Abstract

Streptococcus suis is a zoonotic pathogen that causes invasive infections in individuals who are in close contact with infected pigs or contaminated pork-derived products. An unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 (sequence type 221) was first isolated from a human in Thailand in 2015; however, the mechanisms underlying host-cell interactions and virulence in animal models of this serotype are still limited. This study aimed to determine the virulence of the human unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 using in vitro (A549 epithelial cells) and in vivo (C57BL/6 mouse) models. The adhesion rate of the unencapsulated strain 43640 to A549 cells was significantly lower than that of the highly pathogenic S. suis serotype 2 strain P1/7 after infection at multiplicity of infection (MOI) 1 (p < 0.01) and MOI 10 (p < 0.05). The invasion of epithelial cells by S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 was significantly higher than that of serotype 2 strain P1/7 and the reference strain 92-4172 4 h after infection. S. suis serotypes 31 and 2 significantly induced cytotoxicity in epithelial cells by more than 50% and 90%, respectively, after 4 h and 18 h of infection. S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 induced apoptosis in A549 cells via a caspase 9-dependent pathway. Using an in vivo mouse model, we demonstrated that S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 induced 13.33% and 46.67% mortality due to septicemia after 24 h and 48 h, respectively. Bacterial counts in the blood of mice infected with strain 43640 were significantly lower than those in mice infected with the reference strain 12 h and 24 h after infection (p < 0.05). This study provides information on serotype 31-ST221 virulence in in vitro and in vivo models and proves that ST221 (CC221/234), an emerging human S. suis clone in Thailand, is potentially virulent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Streptococcus suis (S. suis) is a zoonotic pathogen that affects individuals in close contact with infected pigs or pork-derived products1. Although S. suis infection in humans is an occupational disease in industrialized countries, it is more commonly found to be a foodborne infection in Southeast Asia, mainly in Thailand and Vietnam, and the proportion of patients with occupational exposure is lower than that in Europe. The consumption of meals containing raw pork meat, blood, and other related products poses the main risk of transmission of S. suis infection in these countries2. A study in Thailand showed that S. suis human infections are responsible for an estimated USD 11.3 million loss in productivity-adjusted life years in the gross domestic product, which is equivalent to a loss of USD 36,033 per person3.

Almost all human S. suis cases worldwide are caused by strains of either serotype 2 or 144. In Thailand, human cases of serotypes 1, 4, 5, 9, 14, 24, and 31 have been reported5,6,7,8,9. Furthermore, serotype 31, which was isolated from a 55-year-old male alcohol misuser with liver cirrhosis in Thailand8, was unexpectedly unencapsulated, and sequence type (ST) 221 belonged to the clonal complex (CC) 221/2348. Notably, ST 221 is found exclusively in Thailand7,8,10,11,12. In a previous study, two human cases of S. suis serotype 24 ST 221, which belonged to CC 221/234, were reported10. To date, seven cases of human infection with S. suis CC221/234 strains have been documented. Of these, five were associated with serotype 24, whereas the remaining two involved serotypes 5 and 317,8,10–12. In addition, several studies on pigs in Thailand and other countries have revealed the isolation of S. suis serotype 31 strains from diseased pigs13,14,15,16,17. The prevalence of S. suis serotype 31 in diseased pigs in the Czech Republic was 3.4% between 2018 and 2022 18. Another study suggested that the prevalence of serotype 31 strains isolated from diseased pigs in Québec, Canada, was 1.1% and 0.5% in 2009 and 2010, respectively19. Most of these show multidrug resistance13,16,17,20. Interestingly, 31 S. suis serotype strains isolated from one human and 17 clinically asymptomatic pigs in Thailand were multidrug-resistant and resistant to azithromycin (100%; 18/18) and tetracycline (100%; 18/18). Notably, 10 (55.56%) of the serotype 31 strains were resistant to penicillin12. Apart from a few epidemiological reports, knowledge regarding the virulence and pathogenesis of S. suis serotype 31 remains limited and requires further investigation. Several studies on S. suis virulence and pathogenesis have been conducted using serotype 2 strains21,22,23. Knowledge regarding the mechanisms of virulence, including adhesion, invasion, and destruction of host cells, as well as animal models of non-serotype 2 strains, remain limited. In the case of serotype 31, only one study from China has revealed that a porcine S. suis serotype 31 (strain 11LB5) was virulent in a mouse model24. In this study, we investigated the pathogenic characteristics of the human unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31 ST221 strain using in vitro and in vivo models. Our findings will help us understand the mechanisms underlying S. suis serotype 31 virulence.

Materials and methods

Cell line and bacterial strain

Human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (A549) (ATCC, CCL-185) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). A549 cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 medium (Gibco Life Technologies Corporation, Grand Island, NY, USA). Culture media was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL of penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Gibco) and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 until confluence was reached.

The unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31 ST221 strain 436408, belonging to CC221/234 and isolated from a human patient in Thailand, was used to investigate virulence in the current study (accession number SAMN46861206). Highly pathogenic S. suis serotype 2 ST1, belonging to the CC1 strain P1/7 isolated from pigs, was used as a positive control for comparison with serotype 31 strain 43640 in in vitro studies (accession number SAMEA2298930). S. suis serotype 31 ST70 reference strain 92-4172, isolated from pigs, was used as a control in the in vitro and in vivo studies for comparison (accession number AB737835).

Biofilm formation assay

Biofilm formation by S. suis strain 43640, reference strain 92-4172, and P1/7 strains was assessed using Congo red agar (CRA) assay as described previously25. Briefly, bacterial strains were cultured on CRA made of brain-heart infusion agar (supplemented with 36 g/L sucrose and Congo red dye 0.8 g/L), incubated, and observed at 24, 48, and 72 h. Biofilm production was characterized based on six color tones of colonies as follows: very black, black, and almost black, which were interpreted as strong, moderate, and weak biofilm producers, respectively. Non-biofilm production was shown on three color tones of colonies as follows: Bordeaux, red, and very red25.

To confirm biofilm formation, a crystal violet assay was performed as described elsewhere26 with some modifications. Briefly, S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640, reference strain 92-4172, and serotype 2 strains were cultured on sheep blood agar at 37 °C. A single colony of the S. suis strain was diluted to an optical density (OD)600 of 0.1 in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (HiMedia, India) and incubated in a 96-well plate (Thermo Scientific, Roskilde, Denmark) for 24, 48, and 72 h at 37 °C. Non-adhering bacteria were removed, aspirated, and washed thrice with phosphate buffer saline (PBS; pH 7.4). The samples were then stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 10 min. Next, the wells were washed thrice with PBS and aspirated. Subsequently, 200 µL of 33% (v/v) glacial acetic acid was added and incubated for 15 min. Biofilm levels were determined using OD595. The ODs of these isolates were determined as the mean absorbance and compared with that of the negative control (ODnc). Biofilm production was characterized based on the categories of in vitro biofilm formation: no biofilm production (ODs ≤ ODnc), weak biofilm production (ODnc < ODs ≤ 2 ODnc), moderate biofilm production (2 ODnc < ODs ≤ 4 ODnc), and strong biofilm production (4 ODnc < ODs).

Cell cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxic effects of S. suis serotype 31 (strain 43640) and the highly pathogenic S. suis serotype 2 strain P1/7 were examined27. Briefly, the A549 cells were infected with either multiplicity of infection (MOI) 1 (∼1 × 104 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL), 10 (∼1 × 105 CFU/mL), or 100 (∼1 × 106 CFU/mL) in culture medium for 2, 4, or 18 h, and subsequently, the effect of S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 and serotype 2 strain P1/7 infection on A549 cells was determined using the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan).

Adhesion assay

The adhesion of unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640, reference strain 92-4172, and serotype 2 strain P1/7 to human lung epithelial (A549) cells was examined27. One milliliter of A549 cells was seeded at the density of 1 × 104 cells/well in 6-well tissue culture plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) and incubated until confluence was reached. The mid-log phase culture of bacteria was centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 5 min, washed twice using 1× PBS, pH 7.5, resuspended in complete media, and co-cultured with A549 cells at an MOI of 1 (1 × 104 CFU/mL) or 10 (1 × 105 CFU/mL) for 2 h. Non-adherent cells were removed by washing five times with 1× PBS. Bacterial adherence and internalization were assessed after lysing with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Merck, Millipore, MA, USA) for 3 min with agitation at 125 rpm. The number of CFU was determined using the spread plate technique on BHI agar (Becton Dickinson and Company, Le Pont de Claix, France).

Giemsa staining

Morphology of the A459 cells after infection with the S. suis strain 43640, reference strain 92-4172, and P1/7 was observed using a light microscope27. Briefly, a sterile coverslip was placed in each well of a 6-well plate before 1 × 104 cells/well. Epithelial cells were co-cultured with S. suis strains 43640 and P1/7 at an MOI of 1 (1 × 104 CFU/mL) or 10 (1 × 105 CFU/mL) for 2 h. Thereafter, the coverslip from each well was washed five times with 1× PBS. The samples were then fixed with 1 mL methanol (V.S. Chem House, Bangkok, Thailand) for 1 min and stained with Giemsa (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) for 3 min. The coverslip was mounted onto a glass slide and viewed under 100× magnification of a light microscope.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Morphology of the A459 cells after infection with S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640, reference strain 92-4172, and reference strain 2 (P1/7) was observed using SEM27,28. A549 cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in 6-well plates with glass slides covering the wells. The epithelial cells were co-cultured with exponential phase S. suis at an MOI of 10 (1 × 106 CFU/mL) for 2 h. The glass slides were washed five times with 1× PBS and fixed overnight with 4% formaldehyde. The slides were dehydrated using an ethanol series (10%, 25%, 30%, 35%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 100%), placed on SEM stubs, and coated with a thin layer of gold-palladium before observation using a JSM-IT200 scanning electron microscope (JSM-IT510 SEM, JEOL, Japan).

Invasion assay

The invasion of A549 cells by unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640, reference strain 92-4172, and serotype 2 strain P1/7 was determined27. Monolayers of A549 cells were co-cultured with S. suis strains 43640 and P1/7 at MOI of 1 and 10, as described previously for the bacterial adhesion assay. At 2–4 h post-infection, the supernatant and extracellular bacteria were gently aspirated. The co-cultured cells in each well were washed three times and treated with 100 µg/mL gentamicin and 5 µg/mL penicillin G to kill residual extracellular S. suis for another 2 h. The cell monolayers were then washed and lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 (MERCK Millipore, MA, USA) for 3 min with shaking at 125 rpm to remove intracellular bacteria. The intracellular bacteria were quantified using the plate count method on BHI agar plates after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C.

Apoptosis assay

An annexin V-FITC apoptosis kit (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) was used to detect apoptosis or necrosis of A549 cell after infection with S. suis isolates29. The A549 cells were infected with S. suis strains 43640 and P1/7 at MOI 1 (∼1 × 105 CFU/mL) or 10 (∼1 × 106 CFU/mL) in culture medium for 2 h. Pelleted cells were stained with annexin V‑fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and propidium iodide (PI) for 10‑15 min at room temperature in the dark prior to analysis using flow cytometry (BD Biosciences San Jose, CA, USA). Annexin V FITC/PI plots from the gated cells showed the populations corresponding to intact cells and non-apoptotic (annexin V–PI–), early apoptotic cells (annexin V + PI–), late apoptotic cells (annexin V + PI+), and necrotic cells (annexin V–/PI+).

Assessment of caspase activation using Western blot analysis

Caspase expression was measured using western blot analysis. A549 cells were infected with S. suis strains 43640 and P1/7 at an MOI of 1 (1 × 105 CFU/mL) or 10 (1 × 106 CFU/mL). The harvested cells were lysed using lysis buffer. Total protein concentration in the cell lysate was determined using the Bradford assay30. Cell lysates were separated using 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in 0.1% Tween 20-PBS at 37 °C for 1 h, followed by incubation with the corresponding primary antibodies against β‑actin, caspase 9, and caspase 3 overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were then washed with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies (anti-mouse or anti-rabbit; 1:10,000). The bound secondary antibody- horseradish peroxidase (POD) conjugates were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), quantified using densitometry (ImageQuant LAS 4000; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Chalfont, UK), and analyzed using Scion Image (version 4.0.2; Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD, USA). Data for each protein expressed were normalized to β‑actin expression.

In vivo infection studies

A mouse infection model was used to validate the virulence of S. suis serotype 31 reference strain 92-4172 and S. suis serotype 31 unencapsulated strain 43640. In total, 30 6-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (Charles Rivers) (n = 15 per group) were maintained at 22 °C and exposed to 12 h light/dark cycles with free access to food and water. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 1 × 108 CFU. All mice were observed at least three times daily until 72 h post-infection and twice thereafter until the end of the experiment (7 days post-infection) for the development of clinical signs of sepsis, such as depression, swollen eyes, rough hair coat, prostration, and lethargy. For bacteremia studies, 5 µL of blood were collected from the caudal vein of surviving mice at 12 and 24 h post-infection and proper dilutions were plated on Todd Hewitt broth agar (THA, Becton–Dickinson, Mississauga, ON, Canada).

Results

Biofilm production by the unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31

Polysaccharide production by the biofilm-forming strain was analyzed using the Congo red agar assay. Compared to serotype 2, the 43640 strain produced a strong biofilm after 24 h of incubation; however, serotype 2 showed the strongest biofilm formation at 48 h (Table 1). S. suis biofilm formation was assayed using crystal violet staining. As shown in Table 1, the capacity to produce biofilms was higher in S. suis serotype 31 than in the encapsulated serotype 2 (P1/7) and reference strain 92-4172 after 24 h of incubation in both assays (Table 1). All strains showed strong biofilm-forming capacity after 48 h and 72 h of incubation in Congo red agar and crystal violet staining assays.

Toxicity of the unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31

The effects of S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 (ST221) and serotype 2 strain P1/7 (ST1) on A549 cell viability were determined using the CCK-8 assay. A549 epithelial cells were infected with either strain at MOI of 1 (1 × 104 CFU/mL), 10 (1 × 105 CFU/mL), or 100 (1 × 106 CFU/mL) in the culture medium for 2 h (Fig. 1A), 4 h (Fig. 1B), or 18 h (Fig. 1C). The cytotoxic effects of S. suis strains 43640 and P1/7 on the epithelial cells increased in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 1). Both strains showed 100% cytotoxicity in A549 cells (Fig. 1C). In addition, the cytotoxic effect of serotype 2 strain P1/7 was significantly higher than that of S. suis strain 43640 after shorter incubation times (2 h and 4 h).

Cytotoxic effect of different concentrations of S. suis serotype 31 (SS31) and S. suis serotype 2 (SS2 (P1/7)) on cell viability after (A) 2, (B) 4, or (C) 18 h of treatment. Cell cytotoxicity rate (%) is expressed as the mean ± SD.*p < 0.05 or *** p < 0.001 indicates significant difference between the cytotoxicity rate of cells after infection with S. suis serotype 31 strain compared to that after infection with the S. suis serotype 2 (P1/7) strain.

Adhesion of the unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31

A549 cells were infected with S. suis strain 43640, reference strain 92-4172, or P1/7 at an MOI of 1 (1 × 104 CFU/mL) and 10 (1 × 105 CFU/mL) in culture medium for 2 h under non-toxic conditions. The percentage of A549 cell adhesion after exposure to the strain 43640 at MOI 1 was 36.11 ± 7.88%, while it increased to 79.44 ± 7.52 after exposure at MOI 10 (Fig. 2). Figure 2 shows that the adhesion rate of S. suis strain 92-4172 at MOI 1 and MOI 10 were 16.28 ± 0.86% and 35.56 ± 3.85%, respectively. The percentages of A549 cell adhesion after exposure to strain P1/7 at MOI 1 or MOI 10 for 2 h were 77.93 ± 2.61% and 101.89 ± 13.93%, respectively (Fig. 2). Strain P1/7 adhered significantly more to epithelial cells than strains 43640 and reference strain 92-4172 at both MOI 1 and MOI 10. Bacterial adherence was determined using Giemsa staining and assessed using SEM after exposure to both strains at MOI 1 or MOI 10 for 2 h. The results showed that both strains adhered to A549 cells, consistent with the results of the adhesion assay (Figs. 3 and 4). However, S. suis serotype 2 strain P1/7 showed higher adhesion to A549 cells than strain 43640 and reference strain 92-4172 (Figs. 3 and 4). Morphological observations using SEM indicated membrane reorganization and protrusion of the epithelial cell surface after A549 cells were infected with S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 and reference strain 92-4172 (Fig. 4).

Effect of S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 (SS31 (43640)), reference strain 92-4172 (SS31 (92-4172)), and S. suis serotype 2 (P1/7) (SS2 (P1/7)) on A549 cell adhesion. Cell adhesion rate (%) is expressed as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 or ** p < 0.01 indicates significant difference between cell adhesion rate of A549 cells infected with SS31 strain compared to that of cells infected with reference strain 92-4172 and SS2 (P1/7) strain.

Scanning electron microscopy showing S. suis serotype 31 (SS31 (43640)), reference strain 92-4172 (SS31 (92-4172)), and S. suis serotype 2 (P1/7) adhered to A549 cells; bars: 1, 2, or 5 μm. The yellow arrow indicates membrane reorganization of the cell surface after S. suis serotype 31 infection of A549 cells. Uninfected A549 cells were used as controls.

Invasion of unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31

The percentage of A549 cell invasion after exposure to S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 at a MOI of 1 was 0.13 ± 0.06%, while it decreased to 0.08 ± 0.02 after exposure to a MOI of 10 (Fig. 5A). The percentages of A549 cell invasion after exposure to S. suis serotype 2 strain P1/7 at MOI 1 or MOI 10 were 1.32 ± 0.23% and 0.79 ± 0.07%, respectively after 2 h of infection (Fig. 5A). Figure 5A shows that S. suis strain 92-4172 did not invade the epithelial cells 2 h post-infection. After 4 h of infection, the percentages of A549 cell invasion after exposure to S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 at MOI 1 or MOI 10 were 73.89 ± 2.55% and 28.33 ± 1.67%, respectively, while the percentages of A549 cell invasion after exposure to S. suis serotype 2 strain P1/7 at MOI 1 or MOI 10 were 54.78 ± 4.30% and 8.75 ± 1.25%, respectively. Figure 5B shows that the invasion rate of S. suis strain 92-4172 at MOI 1 and MOI 10 were 0.04 ± 0.01%, and 0.01 ± 0.001%, respectively, after 4 h of infection. The invasion of epithelial cells by the unencapsulated strain was significantly higher than that of the serotype 2 strain P1/7 and reference strain 92-4172 after 4 h (but not after 2 h) of incubation (Fig. 5B). Our results showed that the invasion of epithelial cells may not be an essential step in the pathogenesis of infection caused by the human unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31.

Effect of S. suis serotype 31 (SS31 (43640)), reference strain 92-4172 (SS31 (92-4172)), and S. suis serotype 2 (P1/7) (SS2 (P1/7)) on A549 cell invasion after (A) 2 h or (B) 4 h. Cell invasion rate (%) is expressed as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 or ** p < 0.01 or *** (p < 0.001) indicates a significant difference between cell adhesion rate of A549 cells infected with SS31 strain 43640 compared to that of cells infected with the reference strain 92-4172 and SS2 (P1/7) strain.

Induction of apoptosis by unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31

The percentage of apoptotic cells increased when cells were infected with S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 (Fig. 6). Strain 43640 increased the percentage of apoptotic cells to 13.13 ± 6.29% and 29.03.95 ± 19.98% at MOI 1 (Fig. 6A, B) and MOI 10 (Fig. 6A, C), respectively, compared to the control (2.9 ± 1.69%). In contrast, infection with S. suis serotype 2 strain P1/7 increased the proportion of apoptotic cells to 22.9 ± 13.45% and 79.1 ± 7.58% at MOI 1 (Fig. 6A, B) and MOI 10 (Fig. 6A, C), respectively, compared to the control. The early apoptotic rate of S. suis serotype 2 strain P1/7 was significantly higher than that of strain 43640 at an MOI 10 (Fig. 6C), confirming that the human unencapsulated strain 43640 induces epithelial cell apoptosis.

Apoptotic effect in A549 cells following treatment with S. suis serotype 31 (SS31) and S. suis serotype 2 (P1/7) (SS2 (P1/7)). (A) Flow cytometric analysis of the induction of apoptosis in A549 cells following treatment with S. suis serotype 31 and S. suis serotype 2 (P1/7) for 2 h. Graph showing the percentage of apoptotic cells for the indicated concentrations at (B) MOI 1 and (C) MOI 10. Uninfected A549 cells were used as the control. *p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between the cell adhesion rate of A549 cells infected with the SS 31 strain compared to that of cells infected with the SS 2 (P1/7) strains.

Expression of apoptosis regulators by the unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31

To determine the signaling pathways that participate in S. suis serotype 31-induced apoptosis in A549 cells, proteins related to the caspase pathway were analyzed. Results of flow cytometry using annexin V/PI staining showed that infection with S. suis serotype 31 significantly increased caspase 9 expression compared to that in the control cells, although the expression of caspase 3 did not differ significantly (Fig. 7). In contrast, S. suis serotype 2 strain P1/7 increased the expression of both caspase 3 and caspase 9 although they did not differ significantly from that in uninfected cells (Fig. 7).

Changes in the expression of proteins related to apoptosis in A549 cells. A549 cells were infected with S. suis serotype 31 (SS31) and S. suis serotype 2 (P1/7) (SS2 (P1/7)). The expression of apoptosis-related molecules, caspase 3 and caspase 9, were normalized that of β-actin. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three separate experiments. *p < 0.05. The original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Virulence of the unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31 in mice model

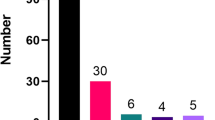

The virulence of the unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31-ST221 strain 43640 compared to that of the reference strain 92-4172 was evaluated using a C57BL/6 mouse model of infection. Seven days post-infection, severe clinical signs, such as depression, swollen eyes, weakness, and prostration, were observed in mice infected with the reference strain 92-4172 and the unencapsulated strain 43640. Only two mice in the unencapsulated strain 43640-infected group died from septicemia 24 h post-inoculation (13.33% mortality) (Fig. 8). In contrast, seven mice died from septicemia in the reference strain 92-4172 group at 24 h post-inoculation, with 46.67% mortality (Fig. 8). At 48 h post-inoculation, 13 mice died from septicemia in the reference strain 92-4172 group (86.67% mortality), whereas seven mice died after infection with strain 43640 (46.67% mortality). In general, the reference strain 92-4172 showed significantly higher mortality rates (p < 0.05) than the isolated strain (Fig. 8). This suggests that the unencapsulated strain has lower virulence than the encapsulated reference strain.

Survival (A) and blood bacterial burden at 12 h (B) and 24 h post-infection (C) of C57BL/6 mice following intraperitoneal inoculation of the S. suis serotype 31 reference strain 92-4172 (black) and the S. suis serotype 31 unencapsulated strain 43640 (purple). Data represent survival curves (A) (n = 15) or geometric mean (B, C) (n = number of surviving mice at each time point). * p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference between survival or blood bacterial burden of mice infected with unencapsulated strain compared to those of mice infected with the reference strain.

Live bacterial loads were recovered from blood at 12 h and 24 h. Bacterial counts from the blood of the reference strain 92-4172- and the unencapsulated strain 43640-infected mice were 4.09 × 105 CFU/mL and 2.51 × 104 CFU/mL, respectively, at 12 h (p < 0.05) and 5.13 × 104 CFU/mL and 2.13 × 104 CFU/mL, respectively, at 24 h (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8A, B). The bacterial counts in the blood of mice infected with the unencapsulated strain 43640 were significantly lower at 12 h and 24 h post-infection (p < 0.05) than in those infected with the reference strain 92-4172.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated the in vitro interactions with host cells and in vivo virulence of the human unencapsulated serotype 31-ST221 strain 43640. A previous report has shown that this strain contained 13 virulence-associated genes (VAG: IgA protease, arcA, luxS, glnA, apuA, eno, sspA, srtA, covR, zur, fur, adcR, and feoB) that are usually found in serotype 2 strains8. This strain belongs to ST221 of CC221/234, which is an emerging clone associated with human infection in Thailand31. A previous study has revealed that CC221/234 strains contained 56 of the 80 VAGs present in virulent serotype 2, suggesting that it is potentially virulent32.

Although S. suis adheres to different epithelial cell lines, including A549, human cervical carcinoma (HeLa), kidney of a normal adult dog (MDCK), kidney of an adult pig (PK (15)), and kidney of a normal juvenile pig (LLC-PK1), HEp-2 epithelial cell invasion may depend on strain genotypes/phenotypes, uptake mechanisms, persistence in acidified phagolysosomal compartments, or environmental signals21,33,34. Benga et al. (2004) showed that some strains persisted in HEp-2 cells for at least 24 h, whereas others were significantly eliminated33. Intracellular survival may be a key factor determining the invasion mechanisms. The mechanism used by S. suis serotype 31 in host-cell interactions may be associated with adhesion activity, which is an essential step in bacterial pathogenesis or infection1. The adhesion rate of S. suis serotype 31 increased after infection at MOI 10 compared to that at MOI 1, although it was significantly lower than that of strain P1/7. This was unexpected as it has been reported that the absence of capsular polysaccharides increases the surface exposure of adhesins35. Interestingly, the invasion capacity of serotype 31 was significantly higher than that of the serotype 2 strain P1/7, indicating that higher adhesion is not necessarily followed by increased bacterial internalization36. As described previously, unencapsulated strains normally exhibit higher invasion capacities33. We can hypothesize that for the serotype 31 strain, the absence of a capsule increases the surface exposure to invasins but not adhesins. However, this finding remains to be confirmed. A previous study has reported that 106 putative virulence-associated genes and 58 genes are present in the S. suis serotype 31 human strain12. The 1910HK/RR two-component system is essential for adhesion and invasion of S. suis serotype 237. The IgA1 protease is a surface-protective antigen that helps bacteria counter the mucosal immune system38. The surface-associated protein, SspA, is a conserved virulence factor in S. suis serotype 2 and is involved in the pathogenesis of S. suis39. d-Alanylation of lipoteichoic acid dltA contributes to the virulence of S. suis by allowing it to escape immune clearance mechanisms and move across host barriers40. Additionally, luxS plays a vital role in biofilm formation of S. suis41. All virulence-associated genes were identified in S. suis strain 4364012.

Previous studies have shown that unencapsulated strains form biofilms more efficiently than encapsulated strains33,42,43. Both strains in the current study showed strong biofilm formation. The capacity of S. suis to produce biofilms is associated with greater resistance to antibiotics and longer periods of antibiotic therapy, persistent colonization, exchange of genetic materials, and tolerance to host immune system clearance, and it may contribute to the establishment of infections, such as meningitis and endocarditis44,45.

The cytotoxicity of serotype 31 was significantly lower than that of the highly virulent serotype 2 strain P1/7, mostly during the early incubation period. The exact virulence factors of serotype 31 that are involved in cytotoxicity are not known because this strain lacks the suilysin-coding gene8. Suilysin is an important factor for cell cytotoxicity1. A study in Thailand demonstrated that suilysin-negative strains were as cytotoxic to peripheral white blood cells as a suilysin-positive strain46. However, whether other unidentified factors contribute to the cytotoxicity remains unknown.

Apoptosis is an important pathogenic mechanism that helps to eliminate key immune cells or evade host defenses that limit infection47,48. Several underlying pathogenic mechanisms can induce apoptosis in host cells. S. suis-induced caspase 3 and caspase 9 activity.

promotes apoptosis of porcine choroid plexus epithelial cell29. Consistent with the results of the above study, S. suis serotype 31 induced apoptosis in A549 cells, which may be associated with caspase 9 activation. This may indicate that the cytotoxic activity in host epithelial cells via apoptotic activation may be an important mechanism used by the unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31 to damage cells, similar to that observed with the virulent serotype 2 strain. A previous study showed that the expression of S. suis serotype 2 enolase induced apoptosis of porcine brain microvascular endothelial cells by promoting the expression of host heat shock protein family D member 1 and activation of caspase 8, followed by that of caspase 3, which increased blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability and promoted bacterial penetration through the BBB22.

An animal model revealed that our unencapsulated serotype 31 strain 43640 generally presented an intermediate virulence capacity in a mouse model of infection, with 13% mortality within 24 h. The survival rate of mice infected with strain 43640 was approximately 53% at 7 days post-infection. This result is similar to that reported in a previous study in which an encapsulated serotype 31 strain 11LB5 (ST421) isolated from a diseased pig also presented an intermediate level of virulence in CD1 mice24. In this study, 91% mice showed clinical signs and high levels of bacteremia (4.09 × 105 CFU/mL), and 37.5% of the animals died after four days of infection with strain 11LB524. Our study also showed that the blood bacterial burden in mice infected with the unencapsulated strain was significantly lower than that of the reference strain. These results confirmed that the presence of capsular polysaccharides increases resistance to bacterial killing via phagocytic cells1. A previous study has shown that 34% of the S. suis isolates from porcine endocarditis were unencapsulated, indicating that the loss of capsular production is beneficial for adherence to porcine or human platelets in infective endocarditis42.

A previous study has suggested that serotypes 21 and 31 (ST750 and ST821, respectively) may be associated with the commensal pathotype, which indicates avirulence or very low virulence49. However, the current study showed that serotype 31-ST221 (CC221/234) recovered from a human patient harbored virulence potential based on in vitro and in vivo models. Based on the schematic systems of pathotyping and virulence-associated gene profiles, CC221/234 was hypothesized to belong to the virulence group or intermediate/weak virulence group, as described elsewhere32. The findings of the current study support those of a previous study32 that showed that the unencapsulated serotype 31 strain 43640 in CC221/234 is a pathogenic pathotype with intermediate virulence.

Conclusions

The current study revealed that the human unencapsulated S. suis serotype 31 strain 43640 was cytotoxic for an epithelial cell line. Notably, this strain displayed strong biofilm formation after 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h. Strain 43640 induced apoptosis of epithelial cells via a caspase 9-dependent pathway. Although the strain adhered effectively to epithelial cells, it did not exhibit invasive capabilities. In addition, this strain was found to be pathogenic in a mouse infection model. Therefore, S. suis serotype 31 is a potential threat to public health and awareness regarding its surveillance and prevention should be increased.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Segura, M., Calzas, C., Grenier, D. & Gottschalk, M. Initial steps of the pathogenesis of the infection caused by Streptococcus suis: fighting against nonspecific defenses. FEBS Lett. 590, 3772–3799 (2016).

Kerdsin, A., Segura, M., Fittipaldi, N. & Gottschalk, M. Sociocultural factors influencing human Streptococcus suis disease in Southeast Asia. Foods 11, 1190 (2022).

Rayanakorn, A., Ademi, Z., Liew, D. & Lee, L. H. Burden of disease and productivity impact of Streptococcus suis infection in Thailand. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 15, e0008985 (2021).

Goyette-Desjardins, G., Auger, J., Xu, J., Segura, M. & Gottschalk, M. Streptococcus suis, an important pig pathogen and emerging zoonotic agent-an update on the worldwide distribution based on serotyping and sequence typing. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 3, e45 (2014).

Kerdsin, A. et al. Clonal dissemination of human isolates of Streptococcus suis serotype 14 in Thailand. J. Med. Microbiol. 58, 1508–1513 (2009).

Kerdsin, A. et al. Emergence of Streptococcus suis serotype 9 infection in humans. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 50, 545–546 (2017).

Kerdsin, A. et al. Genotypic diversity of Streptococcus suis strains isolated from humans in Thailand. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 917–925 (2018).

Hatrongjit, R. et al. First human case report of sepsis due to infection with Streptococcus suis serotype 31 in Thailand. BMC Infect. Dis. 15, 392 (2015).

Hatrongjit, R. et al. Genomic characterization and virulence of Streptococcus suis serotype 4 clonal complex 94 recovered from human and swine samples. PLoS One. 18, e0288840 (2023).

Kerdsin, A. et al. Sepsis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in Thailand. Lancet 378, 960 (2011).

Kerdsin, A. et al. Fatal septic meningitis in child caused by Streptococcus suis serotype 24. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 22, 1519 (2016).

Boueroy, P. et al. Genomic characterization of Streptococcus suis serotype 31 isolated from one human and 17 clinically asymptomatic pigs in Thailand. Vet. Microbiol. 304, 110482 (2025).

Meekhanon, N. et al. Potentially hazardous Streptococcus suis strains latent in asymptomatic pigs in a major swine production area of Thailand. J. Med. Microbiol. 66, 662–669 (2017).

Kerdsin, A. et al. Genotypic comparison between Streptococcus suis isolated from pigs and humans in Thailand. Pathogens 9, 50 (2020).

Padungtod, P. et al. Incidence and presence of virulence factors of Streptococcus suis infection in slaughtered pigs from Chiang Mai, Thailand. Southeast. Asian J. Trop. Med. Public. Health. 41, 1454–1461 (2010).

Wongsawan, K., Gottschalk, M. & Tharavichitkul, P. Serotype- and virulence- associated gene profile of Streptococcus suis isolates from pig carcasses in Chiang Mai Province, Northern Thailand. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 77, 233–236 (2015).

Soares, T. C. et al. Streptococcus suis in employees and the environment of swine slaughterhouses in São Paulo, brazil: occurrence, risk factors, serotype distribution, and antimicrobial susceptibility. Can. J. Vet. Res. 79, 279–284 (2015).

Nedbalcova, K. et al. Resistance of Streptococcus suis isolates from the Czech Republic during 2018–2022. Antibiotics 11, 1214 (2022).

Gottschalk, M. et al. Characterization of Streptococcus suis isolates recovered between 2008 and 2011 from diseased pigs in Quebec, Canada. Vet. Microbiol. 162, 819–825 (2013).

Werinder, A. et al. Streptococcus suis in Swedish grower pigs: occurrence, serotypes, and antimicrobial susceptibility. Acta Vet. Scand. 62, 36 (2020).

Lalonde, M., Segura, M., Lacouture, S. & Gottschalk, M. Interactions between Streptococcus suis serotype 2 and different epithelial cell lines. Microbiology 146, 1913–1921 (2000).

Liu, H. et al. Streptococcus suis serotype 2 enolase interaction with host brain microvascular endothelial cells and RPSA-induced apoptosis lead to loss of BBB integrity. Vet. Res. 52, 1–15 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Streptococcus suis serotype 2 infection induces splenomegaly with splenocyte apoptosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e03210–e03222 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Strain Characterization of Streptococcus suis Serotypes 28 and 31, Which Harbor the Resistance Genes optrA and ant(6)-Ia. Pathogens 10, 213 (2021).

Tajbakhsh, E., Ahmadi, P., Abedpour-Dehkordi, E., Arbab-Soleimani, N. & Khamesipour, F. Biofilm formation, antimicrobial susceptibility, serogroups and virulence genes of uropathogenic E. coli isolated from clinical samples in Iran. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 5, 1–8 (2016).

Dong, C. L. et al. New characterization of multi-drug resistance of Streptococcus suis and biofilm formation from swine in Heilongjiang Province of China. Antibiotics 12, 132 (2023).

Boueroy, P. et al. Genomic analysis and virulence of human Streptococcus suis serotype 14. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 44, 639–651 (2025).

Phetburom, N. et al. Antimicrobial activity of Chromolaena odorata crude extracts against Streptococcus suis. Microb. Pathog. 206, 107799 (2025).

Tenenbaum, T. et al. Cell death, caspase activation, and HMGB1 release of Porcine choroid plexus epithelial cells during Streptococcus suis infection in vitro. Brain Res. 1100, 1–12 (2006).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Kerdsin, A. Human Streptococcus suis infections in thailand: epidemiology, clinical features, genotypes, and susceptibility. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 7, 359 (2022).

Kerdsin, A. et al. Genomic characterization of Streptococcus suis serotype 24 clonal complex 221/234 from human patients. Front. Microbiol. 12, 812436 (2021).

Benga, L., Goethe, R., Rohde, M. & Valentin-Weigand, P. Non‐encapsulated strains reveal novel insights in invasion and survival of Streptococcus suis in epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 6, 867–881 (2004).

Norton, P., Rolph, C., Ward, P., Bentley, R. & Leigh, J. Epithelial invasion and cell Lysis by virulent strains of Streptococcus suis is enhanced by the presence of Suilysin. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 26, 25–35 (1999).

Fittipaldi, N., Segura, M., Grenier, D. & Gottschalk, M. Virulence factors involved in the pathogenesis of the infection caused by the swine pathogen and zoonotic agent Streptococcus suis. Future Microbiol. 7, 259–279 (2012).

Auger, J. P. et al. Interactions of Streptococcus suis serotype 9 with host cells and role of the capsular polysaccharide: comparison with serotypes 2 and 14. PLoS One. 14, e0223864 (2019).

Yuan, F. et al. The 1910HK/RR two-component system is essential for the virulence of Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Microb. Pathog. 104, 137–145 (2017).

Zhang, A. et al. Identification and characterization of IgA1 protease from Streptococcus suis. Vet. Microbiol. 140, 171–175 (2010).

Hu, Q. et al. Identification of a cell wall-associated subtilisin-like Serine protease involved in the pathogenesis of Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Microb. Pathog. 48, 103–109 (2010).

Fittipaldi, N. et al. D-alanylation of Lipoteichoic acid contributes to the virulence of Streptococcus suis. Infect. Immun. 76, 3587–3594 (2008).

Gao, S. et al. Effects of AI-2 quorum sensing related LuxS gene on Streptococcus suis formatting monosaccharide metabolism-dependent biofilm. Arch. Microbiol. 206, 407 (2024).

Lakkitjaroen, N. et al. Loss of capsule among Streptococcus suis isolates from Porcine endocarditis and its biological significance. J. Med. Microbiol. 60, 1669–1676 (2011).

Lakkitjaroen, N. et al. Capsule loss or death: the position of mutations among capsule genes sways the destiny of Streptococcus suis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 354, 46–54 (2014).

Grenier, D., Grignon, L. & Gottschalk, M. Characterisation of biofilm formation by a Streptococcus suis meningitis isolate. Vet. J. 179, 292–295 (2009).

Donlan, R. M. & Costerton, J. W. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15, 167–193 (2002).

Thananchai, H. & Duangsonk, K. Cytotoxic effect of Streptococcus suis on peripheral white blood cells. BSCM 55, 55–56 (2016).

Fink, S. L. & Cookson, B. T. Apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necrosis: mechanistic description of dead and dying eukaryotic cells. Infect. Immun. 73, 1907–1916 (2005).

Weinrauch, Y. & Zychlinsky, A. The induction of apoptosis by bacterial pathogens. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53, 155–187 (1999).

Estrada, A. A. et al. Serotype and genotype (multilocus sequence type) of Streptococcus suis isolates from the united States serve as predictors of pathotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 57, e00377–e00319 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Surasak Saokaew, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Phayao, for assistance with the statistical analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research, and Innovation (OPS MHESI), Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) (Grant No. RGNS 65 − 035), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (Grant No. 2022–03730), and Kasetsart University, Faculty of Public Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.B. conceptualization, performed experiment, designed the study, formal analysis, and wrote the original manuscript; N. P., and S. P. performed the experiments; P.C., R.H., A. K., methodology, investigation, formal analysis, conceptualization; S.C, M.S, and M.G performed the validation and data analysis; all authors have read, agreed, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boueroy, P., Phetburom, N., Chareonsudjai, S. et al. Pathogenic characteristics of an unencapsulated Streptococcus suis serotype 31 strain isolated from a patient in Thailand. Sci Rep 15, 37788 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21437-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21437-0