Abstract

Karst regions are ecologically fragile and highly sensitive to both natural and anthropogenic disturbances, necessitating accurate and quantitative assessments of ecological quality and its driving forces. This study introduces a Karst-Specific Remote Sensing Ecological Index (KRSEI), a novel model tailored to the unique environmental conditions of karst landscapes. Using Guizhou Province in Southwest China as the study area, the KRSEI was applied to MODIS remote sensing data from 2002 to 2022, and further integrated with Theil–Sen–Mann–Kendall (Sen–MK) trend analysis and an optimized parameter geographical detector to explore spatiotemporal patterns and key driving mechanisms of ecological change. The findings reveal that: (1) KRSEI achieves higher information entropy and image contrast than traditional RSEI, effectively reflecting ecological heterogeneity; (2) ecological quality remained moderately stable (KRSEI ≈ 0.6) over two decades, with regions of lower ecological status exhibiting a “rise–decline–rebound” trajectory, and 58.25% of the area showing an improving trend; and (3) vegetation cover, precipitation, and population density were identified as dominant drivers, with most factor interactions showing synergistic (bivariate enhancement) effects. This research offers a robust methodological framework for ecological monitoring in karst regions and provides scientific support for targeted ecological protection and sustainable regional development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Karst areas are highly susceptible to disturbances from both natural factors and human activities due to their unique geological and geomorphic features, fragile ecosystem structure, and low environmental carrying capacity1,2,3. The karst region in Southwest China is one of the most extensively distributed and well-developed karst landscapes in the world, where ecological degradation is particularly severe. In recent years, with the continuous advancement of China’s ecological civilization strategy, environmental protection and restoration in karst areas have become a strategic national priority. Conducting scientific and accurate assessments of ecological quality in karst regions4,5 is essential for identifying ecological risks, enhancing the comprehensive control of rocky desertification6,7,8, and guiding ecological conservation and restoration. It forms a critical foundation for achieving regional sustainable development.

In recent years, remote sensing technology has been increasingly applied in ecological environment monitoring. The Remote Sensing Ecological Index (RSEI), as a comprehensive evaluation model that integrates multi-source remote sensing data to reflect ecosystem conditions, has been widely used for quantitative assessments of regional ecological quality. Originally proposed by Xu Hanqiu and colleagues9,10,11, the RSEI model has been extensively employed in various ecological contexts such as urban areas, agricultural zones, and mining regions, owing to its easy data acquisition, streamlined computational process, and intuitive results10,12,13,14,15,16,17. As research has progressed, the limitations of the traditional RSEI model in specific ecological regions have become increasingly apparent. In areas with complex terrain or unique ecological structures—such as mountainous zones, karst landscapes, deserts, and mining areas—the RSEI fails to fully capture region-specific ecological characteristics. To enhance the regional adaptability of the model, numerous scholars have proposed optimizations and modifications to the RSEI18,19,20,21,22,23,24. For instance, in plateau regions, elevation and slope factors have been introduced to improve sensitivity to topographic variations. In mining areas, modified models incorporating pollution indices and surface disturbance indicators have been developed. With the widespread use of multi-source remote sensing data—such as MODIS, Landsat, and Sentinel imagery—along with advances in computing technology and artificial intelligence algorithms, the construction approaches, indicator selection, and analytical methods of the RSEI model have become increasingly diverse25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Some studies have begun to incorporate machine learning techniques into the weighting and validation processes of ecological indices to further enhance model accuracy and practical applicability33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. Research on remote sensing ecological indices has evolved from early single-metric evaluations to comprehensive, multi-dimensional, and scale-adaptive analyses, providing more scientific and efficient technical support for ecological monitoring and assessment.

Although the RSEI has been widely applied in regional ecological assessments due to its general applicability and ease of use, it primarily relies on conventional indicators such as NDVI, humidity, dryness, and land surface temperature. This reliance makes it difficult to accurately reflect the ecological characteristics of karst regions, including complex landforms, severe rocky desertification, and unique vegetation structures, thereby limiting its applicability in such ecosystems. Most current studies remain limited in spatial and temporal scope, particularly in aspects such as adaptive weighting of indicators, scale compatibility, and the analysis of long-term ecological trends and the interactions between natural and anthropogenic driving factors. Therefore, the development of an improved remote sensing ecological index model with enhanced topographic sensitivity and ecological representativeness tailored to the unique characteristics of karst ecosystems holds significant theoretical and practical value.

This study proposes an improved remote sensing ecological index, KRSEI, tailored for karst regions by integrating four key ecological indicators: the normalized difference mountain vegetation index (NDMVI), the wetness component index (WET), the rocky desertification index (SIRF), and the land surface temperature index (LST). Using Guizhou Province as a case study, the model’s validity and superiority were evaluated based on long-term MODIS data from 2002 to 2022. Trend analysis and the geographical detector method were employed to comprehensively reveal the spatiotemporal dynamics of ecological quality and its dominant driving forces in the province. The results provide a scientific basis for comprehensive rocky desertification control, ecological restoration strategies, and regional ecological management in karst areas.

Materials and methods

Study area

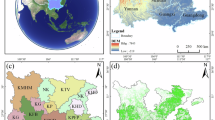

This study focuses on Guizhou Province as the primary research area, which is located between approximately103°36′E–109°35′E and24°37′N–29°13′N (Fig. 1), covering a total area of 176,167 km². The region is representative and diverse in terms of natural environment, intensity of human activities, and implementation of ecological restoration policies, making it suitable for multi-scale and multi-temporal remote sensing-based ecological quality assessments. Guizhou is situated on the eastern part of the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau, which forms the second step of China’s topography. It lies in a typical subtropical mountainous karst region, characterized by rugged terrain sloping from west to east and significant vertical relief, with an average elevation exceeding 1,100 m. Guizhou is one of the most representative karst regions in the world, with karst landforms covering more than 62% of its area. Exposed karst landscapes are widely distributed, forming a variety of landforms such as peak clusters, depressions, sinkholes, underground rivers, and caves, features indicative of a typical karst ecosystem. The province experiences a subtropical humid monsoon climate, with an average annual temperature of around 15 °C and annual precipitation ranging from 1,000 to 1,400 mm. Rainfall and temperature peaks coincide, resulting in high humidity, limited sunlight, and a rainy season that typically lasts from May to September. Due to concentrated rainfall, vegetation destruction, and soil erosion, the process of rocky desertification is particularly pronounced in Guizhou. In recent years, rapid socio-economic development and excessive resource exploitation have triggered a series of ecological issues, including vegetation degradation, biodiversity loss, and the expansion of rocky desertification, leading to the continuous deterioration of ecological environmental quality.

Overview map of the study area in Guizhou province. The figure was created using ArcGIS 10.6 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/home).

Data sources

This study utilizes multi-source remote sensing imagery and geospatial datasets spanning the years 2002 to 2022. The remote sensing data are derived from the MODIS series products, obtained via the LAADS DAAC portal (https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov). The MOD09A1 product provides surface reflectance data with an 8-day temporal resolution and 500 m spatial resolution, and is primarily used to derive vegetation greenness (NDMVI), surface moisture (WET), and rocky desertification index (SIRF). The MOD11A2 product provides land surface temperature (day and night) and emissivity data, with the same 8-day temporal resolution and a spatial resolution of 1,000 m. It is used to calculate the land surface temperature index (LST). Additional spatial data include the 2002–2022 LandScan Global Population Dataset, provided by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), U.S. Department of Energy (https://landscan.ornl.gov/), and used to calculate population density in the study area. Monthly precipitation and near-surface air temperature datasets at 1-km resolution for China were obtained from the National Earth System Science Data Center (https://www.geodata.cn) and used to calculate precipitation and temperature for the study area. The 30-m resolution CLCD (2002–2022) land cover dataset for China was obtained from the National Cryosphere Desert Data Center (https://www.ncdc.ac.cn) and used to extract land use types in the study area. The 30-m resolution SRTM DEM product was obtained from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov) and used to compute elevation and slope across the study area.

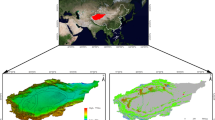

Methodology

This study develops a karst-specific remote sensing ecological index (KRSEI) to address the complex topography and fragile ecological conditions characteristic of Southwest China’s karst regions. The KRSEI integrates multiple improved ecological indicators—including vegetation greenness, moisture, rocky desertification, and land surface temperature—using principal component analysis (PCA). It is applied to analyze the spatiotemporal dynamics of ecological quality based on multi-temporal remote sensing data. The ecological quality trends in the study area are evaluated, and dominant driving factors are identified using an optimal-parameter geographic detector model. This enables a comprehensive understanding of the spatiotemporal evolution of the karst ecological environment and its driving mechanisms. The main technical framework of this study is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Construction of KRSEI

To construct a remote sensing ecological index (KRSEI) suitable for ecological environment assessment in karst regions, this study extends the traditional RSEI model by incorporating more region-specific ecological indicators. By considering the typical features of karst ecosystems—such as significant topographical variation, exposed surface bedrock, severe soil erosion, rocky desertification, and vegetation degradation—more representative indicators are introduced to construct the KRSEI, including the Normalized Difference Mountain Vegetation Index (NDMVI), the Wetness Component Index (WET), the Rocky Desertification Index (SIRF), and the Land Surface Temperature Index (LST). After normalization of the four indicators, principal component analysis (PCA) is applied to extract the first principal component (PC1) as a comprehensive representation of ecological quality, ultimately constructing the improved remote sensing ecological index (KRSEI). The KRSEI has a value range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better ecological quality.

-

(1)

The calculation methods for the specific indicators are as follows:

Vegetation Greenness Index. The Normalized Difference Mountain Vegetation Index (NDMVI) is derived from the NDVI and designed to mitigate the effects of topography by simultaneously reducing reflectance in both the near-infrared and red bands, making it effective for addressing the influence of complex terrain on mountain vegetation information42. For MOD09A1 imagery, the calculation formula is as follows:

$$NDMVI=\frac{{(b2 - b1)+(b{1_{min}} - b{2_{min}})}}{{(b2+b1) - (b{1_{min}}+b{2_{min}})}}$$(1)Wetness Component Index. The wetness component index (WET) is closely related to the ecological environment, as it reflects surface moisture conditions, particularly soil moisture, by utilizing the moisture component derived from the Hat Transform. It is widely applied in ecological monitoring43. The calculation formula is as follows:

$$\:\text{W}\text{E}\text{T}=\left(0.1147*b1\right)+\left(0.2489*b2\right)+\left(0.2408*b3\right)+\left(0.3132*b4\right)+\dots\:\left(0.3122*b5\right)+\left(0.6416*b6\right)+\left(0.5087*b7\right)$$(2)Rocky Desertification Index (SIRF). The index integrates four indicators: Bare Soil Index (SI), Building Index (IBI), Bedrock Exposure Index (RE), and Vegetation Coverage (FVC), and uses principal component analysis (PCA) to construct a rocky desertification evaluation model for extracting rocky desertification information44,45,46. The calculation formula is as follows:

$$SI=\frac{{(b6+b1) - (b2+b3)}}{{(b6+b1)+(b2+b3)}}$$(3)$$IBI=\frac{{\frac{{2*b6}}{{b6+b2}} - \frac{{b2}}{{b2+b1}} - \frac{{b4}}{{b4+b6}}}}{{\frac{{2*b6}}{{b6+b2}}+\frac{{b2}}{{b2+b1}}+\frac{{b4}}{{b4+b6}}}}$$(4)$$RE = \frac{{NDRI - NDRI_{{p95}} }}{{NDRI_{{p95}} - NDRI_{{p5}} }},\;{\text{and}}\;NDRI = \frac{{b7 - b2}}{{b7 + b2}}$$(5)$$FVC=\frac{{NDMVI - NDMV{I_{min}}}}{{NDMV{I_{max}} - NDMV{I_{min}}}}$$(6)Land Surface Temperature Index (LST). The heat index is closely linked to surface energy flux and is widely used in ecological risk assessment and related applications. In this study, the land surface temperature index (LST) was derived from MOD11A2 data using a retrieval method. The calculation formula is as follows:

$$LST=0.02*DN - 273.15$$(7) -

(2)

Construction of KRSEI.

Principal component analysis (PCA) reduces data dimensionality and filters out noise by concentrating multiple feature components into a few principal components47. The weights of each index are automatically determined based on their contributions to the first principal component (PC1). Results show that PC1 retains the highest amount of information among all components. The first two variables in PC1 (greenness and wetness) exhibit positive loadings, while the latter two (rocky desertification index and temperature) have negative loadings, which aligns with real-world conditions. Therefore, PC1 was used as the information source for KRSEI to ensure the objectivity and rationality of the results. Since the four ecological indicators differ in scale, they were normalized to a 0–1 range before principal component transformation. The normalization formula is as follows:

$$NI=\frac{{I - {I_{min}}}}{{{I_{max}} - {I_{min}}}}$$(8)In the formula, NI represents the normalized value, I denotes the original value of the indicator, and Imax, Imin refer to the maximum and minimum values of the indicator, respectively.

The initial ecological index (KRSEI0) was constructed using PC1, and is calculated as:

The result of KRSEI₀ was further normalized to obtain the final Karst Remote Sensing Ecological Index (KRSEI), which ranges from 0 to 1. Higher KRSEI values indicate better ecological quality.

In the formula, KRSEI0 min和KRSEI0 max represent the minimum and maximum values of KRSEI₀ for the target year, respectively. KRSEI denotes the final Karst Remote Sensing Ecological Index.

Trend analysis of ecological quality change

This study employed a combination of the Theil–Sen slope estimation and the Mann–Kendall test to analyze the temporal trends of KRSEI. The Theil–Sen estimator is a non-parametric method that does not require normality testing or data transformation48. It also makes no assumptions about autocorrelation in the time series and is effective in handling noise and outliers. It calculates the slopes of all pairwise combinations in the time series, and the median of these slopes (β) is taken as the overall trend. A value of β > 0 indicates ecological improvement, β < 0 indicates degradation, and β = 0 suggests a stable ecological condition. The Mann–Kendall test is used to assess the significance of the trend. It is robust against outliers and missing data, and is widely applied in trend detection of long-term time series49.

Optimized parameters geographical detector

The geographical detector is a statistical method used to detect spatial heterogeneity and reveal its underlying driving factors. By analyzing differences between geographic strata, it quantifies the extent to which explanatory variables influence dependent variables and has been widely applied in ecological assessment and ecosystem analysis. Traditional geographical detector methods require manual setting of classification schemes and class numbers for continuous variables, which often leads to poor discretization and strong subjectivity. The Optimized Parameters Geographical Detector (OPGD) model addresses this by computing and comparing the q-values under various classification methods and class numbers for each continuous variable50. A higher q-value indicates better discretization. This allows for more accurate detection of spatial heterogeneity in ecosystem services and quantifies the explanatory power of each influencing factor on this spatial heterogeneity. According to statistical guidelines, classification methods include equal interval, natural breaks, quantiles, geometric interval, and standard deviation classification. Using the GD package in R, all five classification methods were applied with class numbers ranging from 4 to 12. The combination yielding the maximum q-value was selected for spatial discretization.

Factor detection

Factor detection evaluates the extent to which an individual influencing factor (X) explains the spatial distribution of KRSEI. This is quantified using the q-value, which measures the explanatory power of a single factor.

In the formula, L represents the number of categories for factor X, Nh is the number of samples in category h, and N is the total number of samples in the study area. \(\:{\sigma\:}_{h}^{2}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}^{2}\) represent the variance within category h and the total variance, respectively. The q-value ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating stronger explanatory power.

Interaction detection

Interaction detection is used to identify the interaction effects between different influencing factors on the dependent variable. It evaluates how the combined influence of two factors affects the explanatory power for KRSEI, and determines whether the interaction is enhancing, weakening, or independent (e.g., nonlinear enhancement, independence). Specific interaction types are summarized in Table 1, where X₁ and X₂ represent distinct driving factors.

Results

Spatiotemporal distribution of ecological quality

To comprehensively reveal the evolution of ecological quality in Guizhou Province, this study classifies ecological quality into five levels based on KRSEI values: Inferior (I: 0.0–0.2), Poor (II: 0.2–0.4), Moderate (III: 0.4–0.6), Good (IV: 0.6–0.8), and Excellent (V: 0.8–1.0), with higher values indicating better ecological quality. Figure 3 presents the spatial distribution pattern of KRSEI in Guizhou Province from 2002 to 2022.

Spatial distribution of KRSEI results in Guizhou Province from 2002 to 2022. The figure was created using ArcGIS 10.6 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/home).

From the perspective of spatial distribution, the southeastern region of Guizhou Province exhibits relatively better ecological quality, primarily due to the region’s relatively gentle terrain, high proportion of forest and arable land, and stable ecosystem structure. In contrast, the central region of Guizhou Province, including Bijie City, Guiyang City, and Zunyi City, demonstrates relatively poorer ecological quality. This is attributed to factors such as significant topographic variations, complex land use, and prominent issues of rock desertification, which increase the vulnerability of the ecosystem.

Based on the statistical results of different ecological grade areas and their proportions in Table 2; Fig. 4, the ecological quality of Guizhou Province from 2002 to 2022 shows an evolution of “fluctuation—improvement—local degradation.” The average KRSEI value is generally around 0.6, reflecting an overall ecological level that remains slightly above moderate. The area of regions with ecological grades below “moderate” first increased, then decreased, and slightly rebounded, indicating that ecological quality changes are influenced by multiple factors. Between 2002 and 2009, weak ecological protection awareness and extensive resource development led to continuous environmental degradation. From 2010 to 2019, Guizhou Province made significant progress in ecological civilization construction, with policies and measures effectively implemented, resulting in notable improvements in ecological quality. From 2020 to 2022, however, some areas experienced notable ecological degradation due to excessive mineral resource exploitation and delayed ecological restoration, particularly in Xiuwang County of Guiyang and Huangping County in Qiandongnan Prefecture, where ecological destruction and environmental pollution were prominent. The NDMVI remained at a consistently high level throughout the study period, indicating relatively stable vegetation cover. In contrast, the WET index exhibited substantial fluctuations, followed by a rebound after 2015, reflecting a gradual improvement in moisture availability. The SIRF remained elevated in several years, suggesting that rocky desertification continues to pose a serious environmental challenge. The LST displayed a declining-then-rising trend, potentially linked to climate warming and localized urban heat island effects. Overall, ecological environmental quality in Guizhou Province showed significant spatial heterogeneity and phased temporal evolution, driven by a combination of natural geographic factors and anthropogenic activities.

Trend analysis of ecological quality

To reveal the temporal evolution of ecological quality in Guizhou Province from 2002 to 2022, this study employed the Theil-Sen slope estimation and the Mann-Kendall (M-K) test to analyze the time series of the Karst Remote Sensing Ecological Index (KRSEI). The Theil-Sen method, a robust non-parametric technique, effectively characterizes the direction and magnitude of temporal trends while being resistant to outliers. The Mann-Kendall test is widely used in long-term ecological and climatic studies due to its ability to detect the significance of trends without assuming data normality and its insensitivity to missing or extreme values. The results indicate that the ecological environment in Guizhou has generally improved over the past two decades, although localized areas have experienced degradation. As shown in Fig. 5; Table 3, regions exhibiting an increasing trend in KRSEI accounted for 58.25% of the study area. Among these, 56.71% showed a “non-significant increase,” primarily located in the northeastern and western parts of Guizhou, such as Tongren, Liupanshui, and Qiannan Prefecture. In contrast, areas with a decreasing trend accounted for 37.34%, with “non-significant decrease” areas comprising 36.75%, mostly concentrated in the central, northwestern, and southeastern regions, including Guiyang, Anshun, and the eastern part of Bijie. Areas with no significant change were relatively scattered, covering approximately 4.59% of the total study area.

Spatial trends of KRSEI in Guizhou Province (2002–2022). The figure was created using ArcGIS 10.6 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/home).

Further analysis reveals that areas showing significant or highly significant improvements in ecological quality are mainly concentrated in Qiannan. Eastern Tongren, western Liupanshui, and western Bijie, indicating effective ecological restoration in these regions. In contrast, areas experiencing significant or severe ecological degradation—such as western Zunyi, suburban areas of Guiyang, Huangping County, and regions surrounding Anshun—highlight issues related to intensive resource exploitation and delayed ecological restoration. Overall, the ecological quality in Guizhou has predominantly improved, with localized areas of degradation. This pattern not only reflects the positive outcomes of ecological civilization initiatives but also underscores the need to strengthen environmental regulation and restoration efforts in resource-intensive areas, to consolidate ecological gains and achieve sustainable development.

Analysis of driving factors and interactive mechanisms of ecological quality changes

Analysis of single-factor detection results

Using the Optimal Parameter Geographic Detector (OPGD) method, the explanatory power of seven natural and human factors on the spatiotemporal changes of KRSEI in Guizhou Province was systematically evaluated. The evaluation results, shown in Table 4, indicate that all detection factors passed the significance test (p < 0.001), highlighting their significant impact on the regional ecological quality. In terms of the q-value, vegetation coverage (FVC) exhibited the strongest explanatory power across all years (q-value range: 0.196–0.489), consistently being the dominant factor influencing ecological quality. Precipitation and land use type also showed notable performance in multiple years, indicating that natural water-thermal conditions and land resource allocation play a key role in shaping the ecological pattern. In contrast, the q-values of factors such as elevation, slope, and temperature were generally lower, suggesting that their role in the spatial differentiation of ecological quality in Guizhou Province is relatively minor, possibly due to their small spatial variability or indirect effects on the ecosystem. The 2022 data show that FVC (q = 0.489), population density (q = 0.182), and land use (q = 0.165) are the three key drivers of the spatial differentiation of ecological quality. This result reveals that the influence of human activities on ecosystem evolution is gradually increasing, especially in areas with population concentration and urban expansion. Among all detection factors, the explanatory power for the improved remote sensing ecological index is ranked as follows: vegetation coverage > population density > land use > slope > precipitation > elevation > temperature.

Analysis of factor interaction mechanisms

Further interaction analysis (Table 5) reveals that the combined influence of any two factors is consistently greater than their individual effects, demonstrating a pattern of “synergistic enhancement.” Most interactions exhibit “bivariate enhancement,” while some display “nonlinear enhancement.” No interactions were found to be independent or weakening in nature. For instance, slope and elevation (q = 0.131), elevation and population density (q = 0.254), and temperature and land use (q = 0.207) exhibit nonlinear enhancement, suggesting that the interplay between topography, human activities, and climate variables can drive more pronounced changes in ecological quality. Notably, combinations such as vegetation cover with precipitation (q = 0.513), population density (q = 0.513), and elevation (q = 0.511) show strong bivariate enhancement, highlighting the intricate coupled feedbacks between natural conditions and human influences. These factors typically influence ecological quality not in isolation but through coordinated interactions. For example, vegetation can regulate rainfall utilization by enhancing transpiration, while rainfall promotes vegetation growth, creating a positive feedback loop. In densely populated areas, rational spatial planning can enhance the efficiency of rainwater utilization and reduce ecological stress. Meanwhile, the combined effects of slope and precipitation may aggravate the risk of rocky desertification, although robust vegetation coverage can effectively buffer this impact. These ecological mechanisms indicate that environmental changes are the result of coupled natural and anthropogenic influences and thus require integrated, multi-factor management. The evolution of ecological quality in Guizhou is not driven by any single factor but emerges from the long-term interaction between natural systems (e.g., vegetation, hydrothermal conditions) and socio-economic activities (e.g., population pressure, land use changes). This multi-factor coupling mechanism underscores the importance of adopting a systems-based perspective in regional ecological policymaking, integrating both natural ecological foundations and anthropogenic drivers.

Discussion

Rationality analysis of the KRSEI model construction

To ensure the scientific rigor and applicability of the Karst Remote Sensing Ecological Index (KRSEI), this study conducted a comprehensive evaluation emphasizing its theoretical foundation, indicator selection, and statistical robustness. The Remote Sensing Ecological Index (RSEI) is an integrated model that combines multiple ecological indicators and has been widely used for ecological monitoring in urban and plain areas. However, as a general-purpose index, RSEI does not account for the distinctive geomorphological and ecological characteristics of karst regions, such as steep elevation gradients and severe rocky desertification. These limitations reduce its applicability in mountainous karst environments where terrain effects and rock exposure strongly influence ecological processes.

To address these challenges and improve adaptability and accuracy under complex karst conditions, we developed an enhanced index—KRSEI—by incorporating four key indicators: the Normalized Difference Modified Vegetation Index (NDMVI), wetness index (WET), rocky desertification index (SIRF), and land surface temperature (LST) into the conventional RSEI framework. Among these components, NDMVI is specifically designed to suppress topographic shadow effects and increase sensitivity to vegetation dynamics in mountainous areas, providing more accurate vegetation information than the traditional NDVI. The SIRF indicator integrates multiple factors—including the bare soil index, built-up index, bedrock exposure, and vegetation coverage—to comprehensively characterize rocky desertification and demonstrates high sensitivity to ecological degradation in karst environments. Together with WET and LST, these indicators capture vegetation greenness, surface moisture, land degradation, and thermal conditions, all of which are essential drivers of ecological quality in karst landscapes. To validate the representativeness and internal consistency of the KRSEI model, we randomly selected 3,000 valid sample points within the study area and applied a multiple linear regression analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics 26. The regression was designed to quantify the relationship between KRSEI and its four core components (NDMVI, WET, SIRF, and LST) across each year from 2002 to 2022. The statistical results are presented in Table 6.

For all years in the 2002–2022 period, the regression models passed the 1% significance level test, and the coefficient of determination (R²) consistently equaled 1. This result indicates that KRSEI achieves a perfect linear combination of its selected indicators, which is expected because the index was constructed using these components through a principal component–based approach. Nonetheless, the result demonstrates strong internal coherence and robustness of the model. The estimated coefficients reveal important ecological relationships. The coefficients for NDMVI and WET were consistently positive, confirming that increased vegetation greenness and surface moisture contribute positively to ecological quality—consistent with their ecological roles in maintaining ecosystem stability. Conversely, the coefficients for SIRF and LST were negative, indicating that intensified rocky desertification and higher surface temperatures adversely affect ecological conditions. Among these variables, SIRF exhibited the largest absolute coefficient values throughout the study period, underscoring its dominant influence on ecological degradation in karst regions. This finding aligns with the unique vulnerability of karst ecosystems to soil loss and bedrock exposure. Overall, these results confirm that KRSEI integrates key ecological factors in a scientifically rational manner and provides a comprehensive and sensitive indicator for characterizing ecological conditions under complex karst geomorphology. Its strong explanatory power and statistically validated structure highlight its reliability for long-term ecological monitoring and dynamic assessment in karst environments.4.2. Validation and Comparative Performance of KRSEI Against RSEI.

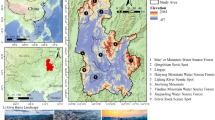

To comprehensively validate the applicability and superiority of the KRSEI model, a representative ecologically fragile region in Guizhou Province was selected for multi-year comparative analysis with the traditional RSEI. Contrast and entropy metrics were computed for both indices across multiple years from 2002 to 2022. As shown in Table 7, KRSEI consistently outperformed RSEI in all years, with both contrast and entropy values significantly higher. Notably, KRSEI achieved an average entropy improvement of 12.3%, indicating its superior ability to characterize ecological spatial heterogeneity and capture detailed environmental information. To further substantiate this conclusion, typical-area imagery was compared (Figs. 6 and 7), clearly demonstrating that KRSEI produces images with more pronounced texture details and stronger discriminative capability than RSEI, thereby confirming its enhanced sensitivity and expressive power.

In addition, to assess the rationality of the KRSEI component indicators, linear regression analysis was conducted between KRSEI and its four core ecological indicators. The results reveal that NDMVI and WET exhibit positive coefficients, suggesting that improvements in vegetation and moisture conditions have a positive effect on ecological quality—consistent with their essential roles in ecosystem stability. Conversely, SIRF and LST show negative correlations, indicating that intensified rocky desertification and elevated land surface temperature negatively affect ecological conditions. These findings collectively confirm the scientific validity of the KRSEI construction and demonstrate its strong applicability for accurately capturing ecological quality under complex karst geomorphological conditions, making it a robust tool for long-term ecological assessment and dynamic monitoring in karst regions.

KRSEI imagery of a severely ecologically fragile area. The figure was created using ArcGIS 10.6 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/home).

Regional applicability assessment

The KRSEI model developed in this study is designed to reflect the unique ecological characteristics of karst regions, with Guizhou Province serving as a representative case. By integrating vegetation greenness, surface moisture, rocky desertification intensity, and thermal conditions, KRSEI demonstrates strong capability in representing ecological heterogeneity under complex topography. Analysis of long-term results reveals clear spatial differentiation: areas with gentle slopes, deeper soils, and dense vegetation generally exhibit higher KRSEI values, indicating favorable hydrothermal conditions and stable ecosystems, whereas regions with steep slopes, shallow soils, and high bedrock exposure maintain persistently low values, reflecting degradation driven by severe soil erosion and limited water retention. These findings confirm that KRSEI effectively captures ecological stressors associated with terrain and lithology.

The successful application of KRSEI highlights its robustness and adaptability to heterogeneous karst environments. Unlike generalized indices that often underestimate ecological stress in high-relief regions, KRSEI explicitly accounts for rocky desertification while preserving sensitivity to vegetation and moisture variations. This advantage allows the model to provide a more accurate representation of ecological quality across diverse geomorphological settings. Although the current validation focuses on Guizhou, the indicator framework suggests strong potential for extension to other subtropical karst regions, such as Guangxi and Yunnan, and to other fragile mountainous ecosystems sharing similar environmental constraints. Future work should prioritize cross-regional comparative assessments and localized parameter calibration to enhance model transferability, while exploring integration with higher-resolution remote sensing data to improve adaptability and operational utility in large-scale ecological monitoring and sustainable land management.

Conclusions

In response to the fragile ecosystems and poor remote sensing adaptability in Southwest China’s karst regions, this study developed the Karst Remote Sensing Ecological Index (KRSEI), which integrates key ecological variables such as NDMVI, WET, SIRF, and LST. Using Guizhou Province as a case study, the model was applied to systematically assess the spatiotemporal dynamics and driving mechanisms of ecological quality from 2002 to 2022.

-

(1)

KRSEI more accurately captures the ecological characteristics of karst landscapes. Compared with the traditional RSEI, it improves contrast and information entropy in representing ecological heterogeneity by 12.3% and 9.6%, respectively. Regression analysis indicates that NDMVI and WET contribute positively to ecological quality, whereas SIRF and LST exert significant negative impacts. The model exhibits stable and reliable performance, enabling a more comprehensive and accurate reflection of the ecological conditions in karst environments.

-

(2)

Ecological quality in Guizhou Province exhibited a “decline–recovery–stabilization” trajectory, with pronounced spatial heterogeneity. From 2002 to 2022, regional ecological quality experienced fluctuations characterized by periods of increase, decline, and subsequent recovery. The average KRSEI value remained around 0.6, suggesting a moderate level of ecological quality. Following the advancement of ecological civilization initiatives after 2010, ecological conditions improved significantly. However, after 2020, some areas faced degradation risks due to excessive resource exploitation. Spatially, ecological conditions were better in the southeastern regions (with concentrated forest and cropland areas), while central areas and rocky desertification zones (e.g., Guiyang, Bijie) exhibited lower ecological quality, forming a pattern of better conditions in the southeast, poorer in the northwest.

-

(3)

Ecological change was driven by multiple factors with significant interaction effects. Vegetation coverage was the dominant driver, followed by precipitation, land use, and population density. Most factor interactions showed either bivariate enhancement or nonlinear synergistic effects. In particular, the combinations of FVC with precipitation and FVC with population density had the strongest explanatory power for spatial ecological variation, reflecting the high sensitivity of karst ecosystems to coupled natural–anthropogenic changes.

Although the KRSEI model performed well in Guizhou’s karst areas, its application to other karst or mountainous regions will require region-specific adjustments to the indicator system and parameter settings to enhance its generalizability and adaptability. This study provides a scientific tool for monitoring and dynamically assessing ecological quality in typical karst regions. The findings offer valuable data support and methodological insights for rocky desertification control and ecological restoration in Southwest China, serving as a reference for promoting sustainable regional ecosystem management.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the funding responsibility but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Van Beynen, P. & Townsend, K. A disturbance index for karst environments. Environ. Manage. 36, 101–116 (2005).

Calò, F. & Parise, M. Evaluating the human disturbance to karst environments in Southern Italy. Acta Carsologica 35, (2006).

van Beynen, P. E. & van Beynen, K. M. Human disturbance of karst environments. in Karst Management (ed van Beynen, P. E.) 379–397 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1207-2_17. (2011).

Wu, Z., Zhu, D., Xiong, K. & Wang, X. Dynamics of landscape ecological quality based on benefit evaluation coupled with the Rocky desertification control in South China karst. Ecol. Ind. 138, 108870 (2022).

Canedoli, C. et al. Integrating landscape ecology and the assessment of ecosystem services in the study of karst areas. Landsc. Ecol. 37, 347–365 (2022).

Zhang, J. Y., Dai, M. H., Wang, L. C., Zeng, C. F. & Su, W. C. The challenge and future of Rocky desertification control in karst areas in Southwest China. Solid Earth. 7, 83–91 (2016).

Chang, J. et al. Comprehensive assessment of Rocky desertification treatment in Southwest China karst. Land. Degrad. Dev. 35, 3461–3476 (2024).

Li, Y., Bai, X., Wang, S. & Tian, Y. Integrating mitigation measures for karst Rocky desertification land in the Southwest mountains of China. Carbonates Evaporites. 34, 1095–1106 (2019).

Xu, H. Q. A remote sensing urban ecological index and its application. Acta Ecol. Sin. 33, 7853–7862 (2013).

Xu, H. et al. Prediction of ecological effects of potential population and impervious surface increases using a remote sensing based ecological index (RSEI). Ecol. Ind. 93, 730–740 (2018).

Xu, H., Wang, Y., Guan, H., Shi, T. & Hu, X. Detecting ecological changes with a remote sensing based ecological index (RSEI) produced time series and change vector analysis. Remote Sens. 11, 2345 (2019).

Lu, Y. & Li, M. Eco-Economic Environment Coupling Based on Urban RSEI Theory. Mobile Information Systems 1600126 (2021). (2021).

An, M. et al. Spatiotemporal change of Ecologic environment quality and human interaction factors in three Gorges Ecologic economic corridor, based on RSEI. Ecol. Ind. 141, 109090 (2022).

Xu, C., Li, B., Kong, F. & He, T. Spatial-temporal variation, driving mechanism and management zoning of ecological resilience based on RSEI in a coastal metropolitan area. Ecol. Ind. 158, 111447 (2024).

Tang, H. et al. Impact of land cover change on a typical mining region and its ecological environment quality evaluation using remote sensing based ecological index (RSEI). Sustainability 14, 12694 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Monitoring of ecological environment changes in open-pit mines on the loess plateau from 1990 to 2023 based on RSEI. Ecol. Ind. 170, 113064 (2025).

Zhang, P. et al. A novel mine-Specific Eco-Environment index (MSEEI) for mine ecological environment monitoring using Landsat imagery. Remote Sens. 15, 933 (2023).

Zhu, D., Chen, T., Wang, Z. & Niu, R. Detecting ecological spatial-temporal changes by remote sensing ecological index with local adaptability. J. Environ. Manage. 299, 113655 (2021).

Yang, X., Meng, F., Fu, P., Wang, Y. & Liu, Y. Time-frequency optimization of RSEI: A case study of Yangtze river basin. Ecol. Ind. 141, 109080 (2022).

Jiang, F., Zhang, Y., Li, J. & Sun, Z. Research on remote sensing ecological environmental assessment method optimized by regional scale. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28, 68174–68187 (2021).

Ying, L. I. U. et al. Comparison between modified remote sensing ecological index and RSEI. zggx 26, 683–697 (2022).

Zheng, Z., Wu, Z., Chen, Y., Guo, C. & Marinello, F. Instability of remote sensing based ecological index (RSEI) and its improvement for time series analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 814, 152595 (2022).

Gong, C., Lyu, F. & Wang, Y. Spatiotemporal change and drivers of ecosystem quality in the loess plateau based on RSEI: A case study of Shanxi, China. Ecol. Ind. 155, 111060 (2023).

Lai, J., Li, J. & Liu, L. Optimization strategies for ecological security pattern based on the remote sensing ecological index in Yunnan Province, China. Land. Degrad. Dev. 36, 1326–1342 (2025).

Spatiotemporal change detection of ecological quality. And the associated affecting factors in Dongting lake Basin, based on RSEI. J. Clean. Prod. 302, 126995 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Estimation of remote sensing based ecological index along the grand Canal based on PCA-AHP-TOPSIS methodology. Ecol. Ind. 122, 107214 (2021).

Sun, C. et al. Ecological quality assessment and monitoring using a time-series remote sensing-based ecological index (ts-RSEI). GIScience Remote Sens. 59, 1793–1816 (2022).

Geng, J. et al. Analysis of Spatiotemporal variation and drivers of ecological quality in Fuzhou based on RSEI. Remote Sens. 14, 4900 (2022).

Chen, N., Cheng, G., Yang, J., Ding, H. & He, S. Evaluation of urban ecological environment quality based on improved RSEI and driving factors analysis. Sustainability 15, 8464 (2023).

Huang, S., Li,Yujie, H. & Wang, J. Haowen, Xue, Pengchengand Assessment of optimal seasonal selection for RSEI construction: a case study of ecological environment quality assessment in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region from 2001 to 2020. Geocarto International 39, 2311224 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Ecological network construction for bird communities in high-density urban areas: A perspective of integrated approaches. Ecol. Ind. 158, 111592 (2024).

Giofandi, E. A. et al. Assessment of remote sensing approach for urban ecological quality evaluation in Pekanbaru City, Riau Province indonesia. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 17, 28–35 (2024).

Williams, B. et al. Enhancing automated analysis of marine soundscapes using ecoacoustic indices and machine learning. Ecol. Ind. 140, 108986 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Combing remote sensing information entropy and machine learning for ecological environment assessment of Hefei-Nanjing-Hangzhou region, China. J. Environ. Manage. 325, 116533 (2023).

Chang, G. J. Biodiversity Estimation by environment drivers using machine/deep learning for ecological management. Ecol. Inf. 78, 102319 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Spatial patterns of hydroecological health in the semi-arid yellow river basin: revelations from machine learning models. Ecol. Ind. 168, 112799 (2024).

Najafzadeh, M., Ahmadi-Rad, E. S. & Gebler, D. Ecological States of watercourses regarding water quality parameters and hydromorphological parameters: deriving empirical equations by machine learning models. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 38, 665–688 (2024).

Mandal, B. Leveraging machine learning for analyzing the nexus between land use and land cover change, land surface temperature and biophysical indices in an eco-sensitive region of Brahmani-Dwarka interfluve. Results Eng. 24, 102854 (2024).

Ryo, M. Ecology with artificial intelligence and machine learning in asia: A historical perspective and emerging trends. Ecol. Res. 39, 5–14 (2024).

Gong, X., Li, T., Wang, R., Hu, S. & Yuan, S. Beyond the remote sensing ecological index: A comprehensive ecological quality evaluation using a Deep-Learning-Based remote sensing ecological index. Remote Sens. 17, 558 (2025).

Shamuxi, A. et al. Spatial pattern and driving mechanisms of dryland landscape ecological risk: insights from an integrated geographic detector and machine learning model. Ecol. Ind. 172, 113305 (2025).

Hamel, S., Garel, M., Festa-Bianchet, M., Gaillard, J. M. & Côté, S. D. Spring normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) predicts annual variation in timing of peak faecal crude protein in mountain ungulates. J. Appl. Ecol. 46, 582–589 (2009).

Higginbottom, T. P. et al. High-resolution wetness index mapping: A useful tool for regional scale wetland management. Ecol. Inf. 48, 89–96 (2018).

Yue, Y. et al. Spectral indices for estimating ecological indicators of karst Rocky desertification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 31, 2115–2122 (2010).

Ma, T., Deng, X., Chen, L. & Xiang, W. The soil properties and their effects on plant diversity in different degrees of Rocky desertification. Sci. Total Environ. 736, 139667 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Spectral analysis of seasonal rock and vegetation changes for detecting karst Rocky desertification in Southwest China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 100, 102337 (2021).

Maćkiewicz, A. & Ratajczak, W. Principal components analysis (PCA). Comput. Geosci. 19, 303–342 (1993).

Akritas, M. G., Murphy, S. A. & Lavalley, M. P. The Theil-Sen estimator with doubly censored data and applications to astronomy. Journal Am. Stat. Association (1995).

Hamed, K. H. & Ramachandra Rao, A. A modified Mann-Kendall trend test for autocorrelated data. J. Hydrol. 204, 182–196 (1998).

Song, Y., Wang, J., Ge, Y. & Xu, C. An optimal parameters-based geographical detector model enhances geographic characteristics of explanatory variables for Spatial heterogeneity analysis: cases with different types of Spatial data. GIScience & Remote Sensing (2020).

Funding

The research was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41701449), Nanhu Scholars Program for Young Scholars of XYNU. Postgraduate Education Reform and Quality Improvement Project of Henan Province (HNYJS2020JD14).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author ContributionsConceptualization, X.Y. and H.T.; methodology, X.Y. and Y.W.; software, T.W.; validation, Y.X.; formal analysis, H.T.; investigation, T.W.; resources, J.L; data curation, T.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Y.; writing—review and editing, X.Y. and H.T.; visualization, Y.X.; supervision, Y.W.; project administration, X.Y.; funding acquisition, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, X., Tian, H., Wang, Y. et al. Karst remote sensing ecological index KRSEI for monitoring ecological quality in Southwest China. Sci Rep 15, 36382 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20425-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20425-8