Abstract

Although pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) have greatly reduced diseases caused by vaccine-targeted serotypes (VT) of Streptococcus pneumoniae, vaccine impact may be eroded by the increase in rates of disease caused by non-vaccine serotypes (NVT). Here, we investigated the effect of social contact patterns on the dynamics of vaccine impact in carriage. We developed a neutral, age-structured, Susceptible–Colonized model incorporating VT-NVT co-colonization and verified it against real-world carriage data in children. Using social contact matrices from 34 countries, we assessed the impact of contact patterns on the time required to eliminate VT in a given age group (defined here as the time needed for the relative proportion of VT in overall carriage to drop by 95% after the introduction of vaccination). Finally, we quantified the contribution of various parameters—such as vaccine efficacy, coverage, immunity waning, and population susceptibility—to the dynamics of VT elimination. Our model recapitulated the observed decline of VT carriage and showed that varying the contact structure alone led to different time-to-elimination (3.8–6 years). We found that higher total contact rate and assortativity in children under 5 accelerated VT elimination. Additionally, higher vaccine efficacy and coverage, and slower immunity waning led to shorter time-to-elimination. These findings illuminate the mechanisms controlling the dynamics of vaccine impact and may help predict the impact of PCVs in communities with different contact patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae is one of the five leading pathogens for the estimated 7.7 million bacteria-associated deaths globally1. The first several generations of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) have reduced invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) substantially in all age groups2. However, the reduction in rates of disease caused by vaccine-targeted serotypes of pneumococci (VT) was partially offset by an increase in rates of disease caused by non-vaccine-targeted serotypes (NVT)3,4. This phenomenon, known as “serotype replacement”, occurred because PCVs targeted a subset of over 100 identified serotypes5,6, reducing the fitness of VT and changing the competitive balance between VT and NVT7,8. Nasopharyngeal carriage is a prerequisite for pneumococcal diseases, and the reduction in carriage in immunized children leads to indirect protection of unvaccinated children and adults9. Likewise, serotype replacement in carriage may erode the population-level impact of PCVs and thus demands public health attention.

Observed serotype replacement in diseases was initially more pronounced in the UK than in the US, for which multiple possible explanations have been suggested: the distribution of risk factors, the vaccination schedule and coverage, and the pre-PCV composition of circulating serotypes10. While replacement in diseases is partial, replacement in carriage is almost complete, and it occurs faster in some populations than others3,11,12. However, the mechanisms driving such variation remain unclear. One potential determinant for the serotype replacement dynamics is the social contact structure in a population. Carriage studies have shown that social contact with preschool-age children is associated with higher prevalence of pneumococcal carriage13,14. While social contact structures are thought to be major drivers of infectious disease dynamics15, there have not been studies investigating the effect of social contact structure on the dynamics of vaccine impact in pneumococcal carriage. Addressing this knowledge gap can elucidate the potential mechanisms controlling the dynamics of vaccine impact and serotype replacement and may help predict the impact of the higher-valency PCVs in communities with different contact patterns.

In this study, we developed a mathematical model parameterized with empirical data to simulate the dynamics of serotype changes after PCV introduction (Fig. 1) and verified it against observed prevalence of VT carriers among children from pre- to post-PCV era in France, the UK, Alaska (US), and Massachusetts (US). Then, using contact matrices from 34 countries empirically inferred by16, we interrogated the impact of social contact patterns on the trajectory of VT carriage decline (Fig. 2). In addition, we quantified the effect of key parameters such as vaccine efficacy and population susceptibility by changing one parameter at a time. Our findings showed that variations in social contact structure alone led to different time-to-elimination (defined here as a 95% reduction in VT proportion in carriage). We found a strong association between the contact pattern features in children under 5 and time-to-elimination. More broadly, our findings highlight the need to consider social contact structure when assessing the impact of vaccines.

A neutral, age-structured, Susceptible–Colonized transmission model. Boxes represent the state variables (\(\:S\)–Susceptible, \(\:C\)–Colonized; superscripts indicate vaccine status and age: \(\:V\)–vaccinated, \(\:N\)–unvaccinated, 1–age of one year; subscripts indicate the colonizing serotype: \(\:V\)–vaccine-targeted serotypes (VT), \(\:N\)–non-vaccine serotypes (NVT), \(\:VN\)–both VT and NVT). Arrows represent the movement of individuals between states (solid arrows: green–due to colonization with VT, brown–due to colonization with NVT, blue–due to clearance of colonizing serotypes; dotted arrow: due to aging from age 0 and being vaccinated; dot-dash arrow: due to aging from age 0 and not being vaccinated, dashed arrows: due to aging). For simplicity, only the second age group (superscript 1: age of one year) is represented.

The modeling workflow. The top row shows the components entering the transmission model, from left to right: overall carriage prevalence by age group under different population susceptibilities and carriage duration by age fitted (red line) to observed data (grey points), contact matrices from various countries, and different types of demography. The bottom left panel shows the age-structured, Susceptible–Colonized transmission model. The bottom right panel shows the simulated decline in the proportion of VT among circulating serotypes; blue double arrow indicates the outcome – time-to-elimination – defined as the time between vaccine introduction (dashed line) and the time point when the proportion of VT among circulating serotypes dropped to 5% of its initial value in age 0.

Results

Real-world parameter sets allow the model to reproduce observed VT-carrier prevalence in children

We formulated a deterministic, Susceptible–Colonized model that simulates the transmission of VT and NVT carriage before and after the introduction of PCVs. The model was an instance of neutral null models proposed by Lipsitch et al. for multistrain pathogens17. A key property of these models is the lack of a stable coexistence equilibrium, so that any initial level of coexistence will be maintained over time for identical strains. While individual pneumococcal serotypes differ in fitness18, there is no conclusive evidence for differential transmissibility or duration of carriage for VT and NVT19. In addition, pneumococcal diversity and fitness differences extend beyond the serotype level12. Given these considerations, we opted for a neutral model as a parsimonious way to achieve initial levels of co-existence without having to specify serotype-specific parameters.

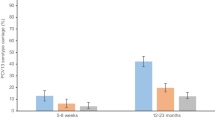

The simulations using location-specific contact matrices and parameter sets (Table 1) broadly captured the observed dynamics of VT-carrier prevalence in children in the post-PCV era in the UK, Alaska, and Massachusetts, and with some discrepancy, in France (Fig. 3). In general, the observed VT-carrier prevalence declined slightly more rapidly than in the simulation. The VT-carrier prevalence in the pre-vaccine era was higher in France (43.9%, 95% CI 38.4–49.4%)20 and the UK (31.9%, 28.1–36.1%)21 than in Alaska (20%, 15.7–24.7%)22. For Massachusetts, the VT-carrier prevalence was 9.7% half year after vaccine introduction23. In all locations, the rapid decline in VT-carriers immediately after vaccine introduction was followed by a slower decline as VT-carriers became less prevalent.

Simulated VT-carrier prevalence in children versus observed data in four locations. The lines indicate the simulated VT-carrier prevalence in children using a range of assumed vaccine efficacies against colonization acquisition (VEcol) (light blue: 0.33, blue: 0.60, dark blue: 0.77) in four locations: France; UK; Alaska, US; and Massachusetts, US from before to after the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (dashed line). Black points show the observed VT-carrier prevalence with 95% CI indicated by the error bars.

The time-to-elimination was predicted to be shortest in children aged 1–5—a group that benefits from both direct and indirect protection from PCV

We defined time-to-elimination as the duration between vaccine introduction and the time point when replacement was considered complete (i.e., 95% reduction in VT proportion in carriage). Using contact matrices derived from census and survey data in 34 countries16, our transmission model produced variable time-to-elimination, ranging from 3.8 to 6 years in newborns, which was a fully unvaccinated age population and thus reflected the indirect effect of PCV introduction. The time-to-elimination in adults was similar to that in age 0 (Fig. 4). In contrast, the time-to-elimination was the shortest in children of age 1 and above until age 5 in most countries and until age 10–11 in Ireland, the Netherlands, and the US. This finding corresponded well with the observation that PCV impact could be observed earlier in children than in adults24, which is likely due to children of these ages having received the vaccine themselves and benefiting from both direct and indirect protections. They were also the age populations with the highest VT-carrier prevalence (Supplementary Fig. 6) and a moderate contact rate (Fig. 5A).

The predicted time-to-elimination by age group in 34 countries. The density plots show the average simulated time-to-elimination in an age group for each of the 34 contact matrices. The results for 8 contact matrices from different continents and income groups59, representative of distinct social contact structures16—Australia, Canada, China, India, Japan, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States—are highlighted as examples.

Total contact rate and assortativity predict time-to-elimination. The top row shows two contact features by age group in 34 countries: total contact rate, defined as the average total daily contacts in the age group (A), and assortativity, defined as the fraction of within-age group contact (B). The data points from Australia, Canada, China, India, Japan, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States are highlighted as examples. The bottom row shows the correlation between time-to-elimination and standardized contact rate (x-axis) by standardized assortativity (color scale) in children under 5 in the simulated data (C) and the generalized linear model (D).

In the sensitivity analyses, we considered two additional scenarios: (1) a lower prevalence of carriers at age 0 due to the time lag from birth to first pneumococcal acquisition, and (2) a higher prevalence of carriers in all ages to simulate settings with higher pneumococcal burden (Supplementary Fig. 6). The results remained similar (time-to-elimination range: 4.2–7.1 years, 4.4–6.9 years).

Time-to-elimination was highly dependent on contact patterns in children under 5—the group with the highest carriage prevalence

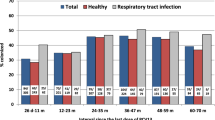

To delineate the effect of mixing patterns in different age groups, we looked at two age group-specific social contact features that may be important for respiratory infection transmission25: contact rate (total daily contacts) and assortativity (fraction of within-group contact).

Across countries, the contact rate increased from children under 5 (0–4 y) to peak around school-age (5–9 y) and teenage years (10–19 y), and declined towards older age (65–84 y) (Fig. 5A). In general, assortativity tended to be the lowest in children under 5. The change of assortativity with age was more variable than that of contact rate across countries, and we noted four major patterns (Fig. 5B). In some contact matrices (e.g., Australia, China, India, Japan, US), the fraction of assortative contact increased with age, reaching the peak among teenagers, and either remained high (e.g., Australia, Japan, US) or declined (e.g., China, India) in adulthood. In other contact matrices (e.g., Canada, South Africa, UK), assortativity were similar from birth until teenage and then either remained similar (e.g., Canada, UK) or declined towards older age (e.g., South Africa).

In our simulation, we assumed children under 5 had the highest prevalence of carriers based on a systematic review26. However, this age group had lower contact rates than the other age groups (Fig. 5A). In contrast, age groups with higher contact rates (5–39 y) tended to have lower carriage prevalence (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Fig. 6).

A plot of simulated time-to-elimination against contact rate and assortativity revealed a strong negative correlation between the contact patterns and time-to-elimination in children under 5 but not in other age groups (Fig. 5C, Supplementary Fig. 13). Since time-to-elimination in all ages was correlated within the same country (Fig. 4), this result suggests the contact rate and assortativity in children under 5 may be useful in predicting the time-to-elimination in a country. Using a generalized linear model (GLM) with only these two predictors, we found that contact rate and assortativity in children under 5 explained most of the variability in the simulated time-to-elimination (\(\:{R}^{2}\): 0.95). Both features accelerated reduction of VT (Fig. 5D): one standard deviation of increase in total contact rate and fraction of assortative contact shortened time-to-elimination by 5.2% (95%CI 3.7–6.7%) and 7.7% (95%CI 6.3–9.2%), respectively. To test the prediction performance of this model, we left 4 randomly selected contact matrices out as the test set and used the remaining 30 contact matrices as the training set. Repeating this procedure 10 times gave a mean relative absolute error (MRAE) of 1.2–5% (Supplementary Table 2), indicating good out-of-sample prediction.

Time-to-elimination remained similar when using empirical demography and additional information emerged from the contact patterns of older children when assuming high transmission

In the sensitivity analysis where we used empirical demography instead of assuming the same demography with constant population size across ages for all contact matrices, the simulated time-to-elimination remained generally similar, with countries such as India and South Africa showing slightly higher deviation (Supplementary Fig. 11). The correlation between the contact patterns and time-to-elimination persisted in children under 5 (\(\:{R}^{2}\): 0.86) and again, was not observed in other age groups (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 14). In another sensitivity analysis where we assumed higher prevalence of carriers for all ages (Supplementary Fig. 6), a weak correlation (\(\:{R}^{2}\): 0.32) emerged between contact patterns and time-to-elimination in school-age children (5–9 y) while the correlation remained the strongest in children under 5 (\(\:{R}^{2}\): 0.91) (Supplementary Fig. 15). Taken together, these results suggest the contact features in the high-carriage group (children under 5) are useful predictors of time-to-elimination and shed light on the potential additional information from wider children age groups under high transmission.

Higher vaccine efficacy and coverage and slower waning of vaccine immunity accelerate time-to-elimination

To investigate the effect of key parameters on time-to-elimination, we varied one parameter at a time and measured the simulated time-to-elimination using contact matrices from16. The key parameters tested were vaccine efficacy against carriage acquisition, vaccine coverage in the target age group (1-year-old), waning rate of vaccine immunity, the initial proportion of VT- and NVT-carriers, and population susceptibility to carriage acquisition (with 3 levels considered: high, medium, or low). Table 2 shows the list of parameters in the model.

Among the key parameters studied, vaccine factors resulted in the most prominent changes in time-to-elimination. When vaccine coverage reached 90%, using a highly efficacious vaccine (VE: 77%) led to a 1.7–2.5-year reduction in time-to-elimination compared with a less efficacious vaccine (VE: 33%) (Fig. 6A). At lower coverage (50%), VT elimination was slower (4.9–7.8 years vs. 3.8–6 years in 90% coverage, VE: 60%), and the same increase in vaccine efficacy (33% to 77%) caused a greater reduction in time-to-elimination (Supplementary Fig. 7). In addition to no waning, we tested various durations of vaccine-conferred immunity and found that rapid waning (immunity duration of 3 years) slowed elimination by 0.5–1.6 years compared with slow waning (immunity duration of 10 years) (Fig. 6B).

The effect of key parameters on time-to-elimination. Each point represents the time-to-elimination simulated by changing one key parameter at a time (A: vaccine efficacy against colonization acquisition, B: waning rate of vaccine-conferred immunity against colonization acquisition, C: initial proportion of VT among circulating serotypes, D: population susceptibility) using the contact matrices from 34 countries with 8 highlighted for comparison (Australia, Canada, China, India, Japan, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States). The overall carriage prevalence before the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) in each country is represented by the same color scale in panels A, B, and C, and with a different color scale in panel D, because changing the population susceptibility naturally resulted in different pre-PCV overall carriage prevalence in a given country.

Given a fixed pre-PCV total pneumococcal carriage, increasing the initial proportion of VT among colonizing serotypes (quantity \(\:F\), see Methods) by changing initial VT: NVT: Co-carriers ratio slowed elimination slightly (Fig. 6C, Supplementary Fig. 8), while maintaining \(\:F\) led to constant time-to-elimination (Supplementary Fig. 9). With constant \(\:F\), we further considered a range of competition levels (\(\:{k}_{V}\)=\(\:{k}_{N}\)=0.1, 0.25, 0.75) and found that time-to-elimination remained similar (time-to-elimination range: 4.2–6.2 years, 4–6.1 years, 3.6–5.9 years) (Supplementary Fig. 10).

We changed the age-specific susceptibility parameter \(\:{\beta\:}^{\left(i\right)}\) by ± 20% to simulate for high and low susceptibility. As expected, the total pneumococcal carriage pre-PCV increased with population susceptibility. However, the predicted effect of this parameter was moderate: transitioning from low to high population susceptibility resulted in 0.6–1.8 years longer time-to-elimination. This result may be explained by the fact that, for higher total carriage, more circulating VT had to be replaced. Considering the same population susceptibility level, countries with higher pre-PCV pneumococcal carriage had longer time-to-elimination, except for Canada, South Africa and the UK (Fig. 6D), for which the contact rate and assortativity in children under 5 was the highest among the 8 countries highlighted as examples (Fig. 5A, B).

In summary, of all the parameters tested, the vaccine parameters had the strongest impact on time-to-elimination, while the other parameters had a more moderate effect. This result highlights the need for accurate estimates of PCVs properties to predict the time scale of VT elimination in a target population.

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to assess the effect of social contact structure on the impact of PCVs. To do so, we designed a pneumococcal transmission model, parameterized based on empirical data, and verified it against the observed decline in VT carriage among children in France, the UK, Alaska (US), and Massachusetts (US). Using the best available social contact matrices from 34 countries, our study showed that heterogeneity in contact structure alone can lead to a range of time-to-elimination and thus sensitively affect the impact of PCVs. In addition, they highlight the key role of contact features in children under 5 in VT elimination and provide new insights into the mechanisms of VT elimination. More broadly, these findings identify social contact structure as a new key variable affecting vaccine impact, with potential implications beyond PCVs.

Our model predicted a range of time-to-elimination (3.8–6 years) that is consistent with the literature27,28,29, in support of the WHO’s recommendation that 5 years of post-PCV data are necessary to assess pneumococcal serotype replacement30. The modeled time-to-elimination in our study was the shortest among vaccinated age groups, who had the most social contacts, reflecting combined direct and indirect effectiveness, in contrast to age 0, who benefited from indirect effectiveness only (Fig. 4). This finding aligns with the reported direct and indirect effects of PCV on carriage11.

Different features of a contact matrix can have different effects on infectious disease dynamics. For example, assortativity, a well-studied feature measuring the extent of preferential mixing of individuals within the same demographic stratum, was shown to drive the spread of HIV infections differently in groups with different risks31. Another widely used feature is the number of social contacts, which was suggested as the main factor that explained the higher COVID rates among older adults in Italy25. We investigated these two features in our study and observed that the total contact rates in all countries followed a similar trend, with lower contact rates in extreme ages and a peak around school-age and teenage years (5–19 y); contrastingly, there was a much higher variability in assortativity across countries. We found both features in children under 5 to be significant predictors for shorter time-to-elimination, indicating children under 5 as the key age group in driving the serotype replacement dynamics, despite having a lower contact rate than other age groups. The high contact rate and assortativity in children under 5 in Canada and South Africa could explain why they were the outliers with shorter time-to-elimination despite higher pre-PCV pneumococcal carriage (Fig. 6D). As we increased the carriage prevalences across ages in the sensitivity analysis, we observed a signal of additional information from the contact patterns of older children (5–9 y) (Supplementary Fig. 15). These findings are consistent with those reported in the modelling literature—children under 5 are key for pneumococcal transmission; however, in high transmission settings, the pneumococcal reservoir may involve a wider age group, including school-age children32.

Intuitively, higher total contact rates would speed up the transmission dynamics and shorten time-to-elimination. The effect of assortativity can be explained by the high carriage prevalence in this age group. Children under 5 had the highest carriage prevalence, so a more assortative contact in this age group would promote the within-group transmission. In general, infection spreads faster for a high-risk group with assortative mixing because contacts with low-risk groups slow down the transmission dynamic31. These findings point to the vital role of contact patterns in the high-prevalence groups in infection transmission and can be the basis of infection prevention strategies.

In addition to social contact structure, we found vaccine factors to be the most influential parameters in the serotype replacement dynamics. This finding is consistent with the epidemiological evidence that locations with high vaccine coverage saw rapid carriage replacement27. We also found that rapid waning led to longer time-to-elimination. Furthermore, the initial VT: NVT: Co-carriers ratio and population susceptibility had slight to moderate effects. Given the same overall carriage, the initial VT: NVT: Co-carriers ratio only affected the time-to-replacement if the proportion of VT among circulating serotypes, \(\:F\), was changed: higher \(\:F\) led to a longer time-to-elimination. The time-to-elimination was also longer in a more susceptible population whose overall carriage is higher. These results demonstrated that when the circulating VT burden is higher, it takes longer for replacement to be complete.

Our study has several limitations. When simulating the VT-carrier prevalence in children using location-specific parameter sets, our model captured the patterns in the observed data in the UK, Alaska (US), Massachusetts (US), but with some discrepancy in the initial post-PCV era, in France. This discrepancy potentially stemmed from the partial uptake of PCV in the private market, reaching a vaccine coverage of over 20% in the year before vaccine introduction in our simulation33. In the simulations, we considered the uncertainty in vaccine efficacy but not in other parameters, which may have contributed to the VT-carrier prevalence decline being slightly slower than observed. For example, competition between VT and NVT could have enhanced the population-level impact of PCV34. Specifically, competition can be driven by direct competition between VT and NVT in the nasopharynx, or indirect competition due to innate and adaptive immunity that is cross-reactive for NVT and VT, or both34,35. We considered only direct competition in our model. We also did not consider seasonal fluctuations in contact rates and assortativity, which could affect the transmission of infections36,37. How this biased the estimated time-to-elimination depends on whether holidays increase the total contacts considering the change in both inter-age and intra-age contacts. Most of the contact matrices used in this study came from high-income countries, limiting our findings’ generalizability to other settings. In settings with high residual transmission despite persistently high vaccine coverage38, the prevalence of underlying vulnerable groups may be important39. While there were published contact matrices for more countries40,41, the ones used in our study offer the best age resolution to date. The variation of contact patterns across geographic locations and income settings is expected to be larger than observed in this study, and including them in future studies could help elucidate the trends observed outside high-income settings. For instance, in high transmission settings, the pneumococcal reservoir may involve a wider age group, including school-age children32. Given the evidence of a higher extent of serotype replacement in indigenous children in Fiji42 and in rural areas in Nigeria43, future studies should explore further how contact patterns in sub-populations within the same country influence serotype replacement. Finally, an alternative approach to address our research question would be to generate synthetic social contact matrices, which would permit a better characterization of the effect of specific contact features (such as assortativity).

Despite these limitations, our study demonstrated how to combine contact matrices and mathematical modeling to unravel the dynamics between the host, the pathogen, and a public health intervention. The strengths of our study included using a neutral model, which is a parsimonious way to achieve initial levels of VT and NVT co-existence without specifying serotype-specific parameters, and using contact matrices of high age resolution, which allowed us to differentiate the transmission dynamics in every year of age. In addition, for parameters with variable estimates, we based our assumptions on non-linear models fitted to extracted data from observational studies. In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that, as for other vaccine-preventable diseases, social contact structure is a critical element for understanding the vaccine epidemiology of pneumococcus. Hence, we propose this element should be considered in future studies assessing the impact of PCVs and, more broadly, of other vaccines.

Methods

We proceeded in three steps. First, we developed a dynamic model of pneumococcal carriage transmission (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). The parameter values were based on empirical data, taken from literature, or assumed (Table 2). We verified this model’s adequacy against the observed prevalence of VT carriers among children from pre- to post-PCV era in France (1999–2008), the UK (2002–2016), Alaska (2000–2009), and Massachusetts (2001–2008) (Table 1). Second, we simulated the dynamics of pneumococcal carriage transmission after PCV introduction using contact matrices from 34 countries16 and assessed the impact of social contact patterns on the dynamics of VT carriage decline. Third, we changed one key parameter (such as vaccine efficacy and population susceptibility) at a time in the simulations investigate the effect of each key parameter on VT elimination. We describe the Data, the Model, and the details of these three steps in the Analyses below.

Data

Contact matrices and demography

We used the inferred contact matrices \(\:{M}_{ij}\) from16. The contacts, stratified by age yearly from 0 to 84, were derived from synthetic networks built using population census data and socio-demographic surveys. The overall contact matrix for a location is a weighted sum of the setting-specific (i.e., household, school, workplace, and community) contact matrices. \(\:{M}_{ij}\) gives the total number of daily contacts between age groups \(\:i\) and \(\:j\) per person in age group \(\:i\), we applied reciprocity correction on \(\:{M}_{ij}\) and transformed it into \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{m}}_{ij}\), which gives the total annual contacts between age groups \(\:i\) and \(\:j\) per person in age group \(\:i\) and per person in age group \(\:j\) (density scale, as defined in44; see Supplementary Fig. 3). To elucidate the effect of social contact patterns, we used a common population structure for all contact matrices in our simulations. As sensitivity analyses, we repeated the simulations using country-specific empirical demography from16 and birth rate from the World Bank Open Data45.

Carriage duration and prevalence

We extracted data about age-specific carriage duration and carriage prevalence from published studies identified through a scoping literature search.

Among the identified culture-based studies, we included the studies that reported median durations (n = 8) (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Data 1), because the duration of carriage has a left-skewed distribution, with few individuals showing lasting carriage. For the model of carriage duration with age, we used non-linear least squares regression to estimate the parameters in the equation (Supplementary Fig. 2):

where \(\:a=21\) (standard error: 5.8), \(\:b=62\:\left(14.6\right)\), and \(\:c=0.45\:\left(0.4\right)\).

In the main analysis, we fixed the age-specific initial carriage prevalence \(\:{f}_{C}^{\left(i\right)}\left(0\right)\) based on26 and the age-specific susceptibility parameter \(\:{\beta\:}\!^{\left(i\right)}\) based on47. As sensitivity analyses, we used two other distributions of \(\:{\beta\:}\!^{\left(i\right)}\) over age, considering a lower carriage prevalence in age 0 and a higher carriage prevalence in all ages, to reflect the observed data from the identified culture-based pre-PCV carriage prevalence studies (n = 17) (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6, Supplementary Data 2). After calibrating \(\:{\beta\:}\!^{\left(i\right)}\) for the assumed carriage prevalences, we re-simulated the time-to-elimination for all countries.

VT-carrier prevalence in children in the real world

We extracted the VT-carrier prevalence in children from the pre- to post-PCV era in 4 locations—France20, the UK21, Alaska22, and Massachusetts23 (Supplementary Data 3)—to verify our model’s ability to reproduce the decline in VT-carrier prevalence following PCV introduction. The observed data come from cross-sectional surveys among children attending daycare centers or primary care clinics. In all four included studies, the detection of S. pneumoniae was culture-based, and the serotyping was either by traditional Quellung reaction or molecular methods. For point estimates of carriage reported without uncertainty, we calculated the standard error (SE) for proportion and indicated the uncertainty limits as 1.96×SE from the mean.

Model

We formulated a deterministic model that simulates the transmission of VT and NVT carriage (Fig. 1) based on the neutral null model proposed by17. Assuming a stable population (i.e., birth rate = death rate), susceptible individuals (\(\:S\)) become VT-carriers (\(\:{C}_{V}\)) at the rate \(\:{\lambda\:}_{V}\), or NVT-carriers (\(\:{C}_{N}\)) at the rate \(\:{\lambda\:}_{N}\). Mono-carriers \(\:{C}_{V}\) (or \(\:{C}_{N}\)) can be colonized by the other serotype at rate \(\:{{k}_{N}\times\:\lambda\:}_{N}\) (or \(\:{{k}_{V}\times\:\lambda\:}_{V}\)) and become co-carriers (\(\:{C}_{VN}\)), and co-carriers return to mono-carriers \(\:{C}_{V}\) (or \(\:{C}_{N}\)) at rate \(\:{{c\times\:k}_{V}\times\:\lambda\:}_{V}\) (or \(\:{{c\times\:k}_{N}\times\:\lambda\:}_{N}\)). We assumed the inter-serotype competition parameter, \(\:k\), to be 0.5 in the main analysis and tested a range of values (0.1, 0.25, 0.75) based on published estimates18,46,47. When \(\:{k}_{V}\)=0.5, VT is half as likely to colonize an individual already colonized by NVT. We further assumed this competition to be symmetrical (\(\:{k}_{V}={k}_{N}\)) to ensure neutrality at initiation. The parameter \(\:c\), representing the fraction of co-carriers returning to \(\:{C}_{V}\) (or \(\:{C}_{N}\)) upon re-infection with VT (or NVT), was fixed to 0.5 to ensure neutrality48.

The vaccine was introduced at time \(\:{t}_{V}\) and had a coverage of \(\:{p}_{V}\). Therefore, \(\:{p}_{V}\) was zero before time \(\:{t}_{V}\) and equal to \(\:{p}_{V}\) starting from time \(\:{t}_{V}\).

In our age-structured model, individuals moved from one age to the next year of age at an aging rate \(\:{\delta\:}\!_{i}\)=1 per year. The whole population of newborns was unvaccinated. As individuals moved from age 0 to age 1, a fraction (\(\:{p}_{V}\)) of the population was vaccinated and partially protected from pneumococcal colonization (superscript “\(\:(V,1)\)”). The rest (\(\:1-{p}_{V})\) of age 0 stayed unvaccinated as they reached age 1 (superscript “\(\:(N,1)\)”).

For the dynamics of the vaccinated individuals, the rate of VT carriage acquisition \(\:{\lambda\:}_{V}\) was reduced by a factor \(\:VE\), where \(\:VE\) represents the vaccine efficacy against acquisition of VT carriage. Vaccine-conferred immunity was assumed to wane at a rate \(\:{\alpha\:}\!_{V}\), so that \(\:1/{\alpha\:}\!_{V}\) represents the average duration of vaccine protection.

The age-specific carriage acquisition rate, \(\:{\lambda\:}\!^{\left(i\right)}\), depends on \(\:{\beta\:}\!^{\left(i\right)}\), the cumulative number of carriers in the contactee age groups, \(\:C{C}^{\left(j\right)}\), and the per capita contact matrix, \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{m}}_{ij}\). The carriage acquisition rates for VT and NVT were expressed as:

where

Here, \(\:q\) refers to the relative infectiousness of each serotype for co-carriers.

Table 2 summarizes the parameters used in this study.

Outcome definition

In a neutral null model, one serotype is not assumed to have a fitness advantage over the other; therefore, co-carriers transmit either VT or NVT at equal probability. The relative infectiousness with each serotype for co-carriers, \(\:q\), is set to 0.5, such that co-carriers are equally infectious as mono-carriers17. To ensure neutrality in the null model, we checked if \(\:F\) was stable over time in the model without an effective vaccine, as suggested by17 (Supplementary Fig. 4). \(\:F\) is given by:

We defined time-to-elimination as the duration between vaccine introduction and the time when \(\:F\) dropped to 5% of its initial value in age 0, representing a fully unvaccinated population and reflecting the indirect effect of PCV introduction. As time-to-elimination in all ages were highly correlated in each country, the choice of age had a negligible effect on the analyses comparing countries.

Analyses

Model assessment

To verify the model, we used location-specific contact matrices and parameter sets to simulate the VT-carrier prevalence in children from the pre- to post-PCV era in 4 locations (Table 1) and compared the simulated values to the observed ones qualitatively.

We calibrated the model for each location by estimating the parameters \(\:{\beta\:}\!^{\left(i\right)}\). First, we performed a global search on 1000 values between − 10 and 10, corresponding to \(\:\beta\:\) values between 0 and 1 on the logit-transformed scale. The values were sampled using Sobol’s sequence49, a quasi-random sampling method, to ensure the global parameter space was searched thoroughly. The global search sought a set of \(\:{\beta\:}\!^{\left(i\right)}\) that minimized the total squared difference in simulated versus observed pre-PCV VT-carrier prevalence on the logarithmic scale in all age groups. Here, the age groups were defined based on the observed prevalences as 0 y, 1–4 y, 5–17 y, 18–39 y, 40–59 y, and 60–84 y. The best five solutions from the global search were used as the starting value for a local search using the Subplex algorithm50 until the total squared difference was minimized or could not be further reduced after a maximum of 1000 evaluations. Given the uncertainty around this parameter, we simulated the VT-carrier prevalence in children in each location using a range of vaccine efficacy against colonization51.

Effect of contact features

After model assessment, we moved on to investigate the effect of social contact structure on the replacement dynamics. We first summarized the contact matrices using two age group-specific features—contact rate and assortativity—and then explored the relationship between these features and the time-to-elimination. Here, the age groups were defined as 0–4 y, 5–9 y, 10–19 y, 20–39 y, 40–59 y, and 60–84 y, to be consistent with the parameter value assignment (Table 2). We defined contact rate as the average total daily contacts in an age group and assortativity as the fraction of contacts from within the age group out of total contacts for each age in the age group.

We described the distribution of total contact and assortativity over age in all 34 contact matrices (Fig. 5A, B) and explored the association between time-to-elimination and these contact features in all age groups (Supplementary Fig. 13). We also looked at this association in the sensitivity analyses, where we used empirical demography (Supplementary Fig. 14), and where we assumed different carriage prevalences across ages (Supplementary Fig. 15).

Based on the strong negative correlation between the two contact features and time-to-elimination portrayed in children under 5 (Fig. 5C), we performed a regression analysis on time-to-elimination with standardized contact rate and standardized assortativity in this age group as predictors in a GLM with a log link (Fig. 5D). We reported the effect estimates with 95%CI for both variables and assessed the goodness-of-fit with \(\:{R}^{2}\). We further tested the out-of-sample prediction performance of the GLM containing only these two predictors by leaving 4 contact matrices out as the test set and using the remaining 30 contact matrices as the training set. We repeated this procedure 10 times and reported the MRAE for each iteration (Supplementary Table 2).

Effect of key parameters

To delineate the individual effect of the key parameters— vaccine efficacy, vaccine coverage, immunity waning, the initial proportions of VT and NVT carriers, and population susceptibility—on time-to-elimination, we varied them one at a time using a range of values and measured the time-to-elimination.

Vaccine efficacy and coverage were considered key parameters because these contributed to the selective pressure that drives serotype replacement. We varied vaccine efficacy between 33 and 77% based on the observed efficacy with uncertainty in a community randomized trial51, consistent with the findings of a systematic review52. Other than no waning, we tested a range of durations of vaccine-conferred immunity, ranging from 3 to 10 years53,54. Evidence suggests pre-PCV serotype distribution in carriage and diseases as important predictors of vaccine impact55; therefore, we tested a range of initial proportions of VT-carriers (\(\:{f}_{V}\left(0\right)\)), NVT-carriers (\(\:{f}_{N}\left(0\right)\)), and implicitly, co-carriers (1–\(\:{f}_{V}\left(0\right)\)–\(\:{f}_{N}\left(0\right)\)), either allowing the proportion of VT among colonizing serotypes (\(\:F\)) to fluctuate or be fixed at 0.65. For constant \(\:F\), we further considered a range of competition levels (\(\:{k}_{V}\)=\(\:{k}_{N}\)=0.1, 0.25, 0.75) in the sensitivity analysis.

In these model experiments, the age-specific overall carriage prevalence remained constant. Lastly, to investigate the dynamics under different population susceptibilities, we changed the age-specific susceptibility parameter, \(\:{\beta\:}\!^{\left(i\right)}\), by ± 20% compared to the baseline value, which led to higher and lower overall carriage, respectively. In each simulation, we used 34 contact matrices from16 to see if the effect of each key parameter differs by social contact structure.

Numerical implementation

All analyses were conducted in RStudio with R version 4.5.1) and the non-linear model fitting was performed using the base package “stats”56. The transmission model was implemented using the package “pomp” version 4.657. All optimization procedures were implemented using the algorithms available in the package “nloptr” version 2.0.358.

Data availability

The code and data are available from Edmond, the Open Data Repository from the Max Planck Society: https://doi.org/10.17617/3.RIGYAK.

References

GBD 2019 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 400, 2221–2248 (2022).

Myint, T. T. H. et al. The impact of 7-valent Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive Pneumococcal disease: a literature review. Adv. Ther. 30, 127–151 (2013).

Weinberger, D. M., Malley, R. & Lipsitch, M. Serotype replacement in disease after Pneumococcal vaccination. Lancet 378, 1962–1973 (2011).

Feikin, D. R. et al. Serotype-specific changes in invasive Pneumococcal disease after Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction: a pooled analysis of multiple surveillance sites. PLoS Med. 10, e1001517 (2013).

Ganaie, F. et al. A New Pneumococcal Capsule Type, 10D, is the 100th Serotype and Has a Large cps Fragment from an Oral Streptococcus. MBio 11(3), 10–1128 (2020).

Ganaie, F. A. et al. Discovery and characterization of Pneumococcal serogroup 36 capsule subtypes, serotypes 36A and 36B. J. Clin. Microbiol. 61, e0002423 (2023).

Lipsitch, M. Bacterial vaccines and serotype replacement: lessons from haemophilus influenzae and prospects for Streptococcus pneumoniae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5, 336–345 (1999).

Martcheva, M., Bolker, B. M. & Holt, R. D. Vaccine-induced pathogen strain replacement: what are the mechanisms? J. R Soc. Interface. 5, 3–13 (2008).

Weiser, J. N., Ferreira, D. M. & Paton, J. C. Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 355–367 (2018).

Lewnard, J. A. & Hanage, W. P. Making sense of differences in Pneumococcal serotype replacement. Lancet Infect. Dis. 19, e213–e220 (2019).

Chan, J. et al. Using Pneumococcal carriage studies to monitor vaccine impact in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine 37, 6299–6309 (2019).

Gjini, E. Geographic variation in Pneumococcal vaccine efficacy estimated from dynamic modeling of epidemiological data post-PCV7. Sci. Rep. 7, 3049 (2017).

Mosser, J. F. et al. Nasopharyngeal carriage and transmission of Streptococcus pneumoniae in American Indian households after a decade of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine use. PLoS One 9(1), e79578 (2014).

Qian, G. et al. Association of Pneumococcal carriage in infants with the risk of carriage among their contacts in Nha trang, vietnam: A nested cross-sectional survey. PLoS Med. 19, e1004016 (2022).

Danon, L., House, T. A., Read, J. M. & Keeling, M. J. Social encounter networks: collective properties and disease transmission. J. R Soc. Interface. 9, 2826–2833 (2012).

Mistry, D. et al. Inferring high-resolution human mixing patterns for disease modeling. Nat. Commun. 12, 323 (2021).

Lipsitch, M., Colijn, C., Cohen, T., Hanage, W. P. & Fraser, C. No coexistence for free: neutral null models for multistrain pathogens. Epidemics 1, 2–13 (2009).

Lipsitch, M. et al. Estimating rates of carriage acquisition and clearance and competitive ability for Pneumococcal serotypes in Kenya with a Markov transition model. Epidemiology 23, 510–519 (2012).

Cauchemez, S. et al. S. pneumoniae transmission according to inclusion in conjugate vaccines: bayesian analysis of a longitudinal follow-up in schools. BMC Infect. Dis. 6, 14 (2006).

Dunais, B., Bruno-Bazureault, P., Carsenti-Dellamonica, H., Touboul, P. & Pradier, C. A decade-long surveillance of nasopharyngeal colonisation with Streptococcus pneumoniae among children attending day-care centres in south-eastern france: 1999–2008. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30, 837–843 (2011).

Southern, J. et al. Pneumococcal carriage in children and their household contacts six years after introduction of the 13-valent Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in England. PLoS One. 13, e0195799 (2018).

Gounder, P. P. et al. Impact of the Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and antibiotic use on nasopharyngeal colonization by antibiotic nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae, alaska, 2000[FIGURE DASH]2010. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 34, 1223–1229 (2015).

Wroe, P. C. et al. Pneumococcal carriage and antibiotic resistance in young children before 13-valent conjugate vaccine. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 31, 249–254 (2012).

Andrade, A. L. et al. Direct and indirect impact of 10-valent Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction on pneumonia hospitalizations and economic burden in all age-groups in brazil: A time-series analysis. PLoS One. 12, e0184204 (2017).

Sage, L., Albertini, M. & Scherer, S. The spreading of SARS-CoV-2: interage contacts and networks degree distribution. PLoS One. 16, e0256036 (2021).

Clifford, S. et al. Global landscape ofStreptococcus pneumoniaeserotypes colonising healthy individuals worldwide before vaccine introduction; a systematic review and meta-analysis. BioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.09.23287027 (2023).

Hanage, W. P. et al. Evidence that Pneumococcal serotype replacement in Massachusetts following conjugate vaccination is now complete. Epidemics 2, 80–84 (2010).

Gladstone, R. A. et al. Five winters of Pneumococcal serotype replacement in UK carriage following PCV introduction. Vaccine 33, 2015–2021 (2015).

Rinta-Kokko, H., Nurhonen, M. & Auranen, K. Impact and effectiveness of a conjugate vaccine against invasive Pneumococcal disease in Finland - a modelling approach. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 17, 1834–1843 (2021).

World Health Organization. Measuring impact of streptococcus pneumoniae and haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccination. World Health Organization. Report No.: WHO/IVB/12.08. (2012). Available: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/75835

Jacquez, J. A., Simon, C. P., Koopman, J., Sattenspiel, L. & Perry, T. Modeling and analyzing HIV transmission: the effect of contact patterns. Math. Biosci. 92, 119–199 (1988).

Flasche, S., Lipsitch, M., Ojal, J. & Pinsent, A. Estimating the contribution of different age strata to vaccine serotype Pneumococcal transmission in the pre vaccine era: a modelling study. BMC Med. 18, 129 (2020).

de Cellès, M. D. et al. Interaction of vaccination and reduction of antibiotic use drives unexpected increase of Pneumococcal meningitis. Sci. Rep. 5, 11293 (2015).

Masala, G. L., Lipsitch, M., Bottomley, C. & Flasche, S. Exploring the role of competition induced by non-vaccine serotypes for herd protection following Pneumococcal vaccination. J. R Soc. Interface. 14, 20170620 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Auranen, K. & Eichner, M. The influence of competition and vaccination on the coexistence of two Pneumococcal serotypes. Epidemiol. Infect. 132, 1073–1081 (2004).

Hens, N. et al. Estimating the impact of school closure on social mixing behaviour and the transmission of close contact infections in eight European countries. BMC Infect. Dis. 9, 187 (2009).

Ewing, A., Lee, E. C., Viboud, C. & Bansal, S. Contact, travel, and transmission: The impact of winter holidays on influenza dynamics in the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 215(5), 732–739 (2016).

Swarthout, T. D. et al. High residual carriage of vaccine-serotype Streptococcus pneumoniae after introduction of Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Malawi. Nat. Commun. 11, 2222 (2020).

Phiri, J. et al. Estimating Pneumococcal carriage dynamics in adults living with HIV in a mature infant Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine programme in malawi, a modelling study. BMC Med. 22, 419 (2024).

Prem, K., Cook, A. R. & Jit, M. Projecting social contact matrices in 152 countries using contact surveys and demographic data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005697 (2017).

Prem, K. et al. Projecting contact matrices in 177 geographical regions: an update and comparison with empirical data for the COVID-19 era. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009098 (2021).

Dunne, E. M. et al. Effect of ten-valent Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction on Pneumococcal carriage in fiji: results from four annual cross-sectional carriage surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 6, e1375–e1385 (2018).

Adamu, A. L. et al. The impact of introduction of the 10-valent Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on Pneumococcal carriage in Nigeria. Nat. Commun. 14, 2666 (2023).

Arregui, S., Aleta, A., Sanz, J. & Moreno, Y. Projecting social contact matrices to different demographic structures. PLoS Comput. Biol. 14, e1006638 (2018).

World Bank Open Data. In: World Bank Open Data [Internet]. [cited 6 Jul 2025]. Available: https://data.worldbank.org

Melegaro, A. et al. Dynamic models of Pneumococcal carriage and the impact of the heptavalent Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive Pneumococcal disease. BMC Infect. Dis. 10, 90 (2010).

Flasche, S. et al. Assessing the efficiency of catch-up campaigns for the introduction of Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: a modelling study based on data from PCV10 introduction in kilifi, Kenya. BMC Med. 15, 113 (2017).

Colijn, C. et al. What is the mechanism for persistent coexistence of drug-susceptible and drug-resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae? J. R Soc. Interface. 7, 905–919 (2010).

Sobol’, I. M. On the distribution of points in a cube and the approximate evaluation of integrals. Zh Vychisl Mat Mat Fiz. (1967). Available: https://www.mathnet.ru/eng/zvmmf7334

Rowan, T. Functional Stability Analysis of Numerical Algorithms. (1990).

O’Brien, K. L. et al. Effect of Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on nasopharyngeal colonization among immunized and unimmunized children in a community-randomized trial. J. Infect. Dis. 196, 1211–1220 (2007).

Cohen, O. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) review of impact evidence (PRIME). [cited 21 Apr 2024]. Available: https://terrance.who.int/mediacentre/data/sage/SAGE_Docs_Ppt_Oct2017/9_session_PCV/Oct2019_session9_PCV_PRIMEsummary.pdf

Ekström, N. et al. Concentration and high avidity of Pneumococcal antibodies persist at least 4 years after immunization with Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in infancy. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 20, 1034–1040 (2013).

Madhi, S. A. et al. Long-term effect of Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae–and associated interactions with Staphylococcus aureus and haemophilus influenzae colonization–in HIV-Infected and HIV-uninfected children. J. Infect. Dis. 196, 1662–1666 (2007).

Flasche, S., Le Polain de Waroux, O., O’Brien, K. L. & Edmunds, W. J. The serotype distribution among healthy carriers before vaccination is essential for predicting the impact of Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive disease. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11, e1004173 (2015).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. (2022). Available: https://www.R-project.org/

King, A. A. et al. pomp: Statistical Inference for Partially Observed Markov Processes. (2023). Available: https://kingaa.github.io/pomp/

Johnson, S. G. The NLopt nonlinear-optimization package. Available: http://github.com/stevengj/nlopt

Cieslikowski, D. World development indicators 2008. In: World Bank [Internet]. Cieslikowski, David,; [cited 27 Jun 2024]. Available: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/587251468176971009/World-development-indicators-2008

Waight, P. A. et al. Effect of the 13-valent Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive Pneumococcal disease in England and Wales 4 years after its introduction: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 15, 629 (2015).

Domenech de Cellès, M. et al. Unraveling the seasonal epidemiology of Pneumococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 116, 1802–1807 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Part of the computations were performed on the High Performing Computing clusters at the Max Planck Computing and Data Facility (MPCDF) and we thank the MPCDF for their support.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.W. and M.D.d.C. designed the study; A.W., S.C.K., D.M.W. and M.D.d.C. contributed to methodology; A.W. and M.D.d.C. coded; S.C.K. reviewed codes and contributed to reproducibility; A.W. curated the data, performed the analyses, and drafted the manuscript; S.C.K., D.M.W. and M.D.d.C. reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.W. received consulting fees from Vaxcyte for work unrelated to this manuscript. D.M.W. received consulting fees from Pfizer, Merck, GSK, Affinivax, Matrivax, and Vaxcyte for work unrelated to this manuscript and is the principal investigator on research grants from Pfizer, GSK, and Merck on work unrelated to this manuscript. M.D.d.C. received postdoctoral funding (2017–2019) from Pfizer and consulting fees from GSK for work unrelated to this manuscript. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, A., Kramer, S.C., Weinberger, D.M. et al. Assessing the effect of social contact structure on the impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. Sci Rep 15, 35012 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20255-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20255-8