Abstract

This study reports the green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) using the nematophagous fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora and their evaluation as nematicidal agents against Meloidogyne incognita. The ZnO NPs were synthesized from fungal culture filtrate and characterized by UV–Vis, FTIR, XRD, Raman spectroscopy, SEM, TEM and EDAX confirming nanoscale particles (29.45–71.30 nm) with hexagonal wurtzite crystallinity. ^1H NMR-based metabolomics revealed functionalization of the nanoparticle surface with fungal metabolites, notably riboflavin and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine. In vitro bioassays demonstrated strong, dose-dependent nematicidal activity, achieving 94.8% juvenile mortality at 200 µg/mL after 72 h, significantly higher than the fungal extract alone (p < 0.05). Molecular docking showed that ZnO–riboflavin bound effectively to acetylcholinesterase and ZnO–UDP-GlcNAc to chitin synthase, suggesting dual disruption of neural signaling and cuticle biosynthesis. Collectively, these findings establish A. oligospora-mediated ZnO NPs as a metabolite-enriched nano-biocomposite with enhanced nematicidal efficacy, offering a novel and eco-friendly strategy for sustainable crop protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanotechnology has emerged as a transformative discipline in agriculture, offering sustainable solutions to longstanding challenges in crop protection, pathogen management and productivity enhancement. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) have gained significant attention due to their unique physicochemical properties and broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity1. Their high surface area-to-volume ratio, biocompatibility and low toxicity make them suitable for various applications2. ZnO-NPs exhibit antimicrobial effects through mechanisms such as physical contact with cell walls, reactive oxygen species generation and zinc ion release3. While traditional chemical and physical synthesis methods exist, green synthesis using microbial-mediated approaches offers an eco-friendly and cost-effective alternative2,4.

Filamentous fungi have emerged as efficient platforms for nanoparticle synthesis due to their exceptional metal tolerance, high enzymatic activity and ability to secrete diverse biomolecules5,6. These organisms can produce nanoparticles both extracellularly and intracellularly, offering advantages such as high yields, enhanced stability and ease of recovery7. Fungal-mediated synthesis is considered sustainable, economical and biocompatible, resulting in nanoparticles with desirable size, morphology and physiochemical characteristics6. The process utilizes fungal enzymes and proteins as reducing agents, enabling the conversion of metal salts into nanoparticles5.

Arthrobotrys oligospora is a nematode-trapping fungus with strong potential for biological control of plant-parasitic nematodes. It forms adhesive trapping nets and produces nematocidal metabolites, making it effective against diverse nematode species8. Recent studies have demonstrated its high predation rates against economically important nematodes9, positioning A. oligospora as a promising candidate for integrated pest management. While A. oligospora-mediated sulfur nanoparticles have been explored to enhance bionematicides such as Cry5B10, its potential as a nano-factory for generating bio-functional nanoparticles with dual-action nematicidal activity remains largely unexplored.

Root-knot nematodes (RKNs), particularly Meloidogyne spp., are among the most damaging agricultural pests worldwide, causing significant crop losses11,12. Current nematicides are often chemically synthetic, non-specific and environmentally detrimental, underscoring the urgent need for novel, biodegradable and target-specific alternatives. Nanoparticles synthesized via biological routes, especially those functionalized with fungal metabolites, represent a promising solution13. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, with its reproducibility and structural elucidation capability, has proven effective in profiling microbial metabolites and has recently been applied to investigate nematode–host–microbe interactions14,15,16.

The present study aims to synthesize ZnO nanoparticles using the nematophagous fungus A. oligospora, characterize their physicochemical properties and evaluate their nematicidal efficacy against M. incognita. Furthermore, it investigates the biochemical basis of activity by integrating ^1H NMR-based metabolomics for metabolite identification with molecular docking against key nematode protein targets (AChE, COX, Hsp90, ODR3).

The novelty of this work lies in demonstrating, for the first time, that A. oligospora-mediated ZnO NPs act as a metabolite-enriched nano-biocomposite with synergistic nanoparticle–metabolite interactions, thereby establishing a dual-action mechanism that disrupts nematode neural signaling and cuticle biosynthesis. This integrated approach provides new mechanistic insights and introduces a sustainable, next-generation strategy for nematode management.

Materials and methods

Fungal and nematode isolation

A. oligospora was isolated from agricultural soil collected from the rhizosphere of nematode-infested crops at the Agricultural Research Farm, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India (25.255100° N, 82.989425° E) using the soil sprinkle technique and cultivated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 25 ± 2 °C. Morphological identification was carried out based on hyphal characteristics, conidial morphology and trap structures observed under light microscopy, using standard taxonomic keys17. For molecular confirmation, genomic DNA was extracted and the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the ribosomal DNA was amplified and sequenced. BLAST analysis of the ITS sequence showed 100% similarity with A. oligospora (GenBank accession no. JX403728.1) confirming the identity of the isolate. Soil collection was conducted with appropriate permission from the Agricultural Research Farm authorities at Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. In this study, M. incognita was isolated from naturally infected tomato roots, a well-established host for this nematode species. Identification was carried out based on second-stage juvenile (J2) morphological characteristics (stylet length, tail shape, hyaline tail terminus) and female perineal patterns, following standard taxonomic keys.

Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles

ZnO-NPs were synthesized using the extracellular filtrate of the fungus A. oligospora (Fig. 1). The fungal biomass was cultivated in Potato dextrose broth for 6 days at 28 ± 2 °C. After incubation, the biomass was collected and washed to remove any residual medium components. The washed biomass was then suspended in 100 mL of distilled water and stirred for 72 h s. Subsequently, an equal volume of 1 mM zinc acetate solution was added to the fungal extract and the mixture was stirred at 150 rpm at a temperature of 32 °C for 72 h in dark conditions. The formation of ZnO-NPs was indicated by the appearance of a white precipitate. The synthesized nanoparticles were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, washed several times with sterile distilled water and dried in an oven at 80 °C. Finally, the dried material was ground into a fine powder for further characterization18,19.

Characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs)

The synthesized ZnO-NPs were characterized using a suite of analytical techniques to evaluate their structural, morphological and optical properties. UV–visible spectrophotometry was employed to confirm nanoparticle formation and assess their optical behavior. The ZnO-NPs were dispersed in distilled water and the absorbance spectrum was recorded in the range of 200–800 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Model: LT-2700, Labtronics). The characteristic absorption peak observed in the UV region was used to estimate the optical band gap of the nanoparticles, confirming their nanoscale nature.

To investigate surface morphology, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was performed. A thin layer of dried ZnO-NPs was mounted on a metal stub, coated with a gold film to enhance conductivity and examined at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV using a SEM instrument (Quanta 200, Thermo fisher). Additionally, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was carried out to obtain detailed insights into the particle size, shape and dispersion characteristics. A drop of a dilute nanoparticle suspension was deposited on a carbon-coated copper grid, dried and analyzed at an accelerating voltage of 100 kV using a TEM (Model: Tecnai 20 G2, Thermo fisher).

Raman spectroscopy was utilized to investigate the vibrational characteristics and crystallinity of the ZnO-NPs. Spectra were recorded using a Raman spectrometer (Model: Alpha300-RAS, WLTec, GmbH) equipped with a 532 nm laser source, covering the range of 100–1,000 cm⁻¹. The structural phase and crystallographic properties of the ZnO-NPs were confirmed through X-ray dif fraction (XRD) analysis. The powdered nanoparticles were scanned over a 2θ range of 20°–80° using an XRD instrument (Model: Empyrean, Manufacturer: Malvern panalytical). The diffraction pattern was used to identify the crystalline phase and calculate the average crystallite size using the Debye–Scherrer equation.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was conducted to identify surface functional groups and confirm the presence of organic moieties potentially involved in capping or stabilizing the nanoparticles during synthesis. For this, the samples were finely ground with potassium bromide (KBr) and analyzed over the spectral range of 400–4,000 cm⁻¹ using a Bruker ALPHA FT-IR spectrometer.

Antinematic activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs)

The antinematic potential of ZnO-NPs was assessed against M. incognita second-stage juveniles (J2s) at four concentrations (50, 100, 150 and 200 µg/mL). For controls, sterile distilled water served as the negative control, while the culture filtrate of A. oligospora (fungal extract) was included as the positive control. Approximately 500 active J2s were exposed to each treatment in sterile cavity blocks and mortality was observed at 18, 24, 48 and 72 h under a stereomicroscope. Juveniles that failed to respond to gentle probing were considered dead. Each treatment, including controls, was performed in five replicates. Mortality percentages were calculated relative to the initial J2 population to evaluate the dose- and time-dependent nematicidal effect of ZnO-NPs.

1H NMR analyses and spectra pre-processing

Nanoparticle sample was added into NMR tubes with a diameter of 5 mm and promptly subjected to analysis. The acquisition of 1H NMR spectra was conducted using a Bruker Avance Neo 600 MHz NMR spectrometer operating at a frequency of 600 MHz. The spectrometer was fitted with a 5 mm broadband observe probe. The metabolic profiles were illustrated using1H NMR spectra of the extract’s deuterium oxide solution at a temperature of 298 K. The1H NMR spectra was pre-processed and some adjustments were made during the procedure. The NMR spectra were processed for phase correction and baseline correction using the programme Topspin 4.5.0 (Brucker). The NMR raw data was analysed using the Chenomx NMR suite V 10.0 software to identify and analyse metabolites.

In silico study

The amino acid sequence of the target protein from Meloidogyne species was retrieved from the NCBI database. Structural modeling was carried out using SWISS-MODEL and I-TASSER and the generated models were evaluated using UCLA SAVESv6.0, QMEAN, ProSA-web and Ramachandran plot analysis. The best model was refined using GalaxyRefine. Homology-based structural alignment and binding site validation were performed using PyMOL and RCSB-PDB-derived homologues. 3D structure of identified metabolites were obtained from the PubChem database and energy minimization was performed using Open Babel. Molecular docking was conducted using AutoDock Vina via PyRx, with visualization of 3D and 2D interactions using PyMOL and LigPlot+, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in five biological replicates, and data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version R-4.4.1). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess the significance of treatment effects. When ANOVA indicated significant differences (p < 0.05), post hoc Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test was applied to compare means across treatments. Graphical representations were generated using R packages, and significance levels are indicated in the corresponding figures and tables.

Results

Physical characterization of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized using A. oligospora

A comprehensive suite of spectroscopic and microscopic techniques was employed to characterize the biosynthesized ZnO-NPs mediated by the nematophagous fungus A. oligospora. The data confirmed the successful synthesis of pure, crystalline ZnO nanoparticles with defined structural, morphological and compositional attributes.

UV–visible spectroscopy

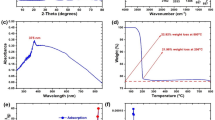

The UV–Visible absorption spectrum (Fig. 2a) of the synthesized ZnO-NPs revealed a prominent and well-defined absorption peak centered at 370 nm, which is characteristic of ZnO due to the intrinsic band-gap absorption arising from electron transitions from the valence band to the conduction band. The sharpness and symmetry of the absorption peak suggest high optical purity and narrow particle size distribution, indicative of minimal aggregation. The absence of additional absorption bands beyond 400 nm confirms the lack of significant impurities or secondary metabolites interfering with the nanoparticle surface. This blue-shifted peak, compared to bulk ZnO (~ 380 nm), also reflects the quantum confinement effect, typically associated with nanoparticles in the sub-100 nm size range.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

FTIR analysis was carried out to identify the surface functional groups responsible for the bioreduction and capping of ZnO-NPs by fungal metabolites (Fig. 2b). A distinct absorption band at 482 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the stretching vibration of Zn–O bonds, confirming the formation of ZnO nanostructures. Peaks at 618 and 877 cm⁻¹ suggest the presence of C–H bending and out-of-plane deformations from fungal-derived hydrocarbons. The intense peak at 1117 cm⁻¹ is attributable to C–O stretching, possibly from polysaccharides or glycosidic linkages. The bands at 1395 and 1649 cm⁻¹ indicate symmetric stretching of carboxylate (COO⁻) groups and amide I bonds, respectively, reflecting the involvement of proteins and amino acids in nanoparticle stabilization. A broad absorption around 3381 cm⁻¹ corresponds to O–H/N–H stretching vibrations, further supporting the role of hydroxyl and amine-rich compounds in nanoparticle capping and dispersion.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis

XRD patterns (Fig. 2c) confirmed the crystalline nature of ZnO-NPs, with diffraction peaks indexed at 2θ = 31.94°, 34.58°, 36.43°, 47.63°, 56.76°, 63.00° and 68.09°, corresponding to the (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103) and (112) planes, respectively. These reflections align well with the hexagonal wurtzite structure of ZnO (JCPDS card No. 36-1451), affirming phase purity. The sharp and narrow peaks are indicative of good crystallinity and minimal lattice strain. No secondary phases or amorphous backgrounds were detected, suggesting high product purity and efficient biosynthesis.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectral analysis (Fig. 2d) exhibited characteristic vibrational modes of ZnO. The prominent peak at 431.12 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the E₂(high) phonon mode, a signature vibration of the wurtzite crystal structure, which is sensitive to particle size and crystallinity. A low-frequency peak at 81.26 cm⁻¹ is also observed, which may arise from acoustic phonon confinement or surface optical modes specific to nanoscale ZnO. The absence of additional defect-related peaks reinforces the high crystallinity and phase integrity of the synthesized nanoparticles.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDAX)

SEM micrographs (Fig. 3a) revealed predominantly spherical to slightly irregular ZnO-NPs with rough surface textures. Particle sizes ranged from 29.45 to 71.30 nm, indicating nanoscale dimensions consistent with optical characterization. Some degree of particle agglomeration was evident, likely due to drying during sample preparation. The corresponding EDAX spectrum (Fig. 3b) confirmed the elemental composition of the ZnO-NPs, displaying dominant peaks for zinc (73.50 wt%) and oxygen (26.50 wt%), with no detectable impurities such as carbon, sulfur, or nitrogen, highlighting the chemical purity of the synthesized nanoparticles.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and EDAX

TEM images (Fig. 3c) provided further confirmation of particle size and morphology. The nanoparticles appeared as discrete, uniformly distributed spheres with diameters ranging from 30 to 50 nm. The clear lattice fringes observed in high-resolution TEM images affirm their crystalline nature. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns (not shown) also displayed concentric diffraction rings corresponding to the wurtzite ZnO structure. EDAX analysis performed in conjunction with TEM (Fig. 3d) validated the stoichiometric composition, with Zn accounting for 74.70 wt% and O for 25.30 wt%, consistent with theoretical values for ZnO.

(a) UV–visible absorption spectrum of biosynthesized ZnO nanoparticles, showing a distinct absorbance peak, indicative of nanoparticle formation, (b) X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized using A. oligospora (black) compared to pure ZnO nanoparticles (red), confirming the crystalline nature and phase purity of the nanoparticles with characteristic ZnO diffraction peaks, (c) Raman spectrum of A. oligospora, highlighting key vibrational modes relevant to the biosynthesis process, (d) Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum of A. oligospora, displaying major transmittance bands associated with functional groups involved in nanoparticle stabilization.

(a) Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) image showing the surface morphology and particle size distribution of ZnO nanoparticles, with particle diameters ranging from ~ 29.45 to ~ 71.30 nm, (b) Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) spectrum corresponding to panel A, confirming the elemental composition with prominent peaks for zinc (Zn) and oxygen (O), indicating the high purity of ZnO nanoparticles, (c) Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) image illustrating the agglomerated, quasi-spherical morphology and nanoscale size of the ZnO nanoparticles, (d) EDS spectrum corresponding to panel C, further validating the elemental makeup with strong Zn and O signals and absence of significant impurities.

Efficacy of biosynthesized ZnO nanoparticles against M. incognita

The nematicidal potential of biosynthesized ZnO-NPs and fungal extract was evaluated against second-stage juveniles (J2) of M. incognita at four exposure intervals: 18, 24, 48 and 72 h (Fig. 4).

At 18 h post incubation (hpi), mortality in the untreated control was minimal (4.94 ± 0.47%), confirming negligible background death under test conditions. In contrast, the fungal extract alone induced 27.18 ± 1.44% mortality, suggesting mild bioactivity possibly due to secondary metabolites or enzymes secreted by A. oligospora. ZnO-NPs displayed strong and dose-dependent nematicidal activity, with mortality increasing significantly across concentrations: 30.54 ± 1.79% at 50 µg/mL, 47.20 ± 1.89% at 100 µg/mL, 62.60 ± 2.53% at 150 µg/mL and 70.42 ± 2.22% at 200 µg/mL. The critical difference (C.D.) at a 5% significance level was 3.505%, confirming that treatments at 100 µg/mL and above were significantly more effective than the fungal extract and lower concentrations. These results highlight the early onset of nematotoxicity by ZnO-NPs, even within 18 h of exposure, indicating rapid interference with J2 viability (Fig. 4a).

By 24 hpi, mortality increased further in all treatments. The fungal extract achieved 34.56 ± 1.55% mortality, while ZnO-NPs treatments induced 40.64 ± 2.20% at 50 µg/mL, 57.40 ± 2.42% at 100 µg/mL, 72.88 ± 2.83% at 150 µg/mL and 82.12 ± 2.71% at 200 µg/mL. The calculated C.D. of 3.818% reaffirmed the statistical significance of mortality differences, particularly at concentrations ≥ 100 µg/mL (Fig. 4b).

At 48 hpi, nematicidal activity reached peak levels in higher concentrations. The 200 µg/mL and 150 µg/mL ZnO-NP treatments recorded 92.28 ± 2.85% and 86.00 ± 3.06% mortality, respectively. In comparison, the fungal extract and 50 µg/mL ZnO-NPs remained less effective, showing 47.30 ± 2.10% and 55.50 ± 2.71% mortality, respectively. The C.D. value of 2.91% confirmed significant efficacy differences (Fig. 4c).

By 72 hpi, the 200 µg/mL and 150 µg/mL ZnO-NP treatments achieved maximum efficacy, resulting in 94.80 ± 3.02% and 90.94 ± 3.25% mortality, respectively. The 100 µg/mL group followed with 80.94 ± 3.59%, while fungal extract reached 53.82 ± 2.75%. Mortality in the untreated control remained consistently low (11.10 ± 0.75%), reaffirming the specific nematotoxic action of the test agents. The C.D. at 72 hpi was 4.018% and the coefficient of variation (CV) across time points ranged from 3.6% to 6.5%, indicating high reliability and reproducibility of the results (Fig. 4d).

Dose- and time-dependent larvicidal activity of ZnO nanoparticles against target organism. Box plots represent percent mortality observed at (a) 18 h, (b) 24 h, (c) 48 h and (d) 72 h, post-treatment with different concentrations of ZnO nanoparticles (Zn NPs: 50, 100, 150 and 200 µg/mL), fungal extract and negative control. Mortality rates increased significantly in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, with the highest mortality observed at 200 µg/mL ZnO NPs after 72 h exposure. Fungal extract alone exhibited moderate activity, while negative control groups showed minimal mortality throughout the experimental period. Data are presented as box plots indicating median, interquartile range and minimum/maximum values (n = 5 per group). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Metabolomic characterization of zinc nanoparticles synthesized using A. oligospora

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (^1H NMR) spectroscopy was employed to investigate the metabolomic profile of biosynthesized ZnO-NPs. The spectral analysis revealed seven distinct metabolites associated with the nanoparticle matrix, identified based on their characteristic chemical shifts (δ) and validated through the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) (Fig. 5; Table 1). The chemical shifts ranged from δ 2.1 to 3.9 ppm, encompassing multiple classes of bioactive compounds, including peptides, amino acids, vitamins, organic acids and nucleotide sugars.

The most prominent signal was attributed to Glycylproline (δ 3.9 ppm), a dipeptide (C7H12N2O2; MW 172.18 g/mol; HMDB0000899), suggesting the presence of peptide-rich residues on the nanoparticle surface, possibly contributing to nanoparticle capping and stabilization. Methionine (δ 2.1 ppm; HMDB0000696), a sulfur-containing amino acid, was also identified, indicating a potential role in redox-mediated nanoparticle synthesis.

Notably, vitamin B6 derivatives, including 4-Pyridoxate and Pyridoxine (δ 2.5 ppm; HMDB0002126 and HMDB0000209, respectively) and Riboflavin (vitamin B2, δ 2.6 ppm; HMDB0000244), were detected, pointing toward antioxidant activity and possible involvement in nanoparticle reduction pathways. The presence of these cofactors suggests that fungal metabolites participate in both nucleation and stabilization mechanisms.

Additionally, organic acids such as 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutarate (δ 2.4 ppm; HMDB0000651) and 3-Phenylpropionate (δ 2.9 ppm; HMDB0000661) were observed, both of which are intermediates in microbial metabolic cycles. A significant peak at δ 2.1 ppm corresponded to UDP-N-Acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc; C17H26N2O17P2; MW 607.35 g/mol; HMDB0001377), a nucleotide sugar involved in glycosylation and cell wall biosynthesis.

The presence of this diverse metabolite corona strongly suggests that the ZnO-NPs synthesized using A. oligospora are biofunctionalized with fungal-derived biomolecules. These metabolites may not only assist in nanoparticle stabilization but also contribute to the observed biological activities such as nematicidal efficacy, highlighting the synergy between nanomaterial and fungal bioactive compounds.

(a) 1H NMR spectra of A. oligospora-mediated ZnO nanoparticles. Full-range 1 H NMR spectrum of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized using the fungal filtrate of A. oligospora, recorded at 600 MHz in D2O. The spectrum displays characteristic proton resonances corresponding to organic moieties associated with the nanoparticle surface, confirming the presence of fungal biomolecules involved in nanoparticle stabilization and capping, (b) Expanded region of the1 H NMR spectrum (δ 4.5–0.5 ppm) highlighting the aliphatic and residual solvent peaks, providing further insight into the organic functional groups present on the nanoparticle surface. Acquisition and processing parameters are indicated on the right.

Molecular docking analysis of selected biomolecules against M. incognita target proteins

To explore the potential molecular targets of fungal-derived bioactive metabolites synthesized in A. oligospora-mediated ZnO nanoparticles, molecular docking was carried out against three essential proteins of Meloidogyne incognita: acetylcholinesterase (AChE), heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90), and odorant receptor 3 (ODR3). These proteins play indispensable roles in nematode physiology: AChE regulates neurotransmission and locomotor activity, Hsp90 ensures protein folding and stabilization under stress, and ODR3 functions as a chemosensory receptor critical for host recognition and environmental adaptation. Thus, inhibition of these proteins would compromise nematode survival, stress response, and infectivity. Importantly, metabolites such as riboflavin, uridine derivatives, amino acids, and aromatic compounds were previously identified in the NMR metabolite profile of A. oligospora-mediated ZnO nanoparticles. The docking studies were therefore undertaken to validate the nematicidal potential of these metabolites by assessing their ability to interact with and stabilize within the active sites of essential nematode proteins.

Homology-modeled protein structures were validated using standard quality parameters. AChE demonstrated excellent structural fidelity with an ERRAT score of 90.26, a Verify3D score of 79.25%, and a ProSA Z-score of − 10.16. Hsp90 and ODR3 were also reliable, with ERRAT scores exceeding 91 and Z-scores of − 8.47 and − 7.84, respectively, confirming their suitability for docking analysis.

Among the metabolites, riboflavin displayed strong multi-target activity. It bound to AChE with a docking score of − 7.8 kcal/mol (Fig. 6a–c), Hsp90 with − 7.4 kcal/mol (Fig. 6d–f), and ODR3 with − 7.1 kcal/mol (Fig. 6g–i). Riboflavin was stabilized within the active pockets through multiple hydrogen bonds, interacting with Thr114, Pro112, and Trp331 in AChE (Fig. 6c); Glu413, Lys420, Asp500, and Arg438 in Hsp90 (Fig. 6f); and Asn125, Lys74, and Tyr78 in ODR3 (Fig. 6i). The presence of such interactions at catalytically and structurally relevant residues suggests that riboflavin can disrupt enzyme activity and receptor function, thereby exerting a broad-spectrum inhibitory effect. Its docking scores, comparable to those of synthetic nematicides, highlight its potential as a natural neurotoxic and stress-modulating compound.

UDP-N-acetylglucosamine also demonstrated high binding affinity across the three targets. It showed the strongest interaction with AChE (− 8.3 kcal/mol; Fig. 7a–c), followed by Hsp90 (− 7.8 kcal/mol; Fig. 7d–f) and ODR3 (− 7.4 kcal/mol; Fig. 7g–i). UDP-N-acetylglucosamine engaged with critical residues, forming bonds with Glu273, Thr272, Ile355, and Arg418 in AChE (Fig. 7c); Glu501, Lys508, Gln505, and Tyr467 in Hsp90 (Fig. 7f); and Thr118, Ser86, Gln156, and Asn158 in ODR3 (Fig. 7i). These stable hydrogen-bonding and electrostatic interactions demonstrate that UDP-N-acetylglucosamine can effectively occupy the binding cavities, leading to functional inhibition of these proteins. Its high affinity for AChE, in particular, suggests a role in blocking neurotransmission and impairing nematode motility.

Other metabolites exhibited moderate to weak binding. 3-phenylpropionate, 4-pyridoxate, and glycylproline showed affinities ranging between − 5.3 and − 6.6 kcal/mol, with 3-phenylpropionate demonstrating preferential binding to ODR3 (− 6.2 kcal/mol), which may interfere with nematode chemoreception. Methionine, despite being part of the metabolic profile, displayed poor docking scores (− 4.0 to − 4.9 kcal/mol) across all proteins, suggesting a minimal direct inhibitory role.

Collectively, the docking analyses revealed that riboflavin and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine are the most promising metabolites in A. oligospora-mediated ZnO nanoparticles, showing strong, stable, and multi-target interactions. By simultaneously inhibiting proteins involved in neurotransmission, stress tolerance, and chemosensory signaling, these metabolites may exert synergistic inhibitory effects on M. incognita, underscoring their potential as eco-friendly bio-nematicidal agents. A comparative summary of the docking scores of all tested metabolites, alongside synthetic nematicides (carbofuran and fluopyram), is presented in Table 2.

Molecular docking of riboflavin with three target proteins: acetylcholinesterase (AChE), heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) and odorant receptor 3 (ODR3). Docking of riboflavin with AChE (magenta surface) (a–c), : (a) Surface representation of the AChE–riboflavin complex, (b) Close-up view of riboflavin within the AChE binding pocket, (c) 2D interaction map showing key amino acid residues interacting with riboflavin in AChE, Docking of riboflavin with HSP90 (yellow surface) (d–f): (d) Surface representation of the HSP90–riboflavin complex, (e) Close-up view of riboflavin within the HSP90 binding pocket, (f) 2D interaction map showing key amino acid residues interacting with riboflavin in HSP90, Docking of riboflavin with ODR3 (cyan surface) (g–i) : (g) Surface representation of the ODR3–riboflavin complex, (h) Close-up view of riboflavin within the ODR3 binding pocket, (i) 2D interaction map showing key amino acid residues interacting with riboflavin in ODR3.

Molecular docking of uridine diphosphate (UDP) with three target proteins: acetylcholinesterase (AChE), heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) and odorant receptor 3 (ODR3). Docking of UDP with AChE (magenta surface) (a–c): (a) Surface representation of AChE-UDP complex, (b) Close-up view of UDP in the AChE binding pocket, (c) 2D interaction map showing key amino acid residues interacting with UDP in AChE, Docking of UDP with HSP90 (yellow surface) (d–f): (d) Surface representation of HSP90-UDP complex, (e) Close-up view of UDP in the HSP90 binding pocket, (f) 2D interaction map showing key amino acid residues interacting with UDP in HSP90, Docking of UDP with ODR3 (cyan surface) (g–i): (g) Surface representation of ODR3-UDP complex, (h) Close-up view of UDP in the ODR3 binding pocket, (i) 2D interaction map showing key amino acid residues interacting with UDP in ODR3.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating the biosynthesis of ZnO-NPs using A. oligospora, offering an eco-friendly and efficient approach to develop bionematicidal agents. The successful formation of ZnO-NPs was confirmed through a comprehensive array of characterization techniques, affirming the nanomaterial’s structural, chemical and functional attributes. The biosynthesis of nanomaterials using fungi is gaining prominence due to its cost-effectiveness, scalability and the high stability of the resulting nanoparticles, as fungal extracellular enzymes and metabolites act as natural reducing and capping agents20. This work expands on the use of myco-synthesis for agricultural applications, showcasing A. oligospora as a novel bio-factory.

The UV–Vis absorption peak observed at 370 nm, slightly blue-shifted relative to bulk ZnO, is indicative of quantum confinement effects and confirms the nanoscale dimensions of the particles21. The sharp and narrow absorption band also reflects a high degree of monodispersity and reduced nanoparticle aggregation, hallmarks of a controlled biosynthetic process. This monodispersity is a crucial attribute, as nanoparticle size and aggregation state directly influence their bioavailability and toxicity, making a controlled green synthesis pathway highly desirable for field applications22.

FTIR spectral analysis further validated the involvement of fungal biomolecules in nanoparticle synthesis, with prominent peaks corresponding to O–H, N–H and C–O functional groups. These are typically associated with proteins, polysaccharides and other metabolites that function as reducing and capping agents23,24. Their role in metal ion chelation and stabilization facilitates a green synthesis pathway, minimizing environmental impact and enhancing biocompatibility. This observation is consistent with literature highlighting the critical role of these functional groups in mediating nanoparticle formation and stabilizing their surfaces, a process that ensures their longevity and activity in complex environmental matrices25.

Crystallinity was confirmed by XRD, which revealed characteristic diffraction peaks of the wurtzite hexagonal phase of ZnO, indexed to JCPDS card 36-1451. The dominance of the (002) plane implies anisotropic crystal growth, a trait beneficial for surface-mediated bioactivity26. Raman spectroscopy complemented XRD findings, with the E_2(high) phonon mode detected at 431.12 cm⁻¹, slightly red-shifted due to surface strain effects or molecular interactions with fungal-derived compounds27,28. The specific crystal orientation, especially the exposure of certain facets, can significantly enhance surface reactivity and interaction with biological targets29.

Morphological examination via SEM and TEM showed moderately polydisperse, roughly spherical nanoparticles with uneven surface textures typical for biologically synthesized nanostructures. TEM further revealed good dispersibility and size uniformity, indicating that fungal metabolites play a regulatory role in particle nucleation and growth. EDAX spectra confirmed the elemental purity of the nanomaterial, with strong signals for Zn and O and negligible impurities. The presence of a bio-corona, or a layer of fungal metabolites on the nanoparticle surface, likely influences this morphology and provides an added layer of functionalization30.

Compared to chemically synthesized ZnO-NPs, the present biogenic formulation exhibited improved nematicidal activity, possibly due to surface functionalization by fungal metabolites31. Biogenic ZnO-NPs demonstrated improved nematicidal activity against M. incognita32. These findings align with recent studies showing that biogenic nanoparticles often possess superior biological activity due to the synergistic effects of the inorganic core and the organic capping agents33. This synergy represents a major advancement over conventional single-mechanism chemical pesticides.

These physicochemical findings suggest a biosynthesis mechanism involving bio-complexation of Zn2+ ions with extracellular fungal proteins and metabolites, followed by reduction and subsequent stabilization through capping agents. The lack of toxic chemicals or high-temperature synthesis aligns this process with sustainable nanotechnological principles34,35. The biological efficacy of ZnO-NPs was significantly enhanced by the presence of bioactive fungal metabolites, as demonstrated in both mortality assays and docking studies. In nematicidal assays, ZnO-NPs displayed potent activity against M. incognita, with a pronounced dose- and time-dependent response. Mortality rates were significantly higher than those observed for fungal extract alone, particularly at 18, 36 and 72 hpi. At 72 hpi, ZnO-NPs achieved over 85% nematode mortality compared to 40–50% by fungal extract alone36.These results highlight the synergistic bioactivity of the nanoconjugate system.

The plausible modes of action include physical disruption of the nematode cuticle, intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and targeted delivery of embedded bioactive molecules37,38,39. The continuous generation of ROS by the ZnO-NPs is a well-established nematicidal mechanism, but the unique surface chemistry of the biogenic NPs likely enhances this effect, leading to overwhelming oxidative stress and subsequent cell death40. This multi-modal attack is particularly effective in preventing the development of pest resistance, a common challenge with single-target chemical agents.

Metabolomic profiling via ¹H NMR analysis identified several fungal-derived metabolites incorporated onto the nanoparticle surface. Compounds like glycylproline and methionine likely contribute to both structural stabilization and biological activity—glycylproline acting as a surfactant-like stabilizer, while methionine may promote nucleation via chelation of Zn2+ ions5,41. The presence of antioxidant vitamins such as riboflavin, pyridoxine and 4-pyridoxate suggests enhanced redox cycling, nanoparticle stability and possible biological activity42,43. Moreover, secondary metabolites like 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutarate and 3-phenylpropionate—known for membrane-permeabilizing and anti-inflammatory actions—may synergize with ROS effects to increase nematode susceptibility44. The notable detection of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine points to glycosylation potential, which could influence surface charge, biological targeting and environmental dispersion45,46.

These metabolite-nanoparticle interactions collectively form a natural “soft corona,” which modulates the biological identity of the ZnO-NPs. This corona likely enhances selective nematicidal activity while minimizing off-target toxicity, especially to beneficial soil organisms47,48. This functional corona may also confer stability under varying pH and soil ionic conditions, aiding field-level application49. The concept of a biogenic corona is a new and exciting area of research, suggesting a natural way to achieve targeted delivery and reduce off-target effects, a major limitation of current pesticide formulations50.

Molecular docking provided further mechanistic insights, revealing strong affinities of fungal metabolites for key nematode proteins. Riboflavin and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine exhibited high binding scores with AChE, Hsp90 and ODR3 proteins critical for neurotransmission, stress adaptation and sensory signaling51,52,53. Their interactions suggest a multitarget mode of action, which is advantageous in overcoming resistance development and ensuring long-term efficacy. Binding analysis revealed stable hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions between riboflavin and the catalytic pockets of these proteins, suggesting that the metabolite can effectively inhibit enzymatic function. Likewise, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine exhibited strong interaction with multiple residues in AChE, Hsp90 and ODR3, indicating specificity and potential for allosteric modulation.

The use of ZnO-NPs as a carrier platform enhances the delivery and stability of these metabolites, ensuring their penetration into nematode tissues and prolonging bioavailability. In addition to mechanical disruption and ROS induction, the metabolite–protein interactions suggest a biochemical mechanism of nematicidal action that is both potent and specific. This finding provides a solid foundation for the development of smart delivery systems for agrochemicals54.

In conclusion, the biosynthesized ZnO-NPs from A. oligospora represent a promising advancement in bionematicide technology. They combine structural precision, biocompatibility and multitarget efficacy against M. incognita, positioning them as sustainable alternatives to chemical nematicides. Future work should investigate nano-formulation strategies such as hydrogel encapsulation or granular embedding for slow release in soil ecosystems55,56. Field trials, ecotoxicological assays on earthworms and beneficial rhizobacteria and evaluation under variable soil types and climates will be critical for commercial deployment. With growing concerns over pesticide resistance and environmental degradation, such nanobiotechnological interventions offer a timely and scalable solution.

Conclusion

This study successfully demonstrates the green synthesis of ZnO NPs using A. oligospora, yielding a biologically functionalized nanomaterial with potent nematicidal activity. The ZnO NPs exhibited high crystallinity and purity (29.45–71.30 nm), with minimal aggregation, as confirmed by comprehensive physicochemical characterization. Notably, they induced up to 94.8% mortality of M. incognita juveniles at 200 µg/mL within 72 h.

Metabolomic profiling identified riboflavin and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine as key surface-bound fungal metabolites enhancing the bioefficacy of the nanoparticles. Riboflavin, through its redox-active isoalloxazine ring, likely promotes reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, exacerbating oxidative damage in nematodes. UDP-N-acetylglucosamine, a precursor in glycosylation and chitin biosynthesis, may interfere with nematode development and molting. Additional biomolecules such as amino acids, dipeptides and B-vitamins were also detected, contributing to nanoparticle stability and enhanced biocidal function.

In conclusion, A. oligospora-mediated ZnO NPs represent a promising, multifunctional tool for integrated nematode management. Their dual functionalization with riboflavin and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine suggests a novel mode of nematotoxicity that warrants further investigation in both molecular studies and field applications.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author, Professor R.K. Singh, upon reasonable request.

References

Jin, S. E. & Jin, H. E. Antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide nano/microparticles and their combinations against pathogenic microorganisms for biomedical applications: From physicochemical characteristics to Pharmacological aspects. Nanomaterials 11 (2), 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11020263 (2021).

Gomaa, E. Z. Microbial mediated synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles, characterization and multifaceted applications. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym Mater. 32 (11), 4114–4132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-022-02406-w (2022).

Gharpure, S. & Ankamwar, B. Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 20 (10), 5977–5996. https://doi.org/10.1166/jnn.2020.18707 (2020).

Islam, F. et al. Exploring the journey of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) toward biomedical applications. Materials 15 (6), 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15062160 (2022).

Siddiqi, K. S. & Husen, A. Fabrication of metal nanoparticles from fungi and metal salts: Scope and application. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 11, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1311-2 (2016).

Chauhan, A., Anand, J., Parkash, V. & Rai, N. Biogenic synthesis: A sustainable approach for nanoparticles synthesis mediated by fungi. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 53 (5), 460–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/24701556.2021.2025078 (2023).

Tijani, N. A. et al. Recent advances in Mushroom-mediated nanoparticles: A critical review of mushroom biology, nanoparticles synthesis, types, characteristics and applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 105695 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2024.105695 (2024).

Bahena-Nuñez, D. S. et al. A. oligospora (Fungi: Orbiliales) and its liquid culture filtrate myco-constituents kill Haemonchus contortus infective larvae (Nematoda: trichostrongylidae). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 34, 754–775. https://doi.org/10.1080/09583157.2024.2377607 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. Isolation, identification and evaluation of the predatory activity of Chinese arthrobotrys species towards economically important plant-parasitic nematodes. J. Fungi. 9 (12), 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9121125 (2023).

Jammor, P., Sanguanphun, T., Meemon, K., Promdonkoy, B. & Boonserm, P. Biosynthesis of Cry5B-loaded sulfur nanoparticles using A. oligospora filtrate: Effects on nematicidal activity, thermal stability and pathogenicity against caenorhabditis elegans. ACS Omega. 9 (6), 6945–6954. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c08653 (2024).

Feyisa, B. A review on RKNs (RKNs): Impact and methods for control. J. Plant. Pathol. Microbiol. 12 (4), 547. https://doi.org/10.35248/2157-7471.21.12.547 (2021).

Subedi, S., Thapa, B. & Shrestha, J. Root-knot nematode (M. incognita) and its management: A review. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. 3 (2), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.3126/janr.v3i2.32298 (2020).

Anjum, S., Vyas, A. & Sofi, T. Fungi-mediated synthesis of nanoparticles: Characterization process and agricultural applications. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 103 (10), 4727–4741. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.12496 (2023).

Gautam, V. et al. Exploring the rice root metabolome to unveil key biomarkers under the stress of M. incognita. Plant. Stress. 14, 100620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2024.100620 (2024).

Gautam, V. et al. Harnessing NMR technology for enhancing field crop improvement: Applications, challenges and future perspectives. Metabolomics 21 (27). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11306-025-02229-z (2025).

Gautam, V. et al. Characterizing metabolic changes in rice roots induced by M. incognita and modulated by A. oligospora: A pathway-based approach. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 136, 102541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmpp.2024.102541 (2025b).

Singh, R. K., Kumar, N. & Singh, K. P. Morphological variations in conidia of A. oligospora on different media. Mycobiology 33 (2), 118–120. https://doi.org/10.4489/MYCO.2005.33.2.118 (2005).

Hefny, M. E., El-Zamek, F. I., El-Fattah, H. I. A. & Mahgoub, S. A. Biosynthesis of zinc nanoparticles using culture filtrates of Aspergillus, fusarium and penicillium fungal species and their antibacterial properties against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Zagazig J. Agricultural Res. 46 (4), 2009–2021. https://doi.org/10.21608/zjar.2019.51920 (2019).

Sharma, J. L., Dhayal, V. & Sharma, R. K. White-rot fungus mediated green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles and their impregnation on cellulose to develop environmental friendly antimicrobial fibers. 3 Biotech. 11 (269). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205021-02840-6 (2021).

Yang, H. et al. Antagonistic effects of talaromyces muroii TM28 against fusarium crown rot of wheat caused by fusarium pseudograminearum. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1292885. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1292885 (2024).

Ahmed, T. & Edvinsson, T. Optical quantum confinement in ultrasmall ZnO and the effect of size on their photocatalytic activity. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 6395–6404. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b11229 (2020).

da Silva, B. L. et al. Increased antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles: Influence of size and surface modification. Colloids Surf., B. 177, 440–447 (2019).

Philip, D. Biosynthesis of Au, ag and Au–Ag nanoparticles using edible mushroom extract. Spectrochim. Acta A. 73 (2), 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2009.02.037 (2009).

Honary, S., Barabadi, H. & Gharaei-Fathabad, E. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles induced by the fungus Penicillium citrinum. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 12, 7–11. https://doi.org/10.4314/TJPR.V12I1.2 (2013).

Ahmad, F. et al. Unique properties of surface-functionalized nanoparticles for bio-application: Functionalization mechanisms and importance in application. Nanomaterials 12 (8), 1333 (2022).

Worasawat, S. et al. Growth of ZnO nano-rods and its photoconductive characteristics on the photo-catalytic properties. Mater. Today Proc., 17, 1379–1385. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2019.06.158

Popović, Z. B., Dohcevic-Mitrovic, Z., Šćepanović, M. J., Grujić-Brojčin, M. & Aškrabić, S. Raman scattering on nanomaterials and nanostructures. Ann. Phys. 523. https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.201000094 (2011).

Lorite, I., Romero, J. J. & Fernandez, J. F. Influence of the nanoparticles agglomeration state in the quantum-confinement effects: Experimental evidences. AIP Adv. 5 (3), 037105. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4914107 (2015).

Tang, J., Hao, J., Wang, X., Niu, L., Zhu, N., Li, Z., Jiang, G. (2025). Mechanisms for facet-dependent biological effects and environmental risks of engineered nanoparticles: A review. Environ. Sci. Nano.

Ahsan, S. M., Rao, C. M. & Ahmad, M. F. Nanoparticle-protein interaction: The significance and role of protein Corona. Cellular Mol. Toxicol. Nanoparticles, 175–198. (2018).

Shamim, A., Mahmood, T. & Abid, M. B. Biogenic synthesis of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles using a fungus (Aspargillus niger) and their characterization. Int. J. Chem. 11 (2), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijc.v11n2p119 (2019).

Kalaba, M. H. et al. Green synthesized ZnO nanoparticles mediated by Streptomyces plicatus: Characterizations, antimicrobial and nematicidal activities and cytogenetic effects. Plants 10 (9), 1760. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10091760 (2021).

Chauhan, A., Anand, J., Parkash, V. & Rai, N. Biogenic synthesis: A sustainable approach for nanoparticles synthesis mediated by fungi. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 53 (5), 460–473 (2023).

Parveen, K., Banse, V. & Ledwani, L. Green synthesis of nanoparticles: Their advantages and disadvantages. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 1724, No. 1). AIP Publishing. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4945168

Šebesta, M. et al. Mycosynthesis of metal-containing nanoparticles—Fungal metal resistance and mechanisms of synthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (22), 14084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232214084 (2022).

El-Ansary, M. S. M., Hamouda, R. A. & Elshamy, M. M. Using biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles as a pesticide to alleviate the toxicity on banana infested with parasitic-nematode. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 13 (1), 405–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-021-01527-6 (2022).

Ahmad, S. et al. Green Nano-synthesis: Salix Alba Bark-Derived zinc oxide nanoparticle and their nematicidal efficacy against RKN meloidogyne incognita. Advancements Life Sci. 10 (4), 675–681. https://doi.org/10.62940/als.v10i4.1581 (2024).

Qais, F. A., Khan, M. S., Ahmad, I. & Althubiani, A. S. Potential of nanoparticles in combating Candida infections. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery. 16 (5), 478–491. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570180815666181015145224 (2019).

Molina-Hernández, J. B. et al. Synergistic antifungal activity of Catechin and silver nanoparticles on Aspergillus Niger isolated from coffee seeds. Lwt 169, 113990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113990 (2022).

Chaudhary, R. G. et al. Metal/metal oxide nanoparticles: Toxicity, applications and future prospects. Curr. Pharm. Design. 25 (37), 4013–4029 (2019).

Bondžić, A. M. et al. Soft protein Corona as the stabilizer of the methionine-coated silver nanoparticles in the physiological environment: Insights into the mechanism of the interaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (16), 8985. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23168985 (2022).

Chaudhuri, S. et al. Sensitization of an endogenous photosensitizer: Electronic spectroscopy of riboflavin in the proximity of semiconductor, insulator and metal nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. A. 119 (18), 4162–4169. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.5b03021 (2015).

Manoj, D. et al. Engineering ZnO nanocrystals anchored on mesoporous TiO2 for simultaneous detection of vitamins. Biochem. Eng. J. 186, 108585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2022.108585 (2022).

Park, J. B. Methyl 2-[3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-enoylamino]-3-phenylpropanoate is a potent cell-permeable anti-cytokine compound to inhibit inflammatory cytokines in monocyte/macrophage-like cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.123.001830 (2023).

Eissa, A. M., Abdulkarim, A., Sharples, G. J. & Cameron, N. R. Glycosylated nanoparticles as efficient antimicrobial delivery agents. Biomacromolecules 17 (8), 2672–2679. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00711 (2016).

Chen, Y. H. & Cheng, W. H. Hexosamine biosynthesis and related pathways, protein N-glycosylation and O-GlcNAcylation: Their interconnection and role in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1349064. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1349064 (2024).

Marslin, G. et al. Secondary metabolites in the green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles. Materials 11 (6), 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11060940 (2018).

Shannahan, J. The biocorona: A challenge for the biomedical application of nanoparticles. Nanatechnol. Reviews. 6 (4), 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2016-0098 (2017).

Ho, Y. T. et al. Protein Corona formed from different blood plasma proteins affects the colloidal stability of nanoparticles differently. Bioconjug. Chem. 29 (11), 3923–3934. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00743 (2018).

García-Álvarez, R. & Vallet-Regí, M. Hard and soft protein Corona of nanomaterials: Analysis and relevance. Nanomaterials 11 (4), 888 (2021).

Xiong, H. M. ZnO nanoparticles applied to bioimaging and drug delivery. Adv. Mater. 25 (37), 5329–5335. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201301732 (2013).

Huang, C. W., Li, S. W. & Liao, V. H. C. Long-term sediment exposure to ZnO nanoparticles induces oxidative stress in caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Science: Nano. 6 (8), 2602–2614. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9EN00039A (2019).

Nagaraj, G., Kannan, R., Raguchander, T., Narayanan, S. & Saravanakumar, D. Nematicidal action of Clonostachys rosea against M. incognita: In-vitro and in-silico analyses. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 18 (1), 2288723. https://doi.org/10.1080/16583655.2023.2288723 (2024).

Qiao, H., Chen, J., Dong, M., Shen, J. & Yan, S. Nanocarrier-based eco-friendly RNA pesticides for sustainable management of plant pathogens and pests. Nanomaterials 14 (23), 1874 (2024).

Mandal, M., Singh Lodhi, R., Chourasia, S., Das, S. & Das, P. A review on sustainable slow-release N, P, K fertilizer hydrogels for smart agriculture. ChemPlusChem 90 (3), e202400643. https://doi.org/10.1002/cplu.202400643 (2025).

Campos, E. V. R., de Oliveira, J. L., Fraceto, L. F. & Singh, B. Polysaccharides as safer release systems for agrochemicals. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35 (1), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-014-0263-0 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Department of Plant Pathology, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, for providing the necessary laboratory facilities and academic support throughout the study. Special thanks to the Sophisticated Analytical and Technical Help Institute (SATHI), Banaras Hindu University for providing access to the NMR facility, which was instrumental in metabolite characterization. The authors also acknowledge the support and cooperation extended by the faculty and staff during the execution of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Vedant Gautam was the major contributor in conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, and writing of the original draft, as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript. Vibhootee Garg performed software-related tasks, molecular docking analysis, and validation. Nitesh Meena contributed to investigations, data curation, and assisted in methodology. Anand Hivre Dashrath was responsible for biochemical analyses, laboratory support, and validation. Kaminee Singh handled nanoparticle synthesis and laboratory assistance. Abhishek Kumar contributed to nanoparticle synthesis, data interpretation, and review and editing of the manuscript. Ashish Kumar provided critical review, technical support, and visualization. R.K. Singh supervised the work and was responsible for conceptualization, project administration, funding acquisition, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gautam, V., Garg, V., Meena, N. et al. Fungal-derived ZnO nanoparticles functionalized with riboflavin and UDP-GlcNAc exhibit potent nematicidal activity against M. incognita. Sci Rep 15, 38427 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22170-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22170-4