. Notch pathway molecules are essential for the maintenance, but not the generation, of mammalian neural stem cells. Genes Dev. 16, 846–858. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.975202 (2002).

Sestan, N., Artavanis-Tsakonas, S. & Rakic, P. Contact-dependent Inhibition of cortical neurite growth mediated by Notch signaling. Science 286, 741–746. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.286.5440.741 (1999).

Costa, R. M., Honjo, T. & Silva, A. J. Learning and memory deficits in Notch mutant mice. Curr. Biol. 13, 1348–1354. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00492-5 (2003).

Lathia, J. D., Mattson, M. P. & Cheng, A. Notch: from neural development to neurological disorders. J. Neurochem. 107, 1471–1481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05715.x (2008).

Abbott, N. J., Patabendige, A. A., Dolman, D. E., Yusof, S. R. & Begley, D. J. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol. Dis. 37, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.030 (2010).

Winger, J. & Michelfelder, A. Diagnostic approach to the patient with jaundice. Prim. Care. 38, 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2011.05.004 (2011). viii.

Schiavon, E., Smalley, J. L., Newton, S., Greig, N. H. & Forsythe, I. D. Neuroinflammation and ER-stress are key mechanisms of acute bilirubin toxicity and hearing loss in a mouse model. PLoS One. 13, e0201022. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201022 (2018).

Ercan, I. et al. Bilirubin induces microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 125, 103850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcn.2023.103850 (2023).

Vodret, S. et al. Attenuation of neuro-inflammation improves survival and neurodegeneration in a mouse model of severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. Brain Behav. Immun. 70, 166–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2018.02.011 (2018).

Vodret, S., Bortolussi, G., Jašprová, J., Vitek, L. & Muro, A. F. Inflammatory signature of cerebellar neurodegeneration during neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in Ugt1 (-/-) mouse model. J. Neuroinflammation. 14, 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-017-0838-1 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. Inhibition of microglial activation ameliorates inflammation, reduced neurogenesis in the hippocampus, and impaired brain function in a rat model of bilirubin encephalopathy. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 19, 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-024-10124-y (2024).

Vaz, A. R., Falcão, A. S., Scarpa, E., Semproni, C. & Brites, D. Microglia susceptibility to free bilirubin is Age-Dependent. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 1012. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.01012 (2020).

Ng, A. et al. IL-1β, IL-6, TNF- α and CRP in elderly patients with depression or alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 8, 12050. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30487-6 (2018).

Rajesh, Y. & Kanneganti, T. D. Innate Immune Cell Death in Neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11121885 (2022).

Hossain, M. S. et al. Reduction of Ether-Type glycerophospholipids, plasmalogens, by NF-κB signal leading to microglial activation. J. Neurosci. 37, 4074–4092. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3941-15.2017 (2017).

Zhao, J. et al. Neuroinflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide causes cognitive impairment in mice. Sci. Rep. 9, 5790. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42286-8 (2019).

Schaeffer, S. & Iadecola, C. Revisiting the neurovascular unit. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 1198–1209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-021-00904-7 (2021).

Montagne, A. et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in the aging human hippocampus. Neuron 85, 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.032 (2015).

Montagne, A. et al. Brain imaging of neurovascular dysfunction in alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 131, 687–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1570-0 (2016).

van de Haar, H. J. et al. Blood-Brain barrier leakage in patients with early alzheimer disease. Radiology 281, 527–535. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2016152244 (2016).

van de Haar, H. J. et al. Subtle blood-brain barrier leakage rate and Spatial extent: considerations for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Med. Phys. 44, 4112–4125. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.12328 (2017).

Whitwell, J. L. et al. Neuroimaging correlates of pathologically defined subtypes of alzheimer’s disease: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 11, 868–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(12)70200-4 (2012).

Apostolova, L. G. et al. Subregional hippocampal atrophy predicts alzheimer’s dementia in the cognitively normal. Neurobiol. Aging. 31, 1077–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.08.008 (2010).

Cullen, K. M., Kócsi, Z. & Stone, J. Pericapillary haem-rich deposits: evidence for microhaemorrhages in aging human cerebral cortex. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 25, 1656–1667. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600155 (2005).

Hultman, K., Strickland, S. & Norris, E. H. The APOE ɛ4/ɛ4 genotype potentiates vascular fibrin(ogen) deposition in amyloid-laden vessels in the brains of alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 33, 1251–1258. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2013.76 (2013).

Zenaro, E. et al. Neutrophils promote alzheimer’s disease-like pathology and cognitive decline via LFA-1 integrin. Nat. Med. 21, 880–886. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3913 (2015).

Fiala, M. et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-positive macrophages infiltrate the alzheimer’s disease brain and damage the blood-brain barrier. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 32, 360–371. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2362.2002.00994.x (2002).

Gate, D. et al. Clonally expanded CD8 T cells patrol the cerebrospinal fluid in alzheimer’s disease. Nature 577, 399–404. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1895-7 (2020).

Yilmaz, M. et al. Overexpression of schizophrenia susceptibility factor human complement C4A promotes excessive synaptic loss and behavioral changes in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 214–224. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-00763-8 (2021).

Zorzetto, M. et al. Complement C4A and C4B gene copy number study in alzheimer’s disease patients. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 14, 303–308. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205013666161013091934 (2017).

Khan, A. T., Dobson, R. J., Sattlecker, M. & Kiddle, S. J. Alzheimer’s disease: are blood and brain markers related? A systematic review. Ann. Clin. Transl Neurol. 3, 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.313 (2016).

Harada, N. et al. Human IgGFc binding protein (FcgammaBP) in colonic epithelial cells exhibits mucin-like structure. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 15232–15241. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.24.15232 (1997).

Perez-Pardo, P. et al. Role of TLR4 in the gut-brain axis in parkinson’s disease: a translational study from men to mice. Gut 68, 829–843. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316844 (2019).

Sampson, T. R. et al. Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell 167, 1469–1480.e1412 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.018

Gómez-Garre, P. et al. Transcriptomic analysis reveals an association of FCGBP with parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 8, 157. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-022-00415-7 (2022).

Pardridge, W. M. CSF, blood-brain barrier, and brain drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 13, 963–975. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425247.2016.1171315 (2016).

Davis, S. & Meltzer, P. S. GEOquery: a Bridge between the gene expression omnibus (GEO) and bioconductor. Bioinformatics 23, 1846–1847. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm254 (2007).

Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 9, 559. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-559 (2008).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv007 (2015).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics 16, 284–287. https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2011.0118 (2012).

Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 14, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-7 (2013).

Liberzon, A. et al. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics 27, 1739–1740. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr260 (2011).

Barbie, D. A. et al. Systematic RNA interference reveals that oncogenic KRAS-driven cancers require TBK1. Nature 462, 108–112. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08460 (2009).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102, 15545–15550. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0506580102 (2005).

Charoentong, P. et al. Pan-cancer Immunogenomic analyses reveal Genotype-Immunophenotype relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint Blockade. Cell. Rep. 18, 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.019 (2017).

Newman, A. M. et al. Determining cell type abundance and expression from bulk tissues with digital cytometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 773–782. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0114-2 (2019).

Liberzon, A. et al. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell. Syst. 1, 417–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004 (2015).

Guyon, I., Weston, J., Barnhill, S. & Vapnik, V. Gene selection for cancer classification using support vector machines. Mach. Learn. 46, 389–422. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012487302797 (2002).

Lin, X. et al. Selecting feature subsets based on SVM-RFE and the overlapping ratio with applications in bioinformatics. Molecules 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23010052 (2017).

Iasonos, A., Schrag, D., Raj, G. V. & Panageas, K. S. How to build and interpret a nomogram for cancer prognosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 1364–1370. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.12.9791 (2008).

Funding

This work received support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 82370067) and the open research funds from the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Qingyuan People’s Hospital (grant No. 202011-106).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L designed the study and revised the manuscript. W.B and H.C performed all the experiments and analyzed all the data and wrote the manuscript. Z.Z., J.L. and J.W. participated part of research. D.T reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Experimental Animal Welfare, Guangzhou Medical University, and performed according to the Guide for the National Science Council of the Republic of China.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, W., Chen, H., Zhang, Z. et al. Integrated machine learning identifies biomarkers for bilirubin-induced Alzheimer’s disease-like lesions in neonates and adults. Sci Rep 15, 36214 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20235-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20235-y