Abstract

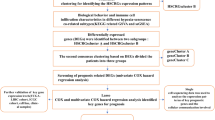

Growing evidence has revealed that N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) modification is crucial in cancer development, yet its role in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains unclear. To address this, we developed a novel m6A regulator-based prognostic signature (m6A-RPS) using comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of TCGA, GEO, and ICGC datasets. Our analysis revealed widespread dysregulation of m6A regulators in HCC tissues. Unsupervised consensus clustering further revealed distinct m6A methylation subtypes with significant survival differences, indicating the potential of m6A modification patterns in prognostic stratification for HCC. Using TCGA-LIHC cohort, LASSO Cox regression selected five key hub regulators (VIRMA, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDC1, IGF2BP3) to construct the m6A-RPS model. This model proved to be a powerful and independent prognostic indicator (HR = 2.849 (1.819–4.461), P < 0.001), and validated in external cohort (ICGC-LIRI-JP). Patients with high m6A-RPS scores exhibited significantly poorer overall survival and progression-free interval, and the scores were positively correlated with adverse clinical characteristics (e.g., advanced stage, vascular invasion). To facilitate clinical translation, we developed a nomogram that integrated the m6A-RPS with key clinical variables for individualized survival prediction. Genomically, the high-risk group exhibited higher tumor mutation burden and mutation rates in hub regulators. Functional enrichment analyses implicated dysregulation in critical pathways like Wnt signaling, DNA replication, and cell cycle. Crucially, m6A-RPS stratified the tumor immune microenvironment: high-risk patients displayed an immunosuppressive phenotype characterized by enriched Th2 cells and higher potential for immune escape, whereas low-risk patients showed enhanced cytotoxic immune infiltration and elevated immunophenoscores, suggesting greater potential responsiveness to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Differential sensitivity to chemotherapy agents was also predicted. Finally, we constructed a regulatory network linking miRNAs, hub regulators, and 2 downstream target genes. Our study establishes m6A-RPS as a robust tool for prognosis prediction and immune landscape assessment in HCC, offering significant potential to guide personalized therapeutic strategies, particularly immunotherapy selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents a significant global health challenge and is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality. The disease imposes a substantial economic burden on healthcare systems while severely compromising patients’ quality of life. Current therapeutic strategies for HCC, including surgical resection, liver transplantation, and systemic therapies, often yield unsatisfactory outcomes due to late-stage diagnosis and the tumor’s inherent resistance to conventional treatments1,2. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of HCC complicates treatment outcomes, as existing prognostic models fail to adequately account for the complex tumor microenvironment (TME) and molecular alterations3. Recent evidence highlights the potential of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification regulators as prognostic indicators across cancers, underscoring the need to comprehensively characterize their roles in HCC4.

m6A RNA modification represents the most prevalent epigenetic RNA alteration in eukaryotic cells. It regulates diverse biological pathways by influencing RNA transcription, processing, splicing, degradation, and translation. This dynamically reversible modification involves three regulatory factors: methyltransferases (“Writers”), demethylases (“Erasers”), and methylation recognition proteins (“Readers”), which collectively mediate m6A modification, demethylation, and functional recognition. Dysregulation of m6A modification is closely linked to tumorigenesis and cancer progression5. For example, METTL3 upregulation in gastric cancer stabilizes STAT5A mRNA via m6A modification, promoting tumor progression, metastasis, and poor prognosis6. METTL14 acts as a tumor suppressor in colorectal cancer by inhibiting glycolysis and cell proliferation through m6A-dependent regulation of ATF27. In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, ALKBH5 upregulation promotes immune escape by suppressing RIG-I-mediated IFNα secretion via the IKKε/TBK1/IRF3 pathway8. YTHDF2 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by enhancing immune evasion and angiogenesis through the ETV5/PD-L1/VEGFA axis, making it a potential therapeutic target9. It has also been reported that HNRNPC promotes glioma progression by stabilizing IRAK1 mRNA in an m6A-dependent manner and activating the MAPK signaling pathway10. Critically, m6A modifications influence multiple aspects of host immunity, modulate TME immune infiltration, and regulate tumor immunotherapy-related genes11,12. While these studies establish m6A correlations with diverse malignancies, their mechanistic roles in HCC remain inadequately elucidated. This knowledge gap highlights the need to explore m6A regulators as potential biomarkers for HCC patient stratification and therapeutic decision-making.

In this study, we employed comprehensive bioinformatics approaches to investigate m6A methylation regulators in HCC. We aimed is to establish a novel m6A regulators-based prognostic signature (m6A-RPS) model. This model provides insights into the prognostic significance of m6A regulators, their interactions with the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME), associations with oncogenic pathways, immune infiltration patterns, and treatment responses. We propose that m6A-RPS serves as a valuable tool for predicting HCC patient outcomes and guiding therapeutic strategies.

Materials and methods

Data collection

Gene expression profiles and corresponding clinical information were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds), and International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) database (https://dcc.icgc.org). For TCGA-LIHC and ICGC-LIRI-JP datasets, only patients with complete follow-up and survival information were included, retaining 365 and 240 patients, respectively.

All datasets underwent standardized preprocessing: microarray data were log2-transformed, and RNA-seq data were converted to log2 (TPM + 1). Expression matrixes for 21 m6A regulators, including writers (METTL3, METTL14, METTL16, RBM15, RBM15B, WTAP, VIRMA, and ZC3H13), erasers (FTO, ALKBH5, and ALKBH3), and readers (YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, YTHDC1, YTHDC2, IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3, HNRNPA2B1, and HNRNPC), were extracted from TCGA, GEO and ICGC based on previous publications.

The study used anonymized, published data requiring no ethics committee approval.

Expression, correlation, and interaction analysis

The differential mRNA expression of 21 m6A regulators between HCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues from TCGA-LIHC dataset (50 normal, 374 tumor) were assessed using Wilcoxon rank-sum test via R package “ggplot2”, “stats”, and “car”. Additionally, Spearman correlation analysis was performed to evaluate the relationships among these regulators. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks were constructed via STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/).

Survival analysis

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free interval (PFI) were evaluated using Kaplan-Meier curves, and statistical significance between groups was evaluated with the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to identify independent prognostic factors. Prior to multivariate modeling, missing values were addressed following univariate analysis. Hazard ratio (HR) along with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated to quantify the magnitude and precision of the associations.

Consensus clustering based on m6A regulators

Molecular subtypes were classified via unsupervised hierarchical clustering of TCGA-LIHC dataset using the R package “ConsensusClusterPlus”. The parameters were set as follows: maximum number of clusters = 6, 80% of total samples were resampled 500 times, clusterAlg = km, distance = euclidean, innerLinkage = complete. Clustering heatmaps were generated using the R package “pheatmap”. Principal component analysis (PCA), cumulative distribution function (CDF), and CDF delta area were used to determine the optimal number of clusters (k = 2 to 6). Finally, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to compare OS among the different molecular subtypes.

Construction and validation of prognostic signature

Univariate Cox regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the correlation of m6A regulators with OS in TCGA-LIHC dataset, and factors with P < 0.05 were subsequently included in the subsequent analysis.

Then, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression analysis was performed on TCGA-LIHC dataset via the R package “glmnet” for dimensionality reduction and identification of representative indicators. The optimal regularization coefficient λ was determined using 10-fold cross-validation, with partial likelihood deviance as the metric, and a fixed random seed was used to ensure reproducibility. Significant factors that incorporated into the model were referred to as hub m6A regulators. The expression patterns of these hub regulators were further validated in three independent GEO datasets: GSE55092 (91 normal, 49 tumor), GSE102079 (105 normal, 152 tumor), and GSE144269 (70 normal, 70 tumor).

A prognostic signature, termed m6A-RPS, was constructed using the formula: \(\:\text{m}6\text{A}-\text{R}\text{P}\text{S}\:\text{s}\text{c}\text{o}\text{r}\text{e}\:=\:{\sum\:}_{i}^{n}{Coef}_{i}*{\text{h}\text{u}\text{b}\:\text{m}6\text{A}\:\text{r}\text{e}\text{g}\text{u}\text{l}\text{a}\text{t}\text{o}\text{r}}_{i}\). This model was used to construct m6A-RPS to predict the prognosis of HCC patients. HCC patients were further divided into low- and high-risk groups according to the median value of m6A-RPS scores.

The predictive performance of m6A-RPS was evaluated by Kaplan-Meier curves and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Clinical utility was evaluated via decision curve analysis (DCA). Furthermore, the stability and reliability were validated using ICGC-LIRI-JP dataset.

Construction of prognostic nomogram

Independent prognostic factors were identified using multivariate Cox regression analysis, HR with corresponding 95% CI were calculated. Subsequently, a nomogram incorporating m6A-RPS and significant clinical parameters were developed to facilitate individualized survival prediction. The predictive performance of the nomogram was assessed in terms of discrimination and calibration. Discrimination was evaluated using Harrell’s c statistic (C-statistics), where a value of 0.5 indicates no discriminative ability beyond chance, whereas a value of 1.0 represents perfect discrimination. Calibration was visualized via calibration curves, which compare predicted probabilities with observed outcomes. To ensure robustness and mitigate overfitting, the calibration curves were generated using 800 bootstrap resamples with each drawing 100 samples. A nomogram with perfect calibration if the dots on the calibration curves would be close to the diagonal line.

Genomic alterations and functional enrichment analysis

Tumor Mutation Burden (TMB), which reflects the total number of somatic mutations in tumor cells, serves as a potential biomarker for predicting response to immunotherapy. To investigate the relationship between m6A-RPS and TMB, we analyzed somatic mutation data from TCGA-LIHC dataset. TMB was calculated using the R package “maftools”.

Genetic alteration data for hub m6A regulators were obtained from cBioPortal database (https://www.cbioportal.org/) based on the TCGA-LIHC dataset. The names of hub m6A regulators were entered into the query interface, and mutation profiles were extracted from the “OncoPrint” and “Cancer Types Summary” modules available in cBioPortal.

Additionally, we performed functional annotation of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between low- and high-risk groups using Metascape platform (https://metascape.org/), an online tool designed for high-throughput functional genomics analysis. DEGs were identified by comparing gene expression profiles between the two risk groups with the “limma” R package, using a threshold of adjusted P < 0.05 and |log2-fold change (logFC)| >2. The expression patterns of these DEGs were visualized in a heatmap generated with the “pheatmap” R package.

Gene set enrichment analysis

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was conducted using the R package “clusterProfiler” with the following parameter settings: nPerm = 10,000, minGSSize = 10, maxGSSize = 500, and p-value-Cutoff = 0.05. The DEGs identified between the low- and high-risk groups were used as the input for this analysis. GSEA evaluates whether a predefined gene set shows statistically significant and concordant differences between two biological states. The predefined gene sets were obtained from Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp). Specifically, the C2.Cp.v7.2.symbols.gmt was used as the reference gene set for KEGG and Reactome pathways, while the C5. All.v7.2.symbols.gmt collection served as the reference for Gene Ontology (GO) terms.

The analysis ranked all genes based on their correlation with the expression patterns of the DEGs. Enriched pathways were identified according to the normalized enrichment score (NES), adjusted P-value, and false discovery rate (FDR).

Immunological function analysis

We quantified the proportions of immune infiltrating cells in tumor samples using transcriptomic data from TCGA-LIHC dataset. The relative abundances of 24 immune cell types within TIME were assessed using single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) implemented in the gene set variation analysis (GSVA) R package. Additionally, the deconvolution algorithm CIBERSORT was applied to estimate the abundances of specific leukocyte subsets based on the HCC gene expression profiles. Differences in immune infiltration levels between the low- and high-risk groups were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Furthermore, we calculated Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients to examine associations between hub m6A regulators and various immune cells, including DC cells, B cells, T cells, cytotoxic cells, NK cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and related subtypes.

Single-cell RNA sequencing data in.h5 format, along with corresponding annotation files, were downloaded from Tumor Immune Single-Cell Hub (TISCH) database (https://tisch.comp-genomics.org/home/). We obtained 2 independent datasets of HCC (LIHC-GSE140228-Smartseq2 and LIHC-GSE98638-Smartseq2). Data processing and analysis were conducted using the MAESTRO and Seurat frameworks in R. Cell subpopulations were re-clustered utilizing the UMAP projection method.

Analysis of chemotherapy and immunotherapy efficacy

To evaluate the chemotherapeutic response in HCC patients, we predicted drug sensitivity (half-maximal inhibitory concentration, IC₅₀) using the R package “oncoPredict”, based on data from Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/).

The association between m6A-RPS and immune checkpoint genes was assessed using Spearman correlation analysis.

To investigate the relationship between m6A-RPS and the immunophenoscore (IPS), which reflects the tumor immune microenvironment and predicts response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), we retrieved IPS data from The Cancer Immunome Atlas (TCIA) database. Higher IPS values are indicative of a more favorable immune profile and potentially better response to immunotherapy.

Additionally, the Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) score (https://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) was calculated to estimate the likelihood of immune escape and immunotherapy response. Elevated TIDE scores suggest a higher potential for immune evasion and thus poorer response to ICIs.

Construction of miRNA-hub m6A regulators-m6A target gene regulatory network

To identify upstream miRNAs potentially associated with key m6A regulators, we acquired predicted miRNA–target interactions from the starBase database (https://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/), which incorporates multiple prediction algorithms including PITA, miRmap, microT, miRanda, PicTar, and TargetScan. Only miRNAs predicted by at least one of these tools were retained for subsequent analyses.

Furthermore, a multi-step bioinformatic approach was applied to identify potential m6A-related target genes. First, DEGs between HCC and normal tissues were identified from four independent datasets: TCGA-LIHC (50 normal, 374 tumor), ICGC-LIRI-JP (202 normal, 240 tumor), GSE14520 (220 normal, 225 tumor), and GSE76427 datasets (52 normal, 115 tumor). DEGs were selected using thresholds of adjusted P < 0.05 and |logFC| > 1, and visualized via volcano plots. Common DEGs across all datasets were then identified using Venn diagrams. These overlapping DEGs were further refined based on their correlation with hub m6A regulators, requiring a Spearman correlation coefficient of (|R| > 0.4 with P < 0.05). The resulting gene set was considered as candidate m6A target genes coregulated by key m6A regulators.

Based on these results, we constructed a comprehensive regulatory network for HCC depicting interactions between miRNAs and hub m6A regulators, as well as between hub m6A regulators and their potential m6A target genes, based on co-expression patterns.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.1 (Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was set at 0.05 for two-tailed tests. To control the FDR, adjusted P-values were calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure, with a significance threshold set at < 0.05. Normality of the data was evaluated with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Data visualization was performed using the ggplot2 package. Group comparisons of gene expression profiles and clinical characteristics were carried out using the Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate.

Results

Expression, correlation, and interaction of m6A regulators in HCC

Analysis of TCGA-LIHC data revealed significant differential expression of m6A regulators between HCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues. The majority of these regulators were significantly upregulated in HCC samples, except for ZC3H13 (Fig. 1A). Spearman correlation analysis indicated strong positive correlations among the m6A regulators, a finding further supported by a robust protein-protein interaction (PPI) network (Fig. 1B, C).

Consensus clustering based on m6A Regulators

Based on the expression profiles of 20 differentially expressed m6A regulators, the TCGA-LIHC cohort was categorized into distinct clusters using unsupervised consensus clustering. We evaluated cluster numbers (k) ranging from 2 to 6 and generated consensus cumulative distribution function (CDF) curves for each k value (Fig. 2A-C). The optimal number of clusters was determined to be k = 2, as it achieved the maximum inter-cluster discrimination with minimal overlap. Accordingly, the patients were stratified into Cluster 1 (n = 237) and Cluster 2 (n = 128). PCA demonstrated clear separation between the two clusters (Fig. 2D). Expression analysis revealed higher levels of m6A regulators in Cluster 2 compared to Cluster 1 (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis indicated that patients in Cluster 2 had significantly poorer OS (HR = 1.620 (1.143–2.297), P = 0.007, Fig. 2F). These results suggest that m6A methylation modification patterns have potential implications for molecular subtyping and prognostic assessment in HCC.

Consensus Clustering and survival analysis. (A) Consensus clustering matrix when k = 2. (B) Consensus CDF delta area curves. (C) Relative alterations in the area under CDF curve. (D) PCA plot. (E) Heatmap of correlations between 21 m6A regulators with clusters. (F) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis between different clusters

Screening of hub m6A regulators and prognostic signature construction

To further investigate m6A regulator-mediated methylation modification patterns in HCC, a novel m6A-RPS model was constructed using data from 365 TCGA-LIHC patients. First, univariate Cox regression analysis identified 11 m6A regulators significantly associated with OS (P < 0.05, Fig. 3A). Hub m6A regulators were then identified using LASSO Cox regression analysis. Five regulators, VIRMA, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDC1 and IGF2BP3, were included in the subsequent m6A-RPS model construction. The optimal regularization parameter λ (0.01411) was determined based on minimum partial likelihood deviance (Fig. 3B, C). The m6A-RPS score was calculated according to the following formula: (VIRMA * 0.129215664) + (YTHDF1 * 0.461841947) + (YTHDF2 * −0.232924755) + (YTHDC1 * 0.066869673) + (IGF2BP3 * 0.124743891). Patients were stratified into low- and high-risk groups based on the median m6A-RPS score. Baseline clinical characteristics for each group are summarized in Table 1. We found that m6A-RPS was significantly associated with OS (P<0.001), PFI (P<0.001), histologic grade (P<0.001), vascular invasion (P = 0.040), T stage (P<0.001), M stage (P = 0.008), pathologic stage (P < 0.001), and AFP level (P = 0.004). The expression levels of hub m6A regulators were validated in GSE55092, GSE102079, and GSE144269 datasets (all P < 0.05, Fig. 3D). Survival curves and ROC analyses for individual regulators are presented in Fig. S1.

Construction of a novel m6A regulators-based prognostic signature. (A) Forest map showing 11 prognostic m6A regulators identified using univariate Cox regression. (B, C) LASSO coefficient profiles and ten-fold cross-validation for tuning parameter selection. (D) Validation of expression levels of hub m6A regulators in GSE55092, GSE102079 and GSE144269 datasets. ns P ≥ 0.05; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001

Independent prognostic value of the m6A-RPS model

We evaluated the prognostic significance of m6A-RPS in patients with HCC. The distribution of risk scores, expression heatmap for the m6A-RPS model, and survival status of each patient are shown in Fig. 4A. Notably, hub m6A regulators were significantly up-regulated in the high-risk group. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed that patients in the high-risk group had significantly poorer OS (HR = 1.747 (1.232–2.476), P = 0.002) and PFI (HR = 1.723 (1.281–2.316), P < 0.001) compared to those in the low-risk group (Fig. 4B, C). The prognostic significance of m6A-RPS was consistently observed across various clinical subgroups, including patients with age ≥ 60 years, male, stage I and II, T1 and 2, N0, M0, histologic grade G1 and G2, with the high-risk group exhibiting significantly poorer survival in all these strata (all P < 0.05, Fig. 5A-H). Time-dependent ROC curve analysis demonstrated the predictive accuracy of m6A-RPS, with area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.741, 0.674, and 0.685 for 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS, respectively (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, the prognostic performance of m6A-RPS was validated in ICGC-LIRI-JP dataset (Fig. 4E-G, Table S1).

Prognostic value of m6A-RPS in HCC. (A, E) The analysis of m6A-RPS risk scores distribution in TCGA-LIHC and ICGC-LIRI-JP datasets. (B, F) OS curve of m6A-RPS in TCGA-LIHC and ICGC-LIRI-JP datasets. (C) PFI curve of m6A-RPS in TCGA-LIHC dataset. (D, G) Time-dependent ROC curve of m6A-RPS in TCGA-LIHC and ICGC-LIRI-JP datasets. (H) The expression analysis of m6A-RPS in patients with distinct patterns of recurrence in TCGA-LIHC dataset. ns P ≥ 0.05; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001

Association between the prognosis value of m6A-RPS and clinicopathologic characteristics. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that high expression of m6A-RPS was associated with poor OS in (A) ≥ 60 years old, (B) male, (C) asian, (D) histologic grade G1 and G2, (E) stage Ⅰ and Ⅱ, (F) stage T1 and T2, (G) stage N0, and (H) stage M0

Next, multivariate Cox regression analysis confirmed that m6A-RPS serves as an independent prognostic factor in HCC (HR = 2.849 (1.819–4.461), P < 0.001), along with TNM stage (Table 2). Based on these findings, we developed a nomogram integrating these variables to estimate 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS probabilities in HCC patients (C-index: 0.686 (0.659–0.712)). As shown in Fig. 6A, each selected variable in the nomogram is assigned a corresponding score based on its prognostic weight. The survival probability for an individual can be identified on the points scale after adding up the total scores. Calibration curves demonstrated good agreement between the model’s predicted probabilities and the observed outcomes, as the bias-corrected line closely followed the ideal diagonal across most of the probability range, indicating well-calibrated predictions (Fig. 6B). Moreover, the clinical usefulness of m6A-RPS model was evaluated using DCA by quantifying the net benefit at different threshold probabilities (Fig. 6C). As shown in the results, using the m6A-RPS model to identify high-risk individuals demonstrates a higher clinical net benefit when threshold probabilities range approximately between 0 and 0.5.

It is well known that the time interval between resection for HCC and recurrence has been reported to affect the survival time after surgery. Distinct patterns of recurrence complicate individualized pre-resection assessment of risk of recurrence. In this study, 31% of patients experienced recurrence within one year. Those with early recurrence (within one year) exhibited significantly higher m6A-RPS scores (P < 0.001, Fig. 4H), underscoring the potential utility of m6A-RPS as a biomarker for identifying high-risk individuals who might benefit from more aggressive treatment or surveillance strategies.

Taken together, all these results suggested that elevated m6A-RPS scores are consistently associated with unfavorable prognosis in HCC patients, and may serve as a valuable tool for risk stratification and treatment planning.

Genomic alterations and functional enrichment

To investigate the potential association between m6A-RPS and specific genomic features, we obtained tumor somatic mutation data from TCGA-LIHC dataset. Analysis revealed that the TMB-high group exhibited significantly higher m6A-RPS scores compared to the low-TMB group (P < 0.05, Fig. 7A).

We further characterized the molecular profiles of m6A-RPS subgroups by analyzing gene mutation patterns using cBioPortal database. As shown in Fig. 7B and C, the high-risk group showed a markedly higher mutation rate in hub m6A regulators. Specifically, among 183 HCC patients in the high-risk group, 45 (24.6%) carried mutations in these regulators, compared to only 26 of 182 patients (14.3%) in the low-risk group. The most frequently mutated regulators in the high-risk group were VIRMA (17%), YTHDF1 (4%), and IGF2BP3 (4%). Amplification was the predominant type of genetic alteration, followed by missense mutations.

To elucidate the biological pathways associated with the m6A-RPS subgroups, we identified DEGs between low- and high-risk groups. With |logFC| >2 and adjusted P < 0.05 set as the cut-off criteria, a total of 104 DEGs between the low- and high-risk groups were identified (80 of 104 genes were highly expressed and 24 genes were lowly expressed). The distribution of these DEGs was visualized via a volcano plot (Fig. 8A), and a heatmap demonstrated distinct expression patterns between the two risk groups (Fig. 8B). Functional enrichment analyses were performed to interpret the biological implications of these DEGs. GO analysis indicated that the biological processes were primarily associated with regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway, mitotic cell cycle, metanephros development, mRNA transport, protein autophosphorylation, etc. (Fig. 8C). For molecular function, the most enriched terms included cytoskeletal motor activity, protein serine kinase activity, etc. (Fig. 8D). Cellular component analysis highlighted enrichment in actin-based cel projection, cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase complex, etc. (Fig. 8E). KEGG pathway analysis further identified the Wnt signaling pathway and motor proteins as significantly enriched (Fig. 8F).

Enrichment analysis of DEGs between low- and high-risk groups. (A) The volcano plot of DEGs between low- and high-risk groups. (B) Heatmap of expression levels for DEGs between low- and high-risk groups. Functional enrichment analysis in (C) GO Biological Process, (D) GO Molecular Function, (E) GO Cellular Component, (F) KEGG

Molecular characteristics of different m6A-RPS subgroups

To further investigate the functional profiles and biological pathways associated with different m6A-RPS subgroups in HCC progression, GSEA was conducted between the low- and high-risk groups. Using the MSigDB Collection, we identified the most significantly enriched signaling pathways based on NES, with a FDR < 0.05 and adjusted P < 0.05 as significance thresholds.

The high-risk group exhibited significant enrichment in gene sets related to oncogenic processes, including the retinoblastoma gene in cancer, DNA replication and structural maintenance (e.g., DNA strand elongation), gastric cancer network 1, MCM (minichromosome maintenance) and Aurora B pathway involved in cell cycle regulation (Fig. 9A, C). Conversely, the low-risk group was primarily enriched in metabolic pathways, including the urea cycle, bile acid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, epoxygenase P450 pathway, oxidoreductase activity, and aromatase activity, etc. (Fig. 9B, D).

These findings suggest that m6A-RPS is closely associated with dysregulation of these functional pathways and may play a pivotal role in the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the high-risk subgroup. This study provides valuable insights and directions for further exploration of high-risk HCC characteristics and potential therapeutic targets.

Association of m6A-RPS with immune infiltration

The TIME plays a critical role in tumor progression and influences the prognosis of patients with HCC. To further investigate the potential role of m6A-RPS in TIME, we calculated infiltration score of 24 immune cell types in each HCC patient using the ssGSEA and CIBERSORT method. Significant differences in most infiltrating immune cell levels were revealed across the two subtypes. Specifically, the high-risk group exhibited higher infiltration of NK CD56bright cells, T helper cells, and Th2 cells, whereas the low-risk group showed greater association with B cells, CD8 + T cells, cytotoxic cells, DC cells, neutrophils, NK CD56dim cells, pDC cells, T cells, Th17 cells, and macrophages (all P < 0.05, Fig. 10A, B). These results indicate that m6A-RPS plays a key role in immune infiltration of HCC. Furthermore, Spearman correlation analysis was performed to evaluate the associations between the expression levels of hub m6A regulators and immune cell infiltration abundances (Fig. 10C, D).

Correlation between m6A-RPS and immune infiltration. The immune cell infiltration analysis based on the (A) ssGSEA and (B) CIBERSORT algorithm for hub m6A regulators. The immune cell infiltration analysis based on the (C) ssGSEA and (D) CIBERSORT algorithms in low- and high-risk groups. ns P ≥ 0.05; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001

We also explored the relationship between immune cell distribution and hub m6A regulator expression using single-cell RNA sequencing data. In the LIHC-GSE140228-Smartseq2 dataset, hub m6A regulators were highly expressed in B cells, CD4 + Tconv cells, CD8 + Tex cells, Tprolif cells, monocytes, and macrophages (Fig. 11A-C). A similar pattern of high expression in CD4 + Tconv cells, CD8 + Tex cells, Treg cells, and Tprolif cells was observed in the LIHC-GSE98638-Smartseq2 dataset (Fig. 11D-F).

Analysis of TIME in HCC with different levels of hub m6A regulators using scRNA-seq. The UMAP plots of single-cell clustering in the (A) LIHC-GSE140228-Smartseq2 and (D) LIHC-GSE98638-Smartseq2 datasets, where different colors represent different types of cells. The UMAP plots of the expression distribution of m6A regulators in different cells in the (B) LIHC-GSE140228-Smartseq2 and (E) LIHC-GSE98638-Smartseq2 datasets, where different colors represent expression abundance. The darker the color, the lower the expression of m6A regulators in the cell, and the brighter the color, the higher the expression of m6A regulators in the cell. The violin plots of the expression abundance of m6A regulators in different cells in the (C) LIHC-GSE140228-Smartseq2 and (F) LIHC-GSE98638-Smartseq2 datasets

Chemotherapy and immunotherapy efficacy analysis

While chemotherapy remains a cornerstone treatment for HCC, drug resistance frequently leads to therapeutic failure. To evaluate the relationship between m6A-RPS and chemosensitivity, we analyzed drug response data from GDSC database, focusing on the IC₅₀ values. Significant differences in estimated IC₅₀ were observed between the low- and high-risk groups stratified by m6A-RPS scores, providing a rationale for further investigation into personalized treatment strategies for HCC. Specifically, the high-risk group demonstrated increased sensitivity to 5-Fluorouracil, Lapatinib, and Cediranib, but reduced sensitivity to Cisplatin, Irinotecan, Gemcitabine, and Oxaliplatin (all P < 0.001). No significant difference in sensitivity to sorafenib was detected between the two groups (Fig. 12A).

Correlation of m6A-RPS with chemotherapy and immunotherapy efficacy. (A) Assessment of response to common chemotherapy drugs in patients with low- and high-m6A-RPS scores. (B) The heat map of the 10 immune checkpoints correlated to m6A-RPS. (C, D) TCIA and TIDE scores discrepancy between low- and high-risk groups. ns P ≥ 0.05; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001

Given the crucial role of immune checkpoint genes in regulating immune system activity and facilitating tumor immune evasion, we further examined the correlation between m6A-RPS and key immune-oncology targets in HCC. The m6A-RPS was positively correlated with the expression of several critical immune checkpoints, including programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1; PDCD1), programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1; CD274), cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), TIGIT, etc. (all P < 0.001, Fig. 12B), suggesting a greater potential for response to immunotherapy in the low-risk group. Using TCIA database, we also assessed the association between m6A-RPS and IPS. As shown in Fig. 12C, both IPS-CTLA4 and PD-1 scores were significantly higher in the low-risk group (all P < 0.05), indicating enhanced immunogenicity and a more favorable microenvironment for immune checkpoint inhibition in these patients. Additionally, TIDE scores, derived from the expression levels of immunotherapy biomarkers, were calculated to estimate the likelihood of immune escape and immunotherapy response. The results revealed a stronger immune escape capacity in the high-risk group, which correlated with a poorer response to immunotherapy (P < 0.001, Fig. 12D).

Collectively, these findings underscore the important role of hub m6A regulators in mediating immune escape within TIME and their influence on response to immunotherapy in HCC.

miRNA-hub m6A regulators-m6A target gene regulatory network

To investigate the role of hub m6A regulators and their biological functions in the tumorigenesis and progression of HCC, we constructed a comprehensive regulatory network involving miRNAs, hub m6A regulators, and m6A target genes.

DEGs from each dataset were visualized using volcano plots (Fig. S2), revealing 2,657 DEGs in TCGA-LIHC dataset, 916 in ICGC-LIRI-JP dataset, 960 in GSE14520 dataset, and 242 in GSE76427 dataset. Venn diagram analysis identified 48 overlapping DEGs (Fig. 13A). These overlapping DEGs were further refined based on Spearman correlation analysis with the five hub m6A regulators (VIRMA, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDC1, and IGF2BP3). Specifically, 5 VIRMA-related genes, 8 YTHDF1-related genes, 4 YTHDF2-related genes, 2 YTHDC1-related genes, and 5 IGF2BP3-related genes were analyzed for intersections, resulting in 2 genes coregulated by all five hub m6A regulators (Fig. 13B, Table S2).

Construction of miRNA-hub m6A regulator-m6A target gene regulatory network in HCC. (A) Intersection of the DEGs for TCGA-LIHC, ICGC-LIRI-JP, GSE14520, and GSE76427 datasets. Venn diagram analysis of (B) m6A target genes and (C) miRNAs associated with hub m6A regulators. (D) Cytoscape was used for construction of miRNAs-hub m6A regulators-m6A target genes regulatory network. Green, red and blue represent m6A target genes, hub m6A regulators and miRNAs, respectively

Putative upstream miRNAs targeting these five hub m6A regulators were predicted using the starBase database, incorporating multiple prediction tools including PITA, miRmap, microT, miRanda, PicTar, and TargetScan. Venn diagram analysis of the predicted miRNAs (Fig. 13C) identified seven candidate miRNAs with common binding sites across databases, and their correlation coefficients are summarized in Table S3.

Based on these results, a tripartite regulatory network comprising 7 miRNAs, 5 hub m6A regulators, and 2 m6A target genes was constructed and visualized using Cytoscape software (Fig. 13D).

Discussion

HCC, characterized by its high incidence and dismal prognosis, is a significant global health challenge. Its aggressive nature and resistance to conventional therapies are often linked to its development in the context of chronic liver diseases and a complex, heterogeneous molecular landscape13,14. Our study employed bioinformatics to systematically analyze the expression and prognostic significance of m6A RNA methylation regulators in HCC, leading to the development of a novel m6A-RPS model.

Our analysis revealed significant upregulation of most m6A regulators in HCC tumor tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues, aligning with their established roles in tumorigenesis across various cancers5. Spearman correlation and PPI network analyses underscored the interconnectedness and potential cooperative functions of these regulators in HCC progression, likely influencing key processes like proliferation, apoptosis, and metastasis15. Consensus clustering identified distinct HCC patient subgroups with differential survival outcomes, highlighting the biological complexity of HCC and the critical role of epitranscriptomic modifications16. This reinforces the need for patient stratification beyond traditional staging systems and positions m6A regulators as potential prognostic tools.

The prognostic significance of identified hub m6A regulators (VIRMA, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDC1, IGF2BP3) was leveraged to establish the m6A-RPS. This signature proved to be a robust predictor of OS and PFI. High m6A-RPS scores were significantly correlated with poorer prognosis and adverse clinical parameters, including higher histologic grade, vascular invasion, and advanced pathologic stage. Time-dependent ROC curve analyses confirmed its strong predictive accuracy over 1, 3, and 5 years. Furthermore, the integration of m6A-RPS into a nomogram along with traditional clinical variables improved the accuracy of survival prediction. The nomogram demonstrated good calibration, which was confirmed through bootstrapping validation, supporting its potential clinical utility. Notably, approaches such as Platt scaling or isotonic regression are also valid calibration techniques, and our bootstrap-based calibration curves similarly serve to evaluate probability calibration. This tool shows significant promise for informing personalized treatment strategies, which is particularly important given the high risk of relapse within the first year after resection17,18,19.

Analysis of the somatic mutation landscape from TCGA data revealed a significantly higher mutation rate in hub m6A regulators within the high-risk group (24.6%) compared to the low-risk group (14.3%), with amplification and missense mutations being predominant. This disparity underscores the potential contribution of m6A regulator alterations to HCC pathogenesis. Mutations in regulators like VIRMA, YTHDF1, and IGF2BP3 were notably prevalent in the high-risk group, potentially driving its aggressive phenotype. Gene set enrichment analysis further identified significant pathway enrichments in the high-risk group, including the Wnt signaling pathway (implicated in proliferation, differentiation, migration), the MCM pathway (critical for DNA replication and cell cycle progression), and the Aurora B pathway (key regulator of mitosis and chromosome segregation)20,21,22. Dysregulation of these pathways likely contributes to the aggressive biology observed in high-risk HCC and presents potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

The immune landscape plays a crucial role in HCC progression and patient prognosis. Our analysis revealed notable differences in immune infiltration between risk groups. The high-risk group exhibited increased levels of NK CD56bright cells, which demonstrate strong cytotoxic capabilities yet potentially signify a compensatory mechanism within an immunosuppressive TME23,24,25. This group also displayed a higher presence of T helper cells, especially Th2 cells. Th2 cells drive tumor progression by secreting cytokines that establish an immunosuppressive microenvironment. This Th2-skewed response can facilitate tumor growth and metastasis by suppressing anti-tumor immunity, consistent with established literature26,27. In contrast, the low-risk group demonstrated higher infiltration of cytotoxic immune cells such as CD8 T cells and macrophages, which are linked to improved patient outcomes due to their direct antitumor functions28,29. The association between m6A-RPS and immune infiltration further elucidates the interplay between epitranscriptomics and the immune microenvironment, which is crucial for developing future immunotherapeutic strategies in HCC.

The elevated expression of immune checkpoints in the context of m6A-RPS underscores the clinical significance of these findings, as they highlight a subgroup of HCC patients who may benefit more from immunotherapy. Our analysis reveals a positive correlation between m6A-RPS and key immune checkpoint markers, including PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4. Previous studies have confirmed the importance of these immune checkpoints in regulating T cell mediated antitumor activity, reinforcing their role as therapeutic targets30,31,32. Furthermore, the low-risk group demonstrated a higher IPS, suggesting greater tumor immunogenicity and potentially better response to immune checkpoint inhibitors33. Conversely, the high-risk group exhibited elevated TIDE scores, indicating a stronger immune escape potential and a TME more adept at evading immune detection34,35. These findings underscore the potential of m6A-RPS as a predictive tool to identify patients at risk of immune evasion, thereby supporting earlier and more targeted therapeutic intervention.

Although our study did not directly analyze pathways like antigen presentation, chemokine signaling, interferon response, or metabolic reprogramming, findings indirectly implicate their roles in forming the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment. Specifically, differential infiltration of DCs, pDCs, and CD8 T cells suggests potential alterations in antigen presentation and interferon-related immune regulation, while distinct immune cell distributions between subgroups may reflect chemokine-driven mechanisms. Additionally, enrichment of metabolic pathways (urea cycle, bile acid/fatty acid metabolism, P450 pathway, oxidoreductase activity) and differences in immunotherapy sensitivity highlight metabolic rewiring that may contribute to tumor progression and therapeutic response. The immunosuppressive microenvironment arises from complex multi-level, multi-system interactions. Metabolic reprogramming (e.g., enhanced glycolysis) drives this process by inhibiting interferon signaling (e.g., reduced STAT1 phosphorylation), inducing mitochondrial dysfunction (e.g., NDUFB10 overexpression), and causing defective antigen presentation (low MHC-I/II). It also synergistically activates the TGF-β/Wnt pathway, promoting M2 myeloid differentiation. Such metabolic-inflammatory crosstalk further disrupts chemokine axes (e.g., suppressed CXCL9/10) and accumulates lactate, inhibiting CD8⁺T cell recruitment and cytotoxicity to form an “immune desert.” This ultimately leads to T cell exhaustion and upregulated immune checkpoints. Targeting key nodes can reverse this suppressive state, providing a new strategy to overcome resistance to immunotherapy36,37,38. Recent studies indicate that m6A RNA modification plays a critical role in these processes. For instance, ALKBH5 can inhibit the RIG-I/IFNα signaling pathway, reducing IFNα secretion, which in turn leads to decreased recruitment of DCs, impaired antigen-presenting function, and insufficient T cell activation, ultimately promoting tumor immune evasion8. As a key m6A demethylase, FTO inhibits the expression of chemokine-related genes such as PTX3 through epigenetic mechanisms, reducing macrophage recruitment to TIME. Changes in its activity may also indirectly affect the expression of chemokines like CCL2/CCL5, promoting macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype and MDSC enrichment, collectively driving myeloid cell reprogramming39. Latest review studies have systematically demonstrated that m6A modifications shape the immunosuppressive microenvironment through four core mechanisms: driving enhanced glycolysis in metabolic reprogramming (e.g., FTO-mediated PGK1 upregulation and lactate accumulation); activating TGF-β signaling in inflammatory pathways (e.g., YTHDF2-dependent degradation of BAMBI relieves TGF-β inhibition); suppressing key pathways in interferon signaling (e.g., YTHDF1-mediated IFNGR1 mRNA degradation impairs IFN-γ responses); and upregulating inhibitory molecules in immune checkpoint expression (e.g., METTL3/ALKBH5 regulate PD-L1 through m6A-dependent translation or stability). These insights provide a rationale for combining m6A-targeting agents (e.g., METTL3 inhibitors like STM2457) with immune checkpoint blockade therapy40. In conclusion, the convergence of metabolic-epigenetic crosstalk, myeloid cell reprogramming, and immune exhaustion underpins the immunosuppressive microenvironment in high-risk group, explaining their poor prognosis and limited response to immunotherapy.

Association analysis between m6A-RPS and chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity revealed that the high-risk group demonstrated increased sensitivity to 5-Fluorouracil and Lapatinib, but reduced sensitivity to Cisplatin and Gemcitabine. This divergence suggests that m6A modifications may influence drug response through multiple mechanisms: potentially enhancing intracellular uptake or disrupting DNA repair pathways in the case of 5-Fluorouracil, and exploiting kinase dependency for Lapatinib41,42. Conversely, resistance to Cisplatin may stem from enhanced DNA repair mechanisms or elevated drug efflux, while insensitivity to Gemcitabine could involve alterations in nucleoside transporter expression or metabolic enzyme activity43,44. These findings underscore the potential of m6A-RPS as a predictive biomarker for drug response.

Furthermore, the construction of a regulatory network involving 7 miRNAs, 5 hub m6A regulators, and 2 m6A target genes elucidates intricate molecular interactions governing HCC progression. This network may crucially shape the immunological landscape and underlie resistance to conventional therapies45. Further studies are warranted to validate these findings and explore the clinical applicability of targeting this regulatory network in HCC management.

While this study provides significant insights into the role of m6A modifications in HCC, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the mechanistic investigations into how identified hub m6A regulators influence tumor biology remain largely correlative, necessitating further comprehensive bioinformatics analyses and experimental validation to establish causative relationships. Second, while we focused on m6A, our model may overlook synergistic effects with other epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA or histone modifications. These potential interactions could contribute to TME heterogeneity highlighted in our immune infiltration analyses. This narrow scope might limit the prognostic model’s comprehensiveness. Third, although validated in ICGC-LIRI-JP cohort, m6A-RPS requires broader external validation. This should expand validation to more representative populations and prospective clinical trials to verify its utility for guiding immunotherapy responses and chemotherapy selection. Addressing these gaps through in vitro and in vivo functional studies, combined with multi-omics integration, will be crucial for clinical translation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study elucidates the pivotal role of m6A modifications in the prognosis and treatment of HCC. The establishment of a prognostic model based on m6A regulators offers a promising avenue for personalized treatment strategies, particularly for high-risk patients. Further validation through independent cohorts and functional studies is warranted to strengthen the clinical applicability of our findings.

Data availability

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories including TCGA (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov), GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds), ICGC (https://dcc.icgc.org), STRING (https://cn.string-db.org/), cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/), Metascape (https://metascape.org/), MSigDB (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp), TISCH (https://tisch.comp-genomics.org/home/), GDSC (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/), TCIA (https://tcia.at/home), TIDE (https://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) and starBase (https://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/). The accession numbers can be found in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- HCC:

-

hepatocellular carcinoma

- m6A:

-

N6-Methyladenosine

- m6A-RPS:

-

m6A regulators-based prognostic signature

- TME:

-

tumor microenvironment

- TIME:

-

tumor immune microenvironment

- TCGA:

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- GEO:

-

Gene Expression Omnibus

- ICGC:

-

International Cancer Genome Consortium

- TPM:

-

transcripts per million

- PPI:

-

protein–protein interaction

- OS:

-

overall survival

- PFI:

-

progression-free interval

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- 95% CI:

-

95% confidence intervals

- PCA:

-

principal component analysis

- CDF:

-

cumulative distribution function

- LASSO:

-

least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic

- C-statistics:

-

Harrell’s c statistic

- DCA:

-

decision curve analysis

- TMB:

-

tumor mutation burden

- DEGs:

-

differentially expressed genes

- logFC:

-

log2-fold change

- GSEA:

-

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- MSigDB:

-

Molecular Signatures Database

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- NES:

-

normalized enrichment score

- FDR:

-

false discovery rate

- ssGSEA:

-

single-sample gene set enrichment analysis

- GSVA:

-

gene set variation analysis

- TISCH:

-

Tumor Immune Single-Cell Hub

- GDSC:

-

Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer

- IPS:

-

immunophenoscore

- ICIs:

-

immune checkpoint inhibitors

- TCIA:

-

The Cancer Immunome Atlas

- TIDE:

-

Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion

- AUC:

-

area under the curve

- MCM:

-

minichromosome maintenance

References

Brown, Z. J. et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: A review. JAMA Surg. 158, 410–420. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2022.7989 (2023).

Tabrizian, P., Abdelrahim, M. & Schwartz, M. Immunotherapy and transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 80, 822–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2024.01.011 (2024).

Safri, F., Nguyen, R., Zerehpooshnesfchi, S., George, J. & Qiao, L. Heterogeneity of hepatocellular carcinoma: from mechanisms to clinical implications. Cancer Gene Ther. 31, 1105–1112. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41417-024-00764-w (2024).

Uddin, M. B., Wang, Z. & Yang, C. The m(6)A RNA methylation regulates oncogenic signaling pathways driving cell malignant transformation and carcinogenesis. Mol. Cancer. 20, 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-021-01356-0 (2021).

Wang, T., Kong, S., Tao, M. & Ju, S. The potential role of RNA N6-methyladenosine in cancer progression. Mol. Cancer. 19, 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-020-01204-7 (2020).

Zang, Y. et al. METTL3-mediated N(6)-methyladenosine modification of STAT5A promotes gastric cancer progression by regulating KLF4. Oncogene 43, 2338–2354. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-024-03085-2 (2024).

Li, L., Zhang, R. & Li, Y. Up-regulation of m(6)A writer METTL14 inhibits tumorigenesis by suppressing Glycolysis in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 25, 305. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-025-13532-2 (2025).

Jin, S. et al. The m6A demethylase ALKBH5 promotes tumor progression by inhibiting RIG-I expression and interferon alpha production through the IKKε/TBK1/IRF3 pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Cancer. 21, 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-022-01572-2 (2022).

Wen, J. et al. YTHDF2 is a therapeutic target for HCC by suppressing immune evasion and angiogenesis through ETV5/PD-L1/VEGFA axis. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 11, e2307242. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202307242 (2024).

Chen, J. J. et al. The m6A reader HNRNPC promotes glioma progression by enhancing the stability of IRAK1 mRNA through the MAPK pathway. Cell. Death Dis. 15, 390. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-024-06736-0 (2024).

An, Y. & Duan, H. The role of m6A RNA methylation in cancer metabolism. Mol. Cancer. 21, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-022-01500-4 (2022).

Pan, J., Huang, T., Deng, Z. & Zou, C. Roles and therapeutic implications of m6A modification in cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 14, 1132601. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1132601 (2023).

Kalasekar, S. M., VanSant-Webb, C. H. & Evason, K. J. Intratumor heterogeneity in hepatocellular carcinoma: challenges and opportunities. Cancers (Basel). 13, 5524. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13215524 (2021).

Barcena-Varela, M. & Lujambio, A. The endless sources of hepatocellular carcinoma heterogeneity. Cancers (Basel). 13, 2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112621 (2021).

Jiang, X. et al. The role of m6A modification in the biological functions and diseases. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 74. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-00450-x (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Epigenetic modification of m(6)A regulator proteins in cancer. Mol. Cancer. 22, 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-023-01810-1 (2023).

Xing, H. et al. Repeat hepatectomy for patients with early and late recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter propensity score matching analysis. Surgery 169, 911–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2019.11.005 (2021).

Xu, X. F. et al. Risk Factors, Patterns, and outcomes of late recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter study from China. JAMA Surg. 154, 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4334 (2019).

Alawyia, B. & Constantinou, C. Hepatocellular carcinoma: a narrative review on current knowledge and future prospects. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 24, 711–724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-023-01098-9 (2023).

Wang, L. & Liu, X. Pan-Cancer Multi-Omics analysis of minichromosome maintenance proteins (MCMs) expression in human cancers. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed). 28, 230. https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbl2809230 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Targeting Aurora B kinase with Tanshinone IIA suppresses tumor growth and overcomes radioresistance. Cell. Death Dis. 12, 152. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-03434-z (2021).

Hayat, R., Manzoor, M. & Hussain, A. Wnt signaling pathway: A comprehensive review. Cell. Biol. Int. 46, 863–877. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbin.11797 (2022).

Bahadorian, D. et al. Regulatory NK cells in autoimmune disease. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 26, 609–616. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijbms.2023.68653.14969 (2023).

Tonetti, C. R. et al. Ovarian Cancer-Associated Ascites have high proportions of Cytokine-Responsive CD56bright NK cells. Cells. 10, 1702. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10071702 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Comprehensive analysis reveals PTK6 as a prognostic biomarker involved in the immunosuppressive microenvironment in breast cancer. J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 5160705. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5160705 (2022).

Morita, Y. et al. Functional Blockade of E-Selectin in Tumor-Associated vessels enhances Anti-Tumor effect of doxorubicin in breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 12, 725. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12030725 (2020).

Frafjord, A. et al. The immune landscape of human primary lung tumors is Th2 skewed. Front. Immunol. 12, 764596. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.764596 (2021).

Jacobs, C. et al. HSF1 inhibits antitumor immune activity in breast cancer by suppressing CCL5 to block CD8 + T-cell recruitment. Cancer Res. 84, 276–290. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-23-0902 (2024).

Pan, Y., Yu, Y., Wang, X. & Zhang, T. Tumor-Associated macrophages in tumor immunity. Front. Immunol. 11, 583084. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.583084 (2020).

Kreileder, M., Barrett, I., Bendtsen, C., Brennan, D. & Kolch, W. Signaling dynamics regulating crosstalks between T-Cell activation and immune checkpoints. Trends Cell. Biol. 31, 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2020.12.001 (2021).

Toor, S. M., Nair, S., Decock, V., Elkord, E. & J. & Immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment. Semin Cancer Biol. 65, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.06.021 (2020).

Rui, R., Zhou, L. & He, S. Cancer immunotherapies: advances and bottlenecks. Front. Immunol. 14, 1212476. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1212476 (2023).

Charoentong, P. et al. Pan-cancer Immunogenomic analyses reveal Genotype-Immunophenotype relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint Blockade. Cell. Rep. 18, 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.019 (2017).

Sellmer, L. et al. Markers of immune cell exhaustion as predictor of survival in Surgically-Treated Early-Stage NSCLC. Front. Immunol. 13, 858212. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.858212 (2022).

Bhandarkar, A. R., Bhandarkar, S., Babovic-Vuksanovic, D., Parney, I. F. & Spinner, R. J. Characterizing T-cell dysfunction and exclusion signatures in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors reveals susceptibilities to immunotherapy. J. Neurooncol. 164, 693–699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-023-04467-4 (2023).

Zhang, P. et al. Clinical prognostication and immunotherapy response prediction in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma using the DNA damage repair-associated signature. Environ. Toxicol. 39, 2803–2816. https://doi.org/10.1002/tox.24155 (2024).

Zhang, P. et al. Mitochondrial pathway signature (MitoPS) predicts immunotherapy response and reveals NDUFB10 as a key immune regulator in lung adenocarcinoma. J. Immunother Cancer. 13, e012069. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2025-012069 (2025).

Zhang, H. et al. Optimized dynamic network biomarker Deciphers a High-Resolution heterogeneity within thyroid cancer molecular subtypes. Med. Res. 1, 10-31. https://doi.org/10.1002/mdr2.70004 (2025).

Lu, J. et al. m6A regulator-based molecular classification and hub genes associated with immune infiltration characteristics and clinical outcomes in diffuse gliomas. BMC Med. Genomics. 18, 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-025-02104-9 (2025).

Shi, T., Zhang, H. & Chen, Y. The m6A revolution: transforming tumor immunity and enhancing immunotherapy outcomes. Cell. Biosci. 15, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-025-01368-z (2025).

He, M. et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: applicability in Western countries. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 70, 102362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2023.102362 (2023).

Sethy, C. & Kundu, C. N. 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) resistance and the new strategy to enhance the sensitivity against cancer: implication of DNA repair Inhibition. Biomed. Pharmacother. 137, 111285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111285 (2021).

Chen, S. H. & Chang, J. Y. New insights into mechanisms of cisplatin resistance: from tumor cell to microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20174136 (2019).

Nemati, M. et al. Gemcitabine: Immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive role in the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 16, 1536428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1536428 (2025).

Han, X., Guo, J. & Fan, Z. Interactions between m6A modification and MiRNAs in malignant tumors. Cell. Death Dis. 12, 598. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-03868-5 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Startup Fund for scientific research, Fujian Medical University (2019QH1186), Fujian provincial health technology project (2023QNA003), and Joint Funds for the innovation of science and Technology, Fujian province (2024Y9017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: HW, LL; data collection: HW, DNW; analysis and interpretation of results: HW, TJ, HWW; draft manuscript preparation: HW. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Review and/or approval by an ethics committee was not needed for this study because the study used anonymized, published data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Wang, D., Jiang, T. et al. Identification of a novel m6A RNA methylation regulator-based signature for prognosis and immune landscape prediction in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 36687 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20551-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20551-3