Abstract

This study extends the classical circular restricted three-body problem (CR3BP) by introducing a dominant central primary, forming a collinear restricted four-body problem (CR4BP) that better reflects the dynamics of real planetary systems. The model remains dynamically consistent and non-degenerate when the central mass parameter μ0 lies in (½, 1) and the peripheral mass μ satisfies 0 < μ < ½ (1 – μ0). It generalizes to the CR3BP by setting μ0 = 0, recovering classical results. The system exhibits six libration points: four collinear and two symmetric non-collinear points forming an isosceles triangle with the peripheral primaries. Non-collinear points emerge via a saddle-node bifurcation at a critical μ = μc and as μ increases further within the range μc < μ < ½ (1 – μ0), these points move away from the x-axis and gradually align closer to the y-axis, while remaining symmetric with respect to the x-axis. The stability analysis reveals that collinear libration points L1, L3 and L4 are linearly unstable under all conditions while L2 is stable in the interval 0 < μ < μ* where μ* is a critical threshold for L2. The non-collinear points are linearly stable within a defined interval μc < μ < μc1. Finally, these results are applied to the Saturn–Janus–Epimetheus system to illustrate the model’s practical relevance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The restricted three-body problem (R3BP) is a foundational model in celestial mechanics, widely used to study the motion of an infinitesimal mass under the gravitational influence of two dominant bodies, typically referred to as the primaries. Its mathematical simplicity and physical relevance make it an ideal framework for analyzing satellite trajectories, planetary motion, and stability regions in space dynamics. Over time, researchers have extended the classical R3BP to more complex configurations, including the restricted four-body, five-body, six-body, and even up to n-body problems. These extensions allow for the inclusion of additional gravitational influences, leading to more realistic and nuanced models that better represent the dynamical behavior observed in natural and artificial celestial systems. Such generalizations have significantly enriched the theoretical landscape and have practical applications in mission planning and understanding multi-body interactions in astrophysical contexts.

The foundational analytical work on the circular restricted four-body problem (CR4BP) was introduced by Michalodimitrakis1, marking the beginning of extensive research in this area. Roy and Steves2 expanded the study by examining special configurations in both symmetric and asymmetric four-body systems. Leandro3 focused on central configurations in the planar CR4BP, while Papadakis4 provided asymptotic solutions for the same. Furthering the dynamical understanding, Burgos-Garcia and Delgado5 investigated symmetric periodic orbits. The role of oblateness on stability regions was explored by Kumari and Kushvah6, and Alvarez-Ramirez et al.7 conducted a nonlinear stability analysis in the equilateral configuration. Singh and Vincent8 incorporated radiation pressure effects into the analysis of equilibrium points, whereas Barrabés et al.9 studied spatial collinear configurations under a repulsive Manev potential. Zotos10 examined equilibrium points and basins of convergence in a linear CR4BP framework with angular velocity. Chakraborty and Narayan11 extended the problem to its elliptic case. The influence of triaxiality on equilibrium dynamics was demonstrated by Muhammad et al.12. More recently, Suraj et al.13 and Alrebdi et al.14 analyzed the equilibrium dynamics in the collinear CR4BP involving non-spherical primaries. Meena and Kishor15 investigated periodic motion in the photo-gravitational planar elliptic variant, while Ma and Gao16 explored the dynamics of variable mass in a CR4BP framework considering radiating and oblate primaries.

The restricted five-body problem (R5BP) has attracted increasing attention due to its ability to model more complex gravitational systems. Ollongren17 performed an early analytical study using computer algebra techniques to analyze a specific configuration of the R5BP. Moeckel18 introduced a family of transition tori within the planar case, highlighting intricate dynamical structures. Papadakis and Kanavos19 investigated the photogravitational R5BP through numerical methods, while Zotos and Papadakis20 contributed by classifying orbits and constructing networks of periodic solutions in the planar circular configuration. Gao and Wang21 conducted a numerical study of zero velocity surfaces and transfer trajectories in the circular R5BP. The impact of variable mass on system dynamics was analyzed by Suraj et al.22, providing new insights into evolving mass conditions. Kashif and Shoaib23 examined a concave kite configuration, adding to the diversity of geometric setups. Ullah and Idrisi24 explored a particular variant known as the concentric Sitnikov problem, and subsequent work by Idrisi et al.25 delved into the motion of an infinitesimal mass in this framework. Most recently, Kumar and Awasthi26 studied the influence of perturbing forces on motion states within the R5BP, further enriching the understanding of multi-body gravitational systems.

Idrisi and Ullah27 proposed a mathematical model for the restricted six-body problem (R6BP), introducing a configuration with a dominant central primary located at the system’s center of mass. Building upon this, Idrisi et al.28 investigated the effects of perturbations due to centrifugal and Coriolis forces, revealing their influence on the system’s equilibrium structure. Kumar et al.29 further contributed by examining the basins of attraction, shedding light on the system’s stability landscape. In an extension to three-dimensional analysis, Idrisi and Ullah30 explored out-of-plane equilibrium points, enriching the spatial understanding of the R6BP. A rhomboidal configuration of the R6BP was analyzed by Siddique and Kashif31, while Suraj et al.32 discussed the associated basins of convergence, offering insight into the convergence behavior of equilibrium solutions. Additionally, Llibre and Mello33 extended the scope of multi-body configurations by studying families of planar central configurations in the more complex seven-body problem, broadening the theoretical foundation for multi-body celestial mechanics.

Idrisi et al.34 introduced a mathematical model for the circular restricted eight-body problem (R8BP), focusing on the identification and linear stability analysis of equilibrium points. Building on this framework, Saravanamoorthi et al.35 examined how radiation from a central primary affects the in-plane equilibrium points in a photo-gravitational version of the R8BP. Further advancing the model, Idrisi et al.36 extended the analysis to out-of-plane equilibrium points, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the spatial dynamics. Earlier foundational work on multi-body configurations includes Pacella’s37 application of equivariant Morse theory to the study of central configurations in the n-body problem, and Llibre’s38 identification of various central configurations. A significant contribution to the global theory was made by Qiu-Dong39, who offered a solution to the restricted n-body problem. Kalvouridis40 proposed the “ring problem”, a planar variant of the n + 1 body problem, emphasizing symmetric mass distributions. Golov and Petrusevich41 conducted a comprehensive analysis of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) Data Release 14 (DR14) dataset, which compiles extensive statistical information on a wide array of astronomical objects, including stars, galaxies, and quasars. Gilliam and Bettinger42 formulated a version of the circular restricted n-body problem tailored to the Jovian system, highlighting its practical relevance in planetary dynamics.

Recent research has explored the dynamics and trajectory design in realistic multi-body environments. For instance, Zhang et al.43 investigated the transfers from lunar distant retrograde orbits (DROs) to Earth orbits via optimization in the four-body problem, demonstrating the practical application of multi-body dynamics to mission planning in the Earth–Moon–Sun system. Similarly, Zhang et al.44 analyzed libration points and periodic orbit families near a binary asteroid system with different shapes of the secondary, highlighting how variations in body shape affect equilibrium point locations and orbital stability. In another related study, Shi et al.45 examined equilibrium points and associated periodic orbits in the gravity of binary asteroid systems, using (66,391) 1999 KW4 as an example, providing valuable insight into the stability and orbital structure of small-body systems. These works collectively emphasize that extending restricted multi-body models to realistic mass distributions and geometries can yield significant advancements in both theoretical understanding and space mission design, a direction closely aligned with the present study’s adoption of the Saturn–Janus–Epimetheus system as a physically consistent example of the collinear restricted four-body problem.

The restricted four-body problem (R4BP) has been widely used to model the motion of a negligible-mass particle under the gravitational influence of three primaries. However, most studies assume equal or nearly equal masses for the primaries, which limits the applicability of the classical formulation to real planetary systems. In many natural configurations, one central primary is overwhelmingly massive, and the two remaining primaries are much smaller but may share nearly identical orbital periods as in certain co-orbital moon systems or binary–satellite configurations. The present work focuses on such a collinear restricted four-body problem with a dominant central mass, which can accurately describe hierarchical gravitational systems satisfying the constant angular velocity condition. A prime example is the Saturn–Janus–Epimetheus system, where Janus and Epimetheus are co-orbital moons with nearly identical semi-major axes and mean motions. This choice not only ensures the model’s physical realism but also offers insights into stability properties relevant to mission planning, station-keeping strategies, and the general dynamics of co-orbital celestial bodies. By extending the CR4BP framework to include a dominant central primary and realistic mass distributions, this study bridges the gap between theoretical models and observationally consistent planetary–satellite systems.

The structure of the paper is laid out systematically: Section "Introduction" introduces notable research contributions pertinent to the study’s theme. Section "Model description and equations of motion" lays down the system’s mathematical model, detailing the equations of motion for the infinitesimal mass. Section "Existence and stability of LPs: A qualitative approach" presents both graphical and numerical solutions pertaining to the libration points. The stability of these libration points is meticulously addressed in Sect. "Existence and stability of LPs". A real application to the proposed dynamical system is shown in section "An application to the Saturn-Janus-Epimetheus system". Finally, the paper concludes with a succinct discussion and conclusion in the closing section.

Model description and equations of motion

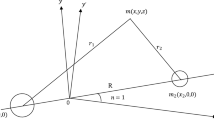

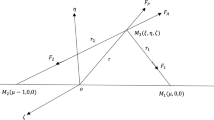

The system consists of three primary bodies Pi with masses mi (where i = 0, 1, 2). Among them, m0 is the most massive, while m1 and m2 are less massive, with m1 > m2 and (m1 + m2) < m0. The less massive bodies are positioned along a straight line and move in concentric circular orbits with radii a and b (where a < b) around most massive primary, m0, remains libration at the origin, as depicted in Fig. 1. Let ri represent the distances of the infinitesimal mass m from the primary bodies Pi. We consider a synodic coordinate system Oxyz, which initially coincides with the inertial system OXYZ and rotates with angular velocity ω = nk about the Z-axis (with the z-axis aligned with the Z-axis). By choosing the time unit such that G = 1, Σmi = 1 and a + b = 1, the two-dimensional equations of motion for the infinitesimal mass m in the synodic reference frame and dimensionless system are given by:

The potential function Θ(x, y) can be expressed as:

Here n is the mean-motion of the primaries, and.

\(\mu_{0} = \frac{{m_{0} }}{M},\,\mu = \frac{{m_{2} }}{M},\,M = \sum\limits_{i = 0}^{2} {m_{i} } = 1\),

The permissible range for the mass parameters (μ0, μ) is displayed in Fig. 2. There is a triangular-shaped area (highlighted in grey color) representing the acceptable combination of these mass parameters, within which the numerical study can be conducted.

Mean-motion of the primaries

In order to maintain the configuration of the primaries in a rotating reference frame, the sum of the gravitational forces exerted by P0 and P2 on P1 must balance the centrifugal force acting on P1. This condition ensures that P1 remains in a stable orbit and does not deviate from its position relative to the other bodies. The gravitational attractions from the two primary bodies, P0 and P2, pull P1 towards them, while the centrifugal force, caused by the rotation of the system, pushes it outward. The equilibrium between these forces ensures that the system’s configuration is maintained, i.e.,

Similarly,

Simplifying and then adding Eqs. (3) and (4) under the assumptions G = 1 and a + b = 1, we get

where \(\kappa = \left( {1 - \frac{1}{{a^{2} }} - \frac{1}{{b^{2} }}} \right) < 1\) for all μ and μ0. It is worth noting that when μ0 = 0, the problem reduces to the classical circular restricted three-body problem (CRTBP), which has been extensively studied, including the work of Szebehely46.

Existence and stability of LPs: a qualitative approach

In celestial mechanics, libration points (LPs), also known as equilibrium points or Lagrange points, refer to locations in space where an infinitesimal mass, influenced by the gravitational forces of the primaries, experiences no net force. At these points, the gravitational pull of the primaries balances with the centrifugal force due to the orbital motion of infinitesimal mass, allowing it to remain in a fixed position relative to the larger bodies.

The libration points are determined by solving the equations Θx = Θy = 0, i.e.,

The solution of Eq. (6) gives the locations of libration points in dimensionless system.

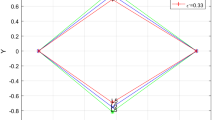

In the orbital plane of the primaries, libration points are represented graphically by the intersections of the iso-contours curves Θx(x, y) and Θy(x, y), as shown in Fig. 3, which identifies six such points, denoted as Lj (j = 1, 2, …, 6). The libration points L1,2,3,4 lie along the x-axis, while L5,6 are situated in the xy-plane, forming a symmetric triangular configuration relative to the primaries. Specifically, L1 and L4 are positioned to the left and right of P2 and P1, respectively, L2 lies between the primaries P0 and P2, and L3 is located between P0 and P1. This arrangement highlights the dynamic gravitational balance in the system.

Figure 4 illustrates the dynamics and stability characteristics of the collinear libration points for μ0 = 0.75, while μ varies within the interval (0, 0.125). As μ increases, the libration point L1 shifts progressively closer to the secondary mass m2. Meanwhile, L2 initially moves toward m2 but then slightly reverses course, edging back toward the central mass m0. The third collinear point, L3, steadily migrates toward the primary mass m1, and L4 consistently moves away from m1. In terms of stability, among the collinear libration points, only L2 exhibits stability for μ values below a critical threshold μ* = 0.0448. Beyond this value, and for the other collinear points regardless of μ, instability prevails. It is important to note that this stability threshold is specific to the case of μ0 = 0.75, and variations in μ0 may yield different critical values of μ*.

Variation in position and linear stability of the collinear libration points for μ0 = 0.75 as μ varies in the interval (0, 0.125). L1 shifts toward m2, L2 moves toward m2 and then slightly back toward m0, L3 approaches m1, and L4 recedes from m1. Stability analysis shows that only L2 remains stable for μ < μ∗ = 0.0448; all other collinear points are unstable for the full range of μ.

Figure 5 illustrates the behavior and stability of the non-collinear libration points L5,6 for μ0 = 0.75 and μ ∈ (0, 0.125). Graphical results reveal that at μ = 0.046, a bifurcation occurs, giving rise to two additional non-collinear points, L5 and L6, which emerge near the collinear point L2. As μ continues to increase, these points drift away from the x-axis and gradually align closer to the y-axis, maintaining symmetry with respect to the x-axis. Regarding their stability, L5,6 are found to be stable within a critical interval Ic = (0.046, 0.062); outside this range, i.e., for μ ≤ 0.046 and μ ≥ 0.062, they become unstable. This analysis is specific to μ0 = 0.75, and the critical interval Ic may shift for different values of μ0.

Examining the parametric evolution of the positions of the LPs, Lj, j = 1, 2, …, 6 in the concentric circular restricted four body problem, when μ0 = 0.75 and 0 < μ < 0.125. The arrows indicate the movement direction of the LPs as μ increases. The olive green dots shows the value of μ just greater than zero whereas for black dots, μ = 0.125; red dots, μ = 0.04480061; grey dots, μ = 0.046; and pink dots, μ = 0.062.

Existence and stability of LPs

In this section, we perform a numerical analysis to investigate the existence and stability of all libration points, including both collinear and non-collinear configurations. By solving the system of Eq. (6), we locate the equilibrium points and assess their stability through linearization techniques and eigenvalue analysis. This approach allows for a comprehensive understanding of the dynamic behavior near each libration point, providing insights into the nature of small perturbations and their impact on orbital stability.

Libration points

In this section, we focus on the numerical locations of collinear and non-collinear LPs for different values of μ0 and μ.

Collinear LPs

The libration points on the x-axis can be obtained by setting y = 0 in Eq. (6, we have

The Eq. (7) has three singularities at x = –b, 0 and a, and thus we have the following observations:

In the view of Eq. (6), it is evident that Eq. (7) possesses exactly one real root within each of the intervals (–∞, –b), (–b, 0), (0, a) and (a, ∞). Thus, the solution of Eq. (7) yields four real roots, denoted as xj (j = 1, 2, 3, 4), which correspond to the positions of the collinear libration points Lj(xj, 0) located within the aforementioned intervals, respectively. Due to the complexity of Eq. (7), a general analytical solution is not feasible; thus, specific solutions are computed for selected values of the parameter μ0, namely μ0 = 0, 0.55, 0.60, 0.65, 0.70, 0.75, 0.80, 0.85, 0.90 and 0.95. The mass parameter μ, constrained within the interval (0, (1 – μ0)/2) where ½ < μ0 < 1, experiences a narrowing range as μ0. It is important to highlight that the collinear libration point L1 does not exist for sufficiently small values of μ. Observationally, with increasing μ in the given range, the libration point L1 shifts closer to m2, L2 initially approaches m2 and then slightly shifts toward the central mass m0, L3 moves toward m1, and L4 progressively recedes from m1. A graphical representation of the dynamics of these libration points is presented in Fig. 4 and summarized numerically in Table 1.

Non-collinear LPs

The non-collinear libration points are determined by solving the equations Θx = Θy = 0, y ≠ 0, i.e.,

On plugging Eq. (9) into Eq. (8), we get r1 = r2 which gives x = a – ½. Now, substitute this value of x in the Eq. (9), we have

The coordinates of the non-collinear libration points are therefore given by

where y* represents the symmetric real roots of Eq. (10).

It should be noted that for μ0 = 0, the conditions r1 = r2 = 1 satisfy Eqn. (8) and (9), thereby verifying the classical case. However, for μ0 ≠ 0, the libration points L5,6(a – ½, ± y*) form an isosceles triangle with the m1 and m2. Since a general analytical solution to Eq. (10) is not feasible, we solve it numerically for various values of μ0 and μ. All corresponding results are compiled and presented in Table 2.

For μ0 = 0.55, 0 < μ < 0.225, it is observed that the Eq. (110 has no real roots in the interval 0 < μ ≤ 0.078233 while in the interval 0.078233 < μ < 0.225 it has two symmetric real roots as mentioned in the Table 2. Hence at the critical value μc ≈ 0.078233 the two non-collinear equilibria L5,6 born in a classic saddle-node bifurcation. For μ < μc there are no off-axis solutions (y = 0 is the only root), but exactly at μc, the double root at y = 0 splits into two symmetric branches: one with y > 0 (the upper triangular point L5) and with y < 0 (the lower point L6). As μ increases beyond μc, these branches rapidly separate, with | y | growing. The accompanying bifurcation diagram (Fig. 6) clearly shows that the emergence of the two off-axis solutions from a single degenerate root at μc, making the onset of the triangular configuration.

Bifurcation diagram for μ0 = 0.55 showing the emergence of non-collinear libration points L5 and L6 as μ increases. No off-axis solutions exist for 0 < μ ≤ μc ≈ 0.0782330. At μ = μc, a saddle-node bifurcation occurs, where the double root at y = 0 splits into two symmetric branches corresponding to L5 (y > 0) and L6 (y < 0). For μ > μc, these points separate with ∣y∣ increasing as μ grows.

Similarly, for a specific μ0 there exist a critical interval 0 < μ < μc in which non-collinear libration points do not exist. At μ = μc, a saddle-node bifurcation occurs, and giving rise to two symmetric non-collinear libration points. As μ increases further within the range μc < μ < (1 – μ0)/2, these points move away from the x-axis and gradually align closer to the y-axis, while remaining symmetric with respect to the x-axis. This critical value μc for different μ0 is given in Table 3. The plot of μc versus μ0 reveals a steadily decreasing trend, indicating an inverse or exponential decay-like relationship between the two variables, Fig. 7. As μ0 increases from 0.55 to 0.98, the corresponding values of μc drop sharply from approximately 0.078 to 0.0037. This suggests that small increases in μ0 initially cause significant reductions in μc, while further increases have diminishing effects.

Stability of LPs

To discuss the linear stability of libration points Li, (i = 1, 2, …, 6), we perturb the libration point L(x0, y0) to L*(x0 + ξ, y0 + η), where ξ, η < < 1. Now, linearizing the system (1), we get the variational equations of motion as:

where ‘o’ indicates that the partial derivatives are to be calculated at the libration points under consideration.

The partial derivatives in system of Eq. (11) are defined as follows:

The characteristic equation that corresponds to the system of Eq. (12) is given by

A libration point L(x0, y0) is considered stable if all characteristic roots of Eq. (13) have either a strictly negative real value, if they are real, or negative real part, if they are complex. This ensures that small perturbations about the libration point will decay with time and all trajectories in the system’s phase space will converge to the libration point L(x0, y0) or at least orbit close to it. In simpler terms, there is no tendency towards uncontrolled growth or oscillations that move away from equilibrium. As such, the sign of the real part of the characteristic roots determines most of the local stability behavior close to the libration point.

Stability of collinear LPs

For the collinear libration points, L1,2,3,4(x1,2,3,4, 0) the characteristic Eq. (13) reduces to

where \(\Lambda = \lambda^{2} ,\,\,\Xi (x_{i} ) = 4n^{2} - \mathop \Theta \limits^{0}_{xx} \left( {x_{i} ,0} \right) - \mathop \Theta \limits^{0}_{yy} \left( {x_{i} ,0} \right);\,\,\Gamma (x_{i} ) = \mathop \Theta \limits^{0}_{xx} \left( {x_{i} ,0} \right)\mathop \Theta \limits^{0}_{yy} \left( {x_{i} ,0} \right),\,\,i = 1,2,3,4\)

The roots of the characteristic Eq. (14) for collinear libration points L1,2,3,4(x1,2,3,4, 0) are given by

Consequently, the eigenvalues of characteristic Eq. (12) can be expressed as:

When plotting the values of Λ1,2 for μ0 = 0.75 within the range 0 < μ < 0.125 for the libration point L1, it is observed that Λ1 > 0 while Λ2 < 0, as shown in Fig. 8. This indicates that the libration point L1 is a saddle-center point and hence linearly unstable. This behavior is not limited to this specific case but holds true for other values of μ0 as well, across the collinear libration points L1,3,4(x1,3,4, 0), confirming their inherent linear instability.

In contrast, for libration point L2, Λ1,2 < 0 in the interval 0 < μ < μ* where μ* = 0.0448 as illustrated in Fig. 9. As a result, the eigenvalues of the characteristic Eq. (14) are purely imaginary within this range, indicating that L2 behaves as a center and is thus linearly stable. This result holds for other values of μ0 as well, although the corresponding value μ* of will vary accordingly.

Variation of the characteristic roots Λ1,2 for the libration point L2 with μ0 = 0.75. For 0 < μ < μ∗ = 0.04480, both Λ1 and Λ2 are negative, yielding purely imaginary eigenvalues of the characteristic Eq. (14) and indicating that L2 behaves as a center and is linearly stable.

Stability of non-collinear LPs

The characteristic Eq. (12) for non-collinear libration points L5,6 reduces to

where

The roots of the characteristic Eq. (14) are therefore given by

where Δ = φ2 – 4Ψ.

As previously discussed, for a fixed value of μ0 there exist an open interval μc < μ < (1 – μ0)/2 within which non-collinear LPs exist. In order to analyze the characteristic roots of the Eq. (15), we consider μ0 = 0.55, leading to the interval 0.078233 < μ < 0.225. Within this range, it is observed that both φ > 0 and Ψ > 0, indicating certain stability conditions. However, the discriminant Δ > 0 only within the narrower interval 0.078233 < μ < 0.0897961, as depicted in Fig. 10. Consequently, Π1,2 < 0 within this same subinterval as depicted in Fig. 11, implying that the characteristic roots of Eq. (13) are purely imaginary. This confirms that the non-collinear libration points are linearly stable within this narrower subinterval.

Variation of the stability parameters φ, Ψ, and discriminant Δ for the non-collinear libration points with μ0 = 0.55. While φ > 0 and Ψ > 0 for the full range 0.078233 < μ < 0.225, the discriminant satisfies Δ > 0 only in the narrower interval 0.078233 < μ < 0.0897961, indicating potential stability in this subinterval.

Variation of Π1,2 for the non-collinear libration points with μ0 = 0.55. Both Π1,2 < 0 only within the interval 0.078233 < μ < 0.0897961, implying that the characteristic roots of Eq. (13) are purely imaginary and confirming the linear stability of the non-collinear points in this range.

For other values of μ0, there always exists an interval μc < μ < μc1 within which the non-collinear libration points exhibit linear stability. In this context, μc and μc1 represent the critical lower and upper bounds, respectively, of the interval where the conditions φ > 0, Ψ > 0 and Δ > 0 are simultaneously satisfied. These conditions are both necessary and sufficient to ensure the linear stability of the libration points. The existence of such an interval for varying μ0 highlights the sensitivity of the stability behavior to changes in system parameters, and it emphasizes the importance of precisely identifying the ranges of μ for which the stability criteria are met.

An application to the Saturn-Janus-Epimetheus system

To illustrate the applicability of the proposed collinear restricted four-body problem (CR4BP) with a central dominant mass, we consider a dynamical configuration involving Saturn and two of its co-orbital moons: Janus and Epimetheus orbit with nearly the same angular velocity in an inertial frame. This configuration satisfies the assumptions of our model namely, a dominant central mass with two peripheral primaries in concentric and nearly circular orbits. It provides a realistic example of a gravitational system where libration points and their stability can be meaningfully studied.

From the astrophysical data, Lang 47, we have:

Mass of Saturn (m0): 5.683 × 1026 kg.

Mass of Janus (m1): 1.98 × 1018 kg.

Mass of Epimetheus (m2): 5.6 × 1017 kg.

Mean orbital radius of Janus (a): 151,472 km.

Mean orbital radius of Epimetheus (b): 151,422 km.

In dimensionless system, we have

Therefore, on solving Eq. (6), the libration points in the Saturn-Janus-Epimetheus system are determined, as presented in Table 4. The analysis reveals the existence of four collinear libration points (L1, L2, L3 and L4) and two symmetric non-collinear points (L5,6). The first two points lie on the Saturn–Epimetheus side, one between Saturn and Epimetheus and the other outside Epimetheus, while the remaining two points are situated analogously on the Saturn–Janus side. The positions of the collinear points reflect the near-symmetry of the system, with only minute asymmetries due to the small difference in orbital distances of Janus and Epimetheus from Saturn. Meanwhile, the non-collinear libration points L5,6 exhibit a symmetric layout, forming an isosceles triangle with Janus and Epimetheus. This geometric arrangement emphasizes the balanced gravitational dynamics and highlights the structural symmetry inherent in the system.

Furthermore, we have examined the linear stability of the libration points by evaluating the characteristic Eq. (13) at each equilibrium configuration. The computed eigenvalues indicate that all collinear libration points possess one real pair and one purely imaginary pair of roots, corresponding to a saddle–center structure in the phase space. This confirms their linear instability, as perturbations along the unstable manifold grow exponentially. In contrast, the non-collinear libration points exhibit purely imaginary eigenvalues forming two center modes, which implies linear stability in the sense of Lyapunov. The numerical values of the characteristic roots for each point, which substantiate these conclusions, are listed in Table 4.

Discussion

This study presents a generalized framework of the circular restricted four-body problem (CR4BP) by introducing a centrally dominant primary mass positioned at the system’s center of mass. This extension not only encapsulates more realistic gravitational dynamics seen in planetary systems such as the Sun–Jupiter–Saturn configuration but also preserves theoretical continuity with the classical circular restricted three-body problem (CR3BP), which is recovered as a limiting case when the central mass parameter μ₀ approaches zero.

Through analytical derivation and numerical validation, we identified the conditions under which the system admits equilibrium points and remains dynamically viable. Specifically, it was shown that equilibrium configurations exist for 0.5 < μ0 < 1 and 0 < μ < (1 – μ0)/2, ensuring the non-degeneracy of primary placements. The system exhibits six libration points: four collinear and two symmetric non-collinear points. A critical bifurcation value μc was established, beyond which the non-collinear libration points emerge and gradually transition toward the y-axis while maintaining symmetry.

Stability analysis revealed that collinear points L1, L3, and L4 are linearly unstable, while L2 maintains stability for μ < μ*. Moreover, the non-collinear libration points exhibit linear stability within a well-defined mass range μc < μ < μc1, varying with the central mass μ0. These findings contribute significantly to our understanding of equilibrium structures and their stability in multi-body gravitational systems.

Finally, by applying the model to the Saturn-Janus-Epimetheus system, we demonstrated its practical relevance in astrophysical contexts. The model offers valuable insights for future studies in celestial mechanics, mission trajectory design, and the long-term dynamical evolution of multi-planet systems. Future work may extend this model to include additional forces such as radiation pressure, relativistic corrections, or non-circular primary orbits for broader applicability.

Conclusion

We have presented a comprehensive analysis of the collinear restricted four-body problem with a dominant central mass, supported by both analytical derivations and numerical computations. By adopting the Saturn–Janus–Epimetheus system as a physically consistent real-world application, we ensured that the constant angular velocity assumption of the CR4BP is closely satisfied. The computed mean motion, equilibrium positions, and corresponding stability properties reveal that all collinear libration points in this configuration are linearly unstable, while non-collinear libration points are found linearly stable.

This study underscores the importance of selecting dynamically consistent planetary systems when applying the CR4BP to real-world scenarios. The results may serve as a reference for future work exploring similar co-orbital satellite systems or artificial multi-body configurations. Potential extensions of this work include incorporating small perturbations such as solar radiation pressure, oblateness, and orbital eccentricity to examine how these effects might alter the existence and stability of equilibrium points in both natural and engineered space environments.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Michalodimitrakis, M. The circular restricted four-body problem. Astrophys. Space Sci. 75, 289–305 (1981).

Roy, A. E. & Steves, B. A. Some special restricted four-body problems: II. From Caledonia to Copenhagen. Planet Sp Sci 46, 1475–1486 (1998).

Leandro, E. S. G. On the central configurations of the planar restricted four-body problem. J. Differ Equ 226, 323–351 (2006).

Papadakis, K. E. Asymptotic orbits in the restricted four-body problem. Planet. Space Sci. 55, 1368–1379 (2007).

Burgos-Garcia, J. & Delgado, J. Periodic orbits in the restricted four-body problem with two equal masses. Astrophys. Space Sci. 345, 247–263 (2013).

Kumari, R. & Kushvah, B. S. Stability regions of equilibrium points in restricted four-body problem with oblateness effects. Astrophys. Space Sci. 349, 693–704 (2014).

Alvarez-Ramirez, M., Skea, J. E. F. & Stuchi, T. J. Nonlinear stability analysis in a equilateral restricted four-body problem. Astrophys. Space Sci. 358, 3 (2015).

Singh, J. & Vincent, A. E. Equilibrium points in the restricted four-body problem with radiation pressure. Few-Body Syst. 57, 83–91 (2016).

Barrabes, E., Cors, J. M. & Vidal, C. Spatial collinear restricted four-body problem with repulsive Manev potential. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 129, 153–176 (2017).

Zotos, E. E. Equilibrium points and basins of convergence in the linear restricted four-body problem with angular velocity. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 101, 8–19 (2017).

Chakraborty, A. & Narayan, A. A new version of restricted four-body problem. New Astron. 70, 43–50 (2019).

Muhammad, S., Duraihem, F. Z. & Zotos, E. E. On the equilibria of the restricted four-body problem with triaxial rigid primaries: I oblate bodies. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 142, 110500 (2021).

Suraj, M. S., Bhushan, M. & Asique, M. C. A study of the equilibrium dynamics of the test particle in the collinear circular restricted four-body problem with non-spherical central primary. Astron Comput 48, 100831 (2024).

Alrebdi, H. I., Al-mugren, K. S., Dubeibe, F. L., Suraj, M. S. & Zotos, E. E. On the equilibrium points of the collinear restricted four-body problem with non-spherical bodies. Astron Comput 48, 100832 (2024).

Meena, P. & Kishor, R. On the periodic motion in the photo-gravitational planar elliptic restricted four body problem. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 180, 114525 (2024).

Ma, B. & Gao, F. A dynamic behavior of variable mass R4BP with radiating and oblate primaries. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 191, 115853 (2025).

Ollongren, A. On a particular restricted five-body problem an analysis with computer algebra. J. Symb. Comput. 6, 117–126 (1988).

Moeckel, R. Transition tori in the five-body problem. J. Differ Equ 129, 290–314 (1996).

Papadakis, K. E. & Kanavos, S. S. Numerical exploration of the photogravitational restricted five-body problem. Astrophys. Space Sci. 310, 119–130 (2007).

Zotos, E. E. & Papadakis, K. E. Orbit classification and networks of periodic orbits in the planar circular restricted five-body problem. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 111, 119–141 (2017).

Gao, F. B. & Wang, R. F. Numerical study of the zero velocity surface and transfer trajectory of a circular restricted five-body problem. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 7489120 (2018).

Suraj, M. S., Abouelmagd, E. I., Aggarwal, R. & Mittal, A. The analysis of restricted five-body problem within frame of variable mass. New Astron. 70, 12–21 (2019).

Kashif, A. R. & Shoaib, M. Restricted concave kite five-body problem. Adv Astron 2023, 9434141 (2023).

Ullah, M. S. & Idrisi, M. J. The concentric Sitnikov problem: Circular case. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 174, 113911 (2023).

Idrisi, M. J., Ullah, M. S., Ershkov, E. & Prosviryakov, E. Y. Dynamics of infinitesimal body in the concentric restricted five-body problem. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 179, 114448 (2024).

Kumar, S. & Awasthi, A. K. Characterizing motion states in the restricted five-body problem with perturbing forces. Few-Body Syst. 66, 17 (2025).

Idrisi, M. J. & Ullah, M. S. Central body square configuration of restricted six-body problem. New Astron. 79, 101381 (2020).

Idrisi, M. J., Ullah, M. S. & Sikkandhar, A. Effect of perturbations in coriolis and centrifugal forces in the restricted six-body problem. J. Astronaut. Sci. 68, 4–5 (2021).

Kumar, V., Idrisi, M. J. & Ullah, M. S. Unpredictable basin boundaries in restricted six-body problem with square configuration. New Astron. 82, 101451 (2021).

Idrisi, M. J. & Ullah, M. S. Motion around out-of-plane equilibrium points in the frame of restricted six-body problem under radiation pressure. Few-Body Syst. 63, 50 (2022).

Siddique, M. A. R. & Kashif, A. R. The restricted six-body problem with stable equilibrium points and a rhomboidal configuration. Adv Astron 2022, 8100523 (2022).

Suraj, M. S., Alhowaity, S. & Aggarwal, R. Fractal basins of convergence in the restricted rhomboidal six-body problem. New Astron. 94, 101798 (2022).

Llibre, J. & Mello, L. F. New central configurations for the planar 7-body problem. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 10, 2246–2255 (2009).

Idrisi, M. J., Ullah, M. S., Mulu, G., Tenna, W. & Derebe, A. The circular restricted eight-body problem. Arch. Appl. Mech. 93, 2191–2207 (2023).

Saravanamoorthi, P., Idrisi, M. J. & Ullah, M. S. Effect of radiations on in-plane equilibrium points due to central primary in the photo-gravitational restricted eight-body problem. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 175, 113985 (2023).

Idrisi, M. J. et al. Out-of-plane dynamics: a study within the circular restricted eight-body problem. New Astron. 111, 102260 (2024).

Pacella, F. Central configurations of the N-body problem via equivariant Morse theory. Arch Ration Mech Anal 97, 59–74 (1987).

Llibre, J. On the number of central configurations in the N-body problem. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 55, 89–96 (1990).

Qiu-Dong, W. The global solution of the N-body problem. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 50, 73–88 (1990).

Kalvouridis, T. J. A planar case of the n+1 body problem: The ‘ring’ problem. Astrophys. Space Sci. 260, 309–325 (1998).

Golov, V. A. & Petrusevich, D. A. On the choice of a method for recognizing astronomical objects based on the analysis of initial data obtained using the Sloan digital sky survey DR14 program. Rus Technol J 9, 66–77 (2021).

Gilliam, A. J. & Bettinger, R. A. Formulation of the circular restricted N-body problem (CRNBP) in the Jovian system. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 136, 54 (2024).

Zhang, R., Wang, Y., Zhang, C. & Zhang, H. The transfers from lunar DROs to Earth orbits via optimization in the four body problem. Astrophys. Space Sci. 366, 49 (2021).

Zhang, R., Wang, Y., Shi, Y. & Xu, S. Libration points and periodic orbit families near a binary asteroid system with different shapes of the secondary. Acta Astronaut. 177, 15–29 (2020).

Shi, Y., Wang, Y. & Xu, S. Equilibrium points and associated periodic orbits in the gravity of binary asteroid systems: (66391) 1999 KW4 as an example. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 130, 32 (2018).

Szebehely, V. Theory of orbits, the restricted problem of three bodies (Academic Press, Cambridge, 1967).

Lang, K. R. Astrophysical data: Planets and stars (Springer, Berlin, 1992).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J.I. and M.S.S. wrote the main manuscript text, S.E. and E.I.A. prepared all the figures and D.B. performed all the numerical simulation. Finally, all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding publication of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Idrisi, M.J., Suraj, M.S., Ershkov, S. et al. A generalized framework for the collinear restricted four-body problem with a central dominant mass. Sci Rep 15, 36440 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20510-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20510-y