Abstract

The growing use of indoor localization systems (ILS) in essential applications, including healthcare, smart buildings, and logistics, has created serious security and privacy concerns. This paper thoroughly analyzes the existing security and privacy concerns in ILS, emphasizing risks such as spoofing, signal jamming, and adversarial attacks. We explore defense strategies, such as federated learning, adversarial machine learning, and cryptographic protocols, emphasizing their efficacy and constraints. The study examines the trade-offs among privacy, accuracy, and efficiency in ILS while tackling significant difficulties such as non-Independent and Identically Distributed (non-IID) data, energy efficiency, and scalability in practical applications. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the state of the art in protecting ILS against growing adversarial threats by integrating major trends and approaches from the last five years. This survey paper will help researchers and industry professionals gain a deeper understanding of privacy and security concerns in ILS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Location-based services (LBS) are applications that deliver location-specific information regarding a user or device via mobile devices or communication networks. Recent years have seen an increase in demand due to their broad range of applications, which include navigation, mapping, social networking, targeted advertising, virtual reality, healthcare, transportation, smart cities, and gaming1. While outdoor localization largely depends on global navigation satellite systems (GNSS), many emerging services require accurate positioning indoors, where GNSS is unreliable. Indoor Localization Systems (ILS) fulfill this requirement by utilizing several technologies, including frequency modulation (FM), amplitude modulation (AM), Bluetooth, global system for mobile communications (GSM), Wi-Fi, and long-term evolution (LTE)2,3.

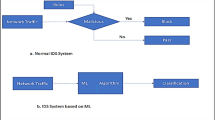

Localization fundamentally involves determining the position of an object or individual in relation to reference points (RP) within a specified indoor environment4, as depicted in Fig. 1, which emphasizes the difference between indoor and outdoor methodologies. The increasing dependence on ILS in essential sectors, such as healthcare, smart infrastructure, logistics, and emergency response, highlights the necessity for dependable, secure, and privacy-respecting systems. Indoor locations present distinct issues, including signal blockage, multipath effects, and vulnerability to malicious interference. Security threats such as signal spoofing and jamming, along with privacy risks like unauthorized tracking, can result in significant real-world repercussions. It is therefore essential to understand and address these threats, which highlight the importance of a comprehensive review of existing vulnerabilities, defense mechanisms, and future research directions in this evolving field.

The study distinguishes itself from others5,6,7 by providing a comprehensive examination of security and privacy concerns in ILS, something that is frequently overlooked in previous research. Numerous present assessments concentrate on security concerns or privacy troubles, although seldom do they examine the combination of both. Our analysis underscores the imperative for a dual approach, particularly in response to rising threats such as signal spoofing, jamming, and data privacy violations. This report highlights recent trends and offers a current view of the growing environment of ILS, including developments in FL and AML as defensive strategies. Unlike prior studies that narrow their scope to specific technologies, our paper broadens the scope by analyzing the latest developments across diverse ILS applications, providing insights into both attack prevention and defense mechanisms, and identifying gaps in the literature. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

-

Comprehensive literature synthesis We provide a structured and up-to-date review of recent developments (2020–2025) in ILS security and privacy, emphasizing the interplay between threats such as spoofing, jamming, and data breaches, which are often treated separately in prior surveys.

-

Methodological integration of defense paradigms This study uniquely integrates discussions on federated learning (FL), adversarial machine learning (AML), and cryptographic protocols, offering a comparative analysis of their effectiveness and limitations across varied ILS scenarios.

-

Evaluation of privacy–utility trade-offs We critically examine the trade-offs between privacy, accuracy, and computational efficiency in decentralized ILS architectures, offering insights into real-world applicability and constraints that are often overlooked in more theoretical studies.

-

Identification of open challenges and research Ddrections The study highlights unresolved issues such as non-IID data handling, scalability limitations, and energy efficiency bottlenecks. Based on these, we propose concrete future research directions to support the design of more secure and privacy-preserving ILS frameworks.

While several prior reviews have discussed either security or privacy in indoor localization systems, few studies have offered an integrated perspective that systematically addresses both concerns in tandem. This gap is particularly significant given the increasing interdependence between privacy-preserving mechanisms and security defenses in real-world ILS deployments. Existing literature has tended to focus on isolated technical challenges–such as specific attack types, encryption techniques, or signal interference–but has often lacked a comprehensive view that maps these threats to emerging defensive strategies like federated learning and adversarial machine learning. In response, this study presents a structured and up-to-date synthesis of both vulnerabilities and countermeasures in ILS, covering technological trends from 2020 to 2025. Methodologically, this review differs from past works by bridging siloed research areas and offering a comparative analysis of ILS privacy and security solutions across a range of practical application scenarios. By doing so, it not only identifies unresolved challenges but also outlines future research directions to guide the development of robust and privacy-aware indoor localization architectures.

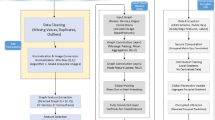

To conduct this comprehensive review, we systematically searched leading academic databases, including IEEE Xplore, Scopus, and Web of Science, for peer-reviewed journal and conference papers published between 2020 and 2025. Keywords such as indoor localization, privacy, security, federated learning, and adversarial machine learning guided our search. We included articles that specifically addressed either security or privacy concerns or both within the context of Indoor Localization Systems (ILS). Studies that focused exclusively on hardware-level improvements or unrelated positioning technologies were excluded. We restrict the time window to 2020–2025 to capture the rapid shift toward FL/AML and cryptographic defenses during these years, provide a coherent and up-to-date scope, and complement–rather than duplicate–pre-2020 surveys. For the detailed eligibility rules and screening workflow, see “earch Strategy and Eligibility Criteria”Section.

As a survey paper, this study aims to synthesize and evaluate existing research, without proposing new algorithms or experiments. Selected articles were analyzed and categorized based on attack types, defense mechanisms, and system architectures, as illustrated in Fig. 3, to support a structured exploration of current trends and open challenges in the field.

Unlike prior surveys, this work integrates recent advances and organizes threats and solutions using a taxonomy aligned with AI-driven and cryptographic methodologies, offering a novel perspective on the dual challenge of privacy and security in ILS.

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

To enhance transparency and reproducibility, we specify the eligibility rules governing study selection and outline the screening workflow used to assemble the final corpus. A concise summary appears in Table 1.

Inclusion criteria (all must be satisfied).

-

1.

Peer-reviewed journal or conference papers published during 2020-2025.

-

2.

English-language publications.

-

3.

Full text available.

-

4.

Studies focused on ILS that analyze security and/or privacy (e.g., threats, defenses, trade-offs).

-

5.

Study designs including empirical evaluations, simulations, algorithmic/framework proposals, or surveys that substantively address ILS security or privacy.

Exclusion criteria (any single criterion is sufficient for exclusion)

-

1.

Works focused exclusively on hardware-level improvements with no ILS security/privacy analysis.

-

2.

Studies on outdoor-only localization or otherwise unrelated positioning technologies.

-

3.

Non–peer-reviewed items (e.g., theses, patents, white papers), abstracts without full text, or non-English publications.

Screening workflow Records aggregated from the selected bibliographic sources were first deduplicated. We then conducted title/abstract screening against the eligibility rules above, followed by a full-text assessment of the remaining candidates. For transparency, reasons for exclusion were documented at the full-text stage. The subsequent taxonomy and synthesis consider only studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section "Fundamentals of indoor localization systems" covers the basics of ILS, including their kinds, range methods, and localization algorithms. Section "Related work" summarizes current ILS security and privacy assessments and research. Section "Comparative study of privacy and security approaches in ILS" examines the strengths, weaknesses, and current trends of ILS security solutions and highlights key issues. Section "Security and privacy concerns in ILS" discusses ILS security and privacy issues, including spoofing and jamming attacks and their consequences. Section "Machine learning techniques for enhancing security and privacy in ILS" discusses the AI techniques that can be used for enhancing ILS privacy and security. Section "Discussion and synthesis of findings" synthesizes the findings from the previous sections by categorizing security and privacy techniques along the dimensions of effectiveness, scalability, and real-world applicability. Finally, sect. "Research gaps and future directions" provides a comprehensive discussion of gaps and future directions in the ILS study. Finally, sect. "Conclusion" concludes the paper by summarizing the findings and suggesting future research directions to improve ILS security and privacy. For a complete structure of this paper, refer to Fig. 2.

Fundamentals of indoor localization systems

Before delving into privacy and security challenges related to ILS, let us briefly look into these systems. ILS estimates the position of a target continuously in an indoor environment by first applying a distance estimation algorithm using different ranging techniques, followed by a localization algorithm8. To offer a structured understanding of the security and privacy landscape in ILS, Fig. 3 presents a taxonomy that categorizes the common threat types, corresponding defense mechanisms (e.g., federated learning, adversarial training, cryptographic solutions), and deployment models. This taxonomy serves as a conceptual anchor for the techniques reviewed in subsequent sections.

Types of indoor localization

Indoor environments are diverse, and each indoor environment requires ILS tailored to its needs in terms of accuracy and coverage. For example, ambient assisted living applications require room-level coverage with an accuracy of less than one meter, while law enforcement requires urban or rural coverage with an accuracy of a few meters. Because of these diverse needs, there is no single solution to indoor localization; different localization techniques coexist. Indoor localization can broadly be divided into two categories: active localization and passive localization. A more detailed sub-classification of active and passive localization techniques is shown in a flow chart in Fig. 4.

Active localization

Active localization is ideal for application that require high accuracy like asset tracking, robot navigation, etc., but demands users to carry a tag or device like a mobile phone, smartwatch, etc. Some of the techniques used for active detection include computer vision (CV)9, light detection and ranging (LIDAR)10,11,12, ultrasound13, acoustic14,15, geometric fingerprinting16, wireless or radio frequency (RF)17, visible light18, and aroma fingerprinting19,20.

Passive localization

Unlike active localization, passive localization suitable for scenarios like occupancy detection, with limitations in precision is due to the lack of active tags. Some of the applications of passive detection are intrusion detection, fall detection, remote monitoring, emergency evacuation, business analytics, accessibility aids for the visually impaired21, etc. The techniques used in passive localization include camera- or vision-based localization22,23, RF-based localization24, visual light-based localization25,26, infrared-based localization27,28, physical excitation21, and electric field sensing13,29.

Ranging techniques

Ranging techniques in ILS are different methods used to measure the distance between devices, such as beacons, sensors, or access points (AP), and a target object that could be a mobile device or person. These techniques are essential for determining the location of a target in an indoor environment. Different ranging techniques are used for ILS in the literature (Fig. 5); some of the common ones include the following:

Phase of arrival (PoA)

PoA is a ranging technique in which the phase difference of a signal that is received at multiple antennas or from multiple transmitters is measured. The phase information in PoA is used to estimate the target location. Although PoA can provide high accuracy, especially in environments with limited multipath path effects, it is challenging because it requires precise measurement and is sensitive to environmental factors and frequency offset30,31.

The PoA is estimated by evaluating the phase difference of the signal received at various antennas. Mathematically, the phase difference \(\Delta \phi\) between the two antenna positioned at a distance \(d\) is represented as

where, \(\theta\) is the angle of arrival of the signal, \(\lambda\) represents the wavelength of the signal, and \(d\) denotes the distance between the antennas. The angle of arrival, \(\theta\), can be approximated using the measured phase difference \(\Delta \phi\):

The approximated phase can then be used to determine the target’s position in either a two or three dimensional space. The effectiveness of this method depends upon the accurate measurements and careful calibration, which help mitigate influences such as frequency offset and environmental noise. Although PoA provides high accuracy in controlled settings, its susceptibility to noise, frequency offsets, and calibration issues limits its practicality in dynamic or large-scale applications.

Angle of arrival (AoA)

Angle of arrival (AoA) is a method that measures the direction from which a signal reaches the receiver. This method triangulates the target location by combining multiple AoAs from different receiver locations. AoA provides high accuracy, especially when directional antennas are used. However, it requires specialized hardware and can be affected by multipath interference32. In practice, the AoA technique determines the angle \(\theta\) of the incoming signal at each receiver, which can be calculated using the coordinates of the transmitter \((x_t, y_t)\) and the receiver \((x_r, y_r)\).

Several receivers with known positions are employed to determine the transmitter’s location through triangulation. Using the AoA information \(\theta _i\) at receiver \(i\), the lines of bearing (LoB) can be described as

\((x_{r_i}, y_{r_i})\) denotes the coordinates of the \(i\)-th receiver. The intersection of these LoBs from various receivers yields the estimated location of the transmitter \((x_t, y_t)\). In actual situations, noise and multipath effects can distort AoA readings, requiring error minimization strategies to enhance the accuracy of the estimated position.

Although AoA is highly accurate, it is especially susceptible to multipath effects. Additionally, the requirement for specialized directional antennas and noise reduction techniques can make its deployment in real-world situations more complex.

Signal propagation time

In the signal propagation time technique, the distance between the target and a reference point (RP) with a known location is estimated by measuring the time it takes for a signal to arrive between them. Based on this principle, two common techniques are used, namely time of arrival (ToA) and time difference of arrival (TDoA). ToA provides high accuracy in line of sight (LOS) environments but its performance decreases in no line of sight (NLOS) scenarios due to the multi-path effect and signal reflection33. A major challenge in ToA is the need for accurate time synchronization between the transmitter and receiver, which TDoA addresses. However, TDoA requires multiple receivers and the use of complex algorithms to estimate the target location, which introduces its own difficulties.

In the ToA method, the distance \(d\) between the transmitter and receiver is calculated as

where \(c\) is the speed of light (or more generally, the signal propagation velocity in a medium), and \(t\) represents the measured signal propagation duration. This equation presumes that the signal propagates on a linear trajectory without considerable delays caused by obstructions.

The TDoA technique uses the time difference of arrival (\(\Delta t\)) between two receivers at known locations to calculate the difference in distances (\(\Delta d\)) from the target to these receivers, expressed as \(\Delta d = c \cdot \Delta t\). Here, \(\Delta t\) represents the time difference between the signals reaching the two receivers, defined as \(\Delta t = t_2 - t_1\), where \(t_1\) and \(t_2\) denote the arrival times at the first and second receivers, respectively. The target’s location is determined by integrating several measurements through trilateration or other geometric methods.

ToA and TDoA perform well under ideal line-of-sight conditions, but their accuracy decreases in non-line-of-sight environments. Beyond classical multilateration, a recent approach couples propagation modeling with a genetic algorithm to efficiently explore the position space and improve indoor localization under multipath constraints34.

Received signal strength indicator (RSSI)

RSSI, as the name suggest, is a measure of the real signal power received by the receiver. It is calculated in decibel milliwatts (dBm) or milliwatts (mW)35. The RSSI technique estimates the distance between the transmitter and receiver based on the strength of the received signal. As the distance between the devices increases, the signal strength decreases, which is used to approximate the distance between them.

The received signal strength (RSS) is represented by the path loss equation:

where \(P_r(d)\) represents the received power at a distance \(d\) (in \(dBm\)), \(P_t\) denotes the transmitted power (in \(dBm\)), \(n\) signifies the path loss exponent (typically ranging from 2 to 4 in indoor environments), \(d\) indicates the distance between the transmitter and receiver (in meters), and \(X_g\) refers to the Gaussian noise that accounts for environmental factors (e.g., obstacles and interference). The estimated distance \(\hat{d}\) can be computed using the following equation:

RSSI based localization is easy to implement without requiring complex hardware or calculations. Another advantage of RSSI is that they are inexpensive and are widely supported by existing wireless technologies like Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. Accuracy of RSSI is directly influenced by environmental factors like obstacles, interference, and multi-path propagation36. Compared to other techniques RSSI is generally less accurate, especially in complex indoor environments.

RSSI provides ease of use and cost benefits; however, it faces challenges with accuracy in areas with many obstacles or interference, which reduces its reliability for accurate indoor localization.

Frequency modulated continuous wave (FMCW)

FMCW is a technique in which a continuous waveform is transmitted along with its frequency modulation over time. The transmitted signal can be represented as

where \(A\) denotes the amplitude of the signal, \(f_0\) represents the initial frequency, and \(k = \frac{B}{T}\) represents the chirp rate, with \(B\) indicating the bandwidth and \(T\) the duration of the chirp. This signal reflects off an object and is received by the system. The received signal, delayed by the duration \(\tau\), is expressed as

The system estimates the frequency shift \(f_\Delta\), defined as the difference between the transmitted and received signals. The frequency shift is expressed as

where \(\tau = \frac{2R}{c}\) denotes the round-trip time delay, \(R\) represents the distance from the transmitter to the object, and \(c\) signifies the speed of light. Hence, the distance \(R\) to the item can be calculated using the formula:

FMCW is a versatile technique that supports both short- and long-range sensing, making it suitable for a wide range of indoor applications37. While it offers high accuracy, its performance is sensitive to environmental factors and relies on advanced signal processing and sophisticated hardware. These requirements increase system cost and complexity, limiting its feasibility for large-scale or cost-sensitive deployments38.

Channel state information (CSI)

CSI is an advanced technique for measuring distance in ILS. CSI holds detailed data about the propagation characteristics of a wireless communication channel like Wi-Fi. It includes information regarding the variations in signal as it passes through an environment, which can be affected by factors like walls, furniture, and people moving around39. CSI provides more precise data compared to traditional RSSI data which allows for a more accurate localization, device tracking, and environment sensing.

The CSI captures the frequency response of the channel, mathematically expressed as

where \(H(f)\) denotes the complex channel frequency response at frequency \(f\), \(|H(f)|\) represents the amplitude response, and \(\phi (f)\) indicates the phase response. The received signal can be expressed with the CSI as follows:

In the frequency domain, \(Y(f)\) denotes the received signal, \(X(f)\) signifies the broadcast signal, \(H(f)\) represents the CSI, and \(N(f)\) indicates noise. In a multipath environment, where signals arrive at the receiver via multiple routes, the CSI is generally represented as

where \(L\) denotes the number of propagation paths, \(\alpha _i\) signifies the amplitude attenuation of the \(i\)-th path, and \(\tau _i\) indicates the propagation delay of the \(i\)-th path.

CSI provides exceptional accuracy and depth in localization data through its comprehensive channel measurements. However, its substantial computational demands and sensitivity to environmental changes pose considerable challenges for real-time and resource-limited applications.

Localization algorithms

Indoor localization algorithms are used to determine the position of a target object based on factors like RSSI, CSI, ToA, etc. These algorithms are broadly classified as follows:

Proximity-based algorithms

Proximity-based localization algorithms determine the location of a device by measuring its closeness to some known fixed point40. Bluetooth beacons are a common proximity-based approach that measures device closeness by measuring the strength of the signals from the beacons set at known locations. This method is commonly implemented in indoor environments. Near-field communication (NFC) is another example of a proximity-based algorithm in which the location of the device is determined by directly interacting with NFC tags that are embedded in the area of interest.

Triangulation-based algorithms

Triangulation-based algorithms utilize the geometric relationship between the known RP or anchor. It includes methods like lateration13, which determines the target distance from multiple anchors to calculate its location. TDoA and ToA are examples of lateration, which improves localization accuracy using signal travel times. Angulation (or AoA) is another triangulation-based algorithm that estimates the target location using the measure of the angle of the signal arriving from multiple anchors. Both lateration and angulation are widely used methods, and they balance accuracy and computational requirements based on the indoor environment and infrastructure.

Dead reckoning

Dead reckoning, though a navigation method, can be used for indoor localization. It estimates the current position of the target using previously known locations, along with its velocity measurement and direction of movement. Dead reckoning is sensitive to error accumulation over time41; hence, it is often combined with other localization techniques to improve its accuracy.

Trilateration/multilateration

Trilateration and multilateration are techniques that find an unknown node by using three (in the case of trilateration) or more (in the case of multilateration) reference nodes. In trilateration, the position of the target node is determined by finding the intersection of three imaginary circles that are centered at the reference nodes42.

Magnetic field-based localization

In the magnetic field-based localization algorithm, distortions in the earth’s magnetic field are used to pinpoint locations43. This distortion in the magnetic field is caused by the structural elements of the buildings. Magnetic field-based localization involves creating detailed maps of the indoor environment’s magnetic field, which are then used as references in indoor localization.

Range-free

Range-free localization algorithms are methods that do not rely on distance or angle measurements to predict the position of the target and are used in wireless sensor networks (WSNs). Range-free localization algorithms use, instead, the connectivity information to infer the relative position of nodes in a network. Common range-free algorithms include distance vector-hop (DV-Hop)44, centroid localization, approximate point-in-triangulation (APIT), and multidimensional scaling mapping (MDS-MAP).

Machine learning (ML)-based algorithms

ML-based algorithms use methods like neural networks, like deep neural networks (DNNs), convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), to improve localization accuracy by learning from a large dataset35. These neural networks effortlessly model complex relationships between the signal features and specific location coordinates. Support vector machines (SVMs) are another ML algorithm used for localization problems due to their robust classification capabilities. SVMs efficiently determine the position based on different signal attributes.

Fingerprinting

Fingerprinting in indoor localization is the process of creating a radio map (database) of signal characteristics like RSSI and CSI at multiple locations in the area of interest45. This radio map is used as a reference to match the current signal measurements with those in the database and predict the location based on this comparison. The most popular method, Wi-Fi fingerprinting, uses RSSI data from many APs to estimate the device location. Another method of fingerprinting is RFID fingerprinting, which builds complex signal maps using RFID tags and readers, allowing for more accurate localization (Fig. 6).

Related work

ILS security and privacy surveys and case studies are reviewed in this section, highlighting key findings and limitations. It includes case studies and real-world applications in indoor localization from 2020 to 2025.

Existing surveys and reviews

Recent surveys on ILS have explored various aspects of security and privacy, yet gaps remain in their coverage and depth. Early reviews, such as46, provided a foundational categorization of privacy concerns–device, transmission, and server-level–but their relevance is limited due to outdated datasets. More recent works have examined the intersection of machine learning and IoT security47, as well as the broader landscape of indoor/outdoor localization in IoT42. Studies focusing on specific technologies, like BLE in wearable devices48, and deep learning-based approaches using Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and UWB49, highlight ongoing challenges such as multipath interference, data scarcity, and environmental noise. While these surveys contribute valuable insights, particularly on hybrid techniques and device-free localization, standardization and efficiency remain critical concerns. More recent efforts7 have introduced structured classifications based on collaboration and security principles but offer limited treatment of privacy-preserving methods. Privacy-specific surveys5,50 have begun to explore novel attack models and protection strategies in location fingerprinting, though their scope is often narrow and lacks comprehensive analysis. Overall, existing literature reveals a fragmented approach to privacy in ILS, underscoring the need for more integrative and up-to-date reviews. For a cutting-edge 2025 synthesis of AI–cybersecurity fusion trends–spanning FL, AML, privacy mechanisms, and policy directions–see51, which complements our ILS-focused review. Given that several pre-2020 surveys are limited or outdated with respect to modern datasets and techniques, our review focuses on 2020–2025 to provide an up-to-date synthesis that complements these earlier works.

Evolution of security and privacy techniques in indoor localization

2020

Several studies have explored privacy and security concerns in indoor positioning systems (IPS), particularly the handling of sensitive user data and resilience against adversarial behavior. Barsocchi et al.52 propose a GDPR-compliant, privacy-by-design framework for location-based services, demonstrated through a Telegram-based proximity marketing application. While the architecture supports regulatory compliance, it remains limited in scope and reveals ongoing vulnerabilities in data protection. Addressing malicious data manipulation, Li et al.53 introduce the ACTD framework, which employs machine learning and outlier detection to identify anomalous RSS fingerprint submissions. Although effective in simulations, the lack of real-world validation limits its practical reliability. To counter fraudulent check-ins, Li et al.54 present an AP subset selection strategy that optimizes positioning accuracy and robustness; however, the method is sensitive to environmental variation, computationally demanding, and may struggle with emerging threats. Expanding on this, Li et al.55 propose a boundary-based defense using fingerprint refinement and level-set methods to improve localization security. Despite promising simulated results, its effectiveness remains constrained by untested assumptions and partial mitigation of attack vectors.

Building on these efforts to strengthen IPS resilience, Yang et al.56 focus on secure state estimation under sensor attacks, where measurements can be manipulated even with protected communication channels. Their map-based localization algorithm ensures robust estimation against such threats, though practical deployment under diverse attack scenarios remains unexplored. To address localization in large, multi-floor environments with limited labeled data, Li et al.57 propose a decentralized federated learning (FL) approach combined with pseudo-labeling. Their centralized indoor localization method using the Pseudo-label(CRNP) method enhances accuracy while preserving privacy and reducing network costs, yet challenges persist with data heterogeneity, privacy sensitivity, and the computational burden of distributed training. In parallel, Ko et al.58 introduce RFBSA, a random forest-based filter designed to mitigate localization errors caused by MAC spoofing. The technique proves effective against attacker-generated noise, outperforming traditional filters and deep learning models, but maintaining robustness against increasingly sophisticated spoofing remains a concern. Ciftler et al.59 further explore privacy-preserving localization by applying FL to crowdsourced RSS fingerprint data. While achieving notable accuracy gains and safeguarding user privacy, their approach is constrained by scalability issues, slower convergence on non-IID data, and the performance limitations of low-power devices in real-time scenarios.

Further contributions focus on enhancing privacy and spoofing resistance in localization systems. Zhang et al.60 propose a lightweight privacy-preserving solution (\(LWP^2\)) for Wi-Fi fingerprinting, utilizing the Paillier cryptosystem to perform secure computations in the encrypted domain. Although it improves localization accuracy and privacy, the method incurs higher processing and communication overhead and offers limited protection for the localization server itself. Shubina et al.61 explore the privacy-accuracy trade-off in wearable networks, introducing metrics that allow users to manage location obfuscation. Their findings are informative for dense environments but may not generalize to sparse settings and highlight the ongoing challenge of balancing privacy with utility in location-based services. To detect physical-layer spoofing, Yan et al.62 develop PHY-IDS, an RSSI-based system that performs well against both naïve and informed attackers. However, its scope is limited to wearable devices and does not address broader security threats. Similarly, Madani et al.63 present a randomized moving target defense (RMTD) for detecting MAC spoofing in IoT systems. By dynamically altering network parameters, RMTD improves spoofing resistance but depends heavily on accurate modeling of advanced adversarial behavior, which may not always be feasible.

Privacy-preserving and three-dimensional localization techniques have also received notable attention. Nieminen et al.64 propose a secure two-party computation method for indoor localization, integrating Wi-Fi fingerprinting with privacy models. While their Android-based proof-of-concept demonstrates feasibility with reasonable retrieval times, scalability is hindered by computational and communication overhead. Kordi et al.65 offer a broad review of wireless IoT-based indoor localization methods, covering proximity, lateration, fingerprinting, and hybrid techniques. Although the study provides a useful taxonomy and highlights the potential of machine learning for optimization, it lacks empirical performance evaluations and real-world deployment considerations. Addressing the limitations of 2D systems, Alhammadi et al.66 present a 3D Bayesian graphical model (3D-BGM) that reduces reference point requirements while achieving competitive accuracy. Despite outperforming several baseline models, the system’s reliance on static environments and challenges in scaling to multi-story buildings limit its generalizability. A related approach by the same authors67 extends 3D-BGM with RF fingerprinting, leveraging existing Wi-Fi infrastructure to improve localization accuracy and efficiency. However, the system still requires frequent radio map updates and does not fully address scalability, security, or privacy in dynamic IoT environments.

2021

Adversarial robustness and cross-technology attacks have emerged as critical challenges in indoor localization and activity recognition systems. Patil et al.68 explore the vulnerability of RSSI-based systems to adversarial inputs, demonstrating that their deep learning model (DMLP) outperforms traditional methods and benefits from adversarial training. However, the model remains limited by its focus on white-box attacks, susceptibility to dynamic environments, and dependency on high-quality RSSI data. Similarly, Ambalkar et al.69 investigate adversarial attacks on Wi-Fi CSI-based human activity recognition systems, proposing a defense framework using Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) and Momentum Iterative Method (MIM) techniques. While the framework enhances resilience, it shares limitations with Patil et al., including an exclusive focus on white-box scenarios, sensitivity to data quality, and lack of real-world validation. Addressing secure indoor localization at scale, Wang et al.70 present RMBMFL, a multi-task collaborative learning approach achieving high accuracy in large building environments. Despite its strong performance, the method’s generalizability is uncertain due to evaluation on a single, fixed site. In a related threat landscape, Na et al.71 introduce Wi-attack, a cross-technology impersonation attack exploiting BLE advertising via Wi-Fi. Although their detection method based on power consumption variance shows promise, the approach suffers from high localization errors, low packet reception rates, and reliance on cross-technology interaction, limiting practical deployment.

Comparative evaluations of indoor localization technologies have revealed both performance differences and persistent security challenges. Dervicsouglu et al.72 assess UWB and BLE systems, showing that UWB achieves superior accuracy (0.43 m vs. BLE’s 1.54 m), but note that variations in standards and distance estimation methods introduce unpredictable security vulnerabilities, with BLE being less reliable for precise positioning. Expanding on BLE-based solutions, Sun et al.73 propose a crowdsourced localization framework using dual BERT models–BERT-AD for adversarial sample detection and BERT-LOC for localization refinement. While the system improves robustness and accuracy, its reliance on BLE alone, environmental sensitivity, and scalability issues limit broader applicability. In parallel, Madani et al.74 introduce an LSTM autoencoder-based method for detecting MAC-layer spoofing in IoT networks using RSSI data. The model handles real-time detection and adapts to signal volatility, but its applicability is constrained to specific topologies, lacks multi-node coordination, and depends on manual data labeling. Addressing data scarcity, Njima et al.75 employ GAN-based augmentation with semi-supervised learning to improve RSSI-based localization. Their approach enhances accuracy on both simulated and real datasets, yet still falls short of optimal performance and faces limitations related to training data requirements and potential inaccuracies in synthetic samples.

Security vulnerabilities in Wi-Fi-based activity recognition and location privacy remain pressing concerns. Huang et al.76 introduce IS-WARS, a stealthy adversarial attack that manipulates wireless interference from protocols like ZigBee and Bluetooth to mislead Wi-Fi-based recognition systems without detection. Their results expose the vulnerability of such systems to cross-protocol interference, which is often overlooked, compromising reliability in real-world environments. To address location privacy, Min et al.77 propose a 3D geo-indistinguishability (3D-GI) mechanism that perturbs user coordinates while maintaining service quality. Although the method effectively adapts 2D privacy models to 3D settings, it remains simulation-based and lacks real-world validation, limiting its practical impact. Beko et al.78 focus on secure localization in randomly deployed networks, combining clustering, weighted central mass, and a bisection-based GTRS approach to detect spoofing and improve localization accuracy. While outperforming existing methods in simulations, the framework’s dependence on specific network assumptions may hinder its adaptability to dynamic, real-world scenarios.

2022

Privacy-preserving indoor localization continues to evolve through edge computing, federated learning, and anonymization frameworks. Zhang et al.79 introduce Adp-FSELM, a federated stacked extreme learning model integrated with differential privacy within an edge computing framework. The system achieves robust \(\varepsilon\)–differential privacy and low localization error while minimizing calibration effort. However, fingerprint collection remains labor-intensive, and scalability is limited. Similarly, Navidan et al.80 propose a local differential privacy (LDP)-based framework for population frequency estimation in indoor spaces. Though effective under moderate privacy settings, its performance degrades with increased noise and varies across datasets, limiting generalizability. Fathalizadeh et al.81 address location privacy using a k-anonymity and l–diversity model combined with Dijkstra’s algorithm, allowing secure data sharing while maintaining utility. Still, the method overlooks more sophisticated threats like poisoning and collusion and incurs computational overhead, reducing its adaptability to dynamic or sparsely covered environments. In a related study, Boora et al.82 focus on adversarial robustness in large MIMO localization using DCNNs and neural ODEs. While adversarial training enhances resilience, models remain sensitive to noise and hyperparameters, and suffer from high computational costs, limiting scalability in real-world, evolving environments.

Adversarial training and federated learning continue to play a central role in enhancing the robustness of indoor localization and activity recognition systems. Yang et al.83 propose SecureSense, which employs techniques like label smoothing and virtual adversarial training to improve defense against both black-box and white-box attacks in device-free human activity recognition. While it strengthens DNN resilience, challenges such as training instability, hyperparameter sensitivity, and limited real-world validation restrict its deployment in dynamic or resource-constrained environments. In a similar direction, Ye et al.84 introduce SE-Loc, a semi-supervised method that effectively combines labeled and unlabeled data for secure indoor localization. Despite high robustness under adversarial conditions, its accuracy is still affected by the presence of numerous malicious APs. Addressing adversarial threats in RSSI-based systems, Wang et al.85 develop AdvLoc using DCNNs with adversarial training, demonstrating strong performance against first-order attacks. However, the method lacks evaluation against more advanced attacks and across diverse environments. Han et al.86 present a CNN and ResNet-based defense for device-free localization that effectively detects spoofed signals and sensor faults, though it remains vulnerable to physical damage and tampering. Finally, Gao et al.87 propose FedLoc3D, a federated learning framework for cross-building 3D localization. Their approach, combining CNN-based classification and regression models, shows improved accuracy and privacy preservation but faces challenges related to network unreliability, data heterogeneity, and scaling in 3D environments.

2023

Recent efforts have focused on enhancing the reliability, security, and privacy of indoor localization systems through trust modeling, blockchain, and decentralized authentication. Peterseil et al.88 propose a trustworthiness score integrated with autoencoder neural networks and weighted non-linear least squares to reduce UWB localization errors by up to 50% in dynamic environments. While effective in controlled settings, the approach relies heavily on high-quality training data and requires calibration for varied deployments, limiting scalability and robustness under non-line-of-sight conditions. Shakerian et al.89 introduce a blockchain-supported indoor navigation system combining dual IMU sensors and the ZUPT algorithm, achieving reliable navigation with a mean root mean square error (RMSE) of 1.2 m. Despite secure data handling through Hyperledger Fabric, challenges include limited energy capacity, dependence on Wi-Fi, and untested performance under complex movements or large-scale deployments. Addressing adversarial threats, Mitchell et al.90 assess the vulnerability of learning-based localization models, showing that omniscient attacks significantly degrade accuracy. While adversarial training and outlier detection improve resilience, broader threat models and infrastructure-level vulnerabilities remain unexplored. Casanova et al.91 propose a decentralized attribute-based authentication (ABA) protocol using BLE and zero-knowledge proofs to secure collaborative indoor positioning systems. The protocol improves privacy, untraceability, and unlinkability, offering a practical alternative to centralized schemes, though it highlights the limitations of existing CIPS protocols in safeguarding user identity.

Privacy, energy efficiency, and threat detection remain key themes in recent indoor localization research. Mohsen et al.92 present PassiFi, a privacy-preserving system using passive Wi-Fi TDoA and deep learning regression to achieve sub-meter accuracy, outperforming traditional multilateration. However, its scalability and performance degrade under environmental changes, and privacy trade-offs–such as reliance on trusted entities and vulnerability to spatio-temporal attacks–remain unresolved. Focusing on secure 3D localization, Kalpana et al.93 propose a hybrid method combining acoustic and distance-based approaches with cryptographic safeguards. Their solution reduces localization error and energy use while identifying Sybil and malicious nodes. Yet, computational overhead, sensitivity to RSSI fluctuations, and reliance on beacon nodes limit its real-time applicability. In a related effort, Gebremariam et al.94 develop a hybrid machine learning framework for detecting routing threats in WSNs, achieving high localization precision and perfect threat detection in simulations. Nevertheless, the model’s processing demands, dependency on accurate training data, and lack of validation in dynamic environments raise concerns about scalability and practical deployment. Addressing spoofing attacks, Chen et al.95 introduce UnSpoof, a UWB-based system leveraging passive anchors and secure two-way ranging to detect and locate spoofed tags. While effective at distinguishing spoofed from genuine tags, its accuracy declines when devices fall outside the anchor-defined area, and its adaptability to diverse spoofing techniques remains uncertain.

Adversarial robustness, privacy, and federated learning continue to shape the advancement of indoor localization systems. Xiao et al.96 propose FooLoc, an over-the-air adversarial attack that generates subtle yet effective perturbations to mislead Wi-Fi-based DNN localization models, achieving up to 90% success in untargeted attacks. Despite its efficiency, the method relies on downlink CSI and faces challenges in practical implementation due to the limitations of additive perturbation on CSI measurements. Addressing privacy, Fathalizadeh et al.97 introduce GeoInd, a differential privacy-based framework that adds Gaussian noise to RSS data for geo-indistinguishability without relying on third parties. While effective in simulations, its lack of real-world deployment and limited scope raise concerns about broader applicability. In the realm of federated learning, Guo et al.98 present FedPos, a federated transfer learning system that reuses feature extractors across domains to reduce training data needs by 65% and achieve a mean localization error of 42.18 cm. However, its performance may be insufficient for precision-critical applications and remains validated only in limited indoor environments. Gufran et al.99 further advance this field with FedHIL, a heterogeneous FL framework incorporating stacked autoencoders and communication-efficient strategies to enhance accuracy while reducing latency. Though it outperforms existing models, its sensitivity to device heterogeneity, environmental noise, and generalization issues limits its scalability and robustness in dynamic settings.

Privacy-preserving indoor localization techniques have increasingly incorporated differential privacy, reinforcement learning, and federated learning. Xu et al.100 utilize Wi-Fi fingerprints and extreme learning machines with local differential privacy (LDP) to reduce data exposure during model training, demonstrating improved privacy with lower data quality degradation than centralized approaches. However, their method still suffers from up to 7.2% data loss and potential performance trade-offs compared to established techniques. Addressing semantic location privacy, Min et al.101 propose SALPPM, a reinforcement learning-based framework using modified geolocation data and semantic tags in 3D indoor environments. By leveraging D3QN and A3C algorithms, the system refines perturbation strategies and policy selection. Yet, its scope is limited to specific RL methods, excluding alternative algorithms or continuous action spaces, which may hinder adaptability. Similarly, Kumar et al.102 present f-ILC, a federated learning-based Wi-Fi fingerprinting framework combining CNN-LSTM to enhance localization accuracy and preserve user anonymity. The system performs well across IID and non-IID settings but faces challenges in hierarchical space modeling, resource demands, and real-time deployment feasibility. Finally, Shahbazian et al.103 provide a broader examination of machine learning applications in IoT localization, highlighting both current limitations and future opportunities, though lacking specific experimental validations or frameworks.

Security and privacy remain central to recent innovations in indoor localization. Chen et al.104 propose UnSpoof-Passive Ranging, a hybrid active-passive system that achieves 30 cm accuracy for legitimate tags and sub-meter precision for spoofed tags using ToF and TDoA measurements. While effective at detecting distance manipulation attacks even beyond the anchor convex hull, its performance is sensitive to anchor geometry, non-line-of-sight conditions, and multi-antenna spoofing. Additional limitations include high energy consumption, computational overhead, and limited scalability in multi-client deployments. In a parallel effort, Wang et al.105 introduce a privacy-preserving localization method based on two-party computation and Paillier encryption, offering enhanced RSS protection and reduced communication costs. However, the computational complexity of encryption may hinder real-time performance, and the reliance on a two-party model restricts applicability in decentralized systems. Addressing access point vulnerabilities, Tiku and Pasricha106 develop S-CNNLOC, a secure CNN-based framework that improves robustness against AP-level attacks, achieving up to 10 times greater resilience than conventional models. Despite its strong accuracy and security gains, challenges remain in scaling the framework and adapting it to diverse and dynamic network environments.

Recent advancements in indoor localization continue to address challenges related to security, privacy, and performance under dynamic conditions. Ma et al.107 propose LENSER, a CSI-based system for detecting unauthorized devices, which improves localization accuracy by 86.1% and reduces time overhead by 58.2% compared to existing methods. Despite these gains, the system remains sensitive to environmental fluctuations, indicating a need for enhanced robustness. Brachmann et al.108 examine privacy risks in XR localization using the LINDDUN framework, identifying threats such as identifiability and linkability in XR glasses and suggesting targeted mitigation strategies. However, the framework’s reliance on static threat categories may limit its adaptability in evolving XR scenarios. To strengthen privacy in LBS, Yan et al.109 introduce LDPORR, a local differential privacy method that applies Hilbert encoding and spatial decomposition to enhance both privacy and efficiency. While effective on real-world datasets, its processing complexity may hinder scalability in dynamic environments. Pandey and Patel110 develop SLABLDA, a secure fingerprinting algorithm that models AP location diversity and compensates for RSSI variability, yielding improved accuracy in complex indoor environments. Nonetheless, reliance on offline evaluations may restrict responsiveness in rapidly changing conditions. Lastly, Billa et al.111 offer a comprehensive review of indoor localization technologies for IoT systems, highlighting the trade-offs between cost and accuracy, particularly in hybrid and high-precision systems like UWB and VLC. Their work underscores the need for adaptable and cost-effective solutions that balance performance and practical deployment constraints.

2024

Recent research in 2024 has focused on enhancing indoor localization systems through federated learning, adversarial resilience, and cryptographic privacy-preserving techniques. Etiabi et al.112 propose a federated distillation (FD) approach that reduces communication overhead in IoT networks by 98% while maintaining localization accuracy and improving energy efficiency. However, its applicability to regression-based tasks like localization remains limited, and transmission energy savings come at the cost of increased computational demand. Gufran et al.113 introduce CALLOC, a lightweight, adversarial-resilient framework leveraging curriculum learning to improve localization robustness across devices and settings. Although it significantly reduces localization error, its performance depends heavily on curriculum design and has yet to be validated in dynamic real-world environments. Additionally, the computational load from attention mechanisms and adversarial training may hinder deployment on low-power devices. Eshun et al.114 present a cryptographic localization framework that ensures mutual privacy between users and service providers by offloading encrypted computation to a third-party cloud server. While it achieves up to 99% cost reduction, the system’s resilience against active adversaries remains unexplored. Huang et al.115 examine vulnerabilities in off-device wireless positioning systems and demonstrate practical attacks using homomorphic encryption and oblivious transfer. Although defenses are proposed, the study is confined to specific wireless environments, and inherent privacy concerns in off-device architectures present challenges for secure deployment in future networks.

Privacy-preserving indoor localization systems in 2024 have increasingly leveraged generative models, differential privacy, and adversarial threat analysis. Moghtada et al.116 propose DPGANs, a framework combining generative adversarial networks with differential privacy to protect user data while generating realistic synthetic fingerprints. While effective at preserving accuracy under moderate privacy constraints, performance degrades at higher privacy levels, and the reliance on a single generator-discriminator pair limits scalability and adaptability to complex environments. Fathalizadeh et al.5 provide a comprehensive review of privacy-preserving fingerprinting techniques, offering a novel classification framework for adversary models, vulnerabilities, and evaluation metrics. The study highlights critical research gaps and encourages future exploration into unified privacy frameworks. Examining attack impacts, Machaj et al.117 analyze Wi-Fi AP spoofing using KNN and the UJIIndoorLoc dataset, showing significant degradation in localization accuracy tied to the number of spoofed APs and reference points. However, the study’s focus on a single method and dataset limits generalizability to broader contexts and techniques. Addressing task privacy in mobile crowdsensing, Hemkumar et al.118 introduce a geo-obfuscation strategy combining local differential privacy, geo-indistinguishability, and k-means clustering to defend against inference attacks. Despite outperforming existing methods like Eclipse and PIVE, its effectiveness depends on environmental conditions, clustering parameters, and AP density, and it lacks evaluation against more advanced or emerging attack models.

Emerging 2024 studies continue to explore privacy threats and adversarial defenses in indoor localization. Li et al.119 propose RFTrack, a stealthy tracking attack that leverages RSSI time sequences and reinforcement learning to infer device locations using passive Wi-Fi sniffing. While it achieves high precision in structured environments, its effectiveness is limited by RSSI instability, bootstrap inaccuracies, and challenges in differentiating similar trajectories, particularly in open or dynamic settings. Pettorru et al.6 offer a comprehensive review of IoT localization strategies, examining vulnerabilities and the potential of AI, blockchain, and quantum computing for improving security. Despite identifying key advancements, the study notes issues such as hybrid system complexity, high energy demands, and a lack of empirical validation across many proposed solutions. Addressing robustness in noisy environments, Yang et al.120 introduce TRAIL, a three-phase adversarial architecture that combines transfer learning and adversarial interaction to improve accuracy in low SNR conditions. Though it outperforms existing methods, the model struggles with environmental variability and balancing offline-online data alignment during training. Lastly, Wang et al.121 present a privacy-preserving scheme using inner product encryption to secure location data from untrusted cloud services. While it maintains accuracy with low computational overhead, its scalability and adaptability to real-time, large-scale deployments remain untested, particularly under frequent data updates.

Privacy-preserving and trustworthy localization frameworks have continued to evolve through encryption, blockchain, and probabilistic modeling. Wang et al.122 propose a secure indoor localization framework using inner product encryption (IPE) and ranging transformation to protect user and anchor data in cloud-based systems. While it maintains localization accuracy with low overhead, its scalability in real-time, dynamic environments remains a concern. Zocca and Hasan123 introduce a blockchain-based localization scheme using Hyperledger Fabric to ensure trust, data integrity, and privacy. The system shows strong security performance and leverages UWB for improved accuracy, but its reliance on centralized storage and blockchain transaction overhead may hinder scalability in large IoT networks. Verma et al.124 highlight privacy risks from unauthorized geo-tracking using device sensors, presenting an attack model with 98% accuracy without GPS and recommending mitigation strategies for Android platforms. However, the approach lacks real-world deployment and generalization beyond Android ecosystems. Addressing physical-layer privacy, Li and Mitra125 propose the DAIS method, which obfuscates delay and angle information to mislead eavesdroppers while preserving authorized localization accuracy. Though resilient to precoder leakage and effective under high SNR, its reliance on secure communication may be vulnerable in dynamic or adversarial conditions. Finally, Alhammadi et al.126 present a 3D Bayesian graphical model that reduces localization error to 1.8 meters using Wi-Fi fingerprints and adaptive probabilistic reasoning. While it demonstrates scalability and efficiency, limitations include dependence on static access points, lack of built-in security features, and computational intensity during sampling in resource-constrained settings.

2025

Recent studies in 2025 have emphasized privacy, efficiency, and robustness in Wi-Fi and BLE-based localization and sensing systems. Abuhoureyah et al.127 provide a comprehensive review of CSI-based human activity recognition (HAR), highlighting CSI’s advantages in mitigating signal distortion for location-independent sensing. However, transmission and reception noise remain key limitations, especially in constrained environments. David et al.128 explore privacy vulnerabilities in BLE beacons and propose a quasi-periodic randomized scheduling method to counter battery insertion attacks. While effective at obfuscating initialization timestamps, the study does not fully address power trade-offs or large-scale deployment feasibility. Enhancing secure location queries, Li et al.129 introduce ROLQ-TEE, a TEE-based framework that supports privacy-preserving and revocable location queries via cryptographic RNN techniques. Despite improved performance over traditional schemes, TEE-related processing overhead raises concerns for scalability in larger systems. Boudlal et al.130 present a low-cost, non-intrusive HAR system using existing Wi-Fi CSI and deep learning to detect activities without wearables or cameras. While demonstrating strong performance, the system faces challenges related to hardware variability, environmental sensitivity, and computational demand. Finally, Nie et al.131 propose MS.Id, a mobile single-station identification method leveraging spatiotemporal data and MAC de-randomization to improve user identification. Achieving 95.24% accuracy and reduced localization error, the system offers scalable, infrastructure-light deployment but may encounter issues in dynamic environments, device heterogeneity, and potential privacy concerns from MAC-level data handling.

As shown in Table 2, security and privacy solutions in ILS vary widely in trade-offs between robustness, scalability, and efficiency. Cryptographic methods ensure strong confidentiality but often introduce significant latency and overhead, limiting real-time deployment64,114. Federated learning enhances data privacy in decentralized settings, yet remains vulnerable to poisoning and struggles with non-IID data59,87. Differential privacy offers theoretical guarantees but often degrades localization accuracy in dense environments [77], [114]. Adversarial training and GAN-based defenses improve resilience against spoofing but lack generalizability and are resource-intensive79,116. Blockchain solutions add transparency but suffer from scalability and energy constraints89,123. Lightweight approaches like MAC de-randomization and TEE-assisted queries are promising for real-time IoT deployments, though they trade off latency and coverage127,128,129,130,131. Overall, no single approach offers a balanced solution across privacy, accuracy, and computational efficiency–highlighting the need for hybrid, adaptive frameworks.

To provide a clearer overview of the existing research landscape, Table 3 presents a comparative summary of key studies in the domain of ILS security and privacy. It highlights the respective threat models, techniques, datasets or environments, main results, and known limitations, enabling readers to identify major trends and remaining gaps in the field.

Privacy–accuracy trade-offs with case examples

A recurring theme in ILS research is the tension between preserving user privacy and maintaining localization accuracy. While theoretical discussions highlight this balance, concrete case studies illustrate the trade-offs more vividly.

For example, healthcare applications often require strict privacy guarantees when handling patient movement data. Zhang et al.79 demonstrate that integrating differential privacy into federated edge learning frameworks substantially reduces the risk of individual data leakage. However, they also report up to a 7–10% decline in localization accuracy in dense hospital environments, underscoring the performance cost of strong \(\varepsilon\)–privacy guarantees. Similarly, Moghtadaiee et al.116 show that differentially private GANs (DPGANs) can protect patient location traces, but accuracy deteriorates sharply as the privacy budget tightens.

In the financial services sector, federated learning has been explored for collaborative location-based authentication without centralizing sensitive user trajectories. Ciftler et al.59 and Gao et al.87 both show that federated models achieve comparable accuracy to centralized methods under controlled conditions. However, when different institutions contribute heterogeneous datasets, it is common for their performance to drastically deteriorate in non-IID data scenarios. This points to an important trade-off in which statistical differences across sites can be reduced accuracy, while at the same time privacy is enhanced by keeping the data decentralized.

Real-time IoT applications provide practical examples of these challenges. David et al. 128 show that stochastical scheduling of BLE beacons can improve privacy by obscuring timestamps to reduce the risk of tracking attacks. However, in large-scale deployments, this approach often comes at a cost of reduced coverage and increased latency. Similarly, Li et al. 129 employed trusted execution environments (TEEs) to protect location queries. While their method offers strong security guarantees, the added processing overhead limits its scalability for real-world applications.

Taken all together, these findings point to a clear pattern in which privacy-preserving solutions almost always come with a cost. Common challenges include higher latency, limited scalability, and reduced accuracy. This highlights the need for adaptable hybrid frameworks that can dynamically balance accuracy, privacy and efficiency to address the requirements of different applications.

Comparative study of privacy and security approaches in ILS

Security threats in ILS

From 2020 to 2025, ILS security and privacy measures progressed from encryption approaches and GDPR-compliant access controls to sophisticated methods such as FL and adversarial training. Initial techniques, such as the Paillier cryptosystem and fast gradient sign method (FGSM), facilitated the development of contemporary methods such as GAN-based data augmentation and LD for safeguarding privacy. Primary priorities encompass precision, confidentiality, practical applicability, and energy efficiency. CNN-based and UWB systems have enhanced accuracy of over 90%; however privacy-preserving solutions frequently compromise accuracy for security. Energy efficiency and communication overhead continue to pose issues, especially for federated learning and IoT systems59,82,89,112.

In 2025, ILS privacy and security research expanded to wireless sensing, BLE beacon tracking, and privacy-preserving location queries. Key advancements include CSI-based human activity recognition127, BLE beacon privacy enhancements128, TEE-based location queries129, Wi-Fi CSI-based indoor activity detection130, and mobile Wi-Fi user identification131. These developments highlight emerging privacy challenges, emphasizing the need for improved obfuscation, efficiency, and scalability.

To orient the reader, Table 2 synthesizes prominent ILS papers by threat/attack type, countermeasure, data setting, and utility trade-offs, providing a quick map of the security landscape before deeper discussion.

Highlighting trends over the years

Indoor localization research from 2020 to 2025 shows a clear evolution from privacy preservation to advanced machine learning integration. In 2020, emphasis was placed on privacy and federated learning (FL)59, with growing interest in encryption (Paillier cryptosystem60) and GDPR-compliant access control52. By 2021, adversarial training methods (FGSM, PGD, MIM69) gained traction, complemented by GAN-based data augmentation75 and BERT for adversarial recognition73. In 2022, noise-based privacy (LDP80), adversarial robustness82, and differential privacy techniques79 were consolidated. The year 2023 advanced deep learning with CNNs100 and FL98, while blockchain89 and UWB systems88 emerged for secure localization. In 2024, adversarial learning and FD dominated privacy-preserving localization112, reinforced by cryptographic protocols114 and GAN-driven synthetic data116. Finally, 2025 studies furthered privacy and security with CSI-based sensing for HAR127, BLE beacon analysis128, TEE-based queries129, Wi-Fi CSI activity detection130, and mobile station Wi-Fi user identification131.

Overall, the field has progressively integrated FL, adversarial training, privacy-preserving mechanisms, GANs, cryptographic protocols, and deep learning. Each methodology offers unique strengths and trade-offs, shaping the trajectory of modern indoor positioning systems. Table 4 concisely summarizes these developments from 2020–2025.

Privacy issues in ILS

Comparisons of existing solutions

An analysis of current privacy and security solutions for ILS shows various methods, each with unique advantages and disadvantages depending on particular use cases and system needs. FL provides a decentralized approach to preserving privacy by not sharing sensitive data during the training process57,59,79. This method improves scalability and minimizes data-sharing risks, making it appropriate for dynamic settings such as crowdsourced localization and smart cities. However, it encounters challenges related to the scalability of large datasets, significant communication overhead, and vulnerability to model poisoning87,99. Conversely, differential privacy (DP) methods79,97 safeguard privacy by introducing noise to data, which helps keep individual location traces anonymous. Although differential privacy ensures robust privacy protection, finding the right balance between added noise and the accuracy of the system is a considerable challenge116. Cryptographic techniques like homomorphic encryption60,122 ensure strong data confidentiality and are resistant to unauthorized access. Nonetheless, their significant computational cost and communication overhead restrict their use in real-time systems and large-scale environments64,114.

Blockchain offers a reliable and transparent solution for location data due to its immutable ledger capabilities89,123. This ensures the authentication and verification of location-based transactions, making it suitable for systems that need clear data integrity, like IoT-based localization and supply chain tracking. Blockchain faces challenges related to scalability, significant energy consumption in its consensus mechanisms, and difficulties with integration89. Adversarial training83,85 improves model robustness by protecting against data manipulation. However, it comes with high computational costs and can result in overfitting when trained on adversarial examples. This approach is especially beneficial in applications where security is crucial, such as autonomous vehicles and AI-based navigation systems.

Recent research in 2025 has further advanced privacy-preserving solutions for ILS. CSI-based sensing has been explored for human activity recognition (HAR) in wireless sensing, where Abuhoureyah et al.127 highlight the potential of Wi-Fi-based CSI for improving signal processing accuracy while recognizing challenges such as noise interference. Similarly, Boudlal et al.130 propose a cost-effective, privacy-preserving Wi-Fi CSI-based activity detection system, eliminating the need for wearable sensors or visual monitoring, making it a viable solution for smart environments.

Privacy concerns with BLE beacon tracking have been critically examined by David et al.128, who demonstrate the Battery Insertion Attack on BLE beacon randomization and propose quasi-periodic randomized scheduling as a countermeasure. However, their solution may introduce trade-offs in power consumption. In privacy-preserving location queries, Li et al.129 introduce ROLQ-TEE, a TEE-based framework for securely handling outsourced location queries, ensuring location confidentiality while allowing for revocable query authorization. Nonetheless, TEE-based computations impo higher server-side processing costs, which may limit large-scale applicability.

se Efforts in Wi-Fi-based indoor localization have also been expanded by Nie et al.131, who propose MS.Id, a mobile single-station user identification approach leveraging IE-based MAC de-randomization. Their findings indicate improved accuracy over multi-station techniques while reducing infrastructure overhead, though potential privacy concerns regarding MAC de-randomization remain.

Privacy-preserving frameworks that integrate methods such as FL, cryptography, and anonymization (for example, k-anonymity) provide thorough protection81,116. These frameworks keep location data secure while maintaining system performance.

Each solution offers distinct advantages and limitations within the ILS context. While FL, DP, and cryptographic methods ensure privacy, they face scalability and real-time application challenges. Blockchain enhances transparency but struggles with energy efficiency and integration. Adversarial training improves robustness but increases computational costs. Recent 2025 advancements–CSI-based sensing, BLE beacon privacy, TEE-secured location queries, and MAC de-randomization for user identification–broaden privacy-preserving options in ILS, each with distinct benefits and challenges. The summary of current trends, their advantages, disadvantages, and suitability in ILS is presented in Table 5.

Defense mechanisms in ILS

Strengths and limitations of various approaches

Upon conducting a thorough examination of the present methodologies, it becomes evident that there are several strengths and limits. Significant advancements have been made in adapting privacy-preserving and adversarial-attack-resistant models for real-world applications, especially in the fields of IoT, GNSS-denied environments, and indoor localization employing UWB systems88. FL and its advanced variations, such as FD, show great potential in facilitating safe and decentralized learning while avoiding privacy vulnerabilities112. Furthermore, there have been consistent advancements in localization accuracy, especially in the presence of noise and adversarial conditions82. These advancements have been particularly notable in solutions that utilize CNN-based and blockchain-based technologies75,85,86,89. Moreover, cryptographic protocols have been used to ensure security in collaborative localization tasks91.

Nevertheless, there are significant constraints. Methods such as adversarial training68, GAN data generation75, and cryptographic protocols91 often impose computational overhead, necessitating substantial processing capacity. Consequently, their implementation becomes challenging in situations with limited resources. Scalability is still a problem, as solutions that work well in simulations or small real-world settings may not adequately handle large systems82,93,104. FL models, in particular, have difficulty converging when dealing with non-IID data87,98. Privacy-preserving strategies, such as differential privacy97, include a trade-off between privacy and accuracy. Increasing privacy levels can sometimes result in decreased localization accuracy, a challenge that remains unresolved79. Table 6 summarizes the strengths and limitations of various approaches. However, challenges related to scalability and adaptability in dynamic environments persist. Combining location fingerprinting with anonymization techniques effectively protects user privacy117. However, it is susceptible to attacks such as Wi-Fi AP spoofing, which can undermine security.In conclusion, UWB-based systems for detecting spoofing attacks95,104 achieve high accuracy but face challenges in real-time detection and scalability in large networks.

Key parameters

The publications have identified accuracy, privacy, real-world feasibility, and energy efficiency as the main parameters. Accuracy remains the paramount factor, with the majority of approaches striving for a success rate of above 90%, namely in UWB-based and CNN-based positioning systems55,70,82. These systems attempt to enhance performance in both challenging and real-life situations. Privacy is a critical aspect, and differential privacy and encryption methods have a substantial impact52,80. Techniques such as adding noise to data81,97 and employing cryptographic methods60,114 were extensively investigated to improve privacy safeguards. The emphasis on real-world viability increased as research transitioned from solely simulated environments in 2020-202153,68 to tangible applications by 2024, particularly in the fields of IoT and ILS112. Finally, the issue of energy efficiency has become a significant problem, specifically in the context of blockchain-based and FL systems89,113. By 2024, the primary goal is to minimize communication overhead and increase energy consumption112.

In 2025, research continued to refine privacy-preserving techniques, especially in BLE beacon-based tracking and Wi-Fi CSI-based activity recognition. David et al.128 demonstrated vulnerabilities in BLE beacons, highlighting the need for improved temporal obfuscation mechanisms. Similarly, Li et al.129 introduced ROLQ-TEE, leveraging Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) to safeguard location-based queries while minimizing computational costs. Meanwhile, Wi-Fi CSI-based sensing gained traction as an energy-efficient and privacy-conscious alternative for indoor activity recognition130. Furthermore, Nie et al.131 proposed MS.Id, a mobile single-station Wi-Fi-based user identification approach that achieves high accuracy while reducing reliance on extensive infrastructure deployment. These developments underscore the growing intersection of accuracy, privacy, and feasibility in ILS research. Table 7 summarizes the key parameters in ILS.

Security and privacy concerns in ILS

ILS are becoming increasingly crucial in numerous applications; however, they have multiple weaknesses that might jeopardize the accuracy and reliability of location data. An important weakness is the proneness to signal interference and spoofing. Many ILS systems, dependent on RF signals like Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, or RFID, are vulnerable to disruption from other devices and ambient conditions. This vulnerability allows malicious attackers to launch adversarial assaults. These attacks can result in substantial inaccuracies in position monitoring or unlawful entry into restricted areas, creating security risks, particularly in sensitive settings such as hospitals, military installations, or financial organizations.