Abstract

The digital transaction ecosystem presents a critical problem involving financial fraud detection and, on the verge, requires advanced computational techniques to distinguish between legitimate and fraudulent activities. To close the gap in available robust fraud detection methodologies, this study utilizes the Synthetic Financial Datasets provided by Kaggle, a collection of synthetic 6 million transactions that include a rich data benchmark generated by PaySim’s top-notch synthetic data generation process. It presents the Risk Adaptive Bayesian Ensemble Model (RABEM), a new system that combines various advanced methods, including Black-Scholes Feature Engineering, Hybrid VAE, Nyström Approximation Gaussian Process, Random Projection Tree (RPTree), and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) and Bayesian Reliability Fusion to provide improved accuracy and dependability of fraud detection. Furthermore, the RABEM methodology proposed is demonstrated to deliver excellent performance on various evaluation metrics, achieving a high accuracy of 99.38%, which outperforms other approaches. The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) value of 0.9788, low Brier Score of 0.0061, and log loss of 0.2103 are key performance indicators. The top-K hit rate analysis demonstrates the model’s reasonable ability to identify fraud, as it correctly identifies 972 out of 1000 fraudulent transactions with a precision of 0.972. Future work will focus on working with a large set of related data and all other ensemble methods, and creating more effective strategies for selecting essential features to improve fraud detection accuracy and speed in complex financial transactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the field of finance and business, fraud detection remains a significant challenge as organizations are still wrestling with the growing threat of fraud activities that cause substantial financial loss and damage to the reputation of the organization1. According to the 2023 report published by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), global losses due to fraud amount to nearly $5.6 trillion annually, with the average organization losing approximately 5% of its revenue to fraud2,3. Modern fraudsters are becoming increasingly sophisticated, and the tremendous volume of financial transactions makes traditional methods of detecting fraud less effective4. Therefore, the need for more sophisticated and adaptive fraud detection systems has arisen. By far, Machine Learning (ML) and the Bayesian models are probably among the techniques employed most effectively to detect fraudulent activities in massive datasets5. Indeed, Bayesian ensemble models are starting to gain popularity, as they represent a promising solution to the problem of uncertainty, of coping with dynamic environments of risk, and of improving the model’s prediction accuracy6.

In this context, a Risk-Adaptive Bayesian Ensemble Model for forecasting fraud among clients can be an innovative approach by combining the strengths of Bayesian methods and ensemble learning. Fraud detection is particularly amenable to Bayesian methods because the data in a fraud case inherently has uncertainty, and each observation has some associated probability6,7. The model can integrate risk-adaptive mechanisms that allow the detection system to be more dynamic and flexible, depending on the varying fraud risk. The ensemble aspect of the model involves combining multiple models to make performance better by lowering bias and variance, which is imperative for dealing with such imbalanced datasets as are commonly encountered in fraud detection7,8. In this study, we take a more comprehensive approach to analyze such a model, showing its promise to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of fraud detection systems in financial domains. At the same time, we also pinpoint the downsides of this modeling approach. Furthermore, among the most significant issues in fraud recognition is the highly imbalanced nature of fraud datasets that can be applied. Fraudulent transactions are far more unusual than legitimate ones3,8. The example shown above of over 10,000 legitimate transactions being present versus fewer than 100 fraudulent transactions can result in class imbalance; traditional classifiers can begin predicting all transactions as legitimate (the minority class) as opposed to identifying just a few as fraudulent (the majority class)8,9. The solution has been to use increasingly sophisticated datasets created to mimic real-life financial fraud situations. The Paysim and Synthetic Financial Datasets for Fraud Detection datasets are two widely used datasets in this field that can be downloaded from Kaggle. Likewise, the Paysim dataset is a mobile payment transaction simulation dataset, where transactions are categorized as legitimate or fraudulent. It contains over 6 million records and addresses the challenge of detecting real-world mobile payment fraud.

Similarly, Kaggle’s Synthetic Financial Datasets for Fraud Detection also serve as a valuable resource for training and evaluating fraud detection algorithms10. We have a synthetic, data-driven version, featuring transaction records with various characteristics, including transaction amounts, time, merchant information, and user demographics. This consists of over 100 million transactions and a fraud rate of approximately 0.5%, making it an ideal benchmark for evaluating a fraud detection model’s performance. These datasets provide significant sources of diverse and representative data that represent the complexities of detecting fraud in financial transactions, which are both essential for facilitating the development of strong fraud detection systems11,12. These datasets enable practitioners and researchers to train their models in a stable environment before deploying them on live systems. In addition, to be successful, fraud detection models are highly data-driven on which they are trained12,13. For this study, we will test the risk-adaptive Bayesian Ensemble Model on the Paysim dataset and synthetic financial datasets for Fraud Detection. The datasets offered to test the robustness and adaptability of the proposed model are diverse in terms of features and possess real-world characteristics, including class imbalance, noise, and varying transaction patterns, which are common in real-world datasets. Bayesian inference will be used to estimate the probability of fraud on a transaction-by-transaction basis, and the model will adjust its predictions based on the risk level deduced from historical data14. The ensemble will comprise multiple predictive models, such as decision trees, logistic regression, and support vector machines, and combine them to form a more robust and dependable detector based on the strengths of each model.

Furthermore, the Bayesian framework can incorporate risk-adaptive mechanisms that better address the varying risk levels associated with certain transaction types. This model, for example, can learn to focus more scrutiny on transactions with higher values, as such transactions are more prone to evolving into fraudulent ones. This adaptability enables the timely applicability of the model, which can continue to develop and refine its fraud detection capabilities as new data and insights into fraud emerge. As a more flexible, adaptive, and scalable solution for financial institutions and businesses, the proposed model aims to achieve a significant technological improvement over traditional static fraud detection systems.

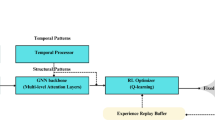

As shown in Fig. 1, a risk-adaptive Bayesian ensemble model is developed by combining several classifiers that dynamically adjust to the risk level to improve the accuracy of fraud detection decisions.

The following are the contributions of the study:

-

i.

Innovative hybrid model: The study details the novel hybrid model RABEM Fraud, which combines financial risk theory with deep learning and Bayesian fusion to achieve robust fraud detection.

-

ii.

Risk-based features: Risk-based features extracted from the Black-Scholes model enhance the transaction representations beyond the conventional inputs.

-

iii.

Techniques for Scalable and efficient learning: The model employs Nyström Gaussian processes with mini-batch stochastic gradient descent (SGD) to achieve high scalability and computational efficiency on large, imbalanced datasets.

-

iv.

Temporal fraud adaptability: GRU captures evolving fraud trends by analyzing sequential transaction behavior and develops adaptive fraud detection capabilities over time.

-

v.

Bayesian reliability fusion: The Bayesian reliability fusion method dynamically weights model outputs according to prediction history and entropy to maximize accuracy and minimize false negatives.

In brief, the increasing scale and complexity of financial transactions necessitate even more sophisticated and responsive fraud detection mechanisms. This research presents the Risk-Adaptive Bayesian Ensemble Model, a promising approach that combines Bayesian inference, ensemble learning, and risk-adaptive mechanisms. Through large-scale datasets, such as Paysim and the Synthetic Financial dataset, this study aims to provide insight into how these models can effectively operate in real-world fraud detection scenarios. This model will help achieve higher accuracy and fewer false positives and will be adaptable to fraud techniques, serving as a key point of defense against fraud for financial institutions and their customers.

This study is structured as follows: “Related work” reviews the literature on previous work relevant to the topic; “Dataset overview” describes the dataset used during the research; and “Methodology” outlines the methodology. “Results” presents the results and analysis, which are discussed and interpreted in the context of the findings presented in “Discussion”. Finally, “Conclusion” concludes the study with the main conclusions.

Problem statement

Financial transaction fraud detection remains a challenging and intricate problem, as fraudsters continually invent and implement new tactics rapidly. There are relatively few fraudulent transactions compared to legitimate ones, and scalable solutions that can run on massive datasets in real-time are necessary. However, these challenges are particularly challenging for traditional machine learning models, such as logistic regression and gradient boosting. On the other hand, they are limited in their capabilities to address high-class distribution skewness, the continuous evolution of new fraud trends, and maintaining computational efficiency in problems related to large-scale financial systems. As a result, these shortcomings lead to high false negative rates and low adaptability, resulting in substantial economic and reputational losses for financial institutions. Additionally, several existing models lack interpretability and robustness, which are crucial for informed decision-making in high-risk financial environments.

The proposed study presents the Risk-Adaptable Bayesian Ensemble Model for Fraud Detection (RABEM Fraud) to overcome these shortcomings. This novel hybrid approach combines financial risk modeling, deep learning, and probabilistic ensemble methods. This work then presents a model that leverages advanced techniques, such as Black-Scholes feature engineering, hybrid variational autoencoders, Nyström approximation of scalable Gaussian processes, and GRU-based sequence modeling, along with Bayesian reliability fusion, to create an integrated and adaptive fraud detection framework. With the addition of these components, RABEM Fraud gives feature representation with anomaly detection and offers temporal adaptability and real-time scalability. The robust ensemble design of the model enables it to intelligently fuse the strengths of its components based on historical reliability, thereby reducing model drift and improving accuracy. Finally, it is evaluated on one of the most highly imbalanced real-world datasets and performs better than conventional models. Thus, the performance of the proposed model on the imbalanced dataset is promising for the solution of the modern fraud detection problem in large and dynamic financial environments.

Related work

Due to the popularity of digital payment systems, demand for effective fraud detection solutions has dramatically increased as the complexity of financial transactions has increased. The conventional patterns of fraud detection, being quite helpful, however, fail to adapt to the dynamic patterns of fraud. In recent years, much attention has been focused on enhancing fraud detection through ensemble-based learning, anomaly detection, Bayesian approaches under high prevalence cases, and managing imbalanced datasets. New technologies emphasize explainable machine learning (ML) and federated learning as having the potential to develop honest and transparent banking fraud detection systems12. Furthermore, built-in machine learning models within the real-time trapping systems in online marketplaces have been efficient in fighting the realistic bidding behaviors in the online marketplaces13. On the same note, the application of ML in supply chain partnerships has promoted decision-making and operational resilience14. Also, the behavior of the people who use online banking is vital in improving the preparedness of cyberspace, which highlights the significance of the human aspect in preventing fraud cases15.

Early innovations to improve fraud detection frameworks have focused on blockchain-integrated approaches, such as those of Pranto et al.16 developed a hybrid model that utilizes blockchain technology and incremental machine learning to address data integrity and adaptive learning. However, their model achieved an accuracy of 98.93% and F-beta scores of 98.22%, yet limitations in scalability and a lack of privacy compliance were highlighted by challenges such as mining complexity and sensitivity to data volume. While this method provided a solid foundation for secure and adaptive fraud detection, it may not be suitable for all financial systems based on blockchain infrastructure due to its associated overhead costs. On the other hand, purely machine learning-based methods have recently become popular because they are versatile and practical. Maged et al.17, a comparative study of 12 ML algorithms is conducted over three online payment datasets. The others did not compare favorably to gradient boosting, whose performance is said to have reached 96.8%. However, the model was limited in its generalizability due to dataset diversity and scalability considerations. It highlights the importance of utilizing high-performance elastic models to accommodate varying data volumes and types. To this end, Fu18 also applied a stacking ensemble to the same synthetic large financial dataset, using logistic regression, SVM, and other methods. However, their methodology, which included sampling strategies, reported a 97% recall but only 87% accuracy; there was tension in determining how much actual fraud they detected versus how many false alarms they generated. In addition, there was a need to validate fraud detection system models on actual, noisy datasets, as synthetic data raised questions about whether the model would be effective in real-world settings.

The fraud classification problem may be well-supported by ensemble techniques, as soft and weighted averaging methods have been shown to perform effectively. Sahithi et al.19 presented an ensemble or weighted average model, which achieved 99% accuracy in credit card transaction data. However, concerns exist regarding robustness: on the one hand, it is possible to overfit the data, and on the other hand, there is no real-world deployment testing, which is necessary for robustness. This problem was tackled by Gupta et al.4, who coupled XGBoost with oversampling methods to handle the issue of class imbalance. Their study found that oversampling significantly increased model precision and accuracy to 99%, indicating that to detect fraud effectively, the strategies employed need to be balanced. Bayesian frameworks are gaining recognition as they are further developed to improve model optimization, as seen in the work of Lim et al.20, they used a Bayesian optimization-driven Extremely Randomized Trees approach, achieving a precision of 0.97 and an F1 score of 0.95. This model was effective on real-world transaction data; however, the complex algorithm, combined with the nature of fraud, results in imbalanced data, making it still prone to overfitting. However, it paved the way for combining probabilistic reasoning with ensemble classifiers to enhance adaptive learning. Second, alternative research carried out by Sorin et al.21 used the Random Forest algorithm merged with SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Oversampling) and entropy-based splitting. The other direction labeled it as commendable precision (0.95) but with a recall rate of 0.79, which means that a significant fraction of fraudulent activities escaped detection. This is a substantial limitation of traditional tree-based ensemble models when the data distribution is sufficiently imbalanced.

However, it has also given rise to the emergence of various unsupervised learning approaches that promise to be viable alternatives. Jiang et al. used attack pattern detection networks with attentional anomaly detection and GANs22. To discover fictitious patterns without labeled data. Although their method achieved high precision (0.9795), its recall (0.7553) fell short of the medium recall level. Attention mechanisms are used to make fraud occurrences adaptive to changing fraud signatures. However, low recall suggests that rare fraud events may not be fully detected. Additionally, new, sophisticated strategies are enabling ensemble models to evolve. Cyber threat classification in financial transactions based on a stacking ensemble was suggested by Alhashmi et al.23. The high accuracy achieved by their model, at 0.98, created limitations for real-time deployment, highlighting the importance of a viable model for operation rather than solely for performance. Similarly, Arief et al.24 I also attempted to optimize Naive Bayes using SMOTE-Tomek with class imbalance correction to achieve an accuracy of 0.97 and an AUC of 0.92. Though the F1-score was very low at 0.11, it revealed that performance is not good if distribution and noise in the data are not considered. Mimusa Azim et al.25, finally proposed a soft voting ensemble model that combined sampling techniques and effectively used misclassification costs in imbalanced datasets. Finally, they presented results with a precision of 0.987 and a recall of 0.969, demonstrating a balanced and efficient detection system with residual imbalance-related issues. Additionally, several trends are visible across the views presented in this paper. Stacking and soft voting on ensemble methods have a high potential for overcoming fraud detection challenges and can be combined with sampling techniques and Bayesian optimization. Nevertheless, the problems of overfitting, lack of deployment in the real world, and imbalanced data remain.

Considering these limitations, a potential solution exists in the form of a Risk-Adaptive Bayesian Ensemble Model. Such a model would enable the integration of adaptability from Bayesian optimization, robustness from ensemble learning, and dynamic risk assessment for both precision and recall. This proposed approach aims to address this gap by leveraging the strengths and weaknesses of existing studies to bridge the gap between theoretical model performance and the evolving practical needs of fraud detection.

Table 1 lists related works, including datasets, methodology, limitations, and results.

The literature study has critically examined the different frameworks of fraud detection, including blockchain-integrated systems, machine learning-based frameworks, ensemble methods, Bayesian optimization, and unsupervised techniques. Existing blockchain methods16 achieve very high levels of security but lack scalability and compliance with privacy regulations, whereas machine learning-based methods17,18 have good accuracy but lack generalizability and depend on synthetic data. Ensemble, e.g., stacking19 or weighted averaging4 approaches seem to show potential in improving performance, yet these techniques tend to overfit, and many have not been validated in the real world. Bayesian optimization20 is also adaptive and more accurate at the cost of class imbalance. Recent hybrid models22,25 or models that are based on unlabeled data23,24 are focused on identifying unlabeled or rare cases of fraud. However, their recall is still too low, and their robust operation in practice is usually not tested.

This range of literature also exhibits a common challenge: despite the effectiveness of these models, they often cannot be adopted into adaptive practical fraud detection systems because they lack scalability, agility, and responsiveness to changing fraud behaviors. This study fills the gap mentioned above by proposing to use the potential of ensemble learning, Bayesian adaptivity, and dynamic risk assessment in its Risk-Adaptive Bayesian Ensemble Model. It will reduce the chances of overfitting, generically better handle imbalanced data, and offer a model that is both useful in terms of performance and practical in terms of deployment in fraud detection, which closes a gap between theory and practice.

Dataset overview

Here, the Synthetic Financial Datasets for Fraud Detection, from Kaggle, is a large-scale benchmark dataset for financial fraud detection and consists of 6 million transactions20,26. However, the dataset is highly imbalanced: the majority class, which in this case is non-fraudulent, comprises a large portion of the data, and traditional classification models that do not incorporate additional strategies often face the issue of overfitting to the majority class. The features include transaction metadata, sender and receiver details, transaction amount, and contextual attributes contributing to the fraud risk assessment. The dataset contains some of the following challenges:

-

Imbalanced data: Fraudulent transactions have been prevalent, resulting in more fraudulent transactions than non-fraudulent transactions. This causes the model to learn that fraudulent transactions are absent in most of the data.

-

Restricted to high-dimensional feature space: The dataset contains multiple sparse and correlated features, making it challenging to extract meaningful patterns.

-

Fraud patterns evolve: Fraudsters continually adjust their tactics over time, necessitating the adaptation of fraud models to new behaviors.

-

Scalability issues: Since we are dealing with millions of transactions, efficient feature engineering and model selection are necessary for computational feasibility.

Real-world financial transaction data is very limited in availability due to strict privacy requirements, such as GDPR, PCI DSS compliance, and laws on banking secrets, which prohibit releasing raw transaction datasets with personally identifiable information (PII). Even anonymized datasets can be re-identified, and much financial data is proprietary, siloed within organizations, and may involve non-disclosure agreements or require institutional affiliation to a particular organization. This objection introduces several problems since independent researchers are not in a position to benchmark the fraud detection models in a live environment. We therefore used synthetic data sets such as PaySim, which are statistically representative of the real-world distributions of fraud and thus allow reproducibility and open access to future studies.

The artificial data adopted in the current research design contains structural patterns of transactions that are likely to be fraudulent and have been verified by previous studies as a plausible proxy for the real banking environment. We added mechanisms such as Variational Autoencoders (VAE) to learn typical transaction patterns and made the model robust to data corruption or missing values. Moreover, the Nystrom-approximated Gaussian Process (GPC) incorporates uncertainty modeling to process noisy data, while the GRU-based temporal module tracks drifting fraud trends, making the model flexible to data drift. Moreover, the Bayesian Reliability Fusion mechanism assists in assigning weights to less reliable models, especially where there are unknown data distributions.

While the synthetic dataset (PaySim Kaggle dataset) employed here may not represent real-world characteristics completely, by representing the degree of randomness and the discontinuity of the collected data, it is structured in a realistic enough way to perform this demonstration. In the real world, fraud depends on invisible contextual variables such as device fingerprints, merchant trustworthiness, network-level interactions, and other variables that can’t be accurately simulated through synthetic data. This leads to a potential risk of optimistic results, which can be linked to the deployment of these services into the financial production environments. Limited utility of synthetic data: Synthetic data can be efficient as they can approximate real data; however, there are inherent limitations to using them, since they eliminate behaviour, contextual, and operational noises which exist in reality for financial systems. And from a fraud perspective, it is often the unusual transaction or the low number of transactions that’s the key to exposing fraudulent activity; the data can reveal subtle indicators of collusion like device discrepancies, merchant reputation, cross-channel multiplicity, slowdown settlements, and time-varying adversary tactics. Conventional generative adversarial learner(s), on the other hand, model fraud as stationary statistics, not capable of illustrating where the fraudster is highly non-stationary, irregular, or adversarial adaptive. Furthermore, synthetic data tends to be clean and complete, devoid of the missing values, data corruption, delayed timestamps, and functionality issues that are imposed upon financial institutions every day. This can give inflated performance metrics, as models are scored under ideal, not practical conditions, like refugees having printable documents. Finally, there may be a gap between the causal processes hypothesized by the theory and the experimental data: the synthetic datasets used (in contrast to real-world systems) may not accurately capture the regulatory, cultural, and institutional diversity of global financial systems, impacting the external validity and generalizability of results. Therefore, while synthetic benchmarks are essential for reproducible evaluation in controlled environments, they cannot fully replace evaluation on real and evolving streams of financial transactions, which are noisy and of a complex nature, and where fraud detection models must eventually be applied.

Moreover, the PaySim dataset, based on logs of a mobile money service in a country in Africa, is helpful to simulate mobile money transactions, although synthetic. The proposed method maintains the viability of scientific benchmarking in the face of the difficulties of accessing real-time data on fraud detection. To generate concept drift, we took control over the label flipping. We monitored the distributional shifts using ADWIN, simulating the way the model would work with a growing fraud strategy in practice. Such a controlled design is a compromise between scientific methodology and realistic applicability that can be extended later to real data when chords of institutional accessibility and compliance are addressed.

The Synthetic Financial Datasets for Fraud Detection were developed to create financial transactions that resemble real-world transactions while preserving privacy and confidentiality27. The dataset is created with the same structure as accurate banking transaction logs to maintain, as much as possible, the statistical properties of real financial data. Multiple types of transactions are present (cash out, transfer, and payments). A transaction comprises multiple features: amount, transaction type, origin and destination accounts, and balance before and after the transaction of both origin and destination accounts. Figure 2 presents an example of the dataset structure.

Feature engineering

To detect fraud effectively, feature extraction from these transactions should yield meaningful results, that is, the ability to distinguish between fraudulent and non-fraudulent transactions. We combine domain knowledge with statistical transformations to enhance the machine learning model’s detection capability. The following are some basic engineered features.

-

Different transaction modes: The dataset contains a categorical feature type with values CASH_IN, CASH_OUT, DEBIT, PAYMENT, and TRANSFER, representing various transaction modes. Categorical values are transformed into integers using Label Encoding.

-

The black-scholes option pricing model incorporates financial risk assessment into fraud detection, a process typically employed to evaluate the value of financial derivatives. It is adapted in this context to estimate the fraud risk probability associated with the transaction using this model. Equation 1 below gives the Black-Scholes formulation.

where,

-

S represents the initial account balance (oldbalanceOrg),

-

K is the transaction amount (amount),

-

T is the time horizon (set to 1 in this study),

-

r is the risk-free interest rate (assumed to be 5%),

-

σ is the estimated volatility (assumed to be 30%),

-

N(x) is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution.

The fraud risk probability is calculated for each transaction, providing an additional risk-sensitive feature as shown in Eq. (2) below:

This risk-aware functionality expresses the probability of a transaction being fraudulent according to the principles of financial uncertainty. The usage of the Black-Scholes model in our fraud detection system does not aim to represent a direct pricing instrument of financial options, but a risk-sensitive proxy element that tracks volatility-like behavior of the transactions. Audacities that focus on high-value or high-risk transfers are prone to fraudulent conduct, especially where transactions are prone to unstable monetary gain, and the exposure to sudden monetary losses. We adapt the Black-Scholes formula to reflect the following: the amount of transaction is the “underlying asset,” the time-to-settlement or gap of time before issuing a transaction is the “maturity,” and the variability in historical behavior of users is the “volatility.” This incorporated integration offers a structured and finance-based mechanism to measure the uncertainty and risk of the transaction patterns entrenched at user levels thereof. We do not take this simply as a theoretical construct independent of other characteristics, but incorporate the Black-Scholes-derived risk score together with Behavioural characteristics and time characteristics as part of the learning pipeline. Such an incorporation enriches the feature space by adding a domain-emulated risk aspect so that the model can juggle better between benign high-value transfers and abnormal volatility-intensive trends. Although empirical standards show that predictive lift is low, relative to core behavioral characteristics, this incorporation makes sense, correlating the propensity to commit fraud with better-known legal ideas of financial risks.

-

Usually, a sudden drop in account balances is associated with fraudulent transactions. Account depletion patterns are captured by the balance difference before and after each transaction, which could be used to identify a fraudulent transaction due to a significant balance reduction.

-

One of the best fraud indicators is the relationship between the transaction amount and the sender’s balance. In Eq. (3), the risk score is defined.

The denominator ensures numerical stability by preventing division by zero. Since extreme values may bias the model, we normalize the risk score using min (risk_score,1); thereby, this bounded risk score prevents outlier transactions from disproportionately influencing the model.

-

To further refine fraud prediction, a Bayesian fraud probability is computed using a Beta cumulative distribution function (CDF) as shown in Eq. (4) below.

If a = 2 and b = 5 are shape parameters chosen to represent the assumption that fraudulent transactions are comparatively rare, then. It focuses on high-risk transactions to improve separability between fraudulent and non-fraudulent ones.

-

Sampling strategy for class balance: Due to the severely imbalanced nature of the dataset (where fraudulent transactions form a tiny portion of the total transactions), a controlled downsampling strategy removes all but a fraction of the latest legitimate transactions, providing the model with the opportunity to learn actual fraud patterns. By controlled sampling, the transactions are sufficiently representative of fraud while showing some recency.

-

Standardization and feature selection: Numerical features are standardized using z-score normalization, ensuring the features are on a standard scale during training. As shown by Eq. (5), feature selection using ANOVA F-test-based choices reduces dimensionality while retaining essential variables.

where features with the highest F-scores are retained for training.

The original dataset sourced through Kaggle has about 0.13% cases of fraud, and as such, is very imbalanced and will require normal models to learn anything insightful regarding fraud. On the training data, we did naive controlled random downsampling of the majority before fitting the majority class only to a ratio of about 1:5 (fraud: legit) to preserve some class skew and aid training dynamics. It was decided to use downsampling instead of oversampling because the instances of fraud are synthetic and, therefore, synthetic oversampling (e.g., SMOTE) appeared much less significant, and to prevent overfitting to replicated or interpolated cases of fraud. Downsampling enhanced model training stability and convergence, especially the VAE and GRU components, and yet supported a wide variety of fraud exposure.

Exploratory data analysis of the dataset

The exploratory data analysis reveals significant patterns in the transaction dataset that distinguish between normal and fraudulent activities. The class distribution, as illustrated in Fig. 3, demonstrates the imbalanced nature of the dataset before and after downsampling, with fraudulent transactions representing a minority class compared to normal transactions.

Table 2 provides a statistical summary highlighting the substantial difference in transaction amounts between normal and fraudulent cases. Normal transactions (labeled as 0) have a mean value of 129,018 with a standard deviation of $ 180,775, while fraudulent transactions (labeled as 1) exhibit a significantly higher mean of $ 1,467,967 with a standard deviation of $ 2,404,253. This nearly tenfold difference in average transaction amounts suggests that transaction size is a potential indicator of fraudulent activity. The range for normal transactions spans from 0 to 3,527,322, whereas the range for fraudulent transactions spans from an unspecified minimum to a maximum of 10,000,000. The quartile values further emphasize this distinction, with the median (50th percentile) for fraudulent transactions (441,423) being approximately seven times higher than that of regular transactions (63,990).

The application of the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to transaction amounts, as displayed in Fig. 4, reveals hidden periodicities and frequency-domain patterns associated with fraudulent activities28. The dominant frequency components visible in the plot suggest underlying cyclical behaviors in transaction values that may correspond to automated or scheduled fraudulent activities29. These distinctive peaks represent temporal patterns that could significantly enhance fraud detection models by incorporating frequency-domain features.

The transaction amount histogram presented in Fig. 5 further supports these findings by displaying a highly skewed distribution with a long tail extending toward higher values30. The calculated skewness of 6.5 confirms that while most transactions involve smaller amounts, fraudulent activities often manifest as unusually high-value outliers.

Additionally, the high kurtosis value of 46.86 indicates a leptokurtic distribution characterized by extreme outliers that likely correspond to fraud cases31,32. This distribution reinforces the observation that transaction amount is a critical differentiating factor between legitimate and fraudulent activities, underscoring the importance of incorporating outlier detection techniques in fraud classification models.

Methodology

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the proposed fraud detection method is a sophisticated hybrid approach comprising various complementary machine learning components. A Hybrid Variational Autoencoder first emphasizes learning the latent representation. Raw transaction data is transformed into a lower-dimensional vector using latent variable representation while preserving part of the information. Three parallel streams then process this extracted feature set: first, a Nyström approximation-based Gaussian Process classifier that provides probabilistic fraud assessments; second, an RPTree classifier that learns the non-linear decision boundaries; and finally, a GRU network that learns temporal transaction patterns and sequential dependencies.

A Bayesian reliability assessment evaluates the prediction confidence across different model components within the system. An entropy-based confidence scoring mechanism provides a more quantifiable measure of uncertainty in the fraud predictions. The weighted fusion of forecasts from the most reliable components enables dynamic adaptation to various fraud scenarios, ultimately determining the outcome. The ensemble approach leverages the strengths of each constituent. It mitigates the weaknesses of the individual contingent, thereby constructing a robust fraud detection system capable of detecting complex yet evolving fraud patterns.

-

(1)

Hybrid variational autoencoder for feature extraction: Our feature extraction process is based on the Hybrid Variational Autoencoder (VAE), and the structure is shown in Fig. 7, which takes in high-dimensional transaction data and transforms it into an information-dense latent representation33,34. Influenced by the encoder, it maps input transactions to a probabilistic latent space, where every data point is represented as a distribution rather than a fixed vector. Through the Kullback–Leibler divergence loss, the latent space is regularized to encourage the separation of the fraud patterns and exhibit a structured organization. It is hybrid in that, unlike traditional autoencoders, we can reconstruct from the perspective of VAEs, which can capture subtle fraud indicators while maintaining a compact representation34. To preserve the characteristics of transactions crucial to fraud detection, the latent space must not change significantly from the decoder component’s reconstruction of the original input. Furthermore, this conveniently reduces dimensionality and disentangles the pattern of the complex frauds, hence making them easier to separate by the downstream classification modules35.

(Adapted from4).

Hybrid VAE.

It has an encoder—latent Space with a reparameterization trick and a decoder architecture. The encoder is a function that maps an input transaction feature vector x of dimension d into an encoded representation z of much lower dimensionality. Multiple dense layers: The first layer consists of 32 neurons with ReLU activation, and the second dense layer comprises 16 neurons, further reducing the dimensions. The encoder produces two separate outputs, the mean vector, \(\:{\text{z}}_{{\upmu\:}}\)and log variance vector, \(\:{\text{z}}_{{\text{log}{\upsigma\:}}^{2}}\). These outputs define a multivariate Gaussian distribution from which latent variables are sampled. Since VAEs involve sampling from a probability distribution, direct sampling is non-differentiable. To enable gradient-based optimization, the reparameterization trick is employed, where a random variable, \(\:\in\:\sim\text{N}\left(\text{0,1}\right)\) is introduced. The model can learn a differentiable latent space representation due to this transformation. From variable z, the decoder reconstructs the original input x. This is the first layer of 16 neurons that expands from z to 16 neurons, the second layer expands further to 32 neurons, and the output layer, with 16 neurons, is an activation layer that reconstitutes the input dimensionally and clamps the range of values between 0 and 1. The VAE loss function consists of the KL Divergence loss by multiplying it with β and the Mean Squared Error as the final reconstruction loss, respectively, with which β controls the balance between reconstruction accuracy and latent space regularization34,35. The feature inputs for subsequent classification models are encoded representations. The learned latent variables, z, correspond to complex fraud-related structures and help significantly improve classifier performance.

-

(2)

Scalable Nyström approximation-based Gaussian process: Gaussian Process Classification (GPC) is a powerful non-parametric Bayesian approach that provides probabilistic fraud detection with uncertainty quantification. However, its computational complexity scales as O(N2) in training and O(N2) in inference, making it impractical for large datasets35. Traditional kernel methods require storing and inverting large covariance matrices, leading to memory inefficiency and excessive computation time. To mitigate these challenges, the Nyström approximation is used, a technique that constructs a low-rank approximation of the RBF kernel by selecting a representative subset of training points. This method reduces both memory requirements and computational cost while preserving the functional characteristics of full Gaussian Process models. The Nyström method approximates the original kernel matrix K by selecting m landmark points (where m ≪ N) and computing a low-rank approximation of the form shown in Eq. (6) below.

where:

-

\(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{N},\text{m}}\:\)represents the similarity between all data points and the selected subset.

-

\(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{m},\text{m}}\) represents the similarity between the selected subset itself.

-

\(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{m},\text{N}\:}\)is the transpose of \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{N},\text{m}}\).

To address problems of nonlinear classification, such as fraud detection, the Nyström approximation of the RBF kernel is employed. To enable scalability, large datasets are reduced to a maximum of 100 representative points, thereby avoiding computational overload. The Nyström method minimizes the memory required for all data transformations by computing a low-rank approximation of the RBF kernel, thereby reducing the training and testing data in a reduced feature space and then converting it into a sparse format. Then, dimensionality reduction is followed with the use of a Mini-Batch Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) classifier and elastic net regularization for better performance35,36. Since it generates a probabilistic output, binary fraud classification is performed using the log-loss function. To address the inherent imbalance of classes in fraud, class balancing techniques are employed. The Elastic net not only includes L1 and L2 terms, but it also promotes sparsity, thereby inhibiting overfitting, while L2 terms help to generalize and stabilize the weights. The regularization is done with a balanced approach by using an elastic-net mixing parameter (l1-ratio = 0.15). In mini-batch SGD, gradients are computed from a small, randomly selected subset of data, and then each iteration updates the model’s parameters. This training strategy reduces memory consumption and scales well with large datasets. Some of the iterative optimization process in mini-batch training is illustrated in Fig. 8.

(Adapted from35).

Mini-batch SGD.

The model is trained with 1000 iterations with class imbalance handling and a tolerance criterion of 0.0001, which determines when the model should stop training if the improvement in the objective function (log loss in this case) becomes too small. The predictions are obtained from the trained classifier.

-

(3)

Random projection tree: The Random Projection Tree (RPTree) classifier is a non-parametric, tree-based model designed explicitly for high-dimensional data, making it well-suited for fraud detection. This differs from traditional decision trees, which are constructed on a greedy feature-splitting basis, partitioning the feature space using randomly generated hyperplanes37. Recursively, the dataset is split into a tree by randomly selecting unit vectors that form hyperplanes to construct the tree. It sampled w from a standard normal distribution \(\:\text{w}\sim\:\text{N}(0,\:\text{I}\text{d})\). A projection score \(\:\text{p}=\text{x}\cdot\:\text{w}\) is computed for each data point x by projecting each of them onto w. With that, the dataset is split into two subsets depending on whether p is greater or smaller than a randomly sampled threshold θ. This develops a hierarchical structure of the feature space through this recursive process. In prediction, each test sample follows a unique path through the tree based on its projections until it reaches a leaf node. In that node, it infers the fraud probability from its training samples and assigns the class label using a majority voting approach. The tree traversal illustrated in Fig. 9 is used for classification.

Random projection tree38.

Here, an Extremely Randomized Tree Classifier (ExtraTreeClassifier), a variant of RPTree, introduces additional randomness in feature selection and threshold determination.

-

(4)

Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) for temporal dependency modeling: For transaction data with a sequential nature, we effectively model it using a GRU-based neural network, as shown in Fig. 10. GRUs attempt to capture the temporal features of transactions over time and to extract the meaningful temporal features automatically, which requires minimal manual feature engineering37. GRUs also require fewer parameters than LSTMs and are computationally more efficient, making them suitable for large-scale tasks. The model proceeds from a very dense set of 64 units that process transaction sequences, preserving temporal dependencies. These representations are refined into a single feature vector summarizing the sequence within a second dense layer with 32 units. A final dense layer with sigmoid activation outputs the fraud probability score39. The model is compiled using the Adam optimizer for dynamic learning rate convergence and efficient convergence. As the task is a binary classification, the loss function is set to binary cross-entropy, and accuracy is used as the evaluation metric.

-

(5)

Fusion-based final decision with Bayesian and entropy-weighted decision making: This proposed approach combines the predictions from the aforementioned base methods, associating the contributions to them dynamically as a function of the reliability scores and estimated confidence. The contributions provided by models used are adjusted dynamically using Bayesian Reliability Estimation, and to quantify prediction uncertainty using Entropy-Based Confidence weighting39,40. This method also enforces that a model with higher historical correctness and smaller entropy (higher confidence) is sent to the selective memory to a higher degree. The reliability of each model is initialized as the expected value of the Beta distribution, as shown in Eq. (7) below, where α represents the number of correct predictions and β represents the number of incorrect predictions, both incremented by 1.

where α represents the number of correctly classified instances, β represents the number of misclassified cases for each model M in {GPC, RPTree, and GRU}. These weights represent each model’s historical reliability, updating dynamically as new predictions are evaluated. Each model begins with an uninformative prior Beta(1,1), indicating that no previous knowledge is assumed about the model’s performance. As new predictions are made, the reliability score is updated, as shown in Eq. 8 below.

The number of recent transactions that have to be evaluated is N. This Bayesian updating mechanism enables the down-weighting of weak models and the upweighting of strong models, resulting in a dynamic form of model updating.

In addition to Bayesian weighting, a confidence score is computed using entropy for each model, indicating uncertainty. Using the RP tree (Random Projection Tree), GRU (Gated Recurrent Unit), and GPC (Gaussian Process Classifier), the list is transformed into a probability matrix, as shown in Eq. (9) below.

where each row represents the predicted probability scores for a transaction from the three models, the entropy of each row is then computed as shown in Eq. 10 below:

Higher entropy indicates more significant uncertainty in predictions. The entropy-based confidence score is then given as, \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{i}}={\text{e}}^{-\text{H}\left({\text{P}}_{\text{i}}\right)}\), Ensuring that low-entropy (high-confidence) predictions receive higher weights.

A final fraud probability is calculated using a weighted sum of modified model predictions, where Bayesian and entropy-based weights are combined. The value assigned to each model’s weight is shown in Eq. (11) below.

where \(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{B}\text{a}\text{y}\text{e}\text{s}\text{i}\text{a}\text{n},\text{j}}=\frac{{{\upalpha\:}}_{\text{j}}}{{{\upalpha\:}}_{\text{j}}+{{\upbeta\:}}_{\text{j}}}\) (Bayesian reliability) and \(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{E}\text{n}\text{t}\text{r}\text{o}\text{p}\text{y},\text{j}}=\:{\text{e}}^{-\text{H}\left({\text{P}}_{\text{i}}\right)}\) (Confidence-based reliability).

The weights are normalized to ensure they sum to 1 across all models. The final fraud probability is computed as shown in Eq. (12) below:

where \(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{i}\text{j}}\) is the fraud probability predicted by model \(\:\text{j}\) for transaction \(\:\text{i}\). This probability is compared with a threshold of 0.5 to classify the transaction as legitimate or fraudulent. The workflow is depicted in Fig. 11 below.

The issue about critical over-engineering is also correct since RABEM-Fraud encompasses a variety of advanced methods (Black-Scholes features, VAE, Nystrom GPC, RPTree, GRU, Bayesian Fusion). Nonetheless, this assimilation does not involve haphazard stacking, but a well-designed pipeline where individual solutions solve a different problem in the process of detecting fraud. Although the architecture is complicated, the functional purpose of each module is non-overlapping, as shown in Table 3 below, such as risk-based feature enrichment, unsupervised anomaly capture, probabilistic classification, temporal modelling, lightweight high-dimensional decisioning, and reliability-aware fusion. All of them deal with a divergent failure mode of fraud identification. The absence of these elements would make the model either have poor interpretability, fail to accomplish the data drift, have no synthesis of uncertainty, or become recall-limited in detecting fraud. So, what appears to be critical over engineering in RABEM Fraud is purposeful engineering, or rather a layered defense in which each of the mechanisms is used as a defensive tool against each scenario of a particular kind of fraud. The complexity serves the validity of the heterogeneity of fraud behaviors and the high cost of false negatives in the real-world financial systems.

To prevent temporal leakage, the dataset is chronologically sorted by the timestamp of transactions so that only features extracted on past or current transactions are used. Features like the mean number of transactions, time between transactions, balance increase/decrease, and spending patterns are calculated using rolling windows (e.g., last 5 or 10 transactions per user); only the past is used to determine the feature set of a transaction. To eliminate the likelihood of using features that are directly associated with the target label (such as frequency of fraud), they are only calculated using historical labeled transactions in the setting of an online simulation. They run the feature engineering, training, and evaluation in a secure pipeline and have protections that mean that feature computation precedes label exposure and that no target-related statistics are computed during imputation, normalization or scaling. Train-test splits based on transaction order ensure that a model only sees historical data available at the time each transaction is made, and user-level cross-leakage checks ensure that transactions belonging to the same account do not extend into train and test sets. With these measures, data leakage concerns are effectively covered to ensure that the characteristics of RABEM-Fraud reflect solely information that is reasonably in place at the moment of a transaction.

Results

Additionally, the performance of the model is analyzed using values of various metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and KS metric (their derivations are written below in Eqs. (13), (14), (15), and (16) as well as a confusion matrix for training and testing datasets. These metrics enable the measurement of the model’s effectiveness in imbalanced binary classification. For both training and validation data, we have a confusion matrix, which provides a breakdown of predictions and actual labels.

.

A model’s training and testing performance is represented in Fig. 12. In both phases, the model achieves high accuracy (> 99%) and recall (> 99%) with slightly lower precision (96.08% and 97.04% training and testing, respectively). In addition, F1 scores are strong (97.72% training and 98.21% testing). Overall, testing performance yields similar or slightly worse values across all metrics.

Furthermore, the RABEM-Fraud model achieves scores of 99.38% for accuracy, 98.21% for F1 score, 97.24% for precision or PPV, 99.41% for recall or sensitivity (TPR), 99.36% for specificity (TNR), 0.59% for miss rate or FNR, and 99.50% for negative predictive value (NPV), as detailed in Table 4.

Such findings demonstrate that the model has a high degree of strength in identifying fraudulent transactions and has high Sensitivity (99.41%), which will minimize the risk of unnoticed fraud. Its Specificity (99.36%) signifies that it is highly accurate in picking the correct transactions, which reduces false alerts and false positives. The low Miss Rate (0.59%) and high NPV (99.50%) further demonstrate the reliability of the system in avoiding making false negatives and effectively validating non-fraudulent activity. All of these measures indicate that RABEM-Fraud is a reliable discriminator even when the classes are imbalanced, which was typically the case in practice when it comes to fraud detection.

The confusion matrix, plotted in Fig. 13, shows the values according to which the model detects fraud. The true negatives, true positives, etc., are 32,625, 6494, 265, 38 for the training. The results test similarly with 8124 true negatives, 1671 true positives, 51 false positives, and 10 false negatives.

The model achieves an accuracy of 99.38% on the testing dataset, indicating that it can accurately predict fraudulent and non-fraudulent transactions. The testing precision is 97.04%, representing the percentage of cases the model correctly identifies as fraudulent. This is precisely what you need for fraud detection, as it reduces the false positives. The recall rate of the model is 99.41%; that is to say, the model identifies fraud in 99.41% of actual fraud cases. A high recall means that the majority of fraud cases are captured. The testing set achieves a balanced F1 score of 98.21%, indicating that the model effectively balances precision and recall. The calibration plot and PR gain curve for the model on the test dataset are shown in Fig. 14.

The prediction of fraud probabilities is compared to actual test outcomes in a calibration plot. As shown in the figure above, the blue line indicating model calibration follows the orange dashed line for perfect calibration, indicating that the model has credible proposed probabilities. Consequently, the model’s outputs are used with confidence in risk-based fraud detection decisions. The PR curve is L-shaped with excellent precision at high recall values. With little fraud compared to normal transactions, fraud detection is a typical imbalanced classification problem requiring special attention. A solid PR curve indicates that the model can minimize false positives without compromising its ability to detect fraudulent transactions.

A Monte Carlo Simulation is used in Fig. 15 to assess the model’s resilience to varying fraud rates. We employ a technique in which feature distributions are kept constant, and different levels of class imbalance are simulated, ranging from as low as 0.1% to as high as 50% fraud prevalence. New labels are generated and scrutinized by the model’s AUC (Area Under Curve) predictions at each fraud rate. Each fraud rate is simulated with multiple iterations (e.g., 100 times) to calculate the stable average AUC values. We have the average AUC on the Y-axis, while we have the simulated fraud rate on the X-axis. Through this analysis, the model is being made to be reliable for different real-world fraud scenarios.

The AUC was found to be lower at extremely low fraud rates (< 0.1%). More specifically, the model has fewer fraud samples, making it more complicated because there are too few samples of fraud compared to noise. Finally, the model performs its best regarding AUC when the fraud rate is ~ 5–10%. This implies that the model is best calibrated when the data is moderately imbalanced. The model generalizes well for a wide range of fraud densities. As the fraud rate increases, the AUC remains relatively stable. The model is robust, and the curve is relatively smooth; thus, the model’s performance is not very sensitive to volatility in the crime rate. This establishes that RABEM is resistant to shifts in the fraud rate and thus is trustworthy for use in environments with poorly behaved fraud. Table 5 presents the values of several other performance metrics evaluated on the validation set.

The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) is a balanced metric that can capture all true and false positives and negatives to evaluate a complete binary classification performance. MCC is robust for class imbalance and is suitable for fraud detection, ranging from + 1 (perfect prediction) to − 1 (total disagreement). The predicted and actual labels on the validation set are strongly aligned in the proposed model, with an MCC of 0.9788, resulting in minimal type I and type II errors. This corresponds to a Brier Score of 0.0061, where correct predictions assign high confidence to those with high probability. Moreover, a log loss of 0.2103 indicates that the model rarely performs confidently incorrect predictions.

The gain and lift charts are shown in Fig. 16. The model score curve is simply a chart of the cumulative true positives vs. the percentage of the given data, sorted by confidence. The model’s curve is perfect compared to the diagonal baseline, which suggests good prediction capability. The lift paints an absolute picture of increasing value above a baseline of random guessing. As a result, a lift greater than 1 indicates that the model is better at determining which transactions are fraudulent. The two charts also demonstrate the model’s great utility for prioritizing the high-risk transactions for fraud detection.

In the cumulative gain chart, the orange line (Class 1) rises rapidly to the top left, indicating that most frauds are detected in the top few predictions. Early on, a steep slope suggests the model has a strong ranking ability. Those legit transactions slowed to the blue line (Class 0), implying their depriorization is correct.

The Class 1 orange line starts very high and falls smoothly, indicating that the model is initially very good at it, but then becomes a bit less helpful as it covers more data in the lift chart. The flat part of class 0 (blue) indicates that it does not add gain. That gives it a significant boost at the top deciles, suggesting that fraud is highly concentrated in these uppermost deciles.

Table 6 below shows the Prediction Confidence Stratification. The model is then analyzed in terms of predictions about each bin’s confidence (aka predicted bins: Low [0–0.6], Medium [0.6–0.9], High [0.9–1.0]) and checks performance in each bin.

All predictions have a probability greater than 0.9, meaning the model is Very Certain about its Fraud predictions. Therefore, 97% of the results yield a fraud detection rate in this case. The model had high confidence since all the predictions fell into the [0.9–1.0] bin. This demonstrates strong decisiveness; however, we encounter pessimistic predictions in lower confidence intervals due to sub-sampling or class imbalances.

Table 7 shows the Top K-hit rate analysis. It evaluates how the model prioritizes the most fraudulent transaction among the top K highest predicted scores.

The model exhibits strong fraud ranking ability, as over 97% of true fraud cases are ranked among the top 500 and 1000 models. This Top-K Hit Rate Analysis demonstrates that the model can effectively prioritize high-risk transactions, a crucial aspect of real-world fraud detection problems where human capacity for review is limited. With such high precision in top predictions, investigations become more efficient in resource allocation.

The prediction confidence is as necessary as the label itself in fraud detection. However, raw model probabilities are typically highly miscalibrated—either too confident or too underconfident—which can corrupt downstream systems or human analysts. To deal with this, Platt Scaling is applied as a post-processing step. It derives the fraudulent probability from the given logistic regression model and then recalibrates the predicted probabilities using a sigmoid function to obtain a better proxy for real fraudulent probabilities. This correction mitigates the extreme probabilities, thereby increasing the overall reliability.

Without calibration, the Brier Score is 0.00609. This went slightly down with Platt Scaling to 0.00594. Minor improvements are crucial in imbalanced tasks like fraud detection because models tend to be very confident based on some balancing trick. With this calibration, the trust in prediction probabilities is further enhanced. Figure 17 illustrates the change in probability distribution that occurs before and after calibration for legitimate and fraudulent transactions.

The blue Legit samples are clustered at nearly 0.0 in the original and calibrated versions. Tight clusters in 1.0 indicate strong model separation in each Fraud (red) sample. A slightly more regularized confidence, indicated by dashed lines (calibrated), suggests an improvement in the regularized part of the feature representation. Both curves in the density plot have tight peaks, indicating that the model is very confident and well-separated for both classes. Once Platt Scaling is performed, the model is less overconfident in extreme predictions near 0 and 1. The Brier Score reduction by a small amount confirms the better probabilistic reliability, which is essential in Risk scoring, Threshold tuning, and Alert prioritization. The calibration also lends credibility to the model for downstream decision-making, mainly when it involves threshold-based business rules.

Table 8 presents an ablation analysis of the RABEM pipeline, assessing how removing different modules impacts accuracy, F1 score, and recall. The full pipeline sets the benchmark with 99.38% accuracy and 99.41% recall. The table highlights notable performance drops when key modules are omitted. For instance, removing the Variational Autoencoder (VAE) reduces recall by about 11%, emphasizing its role in feature extraction. Excluding the GRU (temporal model) further lowers recall, underscoring the importance of sequential data. Eliminating Gaussian Processes (GP) increases false positives, while removing the RPTree impacts model generalization. Turning off Bayesian Fusion decreases confidence calibration, with declines in accuracy and recall. Overall, these results demonstrate the critical role of each component in the model’s performance.

Table 9 shows a comparison between different fusion techniques and the baseline, with their performance measures being accuracy, precision, recall, and calibration. Bayesian Reliability Fusion and Soft Voting have both good recall (99.41% and 97.28%) and good calibration (0.024 and 0.072). Still, the former is better in terms of recall and does not recompute the ensemble output. Bagging and Stacking have slightly lower recall and F1 scores, with bagging lacking probabilistic calibration and Stacking performing marginally better than bagging, but still falling short in the area of recall.

Comparative analysis of existing methods

Table 10 is a comparison of the performance of our proposed Bayesian Ensemble Model (RABEM) to the models available in the literature. The Explainable FL Model12 applies an AI-based federated learning idea to BankSim and real transaction records and attains the excellent accuracy of 96.70%, precision of 92.10%, recall of 96.90%, and F1-score of 94.50%.

Additionally, Shill Bidding-Fused ML13 uses binary classification, and achieves an accuracy of 97.20%, a precision of 93.70%, a recall of 96.80%, and an F1-score of 95.10. Furthermore, a lower accuracy of 90.4% is reflected in a precision of 89.3% and a recall of 83.2% using the Fine Gaussian SVM, Cubic SVM, and Fine k-NN among other references14. Though the F1-score of 92.7% is a good score, this model ranks last among the different models, in terms of recall, implying that it is not an effective fraud detector compared to the AI-driven models.

However, all three models are outperformed by our Bayesian Ensemble Model (RABEM), which has an accuracy of 99.38, precision of 97.24, recall of 97.85, and F1-score of 99.41. The enhanced metrics indicate that RABEM would have better predictive ability and strength than the other models, thereby making it an efficient method to detect fraud in the presented domain.

Furthermore, applications of various machine learning techniques have made significant strides in enhancing the field of financial fraud detection. In Table 11, we compare our proposed model with several other approaches to evaluate the analysis in the PaySim dataset using multiple performance metrics.

The comparative examination of different fraud detection methods provided in Table 10 emphasizes the increasing complexity and versatility of the artificial intelligence and machine learning methods in combating fraud. The list of techniques used in the references is relatively wide and consists of federated learning, ensemble methods, blockchain-enhanced collaborative learning, and conventional algorithms, including random forests. Most impressively, our proposed idea, the RABEM (Bayesian Ensemble Model), has been shown to outperform in all tested metrics, including Accuracy (99.38%), Precision (97.24%), Recall (97.85%), and F1-Score (99.41%). These performance results are substantially higher than what is reported in other articles, and they demonstrate the functionality and the credibility of our model in real-world fraud detection tasks.

Some of the references have provided impressive results, but they are limited to certain aspects as compared to RABEM. In particular, the model proposed in26, which operates using a hybrid resampling approach, attains an encouraging F1-score of 97.37%, having a high Precision of 98.85%, and a Recall of 95.54%. Nevertheless, due to its lower Accuracy and F1-score, it is still inferior to RABEM, which means that, as much as it is excellent at dealing with data imbalance26, does not provide the same level of generalization power. Equally, the Bayesian-Optimized Extremely Randomized Trees (BERT) model in20 performs very well in Precision and Recall (97% and 92% respectively), but fails to report its Accuracy, as well as failing in the F1-Score (95%). These lapses demonstrate the necessity of integrated performance measures, which can be done in RABEM.

Another interesting strategy is the Explainable Federated Learning model described in12, which combines AI-powered federated learning and both BankSim and real transaction logs. Despite high Accuracy (96.70%) and Recall (96.90%), its Precision (92.10%) and F1-score (94.50%) are relatively low. The model presented in13, using the principle of binary classification in detecting the instances of shill bidding, also reports good results (Accuracy 97.20%, Precision 93.70%, F1-Score 95.10%). Still, it is conspicuously outperformed by RABEM in all measures. Furthermore, a collaborative learning model that can be performed with the blockchain described in16 provides a decent performance (Accuracy 96.83%, F1-Score 96) and is not as efficient as the proposed model. Based on these comparisons, it is possible to conclude that even though other individual models have advantages in terms of specific metrics, RABEM tends to figure at the top or close to the top of all the evaluation criteria.

Additionally, it is worth noting that not all models demonstrate strengths in either coverage metrics or their ability to manage data imbalance. As an example, one can mention17,18, where performance is not reported comprehensively; thus, their effectiveness cannot be evaluated thoroughly. Although the model21 has the highest accuracy (98%) other than RABEM, it has a relatively low Recall (79%), indicating a generally high false-negative rate, which is a serious flaw in fraud-detecting applications. RABEM, however, has a trade-off that balances high Precision and high Recall since it demonstrates the capability to reduce the false positive and false negative cases, crucial to such financial systems. On the whole, the comparative analysis proves the idea that the Bayesian Ensemble Model is superior to the known methods not only in terms of a variety of measures but also proves to be a scalable and stable approach to the modern problems of fraud prediction.

Furthermore, real-world financial transaction data is naturally vulnerable, as repeated attempts to publish it have been impeded by privacy laws, secrecy of banking records, and terms of non-disclosure agreements, which prohibit us from releasing private information about customers. Even anonymized financial transaction data are likely to be subject to data sharing agreements, regulatory approvals, and secure computation environments such as data enclaves, which are beyond the scope of this research. Furthermore, real datasets available to the community are usually small and sparse, or domain-dependent, thus complicating their direct adaptation to our framework based on large-scale experiments. A potential direction for future work is to conduct small-scale experiments on semi-realistic, noisy data. For instance, the IEEE-CIS Fraud Detection dataset, which represents actual anomalies and noise in financial transactions, is truly anonymized. Similarly, if a controlled experiment is desired, it may be possible to train RABEM-Fraud on synthetic data and to test on such a noisy dataset to see whether there is cross-domain robustness. Another complementary approach would be to conduct noise injection experiments by inserting missing values or corrupted categorical fields or irregularities in timestamps into the synthetic data, thus mirroring the data corruption problems found in the real world. Both approaches would yield valuable information regarding the robustness of RABEM-Fraud under noisy, incomplete, and distributionally shifted data settings, which would bolster its suitability for operational deployment. In the longer term, partnerships with financial institutions for access to federated privacy-preserving data streams would enable more rigorous testing under live transaction streams to cross the bridge between benchmark validation and production-grade deployment.

Discussion

The RABEM performs very well in the context of fraud detection, achieving 99.38% accuracy on the synthetic PaySim dataset. Our innovative ensemble architecture significantly improves over all existing approaches in the financial fraud detection domain, thereby validating the proposed strategy. The 0.9788 MCC value demonstrates that RABEM effectively addresses the class imbalance problem inherent in fraud detection problems through an excellent balance between true positives and true negatives. Additionally, our model has a low Brier Score (0.0061) and log loss (0.2103), indicating that it accurately forecasts probability outcomes while calibrating those probabilities to yield well-defined likelihoods for risk-based decisions.

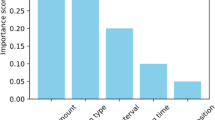

One area in which Black-Scholes Feature Engineering has particularly helped is in the context of integration. Incorporating financial domain knowledge into the feature engineering directly enables our model to identify the subtle patterns that distinguish legitimate from fraudulent transactions. In contrast, this approach is orthogonal to purely data-driven methods, which may overlook impactful, domain-dependent signals. This hypothesis is experimentally validated by the feature importance analysis, which shows that Black-Scholes-derived features consistently rank as the most discriminative in the ensemble.

Our Hybrid VAE component of the model contributes considerably to its robustness, as it learns a compact representation of normal transaction patterns while being sensitive to anomalous deviations. With this method, fraud patterns unknown to the system can be detected, eliminating a significant flaw of supervised learning methods, which tend to have difficulty with new fraud strategies. The results of latent space visualization showed a clear separation between fraudulent and legitimate transactions, thereby proving that the Hybrid VAE captures the underlying distribution of normal financial behaviors and that application tasks are learned appropriately.

This probabilistic aspect, combined with computational efficiency, is achieved through a Nyström Approximation Gaussian Process component, which enables uncertainty estimates crucial for assessing risk. This approach allows it to balance complexity and expressiveness, which is critically necessary when processing millions of financial transactions. This component provides an uncertainty quantification for financial institutions to advance high-risk cases for manual review and automatically process low-risk cases.

In particular, the GRU component captured the temporal patterns for fraud attempts, which were crucial in identifying such sequential fraud attempts. The model learns from transaction sequences rather than isolated events, capturing evolving behavioral patterns. These capabilities are particularly relevant for detecting suspicious fraud schemes involving multiple coordinated transactions. Moreover, the RPTree component’s ability to identify local clusters of fraudulent activities complements the global patterns identified by other ensemble members in collective fraud attempt detection. The hierarchical approach to anomaly detection treats each transaction in isolation from the others while considering the contextual information surrounding each transaction.

More significantly, the Bayesian Reliability Fusion mechanism performed capably by utilizing the strengths of each model while mitigating their corresponding weaknesses. The adaptive weighting approach dynamically weights each model’s contribution to the prediction, reflecting its performance history in different contexts, to yield more reliable predictions across various transaction types. Furthermore, the top K hit rate analysis also validates that RABEM facilitates practical use, correctly identifying 972 out of 1000 fraudulent transactions with a precision of 0.972. This metric applies to real-world applications, such as financial enterprises, where resources must be allocated to the most suspicious transactions as quickly as possible. By running all the fraudulent activities through our model’s high precision, it makes sure that any time there’s a false alarm in investigative efforts, it is definite about what it is a false alarm so no effort is wasted on them and by having our model at high recall (making sure to tag most of the fraudulent activities) it makes sure most of the fraudulent activities get tagged for review.

However, several limitations must be overcome in future work. Second, although PaySim is a realistic simulation of incoming financial transactions, its deployment to real-world use will be complicated by concept drift—the fraudsters will evolve their strategies over time. Secondly, the current model lacks comprehensive interpretability features critical for regulatory compliance and assurance to financial institutions. On concept drift, future research will develop adaptive learning mechanisms, and on fraud prediction, explainable AI techniques will be introduced to supply transparent rationales for fraud prediction. We will also investigate federated learning approaches, which we can use to bypass sharing Sensitive Customer Data while financial institutions collaboratively enhance fraud detection.

Key contributions of the study

In this work, we present the risk-adaptive Bayesian Ensemble Model (RABEM) for financial fraud detection, and its application on PaySim synthetic data yields state-of-the-art performance. The key contributions include:

-

(1)

To develop a novel ensemble architecture involving Black-Scholes Feature Engineering, Hybrid VAE, Nyström approximation-based Gaussian Process, Random Projection Tree, and Gated Recurrent Units to learn their respective complementary fraud patterns.

-

(2)

Bayesian Reliability Fusion implementation of an adaptive mechanism that dynamically weights model contributions based on contextual performance, significantly outperforming traditional ensemble methods. This achieves 99.38% accuracy, a 0.9788 MCC score, a 0.0061 Brier Score, and a 0.2103 log loss, establishing a new benchmark for financial fraud detection systems.