Abstract

Due to geographical constraints, island regions at edge distribution networks generally face challenges of resource shortages and high carbon emissions. To enhance resource utilization efficiency, this paper proposes a multi-energy utilization module (MEUM) for distributed-level island integrated energy systems (IES). The module efficiently recovers and utilizes secondary resources generated during system operation, thereby providing additional economic benefits for the system. Furthermore, to incentivize system units to participate in carbon emission reduction, the incentive-penalty stepped carbon trading mechanism (IPSCTM) is introduced in the system operation stage, which enhances the willingness of units to engage in carbon trading and reduces carbon emissions. Meanwhile, the scheduling problem of island IES that simultaneously considers efficient resource utilization and carbon emission reduction involves numerous interrelated variables, where traditional optimization methods rely on accurate models or predictive information. Therefore, to avoid modeling and prediction, this paper proposes a model-free deep reinforcement learning (DRL) approach to deal with the island IES scheduling problem. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed island IES model and solution approach, simulations are conducted based on operational datas from a representative island in northern China. The simulation results demonstrate that the proposed model can significantly reduce both the total operational cost and carbon emissions. Moreover, the proposed solution approach outperforms other methods in terms of optimization effectiveness and computational time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the ongoing transition of power systems toward digitalization, decarbonization, and intelligence, distribution networks are increasingly evolving into critical platforms for integrating diverse energy sources and enabling flexible load management. In this context, island IES at the edge of distribution networks have emerged as effective solutions for achieving energy self-sufficiency in offshore isolated regions. These systems also serve as exemplary models for large-scale renewable energy integration and utilization in regional regions. However, due to climatic fluctuations, the output power of renewable sources such as wind and solar exhibit significant power output variability1,2. Owing to their geographic isolation, island regions are unable to depend on external power grids, which makes it more challenging to maintain the balance between energy supply and demand3. Furthermore, island power systems typically exhibit low resource utilization efficiency in conventional generation units, which consequently drives up the cost of energy supply. Additionally, these regions tend to rely more heavily on fossil fuel generation, which further exacerbates carbon emissions4. Therefore, improving the resource utilization efficiency, reducing carbon emissions, and enabling predictive operation and intelligent control of systems have become critical issues in the ongoing intelligent transformation of distribution-level island IES.

In recent years, some researchers have conducted several creative studies on island IES. The authors in Ref.5 proposed a resilience assessment framework for island city IES under extreme natural hazards. The framework’s validity was demonstrated through comprehensive evaluations at both the system and component levels using multiple benchmark test systems. Ref.6 constructed a hydrothermal simultaneous transmission model to improve resource transmission efficiency in island regions. It was specifically designed to enable the simultaneous transmission of heat and freshwater. Ref.7 developed an interconnected energy management system for island clusters, while considering energy transmission constraints. The system allows for centralized management of energy supply and demand across individual islands, thereby ensuring the operational stability of the island cluster energy system. Some researchers proposed an island IES model integrating multiple energy forms, including electricity, heat, and hydrogen. They also developed a two-stage scheduling strategy to meet the energy demands of residential areas under plateau climate condition8. Ref.9proposed a bi-level optimization model to assess the resilience and economic performance of island IES under fault conditions. The model optimizes system configuration and scheduling strategies to achieve coordinated enhancements in resilience and cost efficiency. However, the aforementioned studies on island IES primarily focus on system operational resilience or economic dispatch strategies, with limited consideration for enhancing resource utilization. Specifically, the studies do not consider the utilization of secondary resources generated during the system operation stage, such as waste heat, water resources and biological by-products.

Modern energy systems are designed not only to improve the resource utilization efficiency but also to advance environmental sustainability. In line with this objective, numerous studies have investigated carbon emissions as a critical indicator of system operational performance. For limiting the system’s carbon emissions within a reasonable range, the scholars in Ref.10 introduced global carbon constraints into the optimization operation of multi-region IES. To achieve a balance between carbon emission reduction and system economic efficiency, Ref.11 developed a multi-objective low-carbon economic dispatch model for electricity-gas coupled IES. The model’s objectives included considerations for operational costs, carbon trading costs, and penalty costs. The work in Ref.12 incorporated carbon emission factors into the home energy management system and imposed certain penalties on household carbon emission behavior, thereby restricting household carbon emissions. Wang et al.13 integrated carbon capture technology into IES, incorporated carbon emissions into the operation index of IES, and created a low-carbon IES economic dispatch model. Zhang et al.14 developed a supercritical CO2 cycle system based on power-to-gas and carbon capture technologies, where the system was integrated into a power-heat coupled IES, achieving a certain degree of CO2 recycling. The study in Ref.15 integrated electric vehicle charging facilities as flexible energy storage units and developed a low-carbon economic dispatch model based on a source-load collaborative optimization mechanism. However, most of the aforementioned studies primarily focus on penalizing carbon emission behaviors, while neglecting incentives for carbon emission reduction. As a result, there is a lack of a refined carbon trading mechanism that motivates system units to actively participate in carbon trading.

The optimal scheduling problem of island IES aims to achieve both efficient resource utilization and low carbon emission. It typically involves numerous variables and optimization objectives, which makes the solution process highly complex. In recent years, several model-based solution methods have been proposed to address the challenges associated with solving such energy management problems. To overcome the conservatism problem in the planning stage of IES, a matrix affine model was presented in16 to model the behavior of distributed generators, improving the accuracy of their output predictions. In Ref.17, Gaussian and Beta distributions are employed to model and forecast solar and wind power generation, thereby addressing the stochastic optimization problem in IES. Using scenario analysis, Ref.18 predicted renewable energy output in IES and proposed an optimization method based on uncertainty probability. Nevertheless, the optimization methods involved in the aforementioned studies mainly rely on accurate models or forecasted information. In general, obtaining precise models and reliable forecasted datas is extremely challenging, which makes model-based optimization methods difficult to adapt to the dynamic real-world environment.

In response to the limitations in model-based solution methods, several scholars have proposed applying DRL approaches to energy management problems. Model-free DRL methods refer to approaches where an agent learns an optimal scheduling policy directly by interacting with the environment through trial and error, based on observed states, actions, and rewards19,20. This process does not rely on precise predictive models and is well-suited for handling stochastic optimization problems. For the economic dispatch problem of microgrids, an optimal strategy based on Q-learning was proposed by Ref.21. Building on Q-learning, Ref.22 proposed applying the deep Q-network (DQN) approach to the dynamic optimization operation of microgrids. The authors in Ref.23 applied Bayesian reinforcement learning to microgrid energy management to compensate for the power supply-demand imbalance during microgrid operation. However, the actions of DRL methods discussed above are discrete, which usually leads to sub-optimal solutions for the optimization problems. Moreover, the action space of the aforementioned methods increases substantially when they are applied to the optimization of large-scale power grids. As a consequence, both the solution speed and the accuracy decline.

To address the computational challenges arising from discrete action spaces, several studies have used policy-based DRL algorithms for continuous energy management problems. In Ref.24, the data-driven deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG)25 algorithm was employed to address the optimal scheduling problem of hybrid energy systems, achieving a balance among economic efficiency, power output fluctuations, and system stability. In Ref.26, the prioritized experience replay mechanism27 and the L2 regularization method28 were incorporated into the DDPG algorithm. The enhanced algorithm was then applied to the dynamic scheduling problem of IES, and comparative experiments demonstrated that it significantly outperforms the DDPG algorithm in computational speed and data utilization efficiency. To enhance DRL agents’ exploration efficiency29,30, Zhang et al.31 developed an energy management scheme for electricity-heat-gas coupled energy systems based on the soft actor-critic (SAC) algorithm, an off-policy algorithm derived from maximum entropy theory32. A comparative analysis with the traditional multi-objective optimization method showed that the proposed SAC-based scheduling method handles the intermittency of new energy output more effectively. In addition, an energy management scheme for electric vehicles based on the SAC algorithm was developed in Ref.33, which significantly improved the energy utilization efficiency. Inspired by these works, this paper proposes a DRL-based energy management approach for island IES. The economic dispatch problem in island IES constitutes a continuous control and optimization challenge. Consequently, policy-based DRL algorithms offer a promising solution framework for such problems. Among these, DDPG and twin delayed deep deterministic policy gradient (TD3) are two widely adopted approaches. TD3 improves upon DDPG by introducing twin critic networks and a delayed policy update mechanism, which collectively alleviate the overestimation bias of Q-values and contribute to improved training stability and convergence performance. Due to the involvement of multiple variables in the scheduling problem of low-carbon and resource-efficient island IES, the effectiveness of the scheduling strategy heavily relies on the stability and convergence performance during the training process. Therefore, this paper adopts the TD3 algorithm to solve the proposed optimization problem.

Summarizing the above studies, we can make the following conclusions: (1) In the context of energy shortages, existing research rarely considers the full utilization of secondary resources generated during island IES operation, which results in low resource utilization efficiency. (2) Existing carbon trading models for island IES mostly consider the environmental penalty costs associated with carbon emissions, while ignoring the system’s contributions to carbon emission reduction. Therefore, there is a lack of a refined carbon trading model that both incentivizes and penalizes carbon emission behavior in island IES. (3) Existing research on handling uncertainties in island IES mostly relies on accurate mathematical models or predictive information. However, in real dynamic systems, it is very difficult or even unrealistic to obtain such information.

In light of the above research gaps in island IES, this paper explores the following aspects:

-

In order to improve resource utilization, this paper constructs a distributed-level island IES model comprising wind turbines (WT), combined heat and power (CHP) units, diesel generator sets (DGS), multi-energy output hydrogen storage modules (MEO-HSM), carbon capture units (CCU), desalination units (DU) and gas boilers (GB). The MEO-HSM in the model not only facilitates the sale of oxygen by-products generated during charging stage but also utilizes the waste heat and water produced during discharging stage. Additionally, when considering the MEO-HSM, the MEUM also incorporates the trading of carbon by-products generated by the CCU operation.

-

This paper proposes the IPSCTM to further reduce carbon emissions during the island IES operation stage. Compared with traditional carbon trading mechanisms, the proposed mechanism introduces incentive and penalty factors, which greatly releases the carbon reduction potentials of system units.

-

To avoid modeling or forecasting uncertain variables, a model-free TD3 approach is proposed to address the island IES scheduling problem, which considers the coupling of electricity, heat, water, and storage systems, as well as the interaction of the IPSCTM. Besides, the TD3-based method adapts to dynamic changes in real-world systems and offers a new paradigm for intelligent optimization and predictive operation in distribution network scenarios.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: section 2 introduces the structure and mathematical description of the island IES model. Section 3 formulates the dynamic scheduling problem of the island IES as a mathematical problem. Section 4 presents the TD3-based dynamic scheduling approach for the island IES. Section 5 conducts simulations and analyzes the results. Finally, section 6 provides the conclusion of this paper.

Island IES structure

In this paper, an island IES based on the MEUM and IPSCTM is proposed. The energy needs of the island’s residents consist of electricity, heat and freshwater. Figure 1 is the schematic diagram of the system’s structure.

MEO-HSM

The MEO-HSM proposed in this paper produces hydrogen and oxygen in the electrolysis stage, where the oxygen can be traded as by-products with system operators and exported to other regions. During the discharging stage, the hydrogen fuel cell produces freshwater and waste heat, which are utilized to fulfill the islanders’ demands. Most existing studies have concentrated on the energy storage role of hydrogen storage modules, with little attention paid to the utilization of by-products generated during operation. Therefore, this paper applies the proposed MEO-HSM to the island IES with the goal of maximizing resource utilization efficiency.

Electrolyzer model

The relationship between the electrolyzer’s input electrical power and its hydrogen and oxygen output is represented as follows34:

where \(p_{\textrm{el}}(t)\) denotes the input electric power of the electrolyzer, \(m_{\textrm{el}}(t)\) denotes the amount of hydrogen produced, \(k^{\textrm{el}}\) is the hydrogen production coefficient, \(\eta _0\) is the oxygen recycling coefficient, \(m_\textrm{o}(t)\) denotes the mass of the generated oxygen, and \(\Delta T\) is the duration of one time step.

Compressor model

Following electrolysis, the produced hydrogen is compressed into hydrogen storage tanks using a compressor, which is modeled as follows:

where \(p_{\textrm{co}}(t)\) represents the electric power consumption of the hydrogen compressor, and \(k^{\textrm{co}}\) denotes its power consumption coefficient.

Hydrogen storage tank model

The model of the hydrogen storage tank is formulated as follows34:

where \({m}_{\textrm{in}}(t)\) denotes the input hydrogen of the storage tank; \(b_{\textrm{in}}(t)\) and \(b_{\textrm{out}}(t)\) denote the on/off state, respectively; \(m_{\textrm{out}}(t)\) denotes the output hydrogen mass; \({M}_{\textrm{max}}\) is the maximum storage capacity, and \(m_{\textrm{so}}(t)\) denotes the residual hydrogen mass in the tank.

MEO-HSM discharge model

The discharge process of MEO-HSM corresponds to the operation of a fuel cell, during which hydrogen is consumed and freshwater as well as waste heat are produced. The model is formulated as follows:

In Eq. (8), \(m_{\textrm{hsm}}(t)\) denotes the freshwater output of the MEO-HSM; \(\eta _{\textrm{o}}\) is the freshwater output rate; \(m_{\textrm{fc}}(t)\) represents the hydrogen consumption; \(p_{\textrm{fc}}(t)\) denotes the output electric power; \(\mu ^{\textrm{e}}\) is the conversion efficiency; \(h_{\textrm{fc}}(t)\) represents the output heat power; \(\eta _2\) is the thermoelectric ratio coefficient.

The equation for the input and output electric power of the MEO-HSM is shown as follows:

where \(p_{\textrm{hsm}}(t)\) is the charging/discharging power of the MEO-HSM.

Desalination units

The DU of the island IES is a crucial support for meeting the freshwater demand of the island’s residents. Its model is formulated as follows6:

where \(p_{\textrm{du}}(t)\) denotes the input power of the DU, Q is the utility coefficient, and \(m_{\textrm{du}}(t)\) denotes the freshwater output.

IPSCTM

In this study, the DGS, CHP, and GB generate carbon emissions during operation. The model describing their carbon emissions is as follows:

where \(E_{\textrm{e}}\) and \(E_{\textrm{g}}\) denote the actual carbon emission from diesel and natural gas production, respectively; \(\delta _{\textrm{e}}\) and \(\delta _{\textrm{g}}\) represent the carbon emission factors for per unit power of diesel and natural gas production, with values of 0.639t/MWh and 0.252t/MWh, respectively.

The WT, CCU, DGS, CHP, and GB receive a certain carbon credit during operation, which is described as follows:

where \(E_{\textrm{eq}}\), \(E_{\textrm{gq}}\) and \(E_{\textrm{w}}\) represent the carbon emission credits earned from diesel, natural gas and wind power production, respectively; \(E_{\textrm{ccu}}\) denotes the carbon emission credits earned from CCU. \(\lambda _{\textrm{e}}\), \(\lambda _{\textrm{g}}\), \(\delta _{\textrm{w}}\) and \(\delta _{\textrm{ccu}}\) indicate the amount of carbon emission credits allocated per unit of power for diesel, natural gas, wind power production and CCU operating, respectively. Their values are 0.228t/MWh, 0.102t/MWh, 0.908t/MWh, 0.695t/MWh, respectively.

The actual carbon emission and carbon emission credits of the system are as follows:

where \(E_{\mathrm {co_2}}^{\textrm{real}}\) denotes the actual carbon emissions of the system, and \(E_{\mathrm {co_2}}\) denotes the carbon emission credits.

The carbon trading cost of the constructed carbon trading mechanism is divided into the incentive and penalty components, with the trading cost described as follows:

where \(\lambda\) and \(\kappa\) denote the incentive and penalty factors, set as 0.14 and 0.11, respectively; \(\xi\) denotes the carbon trading price; \(\Delta E\) denotes the length of the carbon emission interval, which is 0.4 ton.

Economic scheduling model of island IES

Objective function

In order to reduce the power load fluctuation and fully utilize the peak shaving and valley filling effect of the MEO-HSM, the proposed model incentivizes load fluctuation reduction in the MEO-HSM. The cost of this system are the fuel cost and the carbon trading cost. The total profit consists of the incentive profit from peak shaving and valley filling, and the profit from trading carbon and oxygen products. The objective function is the fuel cost plus the carbon trading cost, minus the total profit. The optimization objective is to minimize the objective function.

where \(C_{\textrm{gas}}\) denotes the fuel cost of consuming natural gas; \(\rho _{\textrm{gas}}(t)\) denotes the price of natural gas, taken as 49.73$/MWh; \(\eta _{\textrm{chpp}}\) is the electricity output efficiency coefficient of the CHP; \(\eta _{\textrm{gb}}\) is the heat output conversion factor. \(C_{\textrm{oil}}\) is the fuel cost of consuming diesel; \(\rho _{\textrm{oil}}\) is the price of diesel ,which is taken as 41.41$/MWh. \(C_{\textrm{pc}}\) denotes the incentive profit of peak shaving and valley filling, \(\mu\) represents the conversion factor of the incentive profit, and \(p_{\textrm{load}}^-\) denotes the average electric load. \(C_{\textrm{fuel}}\) denotes the fuel cost; \(C_{\textrm{tra}}\) represents the cost of carbon trading; \(C_{\textrm{sc}}\) denotes the profit from carbon products trading; \(C_{\textrm{so}}\) denotes the profit from oxygen products trading; \(C_{\textrm{total}}\) represents the total operation cost.

This study aims to maximize the utilization of by-products generated by the CCU, using them as raw materials for trading with system operators and exporting to chemical plants in other regions. The corresponding trading profit is expressed as follows:

where \(M_{\textrm{sc}}\) denotes the amount of carbon products generated by the CCU; \(\delta _{\textrm{ccu}}\) represents the carbon product conversion efficiency, set to 0.9; \(\eta _{\textrm{ccu}}\) denotes the carbon capture efficiency coefficient, which is 0.695t/MWh; \(\xi _{\textrm{c}}\) indicates the trading price of the carbon products.

The oxygen generated by the MEO-HSM during operation can be traded with system operators and further exported to inland companies engaged in diving operations. The corresponding trading profit is formulated as follows:

where \(\xi _\textrm{o}\) denotes the trading price of oxygen products.

Constraints

The constraints of the island IES primarily consist of energy balance constraints and equipment operating constraints.

Electrical power balance constraints

The electrical power balance constraint for residential loads is described as follows:

where \(p_{\textrm{chp}}(t)\) denotes the power output of the CHP; \(p_{\textrm{dgs}}(t)\) denotes the power output of the DGS; \(p_{\textrm{wt}}(t)\) represents the power generated by the WT; \(p_{\textrm{ccu}}(t)\) represents the power consumed by the CCU; \(p_{\textrm{du}}(t)\) denotes the power consumed by the DU; \(p_{\textrm{load}}(t)\) denotes the electrical load of island residents.

Heat power balance constraints

The heat power balance constraint for the island residents is described as follows:

where \(h_{\textrm{chp}}(t)\) refers to the thermal power output of the CHP; \(h_{\textrm{gb}}(t)\) denotes the thermal power output of the GB; \(h_{\textrm{load}}(t)\) denotes the thermal load of the island residents.

In this study, the back-pressure CHP is adopted, and the relationship between its thermal and electrical power outputs is shown as follows26:

where \(\eta _{{\textrm{chph}}}\) is the heat output efficiency coefficient of the CHP.

Freshwater supply-demand balance constraints

In the island IES, the freshwater supply mainly comes from the DU and MEO-HSM. The relationship is expressed as follows:

where \(m_{\textrm{hes}}(t)\) denotes the freshwater from the MEO-HSM; \(m_{\textrm{du}}(t)\) denotes the freshwater supplied by the DU; \(m_{\textrm{load}}(t)\) refers to the freshwater demand of the island residents. It is worth mentioning that the electrical, thermal and freshwater demands of the island residents exhibit dynamic variability.

Equipment operation constraints

The operations of the CHP, DGS, CCU, GB, and electrolyzer are subject to constraints (30)-(31) , (32)-(33)26, (34), (35), and (36), respectively. The charging and discharging power of the MEO-HSM are subject to the constraint (37). Additionally, the hydrogen storage tanks operate under the constraints (38)-(39).

where \(P_{\textrm{min}}^{\textrm{chp}}\) and \(P_{\textrm{max}}^{\textrm{chp}}\) denote the lower and upper limits of the output electrical power of the CHP, respectively; \(R_{\textrm{chp}}\) denotes the upper limit of the CHP’s climbing rate; \(P_{\textrm{min}}^{\textrm{dgs}}\) and \(P_{\textrm{max}}^{\textrm{dgs}}\) denote the lower and upper limits of the DGS output electrical power, respectively; \(R_{\textrm{dgs}}\) denotes the upper limit of the climbing rate of the DGS; \(P^{\textrm{ccu}}_{\textrm{max}}\) denotes the maximum input electrical power to the CCU; \(H^{\textrm{gb}}_{\textrm{max}}\) denotes the maximum heat output power of the GB; \(P_{\textrm{max}}^{\textrm{el}}\) denotes the upper limit of the input power to the electrolyzer; \(P^{\textrm{cha}}_{\textrm{max}}\) and \(P_{\textrm{max}}^{\textrm{dis}}\) denote the upper limits of the charging and discharging power of the MEO-HSM, respectively; \(M_{\textrm{max}}\) and \(M_{\textrm{min}}\) denote the upper and lower capacity limits of the hydrogen storage tanks, respectively.

Low-carbon economic scheduling framework based on TD3

In DRL, the agent continuously adjusts and optimizes its policy through interactions with the external environment in order to maximize the cumulative reward. This interaction process between the agent and the environment can be formulated as a standard Markov Decision Process (MDP). The key components of the MDP include the state S, action A, policy \(\pi\), and reward R. The state represents the agent’s observation of the current environment. The action refers to the response taken by the agent under a given state. The policy defines the mapping from the agent’s state to its corresponding action. The reward represents the feedback received by the agent after executing an action. Figure 2 illustrates the interaction process between the agent and the environment: The agent first observes the environment to obtain the current state \(s_{t}\) and selects an action \(a_{t}\) based on the policy \(\pi\), then transitioning to the next state \(s_{t+1}\). The environment subsequently provides a reward r as feedback, which the agent uses to update its policy \(\pi\) accordingly.

The TD3 employed in this study is a DRL approach based on the actor-critic framework, which is well-suited for solving continuous decision-making problems. It introduces two sets of critic networks built upon the DDPG algorithm and mitigates Q-value overestimation by taking the minimum of the two estimated values. Meanwhile, TD3 incorporates a delayed policy update strategy, where the actor network is updated only after the critic network has undergone multiple updates. This mechanism helps reduce policy oscillations during training. Moreover, TD3 introduces noise into the target actions, which enhances the exploration ability of the policy and improves both the stability and learning efficiency of the algorithm.

The action-value function Q(s, a) of the agent is derived as:

where \(E_{\pi }\) represents the expectation with respect to the policy \(\pi\), and \(\gamma\) denotes the discount factor.

The policy that maximizes the action-value function is referred to as the optimal policy:

TD3 employs a dual Q-value network architecture to estimate the value of the next state, which is implemented as follows35:

TD3 updates the critic network’s parameters by minimizing the loss function through gradient descent, which is calculated as follows:

TD3 mitigates the risk of the algorithm being trapped in local optima by injecting noise into the target actions35.

where \(\varepsilon\) represents the added noise, and \(\tilde{a}\) denotes the target action after noise injection.

The actor network in TD3 adopts a deterministic policy gradient approach, wherein updates are carried out via backpropagation based on the gradients of the neural network. The gradient computation is expressed as follows25:

Both the target actor and target critic networks adopt a soft update strategy. This mechanism enables the target networks to be updated gradually, thereby improving the stability of the learning process. The update process is formulated as follows36:

where \(\tau\) represents the soft update coefficient.

The wind power generation, electrical load, thermal load, and freshwater demand in the proposed island IES scheduling model exhibit significant uncertainty. DRL methods are well-suited for addressing such uncertain scheduling problems. Accordingly, the dynamic low-carbon economic scheduling problem in this study can be formulated as a MDP and solved using the TD3 algorithm to obtain the optimal dynamic scheduling strategy for the island IES.

The state of the proposed scheduling model comprises the user’s electricity demand, thermal demand, freshwater demand, wind power generation, the state of charge (SOC) of the MEO-HSM, and the time step t. Therefore, the state space can be defined as:

The action space is defined by the electrical power output of the CHP, the electrical power output of the MEO-HSM, and the thermal power output of the GB. Therefore, the action space can be defined as:

DRL aims to maximize the cumulative reward, while the optimization objective is to minimize the total cost. By defining the reward as the negative cost, we transform the cost minimization problem into an equivalent reward maximization problem37,38. In this way, as the agent seeks to maximize its own cumulative reward, it simultaneously achieves the minimization of the system’s total cost. The reward function of the scheduling framework is defined as:

Figure 3 illustrates the scheduling framework of the proposed model, which comprises two main stages: the model training stage and the real-time dispatch stage. The pseudocode of the proposed framework is presented in Table 1, which provides a comprehensive overview of the solution process for the proposed scheduling problem.

Case study

The simulation of the model proposed in this study is implemented on the TensorFlow 2.7.0 platform with a Python 3.9 compilation environment, and training acceleration is provided using an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2060 GPU.

Parameter settings and model training

The island IES model used in the simulation is shown in Fig. 1. The training and testing datas are based on historical operational data from an island in northern China39. 80% of the dataset is used to train the agent to learn the optimal dynamic scheduling strategy, while the remaining 20% serves as the test set to evaluate the trained strategy’s performance. The scheduling period of the model is 24 hours, with a scheduling interval of 1 hour. The parameters involved in the island IES model are shown in Table 2. The proposed scheduling approach first requires training the scheduling model, where the selection of training parameters is crucial for model accuracy. In this study, the hyper-parameters are selected based on Ref.40. The learning rate of the actor network is set to 5e-5, the learning rate of the critic network is set to 2e-4, the discount factor is 0.95, the soft update coefficient is 0.001, and the batch size is 128. Both the actor and critic neural networks consist of two hidden layers: the first hidden layer contains 300 neurons, and the second hidden layer consists of 100 neurons.

Comparisons and analysis with other algorithms

To demonstrate the superiority of the proposed scheduling approach, we compare it with a DDPG-based scheduling approach, using parameter settings consistent with those of the proposed method. Figure 4 illustrates the reward value variation curves of both approaches during the training process. It can be observed that the TD3-based approach converges after approximately 14000 episodes, whereas the DDPG-based approach converges after approximately 15600 episodes. The reward function curve of the TD3-based approach exhibits significantly lower volatility compared to the DDPG-based approach, resulting in a more stable training process. Moreover, the final convergence value of the TD3 reward function is higher than that of DDPG, indicating that the TD3-based scheduling approach outperforms the DDPG-based approach during the training stage. It is worth noting that, due to the different initial states of each episode, the reward values exhibit fluctuations.

To further demonstrate the superiority of the proposed scheduling approach in the real-time scheduling stage, the typical daily data from real-time operational records is selected for testing. Table 3 presents the total system operation costs of the TD3-based, DDPG-based, and proximal policy optimization (PPO)-based approaches. As shown in Table 3, the proposed approach achieves the lowest total operation cost of $17335.69, while the PPO-based approach results in the highest total operation cost of $18763.57. The total operation cost of the DDPG-based approach is $17477.69. In comparison to the DDPG-based approach, the TD3-based approach reduces the total operation cost by 0.819%. This indicates that the improvements made in the network structure and update mechanism of the proposed approach enhance its scheduling performance. Additionally, compared to the PPO-based approach, the TD3-based approach achieves an 8.237% reduction in total operation cost, indicating that the proposed approach significantly outperforms the PPO-based approach in terms of data utilization efficiency and computational effectiveness. In terms of computation time, the TD3-based approach achieves the shortest computation time of 0.2090 s, while the PPO-based approach results in the longest computation time of 2.2088 s. The computation time of the DDPG-based approach falls in between, at 0.5647 s. In summary, the TD3-based approach demonstrates the best optimization performance and the shortest computation time in the real-time scheduling stage.

Analysis of scheduling results

After training, the scheduling model is deployed to execute the system dispatch. The results of electric scheduling, heat scheduling, and freshwater scheduling are shown in Fig. 5 (a), Fig. 5 (b), and Fig. 5 (c), respectively.

As illustrated in Fig. 5 (a), the proposed scheduling model effectively ensures the electricity supply-demand balance. Wind power generation is assigned higher priority, with the electricity generated primarily used to satisfy the system’s demand. The remaining electricity demand is mainly met by the DGS and the CHP. To achieve peak load shifting and valley load filling, as well as to reduce the output power fluctuations of each unit, the MEO-HSM charge during off-peak periods and discharge during peak load periods. The CCU maintain a stable operating state to reduce the system’s actual carbon emissions while simultaneously generating carbon by-products. The DU consume relatively less electrical power to produce freshwater.

As shown in Fig. 5 (b), the system’s thermal load demand is primarily met by the MEO-HSM, GB, and CHP. During peak electrical load periods, the MEO-HSM discharge and simultaneously generate a certain amount of thermal energy to partially meet the thermal load. During other periods, the thermal demand is mainly fulfilled by the CHP and GB.

As shown in Fig. 5 (c), the combined operation of the MEO-HSM and DU satisfies the system’s freshwater demand. The freshwater generated during the MEO-HSM discharging process can alleviate the pressure on the island’s freshwater supply, reduce the freshwater output of the DU, and enhance the overall energy efficiency of the island IES.

The total operation cost of the island IES comprises five components: \(C_{\textrm{so}}\) , \(C_{\textrm{sc}}\), \(C_{\textrm{pc}}\), \(C_{\textrm{tra}}\), and \(C_{\textrm{fuel}}\), as shown in Fig. 6. During periods when the system’s electrical load deviates from the average load, the MEO-HSM contributes to reducing such deviations, thereby enabling the system to receive incentive rewards. During peak load periods, the electrical demand is primarily supplied by the DGS and CHP, resulting in high fuel consumption and increased carbon emissions. Consequently, the carbon trading cost is positive during these periods. In contrast, during load valley periods, the output power of the DGS and CHP decreases, while the CCU capture carbon to obtain carbon credit. This allows the system to possess surplus carbon credits for trading, thereby generating additional revenue. In the electrolysis stage of the MEO-HSM, a certain amount of oxygen by-products are generated, while the CCU produce carbon by-products during operation. The island IES gains revenue by trading these by-products with system operators. Traditional island IES models typically account only for \(C_{\textrm{fuel}}\), overlooking the multi-level efficient utilization of resources and carbon mitigation potential. In contrast, the proposed island IES fully integrates multi-level resource utilization and prioritizes carbon emission minimization, thereby achieving enhanced environmental and economic performance.

Comparative analysis under different scenarios

To further validate the advantages of the proposed island IES over the conventional configuration, four comparative cases are conducted in this work .

Case 1: Island IES without MEUM and with conventional carbon trading mechanism.

Case 2: Island IES without MEUM and with IPSCTM.

Case 3: Island IES with MEUM and conventional carbon trading mechanism.

Case 4: Island IES with MEUM and IPSCTM.

Table 4 presents the simulation results for various cases.

By comparing Case 1 with Case 3 and Case 2 with Case 4, it can be verified that the proposed MEUM significantly enhances the utilization of secondary thermal and freshwater resources, and facilitates the trading of carbon and oxygen by-products with system operators, thereby generating additional revenue. Specifically, the total operation cost in Case 3 is reduced by 3.6719% compared to Case 1, while Case 4 achieves a 7.4551% reduction relative to Case 2. This shows that in terms of improving resource utilization and minimizing the total operation cost: the proposed MEUM is effective, and its coupling with IPSCTM yields superior performance compared to applying MEUM alone. Under the influence of IPSCTM, both the carbon trading cost and carbon emissions in Case 2 and Case 4 are lower than those in Case 1 and Case 3, respectively. In particular, Case 2 achieves reductions of 66.2213% in carbon trading cost and 27.3824% in carbon emissions compared to Case 1. Similarly, Case 4 achieves reductions of 98.0003% in carbon trading cost and 18.2639% in carbon emissions compared to Case 3. Overall, Case 4 achieves the lowest total operation cost and nearly the minimum carbon emissions among all cases. This demonstrates that the proposed island IES can significantly improve resource utilization efficiency, reduce carbon emissions, lower total operation costs, and improve the system’s economic performance and low-carbon characteristics.

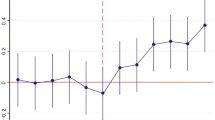

Sensitivity analysis

The carbon trading cost and carbon emissions of the island IES model proposed in this study exhibit sensitivity to variations in carbon trading parameters. As shown in Fig. 7 (a), when the carbon trading price ranges from 0.5 to 1.2 times the base price, both the carbon trading cost and carbon emissions initially decline, followed by an increase. Both the carbon trading cost and the carbon emissions reach their minimum at the base price. Figure 7 (b) presents the sensitivity analysis with respect to the incentive factor. As the incentive factor varies between 0.1 and 0.6, both the carbon trading cost and carbon emissions exhibit a non-monotonic trend. The minimum carbon trading cost occurs at an incentive factor of 0.5, while the minimum carbon emissions are observed at 0.4. Figure 7 (c) illustrates the impact of the penalty factor. As the penalty factor varies between 0.05 and 0.6, both the carbon trading cost and carbon emissions exhibit volatility. The lowest carbon trading cost is achieved at a penalty factor of 0.11, whereas the minimum carbon emissions occur at 0.55.

The sensitivity analysis of the carbon trading price, incentive factor, and penalty factor presented above reveals the impact of variations in carbon trading parameters on the system’s carbon trading cost and carbon emissions. These findings can serve as a reference for system operators when determining appropriate carbon trading parameters.

Conclusion

To ensure energy supply-demand balance in island regions, improve resource utilization efficiency from multiple dimensions, reduce the total operation cost, and minimize carbon emissions, this paper develops a novel distributed-level island IES model. To address the impact of multiple uncertainties on system scheduling, a model-free scheduling approach based on TD3 is developed, which eliminates the need for explicit modeling of uncertain variables. From the above analysis, the following conclusions can be reached:

-

The proposed island IES model integrates the MEUM, which facilitates the trading of carbon and oxygen by-products with the system operator, thereby generating additional revenue. Moreover, it maximizes the utilization of waste heat and freshwater resources generated during system operation, alleviating freshwater and thermal shortages in the island region. Simulation results indicate that under the conventional carbon trading mechanism, incorporating the MEUM leads to a 3.6719% reduction in total operation cost compared to the case without MEUM. When the IPSCTM is introduced, the total operation cost is further reduced by 7.4551% with the MEUM. These results demonstrate that the proposed model significantly improves resource utilization efficiency and reduces overall operational costs during system operation.

-

The proposed island IES model incorporates the IPSCTM. Simulation results indicate that, without the MEUM, the system’s carbon emissions under the IPSCTM are reduced by 27.3824% compared to those under the conventional carbon trading mechanism. When the MEUM is introduced, the carbon emissions are reduced by 18.2639% under the IPSCTM relative to the conventional mechanism. These results indicate that the proposed IPSCTM effectively incentivizes system units to participate in carbon trading, thereby significantly reducing overall carbon emissions.

-

The TD3-based scheduling approach learns optimal scheduling strategies through the agent’s interaction with the environment, thereby eliminating the need for modeling wind power generation and various loads. This allows the method to adapt effectively to dynamic real-world conditions. Simulation results demonstrate that, compared to other approaches, it achieves the lowest total operation cost of $17,335.69 and the shortest computation time of 0.2090 s.

-

Furthermore, this paper investigates the sensitivity of system carbon trading costs and carbon emissions under the IPSCTM. Specifically, it explores how variations in the carbon trading price, incentive factor, and penalty factor affect these outcomes. Simulation results indicate that the proposed mechanism exhibits strong adaptability across a variety of simulated environments, suggesting its potential for practical application. The findings also provide valuable guidance for system operators.

However, this study also has certain limitations.The resilience and stability of the island IES under extreme weather conditions were not considered. The current model primarily focuses on economic dispatch under normal operating conditions and does not fully account for the severe impacts of extreme weather events, such as typhoons, on the system’s secure and stable operation. Future research will focus on developing scheduling and control strategies that incorporate resilience as a key operational metric. This will ensure that the system can withstand disturbances and maintain critical functions to the greatest extent possible when faced with high-impact, low-probability extreme events.

This work aims to explore low-carbon, economically efficient models and scheduling strategies for distribution-level island IES. To further enhance scheduling accuracy, several refinements will be considered in our future research. For the power system, transmission capacity limits of lines and voltage security ranges of nodes will be considered to ensure that scheduling results do not lead to line overloads or voltage violations. For the thermal system, we will incorporate dynamic characteristics such as pipeline heat loss, transmission delays, and supply temperatures to make heat dispatch more realistic. Furthermore, the efficiency characteristics of devices will be modeled in a nonlinear manner. These works are expected to further support the digital, intelligent, and low-carbon transformation of distribution networks.

Data availability

Due to the institution’s data-sharing policy, the datasets generated and analyzed in this study are not publicly accessible. Interested researchers can request access by contacting the corresponding author via email liangyoucai@scut.edu.cn.

References

Wu, X., Tian, Z. & Guo, J. A review of the theoretical research and practical progress of carbon neutrality. Sustain. Oper.Comput. 3, 54–66 (2022).

Almoghayer, M. A., Woolf, D. K., Kerr, S. & Davies, G. Integration of tidal energy into an island energy system-a case study of orkney islands. Energy 242, 122547 (2022).

Ally, C., Bahadoorsingh, S., Singh, A. & Sharma, C. A review and technical assessment integrating wind energy into an island power system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 51, 863–874 (2015).

Han, F., Zeng, J., Lin, J., Gao, C. & Ma, Z. A novel two-layer nested optimization method for a zero-carbon island integrated energy system, incorporating tidal current power generation. Renew. Energy 218, 119381 (2023).

Jiang, T. et al. Resilience evaluation and enhancement for island city integrated energy systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 13, 2744–2760 (2022).

Li, Y., Bu, F., Li, Y. & Long, C. Optimal scheduling of island integrated energy systems considering multi-uncertainties and hydrothermal simultaneous transmission: A deep reinforcement learning approach. Appl. Energy 333, 120540 (2023).

Yang, L., Li, X., Sun, M. & Sun, C. Hybrid policy-based reinforcement learning of adaptive energy management for the energy transmission-constrained island group. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 19, 10751–10762 (2023).

Pu, Y., Li, Q., Qiu, Y., Zou, X. & Chen, W. Two-stage scheduling for island cphh ies considering plateau climate. CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems (2020).

Ma, H., Wang, Y. & He, M. Collaborative optimization scheduling of resilience and economic oriented islanded integrated energy system under low carbon transition. Sustainability 15, 15663 (2023).

Zhou, Y., Ma, Z., Shi, X. & Zou, S. Multi-agent optimal scheduling for integrated energy system considering the global carbon emission constraint. Energy 288, 129732 (2024).

Zhang, B., Hu, W., Xu, X., Zhang, Z. & Chen, Z. Hybrid data-driven method for low-carbon economic energy management strategy in electricity-gas coupled energy systems based on transformer network and deep reinforcement learning. Energy 273, 127183 (2023).

Hou, H. et al. Model-free dynamic management strategy for low-carbon home energy based on deep reinforcement learning accommodating stochastic environments. Energy Build. 278, 112594 (2023).

Wang, R., Wen, X., Wang, X., Fu, Y. & Zhang, Y. Low carbon optimal operation of integrated energy system based on carbon capture technology, lca carbon emissions and ladder-type carbon trading. Appl. Energy 311, 118664 (2022).

Zhang, G., Wang, W., Chen, Z., Li, R. & Niu, Y. Modeling and optimal dispatch of a carbon-cycle integrated energy system for low-carbon and economic operation. Energy 240, 122795 (2022).

Zhang, G., Wen, J., Xie, T., Zhang, K. & Jia, R. Bi-layer economic scheduling for integrated energy system based on source-load coordinated carbon reduction. Energy 280, 128236 (2023).

Ge, L. et al. Optimal integrated energy system planning with dg uncertainty affine model and carbon emissions charges. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 13, 905–918 (2021).

Zheng, J., Kou, Y., Li, M. & Wu, Q. Stochastic optimization of cost-risk for integrated energy system considering wind and solar power correlated. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 7, 1472–1483 (2019).

Liu, D. et al. Operation optimization of regional integrated energy system with cchp and energy storage system. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 42, 113–120 (2018).

Yi, Z. et al. Deep reinforcement learning based optimization for a tightly coupled nuclear renewable integrated energy system. Applied Energy 328, 120113 (2022).

Dolatabadi, A., Abdeltawab, H. & Mohamed, Y.A.-R.I. A novel model-free deep reinforcement learning framework for energy management of a pv integrated energy hub. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 38, 4840–4852 (2022).

Foruzan, E., Soh, L.-K. & Asgarpoor, S. Reinforcement learning approach for optimal distributed energy management in a microgrid. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 33, 5749–5758 (2018).

Harrold, D. J., Cao, J. & Fan, Z. Battery control in a smart energy network using double dueling deep q-networks. In 2020 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT-Europe) 106–110 (IEEE, 2020).

Anvari-Moghaddam, A., Rahimi-Kian, A., Mirian, M. S. & Guerrero, J. M. A multi-agent based energy management solution for integrated buildings and microgrid system. Appl. Energy 203, 41–56 (2017).

Yang, J., Liu, J., Xiang, Y., Zhang, S. & Liu, J. Data-driven optimal dynamic dispatch for hydro-pv-phs integrated power systems using deep reinforcement learning approach. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 9, 846–858 (2022).

Lillicrap, T. P. et al. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1509.02971 (2015).

Yang, T., Zhao, L., Li, W. & Zomaya, A. Y. Dynamic energy dispatch strategy for integrated energy system based on improved deep reinforcement learning. Energy 235, 121377 (2021).

Schaul, T., Quan, J., Antonoglou, I. & Silver, D. Prioritized experience replay. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.05952 (2015).

Zhou, Y., Chang, F.-J., Chang, L.-C., Kao, I.-F. & Wang, Y.-S. Explore a deep learning multi-output neural network for regional multi-step-ahead air quality forecasts. J. Clean. Prod. 209, 134–145 (2019).

Maes, F., Wehenkel, L. & Ernst, D. Meta-learning of exploration/exploitation strategies: The multi-armed bandit case. In Agents and Artificial Intelligence: 4th International Conference, ICAART 2012, Vilamoura, Portugal, February 6-8, 2012. Revised Selected Papers 4 100–115 (Springer, 2013).

De Ath, G., Everson, R. M. & Fieldsend, J. E. Asynchronous \(\varepsilon\)-greedy bayesian optimisation. In Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence 578–588 (PMLR, 2021).

Zhang, B. et al. Soft actor-critic-based multi-objective optimized energy conversion and management strategy for integrated energy systems with renewable energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 243, 114381 (2021).

Haarnoja, T., Zhou, A., Abbeel, P. & Levine, S. Soft actor-critic: Off-policy maximum entropy deep reinforcement learning with a stochastic actor. In International conference on machine learning 1861–1870 (Pmlr, 2018).

Yan, L., Chen, X., Zhou, J., Chen, Y. & Wen, J. Deep reinforcement learning for continuous electric vehicles charging control with dynamic user behaviors. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 12, 5124–5134 (2021).

Dong, X., Wu, J., Xu, Z., Liu, K. & Guan, X. Optimal coordination of hydrogen-based integrated energy systems with combination of hydrogen and water storage. Appl. Energy 308, 118274 (2022).

Fujimoto, S., Hoof, H. & Meger, D. Addressing function approximation error in actor-critic methods. In International conference on machine learning 1587–1596 (PMLR, 2018).

Nguyen, T. T., Nguyen, N. D. & Nahavandi, S. Deep reinforcement learning for multiagent systems: A review of challenges, solutions, and applications. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 50, 3826–3839 (2020).

Liang, T., Chai, L., Tan, J., Jing, Y. & Lv, L. Dynamic optimization of an integrated energy system with carbon capture and power-to-gas interconnection: A deep reinforcement learning-based scheduling strategy. Appl. Energy 367, 123390 (2024).

Lan, P., Chen, S. & Wang, F. Carbon and electricity trading for the green hydrogen-based integrated energy system: A deep reinforcement learning-based scheduling optimization. Renewable Energy 124176 (2025).

Li, Y., Wang, R., Li, Y., Zhang, M. & Long, C. Wind power forecasting considering data privacy protection: A federated deep reinforcement learning approach. Applied Energy 329, 120291 (2023).

Engstrom, L. et al. Implementation matters in deep policy gradients: A case study on ppo and trpo. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.12729 (2020).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.52477097) and Natural Science Foundation of GuangDong Province (No.2024A1515240034).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.L. Hu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Original draft preparation. J.H. Zheng: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. S.C. Yao : Writing- Reviewing and Editing. Y.C. Liang: Validation. All authors involved in this research have read and verified the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, J.H., Hu, N.L., Yao, S.C. et al. Intelligent scheduling for distributed-level island integrated energy systems considering multi-energy utilization and incentive-penalty stepped carbon trading mechanism. Sci Rep 15, 37662 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21623-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21623-0