Abstract

While lifestyle modification is recommended as first-line treatment for lowering blood pressure (BP) in individuals with prehypertension and drug-naïve stage 1 hypertension, there is a paucity of randomized controlled data on such subjects. This multicenter, open-label, randomized clinical trial enrolled 70 participants (N = 35 per group) with prehypertension and drug-naïve stage 1 hypertension, defined as a systolic BP (SBP) of 130–159 mmHg and/or a diastolic BP (DBP) of 85–99 mmHg. The diet & exercise (D&E) group received counseling and monitoring on diet (DASH; dietary approaches to stop hypertension) and regular physical exercise for 12 weeks. The primary outcome was the change in systolic and diastolic BP after 12 weeks. Secondary outcomes included the 24-hour BP and its components and inflammatory markers. Compared with the control group, office SBP and DBP were reduced in the D&E group by 15.1 (-8.73 vs. 6.38 mmHg, p = 0.003) and 6.68 (-4.57 vs. 2.11 mmHg, p = 0.003) mmHg, respectively. The 24-hour ambulatory SBP did not change significantly in either group after 12 weeks (-0.72 vs. 1.92 mmHg, p = 0.667). In subgroup analysis, female, older-age participants and participants with higher baseline BP showed higher reductions in office SBP. Positive effects on office BP were noted by dietary and exercise education, especially in female and older-age participants.

Trial registration: 15/05/2022, NCT05274971.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension affects millions of individuals worldwide, and underlies the pathogenesis of many disease entities such as heart failure, stroke, renal failure or even certain types of cancer1,2,3. The prevalence of hypertension in Korea has increased consistently from 24% in 2010 to 28% of adults in 20214. Prehypertension is the term for blood pressures (BP) above normal and below clinical hypertension threshold. Although prehypertensive individuals are frequently overlooked in practice, prehypertension tends to progress into hypertension over time and presents elevated risk for cardiovascular diseases5,6. The effects of diet and exercise on blood pressure have been implicated from some of the earlier studies on hypertension to modern guidelines on BP reduction7,8,9,10. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension, or the DASH diet, is a dietary recommendation specifically designed to target hypertension by lowering the intake levels of salt, ultra-processed foods and outdoor meals, focusing instead on vegetables, fresh fruits, whole grains, fish, low-fat dairy products and unsaturated fatty acids9. Studies have shown that blood levels are significantly lower under the DASH diet11. Physical activity also lowers BP, likely by multiple complex mechanisms including the regulation of endothelial functions, nitric oxide synthesis and angiogenic functions12,13,14. Many studies have successfully demonstrated that exercise training reduces ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension15,16. Concrete evidence for exercise on prehypertension and/or mild hypertension, however, is limited to relatively older, observational studies17,18,19.

In this study, we aimed to fill the gap in evidence for the role of dietary and exercise intervention in participants with prehypertension and drug-naïve grade 1 hypertension, for whom lifestyle modifications are recommended as first-line treatments over medical drugs. Additionally, as a growing body of evidence suggests that inflammation and the immune system plays at least a partial, if not a crucial, role in the genesis of hypertension, we plan to assess the changes in a selection of inflammatory markers throughout the follow-up as a secondary objective.

Methods

Study design and study population

This study was conducted as a multicenter, randomized clinical trial in five tertiary hospitals in South Korea. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating center (IRB number for Korea University Anam Hospital: 2022AN0127). Written, informed consent was obtained from all enrolled participants. The study was conducted between 15 May 2022 and 1 February 2024. The study was performed in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines.

Participants with a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 130–159 mm Hg and/or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of 85–99 mm Hg by office measurement were assessed for eligibility. The BP criteria were based on the European Society of Cardiology guidelines9. Secondary hypertension or suspicion thereof, liver disease, inability to perform aerobic exercise, current treatment with estrogen or steroids and renal dysfunction were among the major exclusion criteria. The full inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Supplemental table S1.

After initial assessment for eligibility by the investigator, consecutive participants who met all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria were allocated randomly in a 1:1 ratio into either the diet and exercise (D&E) group or the control group (Supplemental figure S1). The randomization process was managed by designated research staff for each site, with blocked access to all others. As it was impracticable to blind the participants to the assigned groups, the primary investigator responsible for the participating patient was blinded to the randomization result, until the completion of the study, for reduction of assessment bias. Randomization was performed at each participating center using computerized block randomization with a block size of 4.

The primary endpoints of this trial were to compare the changes in systolic and diastolic BP by using office BP measurements. The secondary endpoints were to compare changes in 24-hour ambulatory BP, augmentation index, pulse wave velocity, and inflammatory markers such as white blood cell count (WBC), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-18 (IL-18), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1).

BP and laboratory measurements

Office BP was measured using an electronic sphygmomanometer (WatchBP Office AFIB; Microlife, Taipei, Taiwan). The participants rested in a quiet room for at least five minutes prior to BP measurements. For BP measurement, the participants sat on a chair with adjustable heights so that the arm was placed at the level of the heart. BP was measured twice in both arms simultaneously at 2-minute intervals, and the mean value of the two measurements was used. If the difference between two consecutive readings was > 5 mmHg, the measurement was repeated. The arm with higher SBP at the screening visit was designated as the index arm, which was used to measure BP during the follow-up visits. Whole blood samples, collected at baseline and at follow-up, were drawn after overnight fasting of a minimum of 8 hours. Whole blood samples were taken between 7:00 and 8:00 in the morning, and BP measurements were taken between 8:00 and 9:00 in the morning.

The participants were equipped at the index arm with a standard oscillometric device (Spacelabs 90227 OnTrak Ambulatory Blood Pressure monitor, Spacelabs Healthcare, Washington, USA) validated for 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring. Bladder cuff size was adapted to the arm circumference of the patient and positioned at the level of heart, according to ESC guidelines on BP measurement9. 24-hour ambulatory BP measurements were performed every 20 min during daytime, and once per hour at night.

Central BP (CBP) and augmentation index (AIx) were measured using a semi-automated device (HEM-9000AI; Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan). CBP and AIx were calculated from the components of the radial pulse wave, acquired via applation tonometry by measurement of the pressure required to indent the artery. Pulse wave velocity (PWV) was measured using an oscillometry-based device (BP-203RPE III; Omron Colin, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The participants rested for at least five minutes in supine position, and monitor cuffs were wrapped around both upper arms and ankles to give brachial-ankle PWV.

Dietary and exercise intervention

All participants were asked to complete a questionnaire about their dietary habits and physical activities at baseline and after 12 weeks (Supplemental Figure S1). The dietary survey documented the quantities and frequencies of food consumption. The exercise survey enquired about the level of activity required at work and for leisure, and time spent lying down, walking and doing anaerobic and aerobic exercises. Each participant’s basal metabolic rate at baseline and at follow-up were calculated based on age, sex and weight, according to previous literature20. (Supplemental Table S2) Average daily dietary consumption and average weekly activity were estimated based on these survey results.

Between the baseline and final visits, participants in the D&E group visited the clinic at weeks 4 and 8. At each visit, the D&E group were surveyed about food consumption and were educated about the DASH diet and were entered into a 60-minute counselling session on aerobic exercise. Videos on exercise methods were shown, along with provision of booklets on diet and exercise (Supplemental Figure S2). After each session, participants were encouraged to exercise in the facility provided in the clinic, but were also allowed to exit the clinic to exercise at a more comfortable place such as home or another location chosen by the participant. The participants were given a booklet for them to fill in after each exercise, including the time and duration of the exercise, which were brought to the offline sessions for checkups. For better adherence, regular 10-minute phone calls at weeks 2, 6 and 10 were made to the participants in the D&E group to monitor their adherence to the DASH diet and exercise regimens and motivate them to follow the schedules. The prescribed regimen involved engaging in aerobic exercises for a minimum of five days per week for a 12-week period. Each prescribed session lasted 60 min, comprising of 10 min of warm-up, 40 min of aerobic exercise and 10 min of cooling down. Detailed exercise prescriptions are provided in the supplement (Supplemental Table S3).

Statistical analysis

The sample size calculation was based on the assumption that the reduction in 24-hour SBP would be 6 mmHg in the D&E group and 0 mmHg in the control group, based on previous literature15,16. With a standard deviation (SD) of 7, 80% power and on-sided α of 0.05, the sample size was estimated as 23 per group. Assuming a drop-out rate of 15%, a total of 60 (N = 30 per group) participants were planned. However, during the initial phases of the study, dropout rates were higher than expected, so the target number of participants were increased to a total of 70 (N = 35 per group).

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD and categorical variables are reported as the numbers and percentages. Comparisons of the baseline variables were made using the Student’s t-test and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate for categorical variable. A two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to evaluate the effect of the time (before and after intervention) and the effect of time-group interaction. Additionally, subgroup analysis was conducted using ANOVA to examine differences by age, sex, and baseline BP levels. All statistical tests were two-tailed and a p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics

The baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two groups (Table 1). The participants were in mid-50s, and 64% (N = 45) were male. Average BMI was 28.5 kg/m2, which is borderline obesity. Dyslipidemia was the most common comorbidity with a prevalence of 40 (57.1%) participants, and 9 (12.9%) had diabetes mellitus.

BP measurements were comparable between the two groups at baseline. The mean 24-hour SBP and DBP were 133.1 ± 8.3 (D&E vs. control groups, p = 0.162) and 84.7 ± 9.2 mmHg (p = 0.258), and the mean office SBP and DBP were 140.1 ± 7.5 (p = 0.155) and 86.0 ± 8.3 (p = 0.169) mmHg, respectively. Other laboratory tests are summarized in Table 1 and were well balanced between the groups at baseline. No significant adverse events were reported for any of the participants during the entire duration of the study.

Dietary and exercise patterns

At baseline, basal metabolic rate, weight and BMI were similar between the two groups (Table 2). Dietary intake, represented by average daily consumption (4673 ± 1847 vs. 5377 ± 1780 kcal, p = 0.24) and physical activity level, represented by average weekly activity (2940 ± 2651 vs. 4381 ± 3220 METS, p = 0.103) were also comparable between the D&E group and the control group.

At follow-up, basal metabolic rate between the two groups were not significantly different. Body weight (72.1 ± 13 vs. 68.8 ± 13 kg, p = 0.036) and BMI (26.3 ± 3 vs. 25.5 ± 3 kg/m2, p = 0.040) decreased in the D&E group after 12 weeks but the group interaction was not significant. Estimated dietary energy consumption and physical activity level were not significantly different for either group.

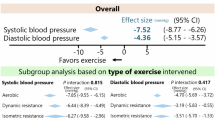

BP effects of diet and exercise

After 12 weeks, the 24-hour ambulatory SBP did not change significantly between the groups (1.1 vs. 2.8 mmHg, pinteraction=0.667). (Table 3; Fig. 1) 24-hour ambulatory DBP did not significantly change (-1.5 vs. 0.9 mmHg; pinteraction=0.421). Similar trends were seen in daytime ambulatory SBP, daytime DBP, and nighttime DBP. (Table 3)

Office SBP decreased significantly in the D&E group at 12 weeks (-8.73 mmHg, p < 0.001), contrary to the control group wherein there was an increase (6.38 mmHg, p = 0.035). (Table 3; Fig. 1) The changes from baseline were significantly different between the groups (between-group difference, -15.1 mmHg; pinteraction = 0.003). Office DBP also decreased in the D&E group and increased in the control group (-4.57 vs. 2.11 mmHg; between-group difference − 4.57; pinteraction=0.017). Changes in CBP, AI and PWV were not significantly different between the groups. (Table 3)

BP analysis by subgroups

Subgroup analyses were performed to differentiate subgroups which may benefit from dietary and exercise intervention. Age was dichotomized by the median age of 55 years. In the younger-age group, there were no differences between the D&E and the control groups at baseline or at follow-up (Table 4). On the contrary, in the older-age group, the baseline office SBP was higher in the D&E group (142.0 ± 6.7 vs. 135.5 ± 5.4 mmHg, p = 0.003), but decreased in the D&E group (-11.9 mmHg, p = 0.002) so the relationship reversed at follow-up such that at 12 weeks, the office SBP was significantly higher in the control group. (130.1 ± 11.8 vs. 142.0 ± 13.9 mmHg, p = 0.022). (Table 4)

Compared with male participants, female participants were also more likely to have a significant change in office SBP (Table 4). The office SBP of male participants for D&E group were 134.9 ± 10 mmHg and 134.9 ± 10 mmHg, respectively for baseline and 12 weeks (p = 0.138). For female participants, while office SBP decreased in the D&E group, it increased in the control group (D&E group, 141.5 ± 7 to 128.8 ± 11 mmHg; control group, 138.1 ± 5 to 152.9 ± 22; p < 0.001). (Table 4) Notably, the 24-hour SBP did not differ significantly in either subgroup, at baseline or at follow-up.

Patients with grade 1 hypertension showed significant difference in follow-up office SBP (132.2 ± 12.9 vs. 145.4 ± 8.0 mmHg, p = 0.014), while neither the 24-hour SBP or office SBP were different at follow-up for the prehypertension group (Table 4). In patients with grade 1 hypertension at baseline, office SBP of the D&E group decreased significantly (143.6 ± 6.9 vs. 132.2 mmHg, p = 0.002) while changing insignificantly in the control group (144.4 ± 7.0 vs. 145.4 ± 8.0 mmHg, p = 0.598).

Inflammatory markers

The inflammatory markers did not show significant changes between baseline and follow-up. VCAM-1 (-45.5 vs. -36.0 ng/mL; p = 0.87), ICAM-1 (-10.1 vs. -13.7 ng/mL; p = 0.88),PAI-1 (-0.74 vs. -3.24 ng/mL; p = 0.56), IL-6 (0.62 vs. 0.45 pg/mL; p = 0.56), IL-18 (-27.9 vs. 8.73 pg/mL; p = 0.17) and TNF-α (-0.01 vs. 0.11 pg/mL; p = 0.31) all showed insignificant changes at week 12 which were not statistically different between the groups (Fig. 2).

Discussion

This randomized controlled study evaluated the effects of dietary and exercise counseling on BP in participants with prehypertension or drug-naïve grade 1 hypertension. The main findings are as follows: (1) office SBP and DBP significantly decreased in the D&E group from baseline to 12 weeks follow-up, with no significant changes in the control group; (2) the change in 24-hour ambulatory SBP and DBP did not significantly differ between the groups after 12 weeks; (3) the inflammatory markers were not significantly different after 12 weeks; (4) the BP-lowering effects were more prominent in individuals who were female, older, and with higher baseline BP. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no large randomized trials have been conducted to test the effects of dietary and exercise intervention in individuals with prehypertension and grade 1 hypertension.

Although the change in 24-hour ambulatory SBP was not significantly different between the two groups, office BP significantly decreased in the D&E group compared to the control group during the 12-week follow-up. Since 24-hour ambulatory BP measurements acquire readings at 20-minute intervals even during the exercise period, BP measurements during and after exercise in the D&E group could inadvertently increase mean BP. Therefore, maintaining a static state for 12-week ambulatory BP measurements was challenging in the D&E group. This study provides valuable insights into the effects of diet and exercise on BP. Firstly, this was a pragmatic trial that tested the effects of outpatient clinic-based educations on diet and exercise on BP management in participants with prehypertension and drug-naïve grade 1 hypertension. Most previous studies providing positive results of diet or exercise on BP management have been conducted in patients with resistant hypertension, as an additive strategy to multiple hypertension medications15,16,21. The difference in participant populations suggests that exercise and dietary restrictions may lower BP better in patients with higher baseline BP. Also, exercise and/or diets may work synergistically with antihypertensive drugs. A meta-analysis on the effects of exercise and medications on BP has demonstrated that physical exercise potentiated the BP effects of antihypertensive medication compared with medication alone22. Notably, office SBP and DBP were significantly lower in the D&E group after 12 weeks, and their respective reductions were also significantly higher compared with the control group. An average BP over the 24-hour period is generally considered a more accurate representation of the patient’s BP, as it is less affected by the white-coat phenomenon and covers the entire duration of the day. However, the significant lowering of well-controlled office BP in the D&E group may indicate a better reflection of real-world clinical practices. The effects of diet and exercise on office BP were more prominent in the older and female participants. The differential manifestations suggest that some population subgroups may benefit more from lifestyle changes than others, or alternatively, that they may be more prone to developing prehypertension or hypertension by leading a sedentary lifestyle. Considering the study design, it is also possible that older and female participants are more sensitive to education or repetitive exposure to information.

BP-lowering effects were also more prominent in patients with grade 1 hypertension, a subgroup with higher baseline BP, although similar trends were seen in the prehypertension group with statistical insignificance. By week 12, both prehypertension and grade 1 hypertension groups exhibited similar office SBPs for the D&E group, suggesting that exercise and diet may show a ceiling effect on the reduction of BP. However, the number or patients per group were relatively small in the subgroup analyses, and previous data on the influence of age and gender on BP reductions by exercise or diet show variations between studies. For elucidation, follow-up studies with larger sample sizes that can adequately examine the effects on subgroups are warranted.

Regarding metabolic status, body weight and BMI showed a statistically significant decrease in the D&E group, with small insignificant increases in the control group. A longer period of observation may point towards acknowledgeable changes in metabolic status, with or without reductions in BP. As weight loss is often associated with reductions in BP, the direction of changes in body weight and BMI affirms the concept central to this study, that education positively exerts an influence on clinical parameters. However, as the p-value for group effect at 12 week and the time-group interaction effect were not statistically significant, larger, longer-term follow-up studies are warranted to validate these findings.

The interplay between inflammation and BP is a complex one, as is the flux of inflammatory markers. In this study, inflammatory markers did not show a significant variation over a 12-week course. Numerous studies have shown, however, that inflammatory marker levels tend to change very slowly. In a 12-week study investigating the effect of physical exercise on inflammatory markers in schizophrenic patients, TNF, IL-6 and CRP did not increase or decrease significantly at the end of the follow-up23. Similarly, administration of anti-inflammatory agents failed to reduce IL-6 and VCAM-1 in young adults with obesity after 1 month24. Conversely, regular exercise was associated with a reduction in IL-6 and CRP levels after 6 and 12 months25. These speculations suggest that a considerable amount of time is required to produce notable anti-inflammatory effects by exercise or diet.

There are a few limitations in this study. First, the sample size calculation may have been underestimated, as there were no prior randomized studies on prehypertensive participants and lifestyle modifications in BP management. The sample size calculation was therefore based on studies on patients with resistant hypertension, who may exhibit larger BP changes than those aiming for primary prevention effects. Second, adherence to the exercise regimes and dietary protocols were available only by patient report, which may have affected the reliability of the data regarding adherence. This study was a pragmatic trial by design, and interventions mostly relied on educational approaches via counseling sessions and telephone follow-ups. Third, compared with previous data on nutrition in Korea, the dietary intake appears to be overestimated26. This may have been due to unrecognized systematic error in designing the nutrition survey paper. In future studies, we aim to thoroughly check the questionnaires so that the answers would more correctly reflect the participants’ lifestyle. Fourth, the multiple counselling sessions and telephone calls in the D&E group may have led to familiarity in the clinic, diminishing the white-coat phenomenon. There is no concrete evidence that healthcare provider-patient contacts effectively diminish patient anxiety, but qualitative research on patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes have suggested that empathy and effective communications with physicians can improve patient outcomes. We hope to consolidate this speculation in a future study. Fifth, the follow-up period may have been too short for the effects to become noticeable. Usually, modifications of lifestyle occur throughout a long period of time. This may have been true especially for inflammatory markers. In conclusion, positive effects on office BP were noted by dietary and exercise education in participants with prehypertension, especially participants who were female, older-aged or with higher baseline BP.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AHA:

-

American Heart Association

- AI:

-

Augmentation index

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- DASH:

-

Dietary approaches to stop hypertension

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- D&E:

-

Diet and exercise group

- ESC:

-

European Society of Cardiology

- PWV:

-

Pulse wave velocity

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

References

Lopez, A. D., Mathers, C. D., Ezzati, M., Jamison, D. T. & Murray, C. J. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 367, 1747–1757. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9 (2006).

Oh, G. C. & Cho, H. J. Blood pressure and heart failure. Clin. Hypertens. 26, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40885-019-0132-x (2020).

Seretis, A. et al. Association between blood pressure and risk of cancer development: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci. Rep. 9, 8565. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45014-4 (2019).

Kim, H. C. et al. Korea hypertension fact sheet 2023: analysis of nationwide population-based data with a particular focus on hypertension in special populations. Clin. Hypertens. 30, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40885-024-00262-z (2024).

Vasan, R. S., Larson, M. G., Leip, E. P., Kannel, W. B. & Levy, D. Assessment of frequency of progression to hypertension in non-hypertensive participants in the Framingham heart study: a cohort study. Lancet 358, 1682–1686. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06710-1 (2001).

Egan, B. M. & Stevens-Fabry, S. Prehypertension–prevalence, health risks, and management strategies. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 12, 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2015.17 (2015).

The Hypertension Prevention Trial. three-year effects of dietary changes on blood pressure. Hypertension prevention trial research group. Arch. Intern. Med. 150, 153–162 (1990).

The effects of nonpharmacologic interventions on. blood pressure of persons with high normal levels. Results of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, Phase I. JAMA 267, 1213–1220, (1992). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03480090061028

Williams, B. et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 39, 3021–3104. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339 (2018).

Whelton, P. K. et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension 71, e13-e115, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065 (2018).

Appel, L. J. et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA 289, 2083–2093. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.16.2083 (2003).

Gambardella, J., Morelli, M. B., Wang, X. J. & Santulli, G. Pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of physical activity in hypertension. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich). 22, 291–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.13804 (2020).

Hutcheson, I. R. & Griffith, T. M. Release of endothelium-derived relaxing factor is modulated both by frequency and amplitude of pulsatile flow. Am. J. Physiol. 261, H257–262. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.1.H257 (1991).

Niebauer, J. & Cooke, J. P. Cardiovascular effects of exercise: role of endothelial shear stress. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 28, 1652–1660. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(96)00393-2 (1996).

Dimeo, F. et al. Aerobic exercise reduces blood pressure in resistant hypertension. Hypertension 60, 653–658. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197780 (2012).

Lopes, S. et al. Effect of exercise training on ambulatory blood pressure among patients with resistant hypertension: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 6, 1317–1323. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2735 (2021).

Xia, H., Zhou, Y., Wang, Y., Sun, G. & Dai, Y. The association of dietary pattern with the risk of prehypertension and hypertension in Jiangsu province: A longitudinal study from 2007 to 2014. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137620 (2022).

Faselis, C. et al. Exercise capacity and progression from prehypertension to hypertension. Hypertension 60, 333–338. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.196493 (2012).

Heffernan, K. S. et al. Resistance exercise training reduces arterial reservoir pressure in older adults with prehypertension and hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 36, 422–427. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.198 (2013).

Human energy requirements. Scientific background papers from the Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation. October 17–24,2021. Rome, Italy. Public Health Nutr. 8, 929–1228, https://doi.org/10.1079/phn2005778 (2005).

Santos, L. P. et al. Effects of aerobic exercise intensity on ambulatory blood pressure and vascular responses in resistant hypertension: a crossover trial. J. Hypertens. 34, 1317–1324. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000000961 (2016).

Pescatello, L. S. et al. Do the combined blood pressure effects of exercise and antihypertensive medications add up to the sum of their parts? A systematic meta-review. BMJ Open. Sport Exerc. Med. 7, e000895. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000895 (2021).

Bigseth, T. T. et al. Alterations in inflammatory markers after a 12-week exercise program in individuals with schizophrenia-a randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychiatry. 14, 1175171. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1175171 (2023).

Fleischman, A., Shoelson, S. E., Bernier, R. & Goldfine, A. B. Salsalate improves glycemia and inflammatory parameters in obese young adults. Diabetes Care. 31, 289–294. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc07-1338 (2008).

Gondim, O. S. et al. Benefits of regular exercise on inflammatory and cardiovascular risk markers in normal Weight, overweight and obese adults. PLoS One. 10, e0140596. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140596 (2015).

Yun, S., Kim, H. J. & Oh, K. Trends in energy intake among Korean adults, 1998–2015: results from the Korea National health and nutrition examination survey. Nutr. Res. Pract. 11, 147–154. https://doi.org/10.4162/nrp.2017.11.2.147 (2017).

Funding

This trial has been supported by the Korean Vascular Society (KOVAS). KOVAS had no involvement in the trial’s design, data collection, or data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. Methodology, Investigation, writing of original draft; S.J.H. Supervision, Conceptualization, Reviewing and editing of Original Draft; J.H.K. and J.J.C. Methodology, Investigation, Software; H.J.J., J.H.P., C.W.Y., and D.S.L. Validation, Visualization, Data Curation; and J.H.S., J.Y.L., Y.H.L., S.H.K. and K.C.S. Funding Acquisition, and Resources. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, S., Hong, S.J., Kim, J.H. et al. Dietary management and aerobic exercise counselling on blood pressure control in subjects with prehypertension and drug-naïve stage 1 hypertension: a randomized clinical trial. Sci Rep 15, 45683 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20828-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20828-7