Abstract

Cercospora leaf spot (CLS) is a major disease impacting global sugar beet cultivation and yield. This study investigated the potential diversity of Cercospora species causing CLS in Iranian sugar beet. Fungal isolates were characterized using integrated morphological and multi-gene sequence analyses. Subsequently, the possibility of rapid and specific diagnosis of the dominant pathogen using Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) was assessed. Infected leaves were collected from Ardabil, West Azerbaijan, Khorasan Razavi, Semnan, Mazandaran, Khuzestan, and Golestan provinces across the country. Genomic regions of actA, cmdA, gapdh, his3 and tef1 were amplified and sequenced. Phylogenetic results revealed that two species, Cercospora beticola and Cercospora gamsiana, are involved in causing cercospora leaf spot of sugar beet in Iran from which C. beticola was the dominant species. The LAMP-specific primers designed based on the gapdh gene region successfully discriminated C. beticola from C. gamsiana and other Cercospora species, as well as from some other fungal genera such as, Alternaria, Cladosporium, Curvularia, Ramularia and Stemphylium. The LAMP assay in this study demonstrated a detection limit of 50 fg μL−1. This study found C. beticola to be the dominant species in Iranian sugar beet fields. The LAMP technique proved effective for rapid, accurate diagnosis, aiding optimized disease management and control strategy selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.), a member of the family Amaranthaceae, is a globally significant crop cultivated primarily for its high sucrose content in the roots1. Sugar beet contributes substantially to the sugar industry, providing nearly 30% of global sugar production2. In Iran, sugar beet is a strategic agricultural commodity, with a cultivated area of 132,185 hectares under irrigation, producing 7,466,913 tons annually3. However, its productivity is threatened by various pathogens, including fungi, bacteria, viruses, and nematodes. Among these, Cercospora leaf spot (CLS), caused by Cercospora spp., is one of the most devastating diseases, leading to significant yield and quality losses4.

Cercospora is one of the 100 most cited fungal genera5. Traditionally, Cercospora taxonomy relied on morphological traits and host specificity, leading to over 3,000 described species6,7. Crous and Braun6 reviewed Cercospora species based on morphology and recognised 659 species. However, molecular phylogenetics has since reshaped the classification of Cercospora, revealing that many species with similar hosts or morphology are in fact distinct, while some species can infect multiple hosts8,9,10. Studies using ITS, tef1, act, cmd, his3, tub, rpb2 and gapdh gene regions revealed hidden diversity within C. beticola Sacc.8,9,10. Recent research identified additional species (e.g., C. americana Vaghefi, S.J. Pethybridge & R.G. Shivas, C. tecta Vaghefi, S.J. Pethybridge & R.G. Shivas) associated with CLS11. In Iran, only six isolates have been genetically characterized, with five identified as C. beticola and one as C. gamsiana Bakhshi & Crous 10,12.

Cercospora leaf spot is a polycyclic fungal disease that thrives under warm and humid conditions, causing necrotic leaf spots that reduce photosynthetic efficiency, root yield, and sugar content5,13,14. The pathogen produces conidia within seven days after infection, facilitating rapid disease spread15.Current management strategies to control the diseases are the use of certified seeds16, crop rotation17 and fungicide applications18. However, fungicide resistance in C. beticola populations has emerged due to overuse19,20. Traditional disease forecasting models, based on weather conditions, often lack accuracy21,22, necessitating advanced molecular detection methods for timely intervention.

Accurate pathogen identification is crucial for disease management23. In sugar beet, Alternaria alternata (Fr.) Keissl., Phoma betae A.B. Frank, and Ramularia beticola Fautrey & Lambotte are fungal pathogens often confused with C. beticola when accurate diagnostics are lacking24. Conventional PCR-based methods are time-consuming and require specialized equipment. In contrast, other new techniques such as Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) offer high sensitivity and specificity25; rapid detection (< 1 h)26 and visual results (colorimetric/fluorescence)27. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification uses Geobacillus stearothermophilus (Bst) DNA polymerase and six primers targeting conserved regions28, making it ideal for field diagnostics. Its application in detecting C. beticola could optimize disease management by enabling early fungicide application and reducing unnecessary chemical use.

This study aimed to characterize Cercospora isolates from major sugar beet growing regions in Iran using multi-locus phylogenetics and develop a LAMP-based assay for rapid and accurate detection of C. beticola. By integrating genomic tools and molecular diagnostics, this research will enhance CLS management, supporting sustainable sugar beet production.

Materials and methods

Sampling

Field surveys were conducted across sugar beet cultivations in multiple provinces of Iran; Khuzestan (Dezful, Shush and Andimeshk), West Azerbaijan (Khoy), Razavi Khorasan (Joveyn) Semnan (Meyami and Shahroud), Mazandaran (Behshahr), Ardabil (Moghan) and Golestan (Kordkuy and Kalaleh) during 2021–2023 to collect fungal isolates (Fig. 1). Leaves exhibiting symptoms of Cercospora-like leaf spots were sampled, placed in labeled paper bags and transported to the laboratory.

Fungal isolation, purification and morphological examinations

Samples were examined using a stereomicroscope Zeiss Stemi 305 (Oberkochen, Germany) for Cercospora-specific conidiophores and conidia. Single-spore isolation was performed directly from lesions as explained in Bakhshi et al.29, briefly; Malt Extract Agar (MEA, Merck, Germany) plates were slanted, supplemented with 10 mL sterile water, and conidial masses were transferred into the water phase, homogenized, and incubated overnight. Excess water was removed after 24 h, and germinated conidia were transferred to fresh MEA plates under sterile conditions. Shape and size of morphological structures of all fungal isolates including stromata, conidiophores, and conidia extracted from lesions examined using a Nikon Eclipse 80i light microscope (Tokyo, Japan). Pure cultures were maintained on MEA slants and sterile distilled water at 4–6 °C. Representative isolates were deposited in the Iranian Fungal Culture Collection (IRAN …C; Table 1).

DNA extraction, BOX fingerprinting and sequencing

DNA was extracted from all isolates using the method described by Möller et al.30. DNA quality was assessed by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel, while DNA quantity was measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). The initial concentration of all samples was adjusted to 50 ng μL−1. The BOX region was amplified for each isolate with the BOXA1R primer (5′- CTACGGCAAGGCGACGCTGACG-3′)31, following the PCR protocol and conditions outlined by Bakhshi et al.32. Initial classification of the recovered isolates was based on BOX-PCR banding patterns, supplemented by morphological characteristics and isolate origin. Representative isolates were then selected for further sequencing.

PCR and sequencing

Multiple genomic regions including actin (actA), calmodulin (cmdA), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapdh), histone (his3), and translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1) were amplified using specific primers provided in Supplementary Table 133,34,35. PCR amplification of the actA, gapdh, his3, cmdA, and tef1 genomic regions was performed in 25 μL reaction volumes containing 5–10 ng of genomic DNA, 1 × reaction buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 40 μM of each dNTP, 0.7 μL DMSO, 0.2 μM of each primer, 0.4 units of Taq DNA polymerase, and sterile deionized water, using a Bio-Rad thermocycler (North Carolina, USA). Thermal cycles consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 52 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 45 s with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min12. The gapdh gene was amplified using touchdown PCR conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; 5 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 59 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 2 min; 5 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 57 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 2 min; 30 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 52 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 2 min; with a final extension at 72 °C for 8 min11. PCR products were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels containing 0.5 μg mL−1 ethidium bromide (1% v/v). Following electrophoresis, DNA fragments were sized using a GeneRuler™ 1 kb DNA ladder (Sinacolon, Iran). PCR products were sequenced by Microsynth AG Company (Balgach, Switzerland).

Phylogeny

The resulting nucleotide sequences were blasted at the GenBank database and high-similarity sequences containing ex-type strains were downloaded and aligned with each other to make alignments. Individual gene alignments were performed using MAFFT v. 736 with manual editing in MEGA v. X 37 when necessary. For multi-gene analysis, individual gene alignments were concatenated using Mesquite v.3.8138. Bayesian inference was implemented in MrBayes v. 3.2.639 using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling. Four simultaneous chains were run from random starting trees with a heating parameter of 0.15 and default priors. For each dataset, two independent runs were executed, sampling every 1,000 generations until the average standard deviation of split frequencies reached 0.01. After discarding the initial 25% of sampled trees as burn-in, the remaining trees were used to generate a 50% majority-rule consensus phylogeny with posterior probability (PP) values. Resulting trees were visualized in Geneious v. 8.1.840 and finalized for publication using Adobe Illustrator 2024 Artwork v. 28.0. All new sequences were deposited in GenBank with accession numbers (Table 1).

LAMP primer design based on target genomic regions

For the development of LAMP-specific primers, nucleotide variation was initially analyzed in the amplified genomic regions (gapdh, tef1, his3, cmd, and actA) among fungal isolates through visual inspection using MEGA v. X software. Based on the observed nucleotide divergence between Cercospora species, the gapdh genomic region was selected for LAMP primer design. Primers were designed using the online tool Primer Explorer V5 (https://primerexplorer.jp/e/).

To assess the specificity of the designed LAMP primers (Table 2), reaction mixtures (Supplementary Table 2) were incubated at 65 °C for 45 min in a thermocycler. Sterile nuclease-free deionized water served as the negative control. The DNA concentration of all reactions was adjusted at 50 ng µL−1. For amplification verification, 5 μL of each reaction product was electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels containing 0.5 μg mL1 ethidium bromide. Following electrophoresis, amplification bands were visualized at 300 nm using a transilluminator and documented with a Gel Doc system (Bio-Rad). All reactions were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility; with band sizes determined using GeneRulerTM 1 kb DNA ladders. To rigorously evaluate primer specificity, a cross-reactivity test against six non-target fungal genera including Alternaria, Cladosporium, Curvularia, Ramularia, and Stemphylium was performed. Furthermore, to test the limit of detection (LOD) of LAMP assay designed in this study, genomic DNA from C. beticola (strain IRAN 5155C) as the representative isolate was serially diluted tenfold and amplification was conducted under the LAMP condition as described earlier and followed by electrophoresis.

Results

Isolates and preliminary examinations

Extensive field surveys conducted across major sugar beet growing regions of Iran, including Khuzestan, West Azerbaijan, Golestan, Razavi Khorasan, Semnan, Ardabil, and Mazandaran provinces, revealed widespread incidence of CLS disease. The characteristic symptoms appeared as numerous circular lesions (2–5 mm diameter) with distinctive coloration patterns: brown-gray centers surrounded by purple-to-burgundy margins (Fig. 2). In severe infections, coalescing lesions resulted in extensive leaf blight and necrosis. From these symptomatic plants, 283 fungal isolates were successfully isolated and morphologically identified as Cercospora species. Following comprehensive analysis incorporating BOX-PCR genotyping, morphological characterization, and geographical distribution patterns, a total of 61 representative isolates (Table 1) were selected for DNA sequencing studies. This selection strategy ensured optimal representation of both genetic diversity and geographical distribution across all surveyed regions.

Molecular identification and phylogenetic analysis of Cercospora isolates from Iranian sugar beet fields

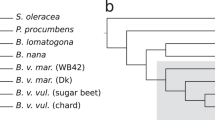

Phylogenetic analysis consisted of 105 Cercospora strains, including 46 reference sequences from NCBI and 59 isolates from this study, with Cercospora sorghicola CBS 136448 serving as the out-group. The final concatenated alignment comprised 1,974 characters, including alignment gaps. Model selection analysis determined GTR + G as the optimal substitution model for cmdA, HKY + G for actA and tef1, and GTR + I + G for his3 and gapdh gene regions, all with Dirichlet base frequencies. Bayesian inference of the 1,974 character dataset identified 513 unique site patterns, generating 412 phylogenetic trees through MCMC sampling. After discarding the initial 25% as burn-in, the 50% majority-rule consensus tree and posterior probabilities were calculated from the remaining 310 trees (Fig. 3).

The phylogenetic analysis revealed two distinct Cercospora species clades among the 62 Iranian isolates with high posterior probability: C. beticola (71% prevalence) and C. gamsiana (29% prevalence). Geographic distribution patterns showed C. beticola as the exclusive species in Khuzestan and Semnan provinces, while both species coexisted in West Azerbaijan, Ardabil, Golestan, Khorasan, and Mazandaran. These results conclusively demonstrate C. beticola as the dominant Cercospora species affecting sugar beet production across Iran, with C. gamsiana showing regional distribution in northern and western growing areas (Figs. 1 and 3).

Evaluation of primer specificity

The designed LAMP primers specifically amplified DNA from C. beticola, the predominant causal agent of Cercospora leaf spot in sugar beet, while successfully differentiating it from other Cercospora species (C. gamsiana, C. apii, C. cf. flagellaris, and Cercospora sp. G) and fungal genera (Alternaria, Cladosporium, Curvularia, Ramularia and Stemphylium). In triplicate testing, no amplification was observed in negative control (Fig. 4). The turbidity of positive reactions, resulting from DNA amplification of C. beticola isolates, was visually observed, confirming successful detection of the target pathogen by the LAMP assay without the need for electrophoresis (Fig. 4). Furthermore, in the sensitivity test employing a serial dilution of genomic DNA extracted from C. beticola (IRAN 5155C) as a representative strain, the LAMP assay demonstrated a detection limit of 50 fg μL⁻1 in this study (Fig. 5).

Results of DNA amplification using LAMP primers specific to C. beticola showing: (1) GeneRuler™ 1 kb DNA ladder, (2) C. beticola IRAN 5144C, (3) C. beticola IRAN 5149C, (4) C. beticola IRAN 5153C, (5) C. beticola IRAN 5157C, (6) C. beticola IRAN 5145C, (7) C. beticola IRAN 5148C, (8) C. gamsiana IRAN 5143C, (9) GeneRuler™ 1 kb DNA ladder, (10) C. gamsiana IRAN 5148C, (11) C. cf. flagellaris IRAN 2720C, (12) Cercospora sp. G IRAN 4098C, (13) Cercospora apii IRAN 2655C, (14) Alternaria atra IRAN 4671C, (15) GeneRuler™ 1 kb DNA ladder, (16) Stemphylium vesicarium IRAN 4667C, (17) Curvularia inaequalis IRAN 4792C, (18) Ramularia lamiigena IRAN 3980C, (19) Cladosporium macrocarpum IRAN 4654C and (20) negative control. The results demonstrate exclusive amplification in C. beticola samples (lanes 2–7) with no cross-reactivity observed in other Cercospora species or fungal genera, confirming the high specificity of the designed primers. Negative control (lane 20) showed no amplification, validating the assay’s reliability.

Lanes 1–10 indicate the sensitivity of LAMP amplification using a ten-fold serial dilution of C. beticola IRAN 5155C genomic DNA, ranging from 50 ng μL−1, 5 ng μL−1, 500 pg μL−1, 50 pg μL−1, 5 pg μL−1, 500 fg μL−1, 50 fg μL−1, 5 fg μL−1, 500 ag μL−1, and 50 ag μL−1, respectively. Lane M contains the GeneRuler™ 1 kb DNA ladder (MBI Fermentans, Vilnius, Lithuania) as a molecular size marker.

Discussion

Cercospora leaf spot (CLS) demonstrates higher prevalence in regions with warm and humid climates during the sugar beet growing season24. In Iran, the disease shows significant incidence in several areas, particularly Khuzestan, Ardabil, and Golestan provinces. This pattern of distribution results from the confluence of three key factors: favorable environmental conditions, the persistent presence of pathogenic inoculums, and the widespread cultivation of susceptible cultivars across multiple growing seasons.

Through comprehensive molecular and morphological analyses of 283 isolates collected from seven Iranian provinces, this study successfully identified and differentiated two fungal species, C. beticola and C. gamsiana, as the causal agents of CLS in sugar beet. Sequencing of five genomic regions and phylogenetic analysis of 62 selected isolates revealed that while these species share some morphological characteristics, they are genetically distinct (Fig. 3).

Cercospora beticola was identified as the dominant species with a frequency of 71% across all study regions whereas C. gamsiana was primarily observed in northern regions (particularly Ardabil, Golestan, Mazandaran, and West Azerbaijan provinces) with a frequency of 29%. Notably, no C. gamsiana isolates were detected in Khuzestan or Semnan provinces. This geographical distribution pattern likely reflects ecological and climatic differences between regions, with northern areas (characterized by higher relative humidity and more moderate temperatures) appearing more favorable for C. gamsiana growth and spread.

Recent studies have reported several other Cercospora species as causal agents of CLS worldwide, including C. americana, C. apii Fresen., C. cf. flagellaris, Cercospora sp. G, C. tecta and C. zebrina Pass.11. Cercospora gamsiana was first isolated and reported from weeds in northern Iran10 and given that C. beticola has also been previously isolated from various broadleaf weeds8,9,41, it appears that weeds play a crucial role in maintaining pathogenic inoculums and facilitating its transmission to sugar beet fields. This transmission may occur through wind, rain, or other means such as movement of agricultural equipment or farm labor.

The most significant and novel finding of this study is the first report of the relatively widespread presence and pathogenicity of C. gamsiana on sugar beet in Iran. This finding is particularly important as C. beticola was previously considered the sole significant causal agent of CLS on sugar beet. The identification of C. gamsiana as a prevalent pathogen on sugar beet may explain some failures in disease control programs in northern regions of the country, as this species may differ from C. beticola in terms of pathogenicity characteristics, host range, and sensitivity to fungicides. Consequently, further studies are needed to better understand the biological properties, damage potential, and responses to chemical and non-chemical control methods for C. gamsiana.

Molecular analysis of this study revealed the gapdh gene as the most variable between species, making it ideal for designing specific LAMP primers. Laboratory tests demonstrated these primers could distinguish C. beticola from C. gamsiana and other fungi with high sensitivity (detecting nanogram DNA amounts) within 45 min (Fig. 4). This represents a significant improvement over traditional morphological identification methods that take long time and are susceptible to growth conditions and observer bias. In the only study conducted to develop a LAMP assay for detecting C. beticola based on the ITS-rDNA and CbCyp51 genes, C. beticola and its resistant isolates were successfully identified, respectively24. However, the ITS-rDNA region is unsuitable for discriminating Cercospora species in sugar beet due to its low genetic variability8,9,10,42.

Our study achieved a detection limit of 50 fg μL−1 through LAMP primers targeting the gapdh gene, demonstrating both high sensitivity and specificity in discriminating C. beticola from C. gamsiana and other fungal genera without observable cross-reactivity (Fig. 5). While Shrestha et al.24 similarly developed an effective LAMP assay using ITS-rDNA targets, their reported sensitivity of 100 fg μL−1 and the inherent conservation of ribosomal DNA sequences limited the assay’s ability to differentiate between closely related Cercospora species. These findings hold particular significance for regions with complex Cercospora populations, where the gapdh-based LAMP assay emerges as a more robust diagnostic tool for accurate pathogen identification and subsequent disease management optimization.

Given the significant impact of Cercospora leaf spot on sugar beet yield and quality (with reported losses up to 50% in some cases), the findings of this study could substantially enhance integrated disease management strategies. The rapid and accurate identification of pathogenic species in different regions enables more targeted control approaches, including: (1) deployment of resistant cultivars, (2) optimized fungicide application schedules, and (3) selection of most effective chemical treatments. Furthermore, the ability to quickly monitor fungal populations during the growing season allows for better prediction of critical disease outbreak periods and facilitates timely intervention measures.

Data availability

All sequence data from this study (Table 1) are publicly available in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank) and can also be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Draycott, A. P. Sugar beet (Blackwell Publishing, 2006).

FAO. faostat. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL. (2022).

Anonymous. Agricultural Jihad Ministry. agrieng.org (2023).

Weiland, J. & Koch, G. Sugarbeet leaf spot disease (Cercospora beticola Sacc.). Mol. Plant Pathol. 5, 157–166 (2004).

Bhunjun, C. S. et al. What are the 100 most cited fungal genera?. Stud. Mycol. 108, 1–412 (2024).

Crous, P.W. & Braun, U. Mycosphaerella and its anamorphs: 1. Names published in Cercospora and Passalora. Utrecht, the Netherlands, Fungal Biodiversity Centre, 571 (2003).

Chupp, C. A monograph of the fungus genus Cercospora. Ithaca, New York (1954).

Groenewald, J. Z. et al. Species concepts in Cercospora: spotting the weeds among the roses. Stud. Mycol. 75, 115–170 (2013).

Bakhshi, M. et al. Application of the consolidated species concept to Cercospora spp. from Iran. Persoonia 34, 65–86 (2015).

Bakhshi, M., Arzanlou, M., Babai-Ahari, A., Groenewald, J. Z. & Crous, P. W. Novel primers improve species delimitation in Cercospora. IMA Fungus 9, 299–332 (2018).

Vaghefi, N., Shivas, R. G., Sharma, S., Nelson, S. C. & Pethybridge, S. J. Phylogeny of cercosporoid fungi (Mycosphaerellaceae, Mycosphaerellales) from Hawaii and New York reveals novel species within the Cercospora beticola complex. Mycol. Prog. 20, 261–287 (2021).

Bakhshi, M. & Zare, R. Development of new primers based on gapdh gene for Cercospora species and new host and fungus records for Iran. Mycol. Iran. 7, 63–82 (2020).

Shane, W. W. & Teng, P. S. Impact of Cercospora leaf spot on root weight, sugar yield and purity. Plant Dis. 76, 812–820 (1992).

Franc, G. Ecology and epidemiology of Cercospora beticola. Cercospora leaf spot of sugar beet and related species. Am. Phytopathol. Soc., St. Paul, Minnesota 7–19 (2010).

Bolton, M. D., Birla, K., Rivera-Varas, V., Rudolph, K. D. & Secor, G. A. Characterization of CbCyp51 from field isolates of Cercospora beticola. Phytopathology 102, 298–305 (2012).

Windels, C. E., Lamey, H. A., Hilde, D., Widner, J. & Knudsen, T. A Cercospora leaf spot model for sugar beet: In practice by an industry. Plant Dis. 82, 716–726 (1998).

Miller, J., Rekoske, M. & Quinn, A. Genetic resistance, fungicide protection and variety approval policies for controlling yield losses from Cercospora leaf spot infections. J. Sugar Beet Res. 31, 7–12 (1994).

Secor, G. A., Rivera, V. V., Khan, M. & Gudmestad, N. C. Monitoring fungicide sensitivity of Cercospora beticola of sugar beet for disease management decisions. Plant Dis. 94, 1272–1282 (2010).

Birla, K., Rivera-Varas, V., Secor, G. A., Khan, M. F. & Bolton, M. D. Characterization of cytochrome b from European field isolates of Cercospora beticola with quinone outside inhibitor resistance. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 134, 475–488 (2012).

Bolton, M. D. et al. RNA-sequencing of Cercospora beticola DMI-sensitive and-resistant isolates after treatment with tetraconazole identifies common and contrasting pathway induction. Fungal Genet. Biol. 92, 1–13 (2016).

Khan, J., Del Río, L., Nelson, R. & Khan, M. Improving the Cercospora leaf spot management model for sugar beet in Minnesota and North Dakota. Plant Dis. 91, 1105–1108 (2007).

Pethybridge, S. J. et al. Improving fungicide-based management of Cercospora leaf spot in table beet in New York, USA. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 41, 1–4 (2019).

Crous, P. W., Hawksworth, D. L. & Wingfield, M. J. Identifying and naming plant-pathogenic fungi: Past, present, and future. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 53, 247–267 (2015).

Shrestha, S. et al. Rapid detection of Cercospora beticola in sugar beet and mutations associated with fungicide resistance using LAMP or probe-based qPCR. Plant Dis. 104, 1654–1661 (2020).

Notomi, T. et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, e63 (2000).

Tomita, N., Mori, Y., Kanda, H. & Notomi, T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of gene sequences and simple visual detection of products. Nat. Protoc. 3, 877–882 (2008).

Mori, Y., Nagamine, K., Tomita, N. & Notomi, T. Detection of loop-mediated isothermal amplification reaction by turbidity derived from magnesium pyrophosphate formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 289, 150–154 (2001).

Nagamine, K., Hase, T. & Notomi, T. Accelerated reaction by loop-mediated isothermal amplification using loop primers. Mol. Cell. Probes 16, 223–229 (2002).

Bakhshi, M., Zare, R., Jafary, H., Arzanlou, M. & Rabbani-nasab, H. Phylogeny of three Ramularia species occurring on medicinal plants of the Lamiaceae. Mycol. Prog. 20, 27–38 (2021).

Möller, E. M., Bahnweg, G., Sandermann, H. & Geiger, H. H. A simple and efficient protocol for isolation of high molecular weight DNA from filamentous fungi, fruit bodies, and infected plant tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 6115 (1992).

Versalovic, J. Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction. Methods Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 25–40 (1994).

Bakhshi, M., Ebrahimi, L., Zare, R., Arzanlou, M. & Kermanian, M. Development of a novel diagnostic tool for Cercospora species based on BOX-PCR system. Curr. Microbiol. 79, 290 (2022).

Carbone, I. & Kohn, L. M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 91(3), 553–556 (1999).

Crous, P. W. et al. Cryptic speciation and host specificity among Mycosphaerella spp. occurring on Australian Acacia species grown as exotics in the tropics. Stud. Mycol. 50, 457–469 (2004).

O’Donnell, K., Cigelnik, E. & Nirenberg, H. I. Molecular systematics and phylogeography of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia 90, 465–493 (1998).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549 (2018).

Maddison, W. P. & Maddison, D. R. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Mesquite Project 11, 31 (2023).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012).

Drummond, A. J. et al. Geneious v5.6 2012.

Knight, N. L., Vaghefi, N., Kikkert, J. R. & Pethybridge, S. J. Alternative hosts of Cercospora beticola in field surveys and inoculation trials. Plant Dis. 103, 1983–1990 (2019).

Chen, Q. et al. Genera of phytopathogenic fungi: GOPHY 4. Stud. Mycol. 101, 417–564 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization (AREEO), Tehran, Iran for financial support.

Funding

No funding has been received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and M.B.; methodology, K.K., M.B., M.G. and MA.TG; software, M.B. and K.K.: validation, K.K., M.B., R.Z., H.J. and B.M.; formal analysis, K.K. and M.B.; writing original draft preparation, K.K. and M.B.; writing, review and editing, R.Z., H.J., MA.TG., M.G. and B.M.; project administration, K.K., M.B. and H.J.; funding acquisition, M.B. and H.J.; All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bakhshi, M., Ghasemi, M., Ghanbary, MA.T. et al. Uncovering Cercospora species affecting sugar beet in Iran with rapid and accurate detection of C. beticola using LAMP assay. Sci Rep 15, 34096 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21274-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21274-1