Abstract

In light of the critical threat to coral reefs worldwide due to human activity, innovative monitoring strategies are needed that are efficient, standardized, scalable, and economical. This paper presents the results of the first large-scale transnational coral reef surveying endeavor in the Red Sea using DeepReefMap, which provides automatic analysis of video transects by employing neural networks for 3D semantic mapping. DeepReefMap is trained using imagery from low-cost underwater cameras, allowing surveys to be conducted and analyzed in just a few minutes. This initiative was carried out in Djibouti, Jordan, and Israel, with over 184 hours of collected video footage for training the neural network for 3D reconstruction. We created a semantic segmentation dataset of video frames with over 200,000 annotated polygons from 39 benthic classes, down to the resolution of prominent visually identifiable genera found in the Red Sea. We analyzed 365 video transects from 45 sites using the deep-learning based mapping system, demonstrating the method’s robustness across environmental conditions and input video quality. We show that the surveys are consistent in characterizing the benthic composition, therefore showcasing the potential of DeepReefMap for monitoring. This research pioneers deep learning for practical 3D underwater mapping and semantic segmentation, paving the way for affordable, widespread deployment in reef conservation and ecology with tangible impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coral reefs are under unprecedented anthropogenic pressure, motivating effective conservation or restoration strategies that aim at preserving these valuable ecosystems for future generations. However, available monitoring data that helps to inform such strategies is often highly heterogeneous 1,2, and, especially in countries with limited monitoring and research resources, sparse3. Widely established survey methods such as photo quadrats 1,4 remain labor expensive: coral experts are needed in the post-dive image analysis process, even when using proposed computer vision tools to aid in this process 5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Structure-from-Motion (SfM) photogrammetry is used widely to obtain 3D reconstructions of reef areas, but commonly requires curated collections of high-resolution images taken in good and controlled conditions, substantial computational resources, and often human intervention to yield good reconstructions 13––19. The 3D reconstructions by themselves still have to be analyzed by reef experts, creating a bottleneck in the analysis. This limits the scalability of traditional survey methods, and inevitably includes heavy human biases due to the different protocols used and human interpretation of benthic cover. In turn, this means that aggregated monitoring campaigns are often comparable only in very coarse metrics, such as percentage of live coral 2. To devise effective conservation strategies, there is a dire need for more reproducible surveys yielding directly comparable metrics 2. Given the urgency to act to safeguard coral reefs worldwide, it is crucial to globally adopt surveying methodologies that can overcome these issues.

Recently, it has been shown that rapid semantic mapping of coral reefs and automatic benthic cover analysis straight from video using only cheap consumer-grade cameras is possible using deep learning-based mapping and semantic segmentation in a system called DeepReefMap 20. Combining the fast, logistically cheap and highly standardized data acquisition of video transects with automatic processing on affordable hardware, this method dramatically cuts the associated cost and expert knowledge required to survey coral reefs. DeepReefMap creates a semantic 3D model of the reef from a video within a few minutes, from which benthic cover can be directly extracted. In this paper, we move beyond the research prototype presented in 20 and present the first practicable system of this kind for the Red Sea, and deploy it in a real-world surveying and monitoring campaign in the Red Sea.

To this end, we introduce a set of practical improvements to DeepReefMap for more accurate semantic segmentation and 3D mapping, which lead to more precise and consistent surveys. We trained our system on a new dataset that is larger than in previous works by an order of magnitude. The semantic segmentation system of DeepReefMap is extended from 20 to 39 classes, which is trained using an improved setup that respects the hierarchical nature of the classes. This categorization yields a more fine-grained benthic categorization going down to the resolution of coral genera that can be visually identified and includes other benthic invertebrates commonly found in Red Sea reefs. We incorporate semantic guidance into the 3D mapping neural network by re-weighing the training loss using the semantic segmentation, increasing the robustness against moving objects. We also integrate a learned correction for light refraction of a linear camera in water, which improves the quality of 3D reconstructions. We correct for the covered area of the resulting orthoprojections by automatically cropping the transect orthoprojections to a desired width around the transect line detected using the semantic segmentation network, further increasing consistency between replicates of surveys.

Besides technical improvements to the 3D semantic mapping system, this paper aims to answer fundamental questions from a monitoring perspective: what is the accuracy and consistency of the benthic covers that can be expected from DeepReefMap? By analyzing 365 transect video replicates from 45 transect sites using DeepReefMap, we verify (i) the consistency of the method over time, (ii) its robustness to environmental conditions and (iii) to varying input video quality. We establish that increasing the size and diversity of the semantic segmentation dataset leads to more accurate and consistent surveys, and show that the methodology can be expected to further improve as available datasets continue to grow and machine learning systems continue to improve. Overall, our main results show that DeepReefMap offers fast and highly consistent survey results across a wide variety of reefs, that is robust to environmental conditions and video quality. Therefore, DeepReefMap is an effective and practicable surveying tool, pioneering the use of machine learning in real-world large scale video surveying campaigns.

Methods

Dataset

Video data was collected from 53 dive sites in the Red Sea during expeditions and coral reef monitoring training workshops of the Transnational Red Sea Center hosted at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL). In total, there are 184 hours of video from Israel, Jordan, and Djibouti, taken between March 2022 and July 2024. All videos were filmed using GoPro Hero 10 cameras in the linear field-of-view setting. A detailed protocol of data acquisition is available in the Supporting Information..

Schematic overview of the data collection and processing in this paper. For each transect site located in one of the three countries, multiple videos are taken along the entire length of the transect line at different times. Each video is separately processed using DeepReefMap to yield a 3D point cloud and a 2D ortho-projection (after second black arrow), from which the benthic cover percentages (rightmost panel) can be computed.

This large video dataset encompasses footage from over 45 transect sites marked by transect lines of known length in meters (not at every dive site, there was a transect conducted), on which a total of 365 transect video replicates were filmed: each video replicate is one video filmed by a diver swimming over the entire transect line. Footage was filmed by 13 divers in total, with at least four video replicates of each transect. A schematic overview of the data collection is shown in Fig. 1. The largest share of transect sites (26/45) and video replicates (171/365) is of 100m length, the full distribution of transect/replicate lengths, along with additional metadata for each transect, can be found in the Supporting Information (Fig. S11, Table S1). In particular, to enable a long-term consistency evaluation, one 38m-long transect in Israel has been replicated a total of 78 times across various environmental conditions (seawater temperature, turbidity, time of the day, speed of swimming) during the hottest and coldest months (August and March) of 2023 and 2024.

For each video replicate on a transect, the quality of the video is categorized between excellent, very good, good, acceptable, bad, and very bad. An excellent video pass satisfies the following criteria:

-

The beginning and end points of the transect line are clearly visible.

-

The transect line is clearly visible throughout the whole video.

-

The camera is held steadily by the diver throughout the length of the transect line, and there is no substantial jerky movement and induced motion blur.

-

The camera (pitch) angle chosen such that the substrate is clearly visible and held constant throughout the video.

-

The distance from the camera to the reef substrate held largely constant with a minimum of 1m and a maximum of 3m, with the diver following the reef morphology to ensure this.

Videos that violate these criteria are assigned a lower quality rating, which is assigned depending on the gravity of the violations. A discussion of these criteria, and corroboration with supplementary quantitative metrics (mean % of ‘background’ identified by semantic segmentation over all frames, and the % of frames per video replicate on which the transect line is not visible) is found in the Supporting Information (Fig. S12). In total, 73.15% of video replicates were deemed excellent, 10.41% very good, 9.31% good, 3.01% acceptable, 2.74% bad, and 1.37% very bad. The fact that the vast majority of video replicates meets the quality criteria underlines the ease of data acquisition for DeepReefMap.

Semantic segmentation

Semantic segmentation is used in DeepReefMap for two purposes: first, to guide the 3D reconstruction by masking unwanted classes from the video frames, such as the background water column or moving fish to prevent artifacts in the 3D model; second, to attach the benthic class information to the 3D point cloud of the static reef. Therefore, more accurate and more fine-grained semantic segmentation directly translates to a more powerful surveying tool.

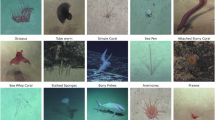

To this end, we created the largest dense segmentation dataset of benthic classes to date, counting more than 200,000 delineated polygons. This dataset is a superset of Coralscapes 21, and more than an order of magnitude larger than the dataset of Sauder et al. 20, which are the only other datasets annotated for dense semantic segmentation, i.e. with polygons, compared to other coral datasets annotated with either sparse point annotations 22,23,24,25, only image-level annotations 10,26,27, or only segmentation masks of salient corals, but excluding some corals and all other benthic classes 28,29. The polygons are annotated over 2,216 video frames, which have been selected to include frames from each of the 32 visited dive sites, even those where no transect was conducted, and to get a representative sample of the diverse environments and the contained benthic classes. The first 1,000 frames were selected at random from the video dataset in order to capture the diversity of the scenes. Then, the remaining frames were selected manually to reach a good coverage of the 39 classes, prioritizing rare classes and ensuring at least 70 annotated instances of every class. The polygons were annotated with the CVAT 30 annotation tool, using the Segment Anything Model 31 as an interactor during annotation.

Annotation Strategy: The class labels used during annotation (a) containing three levels of hierarchy and how they are summarized. All three levels of granularity are used during training of the semantic segmentation neural network to guide the network to respect the hierarchical nature of the labels. A schematic example of how the labels were assigned during annotation to minimize speculation is shown in (b): the two corals are initially assigned ‘background’ when they are too far away to be clearly identified as live coral (leftmost panel). As they move closer, they are labeled as ‘branching coral’ before first the Stylophora and then the Acropora can be identified from the characteristic branch structures (rightmost panel).

Annotating reef scenes is extremely challenging both due to the visual degradation caused by the water column and because some benthic classes can be difficult to visually determine even by experts and in good conditions. Many corals display strong morphological plasticity 22,32, which makes classifying corals to a high taxonomic level from images difficult. While some genera have visually distinct features, many coral species and some coral genera can simply not be reliably identified from images, even with expert domain knowledge of specific biogeographic areas and high-resolution close-up images of the individual polyps. To avoid speculation for such corals, usually the growth form is identified as the maximum level of recognition. Live corals are not the only source of ambiguity: fine algal mats only become apparent when viewed closely and are indistinguishable from non-algae-covered substrate at a larger distance. Furthermore, dead hard corals leave behind calcium carbonate skeletons which, as they degrade, become a rocky substrate that can be overgrown with algae or disintegrate into rubble. These substrates can often be correctly assigned to two or more classes while following these degradation processes. Despite these inherent ambiguities, these classes are of real interest to coral surveyors that monitor how a reef’s state changes with time, and should be identified by an automatic tool any time that they are clearly identifiable. At the same time, there should be no speculation, when a polygon is assigned a label that may be correct.

To this end, the annotated benthic classes are organized in a tree (Fig. 2a) that captures the hierarchical structure of the classes of interest. The tree contains three levels, with the finest, intermediate, and coarse categorization including 39, 23, and 14 classes, respectively. The class categorization is inspired by the CATAMI 33 scheme, but adapted to corals of Red Sea, and the general-purpose reef scene images as opposed to close-ups of coral polyps or small organisms. The neural network’s prediction should always be conservative in terms of the taxonomic depth of the predicted class, therefore the annotation was strictly done in a speculation-free manner: polygons are assigned the finest class in the tree that can be determined with certainty, as illustrated in Fig. 2b. We include ‘dark’ and ‘background’ classes to designate image areas that are obstructed by poor lighting or shadows and areas that are too far away to be classified with certainty, respectively. As DeepReefMap is primarily used for video transects, many areas that are assigned ‘background’ become clearly visible later in the video as the camera moves closer while the diver follows the transect line. While the exact delineation of such areas is to a certain degree subjective, they serve the purpose of further reducing possible ambiguities, as areas classified as these two classes are excluded from the final benthic cover analysis.

Our semantic segmentation dataset, created in approximately 2,000 hours of expert annotation time, captures significantly higher diversity of scenes than existing datasets: from clear to murky waters, from sandy reef flats to steep rocky reef walls, from severely damaged reefs with substantial bleaching to thriving healthy reefs. Examples of annotated frames are shown in the Supporting Information (Fig. S13), along with precise information about the label distribution (Fig. S14).

This dataset is used to train a semantic segmentation neural network. We use a ResNeXt50-32x4d 34 backbone with a DeepLabV3+ 35, which learns to predict dense segmentation maps on images at \(768\times 1280\)px resolution. Three separate linear output heads (with 39, 23, and 14 output neurons) followed by softmax layers take the dense last hidden layer features and output the pixel-wise class probabilities for each of the three levels of granularity in the label tree. The loss is computed as a sum of these three output heads, ignoring the pixels that have not been annotated with a ground-truth label when computing the training loss. During inference, the \(1080\times 1920\)px resolution input image is simply downscaled to \(768\times 1280\)px and passed through the neural network. This enables a higher throughput in frames per second than the patch-based prediction used in Sauder et al. 20. Unless otherwise specified, the transect analyses are performed with a segmentation model trained on 2168 training images that exclude 48 images from a single transect in Eilat as a validation set, but include other training images from Eilat. Implementation and training details are provided in the Supporting Information.

Improved learning-based SLAM

Semantic guidance in learning-based SfM

The 3D mapping in DeepReefMap20 uses learning-based Structure-from-Motion (SfM). In particular, it uses reprojection errors from rigid transformations of overlapping video frames as a self-supervised learning signal to train neural networks to predict pixel-wise dense depth and relative 6D camera pose transform (3D rotation and translation) 36,37. Minimizing dense reprojection errors makes the assumption of a static scene. When the dynamic objects visible on the overlapping part of the images is much smaller than the visible static scene, then the pose estimation remains correct, as the neural network would be heavily penalized for a wrong rigid transformation on most of the image. However, large dynamic objects can lead to mis-estimation of the camera pose. In images that otherwise contain mostly uniform texture like sand or the water column, even smaller dynamic objects can lead to errors.

Improvements to learning-based SLAM: Example image pairs (a) used to compute the reprojection error during training. From the two overlapping images \(I_1,I_2\), a respective weight mask (b) is applied to the re-projections (c) to calculate the re-projection error (d). This reduces the influence of unwanted classes on the training error (e), increasing focus on learning the geometry of coral reefs. Furthermore, the refraction-induced distortion of frames coming out of the camera (f) is rectified using the EUCM with the learned distortion parameters (g).

To get more robust and accurate pose and depth estimates, we use the trained semantic segmentation system within the self-supervised training of the monocular SLAM system to give more importance to the rigid substrate and less weight to dynamic objects and the water column, instead of only using the semantic segmentation at inference time. To this end, the pixel-wise photometric error mask is re-weighted according to the predictions of the semantic segmentation neural network by multiplying the predicted class probabilities with per-class weights. When computing the error between two images, the class-weight mask from the source image is projected to the target image just like the RGB values, and the minimum of the target and projected source weight masks are used to compute the final error.

In particular, after training the monocular SLAM system for 1 million iterations without using semantic information (to save computational cost), we train the network by giving ‘fish’ and ‘diver’ a weight of zero, ‘transect tools’ and ‘transect line’ a weight of 0.3 (as they can be moved by the water current), the background a weight of 0.1, and remaining substrate classes are given a weight of 1. We fine-tune with these weights for 300,000 iterations. The integration of semantic guidance in the learning-based SfM system is illustrated in Fig. 3: in both example image pairs, the error map is dominated by the moving objects (the fish and the divers), which is mitigated by re-weighting, leaving only the learning signal on the substrate.

Refraction modeling

When light rays move from the water through the camera lens into the camera filled with air, the change of medium leads to refraction, resulting in a distorted image. To tackle this, we include the Extended Universal Camera Model (EUCM)38 in the learned monocular SLAM system.

In Sauder et al.20, the re-projection of the video frames using the estimate depths was implemented as a linear pinhole camera model, where the projection of a 3D point to the 2D camera plane is defined using the focal lengths \(f_x,f_y\) and the principal point \(c_x, c_y\) as:

While this approximation led to reasonable results, the inclusion of an explicit model of the refraction holds the potential to increase the quality of the 3D reconstructions. The EUCM extends the camera parameters by two distortion parameters \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), using a projection on an ellipsoid followed by a pinhole model:

where:

The distortion parameters are simply included in the gradient-based optimization of the self-supervised deep monocular SLAM system, similar to Fang et al.39, with the values converging to \(\alpha =-0.58, \beta =0.88\), correctly undistorting the lens, as shown in Fig. 3. These values were verified by performing underwater calibration with OpenCV and comparing the mean absolute error of the rectification from the OpenCV and EUCM camera models.

Automatic benthic cover analysis

We design the automated analysis of the video transects to maximize consistency and comparability of acquired survey data. Each video processed by DeepReefMap leads to a 3D point cloud20, which is then ortho-projected by using the gravity vector of the telemetry data from the camera to determine the nadir view angle. However, the precise ground area covered depends both on camera angle and distance to the reef. To normalize the ground area covered, we use the known length of the transect line to crop the orthomosaic to a chosen metric distance from the transect line, as shown in Fig. 4. First, a line is fit through the pixels in the orthomosaic that are classified as ‘transect line’ using a Gaussian smoothed linear 1D spline. Then, the length of this line in pixels is computed, giving the metric distance of each pixel, which allows masking all pixels further than a specific distance from the transect line (implemented via a 2D convolution on the 2D orthoprojection). This automatic procedure for cropping transects to the desired width takes less than 2 seconds, and makes the assumptions that i) there is only one transect line visible in the video, ii) that the transect line is longer than the wanted width of the orthomosaic, and iii) that the transect line is laid out mostly straight. The benthic cover is then computed as the ratio of the pixels of the orthomosaic belonging to a class and the total number of occupied pixels, after removing classes that should not influence the benthic cover, namely ‘transect line’, ‘transect tools’, ‘dark’. Unless otherwise specified, the analyzed transects are cropped to 1m width.

Example of how results from four different video replicates from two different dives of the same transect are automatically cropped to the same area. From top to bottom: the area covered by the orthoprojection of the 3D point cloud can differ depending on how the video was taken (top row). By using the transect line of the semantic orthoprojection (second row) with known length to give a scale (50m in this example), the RGB and semantic orthoprojection can be cropped to a metric distance (here 1m) around the transect line for increased consistency of surveying results (third and fourth row).

To measure the fidelity of surveys conducted with DeepReefMap, we measure the mean per-site per-time standard deviation: for each transect site, the mean percentage cover of a benthic class from all video replicates of this site from a given time point is computed. This is used to compute the standard deviation of the video replicates to the transect site mean, and is then averaged over all sites. Two video replicates are considered from the same time point if they are taken within two weeks of each other.

Results and discussion

This paper presents a comprehensive analysis of the performance of coral reef surveys conducted using DeepReefMap. The primary focus is on demonstrating the accuracy and consistency of the method, which forms the core result of this work. We also assess the robustness of the approach under varying input video qualities and verify the robustness to environmental conditions to establish its practical applicability in diverse real-world scenarios.

Furthermore, we investigate the influence of data used during training of the semantic segmentation system, showing that systems like DeepReefMap will continue to improve in the future and providing insights into how the method will perform on new biogeographic area. Lastly, we conduct an ablation study to corroborate the positive contribution of individual changes made to the learning-based 3D-mapping neural network setup.

An overview of all benthic cover results obtained from the 365 transect video replicates over 45 transect sites acquired and processed with DeepReefMap is shown in Fig. 5. Aggregated over all transect sites, which range from 2% to 67% estimated live coral cover, we find the mean per-site per-time standard deviation of live coral cover to be 2.51%.

Benthic cover prediction for all transects: Top: Each of the 365 colored columns represents one replicate (video) of a transect, showing the measured benthic composition. The 45 different transect sites are separated by a black column and sorted by their median estimated live coral cover. Bottom: corresponding box-plots of the estimated live coral cover with transect ID and country code.

Consistency of surveys

Robustness against filming quality

First, we investigate the effect that the quality of the transect video replicate has on the consistency. We filter the video replicates by every quality label (from ‘excellent’, to ‘very bad’), keeping only video replicates with each label or better, and compute the per-site per-time standard deviation of live coral cover (Fig 6a) and the relative increase of this deviation compared to ‘excellent’ videos over the 12 most common benthic classes in the surveyed transects (Fig 6b). The results clearly show that better video replicate quality leads to more consistent results with DeepReefMap. At the same time, the results indicate general robustness against video quality: lower video qualities gradually degrade the results but do not lead to catastrophically inconsistent results. The same observations can be made for the individual classes: a slow increase in standard deviation can be observed with poorer video quality for most classes, with no dramatic explosions of inconsistency.

Robustness against conditions and temporal consistency

To verify that the conditions during the dives have a negligible effect on the results produced by DeepReefMap, six transects were conducted off the coast of Aqaba (Jordan) by three teams of two divers each, on two separate reefs and two separate days at 6m, 9m, and 12m depth. Four replicates of the transect (two by each diver in the team) were filmed in the late afternoon, and another four replicates were filmed the next morning (after re-deploying the transect line using salient reef features). While the lighting and turbidity change between the two visits of the site, we assume that the coral cover does not change significantly within the short time span. The results are shown in Fig. 7a, showing no large change in estimation of live coral cover.

A calculation of two-sample T-tests between the two populations for each of the six transects leads to p-values of [0.34, 0.87, 0.0026, 0.52, 0.024, 0.23], which, with exception of the third of these transects (“11 JOR”), do not warrant rejection of the hypothesis that the populations are drawn from the same distribution (under p=0.01). For the third transect (“11 JOR”), three out of eight video replicates are of quality ‘acceptable’, while all other video replicates of the six transect sites are of quality ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ (with an exception of two ‘good’ video replicates on transect six “14 JOR”).

We conduct a similar analysis in Eilat, where we run two-sample T-tests for the live coral cover estimates from subsequent dives (Fig. 7b). We find that the most significant observed change (p=0.00029) appears between the transect analyses of 2024.03.08 and 2024.08.01, which are from a different season. All p-values from comparisons within the same season are at least 100 times larger (p\(\ge\)0.027), indicating a much smaller measured change in live coral cover. Conducting the same test on the seasons, we find a significant change in coral cover between 2023.03 and 2023.08 (p=0.00024), as well as 2023.08 and 2024.03 (p=0.0006). These results suggest the that DeepReefMap is robust across conditions within the same season, but can pick up on longer trends, indicating that the method is suitable for long-term monitoring.

Temporal consistency: Estimated benthic cover & live coral cover boxplot of the 1.8m-cropped ortho-projection from six transects filmed eight times (a), four of which in the afternoon, and four in the morning of the following day (separated by black column). In (b), the results for all 78 video replicates of a single transect in Eilat, revisited in August/March of 2023 and 2024, grouped by sampling dive with date (left) and by season (right) are shown.

Reef morphology and transect width

In this Section, we aim to assess the effect of the chosen width that the transects are automatically cropped to around the transect line, and give insights on how to choose an appropriate value. Wider transects (obtained from a greater distance away from the reef) cover more ground and can give a better estimate of the benthic cover of an area, but on the other hand are prone to inconsistencies from occlusions in structurally complex reefs, and the increased distance between camera and reef captures the seafloor at a lower resolution, reducing the accuracy of the semantic segmentation.

We perform a grid search from 20cm to 3.8m, evaluating the consistency in terms of the mean per-site standard deviation of live coral cover. The results, averaged over all 365 transects, are shown in Fig. 8a, as well as the results for a selected subset of 7 transects which are on very flat reef environments, and another subset of 8 transects which follow the contour line of reef walls, and are marked by higher structural complexity (example video frames from these are shown in Fig. 8). The results show that transects in flat reefs are less sensitive to the choice of crop width, with values between 1m and 2m leading to the highest consistency, whereas the choice of crop width has a higher impact on reef walls, with a sharper optimum at 1.6m width. Averaged over all transects, the highest consistency is achieved at 1.8m.

Impact of the reef morphology on survey consistency & optimal crop width: The absolute (a) and relative (b) mean per-site per-time standard deviation of live coral cover as a function of the width that the transect is cropped to on all evaluated transects, as well as prototypical reef flats (c), and reef walls (d).

The results in Fig. 8a suggest that on average, transects in flatter reef areas lead to more consistent surveys than in reef walls. To disentangle the actual increased consistency from the fact that the evaluated transects on the reef walls have a higher mean coral cover (47.08%) than the evaluated flat reefs (40.18%) and all transects (27.03%), we repeat the same analysis but using the normalized per-site standard deviation of live coral cover, in which the values for each site are normalized by the site’s mean live coral cover (Fig. 8b). Sites with a live coral cover of less than 10% are excluded from this analysis as their high relative variances dominate those of sites with higher covers. This reduces the gap in consistency between reef wall and the mean of all transects significantly, but the results corroborate that flatter reefs are better suited to obtain more consistent surveys.

Semantic segmentation

In this Section, we provide a quantitative analysis of the semantic segmentation on an image level and take a closer look at the effect of the semantic segmentation on the consistency of surveys.

We start by evaluating the semantic segmentation on an image-level to assess the impact of the training data. To this end, we hold out a test set of 48 images annotated with 4,500 polygons from a transect in Eilat (25 images from an afternoon dive, 23 images from a morning dive). There remain 2,168 images that can be used for training, of which 199 are from the same reef in Eilat, but acquired at different time instants and at different locations on the reef.

To capture the effect of increasing the number of training images, as well as the importance of the training images including images from the specific biogeographic region that DeepReefMap used in, we train 8 segmentation models using 100%, 50%, 25%, 12% of the training images with and without the 199 images from Eilat.

The segmentation results on the test set are displayed in Fig. 9 and clearly indicate across all metrics that increasing the dataset size leads considerable improvement in results. Especially when evaluating at the fine-grained class hierarchy, the metrics still show a significant increase from 50% to 100% of the used data, clearly indicating that further increasing the dataset size will still yield performance gains. The effect for including images specific to the biogeographic domain is also large: increasing the dataset size with domain-specific data by less than 10% leads to a larger improvement on mIoU than doubling the dataset size with domain-unspecific data. In general, these results underline that creating larger and more comprehensive semantic segmentation datasets is essential to obtain globally accurate automatic surveys driven by machine learning.

Impact of Semantic Segmentation on Consistency: (a) Image-level performance on the held-out test set of images from the transect in Eilat as a function of dataset size and inclusion of data from the specific biogeographic area. In (b), these models are used on all transect video replicates and the per-site standard deviation is measured, clearly showing that a larger dataset and better image-level segmentation indeed translate to more consistent surveys. .

The insight that creating more comprehensive semantic segmentation datasets leads to better image-level segmentation raises the question how much of this effect translates to more consistent surveys. To this end, we run DeepReefMap on all transects using each of the eight segmentation models from the different training data mixes. We plot the mean per-site per-time standard deviation of live coral cover as a function of the dataset size averaged over all transects, as well as for the transect in Eilat, in Fig. 9. This simulates the use of DeepReefMap in a visually distinct new reef area with and without having semantic segmentation training data from this reef. Our results corroborate that better image-level semantic segmentation indeed lead to more consistent surveys, and underline that domain-specific semantic segmentation annotations can lead to substantial improvements. The deviation of the Eilat transect is strongly reduced by including a small number of domain-specific images from the Eilat reef. Averaged over all transects, where these included images are not domain-specific, the effect of including the small number of training images from Eilat is smaller.

Further experiments quantifying the improvements of the semantic segmentation with regards to20, and assessing the in-distribution performance of the semantic segmentation system for each class are provided in the Supporting Information (Table S2, Fig. S15, Fig.S16, Fig. S17).

Ablation study of learning-based SfM

To quantify the impact of changes made to the 3D mapping neural network setup, we ablate every change and measure the change in photometric error of the reprojections, averaged over 10 held-out test videos that were not used during training. Fish and divers are masked out from the error using semantic segmentation. First, we compare the distribution of photometric errors using frame pairs chosen 0.167s apart (5 frames apart at 30 FPS) and 0.333s apart (10 frames apart at 30 FPS). We use the model from Sauder et al.20 as a baseline, and measure the effect of implementing the changes described in the Methods Section: using a larger training video dataset, using EUCM to model diffraction, and using the semantic guidance. The results are shown in Fig. 10, clearly indicating a lower reprojection error with every proposed change for both frame distances.

Conclusion and future work

In this paper we evaluate the suitability of DeepReefMap, which automatically processes coral reef transect videos using machine learning, as a real-world coral surveying method. Over 365 video transect replicates from 45 transect sites, we find a mean per-site per-time standard deviation of live coral of 2.51%. We conduct experiments that show that the surveys are robust to changes in environmental conditions, and deliver stable results in a reef monitored over two years. We quantified the effect of transect video quality on the benthic cover results, showing increased consistency with better video quality, and reiterate that 83.6% of video replicates have a ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ video quality, underlining the ease of data acquisition for DeepReefMap. We evaluate the impact of the width of the automatic crop around the transect line, which can depend on the site. We show that the semantic segmentation presented in this paper substantially improves over Sauder et al.20, and that better image-level segmentation indeed translates to higher consistency of surveys. The results also clearly indicate that increasing the size of the semantic segmentation dataset would further increase the accuracy and consistency of surveys.

This motivates future work for improving machine learning-based coral monitoring tools like DeepReefMap: one clear line of work is to further extend the semantic segmentation dataset in terms of size, diversity of scenes, and class resolution, and including separate classes for visually distinct reef inhabitants that have important impacts on the ecosystem, including for example the crown of thorns starfish. Improvements to the 3D mapping network, for example more accurate depth and pose estimation or the support of different camera models, are within reach from a technical perspective, and are expected to lead to more and better surveys being realized with DeepReefMap.

Overall, DeepReefMap proves to be a suitable surveying tool for tropical coral reef monitoring, allowing to rapidly conduct consistent surveys with low-cost equipment that are automatically processed within a few minutes. As the underlying machine learning systems will undoubtedly continue to improve, principled data acquisition will be increasingly emphasized as the key to effectively monitoring coral reefs. A high spatio-temporal coverage of image or video data from as many reefs as possible, along with accurate cataloging of acquisition metadata should be of highest priority for monitoring teams, as machine learning emerges as a promising tool to solve the bottleneck of analyzing massive datasets of acquired coral reef monitoring data.

Data Availability

The source code to reproduce all experiments is found on Github at https://anonymous.4open.science/r/mee-deepreefmap-D8E7 (archived on Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/10649621), including trained model checkpoints. Example input videos, and annotated video frames for semantic segmentation are found on Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/10624794.

References

Obura, D. O. et al. Coral reef monitoring, reef assessment technologies, and ecosystem-based management. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 580 (2019).

Souter, D. et al. Status of coral reefs of the world: 2020. Glob. Coral Reef Monit. Netw. (2021).

Souter, D. et al. Status of coral reefs of the world: 2020 chapter 3: Status and trends of coral reefs of the red sea and gulf of aden. Glob. Coral Reef Monit. Netw. (2021).

Delaval, N. P., Wicquart, J., Staub, F. & Planes, S. Status of coral reef monitoring: An assessment of methods and data at the national level. Int. Coral Reef Initiat. (2021).

AIMS. Reefcloud.ai. https://reefcloud.ai/ (2023).

Beijbom, O., Edmunds, P. J., Kline, D. I., Mitchell, B. G. & Kriegman, D. Automated annotation of coral reef survey images. In 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 1170–1177 (IEEE, 2012).

Pablo, L. X. et al. A doubling of stony coral cover on shallow forereefs at Carrie Bow Cay, Belize from 2014 to 2019. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 19185 (2021).

Ferris, Z., Ribeiro, E., Nagata, T. & Woesik, R. Rescape: Transforming coral-reefscape images for quantitative analysis. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 8915 (2024).

MERMAID. Marine ecological research management aid (mermaid). https://datamermaid.org/ (2023).

Raphael, A., Dubinsky, Z., Iluz, D., Benichou, J. I. C. & Netanyahu, N. S. Deep neural network recognition of shallow water corals in the Gulf of Eilat (Aqaba). Sci. Rep. 10(1), 12959 (2020).

Remmers, T. et al. Rapidbenthos: Automated segmentation and multi-view classification of coral reef communities from photogrammetric reconstruction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 16, 427–441 (2024).

Rodriguez-Ramirez, A. et al. A contemporary baseline record of the world’s coral reefs. Sci. data 7(1), 355 (2020).

Bayley, D. T. I. & Mogg, A. O. M. A protocol for the large-scale analysis of reefs using structure from motion photogrammetry. Methods Ecol. Evol. 11(11), 1410–1420 (2020).

Bongaerts, P. et al. Reefscape genomics: Leveraging advances in 3d imaging to assess fine-scale patterns of genomic variation on coral reefs. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 638979 (2021).

Burns, J. H. R., Delparte, D., Gates, R. D. & Takabayashi, M. Integrating structure-from-motion photogrammetry with geospatial software as a novel technique for quantifying 3d ecological characteristics of coral reefs. PeerJ 3, e1077 (2015).

Kopecky, K. L. et al. Quantifying the loss of coral from a bleaching event using underwater photogrammetry and ai-assisted image segmentation. Remote Sens. 15(16), 4077 (2023).

Leon, J. X., Roelfsema, C. M., Saunders, M. I. & Phinn, S. R. Measuring coral reef terrain roughness using ‘structure-from-motion’ close-range photogrammetry. Geomorphology 242, 21–28 (2015).

Pascoe, K. H., Fukunaga, A., Kosaki, R. K. & Burns, J. H. R. 3d assessment of a coral reef at lalo atoll reveals varying responses of habitat metrics following a catastrophic hurricane. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 12050 (2021).

Rossi, P., Castagnetti, C., Capra, A., Brooks, A. & Mancini, F. Detecting change in coral reef 3d structure using underwater photogrammetry: Critical issues and performance metrics. Appl. Geomat. 12, 3–17 (2020).

Sauder, J., Banc-Prandi, G., Meibom, A. & Tuia, D. Scalable semantic 3d mapping of coral reefs with deep learning. Methods Ecol. Evol. 15(5), 916–934 (2024).

Sauder, J. et al. The coralscapes dataset: Semantic scene understanding in coral reefs. arXiv preprintarXiv:2503.20000 (2025).

Alonso, I., Yuval, M., Eyal, G., Treibitz, T. & Murillo, A. C. Coralseg: Learning coral segmentation from sparse annotations. J. Field Robot. 36(8), 1456–1477 (2019).

King, A., Bhandarkar, S. M. & Hopkinson, B. M. A comparison of deep learning methods for semantic segmentation of coral reef survey images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops 1394–1402 (2018).

Lowe, S. C. et al. Benthicnet: A global compilation of seafloor images for deep learning applications. arXiv preprintarXiv:2405.05241 (2024).

Yuval, M. et al. Repeatable semantic reef-mapping through photogrammetry and label-augmentation. Remote Sens. 13(4), 659 (2021).

Jamil, S., Rahman, M. U. & Haider, A. Bag of features (bof) based deep learning framework for bleached corals detection. Big Data Cognit. Comput. 5(4), 53 (2021).

ASM Shihavuddin. Coral reef dataset, v2. https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/86y667257h/2.

Furtado, D. P. et al. # deolhonoscorais: A polygonal annotated dataset to optimize coral monitoring. PeerJ 11, e16219 (2023).

Zheng, Z. et al. Coralscop: Segment any coral image on this planet. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 28170–28180 (2024).

CVAT.ai. Cvat https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4009388. https://github.com/cvat-ai/cvat (2023).

Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 4015–4026 (2023).

Todd, P. Morphological plasticity in scleractinian corals. Biol. Rev. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 83, 315–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00045.x (2008).

Althaus, F. et al. A standardised vocabulary for identifying benthic biota and substrata from underwater imagery: The catami classification scheme. PLoS ONE 10(10), e0141039 (2015).

Xie, S., Girshick, R., Dollár, P., Tu, Z. & He, K. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 1492–1500 (2017).

Chen, L.-C., Zhu, Y., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F. & Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) 801–818 (2018).

Bian, J.-W. et al. Unsupervised scale-consistent depth learning from video. Int. J. Comput. Vision 129(9), 2548–2564 (2021).

Zhou, T., Brown, M., Snavely, N. & Lowe, D. G. Unsupervised learning of depth and ego-motion from video. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 1851–1858 (2017).

Khomutenko, B., Garcia, G. & Martinet, P. An enhanced unified camera model. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 1(1), 137–144 (2015).

Fang, J. et al. Self-supervised camera self-calibration from video. In 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) 8468–8475 (IEEE, 2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Ali Al-Sawalmih and Tariq Al-Salman (Marine Science Station, Aqaba), Prof. Maoz Fine, Nahum Sela (InterUniversity Institute of Marine Science, Eilat), Dr. Assaf Zvuloni (Nature Reserve Authority Israel), the Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority of Jordan, the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development of Djibouti and the University of Djibouti for their support for enabling us to collect the videos. We thank Chiara Freneix, Géza Soldati, Camille Perrin, Amélie Menoud, Ines Stiti, Martin Métier, and Antoine Carnal for help with the frame annotations. The data of this study were collected in the framework of the Transnational Red Sea Center hosted by the Laboratory for Biological Geochemistry at EPFL. This work was funded in part by FNS grant 205321_212614, as well as EPFL and the Transnational Red Sea Center.

Funding

This work was funded in part by FNS grant 205321_212614, as well as EPFL and the Transnational Red Sea Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS, GBP, AM and DT designed the methodology and prototype. All authors collected substantial field data. JS wrote the source code and analyzed the data, and led the writing of the manuscript; all authors contributed substantially to writing and revising the manuscript and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with the work presented in this publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sauder, J., Banc-Prandi, G., Perna, G. et al. Rapid consistent reef surveys with DeepReefMap. Sci Rep 15, 39145 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20795-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20795-z