Abstract

Deep learning techniques in image processing are gaining widespread application, with growing research in medical image analysis and diagnosis driven by advancements in image recognition technology. This study aimed to addresses the challenges of lung nodule recognition and classification using convolutional neural networks (CNN) and proposes a novel multiscale convolutional neural network (MCNN) model. The MCNN model integrates Gaussian Pyramid Decomposition (GPD) to enhance CNN-based image recognition for lung nodule detection. A practical study was conducted to apply the MCNN model, and its performance was compared with various algorithmic models and classifiers. Experimental results show that the MCNN model outperforms traditional CNN methods, particularly in detecting solid nodules and pure ground-glass nodules, with an improvement in F1 values of over 2.0%. Furthermore, the MCNN model demonstrated superior overall accuracy in lung nodule detection. These findings underline the practical implications of deep learning in advancing medical image analysis and diagnosis, offering new possibilities for improving the prognosis of lung nodule-relate diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent advances in deep learning for medical image analysis have demonstrated significant progress in oncology applications, particularly in lung cancer detection and classification1,2,3,4. For example, one method involves the dynamic inspection of casting defect images using the deep learning feature matching method5,6. Another method extracts features from the region of interest in test images and subsequently constructs a multilayer neural network for product defect detection7,8,9. A study proposed a learning-based framework for automatically detecting fabric defects10. Feng et al. proposed a deep active learning system to maximize the model recognition performance. Ren et al. proposed a general surface defect detection method based on deep learning which was innovative because only a small dataset was required11. These research on computer vision–based inspection techniques are increasingly carried out in different industries.

Image recognition is an essential subfield of computer vision technology and a vital application direction of deep learning. The development of deep learning technology has facilitated the use of image recognition in many fields, including object recognition12,13, facial recognition14, automatic driving15, agricultural intelligence16, aerospace17, and other fields18,19. In recent years, image recognition technology based on deep learning has provided a broader space for medical and health research, and scholars have used this technology to conduct in-depth research in the field of medical imaging and achieved remarkable research results. Examples of future research topics may include the following aspects:

-

(1)

Detection and diagnosis: Various studies have used image recognition for automatic detection and diagnosis of medical images20, such as lung nodules21, breast cancer22, and diabetic lesions23. These studies showed that image recognition im-proved the early diagnosis rate and accuracy of diseases.

-

(2)

Medical image segmentation: This process separates different tissues or organs in medical images. Many studies used image recognition for medical image segmentation, such as tumor segmentation24, blood vessel segmentation25, and so forth. These studies revealed that image recognition could improve the accuracy and efficiency of medical image segmentation.

-

(3)

Medical image alignment: This process aligns medical images at different times or in different scanning directions. Several studies used image recognition for medical image alignment, such as brain image alignment26, heart image alignment27, and so forth. These studies demonstrated that image recognition could improve the accuracy and efficiency of medical image alignment.

-

(4)

Medical image reconstruction: This process recovers medical images from low-resolution or low-quality data. Several studies have used image recognition for medical image reconstruction, such as computed tomography (CT) image reconstruction28, reconstruction of magnetic resonance imaging images29, and so forth. The results showed that image recognition could improve the accuracy and efficiency of medical image reconstruction.

In general, image recognition is widely used in medical imaging. As new research results continue to emerge, its significance is expected to play an increasingly important role in clinical diagnosis and treatment. In recent years, lung diseases have become diversified and complicated, especially since the new coronary epidemic. Some achievements have been made in medical imaging, especially in diagnosing lung diseases. Researchers have used the convolutional neural network (CNN) technique to classify and segment lung CT images to identify diseases such as lung cancer, tuberculosis, and emphysema. Unlike other studies, this study focused on identifying and classifying pulmonary ground glass nodules to provide a basis for seeking a further diagnosis of diseases and to enhance the efficiency of automatic diagnosis. Therefore, this study designed a multiscale convolution neural network (MCNN) model based on the traditional CNN model technique with the help of image Gaussian differential pyramidal decomposition. The model was applied to recognize multiple categories of lung nodules to achieve automatic labeling of lesion nodule locations and nodule categories. Moreover, the model was used to automatically mark the location of lesion nodules and identify nodule categories. Meanwhile, the feasibility and effectiveness of the model and method were verified by performing experiments with hospital-specific clinical lung nodule lesion detection imaging data to explore the search for a scientific and intelligent diagnosis method for lung nodule identification.

Methods

Related theory and model elaboration

Convolutional neural network

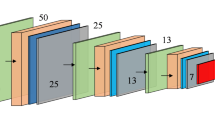

CNN is a classical deep learning algorithm (Alzubaidi et al. 2021), mainly used in image processing, speech processing, natural language processing, and other deep learning fields. CNNs are the first successfully trained deep neural networks. They are feed-forward neural networks. The basic architecture of a general CNN (shown in Fig. 1) contains an input layer, a convolutional layer, a pooling layer, a fully connected (FC) layer, and an output layer.

CNNs are made displacement, scaling, and distortion invariant for image recognition through three features: local receptive fields, weight sharing, and downsampling30.

-

(1)

Local receptive field: The area of input neurons connected to each hidden layer neuron, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

-

(2)

Weight sharing: Connected neurons share weights and biases within local receptive fields. The hidden neuron output is calculated as:

where f is the activation function, \(\:{w}_{n,m}\)is a 5 × 5 weight sharing array, \(\:{a}_{j+n,k+m}\) denotes the input activation value at position \(\:j+n,\:k+m,\) and \(\:b\) is the shared bias value.

-

(3)

Down sampling: A downsampling layer (pooling layer) is connected behind the convolutional layer to solve this problem. Downsampling simplifies the information output from the convolutional layer and reduces the resolution of the features.

Gaussian pyramid decomposition

DOG (Difference of Gaussian) is a variant of an image pyramid that uses Gaussian smoothing and difference operations to extract the scale-space information of the image. The image can generate N different resolution images after Gaussian difference pyramid decomposition. The Gaussian difference pyramid is composed of multiple groups of pyramids, where each group contains several layers. The Gaussian difference pyramid is further constructed from the Gaussian pyramid based on m-layer n-1 order. The Gaussian difference pyramid decomposition process is as follows:

Step 1: initialize \(\:i=0\).

Step 2: Sampling on the standard image \(\:I(x,y)\) to obtain the first layer image \(\:{\text{g}}_{\text{0,0}}\) of the first group of the Gaussian pyramid.

Step 3: initialize \(\:j=0,x=0\).

Step 4: Convolution of the Gaussian kernel \(\:{G}_{x}\) with the image \(\:{\text{g}}_{i,0}.\)

where \(\:{\sigma\:}_{x}\) is the smoothing parameter.

Step 5: Differentiate the Gaussian image \(\:{\text{g}}_{i,j}(x,y)\) from the Gaussian image \(\:{\text{g}}_{i,j+1}\left(x,y\right)\) to obtain the Gaussian difference image \(\:{d}_{i,x}.\)

Step 6: \(\:j=j+1,\) \(\:x=x+1,\) iterate Step4 and Step5, and when \(\:j>n-1,\) and \(\:x>n-2,\) execute Step7.

Step 7: Downsample the image \(\:{\text{g}}_{i,0}\) to get the Gaussian image \(\:{\text{g}}_{i+\text{1,0}}\) at layer \(\:i+1.\) When \(\:i+1,\) go to Step 3, and the decomposition process ends when \(\:I>m-1\) is satisfied.

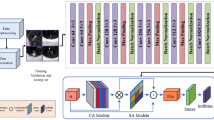

Model elaboration

Considering that CNN can automatically learn features without the need for manually designing a feature extractor, the accuracy and robustness of the model are improved. CNNs also have features such as translational invariance and spatial hierarchy, which enable them to process data, particularly images. The Gaussian difference pyramid is an effective image-processing algorithm with the advantages of scale invariance, feature extraction, computational efficiency, visualization, and so forth. This study combined the CNN structure and GPD features and constructed an MCNN model based on the traditional CNN architecture with multipixel defective images as input (shown in Fig. 3).

The MCNN model designed in this study incorporates a sophisticated nine-layer architecture that processes multiscale inputs derived from Gaussian Pyramid Decomposition. The network begins with a slice layer that separates four multiscale images (the original 640 × 640 pixels image and three Gaussian difference pyramid levels) into independent channels for initial processing. The first convolutional layer (Conv1) applies 96 filters with 9 × 9 kernels and a stride of 4 to each multiscale input, generating feature maps of dimensions 158 × 158 × 96. Following max pooling with a 3 × 3 kernel and stride of 2, the resulting 78 × 78 × 96 feature maps from all four scales are concatenated using a concatenation layer, creating a unified multiscale feature representation with 384 channels (96 × 4). This concatenated feature map then proceeds through the second convolutional layer (Conv2), which employs 256 filters with 6 × 6 kernels and stride of 1, producing 73 × 73 × 256 feature maps. After a second max pooling operation with 6 × 6 kernels and stride of 2, the 34 × 34 × 256 feature maps are processed by the third convolutional layer (Conv3) using 384 filters with 3 × 3 kernels and stride of 1, resulting in 32 × 32 × 384 feature maps. A final max pooling layer with 3 × 3 kernels and stride of 2 reduces the spatial dimensions to 15 × 15 × 384 before the fully connected layers.

The activation function used in both the convolutional layers and the fully connected (FC) layers in this model was a rectified linear unit (ReLU). Compared with the hyperbolic tangent (Tanh) and S-type (Sigmoid) functions, the ReLU activation function is a nonlinear, nonsaturated function that trains faster than saturated functions. The ReLU not only has a nonlinear expression capability but also possesses a linear nature, which makes it possible to overcome the gradient vanishing problem of the Tanh and Sigmoid functions by not causing the network to be locally optimal due to the nonlinearity when the error is backpropagated.

The network architecture concludes with three fully connected layers: the first two FC layers each contain 4096 neurons, while the final FC layer contains 5 neurons corresponding to the five classification categories (SN, PGGO, MGGO, special type, and normal type). A dropout operation with a rate of 0.5 was performed in the first two FC layers of the network to avoid overfitting problems31. Unlike the L1 and L2 normalization, Dropout does not rely on modifications to the cost function, but it changes the network itself. This multiscale processing approach enables the MCNN to capture both fine-grained textural details and broader contextual information, allowing it to effectively distinguish between different types of lung nodules while maintaining computational efficiency through the unified processing pipeline after initial multiscale feature extraction.

In this study, Softmax and support vector machine (SVM) classifiers suitable for processing multiple classification problems were used, respectively. Assuming that the training samples are \(\:\left\{\left({x}_{1},{y}_{1}\right),\left({x}_{2},{y}_{2}\right),\dots\:\dots\:,\left({x}_{k},{y}_{k}\right)\right\},\) the hypothesis function will output a six-dimensional vector to represent the classification probability values of these six classes. The specific hypothesis function \(\:{h}_{\theta\:}\left(x\right)\) is as follows:

where: \(\:{x}^{\left(i\right)}\) denotes the input, \(\:{y}^{\left(i\right)}\) denotes the output, \(\:p\left({y}^{\left(i\right)}\right)=k|{x}^{\left(i\right)},\theta\:\) denotes the probability that \(\:{y}^{\left(i\right)}\) belongs to category \(\:k\) given a known input sample \(\:{y}^{\left(i\right)}\) with model parameters \(\theta.\)

SVM can map multidimensional features to a high-dimensional kernel space, thus allowing otherwise indistinguishable data to acquire new features more conducive to classification. It is a machine learning classification method that relies on kernel functions. The radial basis of magnitude kernel function, with good classification performance, was chosen for our lung nodule recognition classification experiments. The kernel function is as follows: (where the default parameters \(\:C=10\) and \(\:\sigma\:=0.038\) were chosen)

In CNNs, the size and number of convolutional kernels were set by themselves. Different convolutional kernels extract different features, making them suitable for diverse lung nodule image recognition applications. At the same time, the Gaussian difference pyramid can detect features in the image at different scales, achieving scale invariance. This means that objects in the image can be detected regardless of their size variations, which is beneficial for recognizing the same type of lung nodules of different sizes. This study validated the effectiveness of the MCNN model incorporating GPD in lung nodule image recognition using specific clinical experimental data.

Empirical analysis-lung nodule image recognition experiment as an example

Description of the process of identifying common lung nodules

The incidence of ground glass opacity (GGO) nodules in the lungs has been increasing in recent years, and many patients are found to have multiple GGOs. However, the management of multiple GGOs is still controversial. GGOs in the lungs are an imaging presentation, encompassing various pathological types, some of which are early-stage lung cancers. A pulmonary ground glass shadow is a focal nodular hyperdense shadow in the lung that is not dense enough to obscure the bronchial vascular bundles traveling within it. They are classified as pure ground-glass opacity (PGGO), solid nodule type (SN), mixed ground-glass opacity type (MGGO), special type (S), and normal type (N) (shown in Fig. 4), depending on whether they contain a solid component. Pulmonary GGO encompasses pathological types such as malignancy, benign tumors, inflammation, interstitial lung disease, and intrapulmonary lymph nodes. Several studies suggested a close relationship between the imaging presentation and the pathology of GGO32,33,34.

A prospective clinical trial led by the National Cancer Centre in Japan included GGO35 with nodules ≤ 3 cm in maximum diameter and solid components ≤ 5 mm. The study showed that GGO progressed sequentially from PGGO to solid components visible in the lung window, to solid components visible in both the lung and mediastinal windows, and this progression was extremely slow. The Fleischner Society36 recommended that further positron emission tomography–CT for multiple GGOs should be performed if a prominent partially solid GGO lesion of 8–10 mm existed to facilitate a more accurate assessment of prognosis and optimize preoperative staging. The maximum diameter of the main multiple GGO lesion and the maximum diameter of the solid component/maximum diameter of the nodule ratio (C/T value) were references for the physician to determine the benignity and malignancy of the nodule and the timing of surgery. Kim et al. reviewed 40 cases of surgically resected PGGO and found that all PGGOs < 5 mm were benign nodules, while only 10.5% of PGGO 5–10 mm were lung malignancies37.

In practice, most lung nodule images were determined through CT scans and visual inspection by physicians. Table 1 provides the common conditions and criteria for determining lung nodule images in a hospital38,39,40.

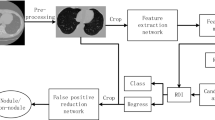

In this study, a multiscale CNN model was constructed to experimentally validate the classification and detection of lung nodule images based on common conditions and criteria. The main steps involved in the construction were as follows:

Step 1: The Caffe open-source framework for deep learning was selected as the experimental environment for building multiscale CNN models.

Step 2: During the construction of the experimental environment, raw lung nodule image data and publicly available machine learning image library data were collected using hospital CT detection equipment to form a sample dataset. The obtained lung nodule images were processed and displayed on the monitor.

Step 3: The obtained lung nodule images were intercepted, and the intact solid nodules, MGGO, PGGO, special types, and untreated normal types were selected. The detected “typical nodule images” were normalized, and the obtained image size was standardized to 640 × 640 pixels. A standard image dataset of nodules was created, and experimental samples were formed.

Step 4: The experimental samples were used to train and validate a multiscale CNN model using Softmax and SVM classifiers. Comparison experiments were conducted, and various nodal images were labeled.

Step 5: Test samples were randomly selected from each category in the standard sample image dataset, and the classification results and accuracy of the model in detecting lung nodule images were analyzed.

Data acquisition and pre-processing

Lung nodule images from hospital patients were acquired using a CT scan unit and an image acquisition card. This system obtained images of the patients’ lung nodules from the CT scan, received and transmitted image data, acquired lung nodule images, and displayed processed images on a monitor. The dataset was obtained from two primary sources: clinical lung nodule images from patients at Chongming Hospital, Shanghai University of Medicine & Health Sciences, and publicly available data from The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) Public Access database. The dataset contained over 4000 raw images extracted from different categories of images across various detection periods and publicly available machine learning image libraries.

Disparities were noted in the images of lung nodules acquired in different orientations and individual patient physical conditions. Therefore, the raw nodule images were preprocessed for normalization. In this study, lung nodule images acquired from CT scans were selected to build a standard image dataset. Complete nodule images and normal-type images were chosen, resulting in more than 4000 standard sample images. The standard image dataset was artificially extended by rotating the images to improve model training quality, resulting in more than 10,000 standard sample image datasets. These included typical real type, MGGO type, PGGO type, special type I, and normal type. The obtained standard sample image dataset was divided into three parts in a certain proportion: training set, validation set, and test set (shown in Table 2).

In this study, the acquired standard sample images underwent multi-scale preprocessing using Gaussian Pyramid Decomposition. Specifically, we implemented the Gaussian pyramid construction and Difference of Gaussians computation components from the SIFT framework to generate multi-scale representations. This process, detailed in our Gaussian Pyramid Decomposition section, created four different scale versions of each input image: the original 640 × 640 image and three additional scales derived through iterative Gaussian smoothing and difference operations (shown in Fig. 5). These multi-scale representations were then fed into our MCNN architecture to enable scale-invariant feature learning, without utilizing the subsequent keypoint detection and descriptor generation stages of the complete SIFT algorithm. The experiment focused on recognizing and classifying five types of lung nodule images, including SN type, MGGO type, PGGO type, special type, and normal type.

Model training and validation

The neural network model MCNN used in this study was implemented based on the Caffe deep learning open-source framework. Two different classification approaches were employed to conduct comparative analysis: direct end-to-end training with Softmax classifier and feature extraction followed by SVM classification.

Unified training protocol

Both approaches share a common initial training pipeline. Lung nodule images were collected from CT scans and public databases, with complete nodule locations extracted and normalized to obtain standardized 640 × 640 pixels images. Gaussian difference pyramid images were generated through the GPD technique to create multiscale datasets suitable for MCNN training. The multiresolution image training dataset was input into the network through a slice layer that separates the four multiscale images for independent initial processing. Network weights were initialized using the “Gaussian” method with biases set to “constant.” Training proceeded through iterative batch processing with forward propagation through network layers including concatenation for feature merging, error computation against ground truth labels, and backpropagation-based weight parameter tuning according to minimum error cost principles.

Classification-specific procedures

For the MCNN + Softmax approach, the model underwent direct end-to-end training where the final fully connected layer with 5 neurons directly outputs classification probabilities through the Softmax activation function. Training continued until convergence was achieved (approximately 1400 iterations) based on validation performance monitoring.

For the MCNN + SVM approach, the training process diverged after initial MCNN feature extraction. The pretrained MCNN + Softmax network (without the final classification layer) was used to extract feature vectors from the multiresolution training images. These feature vectors served as input for training five binary SVM classifiers using a one-versus-rest strategy, with each classifier distinguishing one nodule type from all others. During testing, the final prediction was determined by selecting the classifier with the highest confidence score among the five SVM outputs.

Training configuration

Both models utilized identical training parameters: batch size of 32, learning rate of 0.001 with stepwise learning policy, weight decay of 0.0005, momentum factor of 0.9, and maximum 2000 iterations with early stopping based on validation performance.

Supervised learning configuration

The multiscale pulmonary nodule recognition models were trained in a supervised manner using vector pairs consisting of normalized lung nodule images and their corresponding categorical labels representing the five classification categories (SN, MGGO, PGGO, special type, and normal type). During the training phase, RGB images underwent preprocessing by subtracting the mean RGB value from each pixel to normalize the input distribution. Table 3 provides the detailed parameter configurations used during systematic training, including the specific filter configurations and stride patterns described in the model architecture section.

The ultimate specification of network parameters for the formal training process was delineated as follows based on established best practices and literature validation: a weight decay coefficient of 0.0005 was implemented to mitigate overfitting, following the seminal work of Krizhevsky et al. who demonstrated that “this small amount of weight decay was important for the model to learn” in their ImageNet classification study41. A momentum factor of 0.9 was employed to enhance convergence, representing the widely adopted standard in deep learning optimization that provides optimal balance between convergence speed and stability42. The learning rate, set at 0.001, governed the magnitude of parameter updates during optimization, chosen based on established practices for CNN-based medical image classification that ensure stable convergence while allowing adequate parameter updates43. The learning policy adopted a stepwise progression, proven effective for systematic learning rate reduction during training phases. A modest batch size of 32 instances was selected for mini-batch training to balance computational efficiency and model generalization, considering both hardware constraints and gradient estimation quality requirements for medical imaging datasets44. The scale normalization factor was adeptly used to expedite training iterations by harnessing the computational prowess of GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) acceleration. Notably, the training procedure was limited to a maximum of 2000 iterations, determined through empirical validation of our training convergence patterns as demonstrated in Fig. 6, ensuring optimal convergence within the imposed constraints while preventing over-training.

As depicted in Fig. 6, the accuracy curve, training loss curve, and validation loss curve showcase the training process of the MCNN + Softmax model. Figure 6 illustrates that as the number of iterations increased, the model exhibited a continuous improvement in accuracy on the validation set, accompanied by a steady decrease in loss. This trend indicated that the model converged effectively, with the accuracy reaching approximately 89% after around 1400 iterations.

By directly using the converged model file obtained after 1400 iterations, the multiscale image training data were fed into this trained model to obtain the corresponding feature vectors. These feature vectors were then used to create the training dataset for training the SVM classifiers. The training dataset was divided into five different extraction approaches, and each approach was used to train a binary SVM classifier.

Code availability

The custom Python code used to generate the results reported in this paper is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to institutional data security policies and intellectual property considerations, the code cannot be made publicly available. Researchers interested in accessing the code for academic purposes should contact the corresponding author (Honglin Xiong, honyex@126.com) with a detailed description of the intended use and institutional affiliation for review and approval.

Results

Model testing and evaluation

To measure the overall performance of the proposed approach and evaluate the results of the statistical analyses, the commonly accepted confusion matrix45 was used. The metric calculations of the confusion matrix are provided in the equations below. The meanings of the abbreviations used in the equations are as follows: TP refers to True Positive, TN refers to True Negative, FP refers to False Positive, and FN refers to False Negative46.

Regarding the MCNN + Softmax network model, the model file obtained after reaching convergence at 700 iterations in training and validation was used for testing the samples. Subsequently, the model’s generalization performance was further assessed on the training dataset. A subset of 200 randomly selected images per class was extracted from the standardized sample image dataset to compose the test samples. The model’s classification outcomes on the test set, the corresponding actual classification instances, and the accuracy of the classification results were quantified using a confusion matrix, as presented in Table 4.

Comparing Table 4 with Table 5, a notable disparity was found in terms of pulmonary nodule image classification. The employment of the Softmax approach surpassed the efficacy of the SVM classifier. Specifically, the Softmax classification outperformed the SVM counterpart in terms of precision and recall measures across all nodule classes. Moreover, the overall accuracy of the Softmax model surpassed that of SVM, solidifying its superiority in the domain of pulmonary nodule image classification.

Analysis of experimental results

This study also compared the MCNN with the traditional CNN for feature extraction. The process of training and testing CNN + Softmax was essentially the same as that for MCNN + Softmax, using the same Softmax classifier. Moreover, the dataset used for each convolutional neural network was also the same. This was only a comparison test, and, as a result, the network parameters were not repeated. Finally, the same confusion matrix was used to analyze the classification results (shown in Table 6).

As shown in Table 7, MCNN + SVM was compared with MCNN + Softmax; essentially, two different classifiers were used with MCNN. The F1 values of each node was improved when using the MCNN + Softmax model, and the overall classification accuracy improved by more than 1%. This showed that using different classifiers had some influence on the recognition accuracy, and the Softmax classifier was more effective. Our experimental results reveal systematic performance differences attributable to the fundamental approaches of these classification methods. SVM’s limitations stem from its one-vs-rest decomposition strategy, where the multi-class problem is divided into five binary classifications, each potentially experiencing different class distributions during training. Softmax’s advantages derive from its integrated multi-class probabilistic framework that simultaneously optimizes all classes, providing more stable and consistent classification boundaries across all nodule types. Examination of per-class performance reveals distinct patterns: PGGO nodules show the largest improvement with Softmax (+ 5.28% F1-score), followed by MGGO (+ 5.18%) and other nodule types showing consistent gains (+ 3.23% to + 3.48%). This pattern suggests that complex or subtle nodule features benefit significantly from Softmax’s unified learning approach compared to SVM’s binary decomposition. The probabilistic outputs of Softmax also provide confidence measures crucial for medical applications, while its computational efficiency (single model vs. five binary models) offers practical advantages for clinical deployment.

Subsequently, the two models, MCNN + Softmax and CNN + Softmax, were compared. The MCNN used in this study was more accurate than the traditional CNN in terms of both F1 values of a certain class of nodules and the overall classification accuracy. In particular, the improvement in classification accuracy for SN types, PGGO types, and untreated normal types of image recognition was relatively large, with the F1 values improving by more than 2.27%. The main reason was the use of multiresolution and multiscale image sampling preprocessing enabled the features of the images to be better extracted.

Compared to similar methods, some researchers have used 3D Faster R-CNN and CMixNet47, the 3D Faster R-CNN-like architecture was used for lung nodule detection, CMixNet with U-Net-like encoder–decoder architecture was used for learning nodules’ features, model achieves accuracy of 96.33%, but only to classify the nodule as benign or malignant. Meanwhile, some scholars have done researcher conducted comparative studies on the effectiveness of lung nodule detection using different deep CNN model48,49,50, these methods such as TLbasedCNN, Ensem2DCNN, Multi-cropCNN, MMEL-3DCNN and so on., better performance was achieved in the results, in terms of accuracy, the highest reached 95.5%, in terms of F1-score, the proposed model obtains the highest reached a score of 95.24%. In comparison with their results, the accuracy and F1-score are close to our study. However, previous studies did not conduct a more fine-grained classification of different lung nodule types. In contrast, our MCNN approach in this study targets five common lung nodule types for classification. It demonstrates practical applicability and outperforms previous methods in terms of both accuracy and F1-score.

In summary, MCNN combined with the Gaussian difference pyramidal difference technique was feasible in applying lung nodal shadow recognition and classification scenarios.

Discussion

In this study, the proposed new Multiscale Convolutional Neural Network model offers several advantages over traditional methods for lung nodule classification. The advantages of CNNs are mainly in their powerful feature capture, automatic feature learning, parallel computing, scalability, robustness, and generalization, which give CNNs a significant advantage in processing complex image and vision tasks51. By integrating Gaussian Pyramid Decomposition, the MCNN can better exclude noise and invalid points, improving the accuracy of the matching. This multi-scale approach enhances the model’s ability to detect subtle differences between nodule types, which leads to improved classification accuracy. As demonstrated in our experiments, the MCNN achieved an overall accuracy of 96.48%, significantly outperforming the traditional CNN model, which had an accuracy of 92.34%. Specifically, the MCNN showed significant improvements in classifying solid nodules and pure ground-glass opacity nodules, with F1 scores increasing by over 2.0%.

Another advantage of the MCNN is reduced reliance on complex preprocessing and manual feature extraction. Traditional methods often require extensive image processing steps and handcrafted features, which can be time-consuming and prone to errors. In contrast, the MCNN leverages the automatic feature learning capabilities of deep learning, streamlining the classification process and minimizing potential sources of error.

Positioning MCNN within deep learning architectures

To contextualize our MCNN performance within contemporary deep learning architectures, our GPD-based approach offers a fundamentally different paradigm compared to established state-of-the-art models. While EfficientNetV252 achieves high performance through compound scaling and architectural optimization, ConvNeXt53 demonstrates competitive results by modernizing convolutional designs, and Swin Transformers54 utilize hierarchical feature representation with sophisticated attention mechanisms, our method prioritizes preprocessing-based multiscale feature enhancement through deterministic mathematical decomposition. This distinction provides significant computational advantages over transformer-based models that typically require substantial resources for attention computations, enabling our approach to be integrated with lightweight CNN architectures while maintaining effectiveness, a crucial consideration for resource-constrained clinical environments where deployment feasibility and computational transparency are critical factors.

Multiscale architecture comparison

Our MCNN approach occupies a unique position within the established taxonomy of multiscale CNN architectures for medical image analysis. The field has evolved through several paradigmatic approaches, each addressing multiscale feature extraction through distinct methodological frameworks. Architectural multiscale methods achieve scale diversity through network design modifications, where U-Net family approaches including the foundational U-Net55, UNet + +56, and UNet 3 +57 employ skip connections and nested architectures for multiscale feature integration. Similarly, Feature Pyramid Networks58 utilize bottom-up and top-down pathways with lateral connections, while the DeepLab series59,60 leverage dilated convolutions and Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling to build multiscale features within the network architecture itself.

Attention-based multiscale methods represent a more recent paradigm that combines scale processing with learned attention mechanisms. These approaches, including various attention U-Net variants and multi-scale attention networks, demonstrate high performance through sophisticated attention computations. However, these methods require complex attention parameter tuning and substantial computational resources for attention weight calculation during both training and inference phases.

In contrast, preprocessing-based multiscale methods, as exemplified by our approach, integrate classical pyramid techniques with CNN architecture at the data preparation stage. Our GPD-CNN combination offers several distinct advantages over existing paradigms: Firstly, it provides a mathematical foundation through Gaussian pyramids that deliver theoretically grounded scale-space representation. Secondly, it achieves computational efficiency by eliminating complex attention computations during training and inference. Thirdly, it ensures deterministic processing with consistent multiscale feature extraction across all inputs and finally, it maintains architectural simplicity by employing standard CNN structures with enhanced preprocessing rather than complex multi-branch designs. Performance evaluation demonstrates that our approach achieves 96.48% classification accuracy with F1 improvements exceeding 2.0% for solid and pure ground-glass nodules, delivering competitive results with significantly reduced computational complexity compared to attention-based methods.

Clinical workflow integration and practical implementation

The successful integration of our MCNN model into clinical practice requires careful consideration of existing radiological workflows and practical implementation challenges. In current clinical settings, lung nodule evaluation typically follows a structured approach where radiologists review CT scans, identify potential nodules, assess their characteristics, and make recommendations based on established guidelines such as the Fleischner Society recommendations or Lung-RADS criteria.

Our MCNN model can be seamlessly integrated into this workflow as a computer-aided detection and diagnosis (CAD) tool that operates in parallel with radiologist review. The proposed integration workflow would involve: (1) automatic preprocessing of incoming CT scans through our GPD-based multiscale decomposition, (2) real-time analysis and classification of detected nodules with confidence scores, (3) generation of structured reports highlighting nodules by risk category, and (4) presentation of results through the existing Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) interface familiar to radiologists.

Model limitations and future improvements

However, the MCNN model has limitations. One significant challenge is its dependence on large and diverse datasets for training. Although we utilized over 10,000 images with balanced representation across our five studied nodule types (SN, PGGO, MGGO, special-type, and normal), several categories of lung nodules were not specifically included in our classification framework. These include hamartomas, bronchial adenomas, and papillomas, which may limit the model’s applicability to the full spectrum of lung nodule pathology encountered in clinical practice. Additionally, 11% of images required additional preprocessing due to motion artifacts or suboptimal contrast enhancement, and our dataset included images from both hospital CT scanners and public databases with potentially different scanner types and imaging protocols, which may introduce inter-scanner variability and limit generalizability across different clinical systems.

The model is computationally intensive, requiring approximately 18 h for training on NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 with 10GB GDDR6X memory using 12 CPU cores and 32GB RAM. Inference time averages 0.3 s per image with memory requirements of 6GB GPU memory, which may exceed the capacity of standard clinical workstations and limit accessibility in resource-constrained clinical environments, particularly in smaller hospitals or developing regions.

Another limitation is the lack of longitudinal data, which restricts the model’s ability to track the evolution of lung nodules over time. Incorporating temporal information could enhance the model’s diagnostic capabilities and provide more insights into disease progression. Future work should focus on collecting more comprehensive datasets, employing techniques to address class imbalance such as data augmentation or weighted loss functions, and optimizing computational efficiency for broader clinical deployment.

Despite these challenges, the MCNN represents a significant advancement in automated lung nodule classification, offering higher accuracy and efficiency. Its ability to handle multi-scale features makes it a robust tool for clinical applications, potentially aiding radiologists in making more accurate and timely diagnoses.

Conclusion

This study aims to address the preliminary diagnosis of pulmonary nodules in clinical practice by proposing a novel lung nodule recognition and classification framework rooted in deep learning, specifically employing MCNN. The model is validated against clinical data obtained from public archive and Chongming Hospital, Shanghai University of Medicine & Health Sciences.

The novel MCNN model integrates Gaussian Pyramid Decomposition to enhance the classification of lung nodules in CT images. The innovative use of GPD allows the model to extract features at multiple scales, addressing the variability in nodule sizes and improving detection accuracy across different nodule types. This approach represents a significant advancement over traditional single-scale CNN models and other multi-scale methods that rely on attention mechanisms (Lung nodule detection). The experimental results reinforce this claim, demonstrating the MCNN’s superior performance and validating the methodological advancement.

The MCNN model offers positive opportunities for the field of medical imaging and lung cancer diagnosis. Its high classification accuracy can assist radiologists in making more precise diagnoses, potentially leading to earlier detection and better patient outcomes. By automating the classification process, the MCNN can reduce the workload on medical professionals, allowing them to focus on more complex cases and improving overall efficiency in clinical settings. Moreover, the methodology developed in this study can be extended to other medical imaging tasks where multi-scale feature extraction is beneficial, such as the detection of tumors in other organs or the analysis of different types of medical images, highlighting its broader impact and applicability.

To further enhance the performance and applicability of the MCNN model, several avenues for future research are proposed. First, expanding the dataset to include a larger and more diverse collection of lung nodule images will help improve the model’s generalizability and robustness. Incorporating longitudinal data will enable the model to track changes in nodules over time, providing valuable information on disease progression and response to treatment. Additionally, addressing class imbalance through advanced data augmentation techniques or modified loss functions will enable the model to perform better across all nodule types, including those less represented in the dataset. Furthermore, exploring the integration of other deep learning techniques, such as attention mechanisms or transfer learning, could further enhance the model’s feature extraction capabilities and classification accuracy. Finally, conducting clinical trials to validate the MCNN model’s performance will be crucial for its adoption in clinical practice, ensuring its reliability and effectiveness in diverse clinical environments.

Data availability

The datasets that support the findings of this study consist of two components:1. A hospital patient dataset was collected through institutional image acquisition systems. Due to privacy protection requirements and institutional review board (IRB) regulations, these data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with appropriate ethical approvals.2.Public datasets are openly accessible in The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) repository at: https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/collection/lidc-idri/.

References

Ozdemir, B., Aslan, E. & Pacal, I. Attention enhanced inceptionnext based hybrid deep learning model for lung cancer detection. IEEE Access 2025(13), 27057–27067 (2025).

Pacal, I., Akhan, O., Deveci, R. T. & Deveci, M. NeXtBrain: A novel deep learning model for brain tumor classification with multi-head cross attention and advaced hybrid blocks. Brain Res. 1863, (2025).

Pacal, I. & Attallah, O. InceptionNeXt-Transformer: A novel multi-scale deep feature learning architecture for multimodal breast cancer diagnosis. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 110, 108116 (2025).

Pacal, I. Improved vision transformer with lion optimizer for lung diseases detection. Int. J. Eng. Res. Dev. 16(2), 760–776 (2024).

Huang, S. et al. Deep learning model to predict lupus nephritis renal flare based on dynamic multivariable time-series data. BMJ Open 14(3), e071821 (2024).

Liu, Yinyang, Xiaobin Xu, and Feixiang Li. Image feature matching based on deep learning. In 2018 IEEE 4th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC). (IEEE, 2018).

Singh, S. A. & Desai, K. A. Automated surface defect detection framework using machine vision and convolutional neural networks. J. Intell. Manufact. 34(4), 1995–2011 (2023).

Zhang, D. et al. An efficient lightweight convolutional neural network for industrial surface defect detection. Artific. Intell. Rev. 56(9), 10651–10677 (2023).

Wang, J., Fu, P. & Gao, R. X. Machine vision intelligence for product defect inspection based on deep learning and Hough transform. J. Manuf. Syst. 2019(51), 52–60 (2019).

Jun, X. et al. Fabric defect detection based on a deep convolutional neural network using a two-stage strategy. Text. Res. J. 91(1–2), 130–142 (2021).

Ren, R., Hung, T. & Tan, K. C. A generic deep-learning-based approach for automated surface inspection. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 48(3), 929–940 (2017).

Wang, X. Deep learning in object recognition, detection, and segmentation. Found Trends Signal Process. 8(4), 217–382 (2016).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521(7553), 436–444 (2015).

Raji, I. D, Fried G. About face: A survey of facial recognition evaluation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.00813 (2021).

Peng, T. et al. A new safe lane-change trajectory model and collision avoidance control method for automatic driving vehicles. Exp. Syst. Appl. 141, 112953 (2020).

Bannerjee, G., Sarkar, U., Das, S. & Ghosh, I. Artificial intelligence in agriculture: A literature survey. Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Appl. Manage. Stud. 7(3), 1–6 (2018).

Che, C., Wang, H., Fu, Q. & Ni, X. Combining multiple deep learning algorithms for prognostic and health management of aircraft. Aerospace Sci. Technol. 94, (2019).

Zhang, Q. et al. Recyclable waste image recognition based on deep learning. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 171, (2021).

Traore, B. B., Kamsu-Foguem, B. & Tangara, F. Deep convolution neural network for image recognition. Eco. Inform. 2018(48), 257–268 (2018).

Silva, G. A. A new frontier: The convergence of nanotechnology, brain machine interfaces, and artificial intelligence. Front. Neurosci. 12, 843 (2018).

Zhang, B. et al. Ensemble learners of multiple deep CNNs for pulmonary nodules classification using CT images. IEEE Access 2019(7), 110358–110371 (2019).

Rodríguez-Ruiz, A. et al. Detection of breast cancer with mammography: effect of an artificial intelligence support system. Radiology 290(2), 305–314 (2019).

Lui, T. K., Tsui, V. W. & Leung, W. K. Accuracy of artificial intelligence–assisted detection of upper GI lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endoscopy 92(4), 821–830 (2020).

Thaha, M. M. et al. Brain tumor segmentation using convolutional neural networks in MRI images. J. Med. Syst. 2019(43), 1–10 (2019).

Moccia, S., De Momi, E., El Hadji, S. & Mattos, L. S. Blood vessel segmentation algorithms—review of methods, datasets and evaluation metrics. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2018(158), 71–91 (2018).

Greve, D. N. & Fischl, B. Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. Neuroimage 48(1), 63–72 (2009).

Sermesant, M., Delingette, H. & Ayache, N. An electromechanical model of the heart for image analysis and simulation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 25(5), 612–625 (2006).

Gupta, H., Jin, K. H., Nguyen, H. Q., McCann, M. T. & Unser, M. CNN-based projected gradient descent for consistent CT image reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 37(6), 1440–1453 (2018).

Montalt-Tordera, J., Muthurangu, V., Hauptmann, A. & Steeden, J. A. Machine learning in magnetic resonance imaging: image reconstruction. Physica Med. 2021(83), 79–87 (2021).

Li, G. et al. Hand gesture recognition based on convolution neural network. Clust. Comput. 2019(22), 2719–2729 (2019).

LeCun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 86(11), 2278–2324 (1998).

Kim, H. Y. et al. Persistent pulmonary nodular ground-glass opacity at thin-section CT: Histopathologic comparisons. Radiology 245(1), 267–275 (2007).

Kodama, K. et al. Treatment strategy for patients with small peripheral lung lesion(s): intermediate-term results of prospective study. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 34(5), 1068–1074 (2008).

Takashima, S. et al. CT findings and progression of small peripheral lung neoplasms having a replacement growth pattern. Am. J. Roentgenol. 180(3), 817–826 (2003).

Kakinuma, R. et al. Natural history of pulmonary subsolid nodules: a prospective multicenter study. J. Thoracic Oncol. 11(7), 1012–1028 (2016).

Naidich, D. P. et al. Recommendations for the management of subsolid pulmonary nodules detected at CT: A statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology 266(1), 304–317 (2013).

Kim, H. K. et al. Management of ground-glass opacity lesions detected in patients with otherwise operable non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thoracic Oncol. 4(10), 1242–1246 (2009).

Loverdos, K., Fotiadis, A., Kontogianni, C., Iliopoulou, M. & Gaga, M. Lung nodules: a comprehensive review on current approach and management. Ann. Thoracic Med. 14(4), 226–238 (2019).

Van Klaveren, R. J. et al. Management of lung nodules detected by volume CT scanning. New Engl. J. Med. 361(23), 2221–2229 (2009).

Larici, A. R., Farchione, A., Franchi, P., Ciliberto, M., Cicchetti, G., Calandriello, L., et al. Lung nodules: size still matters. Eur. Respirat. Rev. 26(146) (2017).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 2012(25), 1097–1105 (2012).

Sutskever, I., Martens, J., Dahl, G. & Hinton, G. On the importance of initialization and momentum in deep learning. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. 28(3), 1139–1147 (2013).

Wu, Y. & Liu, L. Selecting and composing learning rate policies for deep neural networks. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 14(2), 1–25 (2023).

Masters, D., Luschi, C. Revisiting small batch training for deep neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.07612 (2018).

Sertkaya, M. E., Ergen, B. & Togacar, M. Diagnosis of eye retinal diseases based on convolutional neural networks using optical coherence images. In 2019 23rd International Conference Electronics, Palanga, Lithuania, pp. 1–5 (2019).

Başaran, E., Cömert, Z., Şengür, A., Budak, Ü., Çelik, Y., Toğaçar, M. Chronic tympanic membrane diagnosis based on deep convolutional neural network. In 2019 4th International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK), Samsun, Turkey, pp. 1–4 (2019).

Nasrullah, N. et al. Automated lung nodule detection and classification using deep learning combined with multiple strategies. Sensors 19(17), 3722 (2019).

da Nobrega, R. V. M. et al. Lung nodule malignancy classification in chest computed tomography images using transfer learning and convolutional neural networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 32, 11065–11082 (2020).

Gao, C. et al. Deep learning in pulmonary nodule detection and segmentation: a systematic review. Eur. Radiol. 35(1), 255–266 (2025).

UrRehman, Z. et al. Effective lung nodule detection using deep CNN with dual attention mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 3934 (2024).

UrRehman, Z. et al. Effective lung nodule detection using deep CNN with dual attention mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 14, 3934 (2024).

Tan, M., & Le, Q. V. EfficientNetV2: Smaller models and faster training. Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning. 139, 10096–10106 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. A ConvNet for the 2020s. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recogn. 2022, 11976–11986 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. Proc. IEEE/CVF Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. 2021, 10012–10022 (2021).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. Med. Image Comput. Comput.-Assist. Interv. 2015(9351), 234–241 (2015).

Zhou, Z., Rahman Siddiquee, M. M., Tajbakhsh, N. & Liang, J. UNet++: A nested U-Net architecture for medical image segmentation. Deep Learn. Med. Image Anal. Multimodal Learn. Clin. Decision Supp. 2018(11045), 3–11 (2018).

Huang, H., Lin, L., Tong, R., Hu, H., Zhang, Q., Iwamoto, Y., Han, X., Chen, Y. W., & Wu, J. UNet 3+: A full-scale connected UNet for medical image segmentation. In ICASSP 2020–2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing 1055–1059 (2020).

Lin, T. Y. et al. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2017, 2117–2125 (2017).

Chen, L. C., Papandreou, G., Kokkinos, I., Murphy, K., & Yuille, A. L. Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets and fully connected CRFs. In International Conference on Learning Representations arXiv:1412.7062 (2015).

Chen, L. C., Zhu, Y., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F. & Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. Proc. Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis. 2018, 801–818 (2018).

Armato III, S. G., McLennan, G., Bidaut, L., McNitt-Gray, M. F., Meyer, C. R., Reeves, A. P., Zhao, B., Aberle, D. R., Henschke, C. I., Hoffman, E. A., Kazerooni, E. A., MacMahon, H., Van Beek, E. J. R., Yankelevitz, D., Biancardi, A. M., Bland, P. H., Brown, M. S., Engelmann, R. M., Laderach, G. E., Max, D., Pais, R. C. , Qing, D. P. Y. , Roberts, R. Y., Smith, A. R., Starkey, A., Batra, P., Caligiuri, P., Farooqi, A., Gladish, G. W., Jude, C. M., Munden, R. F., Petkovska, I., Quint, L. E., Schwartz, L. H., Sundaram, B., Dodd, L. E., Fenimore, C., Gur, D., Petrick, N., Freymann, J., Kirby, J., Hughes, B., Casteele, A. V., Gupte, S., Sallam, M., Heath, M. D., Kuhn, M. H., Dharaiya, E., Burns, R., Fryd, D. S., Salganicoff, M., Anand, V., Shreter, U., Vastagh, S., Croft, B. Y., Clarke, L. P. (2015). Data From LIDC-IDRI. The Cancer Imaging Archive

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof Fei, Prof Fan, Prof Zhang and who give their precious suggestions on improving paper quality. This study was supported by the Shanghai University of Medicine & Health Sciences Local High-level University Construction Project (Grant No. 22MC2022001), Three-Year Action Plan for Strengthening the Construction of Public Health System in Shanghai (2023-2025) of Key discipline construction project (Grant No. GWVI-11.1-49), Three-Year Action Program of the Shanghai Municipality for Strengthening the Construction of the Public Health System (Grant No. GWVI-6), Research on Key Technology of Typical Chronic Disease Management Application Based on Machine Learning Methods under the Perspective of Data Elements - Taking Chongming District as an Example (CKY2024-65) and Industry-Academia Research Practice Program for Machine Learning-Based Prediction Analysis of Atrial Fibrillation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Honglin Xiong and Yifei Lu analyzed the methods and penned the manuscript. Tao Wu gave important suggestions. Hong Liu, Junxiang Qiu and Yifei Lu drafted and reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. Tao Wu, Zhewei Fei and Panpan Zhang participated in discussions and provided some literature resources. Chongjun Fan revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

I certify that this manuscript is original and has not been published and will not be submitted elsewhere for publication while being considered by the journal Medicine. The study is not divided into multiple parts for the purpose of increasing the number of submissions to different journals or to the same journal over time. No data has been fabricated or manipulated (including images) to support our conclusions. No data, text, or theories are presented as if they were our own. The submission has been received explicitly from all co-authors. Authors whose names appear on the submission have contributed sufficiently to the scientific work and therefore share collective responsibility and accountability for the results. This study was approved by the Shanghai University of Medicine & Health Sciences Affiliated Chongming Hospital Ethics Committee, with the approval number CMEC-2023-KT-05. The study, titled Construction of a Cloud Platform for Integrated Population Health Management Throughout the Life Cycle, was conducted at Chongming Hospital, Shanghai University of Medicine & Health Sciences. All research activities were performed in accordance with ethical guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, H., Lu, Y., Qiu, J. et al. A novel method based on a multiscale convolution neural network for identifying lung nodules. Sci Rep 15, 37632 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21582-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21582-6