Abstract

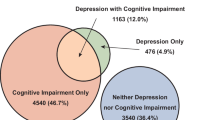

Depression is a common comorbidity in dementia, with prevalence ranging from 20 to 60% across different countries. This study examined whether depressive symptom severity levels differ by dementia characteristics and country of residence in people living with dementia. This cross-sectional analysis used baseline data from 376 participants in the HOMESIDE trial. Linear regression models examined differences in depressive symptom severity levels by dementia stage, type, severity, and country. In this sample (57% male, mean age 76.6 years), depressive symptom scores were higher for people with severe cognitive impairment than those with mild dementia (MMSE 24–30) (adjusted mean difference: 3.78, 95% CI 1.60–5.96). Mean depressive symptom severity was lower in Norway, Germany, and United Kingdom compared to Australia, with no significant difference for Poland. No apparent differences by dementia type or stage were found. Depressive symptom severity levels differed by cognitive impairment severity and country. Cross-national differences likely reflect a complex interplay of healthcare systems, cultural factors, family support structures, and societal approaches to dementia care. Regular depressive symptom screening is recommended, particularly for severe dementia.

Trial registration: ACTRN12618001799246 (Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry) and NCT03907748 (ClinicalTrials.gov).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dementia is characterized by marked impairment in two or more cognitive domains relative to that expected given the individual’s age and general premorbid level of cognitive functioning, which represents a decline from the individual’s previous level of functioning1. The common types of dementia include Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson’s dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and mixed dementia. Memory impairment is present in most forms of dementia, along with impairments in executive functions, attention, language, social cognition and judgment, psychomotor speed, and visuoperceptual or visuospatial abilities. The current clinical picture of dementia includes clinically significant behavioral, psychological, and mood disturbances, such as depressed, elevated, or irritable mood1.

Depressive symptoms are a common comorbidity in adults with dementia, with 30–50% of dementia cases accompanied by depressive symptoms2. Clinically, depressive symptoms and dementia are distinct but share some symptoms, such as mood symptoms, decreased social and occupational functioning, attention deficit, and impaired working memory. According to available research, late-life depressive symptoms are consistently associated with a two-fold increased risk of dementia3 and have been associated with an increased risk for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease4. Dementia and depressive symptoms also share biological mechanisms, including vascular disease, atrophy of the hippocampus, larger deposits of β-amyloid plaques, and inflammatory alterations5. Cross-national comparisons have found marked differences in depression prevalence across countries, with rates varying between 20 and 60%6. This variation can be attributed to differences in healthcare systems, diagnostic methods, and cultural factors influencing symptom recognition. Countries with better healthcare funding and more developed early detection and treatment systems show better outcomes in managing both dementia and associated depressive symptoms7.

The Scandinavian model of care demonstrates particularly good outcomes through comprehensive support systems. Early recognition and treatment of depressive symptoms in dementia patients can delay cognitive decline, reduce symptom severity, and improve quality of life8. These outcomes are more commonly achieved in countries with better access to early diagnostics, therapeutic options, and social support systems. Individual socioeconomic status significantly influences depressive symptom outcomes across European countries, with socioeconomic factors at the personal level playing important roles in mental health outcomes9.

Our aim was to examine whether the average level of depressive symptom severity in people living with dementia differs by dementia stage, type, severity, and country of residence. We report the findings from a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from the HOMESIDE study; an international, pragmatic, three-arm, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial.

Methods

Study design and setting

The HOMESIDE (HOME-based caregiver-delivered music intervention for people living with dementia) trial was conducted as an international randomized controlled trial, registered at the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12618001799246-05/11/2018) and ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03907748-09/04/2019). In brief, community-dwelling people with dementia and their cohabitating caregiver (dyads) in Australia, United Kingdom, Norway, Poland and Germany were randomised to one of the three arms: music, reading or usual care alone and assessed at baseline, 90-days and 180-days post-randomisation. Between 27th November 2019 and 7th July 2022, 805 dyads were screened for eligibility, with 432 randomised into the study10. Participants with complete data on the key analysis variables (n = 376) were analysed in the current study. For the present study, baseline data from this trial were leveraged to conduct a cross-sectional secondary analysis examining differences in depressive symptom severity by type, stage and severity of dementia, as well as country.

The original HOMESIDE trial was designed to examine the effects of caregiver-delivered music and reading interventions on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), with primary outcomes being caregiver quality of life and wellbeing, and secondary outcomes including healthcare cost reduction. The trial was powered to detect differences in caregiver outcomes rather than the depressive symptom patterns examined in this secondary analysis.

Recruitment procedures were standardized across all participating countries using identical inclusion and exclusion criteria, assessment protocols, and data collection procedures. All sites recruited community-dwelling dyads through similar channels including memory clinics, general practitioners, community organizations, and social media groups for family caregivers. While recruitment protocols were standardized, the actual recruitment strategies varied by country based on local healthcare systems and available resources11. The study was conducted in urban and suburban settings across all countries, with no specific rural recruitment sites10,11.

Study aims

The aims of this study were to examine whether average depressive symptom severity level of people living with dementia differs by stage of dementia (early or late onset), type of dementia (Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, vascular and mixed dementias, or other types of dementia), severity of dementia (mild dementia [MMSE 24–30], mild-moderate dementia [MMSE 19–23], moderate dementia [MMSE 10–18], or severe dementia [MMSE < 10]), and country of residence.

Data collection

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap—Research Electronic Data Capture tools hosted at The University of Melbourne. Baseline HOMESIDE data were used in this analysis.

Outcome variable

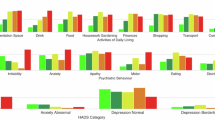

The level of depressive symptom severity of people living with dementia was captured by asking the caregiver to rate the person with dementia’s severity of depressive symptoms using the Montgomery—Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). The MADRS is a 10-item measure, with each item’s score ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (severe symptoms). Total scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. If two or fewer items had missing responses in the MADRS questionnaire, each missing response was replaced by the mean of the participant’s responses. If more than two items had missing responses, a score was not calculated and was treated as missing data12. The MADRS is a screening tool for depressive symptoms rather than a diagnostic instrument for clinical depression. Elevated MADRS scores indicate the presence and severity of depressive symptoms but do not constitute clinical depression diagnoses.

Exposure variables

Four key exposure variables were examined in this study. Information about all exposure variables was collected through structured interviews with caregivers and verified with available medical records where possible. Stage of dementia was defined as ‘early onset’ if symptoms appeared before age 65 years or ‘late onset’ if symptoms appeared at age 65 years or later, based on caregiver reports of symptom onset. Type of dementia was categorized into three groups: Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (including Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, and Lewy body disease), vascular and mixed dementias (including vascular dementia and mixed dementia), and other dementia types (including other or unknown types), as reported in participants’ medical diagnoses and confirmed by caregivers.

Severity of dementia was assessed by trained research staff using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), a 30-point questionnaire administered directly to participants with dementia. Based on MMSE scores, participants were categorized into four groups: mild dementia (scores 24–30], mild-moderate dementia (scores 19–23), moderate dementia (scores 10–18) and severe dementia (scores < 10). Some participants lacked an MMSE score at baseline due to inability to complete the assessment. In these cases, participants were either clinically categorized as having severe impairment based on assessments by the participant’s treating clinician (as documented in medical records) or classified as not assessable when no clinical judgment was available. This classification approach was determined a priori by the research team and allowed a substantial proportion of those with missing MMSE scores to be included in the analysis13.

Country of residence included the five countries from which HOMESIDE participating dyads were recruited: Australia, United Kingdom, Norway, Poland, and Germany.

Other covariates

Baseline data on age (years; continuous), sex (male/female), marital status (married/de facto, single, divorced, separated or widowed), highest level of education (low [up to high school]/medium [trade, community or TAFE (Technical and Further Education)]/high [university degree]), last occupation (management positions/professionals/working class), main source of income (own income or savings/pension/government benefits/family help/other) and length of time having dementia (years) were all collected for the participants with dementia.

Sample size

The HOMESIDE trial was powered to demonstrate a superior effect of music intervention compared to usual care10. The sample size for this secondary exploratory analysis was determined by the number of participants with dementia who had complete data on the key analysis variables (stage of dementia, type of dementia, severity of dementia, country of residence, MADRS score and potential confounders) at baseline.

Statistical analysis

Data were summarized using descriptive statistics (e.g., mean and standard deviation [SD] or median and 25th–75th percentile for continuous variables, number and percentage for categorical variables). Baseline characteristics were compared between those included in the analysis (i.e., the complete case sample) and those omitted due to missing data for one or more analysis variables. Separate linear regression models were fitted to examine differences in average level of depressive symptom severity of the person with dementia (outcome) by each of four exposure groups: (i) stage of dementia, (ii) type of dementia, (iii) severity of dementia, and (iv) country of residence. Models were fitted with and without adjustment for confounders and prognostic variables. To select the confounders for inclusion in the adjusted models from the list of other covariates, we developed directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) informed by expert knowledge (AAB, EJ and FB) and existing literature in the field (see Appendix A). In addition, the adjusted model included prognostic variables of the outcome (caregiver’s depression, marital status of the person with dementia, length of time with dementia). As this is an exploratory analysis, no multiplicity adjustment was undertaken. Results are presented as estimates and 95% confidence intervals to enable assessment of the strength of relationships, rather than with a focus on statistical significance.

All statistical analysis was undertaken using Stata version 16.1.

Results

Among 432 randomized participants in the HOMESIDE study, 376 (87%) had complete data on the key analytical variables and were considered in the analysis presented.

Comparisons between the omitted participant sample and complete case sample showed that in general, characteristics of the two samples were roughly comparable. However, in the omitted sample a higher percentage were female (61% vs. 43%) and mean depressive symptom severity of the person with dementia was higher (19.7 [SD = 8.6] vs. 16.1 [SD = 7.6]) (see Appendix C for detailed comparison).

Descriptive characteristics for the 376 participants used in the analysis are provided in Table 1. Participants were recruited from the United Kingdom (103/376, 27%), Australia (90/376, 24%), Germany (90/376, 24%), Norway (53/376, 14%) and Poland (40/376, 11%). A majority had late onset dementia (309/376, 82%), Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia diagnosis (229/376, 61%) and moderate or severe dementia (216/376, 57%). The mean depressive symptom score of the participant with dementia was 16.1 (SD = 7.6), ranging from 2 to 41.

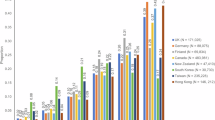

Results from the linear regression models are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1. Findings from adjusted analyses showed higher mean depressive symptom scores among those with severe dementia compared to those with mild dementia (MMSE 24–30) (3.78, 95% CI 1.60–5.96, p = 0.001).

Estimated mean difference (95% CI) in depression from unadjusted and adjusted linear regression models. Data points represent mean differences in depressive symptom levels with 95% confidence intervals. Positive values indicate higher depressive symptom levels compared to the reference group, negative values indicate lower depressive symptom levels. (a) Stage of dementia (reference: early); (b) type of dementia (reference: Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias; vascular or mixed dementia; or other types of dementia); (c) severity of dementia (reference: mild dementia [MMSE 24–30]); and (d) country (reference: Australia). Early-onset and late-onset dementia consisted of participants with any form of dementia in people under the age of 65 and aged 65 and older, respectively. Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias consisted of participants with Alzheimer’s disease, Frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body disease. Vascular or mixed consisted of participants with vascular or mixed dementia, while other consisted of other or unknown dementia.

Estimated mean differences between those with mild-moderate dementia (− 0.05, 95% CI − 2.30 to 2.20, p = 0.967) or moderate dementia (0.51, 95% CI − 1.69 to 2.72, p = 0.648) compared to mild dementia (MMSE 24–30) were much smaller, with wide confidence intervals including both negative and positive values. Estimated mean depressive symptom severity was lower for those with late-stage compared to early-stage dementia (− 0.86, 95% CI − 3.74 to 2.03, p = 0.560) and those with ‘other’ type of dementia compared to Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (− 1.26, 95% CI − 3.27 to 0.75, p = 0.219). However, confidence intervals were wide, ranging from negative to positive values.

There were country differences in depressive symptom severity level of people with dementia at baseline. Mean depressive symptom scores were lower in the United Kingdom (− 2.41, 95% CI − 4.49 to − 0.34, p = 0.023), Germany (− 2.51, 95% CI − 4.63 to − 0.40, p = 0.020), and Norway (− 4.93, 95% CI − 7.39 to − 2.47, p < 0.001) compared to Australia. Estimated mean depressive symptom severity was higher in Poland compared to Australia (1.15, 95% CI − 1.71 to 4.02, p = 0.428); however, confidence intervals were wide and ranged from negative to positive values.

Discussion

This cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from the HOMESIDE trial examined differences in depressive symptom severity levels in community-dwelling people living with dementia by dementia characteristics and country of residence. Our findings provide valuable insights into factors associated with depressive symptoms in this population.

Most notably, depressive symptom severity level was higher among those with severe dementia compared to those with mild dementia (MMSE 24–30), with clinically important differences observed (3.78, 95% CI 1.60–5.96). However, depressive symptom levels did not appear to differ between those with either mild-moderate dementia or moderate dementia compared to mild dementia. This difference exceeds the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the MADRS scale, which has been estimated at 1.6 to 1.9 points in previous research14,15,16, suggesting a meaningful clinical impact. This finding suggests that cognitive impairment severity may be associated with depressive symptom development among people with dementia, although this relationship could also reflect methodological limitations including the decreased validity of MADRS as dementia progresses and increased reliance on caregiver observations rather than participant self-rating. This finding aligns with previous research by Enache et al.6, who reported varying depression prevalence (20–60%) across different stages of dementia, with higher rates typically observed in more advanced cases, as well as with more recent studies showing similar patterns17,18.

The relationship between severe dementia and depressive symptoms may reflect the increasing awareness of functional decline, growing dependency, and social isolation that often accompany the progression of dementia. These factors have been identified as significant contributors to depression in older adults with cognitive impairment8,19. Additionally, as cognitive impairment progresses, the ability to engage in meaningful activities and maintain social connections diminishes, potentially exacerbating depressive symptoms.

Interestingly, our finding of higher depressive symptom levels in those with severe dementia contrasts with some established patterns in the literature. Traditionally, depression has been reported as more prevalent in early to moderate stages of dementia, with symptoms often appearing to decrease in advanced stages20,21. This apparent decrease in later stages is frequently attributed to challenges in detecting and assessing depressive symptoms due to diminished communication abilities and reduced self-awareness in severe dementia. The higher depressive symptom levels we observed in severe dementia may reflect the specific characteristics of our community-dwelling sample, the sensitivity of the MADRS scale in capturing observable symptoms even in advanced dementia, or the enhanced ability of caregivers in home settings to recognize subtle changes in mood and behavior compared to institutional settings. This unexpected finding warrants further investigation into the manifestation and detection of depressive symptoms across the continuum of cognitive decline.

We observed clinically important lower depressive symptom levels in Norway (− 4.93 points, 95% CI − 7.39 to − 2.47), Germany (− 2.51 points, 95% CI − 4.63 to − 0.40), and the United Kingdom (− 2.41 points, 95% CI − 4.49 to − 0.34) compared to Australia. These findings support earlier research by Rai et al.22, who demonstrated marked differences in depression prevalence across countries due to varying thresholds of clinically relevant symptoms in different cultural contexts and differences in reporting mental health concerns. More recent evidence from Arias-de la Torre et al.23 further corroborates substantial variation in depression prevalence across 27 European countries, with rates ranging from 2.6% in the Czech Republic to 10.3% in Iceland, highlighting the importance of considering geographical and sociopolitical contexts when interpreting depression data.

The particularly low depressive symptom levels in Norway may reflect multiple interconnected factors, including their comprehensive healthcare systems, strong social safety nets, cultural attitudes toward aging and dementia, and family support structures. While Livingston et al.7 highlighted that healthcare funding and early detection systems can influence dementia outcomes, our findings suggest that country differences likely involve complex interactions between healthcare access, socioeconomic factors, cultural contexts, and family caregiving traditions. Norway’s well-funded public healthcare system and relatively low levels of socioeconomic inequality may contribute to better mental health outcomes among people with dementia24, however, cultural factors and community attitudes toward dementia care may also play important protective roles25.

Regarding Germany, our findings of lower depressive symptom levels compared to Australia are consistent with the context of community-dwelling people with dementia. Tesky et al.26 reported that while the prevalence of late-life depression in Germany is around 7.2% in the general older population, it rises dramatically to 42.9% among nursing home residents. Since HOMESIDE Germany included only people living with dementia at home, this may explain the lower depressive symptom levels observed in our sample compared to what might be expected in institutional care settings. This underscores the importance of considering care setting when interpreting depression data across countries. These differences might also reflect variations in cultural perceptions of dementia and depression, access to specialized dementia care, caregiver support programs, and socioeconomic factors. Freeman et al.9 demonstrated that individual socioeconomic status significantly influences depression outcomes across European countries, highlighting the importance of socioeconomic factors at the personal level rather than solely healthcare system characteristics.

Our analysis revealed no significant differences in depressive symptom levels between dementia types or early versus late onset. This lack of association suggests that depressive symptoms may develop independently of dementia etiology or age of onset. This finding has important clinical implications, indicating a need for consistent depression screening across all dementia types and stages. The absence of evidence of differences in depressive symptoms by dementia type contrasts with some previous studies suggesting variations in neuropsychiatric symptoms across different dementia etiologies. However, it aligns with the biological mechanisms shared between depression and various types of dementia, including vascular disease, hippocampal atrophy, β-amyloid deposits, and inflammatory alterations5, which may explain why depressive symptoms manifest across different dementia types.

Clarification of dementia stage versus severity

It is important to clarify that our analysis examined two distinct clinical dimensions of dementia that are often conflated but represent independent characteristics. Stage of dementia refers to the age of symptom onset (early-onset < 65 years versus late-onset ≥ 65 years)1,27, while severity of dementia reflects current cognitive impairment level as measured by MMSE scores13. These variables showed different patterns of association with depressive symptoms in our study. Our finding that early-onset dementia was associated with slightly higher (though not statistically significant) depressive symptom levels compared to late-onset dementia may reflect the greater psychological impact of developing dementia at a younger age, when individuals are more likely to be employed, have dependent children, or experience greater life disruption28,29. Conversely, our finding that severe dementia was strongly associated with higher depressive symptom levels regardless of age of onset suggests that current functional capacity and awareness of cognitive decline play important roles in depressive symptom development2,18,28. This distinction has important clinical implications, as both younger individuals at dementia onset and those with more severe current dementia may benefit from targeted depressive symptom screening and intervention, albeit for different reasons17,18.

Study limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, this was exploratory secondary analyses of baseline trial data which may be underpowered to detect relationships between each covariate and depression. Second, we lacked data on some confounding factors, including heart disease and diabetes, which could influence both dementia and depression. This means estimated differences in means may be biased by residual confounding. Third, the characteristics of participants excluded due to missing data differed somewhat from the analyzed sample, with higher percentages of females and higher depressive symptom levels in the omitted group, potentially affecting the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, as this was a cross-sectional analysis, we cannot establish causality between dementia characteristics and depressive symptom levels. The relationship between cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms may be bidirectional, with each condition potentially exacerbating the other. While our analysis examined the influence of dementia severity on depressive symptom levels, depressive symptoms themselves may contribute to the progression and severity of dementia. Existing evidence suggests that depression can accelerate cognitive decline through various biological mechanisms, including chronic inflammation, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation, vascular pathology, and reduced neuroplasticity5. The psychological burden of depression may also reduce cognitive reserve and participation in cognitively stimulating activities, further exacerbating cognitive impairment. This complex bidirectional relationship underscores the importance of addressing both conditions simultaneously in clinical practice. Fourth, our analysis did not include medication use as a covariate, which may have influenced the results. Psychotropic medications, commonly prescribed based on factors such as dementia onset, severity, and type, can independently affect depressive symptoms. While examining medication effects would provide valuable insights, the complexity and resource-intensive nature of comprehensive medication analysis in large datasets made this impractical for the HOMESIDE study. Future studies with dedicated resources for medication analysis could help clarify the relationship between pharmacological interventions, dementia characteristics, and depressive symptom levels.

Proxy reporting and MADRS limitations

Our study also has limitations related to depression assessment in dementia that require careful consideration. Caregiver-rated MADRS scores may be influenced by caregiver burden, stress levels, and their own mental health status30,31. While studies show caregiver accuracy in recognizing depression with sensitivity of 0.65 and specificity of 0.5832, this level of accuracy, though imperfect, still provides valuable clinical information, particularly when combined with standardized assessment protocols as used in HOMESIDE. Discrepancies between patient and caregiver ratings are particularly associated with increased caregiver burden rather than patient functioning levels28,33. However, cohabiting caregivers in our study had daily opportunities to observe behavioral changes and mood patterns, potentially providing insights unavailable through brief clinical assessments.

Despite these limitations, proxy reporting remains the most feasible approach for depression assessment in moderate to severe dementia, where self-report becomes increasingly unreliable. Our entire HOMESIDE sample consisted of people with dementia who had clinically significant BPSD, as this was an inclusion criterion for the original trial. While no depression rating scale, including MADRS, has been fully validated specifically in people with advanced dementia who also have significant BPSD34, MADRS remains one of the most widely used and psychometrically sound depression rating scales available. MADRS has shown utility in early-onset dementia for distinguishing depressed from non-depressed patients35, and our findings of systematic patterns across countries and severity levels suggest meaningful signal detection despite measurement challenges.

Many MADRS items may be confounded by core dementia symptoms and other BPSD, particularly apathy, sleep disturbance, and concentration difficulties36,37. However, the consistency of our findings across different countries and the clinically meaningful effect sizes observed suggest that our results capture genuine patterns of depressive symptomatology rather than random measurement error. While there is no universal agreement on depression diagnostic criteria in advanced dementia, particularly when BPSD is present, standardized caregiver-rated assessments like MADRS provide the best available evidence for understanding depressive symptom patterns in this population. Our study’s strength lies in its large, international sample and standardized assessment procedures, which help minimize bias while acknowledging the inherent challenges of depression measurement in dementia. Future research would benefit from using validated instruments specifically designed for cognitively impaired populations, alongside careful consideration of proxy reporting limitations. Until such instruments are developed and validated, studies like ours provide important insights into depressive symptom patterns that can inform clinical practice and guide future research directions. The association between dementia severity and higher MADRS scores may reflect decreasing validity of the MADRS as dementia progresses, with increased reliance on caregiver observations potentially introducing systematic bias rather than reflecting true increases in depressive symptoms. As cognitive impairment advances, the ability to provide accurate self-reports diminishes, making proxy ratings more susceptible to interpretation bias and confusion between depressive symptoms and core dementia symptoms. While our findings show systematic patterns across countries and severity levels, suggesting meaningful signal detection, the possibility that our observed association reflects measurement artifacts rather than genuine clinical relationships cannot be definitively excluded based on our cross-sectional data. Future longitudinal studies designed specifically to address these measurement validity questions are needed to clarify whether higher MADRS scores in severe dementia represent true symptom increases or methodological limitations.

Selection and generalizability limitations

Our study sample demonstrated characteristics suggesting higher social capital, including higher educational levels and predominantly urban/suburban residence. This likely reflects self-selection bias, as individuals with greater health awareness, higher socioeconomic status, and stronger family support networks are more likely to volunteer for research participation. People with dementia who agreed to participate in our study, along with their caregivers, may represent a subset of the population with better access to healthcare information, greater engagement with medical services, and more stable living situations.

This selection bias has important implications for generalizability. Our findings may not extend to people with dementia who have lower educational attainment, live in more socially isolated circumstances, have limited health literacy, or rely primarily on formal care services rather than family caregivers. Additionally, the study was conducted primarily in urban and suburban settings, which may limit generalizability to rural populations who may have different access to healthcare services, social support systems, and cultural attitudes toward research participation. The higher socioeconomic and educational profile of our participants, while unintentional, may have influenced depression ratings, help-seeking behaviors, and responses to interventions in ways that differ from more diverse populations.

Missing data and measurement issues

Our strategy of averaging responses for missing MADRS items may lead to score inflation, particularly if caregivers consistently rate certain items higher due to confusion with dementia-related symptoms. While caregiver depression was collected as part of the HOMESIDE baseline assessment and included as a prognostic variable in our regression models, other potentially important caregiver characteristics such as caregiver burden, employment status, and mental health beyond depression were not incorporated into our analyses. Future studies should examine the broader spectrum of caregiver factors that may influence proxy-rated depression measures, as these characteristics may significantly affect symptom ratings and could help explain additional variability in depression scores.

Clinical implications

Our findings highlight several important implications for clinical practice and healthcare policy. First, they emphasize the need for regular depression screening, particularly in individuals with severe cognitive impairment. Early recognition and treatment of depressive symptoms in dementia patients can delay cognitive decline, reduce symptom severity, and improve quality of life8. Second, our results suggest potential insights from countries showing lower depressive symptom rates in our sample, particularly Norway. Our findings highlight the importance of examining country-specific factors that may influence depressive symptoms in people with dementia. Healthcare policies that prioritize comprehensive dementia care, including psychological support and caregiver assistance, may help reduce depressive symptom burden in this vulnerable population. Further comparative research is needed to identify specific elements of care systems associated with better mental health outcomes in dementia. Third, interventions should be adapted to address the specific needs of individuals with different levels of cognitive impairment, with particular attention to those with severe impairment who demonstrated higher depressive symptom levels in our study. Recent evidence supports the effectiveness of person-centered care approaches in reducing depressive symptoms in people with dementia. A meta-analysis by Kim and Park38 examining 19 studies with 3,985 participants demonstrated that person-centered care not only reduces agitation but also significantly decreases depressive symptoms, suggesting that tailoring interventions to individual needs can be particularly effective.

Future research should focus on understanding the mechanisms linking severe cognitive impairment with depressive symptoms, investigating causal relationships through longitudinal studies, and exploring the specific factors contributing to country differences in depressive symptom prevalence. Additionally, intervention studies examining the effectiveness of different approaches based on dementia severity would help develop tailored strategies for depressive symptom management in this population. Investigations into healthcare system factors that contribute to better outcomes in certain countries would be valuable for informing policy development. Finally, studies examining the role of cultural factors, stigma, and reporting differences in explaining international variations in depressive symptom rates would enhance our understanding of this complex relationship.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that dementia severity, particularly severe cognitive impairment, is strongly associated with higher depressive symptom levels, while there was no similar evidence for dementia type or stage. The marked differences in depressive symptom levels between countries, with notably lower rates in Norway, Germany, and the United Kingdom compared to Australia, suggests that healthcare system organization and access to comprehensive care may play crucial roles in managing depressive symptoms in people with dementia. While Poland was also included in our study, depressive symptom levels there did not differ significantly from those in Australia. These results highlight the importance of regular depression screening in severe cognitive impairment, examining successful elements from healthcare systems in countries with lower depressive symptom rates compared to Australia, particularly the Norwegian model, and development of targeted interventions considering both dementia severity and healthcare system context. Future research should focus on understanding the mechanisms linking severe cognitive impairment with depressive symptoms and investigating the specific healthcare system factors contributing to better outcomes in certain countries.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sachdev, P. S. et al. Classifying neurocognitive disorders: the DSM-5 approach. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 10(11), 634–642. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.181 (2014).

Zubenko, G. S. et al. A collaborative study of the emergence and clinical features of the major depressive syndrome of Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Psychiatry. 160, 857–866. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.857 (2003).

Cherbuin, N., Kim, S. & Anstey, K. J. Dementia risk estimates associated with measures of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 5(12), e008853. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008853 (2015).

Santabarbara, J., Sevil-Perez, A., Olaya, B., Gracia-García, P. & López-Antón, R. Clinically relevant late-life depression as risk factor of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Rev. Neurol. 68(12), 493–502. https://doi.org/10.33588/rn.6812.2018398 (2019).

Sacuiu, S. et al. Chronic depressive symptomatology in mild cognitive impairment is associated with frontal atrophy rate which hastens conversion to Alzheimer dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 24(2), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2015.03.006 (2016).

Enache, D., Winblad, B. & Aarsland, D. Depression in dementia: epidemiology, mechanisms, and treatment. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 24(6), 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32834bb9d4 (2011).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 396(10248), 413–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6 (2020).

Bennett, S. & Thomas, A. J. Depression and dementia: cause, consequence or coincidence?. Maturitas 79(2), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.05.009 (2014).

Freeman, A. et al. The role of socio-economic status in depression: results from the COURAGE (aging survey in Europe). BMC Public Health 16, 1098. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3638-0 (2016).

Baker, F. A. et al. Home-based family caregiver-delivered music and reading interventions for people living with dementia (HOMESIDE trial): an international randomised controlled trial. eClinicalMedicine. 65, 102224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102224 (2023).

Baker, F. A. et al. Recruitment approaches and profiles of consenting family caregivers and people living with dementia: A recruitment study within a trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 31(32), 101079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2023.101079 (2023).

Montgomery, S. A. & Åsberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry. 134, 382–389. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.134.4.382 (1979).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12(3), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 (1975).

Duru, G. & Fantino, B. The clinical relevance of changes in the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale using the minimum clinically important difference approach. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 24(5), 1329–1335. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079908X291958 (2008).

Masson, S. C. & Tejani, A. M. Minimum clinically important differences identified for commonly used depression rating scales. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 66(7), 805–807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.01.010 (2013).

Riedel, M. et al. Response and remission criteria in major depression—a validation of current practice. J. Psychiatr. Res. 44(15), 1063–1068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.03.006 (2010).

Goodarzi, Z. et al. Guidelines for dementia or Parkinson’s disease with depression or anxiety: a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 16(1), 244. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-016-0754-5 (2016).

Asmer, M. S. et al. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of major depressive disorder among older adults with dementia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 79(5), 17r11772. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17r11772 (2018).

Opdebeeck, C., Quinn, C., Nelis, S. M. & Clare, L. Is cognitive lifestyle associated with depressive thoughts and self-reported depressive symptoms in later life?. Eur. J. Ageing 13(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-015-0359-7 (2016).

Aalten, P., de Vugt, M. E., Jaspers, N., Jolles, J. & Verhey, F. R. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Part I: findings from the two-year longitudinal Maasbed study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 20(6), 523–530. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1316 (2005).

Lyketsos, C. G. et al. Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am. J. Psychiatry. 157(5), 708–714. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.708 (2000).

Rai, D., Zitko, P., Jones, K., Lynch, J. & Araya, R. Country- and individual-level socioeconomic determinants of depression: multilevel cross-national comparison. Br. J. Psychiatry. 202(3), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112482 (2013).

Arias-de la Torre, J. et al. Prevalence and variability of current depressive disorder in 27 European countries: a population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 6(10), e729–e738. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00047-5 (2021).

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Norway: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU. (OECD Publishing, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1787/6871e6c4-en.

Anttonen, A. & Sipilä, J. Universalism in the British and Scandinavian social policy debates. In Welfare State, Universalism and Diversity (eds Anttonen, A. et al.) 16–41 (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2012).

Tesky, V. A. et al. Depression in the nursing home: a cluster-randomized stepped-wedge study to probe the effectiveness of a novel case management approach to improve treatment (the DAVOS project). Trials 20(1), 424. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3534-x (2019).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed. (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Conde-Sala, J. L. et al. Effects of anosognosia and neuropsychiatric symptoms on the quality of life of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a 24-month follow-up study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 31(2), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4298 (2016).

Hugo, J. & Ganguli, M. Dementia and cognitive impairment: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 30(3), 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2014.04.001 (2014).

Pinquart, M. & Sörensen, S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging. 18(2), 250–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250 (2003).

Schulz, R. & Martire, L. M. Family caregiving of persons with dementia: prevalence, health effects, and support strategies. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 12(3), 240–249 (2004).

Watson, L. C., Lewis, C. L., Moore, C. G. & Jeste, D. V. Perceptions of depression among dementia caregivers: findings from the CATIE-AD trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 26(4), 397–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2539 (2011).

Sneeuw, K. C. et al. The use of significant others as proxy raters of the quality of life of patients with brain cancer. Med. Care. 35(5), 490–506. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199705000-00006 (1997).

Wetzels, R. B., Zuidema, S. U., de Jonghe, J. F., Verhey, F. R. & Koopmans, R. T. Determinants of quality of life in nursing home residents with dementia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 29(3), 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1159/000280437 (2010).

Leontjevas, R., van Hooren, S. & Mulders, A. The Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale and the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia: a validation study with patients exhibiting early-onset dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 17(1), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e31818b4111 (2009).

Spalletta, G. et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and syndromes in a large cohort of newly diagnosed, untreated patients with Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 18(11), 1026–1035. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d6b68d (2010).

Aalten, P. et al. Consistency of neuropsychiatric syndromes across dementias: results from the European Alzheimer Disease Consortium. Part II. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 25(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000111082 (2008).

Kim, S. K. & Park, M. Effectiveness of person-centered care on people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Interv. Aging. 12, 381–397. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S117637 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to all participants who contributed to the HOMESIDE study and to all researchers, clinicians, and staff involved in data collection across the five participating countries.

Funding

This research was supported by the Joint Programs for Neurodegenerative Diseases (JPND), with funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia (GNT1169867), Norwegian Research Council (Project number 298995), Federal Ministry of Education and Research Germany (01ED1901), The National Centre for Research and Development, Poland (JPND/04/2019), and Alzheimer’s Society, UK (grant no. 462). In the United Kingdom, the study received additional support from the NIHR Clinical Research Network.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.B., E.J., and F.A.B. conceived and designed the study. V.P.S., K.E.L., and S.B. conducted the statistical analyses. A.A.B. and E.J. drafted the initial manuscript. A.S.R., M.H.H., K.A.S., H.O.M., J.T., T.W., T.V.S. contributed to data collection and interpretation. F.A.B. supervised the overall study. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The HOMESIDE study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethics approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee at The University of Melbourne (Ethics ID: 1852845) and corresponding ethics committees in all participating countries: Australia Human Ethics Sub-Committee approval no. 1852845, the United Kingdom approval no. 19/EE/0177, Poland approval no. 186/KBL/OIL/2019, German approval no. DGP 19-013, Norwegian Centre for Research Data (Ref 502736), and Norwegian REK Medical and Research Ethics (Ref 2019/941). All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bukowska, A.A., Janus, E., Soo, V.P. et al. Relationship between dementia diagnostic characteristics and severity of depressive symptoms in a cross-sectional analysis of HOMESIDE baseline data. Sci Rep 15, 36643 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20385-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20385-z