Abstract

This study aimed to explore the role of macrophage polarization and TLR4/NF-κB pathway in promoting browning of white adipose tissue through different hypoxic exercises. (1) Fifty obese female rats were selected after 16 weeks of high-fat diet feeding and randomly divided into normoxic sedentary (NC), normoxic exercise (NE), hypoxic sedentary (HC), Living-High Training-High (HH), and Living-Low Training-High (LH) groups. Four weeks of hypoxic and exercise interventions were conducted to investigate changes in the expression of the TLR4/NF-κB pathway and inflammatory factors in obese rat adipose tissue and the expression of genes and proteins related to adipose tissue browning. (2) After the 4-week intervention, adipose tissue macrophages (ATM) were isolated from HH and LH groups, activated with NF-κB activator, and co-cultured with adipocyte-induced adipose-derived stem cells to explore the role of the TLR4/NF-κB pathway in promoting browning of white adipose tissue by inducing changes in macrophage polarization through different hypoxic exercise. (1) After 4 weeks of different hypoxic interventions, the proportion of M1 macrophages decreased (p < 0.01), and HH intervention increased the proportion of M2 macrophages (p < 0.05). The protein expression levels of TLR4, NF-κB, p-NF-κB, and MyD88 in ATM of the HH and LH groups were significantly lower than those of the NC group (p < 0.01). Four weeks of LH intervention significantly upregulated the protein expression levels of CIDEA, C/EBP-β, PPAR-γ, PGC-1α, PRDM-16, and UCP-1 in rat adipose tissue (p < 0.01). (2) NF-κB activator intervention for 24 h significantly upregulated the protein expression levels of TLR4, p-NF-κB, and MyD88 in adipose tissue of HH and LH group rats (p < 0.01). NF-κB activator intervention for 24 h downregulated the protein expression levels of CIDEA, C/EBP-β, PPAR-γ, PGC-1α, PRDM-16, and UCP-1 in co-cultured adipocytes for 48 h in ATM of the LH group rats (p < 0.05). Four weeks of HH and LH interventions could reduce M1 polarization of ATM, downregulate the expression levels of the TLR4-NF-κB pathway in ATM, and promote browning of white adipose tissue. The TLR4-NF-κB pathway plays a more critical role in promoting the browning of white adipose tissue by regulating macrophage polarization in LH intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity has emerged as a dire concern for public health. In the past two decades, the global prevalence of obesity in adults has increased by approximately 1.5 times, while the rate has doubled in children1. The obese or overweight population in China exceeds 50%, and the proportion of obese women is higher than that of obese men2,3. Thus, the effective prevention and reduction of obesity have garnered significant attention.

Obesity is caused by an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure, resulting in lipid accumulation. Prolonged and excessive nutrient intake can expand adipose tissue, alter phenotype, and disrupt hormonal signaling. Excess fat accumulation triggers an inflammatory response characterized by a pro-inflammatory phenotype and chronic low-grade inflammation4,5,6,7.

Adipose tissue is composed of adipocytes and the stromal vascular fraction (SVF). Adipose tissue macrophages (ATM) are the most active cells in the SVF and play pivotal roles in inflammation and insulin resistance8,9.

Inflammatory processes within adipose tissue can alter macrophage numbers and polarization. During obesity, macrophages increase in adipose tissue, the TLR4/NF-κB pathway upregulates macrophages, and significant changes occur in the macrophage phenotype5,10,11,12,13,14. Kawanishi et al.15 demonstrated that 16 weeks of treadmill exercise reduced TLR4 mRNA expression levels in the adipose tissue of high-fat diet-induced obese mice, indicating that TLR4 may serve as a pathway through which exercise alleviates obesity-induced adipose tissue inflammation. The polarization of macrophages influences the browning of white adipose tissue, and physical exercise modulates macrophage polarization and promotes browning16,17,18,19,20,21.

Kawanishi et al.15 reported that 16 weeks of treadmill exercise significantly reduced CD11c mRNA expression, a marker specific to M1 macrophages, and increased CD163 mRNA expression, a marker for M2 macrophages, in the adipose tissue of obese mice. Additionally, Lira et al.22 found that 8 weeks of moderate-intensity treadmill exercise reduced TNF-α expression.

Therefore, this study specifically investigates two distinct hypoxic training strategies—Living High Training High (HH) and Living Low Training High (LH)—to determine their differential roles in modulating macrophage polarization and white adipose tissue browning. Unlike general hypoxic exposure, the LH model mimics real-world elite athlete training practices and may induce unique metabolic and inflammatory adaptations, which have not been fully explored.

Recent evidence has also highlighted the combined effects of exercise training and nutritional or antioxidant interventions on adipose inflammation and metabolic outcomes. For instance, aerobic-resistance training combined with broccoli supplementation improved insulin resistance in males with type 2 diabetes, while intense circuit resistance training with Zataria multiflora supplementation reduced TNF-α in postmenopausal women. Similarly, high-intensity functional training supplemented with astaxanthin decreased adipokine levels in obese men, and circuit resistance training plus antioxidant supplementation modulated adipokines in postmenopausal women. These studies collectively underscore the potential synergy between exercise and metabolic modulators, supporting our hypothesis that hypoxic exercise may confer unique anti-inflammatory and browning benefits.

Hypoxic exercise can induce browning of white adipose tissue and contribute to weight loss and management23,24. Accordingly, we hypothesized that hypoxic exercise promotes the browning of white adipose tissue by modulating the ATM polarization, and the TLR4/NF-κB pathway plays a crucial role in this process.

Materials and methods

Animals and experimental design

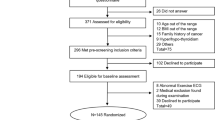

A total of 130 3-week-old female Sprague Dawley rats were obtained from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing) (SCXK (JING) 2021-0011) and maintained under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions at the Animal Experiment Laboratory of Beijing Sport University (SYXK (JING) 2021-0053). The rats were housed in cages with a 12 h light/dark cycle, a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C, and relative humidity at 60 ± 10%. After one week of standard diet feeding, the rats were randomly divided into two groups: 20 were fed a standard diet, and 110 were fed a high-fat diet ad libitum. The standard diet consisted of Growth Maintenance Pellets for laboratory animals (Beijing HuaFuKang Biological Technology Co., Ltd., 1025), while the high-fat diet comprised 45% high-fat feed (Beijing HuaFuKang Biological Technology Co., Ltd., H10045). The study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Sport University (Ethics Approval Number: 2022169 A).

After 16 weeks of feeding, 60 obese rats were selected from the high-fat diet group based on body weight and Lee’s index. The criteria for successful obesity modeling were as follows: (1) body weight exceeding 20% of the average weight of the standard diet group; (2) a significant difference in Lee’s index compared to the average value of the standard diet group.

Furthermore, 10 of 60 obese rats underwent the first sampling, and the remaining 50 were randomly divided into five groups: normoxic sedentary (NC), normoxic exercise (NE), hypoxic sedentary (HC), Living-High Training-High (HH), and Living-Low Training-High (LH) groups, with 10 rats in each group.

After 16-week feeding, the weight (g) of the 10 rats in the high-fat diet group and the 10 rats in the standard diet group were 408.40 ± 18.21 versus 302.63 ± 12.66. The total cholesterol (TC) (mmol/L) of the 10 rats in the high-fat diet group and the 10 rats in the standard diet group were 2.04 ± 0.24 versus 1.51 ± 0.30, displaying significant differences (p < 0.01).

Hypoxic intervention program

The HC group was subjected to a simulated hypoxic environment without engaging in training activities. In contrast, the HH group lived in a simulated hypoxic environment and concurrently underwent training within the same hypoxic conditions. The LH group, on the other hand, resided under normoxic conditions and only performed their training in the simulated hypoxic environment. The simulated hypoxic environment was set to replicate an oxygen concentration of 13.6%, equivalent to an altitude of 3500 m, with the hypoxic intervention period spanning four weeks.

Exercise intervention programs

After 16 weeks of high-fat diet intervention, maximal oxygen consumption tests were conducted on obese rats to determine the exercise intensity at 60–70% of maximal oxygen consumption for the NE group. Blood lactate levels were measured during exercise depending on the NE group’s intensity, and the exercise intensities for the HH and LH groups were set accordingly to match that of the NE group.

Based on the maximal oxygen consumption test, the training intensity for obese rats under normoxia was set at 20 m/min and a blood lactate level of 3.98 ± 0.48 mmol/L. The training intensity for obese rats under hypoxia was set at 16 m/min and a blood lactate level of 3.88 ± 0.67 mmol/L.

The NE, HH, and LH groups underwent a 4-week treadmill exercise intervention, performing exercises at the intensity determined by the methods described previously, with a frequency of 1 h per day, 5 days per week.

Sample collection

After the 16-week high-fat diet intervention, the first sample was collected to confirm the successful establishment of the rat obesity model. The second sample was collected 24 h following the last exercise session of the four-week intervention period.

Rats were anesthetized using 20% urethane solution at a dosage of 6 mL/kg body weight (rats in the HC and HH groups were anesthetized in a low-oxygen environment). The rats were then disinfected with 75% alcohol for 5 min and quickly transferred to a clean workstation. Under aseptic conditions, a midline incision was made at the xiphoid level (below the sternum) using a new set of scissors and forceps to access the abdominal cavity. Blood was collected from the abdominal aorta, avoiding any major blood vessels. Another pair of scissors and forceps were used to dissect the bilateral epididymis and posterior abdominal wall fat tissue, ensuring the preservation of the gonadal tissue. The fat tissue was divided into four portions. The first portion, weighing 1500 mg, was placed in pre-cooled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4 °C for flow cytometry analysis. The second portion, weighing 1000 mg, was used for Western blot and PCR sample preparation. The third portion, weighing 1000 mg, was stored as a backup. These last two portions were packaged in pre-labeled aluminum foil and stored in liquid nitrogen before transferring to a − 80 °C ultra-low temperature freezer for later use. The remaining visceral fat was placed in a complete culture medium pre-cooled at 4 °C for macrophage isolation.

Cell sorting of ATM

The macrophages were primarily isolated from the rat adipose tissue following the method of Jeb et al.25. The adipose tissue obtained from the donors was subjected to collagenase digestion at a ratio of 3 mL collagenase digestion solution per 1.2 g of adipose tissue sample. The digestion solution comprised 1 × DPBS containing 0.5% (bovine serum albumin, BSA), 10 mm CaCl2, and 4 mg/mL type II collagenase. The adipose tissue was transferred to a 50 mL conical tube, minced, and washed with 1 mL DPBS (0.5% BSA), followed by 3 mL of collagenase solution. The minced adipose tissue was incubated at 37 °C on a rotating shaker for 20 min.

Following digestion, 10 mL of DPBS (0.5% BSA) was added to the conical tube and repeatedly minced on ice. The cell suspension was filtered through a 100 μm filter and collected in a 50 mL conical tube. The filtered cell suspension was centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 3 mL ACK buffer to lyse contaminating red blood cells. Subsequently, 12 mL of FACS buffer was added, and the cell suspension was centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The cell pellet, representing the isolated adipose macrophages, was collected and resuspended in a complete culture medium. The resuspended cells were centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The cell concentration was adjusted to 1.0 × 106 cells/100 µL using PBS.

Next, 100 µL of the cell suspension was incubated with 5 µL of CD68 flow cytometry antibody at 4 °C in the dark for 30 min, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Steps 1–3 were repeated until all cells were processed. The CD68 cell ratio was determined using a BeamCyte-1026 flow cytometer (BeamDiag, China).

The sorted cells were collected and resuspended in a complete culture medium consisting of DMEM-F12 (Gibco, 2023-01) supplemented with 10% FBS (solelybio, 11011-615) and 1% antibiotics.

Isolating and inducing adipogenic differentiation of rat adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells

Eighteen-week-old rats were anesthetized using a 20% urethane solution at a dose of 6 mL/kg body weight. The rats were thoroughly disinfected by immersing them in a 75% alcohol solution for 5 min. Once disinfected, the rats were immediately transferred to a laminar flow hood. Visceral adipose tissue was excised using sterilized scissors and forceps, avoiding gonadal tissue. The adipose tissue was placed in a 6 cm culture dish containing pre-cooled PBS at 4 °C, washed thrice with PBS for 1 min each, and minced into 1 mm3-sized fat granules. The minced fat granules were transferred into a 10 mL centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min.

The upper layer of fat tissue (2 mL) was transferred to a 6 cm culture dish and digested with 5 mL of digestion solution (0.2% type I collagenase). The dish was sealed with sealing film and placed in a 37 °C constant temperature shaker at 100 rpm for 120 min, with manual agitation every 10 min. After digestion, the emulsion was transferred to a 10 mL centrifuge tube, mixed with 5 mL of complete culture medium, and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in the basic culture medium to obtain a cell suspension. The cell suspension was counted using a hemocytometer under an inverted microscope, adjusted to a cell density of approximately 5 × 105 cells/mL, and seeded into T25 culture bottles.

Adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells was induced using the OriCell Mesenchymal Stem Cell Adipogenic Differentiation Induction Kit (OriCell, RAXMD-90031). The isolated adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells were considered passage 0. When the cells reached confluence at passage 2 in mesenchymal stem cell culture medium (consisting of DMEM-F12 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics), cells were plated and allowed to reach 80% confluence. Adipogenic induction was initiated by adding Induction Medium A for three days, followed by the removal of A and the addition of Induction Medium B for one day. This cycle was repeated with medium changes every three days, alternating between Induction Mediums A and B until induction was carried out for 14 days.

NF-κB activation in macrophages co-cultured with adipogenesis-induced mesenchymal stem cells

Based on the literature, NF-κB activator 2 was chosen as the NF-κB activator for this experiment26. Reportedly, NF-κB activator 2 increases the expression and activation of NF-κB. After preliminary experiments, a concentration of 2 µM and a duration of 24 h were selected as the specific parameters for the formal experiment.

A cell co-culture system was established using Transwell chambers with a membrane pore size of 0.4 μm. Macrophages were seeded in the upper chamber. Adipogenesis-induced mesenchymal stem cells obtained after 14 days of adipogenic induction were placed in the lower chamber. The upper and lower chambers were divided into five and six groups, respectively. After co-culturing for 48 h, cells were collected for indicator detection. The experimental groups are presented in Table 1.

Body composition testing in rats

The body composition of rats was assessed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Isoflurane (VETESAY, China) was added to the small animal gas anesthesia machine, and the body composition was tested after rats were successfully anesthetized.

Polarization phenotype and TLR4/NF-κB pathway protein expression in ATM

The adipose tissue immersed in PBS at a low temperature was cut into small pieces using ophthalmic scissors, then added to 15 mL of PBS and gently grounded on a nylon mesh. The adipose tissue was filtered through a 200-mesh sieve, collected into 15 mL centrifuge tubes, and subjected to a 10-min water bath at 0 °C and centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min. The floating oil and liquid were aspirated from the upper layer, leaving only the cell precipitate. The cells were resuspended in 100 µL PBS and transferred to clean flow cytometry tubes.

To detect macrophage polarization phenotypes, 3 µL of CD68, CD86, and CD206 antibodies were added to each tube, vortexed, and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 20 min. After incubation, 2 mL of red blood cell lysis solution was added, followed by centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the cells were resuspended in 300 µL PBS buffer for flow cytometry analysis using BeamCyte-1026 (BeamDiag, China).

To determine macrophage TLR4/NF-κB pathway protein expression, 3 µL of CD68 antibody was added to each tube, vortexed, and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 20 min. Then, 0.5 mL of cell fixation solution was added and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Next, 2 mL of 1 × permeabilization solution was added, followed by centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. This process was repeated with another 2 mL of 1 × permeabilization solution. Subsequently, 5 µL of MyD88 antibody and 1 µL of NF-κB, p-NF-κB, and TLR4 antibodies were added, and the tubes were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Finally, 2 mL of 1 × permeabilization solution was added, followed by centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were resuspended in 200 µL PBS and analyzed using BeamCyte-1026 (BeamDiag, China).

RT-qPCR detection of TLR4/NF-κB pathway in macrophages and browning-related gene expression levels in adipocytes

Total RNA was extracted using the Trizol method. Reverse transcription was performed using the Invitrogen Superscript III reverse transcription kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-qPCR experiments were conducted using actin as the reference gene. The primer sequences for the reference and target genes are given in Table 2. The relative expression levels of the target genes were calculated using the ddCT method.

Western blot detection of TLR4/NF-κB pathway in macrophages and browning-related protein expression levels in adipocytes

Western blot analysis was performed to determine the protein expression levels of brown adipocyte-related markers in rat adipose tissue.

RIPA lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors were prepared at a ratio of 10:1. Total protein extraction was done following cell lysis using the lysis buffer. Protein concentration was assessed using the BCA method. Based on the protein quantification results, total protein samples were mixed with 5 × loading buffer at the appropriate volume. The mixture was denatured at 95 °C for 10 min. The samples were gently loaded into the gel wells. The electrophoresis apparatus was set to a constant voltage state of 80 V. The electrophoresis time was determined by the separation of marker bands and the molecular weight of the target protein. After transferring at 65 V for 2 h, the transferred membrane was cut according to the marker.

Primary antibody blocking was performed according to the dilution ratio specified in Table 3. After incubating overnight with the primary antibody, the reaction membrane was washed thrice in 1 × TBST for 10 min each. The secondary antibody was diluted 300 times with 1 × TBST. The washed primary antibody reaction membrane was incubated in the secondary antibody working solution for 60 min and washed thrice in 1 × TBST for 10 min each. The two components of the ECL kit were mixed in a 1:1 ratio by volume. The mixed solution was evenly spread over the surface of the PVDF membrane and allowed to react at room temperature for 4 min. The liquid on the membrane was removed and placed in a chemiluminescence imaging system for imaging.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detection of inflammation-related factor expression levels

Blood samples from rats or supernatants from co-culture systems were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min to collect the supernatant for testing. The sample concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance (OD value) at a wavelength of 450 nm using an ELISA reader, as per the instructions of the kit. The expression levels of inflammation-related factors, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-10, and ARG-1 in the supernatant of the co-culture system were detected.

Rat lipid profile testing

Strictly following the operating procedures and equipment manual, blood lipid parameters were analyzed using the Hitachi 7600 fully automated biochemical analyzer.

Data processing and statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (version 20.0). The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Confounding factors: Age and initial body weight were included as covariates in a mixed-effects model to account for variability.

Sample size and power: A post-hoc power analysis (β = 0.8, α = 0.05) confirmed that our sample size (n = 10/group) was sufficient to detect significant differences in primary endpoints (e.g., UCP-1 expression).Before analysis, all data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variance. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normal distribution of the data. One-way analysis of variance was employed for data processing. Furthermore, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and p < 0.01 was considered highly statistically significant.

Results

Food intake, body weight, and body composition of rats during the four-week intervention

As shown in Fig. 1, During the four-week intervention period, the food intake of the HH group was significantly lower than that of the NC group (p < 0.01). In the first and second weeks of the intervention, the food intake of the LH group was significantly lower than that of the NC group (p < 0.01). The food intake of the LH group gradually increased, with no significant difference compared to the NC group (p > 0.05).

As shown in Fig. 2, before the intervention and at the end of the first week of the intervention, there were no significant differences in body weight among the groups (p > 0.05). From the second week after the end of the intervention, the body weight of rats in NE and HH groups was significantly lower than that of the NC group (p < 0.01). At the end of the 4-week intervention period, the body weight of rats in NE, LH, and HH groups was significantly lower than that of the NC group (p < 0.01). The body weight of rats in the HH group was significantly lower than that of the NE group (p < 0.05).

As presented in Table 4, after the four-week intervention period, the body fat percentage of rats in the NE, LH, and HH groups was significantly lower than that of the NC group (p < 0.01). The body fat percentage of rats in the HH group was significantly lower than that of the NE group (p < 0.05).

Lipid metabolism status of rats after the 4-week intervention

As presented in Table 5, after the four-week intervention period, the levels of TC, TG, HDL-C, and LDL-C of rats in the NE group were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.01). TC, TG, and HDL-C levels of rats in the LH group were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.01). TC, TG, and HDL-C levels of rats in the HH group were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.01).

The changes in polarization phenotype of ATM and inflammatory factors in rats after the 4-week intervention

As Table 6, after the 4-week intervention, the proportion of M1 macrophages in the adipose tissue of rats in the NE group was significantly lower than that in the NC group (p < 0.01). The proportion of M1 macrophages in the adipose tissue of rats in the LH group was significantly lower than that in the NC group (p < 0.05). The proportion of M1 macrophages in the adipose tissue of rats in the HH group was significantly lower than that in the NC group (p < 0.05). The proportion of M2 macrophages in the adipose tissue of rats in the HH group was significantly higher than that in the NC group (p < 0.05).

As presented in Fig. 3, M1-polarized macrophages in the NC group concentrated in the middle of adipocytes, forming a crown-like structure. Four weeks of HH intervention increased the proportion of M2-type macrophages in the field of view and reduced the proportion of M1-type macrophages.

As Table 7, after the 4-week intervention, the levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in the NE group rats were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.01, p < 0.05), while the levels of IL-10 and ARG-1 were significantly higher than those in the NC group (p < 0.01). In the LH group, TNF-α and IL-6 levels in rats were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.01), while the IL-10 and ARG-1 levels were significantly higher than those in the NC group (p < 0.01). Similarly, in the HH group, TNF-α and IL-6 levels in rats were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.01), while IL-10 and ARG-1 levels were significantly higher than those in the NC group (p < 0.01). In the HH group, TNF-α and IL-6 levels were significantly lower than those in the NE group (p < 0.01), while ARG-1 level was significantly higher than that in the NE group (p < 0.01).

The gene and protein expression levels of the TLR4/NF-ΚB pathway in rat adipose tissue after the 4-week intervention.

As depicted in Fig. 4, after a four-week intervention, the expression levels of TLR4 and NF-κB genes in the adipose tissue of rats in the NE group were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.05). In the HC group, the expression levels of TLR4 and MyD88 genes were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.05). In the LH group, the expression levels of TLR4 and MyD88 genes were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.01). In the HH group, the expression levels of TLR4, NF-κB, and MyD88 genes were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.01). The expression level of the TLR4 gene in the HH group was significantly lower than that in the NE group (p < 0.05).

As illustrated in Fig. 5, flow cytometry analysis revealed that after a 4-week intervention, the protein expression levels of TLR4, NF-κB, p-NF-κB, and MyD88 in the adipose tissue of rats in the NE group were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.01). In the HC group, the protein expression levels of TLR4, NF-κB, p-NF-κB, and MyD88 were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.01). In the LH group, the protein expression levels of TLR4, NF-κB, p-NF-κB, and MyD88 were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.01). In the HH group, the protein expression levels of TLR4, NF-κB, p-NF-κB, and MyD88 were significantly lower than those in the NC group (p < 0.01). The protein expression levels of TLR4 and MyD88 in the HH group were significantly lower than those in the NE group (p < 0.05).

The gene and protein expression levels of the browning-related in rat adipose tissue after the 4-week intervention

As depicted in Fig. 6, after 4 weeks of normoxia exercise intervention, the gene expression levels of Cidea, Cebp-Β, Ppar-γ, Pgc-1α, and Prdm-16 in the adipose tissue of rats were significantly upregulated (p < 0.01). After four weeks of hypoxic intervention, the gene expression levels of Ppar-γ and Prdm-16 in the adipose tissue of rats were significantly upregulated (p < 0.01). After 4 weeks of LH intervention, the gene expression levels of Cidea, Cebp-Β, Ppar-γ, Pgc-1α, and Prdm-16 in the adipose tissue of rats were significantly upregulated (p < 0.01). After 4 weeks of HH intervention, the protein expression levels of Cidea, Cebp-Β, Ppar-γ, Pgc-1α, and Prdm-16 in the adipose tissue of rats were significantly upregulated (p < 0.01). The gene expression level of Pgc-1α in the LH group was significantly higher than that in the NE group (p < 0.01). The gene expression levels of Ppar-γ ,Pgc-1α, and Prdm-16 in the HH group were significantly higher than those in the NE group (p < 0.05). The gene expression level of Ucp-1 was undetected in the adipose tissue of any group.

Interestingly, Ucp-1 mRNA was undetectable in all groups, while UCP-1 protein was clearly upregulated, suggesting post-transcriptional or post-translational regulatory mechanisms.

As shown in Figs. 7 and 8, after four weeks of normoxia exercise intervention, the protein expression levels of CIDEA, CEBP-β, PPAR-γ, PGC-1α, PRDM-16, and UCP-1 in the adipose tissue of rats were significantly upregulated (p < 0.01). After 4 weeks of hypoxic intervention, the protein expression levels of CIDEA, PPAR-γ, and PRDM-16 in the adipose tissue of rats were significantly upregulated (p < 0.01). After 4 weeks of LH intervention, the protein expression levels of CIDEA, CEBP-β, PPAR-γ, PGC-1α, PRDM-16, and UCP-1 in the adipose tissue of rats were significantly upregulated (p < 0.01). After 4 weeks of HH intervention, the protein expression levels of CIDEA, CEBP-β, PPAR-γ, PGC-1α, PRDM-16, and UCP-1 in the adipose tissue of rats were significantly upregulated (p < 0.01). The protein expression levels of CEBP-β and UCP-1 in the LH group were significantly higher than those in the NE group (p < 0.01). The protein expression levels of CEBP-β and UCP-1 in the HH group were significantly higher than those in the NE group (p < 0.05).

The effect of NF-κB activator on macrophage phenotype and inflammatory factors

As demonstrated in Table 8, NF-κB activation decreased the proportion of M2 macrophages in the adipose tissue of rats in HH and LH groups and increased the proportion of M1 macrophages (p < 0.01).

NF-κB activation upregulated TNF-α and IL-6 (p < 0.05, p < 0.01) and downregulated IL-10 and ARG-1 (p < 0.01) in primary macrophages in the adipose tissue of rats in the HH group. NF-κB activation upregulated TNF-α and IL-6 (p < 0.01) and downregulated IL-10 and ARG-1 (p < 0.01) in primary macrophages in the adipose tissue of LH group rats.(Table 9).

The effect of NF-κB activator on gene and protein expression in the TLR4/NF-κB pathway of macrophages

As shown in Fig. 9, after 24 h of NF-κB activator intervention, the gene expression levels of TLR4, NF-ΚB, and Myd88 in the HH group rats were significantly upregulated (p < 0.01). The gene expression levels of TLR4, NF-ΚB, and Myd88 in LH group rats were significantly upregulated (p < 0.01, p < 0.01, p < 0.05).

As shown in Figs. 10 and 11, after 24 h of NF-κB activator intervention, the protein expression levels of TLR4, p-NF-κB, and MyD88 in the HH group were significantly upregulated (p < 0.01). Similarly, the protein expression levels of TLR4, p-NF-κB, and MyD88 in the LH group were significantly upregulated (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.05).

The effect of NF-κB activator on the gene and protein expression of brown adipogenesis in co-cultured adipocytes

As presented in Fig. 12, after 24 h of NF-κB activator intervention in macrophages from adipose tissue of HH group rats, the gene expression of PPAR-γ and Prdm-16 in co-cultured adipocytes was downregulated after 48 h (p < 0.05). After intervention in macrophages from adipose tissue of LH group rats for 24 h, the gene expression of Cidea, PPAR-γ, Prdm-16, and Ucp-1 in co-cultured adipocytes was downregulated after 48 h (p < 0.01, p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.01).

As shown in Figs. 13 and 14, after 24 h of NF-κB activator intervention in macrophages from adipose tissue of HH group rats, the protein expression of CIDEA, CEBP-β, PGC-1α, and PRDM-16 in co-cultured adipocytes was downregulated after 48 h (p < 0.05). After intervention in macrophages from adipose tissue of LH group rats for 24 h, the protein expression of CIDEA, CEBP-β, PPAR-γ, PGC-1α, PRDM-16, and UCP-1 in co-cultured adipocytes was downregulated after 48 h (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Exposure to hypoxic conditions has been recognized for its potential to induce weight loss, with the magnitude and velocity of weight reduction being contingent upon the duration and intensity of hypoxic exposure. Prolonged residence in high-altitude hypoxic environments has emerged as an innovative strategy for weight reduction. Hypoxic training has been shown to decrease body weight and adiposity while concurrently enhancing lipid metabolism, offering both efficacy and time-efficient benefits27,28. A comparative study involving two cohorts of 10 overweight individuals, each with a BMI exceeding 27, demonstrated that aerobic exercise at 60% of their maximum heart rate, performed thrice weekly for 90 min per session over a period of eight weeks, resulted in greater weight loss under normobaric hypoxic conditions (15% oxygen) compared to normoxic conditions (21% oxygen), with a significant difference of –1.14 kg versus − 0.03 kg, respectively29.

Acute exposure to hypoxic environments could suppress appetite and energy intake30. Research on climbers ascending Mount Everest has indicated a reduction in energy intake and skinfold thickness, with increasing altitude leading to a gradual decline in the concentration of growth hormone-releasing peptide, thereby diminishing appetite31,32,33. Our study corroborated these findings, demonstrating a significant decrease in food intake among rats residing in hypoxic conditions during the initial two weeks of intervention34. However, as the intervention period extends, food intake incrementally returns to baseline levels as the rats adapt to the hypoxic environment.

Considering the limitations of high-altitude training in terms of geographical location and altitude-related responses, new concepts and training modalities such as LH have been proposed in current sports practice to mitigate the potential adverse effects of prolonged or acute hypoxia exposure33,35. Our study demonstrated that a four-week intervention of LH exercise yielded positive effects on weight loss and reduced body fat36.

Effects of different interventions on atms

Furthermore, immune profiling in the NC group indicated a pro-inflammatory state, characterized by high concentrations of TNF-α (243.13 ± 23.57 pg/mL) and IL-6 (129.88 ± 12.43 pg/mL), and low levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 (18.94 ± 4.45 pg/mL) and ARG-1 (23.67 ± 2.44 ng/mL). Flow cytometry analysis also confirmed a predominant M1 macrophage polarization (28.53% ± 8.60%) with minimal M2 presence (5.71% ± 1.98%), reinforcing the presence of unresolved inflammation in the adipose tissue microenvironment.

Acute exposure to high altitudes modulates immune-related parameters; even brief exposures to hypoxia induce significant changes in neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, primarily characterized by reduced cellularity and proliferation. Acute hypoxia is also known to augment natural killer cell counts and activity. Studies on both rodents and humans have demonstrated that hypoxia triggers inflammatory responses, including increased NF-κB expression in the lungs, heightened oxidative stress, and significant elevations in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α30,37. However, our findings indicated that despite a four-week hypoxic intervention leading to reduced rat weight, there was no significant reduction in the proportion of M1 macrophages or in the levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in the bloodstream. High-altitude hypoxia (HH) intervention increased the proportion of M2 macrophages and the secretion of ARG-1, suggesting a more pronounced anti-inflammatory effect compared to normoxic training.

Effects of different interventions on TLR4/NF-κB pathway in atms

Our study demonstrated that both HH and LH interventions downregulated the expression levels of the TLR4/NF-κB pathway in macrophages. Contrary to the increased NF-κB expression under hypoxia, our analysis of post-exercise intervention changes in rat weight and body fat showed improvements in adipose tissue inflammation, leading to reduced obesity-related inflammation, primarily through decreased energy intake and increased energy expenditure. Upon activation, the TLR4/NF-κB signaling cascade leads to the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB, allowing NF-κB p65 subunit to translocate into the nucleus, where it promotes transcription of pro-inflammatory genes. This promotes M1 polarization of macrophages and suppresses the thermogenic program in adipocytes by downregulating key browning regulators such as PRDM16 and PGC-1α.

Effects of different interventions on brown adipogenesis

Exercise is known to promote the browning of subcutaneous adipose tissue, with the efficacy of this process being influenced by factors such as exercise duration. Aerobic exercise has been found to be more effective than resistance exercise in facilitating the browning process of subcutaneous adipose tissue in obese rats. Our study indicated that HH and LH interventions were superior to normoxic exercise in alleviating adipose inflammation associated with obesity and in promoting UCP-1 expression. Furthermore, the results revealed that hypoxic training not only reduces weight and body fat but also mitigates the inflammatory effects of obesity. Additionally, it may promote M2 polarization, leading to the browning of white adipose tissue and improving metabolism.

The discrepancy between undetectable Ucp-1 mRNA and robust UCP-1 protein induction highlights the possibility of post-transcriptional regulation, such as enhanced mRNA stability, translational efficiency, or reduced protein degradation. To further validate these findings, immunohistochemical staining of adipose sections for UCP-1 and multilocular adipocytes should be incorporated in future work, providing spatial evidence for browning in line with current methodological recommendations.Although the mRNA expression of browning markers such as UCP-1 was robustly demonstrated via qRT-PCR, additional validation using immunohistochemical staining for UCP-1 protein in adipose tissue would strengthen these findings. Future studies may incorporate single-cell RNA sequencing to resolve cell-specific transcriptional dynamics during the browning process.

In the in vivo part of this study, HH and LH interventions reduced weight and body fat, downregulated the TLR4/NF-κB pathway, and promoted white adipose browning. Therefore, the TLR4/NF-κB pathway may play a similar role in promoting white adipose browning under both training modalities. We explored the role of macrophage TLR4/NF-κB pathway in inducing white adipose browning under different hypoxic training regimens by isolating primary cells post-exercise to investigate the molecular mechanisms.

NF-κB serves as a central mediator of pro-inflammatory gene induction, functioning in both innate and adaptive immune cells38,39,40. The pro-inflammatory role of NF-κB in macrophages has been extensively studied; upon activation, macrophages rapidly activate and secrete substantial amounts of cytokines and chemokines. Moderate exercise has been shown to reduce NF-κB protein expression and activity in adipose tissue, thereby decreasing the expression and release of inflammatory factors and alleviating adipose tissue inflammation41. This anti-inflammatory effect may be significant for the prevention and improvement of metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes. Exercise may also modulate NF-κB activity by regulating other signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms in adipose tissue. Exercise may enhance insulin sensitivity and energy metabolism in adipose tissue, changes that may regulate NF-κB activity by affecting upstream signaling molecules42.

This study demonstrated that activation of the TLR4/NF-κB pathway upregulated M1 pro-inflammatory polarization, increased the secretion of inflammatory factors, and reduced the secretion of anti-inflammatory factors in primary isolated cells. The phenotypic transformation of macrophages affected the changes in brown adipogenesis-related indicators in co-cultured adipocytes, with NF-κB activation leading to downregulation of brown adipogenesis-related genes and proteins; the LH group displayed a more pronounced UCP-1 downregulation.

This study revealed that HH reduced the proportion of M1 macrophages in obese rat adipose tissue and upregulated the proportion of M2 macrophages. Combining the results from the in vitro part, we concluded that HH and LH interventions promoted white adipose browning by reducing the proportion of M1 macrophages. Moreover, HH may regulate white adipose browning by increasing the proportion of M2 macrophages and their associated secretory factors.

M2 macrophages are essential for tissue repair and homeostasis. M2 macrophages polarize and activate in adipose tissue thermogenesis through CXCL14 and meteorin-like protein43,44. During thermogenic activation, CXCL14 released from brown adipocytes recruits M2 macrophages, indicating a positive interaction between thermogenic adipocytes and M2 macrophages during adaptive thermogenesis.

However, the mechanisms by which M2 macrophages induce thermogenic responses are undefined45,46. Nguyen et al.47 first demonstrated that M2 macrophages expressing tyrosine hydroxylase can release norepinephrine via IL-4 signaling in response to cold stress, thereby activating thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. Follow-up studies from the same group revealed that catecholamine-producing M2 macrophages also mediate thermogenesis in beige adipocytes, providing a comprehensive mechanism for this process46. In the subcutaneous white adipose tissue of mice, IL-5, secreted by IL-33-stimulated type 2 innate lymphoid cells, recruits and activates eosinophils, which, in turn, activate M2 macrophages through IL-4 secretion. Additionally, type 2 cytokines IL-13 and IL-4, produced by type 2 innate lymphoid cells and eosinophils, can drive beige differentiation of PDGFRα + progenitor cells via IL-4 receptor α signaling. Recent findings suggest a novel mechanism in which M2-like macrophages in adipose tissue secrete Slit3 protein, which binds to the Robo1 receptor on sympathetic nerves, activating the Ca2+/CaMKII pathway to promote norepinephrine release, thereby enhancing lipolysis and thermogenesis in adipocytes48.

The activation of the TLR4-NF-κB pathway in primary ATM following exercise intervention was associated with a reduction in browning levels. This finding suggests that the TLR4-NF-κB pathway is a critical mechanism through which HH and LH interventions promote the browning of white adipose tissue by modulating macrophage polarization. Notably, the TLR4-NF-κB pathway plays a more prominent role in enhancing white adipose browning through macrophage polarization under LH intervention conditions.

In line with previous findings that high-intensity interval training improved cardiac function via miR-206–dependent HSP60 induction in diabetic rats, and that exercise training influences plasma volume regulation, our data further support the role of exercise intensity and oxygen availability as modulators of systemic and adipose adaptations.

A limitation of this study is that only female rats were used. While this choice is appropriate given the higher prevalence of obesity in women, potential sex-specific differences in hypoxic responses and adipose browning must be considered. Estrogen has been reported to modulate TLR4/NF-κB signaling and macrophage polarization, thereby influencing browning efficiency. Future studies including male rats are warranted to enhance translational relevance, particularly in athletic populations where sex hormones substantially affect metabolic and inflammatory adaptations49,50,51.

Although our post-hoc power analysis indicated sufficient sample size for primary endpoints (n = 10/group), secondary outcomes such as inflammatory cytokines may have been underpowered, as reflected by several borderline p values. Reporting of effect sizes and adjustment for multiple comparisons increases the robustness of these findings, yet future studies with larger cohorts are recommended.

Conclusions

Four weeks of HH and LH interventions could reduce M1 polarization of ATM, downregulate the expression levels of the TLR4-NF-κB pathway in ATM, and promote browning of white adipose tissue. The TLR4-NF-κB pathway plays a more important role in promoting the browning of white adipose tissue by regulating macrophage polarization in LH intervention.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

WHO. World Health Statistics. (World Health Organization, 2020).

Pan, X. F., Wang, L. & Pan, A. Epidemiology and determinants of obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 9, 373–392 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Body-mass index and obesity in urban and rural china: findings from consecutive nationally representative surveys during 2004–18. Lancet (British Edition). 398, 53–63 (2021).

Khanna, D., Khanna, S., Khanna, P., Kahar, P. & Patel, B. M. Obesity: A chronic Low-Grade inflammation and its markers. Cureus 14, e22711 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Macrophage polarization and meta-inflammation. Transl. Res. 191, 29–44 (2018).

Weisberg, S. P. et al. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Investig. 112, 1796–1808 (2003).

Xu, X. et al. Obesity activates a program of lysosomal-dependent lipid metabolism in adipose tissue macrophages independently of classic activation. Cell. Metab. 18, 816–830 (2013).

Bai, Y. & Sun, Q. Macrophage recruitment in obese adipose tissue. Obes. Rev. 16, 127–136 (2015).

Wynn, T. A., Chawla, A. & Pollard, J. W. Origins and hallmarks of macrophages: Development, Homeostasis, and disease. Nat. (London). 496, 445–455 (2013).

Engin, A. B. Adipocyte-macrophage cross-talk in obesity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 960, 327–343 (2017).

Fujisaka, S. et al. M2 macrophages in metabolism. Diabetol. Int. 7, 342–351 (2016).

Mills, C. D. M1 and M2 macrophages: oracles of health and disease. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 32, 463–488 (2012).

Shi, H. et al. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 116, 3015–3025 (2006).

Wynn, T. A., Chawla, A. & Pollard, J. W. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nat. (London). 496, 445–455 (2013).

Kawanishi, N., Yano, H., Yokogawa, Y. & Suzuki, K. Exercise training inhibits inflammation in adipose tissue via both suppression of macrophage infiltration and acceleration of phenotypic switching from M1 to M2 macrophages in high-fat-diet-induced obese mice. Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 16, 105–118 (2010).

Agueda-Oyarzabal, M. & Emanuelli, B. Immune cells in thermogenic adipose depots: the essential but complex relationship. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 839360–839360 (2022).

Pontes, L. P. P. et al. Resistance and aerobic training were effective in activating different markers of the Browning process in obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 275 (2023).

Rodríguez, A., Becerril, S., Ezquerro, S., Méndez Giménez, L. & Frühbeck, G. Crosstalk between adipokines and myokines in fat Browning. Acta Physiol. (Oxf). 219, 362–381 (2017).

Sakamoto, T. et al. Macrophage infiltration into obese adipose tissues suppresses the induction of UCP1 level in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 310, E676–E687 (2016).

Villarroya, F., Cereijo, R., Villarroya, J., Gavaldà-Navarro, A. & Giralt, M. Toward an understanding of how immune cells control brown and beige adipobiology. Cell. Metab. 27, 954–961 (2018).

Xu, L. & Ota, T. Emerging roles of SGLT2 inhibitors in obesity and insulin resistance: focus on fat Browning and macrophage polarization. Adipocyte 7, 121–128 (2018).

Lira, F. S. et al. Endurance training induces depot-specific changes in IL-10/TNF-α ratio in rat adipose tissue. Cytokine 45, 80–85 (2009).

Feng, J. et al. BAIBA involves in hypoxic training induced Browning of white adipose tissue in obese rats. Front. Physiol. 13, 882151–882151 (2022).

Gozal, D. et al. Visceral white adipose tissue after chronic intermittent and sustained hypoxia in mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 56, 477–487 (2017).

Orr, J. S., Kennedy, A. J. & Hasty, A. H. Isolation of adipose tissue immune cells. J. Vis. Exp. e50707. (2013).

Mathew, B. et al. Structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies of N-(3-methylpyridin-2-yl)-4-(pyridin-2-yl)thiazol-2-amine (SRI-22819) as NF-ҡB activators for the treatment of ALS. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 210, 112952 (2021).

Kayser, B. & Verges, S. Hypoxia, energy balance and obesity: from pathophysiological mechanisms to new treatment strategies. Obes. Rev. 14, 579–592 (2013).

Kelly, L. P. & Basset, F. A. Acute normobaric hypoxia increases post-exercise lipid oxidation in healthy males. Front. Physiol. 8, 293 (2017).

Netzer, N. C., Chytra, R. & Küpper, T. Low intense physical exercise in normobaric hypoxia leads to more weight loss in obese people than low intense physical exercise in normobaric sham hypoxia. Sleep. Breath. 12, 129–134 (2008).

McGinnis, G. et al. Acute hypoxia and exercise-induced blood oxidative stress. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 24, 684–693 (2014).

Guo, H., Cheng, L., Duolikun, D. & Yao, Q. Aerobic exercise training under Normobaric hypoxic conditions to improve glucose and lipid metabolism in overweight and obese individuals: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. High. Alt Med. Biol. 24, 312–320 (2023).

Kennedy, S. L., Stanley, W. C., Panchal, A. R. & Mazzeo, R. S. Alterations in enzymes involved in fat metabolism after acute and chronic altitude exposure. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 90, 17–22 (2001).

Liang, H., Yan, J. & Song, K. Comprehensive lipidomic analysis reveals regulation of glyceride metabolism in rat visceral adipose tissue by high-altitude chronic hypoxia. PLoS One. 17, e0267513 (2022).

Vogt, M. & Hoppeler, H. Is hypoxia training good for muscles and exercise performance? Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 52, 525–533 (2010).

Gangwar, A., Paul, S., Ahmad, Y. & Bhargava, K. Intermittent hypoxia modulates redox homeostasis, lipid metabolism associated inflammatory processes and redox post-translational modifications: benefits at high altitude. Sci. Rep. 10, 7899 (2020).

Shi, J., Wu, D. & Zhao, L. A case study of the effects of three-weekliving low-training highon the body composition and aerobic capacity of Wu Dajing, the winter olympic champion. J. Beijing Sport Univ. 44, 89–97 (2021).

RIUS, J. et al. NF-κB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1α. Nat. (London). 453, 807–811 (2008).

Dorrington, M. G. & Fraser, I. NF-kappaB signaling in macrophages: Dynamics, crosstalk, and signal integration. Front. Immunol. 10, 705 (2019).

Liu, T., Zhang, L., Joo, D. & Sun, S. C. NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2, 17023 (2017).

Taganov, K. D., Boldin, M. P., Chang, K. & Baltimore, D. NF-[kappa]B-dependent induction of MicroRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. PNAS. 103, 12481 (2006).

Linden, M. A., Pincu, Y., Martin, S. A., Woods, J. A. & Baynard, T. Moderate exercise training provides modest protection against adipose tissue inflammatory gene expression in response to high-fat feeding. Physiol. Rep. 2. (2014).

Mazur-Bialy, A. I., Pocheć, E. & Zarawski, M. Anti-Inflammatory properties of Irisin, mediator of physical Activity, are connected with TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 701–701 (2017).

Cereijo, R. et al. CXCL14, a brown adipokine that mediates brown-Fat-to-Macrophage communication in thermogenic adaptation. Cell. Metab. 28, 750–763e6 (2018).

Liu, P., Lin, Y., Burton, F. H. & Wei, L. M1-M2 balancing act in white adipose tissue browning - a new role for RIP140. Adipocyte. 4, 146–148 (2015).

Huang, Z. et al. The FGF21-CCL11 axis mediates Beiging of white adipose tissues by coupling sympathetic nervous system to type 2 immunity. Cell. Metab. 26, 493–508e4 (2017).

Qiu, Y. et al. Eosinophils and type 2 cytokine signaling in macrophages orchestrate development of functional beige fat. Cell 157, 1292–1308 (2014).

Nguyen, K. D. et al. Alternatively activated macrophages produce catecholamines to sustain adaptive thermogenesis. Nature 480, 104–108 (2011).

Xu, D. et al. IL-33 regulates adipogenesis via Wnt/beta-catenin/PPAR-gamma signaling pathway in preadipocytes. J. Transl. Med. 22, 363 (2024).

Saeidi, A. et al. Astaxanthin supplemented with High-Intensity functional training decreases adipokines levels and cardiovascular risk factors in men with obesity. Nutrients 15 (2), 286 (2023).

Delfan, M. et al. High-Intensity interval training improves cardiac function by miR-206 dependent HSP60 induction in diabetic rats. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 927956 (2022).

Tayebi, S. M. et al. Plasma retinol-binding protein-4 and tumor necrosis factor-α are reduced in postmenopausal women after combination of different intensities of circuit resistance training and Zataria supplementation. Sport Sci. Health. 15 (3), 551–558 (2019).

Funding

Project24-14 Supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the China Institute of Sport Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. and F.J. conducted experiments and wrote the initial draft. Y.Y. and Q.J. provided guidance on the development and implementation of the experimental plan and provided feedback on the initial draft. F.L. provided guidance on the development of the research plan and provided feedback on the initial draft. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. The study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Sport University (Ethics Approval Number: 2022169 A).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Y., Feng, J., Yan, Y. et al. LLTH induces white adipose tissue browning via NF κB inhibition in ATM. Sci Rep 15, 37716 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21537-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21537-x