Abstract

Continuous kidney replacement therapy (CKRT) is an essential treatment for uncontrolled severe metabolic acidosis. However, CKRT can increase workload and lead to complications, thus necessitating its selective application to patients who stand to benefit significantly. This study aimed to investigate the therapeutic effect of CKRT in patients with severe acidosis by utilizing a deep learning-based causal inference model to assess the potential impact of CKRT on the risk of in-hospital mortality. The Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care III (MIMIC-III) database was utilized to select patients with available data collected within the first 48 h after intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Patients who experienced severe acidosis with a pH < 7.2 within the initial 48 h were selected. Treatment was defined as the application of CKRT within 48 h of ICU admission, and the outcome was defined as in-hospital mortality. The dataset was randomly divided at an 85:15 ratio for the training and test datasets. The Generative Adversarial Nets for Inference of Individualized Treatment Effects model was used to train the model, and the model performance was evaluated on the test dataset. In the training dataset, the model generated values of the accuracy and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve as 0.883 and 0.887 (0.880–0.893), respectively, while in the test dataset, it showed 0.841 and 0.824 (0.804–0.843), respectively. The average probability change in in-hospital mortality due to CKRT treatment was predicted to increase by 15% and 14% in the training and test datasets, respectively. However, in patients who received CKRT, the application of CKRT resulted in an average reduction in the mortality risk of 13% in both the training and test datasets. Developing a model that strategically represents the therapeutic effects of CKRT for individual patients could aid decision-making in patients with severe acidosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the field of critical care medicine, managing severe acidosis remains a pivotal challenge with significant implications for patient outcomes1,2,3,4. Severe acidosis can precipitate detrimental physiological effects across multiple organ systems and increase mortality risk5,6,7. Continuous kidney replacement therapy (CKRT) is recognized for its ability to manage acid–base imbalances and correct severe acidosis in critically ill patients. Current guidelines recommend CKRT in cases of uncorrected severe acidosis, a practice widely accepted among nephrologists8,9,10,11. However, research quantitatively measuring the extent to which CKRT improves survival outcomes for patients with severe acidosis, as well as how its effectiveness may vary across individual patients, is insufficient.

Causal inference analysis is a powerful statistical method for identifying causes of disease and treatment effects. With recent advances in deep learning, deep learning-based causal inference has produced significant results, especially in environments where conducting randomized controlled trials is challenging12,13. The purpose of this study was to quantitatively assess how CKRT affects the probability of in-hospital mortality in patients with severe acidosis following admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) by employing the Generative Adversarial Nets for inference of Individualized Treatment Effects (GANITE), a deep learning-based causal inference model14,15. Furthermore, this study aimed to utilize the GANITE model and statistical methods to identify the characteristics of patients who derive the greatest benefit from CKRT, thereby facilitating better patient selection.

Methods

Study population

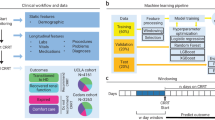

This study utilized the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care III (MIMIC-III) database, a comprehensive collection of deidentified health-related data from over forty thousand patients who stayed in the critical care units of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center between 2001 and 201216. As this study was an analysis of a public database, this study was exempt from approval by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Hospital (no. 2405-041-1535). We selected patients who had available vital sign records, urine output data, and laboratory data collected within 48 h of ICU admission and who survived this initial period. Patients who exhibited a pH less than 7.2 at least once within the first 48 h of their ICU stay were included. We excluded patients who died within 48 h of ICU admission from the analysis because these patients did not have sufficient time to receive CKRT for a meaningful evaluation of its therapeutic effects. These patients were then randomly split into training and test datasets at a ratio of 0.85:0.15.

Variables and outcomes for analysis

The treatment variable was defined as initiation of CKRT within 48 h of ICU admission, with the comparator being deferral beyond 48 h or no CKRT. Demographic data included sex and age, while vital sign data included systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), and body temperature. Blood laboratory data included albumin, anion gap, bicarbonate, total bilirubin, creatinine, hemoglobin, white blood cell and platelet counts, sodium, potassium, prothrombin time, and pH. Additional variables included hourly urine output and the fraction of inspired oxygen. The outcome was in-hospital mortality occurring after the initial 48-hour period following ICU admission.

Data generation

Time-series data were generated for all patients at one-hour intervals for a total of 48 h. The vital sign, urine output, and laboratory data were assigned to the nearest hour post-ICU admission up to 48 h, and any data not measured within an hour were imputed with the last available value. Variables not measured at all were imputed as zero. Time-series data were generated for each patient starting from the first occurrence of a pH < 7.2, and a four-hour time window was used for analysis. If the first occurrence of pH < 7.2 was within the first four hours after admission, missing data within this window were padded with zeros. For each patient, time-series data from the first occurrence of a pH < 7.2 through the subsequent 48 h were analyzed using a four-hour time window.

Development of the deep learning-based causal inference model

The GANITE, a deep learning-based causal inference model, was used14. Because the GANITE model is traditionally applied to one-dimensional tabular data, modifications were necessary to handle input data. The network section was altered from a simple deep neural network to long short-term memory to accommodate time-series data17. The vector representing the variables remained a one-dimensional vector as per the original model design. We adopted a causal inference deep learning approach because the decision to initiate CKRT in severe acidosis depends on high-dimensional, non-linear, and time-dependent relationships among early hemodynamics, acid–base status, renal function, and oxygenation. Compared with conventional regression or propensity-based methods that assume restrictive functional forms, the GANITE architecture—augmented with LSTM layers—can learn hourly trajectories and complex interactions, enabling individual-level treatment-effect estimation and explicit heterogeneity of treatment effect under a clinically actionable, timing-defined policy (initiation within 48 h vs. deferral/no use). Under standard identification assumptions (consistency, conditional exchangeability given observed early covariates, and positivity), this framework yields policy-relevant, model-based estimates intended to complement—not replace—clinical judgment. The model performance was evaluated on the training and test datasets by analyzing the actual in-hospital mortality probabilities and calculating the accuracy, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), and F1-score. The 95% confidence interval for the AUROC was determined using bootstrapping with 1000 iterations. Calibration performance was assessed through calibration plots. Additionally, the average treatment effect (ATE) of CKRT within 48 h of ICU admission and the conditional average treatment effect (CATE) for patients who underwent CKRT within this timeframe were examined. The treatment effect referred to the impact of a specified treatment (i.e., the administration of CKRT within 48 h of ICU admission) on an outcome, which was the probability of in-hospital mortality occurring after the initial 48 h. The ATE addresses a policy question: for each patient, the model estimates the counterfactual risk of in-hospital mortality if CKRT were initiated within 48 h and if not, conditional on observed first-48-hour covariates; the ATE is the average of these individual differences across the study population. The CATE for patients who underwent CKRT is the corresponding contrast restricted to patients who actually received CKRT, characterizing heterogeneity of predicted benefit within the treated subgroup. Additionally, we analyzed the CATE based on creatinine, urine output, MAP, potassium, and pH measured at the last time point to determine if there were statistically significant differences. These findings were then visualized using bar plots. Subsequently, total time-series data were categorized based on whether CKRT treatment decreased or increased mortality risk, and differences in variables between these groups were analyzed. Additionally, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify variables that may indicate a reduction in mortality risk when CKRT treatment was applied. A P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Study population and data generation

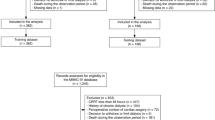

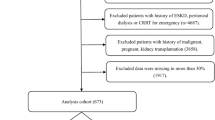

Among the patients who had available data collected within 48 h of ICU admission, 1,891 exhibited a pH lower than 7.2 at least once. These patients were randomly divided into training (n = 1,601) and test (n = 290) datasets (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Of the 1,891 patients with severe acidosis, 535 (28.3%) experienced in-hospital mortality after 48 h of ICU admission (Table 1). The average age of the patients was 61.2 ± 0.4 years, with those in the mortality group being older (64.3 ± 0.7 years) than those who survived (59.9 ± 0.5 years). Males accounted for 54% of the patients, with no difference in the proportion of males between patients who did and did not die. Serum creatinine levels were higher in the mortality group (2.36 ± 0.08 mg/dL) than in the no mortality group (1.76 ± 0.09 mg/dL). The hourly urine output at admission was lower in the mortality group, averaging 55.29 ± 3.60 ml/hr, than 122.68 ± 3.80 ml/hr in the no mortality group. Time-series data were generated for all patients at one-hour intervals for a total of 48 h. The training dataset yielded 15,679 windows for the four-hour time series, while the test dataset generated 2,921 windows.

Deep learning-based causal inference model

The GANITE model was developed, and its performance in predicting in-hospital mortality within 48 h after ICU admission showed AUROCs of 0.887 (0.880 to 0.893) and 0.824 (0.804 to 0.843), accuracies of 0.883 and 0.841, and F1-scores of 0.811 and 0.776 for the training and test datasets, respectively (Table 2; Fig. 2). Calibration plots indicated good calibration performance in both the training and test datasets (Fig. 2). The ATE of CKRT within 48 h after ICU admission was 14.9% (14.6 to 15.3%) in the entire dataset, meaning that, on average, the application of CKRT within this timeframe increased the probability of in-hospital mortality by 14.9% across all patients (Table 3). In contrast, the CATE for patients who underwent CKRT was − 13.1% (–14.4% to − 11.9%), indicating that for those who received CKRT, the probability of in-hospital mortality decreased by an average of 13.1%. Similar ATEs and CATEs were observed in both the training and test datasets.

Model performance and calibration. A, Plot of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve in the training dataset. B, calibration plot in the training dataset. C, Plot of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve in the test dataset. D, calibration plot in the test dataset.

CATE by various features

When examining the CATE for two groups divided based on specific cutoffs for only one variable, the application of CKRT was predicted to increase the probability of in-hospital mortality in all groups except for the group with a potassium level > 6 mmol/L (Fig. 3). However, when comparing the CATE for the groups simultaneously based on criteria of pH and other variables, the application of CKRT was predicted to reduce the probability of in-hospital mortality in patients with a high pH and other conditions, including levels of high creatinine, low hourly urine output, low MAP, and high potassium. Specifically, the group with a creatinine level < 3 mg/dL and a pH < 7 showed the most significant reduction in in-hospital mortality risk, with a CATE of − 20%.

Conditional average treatment effect according to patient conditions. A, Comparison of the effect according to the pH, creatinine, urine output, mean arterial pressure (MAP), and potassium levels. B, Comparison of the effect according to the combination of pH and other variables. Cr, creatinine; UO, urine output.

Logistic regression for decreasing mortality risk after CKRT application

When the data were divided into groups based on whether the treatment effect of CKRT was predicted to decrease the risk of in-hospital mortality (negative treatment effect) or not (positive treatment effect), all variables differed between the two groups in the entire dataset (Table 4). The group predicted to have a decrease in in-hospital mortality risk had higher pH values, higher creatinine levels, and lower hourly urine outputs than did the group predicted to have an increase in in-hospital mortality risk. Similar trends were observed in both the training and test datasets (Supplementary Table S2). A multivariable logistic regression analysis, using the predictions of decreased mortality risk by applying CKRT as the dependent variable, showed trends where an older age and a low BP were associated with a reduction in predicted mortality risk (Table 5). Furthermore, high levels of creatinine, pH, anion gap, bicarbonate, and potassium, as well as a low hourly urine output, were associated with a reduced probability of mortality after CKRT application.

Discussion

The present study leveraged real-time data from patients with severe acidosis, a critical challenge within the intensive care field, to predict mortality probabilities and assess the effect of CKRT on in-hospital mortality outcomes. The use of a deep learning-based causal inference model enabled not only the accurate forecasting of mortality risk but also the quantification of the therapeutic effects of CKRT. This innovative method facilitated a nuanced exploration of CKRT and its correlation with patient survival rates, thereby offering a comprehensive view that surpasses traditional predictive models. Furthermore, we used real-time clinical data and advanced causal inference techniques to aid clinicians in identifying high-risk ICU patients to receive timely interventions. This pioneering study could thus set a new benchmark for applying machine learning and deep learning in critical care settings, highlighting the model’s contribution to clinical decision-making in the face of severe acidosis challenges18.

Although numerous studies have underscored the importance of CKRT for patients with severe acidosis, few have directly examined the effect of CKRT on mortality under identical conditions through causal inference. Typically, randomization is deemed the most robust method for examining causal relationships; however, it leads to ethical and practical challenges in critical care, especially among severely ill patients19,20,21,22. The present study addressed these limitations by employing deep learning to simulate a variable-controlled environment, offering insights into the direct impact of CKRT on mortality. This method not only showcases the potential of deep learning in addressing the limitations of traditional methods but also underscores the significance of using advanced analytical techniques in critical care research.

The present model not only quantified the impact of CKRT on mortality with specific probability figures but also demonstrated good calibration performance, indicating how well the predicted probabilities aligned with the actual occurrence of outcomes. This performance, as indicated by the calibration curve, ensures that the predicted probabilities of the outcome are reliable. Furthermore, the model enabled the examination of individual patient responses to CKRT, moving beyond general trends and average effects. These detailed insights are invaluable for clinical decision-making, allowing health care providers to customize interventions based on the estimated benefits of CKRT for each patient23,24.

In this study, the analysis of the deep learning-based causal inference model indicated a model-predicted increase of 14.9% points in in-hospital mortality when CKRT was initiated within 48 h across the overall population. However, among patients who actually received CKRT, there was a model-predicted decrease of 13.1% points. CKRT-related complications—such as blood cell damage, nutritional loss, and vascular access problems—could contribute to worse outcomes when CKRT is applied without clear indications25; however, the observed contrast may also reflect non-selective early initiation extending treatment to patients unlikely to benefit, as well as residual and unmeasured confounding and limited overlap. These results suggest that if CKRT is not selectively applied for patients who need it, outcomes may worsen. Utilizing our model to determine the optimal patients and timing for the application of CKRT could improve outcomes in the management of severe acidosis26. This tailored approach aligns with the principles of precision medicine by emphasizing customized health care and facilitating individualized decisions on when to initiate CKRT based on existing evidence27,28,29. The present study exemplifies this approach, illustrating how advanced analytical tools and models can substantially contribute to precision medicine in critical care. However, these model-based, policy-level estimates should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating rather than definitive causal effects. Residual and unmeasured confounding and limited overlap may persist, and prospective, multicenter evaluation is warranted.

In contrast to previous research, the present study utilized 1-hour interval time-series data to capture rapid physiological changes in the ICU setting. These high-resolution data significantly enhanced the model performance by accounting for the dynamic and often volatile nature of patient status in the ICU setting. Furthermore, the use of such finely granulated data underscores the practicality of using the model in real clinical settings, enabling real-time application and thereby increasing its clinical relevance. This advancement not only boosts the potential for machine learning in critical care but also sets the stage for future innovations in patient monitoring and treatment optimization30,31.

Our study revealed that patients who benefited from a reduction in mortality risk due to the application of CKRT within 48 h of ICU admission were older than those who did not benefit as much, suggesting a greater efficacy of CKRT in reducing mortality risk among elderly patients. This finding may be attributed to the fact that elderly patients often have diminished physiological reserve and are less able to compensate for severe metabolic disturbances32. CKRT may provide a more controlled and gradual correction of acidosis, which could be particularly beneficial for older patients who might not tolerate rapid shifts in acid-base balance. Our findings also indicated that the implementation of CKRT in patients with high levels of creatinine and potassium, as well as low urine output and BP, is associated with a greater probability of mortality risk reduction. This outcome aligns with current guidelines on CKRT indications for deteriorating kidney function or hyperkalemia, confirming the appropriateness of these criteria for initiating CKRT9,27. In patients with low BP, the benefits of CKRT may be particularly significant due to the complex interplay between hypotension and acidosis. Hypotension can be both a consequence of severe acidosis and a contributing factor that exacerbates kidney injury, leading to worsening acidosis33,34. This creates a vicious cycle where acidosis and hypotension mutually worsen each other, increasing mortality risk35,36. Therefore, correcting acidosis through CKRT can break this cycle, potentially leading to greater mortality reduction in patients with low BP. Interestingly, a high pH increased the likelihood of reduction in mortality risk by CKRT, suggesting that initiating CKRT before the progression of severe acidosis might be highly effective for patient outcomes. Initiating CKRT at an earlier stage, when the patient is less acidotic, might prevent the cascade of worsening organ dysfunction associated with severe acidosis, thereby improving outcomes37. This insight may underscore the importance of early intervention with CKRT in patients with severe acidosis, potentially before acidosis reaches critical levels, which could optimize patient outcomes. Similarly, previous studies have shown that an early initiation of CKRT is associated with better outcomes26,38,39,40.

This study has certain limitations. The reliance on data from a single center and the exclusion of patients who experienced mortality within the initial 48-hour period after ICU admission may restrict the generalizability of the findings. These factors could introduce selection bias and limit the applicability of the results to broader patient populations. Adverse events were not adjudicated; therefore, causal attribution of mortality to CKRT-related complications is beyond the scope of this observational analysis. Additionally, our study focused on short-term outcomes, specifically in-hospital mortality, and did not account for long-term effects or recovery. While these long-term outcomes are crucial for a comprehensive assessment of CKRT’s impact, our ICU-specific dataset limited our ability to evaluate them. Although a causal inference method was employed, clinical trials with randomization are necessary to build upon these findings. To address these concerns, future studies should include data from multiple clinical settings, incorporate randomized controlled trials, and evaluate long-term outcomes. Moreover, not all clinically relevant covariates were captured or encoded, and the reported treatment effects are model-based predictions rather than directly observed contrasts. Accordingly, the estimates may be susceptible to residual and unmeasured confounding and model misspecification.

In conclusion, the present study makes a significant contribution to the existing body of knowledge on the effectiveness of CKRT in severe acidosis scenarios by leveraging the potential of the deep learning-based causal inference model. These findings underscore the importance of utilizing advanced analytical tools to guide clinical decisions, with the ultimate goal of enhancing patient care and outcomes in the ICU.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in the present study are publicly available and can be accessed through the MIMIC-III database from PhysioNet.

References

Allyn, J. et al. Prognosis of patients presenting extreme acidosis (pH < 7) on admission to intensive care unit. J Crit. Care Feb. 31 (1), 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.09.025 (2016).

Henrique, L. R., Souza, M. B., El Kadri, R. M., Boniatti, M. M. & Rech, T. H. Prognosis of critically ill patients with extreme acidosis: A retrospective study. J. Crit. Care. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2023.154381 (2023). /12/01/ 2023;78:154381.

Jamme, M. et al. Severe metabolic acidosis after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: risk factors and association with outcome. Ann. Intensiv. Care. 2018/05/08 (1), 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-018-0409-3 (2018).

Yagi, K. & Fujii, T. Management of acute metabolic acidosis in the ICU: sodium bicarbonate and renal replacement therapy. Critical Care 25(1), 314. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03677-4 (2021).

Mitchell, J. H., Wildenthal, K. & Johnson, R. L. Jr. The effects of acid-base disturbances on cardiovascular and pulmonary function. Kidney Int May. 1 (5), 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1972.48 (1972).

Orchard, C. H. & Kentish, J. C. Effects of changes of pH on the contractile function of cardiac muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 258(6 Pt 1), C967–C981. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.6.C967 (1990).

Urso, C., Brucculeri, S. & Caimi, G. Acid–base and electrolyte abnormalities in heart failure: pathophysiology and implications. Heart Failure Reviews 20(4), 493–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-015-9482-y (2015).

Cerdá, J., Tolwani, A. J. & Warnock, D. G. Critical care nephrology: management of acid-base disorders with CRRT. Kidney Int Jul. 82 (1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2011.243 (2012).

Khwaja, A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin. Pract. 120 (4), c179–c184. https://doi.org/10.1159/000339789 (2012).

Yagi, K. & Fujii, T. Management of acute metabolic acidosis in the ICU: sodium bicarbonate and renal replacement therapy. Crit Care Aug. 31 (1), 314. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03677-4 (2021).

Subramaniyan, V., Shaik, S., Bag, A., Manavalan, G. & Chandiran, S. Potential action of Rumex vesicarius (L.) against potassium dichromate and gentamicin induced nephrotoxicity in experimental rats. Pak J. Pharm. Sci. 31(2), 509–516 (2018).

Belthangady, C. et al. Causal deep learning reveals the comparative effectiveness of antihyperglycemic treatments in poorly controlled diabetes. Nature Communications 13(1), 6921. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33732-9 (2022).

Lagemann, K., Lagemann, C., Taschler, B. & Mukherjee, S. Deep learning of causal structures in high dimensions under data limitations. Nat. Mach. Intell. 11 (11), 1306–1316. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-023-00744-z (2023). /01 2023.

Yoon, J., Jordon, J. & Schaar Mvd, GANITE. Estimation of Individualized Treatment Effects using Generative Adversarial Nets. (2018).

Huqh, M. Z. U. et al. Clinical Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Children with Cleft Lip and Palate-A Systematic Review. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health Aug 19(17), https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710860 (2022).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database. Sci. Data. 05 (1), 160035. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.35 (2016). /24 2016.

Hochreiter, S. S. Jürgen. Long Short-Term memory. Neural Comput. 9 (8), 1735–1780. https://doi.org/10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735 (1997).

Thapa, R. et al. Unveiling the connection: Long-chain non-coding RNAs and critical signaling pathways in breast cancer. Pathol Res. Pract Sep. 249, 154736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2023.154736 (2023).

Colli, A., Pagliaro, L. & Duca, P. The ethical problem of randomization. Intern Emerg. Med Oct. 9 (7), 799–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-014-1118-z (2014).

Goldstein, C. E. et al. Ethical issues in pragmatic randomized controlled trials: a review of the recent literature identifies gaps in ethical argumentation. BMC Med. Ethics. 2018/02/27 (1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0253-x (2018).

Kumarasamy, V., Anbazhagan, D., Subramaniyan, V. & Vellasamy, S. Blastocystis sp., parasite associated with Gastrointestinal disorders: an overview of its Pathogenesis, immune modulation and therapeutic strategies. Curr. Pharm. Des. 24 (27), 3172–3175. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612824666180807101536 (2018).

Fuloria, S. et al. Synbiotic effects of fermented rice on human health and wellness: A natural beverage that boosts immunity. Front. Microbiol. 13, 950913. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.950913 (2022).

Subramaniyan, V. et al. Alcohol-associated liver disease: A review on its pathophysiology, diagnosis and drug therapy. Toxicol. Rep. 8, 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2021.02.010 (2021).

Bhat, A. A. et al. Curcumin-based nanoformulations as an emerging therapeutic strategy for inflammatory lung diseases. Future Med. Chem Apr. 15 (7), 583–586. https://doi.org/10.4155/fmc-2023-0048 (2023).

Gautam, S. C., Lim, J. & Jaar, B. G. Complications associated with continuous RRT. Kidney360 Nov. 24 (11), 1980–1990. https://doi.org/10.34067/kid.0000792022 (2022).

Gist, K. M. et al. Time to continuous renal replacement therapy initiation and 90-Day major adverse kidney events in children and young adults. JAMA Netw. Open. 7 (1), e2349871–e2349871. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.49871 (2024).

Macedo, E. & Mehta, R. L. Continuous Dialysis therapies: core curriculum 2016. Am J. Kidney Dis Oct. 68 (4), 645–657. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.03.427 (2016).

Ostermann, M. & Chang, R. W. Correlation between parameters at initiation of renal replacement therapy and outcome in patients with acute kidney injury. Crit. Care. 13 (6), R175. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc8154 (2009).

Global burden and strength of evidence for. 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet May. 18 (10440), 2162–2203. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00933-4 (2024).

Gupta, G. et al. Hope on the horizon: Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells in the fight against COVID-19. Regen Med. 18(9), 675–678. https://doi.org/10.2217/rme-2023-0077 (2023).

Sahoo, A. et al. Potential of Marine Terpenoids against SARS-CoV-2: An In Silico Drug Development Approach. Biomedicines Oct. 20(11), https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9111505 (2021).

Ferrucci, L. et al. Biomarkers of frailty in older persons. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 25 (10 Suppl), 10–15 (2002).

Kraut, J. A. & Madias, N. E. Metabolic acidosis: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Nature Reviews Nephrology May. 6 (5), 274–285. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2010.33 (2010).

Vincent, J. L. & Castanares Zapatero, D. The role of hypotension in the development of acute renal failure. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association 24(2), 337–338. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfn679 (2009).

Libório, A. B., Leite, T. T., Neves, F. M., Teles, F. & Bezerra, C. T. AKI complications in critically ill patients: association with mortality rates and RRT. Clinical J. Am. Soc. Nephrology: CJASN Jan. 7 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.04750514 (2015).

Noritomi, D. T. et al. Metabolic acidosis in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: a longitudinal quantitative study. Crit Care Med Oct. 37 (10), 2733–2739. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0b013e3181a59165 (2009).

Al-Jaghbeer, M. & Kellum, J. A. Acid-base disturbances in intensive care patients: etiology, pathophysiology and treatment. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 30(7):1104-11. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfu289 (2015).

Park, J. Y. et al. Early initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy improves survival of elderly patients with acute kidney injury: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Crit Care Aug. 16 (1), 260. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1437-8 (2016).

Chinnasamy, V. et al. Antiarthritic activity of achyranthes aspera on Formaldehyde - Induced arthritis in rats. Open Access. Maced J. Med. Sci Sep. 15 (17), 2709–2714. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2019.559 (2019).

Bhat, A. A. et al. MALAT1: A key regulator in lung cancer pathogenesis and therapeutic targeting. Pathol Res. Pract Jan. 253, 154991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2023.154991 (2024).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health research project (no. 2023-ER1105-00) and a cooperative research fund of the Korean Society of Nephrology (2023 year).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MWK and SSH designed the study. MWK collected, generated, and analyzed the data. MWK, SP, YCK, KHO, KWJ, YSK, DKK, and SSH interpreted the data. MWK and SSH wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

As this study was an analysis of a public database, this study was exempt from approval by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Hospital (no. 2405-041-1535).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, M.W., Park, S., Kim, Y.C. et al. Exploring the therapeutic effects of continuous kidney replacement therapy in patients with severe acidosis using deep learning-based causal inference. Sci Rep 15, 36566 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20555-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20555-z