Abstract

Carnatic music, the classical art form of South India, demands precise shruti (pitch) alignment, a skill novice learners often struggle to internalize within traditional oral pedagogies. This study examines the effectiveness of a culturally responsive Visual Pitch Meter (VPM) designed to enhance pitch internalization through real-time visual feedback. A quasi-experimental, mixed-methods design engaged 50 novice Carnatic vocal students (25 experimental, 25 control) across 16 sessions over 8 weeks, integrating auditory training with VPM assistance. Grounded in Constructivist learning theory, Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), and the Responsibility Alignment Framework for Learning Dynamics (RALD), the intervention reduced pitch deviation in the experimental group from 7.24 Hz to 1.14 Hz (Cohen’s d = 0.54, p < 0.001). Teacher-rated accuracy and student self-efficacy also improved significantly (p < 0.001). Qualitative analysis revealed recurring themes of empowerment, initial technological adjustment, and eventual learner independence, supporting quantitative trends. Aligned with Sustainable Development Goals 4, 9, and 11, the VPM offers a scalable, culturally sensitive framework for modernizing oral music pedagogy without undermining its heritage-based learning ethos.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional carnatic music pedagogy and the importance of shruti

Carnatic music, the classical tradition of South India, places shruti, the nuanced alignment of pitch, at the very heart of its melodic architecture. Rooted in the ancient doctrine of 22 microtonal divisions, shruti is not merely a technical construct but a deeply embodied practice that guides the expressive and structural integrity of every raga16,31. Within the guru-shishya (teacher-student) tradition, the internalization of shruti is cultivated through close imitation, iterative correction, and immersive listening. Yet for novice learners, especially those with limited auditory discrimination or inconsistent access to mentorship, this process can be profoundly challenging. Imitation, long regarded as a cornerstone of oral transmission, has been shown to enhance musical retention and motor learning across diverse pedagogical contexts1,24, reinforcing its relevance even in contemporary settings.

Visual feedback and cross-cultural perception of pitch

While this oral tradition emphasizes gradual mastery through embodied practice, recent pedagogical research demonstrates that visual feedback technologies can complement traditional methods by scaffolding pitch acquisition without compromising cultural authenticity34. Notably, cross-cultural studies suggest that even listeners unfamiliar with Indian classical music can intuitively perceive structural boundaries in rāga performances, indicating that pitch contour and phrasing are cognitively accessible across musical cultures18. In Western classical pedagogy, real-time pitch visualization tools have shown measurable benefits in vocal training15,27, yet their adaptation to Carnatic music’s distinctive 12-interval octave and microtonal nuances (sruti bhedam) remains under-explored11. This gap presents both a technical challenge, requiring tools sensitive to Carnatic pitch precision, and a cultural imperative to balance innovation with tradition28.

Study objectives and theoretical framework

Grounded in Vygotsky’s (1978) Zone of Proximal Development and the Responsibility Alignment Framework for Learning Dynamics (RALD)3, this study addresses three sequential objectives: First, we evaluate how a culturally adapted Visual Pitch Meter (VPM) scaffolds pitch internalization through immediate color-coded feedback (green = accurate, red = deviation), enabling learners to progress through successive competency levels with decreasing external support. Second, we examine the tool’s impact on the guru-shishya dynamic through RALD’s lens, assessing how shared responsibility for pitch correction evolves when students gain visual self-monitoring capabilities. Third, we develop a transferable model for technology integration that respects Carnatic music’s improvisational essence while expanding access to precision training.

The theoretical framework informs each objective: Constructivist principles manifest in the VPM’s design, which provides scaffolded feedback26 through (1) initial dependence on visual cues, (2) transitional self-checking, and (3) eventual internalization - mirroring Vygotsky’s movement from other-regulation to self-regulation. RALD’s emphasis on distributed learning responsibility aligns with our analysis of how teachers shift from corrective to facilitative roles as students gain autonomy.

This research advances multiple UN Sustainable Development Goals: By democratizing access to precision pitch training (SDG 4 - Quality Education), our work supports equitable musical development regardless of innate auditory ability or teacher availability. The VPM’s innovative design (SDG 9 - Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) demonstrates how culturally responsive technologies can sustain artistic traditions while modernizing pedagogy. Most significantly, by enhancing rather than replacing the guru-shishya tradition (SDG 11 - Sustainable Cities and Communities), we show how technology can preserve intangible cultural heritage - a crucial consideration for Carnatic music’s global transmission25.

Prior studies establish that musicians exhibit enhanced auditory processing12 and benefit from multi-sensory training8, but they have not examined how visual feedback tools can be adapted for microtonal traditions while maintaining pedagogical authenticity. Our work bridges this gap through rigorous mixed-methods evaluation of both quantitative outcomes (pitch deviation reduction) and qualitative impacts (learner autonomy, teacher experiences). The findings will inform ongoing debates about technology’s role in cultural arts education, offering empirical evidence that tools like the VPM can expand - rather than diminish - access to traditional mastery when thoughtfully implemented.

Technology and cultural sustainability in carnatic music

Carnatic music is deeply rooted in an oral pedagogical system where melodic precision and microtonal accuracy are paramount. Central to this tradition is shruti, the nuanced alignment of pitch that forms the tonal foundation for every raga (scales) and composition. Unlike the standardized intervals of Western music, Carnatic music’s reliance on subtle pitch inflections and microtonal intervals demands highly developed auditory skills and fine-grained vocal or instrumental control13,14. The guru-shishya tradition has historically fostered these skills through close, immersive training, where students internalize pitch relationships through imitation, iterative correction, and contextual performance.

In contemporary settings, however, sustaining such intensive one-on-one mentorship is increasingly challenging, particularly for novice learners navigating hybrid or independent learning environments. As a result, educators and researchers have turned to digital technologies as supplementary tools to support shruti internalization and pitch accuracy. While these innovations have shown promise in analytical and archival domains, their pedagogical application within Carnatic music remains limited. This emerging intersection of tradition and technology warrants closer examination, particularly in how digital tools might enhance, rather than disrupt, established oral transmission practices.

Technological advancements in carnatic music education

When we look at how technological advancements have evolved in the field of music, both for listeners and learners, it’s remarkable. Initially, we used gramophones, followed by transmitters, radios, televisions, pocket MP3 players, mobile phones, and then apps within mobile phones exclusively for music learning and listening, as well as online music education platforms, virtual concerts, and more. Especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a noticeable increase in the use of online mediums for disseminating music across various platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and others. In this context, several software tools and applications now support Carnatic music education, including pitch trackers for improving intonation accuracy, rhythm (tala) trackers, and many more11. As mentioned earlier, pitch is the most important factor in Carnatic music, there is a popular phrase “Shruti matha, Laya Pitha” which means Shruthi is the mother and Rhythm is the father of music. Given the tradition’s 12-interval octave and microtonal nuances, precise pitch articulation is essential14. Pitch histograms have aided raga analysis20, but their application in learner-centered pedagogy is limited, often focusing on academic analysis rather than practical learning. For instance, Author Koduri et al.11 emphasized pitch detection accuracy but did not address how such tools could scaffold novice learning, a gap this study seeks to fill. Recent computational models specifically addressing gamakas and ornamentations in Carnatic music offer technical groundwork for adapting pitch visualization tools to its microtonal framework6,32, while neuroscientific research on microtonal pitch perception in trained Carnatic musicians provides crucial evidence on auditory processing demands unique to this tradition12. Recent work by Author Suhalka25, highlights the potential of digital tools in Carnatic pedagogy, yet lacks empirical evidence on learner outcomes, underscoring the need for such studies.

Constructivist learning and feedback integration

Constructivism emphasizes active learning through experience, resonating with the guru-shishya model’s focus on guided practice23. Technology can enhance this by providing immediate feedback, as seen in prior studies. Vygotsky’s ZPD underscores the role of scaffolding in skill development33, while RALD highlights shared responsibility between teacher and student, fostering adaptive learning3. This concept of shared responsibility highlights the role of a teacher and student in the process of learning, were both of them need to perform their roles/responsibilities properly to achieve the desired goal. Integrating cognitive load theory, Kalyuga10 argues for minimizing unnecessary mental effort in instructional design, which supports the VPM’s immediate feedback structure. Furthermore, Renkl and Atkinson19 advocate phased transitions from example-based study to independent problem-solving in cognitive skill acquisition, a principle central to the VPM’s scaffolded learning process. However, Jonassen9 cautions that technology in Constructivist settings must be carefully integrated to avoid over-reliance, a concern we address by examining the VPM’s role in fostering independence. Visual feedback has shown promise in music education7, but its application in non-Western traditions like Carnatic music remains under-explored. This is particularly significant as global analyses of real-time visual feedback in vocal pedagogy, suggesting similar pedagogical value for traditions like Carnatic music17.

Research gap

In contrast to the pivotal position of internalization of shruti within Carnatic music pedagogy, traditional models have focused exclusively on auditory feedback within the guru-shishya paradigm. While real-time visual feedback systems have demonstrated efficacy in Western vocal pedagogy and emerging technologies explore multi-sensory pitch training21, their application to Carnatic music’s microtonal precision remains underdeveloped. Although recent technology has enabled pitch tracking and computational raga analysis, these applications have largely remained at an academic or archival level, with minimal adoption in learner-focused pedagogic contexts. Existing tools often prioritize analytical precision over pedagogical engagement11, failing to address the unique cognitive and cultural demands of Carnatic music education. Recent calls for music education models that both innovate and preserve cultural authenticity22,35 align with this study’s approach. Additionally, global policy frameworks such as UNESCO’s Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap (2020) emphasize inclusive, culturally responsive pedagogies and scalable educational innovations, principles embedded in the VPM’s design and delivery29. The broader scalability of such tools for marginalized learning contexts is further supported by emerging models for educational innovation in emergency and underserved situations. This study bridges these gaps by integrating Constructivist principles, ZPD, and RALD with a Visual Pitch Meter specifically designed to enhance shruti internalization while preserving the guru-shishya tradition’s collaborative essence.

Methodology

The Visual Pitch Meter is a software based pitch visualiser tool with a digital scale range from − 15 to + 15 and also shows the frequency range from 247 Hz to 277 Hz (as shown in Figs. 1 and 2). This is an educational tool designed to guide musicians, particularly in Carnatic music, in achieving precise pitch alignment and internalizing shruti. It provides real-time visual feedback on frequency deviations, allowing practitioners to identify discrepancies and immediately correct their alignment. The colour codes represent the level of deviation caused, green - accurate, yellow and orange - slight deviation and red - huge deviation. The VPM’s color-coded feedback (−15 to + 15 scale) was designed to minimize extraneous cognitive load20, ensuring novice learners focus on pitch correction rather than tool interpretation. By bridging auditory learning with visual representation, the pitch meter enhances self-evaluation and aids in refining pitch.

accuracy through a structured process of unlearning inaccuracies, relearning correct intonations, and internalizing the correct pitch. Rooted in Constructivist learning principles, the tool scaffolds the learning process, promotes self-regulation, and fosters independence in practice. It complements traditional teacher-led instruction by offering both novice and intermediate practitioners the ability to actively engage with pitch accuracy. This innovative tool empowers users to refine their musical skills, blending traditional auditory methods with a modern, visual approach to music pedagogy.

Also grounded in the RALD framework, it complements traditional learning by promoting a shared responsibility between teachers and students in the processes of learning, unlearning, and relearning. Teachers use the tool to guide students, while students actively refine their pitch accuracy and confidence.

Together, the pitch meter, constructivism, and RALD emphasize adaptability and collaboration, bridging traditional methods with modern pedagogy for meaningful learning experiences.

Study design

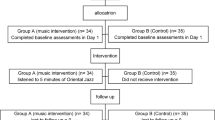

A quasi-experimental, mixed-methods triangulation design was adopted, combining quantitative pitch deviation data with qualitative participant reflections and teacher observations. The study spanned 8 weeks, comprising 16 sessions, in a naturalistic classroom setting at music schools in Chennai, India.

Participants

A purposive sampling strategy targeted beginner-level Carnatic vocal students with baseline pitch accuracy challenges, reflecting best practices in music education research for specialized populations. This study involved 50 novice Carnatic music learners (aged 7–14 years) with no more than six months of prior formal training, ensuring the study specifically targeted beginners at an early stage of pitch internalization. The students were not categorized under any specific qualities (like already well aligned with pitch, musical background, exposure of music etc.,). The procedure involved randomly assigning the students to either an experimental group (n = 25), which received VPM-assisted training, or a control group (n = 25) that followed traditional auditory instruction. Informed consent was obtained from all parents or guardians prior to participation, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the research committee.

Procedure

Both groups followed identical lesson plans delivered by experienced Carnatic music teachers. The experimental group used the VPM during independent practice, receiving real-time visual feedback (green: accurate, yellow/orange: slight deviation, red: large deviation). The control group relied solely on auditory feedback from teachers. Sessions were structured to include vocal exercises and simple melodies, with pitch accuracy logged throughout (as shown in Figs. 3 and 4).

Results and findings

To triangulate quantitative findings and capture learner experiences, qualitative data were collected through three sources: reflective journals from 25 experimental group participants, structured feedback from five Carnatic music instructors, and detailed field notes from 16 training sessions. Reflective journals, maintained weekly, captured learner perspectives on Visual Pitch Meter (VPM) use and its influence on pitch accuracy, confidence, and practice habits. Instructor feedback assessed observable changes in learner autonomy and pitch precision, while field notes recorded contextual classroom interactions and independent corrections.

Data were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) Thematic Analysis, a rigorous, flexible method suited for experiential data4. The process included familiarization with the dataset, initial code generation, theme development, theme review, definition, and reporting. This qualitative inquiry contextualized the VPM’s role within Carnatic pedagogy, offering insight into how technological scaffolds supported pitch internalization, improved self-monitoring, and reduced reliance on oral correction, aligning with constructivist learning principles. Quantitative data on pitch deviation (Hz) were collected using the VPM for the experimental group and teacher evaluations for the control group. We calculated accuracy and correction needs as:

To objectively assess shruti alignment in learner performances, we quantified pitch deviation (in Hz) and used two key metrics: accuracy and correction needs. Accuracy reflects the proportion of notes intoned within an acceptable pitch range, providing a standardized measure of intonation proficiency. Correction needs indicate how often a learner’s pitch deviated beyond a preset tolerance, capturing both technical errors and pedagogical effort.

These formulas allow for clear, data-driven comparisons between learners using the Visual Pitch Meter (VPM) and those receiving only teacher feedback. This approach addresses limitations in earlier studies, which emphasized pitch detection precision without evaluating learner-centered outcomes or the instructional burden on teachers11.

Emergent themes

Theme 1: empowerment through visual feedback

A dominant theme emerging from participant feedback was the sense of empowerment gained from immediate, real-time visual validation provided by the Visual Pitch Meter. Learners consistently expressed that the instant feedback mechanism alleviated their dependency on teacher corrections during practice sessions. One student noted:

“The green signal gave me instant confirmation I was on shruti without waiting for sir’s feedback.” (Participant 14, Week 4). This qualitative observation was quantitatively substantiated through statistically significant improvements in teacher-rated pitch accuracy.

Furthermore, the intervention’s positive effect extended to learners’ self-efficacy. Self-assessment scores increased from 2.2 ± 0.7 to 4.5 ± 0.5 following the intervention, also statistically significant at p < 0.001. These results validate the hypothesis that visual feedback systems not only improve pitch accuracy (as shown in Figs. 5 and 6) but also foster learner autonomy and confidence. The inclusion of qualitative reflections alongside quantitative metrics was intentional. In line with constructivist pedagogical frameworks, this mixed-methods approach ensured a holistic understanding of learner experience. It captured both measurable skill improvement and the cognitive-affective impact of visual scaffolding in traditional Carnatic pedagogy. Pre-intervention scores averaged 2.3 ± 0.8, which rose to 4.4 ± 0.6 post-intervention, with a Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test revealing p < 0.001, indicating a highly significant improvement in accuracy (as shown in Fig. 7).

Theme 2: initial technological challenges

Early sessions revealed a period of adjustment for both students and teachers as they navigated the unfamiliar Visual Pitch Meter interface. Frustration and confusion gradually gave way to productive engagement. As one participant reflected:

“The red warning frustrated me until I learned to use it as a guide rather than seeing it as failure.“(Participant 7, Week 2).

The quantitative data highlighted an expected adaptation curve as both learners and teachers familiarized themselves with the Visual Pitch Meter (VPM). In Session 1, the highest mean pitch deviation was recorded at 7.24 ± 0.89 Hz, indicating initial difficulty in achieving pitch accuracy with the new tool. As participants became more adept at interpreting the visual feedback, particularly the red warning indicators, pitch deviations steadily decreased over time. By Session 16, the mean deviation had reduced significantly to 1.14 ± 0.42 Hz (p < 0.001, ANOVA F = 30.325, η² = 0.697) (as shown in Table 2). This progressive improvement reflects a clear learning curve consistent with qualitative reports of initial frustration followed by gradual mastery. The data supports the conclusion that, while integrating new technology may momentarily disrupt established pedagogical routines, structured, scaffolded sessions effectively help learners overcome early challenges and successfully incorporate visual feedback tools into their musical practice.

Pitch deviation reduction

Each group had 16 sessions spread across a period of 2 months. During the sessions, the teachers were instructed to note the deviation in pitch for all the students for all the sessions and maintain a log for future references. On precisely following the process, we found that the experimental group’s pitch deviation decreased from 7.24 Hz to 1.14 Hz over 16 sessions, compared to the control group’s reduction from 7.18 Hz to 2.88 Hz (Table 1).

Table Explanation : Session - Tests whether pitch deviation changed over the 16 sessions, ignoring which group they belonged to. Session × Experimental Group Tests - whether the pattern of pitch deviation reduction across sessions was different between the VPM and control groups (key effect). Residuals - Represents unexplained variance (error) left after accounting for both the above effects.

A Repeated Measures ANOVA was conducted to compare pitch deviation changes across 16 sessions in two groups: learners with a Visual Pitch Meter (VPM) and those without it. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of Session (F(2.692, 129.195) = 2291.778, p < 0.001, η² = 0.900), indicating that pitch accuracy improved significantly across sessions for all participants. These findings confirm the pedagogical value of integrating real-time visual feedback in Carnatic music instruction. A Repeated Measures ANOVA showed significant effects for session (F (2.69, 128.88) = 2291.778, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.900), group (F(1,48) = 370.214, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.062), and their interaction (F (2.69, 128.88) = 30.325, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.012), indicating faster improvement with the VPM (Tables 2 and 3).

Table Explanation : F(1,48) = 370.214, p < 0.001 - There’s a highly significant difference between the experimental and control groups in terms of average pitch deviation. η² = 0.062 - The group factor alone explains about 6.2% of the total variance in pitch deviation, small to moderate effect. η²G = 0.697 - When accounting for the repeated-measures nature of the design, group membership explains about 69.7% of the variance, a large and substantial effect. ω² = 0.790 - Omega-squared also indicates a large effect size (79% of the variance in pitch deviation is reliably attributed to group difference).

Statistical analysis

In this study, Cohen’s d was used to quantify the magnitude of difference in pitch variation between sessions with and without VPM, expressed in units of pooled standard deviation. This provided a clear, standardized measure of how meaningfully VPM influenced pitch stability over time, beyond simply determining statistical significance.

-

Without VPM: The average pitch variation across sessions = 5.07 (as shown in Table 1).

-

With VPM: The average pitch variation across sessions = 4.20 (as shown in Table 1).

Pooled Standard Deviation

-

Without VPM Standard Deviation: 1.65.

-

With VPM Standard Deviation: 1.58.

-

Pooled SD = 1.62.

Cohen’s d Formula

Interpretation of Cohen’s d = 0.54.

-

Moderate effect → This suggests VPM has a significant impact on pitch variation.

-

The difference is noticeable and it’s evident that VPM contributes to better pitch stability over time.

The overall effect size, Cohen’s d = 0.54, 95% CI [0.32, 0.75], indicates a moderate impact of the VPM on pitch stability.

This tells us that, on average, the pitch variation with VPM is about 0.54 pooled standard deviations lower than without VPM. The reduction is noticeable and suggests that VPM plays a meaningful role in reducing pitch variability.

Post- hoc tests (Bonferroni-corrected) confirmed significant group differences (p < 0.001), with Cohen’s d ranging from 0.92 to 3.21 across sessions (Table 5). Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), indicating that the assumption of equal variances of the differences between sessions was violated, expected in music performance data over multiple sessions (as shown in Table 4). Since sphericity was violated, Greenhouse-Geisser corrected degrees of freedom were applied to the F-tests for within-subject effects. Even after correction, all effects remained highly significant, affirming the reliability of the findings.

Theme 3: transition to independence

As sessions progressed, both teachers and students reported noticeable shifts towards independent pitch internalization. A teacher observed:

“Now they self-correct by humming the reference pitch before singing exactly what we aim to teach.“(Teacher 3, Final Evaluation).

By the end of the training period, both teacher observations and quantitative data indicated a clear transition toward learner independence in pitch regulation. In the final assessment, 76% of participants maintained accurate pitch without VPM assistance, demonstrating successful internalization of pitch control. This was supported by a significant reduction in teacher-reported correction needs, which decreased from 4.37 ± 0.6 pre-intervention to 1.61 ± 0.4 post-intervention (p < 0.001). These findings aligned with qualitative feedback, where learners described developing self-correction strategies, such as humming a reference pitch before singing. The convergence of quantitative outcomes and participant reflections underscores the pedagogical value of incorporating visual feedback tools to foster autonomous, confident musicians within Carnatic music pedagogy.

Theme integration: scaffolding process

The overall progression observed in this study followed a clear scaffolding process, gradually reducing learner reliance on external aids as internal pitch regulation skills developed. In the Figure (Figure 8), Dependent Phase (Weeks 1–4), participants heavily relied on the Visual Pitch Meter (VPM) for real-time feedback. During this period, the highest mean pitch deviations were recorded, and learners frequently required visual confirmation to adjust their pitch, as reflected in higher correction scores from teachers.

Moving into the Transitional Phase (Weeks 5–6), participants began to internalize the feedback patterns. Instead of continuous dependence on the VPM, learners intermittently checked their alignment and increasingly attempted self-correction before consulting the visual aid. Adaptive scaffolding principles shaped the feedback framework within the VPM, progressively transitioning learners from dependence on visual cues to autonomous pitch regulation, consistent with technology-enhanced music learning studies2. This period marked a noticeable reduction in pitch deviation, with averages steadily declining across sessions, indicating growing confidence and skill autonomy. By the Independent Phase (Weeks 7–8), most participants demonstrated the ability to regulate pitch without constant visual feedback.

Both qualitative teacher observations and quantitative data supported this shift: pitch deviations fell below 1.5 Hz on average, and 76% of participants maintained accuracy during final assessments without the VPM (as shown in Fig. 9). The decreasing reliance on teacher intervention and technology confirmed that the scaffolding strategy effectively fostered independent pitch internalization, aligning with principles of.

constructivist learning and Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. This structured, phased approach allowed learners to gradually move from guided practice to self-regulated performance, achieving both technical precision and musical confidence.

Discussion

This research demonstrates that the Visual Pitch Meter (VPM) tool effectively aids novice learners in internalizing shruti by reducing pitch deviation and encouraging musical independence. These findings are in line with constructivist theories where constructive, progressive skill development, is proficiently guided by feedback at various levels23. Within Vygotsky’s theories on the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), the VPM operated as a teaching aid that enabled learners to progressively autonomously refine their pitch as guided support dwindled33. As learners acquired the ability to visually self-monitor their performance, the dynamic of teacher and student influence in shared responsibility shifted, as described in the Responsibility Alignment Framework for Learning Dynamics (RALD)3.

Students’ self-efficacy increased significantly as a result of immediate visual reinforcement, according to the qualitative theme ‘Empowerment through Visual Feedback.’ This is further supported by the theme ‘Transition to Independence,’ as 76% of students maintained pitch accuracy without the VPM, indicating significant internalisation. The tool’s adherence to cognitive load principles26, which reduced unnecessary processing and freed up learners to concentrate on pitch refinement2, may be partially responsible for these results.

While these findings are promising, they need to be placed alongside prior studies conducted within Western vocal pedagogy, which emphasizes the benefits of vocal control and pitch training with the aid of real-time visual feedback instruments15,27. Compared to Western vocal training, which often fixes pitch centering within rigid tonal frameworks, the Carnatic pedagogy emphasizes flowing microtonal expressivity. An enhancement of the VPM to visualize gamaka movements as dynamic trajectories, instead of static pitch targets, is one possible blended adaptation to the VPM and gamaka which stands out from both pedagogical approaches. As much as the current design gives basic feedback to aid pitch stabilization, later versions of the algorithm will aim to provide near real-time feedback responsive to phrasing employing microtonal oscillations that are characteristic of expressive enhancement to Carnatic vocal phrasing.

Whereas more recent computational work by Plaja-Roglans et al. (2023) centrally points to the lack of high-quality, annotated vocal pitch data and the computational cost of producing such data as key obstacles to melodic analysis progress (especially for microtonally intricate Carnatic music), existing solutions are still mostly limited to offline research-oriented approaches, inhibiting scalable development. This deficiency is directly addressed in our research through the introduction of a Carnatic-specific Visual Pitch Meter (VPM) as an integrated pedagogical tool. The VPM differs from existing systems in that it creates dense, contextually labeled pitch data in real-time during scaffolded student practice (e.g., Sarali Varisais, Raga-specific phrases), automatically associating performance with focussing on shruti perfection which in turn will enhance the precision of every single note sung resulting in producing accurate data. This turns data collection from a computationally intensive research task into an effective by-product of learning, averting the computational bottleneck. In addition, by presenting real-time, objective measures of accuracy and fluency for these predetermined Carnatic shruti frequencies in practice, the VPM provides fundamental quantitative standards necessary for establishing and proving future standardized assessment criteria for melodic pattern discovery, thus filling an essential gap between music information retrieval (MIR) research and applied pedagogy.

Carnatic music is often defined by shruti bhedam and gamaka, showcasing its microtonal elements. This research seeks to enrich the largely uncharted intersection of visual feedback and Carnatic music education by employing visual feedback systems to a 12-interval octave framework infused with microtonal elements11. By doing this, it provides a culturally sensitive model for precision training and closes a significant gap between technological innovation and conventional pedagogy. The VPM complements Carnatic music’s oral tradition by enhancing, not replacing, the guru–shishya dynamic. Here the student listens to the guru’s rendition and, while practicing in the absence of the guru, seeks the VPM’s assistance to refine pitch and enhance precision with the tool’s feedback. As learners gain autonomy, teachers adopt facilitative roles, aligning with RALD’s distributed responsibility model and multi-sensory pedagogies that integrate visual, auditory, and kinesthetic modes1,24.

Session differences in pitch stability suggest additional factors such as practice consistency and learner motivation warrant deeper investigation28. With real-time pitch deviation tracking, the VPM mitigated subjectivity in a teacher’s evaluation and improved short-term pitch accuracy. However, its impact on the preservation of the aural heritage of Carnatic music requires further investigation28. With greater participant involvement, qualitative findings reinforced through thematic analysis could include semi-structured interviews concerning learner and teacher perceptions4. The VPM elaborates on the Sustainable Development Goals, specifically SDG 11, by supporting sustainable urban development through education, granting democratized access to precise IV training, mitigating improvisational heritage loss, and steering equitable musical growth within policy frameworks for intangible cultural heritages30. It also enhances scalability and aligns with international shifts in music education technology.

Limitations of the study

This study recognizes three primary limitations. To begin with, age of the learner (7–14 years) was not treated as a covariate. This range includes typical cohorts of novice learners in a Carnatic setting. However, the age range (7–14) slightly reduces the VPM’s effectiveness due to the aging neurodevelopmental processes of learning in the environment (for example, maturation of hearing for discrimination of certain tones). Nonetheless, the random assignment within the purposive sample helps to mitigate age-associated bias, and planned stratified random assignment by age subgroups in future studies will improve this. The second limitation is masked by the measurement of environment-parents with musical backgrounds, the imputed acoustics of the space, and the regularity of practice at home, may skew the results for the subjects who are in suboptimal conditions. While the VPM supports stable pitch acquisition, the current design does not accurately capture intricate microtonal oscillations of gamakas which are vital in Carnatic music (the tool is currently in the early phase of capture the granular microtonal oscillations which requires sophisticated feedback mechanisms based on precise algorithms and advanced mechanisms of responding to the requested criteria). The primary focus for this development is to enhance responsiveness to dynamic multi-order pitch movements in order to incorporate expressivity specific to the Carnatic tradition. Notably, the use of a purposively sampled homogeneous cohort allowed for precise isolation of VPM’s impact on foundational pitch skills, laying the groundwork for more nuanced iterations. Although pitch deviation improvements were observed over eight weeks, this duration may be insufficient to claim sustained internalization of shruti control. A longitudinal follow-up is recommended to assess retention.

Conclusion

Research contributions

This study provides compelling evidence for the pedagogical value of integrating a Visual Pitch Meter (VPM) into Carnatic music instruction. The tool significantly enhanced pitch precision, reducing deviation from ± 7.0 Hz to ± 1.14 Hz, and improved teacher-rated accuracy (2.30 to 4.28), correction required (4.37 to 1.61), and learner self-efficacy (2.2 to 4.5), all with p < 0.001. A Cohen’s d of 0.54 and an absolute reduction of 0.87 units affirm the moderate yet meaningful impact of the VPM. Rooted in Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development33 and constructivist learning theory9,23, the VPM acted as a scaffold, promoting autonomy and reducing reliance on teacher correction. It complements oral tradition by fostering learner independence and precision, marking a significant step toward hybridized, culturally sensitive music pedagogy. This research’s major contribution is the demonstration that real-time color-coded visual feedback has a significant effect on young Carnatic music learners’ comprehension and internalization of shruti (pitch) and facilitates measurable musical development. Most importantly, the usefulness of the tool is not limited to beginners; even experts who are seeking 100% pitch accuracy can practice with this to fine tune if there are any mild fluctuations. Finally, this research sets up a successful model for building pitch sense foundations – a cardinal aspect of all music cultures, and particularly of Carnatic music, where Sruthi is the fundamental reservoir (“the mother”) of melody.

Educational and methodological implications

The findings support a hybrid pedagogical model that blends traditional mentorship with multi-sensory, feedback-driven learning environments. Visual feedback tools like the VPM align with broader trends in music education7,34, where trained musicians demonstrate superior pitch alignment and enhanced auditory processing, such as reduced latency and increased amplitudes in cortical auditory evoked potentials8. These benefits extend to audiovisual integration, with musicians showing greater sensitivity to multi-sensory correspondences than non-musicians7, suggesting that tools like the VPM may leverage these neural pathways for more efficient pitch internalization.

Methodologically, this study demonstrates the value of combining quantitative metrics with theoretical grounding to assess both technical proficiency and learner development. It also highlights the importance of designing scalable, culturally embedded tools that preserve the integrity of oral pedagogy28 while enhancing accessibility and adaptability. In doing so, the research aligns with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, Goal 4 (Quality Education), Goal 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), and Goal 11 (Sustainable Communities), by promoting inclusive, innovative, and heritage-conscious learning environments30.

Future research scope

There are four major priorities: First, using gamaka reproduction tasks without the use of technology, longitudinal studies (6–12 months post-intervention) should monitor the preservation of pitch autonomy and potential decline of aural attentiveness5. Second, to avoid tool dependency while maintaining skill retention, scaffolding withdrawal protocols (such as switching from continuous to intermittent VPM feedback) need to be tested in the long run26. Third, real-time visualisation for Carnatic-specific parameters, such as gamaka trajectories, general aspects of Carnatic pedagogy, voice modulation, notation system and raga-based shruti boundaries, should be incorporated into culturally sensitive VPM expansions32. Fourth, equity-driven designs promote Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education) by requiring low-cost, offline VPM iterations for underserved communities. When taken as a whole, these approaches reinterpret constraints as opportunities for innovation, guaranteeing that technology preserves the embodied legacy of Carnatic music without simplifying it.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to participant confidentiality and institutional ethics guidelines. Anonymized data may be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request : keyboardmaya@gmail.com.

Change history

21 November 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article P Uma Maheswari was incorrectly affiliated with affiliation 2. The correct affiliation is: Department of Media Sciences, Anna University, Chennai, 600025, India. The original Article has been corrected.

Abbreviations

- VPM:

-

Visual Pitch Meter

- RALD:

-

Responsibility Alignment Framework for Learning Dynamics

- ZPD:

-

Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

References

Astuti, K. S., Sudiana, I. N., Redhana, I. W. & Suryadarma, I. G. P. Effectiveness of imitation, creation, and origination focus learning by using encore software. Int. J. Instruction. *15* (2), 751–774 (2022). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1341675.pdf

Banut, M. & Albulescu, I. Technology-enhanced thinking scaffolding in musical education. J. Effi. Responsib. Educ. Sci. *17* (4), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.7160/eriesj.2024.170401 (2024).

Boud, D. Using peer learning to increase student responsibility for learning. In (eds Boud, D., Cohen, R. & Sampson, J.) Peer Learning in Higher Education: Learning from and with Each Other (49–60). Kogan Page. (2001).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res. Psychol. *3* (2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa (2006).

Creswell, J. W. & Plano Clark, V. L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research 3rd edn (Sage, 2018).

Ganguli, K. K. & Rao, P. On the distributional representation of ragas: experiments with allied raga pairs. Trans. Int. Soc. Music Inform. Retr. *1* (1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.5334/tismir.11 (2018).

Henley, J. The impact of visual feedback on instrumental music learning: A review. J. Music Educ. Res. *20* (3), 45–60 (2018).

Ihalainen, R., Vivas, A. B. & Paraskevopoulos, E. The relationship between musical training and the processing of audiovisual correspondences: evidence from a reaction time task. PLOS ONE. (4), e0282691. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282691 (2023).

Jonassen, D. H. Designing constructivist learning environments. In (ed Reigeluth, C. M.) Instructional-design Theories and Models: A New Paradigm of Instructional Theory (Vol. 2, 215–239). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. (1999).

Kalyuga, S. Cognitive load theory: how many types of load does it really need? Educational Psychol. Rev. *23* (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9150-7 (2011).

Koduri, G. K., Serra, J. & Serra, X. Intonation analysis of ragas in carnatic music. J. New. Music Res. *43* (1), 72–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/09298215.2013.866145 (2014).

Krishnan, A. & Plack, C. J. Neural encoding in the human brainstem relevant to the pitch of complex tones. Hear. Res. *275* (1–2), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2010.12.008 (2011).

Krishnaswamy, A. Application of pitch tracking to South Indian classical music. Proc. IEEE ICASSP. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2003.1200030 (2003).

Krishnaswamy, A. Melodic atoms for transcribing carnatic music. Comput. Music J. 27 (3), 31–45 (2003). https://www.ee.columbia.edu/~dpwe/ismir2004/CRFILES/paper219.pdf

Lã, F. M. B. & Fiuza, M. B. Real-time visual feedback in singing pedagogy: Current trends and future directions. Applied Sciences, *12*(21), 10781. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/app122110781

Music Gurukul Online. The concept of shruti and laya in Carnatic classical music. Retrieved October 26, 2024, from (2023). https://musicgurukulonline.com/shruti-and-laya-in-carnatic-classical-music/

Plaja-Roglans, G., Nuttall, T., Pearson, L., Serra, X. & Miron, M. Repertoire-specific vocal pitch data generation for improved melodic analysis of carnatic music. Trans. Int. Soc. Music Inform. Retr. *6* (1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.5334/tismir.137 (2023).

Popescu, T., Widdess, R. & Rohrmeier, M. Western listeners detect boundary hierarchy in Indian music: A segmentation study. Scientific Reports, *11*, 2263. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82629-y

Renkl, A. & Atkinson, R. K. Structuring the transition from example study to problem solving in cognitive skill acquisition. Educational Psychol. *38* (1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3801_3 (2003).

Salamon, J., Gulati, S. & Serra, X. A multipitch approach to tonic identification in Indian classical music. Proceedings of the 13th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (pp. 121–126). (2012). https://ismir2012.ismir.net/event/papers/499-ismir-2012.pdf

Samaco, J. D. C. & Coronel, A. D. Towards absolute pitch training with wearable technology that incorporates tactile stimuli based on auditory-tactile simulated synesthesia. The Southeast Asian Conference on Education 2024. IAFOR. (2024). https://papers.iafor.org/wp-content/uploads/papers/seace2024/SEACE2024_75984.pdf?t=8

Schippers, H. (2010). Facing the music: Shaping music education from a global perspective.Oxford University Press. https://books.google.co.in/books?id=-yYzW0ujEsIC&lpg=PR7&ots=65Ftt1xngY&lr&pg=PR3#v=onepage&q&f=false

Scott, S. Integrating constructivist principles into music education. Music Educators J. *94* (5), 34–39. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.104672790564030 (2008). https://search.informit.org/doi/pdf/

Simones, L., Rodger, M. & Schroeder, F. Seeing how it sounds: Observation, imitation and improved learning in piano playing. Cognition Instruction. *35* (2), 125–140 (2017). https://pure.qub.ac.uk/files/111862841/Seeing_how_it_sounds_Latest_draft.pdf

Suhalka, S. Music education in the digital age: opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Res. Publication Reviews. *5* (6), 1361–1370 (2024). https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V5ISSUE6/IJRPR30487.pdf

Sweller, J. Cognitive load during problem solving. Cogn. Sci. 12 (2), 257–285. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4 (1988).

Teixeira, J. P. & Leão, I. R. Real-time visual feedback technology in support of a didactic voice tuning system. Proceedings of 2023 International Conference (pp. 471–481). Springer. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-5414-8_43

Tenzer, M. Technology and cultural preservation in music education. Ethnomusicology Forum. *28* (1), 3–25 (2019).

UNESCO. Education for sustainable development: A roadmap. (2020). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802

UNESCO. Culture for sustainable development: Policy guidance. (2023). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000387252

Vidwans, V. The doctrine of shruti in Indian music. FLAME University. (2016). https://www.indian-heritage.org/music/TheDoctrineofShrutiInIndianMusic-Dr.VinodVidwans.pdf

Viraraghavan, V. S., Pal, A., Aravind, R. & Murthy, H. A. Data-driven measurement of precision of components of pitch curves in carnatic music. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 147 (5), 3657–3666. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0001313 (2020).

Vygotsky, L. S. Mind in Society: the Development of Higher Psychological Processes (Harvard University Press, 1978).

Welch, G. F. We are musical: the role of real-time visual feedback in vocal pedagogy. Int. J. Music Educ. *23* (2), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761405052404 (2005).

Wiggins, J. Teaching for Musical Understanding 3rd edn (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participating teachers and students for their time, commitment, and valuable insights throughout the study. We would also like to thank the experts and musicians for providing timely guidance and valuable insights for the study.

Funding

This work did not receive any external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author 1 : Srivaralaxmi V - Conceptualising, methodology, editing, framework, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing and original draft preparation Author 2 : Dr Uma Maheswari P - Methodology, review, validation, framework analysis and formal data analysis Author 3 : M K Chandrasekar : Resources, conceptualisation, curation, review and software.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Doctoral Research Committee, Anna University.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Srivaralaxmi, V., Uma Maheswari, P. & Chandrasekar , M.K. Evaluating the role of a visual pitch meter in carnatic music education and pitch internalization through constructivist and RALD frameworks. Sci Rep 15, 38251 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21998-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21998-0