Abstract

Based on the coupled thermoelasticity theory, this study presents a stochastic analysis of opto-acoustic wave propagation in non-local semiconductor media subjected to magneto-photo-thermal effects. The model incorporates magnetic field influence and non-local elasticity to capture realistic semiconductor behavior. Stochastic thermal fluctuations are introduced through a Wiener process, enabling a probabilistic framework to assess uncertainty in the system response. The governing equations are solved analytically, yielding explicit expressions for the main physical fields, including displacements, stresses, temperature, acoustic pressure, carrier density, and strain. To examine the influence of physical parameters, the effects of the non-local parameter and magnetic field intensity are systematically investigated. In addition, stochastic envelope estimation is conducted using 30 and 500 realizations to evaluate the statistical behavior of physical responses. Results demonstrate that increasing the number of realizations significantly reduces noise and sharpens the approximation of the mean solution. Finally, a heat map is generated for the 500-realization case to visualize the system’s spatial distribution and intensity of uncertainty. This work provides valuable insights into the dynamics of semiconductor media under combined magneto-photo-thermal and stochastic excitation, emphasizing acoustic pressure behavior and its interaction with non-local and magnetic effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Semiconductors are central to optoelectronic, photovoltaic, and sensing technologies because of their coupled electrical, thermal, and mechanical behavior. Alzahrani and Abbas1 examined photo-thermo-elastic interactions without dissipation, while Mondal and Sur2 and Kumar et al.3 investigated wave propagation and photo-thermal excitation under dual-phase-lag theory with nonlocal effects. Fractional-order and non-local formulations have been developed by Hobiny and Abbas4, Geetanjali et al.5, and Sherief and Abd El-Latief6. Abouelregal and colleagues7,8,9,10,11,12 contributed through MGT and fractional models, while Chandel et al.13,14,15 and Bhattacharya and Kanoria16,17 studied thermo-diffusive responses with memory effects. Further contributions extended these models to viscoelastic beams18,19 and biomechanical tissues20,21.

The coupling between magnetic fields and thermoelastic responses has attracted significant attention. Deswal et al.22 analyzed Hall currents and photothermal effects in magneto-thermoelastic media with diffusion and gravity. Salah et al.23 studied diffusion in semiconductors under hyperbolic two-temperature photothermal waves, while Sur24 examined magneto-photo-thermoelastic interactions in strips with hereditary features. Extending this line of work, Salah et al.25 investigated ramp-type heating and initial stresses in rotating photothermal semiconductors. Yadav26 modeled plasma waves using two-temperature theory with multiphase-lag thermoelasticity, and Jatain et al.27 considered micropolar continua with photothermal coupling. Khalil et al.28 addressed void-containing semiconductors under electromagnetic fields, and Rashid et al.29 studied the combined effects of rotation, magnetic fields, and internal heat sources. Bhattacharya and Kanoria30,31 extended these investigations to magneto-thermoelastic diffusion and ramp heating of biological tissues. Makkad et al.32,33,34 further explored thermo-viscoelastic vibrations in microplate resonators, thermomass dynamics in nanorods, and cylindrical cavities under three-phase-lag diffusion. Together, these studies underline the destabilizing role of magnetic fields and the significance of Multiphysics coupling in semiconductor thermoelasticity.

Stochastic and photoacoustic frameworks provide additional insight into randomness, fluctuations, and advanced detection. Wang et al.35, Brueck et al.36, and Lang et al.37 developed measurement and detection methods for photothermal and photoacoustic effects. McCullough38, Wang et al.39, Breunig and Jones40, Shiraishi41, Lin42, Jazwinski43, and Brémaud44 contributed statistical, filtering, and Fourier-based approaches to characterize random processes. Burgholzer et al.45 advanced acoustic reconstruction techniques, Tian et al.46 demonstrated coherent thermoacoustic wave generation in graphene, Liu et al.47 examined nanoscale photoacoustic responses via laser Doppler vibrometry, Zobeiri et al.48 analyzed phonon nonequilibrium in graphene, and Li et al.49 modeled thermoacoustic effects in multilayer composites. The novelty of this work lies in integrating Monte Carlo simulation with photo-thermoelastic modelling. By generating random samples and estimating system envelopes, we capture stochastic variability in thermal and mechanical fields. In addition, this study extends the stochastic framework to analyze acoustic pressure responses, showing how randomness influences wave propagation in semiconductors. This dual focus—on both field variables and acoustic pressure—provides a more comprehensive description of semiconductor behavior under uncertainty, enhances predictive accuracy, and demonstrates how stochastic envelope estimation can make the model more realistic and effective for practical applications.

Basic equation and model assumptions

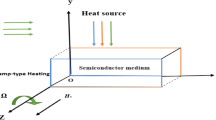

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model of the present study, where a two-dimensional, homogeneous, and isotropic silicon medium is subjected to photo-acoustic excitation. The medium is exposed to an external light source, initiating interactions that generate heat and acoustic pressure within the non-local semiconductor. This excitation induces non-uniform distributions in temperature, carrier density, and mechanical displacement fields. Additionally, a constant magnetic field is applied in the \(z\)-direction, perpendicular to the \(x - y\) plane, introducing Lorentz force effects into the system’s dynamic response. The silicon material is homogeneous, implying spatial uniformity of properties such as density \(\rho\), thermal conductivity \(k\), specific heat capacity \(C_{e}\), and \(\lambda ,\mu\) elastic moduli. It is also isotropic, meaning its mechanical and thermal characteristics are identical in all directions. The mathematical formulation involves coupled equations governing the temperature field \(T(x,y,t)\), carrier density \(N(x,y,t)\), acoustic pressure \(P(x,y,t)\), and displacements \(u(x,y,t)\) and \(v(x,y,t)\) in the \(x -\) and \(y -\) directions, respectively, under the influence of non-local photo-acoustic excitation and magnetic field interactions.

Following the theoretical framework of Alzahrani and Abbas1 and further extended through fractional-order formulations by Hobiny and Abbas4, the constitutive stress relation for the photo-magneto-thermoelastic semiconductor medium can be expressed as:

Here, \(\sigma_{ij}\) denotes the stress tensor component, while \(\mu = \frac{E}{2(1 + \nu )}\) and \(\lambda = \frac{E\nu }{{(1 + \nu )(1 - 2\nu )}},\) are Lamé’s constants representing the elastic moduli of the material, \(E\) is the Young’s modulus, which measures the stiffness of a material (ratio of stress to strain in uniaxial loading), \(\nu\) represents Poisson’s ratio, which represents the negative ratio of transverse strain to axial strain under uniaxial stress. The terms \(u_{i,j}\) and \(u_{j,i}\) represent the displacement component and its spatial derivative, respectively, and \(u_{k,k}\) corresponds to the dilatational strain. The symbol δij\delta_{ij}δij is the Kronecker delta. The parameter \(\gamma_{T} \, = (3\lambda + 2\mu )\alpha_{t}\) corresponds to the thermal expansion effect, with \(\alpha_{t}\) being the linear thermal expansion coefficient, while \(\gamma_{N} = (3\lambda + 2\mu )d_{n}\) represents the electronic deformation coefficient with \(d_{n}\) denoting the electronic deformation parameter. In addition, \(T\) is the absolute temperature and \(N\) is the carrier density. This relation reflects the essential coupling among mechanical, thermal, and semiconductor effects, where thermal expansion and carrier diffusion introduce additional stresses in the material. This equation is derived from within the framework of generalized thermoelasticity and has been adopted in previous studies addressing photo thermoelastic interactions in semiconductor media under thermal and optical excitation. For clarity, the explicit tensor components take the form:

This expanded form highlights how the thermoelastic \(- \gamma_{T} T\) and carrier \(- \gamma_{N} N\) effects contribute directly to the normal stress components, while the shear stress depends only on the displacement gradients. In nonlocal elasticity and thermo-elasticity, the nonlocal operator is typically expressed as a convolution between a kernel function \(\alpha \left( {\left| {x - x^{\prime } } \right|} \right)\) and the local field variable. For a scalar displacement field \(u(x)\), the nonlocal stress or operator can be written as50:

where \(\alpha \left( {\left| {x - x^{\prime } } \right|} \right)\) is the attenuation kernel, describing the influence of a point \(x^{\prime }\) on the field at \(x\), \(\Omega\) is the material domain, and \(\int_{\Omega } \alpha \left( {|x - x^{\prime } |} \right)dx^{\prime } = 1\) for normalization. For simplification in many thermoelastic models, this operator is reduced to an equivalent differential form:

As demonstrated in the nonlocal thermoelastic formulations of Sherief and Abd El-Latief6 and further extended to cylindrical and nanostructure problems by Abouelregal11,12, the equation of motion for a non-local photo-thermoelastic semiconductor medium can be expressed as:

where \(\rho\) represents the mass density of the material. In this formulation, the perfector \(\left( {1 - \xi_{1}^{2} \nabla^{2} } \right)\) modifies the classical inertial term to incorporate non-local effects, where \(\xi_{1}\) is the characteristic nonlocality length scale. This form of the motion equation captures the complex interplay between mechanical deformations, temperature gradients, carrier diffusion, and external forces \(F_{i}\) within the framework of generalized thermoelasticity. Such formulations have been widely adopted in recent studies on magneto-photo-thermoelastic behavior in semiconductors. Building on the carrier transport formulations for semiconductors with diffusion and photothermal coupling developed by Salah et al.23 and further extended to micropolar continua with thermodynamical interactions by Jatain et al.27, the carrier density \(N(x,y,t)\) evolution in semiconductors is generally described by a transport equation incorporating diffusion, recombination, temperature-induced generation, and drift due to electric fields. The generalized form is given by

where \(D_{e} \nabla^{2} N\) accounts for carrier diffusion, \(- \frac{N}{\tau }\) represents recombination, \(\kappa T\) corresponds to thermal generation, and the term \(\mu_{e} \nabla \cdot (N\text{E})\) models drift under the action of the electric field \(\text{E}\), \(\mu_{e}\) denotes the carrier mobility. To close the model, boundary conditions on carrier flux are usually prescribed, such as vanishing carrier density at infinity. In this study, the drift contribution is neglected under the assumption of weak external fields and dominant thermoelastic–photothermal effects. Thus, the governing relation reduces to

\(D_{E}\) is the diffusion coefficient for carriers, \(\tau\) denotes the average lifetime of generated carriers under external influence. The parameter \(\kappa\) is the thermal activation coefficient linking temperature to carrier generation, defined as \(\kappa = \frac{{\partial N_{0} }}{\partial T}\frac{1}{\tau }\), with \(N_{0}\) being the carrier concentration under thermal equilibrium. The temperature field \(T\) couples this equation with the thermal and mechanical fields, highlighting the photo-thermoelectric interaction. This formulation is essential in modelling the behavior of photoexcited carriers in non-local semiconductor media, particularly under external thermal and optical perturbations. Within the framework of generalized coupled thermo-elasticity, as extended to hyperbolic two-temperature photothermal waves by Salah et al.23 and further developed through nonlocal fractional heat transfer models by Abouelregal et al.12, the governing equation for the temperature field \(T(x,y,t)\) in the semiconductor medium is expressed as:

where \(C_{e}\) is the specific heat measured under constant strain, \(E_{g}\) represents bandgap energy of the material, \(e\) is the dilatational strain (or volumetric strain), and \(T_{0}\) is the standard reference temperature where the deviation is assumed negligible. The mechanical-thermal coupling is introduced through the term \(\gamma_{T} T_{0} u_{k,kt}\), which reflects the heat generated due to volumetric strain rate, emphasizing the bidirectional interaction between elastic deformation and temperature variation. This formulation captures essential physical mechanisms such as photo-induced heating, thermally driven deformation, and their feedback loop in semiconductors, as discussed in previous studies on opto-thermoelastic coupling. Following the classical formulations of photoacoustic wave propagation presented by Wang et al.35 and further refined through detection approaches by Brueck et al.36 and Lang et al.37, the governing equation for the acoustic pressure \(P(x,y,t)\) in the semiconductor medium, accounting for temperature variations, is written as:

where \(C_{r}\) is the material’s adiabatic index, \(C_{s}\) is the thermomechanical wave speed in the material, and \(\beta\) is the material’s bulk thermal expansion parameter. This equation highlights the coupling between the thermal field and the resulting acoustic waves, an essential feature in optoacoustic and photothermal modeling. It models the photoacoustic wave propagation initiated by laser-induced thermal excitation in semiconductors.

The influence of the magnetic field

Consideering the magnetic field constant \(\user2{H = H}_{{\varvec{0}}}\)

In the present model, the influence of electromagnetic fields on the semiconductor medium is incorporated by considering the directional behavior of the associated field vectors and velocity components. The magnetic field \(\vec{H}\) is assumed to be applied along the \(z - axis\), i.e., \(\vec{H} = (0,0,H_{0} )\), which is perpendicular to the plane of motion defined by the \(x - y\,\,axis\). The material’s motion is confined to this plane, and the velocity vector is described by \(\vec{u} = (u,v,0)\). The electric current density vector \(\vec{J}\) is defined as \(\vec{J} = (J_{x} ,J_{y} ,J_{z} )\), where all components are potentially affected by the induced electromagnetic interactions due to photo-excitation and mechanical coupling. Under these assumptions, the electromagnetic behavior of the medium is governed by Maxwell’s equations, which describe the interaction between the electric field \(\vec{E}\), the magnetic perturbation field \(\vec{h}\), and the velocity of the material22,28,29:

Maxwell’s stress tensor \(\tau_{ij}\) is essential in quantifying the stress induced in a medium due to a magnetic field. It is expressed as:

This tensor describes how the magnetic field exerts magnetic body forces on the material, contributing to its internal stress state. These forces are especially relevant in conducting or semiconducting media. \(H_{k} h_{k} \delta_{ij}\) ensures isotropy without directional magnetic anisotropy. To assess the electromagnetic influence on the semiconductor medium, we begin by incorporating the directional assumptions for the induced electric field \(\vec{E}\), magnetic perturbation \(\vec{h}\), and current density \(\vec{J}\). Based on the background magnetic field \(\vec{H} = (0,0,H_{0} )\) oriented along the \(z - axis\) and the mechanical velocity field \(\vec{u} = (u,v,0)\), the field expressions are obtained as:

These relations are derived by applying Maxwell’s equations under the slowly moving media assumption, where the electromagnetic fields are influenced by both material deformation and charge transport phenomena. Subsequently, the Lorentz force per unit volume exerted by the electromagnetic fields is evaluated using the classical expression:

The expansion of \((\vec{J} \times \vec{H})\) can be determined as:

Substitute \(\vec{J}_{x} ,\vec{J}_{y}\) from (11):

Multiply by \(\mu_{0}\) and substitute with (15) into (13) the electromagnetic force vector \(\vec{F}\) can be expressed, consistent with magneto-thermoelastic formulations under electromagnetic interactions in semiconductors22,23,28,29:

This Lorentz force formulation provides a fundamental mechanism for coupling semiconductors’ electromagnetic and thermoelastic fields, especially under photo-excitation and external magnetic bias, as demonstrated in prior studies. Thermal and carrier fields influence mechanical motion, and the Lorentz force results from electromagnetic effects.

Considering the magnetic field varying with time

If the background field is considered time-varying, i.e., \(\vec{H} = \vec{H}(t)\), Maxwell’s equations take the more general forms:

where additional induced electric field and displacement current terms appear. Consequently, the Lorentz force becomes:

with \(\vec{J}\) now modified by both the temporal derivative of \(\vec{H} = \vec{H}(t)\) and displacement currents. This introduces stronger coupling between the electromagnetic, thermal, and elastic subsystems, potentially leading to modified wave dispersion, resonance phenomena, and enhanced absorption. Therefore, assuming a constant background field provides a tractable framework that isolates the essential coupling mechanisms, while the time-varying field case introduces additional induced terms that represent an important direction for future studies. Thermal gradients affect Carrier generation and diffusion, while temperature evolution is driven by heat conduction, carrier recombination, and deformation-induced heat sources. Additionally, acoustic pressure propagation is thermally coupled with temperature changes. Following earlier formulations in generalized thermoelasticity and photoacoustic theory, as presented by Alzahrani and Abbas1, extended through nonlocal photo-thermal excitation frameworks by Kumar et al.3, and further supported by photoacoustic investigations of Wang et al.35 and Brueck et al.36, the system of equations in two spatial dimensions is given by:

In line with the generalized constitutive stress relations for thermoelastic semiconductors, as established by Alzahrani and Abbas1, further extended through fractional-order formulations by Hobiny and Abbas4, and applied in nonlocal cylindrical media by Abouelregal11, the stress components in two dimensions are expressed as:

Dimensionalization and mathematical formulation

To facilitate the mathematical treatment of the two-dimensional displacement field \((u,v)\) in the \(x - y\) plane, two scalar potential functions \(\Pi (x,y,t)\) and \(\Psi (x,y,t)\) are introduced. Following approaches employed in photo-thermoelastic analyses by Mondal and Sur2 and Geetanjali et al.5, these potentials enable the displacement components to be expressed as:

This simplifies the governing equations by reducing the second-order vector partial differential equations system into a more manageable scalar form. A non-dimensionalization process is applied to the spatial coordinates, displacement fields, temperature, carrier density, and potential functions to simplify the analysis further and reduce the number of physical parameters. The dimensionless variables are defined by3,16:

This transformation transforms the coupled photo-thermoelastic system into a dimensionless framework, reducing complexity and exposing the relative influence of key physical parameters such as thermal expansion, carrier diffusion, and mechanical moduli. After applying the non-dimensionalization transformations to the physical system, the governing equations describing the coupled fields displacement potential \(\Pi\), transverse displacement potential \(\Psi\), carrier density \(N\), temperature \(T\), and acoustic pressure \(P\) reduce to the following dimensionless form:

To describe the internal forces within the medium under the influence of photo-thermoelastic coupling, the dimensionless stress components \(\sigma_{xx}\), \(\sigma_{yy}\), and \(\sigma_{xy}\) are expressed in terms of the displacement potential functions \(\Pi\) and \(\Psi\), as well as the thermal and carrier fields \(T\) and \(N\).

where

\(\beta _{1} = 2\mu + \lambda ,\;R_{h} = 1 + \frac{{\epsilon _{0} \mu _{0}^{2} H_{0}^{2} }}{\rho },\;\beta _{3} = 2\mu + \lambda + \mu _{0} H_{0}^{2} ,a_{1} = \frac{{2\mu + \lambda }}{\mu },\;a_{5} = \frac{k}{{\rho C_{e} D_{E} }},\;a_{6} = \frac{{t^{*} k}}{{\tau \rho C_{e} D_{E} }},\;\)\(a_{7} = \frac{{\kappa t^{*} k\gamma _{N} }}{{\rho C_{e} D_{E} \gamma _{T} }},\;a_{8} = \frac{{E_{g} {\mkern 1mu} t^{*} {\mkern 1mu} \gamma _{T} }}{{\rho C_{e} \tau \gamma _{N} }},\;a_{9} = \frac{{\gamma _{T}^{2} T_{0} {\mkern 1mu} t^{*} }}{{\rho k}},\;a_{{10}} = \frac{{C_{T}^{2} }}{{C_{s}^{2} }},\;a_{{11}} = \frac{{C_{T}^{2} {\mkern 1mu} C_{r} {\mkern 1mu} \beta (2\mu + \lambda )}}{{P_{0} \gamma _{T} }},a_{2} = \frac{\lambda }{\mu }\) Several critical dimensionless parameters govern the material properties and coupling interactions among the thermal, mechanical, and carrier fields within the non-dimensional framework.

-

\(\beta_{1}\) is the longitudinal elastic modulus, related to the Lamé constants \(\mu\) and \(\lambda\).

-

\(R_{h}\) is the dimensionless electromagnetic stiffness, determined by permittivity \(\varepsilon_{0}\), permeability \(\mu_{0}\), and magnetic field \(H_{0}\).

-

\(\beta_{3}\) is the total coupling parameter, accounting for both elastic and magnetic stiffness.

-

\(a_{1}\) is the ratio of bulk to shear modulus, defining anisotropic elastic behavior.

-

\(a_{5}\) the thermal diffusivity coefficient combines thermal conductivity, density, and specific heat.

-

\(a_{6}\) is the dimensionless recombination-loss factor for carriers via heat.

-

\(a_{7}\) is the thermo-carrier coupling coefficient, describing heat interaction with carrier density.

-

\(a_{8}\) is the heat generation parameter, associated with energy released by carrier recombination.

-

\(a_{9}\) is the photo-thermoelastic coupling coefficient, linking temperature to elastic strain rate.

-

\(a_{10}\) is the normalized wave speed squared, comparing fiber wave speed \(C_{T}\) to acoustic speed \(C_{s}\).

-

\(a_{11}\) is the acoustic–thermal coupling term, quantifying the influence of pressure on temperature through elasticity.

Analytical representation of the normal mode method

The normal mode method is applied to obtain analytical insight into the system by assuming exponential solutions for the field variables, a technique widely used in wave propagation and stability analysis of thermoelastic media2,16. Specifically, each dependent variable (temperature \(T\), carrier density \(N\), displacement potentials \(\Pi\), \(\Psi\), and acoustic pressure \(P\)) is expressed in the form:

Here, \(\omega\) is the complex circular frequency and \(b\) is the wave number in the \(y - direction\). The resulting system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) presented in Eqs. (38–42) allows for a thorough analysis of wave behavior, stability characteristics, and the effects of thermoelastic, photoacoustic, and semiconductor coupling mechanisms. In the application of the normal mode method, all field variables are expressed in exponential form \((T,N,\Pi ,\Psi ,P) \sim e^{\omega t + iby}\), consistent with earlier formulations for wave propagation in generalized thermoelasticity2,16. This choice is standard in stability analysis of linear systems because exponential functions represent harmonic modes that naturally arise as solutions of linear PDEs with constant coefficients. Mathematically, this assumption reduces the governing equations to an algebraic eigenvalue problem, enabling the derivation of dispersion relations. Physically, the exponential form captures both oscillatory and decaying/growing behavior, with the real part of \(\omega\) associated with wave propagation and resonance, while the imaginary part indicates the stability of the system. Thus, adopting exponential modes not only facilitates the derivation of closed-form solutions but also provides direct insight into the stability and resonance characteristics of the coupled photo–acoustic–thermoelastic medium.

The stress components obtained by applying the normal mode method can be reformulated using the amplitude functions. These stress expressions, corresponding to the transformed fields, are detailed below:

where \(\alpha_{1} = \frac{{\beta_{1} }}{{\beta_{4} }}\), \(E_{1} = b^{2} + \alpha_{1} \omega^{2} R_{h}\), \(E_{2} = b^{2} + \frac{{a_{1} \omega^{2} R_{h} }}{{1 + a_{1} \xi_{1}^{2} \omega^{2} }}\), \(E_{3} = b^{2} + a_{5} \omega + a_{6}\), \(E_{4} = b^{2} + \omega ,\)\(E_{5} = a_{9} \omega\)\(\alpha_{2} = E_{4} + E_{5} \alpha_{1}\), \(\alpha_{3} = a_{8} + E_{5} \alpha_{1}\), \(\alpha_{4} = E_{5} \omega^{2} \alpha_{1} R_{h}\), \(E_{7} = b^{2} + a_{10} \omega^{2}\),\(E_{8} = a_{11} \omega^{2} ,E_{6} = \sqrt {E_{2} }\).

Matrix differential equation formulation and solution

The matrix differential equation technique offers an efficient and systematic approach to solve the system of governing Eqs. (38–42). By reformulating the coupled partial differential equations into a first-order vector–matrix system, one can leverage linear algebra tools such as eigenvalue and eigenvector analysis to gain insight into the stability and dynamic behavior of the physical system16,30.

where the state vector \(\vec{V}\) and the coefficient matrix \(A\) can be defined as:

where

\(B_{51} = \alpha_{2} ,B_{52} = - \alpha_{3} ,B_{53} = - \alpha_{4} ,B_{54} = 0,B_{61} = - a_{7} ,B_{62} = E_{3} ,B_{63} = 0,B_{64} = 0,B_{71} = B_{72} = \alpha_{1} ,\) \(B_{73} = E_{1} ,B_{74} = 0,B_{81} = E_{8} ,B_{82} = 0,B_{83} = 0,B_{84} = E_{7}\).

After formulating the coupled system in the vector–matrix differential form as shown in Eq. 46, the eigenvalue problem is addressed by solving the associated characteristic equation. This leads to the following algebraic equation for the eigenvalues \(\lambda\):

where

Equation (48) represents an eighth-order characteristic equation arising from the coupled system of differential equations. The nature of the roots of this equation depends on the physical parameters involved, particularly those related to thermoelastic and thermo-energy coupling, relaxation times, and thermal diffusivity. Under physically realistic parameter values (as adopted in the numerical simulations), the characteristic equation yields four distinct pairs of complex roots, reflecting the oscillatory-decaying nature of the solution modes. Out of these eight roots, only the four roots with negative real parts are retained, as they correspond to decaying modes that satisfy the boundary conditions and physical constraints (e.g., finite values at infinity or within a bounded domain). The remaining three roots with positive real parts are excluded because they lead to non-physical exponentially growing solutions. As a result, Eq. 51 includes only four exponential terms corresponding to the retained roots with decaying behavior. These modes capture the dominant physical response of the system without introducing instabilities or divergence, in line with the standard practice in normal mode and eigenvalue-based analyses for such problems. This choice ensures the physical plausibility and mathematical well-posedness of the solution, especially when modelling bounds physical systems or semi-infinite domains with absorbing conditions at the far boundary. The roots of the characteristic formula Eq. 48, which represent the eigenvalues, are:\(\lambda = \lambda_{1}\), \(\lambda = \lambda_{2}\), \(\lambda = \lambda_{3}\), \(\lambda = \lambda_{4}\), \(\lambda = \lambda_{5}\), \(\lambda = \lambda_{6}\), \(\lambda = \lambda_{7}\), \(\lambda = \lambda_{8}\). Conversely, the eigenvectors in this instance are represented by \(\vec{Q} = [q_{1} ,q_{2} ,q_{3} ,q_{4} ,q_{5} ,q_{6} ,q_{7} ,q_{8} ]^{T}\) corresponding to the eigenvalues \(\lambda_{j} (j = 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8)\), which can be given as:

Under these conditions, the vector solution can take the linear form as follows:

Utilizing the principle of superposition, the expressions for the physical variables can be represented in the following linear form:

On the other hand, since Eq. (39) governing \(\Psi^{*}\) is uncoupled and homogeneous, its solution takes the simpler form:

The displacements \(u^{ * } (x)\) and \(v^{ * } (x)\) are derived by substituting the potentials into their definitions. They are expressed using normal mode representation as:

Using the derived expressions for the displacement potentials, the stress components can be reformulated in terms of the amplitude functions and their corresponding derivatives as given below:

where

Boundary conditions

The boundary assumptions follow earlier treatments in photo-thermoelastic and magneto-thermoelastic semiconductors, where rigid boundaries, harmonic excitation, and vanishing conditions at infinity are applied for analytical tractability1,2,23. At the illuminated surface \(x = 0\), the medium is assumed rigid in both directions, preventing displacement, while the normal stress is subjected to harmonic optical excitation and the photoacoustic fields are modelled as harmonic in time. At \(x \to \infty\), all field variables vanish, ensuring stability and convergence. No additional effects such as radiation or partial absorption are considered, providing a simplified framework for coupled thermoelastic, acoustoelastic, and carrier dynamics.

-

i

Axial displacement constraint:

-

ii

Transverse displacement constraint:

-

iii

Normal stress under harmonic excitation:

-

iv

Photoacoustic pressure excitation:

-

v

Carrier generation due to illumination:

These five conditions form a linear system that enables evaluation of the amplitude constants \(Z_{i}\). Substituting them into the general solution yields the complete field response of the medium under coupled photo–acoustic–thermoelastic excitation.

Stochastic analysis for the main functions

Stochastic carrier density

The constants \(Z_{j} (j = 1,\;2,\;3,\;4,\;5)\) are initially defined as linear functions of the deterministic boundary carrier density \(N_{1} (t),\) such that:

The boundary carrier density is modelled as a stochastic process to incorporate uncertainty in the thermal input, consistent with established approaches in stochastic process theory38,42,43. Specifically, the boundary condition \(N_{0} (t)\) is expressed as the sum of a deterministic function \(N_{1} (t)\) and a stochastic fluctuation \(\varphi_{0} (t)\), yielding:

This process is assumed to be zero-mean, satisfying:

The function \(\varphi_{0} (t)\)) is taken to be a white noise process on the surface38,43. Consequently, the system becomes stochastic, as all physical fields inherit randomness from this perturbed boundary condition. The ensemble mean of the perturbed carrier density field converges with the deterministic solution as the number of realizations increases. That is,

where \(n\) is the number of realizations, \(N(x,y,t)\) is the deterministic carrier density field, and \(\varphi_{0}^{l}\) represents the \(l^{th}\) realization of the white-noise process. This ensures preservation of the mean temperature field in the limit of large \(n\). Since the noise has zero mean \(E[\varphi_{0} (t)] = 0,\) the mean of the carrier density field over all realizations equals the deterministic solution.

That is,

This indicates that the mean behavior of the carrier density distribution is preserved, while the random component only affects the variance and higher-order statistical moments38,42,43. The expression is further written in terms of exponential decay modes associated with the solution to the governing differential equation. Each mode includes both constant and boundary-dependent coefficients,

Applying Eq. (65) and inserting them into Eq. (70) the carrier density distribution is split into two parts,\(\Gamma (x,y,t)\) is the deterministic part, \({\mathbb{Z}}(x,y,t)N_{0} (t)\) is the influence function (or transfer kernel), which describes how the boundary input \(N_{0} (t),\) including its stochastic component \(\varphi_{0} ,\) propagates into the domain, so:

where the two components \(\Gamma (x,y,t)\) and \({\mathbb{Z}}(x,y,t)\) are explicitly defined as:

The coefficients \(A_{ij}\) are determined analytically (as mentioned in Appendix A) and depend on the system’s physical and geometrical parameters. To explicitly account for the stochastic boundary’s influence, the deterministic boundary condition was incorporated by substitute with \({N}_{0}(t)\) in the solution expression from Eq. (71) This yields the updated form of the carrier density field:

The stochastic fluctuation \(\varphi_{0}\) thus acts as a multiplicative noise term, modulated by the spatial–temporal response kernel, and introduces uncertainty into the carrier density distribution across the domain. To simplify the representation of the carrier density field, the solution is split into two distinct terms:

where the deterministic contribution \(N_{d} (x,y,t)\) is defined as:

This separation isolates the random fluctuation \(\varphi_{0} (t),\) which affects the system only through the multiplicative modulation by the response function \({\mathbb{Z}}(x,y,t)\). Such a form is handy for statistical analysis, especially for computing the mean and variance of the carrier density field. The interaction between a system response function and a random input can be expressed via the convolution integral in linear systems with stochastic boundary input. Specifically, the convolution of \({\mathbb{Z}}(x,y,t)\) and \(\varphi_{0} (t)\) is given by:

This formulation describes how the history of the stochastic process \(\varphi_{0} (t)\) influences the carrier density field through the impulse response \({\mathbb{Z}}(x,y,t).\) It is foundational to computing statistical measures such as variance and the stochastic envelope. The carrier density field \(N(x,y,t)\) can be expressed as:

Here, \(N_{d} (x,y,t)\) denotes the deterministic component of the carrier density field. We can rewrite the equation using the Wiener process \(W(u)\) yielding,

This formulation provides a mathematically rigorous description of how stochasticity at the boundary propagates through the system. Squaring Eq. (78) we get:

Taking the expectation on both sides and using properties of stochastic integrals, we obtain:

This simplification is made possible by recalling that:

To compute the variance of the stochastic carrier density field \(N(x,y,t),\) we begin by evaluating the second moment of \(N(x,y,t),\) which includes a deterministic part and a stochastic convolution integral. Applying Eq. (82) into Eq. (81), we can get the following relation,

Introducing the substitution \(\Im = t - u_{1} ,\) the integral is transformed, and the variance is equivalently expressed in terms of \(\Im\) as

To guarantee the convergence of the carrier density variance, suitable boundary conditions are imposed on the stochastic field \(N(x,y,t)\). At the excitation boundary \(x = 0\), the carrier density takes the form \(N(0,y,t) = \Gamma (0,y,t) + {\mathbb{Z}}(0,y,t)N_{0} (t) = N_{0} (t)e^{\omega t + iby}\), where \(N_{0}\) is the equilibrium carrier concentration and \(e^{\omega t + iby}\) represents the harmonic modulation in time and space. This condition implies \(\Gamma (0,y,t)\) and \({\mathbb{Z}}(0,y,t) = e^{\omega t + iby}\), thereby defining the stochastic boundary input. At the far-field boundary, the condition \(\mathop {\lim }\limits_{x \to \infty } N(x,y,t) = 0\) is enforced, reflecting the physical requirement that carrier perturbations vanish deep within the medium, while the kernel satisfies \(\mathop {\lim }\limits_{x \to \infty } {\mathbb{Z}}(x,y,t) < \infty\), ensuring that stochastic fluctuations remain bounded. Collectively, these conditions constrain the behavior of the system so that the stochastic integrals in the variance expression remain finite, thereby ensuring the convergence of the carrier density variance across the domain.

Distribution of temperature (thermal waves)

The temperature field \(T(x,y,t)\) is influenced by the randomness introduced through the stochastic boundary temperature. Based on the deterministic solution form, the temperature can initially be written using the constants \(Z_{n}\) as follows:

By substituting the expression of the constants \(Z_{n}\) in terms of the boundary input \(N_{1} + \varphi_{0}\) and applying the same transformation used in the stochastic carrier density analysis, the temperature field is expressed as:

where \(T_{d} (x,y,t)\), is the deterministic component given by:

And \(G(x,y,t)\), is the stochastic kernel function defined by:

Assuming \(\varphi_{0} (t)\) is a white-noise stochastic process satisfying Eq. (82), the variance of the stochastic temperature becomes:

By changing variables using \(\Im = t - u_{1}\) we obtain:

This integral quantifies the contribution of the boundary randomness to the overall uncertainty in the temperature field.

Stochastic horizontal and vertical displacements

Horizontal displacement

The horizontal displacement \(u(x,y,t)\) is influenced by the stochastic boundary carrier density \(N_{1} + \varphi_{0}\) and is initially given by:

Substituting the expressions of \(Z_{j}\) and applying the stochastic boundary, the displacement becomes:

where \(u_{d} (x,y,t)\), is the deterministic component given by:

And \(X(x,y,t)\), is the stochastic kernel function defined by:

Since the displacement \(u(x,y,t)\) includes a stochastic component due to the random boundary carrier density, its variance can be computed as:

By changing variables using \(\Im = t - u_{1}\) we obtain:

Vertical displacement

The vertical displacement solution can initially be written in its expanded linear form as:

Substituting the expression for the constants \(Z_{j}\) in terms of the deterministic boundary condition \(N_{1} (t)\) and the stochastic fluctuation \(\varphi_{0} (t)\), and inserting them into Eq. (97), the vertical displacement is reformulated as:

where \(v_{d} (x,y,t)\), is the deterministic component given by:

And \(Y(x,y,t)\), is the amplitude of the stochastic response given by:

The variance of the vertical displacement becomes:

By changing variables using \(\Im = t - u\) we obtain:

This provides a measure of the uncertainty in vertical displacement due to random fluctuations on the boundary.

Stochastic normal and shear stresses

Stochastic of normal stresses

The normal stress component \(\sigma_{xx} (x,y,t)\) can be expressed in its expanded form as:

By substituting the expressions of \(Z_{j}\) in terms of the deterministic and stochastic parts of the boundary carrier density, and applying the transformation \(N_{1} + \varphi_{0}\), the stress function becomes:

where \(\sigma_{d} (x,y,t)\), is the deterministic component given by:

And \(S(x,y,t)\), is the amplitude of the stochastic response given by:

The variance of the stress component due to thermal randomness is given by:

Stochastic of shear stress

Similarly, the shear stress component \(\sigma_{xy} (x,y,t)\) can be represented in its linear form as:

Substituting the stochastic boundary condition

where \(\tau_{d} (x,y,t)\), is the deterministic component given by:

And \(R(x,y,t)\), is the amplitude of the stochastic response given by:

The variance due to the stochastic fluctuation is:

Distribution of acoustic pressure

The acoustic pressure field \(P(x,y,t)\) is influenced by the randomness introduced through the stochastic boundary condition. Based on the deterministic solution form, the acoustic pressure can initially be written using the constants \(Z_{n}\) as follows:

By substituting the expression of the constants \(Z_{j}\) in terms of the boundary input \(N_{1} + \varphi_{0}\) and applying the same transformation used in the stochastic carrier density analysis, the acoustic pressure field is expressed as:

where \(P_{d} (x,y,t)\), is the deterministic component given by:

And \(J(x,y,t)\), is the stochastic kernel function defined by:

Assuming \(\varphi_{0} (t)\) is a white-noise stochastic process satisfying Eq. (82), the variance of the stochastic acoustic pressure becomes:

By changing variables using \(\Im = t - u_{1}\) we obtain:

This integral quantifies the contribution of the boundary randomness to the overall uncertainty in the acoustic pressure field.

Distribution of dilation strain

The dilation strain field \(e(x,y,t)\) is influenced by the randomness introduced through the stochastic boundary condition. Based on the deterministic solution form, the dilation strain can initially be written using the constants \(Z_{n}\) as follows:

By substituting the expression of the constants \(Z_{j}\) in terms of the boundary input \(N_{1} + \varphi_{0}\) and applying the same transformation used in the stochastic carrier density analysis, the acoustic pressure field is expressed as:

where \(e_{d} (x,y,t)\), is the deterministic component given by:

And \(I(x,y,t)\), is the stochastic kernel function defined by:

Assuming \(\varphi_{0} (t)\) is a white-noise stochastic process satisfying Eq. (82), the variance of the stochastic dilation strain becomes:

By changing variables using \(\Im = t - u_{1}\) we obtain:

This integral quantifies the contribution of the boundary randomness to the overall uncertainty in the dilation strain field.

Numerical results and discussion

In this section, we present the numerical results obtained using silicon (Si) material properties, as outlined in Table 1. These constants were employed to model the response of the semiconductor medium under the combined effects of magnetic field and photo-acoustic excitation, consistent with earlier studies on silicon-based semiconductor media10,11,12,35. The simulations were carried out using Python, implementing a custom computational routine to solve the governing equations described earlier. The results are illustrated through a series of figures, each demonstrating the variation of key response quantities, such as acoustic pressure, displacement, carrier density, and temperature, as a function of time, spatial coordinates, or varying system parameters. The figures aim to reveal the dynamic behavior of the system under stochastic and thermal excitation, offering insights into the influence of key constants on wave propagation and thermal transport in the non-local semiconductor medium.

Amplitude profiles of thermoelastic, electronic, mechanical, and acoustic fields

Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 present the amplitude distributions of the thermoelastic, electronic, mechanical, and acoustic fields along the spatial axis \(x\), excluding the oscillatory exponential factor \(e^{\omega t + iby}\). Figure 2 shows the temperature amplitude \(T^{ * }\), which decays rapidly with distance from the surface, indicating strong confinement of thermal energy near the boundary. A similar decay is observed in Fig. 3 for the carrier density amplitude \(N^{ * }\), reflecting the diminishing influence of photo-generated carriers as the excitation penetrates deeper. The displacement amplitude in the \(x\)-direction, \(u^{ * }\), illustrated in Fig. 4, initially rises to a sharp peak close to the boundary before decaying, signifying localized elastic deformation. In contrast, the transverse displacement amplitude \(v^{ * }\) in Fig. 5 exhibits an initial negative excursion (compression) followed by gradual recovery, capturing the lateral elastic response. The normal stress amplitude \(\sigma_{xx}^{ * }\) in Fig. 6 starts with a large compressive value near the surface and relaxes toward zero with increasing \(x\), while the shear stress amplitude \(\sigma_{xy}^{ * }\) in Fig. 7 peaks near the boundary and diminishes rapidly, highlighting the coupling between thermal and shear responses. The acoustic pressure amplitude \(P^{ * }\), shown in Fig. 8, decays sharply, demonstrating that photoacoustic waves are strongly localized near the illuminated surface. Finally, Fig. 9 illustrates the dilatation amplitude \(e^{ * }\), which decreases exponentially with a slight overshoot before stabilizing, characterizing the volumetric relaxation of the medium. Collectively, these results emphasize the localized nature of thermal, electronic, elastic, and acoustic responses, offering a clear representation of the stationary amplitude envelopes relevant to stochastic and Monte Carlo analyses.

The influence of the non-local parameter

Figures 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17 illustrate the spatial variation of the dimensionless physical fields in the context of photo-thermo-elasticity theory under the influence of the non-local parameter \(\xi_{1}\). In Fig. 10, the temperature distribution \(T(x)\) exhibits a decaying exponential behavior, where an increase in \(\xi_{1}\) leads to a noticeable reduction in the thermal peak near the boundary and a faster decay rate, reflecting enhanced non-local thermal conduction effects. Figure 11 presents the carrier density \(N(x)\), which also decays exponentially; however, it is minimally affected by changes in \(\xi_{1}\), indicating that the non-local parameter has a negligible impact on the photogenerated carrier diffusion. In Fig. 12, the in-plane displacement \(u(x)\) shows a clear peak close to the surface and diminishes as \(\xi_{1}\) increases, implying that non-local effects suppress elastic deformation. A similar trend is observed in Fig. 13 for the transverse displacement \(v(x)\), with a prominent surface response that becomes damped for higher values of \(\xi_{1}\), accompanied by a shift in the sign, indicating oscillatory-type behavior induced by coupling with thermal and photogenerated fields. Figure 14 illustrates the normal stress \(\sigma_{xx}\), which rises monotonically from compressive stress near the boundary to zero as \(x\) increases; higher \(\xi_{1}\) values reduce the stress magnitude near the boundary, showing stress relaxation effects under non-local elasticity. In contrast, Fig. 15 shows the shear stress \(\sigma_{xy}\) rapidly decaying with oscillations around zero; increasing \(\xi_{1}\) significantly damps this response, confirming the stabilizing influence of non-local interactions on shear behavior. The photoacoustic pressure \(P(x)\) in Fig. 16 demonstrates a steep initial peak followed by exponential decay, with almost no change under varying \(\xi_{1}\), suggesting that the pressure field is predominantly governed by local photo-excitation mechanisms rather than non-locality. Finally, Fig. 17 depicts the strain distribution \(e(x)\), which exhibits a highly oscillatory and non-monotonic decay pattern near the boundary. As \(\xi_{1}\) increases, the strain amplitude significantly decreases, and the oscillatory behavior becomes smoother, indicating that non-local effects reduce internal deformation gradients and contribute to a more stable strain field. Physically, these trends reveal that the non-local parameter \(\xi_{1}\) acts as a stabilizing mechanism in the semiconductor medium. By allowing each material point to interact with its neighborhood rather than only its immediate location, non-locality enhances thermal diffusion, suppresses localized deformation peaks, and reduces sharp stress oscillations. This explains why temperature decays faster, displacements are damped, and stress/strain fields become smoother with increasing \(\xi_{1}\). In contrast, carrier density and acoustic pressure remain largely insensitive, since they are primarily governed by diffusion-recombination balance and local photoacoustic excitation, respectively. Overall, the results confirm that non-locality mitigates strong field gradients and improves system stability, linking the observed numerical patterns directly to the underlying physical mechanisms of energy transport and elastic wave dispersion in the medium.

Effect of magnetic field intensity \(R_{h}\) on various physical quantities during thermoelastic and photoacoustic responses

Figures 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 and 25 display the influence of the magnetic field intensity parameter \(R_{h}\) on the distributions of physical quantities within the framework of photo-thermo-elasticity. Figure 18 shows the temperature profile \(T(x)\), where increasing \(R_{h}\) results in a noticeable decrease in the thermal peak and a more rapid decay along the spatial domain. This behavior highlights the enhanced damping effect introduced by the magnetic field on thermal diffusion. In Fig. 19 the carrier density \(N(x)\) shows negligible sensitivity to variations in \(R_{h}\), implying that the magnetic field does not significantly affect the carrier recombination or diffusion mechanisms. Figure 20 presents the in-plane displacement \(u(x)\), which decreases in both peak amplitude and spatial extent as \(R_{h}\) increases, indicating that the magnetic field suppresses thermoelastic deformation due to its resistive Lorentz force contribution. A similar trend is seen in Fig. 21 for the transverse displacement \(v(x)\), where the oscillatory nature of the displacement is reduced under higher magnetic field strengths, leading to more stable mechanical behavior. Figure 22 shows the axial stress \(\sigma_{xx}\), which becomes less negative ‘near the boundary and transitions to zero faster as \(R_{h}\) increases. This suggests that the magnetic field alleviates the compressive stress buildup. In Fig. 23 the shear stress \(\sigma_{xy}\) also shows a significant reduction in amplitude and oscillations with increasing \(R_{h}\), reinforcing the notion that magnetic effects mitigate interfacial shear. The photoacoustic pressure \(P(x)\), shown in Fig. 24 remains nearly unaffected by variations in \(R_{h}\), which suggests that the pressure field is primarily governed by optical excitation rather than magneto-thermoelastic coupling. Finally, Fig. 25 illustrates the strain distribution \(e(x)\), where increasing \(R_{h}\) leads to a clear reduction in the strain amplitude and a smoother profile. This confirms the magnetic field’s role in damping internal deformation and stabilizing the photo-thermoelastic response. These results highlight the role of the magnetic field as a stabilizing agent in the coupled photo-thermoelastic system. The Lorentz force resists charge carrier motion, which in turn reduces the thermoelastic energy transfer into mechanical deformation. This explains the damping of displacements, stresses, and strain amplitudes with higher \(R_{h}\). The temperature field also shows enhanced decay, since the magnetic field restricts thermal transport by coupling with the moving carriers. On the other hand, photoacoustic pressure and carrier density remain largely unaffected because their dynamics are dominated by optical absorption and recombination rather than magneto-mechanical forces. Overall, the observed patterns confirm that the magnetic field primarily suppresses elastic and thermal instabilities, linking the numerical trends to the underlying magneto-thermoelastic physics.

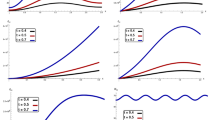

Stochastic envelope estimation and the effect of boundary noise on field profiles with 30 realizations

Figures 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 and 33 illustrate the stochastic envelope of the primary physical fields affected by temperature fluctuations modelled via the Wiener process. Each figure presents four distinct curves: the deterministic solution (red line), the approximated mean of 30 realizations (blue line), and the corresponding upper and lower bounds constructed using the standard deviation (black and green lines, respectively). Figure 26 displays the temperature \(T(x)\), where the stochastic upper and lower bounds deviate notably from the deterministic solution near the boundary, capturing the uncertainty due to random heat input. The envelope narrows with increasing \(x\), indicating the dissipative nature of thermal noise. Figure 27 shows the carrier density \(N(x)\), which exhibits a similar envelope behavior but with more significant spread in the lower bound, reflecting sensitivity to random perturbations in the thermal field. Figure 28 presents the in-plane displacement \(u(x)\), where the stochastic envelope reveals substantial deviations from the deterministic solution in the vicinity of the peak, suggesting that mechanical responses are strongly influenced by thermal randomness. In Fig. 29, the transverse displacement \(v(x)\) also exhibits stochastic variability, though the effect is relatively moderate and concentrated near the origin. Figure 30 plots the axial stress \(\sigma_{xx}\), which shows wider uncertainty bands in the near-surface region, consistent with higher stress gradients induced by fluctuating thermal input. Figure 31 demonstrates the shear stress \(\sigma_{xy}\), where the stochastic effect leads to visible oscillatory deviations in the envelope around the deterministic profile, indicating that the shear response is highly susceptible to thermal noise. In Fig. 32, the acoustic pressure \(P(x)\) shows a bounded stochastic influence, with the envelope tightly tracking the deterministic curve except near the initial peak. Lastly, Fig. 33 depicts the strain field \(e(x)\), which shows a clear difference between the deterministic and mean response, with the stochastic envelope capturing potential undershooting and overshooting behavior due to the randomness in temperature evolution. Collectively, these results emphasize the critical role of stochastic thermal effects in broadening the solution space and quantifying uncertainty in photo-thermoelastic systems. From a physical perspective, the widening of the stochastic envelopes near the boundary directly reflects the amplification of thermal noise in regions with strong gradients of temperature and stress. The Wiener process introduces random fluctuations in heat input, which propagate into the elastic and carrier fields, causing overshooting/undershooting behavior relative to the deterministic solution. As the distance xxx increases, dissipation mechanisms suppress these fluctuations, leading to narrower envelopes and convergence toward deterministic profiles. The stronger sensitivity of displacement and shear stress compared to carrier density and acoustic pressure highlights that elastic responses are more vulnerable to random perturbations than optical or carrier-driven fields. Thus, these stochastic envelopes provide a quantitative measure of uncertainty propagation in photo-thermoelastic media, linking the observed numerical deviations directly to the underlying mechanism of noise-driven thermal fluctuations.

Convergence behavior of stochastic envelopes with increased realizations

Figures 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 and 41 demonstrate the statistical behavior of the main physical quantities under boundary noise, computed over 500 stochastic realizations. Compared to the earlier case with 30 realizations, this set highlights the convergence of the approximated mean toward the deterministic solution, reinforcing that increasing the number of realizations stabilizes the stochastic estimates and reduces the influence of random fluctuations. In Fig. 34, the temperature field \(T(x)\) shows excellent agreement between the stochastic mean and deterministic curve, especially beyond \(x > 1\), indicating that the thermal field becomes statistically stable even under noisy boundary conditions. The envelope bounds (black and green) are smoother and narrower than in the 30-realization case, confirming variance reduction with larger samples. Figure 35 illustrates the carrier density \(N(x)\) profile. The mean and deterministic solutions are almost indistinguishable throughout the domain, and the upper and lower bounds lie within a tightly confined region, emphasizing the robustness of carrier dynamics against stochastic fluctuations. In Figs. 36 and 37, the displacements \(u(x)\) and \(v(x)\) show moderate variance near the boundary but with a visibly smoother and narrower envelope compared to previous realizations. This confirms that mechanical responses converge well in expectation as the sample size increases while also providing insight into the residual variability due to boundary-induced randomness. Figures 38 and 39 present the normal and shear stress components \(\sigma_{xx} (x)\) and \(\sigma_{xy} (x)\), which continue to show higher sensitivity to noise near the boundary. However, the upper and lower bounds now form clear and smooth confidence intervals, which were previously oscillatory with fewer realizations. This improvement reinforces the effectiveness of statistical averaging in modeling stress fields. In Fig. 40, the acoustic pressure \(P(x)\) again exhibits reduced variability with a tightly bound envelope. The approximated mean remains consistently close to the deterministic curve, showing stable pressure propagation under noise. Finally, Fig. 41 illustrates the strain \(e(x)\). Although still slightly sensitive near \(x = 0\), its envelope is narrower and much smoother than in previous cases. This indicates that strain fluctuation becomes quantifiable and predictable with many realizations. The convergence behavior between 30 and 500 realizations is clearly illustrated in Figs. 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 and 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 and 41). For 30 realizations, the estimated mean response already follows the deterministic solution closely, but the upper and lower bounds remain irregular due to the limited sampling size. When the number of realizations is increased to 500, the stochastic envelopes become significantly smoother and narrower, consistent with the theoretical convergence rate of Monte Carlo sampling, which decreases as \(O\left( {{1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 {\sqrt N }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\sqrt N }}} \right)\). This reduction in statistical scatter indicates that the computed stochastic mean has reached a stable approximation of the exact expectation. Physically, the stochastic envelopes represent the possible range of system responses in the presence of random boundary perturbations. The upper and lower bounds can be interpreted as confidence bands, showing the excursions of temperature, carrier density, displacement, stresses, acoustic pressure, and strain under noisy excitation. This envelope-based representation is highly valuable because it does not only tracks the deterministic trend but also quantifies uncertainty and fluctuation levels. From a practical perspective, such information enhances the reliability of the model: in noisy operational environments, engineers and designers can evaluate not just the average performance but also the variance and worst-case limits of the system. Thus, the use of stochastic envelopes ensures that the proposed framework accounts for robustness, providing greater confidence in semiconductor and optoacoustic device performance under realistic noisy conditions.

Effect of noise parameter \(\sigma\) on the stochastic thermal field on the boundaries

In our formulation, the variance and stochastic envelope were obtained using a Monte Carlo procedure with 30 or 500 independent realizations of the Wiener process \(W(t)\). For each realization, the stochastic perturbations were generated adaptively at every time step with increment \(\Delta W(t)\) following a Gaussian distribution \({\rm N}(0,\sigma^{2} \Delta t)\) with zero mean and variance \(\sigma^{2} \Delta t\), consistent with the definition of white noise. The ensemble-averaged fields were then used to compute the mean response, while the standard deviation defined the upper and lower stochastic bounds. This procedure captures both the deterministic mean-field dynamics and the variability introduced by random fluctuations, ensuring that the stochastic kernels evolve dynamically rather than relying on precomputed noise samples. As a special case, we present the results for 30 realizations to illustrate the impact of the noise intensity parameter \(\sigma\) on the thermal response. The noise parameter σ governs the volatility of fluctuations, linking microscopic random excitations to the macroscopic thermoelastic and photothermal response of the medium. A normalized value of \(\sigma = 0.1\) was adopted to balance weak and excessively strong stochastic forcing, enabling the model to reproduce both deterministic-like dynamics and the variability arising from higher-order statistical fluctuations. Figures 42, 43, 44, 45 illustrate the effect of increasing σ on the temperature distribution for \(\sigma = 0.1\), \(0.2\), \(0.3\), and \(0.4\), respectively. For \(\sigma = 0.1\) Fig. 42, the thermal field remains close to the deterministic profile, with narrow stochastic bounds and minimal fluctuations. For \(\sigma = 0.1\) Fig. 43, noise becomes more visible near the boundary region, though the approximated mean still aligns closely with the deterministic solution. At \(\sigma = 0.3\) Fig. 44, variability is amplified, producing noticeable irregular oscillations in the stochastic bounds. Finally, at \(\sigma = 0.4\) Fig. 45, the temperature field exhibits strong random fluctuations, with the stochastic envelope dominating the response and deviating substantially from the deterministic profile. These results confirm that increasing σ amplifies stochastic variability, driving the system from near-deterministic behaviour to highly uncertain dynamics.

Heatmap visualization of randomness-induced fluctuations

Figures 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 and 53 illustrate the stochastic behavior of the primary physical fields under 500 realizations, represented as heatmaps across the spatial domain \(x \in [0,7][0,7]\). These visualizations highlight the propagation and attenuation of noise resulting from boundary-induced randomness. In Fig. 46 the temperature profile \(T(x)\) exhibits high variability near the boundary at \(x = 0\), which quickly decays along the domain, indicating effective thermal diffusion and stabilization. Similarly, Fig. 47 displays the randomness in the carrier density profile \(N(x)\), where the strongest fluctuations also occur near the boundary and fade with increasing \(x\), suggesting strong recombination or absorption mechanisms of the photocarriers. The horizontal and vertical displacement profiles \(u(x)\) and \(v(x)\) shown in Figs. 48 and 49, respectively, reveal significant stochastic variation concentrated near the boundary, with gradual damping away from the source, reflecting the system’s elastic stability under dynamic loading. For the normal stress \(\sigma_{xx} (x)\) in Fig. 50, the heatmap shows compressive fluctuations localized near the excitation region, followed by rapid attenuation, indicating localized mechanical impact due to noise. In contrast, Fig. 51, which shows the shear stress \(\sigma_{xy} (x)\), displays bi-directional randomness with pronounced variation at the boundary and minimal spread beyond, consistent with rapid shear wave damping. Figure 52 depicts the pressure field, which exhibits high variability near the noise-injected boundary but remains largely stable along the domain, highlighting the system’s ability to localize and dampen pressure-induced fluctuations. Lastly, Fig. 53 presents the randomness in the strain distribution \(e(x)\), showing moderate fluctuations near the boundary that diminish steadily, reaffirming the material’s mechanical resilience under stochastic loading conditions. Overall, these heatmaps emphasize that while boundary noise significantly perturbs each function near \(x = 0\), the stochastic effects are effectively contained and decay spatially, confirming the stability of the medium under noisy excitation and the reliability of the approximated mean solutions over many realizations. The heatmaps in Figs. 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 and 53 provide an engineering-oriented visualization of how physical quantities fluctuate under 500 stochastic realizations, offering a spatial statistical map of uncertainty across the medium. Unlike line plots, which only show mean and bounds, the heatmaps reveal localized zones where fluctuations are most intense and stability naturally emerges. For instance, high-variance regions near the illuminated boundary correspond to areas of greater thermal and mechanical sensitivity. At the same time, the rapid decay of randomness with depth indicates robust stability farther inside the material. From an engineering perspective, such visualizations are essential for designing semiconductor and opto-acoustic devices that must operate in noisy thermal environments, since they allow designers to identify potential hotspots, stress concentrations, and regions of reliable performance. In this way, heatmaps confirm statistical convergence and serve as diagnostic tools that guide material tailoring and optimization strategies to ensure resilience under stochastic operating conditions.

White noise versus colored noise assumptions

In the present analysis, thermal fluctuations at the boundary were modeled using white noise, which is characterized by zero mean and the absence of temporal or spatial correlation. This assumption simplifies the mathematical formulation and ensures that the mean stochastic solution coincides with the deterministic response, while random deviations are captured through the variance and stochastic envelope. However, real thermal environments are often better represented by colored noise, where fluctuations possess finite correlation and a non-uniform spectral distribution. For instance, red noise emphasizes low-frequency variations with long-term persistence, while blue noise highlights high-frequency fluctuations. Incorporating colored noise would primarily affect the spread and structure of the stochastic envelope: correlated fluctuations would either amplify or suppress variance in specific frequency ranges, thereby modifying the uncertainty bands without altering the deterministic mean solution. Consequently, while the white noise approximation provides a mathematically tractable baseline, extending the model to account for colored noise could offer a more realistic description of experimental thermal fluctuations.

Conclusion

This study developed a comprehensive two-dimensional model to investigate the magneto-photo-thermal behavior of wave propagation in non-local semiconductor media under the framework of coupled thermoelasticity theory. The material was considered homogeneous and isotropic, and the governing equations were formulated based on small deformation and linear elasticity assumptions. The model incorporated full coupling between thermal conduction, elastic deformation, acoustic pressure, and carrier density transport. By employing the normal mode method and separation of variables with harmonic time dependence, the system of partial differential equations was reduced to a set of solvable ordinary differential equations, enabling the derivation of exact analytical solutions. The physical responses including displacements, stress components, acoustic pressure, carrier density, and strain were analyzed under variations in the non-local parameter and magnetic field intensity. The results highlighted the stabilizing and damping roles of both non-local elasticity and magnetic fields in wave attenuation and mechanical response. A key research gap addressed in this work is the absence of stochastic boundary formulations in existing non-local photo-thermoelastic models. Earlier studies have largely relied on deterministic excitation, which cannot capture the randomness introduced by laser fluctuations, material heterogeneity, or thermal noise. By incorporating stochastic boundary conditions through a zero-mean Wiener process, this study enhances the understanding of non-local semiconductor behavior by quantifying how uncertainty propagates through coupled fields and influences stability, variance, and reliability of the system response. The contribution of this work lies in its extension to stochastic modeling, where thermal excitation at the boundary was perturbed using a zero-mean Wiener process. Through envelope estimation for both 30 and 500 realizations, the influence of thermal randomness on system behavior was quantified. The results demonstrated that increasing the number of realizations significantly reduced stochastic noise and yielded smoother, more statistically reliable physical responses. Furthermore, a heat map visualization was generated to illustrate the spatial distribution of uncertainty across the domain, offering additional insights into the stochastic behavior of the system. In comparison with previous deterministic models, the present framework introduces three key improvements. First, it incorporates stochastic boundary conditions that realistically represent thermal fluctuations and material irregularities. Second, it enables probabilistic characterization of responses through variance, envelope estimation, and mean convergence, thereby providing a more reliable prediction of semiconductor performance under uncertainty. Third, it unifies magneto-photo-thermoelastic and opto-acoustic interactions with non-local effects under stochastic excitation, delivering a more comprehensive and scientifically rigorous representation of wave propagation in semiconductor media. This work provides a robust theoretical and stochastic framework for modeling complex multi-physics interactions in advanced semiconductor materials. The outcomes of this study hold potential applications in the design and optimization of advanced optoelectronic components, photoacoustic imaging systems, microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), semiconductor energy-conversion devices, and thermal management systems that operate under magneto-thermoelastic and stochastic conditions. The unified framework developed here can support the engineering of next-generation materials and devices functioning under variable and uncertain thermal environments, directly relevant to photovoltaics, energy harvesting, smart materials, and nano-engineered sensors. In terms of future directions, the present framework may be extended to incorporate more sophisticated models and Multiphysics effects. Possible avenues include combining the Moore–Gibson–Thompson equation with two-temperature theories under stochastic excitation, exploring three-phase-lag models with microstretch continua and gravitational effects coupled with stability analysis using the Routh–Hurwitz criterion, and employing Love–Bishop rod theory within micropolar continua under moisture diffusion and stochastic influences. These extensions would provide a richer understanding of wave propagation, resonance, and stability in complex media and expand the model’s applicability to a wider range of engineering and physical problems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alzahrani, F. S. & Abbas, I. A. Photo-thermo-elastic interactions without energy dissipation in a semiconductor half-space. Results Phys. 15, 102805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2019.102805 (2019).

Mondal, S. & Sur, A. Photo-thermo-elastic wave propagation in an orthotropic semiconductor with a spherical cavity and memory responses. Waves Random Complex Media 31, 1835–1858. https://doi.org/10.1080/17455030.2019.1705426 (2021).

Kumar, R., Tiwari, R. & Singhal, A. Analysis of the photo-thermal excitation in a semiconducting medium under the purview of DPL theory involving non-local effect. Meccanica 57, 2027–2041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11012-022-01536-2 (2022).

Hobiny, A. D. & Abbas, I. A. Fractional order photo-thermo-elastic waves in a two-dimensional semiconductor plate. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 133, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/i2018-12054-6 (2018).

Geetanjali, G., Bajpai, A. & Sharma, P. K. Memory response of photo-thermo-diffusive elastic medium containing a spherical cavity with nonlocal effects. Mech. Solids 58, 3244–3262. https://doi.org/10.3103/S0025654423600654 (2023).

Sherief, H. & Abd El-Latief, A. M. Effect of variable thermal conductivity on a half-space under the fractional order theory of thermoelasticity. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 74, 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2013.05.016 (2013).

Abouelregal, A. E., Ahmad, H., Elagan, S. K. & Alshehri, N. A. Modified Moore–Gibson–Thompson photo-thermoelastic model for a rotating semiconductor half-space subjected to a magnetic field. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 32, 2150163. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0129183121501631 (2021).

Abouelregal, A. E. et al. Fractional MGT model for photothermal analysis in rotating semiconductors: Insights into anomalous diffusion and thermal wave propagation. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 131, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-025-08614-8 (2025).

Askar, S. S., Abouelregal, A. E., Foul, A. & Sedighi, H. M. Pulsed excitation heating of semiconductor material and its thermomagnetic response on the basis of fourth-order MGT photothermal model. Acta Mech. 234, 4977–4995. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00707-023-03639-7 (2023).

Ahmed, I. E., Abouelregal, A. E. & Aldandani, M. Study of the behavior of photothermal and mechanical stresses in semiconductor nanostructures using a photoelastic heat transfer model that incorporates non-singular fractional derivative operators. Acta Mech. 236, 1339–1358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00707-024-04195-4 (2025).

Abouelregal, A. E. Response of thermoelastic cylindrical cavity in a non-local infinite medium due to a varying heat source. Waves Random Complex Media 32, 1725–1742. https://doi.org/10.1080/17455030.2020.1834171 (2022).

Abouelregal, A. E., Marin, M. & Öchsner, A. The influence of a non-local Moore–Gibson–Thompson heat transfer model on an underlying thermoelastic material under the model of memory-dependent derivatives. Contin. Mech. Thermodyn. 35, 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00161-023-01195-y (2023).

Chandel, N., Khalsa, L., Abouelregal, A., Varghese, V. & Dhore, N. Photothermal diffusion in nonsimple semiconductor strips: Impact of moving heat sources and acoustic pressure via memory and nonlocality effects, ZAMM Zeitschrift Fur Angew. Math. Und Mech. 105, e70061. https://doi.org/10.1002/zamm.70061 (2025).

Chandel, N., Khalsa, L. & Varghese, V. Non-simple thermoelastic diffusion interaction in a half-space with nonlocality and memory effect. J. Therm. Stress. 48, 292–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495739.2024.2449067 (2025).

Chandel, N., Khalsa, L., Varghese, V. & Yadav, A. K. Nonlocal thermoelastic analysis of a spherically symmetric elastic sphere with memory effects. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376494.2024.2422575 (2024).

Bhattacharya, D. & Kanoria, M. Refined four-phase lag model for elasto-thermodiffusive interaction with harmonically varying heat sources. Mech. Time-Dependent Mater. 28, 1853–1872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11043-024-09719-y (2024).

Bhattacharya, D., Purkait, P. & Kanoria, M. Memory response on the elasto-thermodiffusive interaction subjected to harmonically varying heat source. J. Multiscale Model. 13, 2250002. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1756973722500020 (2022).

Abouelregal, A. E. & Salem, M. G. The thermal vibration of small-sized rotating fractional viscoelastic beams positioned on a flexible foundation in the light of the Moore–Gibson–Thompson model. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joes.2022.06.016 (2022).

Tiwari, R., Saeed, A. M., Abouelregal, A., Singhal, A. & Salem, M. G. Nonlocal thermoelastic waves inside nanobeam resonator subject to various loadings. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 52, 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/15397734.2022.2104312 (2024).

Salem, M. G., Abouelregal, A. E., Elzayady, M. E. & Sedighi, H. M. Biomechanical response of skin tissue under ramp-type heating by incorporating a modified bioheat transfer model and the Atangana-Baleanu fractional operator. Acta Mech. 235, 5041–5060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00707-024-03988-x (2024).

Abouelregal, A. E., Salem, M. G., Alhassan, Y., Sedighi, H. M. & Kordi, M. Fractional triple-phase lag theory with non-singular kernels: Analyzing the thermo-viscoelastic behavior of living skin tissue with bioheat transfer. Acta Mech. 236, 3669–3694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00707-025-04326-5 (2025).

Deswal, S., Sheokand, P. & Punia, B. S. Interactions due to Hall current and photothermal effect in a magneto-thermoelastic medium with diffusion and gravity. Acta Mech. 235, 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00707-023-03748-3 (2024).

Salah, D. M., Abd-Alla, A. M., Abo-Dahab, S. M., Alharbi, A. M. & Abdelhafez, M. A. Magneto-thermoelastic semiconductor medium with diffusion under the hyperbolic two-temperature photothermal waves. Mech. Solids 59, 1774–1791. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0025654424603768 (2024).

Sur, A. Magneto-photo-thermoelastic interaction in a slim strip characterized by hereditary features with two relaxation times. Mech. Time-Dependent Mater. 28, 1465–1490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11043-023-09658-0 (2024).

Salah, D. M., Abd-Alla, A. M., Abo-Dahab, S. M., Alharbi, F. M. & Abdelhafez, M. A. Magnetic field and initial stress on a rotating photothermal semiconductor medium with ramp type heating and internal heat source. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64485-8 (2024).

Yadav, A. K. Photothermal plasma wave in the theory of two-temperature with multi-phase-lag thermo-elasticity in the presence of magnetic field in a semiconductor with diffusion. Waves Random Complex Media https://doi.org/10.1080/17455030.2020.1854489 (2020).

Jatain, S., Deswal, S. & Kalkal, K. K. Thermodynamical interactions in a micropolar magneto-thermoelastic medium with photothermal effect. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 33, 3642–3668. https://doi.org/10.1108/HFF-04-2023-0232 (2023).

Khalil, E. M., Abo-Dahab, S. M. & Kilany, A. A. Electromagnetic field and initial stress on a photothermal semiconducting voids medium under thermoelasticity theories. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 44(9), 7778–7798. https://doi.org/10.1002/mma.6942 (2021).