Abstract

Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry (PRISm) is considered an early stage of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which may either revert to normal or progress to COPD. Therefore, early identification is crucial for improving patient prognosis. In this study, we developed multiple machine learning (ML) models based on inspiratory and/or expiratory breath-hold chest computed tomography (CT) images to identify PRISm. A total of 270 subjects were prospectively enrolled, and clinical models, radiomics models, and combined clinical-radiomics models were constructed using inspiratory, expiratory, and dual-phase CT images, respectively. The results demonstrated that combined models outperformed clinical models alone across all three phases. Among them, the logistic regression (LR)-based combined models using expiratory or dual-phase CT achieved the best performance, with comparable area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) values and superior performance to the inspiratory-phase models. Specifically, the AUCs (95% confidence intervals [CI]) of the clinical model in the training, internal, and external validation sets were 0.825 (0.750–0.900), 0.771 (0.639–0.903), and 0.778 (0.653–0.904), respectively. For the expiratory-phase combined model, the AUCs were 0.901 (0.845–0.956), 0.819 (0.680–0.957), and 0.817 (0.695–0.940), while for the dual-phase combined model, they were 0.901 (0.846–0.955), 0.821 (0.684–0.957), and 0.813 (0.694–0.932), indicating that adding inspiratory data did not significantly improve model performance. Based on these findings, we recommend that single-phase expiratory CT scans, combined with clinical features and analyzed using LR models, be prioritized in clinical practice for efficient PRISm identification, providing support for early diagnosis and timely intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a prevalent chronic condition that has become the fourth leading cause of death worldwide, with mortality rates increasing year by year. This disease imposes a significant economic burden on individuals, families, and society1. The Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry (PRISm) phenotype is considered a transitional state between normal lung function and COPD. According to the 2024 update of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), the definition of PRISm has been further refined. It is defined as impaired ventilatory function after inhalation of a bronchodilator, specifically a forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV₁) of less than 80% of the predicted value (FEV₁/predicted < 80%), while the ratio of FEV₁ to forced vital capacity (FVC) remains normal (FEV₁/FVC ≥ 0.7)2,3. Globally, the prevalence of PRISm ranges from 7.1 to 25.9%4. Due to the presence of nonspecific chronic respiratory symptoms in some patients, the condition is often overlooked in clinical practice. According to a five-year follow-up study from the COPDGene cohort, approximately one-quarter of PRISm patients progressed directly to GOLD stages I–IV, while 22% reverted to GOLD 0 status5. This highlights the importance of early screening in the PRISm population. Through comprehensive management strategies—such as smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation, and individualized pharmacological treatment—it is possible to achieve disease control and even pathological reversal6.

Currently, the clinical identification of PRISm primarily relies on pulmonary function testing (PFT). However, the results can be influenced by various factors, including patient cooperation, climatic changes, and physiological conditions. Furthermore, pulmonary function test (PFT) cannot directly reveal structural abnormalities in the lungs7, highlighting the urgent need for more convenient and objective imaging-based alternatives. Computed tomography (CT) scans are the most commonly used imaging modality for evaluating lung diseases. However, compared with COPD patients, individuals with PRISm often lack obvious anatomical changes, and subtle ventilation dysfunction can sometimes be difficult to accurately detect through visual assessment in routine CT images8.

With the advancement of radiomics and artificial intelligence, extracting high-dimensional quantitative features from CT images combined with machine learning algorithms has demonstrated great potential in the diagnosis, prognosis evaluation, and treatment monitoring of pulmonary diseases. Previous studies have demonstrated that the extraction of quantitative imaging features from CT scans can significantly improve the diagnostic performance for solitary pulmonary nodules9. In addition, radiomics has shown high accuracy in predicting the genetic phenotype of lung adenocarcinoma10. Yang et al. developed an Auto-Metric Graph Neural Network, which exhibited outstanding performance in the staging classification of COPD, achieving an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.98411. In addition, radiomic technology has also been used to assess the risk of COPD in patients with a background of lung cancer12, as well as the risk of deterioration in pulmonary function and disease progression in patients with COPD, providing important evidence for clinical decision-making13. Nevertheless, studies using radiomics features based on CT imaging to identify PRISm remain very limited.

Dual-phase breath-hold CT scanning can provide complementary information under different respiratory states14. However, due to the relatively high radiation dose and the need for strict patient compliance with breathing instructions, it is not feasible for some critically ill patients and has not yet been widely adopted in clinical practice. Currently, there is no established CT scanning protocol specifically aimed at identifying early pulmonary function impairment. Therefore, this study aims to further explore this field and propose a machine learning–based approach to automatically identify individuals with PRISm using single- and dual-phase CT data. The implementation of this model may offer new insights into improving the efficiency and accuracy of PRISm detection.

Materials and methods

Patients

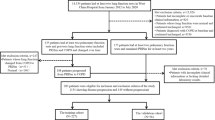

This prospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution prior to manuscript submission, as well as by the Ethics Committee of the collaborative institution, the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine (Approval Nos. 2025-E002-01 and GXUCM IRB TM2023-02–56). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) diagnosed as normal or PRISm patients through pulmonary function tests (PFT); (2) undergoing dual-phase CT scans within one week before or after completing the PFT. Patients who met any of the following exclusion criteria were not included in the study: (1) Presence of significant motion artifacts or metal artifacts in the CT images; (2) History of lung surgery or the presence of thoracic deformities; (3) Concomitant significant lung diseases, such as pulmonary masses, extensive fibrosis, lung infections, bronchiectasis, or pneumothorax; (4) Combined with primary or secondary mediastinal abnormalities such as cardiomegaly, massive pericardial effusion, or mediastinal masses; (5) Received intervention treatment in the past three months; (6) Incomplete clinical data. Ultimately, a total of 270 participants were consecutively enrolled based on the above inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Individuals who were potentially affected by other obstructive pulmonary diseases—such as bronchial asthma, extensive bronchiectasis, or obliterative bronchiolitis—were first excluded based on medical history or clinical records by two respiratory physicians (ZR.C and XL.H, with 8 and 10 years of experience, respectively). Subsequently, participants were classified into two groups based on real-time PFT results: (1) Normal group, defined as FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.70 and FEV1% predicted > 80%; (2) PRISm group, defined as FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.70 and FEV1% predicted < 80%. The dataset consisted of two sample cohorts: First, 163 participants were recruited from our hospital and randomly divided into a training set and an internal validation set in a 7:3 ratio. The training set included 116 participants (60 in the normal group and 56 in the PRISm group), while the internal validation set included 47 participants (31 in the normal group and 16 in the PRISm group). Second, an additional 107 participants (14 in the normal group and 93 in the PRISm group) were recruited from the collaborating institution (Fig. 1).

Pulmonary function assessment

PFT at both institutions were performed using the MASTERSCREEN (PFT + IOS) system (Jaeger, Germany). Environmental calibration was carried out daily to standard conditions, and volume calibration was performed each time the device was powered on. Linear validation was conducted at least once a week, ensuring that the errors in volume and linear calibration were within ± 3.0%. All patients underwent PFT within one week before or after the dual-phase CT scans. Tests were conducted in a seated position and performed by experienced respiratory physicians (ZR.C and XL.H, with 8 and 10 years of experience, respectively), both certified through the national pulmonary function clinical application and standardization training program. Quality control was strictly followed according to PFT guidelines to ensure that each patient had at least three acceptable spirometry curves. Lung volume data were recorded 20 min after the administration of a bronchodilator (salbutamol aerosol, 0.4 mg). These procedures ensured the reproducibility of PFT results across centers.

Data collection

We collected clinical information from the medical record system, primarily including the following aspects: gender, age, smoking status (classified as never smoked, former smoker, or current smoker), body mass index (BMI, categorized as underweight, normal, overweight, and obese), respiratory symptoms (classified as cough, phlegm, wheezing, dyspnea) and pulmonary function indicators (including FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, and FEV1/predicted) (Table 1).

At our institution, imaging was performed using a SOMATOM Force CT scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Germany). The specific acquisition parameters for the single-source bulb tube routine scanning mode were as follows: tube voltage of Sn100 kV, automatic tube current modulation (quality reference mAs: 150 mAs), collimator configuration of 96 × 0.6 mm, acquisition slice thickness and interval of 5.0 mm, rotation time of 0.5 s, and pitch of 1.2. The image reconstruction parameters included a matrix size of 512 × 512, reconstruction slice thickness of 0.6 mm, slice interval of 0.5 mm, a Br40 convolution kernel, and images were reconstructed using Advanced Modeled Iterative Reconstruction (ADMIRE) with a strength level of 3. For external validation at the collaborating institution, imaging was performed using a 256-slice CT scanner (Revolution CT, GE Healthcare, USA) in helical scan mode. The acquisition parameters were: tube voltage of 120 kV, tube current of 70 mA, detector coverage of 80 mm, acquisition slice thickness and interval of 5.0 mm, rotation time of 0.5 s, and pitch of 0.992:1. The image reconstruction parameters were: matrix size of 512 × 512, reconstruction slice thickness of 0.625 mm, slice interval of 0.5 mm, and application of Adaptive Statistical Iterative Reconstruction-Veo (ASIR-V) with a strength level of 30%. Prior to CT scanning, all patients received respiratory coaching and breath-hold training to ensure they could perform breath-hold scans in both full inspiration and full expiration states. The scan range extended from the thoracic inlet to the base of the diaphragm. The inspiratory breath-hold CT scan was performed first, followed by the expiratory breath-hold CT scan.

Radiation dose of dual-phase CT scanning

The dose parameters of dual-phase chest CT scans, including the CT dose index volume (CTDIvol), dose-length product (DLP), and effective dose (ED), were recorded and calculated to provide transparency and to clearly indicate the radiation exposure associated with our scanning protocols. According to the latest European guidelines on CT quality standards17, the calculation formulas are as follows: DLP (mGy·cm) = CTDIvol (mGy) × scan length (L, cm); ED (mSv) = DLP (mGy·cm) × k, where k = 0.014 mSv/(mGy·cm) for the chest. In our institution, a low-dose scanning protocol was used. The dose parameters for individual patients were as follows: CTDIvol ranged from 0.47 to 1.73 mGy; DLP ranged from 16.7 to 61.1 mGy·cm; ED ranged from 0.23 to 0.86 mSv. For the external validation cohort from the collaborating institution, the patient-specific dose parameters were as follows: CTDIvol ranged from 2.68 to 4.78 mGy; DLP ranged from 90.42 to 192.28 mGy·cm; ED ranged from 1.27 to 2.69 mSv.

Image preprocessing and segmentation

The workflow for radiomic analysis mainly includes: Region of Interest(ROI) delineation, feature extraction and selection, and model construction (Fig. 2). All images in this study were stored in DICOM format with lung window settings. All image processing and feature extraction steps followed the standardized guidelines in the Imaging Biomarker Standardization Initiative (IBSI) to ensure the reproducibility and consistency of feature extraction15. First, open-source software ITK-SNAP 3.8.0 (available at www.itksnap.org) was used to perform intensity normalization adjustments for window width and level on the CT images to ensure that lesions were clearly visible. Next, through intensity standardization techniques, the window width and level of the CT images were set to standard lung window parameters (window width 1400 HU, window level -400 HU). All results were processed using Z-score normalization, which involves calculating the mean and standard deviation of the pixel values to convert the intensity values into a standard normal distribution. This allows for better observation of the target regions and minimizes the effects caused by different CT device parameters, ensuring accurate texture analysis. Finally, the three-dimensional ROI were resampled to a uniform voxel size of 1 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm to achieve standardization of spatial resolution. The specific steps for image segmentation were as follows: First, the “One-key AI” platform based on PyTorch 1.8.0 (https://www.medai.icu) was used to perform an initial segmentation of the entire lung field, removing most of the background structures (such as ribs and chest wall) to quickly obtain the contours of both lungs. Next, manual slice-by-slice refinement of the lung parenchyma ROI was performed using ITK-SNAP software. In both inspiratory and expiratory CT images, the boundaries of the bilateral lungs were manually delineated slice by slice along the edges of the lung fields. During the entire image segmentation process, we focused on removing non-pulmonary structures that could significantly interfere with radiomic feature extraction, such as the trachea, main bronchi, and mediastinal tissues. Additionally, we made efforts to eliminate large vessels and bronchi near the pulmonary hilum, retaining only the distal, progressively branching bronchi, vessels, and lung parenchyma to enhance segmentation consistency and ensure the accuracy of the analysis results.

Radiomic feature extraction and selection

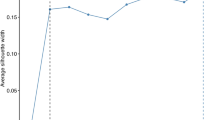

Traditional radiomic features were extracted using Pyradiomics (version 2.2.0) from both inspiratory and expiratory phase CT images, resulting in 108 features extracted from each phase. Due to the merging or removal of some highly correlated or redundant features during feature extraction and preprocessing, as well as the generation of composite features based on combined data from both phases, a total of 215 features were ultimately extracted from the dual-phase fused CT images. These features mainly included shape features, neighborhood gray tone difference matrix (NGTDM), gray level size zone matrix (GLSZM), gray level run length matrix (GLRLM), gray level difference matrix (GLDM), gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), and first-order features. In the training cohort, the feature selection process was carried out as follows: First, the extracted raw feature values were standardized using Z-score normalization. Next, the Mann–Whitney U test was used to perform statistical analysis of all radiomic features between the normal and PRISm groups, and features with statistically significant differences between the two groups (P < 0.01) were selected. Subsequently, Pearson correlation analysis was employed to eliminate features that were highly correlated with each other (Pearson correlation coefficient > 0.9). On this basis, the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) algorithm was further employed for feature selection. LASSO is a linear regression method that introduces an L1 norm penalty term into the loss function, which drives some feature coefficients to shrink to zero, thereby achieving automatic feature selection and model simplification. Finally, tenfold cross-validation was used to determine the optimal regularization parameter λ, allowing us to identify the most representative subset of features for predicting the PRISm phenotype. In total, 17 radiomic features were selected for model construction (Table 2). The feature selection process, using expiratory-phase CT as an example, is illustrated in Fig. 3. All feature selection steps were conducted within the training cohort.

Feature selection process. Distribution and corresponding p-values of the extracted features. Each data point represents the measured value of a specific radiomics feature extracted from expiratory-phase CT images. The black line in the middle indicates the median, and the width of the violin plot reflects the data point density (a). Radiomics feature selection based on the LASSO algorithm and Rad score establishment. Each curve represents the change in the coefficient of a feature with varying values of lambda. The dotted vertical line indicates the optimal lambda value, at which the model achieves the best predictive performance (b). Mean squared error (MSE) curve under ten-fold cross-validation to determine the optimal lambda value. The blue vertical lines indicate the range of coefficient variation for each feature across the 10 cross-validations, and the red dots represent the average coefficient values (c). Figures were automatically generated using the Onekey AI platform, and font sizes and label styles follow system defaults.

Model construction and evaluation

Using recursive feature elimination (RFE) and a logistic regression (LR) classifier, inspiratory-phase, expiratory-phase, and dual-phase clinical models, radiomics models, and combined clinical-radiomics nomogram models were constructed based on selected radiomic features and relevant clinical factors, including age, sex, smoking status, BMI, and respiratory symptoms. All models were developed using the same machine learning algorithms and procedures. This study employed ten candidate machine learning algorithms, including LR, NaiveBayes, support vector machine (SVM), RandomForest, ExtraTrees, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), lightweight gradient boosting machine (LightGBM), gradient boosting, adaptive boosting (AdaBoost), GradientBoosting and multilayer perceptron (MLP). As shown in Table 3, using expiratory-phase CT as an example, the performance of the most commonly used machine learning models was compared. Among them, the LR model demonstrated the best overall predictive performance across the training, internal validation, and external validation cohorts. It achieved stable and superior results in several key metrics, including AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and negative predictive value. Notably, in the external validation cohort, the LR model achieved the highest AUC of 0.817 and an accuracy of 0.916, indicating its strong generalizability and discriminative capability. Therefore, LR was ultimately selected as the modeling method for this study. All models were developed based on the training cohort and validated in both the internal and external validation cohorts. The model’s prediction results were output in the form of probabilities, with a default classification threshold of 0.5 used to convert the predicted probabilities into binary outcomes. During model training, the platform automatically enabled the "class weight adjustment" function, which effectively mitigated potential bias caused by class imbalance and improved the model’s ability to recognize minority classes. To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the constructed models, we conducted assessments from three aspects: discrimination ability, calibration performance, and clinical utility. The model’s discrimination ability was assessed through Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis, which included calculating the AUC, sensitivity, and specificity. The goodness of fit is evaluated using the Hosmer–Lemeshow (H–L) test calibration curve, which assesses the relationship between the predicted probabilities and the actual observed events. In addition, we also used decision curve analysis (DCA) to evaluate the clinical utility of the model. It provides a visual representation of the model’s net benefit at different threshold probabilities, where the threshold probability represents the minimum predicted risk at which the patient or clinician is willing to accept an intervention. Net benefit takes into account both the gain from true positives and the potential harm from false positives16.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 24.0; IBM Corp.) and the "One-key AI" platform. Categorical variables were processed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. For continuous variables with a normal distribution, independent sample t-tests were employed, while non-normally distributed data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. To evaluate the diagnostic performance of each model, we plotted ROC curves and calculated the AUC. Comparisons of model AUCs were conducted using the DeLong test, with a P-value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical baseline characteristics of patients

In this study, there was no significant age difference between the normal controls and PRISm patients in both the training and testing groups (P > 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test). However, there were significant differences in gender distribution across the three groups, with a notably higher proportion of male patients in the PRISm group (training set: P < 0.001, chi-square test; validation set: P < 0.001, Fisher’s exact test). Significant differences were also observed in smoking status among the three groups, with most PRISm patients having a history of smoking (training set: P < 0.001, chi-square test; validation set: P < 0.001, Fisher’s exact test). There were no significant differences in BMI distribution between the two groups (P > 0.05, Fisher’s exact test), and the proportions of overweight and obesity were similar; however, the proportion of normal-weight patients in the training set was nearly twice as high in the normal group as in the PRISm group. Differences in respiratory symptoms among the groups were not statistically significant (P > 0.05, Fisher’s exact test). Regarding pulmonary function, the PRISm group had significantly lower FVC, FEV1, and FEV1% predicted values compared to the normal group (P < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U test), while the FEV1/FVC ratio showed no significant difference (P > 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test) (Table 1).

Reproducibility assessment of radiomic features

This study evaluated the consistency of radiomic feature extraction using the built-in OnekeyComp-Modules-ICC module on the platform, based on intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), including both inter-observer and intra-observer analyses, to verify its reliability. Initially, image quality assessment and preliminary segmentation were performed by a radiologist (L.F, with 9 years of experience) blinded to the patients’ clinical information and pulmonary function results. Another senior radiologic technologist (Y.C, with 15 years of experience) independently re-segmented a randomly selected subset of cases (20%) to assess inter-observer variability. The automatically calculated average inter-observer intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.82. Two weeks later, the same technologist re-segmented the same set of cases to evaluate intra-observer consistency, yielding an average intra-observer ICC of 0.89. The results showed that most key features had ICC values greater than 0.80, indicating high reproducibility. Features with ICC values below 0.75 were excluded from further analysis.

Evaluation of clinical and radiomic models

This study adopted a standardized and objective approach to evaluate the diagnostic performance of different models. The results demonstrated that while both clinical variables and radiomic features held independent predictive value, the combined model integrating clinical variables and radiomic features consistently exhibited superior predictive performance across all cohorts in terms of AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. The ROC curves of the training, internal validation, and external validation cohorts for the three-phase CT scans are shown in Fig. 4. As shown in Table 4, for inspiratory-phase CT in the training, internal validation, and external test sets, the AUCs and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the combined model were 0.890 (0.834–0.947), 0.810 (0.677–0.944), and 0.845 (0.732–0.958), respectively, the corresponding ACC values were 0.828, 0.809, and 0.888; sensitivity: 0.679, 0.812, and 0.925; specificity: 0.957, 0.806, and 0.643; PPV: 0.950, 0.684, and 0.945; and NPV: 0.763, 0.893, and 0.562 (Fig. 4a-c). For expiratory-phase CT in the training, internal validation, and external test sets, the AUCs and 95% CI of the combined model were 0.901 (0.845–0.956), 0.819 (0.680–0.957), and 0.817 (0.695–0.940), respectively. ACC: 0.836, 0.830, and 0.916; Sensitivity: 0.750, 0.750, and 0.968; Specificity: 0.917, 0.871, and 0.571; PPV: 0.894, 0.750, and 0.937; NPV: 0.797, 0.871, and 0.727 (Fig. 4d-f). For dual-phase CT, the AUCs and 95% CI in the training, internal validation, and external test sets of the combined model were 0.901 (0.846–0.955), 0.821 (0.684–0.957), and 0.813 (0.694–0.932), respectively. ACC: 0.836, 0.787, and 0.626; Sensitivity: 0.786, 0.812, and 0.581; specificity: 0.883, 0.774, and 0.929; PPV: 0.863, 0.650, and 0.982; NPV: 0.815, 0.889, and 0.250 (Fig. 4g-i). Overall, the results suggest that both dual-phase CT and expiratory-phase CT exhibit high predictive performance for identifying PRISm and demonstrate comparable diagnostic efficiency.

Performance of clinical, radiomic, and clinical-radiomic models in predicting PRISm using inspiratory-phase, expiratory-phase, and dual-phase CT. (a-c) ROC curves for the clinical model, radiomic model, and clinical-radiomic model based on inspiratory-phase in the training cohort (a), internal test cohort (b), and external test cohort (c), respectively. (d-f) ROC curves for the clinical model, radiomic model, and clinical-radiomic model based on expiratory-phase in the training cohort (d), internal test cohort (e), and external test cohort (f), respectively. (g-i) ROC curves for the clinical model, radiomic model, and clinical-radiomic model based on dual-phase in the training cohort (g), internal test cohort (h), and external test cohort (i), respectively. The red solid line, dark blue dashed line, and light blue solid line represent the predictive performance of the clinical model, radiomics model, and combined model, respectively. Figures were automatically generated using the Onekey AI platform, and font sizes and label styles follow system defaults.

To compare the robustness of the model across different scanners, we applied the DeLong test to evaluate the difference in AUCs obtained from the expiratory-phase CT scans of the internal validation cohort (Siemens CT scanner) and the external validation cohort (GE CT scanner). The results indicated that the model demonstrated relatively consistent predictive performance across different scanning devices (P = 0.841). We evaluated the clinical applicability of the model constructed from expiratory-phase CT using DCA. The combined model demonstrated significant net benefits in the training (Fig. 5a), internal testing (Fig. 5b), and external testing (Fig. 5c), indicating its advantages in clinical decision-making and showing high consistency with the actual event proportions. The calibration curves showed that the combined model constructed using expiratory-phase CT exhibited good agreement between the predicted probabilities and the actual outcomes in the training cohort (Fig. 6a), internal validation cohort (Fig. 6b), and external validation cohort (Fig. 6c).

Decision curve analysis (DCA) results of the three models based on expiratory-phase CT images across the three cohorts. Panels (a), (b), and (c) show the DCA curves for the training cohort, internal test cohort, and external test cohort, respectively. The blue, orange, and green lines represent the net benefits of the clinical model, radiomics model, and combined model (integrating clinical and radiomics features), respectively. The black dashed line indicates the strategy of treating no patients, while the black solid line indicates the strategy of treating all patients. The combined model demonstrated higher net benefit across a range of decision thresholds, suggesting its superior clinical utility in identifying PRISm. Figures were automatically generated using the Onekey AI platform, and font sizes and label styles follow system defaults.

Calibration curves in the three cohorts using expiratory-phase CT: training cohort (a), internal test cohort (b), and external test cohort (c). The calibration curves were plotted based on three models to evaluate the accuracy of predicted probabilities for PRISm. The x-axis represents the predicted probability of PRISm from the clinical model, radiomics model, and combined model, while the y-axis indicates the actual observed probability. Each data point reflects the agreement between predicted and observed event rates within a specific probability interval. The 45° diagonal line represents the ideal prediction, and the blue, yellow, and green curves represent the predictive performance of the clinical model, radiomics model, and combined model, respectively. Figures were automatically generated using the Onekey AI platform, and font sizes and label styles follow system defaults.

Discussion

This study evaluated the performance of various diagnostic models based on single-phase inspiratory breath-hold CT, single-phase expiratory breath-hold CT, and dual-phase breath-hold CT in identifying the PRISm phenotype, including clinical models, radiomics models, and combined models integrating both. The results showed that although inspiratory CT alone demonstrated some efficacy in identifying PRISm, the combined models based on expiratory CT or dual-phase CT achieved the best performance. Moreover, adding inspiratory CT to the expiratory CT-based models did not lead to a significant improvement in performance. Therefore, to reduce radiation exposure and simplify the examination process, the results of this study suggest that single-phase expiratory CT scans be prioritized in clinical practice. When combined with clinical features and analyzed using a LR-based machine learning model, this approach allows for effective identification of pre-COPD patients. This strategy is simple, efficient, and offers good reproducibility and generalizability, providing a feasible solution for computer-aided individualized management of patients with the PRISm phenotype.

Previous studies have shown that conventional inspiratory phase CT holds significant value in identifying early structural damage in COPD. This is primarily achieved by examining morphological changes in the airway tree and lung fields, accurately quantifying emphysematous changes, observing low-density areas, and conducting detailed assessments of changes in the airway and pulmonary vascular system, thus enabling precise diagnosis18,19,20,21. However, some studies have shown that by analyzing the quantitative parameters of inspiratory phase and expiratory phase CT, expiratory-phase CT is more accurate than inspiratory-phase CT in reflecting structural changes in the lungs of COPD patients, particularly in the assessment of small airway lesions22,23,24. Cao et al. also noted that expiratory CT scans reflect the severity of disease in COPD patients more accurately than inspiratory CT scans when assessing pulmonary vascular parameters25. A six-year prospective study on COPD in the context of lung cancer found that, compared to inspiratory-phase CT, texture analysis based on expiratory-phase CT demonstrated superior diagnostic performance, allowing for more effective detection of early declines in lung function26. This study also found that expiratory CT outperformed inspiratory CT in identifying the PRISm phenotype. Furthermore, the model constructed by combining expiratory CT images with clinical features achieved a maximum AUC of 0.901. During the expiratory phase, the damaged airways are more prone to collapse, and the structural damage to the lungs leads to increased air trapping. Expiratory-phase CT can more clearly display this phenomenon compared to inspiratory-phase CT, thereby identifying small airway obstruction and dysfunction27,28.

Dual-phase CT can simultaneously obtain images of the inspiratory and expiratory phases, recording the dynamic changes during the breathing process. This technique assesses the distribution of ventilation and its heterogeneity under different respiratory states, providing quantitative data that assist doctors in more accurately quantifying the pathological changes in COPD and predicting the progression of the disease29. Another study utilized a convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture that combines inspiratory and expiratory CT images with clinical information, demonstrating high accuracy and sensitivity in detecting COPD30. In line with our research, both studies focus on the assessment of COPD patients, with the main distinction being the differences in research methods and subjects. We utilized the LR machine learning method to detect PRISm patients, while the other study employed deep learning methods to identify COPD patients, both achieving high detection efficacy.

We referenced recent studies that confirm machine learning methods can effectively identify quantitative CT imaging features associated with stable PRISm patients31. Additionally, the LR model we employed is a widely used model, primarily aimed at extracting key features from medical imaging for classification and prediction. Currently, it has been extensively applied in the diagnosis and risk assessment of breast cancer, rectal cancer, and brain tumors 32,33,34. In addition, it has also demonstrated good performance in the early diagnosis of acute exacerbations of COPD35, the classification of severity in COPD patients36, and risk prediction 37. This study affirms the high efficacy of the LR machine learning model constructed using dual-phase CT in diagnosing PRISm. It also emphasizes that single expiratory-phase CT is more suitable for clinical application than dual-phase CT and possesses strong diagnostic potential. As noted by Zhang et al. in their review of 373 COPD patients, single expiratory-phase CT combined with deep learning algorithms can effectively reflect small airway obstruction, thereby enabling the detection of early COPD patients38. Previous studies on the prediction of PRISm using nomogram models based on dual-phase quantitative CT have emphasized the advantages of dual-phase CT scanning while also highlighting the clear benefits of single expiratory-phase CT8. This is consistent with our study, both highlighting the importance of expiratory-phase CT.

This study has several limitations. First, spirometry was not used as a trigger for CT scanning, making it difficult to confirm whether the images were acquired at maximum inspiration and expiration. Second, differences in scanners across institutions may affect image quality and model generalizability. Notably, in the external validation cohort, the clinical-inspiratory model achieved the highest AUC, suggesting that inspiratory-phase images may offer greater stability under heterogeneous scanning conditions. Third, the external validation set exhibited class imbalance, which may introduce bias in the prediction results. Although the platform’s built-in class weight adjustment feature was enabled and we supplemented the evaluation with multiple performance metrics, further validation in a more balanced dataset is still needed. Fourth, although a combination of manual and automated lung segmentation was employed, inconsistencies may still exist, and some pulmonary vessels and airways may not have been fully excluded. Future studies will aim to incorporate more advanced deep learning-based segmentation methods and expand the sample size across multiple centers and scanner types to improve model accuracy and generalizability.

In summary, our study proposed and validated an LR combined model based on breath-phase CT, which integrates clinical and radiomic features and shows significant diagnostic performance in distinguishing normal individuals from those with PRISm. Especially in primary or community hospitals where PFT equipment is lacking, this repeatable approach utilizes chest CT images acquired under standardized respiratory training and imaging conditions to extract features, which are then input into the LR combined model to automatically generate a predicted probability of PRISm. This enables the identification of patients with potential pulmonary function impairment without the need for additional radiation exposure or examination procedures. According to our study, PRISm patients show no significant symptomatic differences compared to normal individuals. Therefore, the application of this model not only addresses diagnostic gaps in the absence of noticeable clinical symptoms but also offers a novel approach for the early screening and diagnosis of PRISm. This, in turn, promotes the development of personalized medicine and facilitates timely intervention and treatment. Future research should further explore the potential applications of this model in monitoring disease progression and evaluating treatment efficacy.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), <https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd)> (2024).

Magner, K. M. A. et al. Assessment of preserved ratio impaired spirometry using pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry in a randomly sampled symptomatic cohort. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 208, 1129–1131 (2023).

Yang, S., Liao, G. & Tse, L. A. Association of preserved ratio impaired spirometry with mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 32, 170 (2023).

Marott, J. L., Ingebrigtsen, T. S., Çolak, Y., Vestbo, J. & Lange, P. Trajectory of preserved ratio impaired spirometry: natural history and long-term prognosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 204, 910–920 (2021).

Wan, E. S. et al. Longitudinal phenotypes and mortality in preserved ratio impaired spirometry in the COPDGene study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 198, 1397–1405 (2018).

Sun, Y. & Zhou, J. New insights into early intervention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with mild airflow limitation. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 14, 1119–1125 (2019).

Haynes, J. M., Kaminsky, D. A., Stanojevic, S. & Ruppel, G. L. Pulmonary function reference equations: a brief history to explain all the confusion. Respir. Care. 65, 1030–1038 (2020).

Lu, J. et al. Subtyping preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) by using quantitative HRCT imaging characteristics. Respir. Res. 23, 309 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Value of CT-based deep learning model in differentiating benign and malignant solid pulmonary nodules ≤ 8 mm. Acad. Radiol. 31, 5250–5260 (2024).

Lee, G., Bak, S. H. & Lee, H. Y. CT radiomics in thoracic oncology: technique and clinical applications. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 52, 91–98 (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. Lung radiomics features selection for COPD Stage classification based on auto-metric graph neural network. Diagnostics (Basel). 12, 2274 (2022).

Zhou, T. et al. CT-based radiomic nomogram for the prediction of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with lung cancer. Acad. Radiol. 30, 2894–2903 (2023).

Lynch, D. A. et al. CT-definable subtypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a statement of the fleischner society. Radiology 277, 192–205 (2015).

Eslick, E. M. et al. CT ventilation imaging derived from breath hold CT exhibits good regional accuracy with Galligas PET. Radiother. Oncol. 127, 267–273 (2018).

Zwanenburg, A. et al. The image biomarker standardization initiative: standardized quantitative radiomics for high-throughput image-based phenotyping. Radiology 295, 328–338 (2020).

Alba, A. C. et al. Discrimination and calibration of clinical prediction models: users’ guides to the medical literature. JAMA 318, 1377–1384 (2017).

Bongartz, G., Golding, S. J., Geleijns, J. & Jessen, K. A. European guidelines on quality criteria for computed tomography, <https://www.drs.dk/guidelines/ct/quality/htmlindex.htm> (EUR 16262 EN).

Park, J. et al. Subtyping COPD by using visual and quantitative CT imaging features. Chest 157, 47–60 (2020).

Mondoñedo, J. R. et al. CT imaging-based low-attenuation super clusters in three dimensions and the progression of emphysema. Chest 155, 79–87 (2019).

Washko, G. R. Diagnostic imaging in COPD. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 31, 276–285 (2010).

Wu, Y. et al. Deep CNN for COPD identification by multi-view snapshot integration of 3D airway tree and lung field. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 79, 104162 (2023).

Wang, W. T., Wang, X. H., He, B. & Shen, N. Imaging phenotypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on biphasic quantitative CT features. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 101, 2242–2245 (2021).

Beşir, F. H. et al. The benefit of expiratory-phase quantitative CT densitometry in the early diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 18, 248–254 (2012).

Zhang, D., Guan, Y., Fan, L., Xia, Y. & Liu, S. Y. Quantitative analysis of emphysema and air trapping at inspiratory and expiratory phase multi-slice spiral CT scan in smokers: correlation with pulmonary function test. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 98, 1467–1473 (2018).

Cao, X. et al. Potential value of expiratory CT in quantitative assessment of pulmonary vessels in COPD. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 8, 761804 (2021).

Sørensen, L. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease quantification using CT texture analysis and densitometry: results from the danish lung cancer screening trial. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 214, 1269–1279 (2020).

Labaki, W. W. et al. The role of chest computed tomography in the evaluation and management of the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 196, 1372–1379 (2017).

Gaeta, M. et al. Expiratory CT scan in patients with normal inspiratory CT scan: a finding of obliterative bronchiolitis and other causes of bronchiolar obstruction. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 8, 44 (2013).

Pompe, E. et al. Five-year progression of emphysema and air trapping at CT in smokers with and those without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the COPDGene study. Radiology 295, 218–226 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with deep learning using inspiratory and expiratory chest computed tomography and clinical information. J. Thorac. Dis. 16, 6101–6111 (2024).

Lukhumaidze, L., Hogg, J. C., Bourbeau, J., Tan, W. C. & Kirby, M. Quantitative CT imaging features associated with stable PRISm using machine learning. Acad. Radiol. 32, 543–555 (2025).

Yang, H. J. et al. Application of deep learning to predict advanced neoplasia using big clinical data in colorectal cancer screening of asymptomatic adults. Korean J. Intern. Med. 36, 845–856 (2021).

Kang, J. S. et al. Risk prediction for malignant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: logistic regression versus machine learning. Sci. Rep. 10, 20140 (2020).

Butzen, J. et al. Discrimination between neoplastic and nonneoplastic brain lesions by use of proton MR spectroscopy: the limits of accuracy with a logistic regression model. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 21, 1213–1219 (2000).

Shah-Mohammadi, F. & Finkelstein, J. Combining NLP and machine learning for differential diagnosis of COPD exacerbation using emergency room data. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 305, 525–528 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. A novel CT-based radiomics features analysis for identification and severity staging of COPD. Acad. Radiol. 29, 663–673 (2022).

Shen, X. & Liu, H. Using machine learning for early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a narrative review. Respir. Res. 25, 336 (2024).

Zhang, L., Jiang, B., Wisselink, H. J., Vliegenthart, R. & Xie, X. COPD identification and grading based on deep learning of lung parenchyma and bronchial wall in chest CT images. Br. J. Radiol. 95, 20210637 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the use of the Onekey AI platform for figure generation and radiomics processing.

Funding

This work was supported by a research grant from the Innovation Project of Guangxi Graduate Education [Grant numbers YCBZ2023106].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LF acquired the funding, conceived the survey, analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. YC and HQL analyzed and collected the data. XYW,YJW and HQL were involved in the project administration. QJW and HMD contributed to the study’s conception. LLL designed and supervised the study, and revised the manuscript, All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, L., Cui, Y., Wang, X. et al. Machine learning models using dual-phase CT radiomics for early detection of PRISm. Sci Rep 15, 39409 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21995-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21995-3