Abstract

This study investigates the structural, electronic, and inhibitory properties of two novel Schiff base compounds, (E)-5-(((4-bromophenyl)imino)methyl)-2-methoxyphenol (BPhIM) and (E/Z)-5-(((4-aminophenyl)imino)methyl)-2-methoxyphenol (APhIM), as potential multi-target inhibitors of key metabolic enzymes linked to neurodegenerative disorders. The compounds were characterized using density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B97D3/6-311 + + G(d, p) level. DFT analysis revealed a low energy gap (2.39–2.65 eV), indicating high chemical reactivity, and significant first hyperpolarizability values (9.98–31.25 × 10−30 esu), suggesting strong nonlinear optical (NLO) activity. Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) maps identified nucleophilic and electrophilic sites, while RDG analysis quantified stabilizing non-covalent interactions. Molecular docking simulations against acetylcholinesterase (AChE), butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), and human carbonic anhydrase I and II (hCA I/II) demonstrated promising binding affinities. The compounds exhibited excellent predicted inhibition constants (Ki), with APhIM being particularly potent against AChE (Ki = 0.42 µM) and BChE (Ki = 0.83 µM), outperforming the standard drug Tacrine. BPhIM showed strong activity against hCA I (Ki = 0.83 µM). Furthermore, in silico ADMET profiling indicated favorable drug-likeness, high gastrointestinal absorption, and low toxicity risks. The results underscore the dual potential of these Schiff bases as promising scaffolds for the development of NLO materials and as multi-target therapeutic agents, offering a robust basis for future applications in optoelectronics and drug discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

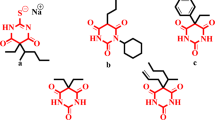

Nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds constitute a major class of molecules exhibiting diverse and significant biological properties. Among these, Schiff bases, defined by the azomethine functional group (–RC = N–), represent a highly important class of compounds demonstrating a broad spectrum of potent pharmacological activities. These include well-documented anticonvulsant, antidepressant, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antimicrobial, antimalarial, anticancer, and antioxidant effects1. These compounds are not only key intermediates in the synthesis of bioactive molecules and complex nitrogen-containing heterocycles. but are also frequently present in naturally occurring products, underpinning their significant importance in both advanced synthetic chemistry and modern pharmaceutical research2,3.

Driven by their promising biological properties, these compounds have garnered considerable scientific interest. In parallel, researchers in physics and chemistry have increasingly focused on organic materials due to their exceptional nonlinear optical (NLO) characteristics. The inherent synthetic flexibility of these organic materials, powerfully augmented by theoretical modeling, facilitates their development compared to inorganic counterparts. Their NLO features can be more precisely controlled due to highly delocalized electronic structures and extensive π-conjugation4,5,6,7,8,9.

The density functional theory (DFT) method stands as a powerful and reliable tool for the theoretical analysis of such molecules, delivering precise results that are comparable to experimental findings. Its strategic application is fundamental to this investigation, serving as a powerful computational scaffold that bridges molecular structure with electronic properties and biological activity. DFT provides an indispensable platform for predicting molecular reactivity, stability, and nonlinear optical (NLO) responses in silico, thereby guiding and rationalizing experimental findings. This approach is crucial for the rational design of novel functional materials and bioactive compounds10,11,12.

DFT provides an efficient framework for gathering information about fundamental molecular properties by analyzing electron density, equilibrium molecular structure, vibrational frequencies, global chemical reactivity, and NLO properties. Moreover, in computational biology, DFT serves to analyze molecular orbital energies that are related to a molecule’s reactivity within a biological target4,5,6,13. Specifically, HOMO and LUMO analyses are routinely used to determine key electronic properties such as ionization potential (I), electron affinity (A), electronegativity (χ), chemical hardness (η), chemical potential (µ), softness (S), electrophilicity index (ω), nucleophilicity index (ν), and maximum charge transfer (ΔNmax)14,15,16. Furthermore, the detailed redistribution of electron density (ED) between bonding and anti-bonding orbitals can be quantitatively investigated through Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis within the DFT approach4,5,6,13. The geometrically optimized molecular structure obtained from DFT calculations forms the basis for the assessment of key physicochemical properties, including the dipole moment (µ), isotropic average polarizability (α), polarizability anisotropy (Δα), total first hyperpolarizability (β), average second hyperpolarizability (γ), hyper-Rayleigh scattering first hyperpolarizability βHRS(–2ω; ω, ω), and the depolarization ratios (DR)4,5,6,13. The profound utility of this comprehensive DFT approach in elucidating spectroscopic characteristics, solvation effects, topological insights, and pharmacodynamic profiles has been powerfully demonstrated in recent seminal studies17,18,19. In alignment with these advanced works, our study leverages DFT to meticulously unravel the electronic structure, NLO behavior, and inhibitory potential of the title Schiff base compounds, providing a deep mechanistic understanding of their properties and establishing a foundation for their future application20,21,22.

This study investigates the structural features, nonlinear optical (NLO) properties, and molecular docking of two newly synthesized Schiff base derivatives, with the objective of evaluating their potential pharmacological applications and electronic properties.

Computational details

All quantum chemical calculations were performed using the Gaussian 16 program package23, and molecular geometries derived from the Gaussian output files were visualized with GaussView 0624. The geometrical structures of the title compounds were fully optimized in the gas phase using the B97D3 functional25,26 in conjunction with the 6-311 + + G(d, p) basis set. This functional was specifically selected for its inclusion of Grimme’s D3 empirical dispersion correction25, which is crucial for the accurate description of non-covalent interactions (e.g., van der Waals forces, π-π stacking) that are prevalent in these molecular systems. The 6-311 + + G(d, p) basis set provides a balanced treatment of valence and diffuse functions, ensuring reliable predictions of electronic properties for molecules containing heteroatoms like O, N, and Br27. Vibrational frequency calculations at the same level of theory confirmed that all optimized structures were true minima on the potential energy surface (no imaginary frequencies). The VEDA 4 program was used to calculate and analyze the potential energy distributions (PED) of the vibrational modes of the optimized compounds28. At the same theoretical level, the natural bonding orbitals (NBOs) were computed using the NBO 7.0 program29, which is incorporated in the Gaussian package. HOMO–LUMO analysis has been used to compute the global and local reactivity descriptors. The nonlinear optical (NLO) potential of the title compounds were further demonstrated by calculating the dipole moment (µ), isotropic average polarisability (α), polarisability anisotropy (Δα), total first hyperpolarizability (β) and average second hyperpolarizability (γ). The non–covalent interactions (NCI) theory was used for the reduced density gradient (RDG) studies, and the VMD program30 was used for the interaction region indicator (IRI) studies. The wave function analysis software Multiwfn31 was used for the covalent and non–covalent interactions, respectively. Finally, the investigation of ligand-target interactions was carried out using molecular docking. The three-dimensional structures of the target enzymes acetylcholinesterase (AChE, PDB ID: 4EY6), butyrylcholinesterase (BChE, PDB ID: 4BDS), carbonic anhydrase I (hCA I, PDB ID: 2NMX), and carbonic anhydrase II (hCA II, PDB ID: 3HS4) were retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org). The selection criteria were based on high-resolution X-ray structures (< 2.5 Å) from Homo sapiens with no mutations at the active site. The protein structures were prepared using AutoDock Tools (ADT)32. This process involved the removal of all water molecules, co-crystallized ligands, and the assignment of Kollman united atom charges. The optimized three-dimensional structures of the ligands, (E)−5-(((4-bromophenyl)imino)methyl)−2-methoxyphenol (BPhIM) and (E/Z)−5-(((4-aminophenyl)imino)methyl)−2-methoxyphenol (APhIM) were prepared for docking by assigning Gasteiger charges. were then used for docking. The grid box dimensions and center coordinates for each protein’s active site were defined to encompass all key residues known to be involved in substrate binding and catalysis, based on the literature and analysis of the native co-crystallized ligands. The specific parameters for each target are summarized in Table 7.

The docking calculations were performed using AutoDock Vina33, which employs a sophisticated scoring function and a gradient optimization algorithm for conformational search. The exhaustiveness parameter, which controls the depth of the global search, was set to 8 for all simulations to ensure a comprehensive sampling of the binding poses. All other parameters were kept at their default values. For each ligand, ten independent docking runs were performed, and the pose with the most favorable binding affinity was selected for further analysis. The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the docked pose and the original crystallographic pose was calculated. An RMSD value of less than 2.0 Å is generally considered successful validation34,35. Our protocol yielded an excellent RMSD of 0.27 Å for AChE (4EY6) and 0.89 Å for hCA II (3HS4), confirming its accuracy in reproducing experimental binding modes. The resulting docking poses were visualized and analyzed using Discovery Studio Visualizer36 to identify key intermolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and halogen bonds.

The drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic profiles (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity ADMET) of the title compounds were predicted using the SwissADME37 and pkCSM38 online web servers.

Results and discussion

Structure description

The comparison between experimental (X–ray) and computational (B97D3/6–311G++ (d, p)) results reveals several noteworthy observations regarding the structural properties of the Schiff bases (APhIM and BPhIM), highlighting key structural differences arising from the substitution of N2 in APhIM with Br in BPhIM. Relevant bond distances, bond angles and dihedral angles are reported summarized in Table 1 and are in good agreement with those reported in similar Schiff base compounds39. The molecular structures with atomic labeling are depicted in Fig. 1. Additionally, for various phenyl rings, the average bond length determined by X–ray diffraction is roughly 1.38 Å39. Notably, the literature also states that these bonds have a C–C bond length of 1.39 Å. Furthermore, the average bond length obtained through X–ray diffraction for different phenyl rings is approximately 1.38 Å39. It is worth noting that the literature also reports a C–C bond length of 1.39 Å for these bonds3. The C7 = N17 bond length of BPhIM is observed at 1.283 Å and is calculated at 1.289 Å, and for their neighboring N‒C, C–C bonds lengths (C4–N17, C7–C8) are observed at 1.419 Å and 1.454 Å39, these bonds theoretically located at 1.401 Å and 1.457 respectively. As can be noticed from Table 1, the bond lengths of C10–O15, C14–O16 and C11–O16 are observed at 1.358, 1.431 and 1.358 Å, respectively, these specific bond lengths have been precisely computed as 1.369, 1.430 and 1.358 Å at the B97D3/6‒311G++(d, p) level. The bond length for C1–Br18 presents the highest distance and is computed to be 1.923 Å by DFT, while XRD obtained the values is 1.901 Å39. Computationally determined bond angles show good agreement with actual observations; for example, the bond angle of C8–C7–N17 and C4–N17–C7 are 123.8°, 119.6° (X–ray) and 123.0°, 119.7 °(B97D3), indicating congruence between the theoretically anticipated and experimentally observed molecular conformation. Reliable predictions of molecule orientation are shown by the dihedral angles of C12–C11–O16–C14, which are 13.8° (X–ray) and 0.1° (B97D3). Dihedral angles are essential for comprehending molecular conformations and show strong agreement between experimental and computational data. The majority of the optimized bond lengths, as shown in Table 1, are marginally longer than the experimental values. One possible explanation for these discrepancies is that experimental data are obtained in the solid state, whereas calculated values are obtained in the gas phase.

The success of the computational method (B97D3/6–311G++ (d, p) in clarifying the structural properties of the title chemical molecule is demonstrated by the agreement between the experimental and computational results. These results offer insightful information for additional research into the title compound’s physical and chemical characteristics as well as possible uses.

To quantitatively assess the agreement between the computational and experimental geometries, the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) was calculated for the bond lengths and bond angles listed in Table 1. The low RMSD values of 0.023 Å for bond lengths and 1.12° for bond angles provide strong validation of the B97D3/6-311 + + G(d, p) level of theory for accurately predicting the molecular structure of these Schiff base compounds. This excellent agreement is further supported by the vibrational analysis; a correlation between the experimental FT-IR wavenumbers and the scaled theoretical frequencies for BPhIM shows a linear correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.998. This indicates an exceptional agreement between the calculated and observed values, confirming the accuracy of the vibrational assignments and the reliability of the chosen computational method.

Vibrational spectra

For identifying the functional groups in organic compounds, infrared spectroscopy is a useful method. Using the DFT/B97D3 method at 6–311G++ (d, p) basis set, the BPhIM and APhIM compounds were characterized using Fourier transform infrared (FT–IR) analysis and vibrational frequencies. BPhIM, the first molecule, is made up of 30 atoms that vibrate in 84 different typical ways. The 84 vibrational modes are composed of 29 stretching vibrations, 28 in–plane vibrations, and the remaining 27 out–of–plane vibrations. 32 atoms make up the second molecule, APhIM, which vibrates in 90 different typical patterns, of the 90 vibrational modes, 31 are stretching vibrations, 29 are out–of–plane vibrations, and 30 are in–plane vibrations. At the same time, the VEDA software based on the potential energy distribution (PED) assignment was used to carry out the generated modes and frequencies. The theoretical harmonic frequencies were scaled using an empirical factor of 0.97 to correct theoretical errors. The expected (cm–1) vibrational frequencies and likely assignments for both compounds are shown in Tables 2 and 3, and the corresponding calculated I.R. spectra are shown in Fig. 2.

Aromatic ring vibrations.

According to the literature, the absorption of the aromatic C–H stretching mode is generally expected to occur in the 3100–3000 cm–140 region. This is roughly in line with our findings, which predict that the two compounds will absorb in the 3063–3007 cm–1 region. The in plane C–H bending vibrations are estimated in the region 1473–1021 cm–1. The out–of–plane C–H bending vibrations are predicted at 893–691 cm–1. Generally, the C = C stretching vibrations in aromatic compounds occur in the region 1600–1400 cm–140. Therefore, the C = C stretching vibrations are occurred at 1576 and 1573 cm–1 in FT–IR spectrum in the BPhIM and APhIM, respectively41. The corresponding theoretical values were computed at 1576, 1543, and 1507, 1318, 1271, and cm–1 with PED more than 41%. The C–C–C in plane bending bands always occurs between the value 1000–700 cm–142.

This is roughly in line with our findings, which predict that the two compounds will absorb in the 968–491 cm–1 region.

C = N and C–N vibrations.

Typically, the imine group (C = N) stretching vibration bands are used to describe the vibrational modes in the 1640–1690 cm–1 region3. The values of the C = N stretching vibration in the current section are 1558 cm–1 and 1577 cm–1, which are 48% and 28%, respectively, and occur at 1611 and 1643 cm–1 in the FT–IR spectrum41 for BPhIM and APhIM, respectively.

CH3 vibrations.

The symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of CH3 are expected to fall between 2870 and 2860 cm–1 and 3000–2905 cm–13, respectively. With PED greater than 91%, the methyl group’s asymmetric and symmetric CH3 stretching vibrations are located in the regions 2999–2863 cm–1 and 3001–2866 cm–1 for APhIM and BPhIM, respectively. The C–H in–plane bending vibrations of the title compound for CH3 are calculated at 1430, 1428, 1417, 1400, and 1105 cm–1. Moreover, the out–of–plane bending of C–OCH3 vibrations are computed at 986 cm–1 and 989 cm–1 the stretching O–C, in–plane and out of plane are assigned at 1120, 954, 729 and 513 cm–1.

N‒H vibrations.

In the 3500–3300 cm–1 range, the N–H stretching vibration typically appears as a noticeable band. The N–H stretching vibration in this work has a corresponding theoretical wavenumber of 3499 cm–1 and 3401 cm–1. For δHNN and τHNNC, the harmonic wavenumber is 1586 cm–1 and 786 cm–1, respectively, with a significant PED value of 54% and associated modes Ns of 76 and 37.

The C–N band in this paper was calculated to be 1520 cm–1 and 1530 cm–1. This mode’s mixed character is shown by its PED of 18% and 11%, respectively. The dominant C–N in–plane bending and out–of plane bending modes have been assigned at calculated wavenumbers 612 cm–1 band 669 cm–1, respectively.

C–Br vibration.

The values of the C–Br stretching vibration in the current section is 636 cm–1, and occur at 979 cm–1 in the FT–IR spectrum3 for BPhIM.

Frontier molecular orbitals

The Frontier Molecular Orbitals (FMOs), namely the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and the Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO), are crucial for determining a molecule’s reactivity and optoelectronic properties. The HOMO represents the ability to donate electrons, while the LUMO signifies the tendency to accept electrons. The energy difference between them, known as the HOMO-LUMO gap (ΔE), is a key indicator of a molecule’s kinetic stability, chemical reactivity, and polarizability.

At the B97D3/6-311 + + G(d, p) level of theory, the HOMO, LUMO, and the energy gap between them were calculated for both the BPhIM and APhIM compounds. The HOMO and LUMO orbital energy levels and their spatial distribution in the ground state are depicted graphically in Fig. 3. Analysis of the orbital forms shows that both the HOMO and LUMO are delocalized over the entire π-conjugated framework of the molecules.

The calculated HOMO-LUMO energy gaps are 2.65 eV for BPhIM and 2.39 eV for APhIM. These values are considered relatively narrow for stable organic molecules, which typically exhibit gaps in the range of 4–8 eV43,44. A narrow frontier orbital gap is associated with lower kinetic stability, high chemical reactivity, and enhanced polarizability. Consequently, the APhIM molecule, with its smaller gap, is a particularly viable candidate for the creation of optically active materials, as its reduced gap facilitates intramolecular charge transfer, a key requirement for strong nonlinear optical (NLO) responses45.

Global chemical reactivity descriptors (GCRD)

To comprehend many facets of pharmacological research, such as drug design and potential ecotoxicological characteristics of drug molecules, a number of novel chemical reactivity descriptors have been developed. In order to determine the global reactivity parameters (GRP), the following formula46 can be used: electronegativity (χ), chemical hardness (η), chemical potential (µ), chemical softness (s), and electrophilicity index (ω).

where I = – EHOMO and A = – ELUMO are the ionization potential and electron affinity, respectively. The GRP values were evaluated by using B97D3 functional with 6–311G++ (d, p) basis set. All these parameters are listed in Table 4.

The chemical hardness (η) of BPhIM and APhIM was determined to be 1.33 eV and 1.19 eV, respectively. These low values classify them as “soft” molecules, which generally exhibit higher chemical reactivity and favor interactions with biological soft bases, allowing for faster electron transport. The stability of the compounds is further indicated by their negative chemical potential values (–3.81 eV for BPhIM and − 3.28 eV for APhIM), which signify thermodynamic stability and a tendency to resist autodegradation47,48. Both compounds exhibit a strong electron-attracting power, as evidenced by their electrophilicity index (ω), and are predicted to behave as electrophiles.

Furthermore, these calculated parameters provide crucial insights into the redox behavior and potential metabolic stability of the compounds. The HOMO energy (EHOMO) is directly related to the ionization potential (I = -EHOMO) and thus, the ease of oxidation. The relatively high EHOMO values of −5.13 eV (BPhIM) and − 4.47 eV (APhIM) suggest a tendency to donate electrons, making them potential substrates for oxidative metabolic enzymes like cytochrome P450s. This is consistent with our ADMET predictions.

However, the energy gap (ΔE) further modulates this reactivity. APhIM, with its smaller gap (2.39 eV), is expected to be more chemically reactive and potentially more susceptible to metabolic transformation than BPhIM (ΔE = 2.65 eV). This structure-activity relationship is valuable: the electron-donating amine group in APhIM raises the HOMO energy, increasing its reactivity, while the bromine atom in BPhIM provides a larger gap, potentially contributing to greater metabolic stability. This balance between reactivity for biological activity and stability for pharmacokinetics is a key consideration in drug design49.

Reduced density gradient (RDG) and the interaction region indicator (IRI)

The Reduced Density Gradient (RDG) analysis stands as an efficacious technique for investigating diverse non–covalent interactions within molecular structures. 2D–RDG scatters plots provided at B97D3 level for both Schiff bases (APhIM and BPhIM) are exhibited in Fig. 4. The NCI–RDG scan is generated using a 0.5 isosurface value for Schiff bases. This approach rep resents a dimensionless key parameter derived from the electron density (r) and its first derivative. Originally crafted by Johnson et al., this method serves as an exceptionally potent tool for analyzing weak interactions50:

The NCI–RDG diagrams for the two examined Schiff bases were constructed using the Multiwfn and VMD programs. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the RDG scattering patterns revealed a λ2(r) function ranging from 0.035 to 0.020 au, displaying three distinct interaction sites. The green–circled region (λ2(r) = 0) signifies intermediate interactions or Van der Waals (VDW) weak attractive interactions due to H…H interaction, while repulsive interactions (steric effect: λ2(r) > 0) are depicted in red. Notably, these repulsive interactions are predominantly localized at the aromatic rings, indicative of π – π stacking interactions50. The nature of interactions within these compounds is contingent upon their electron density properties. Regions encircled in blue (λ2(r) < 0) signify areas of robust electrostatic interactions, specifically about hydrogen bonds.

Using the interaction region indicator (IRI), a variety of interactions can be concurrently disclosed in chemical compounds, including covalent and non–covalent bonds. The IRI and RDG are separated by a constant factor (an adjustable value “a»”) that is essential to preserving the balance between the covalent and NCI. The following represents these covalent and non–covalent bonds and how they are represented graphically:

Similar to the RDG experiment, the sign (λ2) ρ function was displayed on the IRI isosurfaces using a color scale to indicate the type of interactions (the vdW, repulsion (steric effect), and attraction (hydrogen bond)). VMD and Multiwfn software are used to create the IRI isosurfaces of the APhIM and BPhIM compound. According to Fig. 4c, d, the green region represents the vdW interaction, the red region represents the steric effect within the phenyl rings, the combination of π–electrons in the phenyl ring, or the CC link, is what causes the strong interactions.

Furthermore, to provide a complementary topological perspective, an Atoms-in-Molecules (AIM) analysis was conducted. This analysis revealed bond critical points (BCPs) corresponding to the noncovalent interactions identified by RDG. The electron density (ρ) at these BCPs was found in the range of 0.012–0.032 a.u., which is characteristic of moderate hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts. The Laplacian of the electron density (∇2ρ) at these points was positive, confirming the closed-shell nature of these interactions. Interestingly, slightly negative values of the total energy density H(r) were computed at some BCPs, suggesting a partial covalent character in some of the stronger contacts. These quantitative findings from both RDG and AIM frameworks provide a rigorous interpretation of the noncovalent interactions and support the stabilizing role of hydrogen bonding and π–π stacking in the molecular structure of the studied Schiff bases50.

Molecular electrostatic potential analysis

The electrostatic potential (ESP) has been widely employed for interpreting and prediction of the distribution of negative and positive potentials, which influence the reactive properties of the two related molecules. The differentially charged regions of two molecules can be visualized using molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surfaces. The MEP of the newly synthesized Schiff bases BPhIM and APhIM was determined using the DFT method, B97D3 functional with 6–311 + + G(d, p) basis set for gas phase. The MEP computed 3D plots of the studied molecules are shown in Fig. 5. The various colors illustrated in Fig. 5 correspond to distinct MEPs, and the color coding scale of these maps is ranged from − 6.003 to 6.003 eV, and − 5.301 to 5.301 eV for the BPhIM and APhIM molecules respectively51,52,53. The two molecules share a common structural core characterized by an azomethine linkage (C = N) connecting two substituted benzene rings, where one of them bears hydroxyl (OH) and methoxy groups (O–CH3). Consequently, similar features are displayed by the two maps in this zone for each molecule: The most negative potentials indicated by the deep red color is susceptible to electrophilic attack located on the oxygen atoms of the hydroxyl and methoxy moieties. In contrast, the deep dark blue ones around the H1 atom of hydroxyl group represent the highest nucleophilic nature and the yellow/orange color represents imine nitrogen potential sites for electrophilic attack. The key difference lies in the substituent on the second benzene ring. The compound APhIM (features an amino –NH₂ group) exhibits a red color in the electron–rich region on the nitrogen atom and a blue color in the electron–poor region on the amino hydrogens. In contrast, the compound BPhIM features a bromine (–Br) atom in the corresponding position. The region around the bromine exhibits a more neutral potential (green/yellow) compared to the amino nitrogen and lacks the strong positive potential associated with hydrogen bond donors seen in APhIM; the bromine itself acts as a very weak hydrogen bond acceptor or potential halogen bond donor. Although these molecules share common reactive sites on the phenolic side, substituting the amino group with bromine induces significant changes in their electrostatic properties. This modification particularly affects the opposite side of the molecule by eliminating the strong hydrogen bond donation capability inherent in APhIM. Consequently, the nature of potential intermolecular interactions is markedly altered.

Properties of nonlinear optics

Additionally, the BPhIM and APhIM were subjected to calculations and interpretations of the dipole moment (µ), the isotropic average polarisability (α), the polarisability anisotropy (Δα), the first hyperpolarizability (β), the second hyperpolarizability (γ), the hyper–Rayleigh scattering (HRS), the first hyperpolarizability βHRS (–2ω; ω, ω), and the depolarisation ratios (DR). The dipole moment (µ), the isotropic average polarisability (α), the polarisability anisotropy (Δα), the first hyperpolarizability (β), and the second hyperpolarizability (γ) at 0.0 frequency of the compounds under study are calculated using B97D3/6–311G++ (d, p) theory using the following equations in order to examine the relationship between molecular structure and NLO:

The calculated values have been converted into electrostatic units (esu) since the isotropic average polarisability (α), the polarisability anisotropy (Δα), the first hyperpolarizability (β), and the second hyperpolarizability (γ) obtained from the Gaussian 16 output are given in atomic units (a.u.)54,55. The conversion factors that were used are α, Δα (1 a.u. = 1.4819 × 10−25 esu), β (1 a.u. = 8.6392 × 10−33 esu), and γ (1 a.u. = 5.0367 × 10−40 esu). It is well accepted that higher dipole moment, molecule polarisability, first hyperpolarizability, and second hyperpolarizability values are necessary for more active nonlinear optical (NLO) properties. Table 5 lists the BPhIM and APhIM compounds’ nonlinear optical characteristics. Since there were no experimental results for the NLO properties of the substances under research, urea was selected as the reference in this investigation. A non–zero dipole moment is shown by the molecular dipole moments of BPhIM and APhIM, which are 4.24 D and 1.89 D, respectively. This demonstrates the polarity and strong intramolecular contact of BPhIM and APhIM, which can affect their optical and electrical behaviour. The anisotropy of polarisability (Δα) for BPhIM and APhIM is 45.84 × 10−24 esu and 46.14 × 10−24, respectively, whereas the isotropic average polarisability (α) is 37.96 × 10−24 esu and 37.41 × 10−24 esu. For birefringent and electro–optic applications, this implies a strong optical response and notable anisotropic behaviour. In a similar vein, the first order hyperpolarizability of BPhIM and APhIM is 9.98 × × 10–30 esu and 31.25 × × 10–30 esu, respectively. These values are 27 and 84 times urea’s value (β = 0.372 × × 10–30 esu). The charge transfer between the phenyl rings inside the molecular skeleton is most likely the cause of the high values of BPhIM’s and APhIM’s first order hyperpolarizability, according to the computation. Prospective candidates for second–harmonic generation (SHG), these findings imply that the molecule possesses modest second–order NLO activity. Given the significant anisotropy in polarisability, the material could find application in polarization–sensitive optical devices. The molecule’s donor–acceptor strength or conjugation length could be enhanced to further improve its NLO performance for application in photonic and optoelectronic technologies. Third–harmonic generation (THG), self–focusing, and the optical Kerr effect are all influenced by second hyperpolarizability (γ), a crucial element of third–order nonlinear optical (NLO) properties. The calculated values of γ for the molecules under investigation are 19.3 × 10–35 esu and 20.7 × 10–35 esu, respectively, indicating a significant third–order NLO reaction. Photonic switching, all–optical modulation, and optical signal processing may benefit from molecules having a high γ value.

The hyper Rayleigh scattering (HRS) first hyperpolarizability (βHRS (–2ω; ω, ω)) and depolarisation ratios (DR) were calculated and examined for the BPhIM and APhIM. To compute the βHRS (–2ω; ω, ω) and depolarisation ratios (DR), utilise the following formulas:

where <β2zzzz> and <β2xzz>, respectively, stand for the orientational averages of the β tensor. Without presuming Kleinman’s assumptions, these values can be found using the following equations:

Understanding the geometry of the chromophore, which causes the NLO response, is possible through the depolarisation ratio. The following equations can be used to find this parameter:

For Hyper–Rayleigh Scattering (HRS), the molecules under investigation have a first hyperpolarizability (βHRS) of 624.70 and 8972.33 (a.u.), indicating a significant second–order nonlinear optical (NLO) response. The molecule’s high βHRS value suggests that it may have a lot of potential for second–harmonic generation (SHG). The calculated depolarisation ratio (DR) of 4.92 for APhIM indicates that the tested compound’s nonlinear optical (NLO) response is largely one–dimensional (1D)13,56,57,58. Since the initial hyperpolarizability (β) is extremely anisotropic and primarily aligned along a single molecular axis, a DR value close to 5 suggests that the molecule’s NLO response is directionally dominant. Additionally, it is shown that the molecule’s hyperpolarizability tensor is anisotropic, with a depolarisation ratio (DR) of 4.92 for APhIM. Since a high DR value suggests that the NLO reaction is highly directed, the molecule is suitable for polarization–sensitive optical devices such as optical sensors and tunable lasers.

This study also investigated the dependence of the scattering intensity on the polarisation angle (Ψ) of the incident light. The scattering intensity was examined across a range of − 180° to 179° using a step size of 1°. Figure 6 shows the calculated scattering intensities at the B97D3/6–311 + + G (d, p) level of theory. A primarily one–dimensional (1D) nonlinear optical (NLO) response is depicted in Fig. 6. The first hyperpolarizability (β) is confirmed to be extremely anisotropic and largely aligned along a single molecular axis by the intensity peaking at Ψ = ±90°. The observed pattern is consistent with the previously calculated depolarisation ratio (DR = 4.25 and DR = 4.92), which shows a significant directional dependence of the NLO response. This behaviour makes molecules that have high dipole values, extended conjugation times, or strong donor–acceptor interactions appealing candidates for second–harmonic generation (SHG).

Natural bond orbital (NBO)

To demonstrate the delocalization and charge transfer brought about by intramolecular and intermolecular interactions between bonds as well as other factors including stability, reactivity, and donor–acceptor correlation, natural bond orbital analysis was carried out. Second–order perturbation theory also anticipated the most important interactions between stabilization energy and filled (donors) Lewis and empty (acceptors) non–Lewis orbitals. The stabilization energy E (2) related to delocalization from i (donor orbitals) to j (acceptor orbitals) is given by59,60 :

where \(\:{q}_{i}\) is the donor orbital occupancy, \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{i}\) and \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{j}\) are the orbital energies and \(\:{F}_{(i,j)}^{2}\) is the Fock matrix elements between the NBO j and i.

The NBO calculations have been implemented on BPhIM and APhIM compounds using DFT at B97D3 level using 6–311G++(d, p) basis set as performed in the Gaussian 16 package using NBO 7.0 program. Based on NBO analysis, the most significant interactions with stabilization energies E2 > 10 kcal mol⁻¹ are summarized in Table 6. The results reveal several key electronic features, aromatic Stabilization and Delocalization: Strong conjugative π → π* interactions within the phenyl rings (π(C1–C6) → π*(C2–C3) with E2 = 14.53–14.69 kcal mol⁻¹ and π(C8–C13) → π*(C9–C10) with E2 = 14.67–14.73 kcal mol⁻¹) are identified as the primary source of aromatic stability61,62. These interactions facilitate extensive charge delocalization across the π-framework, which is fundamental to the observed low HOMO-LUMO gap and high chemical reactivity.

Hyperconjugation and Molecular Rigidity: The exceptionally strong interaction between the lone pair on the methoxy oxygen and the anti-bonding orbital of the adjacent ring, LP(O16) → π*(C11–C12) (E2 = 27.88 kcal mol⁻¹ for BPhIM), is a definitive indicator of hyperconjugation. This electron donation explains the partial double-bond character and contributes to the restricted rotation and molecular rigidity around the C11–O16 bond, a factor that enhances the molecular planarity and nonlinear optical (NLO) response.

Imine Linkage and Bioactive Potential: Interactions involving the central imine group are paramount. The π(C8–C13) → π*(C7 = N17) interaction (E2 = 17.72 kcal mol⁻¹ for BPhIM) highlights the delocalization of electron density from the phenolic ring into the imine bond. This stabilizes the imine moiety and defines its electron-rich character, which is essential for its potential role as a hydrogen bond acceptor when interacting with enzymatic active sites, as suggested by the molecular docking results.

Back-Donation and High Polarizability: The very high E2 values for π → π** interactions (π(C1–C6) → π(C2–C3) at 174.60 kcal mol⁻¹ and π(C11–C12) → π(C8–C13) at 166.58 kcal mol⁻¹ for BPhIM) indicate a strong back-donation phenomenon. This is a hallmark of highly conjugated systems and is directly responsible for the significant electron delocalization, low kinetic stability, and high polarizability that underpin the molecule’s strong NLO properties.

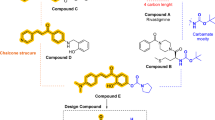

Molecular docking simulations

Molecular docking is a modern bioinformatics technique used to predict the probable experimental orientation and binding affinity required to form a stable complex between a ligand and a target63. In this study, two Schiff derivatives, (E)–5–(((4–bromophenyl)imino)methyl)–2–methoxyphenol (abbreviated BPhIM) and (E/Z)–5–(((4–aminophenyl)imino)methyl)–2–methoxyphenol (APhIM), were evaluated by molecular docking for their inhibitory capacity against several human enzymes: acetylcholinesterase (AChE), butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), and carbonic anhydrases I and II (hCA I and hCA II)), enzymes that are linked to some global disorders including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), epilepsy, and glaucoma41. To put the performance of these compounds into context, two well–known reference molecules were included: Tacrine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, and Acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor. The crystal structures of these proteins are specifically identified as 4EY6, 8OGI, 2NMX and 3HS4, respectively, these target proteins were sourced from the RCSB online Protein Data Bank (PDB) website at https://www.rcsb.org/.

The selection of proteins was based on specific criteria. First, their structures were determined using X–ray diffraction (XRD), the most accurate experimental technique for such analyses. The corresponding PDB data have a resolution of less than 2.50 Å64, ensuring high–quality structural information. Moreover, the selected proteins include experimental R–free values, which are essential for assessing the reliability of the structural models. All chosen proteins had R–free values below 0.4565 (see Table 7), demonstrating strong agreement between the model and experimental data. The results enabled us to determine the binding energy between the various proteins and different ligand positions. A negative binding energy value indicates a potential interaction between the ligand and the receptor. The inhibition constant (Ki) was then calculated using the formula: Ki = exp (ΔG/RT), where ΔG represents the binding energy, R is the gas constant (1.9872036 × 10⁻³ kcal·mol⁻¹), and T is the surrounding temperature (298.15 K)66, A lower inhibition constant suggests a more effective drug derived from the studied molecule. Further, the following insights can be gleaned from the studied enzyme inhibition results given in Tables 8 and 9.

The docking results revealed binding score values of between − 8.7 and − 4.8 kcal/mol, and inhibition constants (Ki) ranging from 0.42 µM to over 300 µM. Overall, the two compounds tested outperformed the reference molecules in all the enzyme targets studied, both in terms of binding affinity and inhibitory potency prediction. For cholinesterases, APhIM performed particularly well, with a score of − 8.7 kcal/mol and a Ki of 0.42 µM for AChE, and − 8.3 kcal/mol/0.83 µM for BChE, results that were significantly better than those for tacrine, which scored − 8. 1 kcal/mol/1.16 µM and − 7.7 kcal/mol/2.27 µM respectively. These performances suggest that APhIM could be a better cholinesterase inhibitor than tacrine, while having a different, potentially less toxic, chemical structure. The amine group in the para position of APhIM’s aromatic ring seems to favour hydrogen bonds and polar interactions within the active site of cholinesterases, which could explain its high affinity. The results for BPhIM were also remarkable, particularly with AChE (score of − 8.4 kcal/mol, Ki of 0.70 µM), slightly below APhIM, but still superior to tacrine. On BChE, BPhIM presented a score of − 7.8 kcal/mol (Ki = 1.92 µM), also better than the reference molecule. The presence of a bromine atom in the para position gives BPhIM hydrophobic interaction properties and potentially halogen bonds, which could be stabilised in active pockets rich in non–polar or aromatic residues. In terms of inhibition of carbonic anhydrases, the data show that BPhIM dominates, with a score of − 8.3 kcal/mol (Ki = 0.83 µM) for hCA I, and − 6.9 kcal/mol (Ki = 8.76 µM) for hCA II. APhIM showed similar performance for hCA I (–8.0/1.37 µM), but lagged behind for hCA II (–6.7/12.27 µM). By comparison, acetazolamide, considered to be a reference inhibitor of ACs, showed much lower affinities, with Ki values of 20.36 µM (hCA I) and 303.09 µM (hCA II). These unexpected results suggest that the derivatives studied could interact effectively with the active sites of CA without containing a sulphonamide group. The results of molecular docking were performed with the AutoDock Vina program and analyzed by accelrys discovery studio software. For each ligand, the interactions with the 4ey6 protein are illustrated in Figs. 7, 8 and 9, where the hydrogen bonds formed between the amino acid of the protein and the designated ligand are indicated by the green line67.

To further contextualize the inhibitory potential of the synthesized Schiff bases, the predicted binding affinities and ADMET profiles of the best-performing ligands were directly compared with those of known standard inhibitors. Tacrine and Donepezil were used as reference standards for acetylcholinesterase (AChE), while Acetazolamide was used for the carbonic anhydrase isoforms (hCA I and II).

The molecular docking results revealed that our compounds exhibit competitive binding affinity. For instance, APhIM demonstrated a strong predicted binding energy (−8.7 kcal/mol) against AChE, which is comparable to that of Tacrine (−8.1 kcal/mol) and approaches the affinity of Donepezil (typically reported around − 10.0 to −11.0 kcal/mol in similar studies)68,69. Similarly, BPhIM showed a superior predicted affinity for hCA I (−8.3 kcal/mol) compared to Acetazolamide (−6.4 kcal/mol).

Beyond binding affinity, the ADMET profile of our compounds suggests a competitive advantage in terms of toxicity and specificity. While standard inhibitors like Tacrine are known for hepatotoxicity70, our Schiff bases were predicted to be non-hepatotoxic and non-mutagenic (AMES negative).

Docking validation using redock.

The docking process was validated by re–docking experiments in which the protein structure was kept fixed while the ligand was redocked into its original crystal–binding pocket. The comparison between the docked poses and the crystal structure poses of the ligand was assessed using the root mean square deviation (RMSD). For the protein structure (PDB ID: 4ey6), the best docked pose achieved an RMSD value of 0.27Å. This result shows that the MOLEGRO software effectively reproduced the crystal structure poses of the ligand, with all RMSD values below 2 Å71, confirming the reliability of the docking process (see Fig. 10).

Quality assessment and drug–likeness study.

To support the predicted biological activity and evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed molecules as potential proteasome inhibitors for cancer treatment, various parameters were calculated based on the binding energy and inhibition constant obtained from molecular docking studies performed using AutoDock Vina. The first equation is used to calculate ligand efficiency (LE), so that if LE is less than 0.350, it indicates that it is a lead–like molecule. The second equation gives the scaled ligand efficiency (LE_Scale), which allows for comparison independent of ligand size. A low value (less than 0.4) of LE_Scaled effectively suggests that the proposed molecules could be potential katG inhibitors. The third equation calculates the goodness of fit (FQ), defined as the ratio of LE to LE_Scale. An FQ value close to 1 indicates strong binding to the receptor. Another important parameter parameter is the lipophilicity depending on the efficiency of the ligand lipophilicity (LELP) where it must be greater than 3. A high value of LELP clearly indicates that the molecules have optimized affinity to lipophilicity72. According to Table 10, which summarizes the results of the calculation obtained for BPhIM, and APhIM of the preceding parameters show that the newly synthesized Schiff bases are promising inhibitory activity against acetylcholinesterase.

After confirming the efficacy and pharmacological activity of our molecules, we studied its ability to be an orally administered drug in humans based on Lipinski’s rule of five73. This rule is used in drug design to preselect molecules with favorable properties of absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) that a drug must have in the organism. These five rules can be outlined as follows: LogP must be less than 5, the number of hydrogen bond donors must be less than 5, the number of hydrogen bond acceptors must be less than 10, the number of rotatory bonds must be less than 10, and the molecular weight must not exceed 500 Da, in order to have a good oral bioavailability73. These characteristics could be obtained by using the online molecular properties calculator – Swiss ADME37 or Molinspiration website at (https://www.molinspiration.com/). As shown in Table 11, which summarizes the results obtained for our molecules, and by comparing with the Lipinski conditions, we concluded that the studied molecules satisfied the Lipinski rule. Consequently, these molecules show favorable inhibitory potential and are strong candidates for oral drugs.

Conclusion

The optimization of new two Schiff base compounds was demonstrated in this work using DFT method with the B97D3 functional at 6–311 + + G (d, p) basis set for comparing the experimental findings of the structural geometry, which indicated a strong agreement between them. The reduced density gradient (RDG) and the interaction region indicator (IRI) analyses provided quantitative overview of intermolecular interactions in the molecular structure and close contacts. They revealed that the structure of the compounds is stabilized by various intermolecular interactions. The HOMO and LUMO energies were used to estimate characteristics such as the energy gap, chemical hardness, and chemical softness. These predicted energies suggest that charge transfer takes place within the molecule. These parameters were also used to explore the reactivity of the molecules and chemical stability. The MEP map reveals that negative potential sites are on electronegative atoms and positive potential sites are around hydrogen atoms. According to NLO investigations, both compounds have significant NLO activity. The electric dipole moment, the polarizability and hyperpolarizability suggest that the derivatives studied could provide the basis for NLO materials. According to the previous results and molecular docking study, APhIM performed particularly well, with a score of −8.7 kcal/mol and a Ki of 0.42 µM for acetylcholinesterase (AChE), and − 8.3 kcal/mol/0.83 µM for butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), results that were significantly better than those for tacrine, which scored − 8. 1 kcal/mol/1.16 µM and − 7.7 kcal/mol/2.27 µM respectively. In terms of inhibition of carbonic anhydrases, the data show that BPhIM dominates, with a score of − 8.3 kcal/mol (Ki = 0.83 µM) for hCA I, and − 6.9 kcal/mol (Ki = 8.76 µM) for hCA II. By comparison, acetazolamide, considered to be a reference inhibitor of ACs, showed much lower affinities, with Ki values of 20.36 µM (hCA I) and 303.09 µM (hCA II). These in silico findings suggest these compounds are strong candidates for further experimental testing for the treatment of global disorders such as disorders including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), epilepsy, and glaucoma since they show higher binding affinities than the reference medications, tacrine and acetazolamide.

Data availability

The original data and contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Any further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

References

Khan, A., Dawar, P. & De, S. Thiourea compounds as multifaceted bioactive agents in medicinal chemistry. Bioorg. Chem., 108319. (2025).

Rao, D. P., Gautam, A. K., Verma, A. & Gautam, Y. Schiff bases and their possible therapeutic applications: A review. Res. Chem. 89, 101941 (2024).

Suhta, A. Investigating the new schiff base (E)-2-(((2-bromo-3-methylphenyl) imino) methyl)-4-methoxyphenol using Synthesis, XRD, DFT, FTIR spectroscopy, Hirshfeld, NBO, frontier molecular Orbitals, MEP and Electrophilicity-based charge transfer analysis. J. Chem. Soc. Pak., 45 (2023).

Mostefai, M. et al. Synthesis, structural analysis, and molecular Docking of a novel 1, 3, 4-thiadiazole derivative: an experimental and molecular modeling studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1319, 139308 (2025).

Boudjenane, F., Rahmani, R., Megrouss, Y., Chouaih, A. & Benhalima, N. DFT theoretical calculations on (Z)-2-hydroxy-N′-(4-oxo-1, 3-thiazolidin-2-ylidene) benzohydrazide as a methylene tetrahydrofolatereductase inhibitor: An in silico study, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations. Turk. Comput. Theor. Chem. 9, 90–114 (2025).

Benhalima, N. et al. Investigation of NLO properties and molecular Docking of 3, 5-dinitrobenzoic acid with some benzamide derivatives. Int. J. Comput. Mater. Sci. Eng. 13, 2350021 (2024).

Benhalima, N. et al. Electronic properties and nonlinear optical response of praziquantel hemihydrate and its derivatives: characterization via DFT, AIM, and RDG analysis. J. Opt. 96, 1–19 (2024).

Rahmani, R. et al. FTIR, NMR and UV–visible spectral investigations, theoretical calculations, topological analysis, chemical stablity, and molecular Docking study on novel bioactive compound: the 5-(5-Nitro Furan-2-Ylmethylen), 3-N-(2-Methoxy Phenyl), 2-N′-(2-Methoxyphenyl) Imino thiazolidin-4-One. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 43, 4685–4706 (2023).

Yaminaa, B. D. et al. X-ray structure and density functional theory investigations of 4-((2R)-2-(3, 4-dibromophenyl)-1-fluoro cyclopropyl)-N-(o-tolyl) benzamide compound. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 39, 1601–1614 (2020).

Ali, D. et al. Deciphering the role of flutamide, fluorouracil, and Furomollugin based ionic liquids in potent anticancer agents: quantum chemical, medicinal, molecular Docking and MD simulation studies. Results Chem. 13, 102029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem.2025.102029 (2025).

Arif, A. M. et al. Metal ions doped into Merocyanine form of coumarin derivatives: nonlinear optical molecular switches. J. Mol. Model. 25, 212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-019-4068-6 (2019).

Ali, D., Ali, M. A., Yousuf, A. & Xu, H. L. From charge transfer to sustainability: A multifaceted DFT approach to ionic liquid design. FlatChem 52, 100899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flatc.2025.100899 (2025).

Chetioui, S. et al. Synthesis, crystal structure, Hirshfeld surface analysis and experimental and theoretical study of new azo compound methyl 2-{2-[(E)-2-oxo-1, 2-dihydronaphthalen-1-ylidene] hydrazin-1-yl} benzoate. Cryst. Struct. Commun. 96, 81 (2025).

Zulfiqar, R. et al. Design and prediction physicochemical properties of piperazinium and Imidazolidinium based ionic liquids: A DFT and Docking studies. ChemistrySelect 10, e202405487. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202405487 (2025).

Yousuf, A., Ullah, A., Ul Hussain, S. Q., Ali, M. A. & Arshad, M. Spectroscopic studies and Non-Linear optical response through C/N replacement and modulation of electron Donor/Acceptor units on Naphthyridine derivatives. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 329, 125582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2024.125582 (2025).

Khan, F. T., Ibrahim, M., Yousuf, A. & Ali, M. A. Extrusion of carbon with SON in heterocycles for enhanced static and dynamic hyperpolarizabilities and light harvesting efficiencies. Chem. Phys. 596, 112761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemphys.2025.112761 (2025).

Manjula, R. et al. A comprehensive investigation into the spectroscopic properties, solvent effects on electronic properties, structural characteristics, topological insights, reactive sites, and molecular Docking of racecadotril: A potential antiviral and antiproliferative agent. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 102, 101702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jics.2025.101702 (2025).

Ram Kumar, A. et al. Experimental and theoretical investigations on antiproliferative compound nootkatone’s vibrational characteristics, solvent effects of electronic properties, topological insights, Hirshfeld surface, donor-acceptor insights, ADME, and molecular Docking against SMAD proteins. J. Mol. Struct. 1346, 143156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2025.143156 (2025).

Manjula, R. et al. Exploring structural and spectroscopic aspects, solvent effect (polar and non-polar) on electronic properties, topological insights, ADME and molecular Docking study of thiocolchicoside: A promising candidate for antiviral and antitumor pharmacotherapy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 331, 125807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2025.125807 (2025).

Kavi Karunya, S., Jagathy, K., Anandaraj, Pavithra, C. & Manjula, R. Exploration of solvent Effects, structural and spectroscopic Properties, chemical Shifts, bonding Nature, reactive sites and molecular Docking studies on 3-Chloro-2,6-Difluoropyridin-4-Amine as a potent antimicrobial agent. Int. Res. J. Multidisciplinary Technovation. 6, 109–127. https://doi.org/10.54392/irjmt2419 (2024).

Guendouzi, A. et al. Identification of tuberculosis inhibitors through QSAR-based virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulation of novel pyrimidine derivatives. J. Indian Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jics.2024.101298 (2024).

Guendouzi, A. et al. In-silico design novel phenylsulfonyl Furoxan and Phenstatin derivatives as multi-target anti-cancer inhibitors based on 2D-QSAR, molecular docking, dynamics and ADMET approaches. Mol. Simul. 50, 470–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927022.2024.2326180 (2024).

Frisch, M. et al. Gaussian 16 Software. Revision C. 01, Gaussian, Inc (CT, USA, 2016).

Dennington, R., Keith, T. A. & Millam, J. M. GaussView, Version 6.0. 16 (Semichem Inc Shawnee Mission KS, 2016).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate Ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys., 132 (2010).

Chai, J. D. & Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 6615–6620 (2008).

Krishnan, R., Binkley, J. S., Seeger, R. & Pople, J. A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 72, 650–654 (1980).

Jamróz, M. H. Vibrational energy distribution analysis (VEDA): scopes and limitations. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 114, 220–230 (2013).

Glendening, E. D. et al. NBO 7.0. Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin, Madison (2018).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated Docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791 (2009).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock vina: improving the speed and accuracy of Docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 (2010).

Akash, S. et al. Discovery of novel MLK4 inhibitors against colorectal cancer through computational approaches. Comput. Biol. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109136 (2024).

Paul, S. K., Guendouzi, A., Banerjee, A., Guendouzi, A. & Haldar, R. Identification of approved drugs with ALDH1A1 inhibitory potential aimed at enhancing chemotherapy sensitivity in cancer cells: an in-silico drug repurposing approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynamics. https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2023.2300127 (2023).

Design, L. Pharmacophore and ligand-based design with Biovia Discovery Studio®, BIOVIA (California, 2014).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7, 42717 (2017).

Pires, D. E. V., Blundell, T. L. & Ascher, D. B. PkCSM: predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using Graph-Based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 58, 4066–4072. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104 (2015).

Fejfarová, K., Dušek, M., Maghsodlou Rad, S. & Khalaji, A. D. E)-4-[(4-Bromophenyl) iminomethyl]-2-methoxyphenol. Struct. Rep. 68, o2466–o2466 (2012).

Apebende, C. G. et al. Density functional theory study of the influence of activating and deactivating groups on naphthalene. Results Chem. 4, 100669 (2022).

Aytac, S., Gundogdu, O., Bingol, Z. & Gulcin, İ. Synthesis of schiff bases containing phenol rings and investigation of their antioxidant capacity, anticholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase, and carbonic anhydrase Inhibition properties. Pharmaceutics 15, 779 (2023).

Govindarajan, M., Ganasan, K., Periandy, S. & Karabacak, M. Experimental (FT-IR and FT-Raman), electronic structure and DFT studies on 1-methoxynaphthalene. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 79, 646–653 (2011).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.464913 (1993).

Pearson, R. G. Absolute electronegativity and hardness: application to inorganic chemistry. Inorg. Chem. 27, 734–740. https://doi.org/10.1021/ic00277a030 (1988).

Kanis, D. R., Ratner, M. A. & Marks, T. J. Design and construction of molecular assemblies with large second-order optical nonlinearities. Quantum chemical aspects. Chem. Rev. 94, 195–242. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr00025a007 (1994).

Yang, W. & Mortier, W. J. The use of global and local molecular parameters for the analysis of the gas-phase basicity of amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 108, 5708–5711 (1986).

Pérez, P., Domingo, L. R., Duque-Noreña, M. & Chamorro, E. A condensed-to-atom nucleophilicity index. An application to the director effects on the electrophilic aromatic substitutions. J. Mol. Struct. (Thoechem). 895, 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theochem.2008.10.014 (2009).

Parr, R. G., Szentpály, L., Liu, S. & Index, E. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 121 1922–1924. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja983494x (1999).

Geerlings, P., De Proft, F. & Langenaeker, W. Concept. Density Funct. Theory Chem. Reviews, 103 1793–1874. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr990029p (2003).

Johnson, E. R. et al. Revealing noncovalent interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6498–6506 (2010).

Murray, J. S. & Sen, K. Molecular electrostatic potentials: concepts and applications, (1996).

Politzer, P. & Truhlar, D. G. Chemical applications of atomic and molecular electrostatic potentials: reactivity, structure, scattering, and energetics of organic, inorganic, and biological systems (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Mostefai, N. et al. Identification of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and stability analysis of THC@HP-β-CD inclusion complex: A comprehensive computational study. Talanta 286, 127370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2024.127370 (2025).

Benmohammed, A. et al. Synthesis, Characterization, linear and NLO properties of novel N-(2,4-Dinitrobenzylidene)-3-Chlorobenzenamine schiff base: combined experimental and DFT calculations. J. Electron. Mater. 50, 5282–5293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-021-09046-9 (2021).

Hadji, D. et al. Synthesis, NMR, Raman, thermal and nonlinear optical properties of dicationic ionic liquids from experimental and theoretical studies. J. Mol. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128713 (2020).

Fatima, Y. C., Hadji, D. & Nadia, B. Molecular structure, linear, and nonlinear optical properties of piperazine-1, 4-diium Bis 2, 4, 6-trinitrophenolate: a theoretical investigation. Phys. Chem. Res. 11, 33–48 (2023).

Bekki, Y., Hadji, D., Guendouzi, A., Houari, B. & Elkeurti, M. Linear and nonlinear optical properties of anhydride derivatives: A theoretical investigation. Chem. Data Collections https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cdc.2021.100809 (2022).

Brahim, H., Hadji, D., Zizi, Z., Guendouzi, A. & Boumediene, M. NBO, NLO and TD-DFT study of homoleptic iron complex derived from Dodecyl benzene sulfonate bidentate ligand. Chem. Data Collections. 57, 101186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cdc.2025.101186 (2025).

Schwenke, D. W. & Truhlar, D. G. Systematic study of basis set superposition errors in the calculated interaction energy of two HF molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 2418–2426 (1985).

Gutowski, M., van Duijneveldt-van, J. G., de Rijdt, J. H., van Lenthe, F. B. & van Duijneveldt Accuracy of the boys and Bernardi function counterpoise method. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 4728–4737 (1993).

Guendouzi, A., Mekelleche, S. M., Brahim, H. & Litim, K. Quantitative conformational stability host-guest complex of carvacrol and thymol with β-cyclodextrin: a theoretical investigation. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 89, 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10847-017-0740-6 (2017).

Guendouzi, O. et al. A quantum chemical study of encapsulation and stabilization of Gallic acid in < i > β-cyclodextrin as a drug delivery system. Can. J. Chem. 98, 204–214. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjc-2019-0464 (2020).

Kumar, S. & Kumar, S. Molecular docking: a structure-based approach for drug repurposing, In silico drug design, pp. 161–189 (Elsevier, 2019).

Salicari, L. & Trovato, A. Entangled motifs in membrane protein structures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 9193 (2023).

Belkhadem, F. et al. Synthesis, Pharmacological evaluation, and molecular Docking studies of some 1, 3, 4-oxadiazolyl-5-yl Thiones bearing halo-nitrophenyl Hydrazides derivatives as antioxidant and antimicrobial agents. J. Mol. Struct. 1329, 141389 (2025).

Yung-Chi, C. & Prusoff, W. H. Relationship between the Inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent Inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 22, 3099–3108 (1973).

Belhachemi, M. H. M. et al. Synthesis, structural determination, molecular Docking and biological activity of 1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-5-bromolindolin-2, 3-dione. J. Mol. Struct. 1265, 133342 (2022).

Cheung, J. et al. Structures of human acetylcholinesterase in complex with Pharmacologically important ligands. J. Med. Chem. 55, 10282–10286 (2012).

Nudelman, A. Hybrid/chimera drugs-part 1-drug hybrids affecting diseases of the central nervous system. Curr. Med. Chem. (2024).

Watkins, P. B., Zimmerman, H. J., Knapp, M. J., Gracon, S. I. & Lewis, K. W. Hepatotoxic effects of Tacrine administration in patients with alzheimer’s disease. Jama 271, 992–998 (1994).

Westermaier, Y., Barril, X. & Scapozza, L. Virtual screening: an in Silico tool for interlacing the chemical universe with the proteome. Methods 71, 44–57 (2015).

Jangam, C. S. et al. Pharmacoinformatics-based identification of anti-bacterial catalase-peroxidase enzyme inhibitors. Comput. Biol. Chem. 83, 107136 (2019).

Lipinski, C. A., Lombardo, F., Dominy, B. W. & Feeney, P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 64, 4–17 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their respective department.

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was received to support this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Oumria Kourat and Nadia Benhalima contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and original draft writing. Al-Anood M Al-Dies was involved in software development, validation, and review and editing of the manuscript. Abdelkrim Guendouzi contributed to formal analysis, methodology, and data curation. Zohra Douaa Benyahlou provided supervision, resources, and validation. Youcef Megrouss participated in data interpretation and review and editing. Mokhtaria Drissi and Emad Rashad Sindi assisted in investigation and visualization. Gizachew Alene Alem led project administration, supervision, and contributed to review and editing. Magdi E. A. Zaki was responsible for conceptualization, supervision, and manuscript review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors declare that this study did not involve any experiments on human participants or animals requiring ethical approval.

Consent for publication

The authors declare that consent for publication is not applicable.

Ethical approval

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Clinical trial

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kourat, O., Benhalima, N., Al-Dies, AA.M. et al. Structural, nonlinear optical, and molecular docking studies of schiff base compounds as multi-target inhibitors of AChE, BChE, and carbonic anhydrases. Sci Rep 15, 34818 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21241-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21241-w