Abstract

The seawater greenhouse (SWGH) is an environmentally friendly solution that utilizes solar-driven desalination techniques to produce freshwater while simultaneously creating a controlled agricultural environment. Integrating SWGH with green buildings optimizes sustainability by reducing dependence on conventional water supplies and lowering carbon emissions. This study develops a deep learning-based predictive model to optimize freshwater production in SWGHs, particularly in the Makran region. The Makran coast faces severe freshwater shortages due to its arid climate, limited groundwater resources, and growing agricultural demand. SWGH technology is particularly suitable for this region, leveraging abundant solar radiation and seawater to sustainably generate freshwater while enhancing agricultural productivity and environmental resilience. This study aims to develop a deep learning-based predictive model to forecast freshwater production in SWGHs for integration into green building frameworks. The model forecasts freshwater yield by analyzing environmental, especially climate and operational parameters. A two-stage deep learning-based prediction approach was employed, utilizing CNN-LSTM, BiLSTM, BiGRU, CNN-GRU, and MLP models. First, global horizontal irradiance (GHI) was predicted as a primary factor influencing SWGH performance. Then, freshwater production was estimated using predicted solar radiation. Among tested models, CNN-LSTM achieved the highest accuracy with achieving a R2 of 0.9727, a RMSE of 0.0021, and a MSE of 0.0022. The freshwater production rate was predicted per unit area, and the average annual yield for 2024–2033 was estimated at 1454.25 L/m². The results confirm SWGH as a viable solution for sustainable water management in arid coastal regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global issues such as water scarcity, climate change, and demand for more food necessitate the application of new approaches in agriculture. Water scarcity, which has been described as the insufficient availability of freshwater to meet demand, is a major constraint to food security, public health, and economic growth1. Excessive use of freshwater resources poses an increasing risk to agricultural productivity. It is projected that nearly 2.3 billion individuals live in water-stressed countries and consume nearly 70% of the world freshwater resources. This reliance poses a significant risk to food security in such areas as sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Approximately two-thirds of the world’s population experience severe water scarcity at least one month of the year2. The population exposed to water scarcity increased from 0.24 billion in the 1900 s to 3.8 billion in the 2000s. Climate change and urbanization are exacerbating this issue, with projections suggesting 1.693–2.373 billion urban dwellers will face water scarcity by 2050. India will be the most severely affected, with 153–422 million additional water-scarce urban dwellers. The major cities experiencing water scarcity are expected to rise from 193 to 193–2843. Addressing water scarcity challenges requires consideration of uncertainties in water availability projections and the development of tailored interventions4. Potential solutions include infrastructure investment, improved water-use efficiency, and better resource sharing.

It is driven by increasing water demands, dwindling resources, and contamination, facilitated by urbanization, climate change, and agriculture5,6. Seawater greenhouse (SWGH) technology, which was developed in the early 1990 s by Charlie Paton, employs seawater to cool and humidify greenhouse air to stimulate plant growth and produce freshwater via condensation. Successful trials in locations such as the Canary Islands and Australia have proven its effectiveness, and it has been the subject of research and development activities7. The population affected by water scarcity has increased from 0.24 billion in the 1900 s to 3.8 billion in the 2000 s, with water consumption rising fourfold8. Some attribute scarcity to arid environments or insufficient basin-scale water, while others blame poor water management9. Water shortage must be alleviated by an integrated approach of pollution control, rainwater harvesting, desalination techniques, aquifer replenishment, and water recycling technologies. Public awareness and cooperative measures at high levels are required for the successful management of water resources. Conventional agricultural practices that depend on freshwater resources are becoming increasingly unsustainable, especially in semi-arid and arid regions, and hence the necessity for new-generation farming technologies10. One of the most encouraging innovations is the seawater greenhouse, which offers a promising solution by utilizing ample seawater to produce ideal conditions for the cultivation of crops11. Agriculture utilizes about 70–87% of the world’s freshwater resources, and this poses tremendous challenges both in quantity and quality of water12. Heightened food production demand, along with economic growth and population increase, has resulted in agricultural activities that are highly dependent on the use of fertilizers and pesticides13.

Agricultural runoff causes eutrophication and threatens biodiversity. Optimization of irrigation efficiency, conservation strategies, and control of soil erosion are recommended by experts14. Adaptation strategies include choosing crops and irrigations according to local circumstances with the aim of reducing the pressure generated by increased food demand on land and water resources. Without technological advances, significant price adjustments for land, water, and food may be necessary15. A novel solution for freshwater shortages in coastal areas involves solar-thermal desalination technology, driven sustainably and effectively by solar energy using a humidification-dehumidification cycle, and is environmentally friendly. Seawater greenhouses employ solar desalination and evaporative cooling for plants to grow optimally, decreasing the dependency on freshwater resources and fighting the severe desert and coastal climates. This technology is in harmony with international sustainability goals, serves both environmental and food security issues, and has shown higher crop yields than traditional agriculture, thus being promising for raising food output in dry lands.

One of the primary advantages of seawater greenhouses is that they can generate freshwater in arid environments, thereby minimizing the dependence on external water sources. Research confirms that seawater greenhouses can cut water consumption by up to 90% when compared to conventional open-field farming with the same climatic conditions16. Moreover, seawater greenhouses utilize renewable forms of energy such as solar energy, which minimizes carbon emissions and lowers the demand for fossil fuels. The combination of solar power and SWGH technology can enhance sustainability by lowering operational costs17. Greenhouses promote sustainable agriculture by saving freshwater and energy, reducing the environmental impact of traditional farming methods. They also offer a potential solution to food security in water-scarce regions18. The initial cost of constructing an SWGH can be high, particularly in remote locations. Seawater and construction material transport infrastructure can also contribute to the costs19. The seawater environment also presents some maintenance problems, such as corrosion of materials and biofouling of equipment and pipes. These can contribute to operating costs and complexity in terms of sustaining the system in the long run20. Scaling up SWGH technology to a level that can significantly impact global food production is still a challenge. Factors such as land availability, economic feasibility, and technical know-how can affect its scalability21. While the SWGH reduces freshwater consumption, the disposal of concentrated brine from the desalination process remains an environmental concern. There must be good brine management practices to mitigate the potential harm to marine ecosystems22.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being utilized in seawater greenhouses to increase agricultural yields and optimize water usage. AI regulates and supervises the greenhouse climate, thereby ensuring ideal growth conditions and effective desalination23. Sensors monitor a range of parameters, including temperature, humidity, solar radiation, and the health of the plants. AI algorithms then analyze the data to modulate ventilation, cooling, and irrigation management, and hence create an ideal microclimate for the crops24. AI also regulates the evaporation and condensation of seawater based on external weather conditions, ensuring consistent freshwater production. For instance, Lawal et al.25 introduced an improved method for optimizing humidification-dehumidification desalination systems through the use of hybrid machine learning optimization method. The study examined the efficiency of a neuro-fuzzy model, a decision algorithm derived from a boosted tree, and a simple averaging ensemble in improving the performance of humidification-dehumidification systems. Data-driven methods have shown promise in improving seawater greenhouse performance and control. Machine learning approaches, such as multilayer perceptron models and support vector clustering, have been used to develop predictive models for greenhouse climate control26,27,28. These models, integrated with data-driven robust model predictive control (DDRMPC) frameworks, have demonstrated superior performance in maintaining optimal greenhouse conditions while reducing energy consumption29. DDRMPC approaches have been shown to outperform traditional rule-based control methods, resulting in lower total costs and reduced constraint violations. In the example of seawater greenhouses, empirical models were constructed for predicting the performance of condensers, a parameter that is very important for the overall system effectiveness30. These data-driven methods have proven very effective in solving the problem of climate control in greenhouses that are subjected to extreme weather conditions, i.e., high temperature and humidity. In recent years, the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence technologies and data-driven modeling techniques has introduced new solutions to these issues.

Mahmood et al.31 created a data-driven, robust model predictive control framework that ensures precise temperature control and notable energy savings, even in the face of uncertainty. These findings indicate that data-driven approaches for predicting greenhouse temperatures warrant further investigation. Additionally, deep learning techniques are receiving increasing attention for time series prediction32. Additionally, deep learning models are capable of handling large-scale, high-dimensional, and multi-modal data, effectively uncovering intrinsic correlations and significantly enhancing prediction accuracy33. According to the current era’s high industrialization, energy usage has surged to previously unheard-of levels, worsening the environment and lead to greenhouse gas emissions34. Huang et al.35 used a gated recurrent unit (GRU) to forecast the lowest temperature, achieving better performance than other models, even with exclusive input parameters. However, because of the sophisticated and changeable nature of greenhouse environments, current approaches face difficulties in providing highly accurate forecasting, while also being developed for various approaches and effective under intense conditions. Therefore, it is crucial to explore combined deep learning models that leverage their individual strengths, address severe conditions in different locations.

Additionally, Subramaniam et al.36 explored an effective combination of deep learning (DL) and dimensionality reduction (DR) methods for predicting crop yield (CYP) of regional crops in India. The innovation of the suggested method lies in the integration of DL, DR, and WTDCNN methods for exact crop productivity forecast. Furthermore, Jun et al.37 introduced a temperature forecast model based on Informer, a variant of the Transformer architecture that is better suited for time series data. BiLSTM is a sequence modeling technique derived from recurrent neural networks, which is effective at using data, is combined with Transformer. BiLSTM has improved in various sectors38. Jiang et al.39 suggested an indoor temperature prediction model that combines attention mechanisms and LSTM, achieving high performance forecasting. Furthermore, to obtain a precise and comprehensive prediction of the short- and mid-term sea surface temperature (SST) field, Xiao et al.40 investigated a spatiotemporal deep learning model capable of capturing the correlations of SST across both spatial and temporal dimensions.

Golabi et al.41 proposes an optimal real-time management method using reinforcement learning to minimize the total daily operation cost of an RO desalination plant with a storage tank system, optimizing energy use and water quality to meet varying freshwater demands. Reza et al.42 provides a comprehensive review of the use of Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) in water treatment and desalination, covering its applications in automatic forecasting, resolving missing data issues, and comparing it with conventional modeling approaches. Al Ghamdi43 proposes a novel control strategy for seawater reverse osmosis desalination using an Interpolation and Exponential Function-centered Deep Learning Neural Network (IEF-DLNN) and multi-objective optimization, which demonstrates better performance compared to existing methodologies. Bueso et al.44 presents a novel approach using a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) to estimate evaporated water mass in cooling tower systems for Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD) desalination, demonstrating improved performance over traditional linear regression and robustness in capturing key variables, with potential applications across different environmental contexts. Ashraf et al.45 use machine learning and optimization to improve the efficiency of Multi-Effect Desalination systems by identifying optimal operating conditions for maximum distillate production, thereby enhancing operational excellence and contributing to the circular economy in desalination.

Collectively, these studies establish a state-of-the-art framework for integrating AI, remote sensing, and predictive analytics to optimize agricultural productivity, resource use, and food-system resilience from production to distribution. Table 1 presents an overview of various models for seawater greenhouses.

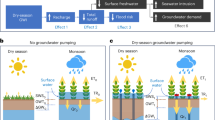

However, existing studies have not extensively explored the integration of this technology into green buildings or the use of deep learning models for optimizing freshwater production. A research gap remains in predictive models that forecast freshwater yield based on climatic parameters. Despite the promising potential of SWGH technology, existing studies have not thoroughly examined its incorporation into green building frameworks or the application of advanced deep learning models for optimizing freshwater production. Current research lacks predictive models that accurately estimate freshwater yield based on climatic parameters, creating a gap in optimizing SWGH efficiency for long-term water sustainability. This study aims to develop a deep learning-based predictive model for forecasting freshwater production in seawater greenhouses, particularly in the Makran region. The predictive models utilized in this research include BiGRU, BiLSTM, CNN-GRU, CNN-LSTM, and MLP. Initially, the most effective deep learning model among these is identified. Using this prediction, GHI is forecasted, which then enables the estimation of freshwater productivity per surface between 2024 and 2033, employing seawater greenhouse technology in green buildings along the Makran coast. By integrating renewable energy and artificial intelligence, the system aims to improve the efficiency and reliability of SWGH operations within green building applications. Figure 1 shows the mind map of data-driven method innovation in seawater greenhouse.

System description

Seawater greenhouse is a modern and up-to-date method that easily integrates into green-focused architectural systems, providing an environmentally friendly solution for managing significant global issues like water shortage and energy utilization57. The method employs the process of seawater evaporation to regulate the temperature in the greenhouse, thereby establishing a humid climate for plant development along with producing freshwater through condensation58. Furthermore, the passive seawater evaporation cooling system has the capacity to cut down the consumption of traditional air conditioning systems, further promoting building energy efficiency. The technique harnesses renewable resources to provide a mode of sustainable development activities. The approach integrates the rich resource of seawater and the renewable energy potential of solar radiation to develop a sustainable mechanism with the potential to generate freshwater and facilitate agricultural processes in areas of aridity or water stress. This system is not only designed to provide an efficient means for seawater desalination; it is also designed to achieve optimum energy efficiency, thus reducing the use of fossil fuels drastically59. With solar energy being used for heating and electricity, the seawater greenhouse reduces carbon emissions and aligns with global efforts to combat climate change. It also creates a controlled microclimate within the greenhouse, enabling the growing of plants and farm productivity without any loss of resources. This dual function generation of drinking water and promotion of agricultural sustainability renders it an innovative component of green building designs. By integrating high-technology components into natural processes, the seawater greenhouse illustrates the ability of innovative engineering to resolve multifaceted environmental issues, thereby addressing the larger objectives of sustainability and resource conservation. This is a big leap towards developing robust systems in alignment with ecological principles, hence a sustainable future. Figure 2 represents the distribution of countries involved in seawater greenhouse projects.

First, seawater is drawn from the ocean into a primary treatment system, where large particles are filtered out to avoid downstream components, including the condenser, from contamination. This also works to keep salt out of the condenser. Second, the treated seawater flows into the greenhouse condenser, where it delivers cooling and humidity control, creating optimal conditions for plant growth. The seawater is then directed into a parabolic solar collector, where it is heated to its saturation temperature before being conveyed through a three-way valve into the evaporator. In the evaporator, the seawater undergoes a phase transition to superheated steam. The parabolic solar collector effectively collects a large amount of solar radiation during daylight hours; however, supplemental support is required at night. In order to sustain operation during these times, a thermal storage system is included in the cycle. It accumulates excess heat produced during the daytime and feeds it at night, thereby enabling round-the-clock system operation. The three-way valve connects the thermal energy storage device to the evaporator60. Superheated steam is blown by a blower into the condenser, where it undergoes cooling to the dew point, causing distilled water droplets to form on the surface of the condenser. The role of coolant is played by seawater, which is circulated throughout the condenser and thus enhances the efficiency of the distillation process. The distilled water collected is lastly kept in a tank for use in irrigation or to supply buildings with water requirements. Figure 3 illustrates a schematic diagram of the seawater greenhouse cycle integrated with a green building.

The schematic of the seawater greenhouse cycle integrated with a green building61.

The new system greatly minimizes environmental pollution and the use of fossil fuels, highly meeting the Climate Change Organization criteria for sustainability. By integrating solar panels, the system generates renewable energy to power its pumps and other components, optimizing overall energy efficiency and keeping operations environmentally friendly. Solar energy coupled with seawater is a great instance of dedication to harnessing abundant natural resources, thus reducing carbon footprints and preserving limited energy reserves. The seawater greenhouse is a model of sustainable building practice, highlighting the importance of resource efficiency and environmental equilibrium. Technology not only reduces the environmental impact associated with water production but also reduces greenhouse gas emissions by far, thus helping to combat climate change. Also, by fostering sustainable production of drinking water and providing favorable conditions for agricultural production, it enhances sustainable agriculture in areas where water scarcity is a significant problem. As a key element of sustainable infrastructure, this system responds to environmental challenges on a global scale while enhancing the resilience of communities suffering from water shortages and climate stresses. Its pairing of renewable technologies with clever design renders it an innovative response striving to deliver greater sustainability and a climate-resilient future.

Methodology

Governing equations

The parameters applied to assess the performance of the hybrid desalination system in this study include freshwater production, inlet water flow rate to desalination plant, \(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{p}\text{u}\text{m}\text{p}}\), \(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{c}\text{o}\text{l}\text{l}\text{e}\text{c}\text{t}\text{o}\text{r}}\), \(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{e}\text{v}\text{a}\text{p}\text{o}\text{r}\text{a}\text{t}\text{o}\text{r}}\), \(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{c}\text{o}\text{n}\text{d}\text{e}\text{n}\text{s}\text{e}\text{r}}\). After extracting the experimental results, each of the performance parameters of the desalination system was calculated using thermodynamic relations based on the laws of mass and energy conservation. The laws of mass and energy conservation were implemented to each component of the system. It is worth mentioning that the vapor flow rate (\(\:{\dot{\text{m}}}_{\text{W}})\) was assumed to be constant throughout the cycle. The energy required and the efficiency of pumping seawater from the ocean into the primary treatment system is given by Eq. (1) and Eq. (2) :

The thermal power input into the water in the parabolic solar water heater is calculated using the Eqs. (3) and (4)62.

The governing equations for the performance of the evaporator are determined with Eq. (5) to (7)63.

The evaporator efficiency or the effectiveness of the humidification process (\(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{e}\text{v}\text{a}\text{p}\text{o}\text{r}\text{a}\text{t}\text{o}\text{r}}\)) is obtained in Eq. (8).

(\(\:{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{o},\text{e}\text{v}\text{a}\text{p},\text{}\text{s}}\)) is the absolute humidity corresponding to the condition when the vapor exiting the evaporator is saturated.

The governing equations for the performance of the condenser are determined with Eq. (9) to (11)64.

The condenser efficiency or the effectiveness of the dehumidification process (\(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{c}\text{o}\text{n}\text{d}\text{e}\text{n}\text{s}\text{e}\text{r}}\)) is obtained using the Eq. (12).

(\(\:{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{o},\text{c}\text{ondenser}\text{,}\text{s}}\)) is the absolute humidity corresponding to the condition when the vapor exiting the condenser is at a temperature equal to the condenser temperature and in a saturated state.

The latent heat of vaporization (\(\:{\text{h}}_{\text{f}\text{g}}\)) is used. The final amount produced water in the seawater greenhouse cycle is obtained in Eq. (13).

Deep learning models

Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM)

LSTM is a particular kind of RNN specifically engineered for addressing the vanishing gradient issue. LSTM networks include an advanced architecture that enables them to efficiently track and learn long-term dependencies in sequential data. The BiLSTM developed in this study comprises two autonomous LSTMs: the forward LSTM and the backward LSTM. The final learning outcome is achieved by integrating the forward and reverse input sequences, weighed appropriately, while concurrently analyzing data from both past and future sequences65. The specific model configuration can be seen in Fig. 4.

CNN-LSTM

CNN are a category of feedforward neural networks that incorporate convolutional operations, generally comprising convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers. CNN-LSTM is a deep learning architecture that integrates CNN and LSTM networks, frequently employed for the analysis of time-series data. This work employs a mixed technique of extracting features via the CNN layer. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the time series data is initially fed into the convolutional layer of the CNN for feature extraction. The collected feature sequences are subsequently input into the LSTM for further time-series modelling and forecasting66.

Bidirectional GRU (BiGRU)

The GRU neural network is an improved model of LSTM that decreases the number of gates while preserving long-term memory links to address the vanishing gradient problem. The BiGRU consists of two unidirectional GRUs functioning in opposing directions, hence creating an additional hidden layer. The key difference between BiGRU and GRU lies in the additional layer of hidden states67, as seen in Fig. 6.

CNN-GRU

CNN-GRU is a hybrid neural network model that integrates CNN and GRU, with a basic framework seen in Fig. 7. The data serves as the model input, and the convolution technique is employed to extract features and collect data correlations. The quantity of parameters is subsequently minimized by a pooling process to decrease the data dimension. Simultaneously, the dropout layer is incorporated to randomly choose neurons in the network based on a specified possibility to reduce overfitting68. The GRU layer is employed to analyze the decreased data and identify the temporal compliance rules among them69. The data are ultimately transformed into a one-dimensional sequence by the fully connected layer, resulting in the final results.

Multilayered perceptron (MLP)

MLP is one of the most widely used types of ANNs. The structure comprises three fully connected layers: the input layer, where model inputs are introduced; the output layer, which yields the results of the trained model; and the hidden layers, which serve as intermediate layers and may range from zero to multiple, as illustrated in Fig. 8 The relationships among them are founded on a weighted structure, with values adjusted throughout model training70,72.

Model evaluation

Different error measurement methodologies can evaluate the accuracy of models for prediction. The study proposes to evaluate the precision of models using five evaluation metrics: mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), coefficient of determination (R²), square error (MSE), normalized root mean square error (NRMSE). The five parameters are determined with Eqs. (14) to (18)73–76.

Input data

Case study

The geographical area of this case study is the Makran coast, in the southeastern part of Iran along the northern coast of the Gulf of Oman. This area stretches between latitudes 25° and 26.5° N and longitudes 57° to 61° E and is characterized by an arid to semi-arid climate with high temperatures, low annual rainfall, and limited natural freshwater resources. The Makran coast is of great geographical importance, particularly in light of its increasing population and expansion of industrial activities, both of which occasion an increasing need for sustainable and reliable water resources. The geographical and climatic conditions of the Makran coast make the region exceedingly well-suited for projects relating to renewable energy solutions. Due to its proximity to the Tropic of Cancer, the area receives high solar radiation and extended sunshine hours all year round, making it an ideal location for the deployment of solar energy systems. Figure 9 represents the location map of the Makran coast.

Location of the Makran coast in Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran, generated using base maps from Mapbox and OpenStreetMap (via Mapcarta, https://mapcarta.com/14666356, accessed 23 Jan. 2025), and edited with EdrawMax. Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, licensed under ODbL77.

Direct Normal Irradiation (DNI) is an essential parameter for establishing the feasibility of solar energy because it quantifies the solar radiation per square meter received on a surface normal to the solar beam. This measure is particularly significant to solar technologies such as parabolic solar collectors, whose effectiveness relies on direct sunlight for effective concentration and conversion of solar energy into heat energy. The Makran coastal DNI map highlights the huge solar energy potential of the region. Owing to dry climatic conditions, low cloud cover, and high sunlight duration, the Makran coast offers a suitable arrangement for the installation of parabolic solar collectors, which find extensive applications in thermal energy systems like heating, cooling, and other industrial processes. The DNI map for this area (Fig. 10) illustrates yearly solar irradiation averages in the form of a color-coded spectrum, extending from blue (lower) to pink (higher). The Makran coastline is predominantly orange to pink in color, designating DNI values from 2200 to 3700 kWh/m² annually. Such high values point towards the region’s appropriateness for parabolic solar collector systems that demand persistent and intense sunlight in order to be effective. Utilization of the high solar energy potential of the Makran coast provides excellent opportunities for the development of sustainable energy plans, facilitating the production of green thermal energy for local industries and communities while, simultaneously, decreasing the use of conventional fossil fuels. This is an indicator of the country’s potential to become a center for renewable energy plans in Iran.

Source: Global Solar Atlas (World Bank Group and Solargis, 2025), available at https://globalsolaratlas.info (accessed 23 Jan. 2025). Licensed under CC BY 4.078..

Long-term average of annual totals of DNI of the Makran coast in Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran.

Figure 11 displays the monthly average values of DNI for the Makran coast of Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran, and these give considerable insight into the region’s solar energy potential. DNI quantifies the solar radiation that falls on one square meter of a surface oriented perpendicular to the direction of the solar rays and thus is an important variable in the evaluation of solar energy projects, especially for such technologies as parabolic solar collectors. The results indicate high DNI values all year round with maximum values registered during January, March, April, October, and December, ranging from 175 to 185 kWh/m² monthly on average. These high values reveal an excellent availability of solar resources in winter and transitional months.

Conversely, minimum DNI values range from 100 to 120 kWh/m² during July and August, most likely due to atmospheric conditions such as increased humidity, haze, or cloud cover that reduce direct sunlight intensity during these months. The findings show the excellent solar energy potential of the Makran coast year-round, particularly during cooler months when solar energy systems can be more efficient due to reduced thermal loss. The high and stable values of DNI make the region an appropriate place for the setup of solar energy systems, like parabolic solar collectors, ideal for the generation of thermal energy for industrial and household applications. The results indicate the Makran coast as a prospective site for the feasibility of renewable energy projects, in agreement with the transition to the utilization of sustainable energy systems in Iran.

Monthly average of DNI of Makran coast in Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran78.

Figure 12 demonstrates the solar elevation and azimuth for the Makran coast in Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran, providing detailed information on the sun’s trajectory across the sky throughout the year.

The solar elevation and azimuth for the Makran coast in Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran78.

Solar elevation, represented on the vertical axis, is the altitude of the sun above the horizon, whereas solar azimuth, represented on the horizontal axis, defines the direction of the sun relative to true north (0° or 360°) and south (180°). The yellow color represents the active area of solar energy, which signifies the position of the sun throughout the various seasons. Significant solar paths are also included on the chart, highlighting seasonal movement. The red curve is the June solstice, where the sun reaches its highest elevation, producing the strongest and longest solar radiation. The blue curve is the December solstice, with lower solar elevation and shorter daylight hours. The black curve is the sun’s path during the equinox (spring and fall), when day and night are approximately equal. In addition, the terrain horizon, which is shown as the shaded black area at the bottom part, considers potential obstructions, such as hills or mountains that may block sunlight at lower altitudes. This analysis provides vital information for the optimal location and orientation of solar energy systems, such as parabolic solar collectors, in the Makran coastal region. The high solar elevation for most of the year underscores the area high solar energy potential. Orientation of solar collectors to receive optimum exposure during the peak solar hours can increase efficiency and facilitate the establishment of sustainable energy infrastructure in this high-irradiation coastal area.

Further, the Gulf of Oman provides a rich source of seawater, which can be effectively desalinated using the HDH process. This article discusses the key problem of freshwater shortage in the Makran region by incorporating a deep learning prediction model into the HDH approach. The predictive model offers an empirically derived approach crafted to improve resource management and facilitate the creation of sustainable water production systems uniquely adapted to surmount the specific difficulties that face arid coastal regions. Table 2 presents the geographical coordinates, solar radiation parameters, and climatic features of the Makran Coast.

In order to forecast the freshwater yield on the Makran coast of Iran, a deep learning approach is established based on both historical and real-time data gathered from a renewable energy-driven Humidification-Dehumidification (HDH) desalination plant. All the influencing environmental and operational parameters, such as solar irradiance, air and seawater temperature, humidity, flow rates, and thermal storage-related considerations, are embedded in the model. An LSTM neural network is implemented for this task since it is capable of handling sequential data and learning temporal relations. LSTM network is trained in such a manner that it links the provided input features to the desired output, which is the quantity of freshwater generated. A loss function like Mean Squared Error (MSE) is utilized during training to reduce mistakes in the predictions, while model performance is measured using metrics like Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and R-squared. After validation, the algorithm has shown the ability to accurately predict freshwater production under varying environmental and operational conditions. It can therefore be used as a reliable tool for system effectiveness evaluation and to assist in proactive decision-making during water scarcity.

Data Pre-processing and feature selection

The study examined if an increased data volume and multivariate observation enhance predictive performance or if a univariate data set is enough for generating an acceptable outcome. Consequently, the input data for the algorithms were multivariate, to improve awareness of this issue. This study used direct technique for predicting multistep ahead data, utilizing prior time steps as input variables and defining future time steps as target variables. Table 3 provides a description of the characteristics. The dataset is fully populated, with no missing values, however it requires preprocessing. The preprocessing part of this study encompasses feature engineering and data normalization.

To minimize computational expenses and enhance forecast accuracy, feature selection is performed to identify the most important features affecting the output value79. This study uses the Pearson matrix as the mechanism for feature selection. Figure 13 demonstrates the heatmap of the Pearson correlation matrix for global horizontal irradiation (GHI) in Makran coast. This coefficient is suitable for continuous time series input and target variables, quantifying correlations on a scale from − 1 to 1. The Pearson correlation coefficient is generally utilized to calculate the standard deviations between input and target variables, with the coefficient indicating the strength of the relationship. When a coefficient stands between 0 and 1, the target variable increases as the input variable rises. Conversely, when a coefficient ranges from 0 to −1, the target variable decreases as the input variable increases80. Figure 13 illustrates the significant correlation among wet bulb temperature at 2 m (T2MWET), Temperature at 2 m (T2M), Specific Humidity at 2 m (QV2M), surface temperature (TS), relative humidity at 2 m (RH2M), and surface pressure (PS), Dew Point Temperature at 2 m (T2MDEW), with GHI for Makran coast. Consequently, these attributes have been taken to be inputs for the multivariate.

Data normalization

Moreover, data may have disparities in scale and range, thus impacting the effectiveness of deep learning models. Normalization eliminates this issue by standardizing all numeric columns to a common scale, thus preventing any particular feature from unfairly impacting the model due to its range. This approach standardizes data obtained by rescaling it based on the maximum and minimum values. This standardizes the data ranges between 0 and 1, facilitating meaningful comparisons and clarity across various data types81. The dataset is divided into an 80 − 20 ratio for training and testing to prevent overfitting and underfitting. Figure 14 represents the methodology utilized in this study for forecasting solar radiation. This methodology comprises five main steps: (a) Meteorological data collection, (b) Data preprocessing, (c) Model training, (d) Model evaluation, and (e) Best model selection.

Results

Deep learning models

Table 4 defines the specifications of the hyperparameters for the suggested models. The model is supposed to forecast GHI as the primary output. It is important to consider that hyperparameters must be readjusted when the prediction priority varies. A higher volume of data and multivariate observations enhance predictive performance. Table 5 presents the result of the evaluation parameters for multivariate multistep ahead forecasting within the specified time horizon. The performance of different models for predicting GHI is presented. Across all metrics, the CNN-LSTM model demonstrated the highest accuracy, with the lowest RMSE (0.0021), MSE (0.0022), and MAE (0.0363) for testing. Its R² value of 0.9727 further indicates a strong correlation between the predicted and actual values. The MLP model, while slightly less accurate, demonstrated consistent performance across target features, achieving an R2 of 0.9707. The BiGRU and BiLSTM models also showed competitive performance, with LSTM slightly outperforming CNN-LSTM in terms of R2 and MAE. However, their performance was inferior to that of the standalone CNN-LSTM models, suggesting that simpler models can suffice for GHI prediction in this region for forecasting Makran coast over a 10-year horizon. To ensure clarity and reproducibility of the proposed hybrid forecasting framework, the full hybridization process is outlined in Appendix A, which provides a structured pseudo-code representation of the CNN-LSTM model. The algorithm begins with data preprocessing, including feature selection, aggregation, and normalization. Subsequently, the input–output pairs are generated through a sliding window approach, which enables the construction of supervised learning sequences. The core of the hybrid model is a CNN–LSTM architecture, where convolutional layers are employed to extract local temporal patterns, and stacked LSTM layers are used to capture long-term dependencies. Dense layers are then applied to map the learned representations to the forecast horizon. Finally, the model is trained and evaluated using multiple performance metrics.

The proposed hybrid CNN–LSTM model for time-series forecasting was designed with carefully tuned hyperparameters. A 12-step input window captures full seasonality, while a longer forecasting horizon tests both short- and long-term predictive ability. The CNN layer (kernel size 2, 64 filters) extracts local temporal features, and stacked LSTM layers (100 units each) capture long-term dependencies efficiently. A fully connected layer with ReLU activation enhances non-linear feature learning, while dropout was set to zero due to limited data but may be increased for larger datasets. The model is optimized with Adam for stable and fast convergence, using MSE loss to emphasize large errors. A small batch size improves generalization on small datasets, and 200 training epochs allow convergence without overfitting.

Figure 15 represents the value of the loss function in relation to epochs, as well as the MAE assessment throughout epochs. Clearly, an increase of epochs results in a reduction of the MAE value, indicating the completion of the learning process. A significant number of epochs (exceeding 200) increases the probability of overfitting, resulting in decreased model efficiency; conversely, fewer epochs provide poor learning outcomes.

Figures 16 and 17 illustrate the CNN-LSTM performance algorithms in predicting GHI in the Makran ocean over the next ten years, utilizing testing and training data. An alternative method to assess the algorithm performance is to establish a regression line correlating the actual and forecasted values. The distribution of points near the line y = x demonstrates a robust relationship between the predicted and actual data. Figures 18 and 19 illustrate the regression plots for the training and testing datasets. A substantial correlation exists between the actual and predicted data of GHI. The final simulation result, as shown in Fig. 20, demonstrates that the proposed CNN-LSTM model can reliably and effectively forecast solar radiation over the next ten years, which was the study goal.

Green building freshwater prediction

Figure 21 shows the performance of the CNN-LSTM model in forecasting freshwater production in the Makran Ocean over the coming decade. The figure sketches the rate of freshwater production per unit surface area (L/m²) between 1984 and 2033, comprising historical data through 2023 and projecting the 2024–2033 period as achieved through the application of the CNN-LSTM model. The GHI value was forecasted with the help of this model, and according to Eq. Seawater greenhouse system freshwater production capacity in green buildings can be predicted (13). The decade (2024–2033) average annual freshwater production is predicted as 1454.25 L/m². This combined approach enhances the predictive accuracy by taking solar radiation into consideration as a significant parameter affecting freshwater production efficiency. Parameters describing the quantities of freshwater yields per unit area are given in Table 6.

Following historical trends, freshwater production has displayed variability across the decades with an overall trend of rise from the 1990 s to around 2020. Inflection points representing significant growth stages are found in the late 1990 s and early 2000 s, reaching a peak around 2020, after which there is a downturn prior to stabilization being reached. The oscillations noted can be attributed to changes in climatic conditions, improvements in efficiencies of operations, or extraneous influences on the seawater greenhouse system. From the year 2024, the model foresees stabilization in freshwater production with minor fluctuations and a consistent increase to be witnessed up to 2033. The application of CNN-LSTM for GHI prediction is pivotal in this case since solar radiation is a significant driver of evaporation and condensation processes in seawater greenhouses. First, the system creates a model for GHI, then uses the results to improve forecasting of freshwater production. The method allows for more precise understanding of variations in water yield under different environmental conditions. This predictive model facilitates the creation of sustainable seawater greenhouse technology, especially for green building applications, by enhancing water resource efficiency over the solar energy potential. The anticipated stabilization and gradual rise in freshwater output indicate that, with continually advancing predictive modeling and system optimization, seawater greenhouses have much to contribute to water sustainability efforts in the future.

Discussion

The predictive modeling framework developed in this study, centered on a CNN–LSTM hybrid architecture, achieved superior accuracy in forecasting both GHI and corresponding freshwater yield for seawater greenhouse (SWGH) systems in the Makran region. The achieved R² of 0.9727 and RMSE of 0.0021 for GHI prediction surpass the performance metrics reported in most recent SWGH modeling efforts. Panahi et al.48 employed an ANN–ALO approach for predicting freshwater production in Oman and reported RMSE values exceeding those obtained in this study, while Wu et al.47 using RBFNN also exhibited lower accuracy compared to CNN–LSTM results. Similarly, Essa et al.46 integrated a Random Vector Functional Link with Artificial Ecosystem Optimization for predicting water productivity in Egypt, achieving reliable performance but without addressing long-term, multistep-ahead forecasts as implemented here.

Several prior works have explored deep learning architectures for agricultural or desalination applications, but with different objectives and environmental contexts. Huang et al.35 and Jiang et al.39 applied attention-based CNN–LSTM and LSTM models for microclimate forecasting in controlled agricultural systems, showing the benefit of temporal–spatial feature extraction. However, these models primarily targeted short-term predictions (hours to days) and did not explicitly link irradiance prediction to desalination output. The two-stage approach; first forecasting solar input and then using it to estimate freshwater yield extends the applicability of deep learning to long-term water production planning in arid coastal zones. From a technological integration perspective, previous studies have generally modeled SWGH systems in isolation from green building concepts. Al-Ismaili7,11 documented SWGH operational benefits but did not consider their synergy with building-scale resource management. In contrast, the present study explicitly evaluates SWGH freshwater yield within a green building framework, aligning with the food–energy–water nexus approach discussed by Valencia et al.58. This integration is crucial for improving overall system sustainability, as it allows co-optimization of building cooling loads, water supply, and agricultural production.

The forecasted average freshwater yield of 1454.25 L/m²/year for 2024–2033 compares favorably with production capacities reported in other high-solar-irradiance sites. Zarei et al.51 in Iran and Ehteram et al.49 in Oman demonstrated freshwater outputs of similar magnitude under optimal seasonal conditions but did not account for interannual variability. By leveraging CNN–LSTM, our approach captures both seasonal and decadal-scale fluctuations, offering a more robust planning tool for infrastructure investment. Importantly, while this study demonstrates high predictive performance, it also highlights the sensitivity of SWGH output to solar resource availability. This finding is consistent with the observations of Lawal et al.25, who showed that optimizing humidification–dehumidification parameters can significantly improve productivity under fluctuating weather conditions. The implication for policy and design is that predictive control systems potentially combined with hybrid renewable inputs such as wind or biomass27 could further enhance year-round stability82. By embedding AI-driven prediction into SWGH operation, this research addresses a gap in current literature noted by Ghiat et al.24 and Mahmood et al.26, who emphasize the need for adaptive, data-driven control under harsh climates. Results demonstrate that deep learning not only improves forecast accuracy but also provides actionable insights for operational planning, long-term water security, and integration into sustainable architecture.

Conclusion

This research proves the viability of the combination of deep learning methods and SWGH technology for enhancing freshwater generation for sustainable building utilization. Sophisticated machine learning methods were used to create a predictive model that can estimate freshwater yield as a function of both operational and environmental conditions with great reliability. Of the models compared, the CNN-LSTM showed the best prediction accuracy with R² of 0.9727, and the least RMSE (0.0021) and MSE (0.0022), thereby being the top performing model for the prediction of solar irradiance and freshwater production. This model was used to predict the value of GHI, and the freshwater production from the seawater greenhouse system in green buildings can be derived from freshwater production per unit area, which is very much reliant on the GHI value. The analysis of historical trends in freshwater production between 1984 and 2023 indicated variability because of climatic conditions and system efficiency. However, 2024–2033 forecasts predict stabilization with a gradual increase in freshwater yield at an approximate average annual value of 1454.25 L/m². The trend is indicative of the SWGH technology potential as a sustainable tool for water management in water-deficient regions, particularly when integrated into green building systems. From the CNN-LSTM model, the outcomes imply that with increased solar radiation, freshwater yield in SWGHs can be optimized, making this technology more reliable for sustainable water management. Beyond predictive accuracy, the findings underscore the broader implications for sustainable development:

-

Technical relevance: AI-enhanced SWGH systems can adapt to fluctuating climatic conditions, improving operational planning and reducing downtime.

-

Environmental sustainability: The reliance on solar-driven desalination minimizes fossil fuel use and greenhouse gas emissions while enabling brine management strategies to protect marine ecosystems.

-

Economic and social value: Stable freshwater production supports agricultural activities, reduces dependency on costly imported water, and strengthens the resilience of coastal communities.

The seawater greenhouse is a significant development in sustainable building systems by efficiently integrating desalination processes relying on renewable energy and ecological infrastructure. It employs the evaporation of seawater in regulating greenhouse temperatures, thereby creating favorable conditions for plant growth while simultaneously generating freshwater from the condensation process. One such example of advancement in this field is the use of solar-powered desalination using a thermal storage system that is integrated, thus making continuous operation possible even at times of low solar irradiance. Additionally, passive cooling systems facilitate optimal energy efficiency by reducing the reliance on conventional air conditioning systems within green building architecture designs. Maximum use of water and energy resources is achievable due to the closed-loop nature of such systems, hence making it a viable green solution to application in desert climates. Seawater greenhouses incorporated in green building architecture designs present an environmentally friendly solution to water-scarce regions. These systems harness renewable solar energy, thus reducing carbon emissions and providing potable water for irrigation, cooling, and other building purposes.

Future work should focus on expanding model inputs to incorporate socio-economic factors and seasonal agricultural demand data, enabling more comprehensive integration within food–energy–water nexus planning. In addition, research should investigate the use of hybrid renewable energy systems, such as solar–wind or solar–biomass combinations, to ensure continuous seawater greenhouse (SWGH) operation and enhance resilience against fluctuations in solar availability. Finally, efforts should be directed toward scaling the proposed approach for multi-site deployments, coupled with an assessment of policy frameworks that can facilitate the adoption of SWGH-integrated green building solutions in water-scarce regions. The synergy between advanced deep learning methods and SWGH technology offers a practical, scalable pathway to sustainable water management. Artificial intelligence application in solar water generation systems is a significant move towards water sustainability as well as promoting the development of green infrastructure in regions that lack water. When deployed strategically within green building systems, this integrated approach has the potential to significantly mitigate water scarcity challenges in arid coastal zones worldwide.

Appendix A: Pseudo code for CNN–LSTM model

Input:

Dataset D with features (GHI, T2M, …).

Input window size W.

Forecast horizon H.

Output:

Predicted values Y_pred for next H steps.

1: Load dataset D.

2: Remove irrelevant columns.

3: Aggregate data into monthly means.

4: Normalize features using MinMaxScaler.

5: Create windowed dataset (X, Y) with size W and horizon H.

6: Split data into training set (X_train, Y_train) and test set (X_test, Y_test).

7: Initialize Sequential model.

8: Add Conv1D layer with filters = 64, kernel size = 2, activation = ReLU.

9: Add MaxPooling1D with pool size = 2.

10: Flatten output.

11: Reshape output for LSTM input.

12: Add LSTM layer with 100 units, return_sequences = True.

13: Add another LSTM layer with 100 units.

14: Add Dense layer with 200 units, activation = ReLU, regularizer = L2.

15: Add Dropout layer (rate = 0.0).

16: Add Dense layer with (H × 2) units, activation = Linear.

17: Reshape output to (H, 2).

18: Compile model with optimizer = Adam, loss = MSE, metrics = MAE.

19: Train model on (X_train, Y_train) with validation on (X_test, Y_test).

20: Predict Y_pred = model(X_test).

21: Evaluate using metrics {R², RMSE, MSE, MAE, NRMSE}.

22: Return Y_pred.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \({\dot{\text{Q}}}\) :

-

Heat rate

- \({\dot{\text{m}}}\) :

-

Mass flow rate

- \(C_P\) :

-

EC Specific heat capacity

- \(T_{o,h}\) :

-

Hot water temperature

- \(T_{i,c}\) :

-

Cold water temperature

- \(A_{\text{collector}}\) :

-

Collector area

- h:

-

Enthalpy

- \(\omega\) :

-

Absolute humidity

- \(\eta\) :

-

Efficiency

- AARE:

-

Average absolute relative error

- AEO:

-

Artificial ecosystem-based optimization

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- ALO:

-

Antlion Optimization Algorithm

- ANFIS:

-

Adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system

- ANN:

-

Artificial Neural Network

- AWS:

-

Automatic weather stations

- BiGRU:

-

Bidirectional GRU

- BiLSTM:

-

Bidirectional LSTM

- BRR:

-

Bayesian ridge regression

- BT:

-

Boosted Tree

- CNN:

-

Convolutional neural networks

- CRM:

-

Coefficient of residual mass

- ConvLSTM:

-

Convolutional long short-term memory

- CYP:

-

Crop yield prediction

- DDMPC:

-

Data-driven robust model predictive control

- DIF:

-

Diffuse horizontal irradiation

- DL:

-

Deep learning

- DNI:

-

Direct normal irradiation

- DR:

-

Dimensionality reduction

- DT:

-

Decision Tree

- EANN:

-

Emotional Artificial Neural Network

- EC:

-

Efficiency coefficient

- FV:

-

Fractional variance

- GHI:

-

Global horizontal irradiation

- GRU:

-

Gated recurrent unit

- GTI−opta:

-

Global tilted irradiation at optimum angle

- IA:

-

Index of agreement

- KDE:

-

Kernel density estimation

- LDAPS:

-

Local data assimilation prediction systems

- LSVM:

-

Linear Support Vector Machine

- LSTM:

-

Long short-term memory networks

- MAE:

-

Mean absolute error

- MAPE:

-

Mean absolute predictive error

- MLP:

-

Multi-layer perceptron

- MLPNN:

-

Multi-Layer Perceptron Neural Network

- MLR:

-

Multiple linear regression

- MRE:

-

Mean relative error

- MSE:

-

Mean square error

- NF:

-

Neuro-Fuzzy

- NRMSE:

-

Normalized root mean square error

- NSE:

-

Nash Sutcliff efficiency

- OI:

-

Overall index

- PBIAS:

-

Percentage of bias

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- PE:

-

Mean predictive error

- \(R^2\) :

-

Coefficient of determination

- RF:

-

Random Forest

- RMSE:

-

Root mean square error

- RVFL:

-

Random vector functional link

- SST:

-

Sea surface temperature

- SVM:

-

Support Vector Machine

References

Taylor, R. J. K. Rethinking water scarcity: the role of storage. Eos Trans. AGU. 90, 237–238. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009EO280001 (2009).

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2, e1500323. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500323 (2016).

Greve, P. et al. Global assessment of water challenges under uncertainty in water scarcity projections. Nat. Sustain. 1, 486–494. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0134-9 (2018).

He, C. et al. Future global urban water scarcity and potential solutions. Nat. Commun. 12, 4667. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25026-3 (2021).

Belhassan, K. Water scarcity management. In: Water Safety, Security and Sustainability: Threat Detection and Mitigation 443–462 (Springer International Publishing, 2021).https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-76008-3_19.

Barzigar, A., Hosseinalipour, S. M. & Pani, A. An irreversible future: declining soil moisture, persistent droughts and emerging challenges for drying technology. Dry. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/07373937.2025.2543624 (2025).

Al-Ismaili, A. M. & Jayasuriya, H. Seawater greenhouse in Oman: A sustainable technique for freshwater conservation and production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 54, 653–664 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.016

Kummu, M. et al. The world’s road to water scarcity: shortage and stress in the 20th century and pathways towards sustainability. Sci. Rep. 6, 38495 (2016).https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38495

Molden, D. Scarcity of water or scarcity of management? Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 36, 258–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2019.1676204 (2020).

Sharma, A. et al. A comprehensive update on traditional agricultural knowledge of farmers in India. In: Wild Food Plants for Zero Hunger and Resilient Agriculture 331–386 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-6502-9_14

Bait-Suwailam, T. K. & Al-Ismaili, A. M. Review on seawater greenhouse: achievements and future development. Recent Pat. Eng. 13, 312–324 (2019).https://doi.org/10.2174/1872212113666181211151658

Pimentel, D. et al. Water resources: agricultural and environmental issues. BioScience 54, 909–918. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0909:WRAAEI]2.0.CO;2 (2004).

Pericherla, S., Karnena, M. K. & Vara, S. A review on impacts of agricultural runoff on freshwater resources. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. 11, 829–833 (2020).

Majeed, L. R. et al. Apple Academic Press,. Influence of Catchment on Freshwater Biodiversity. In: Biodiversity of Freshwater Ecosystems 93–104 (2022).

Mahmoudi, H. et al. Wind energy systems adapted to the seawater greenhouse desalination unit designed for arid coastal countries. Rev. Energ. Renouvelables. 10, 19–30 (2007).

Katakam, V. S. S. & Bahadur, V. Reverse osmosis-based water treatment for green hydrogen production. Desalination 581, 117588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2024.117588 (2024).

Al-Obaidi, M. A. et al. Integration of renewable energy systems in desalination. Processes 12, 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12040770 (2024).

ElSoudani, M. Cooling Techniques for Building-Greenhouse Interconnections in Hot-Arid Climates: The Case of Red Sea, Egypt. PhD thesis, Technische Universitaet Berlin (2016).

Ghaffour, N., Missimer, T. M. & Amy, G. L. Technical review and evaluation of the economics of water desalination: current and future challenges for better water supply sustainability. Desalination 309, 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2012.10.015 (2013).

Qiblawey, H. M. & Banat, F. Solar thermal desalination technologies. Desalination 220, 633–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2007.01.059 (2008).

Gevorkov, L., Domínguez-García, J. L. & Trilla, L. The Synergy of Renewable Energy and Desalination: An Overview of Current Practices and Future Directions. (2025).

Khawaji, A. D., Kutubkhanah, I. K. & Wie, J. Advances in seawater desalination technologies. Desalination 221, 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2007.01.067 (2008).

Sayed, E. T. et al. Application of artificial intelligence techniques for modeling, optimizing, and controlling desalination systems powered by renewable energy resources. J. Clean. Prod. 413, 137486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137486 (2023).

Ghiat, I., Govindan, R. & Al-Ansari, T. Data-driven predictive model for irrigation management in greenhouses under CO2 enrichment and high solar radiation. In: Computer Aided Chem. Engineering 52, 1585–1590 (Elsevier, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-15274-0.50252-3

Lawal, D. U. et al. Effective design of sustainable energy productivity based on the experimental investigation of the humidification-dehumidification-desalination system using hybrid optimization. Energy Convers. Manag. 319, 118942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118942 (2024).

Mahmood, F. et al. Energy utilization assessment of a semi-closed greenhouse using data-driven model predictive control. J. Clean. Prod. 324, 129172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129172 (2021).

Chen, W. & You, F. Semiclosed greenhouse climate control under uncertainty via machine learning and Data-Driven robust model predictive control. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 30, 1186–1197. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCST.2021.3094999 (2022).

Barzigar, A., Hosseinalipour, S. M. & Mujumdar, A. S. AI for enhanced solar dryer performance: integration of PV/T Panels, solar Collectors, energy Storage, Biomass, and desalination units. Dry. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/07373937.2025.2540730 (2025).

Chen, W. & You, F. Smart greenhouse control under harsh climate conditions based on data-driven robust model predictive control with principal component analysis and kernel density Estimation. J. Process. Control. 107, 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprocont.2021.10.004 (2021).

Al-Ismaili, A. M. et al. Empirical model for the condenser of the seawater greenhouse. Chem. Eng. Commun. 205, 1252–1260. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986445.2018.1443081 (2018).

Mahmood, F. et al. Data-driven robust model predictive control for greenhouse temperature control and energy utilisation assessment. Appl. Energy. 343, 121190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.121190 (2023).

Torres, J. F. et al. Deep learning for time series forecasting: a survey. Big Data. 9, 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1089/big.2020.0159 (2021).

Liu, G. et al. A state of Art review on time series forecasting with machine learning for environmental parameters in agricultural greenhouses. Inf. Process. Agric. 11, 143–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inpa.2022.10.005 (2024).

Fallah, M. et al. Comprehensive review of methodologies and case studies in advanced Exergy, Exergo-Economic, and Exergo-Environmental analyses. Energy 137606 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2025.137606 (2025).

Huang, S. et al. Edible mushroom greenhouse environment prediction model based on attention cnn-lstm. Agronomy 14, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14030473 (2024).

Subramaniam, L. K. & Marimuthu, R. Crop yield prediction using effective deep learning and dimensionality reduction approaches for Indian regional crops. e-Prime 8, 100611 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prime.2024.100611

Jun, J. & Kim, H. K. Informer-based temperature prediction using observed and numerical weather prediction data. Sensors 23, 7047. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23167047 (2023).

Ghasemlounia, R. et al. Developing a novel framework for forecasting groundwater level fluctuations using Bi-directional long Short-Term memory (BiLSTM) deep neural network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 191, 106568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106568 (2021).

Jiang, B. et al. Attention-LSTM architecture combined with bayesian hyperparameter optimization for indoor temperature prediction. Build. Environ. 224, 109536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109536 (2022).

Xiao, C. et al. A Spatiotemporal deep learning model for sea surface temperature field prediction using time-series satellite data. Environ. Model. Softw. 120, 104502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2019.104502 (2019).

Golabi, A. et al. Optimal operation of reverse osmosis desalination process with deep reinforcement learning methods. Appl. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-024-05452-8 (2024).

Reza, A. F. et al. An integral and multidimensional review on multi-layer perceptron as an emerging tool in the field of water treatment and desalination processes. Desalination 586, 117849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2024.117849 (2024).

Alghamdi, A. A novel IEF-DLNN and multi-objective based optimizing control strategy for seawater reverse osmosis desalination plant. Heliyon 9, e13814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13814 (2023).

Bueso, M. C. et al. Cooling tower modeling based on machine learning approaches: application to zero liquid discharge in desalination processes. Appl. Therm. Eng. 242, 122522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.122522 (2024).

Ashraf, W. M. et al. Machine learning assisted improved desalination pilot system design and experimentation for the circular economy. J. Water Process. Eng. 63, 105535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.105535 (2024).

Essa, F. A., Elaziz, M. A. & Elsheikh, A. H. Prediction of power consumption and water productivity of seawater greenhouse system using random vector functional link network integrated with artificial ecosystem-based optimization. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 144, 322–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2020.07.044 (2020).

Wu, Y., Xie, P. & Dahlak, A. Utilization of radial basis function neural network integrated with different optimization methods for the prediction of water productivity of seawater greenhouse system. Energy Rep. 7, 6658–6676 (2021).

Panahi, F. et al. Predicting freshwater production in seawater greenhouses using hybrid artificial neural network models. J. Clean. Prod. 329, 129721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129721 (2021).

Ehteram, M. et al. Predicting freshwater production and energy consumption in a seawater greenhouse based on ensemble frameworks using optimized multi-layer perceptron. Energy Rep. 7, 6308–6326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2021.09.079 (2021).

Liu, J. & Shao, M. The forecast of power consumption and freshwater generation in a solar-assisted seawater greenhouse system using a multi-layer perceptron neural network. Expert Syst. Appl. 213, 119289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119289 (2023).

Zarei, T. & Behyad, R. Predicting the water production of a solar seawater greenhouse desalination unit using multi-layer perceptron model. Sol Energy. 177, 595–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2018.11.059 (2019).

Faegh, M. et al. Development of artificial neural networks for performance prediction of a heat pump assisted humidification-dehumidification desalination system. Desalination 508, 115052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2021.115052 (2021).

Zarei, T., Behyad, R. & Abedini, E. Study on parameters effective on the performance of a humidification-dehumidification seawater greenhouse using support vector regression. Desalination 435, 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2017.05.033 (2018).

An, M. et al. Discovering a robust machine learning model for predicting the productivity of a solar-driven humidification-dehumidification system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 228, 120485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2023.120485 (2023).

Alhamami, A. H. et al. Solar desalination system for fresh water production performance Estimation in net-zero energy consumption building: A comparative study on various machine learning models. Water Sci. Technol. 89, 2149–2163. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2024.092 (2024).

Salem, H. et al. Predictive modelling for solar power-driven hybrid desalination system using artificial neural network regression with Adam optimization. Desalination 522, 115411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2021.115411 (2022).

Mohammed, A. et al. An optimization of hybrid renewable energy system for seawater desalination in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 22, 4463–4480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-024-05904-1 (2025).

Valencia, A. et al. Synergies of green Building retrofit strategies for improving sustainability and resilience via a Building-scale food-energy-water nexus. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 176, 105939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105939 (2022).

Xiang, Y. et al. Research on sustainability evaluation of green Building engineering based on artificial intelligence and energy consumption. Energy Rep. 8, 11378–11391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.08.266 (2022).

Barzigar, A., Hosseinalipour, S. M. & Mujumdar, A. S. Toward sustainable post-harvest practices: A critical review of solar and wind-assisted drying of agricultural produce with integrated thermal storage systems. Dry. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/07373937.2025.2542440 (2025).

Barzigar, A., Mujumdar, A. S. & Hosseinalipour, S. M. Review of seawater greenhouses: integrating sustainable agriculture into green Building. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 10, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41101-025-00406-8 (2025).

Hamdi, M. et al. Analysis and comparison of four recent laboratory-made integrated collector storage solar water heaters (ICSSWH) designs: parameters identification for long-term prediction. Appl. Therm. Eng. 125610 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2025.125610 (2025).

AbdelMeguid, H. Year-round performance evaluation of a solar-powered compact HDH desalination system for remote water scarce regions. Int. J. Green. Energy. https://doi.org/10.1080/15435075.2025.2454255 (2025).

Kwan, T. H. et al. Thermodynamic analysis of an energy-efficient thermal-desalination based on coupling absorption chiller, freeze and humidification-dehumidification. Desalination 118625 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2025.118625 (2025).

Ouyang, Z. et al. A novel integrated method for improving the forecasting accuracy of crude oil: ESMD-CFastICA-BiLSTM-Attention. Energy Econ. 138, 107851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2024.107851 (2024).

Shi, H. et al. A CNN-LSTM based deep learning model with high accuracy and robustness for carbon price forecasting: A case of shenzhen’s carbon market in China. J. Environ. Manage. 352, 120131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120131 (2024).

Qiao, Y. et al. A BiGRU joint optimized attention network for recognition of drilling conditions. Pet. Sci. 20, 3624–3637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petsci.2023.05.021 (2023).

Srivastava, N. et al. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 1929–1958 (2014).

Lynn, H. M., Pan, S. B. & Kim, P. A deep bidirectional GRU network model for biometric electrocardiogram classification based on recurrent neural networks. IEEE Access. 7, 145395–145405. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2939947 (2019).

Li, D. et al. Landslide susceptibility prediction using particle-swarm-optimized multilayer perceptron: comparisons with multilayer-perceptron-only, Bp neural network, and information value models. Appl. Sci. 9, 3664. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9183664 (2019).

Bahiraei, M. et al. Using neural network optimized by imperialist competition method and genetic algorithm to predict water productivity of a nanofluid-based solar still equipped with thermoelectric modules. Powder Technol. 366, 571–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2020.02.055 (2020).

Yusoff, N. I. M. et al. Engineering characteristics of nanosilica/polymer-modified bitumen and predicting their rheological properties using multilayer perceptron neural network model. Constr. Build. Mater. 204, 781–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.01.203 (2019).

Caldas, M. & Alonso-Suárez, R. Very short-term solar irradiance forecast using all-sky imaging and real-time irradiance measurements. Renew. Energy. 143, 1643–1658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.05.069 (2019).

Rumelhart, D. E., Hinton, G. E. & Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 323, 533–536. https://doi.org/10.1038/323533a0 (1986).

Uluocak, I. & Bilgili, M. Daily air temperature forecasting using LSTM-CNN and GRU-CNN models. Acta Geophys. 72, 2107–2126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11600-023-01241-y (2024).

Badal, M. K. I. & Saha, S. Performance analysis of deep neural network models for weather forecasting in bangladesh. In: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Trends in Computational and Cognitive Engineering: TCCE 2021 (Springer Nature Singapore, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7597-3_7

Mapbox & OpenStreetMap. Makran Coast, Sistan and Baluchestan, Iran. Mapcarta. Jan. (2025). https://mapcarta.com/14666356 (accessed 23.

World Bank Group and Solargis. Global Solar Atlas & World Bank Group. ( (2025). https://globalsolaratlas.info/map?c=25.273883,60.886917,10&s=25.252083,61.006306&m=site&pv=ground,180,29,1000 (accessed 23 Jan. 2025).

Moustafa, E. B., Hammad, A. H. & Elsheikh, A. H. A new optimized artificial neural network model to predict thermal efficiency and water yield of tubular solar still. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 30, 101750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2021.101750 (2022).

Chakraborty, D. et al. Computational solar energy–Ensemble learning methods for prediction of solar power generation based on meteorological parameters in Eastern India. Renew. Energy Focus. 44, 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ref.2023.01.006 (2023).

Ahmed, U. et al. Short-term global horizontal irradiance forecasting using weather classified categorical boosting. Appl. Soft Comput. 155, 111441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111441 (2024).

Pirkandi, J. et al. Parametric study and thermodynamic performance analysis of a hybrid solid oxide fuel cell-Stirling engine system for cogeneration applications. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 176, 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2023.05.062 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B. and S.A. developed the deep learning models, conducted data analysis, and prepared the manuscript draft. M.F. contributed to the system modeling and integration of SWGH into green building applications. A.S.M. and S.M.H. supervised the research, provided administrative support, and contributed to manuscript review and revisions. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

All participants provided informed consent to take part in the study.

Consent for publication

All participants consented to the publication of data and results arising from the research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions