Abstract

Robot manipulators exhibit highly nonlinear dynamics influenced by uncertainties such as external disturbances and varying loads. Ensuring robust control and accurate simulation of their dynamical response is crucial for industrial applications. This article presents a novel two-stage robust optimal control approach for robotic manipulators operating under load mass uncertainties and external disturbances. In the first stage, a Linear Quadratic Regulator is applied with optimized weights to handle varying payloads of the nonlinear system in the absence of disturbances. In the second stage, a hybrid approach combining robust optimal control and Integral Sliding Mode Control is utilized to handle both payload uncertainties and external disturbances, ensuring robust stability across a wide range of operating conditions. The effectiveness of this approach is demonstrated using a two-joint SCARA robot, analyzing key variables like angular displacement, velocities, and joint torques across different payloads and bounded disturbances. The simulation results confirm the system’s stable convergence, with phase portraits of sliding surfaces providing geometric insights into the stability of the nonlinear system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rigid robotic manipulators are widely utilized in various industries for different applications such as painting, welding, assembly, and material handling1,2. Engineers appreciate the versatility of robotic manipulators, but these machines also have complex nonlinear characteristics, significant coupling effects, imprecise physical models, and variable parameters3. These intricate features can greatly affect the accuracy, efficiency, and safety of robotic manipulators. Moreover, developing an effective control technique to achieve high tracking performance in robotic manipulators with these complex characteristics is a challenging task. The presence of uncertainty further complicates the task, especially as the number of linkages increases.

The three main approaches in control theory are generally categorized as computed torque control, robust control and adaptive control4. Computed torque control is utilized for specific applications5. It is a type of feedback linearization in which an inner-loop controller is used to cancel out the robot’s nonlinear dynamics, leaving behind residual linear dynamics that can be controlled using a range of linear control techniques. It is frequently referred to as inverse dynamics control since it depends on the inversion of robot dynamics. Robust control strategies include famous techniques like sliding mode control (SMC) and optimal control which are effectively used for robot manipulators to address the challenges of uncertainty and disturbance rejection. Lee, et al.6 investigated tracking performance and lower energy consumption of robot manipulators by employing adaptive integral sliding mode control (AISMC) and time-delay estimation. Xiao et al.7 worked on two sliding-mode observers to estimate uncertain kinematics torques and proposing a control law to ensure that the desired trajectory converges in a finite time. Norsahperi and Danapalasingam8 investigated robust control in the presence of external disturbances and internal dynamics variations using an improved optimal integral sliding mode control (OISMC) scheme. Adaptive controls are feed-forward controllers that make dynamic adjustments to system parameters in real-time to manage uncertainty and disturbances for optimal performance and stability across different operating conditions9. Enhancing performance often leads to an increase in the order of the total control system. The adaptive control scheme offers an alternative to the robust control scheme, and can also be combined with the computed torque technique. Kino et al.10 suggested a robust PD control approach for parallel-wire driven robots that includes adaptive compensation for the internal force error caused by unpredictable actuator positions. Ming-Chih and An-Chyau11 applied Backstepping with model reference adaptive control to manage time-varying uncertainty and control robots with flexible joints, achieving successful results. To capture manipulator dynamics, Wai and Yang12 developed a continuous-time dynamic fuzzy model with online learning capability. Thus, above the studies emphasize the importance of robust control methodologies such as optimal control and sliding mode for addressing uncertainties and disturbances in robot manipulators. Other controls such as adaptive control, computed torque, and feedback linearization are also active in enhancing tracking performance, stability, and energy efficiency in dynamic environments.

Combining two control schemes, can significantly optimize trajectory tracking and disturbance rejection in robotics systems, making it a powerful solution for complex control challenges. Van et al.13 introduced a novel global finite-time cooperative control by combining finite-time disturbance observer (FTDO) and finite-time integral sliding mode controller (FTISMC) to enhance robustness against model uncertainties and disturbances. The proposed technique ensured effective performance in handling the uncertainties and disturbances. Xian et al.14 developed a two-scheme method GPIO-CSMC to address trajectory tracking for disturbed robots. Tests on a 2-DOF robot comparing PID, SMC and CSMC show the proposed method offers faster tracking and higher anti-disturbance performance. Nguyen15 modeled the FSMPIF algorithm by combining PI, SMC, and Fuzzy algorithms to reduce automobile vibrations. Results showed significant improvements in ride comfort, with displacement and acceleration values decreasing by up to 2.55% and 12.59% compared to passive systems. Rani and Kuma16 introduced an intelligent optimal control scheme for hybrid position and force for reconfigurable manipulators under uncertainties. The controller combines HJB optimization, RBF neural networks, and adaptive bounds. The results demonstrated the method’s effectiveness compared to existing approaches. Admas et al.17 used combine NPID and HOSMC controls for vehicle suspension systems, focusing on non-linear and coupled dynamics. The results demonstrated improved performance and robustness under disturbances. Song et al.18 developed a control for multiple robot manipulators by combining SMC and reinforcement learning (RL). Its effectiveness is validated through Lyapunov stability analysis and found to be an effective control for multiple robot manipulator systems. Yin et al.19 developed an adaptive non-singular terminal sliding mode control (NTSM) with nonlinear disturbance observer (NDO) for trajectory tracking in multi-joint robotic arms. Results showed that the proposed method reduces steady-state errors by 36.58%–44.68% compared to other methods, demonstrating higher accuracy and stability. Pan and Xin20 employed the theta-D optimal control approach for position control to obtain an approximate feedback robust solution by combining the use of perturbation techniques for unknown payloads at the end effector of the robot manipulator. This method holds for specific type of manipulators which follow specific assumptions.

Furtado et al.21 defined impedance control of a robot manipulator using the State-Dependent Riccati Equation (SDRE) approach and compared it with Quadratic Programming (QP). Their results indicate that the SDRE technique outperformed QP. Impedance control is formulated as an optimal control problem aimed at minimizing the distance between the actual and desired states. However, the SDRE method has certain limitations not present in general optimal control formulations, which can affect tracking accuracy and potentially render the problem ill-posed. Elmogy et al.22 introduced an integrated control scheme that combines adaptive PID and continuous second-order sliding mode control (CSOS) with generalized artificial neural networks (GANN) for robot manipulators. The adaptive CSOS-GANN model enhances robustness, handles uncertainties, and eliminates discontinuities in traditional methods. Ali et al.23 worked on the control of robotic manipulators with the aid of geometrical stability using phase portrait of the sliding surfaces which are an alternative way to prove the stability of the system. Thus, combining control schemes addresses multiple challenges simultaneously, such as uncertainties, disturbances, and nonlinearities, making them more effective because classic control may excel in one area like stability or efficiency. Furthermore, the work on position control obtained by Lin24 and the same problem handled by Pan and Xin20 proved the stability and a convergence of a specific class of manipulators that satisfy the strict assumptions, mainly that all nonlinear terms must vanish at the origin for the flexibility of such assumption to have position control of the manipulator.

This article presents a novel two-stage robust optimal control approach for robotic manipulators that addresses uncertainties in payload mass and external disturbances. The scheme is motivated by a combine of schemes applicable to manipulators, where nonlinear terms are categorized into those that vanish at the origin and those that do not. In the first stage, an optimal control framework is employed to address uncertainties in the payload mass at the end effector. In the second stage, a hybrid approach that combines robust optimal control and integral sliding mode control (ISMC) is utilized to address both payload uncertainties and external disturbances. This dual-stage strategy ensures robust stability across a wide range of payload variations and disturbances, enhancing system flexibility. To further validate stability, phase portraits of sliding surfaces are introduced, offering a geometric representation of system stability. This is very important when traditional Lyapunov-based stability analysis is difficult to apply. The proposed method not only improves control accuracy but also provides a more adaptable and reliable solution for robotic manipulators in dynamic and uncertain environments.

The article is organized into several sections to provide a comprehensive understanding of the proposed methodology. Section 2, introduces the robot manipulator model, while Sect. 3 details the two-stage algorithm central to the robust control approach. Section 4 provides the control design of the classical sliding mode control. Section 5 presents numerical results and conducts discussions to validate the efficacy of the method. Finally, Sect. 6 draws conclusions based on the study’s findings.

Robot manipulator dynamical model

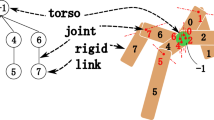

Consider the SCARA-type robot manipulator with two joints25. The dynamics of the robot manipulator is modeled as a series of n rigid beams connected in series, with one point fixed as a base and the other end regarded as the end effector used to handle payloads. The beams are connected with either a revolute joint or a prismatic joint while torques are provided at the joints. Here the Considered robot is a two revolute joint robot manipulator, where the schematic diagram of the manipulator is shown in Fig. 1.

The dynamical equation of the robotic manipulator obtained via Euler-Lagrange equation of motion20 which is prescribed as.

where, \(\theta\) is generalized coordinate in vector form, \(M(\theta ;\;{m_L})\) is the inertia matrix, \(V(\theta ,\;\dot {\theta };\;{m_L})\) is Coriolis force vector, \(F(\dot {\theta })\) is frictional force at the joints, \(G(\theta ;\;{m_L})\) is gravitational force component, \(\tau\) is a non-conservative generalized force vector and \({\tau _{ext}}\) is disturbance in the input torques/non-conservative generalized force.

here, the components in above matrices are expressed as

Now define the state variables in compact notation as

Further collecting the Coriolis, friction and gravity force vectors are written as

Therefor the mathematical model by using Eq. (1) and Eq. (5), we have as

here Eq. (6) presents the compact form of the nonlinear mathematical equation of the robot manipulator.

Two-stage algorithm

In this section, a two-stage algorithm for the robust control of the robot manipulator is presented. The mathematical control design is divided into two following robust control techniques, which are applied to the nonlinear control system.

Optimal control approach

Firstly, at this stage we consider the model Eq. (6) without taking into account external disturbances as, and working for the background to apply robust optimal control.

In the current study, there are uncertainties in M(q) and \(N(q,\dot{q})\) due to the unknown load at end effector with the added external disturbances in the considered system. The following bounds on the uncertainties are assumed as

-

There exist the matrices M0 (q) and M1 (q) which are positive definite symmetric such that:

-

There exists the matrix \(N(q,\dot{q})\) and a nonnegative function \(n(q,\dot{q})\) such that

By denoting the coordinates for state space presentation as

Therefore, the input in the state space coordinates is presented as

Hence, the state space equation of the model Eq. (7) can be expressed using in Eq. (10) and Eq. (11) as

where

The state space model in Eq. (12) has uncertainty in the load mass at the end effector of the robot manipulator. In order to solve the dynamic response of the robot manipulator in Eq. (13), the following bounds are obtained for the optimal control approach to roust control24 as

Since matching conditions are satisfied in this problem, we follow the approach presented by24 to consider the nonlinear case, stated as

Additionally, the uncertainty of the nonlinear term \(f(x)\,\)is within the matrix’s range of matrix B. It is more precisely describes as a nonlinear vector function \(f(x;\;{m_L})\,\) spanned by matrix B. The problem described in Eq. (15) satisfies the matching conditions, further \(Ax=0\;\)and \(f(x;\;{m_L})=0\). At \(x=0\) the equilibrium state, for which stability is the desired outcome, employing the following robust control approach.

In this consequence, a feedback control law \(u={u_0}(t)\) is considered to define the following closed loop system

The system Eq. (16) is globally asymptotically stable for all uncertainties in \(f(x;\;{m_L})\) which are in the range of \({f_{\hbox{max} }}(x)\) defined as

Now to calculate the robust control problem Eq. (16), it is first converted into the following optimal control problem where we consider the auxiliary system as

with u = u0 (t) which minimize the following cost functional

At the first stage, Eq. (18) is solved, and this solution is used to address Eq. (16), as per the result presented by20,24.

Theorem 1

If the solution of the optimal control problem Eq. (18) exists, then it is a solution to the robust control Eq. (16) with the bound in (17).

Proof

We can see that the Cost functional is non-negative for every state \(x\epsilon{R}^n\), we choose Cost functional value as a Lyapunov function.

That is

According to the Hamilton Jacobi Bellman Equation, we have

Since

We have,

and

Hence, according to Lyapunov stability we assure that the given feedback control is stable24. At the second stage, we deal with the external disturbances and reconsider Eq. (6) for which purpose an integral sliding mode control (ISMC) is adopted as follows.

Integral sliding-mode control

In accordance with the LQR technique for the optimal control approach, using the control input \({u_0}(t)\), it has been demonstrated that the closed-loop dynamical system described in Eq. (15) exhibits asymptotic stability24, and the cost functional defined in Eq (19) is attained. Nevertheless, when the model Eq. (6) includes external disturbances and the control input \(u={u_0}(t)\) is employed, the system may deviate from the desired target value or even become unstable. In this context, a discontinuous switching control signal is developed, inspired by the Integral Sliding Mode Control (ISMC) approach. This control strategy guarantees that the robot’s end effector will reach its desired position, even in the presence of external disturbances26, when the input u is applied.

To design ISMC the following sliding surfaces are assumed

where \(\dot {\phi }(t)= - H(Ax+B{u_0}+Bf(x;\;{m_L}))\) and H is a constant matrix, defined as a pseudo inverse of matrix B with condition that the matrix HB is nonsingular. Now by considering the state space dynamics as in Eq. (6), we write

where \(\gamma (x)=M_{0}^{{ - 1}}(x){\tau _{ext}}\).

It is evident from Eq. (6) that external disturbances are incorporated within the matching conditions. Consequently, the control input is redefined as follows

here, u0 represents the control component derived from the initial stage without external disturbances, while corresponds to the ISMC component. Taking the derivative of Eq. (26) leads to the following

By using Eqs. (27, 28 and 29), we arrive at

For the stability criteria, choosing a Lyapunov function of the form

By assuming the switching control input

we have through Eqs. (32) and (33)

Since \(HB={I_m}\), therefor \(\rho>Sup\left\| {\gamma (x)} \right\|,\) which agrees with the convergence of the results.

Sliding mode controller

For the trajectory tracking via the classical sliding mode control is applied by defining the sliding variable vector as:

The time derivative of the sliding surface vector is defined as

For stability purpose applying the constant rate reaching law as:

Using Eq. (6) we have

Where the relation between q and \(\theta\) is defined in Eq. (4). Thus, by using Eq. (4) and Eq. (38)

Through Eqs. (36, 37 and 39) we have:

Here choosing feedback controller as:

Therefore, using Eqs. (39, and 40) we have:

Where the forces can be calculated through the Eq. (41) as:

Numerical simulation

In this section, we present the results obtained by implementation of the proposed two-stage algorithm. These results are acquired while considering the physical parameters20,24, as delineated in Table 1 below.

All numerical simulations in this study are executed using Mathematica. The key variables of interest encompass joint angles, joint angular velocities, and the computed torques. These variables are meticulously computed and presented across a spectrum of mass values applied at the end effector, specifically, loads of 5 oz, 10 oz, 15 oz, and 20 oz. The units of measurement employed are radians for joint angles rad/sec for joint angular velocities, and newton-meters for the torques of each joint. When solving the system’s dynamical response as described in Eq. (9), the following control input is employed:

Thereby implying

Thus yields

The state space representation in Eq. (46) can be expressed in the form

By denoting \({M^{ - 1}}{M_0}=I+h({x_1};\;{m_L})\), and \(f(x;\;{m_L})={M^{ - 1}}({x_1};\;{m_L})({N_0}(x) - N(x;\;{m_L}))\) in Eq.(46), we rewrite

The weight matrix Q is calculated by using the condition\(\left\| {f(x;\;{m_L})} \right\| \leqslant {f_{\hbox{max} }}(x)\).

It follows that

In the simulations, we choose the joints angular velocities bounds with maximum magnitude of 10 rad/s so that \(\mid\dot{q}_1\mid\leqslant{10}\) and \(\mid\dot{q}_2\mid\leqslant{10}\) whereas the maximum load at end effector of the considered robot is taken to be\({m_L}=20\,oz\). Further, the maximum and minimum values of the nonlinear terms in the robotics dynamics are calculated based on minimum and the maximum values of the payload mass.

Equation (49) recasts into

It becomes evident that, following a series of manipulations involving the inertia matrix and the constraints elaborated in Sect. 2, we have derived the following result \(\left\| {{M_1}^{{ - 1}}} \right\|=\frac{1}{{5671}}.\).

Now from the result in Theorem 1, we know that \({x^T}Qx<\left| {{f^T}(x;\;{m_L})f(x;\;{m_L})} \right|\), which implies

According to LQR theory, the control is given as \({u_0}= - {B^T}Px\), where P can be calculated through the following algebraic Riccati Eq.

To compute \({u_s}\), we shall reevaluate Eq. (6) employing the notation of generalized coordinates. Following a series of manipulations, we arrive at the following expression:

Here u= u0+ us, provided \({u_s}= - \rho Sign(s)\).

Furthermore, assume that the dynamical system is subjected to the following external disturbance9. Cogging torque caused by misalignment of the actuators due to uneven spacing eccentricity or manufacturing errors. This disturbance generally exists as a bounded disturbance.

Since, it follows from Eq. (34)

By choosing the matrix \(H=(B^TB)^{-1}B^T\) , such as, \(HB={I_2}\) the value of \(\rho=3.6\) is calculated. Thereby the final feedback control is calculated as

Whereas the torque is computed by

The simulations performed under four different mass loadings to demonstrate the robustness of the proposed two-stage algorithm.

Results and discussion

In this section, the performance of the proposed robust control is discussed using Robust Optimal Control without disturbances (ROCWD) and Robust Optimal Integral Sliding Mode Control with Disturbances (ROISMCWD). To measure the performance, the joint angles and joint velocities are calculated at different mass loads mL of 5 oz, 10 oz, 15 oz and 20 oz and the results are displayed in Figures 2(a)−5(b). In Figures 2(a) and 2(b), joint one converges to its desired position in approximately 1.5 s, while joint two achieves its desired position in about 2 s at a load mass of 5 oz. Subsequently, the joint velocities settle to the desired states around 2.5 s, irrespective of the presence or absence of disturbances. Despite their resemblance, simulations with disturbances exhibit slightly small oscillations in both joint positions and velocities around their equilibrium points. In Figures 3(a) and 3(b), the joints and their corresponding velocities converge to their desired positions within 2 to 3 s at a load mass of 10 oz. Similarly, in Figures 4(a) and (b), the joints and their velocities converge to their desired positions within 2.5 to 3.75 s at a load mass of 15 oz., and within 3.8 to 4.25 s at a load mass of 20 oz. In Figures 5(a) and 5(b), it is evident that as the load mass increases; the joint angles gradually reach their target values after an initial struggle. It is important to note that the optimal control, when not considering external disturbances, exhibits smooth convergence. However, when external disturbances are present, the joint angles and velocities struggle to converge to the desired values with slightly less effort as compared to the joint angles and joint velocities which do not carry the disturbances due to the efficiency of the robust optimal integral sliding mode control method. However, the challenge posed by the chattering phenomenon on the sliding surface is effectively addressed in the computed values of joint angles and velocities with a novel control technique that is ROISMCWD.

In Figs. 6, 7, 8 and 9, the left column represents the input control values obtained via ROCWD, while the right column represents the input control values obtained via ROISMCWD. It is noted that \({q_1}\) and \({q_2}\) are calculated from the actual angles \(\theta\) , which converge \([0\: 0]\) so that \([\theta_1\:\theta_2]\) converges to \(\left[ {\pi /2\quad 0} \right]\) radians. The control torques depicted in Figure 6 show chattering phenomena observed in the joint positions. Initially, the control efforts are relatively high to drive the manipulator to the desired position, but they decrease rapidly as the manipulator approaches the target position. In Figure 7, the control torque required to achieve the desired position stabilizes in about 2 s despite the presence of external disturbances at lower values of the load mass. However, as the load mass increases, a higher level of control input is needed, as evident in Figs. 8 and 9. This indicates that more effort is required to drive the joint trajectories in the presence of disturbances, persisting until the final stage to maintain stability.

Figures 10 and 11 present the phase portraits of the sliding surface for the ROISMCWD method, magnified \({10^{18}} \times {10^{16}}\) for a clearer view of the behavior and visualization of chattering effects. It is observed that the sliding variables are converging to zero, confirming the stability of the nonlinear system. Additionally, Figs. 12 and 13 show the behavior of sliding surface in addressing the chattering phenomenon at different payload masses. These figures illustrate the trajectories of the sliding variables \({s_1}\) and \({s_2}\) under payload masses of 10 oz and 15 oz, respectively. The results show a rapid convergence of the sliding variables to zero within the first second. The chattering amplitude remains minimal, with steady-state fluctuations on the order of \({10^{ - 18}}\), which is significantly lower than what is typically observed in classical SMC. This confirms the system’s stability and the controller’s capability to handle uncertainties and disturbances. The reduction in chattering is achieved through the integral action incorporated into the sliding mode control.

Figures 14 and 15 present a comparison between the newly proposed method and the classical Sliding Mode Controller (SMC). It is observed that the proposed method achieves faster convergence than the SMC for both joint positions and joint velocities. Furthermore, Figure 16 illustrates a compare the control torques calculated using ROCWD and the classical SMC, while Figure 17 illustrates a compare the control torques calculated using ROISMCWD and the classical SMC. The results show that the proposed methods are more energy-efficient than the SMC. It demonstrates superior long-term efficiency with reduced energy consumption. Notice that the values of the parameters used in SMC are chosen as \(\lambda ={[\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 6&{2.5} \end{array}]^T}\)and the constant rate of reaching as \(K=Diag\{ 20,\;15\}\), where all other parameters remain same as given in Table 1.

Figures 18 and 19 show the phase trajectories that are drawn toward the sliding surface, where they exhibit chattering once they reach the sliding manifold. The trajectories spiral, converging and oscillating around the sliding surface, reflecting the trade-off between robustness and chattering in the proposed ROISMCWD controller under varying payload conditions. Computed over a time span of 0 to 20 s, the results demonstrate rapid convergence toward the origin, confirming that the sliding condition is both achieved and maintained. The initial reaching phase is marked by a swift spiraling motion of the state trajectories toward the designed sliding manifolds. Furthermore, although an increase in mass broadens the spirals during the reaching phase, the final chattering amplitude around the sliding manifold remains unchanged.

Table 2 presents the root mean square error (RMSE) of each trajectory to evaluate the system’s performance at desired position. RMSE measures the average deviation between predicted and actual values, with smaller values representing that the trajectories closely follow the estimated path. The RMSE values for each payload mass, both with and without disturbances are small, validating the system’s convergence.

The performance of the proposed control is compared with other methods in Table 3. The performance is evaluated using two time-domain metrics: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Integral of Squared Control Input (ISU) across two key trajectories: \({q_1}(t)\), and \({q_2}(t)\) representing the major dynamic states of the system. As shown in the Table 3, the proposed controllers ROCWD and ROISMCWD consistently achieves superior values for all metrics across all signals, indicating better control performance in terms of accuracy, speed of convergence, and energy efficiency. Specifically, the RMSE values for the proposed method are significantly smaller compared to SMC, highlighting its sustainability over time. Additionally, ISU values are also the lowest for the proposed controllers, implying that they require less control effort and produce smoother actuation signals. This is advantageous for actuator lifespan and overall system efficiency.

In conclusion, these quantitative results confirm that the proposed control strategy yields better results in tracking performance and control efficiency, making it a robust and energy-effective solution for the system under consideration.

Conclusion

A novel robust control approach designed for manipulators operating in situations characterized by uncertain dynamics, such as unknown loads, gravitational effects, and external disturbances is being investigated. The robust control method combines optimal control techniques with the integral sliding mode control framework, effectively incorporating uncertainty bounds into the cost functional to achieve both robust stability and optimality. The results, observed under scenarios with and without disturbances, reveal several key findings:

-

Joint angles and velocities under various load masses exhibit consistent convergence trends, with longer stabilization times observed for higher loads.

-

Control inputs depict higher effort requirements in the presence of disturbances, indicating greater struggle to maintain stability.

-

The phase portrait is presented to facilitate stability via a geometrical aspect.

-

The RMSE is calculated to ensure the convergence of the joint angles to reach their desired position.

-

A comparison of the ROCWD and ROISMCWD with classical SMC are provided to validate the proposed methods.

Overall, the robust control scheme demonstrates effective performance across different load conditions and disturbances, highlighting its potential for robust trajectory convergence in mechanical manipulators.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- q :

-

Generalized coordinate vector

- \(\theta\) :

-

Joint angle vector

- \(M\left( {\theta ;\;{m_L}} \right)\) :

-

Inertia matrix

- \(V(\theta ,\;\dot {\theta };\;{m_L})\) :

-

Coriolis force vector

- \(F\left( {\dot {q}} \right)\) :

-

Frictional force at the joints

- \(G\left( {\theta ;\;{m_L}} \right)\) :

-

Gravitational force component

- \(\eta\) :

-

Nonlinear Function

- u :

-

Control input in state space coordinates

- \(A,B\) :

-

State space matrices

- K :

-

Feedback control gain matrix for optimal control part

- S :

-

Sliding variable vector\(S={[\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{s_1}}&{{s_2}} \end{array}]^T}\)

- \({s_1},\,{s_2}\) :

-

Sliding variables

- Q :

-

Weight matrix for the optimal control

- \(\rho\) :

-

Feedback control gain matrix

- \(\tau\) :

-

Non-conservative generalized force vector

- \({\tau _{ext}}\) :

-

Disturbance in the input torques

- x :

-

State variables in compact notation

- \(f\left( {x;\;{m_L}} \right)\) :

-

Uncertain nonlinear term

- H :

-

Defined as a left pseudo inverse of matrix B

- \({r_1},{r_2}\) :

-

Length of the center of mass of the links

- \({b_1},{b_2}\) :

-

Coefficient of friction for link 1 and link 2

- g :

-

Gravitational acceleration

- \({J_1},{J_2}\) :

-

Moment of inertia of link 1 and link 2

- \({l_1},{l_2}\) :

-

Length of link 1 and link 2

- \({m_1},{m_2}\) :

-

Mass of link 1 and link 2

- \({\dot {\theta }_1},{\dot {\theta }_2}\) :

-

Joint angular velocities

- \({\theta _1},{\theta _2}\) :

-

Joint angles

- \({m_L}\) :

-

Payload mas

References

Hägele, M., Nilsson, K. J., Pires, N. & Bischoff, R. Industrial robotics. In Springer Handbook of Robotics 2nd edn, 1385–1422 (2016).

Jin, L., Li, S., He, J. & Jiguo Yu, and Robot manipulator control using neural networks: A survey. Neurocomputing 285, 23–34 (2018).

Slotine, Jean-Jacques, E. The robust control of robot manipulators. Int. J. Robot. Res. 4 (2), 49–64 (1985).

Behal, A., Dixon, W., Dawson, D. M. & Xian, B. Lyapunov-based control of robotic systems. Vol. 36. CRC Press, (2009).

Lima, J. J. et al. Nonlinear control and parametric uncertainties of flexible-joint robots. Meccanica 59, 1–23 (2024).

Lee, J., Chang, P. H. & Jin, M. Adaptive integral sliding mode control with time-delay Estimation for robot manipulators. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 64 (8), 6796–6804 (2017).

Xiao, B., Yin, S. & Kaynak, O. Tracking control of robotic manipulators with uncertain kinematics and dynamics. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 63 (10), 6439–6449 (2016).

Norsahperi, N. M. H. & Danapalasingam, K. A. An improved optimal integral sliding mode control for uncertain robotic manipulators with reduced tracking error, chattering, and energy consumption. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 142, 106747 (2020).

Lewis, F. L., Darren, M., Dawson, Chaouki, T. & Abdallah Robot Manipulator Control: Theory and Practice (CRC, 2003).

Kino, H., Yahiro, T., Takemura, F. & Morizono, T. Robust PD control using adaptive compensation for completely restrained parallel-wire driven robots: translational systems using the minimum number of wires under zero-gravity condition. IEEE Trans. Robot. 23 (4), 803–812 (2007).

Chien, M. C. & An-Chyau, H. Adaptive control for flexible-joint electrically driven robot with time-varying uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 54 (2), 1032–1038 (2007).

Wai, R. J. & Zhi-Wei, Y. Adaptive fuzzy neural network control design via a T–S fuzzy model for a robot manipulator including actuator dynamics. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybernetics Part. B (Cybernetics). 38 (5), 1326–1346 (2008).

Van, M., Ge, S. S. & Ceglarek, D. Global finite-time cooperative control for multiple manipulators using integral sliding mode control. Asian. J. Control. 24 (6), 2862–2876 (2022).

Xian, J., Shen, L., Chen, J. & Feng, W. Continuous sliding mode control of robotic manipulators based on time-varying disturbance Estimation and compensation. IEEE Access. 10, 43473–43485 (2022).

Nguyen, T. A. A novel approach with a fuzzy sliding mode proportional integral control algorithm tuned by fuzzy method (FSMPIF). Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 7327 (2023).

Rani, K. & Kumar, N. Design of intelligent optimal controller for hybrid position/force control of constrained reconfigurable manipulators. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 14, 13421–13432 (2023).

Admas, Y. A., Mitiku, H. M., Salau, A. O., Omeje, C. O. & Braide, S. L. Control of a fixed wing unmanned aerial vehicle using a higher-order sliding mode controller and non-linear PID controller. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 23139 (2024).

Song, Y., Li, Z., Li, B. & Wen, G. Optimized leader-follower consensus control using combination of reinforcement learning and sliding mode mechanism for multiple robot manipulator system. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control. 34 (8), 5212–5228 (2024).

Yin, S., Shi, Z., Liu, Y., Xue, G. & You, H. Adaptive Non-Singular terminal sliding mode trajectory tracking control of robotic manipulators based on disturbance observer under unknown Time-Varying disturbance. Processes 13 (1), 266 (2025).

Pan, H. & Xin, M. Nonlinear robust and optimal control of robot manipulators. Nonlinear Dyn. 76, 237–254 (2014).

Furtado, G., Phillips, P. P., Americano & Forner-Cordero, A. Impedance control as an optimal control problem: a novel formulation of impedance controllers as a subcase of optimal control. J. Brazilian Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 42 (10), 513 (2020).

Elmogy, A., Alhemaly, N., El-Ghaish, H. & Elawady, W. An enhanced neuro-adaptive PID sliding mode control for robot manipulators: promoting sustainable automation. Neural Comput. Appl. 37, 1–22 (2025).

Ali, I. et al. Robust tracking control of a three-degree-of-freedom robot manipulator with disturbances using an integral sliding mode controller. Int. J. Intell. Rob. Appl. 8 (2), 370–379 (2024).

Lin, F. Robust Control Design: an Optimal Control Approach (Wiley, 2007).

Jazar, R. N. & Robot Dynamics. Theory of Applied Robotics: Kinematics, Dynamics, and Control. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 609–684. (2021).

Bai, R. & He-Bin, W. Robust optimal control for the vehicle suspension system with uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Cybernetics. 52 (9), 9263–9273 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through the Large Research Project under grant number RGP. 2/103/46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Irfan Ali: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft; Mohsan Hassan: Conceptualization, Methodology; Zarqa Bano: Supervision; Edrisa Jawo: Software, Writing—original draft, Mohammed M. A. Almazah: Review-Edition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, I., Hassan, M., Bano, Z. et al. Robust control of robot manipulator dynamics with two stages algorithm of optimal and integral sliding mode approaches. Sci Rep 15, 36585 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20478-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20478-9