Abstract

Mammography is a routine imaging technique used by radiologists to detect breast lesions, such as tumors and lumps. Precise lesion detection is critical for early treatment and diagnosis planning. Lesion detection and segmentation are still problematic due to inconsistencies in image quality and lesion properties. Hence, this work presents a new Multi-Stage Deep Lesion model (MSDLM) for enhancing the efficacy of breast lesion segmentation and classification. The suggested model is a Three-Unit Two-Parameter Gaussian model with U-Net, EfficientNetV2 B0, and a domain CNN classifier. U-Net is utilized for lesion segmentation, EfficientNetV2 B0 is employed for image deep feature extraction, and a CNN classifier is used for lesion classification. The MSDLM feature cascade is designed to enhance computational efficiency while retaining the most relevant features for breast cancer detection and identifying the minimum number of features most important in the detection and classification of breast lesions in mammograms. The Multi-Stage Deep Learning Model (MSDLM) was validated using two benchmark datasets, CBIS-DDSM and the Wisconsin breast cancer dataset. Segmentation and classification tasks were indicated by accuracy values of 97.6%, indicating reliability in breast lesion detection. Its sensitivity of 91.25% indicates its reliability in detecting positive cases, a basic requirement in medical diagnosis. It also indicated an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 95.75%, indicating overall diagnostic performance irrespective of thresholds. The Intersection over Union (IoU) of 85.59% verifies its reliability to detect lesion areas in mammograms. MSDLM with a Gaussian distribution provides precise localization and classification of breast lesions. The MSDLM model allows for improved information flow and feature refinement. The algorithm outperforms baseline models in both effectiveness and computational cost. Its performance on two diverse datasets verifies its generalizability and enables radiologists to receive exact automated diagnoses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

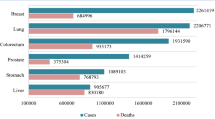

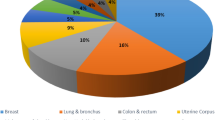

Cancer is the primary cause of mortality worldwide, exceeding all other illnesses. The latest official data shows that breast cancer is now more common than lung cancer. Breast cancer is the primary cause of cancer mortality among females. By 20261, breast, bowel, and lung cancers will be the most frequently diagnosed kinds of cancer in American women. Since peaking in 19892, the incidence of breast cancer deaths in women has decreased by 43%. The annual decrease in breast cancer mortality fell by approximately 2–3% in the 1990 s to 1% in 20243. Non-invasive breast cancer may remain localized inside a particular organ or structure, such as a duct or lobule, without spreading to distant tissues4,5. Experts currently recognize the combination of ultrasonography, thermography, and mammography as the most effective method for breast cancer detection. One study revealed that clinicians review medical imaging, such as CT scans, every three to four seconds throughout an eight-hour shift6. Consequently, errors in analysis and inaccurate study results sometimes occur due to the average lack of sufficient time for analysis and fatigue from lengthy workdays7. A comprehensive method is used to identify breast lesions, typically in conjunction with imaging scans and a biopsy, to determine the nature and severity of the lesions. The wide range of breast pathologies includes neoplasms that have emerged from different types of cells, with dissimilar patient prognosis, treatment, and diagnostic methods8. Neuro-oncology research discovery presents new avenues for more effective diagnostic techniques and therapeutic interventions for patients with the challenge of extreme disturbances in the delicate structure of the human body. Transfer learning (TL), a machine learning method, has gained widespread interest in medicine due to its capacity to utilize pre-trained models constructed using large databases for a specific aim9. Various transfer learning architectures, including VGG, ResNet, Inception, MobileNet, and DenseNet10, are highly effective in this area.

Transfer learning methods are used to identify intricate patterns in medical images by tapping into the depth and complexity of neural network models. This adaptable method goes beyond these established models, as several other models contribute to the growing list of medical image assessment11. The rapid development path and increased performance and accuracy of pre-trained models, aided by transfer learning in medical images, enable faster and more accurate diagnoses of cancerous lesions12. This application is particularly relevant to the detection and identification of cancerous lesions. Transfer learning model operating efficiencies have a significant impact on patient care, as timely and personalized treatment options depend on early detection and precise identification of cancer types. The application of these technological developments may enhance patient outcomes, transform medical diagnostics, and enhance the capability of healthcare professionals.

Our study employs the MSDLM model, which is a hybrid of the EfficientNetV2 B0 model and the Gaussian U-Net and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model. The MSDLM model has significantly improved medical image analysis, resulting in substantial advancements in diagnosing, characterizing, and detecting a wide range of medical conditions. This is achieved by combining computing efficiency and a feature cascade to gather more information in a shorter time. This has made it possible for medical practitioners to make more educated choices, especially when it comes to correctly classifying cancer kinds, including lung and breast cancer. Better treatment choices, earlier diagnosis, and better patient outcomes have all been made possible by this MSDLM.

The MSDLM model is essential for surgical planning because it enables the accurate segmentation of breast lesion boundaries, thereby balancing intervention with the preservation of quality of life. Customized screening techniques enable individualized patient guidance and effective follow-up strategies by predicting potential problems, recurrence rates, and therapeutic responses. Our paper’s primary contribution is the novel classification method we developed for breast lesions, which categorizes them into two groups using MR images by applying transfer learning and fine-tuning. The research utilizes the GaU-Net network to develop a model for breast cancer classification using ultrasound images.

The objectives are to improve image recognition and provide clinicians with supplementary information.

-

This proposal introduces an MSDLM model to enhance the detection of breast lesions in CBIS-DDSM and Wisconsin images. The combination of the major features of the Gaussian U-Net and EfficientNetV2 B0 enhances the method’s efficiency in detecting and classifying lesions.

-

A Gaussian U-Net stacking model, combined with EfficientNetV2 B0 for feature learning and a CNN for classification, enhances the segmentation accuracy of breast lesions compared to existing models. The approach outperforms existing models according to dataset evaluation metrics.

-

The Probability Density Function resolves memory concerns in the hybrid Gaussian U-Net, EfficientNetV2 B0, and CNN architecture.

-

Input images are fed into a Gaussian U-Net to detect malignant breast cancers, utilizing EfficientNetV2 B0 for feature extraction and CNN classification, as well as a comparison of cancer detection techniques.

Literature review

To improve understanding of previous research on the current proposed model and its effectiveness concerning datasets and other performance indicators, a few previous studies are outlined in Table 1, including the classifier employed, the dataset details, and the accuracy attained by those previous models.

A detailed graphical representation is presented in Fig. 1 to facilitate a better understanding of the existing works. Very few researchers have investigated the detection of breast lesions utilizing a combination of GaU-Net and EfficientNetV2 B0, together with a CNN for classification, according to the currently available works. To improve the identification and classification of breast lesions from the selected mammography dataset, however, more precise segmentation and classification are necessary. Some of the earlier works that presented the tumor identification with different types of datasets and their performances are discussed. In13, the authors utilized the basic CNN model to identify and classify breast lesions from the CBIS-DDSM dataset, achieving an accuracy of approximately 79.8%. In14, the authors combined the CNN model with other ConvNets for the precise identification of breast tumors using the BraTS-2013 dataset. They achieved an accuracy of 94% in identifying and classifying breast tumors in human breast images. In15,16, the authors utilized the Water U-Net and CNN algorithm to classify breast lesions from a dataset chosen by the authors, specifically the CBIS-DDSM dataset. The authors achieved 95.2% and 96.1% accuracy in classifying the affected scanned images from the total set of scanned images. In17, the authors utilized the 3DU-Net model to classify the presence of breast lesions in the selected input data provided to the model. To compare the performance of the suggested model, the researchers made an evaluation on the BraTS 2020 dataset, which was utilized for breast lesion detection. Using the same approach, the researchers achieved an accuracy level of around 86%, as well as a much longer processing time. In18, the authors introduced a hybrid model that integrated a CNN model with the Gaussian algorithm for classifying breast lesions from a chosen scanned image dataset. The authors’ chosen dataset was TCIA, and it achieved an accuracy of 94.57%, which was satisfactory compared to other available models.

In19, the authors proposed a hybrid model that combines both ResNet and InceptionV2 for detecting breast tumors from the scanned input images. The CVC Clinic-DB dataset was used to test the performance of this hybrid model, achieving an accuracy of 91.2%, which is a good output compared to other existing proposed models. If we see all these existing models, the performance of the individual model is much less compared to the performance of a hybrid model in the detection of tumors. Therefore, a hybrid model is necessary to achieve better accuracy in breast lesion identification and to obtain a good output within a faster execution time interval.

To accomplish these problems, we had proposed a propose a MSDLM model to enhance breast lesion diagnosis, which comprises of combining the GaU-Net for segmenting input images as the first layer of the proposed model, the other EffiicientNetV2 B0 model for feature extraction from the segmented images as the second layer of the proposed model and a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) as the final third layer of the proposed model for classification of breast lesions from input images. Overall, pairing the Gaussian Distribution with the U-NET design is a helpful way to make seeing breast lumps in medical images easier. The study review examines how effectively the Gaussian U-Net preserves spatial properties and the importance of the Gamma Distribution in addressing the natural pixel density variations of breast tissue. When you combine statistical models, such as the Gaussian distribution, with deep learning frameworks like U-Net, it may be possible to make breast mass separation methods significantly more accurate and reliable.

Materials and methodology

This section delineates the many resources and methodologies employed in the suggested model within the current study.

-

Data Collection.

The CBIS-DDSM holds 3220 scanned film images of the breast. Images of the benign class are selected from the database, comprehensively representing various breast conditions. The images are carefully labeled to enable proper training and testing of the proposed segmentation model. The database is designed to meet the necessary requirements for proper breast lesion identification and segmentation, which is crucial for effective diagnosis and treatment planning. The chosen database provides a solid foundation for constructing a highly accurate and reliable segmentation system. The high number of images in this collection allows the proposed model to learn and generalize across lesions of various types and anatomical variations, hence improving its performance and clinical applicability.

-

Data Pre-Processing.

Data preprocessing is a critical phase in the development process of the proposed model, ensuring that the scanned film images are normalized and prepared for proper analysis. The initial step is to resize the images to a uniform size, which helps provide equal input to the model. Noise reduction methods, such as Gaussian filtering, are employed to enhance image quality by eliminating unnecessary artifacts. Contrast normalization is also performed to standardize the intensity values of all images, thereby simplifying the model’s ability to detect significant features. The spatial information after preprocessing the image is shown in Fig. 2.

Following these early steps, image enhancement methods such as flipping, rotation, and scaling are applied to give more information. This exposes the model to a wide range of conditions, thus making it robust.

-

Data normalization.

Normalization is adjusting the values of a particular property to conform to a more restricted range, often between − 1 and 1 or 0 and 1. Normalizing characteristics is crucial to prevent mistakes in data modelling due to scale discrepancies. This guarantees that all characteristics maintain a uniform scale.

-

Data Augmentation.

Data augmentation is one of the primary methods of supporting and supplementing training sets, thus helping deep learning models. It is a method that creates new data points from primary data points. We can accomplish this by making minor adjustments to the primary data or by generating new data through alternative means. By making more examples available for the training set, data augmentation helps machine learning models become more precise and work better. A large and diverse dataset is crucial in helping these models perform well and achieve higher levels of accuracy.

-

U-Net.

The U-Net model is characterized by a two-path architecture that is defined uniquely, skillfully combining expansive and contracting paths. Within the contracting path, the encoder layers carefully extract the important information while simultaneously reducing the input data size. This part of the U-Net plays a crucial role in identifying the most significant features of the input image. The encoder layers effectively reduce the feature map size through convolution operations, while simultaneously increasing the depth of detail and constructing deeper representations of the input.

This contracting pathway resembles the feedforward layers found in other convolutional neural networks. Conversely, the expansive approach focuses on decoding the encoded data and identifying characteristics while preserving the spatial resolution of the input. The decoder layers in the extended route upsample feature maps and execute convolutional operations. The skip connections from the contracting path help retain the spatial information lost during the contracting phase, thereby enhancing the decoder layers’ ability to reliably identify features. The architecture of the U-Net model is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Gamma distribution for U-Net

In order to increase the effectiveness of the segmentation, the architecture of the MSDLM is enhanced using a Three-Unit Two-Parameter Gaussian Model as an auxiliary module. The module is significant when eliminating noise, improving edge definition, and maintaining important feature structures, specifically in mammographic images, in which the edges of lesions are weak and unclear. Each unit in this sequence continuously integrates the feature maps in terms of emphasizing the regions of interest (ROI), suppressing the background noises, and augmenting boundary information.

The three units’ outputs are summed up and fed into a 1 × 1 convolutional layer, aiming at decreasing the data dimensions and optimizing integration efficiency.

This Gaussian refinement module is positioned strategically in between important stages of the U-Net decoder and creates connectivity with EfficientNet and with CNN branches using residual skip connections. The structure encourages the maintenance of consistency in features among various models while enabling flexibility in the MSDLM architecture. Equation 1 illustrates the working dynamics of the Three-Unit Gaussian module with other components of deep learning. The architecture allows for the possibility of enhancing the accuracy of segmentation, with special reference to discrimination between the malignant and the benign lesions, wherein the precision in the details at the pixel level is quite significant.

The images are classified into three types from the existing image segmentation models with distribution models20,21,22., Authors are used for some complex images, like boundary conditions, low intensity, and edge detection. These sorts of images were present primarily in medical and biomedical applications. For predicting or analyzing the content on these sorts of images, the single-parameter functional distributions are insufficient for full-scale identification and for predicting the evaluation performance metrics. A mixture of distribution models with other new algorithmic models is needed for better accuracy and more accurate predictions of the content in images. The current section offers a thorough analysis and clarification of the Expectation and Maximization approach23,24,25, which determines the model’s parameter values. The specific attributes of an image are defined by the varying intensities of the individual pixels located inside its separate areas. The current presentation showcases a model that uses the gamma distribution to mimic the brightness of individual pixels in different image areas.

l- is the location parameter, m-shape parameter, p,l, m,k are the gamma variants.

A group of various regions of a full image can be characterized using the gamma distribution. Hence, the assumption to be followed here is that the full image’s various pixel intensities follow a k-component mixture of the gamma distribution, and its probability density function is in the form.

Where k is the number of regions \(\:0\le\:{\alpha\:}_{i}\le\:1\) are weights such that \(\:\sum\:{\alpha\:}_{i}=1\) and \(\:{f}_{i}(y,\mu\:,{\sigma\:}^{2})\) is given in Eq. (1). \(\:{\alpha\:}_{i}5uyy\)is the weight associated with ith region in the whole image.

The mean pixel intensity of the entire image is

.

Estimation of model parameters:

The updated equations of the model parameters are obtained for the Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm.

The likelihood of the function of the model is,

This implies

.

Where \(\:\varvec{\uptheta\:}=({\varvec{\upmu\:}}_{\mathbf{i}},{{\varvec{\upsigma\:}}_{\mathbf{i}}}^{2},{\varvec{\upalpha\:}}_{\mathbf{i}};\mathbf{i}=\text{1,2},................\mathbf{k})\) is the set of parameters.

Therefore

The expectation value of log \(\:\mathbf{L}\left(\varvec{\uptheta\:}\right)\) with respect to the initial parameter vector \(\:{\theta\:}^{\left(0\right)}\) is

Given the initial parameters\(\:{\theta\:}^{\left(0\right)}\). One can compute the density of pixel intensity y as

This implies

The conditional probability of any observation xs, belongs to any region ‘k’ is

The expectation of the log-likelihood function of the sample is

.

But we have

.

Following the heuristic arguments, we have,

To obtain the estimation of model parameters, one must apply the standard solution method for constrained maximum by constructing the first-order Lagrange type function.

Where \(\:\lambda\:\) is the Lagrangian multiplier combining the constraint with the log-likelihood functions to be maximized.

The mean of gamma distribution:\(\:{\mathbf{m}}^{2}\frac{\varvec{\Gamma\:}\left(\mathbf{p}+\frac{2}{\mathbf{k}}\right)}{{\left[\varvec{\Gamma\:}\left(\mathbf{p}\right)\right]}^{2}}=\frac{\varvec{\Gamma\:}\left(\mathbf{p}+\frac{1}{\mathbf{k}}\right)}{{\left[\varvec{\Gamma\:}\left(\mathbf{p}\right)\right]}^{2}}\)

And ith moment of location parameter \(\:{\mathbf{m}}^{\mathbf{k}}\frac{\varvec{\Gamma\:}\left(\mathbf{p}+\frac{\mathbf{i}}{\mathbf{k}}\right)}{{\left[\varvec{\Gamma\:}\left(\mathbf{p}\right)\right]}^{2}}\).

This implies

.

This implies

.

Summing both sides’ overall observations, we get \(\:\lambda\:=-N\).

Therefore, \(\:{\varvec{\upalpha\:}}_{\mathbf{i}}=\frac{1}{\mathbf{N}}{\sum\:}_{\mathbf{s}=1}^{\mathbf{N}}{\mathbf{P}}_{\mathbf{i}}({\mathbf{y}}_{\mathbf{s}},{\varvec{\uptheta\:}}^{\left(\mathbf{l}\right)})\)

The updated equations of\(\:{\alpha\:}_{i}\) for \(\:(l+1{)}^{th}\)iteration is

.

This implies

Taking the partial derivative with respect to\(\:\:{\mu\:}_{i}\), we have

After Simplifying, we get

Therefore, the updated equations of \(\:{\mu\:}_{i}\) at \(\:(l+1{)}^{th}\)iteration is

For updating \(\:{{\sigma\:}_{i}}^{2}\) we differentiate \(\:Q(\theta\:,{\theta\:}^{\left(l\right)})\) with respect to \(\:{{\sigma\:}_{i}}^{2}\) and equate it to zero.

That is \(\:\frac{\partial\:}{\partial\:{\sigma\:}^{2}}\left(Q\right(\theta\:,{\theta\:}^{\left(l\right)}\left)\right)=0\).

This implies \(\:E\left[\frac{\partial\:}{\partial\:{\sigma\:}^{2}}\left({log}L\right(\theta\:,{\theta\:}^{\left(l\right)}\left)\right)\right]=0\).

Taking the partial derivative with respect to \(\:{{\sigma\:}_{i}}^{2}\)

This implies.

-

EfficientNetV2-B0 Architecture.

EfficientNetV2-B026 is a pre-trained convolutional neural network (CNN)27 architecture optimised for effective image categorisation. It belongs to the EfficientNetV2 lineage, which enhances the original EfficientNet design by using novel methodologies to augment performance and efficiency.

The modified architecture of the EfficientNetV2-B0 is represented in Fig. 4 for better understanding by users.

-

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs).

The typical CNN architecture comprises several layers that are necessary for its operation. These layers begin with convolutional layers, which employ filters to extract information from the input image. An activation function, such as the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU)28, is typically applied after each convolutional layer. This activation function introduces non-linearity into the model, enabling it to recognize complex patterns. Pooling layers, which help downsample the feature maps, are utilized to minimize the spatial dimensions of the data while preserving essential information. The utilization of max pooling accomplishes this. Here, we elaborate on the proposed approach for segmenting, feature extracting, and classifying breast tumors. Figure 5 displays the workflow of the suggested method.

-

Proposed Model.

The proposed MSDLM model is further discussed in the subsequent sub-sections. Following a sequence of convolutional and pooling layers, CNN architecture often progresses to fully connected layers, wherein high-level reasoning occurs. The terminal layer is a Softmax layer29,30 that generates a probability distribution across several classes, thereby facilitating the model’s predictive capabilities. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) excel in image-related tasks because they can learn spatial hierarchies of features, initially capturing low-level patterns such as edges and textures, and progressively amalgamating them into more abstract representations, like shapes and objects, in the deeper layers. This design has resulted in substantial progress in computer vision applications, encompassing image categorization, object identification, and segmentation. The suggested model architecture is illustrated in Fig. 6.

The proposed MSDLM model incorporates a stacking architecture that combines GaU-Net for segmenting the input images, the EfficientNetV2-b0 model used for extracting the features from the segmented images, and a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for classification.

The model assigns greater weight to the most important features of the input images. The model identifies focal regions, thus enhancing the visibility of tumor regions and removing irrelevant background information.

EfficientNetV2-b0 is renowned for its high efficiency when operating on high-dimensional data, leveraging factorized convolutions to extract deep features across a wide range of scales. EfficientNetV2-b0 significantly improves the model’s ability to detect immense quantities of features in images derived from scanned films, which is a critical factor when distinguishing among different types of breast lesions.

The CNN classifier is used for classifying the extracted features. It is comprised of several fully connected layers that utilize the high-level extracted features of Inception V3 and Attention U-Net, all the way to the last SoftMax layer, which generates the probability distribution of the four tumor types.

-

Performance Evaluation Metrics.

A confusion matrix was developed to visualize the model’s classification performance across different lesion types, like malignant and benign. Additionally, the Intersection over Union (IoU) was calculated to evaluate the degree of overlap between the predicted segmentation masks and the reference masks used. Using these criteria, a comprehensive understanding of the model’s efficiency in properly segmenting and categorizing breast tumors from scanned film images was obtained.

Result analysis and discussions

Mammography accurately identifies breast masses using scientific methods31,32. Each image in the dataset is first enhanced by eliminating noise and improving its distinct quality before editing. Subsequently, every image is altered. The recommended U-Net with Gaussian distribution trained segmentation models on the CBIS-DDSM were tested. Our proposed approach surpasses other segmentation algorithms and previous studies.

-

Experimental Setup Used for Implementation.

Each test used the following equipment: a 16GB RAM module, a 2.80 GHz Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-7700 central processor unit, and NVIDIA GTX 1050Ti graphics cards. Training and testing segmentation models on the CBIS-DDSM dataset. This research utilizes the Python programming language and the ImageDataGenerator module from the Keras framework to create collections of mammography images.

-

Training Procedure.

The model was trained using a robust strategy involving data augmentation techniques to increase the diversity of the training dataset. Techniques such as random rotations, horizontal and vertical flips, and random brightness adjustments were applied to enhance the model’s robustness against overfitting. The dataset was divided into 80% training, 10% validation, and 10% testing subsets to ensure that the model was adequately trained and evaluated on unseen data. The training employed a cross-entropy loss function specifically designed for multi-class segmentation tasks. Early stopping was implemented to prevent overfitting by monitoring the validation loss during training.

-

Exploratory Data Analysis.

Data visualization is an alternative technique employed to understand data. Data visualization enables us to see the presentation of data and the correlations among its aspects. This process allows the output to be verified against the features in the minimal time feasible.

Plot distribution for various attributes

The distribution of a dataset is graphically depicted in a distribution plot, which compares the actual distribution of the dataset with the expected theoretical values according to a predetermined distribution. You can see the spread and variation in a numerical dataset with a distribution graphic. Depending on your needs, you may display this graph in one of three ways: with only the value points showing the distribution, the bounding box showing the range, or a combination of the two. Figure 7 displays the distribution plots of the attributes from the dataset used in this study. A histogram is typically the best choice for displaying dispersion. We may see how often specific values occur by dividing the data into uniform intervals or classes. Using this method, we can learn how the quantitative data is distributed probabilistically.

Analysis of features and their CO-relation

A heatmap is a visual depiction where the values of a matrix are represented through colors. A heatmap is particularly effective for visualizing data concentration inside a two-dimensional matrix. Correlation analysis allows us to determine the degree of association between two variables. Correlation analysis involves calculating the correlation coefficient, which indicates the degree to which one variable changes in connection with another, and vice versa. In Fig. 8, each value in the dataset is shown by a distinct color within a two-dimensional matrix. A basic diagonal heatmap enables individuals to gain a thorough understanding of the data. Two-dimensional cell values over zero indicate a positive correlation between qualities, whereas values below zero reflect a negative correlation between attributes. A lighter hue indicates a greater negative association, whereas a deeper hue signifies a higher positive correlation, as shown in the heatmap. Figure 9 outlines the Regression plots of the pairs derived from the correlation heatmap, with correlations to target classes in Fig. 10.

Outlier detection

In the exploratory data analysis phase of data science project management, a model’s effectiveness in addressing a business challenge depends on its ability to handle outliers proficiently. Managing outliers is a crucial aspect of this phase. Data points are classified as “outliers” when they do not conform to the characteristics of the remaining dataset. The most prevalent type of outlier is one that is markedly far from most observations or the data’s mean. When limited to one or two variables, it is straightforward to represent the data using a basic histogram or scatter plot. Nonetheless, the task becomes significantly more challenging in the presence of a high-dimensional input feature field. In training machine learning algorithms for predictive modelling, it is crucial to detect and remove any outlier data points. Outliers can distort statistical measures and data distributions, obscuring the fundamental characteristics of the data and the connections among the variables. Enhancing the fit of the data and, consequently, the accuracy of predictions is achievable by preprocessing the training data to eliminate outliers. Figure 11 illustrates the outlier identification technique applied to the Wisconsin breast cancer dataset used in this investigation.

Following the recent study conducted by33 that utilized the Wisconsin Breast Cancer Dataset (WBCD) based on classification with various features, as well as the CBIS-DDSM dataset, to analyze mammographic images, the current study employs a similar methodology framework to enhance the model’s robustness. The classification module was trained and validated using the WBCD with regard to well-structured cellular-level features, while the CBIS-DDSM dataset was utilized to perform segmentation and high-resolution mammography-lesion localizations. Through the use of two such datasets, the study provides comprehensive decision support, as well as image-based interpretability, that enables the holistic diagnosis of breast cancer.

Performance indicators

The performance indicators for the suggested approach underscore its capability for precise and swift detection and classification of target items. The training phase endures for 21 min and 4689 s, but the testing phase concludes in 31 min and 3661 s, demonstrating exceptional efficiency. The swift processing time renders our approach ideal for real-time applications. Object boundaries are defined by a Dice Coefficient (DSC) of 85.06% and an Intersection over Union (IOU) of 97.12% at a threshold of 0.55, demonstrating strong segmentation performance. The model achieves 96.36% accuracy with a recall rate of 90.52%, demonstrating its accuracy and reliability. It is also 94.40% globally accurate in the classification tests. The AUC-ROC of 95.75% indicates that it can effectively distinguish among different classes. The results presented in Figs. 12 and 13, and 14 show that our semantic segmentation method achieves greater efficiency and reliability, thereby providing a valuable resource for different applications.

The outcomes highlight the improved sensitivity and specificity of the hybrid model utilized, an aspect that is most critical in medical environments where accurate tumour detection has far-reaching consequences for treatment. The metrics for performance reflect the success in using DeepLabV4, Inception V3, and CNN for the accurate segmentation and classification of breast tumors.

The enhanced precision not only raises the level of diagnostic accuracy but also can enhance the treatment outcome by ensuring proper and complete tumor segmentation. Its integration into practice will enable oncologists and radiologists to make well-informed decisions, thereby enhancing patient care.

Figure 12 presents the confusion matrix for breast cancer classification using the above-discussed segmentation-based model, providing a precise illustration of the classification results. It distinguishes between benign samples, labeled as 0, and malignant samples, labeled as 1. True labels are represented along the x-axis and predicted labels along the y-axis in this matrix, where correct classifications are noted on the diagonal and incorrect classifications are noted in the off-diagonal elements. misclassifications.

Figure 13 (a) and (b) represent the accuracy and model IoU graph over 05 epochs, showing a steady increase in training and validation accuracy, indicating consistent learning and improvement in the model’s performance.

Figure 14 (a) and (b) display Model Loss for training and validation data, providing insights into the model’s performance across different classification thresholds. Model Loss and IoU, providing insights into the model’s performance across different classification thresholds.

Figure 15 displays precision-recall and ROC curves, providing insights into the model’s performance across different classification thresholds. These curves are crucial for evaluating the trade-off between precision and recall, as well as for assessing the model’s discriminatory ability across various decision boundaries. The ROC curve was constructed from non-threshold probability scores of the last sigmoid activation layer of the model, rather than threshold binary outputs. This allowed continuous performance evaluation at any classification threshold. With probability outputs, the ROC curve actually displays the discriminative ability of the model, and its AUC of 95.75% ensures its stability.

A side-by-side visual comparison of ultrasound images of benign, malignant, and normal breast pathology is provided. Each row is a different category: benign at the top, malignant in the middle, and normal at the bottom. The columns are (i) the original ultrasound image, (ii) the corresponding segmentation mask in bold red, and (iii) the marked boundary of the mask in red as well. This overlay and boundary presentation enables easier visual assessment of tumor localization and segmentation quality across the different pathological types.

Figure 16 illustrates the performance of the proposed model in segmenting breast tumors with high accuracy, as indicated by the Intersection over Union (IoU) score. The IoU measure approximates the overlap of the predicted tumor region and the corresponding ground truth. A value close to 1 represents a high-precision prediction, while a low value indicates variations between the predicted and actual tumor boundaries. The IoU measure is approximated by calculating the overlapping region of the predicted and real tumor areas and dividing it by their union area. The measure is used to confirm the effectiveness of the model in segmentation, a consideration of high significance in medical diagnostics, since even slight errors can lead to incorrect treatment plans. The high IoU value obtained confirms the model’s high capability in tumor detection. Additionally, the performance of the suggested model is compared to that of other models, with detailed information provided in Table 2.

The Comparison of tumor image segmentation models reveals different levels of performance among various architectures, as shown in Fig. 17. The two-dimensional U-Net on INBreast achieved an 81% accuracy, constrained by the inability to retrieve 3D data features. M-SegSEUNet-CRF on CBIS-DDSM achieved 0.851 ± 0.071%, with minimal instability in accuracy. The DC-U-Net model achieved 81.41%, indicating a need for improvement. The SCCNN model on Br35H achieved 95.45%, with the addition of semantic features for enhanced segmentation26. CNN with GANs achieved 93.9%, indicating GANs’ ability to enhance results, but still trailing behind U-Net-based models. The proposed model on CBIS-DDSM and Wisconsin surpasses all others with 97.6% accuracy, indicating its enhanced ability for breast tumor segmentation compared to other existing segmentation models.

The top panel of Fig. 18 shows the original mammographic images of the CBIS-DDSM (INbreast) dataset. The middle panel shows the enhanced representations of malignant and benign tumors from the original images. The bottom panel displays the output of our Multiscale Deep Learning Model (MSDLM), and the results are positive when compared to another benchmark model, indicating the positive impact of texture on the results.

Figure 19 shows the increase in training accuracy across 7 iterations from 77.75% at epoch 0. The model’s accuracy increases rapidly, reaching 93.05% at epoch 1, and continues to improve thereafter. From epoch 2, the accuracy plateaus at above 97%, reaching a peak of 98.85%. This upward trend indicates that the model is improving, becoming increasingly effective at eliminating false positives during training and delivering stable, consistent performance in classification.

Training accuracy in Fig. 20 shows a steady increase through epochs, from 77.75% to over 97% by epoch 2. It then levels off at around 98.85%, indicating the model’s ability to learn true positives with very high precision and a low number of false positives. The steady increase and then leveling off trend indicates a strong learning capacity and consistent accuracy throughout the learning process.

Figure 21 illustrates a steep and significant increase in training recall, which moves from its initial position of 77.75% at epoch 0 to a remarkable 93.85% by epoch 6. This significant change indicates that the model is making substantial strides towards accurately identifying true positives, which means there are fewer false negatives. Accordingly, this increase demonstrates that the model is becoming increasingly sensitive and responsive to the target class as it continues training.

Figure 22 shows that the training loss drops significantly, from its initial value of 0.4827 at epoch 0 to a low of 0.0317 at epoch 6. The steady decline indicates that the model is learning well, hence minimizing prediction errors and improving its convergence with the training data incrementally. The steep decline for the first few epochs indicates a fast convergence rate.

The model is highly generalizable, achieving an accuracy of 97.60%, precision of 94.50%, and recall of 97.25%, which indicates a high detection rate of positive classes with minimal false positives and false negatives. The high IoU value of 85.59% indicates a high overlap between the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes, and the low loss value of 0.0893 indicates a low prediction error. The result in Fig. 23 confirms the robustness and reliability of the proposed model when applied to new data.

-

Feature Analysis on MSDLM Model.

This part outlines the 34 features’ embeddings, wrap, and filtering according to the semantic image segmentation process. The datasets, such as the CBIS-DDSM and Wisconsin images, were selected according to their inherent features. The performance of the feature subset was tested and verified using the testing and validation protocols of the CBIS-DDSM and Wisconsin images. Thirty-five feature subsets were tested. The used MFCCs and the outputs resulting from them are part of the dataset. The full set of features is utilized from ten to twenty times using the 34 features. Additional information related to the MFCC is presented in Table 3. Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficient (MFCC) is an integral part of almost all biomedical classification models. It is also a summary of the most significant principles of medical imaging sampling.

An RFE algorithm implementation of recursive function elimination was facilitated by calling the RFE class of the PySklearn image library. Two parameters, an independent estimator and the number of source functions that an estimator can use, define two parameters to be set. The stopover parameter, which specifies the number of features at which a user would like to stop, is also defined. Our investigation retained only the features that were found to be most effective in identifying the top 13, 14, and 15 features for models 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Table 2 indicates the performance metrics of the models. Features of the RFE class are selected based on the support they offer, and the resulting indices of the selected features are the most useful. Table 3 presents the MFCCs for each model, along with the indices of the 14 most useful features selected using RFE for each model.

Discussions and limitations

Recent research has explored multiple imaging modalities and computational methods to enhance early breast cancer detection. Thermography has been investigated extensively for its ability to detect abnormal heat patterns associated with malignancies, offering a non-invasive complement to traditional mammography34. Advanced optical sensing techniques, such as porous silicon Bragg reflector-based Raman spectroscopy, have been proposed for precise molecular-level detection of breast cancer35. Deep learning methods have also been applied to ultrasound imaging, enabling fast super-resolution microvessel visualization and improving the detection of subtle vascular features in lesions36. Inception-based convolutional networks have been utilized for thermal image analysis, demonstrating improved performance in early cancer detection37. Adaptive multi-scale feature fusion networks have been shown to enhance classification accuracy in medical imaging, including diabetic retinopathy, indicating their potential for complex feature learning38. Transformer-based weakly supervised approaches have further advanced automated pathology analysis, enabling clinically relevant diagnosis and molecular marker discovery39. Infrared camera-based deep learning frameworks support self-detection of early-stage breast cancer, emphasizing real-time, patient-friendly applications40, while the influence of tissue thermo-physical properties and cooling strategies on detection has also been highlighted41. Explainable ensemble learning has been applied in OCT imaging, reinforcing the value of interpretable AI models for accurate lesion classification42. Studies on homologous recombination repair deficiency provide insights into molecular profiling that can guide predictive modeling in breast cancer43,44. Deep learning approaches for ultrasound denoising and localization microscopy further improve imaging clarity and lesion delineation45. Recent implementations of real-time thermography with deep learning underscore practical applications of AI in clinical settings46. Quantitative nuclear histomorphometry and optimized deep learning approaches have been used to predict risk categories and improve classification outcomes in early-stage breast cancer47,48. Collectively, these works demonstrate the importance of integrating multi-modal imaging, advanced feature extraction, and multi-stage deep learning frameworks, motivating the development of our proposed model for accurate segmentation and classification of breast lesions in mammography.

The MSDLM model performs well in breast lesion detection, but with some significant limitations. First, its complexity owing to the application of U-Net, EfficientNetV2 B0, and a CNN classifier results in a very high number of trainable parameters, with consequent overfitting risks on small-sized or imbalanced datasets. Second, like most work in this area, it is largely trained on the CBIS-DDSM and Wisconsin datasets, which may not accurately represent the actual real-world diversity, creating bias and generalizability problems. Third, its high computational requirements demand substantial GPU resources and lengthy training times, which may compromise scalability in resource-constrained healthcare environments. Overcoming these limitations is crucial for wider clinical uptake and credibility. The upcoming MSDLM system is promising for segmenting and classifying breast lesions, but it overfits and faces practical challenges in implementation.

The greatest challenge is the risk of overfitting due to the system’s complexity and the limited availability of small-sized, publicly available mammography databases. Despite the use of dropout, data augmentation, and early stopping, there remains a need to verify the system’s performance with larger and more diverse publicly available datasets in order to establish its generalizability.

Class imbalance in breast cancer datasets can disrupt the model’s discrimination against malignant instances. Additional studies should examine advanced techniques for addressing the issue, including the creation of synthetic data and ensemble techniques.The model is also plagued by domain adaptation, particularly when integrating image data from the CBIS-DDSM with table data from the WBCD, making compatibility more complex and its portability across clinical systems slower. Clinical considerations present practical challenges, particularly the need for explainable output in the application of deep learning, in order to gain greater confidence among radiologists and streamline the decision-making process. While techniques like Grad-CAM have been explored, more robust tools based on explainable AI are needed to achieve greater transparency. Additionally, computational constraints and inference times can disrupt real-time applications in high-capacity deployments. Finally, the receipt of approval from radiologists, as well as from regulatory authorities, is something that requires further research and interdisciplinary collaboration. We endeavoured to provide a clearer perspective on strategy and future research applications and uses in clinical practice.

Conclusion

This paper presents a novel MSDLM model that combines a Two-Parameter Gaussian distribution with U-Net, EfficientNetV2 B0, and a CNN classifier to enhance the detection of breast lesions in mammography images. The outcomes presented in the abstract reveal that the model achieved a classification accuracy of 97.6%, a sensitivity rate of 91.25%, an AUC of 95.75%, and an IoU of 85.59%, thereby outperforming most current state-of-the-art methods. The outcomes confirm the effectiveness of the new model for segmentation and classification in breast lesion tasks and serve as a useful tool for radiologists in making early diagnoses and well-informed decisions.

Future work

Follow-up studies can then be directed toward increasing the practicality of the model and its clinical usability. One potential direction is the development of a real-time deployment platform using model compression methods, such as pruning, quantization, or knowledge distillation, to limit computational cost while maintaining performance integrity. Another advancement would be the incorporation of explanation AI techniques—such as Grad-CAM or saliency heatmaps—to enhance the interpretability of the model, specifically identifying the region of interest that drives its outputs. These innovations would not only enhance radiologists’ faith but also facilitate clinical decision-making processes. Finally, incorporation of the model into clinical workflows, possibly through PACS-compatible interfaces or cloud-based diagnostic applications, may facilitate ease of implementation in hospital settings. Follow-up studies can also investigate validation using multi-center clinical trials to assess the robustness of the model across varying imaging environments and patient populations.

Data availability

The database used in the current study, the CBIS-DDSDM, is available for free download at The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) at the URL: https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/collection/cbis-ddsm/. The Wisconsin breast cancer database is accessible through the UCI Machine Learning Repository through the URL: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Breast+Cancer+Wisconsin+(Diagnostic). The database is open access and is accessible for research and academic use as long as it is in line with the usage terms that are attached to it.

References

Gurupakkiam, G., Ilayaraja, M. & A Survey on Breast Cancer Prediction using Various Deep Learning and Machine Learning. Techniques, 2024 9th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 2024, pp. 1872–1877. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCES63552.2024.10859664

Sheshadri, H. & Kandaswamy, A. Detection of breast cancer by mammogram image segmentation. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 1 (4), 232. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1482.19599 (2005).

Ansari, G. A., Shafi Bhat, S., Dilshad Ansari, M., Ahmad, S. & Abdeljaber, A. M. Prediction and diagnosis of breast cancer using machine learning techniques. Data Metadata. 3, 346. https://doi.org/10.56294/dm2024.346 (2024).

Sohan, M. F. & Basalamah, A. A Systematic Review on Federated Learning in Medical Image Analysis, in IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 28628–28644, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3260027

Hou, R. Anomaly detection of calcifications in mammography based on 11,000 negative cases. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 69 (5), 1639–1650. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2021.3126281 (2022). ISSN 0018-9294.

Amorim, J. P. Evaluating the faithfulness of saliency maps in explaining deep learning models using realistic perturbations. Inf. Process. Manage. 60 (2), 0306–4573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2022.103225 (2023).

Almalki, Y. E. Impact of image enhancement module for analysis of mammogram images for diagnostics of breast cancer. Sensors 22 (5), 1424–8220. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22051868 (2022).

Islam, M. R., Rahman, M. M. & Ali, M. S. Abdullah Al Nomaan Nafi, Md Shahariar Alam, Tapan Kumar Godder, Md Sipon Miah, Md Khairul Islam, Enhancing breast cancer segmentation and classification: An Ensemble Deep Convolutional Neural Network and U-net approach on ultrasound images, Machine Learning with Applications, Volume 16, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mlwa.2024.100555

Hekal, A. A., Elnakib, A., Moustafa, H. E. D. & Amer, H. M. Breast cancer segmentation from ultrasound images using deep Dual-Decoder technology with attention Network, in IEEE access, 12, pp. 10087–10101, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3351564

Baccouche, A., Garcia-Zapirain, B. & Olea, C. Connected-UNets: A deep learning architecture for breast mass segmentation. Npj Breast Cancer. 7, 151. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-021-00358-x (2021).

Alam, T., Shia, W-C., Hsu, F-R. & Hassan, T. Improving breast cancer detection and diagnosis through semantic segmentation using the Unet3 + Deep learning framework. Biomedicines 11 (6), 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11061536 (2023).

De la Luz Escobar, M. et al. Breast cancer detection using automated segmentation and genetic algorithms. Diagnostics 12 (12), 3099. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12123099 (2022).

Deb, S. D. & Jha, R. K. Segmentation of Mammogram Images Using Deep Learning for Breast Cancer Detection, 2022 2nd International Conference on Image Processing and Robotics (ICIPRob), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2022, pp. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIPRob54042.2022.9798724

Shaaban, M., Nawaz, S., Said, M. & Barr, Y. M. An Efficient Breast Cancer Segmentation System based on Deep Learning Techniques. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research. 13, 6 (Dec. 2023), 12415–12422. (2023). https://doi.org/10.48084/etasr.6518

Subha, M. Breast Cancer Detection Using Image Denoising and UNet Segmentation for Mammography Images. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering, 12(21s), 3015–3029. (2024). Retrieved from https://ijisae.org/index.php/IJISAE/article/view/5956

R, M. T. et al. Transformative breast cancer diagnosis using CNNs with optimized ReduceLROnPlateau and early stopping enhancements. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 17, 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44196-023-00397-1 (2024).

Isensee, F., Paul, F. J., Peter, M. F., Philipp, V. & Klaus, H. M. H. NNU-Net for brain tumor segmentation. In: International MICCAI Brainlesion Workshop, 118–132. Springer. (2021).

Khairandish, M. O., Sharma, M., Jain, V., Chatterjee, J. M. & Jhanjhi, N. Z. A hybrid CNN-SVM threshold segmentation approach for tumor detection and classification of MRI brain images. IRBM. 43(4), 290–299, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irbm.2021.06.003 (2021).

Xun, S. et al. RGA-Unet: An improved U-net segmentation model based on residual grouped convolution and convolutional block attention module for brain tumor MRI image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering (pp. 319–324). (2022), October.

Gupta, R. K., Santosh Bharti, N. K., Yatendra, S. & Nikhlesh, P. Brain tumor detection and classification using cycle generative adversarial networks. Interdisciplin Sci: Comput. Life Sci. 14, 485-502 (2022).

Haq, A. et al. DEBCM: deep learning-based enhanced breast invasive ductal carcinoma classification model in IoMT healthcare systems. IEEE J. Biomedical Health Inf. 28 (3), 1207–1217 (2022).

Pandimurugan, V. et al. CNN-Based deep learning model for early identification and categorization of melanoma skin cancer using medical imaging. SN COMPUT. SCI. 5, 911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-024-03270-w (2024).

Mukasheva, A. et al. Modification of U-Net with Pre-Trained ResNet-50 and atrous block for polyp segmentation: model TASPP-UNet. Eng. Proc. 70 (1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2024070016 (2024).

Kaur, P., Singh, G. & Kaur, P. Intellectual detection and validation of automated mammogram breast cancer images by multi-class SVM using deep learning classification. Inf. Med. Unlocked Volume. 16, 2352–9148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2019.01.001 (2019).

Zebari, D. A. et al. Breast cancer detection using mammogram images with improved Multi-Fractal dimension approach and feature fusion. Appl. Sci. 11 (24), 12122. https://doi.org/10.3390/app112412122 (2021).

Agbley, Bless Lord, Y. et al. Federated fusion of magnified histopathological images for breast tumor classification in the internet of medical things. IEEE J. Biomedical Health Inf. 28(6), 3389–3400 (2023).

Zeng, Q., Chen, C., Chen, C., Song, H., Li, M., Yan, J.,… Lv, X. (2023). Serum Raman spectroscopy combined with convolutional neural network for rapid diagnosis of HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancer. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 286, 122000. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2022.122000.

Li, Z. et al. White patchy skin lesion classification using feature enhancement and interaction transformer module. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 107 (107819). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2025.107819 (2025).

Zhang, Y. P. et al. Artificial intelligence-driven radiomics study in cancer: the role of feature engineering and modeling. Military Med. Res. 10, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-023-00482-9 (2023).

Chen, W., Liu, Y., Wang, C., Zhu, J., Li, G., Liu, C.,… Lin, L. (2025). Cross-Modal Causal Representation Learning for Radiology Report Generation. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 34, 2970–2985. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2025.3568746.

Nour, A. & Boufama, B. Hybrid deep learning and active contour approach for enhanced breast lesion segmentation and classification in mammograms. Intelligence-Based Med. 11, 100224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmed.2025.100224 (2025).

Kumar Saha, D. et al. Segmentation for mammography classification utilizing deep convolutional neural network. BMC Med. Imaging. 24, 334. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-024-01510-2 (2024).

Murty, D. S., Sharma, A. & Pradhan, M. Integrative hybrid deep learning for enhanced breast cancer diagnosis: leveraging the Wisconsin breast cancer database and the CBIS-DDSM dataset.Scientific Reports, 14, 74305, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74305-8 (2024).

Singh, D. & Singh, A. K. Role of image thermography in early breast cancer detection—Past, present and future. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 183, 105074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105074 (2020).

Ma, X. et al. Detection of breast cancer based on novel porous silicon Bragg reflector surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy-active structure. Chin. Opt. Lett. 18 (5), 051701. https://doi.org/10.3788/COL202018.051701 (2020).

Luan, S., Yu, X., Lei, S., Ma, C., Wang, X., Xue, X.,… Zhu, B. (2023). Deep learning for fast super-resolution ultrasound microvessel imaging. Physics in Medicine & Biology,68(24), 245023. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ad0a5a

Al Husaini, M. A. S. et al. Thermal-based early breast cancer detection using inception V3, inception V4 and modified inception MV4. Neural Comput. Appl. 34, 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-021-05849-3 (2022).

Zhu, C. et al. AMSFuse: Adaptive Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Network for Diabetic Retinopathy Classification. Computers Mater. Continua, 82(3), 5153–5167. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.058647 (2025).

Jiang, R., Yin, X., Yang, P., Cheng, L., Hu, J., Yang, J.,… Lv, H. (2024). A transformer-based weakly supervised computational pathology method for clinical-grade diagnosis and molecular marker discovery of gliomas. Nature Machine Intelligence, 6(8), 876–891.doi: 10.1038/s42256-024-00868-w.

Al Husaini, M. A. S., Habaebi, M. H., Gunawan, T. S. & Islam, M. R. Self-detection of early breast cancer application with infrared camera and deep learning. Electronics 10, 2538. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10202538 (2021).

Al Husaini, M. A. S. et al. Influence of tissue thermo-physical characteristics and situ-cooling on the detection of breast cancer. Appl. Sci. 13, 8752. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13158752 (2023).

Yang, J., Wang, G., Xiao, X., Bao, M. & Tian, G. Explainable ensemble learning method for OCT detection with transfer learning. PloS One. 19 (3), e0296175. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296175 (2024).

Doig, K. D., Fellowes, A. P. & Fox, S. B. Homologous recombination repair deficiency: an overview for pathologists. Mod. Pathol. 36, 100049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.modpat.2022.100049 (2023).

Daly, G. R. et al. Screening and testing for homologous recombination repair deficiency (HRD) in breast cancer: an overview of the current global landscape. Curr. Oncol. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-024-01507-7 (2024).

Yu, X., Luan, S., Lei, S., Huang, J., Liu, Z., Xue, X.,… Zhu, B. (2023). Deep learning for fast denoising filtering in ultrasound localization microscopy. Physics in Medicine& Biology, 68(20), 205002. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/acf98f.

Al Husaini, M. A. S., Habaebi, M. H. & Islam, M. R. Utilizing deep learning for the real-time detection of breast cancer through thermography. In 2023 9th International Conference on Computer and Communication Engineering (ICCCE) (pp. 270–273). IEEE. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCCE58370.2023.10223456

Whitney, J. et al. Quantitative nuclear histomorphometry predicts oncotype DX risk categories for early-stage ER + breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 18, 610. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4524-8 (2018).

Saleh, H., Abd-El Ghany, S. F., Alyami, H. & Alosaimi, W. Predicting breast cancer based on optimized deep learning approach. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022, 1820777. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1820777

Acknowledgements

This study is supported via funding from Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R138), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, it is supported by Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2025/R/1446).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sultan Ahmed contributed to the conceptualization of the study, design of the Multi-Stage Deep Lesion Model (MSDLM), and drafting of the manuscript.Eali Stephen Neal Joshua was responsible for the implementation of the segmentation and classification models, as well as performing data analysis and model evaluation.N. Thirupathi Rao assisted in the development and tuning of the deep learning architecture and contributed to the analysis of experimental results.Rania M. Ghoniem provided critical revisions, clinical insights, and helped validate the results from a medical imaging perspective.Belayneh Matebie Taye (Corresponding Author) supervised the overall research workflow, coordinated collaborative efforts among institutions, and finalized the manuscript for submission.Salil Bharany contributed to dataset curation, pre-processing, and statistical analysis, and reviewed the manuscript for technical accuracy.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics and consent

Our research study did not require ethics approval because we used the standard dataset.

Ethics approval statement

No animals or human subjects were involved in this study. The study utilized publicly available datasets, and all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad, S., Neal Joshua, E.S., Rao, N.T. et al. A multi stage deep learning model for accurate segmentation and classification of breast lesions in mammography. Sci Rep 15, 37103 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21146-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21146-8