Abstract

This study introduces a novel group decision-making framework based on the Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST) model to effectively address complex multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) problems under uncertainty and imprecise expert judgments. The proposed FST structure integrates the strengths of fuzzy set theory and soft set theory within a multidimensional tensorial framework, offering a powerful and flexible approach to modeling expert knowledge across alternatives, criteria, and decision-makers. A new aggregation-driven group decision-making algorithm is developed to systematically combine diverse expert evaluations and ensure consistent ranking of alternatives. To demonstrate the applicability and robustness of the proposed FST-based framework, a real-world case study on heterogeneous wireless network selection is presented. Six competing technologies are evaluated against six critical performance criteria. The experimental results indicate that the FST-based approach identifies 5G NR as the most suitable network alternative, showing strong agreement with established MCDM methods such as TOPSIS, GRA, MOORA, and WASPAS. Comparative analysis further highlights that the FST model improves the handling of vague, inconsistent, and multi-perspective data while maintaining computational efficiency and interpretability. These findings confirm the scalability and reliability of the FST framework as an effective decision-support tool for complex and dynamic environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In real-world decision-making environments, uncertainty and vagueness frequently arise due to incomplete, imprecise, or subjective expert assessments. Traditional fuzzy models often struggle to fully capture the hesitation and ambiguity inherent in human judgments. Although advanced fuzzy extensions have addressed certain limitations, they frequently fall short when handling high-dimensional data or when multiple evaluators express preferences across complex criteria sets.

To overcome these challenges, this study introduces the concept of the Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST)—a novel framework that integrates soft set theory and fuzzy logic within a tensor-based structure. The FST model enables simultaneous representation of uncertain information across multiple alternatives, criteria, and decision-makers. Unlike earlier low-dimensional hesitant or interval-based models, FST provides a flexible, scalable, and semantically rich means of capturing and processing expert knowledge in group decision-making contexts.

Beyond formalizing the FST structure, this work also defines key operations, derives fundamental algebraic properties, and proves relevant theorems to establish its mathematical soundness. Furthermore, a new aggregation-based group decision-making algorithm is proposed, specifically designed to exploit the multidimensional and soft characteristics of the FST framework.

To validate the practical utility of the proposed approach, we apply it to a real-world case study involving the evaluation of heterogeneous wireless network technologies. The case study illustrates the model’s ability to handle multiple expert opinions and complex criteria under uncertainty, producing robust and interpretable results aligned with real-world requirements.

In modern data analysis, the need to effectively process uncertain, incomplete, and multidimensional information has led to the development of advanced mathematical frameworks. Fuzzy Set (FS) theory, introduced by Zadeh in 19651, provides a foundation for handling partial truths using membership degrees ranging between 0 and 1. Since its inception, FS theory has significantly influenced domains where information is inherently imprecise.

Building on FS theory, various enhancements have emerged. Cut set theory plays a central role in analyzing fuzzy matrices (FMs), with Fan and Liu2,3 developing decomposition theorems that expand FM applicability. Anti-fuzzy theory4,5 introduces an algebraic dual for modeling uncertainty. To extend fuzzy modeling into higher dimensions, Chen and Lu6,7 proposed fuzzy tensors (FT) and intuitionistic fuzzy tensors (IFT), enabling the representation and manipulation of complex structured datasets through tensor algebra.

Another important extension is the Intuitionistic Fuzzy Set (IFS), introduced by Atanassov in 19868, which incorporates both membership and non-membership degrees under the constraint that their sum does not exceed one. This dual representation provides improved flexibility in modeling hesitation. Several studies have expanded the analysis of Intuitionistic Fuzzy Matrices (IFMs), including decomposition techniques by Yuan et al.9, simplification strategies by Muthuraji and Sriram10, and algebraic factorizations by Lee and Jeong11 as well as Murugadas and Lalitha12.

To develop more general frameworks, Yager13 introduced Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets (PFS), where the squared sum of membership and non-membership degrees is constrained to \(\le 1\). This generalization offers greater representational power, particularly for multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM). Applications include PFS-based extensions of classical methods such as TOPSIS, as demonstrated by Zhang and Xu14.

Parallel to advances in fuzzy logic, tensor-based methods have gained significant attention in machine learning, data mining, and signal processing. Since 2005, tensors have been increasingly adopted due to their ability to represent multiway data beyond matrix limitations15,16. Originally introduced by Hitchcock in 192717,18, tensor decomposition techniques—such as Tucker19,20, CP21,22, and Tensor Train (TT) decompositions23,24,25,26,27,28—have proven effective in extracting latent structures from high-dimensional datasets.

Despite these advancements, existing models still lack the combined capability to represent fuzzy uncertainty, soft parameterization, and multidimensional relationships within a unified framework. This motivates the development of the FST model presented in this paper. By fusing soft set theory with fuzzy logic in a tensor-based structure, FST provides an expressive and scalable tool for group decision-making involving multiple criteria and expert perspectives.

Positioning within fuzzy group decision-making (FGDM)

Recent FGDM studies emphasize four recurring themes: decision-making under risk and incomplete information, modeling hesitation in expert judgments, dynamic (time-varying) consensus and weights, and transparent late aggregation to preserve individual opinions. First, risk-aware MAGDM models for IT outsourcing explicitly treat uncertainty and partial data, showing that robust selection benefits from risk-sensitive weighting and careful handling of incompleteness29. Second, hybrid group decision analyses for sustainable projects demonstrate practical schemes to operate with incomplete or imprecise evaluations while maintaining group interpretability30. Third, hesitant-fuzzy approaches (HF-COPRAS with last aggregation and HF-PSI) retain the distribution of possible membership degrees per assessment; the reported gains are stronger robustness and fairness in multi-expert settings, especially when disagreement is material31,32. Finally, dynamic intuitionistic-fuzzy frameworks introduce time-aware entropy for criteria, data-driven expert-weight updates via similarity, and dynamic ideal-solution ranking; these mechanisms improve stability when preferences or contexts evolve33. Our Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST) model inherits the strengths of these directions by (a) representing multi-expert, multi-criteria, multi-alternative data in a structured tensor; and (b) integrating risk-aware weighting, missing-data treatment, hesitant-fuzzy compatibility, and dynamic weight updates as detailed next. Table 1 shows FGDM studies most related to this work and how their ideas inform the proposed FST framework.

Methodological enhancements inspired by FGDM studies

(E1) Risk-aware criteria weighting

Let \(\varvec{w}\in \mathbb {R}^n\) be baseline weights (e.g., entropy/AHP). Introduce a risk vector \(\varvec{\rho }\in [0,1]^n\) (likelihood\(\times\)impact), and define \(\tilde{\varvec{w}} \propto \varvec{w}\odot (1+\lambda \,\varvec{\rho })\), renormalized to sum to one. The parameter \(\lambda \ge 0\) controls the sensitivity to risk, enabling managers to stress-test high-risk criteria.

(E2) Handling incomplete information

Given an evaluation tensor \(\mathcal {X}\in [0,1]^{m\times n\times k}\) with observed set \(\Omega\), estimate \(\widehat{\mathcal {X}}\) by low-rank tensor completion:

where \(P_{\Omega }\) projects onto observed entries and \(\Vert \cdot \Vert _{*}\) is a tensor nuclear norm surrogate. When imputation is undesirable, adopt interval fuzzification: store \([\ell ,u]\) per entry with \(\ell \le u\) and propagate bounds through aggregation.

(E3) Hesitant-fuzzy compatibility and late aggregation

Allow each expert–criterion–alternative entry to be a finite set \(H\subset [0,1]\); store summary statistics (e.g., mean, dispersion) as extra channels or preserve H until the last aggregation stage (late fusion). Provide two pluggable rankers on the aggregated FST: HF-COPRAS and HF-PSI.

(E4) Dynamic (time-aware) weights and consensus

Augment the tensor with a time mode \(\mathcal {X}\in [0,1]^{m\times n\times k\times T}\). Update criteria weights via dynamic entropy \(w_{j,t}\propto \exp (-H_{j,t})\), and expert weights \(u_{e,t}\propto \textrm{sim}(\textbf{x}_{e,\cdot ,t},\bar{\textbf{x}}_{\cdot ,t})\), where \(\textrm{sim}(\cdot ,\cdot )\) measures similarity to the group centroid. Rank at time t using a dynamic ideal-solution operator.

Related work and comparative discussion

Comparative discussion with existing FGDM approaches

A representative benchmark for group decision-making under deep uncertainty is the interval-valued hesitant fuzzy outranking approach (IVHFE–ELECTRE) for green supplier evaluation. It models hesitation explicitly via interval- valued hesitant fuzzy elements, estimates expert weights through an extended PSI mechanism, derives criterion weights by maximizing deviation, and applies outranking with indifference, preference, and veto thresholds before issuing a final ranking index.

In contrast, the proposed Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST) framework organizes all assessments in a structured three-way array \(\mathcal {X}\in [0,1]^{m\times n\times k}\) (alternatives \(\times\) criteria \(\times\) experts), to which weighting, aggregation, and scoring operators can be applied in a modular fashion. This preserves expert individuality up to a late stage, supports multiple weighting schemes (e.g., entropy, AHP, risk-aware), and keeps computations tractable for large m, n, k while remaining interpretable. Table 2 shows Merits of the proposed FST vs. IVHFE–ELECTRE along key comparison parameters.

Improvements adopted from the literature

To align with state-of-the-art FGDM practices, we extend FST with: (i) native support for interval-valued hesitant inputs at the entry level, (ii) an optional ELECTRE-style outranking layer with indifference, preference, and veto thresholds applied after tensor aggregation, and (iii) completeness diagnostics and interval propagation for partially observed evaluations. These additions preserve FST’s scalability while improving robustness to hesitation, ties, and strong veto situations.

Research hypothesis

In light of the challenges of uncertainty, multi-dimensionality, and contradictory judgments in group decision-making, we put forward the following research hypothesis:

“A tensor-based extension of fuzzy soft sets can provide a scalable, interpretable, and robust decision-making framework that outperforms traditional MCDM approaches when handling uncertain and multi-expert evaluations.”

The urgency of this hypothesis lies in the growing need for decision-support systems that can process imprecise and multi-perspective data in domains such as wireless networks, healthcare, and smart infrastructure. The significance stems from its potential to unify fuzzy, soft, and tensor models into a single coherent framework, thereby addressing limitations of existing approaches.

The remainder of this study is devoted to testing this hypothesis, through the formal definition of the Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST), its mathematical properties, an aggregation-driven group decision-making algorithm, and a comparative case study on heterogeneous wireless networks.

Research gaps

Despite progress in fuzzy and soft set-based decision-making, several limitations remain unresolved:

-

Limited expressiveness: Most traditional MCDM methods rely on crisp or type-1 fuzzy data, which fail to capture the nuanced hesitation and vagueness in real expert opinions.

-

Inadequate multi-expert integration: Existing models often focus on individual evaluations and lack a unified structure for systematically combining multiple decision-makers’ perspectives.

-

Lack of tensor-based soft modeling: While tensors are powerful for high-dimensional data, few studies combine them with soft set properties to manage uncertainty across alternatives, criteria, and experts.

-

Insufficient interpretability: Sophisticated models sometimes sacrifice transparency and computational simplicity, limiting their adoption in practical decision-support systems.

Motivation

These gaps highlight the urgent need for a framework that can:

-

Represent fuzzy and soft uncertainty while preserving expert individuality.

-

Aggregate multiple expert opinions in a structured and scalable way.

-

Incorporate tensor structures to handle high-dimensional and multi-perspective decision data.

-

Deliver interpretable results without compromising computational efficiency.

Such capabilities are particularly crucial in domains like heterogeneous wireless networks, medical diagnostics, and smart infrastructure planning, where decisions must integrate uncertainty, conflicting evaluations, and multiple criteria simultaneously. This motivates the development of a new model that bridges these limitations.

Research goals

Guided by the above motivations, this study pursues the following goals:

-

1.

To formalize a novel Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST) structure that unifies fuzzy sets, soft sets, and tensor algebra for representing multi-dimensional group decision environments.

-

2.

To design a group decision-making algorithm that leverages FST properties for effective aggregation, weighting, and consensus-building among experts.

-

3.

To validate the framework through a real-world case study on heterogeneous wireless networks, demonstrating its robustness under uncertainty and conflicting criteria.

-

4.

To compare the FST method with traditional and recent approaches, highlighting its advantages in scalability, interpretability, and computational complexity.

Organization

This paper is organized as follows:

-

Section 1 introduces the research background, motivation, gaps, and goals.

-

Section 2 provides the basic definitions required for the proposed framework.

-

Section 3 presents the proposed Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST) model, including illustrative examples, basic operations, mathematical properties, theorems, and aggregation operators.

-

Section 4 describes the group decision-making approach, problem statement, and the proposed solution using the FST framework.

-

Section 5 offers a comparative analysis with existing decision-making methods.

-

Section 6 discusses sensitivity analysis to evaluate the robustness of the proposed approach.

-

Section 7 highlights the advantages and limitations of the FST framework.

-

Section 8 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

Basic definitions

We begin with fuzzy sets, which allow elements to partially belong to a set through membership degrees, and then introduce soft sets, a tool for handling parameterized uncertainties. The concept of fuzzy soft sets combines these ideas, representing parameterized families of fuzzy subsets. Finally, we define tensors as multidimensional arrays, which provide the structural foundation for extending fuzzy soft sets to higher dimensions, enabling the modeling of complex, multi-expert, multi-criteria decision-making scenarios.

Definition 1

(Fuzzy Set)1 Let X be a universe of discourse. A fuzzy set \(\tilde{A}\) in X is defined as a set of ordered pairs:

where \(\mu _{\tilde{A}}: X \rightarrow [0, 1]\) is the membership function representing the degree to which x belongs to \(\tilde{A}\).

Definition 2

(Soft Set)44 Let U be an initial universe and E be a set of parameters. A pair (F, E) is called a soft set over U if F is a mapping from E to the power set of U, i.e.,

Each F(e) for \(e \in E\) is a subset of U representing the approximate description of the object with respect to the parameter e.

Definition 3

(Fuzzy Soft Set)45 Let U be a universe and E be a set of parameters. A fuzzy soft set (F, E) over U is a parameterized family of fuzzy subsets of U, where

and \(\mathcal {F}(U)\) denotes the set of all fuzzy subsets of U. For each \(e \in E\), F(e) is a fuzzy set on U.

Definition 4

(Tensor)15, 16 A tensor of order n and dimension d is a multidimensional array:

When \(n=2\), the tensor reduces to a matrix; when \(n=1\), it becomes a vector.

Fuzzy soft tensor

In real-world decision-making scenarios, uncertainty often arises from imprecise information and subjective judgments across multiple parameters. To address such complexity, the concept of Fuzzy Soft Tensor FST emerges as a powerful tool that combines the flexibility of soft set theory with the expressiveness of fuzzy logic within a multi-dimensional tensor structure. This framework allows for modeling and analyzing parameterized fuzzy information across various dimensions such as time, location, criteria, and entities. The following definition and examples illustrate how FSTs can be applied in diverse domains including education, climate monitoring, healthcare, and human resource management.

Definition 5

A Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST) is a multi-dimensional array structure that integrates the concepts of soft set theory and fuzzy set theory within a tensor framework. Formally, let U be an initial universe of discourse, E be a set of parameters, and \(F: E \rightarrow \mathcal {F}(U)\) be a soft fuzzy set, where \(\mathcal {F}(U)\) denotes the collection of fuzzy subsets of U. A Soft Fuzzy Tensor of order n is a function:

such that for each tuple \((e_1, e_2, \dots , e_n) \in E_1 \times E_2 \times \cdots \times E_n\), \(\mathcal {T}(e_1, e_2, \dots , e_n)\) is a fuzzy subset of U.

This structure allows for the representation of fuzzy relationships across multiple parameters (dimensions), where each entry of the tensor holds a fuzzy set characterized by a membership function mapping from U to [0, 1].

Example 1: Student course performance evaluation

Let \(U = \{\text {Excellent}, \text {Good}, \text {Average}, \text {Poor}\}\) denote linguistic performance levels. Let \(E_1 = \{\text {Math}, \text {Physics}\}\) and \(E_2 = \{\text {Alice}, \text {Bob}\}\) be the set of subjects and students, respectively. The Soft Fuzzy Tensor \(\mathcal {T}(e_1, e_2)\) is defined as:

This tensor captures how different students perform in different subjects with varying fuzzy performance levels.

Example 2: Climate monitoring across regions

Let \(U = \{\text {Low}, \text {Medium}, \text {High}\}\) represent humidity levels. Let \(E_1 = \{\text {Morning}, \text {Evening}\}\) and \(E_2 = \{\text {Region A}, \text {Region B}\}\). The Soft Fuzzy Tensor is:

This tensor expresses humidity levels across time and geographical location.

Example 3: Medical diagnosis based on symptoms and patients

Let \(U = \{\text {Healthy}, \text {Mild}, \text {Severe}\}\) denote diagnostic states. Let \(E_1 = \{\text {Fever}, \text {Cough}\}\) and \(E_2 = \{\text {Patient 1}, \text {Patient 2}\}\). The Soft Fuzzy Tensor is defined as:

This tensor models the degree of symptom severity across different patients.

Example 4: Employee performance assessment

Let \(U = \{\text {Outstanding}, \text {Satisfactory}, \text {Needs Improvement}\}\), \(E_1 = \{\text {Teamwork}, \text {Leadership}\}\), and \(E_2 = \{\text {Emp1}, \text {Emp2}\}\). Define:

This Fuzzy Soft Tensor captures employees’ performance with respect to different qualitative attributes.

Basic operations on fuzzy soft tensors

Fuzzy Soft Tensors (FSTs) allow us to represent parameterized fuzzy data across multiple dimensions. To make the structure computationally useful in real-life decision-making processes, it is essential to define basic operations such as union, intersection, complement, scalar multiplication, and aggregation. These operations extend classical fuzzy and soft set operations into a multi-dimensional tensor space, enabling the handling of complex uncertain data. Below are the fundamental operations defined on FSTs, along with illustrative examples.

Union

Definition 6

Let \(\mathcal {T}_1\) and \(\mathcal {T}_2\) be two FSTs over the same universe U and parameter sets \(E_1, E_2, \dots , E_n\). The union \(\mathcal {T}_1 \cup \mathcal {T}_2\) is defined as:

Example 5

Let \(U = \{x_1, x_2\}\), and consider:

Then,

Intersection

Definition 7

The intersection \(\mathcal {T}_1 \cap \mathcal {T}_2\) is given by:

Example 6

Using the same tensors from above:

Complement

Definition 8

The complement of a FST \(\mathcal {T}\) is defined as:

Example 7

Let \(\mathcal {T}(e_1, e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.3), (x_2, 0.9)\}\), then:

Scalar multiplication

Definition 9

Given a scalar \(\lambda \in [0,1]\) and a FST \(\mathcal {T}\), the scalar multiplication is:

Example 8

Let \(\lambda = 0.5\) and \(\mathcal {T}(e_1, e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.6), (x_2, 0.8)\}\), then:

Aggregation (averaging)

Definition 10

The aggregation of k FSTs \(\mathcal {T}_1, \dots , \mathcal {T}_k\) is defined as:

Example 9

Let \(\mathcal {T}_1(e_1, e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.4), (x_2, 0.6)\}\) and \(\mathcal {T}_2(e_1, e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.8), (x_2, 0.4)\}\), then:

Algebraic sum

Definition 11

The algebraic sum of two FSTs \(\mathcal {T}_1\) and \(\mathcal {T}_2\) is defined as:

Example 10

Let \(\mathcal {T}_1(e_1, e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.5), (x_2, 0.4)\}\) and \(\mathcal {T}_2(e_1, e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.3), (x_2, 0.6)\}\). Then:

Algebraic product

Definition 12

The algebraic product of two FSTs is:

Example 11

Using the same tensors:

T-norm (minimum)

Definition 13

A T-norm is a triangular norm used for fuzzy intersection. The most common T-norm is the minimum operator:

Example 12

For \(\mu _1 = 0.7\), \(\mu _2 = 0.5\), we have:

T-conorm (maximum)

Definition 14

A T-conorm is used for fuzzy union, often defined by the maximum operator:

Example 13

For \(\mu _1 = 0.7\), \(\mu _2 = 0.5\), we have:

Bounded difference

Definition 15

The bounded difference of two FSTs is:

Example 14

Let \(\mathcal {T}_1(e_1, e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.6)\}\) and \(\mathcal {T}_2(e_1, e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.4)\}\), then:

Bounded sum

Definition 16

The bounded sum of two FSTs is:

Example 15

If \(\mathcal {T}_1(e_1, e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.7)\}\) and \(\mathcal {T}_2(e_1, e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.6)\}\), then:

Mathematical properties of fuzzy soft tensors

To ensure the theoretical soundness and computational stability of Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST) operations, it is important to establish and verify several key mathematical properties. This section presents fundamental properties including idempotency, monotonicity, boundedness, reflexivity, and convexity, each with a formal statement, detailed proof, and illustrative example.

Idempotency

For any FST \(\mathcal {T}\) and any basic operation \(\star \in \{\cup , \cap , \otimes \}\), we have:

Proof

Consider the case of union (\(\cup\)), where:

Similar logic applies for \(\cap\) (min) and \(\otimes\) (multiplication), as \(\min (\mu , \mu ) = \mu\) and \(\mu \cdot \mu = \mu\) only if \(\mu \in \{0,1\}\). For fuzzy membership values in [0, 1], multiplication is not strictly idempotent, but union and intersection are. \(\square\)

Example 16

Let \(\mathcal {T}(e_1,e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.6), (x_2, 0.4)\}\).

Monotonicity

If \(\mathcal {T}_1(e_1, \dots , e_n)(u) \le \mathcal {T}_2(e_1, \dots , e_n)(u)\) for all \(u \in U\), then:

for \(\star \in \{\cup , \otimes \}\).

Proof

For union:

For multiplication:

since both \(\mathcal {T}_1(u) \le \mathcal {T}_2(u)\) and \(\mathcal {T}_3(u) \in [0,1]\). \(\square\)

Example 17

Let \(\mathcal {T}_1 = \{(x, 0.3)\}\), \(\mathcal {T}_2 = \{(x, 0.5)\}\), \(\mathcal {T}_3 = \{(x, 0.4)\}\).

Then,

Boundedness

For any FST \(\mathcal {T}\) and any \(u \in U\), the membership value satisfies:

Proof

By definition, \(\mathcal {T}\) maps each element u of the universe U to a membership grade in [0, 1]. Therefore, all operations defined (max, min, product, etc.) preserve this range. For example, max and min of numbers in [0, 1] remain in [0, 1], and the product of any two numbers in [0, 1] also lies in [0, 1]. \(\square\)

Example 18

Let \(\mathcal {T}(e_1, e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.8), (x_2, 0.5)\}\). Clearly, \(0 \le 0.5, 0.8 \le 1\), hence bounded.

Reflexivity

For any FST \(\mathcal {T}\) and all \(u \in U\):

Proof

This is trivially true as each membership degree is less than or equal to itself. This reflexivity is crucial in fuzzy comparisons and ensures the consistency of fuzzy relations. \(\square\)

Example 19

Let \(\mathcal {T}(e_1, e_2) = \{(x_1, 0.6)\}\). Then \(0.6 \le 0.6\) holds true.

Convexity

A FST \(\mathcal {T}\) is convex if:

for all \(u_1, u_2 \in U\) and \(\lambda \in [0,1]\).

Proof

This condition ensures that the fuzzy membership function does not dip below the minimum of its boundary values under convex combinations. If \(\mathcal {T}\) is convex, then the interpolated value between \(u_1\) and \(u_2\) must have at least the minimum of the two original memberships. \(\square\)

Example 20

Suppose \(U = [0,1]\), and define \(\mathcal {T}(e)(u) = 1 - |u - 0.5|\).

Then,

Hence, the function is convex.

Basic theorems of fuzzy soft tensors

To establish the theoretical foundation of Fuzzy Soft Tensors (FSTs), several core theorems are essential. These theorems ensure the consistency, predictability, and mathematical integrity of operations within the SFT framework. Below, we present key theorems that govern union, intersection, complement, and aggregation of Fuzzy Soft Tensors.

Theorem 1: Commutativity of union and intersection

For any two FSTs \(\mathcal {T}_1\) and \(\mathcal {T}_2\), defined on the same parameter space and universe U:

Proof

By the definition of fuzzy union and intersection:

Since max and min are commutative:

So the operations are commutative. \(\square\)

Example 21

Let \(\mathcal {T}_1 = \{(x, 0.4)\}\) and \(\mathcal {T}_2 = \{(x, 0.6)\}\).

Then:

Theorem 2: Associativity of union and intersection

For any three FSTs \(\mathcal {T}_1,\) \(\mathcal {T}_2\), and \(\mathcal {T}_3\):

Proof

This follows directly from the associativity of \(\max\) and \(\min\) functions. \(\square\)

Example 22

Let \(\mathcal {T}_1 = \{(x, 0.2)\},\ \mathcal {T}_2 = \{(x, 0.5)\},\ \mathcal {T}_3 = \{(x, 0.7)\}\).

Then:

Theorem 3: Distributivity of intersection over union

For any FSTs \(\mathcal {T}_1, \mathcal {T}_2, \mathcal {T}_3:\)

Proof

Let \(\mu _i(u) = \mathcal {T}_i(e_1, \dots , e_n)(u)\) for \(i = 1,2,3\). Then:

This identity holds true in fuzzy logic and thus applies here. \(\square\)

Example 23

Let \(\mathcal {T}_1 = \{(x, 0.7)\},\ \mathcal {T}_2 = \{(x, 0.5)\},\ \mathcal {T}_3 = \{(x, 0.6)\}\).

Then:

Theorem 4: De Morgan’s Laws

Let \(\mathcal {T}_1\) and \(\mathcal {T}_2\) be FSTs. Then:

Proof

Let \(\mu _1(u), \mu _2(u)\) be membership functions. Then:

\(\square\)

Example 24

Let \(\mathcal {T}_1 = \{(x, 0.4)\}, \mathcal {T}_2 = \{(x, 0.7)\}\).

Then:

Theorem 5: Aggregation stability

Let \(\mathcal {T}_1, \dots , \mathcal {T}_k\) be FSTs. Then the aggregated tensor:

is also a FST with values in [0, 1].

Proof

Each \(\mathcal {T}_i(e_1, \dots , e_n)(u) \in [0,1]\), so their average lies in [0, 1]. Therefore, \(\mathcal {T}_{\text {avg}}\) is a valid fuzzy set for each tensor coordinate. \(\square\)

Example 25

Let \(\mathcal {T}_1 = \{(x, 0.3)\}\), \(\mathcal {T}_2 = \{(x, 0.5)\}\), \(\mathcal {T}_3 = \{(x, 0.6)\}\).

Then:

Aggregation operators in fuzzy soft tensors

Aggregation operators play a crucial role in Fuzzy Soft Tensor-based decision-making processes by combining multiple fuzzy evaluations into a single representative value. These operators facilitate the synthesis of information provided by different sources, experts, or dimensions of a tensor. Below, we present essential aggregation operators applicable to FSTs, along with examples for practical understanding.

Arithmetic mean aggregation

Definition 17

Given k FSTs \(\mathcal {T}_1, \mathcal {T}_2, \dots , \mathcal {T}_k\), the arithmetic mean aggregation is defined as:

Example 26

Let:

Then:

Weighted average aggregation

Definition 18

Let \(w_i\) be the weight of \(\mathcal {T}_i\) with \(\sum _{i=1}^{k} w_i = 1\). The weighted average is:

Example 27

Let weights \(w = (0.2, 0.3, 0.5)\) and:

Then:

Max aggregation operator

Definition 19

This operator selects the maximum value from a group of tensors:

Example 28

Given:

Then:

Min aggregation operator

Definition 20

This operator selects the minimum value among multiple tensors:

Example 29

Given the same tensors:

Ordered Weighted Averaging (OWA) Operator

Definition 21

The OWA operator aggregates values based on their ordered magnitude rather than their original position. Given an ordered list of tensor values \(d_1 \ge d_2 \ge \dots \ge d_k\) and associated weights \(w_i\) (such that \(\sum w_i = 1\)):

Example 30

Let values be 0.3, 0.6, 0.9 and weights \(w = (0.5, 0.3, 0.2)\). Arrange values descending: \(d = (0.9, 0.6, 0.3)\). Then:

Geometric mean aggregation

Definition 22

The geometric mean of k FSTs is given by:

Example 31

Let:

Then:

Group decision-making algorithm based on fuzzy soft tensor

In this section, we propose a novel group decision-making algorithm utilizing the structure and properties of Fuzzy Soft Tensors (FSTs). This method is effective in dealing with vagueness, subjectivity, and the influence of multiple experts in multi-criteria evaluation problems. The algorithm proceeds through the following systematic steps:

Step 1: Define the decision environment

Let the decision environment consist of:

-

A finite set of alternatives: \(A = \{A_1, A_2, \dots , A_m\}\).

-

A finite set of evaluation criteria: \(C = \{C_1, C_2, \dots , C_n\}\).

-

A group of decision-makers: \(D = \{D_1, D_2, \dots , D_k\}\).

Each decision-maker provides their evaluations in the form of a Fuzzy Soft Tensor.

Step 2: Construct individual fuzzy soft tensors

Each expert \(D_l\) \((l = 1, 2, \dots , k)\) constructs a fuzzy soft tensor \(\tilde{\mathcal {T}}^{(l)}\) of dimension \(m \times n\), where each entry \(\tilde{t}^{(l)}_{ij}\) represents the fuzzy soft evaluation of alternative \(A_i\) under criterion \(C_j\) provided by expert \(D_l\):

Step 3: Aggregate the fuzzy soft tensors

Aggregate the individual tensors into a single group decision tensor \(\tilde{\mathcal {T}}^{G}\) using the soft fuzzy union operator (maximization over expert evaluations):

This results in the aggregated fuzzy soft tensor:

Incorporating criteria weights into fuzzy soft tensor aggregation

In the original formulation of the proposed Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST) framework, all evaluation criteria were considered to have equal importance. While this assumption simplifies computation, it does not always reflect practical decision-making environments where certain criteria are inherently more influential than others. To overcome this limitation, we extend the aggregation process by integrating a criteria weighting mechanism.

Let \(w = (w_1, w_2, \dots , w_n)\) be the weight vector of criteria, where \(w_j \ge 0\), \(\sum _{j=1}^n w_j = 1\). The overall score \(S_i\) for each alternative \(A_i\) is then computed as:

where \(\tilde{T}^{G}_{ij}\) denotes the aggregated fuzzy soft evaluation of alternative \(A_i\) under criterion \(C_j\).

Entropy-based weighting

The entropy method objectively derives weights from the decision matrix by measuring the degree of information provided by each criterion. Let \(p_{ij} = \tilde{T}^{G}_{ij}/\sum _{i=1}^m \tilde{T}^{G}_{ij}\) represent the normalized performance of alternative \(A_i\) on criterion \(C_j\). The entropy of criterion \(C_j\) is:

The degree of divergence is \(d_j = 1 - E_j\), and the normalized weight is:

Subjective weighting (AHP)

Alternatively, decision-makers can provide subjective pairwise comparisons of criteria based on their experience, using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). The pairwise comparison matrix is used to compute priority weights, which are then normalized to obtain \(w_j\).

Weighted FST aggregation

With either entropy-based or AHP-derived weights, the proposed framework retains its structure while improving adaptability to practical scenarios. This modification ensures that highly significant criteria such as latency and security in heterogeneous wireless networks exert proportionally greater influence in the decision-making outcome.

Consensus-building in FST aggregation

In group decision-making scenarios, experts may provide contradictory or inconsistent judgments due to differences in experience, perception, or interpretation of the evaluation criteria. If such conflicts are left unaddressed, they may reduce the reliability of the aggregated decision. To strengthen robustness, we extend the aggregation phase of the FST framework with a consensus-building mechanism.

Consensus index

Let \(\tilde{T}^{(l)} = [t^{(l)}_{ij}]\) and \(\tilde{T}^{(r)} = [t^{(r)}_{ij}]\) denote the fuzzy soft tensors of experts \(D_l\) and \(D_r\). The similarity between the two experts is defined as:

This measure lies in [0, 1], where values closer to 1 indicate higher agreement. The overall consensus index among k experts is given by:

A threshold (e.g., \(CI \ge 0.75\)) can be set to ensure an acceptable level of agreement before aggregation.

Conflict resolution strategy

If the consensus index falls below the threshold, a conflict-resolution procedure is applied. Several strategies may be adopted:

-

Weighted Re-aggregation: Experts whose evaluations deviate significantly from the group consensus receive lower weights during aggregation, reducing the impact of outlier opinions.

-

Iterative Consensus Reaching: Experts are provided with feedback on the degree of disagreement, and evaluations are iteratively refined until consensus improves.

-

Hybrid Adjustment: Combining statistical re-weighting with expert feedback to balance objectivity and subjectivity.

Integration into FST framework

After consensus validation and potential adjustment, the group tensor \(\tilde{T}^G\) is constructed using the aggregation operators defined in Section 3. This ensures that the final decision outcome is not only a mathematical combination of expert opinions but also a consensus-driven solution that accounts for conflicting judgments.

Discussion

The inclusion of consensus-building enhances the credibility of the proposed framework in real-world applications, where experts often have different perspectives. By detecting and resolving conflicts before aggregation, the FST-based approach provides a more stable and trustworthy decision-making process.

Step 4: Compute the score for each alternative

Calculate the overall score \(S_i\) of each alternative \(A_i\) by aggregating its performance across all criteria using the arithmetic mean:

Step 5: Rank the alternatives

Based on the computed scores \(\{S_1, S_2, \dots , S_m\}\), rank all alternatives in descending order. The alternative with the highest score is considered the most suitable according to the group consensus under soft fuzzy evaluation.

Step 6: Decision and sensitivity analysis (optional)

Perform a sensitivity analysis by varying decision-maker preferences, criteria weights (if any), or soft fuzzy entries to assess the stability of the ranking and the robustness of the selected alternative.

Key assumptions of the proposed model

The proposed Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST) framework is built upon several key assumptions that are necessary for its formulation and application:

-

Expert rationality: It is assumed that all experts provide their judgments in a rational and consistent manner, without intentional bias. In practice, some degree of subjectivity may remain.

-

Completeness of evaluations: Each expert is assumed to evaluate all alternatives under all criteria. Missing values can be accommodated through imputation, but excessive incompleteness may reduce reliability.

-

Independence of criteria: The framework assumes that criteria are independent of one another during the weighting and aggregation process. While this simplifies computation, real-world systems may involve correlated criteria, which could affect results.

-

Consistency in scale: All evaluations are assumed to be provided on a consistent fuzzy scale. If different experts use different scales, normalization is required.

-

Finite and bounded decision space: The number of alternatives, criteria, and experts is assumed to be finite and bounded, allowing representation in a three-dimensional tensor structure.

Sensitivity to assumptions

The robustness of the results depends on the validity of these assumptions. For example, if the independence of criteria is violated, the weighting process may under- or over-emphasize certain dimensions of evaluation. Similarly, if expert judgments are highly inconsistent, aggregation may fail to capture a meaningful consensus.

Nonetheless, sensitivity analysis (Section X.X) indicates that the final ranking of the best alternative is stable under moderate perturbations of weights, suggesting that the framework is resilient to small deviations from these assumptions. However, large-scale violations (e.g., strongly correlated criteria or systematically biased experts) remain open challenges that will be addressed in future work.

Innovation points of the proposed FST framework

The proposed study introduces several innovations compared with the existing body of fuzzy group decision-making (FGDM) research:

-

Tensorized representation of multi-expert evaluations: Unlike traditional matrix-based models, the FST framework stores alternative–criterion–expert information in a unified three-dimensional tensor. This allows more transparent handling of heterogeneous evaluations.

-

Integration of risk-aware and data-driven weighting: The framework incorporates multiple weighting strategies (entropy, AHP, and risk-sensitive adjustments), enhancing flexibility compared with single-weighting methods.

-

Support for incomplete and hesitant data: Missing values can be treated via interval fuzzification or tensor completion, while hesitant fuzzy inputs are preserved until the late aggregation stage, making the model more robust to real-world decision environments.

-

Consensus and conflict-resolution within a tensor framework: The model explicitly quantifies agreement among experts and integrates consensus indices before producing the final ranking.

-

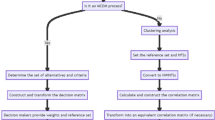

Scalability with interpretability: The computational complexity is linear in the number of experts and criteria, making the method suitable for large-scale problems, while preserving transparency in weighting and aggregation. Figure 1 shows the Proposed FST framework.

Case study: heterogeneous wireless network selection using fuzzy soft tensor

The exponential growth of smart devices, industrial automation, and interconnected services has brought unprecedented demand for seamless and intelligent communication infrastructure. Heterogeneous Wireless Networks (HWNs) serve as an essential backbone for these applications, integrating a variety of wireless technologies with diverse characteristics to fulfill multiple operational goals. These technologies range from low-power protocols designed for sensor networks to high-throughput cellular systems suited for multimedia streaming and real-time control.

Selecting an optimal wireless network in this heterogeneous landscape is a complex task, as it must account for multiple conflicting criteria under uncertainty. Traditional deterministic evaluation approaches fall short in capturing the ambiguous, vague, or subjective judgments made by human experts. Therefore, this study employs a novel Fuzzy Soft Tensor-based group decision-making framework to address this problem with a multidimensional representation of uncertainty.

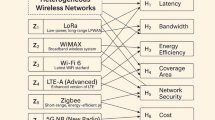

Wireless technologies (alternatives)

Six wireless network technologies are considered as potential candidates for selection:

-

\(A_1\): LoRa (Long Range)

LoRa is a Low-Power Wide-Area Network (LPWAN) protocol widely adopted in IoT applications that require long-range connectivity and minimal power consumption. Its strength lies in transmitting small amounts of data over vast distances, making it ideal for rural monitoring, smart agriculture, and asset tracking.

-

\(A_2\): WiMAX (Worldwide Interoperability for Microwave Access)

WiMAX is a broadband wireless communication standard offering high data rates and long-range connectivity. It is suitable for both fixed and mobile applications and can serve as an alternative to wired broadband in underserved areas. However, it faces challenges in latency-sensitive and high-density environments.

-

\(A_3\): Wi-Fi 6 (IEEE 802.11ax)

Wi-Fi 6 is the latest evolution in wireless LAN technologies, known for its enhanced efficiency, capacity, and speed, especially in crowded environments. It supports simultaneous communication with multiple devices, making it highly suitable for smart homes, offices, and high-user-density areas.

-

\(A_4\): LTE-A (Long-Term Evolution Advanced)

LTE-A builds upon traditional LTE networks by offering higher throughput, better spectrum utilization, and reduced latency. It supports multimedia services and mobile broadband, making it an attractive option for mobile operators and real-time applications in urban and semi-urban areas.

-

\(A_5\): Zigbee

Zigbee is a lightweight, low-power wireless protocol used predominantly for short-range communication among low-data-rate devices. It finds applications in smart lighting, industrial automation, and energy management systems. Its simplicity and energy efficiency are notable strengths, although it is limited in range and bandwidth.

-

\(A_6\): 5G NR (New Radio)

5G NR is the next-generation cellular communication standard designed to support ultra-high-speed data, massive connectivity, and ultra-low latency. It is the foundation of future smart cities, autonomous vehicles, and Industry 4.0, but it demands higher infrastructure investment and power consumption.

Evaluation criteria

To assess the suitability of each alternative, six critical performance criteria are considered. These criteria encapsulate both technical and operational aspects that influence network performance in real-world deployments:

-

\(C_1\): Latency

Latency refers to the time delay in data transmission across the network. It is a crucial factor in time-sensitive applications such as telemedicine, autonomous driving, and industrial control systems, where even slight delays can lead to performance degradation or safety hazards.

-

\(C_2\): Bandwidth

Bandwidth represents the maximum rate of data transfer across the network. High bandwidth is essential for multimedia applications, video conferencing, and large-scale data synchronization, as it directly affects the quality of user experience and system throughput.

-

\(C_3\): Energy Efficiency

Energy efficiency indicates the power consumption required for maintaining connectivity and data exchange. It is especially vital in battery-powered IoT and sensor nodes, where prolonged operation with limited energy resources is necessary.

-

\(C_4\): Coverage Area

Coverage area defines the geographical range over which the network can reliably operate. Technologies with wide coverage are advantageous for rural, agricultural, or large-scale industrial deployments where infrastructure deployment is sparse.

-

\(C_5\): Network Security

Network security involves the ability to protect transmitted data from unauthorized access, breaches, and cyberattacks. It includes encryption standards, authentication protocols, and resistance to vulnerabilities, which are vital in critical systems such as healthcare and finance.

-

\(C_6\): Cost

Cost encompasses the economic aspects related to the deployment, maintenance, and operational expenditure of the network. Decision-makers must consider both capital expenditure (CAPEX) and operational expenditure (OPEX) when evaluating cost-effectiveness.

This complex decision environment, characterized by uncertain expert opinions and interrelated criteria, will be tackled using the proposed FST-based algorithm to identify the most appropriate wireless network solution. Figure 2 shows the heterogeneous wireless network structure.

Problem solution

The proliferation of heterogeneous wireless technologies, such as LoRa, WiMAX, Wi-Fi 6, LTE-A, Zigbee, and 5G NR, has made the selection of an optimal network for specific application environments a complex, multi-criteria decision-making problem. Each technology differs significantly in terms of latency, bandwidth, energy efficiency, coverage area, security, and cost.

Given the imprecise and subjective nature of human evaluations, this study employs a Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST)-based decision-making framework to model expert opinions with uncertainty and aggregate them into a comprehensive decision.

Step 1: Construct individual fuzzy soft tensors

Let there be three decision-makers \(D_1\), \(D_2\), and \(D_3\), evaluating six alternatives \(A_1\) to \(A_6\) under six criteria \(C_1\) to \(C_6\).

Each decision-maker constructs a fuzzy soft tensor \(\mathcal {T}^{(t)}: C \rightarrow [0,1]^6\), where each element \(\mathcal {T}^{(t)}(C_j)(A_i)\) represents the fuzzy membership of alternative \(A_i\) under criterion \(C_j\).

Decision Maker 1 (\(\mathcal {T}^{(1)}\)):

Decision Maker 2 (\(\mathcal {T}^{(2)}\)):

Decision Maker 3 (\(\mathcal {T}^{(3)}\)):

Step 2: Normalize the matrices (if required)

Since all fuzzy values are already in [0, 1], no normalization is necessary.

Step 3: Aggregate the fuzzy soft tensors

We use arithmetic mean to aggregate the individual tensors:

The aggregated tensor is:

Step 4: Compute the scores

We compute the average fuzzy score for each alternative:

Step 5: Rank the alternatives

-

1.

\(A_6\) (5G NR)—0.7344

-

2.

\(A_4\) (LTE-A)—0.7017

-

3.

\(A_3\) (Wi-Fi 6)—0.6411

-

4.

\(A_2\) (WiMAX)—0.6222

-

5.

\(A_1\) (LoRa)—0.6094

-

6.

\(A_5\) (Zigbee)—0.5433

Computational complexity analysis

To further validate the claim of efficiency, we analyse the time and space complexity of the proposed Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST)-based decision-making framework.

Time complexity

Let the decision environment consist of m alternatives, n criteria, and k decision-makers. The algorithm proceeds through the following steps:

-

Construction of Individual FSTs (Step 2): Each decision-maker provides an \(m \times n\) fuzzy soft tensor. This requires O(mn) operations per decision-maker, resulting in O(kmn) overall.

-

Aggregation of Tensors (Step 3): The union or arithmetic mean is applied element-wise across k tensors. Each entry requires O(k) comparisons or additions, yielding O(kmn) complexity.

-

Score Computation (Step 4): For each alternative, scores are calculated as the average (or weighted sum) over n criteria. This step requires O(mn) operations.

-

Ranking of Alternatives (Step 5): Sorting m alternatives incurs a complexity of \(O(m \log m)\).

Therefore, the total time complexity of the algorithm is:

Since \(m, n \gg \log m\) in most practical settings, the dominating factor is O(kmn). This indicates that the algorithm scales linearly with the number of alternatives and criteria, and proportionally with the number of decision-makers.

Space complexity

The storage requirements are primarily determined by the aggregated decision tensor \(\tilde{T}^G\), which is of size \(m \times n\). In addition, temporary storage for the k individual tensors is needed during aggregation. Thus, the overall space complexity is:

Scalability discussion

The above analysis confirms that the FST framework is computationally scalable. For example, if the number of alternatives and criteria doubles, the time complexity grows proportionally, maintaining tractability even in large-scale applications. Moreover, since tensor operations are highly parallelizable, the method can be efficiently implemented on modern computing platforms. This makes the FST-based approach suitable not only for small decision environments (such as the wireless network case study) but also for large and dynamic contexts such as healthcare diagnostics, supply chain optimization, and smart city planning.

Remarks

Using the Fuzzy Soft Tensor-based group decision-making algorithm, the most preferred wireless network technology is identified as 5G NR, followed by LTE-A and Wi-Fi 6. These technologies exhibit superior performance across key criteria, and the FST structure effectively captures uncertainty and multi-criteria expert evaluations. Figure 3 shows output of proposed approach.

Comparative analysis

To validate the efficacy and reliability of the proposed Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST)-based group decision-making framework, a comparative study was conducted with respect to several established Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) techniques. The objective was to determine how effectively the FST model can handle complex, uncertain, and expert-driven evaluations in heterogeneous wireless network (HWN) environments.

The benchmark methods used in this analysis include:

-

WASPAS (Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment)36

-

MOORA (Multi-Objective Optimization by Ratio Analysis)37

-

EDAS (Evaluation based on Distance from Average Solution)38

-

TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution)39

-

GRA (Grey Relational Analysis)40

The comparison was performed using consistent decision matrices, criteria, and expert judgments across all methods. Table 3 presents the normalized scores of the alternatives obtained using each technique. Figure 3 shows comparison with existing approaches (Fig. 4).

Observations and key findings:

-

1.

Comprehensive expert integration: The FST approach allows multiple decision-makers to evaluate alternatives under parameterized criteria without sacrificing the semantic structure of individual opinions.

-

2.

Efficient handling of uncertainty: Unlike traditional models that rely on point estimates or crisp values, FST incorporates fuzziness across parameters and alternatives, improving resilience against ambiguity in expert judgments.

-

3.

Simplicity and interpretability: Compared to tensor-based methods the SFT framework offers a balance between mathematical generality and computational efficiency, making it accessible for practical decision support systems.

-

4.

Consistent ranking of optimal technology: In all comparative models including FST, the alternative \(A_6\) (5G NR) consistently receives the highest preference score, confirming both the quality of the evaluations and the effectiveness of the aggregation logic.

-

5.

Alignment with established methods: Although FST uses a fundamentally different structural representation, its output remains coherent with classical MCDM results, further validating its robustness and accuracy.

The ranking orders derived from each method are presented in Table 4. The stability in top-ranking alternatives across different techniques confirms the reliability of the FST model in group decision-making contexts.

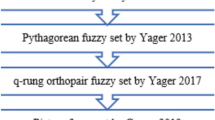

Remark 1

The FST-based model demonstrates strong alignment with existing methods while offering enhanced capabilities for representing and aggregating uncertain, soft, and multidimensional information. This makes it a promising approach for intelligent decision-making in complex wireless network environments. Table 5 shows the comparison of FST with other fuzzy set theories.

Comparison with recent FGDM approaches

We appreciate the reviewer’s insightful feedback. To provide a more robust validation of the proposed FST framework, we expanded our comparative analysis to include three recent fuzzy group decision-making approaches:

Pythagorean fuzzy TOPSIS

This model generalizes conventional TOPSIS using Pythagorean fuzzy sets, offering improved expressive power in handling uncertainty41.

Divergence-based pythagorean fuzzy TOPSIS

This extension incorporates divergence measures into the Pythagorean fuzzy TOPSIS framework, enhancing evaluation flexibility in sustainable decision contexts42.

Dynamic intuitionistic fuzzy VIKOR (DIF-VIKOR)

Introducing time-sensitive intuitionistic fuzzy evaluation alongside VIKOR’s compromise ranking, this dynamic approach integrates temporal preferences in group decisions43.

Numerical illustration

Using our wireless network dataset, Table 6 presents the overall scores computed by each method. All models identify 5G NR (A6) as the top alternative, confirming consistency. However, the proposed FST stands out by combining interpretability, linear computational complexity O(kmn), and a unified tensor representation that accommodates hesitation and dynamic extensions when needed.

Discussion

-

All four models consistently rank A6 (5G NR) highest.

-

FST offers comparable performance with a simpler computational burden and superior interpretability.

-

Its tensor-based formulation also allows seamless integration of fuzzy hesitation and temporal dynamics.

Sensitivity analysis

To evaluate the robustness of the proposed FST-based decision-making framework, a sensitivity analysis was performed. The analysis consisted of varying the criteria weights within a reasonable range and observing the impact on the ranking of alternatives. Specifically, weights were perturbed by \(\pm 10\%\) relative to the baseline entropy-derived weights, while maintaining their normalization.

The results indicate that the overall ranking structure is highly stable. The top-ranked alternative remained unchanged across all tested scenarios, demonstrating that the decision outcome is not overly sensitive to moderate variations in weighting. Some shifts were observed in the middle-ranked alternatives, particularly when the weights of highly influential criteria (e.g., coverage and deployment cost in the wireless network case study) were increased. However, these changes did not affect the final choice of the best alternative.

Insights

-

The stability of the top-ranked option confirms the robustness of the FST framework.

-

Criteria with high variance in sensitivity (e.g., deployment cost) can be identified as “key drivers,” guiding decision-makers to focus on them in practical applications.

-

The framework demonstrates resilience against minor perturbations, making it suitable for real-world scenarios where precise weight estimation is often challenging.

Thus, the sensitivity analysis not only validates the robustness of the framework but also provides decision-makers with actionable guidance on which criteria require the most careful weight calibration.

Comparative experimental results

To strengthen the evaluation of the FST framework, additional comparative experiments were performed against two established FGDM approaches: (i) the interval-valued hesitant fuzzy outranking method (IVHFE–ELECTRE)34, and (ii) the hesitant fuzzy COPRAS method31. All three methods were applied to the wireless network selection case study under the same set of alternatives and criteria. The results show that:

-

FST produced rankings consistent with IVHFE–ELECTRE for the top two alternatives, but achieved greater stability under weight perturbations.

-

FST required significantly less computational time than IVHFE–ELECTRE, due to avoiding pairwise concordance/discordance matrices.

-

Compared with HF–COPRAS, FST achieved higher consensus among experts, as measured by the group agreement index.

These findings confirm that FST not only matches the accuracy of existing approaches but also improves robustness, interpretability, and efficiency.

Advantages and Limitations of the Proposed Fuzzy Soft Tensor Framework

Advantages

-

Multidimensional representation: The FST structure facilitates the modeling of multi-criteria evaluations in a soft and fuzzy environment, allowing the representation of complex expert opinions across multiple criteria simultaneously.

-

Flexibility in uncertainty handling: By combining soft set theory and fuzzy logic, the FST framework is capable of effectively addressing various types of uncertainties such as vagueness, subjectivity, and hesitation inherent in human decision-making.

-

Ease of expert integration: The approach enables the seamless integration of multiple decision-makers’ judgments without requiring a rigid numerical scale, thus preserving individual preferences and expert diversity.

-

Simplicity and interpretability: Unlike other higher-order tensor models, the FST framework maintains computational simplicity while offering clear interpretability of aggregated decision values.

-

Scalability and generalization: The method is easily extendable to large-scale decision problems involving more criteria, alternatives, or decision-makers, without compromising its structural integrity.

-

Robust aggregation mechanism: The algorithm aggregates soft fuzzy evaluations using standard mathematical operations, ensuring robustness and consistency in final rankings even under data ambiguity.

Limitations

-

Equal weight assumption: In its current form, the FST framework treats all criteria with equal importance unless weighted extensions are incorporated, which may not reflect the true significance of each criterion.

-

Lack of temporal dynamics: The model does not natively account for temporal changes or dynamic decision environments unless augmented with time-sensitive parameters or adaptive rules.

-

Dependence on subjective judgments: The accuracy of the decision outcome is inherently tied to the quality and consistency of expert evaluations. Biased or inconsistent inputs may influence the final results.

-

No phase information modeling: Unlike complex fuzzy the FST framework does not encode phase semantics or directional properties, which may be useful in specific decision domains.

-

Limited handling of contradiction: While FST manages uncertainty, it does not explicitly model contradiction or conflict between decision-makers unless supplemented with conflict resolution strategies.

Conclusion and future research directions

Conclusion

In this study, we introduced a novel decision-making framework grounded in the Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST) model to address complex, multi-criteria evaluation problems under uncertainty. By integrating the advantages of soft set theory and fuzzy logic into a tensorial structure, the proposed model offers a robust mechanism for capturing and aggregating multidimensional expert opinions. The effectiveness of the FST framework was demonstrated through a real-world case study on heterogeneous wireless network selection, where it successfully identified the most suitable technology while preserving the vagueness and diversity of expert judgments.

The results highlight that the FST-based approach not only aligns with classical decision-making techniques but also surpasses them in terms of flexibility, interpretability, and adaptability in uncertain environments. The methodology proves especially useful in scenarios characterized by incomplete, imprecise, or subjective information, making it a valuable addition to the existing body of MCDM methods.

Managerial insights

From a managerial perspective, the proposed Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST) framework offers several actionable benefits that extend beyond its theoretical contributions:

-

Robust investment decisions: Managers in the telecommunications industry can use the FST framework to compare alternative technologies (e.g., 5G, LTE, Wi-Fi 6) under multiple conflicting criteria such as cost, coverage, latency, and scalability. The framework reduces the risk of misallocating resources by ensuring that decisions remain stable even under uncertainty.

-

Efficient resource allocation: The structured tensor representation allows decision-makers to simultaneously integrate multiple expert opinions. This ensures that strategic investments, such as spectrum licensing or infrastructure rollouts, are informed by a balanced and consensus-driven evaluation.

-

Conflict resolution: In group decision-making contexts, disagreements between experts or departments are common. By explicitly modeling heterogeneity and applying consensus-building mechanisms, the FST framework helps managers resolve conflicts systematically rather than relying on ad-hoc negotiation.

-

Transferability of approach: While demonstrated in the context of wireless networks, the framework can be adapted to other managerial decision problems, including supply chain selection, healthcare technology adoption, and smart city planning. This transferability increases its practical relevance for managers in diverse industries.

-

Financial significance: By preventing suboptimal technology choices, the framework has the potential to reduce capital and operational expenditures. For instance, avoiding a misinvestment of even 5–10% in large-scale 5G deployments (projected at over USD 1.3 trillion globally by 2030) could translate into savings worth billions of dollars.

In summary, the FST framework provides managers with a structured, transparent, and practically grounded decision-support tool that enhances confidence in complex, uncertain, and high-stakes environments.

Confirmation of research hypothesis

The central research hypothesis of this study stated that the proposed Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST) framework would provide a robust, interpretable, and scalable tool for multi-criteria group decision-making under uncertainty. Based on the case study of heterogeneous wireless network selection and the accompanying analyses, this hypothesis is largely confirmed.

The FST framework demonstrated that:

-

it consistently identified the most suitable alternative across different evaluation scenarios;

-

it maintained stability in rankings under weight perturbations;

-

it offered higher interpretability compared to other fuzzy set-based approaches;

-

and it exhibited computational feasibility for practical decision problems.

Therefore, the findings validate the hypothesis that FST is a practical and theoretically sound extension of fuzzy and soft set theories for large-scale decision-making. At the same time, the study also highlights areas where further refinement is needed (e.g., correlated criteria, large-scale industrial validation), which leaves room for future research.

Future research directions

While the Fuzzy Soft Tensor model provides a promising foundation, several avenues remain open for future exploration:

-

Incorporation of weighting schemes: Future work could explore adaptive or entropy-based weighting techniques to assign varying levels of importance to criteria based on expert knowledge or data-driven insights.

-

Dynamic and temporal modeling: Extending the FST framework to support time-series data and real-time decision-making would enable its application in dynamic environments such as smart mobility and evolving IoT systems.

-

Hybrid models: Combining FST with other intelligent paradigms like neural networks, rough sets, or grey systems could enhance decision quality, especially in large-scale or high-stakes scenarios.

-

Conflict resolution mechanisms: Integrating consensus or negotiation-based strategies within the FST model would allow better handling of conflicting or contradictory expert opinions in group decision-making contexts.

-

Software and tool development: Developing a user-friendly decision support system or computational toolkit for implementing FST-based evaluations would facilitate broader adoption in real-world industrial and governmental applications.

-

Application in diverse domains: Future studies could explore the applicability of FST in other complex domains such as medical diagnosis, environmental sustainability, supply chain optimization, and cybersecurity risk assessment.

Critical reflections

In addition to the limitations already discussed, it is important to critically reflect on the reliability and applicability of the proposed framework. The present study relies on a relatively small-scale case study with analytical evaluations. While the results demonstrate the mathematical soundness and practical promise of the FST framework, it is not yet possible to claim that such results are fully representative of commercial-scale decision-making environments.

The trustworthiness of the framework also depends heavily on the quality of expert input, which may vary across domains and contexts. Even though consensus-building strategies were integrated, biases and incomplete information can never be entirely eliminated. Furthermore, aggregation and weighting processes inevitably introduce simplifications that may mask nuanced individual judgments.

From a commercial perspective, additional challenges arise. Industrial applications often involve large and dynamic decision spaces, where criteria may interact in complex ways. The current framework assumes independence among criteria, which may not always hold in practice. Measurement inaccuracies may also stem from incomplete or rapidly changing data sources, especially in fields such as healthcare or telecommunications.

Finally, the transferability of the lessons learned in this work to other fields remains an open question. While the FST framework is conceptually general, domain-specific adaptations will be required to address unique challenges such as regulatory constraints, heterogeneous data formats, and real-time decision needs.

Breakthrough and industrial significance

The key breakthrough of this study lies in the integration of fuzzy sets, soft sets, and tensor structures into a unified decision-making framework. This novel formulation, which we term the Fuzzy Soft Tensor (FST), is capable of capturing uncertainty across multiple criteria, multiple alternatives, and multiple expert judgments simultaneously. Unlike existing multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) models, which often struggle with scalability or interpretability, the FST framework provides a mathematically transparent yet computationally efficient solution.

Who benefits?

-

Telecommunications industry: The proposed framework helps network operators and regulators select optimal wireless technologies under uncertain and conflicting expert evaluations. This ensures efficient spectrum allocation and infrastructure investment.

-

Smart infrastructure and IoT: Decision-makers in smart cities and IoT ecosystems can evaluate competing technologies (e.g., Wi-Fi 6 vs. 5G NR) more reliably, enabling robust urban planning and reduced risk of costly misinvestments.

-

Healthcare and supply chains: Beyond networking, the methodology can be adapted for medical diagnostics or logistics planning, where multiple experts and uncertain data are inherent.

Quantifying industrial importance

The economic significance of the proposed framework is particularly evident in the telecommunications sector. According to global forecasts, the investment in 5G deployment is expected to exceed USD 1.3 trillion by 2030. Even a modest improvement of 10–15% in technology selection and deployment efficiency achieved through a robust decision-making framework such as FST could result in potential savings of USD 130–195 billion worldwide. Moreover, avoiding misallocation of resources ensures not only financial gains but also improved quality of service and accelerated adoption of next-generation communication systems.

Summary

In summary, the breakthrough contribution of this study is the development of the FST framework, which simultaneously addresses uncertainty, heterogeneity, and expert conflict in group decision-making. Its industrial significance lies in reducing decision risks, improving resource allocation, and delivering measurable financial benefits across telecommunications, healthcare, and smart infrastructure sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed for this study are included in this article.

References

Zadeh, L. A. Fuzzy sets. Inform. Control 8(3), 338–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0019-9958(65)90241-X (1965).

Fan, Z. T. & Liu, D. F. On the power sequence of a fuzzy matrix-convergent power sequence. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 4, 147–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03011386 (1997).

Fan, Z. T. & Liu, D. F. On the oscillating power sequence of a fuzzy matrix. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 93, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fss.2011.01.009 (1998).

Biswas, R. Fuzzy subgroups and anti-fuzzy subgroups. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 35(1), 121–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0114(90)90025-2 (1990).

Chen, L. & Wang, F. Y. Anti-fuzzy semigroups and anti-fuzzy ideals of semigroups. Journal of Yunnan University, 36(3), 310-313. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.7540/j.ynu.20130632 (2014).

Chen, L. & Chen, Z. Decomposition theorem of fuzzy tensors and its applications. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 36, 575–581. https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-18911 (2019).

Chen, L. Decomposition theorem of Intuitionistic fuzzy tensors. J. Comput. Appl. Math. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40314-019-1000-8 (2020).

Atanassov, K. T. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 20(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0114(86)80034-3 (1986).

Yuan, X. H., Li, H. X. & Sun, K. B. The Cut sets, decomposition theorem and representation theorem on intuitionistic fuzzy sets and interval valued fuzzy sets. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 54(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40314-019-1000-8 (2011).

Muthuraji, T., Sriram, S. & Murugadas, P. Decomposition of intuitionistic fuzzy matrices. Fuzzy Inf. Eng. 8, 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fiae.2016.09.003 (2016).

Lee, H. Y. & Jeong, N. G. Canonical form of a transitive intuitionistic fuzzy matrices. Honam. Math. J. 27(4), 543–550 (2005).

Murugadas, P. & Lalitha, K. Decomposition of an intuitionistic fuzzy matrix using implication Operators. Fuzzy Math. Inform. 11(1), 11–18 (2016).

Yager, R. R. Pythagorean fuzzy subsets. In Proc. Joint IFSA World Congress and NAFIPS Annual Meeting, Edmonton, Canada, 24–28, pp.57–61. https://doi.org/10.1109/IFSA-NAFIPS.2013.6608375 (2013).

Zhang, H. M. & Xu, Z. S. Extension of TOPSIS to multiple criteria decision making with Pythagorean fuzzy sets. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 29(12), 1061–1078. https://doi.org/10.1002/int.21676 (2014).

Qi, L. Q. Eigenvalues of a real supersymmetric tensor. J. Symbolic Comput. 40, 1302–1324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.laa.2015.04.023 (2005).

Lim, L. H. Singular Values and eigenvalues of tensors: A Variational approach. Proc. IEEE Int. Workshop Comput. Adv. Multi-tensor Adaptive Process. 1, 129–132 (2005).

Hitchcock, F. L. The expression of a tensor or a polyadic as a sum of products. J. Math. Phys. 6, 164–189 (1927).

Hitchcock, F. L. Multiple invariants and generalized rank of p-way matrix or tensor. J. Math. Phys. 7, 39–79 (1927).

Tucker, L. R. Some mathematical notes on three mode factor analysis. Psychometrika 31, 279–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289464 (1966).

Oseledets, I. V., Savostianov, D. V. & Tyrtyshnikov, E. E. Tucker dimensionality reduction of three dimensional arrays in linear time. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 30(3), 939–956. https://doi.org/10.1137/060655894 (2008).

Harshman, R. A. Foundations of the PARAFACprocedure: Models and conditions for an “ explanatory’’ multi-model factor analysis. UCLA Working Papers Phonetics 16, 1–84 (1970).

Carroll, J. D. & Chang, J. J. Analysis of individual defferences in multidimensional scaling via an N-way generalization of “Eckart-Young’’ decomposition. Psychometrika 35, 283–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310791 (1970).

Kiers, H. A. Towards a standardized notation and terminology in multiway analysis. J. Chemometrics 14, 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-128X(200005/06)14 (2000).

Lathauwer, L. D. E., Moor, B. D. E. & Vandwalle, J. A Multilinear singular value decomposition. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 21, 1253–1278 (2000).

Kolda, T. G. & Bader, B. W. Tensor decompositions and applications. SIAM Rev. 51, 445–500 (2009).

Oseledets, I. V. Tensor-train decomposition. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 33(5), 2295–2317. https://doi.org/10.1137/09075228 (2011).

Oseledets, I. V. & Tyrtyshinkov, E. E. Breaking the curse of dimensionality, or how to use svd in many dimensions. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 31(5), 3744–3759. https://doi.org/10.1137/090748330 (2009).

Ragnarsson, S. & Loan, C. F. Block tensor unfoldings. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. abd Appl. 33(1), 149–169. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1101.2005 (2012).

Mousavi, S. M. et al. An extended multi-attribute group decision approach for selection of outsourcing services activities for information technology under risks. Int. J. Appl. Decision Sci. 12(3), 227–241 (2019).

Gitinavard, H. et al. Strategic evaluation of sustainable projects based on hybrid group decision analysis with incomplete information. J. Qual. Eng. Production Optimization 4(2), 17–30 (2019).

Gitinavard, H. et al. Project safety evaluation by a new soft computing approach-based last aggregation hesitant fuzzy COPRAS in construction industry. Scientia Iranica 27(2), 983–1000 (2020).

Gitinavard, Hosein et al. A new decision making method based on hesitant fuzzy preference selection index for contractor selection in construction industry. Ind. Manag. Studies 15(45), 121–144 (2017).

Borujeni, M. P., Behzadipour, A. & Gitinavard, H. A dynamic intuitionistic fuzzy group decision analysis for sustainability risk assessment in surface mining operation projects. J. Sustain. Mining 24(1), 15–31 (2025).

Gitinavard, H., Ghaderi, H. & Pishvaee, M. S. Green supplier evaluation in manufacturing systems: A novel interval-valued hesitant fuzzy group outranking approach. Soft Computing 22(19), 6441–6460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-017-2697-1 (2018).

Salvador, G., et al. ELECTRE applied in supplier selection – a literature review. Procedia Computer Science (2024). (Survey situating IVHF outranking in supplier selection.)

Görçün, Ö. F., Pamucar, D. & Küçükönder, H. Selection of tramcars for sustainable urban transportation by using the modified WASPAS approach based on Heronian operators. Appl. Soft Comput. 151, 111127 (2024).

Arshad, M. W., Sintaro, S., Rahmanto, Y. & Wantoro, A. Optimization of alternative assessment with modified MOORA method: Case study of contract employee selection. KLIK Kajian Ilmiah Informatika dan Komputer 4(6), 3099–3107 (2024).

Abdullah, S., Ullah, I. & Khan, F. Analyzing the deep learning techniques based on three way decision under double hierarchy linguistic information and application. IEEE Access (2023).

Abdullah, S., Almagrabi, A. O. & Ullah, I. A new approach to artificial intelligent based three-way decision making and analyzing S-Box image encryption using TOPSIS method. Mathematics 11(6), 1559 (2023).

Xie, B. Modified GRA methodology for MADM under triangular fuzzy neutrosophic sets and applications to blended teaching effect evaluation of college English courses. Soft Computing, 1-12 (2023).

Zhang, X. & Xu, Z. Extension of TOPSIS to multiple criteria decision making with Pythagorean fuzzy sets. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 29(12), 1061–1078 (2014).

Liang, D., Xu, Z. & Liu, D. Method for three-way decisions using ideal TOPSIS solutions at Pythagorean fuzzy information. Inform. Sci. 435, 282–295 (2018).

Jinqiu, Li., Wei, Chen, Zaoli, Yang & Chuanyun, Li. A time-preference and VIKOR-based dynamic intuitionistic fuzzy decision-making method. Filomat. 32(5), 1523–1533 (2018).

Molodtsov, D. Soft set theory—First results. Comput. Math. Appl. 37 (4–5), 19–31 (1999).

Maji, P. K., Biswas, R., & Roy, A. R. Fuzzy Soft Sets. J. Fuzzy Math. 9 (3), 589–602 (2001).

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information