Abstract

In this study, we present the synthesis of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) nanofibers functionalized with an acrylic-β-cyclodextrin (β-CD-Acr) polymer as advanced adsorptive material for pharmaceutical removal from water. The modified nanofibers (NFs) demonstrated superior adsorption performance towards the model compound pimavanserin, with an equilibrium adsorption capacity of 56.2 mg/g compared to 34.2 mg/g for the β-CD-Acr polymer alone. The maximum uptake capacity also nearly doubled (113.6 mg/g vs. to 54.8 mg/g) highlighting the benefits of using the nanofiber support. The versatility of this polymer allows it to be polymerized onto various substrates, making it a promising candidate for large-scale applications. The results suggest that this innovative adsorptive nanofiber system could play a crucial role in combating water pollution globally, offering an effective and scalable solution for the removal of hazardous pharmaceuticals from wastewater.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global attention has recently turned to emerging pollutants, defined as synthetic and/or naturally occurring chemicals that still remain unregulated in the environment or are currently undergoing a regularization process1,2. They are classified based on their origin, which includes pharmaceuticals, disinfection by-products, wood preservations, industrial chemicals, and microplastics1,3. Pharmaceuticals, in particular, are a major concern as an emerging pollutant due to their widespread and continuous release into the environment1,4. While some degrade naturally, certain compounds resist breakdown, leading to their persistence in the environment and accumulation, raising concerns about their potential risks to ecosystems and human health5,6.

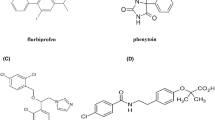

Pharmaceuticals are repeatedly detected in water, typically observed in the range of µg to ng per liter, commonly including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics (i.e. paracetamol, ibuprofen, and diclofenac), β-blockers (i.e. atenolol, propranolol, and metoprolol), antihistamines (i.e. ranitidine and famotidine), antibiotics (i.e. penicillin, quinolones, and imidazole derivatives), as well as psychoactive compounds, and endocrine disruptors2,7.

Pimavanserin (PMV) is the chosen drug in this study, being an atypical antipsychotic drug widely used to treat Parkinson’s disease psychosis8. It is also used in the management of other psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia and has been investigated as a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s psychosis9,10,11. Parkinson’s disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder in the world. The World Health Organization estimates that neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, will become the second leading cause of death worldwide by 2040, surpassing cancer-related mortality12.

However, PMV has limited biological degradation in water and is toxic to aquatic organisms11. Its widespread use and resistance to degradation raise concern about potential ecological risk, emphasizing the need for effective separation technologies to manage industrial raffinates and prevent environmental contamination through wastewater discharge. Recent industry analyses estimate the global market value of pimavanserin at approximately USD 150–300 million, with projections indicating steady growth over the next decade13. As production and consumption increase, so too does the potential for this persistent and toxic compound to enter wastewater streams, making it essential to develop efficient removal technologies before it accumulates in aquatic environments.Common pharmaceutical wastewater purification methods include advanced oxidation processes, biological treatment, adsorption, and membrane filtration14,15. Advanced oxidation processes, although highly effective, often lead to the formation of harmful by-products and require high energy and chemical inputs which hence makes them less effective and not environmentally friendly16,17. Similarly, biological treatment struggles with removing environmentally persistent pharmaceutical pollutants and is sensitive to environmental conditions, resulting in lower efficiency and slower processing times18,19.

In contrast, removal by adsorption and membrane filtration offer more reliable and effective solutions, conveying fewer operational challenges and a greater ability to consistently remove pharmaceuticals without generating harmful by-products. Adsorption techniques, such as using activated carbon, provide high removal rates for a broad spectrum of pharmaceutical compounds by binding them to adsorbent surfaces. This method is effective and relatively simple to implement and maintain, with the added benefit that adsorbents can often be regenerated and reused, reducing long-term operational costs14,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. On the other hand, membrane filtration offers precise separation capabilities, effectively filtering out even the smallest pharmaceutical molecules based on size exclusion or charge interactions. This technology ensures high purity in the treated water, with minimal by-product formation and consistent performance under varying conditions14,19,27.

Recent innovations have led to the emergence of adsorptive membranes, which employ a hybrid approach that combines the high removal efficiency of adsorption with the precision of membrane filtration. These membranes are designed with functional groups or material components on their internal or external surfaces which enhance their surface-binding properties, making them highly effective at removing pollutants such as dyes, heavy metals, and pharmaceuticals with exceptional reliability28,29,30,31.

Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) is widely recognized in the membrane industry for its excellent mechanical properties, thermal stability, and resistance to a wide range of chemicals. Its chemical resistance allows the development of membranes that withstand harsh environments and a wide range of pH’s without degrading. Additionally, the outstanding mechanical strength and thermal stability ensure durability and long operational life even under demanding conditions32,33,34,35.

Despite PVDF’s excellent properties, the inherent hydrophobic nature, presents challenges in water treatment applications, particularly in interactions with polar contaminants. However, grafting a chemical modifier onto the PVDF surface can significantly enhance its wetting properties, leading to the development of more advanced membranes36,37,38. By selecting a modifier with strong binding capabilities, the membrane can gain adsorptive qualities, making it more effective in capturing a broader range of pollutants, including pharmaceuticals.

Cyclodextrins (CDs), a class of cyclic oligosaccharides, are particularly promising as modifiers for PVDF. They offer the potential to transform the membrane’s surface characteristics and improve performance in water treatment39,40,41,42. Cyclodextrins are supramolecular species characterized by unique torus-shaped molecular structures. The torus architecture features a hydrophobic inner cavity and a hydrophilic outer surface, allowing CDs to bind various guest molecules, including dyes, heavy metals, and pharmaceuticals43,44.

This study focuses on synthesizing PVDF nanofibers (NFs) modified with an acrylic-β-cyclodextrin (β-CD-Acr) polymer for pharmaceutical contaminant removal applications. Using PMV as a model drug, the material is evaluated in two configurations: as a conventional adsorption system (β-CD-Acr polymer granules in suspension) and as a PVDF NFs coating. We hypothesize that coating PVDF nanofibers with β-cyclodextrin polymer will enhance adsorption performance compared to its granular form by leveraging the nanofiber’s inherent high surface area. This will hypothetically increase the accessibility of the β-CD, and hence enhance interactions with pharmaceutical contaminants. Additionally, the β-CD coating is expected to address PVDF’s hydrophobicity-driven limitations in aqueous environments: the hydroxyl-rich β-CD moieties will introduce hydrophilic sites, improving wettability and mitigating diffusion barriers inherent to pristine PVDF nanofibers. This synergistic design aims to optimize both adsorption capacity and kinetics for water treatment applications.

Materials and methods

Materials

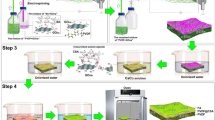

Solvents used were supplied from commercial sources (Merck, TCI etc.) and used without further alteration. β-CD (> 98%, Cyclolab), acryloyl chloride (> 97%, Merck), Pimavanserin tartrate (> 97%, LGM Pharma, USA), PVDF (Kynar, Arkema, France), 2,2′-azobis(2-methylpropionitrile) (AIBN, 98%, Merck), were all used as supplied. PVDF nanofibers (density of 3.5 g/m2) were produced using a needleless electrospinning device (Nanospider NS 8S1600U, Elmarco, Liberec, Czech Republic) from a 13% solution in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 99.8%, Merck), using PVDF with a melt viscosity ranging from 30.5 to 36.5 kPoise.

Instrumental characterization

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

FTIR was recorded using a Nicolet iS10 (ThermoFisher Scientific). ATR techniques were used for obtaining spectra, averaging 8 scans, with background adjusted, and recorded in the range 4000–400 cm− 1 with a resolution of 4 cm− 1. The spectra were evaluated using Omnic software.

High-resolution mass spectrometry

High-Resolution Mass Spectroscopy (HRMS) spectra were measured using a X500R QTOF mass spectrometer (Sciex) with flow injection. The carrier solution consisted of 10% methanol and 0.1% formic acid in HPLC-MS grade water. Spectra were recorded both in positive, whereby the source temperature was set to 300 °C, gas 1 to 30 PSI gas 2 to 40 PSI with spray voltage set to 5,500 V and a declustering potential of 80 V.

Nuclear magnetic resonance

Liquid and Solid-state (SS) NMR spectra were recorded using a 400 MHz JNM-ECZ400R/M1 NMR spectrometer (JEOL) at ambient temperature (295 K). 1H and ROESY measurements were recorded in D2O, with the residual solvent peak used for referencing chemical shifts, whilst further 2D spectra and 13C measurements were recorded in DMSO-d6 with 5% D2O (v/v). For SS-NMR analysis, samples were packed into a 3.2 mm ZrO2 rotor, with 13C spectra recorded using CP/MAS or spin-echo (HahnEcho/MAS) at a MAS of 20 kHz with high-powered 1H decoupling (TTPM). Recorded sample spectra were externally referenced to γ-glycine (174.1 ppm carbonyl signal) with relaxation delays and number of scans optimized based on samples measured. For CP/MAS, optimized parameters used included 2,048 scans, 5 s relaxation delay, a π/2 pulse of 2.35 µs at 8.7 dB, and a contact time of 2 ms. HahnEcho/MAS using 2,800 scans, 25 s relaxation delay, a π/2 pulse of 2.13 µs at 8.7 dB, and with 50 µs pre- and post-echo’s were used to acquire spectra. Spectra were subsequently analyzed using MestReNova software (v. 14.3.1).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) was undertaken using a Nano ITC low volume instrument (TA Instruments), with measurements taken at 25 °C in distilled water. Samples were sonicated for 30 min to reduce amounts of dissolved gases before measurements, with analysis of obtained data using NanoAnalyze (v. 3.12.5).

Scanning electron microscope

Scanning Electron Microscope SEM images were acquired using Zeiss ULTRA Plus; an ultra-high-resolution SEM equipped with Schottky cathode imaging (SE2, InLens, ESB, ASB). The samples were prepared by sputter-coating with a thin layer of gold, with imaging performed at an ETH of 1 KV and a magnification range of 10–50 KX with an aperture size of 10 μm.

Surface area (BET)

Prior to analysis, the samples were degassed under vacuum. The raw data was obtained using adsorption of krypton at liquid nitrogen temperature (Autosorb 6100, Anton Paar), with the BET surface area calculated using software Anton Paar Kaomi for Autosorb v. 2.01.

Drop shape analyzer

Water contact angles were measured using the Drop Shape Analyzer DSA30E (KRÜSS) to evaluate wettability of samples. The samples, cut into 3 × 3 cm squares and placed on a microscope slide to ensure a stable and uniform surface. A 5 µL deionized water droplet was dispensed onto the sample surface using the instrument’s built-in dosing system. The contact angle was then recorded using the system camera and analyzed with the integrated software, with measurements recorded at room temperature and in repetition for accuracy.

Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy

Ultraviolet-visible (UV–Vis) spectra were recorded over a 190–400 nm wavelength range with HACH LANGE UV-VIS DR 6000 spectrophotometer. Background correction was applied to ensure accurate spectral readings.

Synthesis of β-CD-acrylate (β-CD-Acr)

The CD derivative was prepared following the procedure described in the work by Slavkova et al.45. Dried β-CD (10.0 g; 8.81 mmol) was dissolved in 75 ml of DMF, followed by the addition of TEA (8.9 ml; 61.76 mmol). The solution was cooled down to 0 °C using an ice bath, and acryloyl chloride (4.98 ml; 61.67 mmol) was added dropwise. The reaction was stirred at 800 rpm for 24 h at room temperature. After, the mixture was filtered off, and the solution was concentrated by rotary evaporation before precipitation into a 10-fold excess of acetone, which was recovered via filtration. Finally, the product (9.8 g) obtained as a yellow-tinted fine powder. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H+] Calculated for C45H72O36, C48H74O37, C51H76O38, C54H78O39 (for mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra-substituted CD respectively) 1189.387, 1243.398, 1297.409, 1351.419; Found 1189.3924, 1243.4029, 1297.4152, 1351.4273. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 6.55–5.89 (3 H, CH=CH2), 5.42–4.89 (7 H, H1), 4.72–3.44 (42 H, H2-H6). 13C{1H} CP/MAS NMR (101 MHz): δ 167 (C=O), 137–126 (C=C), 103.4 (C1), 83.2 (C4), 73.3 (C2, C3, C5), 67−57 (C6).

Polymerization of β-CD-acrylate (β-CD-Acr polymer)

β-CD-Acr was polymerized via free radical polymerization using 2,2′-azobis(2-methylpropionitrile) (AIBN). β-CD-Acr (5.00 g) was first dissolved in water (150 ml), followed by the addition of AIBN (0.063 g; 0.38 mmol). The reaction was stirred at 800 rpm and refluxed for 24 h. Upon the termination of the reaction, the resulting yellow-tinted powder was obtained via filtration, thoroughly rinsed with water, and dried at room temperature, yielding 4.8 g of the final product. 13C{1H} CP/MAS NMR (101 MHz): δ 175.6 (C=O), 137–127 (C=C), 103.0 (C1), 82.6 (C4), 73.2 (C2, C3, C5), 67−57 (C6), 53–22 (CH2-CH).

Polymerization of β-CD-acrylate onto PVDF nanofibers (CD-Acr-PVDF NFs)

A similar polymerization process described above was performed in situ with PVDF NFs. PVDF NFs (31.05 mg) were firstly wetted using isopropanol (IPA) and water, then immersed into water (20 ml) containing β-CD-Acr (220 mg). 7.5 mg of AIBN was firstly dissolved in 2.5 ml IPA and added to the reaction flask containing PVDF and β-CD-Acr monomer, left to react at 110 °C for 24 h. After the completion of the reaction, the NFs were washed in triplicate with excess distilled water and IPA, with a final rinse in IPA followed by drying at 75 °C for 18 h, resulting in NFs weighing 53.21 mg to be obtained. 13C{1H} HahnEcho/MAS NMR (101 MHz): δ 175.4 (C=O), 119.3 (CF2), 102.3 (C1), 82.1 (C4), 72.5 (C2, C3, C5), 67–56 (C6), 43.2 (CH2), 50−18 (CH2-CH).

Adsorption behavior in batch mode

The adsorption behavior of the β-CD-Acr polymer for PMV was investigated by performing batch experiments. The study evaluated the effects of adsorbent mass, pH, contact time, and the initial drug concentration on adsorption performance. The concentration of PMV in solution was measured using UV–Vis spectroscopy at λmax = 223 nm. All samples were rocked at ambient temperature for the given exposure times. To remove any absorbance from CD polymer, the β-CD-Acr polymer samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 rcf before recording PMV concentrations. The CD-Acr-PVDF NFs were observed to contain no absorbance signals in negative control measurements, and therefore, the PMV concentration could be recorded directly.

The adsorption capacity q (mg/g) was calculated using (Eq. 1) where C0 and Ce are the initial and equilibrium concentrations of the drug (mg/L), respectively, V is the volume of the drug solution (L), and m is the weight of the adsorbent (g). In addition, the removal efficiency (%) was determined by comparing C0 and Ce, as shown in (Eq. 2):

Adsorption kinetics and equilibrium isotherms

The adsorption kinetics for the CD-Acr-PVDF NFs with PMV was undertaken continuously from a single vessel, whereby the β-CD-Acr polymer samples needed to be undertaken in individual vessels due to the need for centrifugation before measurements. Both CD-Acr-PVDF NFs and β-CD-Acr polymer were exposed to a 21 mg/L solution of PMV adjusted to a CD polymer concentration of 0.1 mg/mL (typically using a CD polymer mass close to 1 mg). Equilibrium isotherm measurements were undertaken in a similar manner as the kinetics experiment described, albeit the concentration of PMV was adjusted periodically (from 0 to 300 mg/L), with the exposure time set to 18 h. All samples described were prepared in triplicate, with the average and standard deviation determined.

Adsorption kinetics were analyzed using the pseudo-second-order model. The model is expressed by (Eq. 3), where qt (mg/g) represents the amount of adsorbate adsorbed at time t, qe is the equilibrium adsorption capacity (mg/g), and k2 is the rate constant (g/mg·min)46,47.

Sips isotherm modeling was used to express the dynamic equilibrium between the concentration of the remaining drug in the bulk solution and the concentration of the retained drug onto the adsorbent-solution interface at constant temperature and pH represented by (Eq. 4) where qe is the amount of adsorbate adsorbed by unit mass of adsorbent at equilibrium (mg/g), qmax is maximum adsorption capacity, Ce is the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate in the solutions, KS is the Sips equilibrium constant (L/mg), and n is the heterogeneity factor indicating deviation of Langmuir behavior with a value between 0 and 148,49.

Result and discussion

Synthesis of β-CD-Acr monomer and polymer

The preparation of β-cyclodextrin-acrylate followed a previously established methods45,50, resulting in a similar yield of the product. 1H NMR spectral analysis is as expected for a randomly substituted β-CD moiety whereby significant broadening and shifts from all β-CD proton peaks are observed, with distinct peaks characteristic of the acryloyl group on β-CD readily seen (Fig. 1). Obtained NMR spectra correspond well with previously reported β-cyclodextrin-acrylate using this synthetic methodology50, describing the acrylate potentially substituing all positions (i.e. on positions 2,3, or 6) on β-CD (Fig. S5a–c). Relative integration of these acryloyl proton peaks compared to H1 protons of the β-CD were used to determine the degree of substitution (whereby DS = 3.3). HRMS indicated a mixture of β-CD-Acr with different degrees of acryloyl substitution, in agreement with 1H NMR spectral analysis, with the ratio of 3.3:1 (acryloyl:β-CD) determined and used for all subsequent calculations (Fig. S1). Scheme 1 shows the acylation reaction and the resulting β-CD-acrylate derivatives.

The β-CD-acrylate monomer underwent free radical polymerization (FRP) in an aqueous solution using AIBN under reflux conditions. Precipitation was observed to start after 20 min which continued to accumulate throughout the reaction, with the resulting yellowish precipitant insoluble in water. The polymerization process was confirmed through solid-state 13C solid-state NMR analysis, compared directly with the (non-polymerized) monomer. 13C CP/MAS NMR spectrum of the β-CD-Acr revealed a broad peak centered at 167 ppm, corresponding to the carbonyl group, and a broad overlapping signal between 136 and 126 ppm for the C=C bond (Fig. 2). A significant diminishment in this C=C signal, along with a downfield shift of the carbonyl peak, and the appearance of a broad C–C signal between 50 and 20 ppm are observed when the monomer undergoes polymerization (Fig. 2). Given the variability in acryloyl substitution of the β-CD monomer, the synthesized polymer is expected to be a cross-linked structure resulting from FRP. The resulting polymer network is mechanically interlocked within the nanofiber matrix, providing enhanced structural stability and preventing polymer leaching by physically entangling the polymer chains within the nanofibers39.

Polymerization of β-CD-Acr into PVDF nanofibers

FTIR spectra analysis of the CD-Acr-PVDF NFs showed a prominent carbonyl group at approximately 1740 cm− 1, indicating the presence of the β-CD-Acr polymer (Fig. S2). Additionally, SEM provided further validation for the attachment and coating of the polymer onto the nanofibers, with noticeable textural changes to the NFs surface indicative of alteration (Fig. 3). Hence, the adhesion of the cyclodextrin component can be partially explained by the mechanical interlocking theory, which operates on a macroscopic scale where particles of the CD polymers are trapped within the PVDF nanofibers39,51,52. The intermolecular forces, particularly hydrogen bonding, play a crucial role in facilitating this adhesion. As with the synthesized β-CD-Acr polymer described above, the β-CD-Acr FRP onto the PVDF NFs are expected to be highly cross-linked with the polymer physically attached to the PVDF NFs.

The wetting properties of the functionalized NFs were analyzed using water contact angle measurements (WCA) before and after the in-situ polymerization. The results showed a significant decrease in the WCA, reducing from approximately 160 to 40 degrees (Fig. 4). PVDF polymer is known for its inherent hydrophobicity, which can be a drawback of its utilization as an adsorbent mat in a water medium. However, through CD modification, these hurdles are overcome. The substantial reduction suggests an acquired hydrophilic quality in the nanofibers, making the NFs suitable for use as an adsorption system in water.

To quantify cyclodextrin content within the PVDF nanofiber, the modified samples were analyzed using 13C HahnEcho/MAS SS NMR measurements. The relative integrals from the signal corresponding to CF2 of the PVDF NFs (115–140 ppm) were compared with cyclodextrin signals corresponding to C2–C6 (55–90 ppm), giving a ratio of CF2 to CD of 30 to 1 (Fig. 5). These signals were chosen to compare due to the strong signals with minimal overlapping of other carbons, albeit the CF2 was deconvoluted. From the determined ratio, the polymer structure with the established DS of 3.3, gives the weighted mass percentage of CD present being 40.6%, corresponding closely with the 41.6% determined from weighing the samples. Scheme 2 illustrates the functionalization steps i.e. coating via FRP of the PVDF nanofibers.

Surface area (BET) analysis

The BET specific surface area measurements were determined for pristine PVDF NFs (9.24 m2/g), CD polymer powder (0.92 m2/g), and the CD functionalized PVDF NFs (5.01 m2/g) (Fig. S4). These results indicate that the CD polymerization onto the nanofibers reduced the specific surface area of the PVDF, however, the CD-Acr-PVDF nanofibers have a surface area approximately five times greater than that of the β-CD-Acr powder.

Adsorption experiments

Effect of adsorbent

Preliminary experiments indicated that β-CD-Acr polymer dosage of 0.1 mg per ml of PMV solution was sufficient for effective PMV adsorption, subsequently used for all adsorption experiments. When functionalized NFs (CD-Acr-PVDF NFs) were utilized, the mass of the sample, in conjunction with the previously calculated 41.6% mass of CD polymer present on the NFs, was used to determine the volume needed to result in a 0.1 mg/ml concentration, allowing for direct comparison with the β-CD-Acr polymer measurements. With the FRP of the β-CD-Acr monomer forming a highly crosslinked polymeric structure, the specific molecular weights obtained are not believed to influence the adsorption properties of the sorbents formed.

Effect of pH: β-CD-Acr polymer in suspension

The effect of pH on the removal efficiency of PMV by the β-CD-Acr polymer is demonstrated in (Fig. 6). It can be seen that in harsh acidic environments, the removal efficiency is relatively low, with PMV reaching 56%. This reduced efficiency is likely due to the protonation of the drug molecules and the adsorbent surface, leading to repulsion and weaker adsorption interactions. As the pH approaches neutral, the β-CD-Acr system showed a significant improvement in performance, reaching 100% efficiency. The system maintained high performance at higher pH values up to pH 10 but showed a slight decrease at pH 11, reaching about 80%. The high removal efficiency at a neutral pH environment can be attributed to the β-CD-Acr polymer sorbent and the drug being in their optimal ionization states, which enhances electrostatic interactions and adsorption efficiency. At extremist pH levels, changes in ionization may reduce these interactions in acidic conditions and at pH 11, leading to lower efficiency.

Such a broad functional pH range is advantageous, as it aligns with the pH range of wastewater in general as well as with the pH operating conditions of various wastewater treatment processes53. This compatibility makes it feasible to integrate this adsorbent system into any stage of the treatment process without the need for extensive pH adjustments, thereby simplifying operational requirements.

Adsorption kinetics of β-CD-Acr polymer vs. CD-Acr-PVDF NFs

Adsorption kinetic for CD-Acr-PVDF NFs and β-CD-Acr polymer were studied and found to follow the pseudo-second-order kinetic model (Eq. 3), as indicated by the modeled fitting’s high degree of correlation with the experimental data (whereby R2 = 0.999 and 0.883 for CD-Acr-PVDF NFs and β-CD-Acr polymer, respectively). This suggests that the adsorption behavior observed can be effectively described by a model typically associated with strong interactions46. The equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) for CD-Acr-PVDF NFs was noticeably higher (56.2 ± 0.3 mg/g) than that of β-CD-Acr polymer (34.2 ± 3.7 mg/g). This improvement indicates that coating the polymer onto the nanofiber led to a kinetic advantage. The enhanced adsorption can be attributed to the increased surface area of the NFs, which provides better exposure and accessibility of the cyclodextrin’s cavities and polymer functionality resulting in higher uptake of PMV. The CD-Acr-PVDF NFs also exhibited faster initial adsorption rate, as reflected by the higher pseudo-second rate constant (k2 = 0.0499 g/mg h) compared to the β-CD-Acr polymer (k2 = 0.0090 g/mg h), suggesting that CD-Acr-PVDF NFs have quicker initial interactions with PMV (Fig. 7a), once again due to the NFs higher surface area.

Further, the adsorption mechanisms of both systems rely primarily on the guest-host property of the β-cyclodextrin component and the functional groups within the polymer backbone, which collectively expected to generate strong interactions with the drug. This provides a rationale for the good agreement of the experimental data with the pseudo-second-order model, commonly interpreted as indicative of chemisorption-controlled kinetics46.

(a) Adsorption kinetics of PMV onto PVDF nanofibers coated with β-CD-Acr polymer (CD-Acr-PVDF) (orange) and β-CD-Acr polymer alone (green); Experimental data were fitted using pseudo-second order kinetic model (solid lines). (b) Adsorption equilibrium isotherms of PMV onto CD-Acr-PVDF NFs (orange), and β-CD-Acr polymer (green) at 25 °C and 18-h equilibration time. Experimental data were fitted using the Sips isotherm model (solid lines). Data points are an average from 3 samples (± standard deviation). This graph was generated using Origin software.

Adsorption equilibrium of β-CD-Acr polymer vs. CD-Acr-PVDF NFs

The adsorption equilibrium of PMV onto both systems was investigated and found to closely follow the Sip’s isotherm model (Eq. 4), being a combination of Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms often used to describe adsorption in heterogeneous systems48. The model also accounts for strong interactions between adsorbate and adsorbent, as it is fundamentally rooted in the Freundlich isotherm49. The high correlation between modeling and experimental data for both adsorbent materials confirms that adsorption equilibrium can be effectively described (Fig. 7b).

The maximum adsorption capacities (qmax) obtained from the Sips model were: 113.6 (± 13.1) mg/g(CD-Polymer) for CD-Acr-PVDF NFs and 54.8 (± 2.0) mg/g(CD-Polymer) for β-CD-Acr polymer, indicating a notably higher adsorption capacity for the nanofiber system. Further, the Sip’s isotherm constant (K) and the heterogeneity index (n) were 0.0693 (± 0.029) and 0.85 (± 0.19) for CD-Acr-PVDF NFs, and 0.0625 (± 0.029) and 1.32 (± 0.22) for β-CD-Acr polymer, respectively.

The adsorption contributions from β-CD cavity inclusion, van der Waals forces, and hydrogen-bonding interactions in the polymeric matrix are consistent with the observed fit to the Sips model, which can describe systems with a distribution of adsorption site affinities. In both hybrid sorbent systems, the heterogeneity index (n < 1) reflects the coexistence of multiple types of binding sites and supports the notion that both physical and quasi-chemical interactions collectively influence the overall adsorption behavior48. The lower heterogeneity index observed in the case of coating the polymer onto NFs suggests a more heterogeneous surface with a broader distribution of binding sites and affinities54. This may be attributed to the nanoscale architecture from the fibers making the CD more accessible, which could also contribute to the observed higher adsorption kinetics described previously.Moreover, compared to the cyclodextrin-based nanosponge adsorbents reported by Hemine et al., which exhibited maximum adsorption capacities for PMV of approximately 52.08 mg/g (β-nanosponge) and 23.26 mg/g (γ-nanosponge)11, the CD-Acr-PVDF nanofiber system demonstrates a significantly enhanced adsorption capacity. This improvement further highlights the advantage of incorporating the polymer into a nanofiber matrix, providing superior surface area and accessibility for effective pollutant removal.

Cyclodextrin–pimavanserin inclusion complex

To gain insights into the adsorption mechanism of PMV with the β-CD-acrylate polymer, the formation of the inclusion complex between PMV and β-CD-acrylate monomer was investigated through 1H NMR spectroscopy, and 2D ROESY analysis to determine molecular interactions.

1H NMR shows that upon complexation, significant broadening and chemical shift changes occur in both the β-CD-Acr monomer and in PMV signals i.e. broadening of the CH2 = CH2 moiety and β-CD-Acr protons (H2–H6), and noticeable shift of PMV signals corresponding to IV, V, VII, IX protons (Fig. 8a). On the other hand, the ROESY spectrum of the inclusion complex reveals a correlation between β-CD-acrylate monomer’s protons H2-H6 of β-CD and PMV’s IV and V protons (Fig. 8b). The PMV protons correlation with the internal cavity (H3 and H5) protons in particular suggests that PMV is not interacting at the surface but rather experiences guest–host encapsulation within the cyclodextrin cavity. The mode of inclusion is likely driven by hydrophobic interactions between the non-polar regions of PMV and the inner hydrophobic cavity of β-CD, while the fluorinated part remains exposed. The absence of cross peaks corresponding to the CH2=CH2 suggests that the acrylic moiety has no significant influence on the adsorption capability of the system (Fig. 8b). These analyses provide definitive evidence of PMV successful encapsulation within the β-CD-acrylate monomer. Similar inclusion phenomena of PMV have been reported by Hemine et al.11, who utilized ROSEY analyses to confirm the encapsulation within native β and γ-cyclodextrins. Although their study featured native β-CD, the observed inclusion behavior appears nearly identical to this work utilizing β-CD-Acr. The NMR spectral assignment of PMV as well as in ROESY spectra was based on that of previously published results11.

The isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) results provide complementary evidence for the inclusion complex of PMV and β-CD-acrylate monomer (Fig. S3). The binding isotherm exhibits a characteristic sigmoidal curve indicating a host-guest interaction with a nearly 1:1 binding ratio (n = 0.95) confirming that each β-CD monomer accommodates a single PMV molecule. The initial sharp increase in heat change corresponds to strong binding at low PMV concentrations, followed by a gradual transition as the available binding sites become saturated. The plateau reflects the completion of the complexation process, where additional PMV molecules no longer contribute significantly to heat change. The binding constant (K2 = 5180 M−1) indicates a moderate affinity, consistent with β-CD-based inclusion complexes, where hydrophobic interactions primarily drive encapsulation. The negative Gibbs free energy (ΔG = − 21.2 kJ/mol) confirms that the binding process is spontaneous, while the negative enthalpy change (ΔH = − 16.0 kJ/mol) suggests that hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces contribute to the interaction55.

The complexation insights revealed by NMR and ITC studies, provide only partial explanation for the adsorption mechanism by confirming the formation of the guest-host complex between the PMV and β-CD part. However, the adsorption behavior in the polymeric state appears to be influenced by additional factors beyond encapsulation. The fact that adsorption equilibrium studies follow the Sips isotherm model, as well as pseudo-second order model in kinetics studies which both suggest chemisorption-like behavior (Fig. 7), implies that the polymer structure itself plays a role in enhancing adsorption. While the acrylic functionality did not significantly impact molecular encapsulation in solution, as indicated by the absence of CH2=CH interactions in ROESY (Fig. 8b), its role in the solid polymeric state remains a key consideration. The acrylate polymer backbone may contribute to adsorption through non-specific interactions, potentially increasing the retention of PMV. Thus, adsorption within the polymeric network is not solely reliant on cyclodextrin complexation, additional binding mechanisms could be involved, which had also been suggested for an alternate CD polymer by Hemine et al.11.

(a) 1H NMR spectra of PMV (top, black), β-CD-acrylate monomer (middle, red), and the inclusion complex of PMV with β-CD-acrylate monomer (bottom, green). (b) 2D ROESY spectrum of the inclusion complex. (c) Molecular structure of PMV, with labeled protons corresponding to their NMR assignments. Assignment of PMV in 1H NMR and ROESY was done in accordance with11.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of the synthesized β-CD-Acr polymer as an adsorption system for PMV removal from water, both in powder form and when coated onto PVDF nanofibers.To the best of our knowledge, this β-CD-Acr polymer is novel and has not been previously reported, which adds a distinctive element of originality to this work. The system maintained high functionality across a broad range of pH values and pollutant concentrations. The kinetic analysis highlighted the advantages of the PVDF-supported system, which achieved a notably higher equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe = 56.2 mg/g) compared to the powder form (qe = 34.2 mg/g), enabling faster and more efficient pollutant removal. These findings are further supported by the higher maximum adsorption capacities obtained from equilibrium isotherm modeling (qmax = 113.6 mg/g for CD-Acr-PVDF NFs and 54.8 mg/g for β-CD-Acr polymer), confirming the superior uptake potential of the nanofiber system. The accelerated adsorption rate, combined with enhanced capacity, underscores the potential of engineered nanofiber composites as high-performance adsorbents for advanced water treatment technologies, offering scalable and efficient solutions for environmental and industrial pharmaceutical removal. Moreover, this polymer coating method is highly versatile, as the β-CD-Acr monomer can be polymerized onto various polymeric substrates such as polyamide, polysulfones, and polyacrylonitrile—materials widely used in water treatment applications56,57. Additionally, the system can be applied to remove a broader spectrum of contaminants, as cyclodextrins exhibit strong adsorption capabilities for various organic pollutants, including pharmaceutical residues, dyes, and persistent organic pollutants43,58. Future studies will explore a wider range of pharmaceuticals, and the impact of competing ions will also be investigated to assess the scalability and applicability of the system for practical implementation in environmental remediation. Integrating cyclodextrins onto electrospun nanofibers presents an innovative strategy for developing advanced solutions in water purification and environmental remediation.

Data availability

The experimental data measured and analyzed during this study are openly available in the on-line repository: https://doi.org/10.48700/datst.2bvar-xpj85. These data include measurements supporting the findings presented in this manuscript.

References

Damania, R., Desbureaux, S., Rodella, A. S., Russ, J. & Zaveri, E. Quality Unknown: The Invisible Water Crisis (World Bank, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1459-4

Rivera-Utrilla, J., Sánchez-Polo, M., Ferro-García, M. Á., Prados-Joya, G. & Ocampo-Pérez, R. Pharmaceuticals as emerging contaminants and their removal from water. A review. Chemosphere. 93, 1268–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.07.059 (2013).

Kim, K. Y., Ekpe, O. D., Lee, H. J. & Oh, J. E. Perfluoroalkyl substances and pharmaceuticals removal in full-scale drinking water treatment plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 400, 123235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123235 (2020).

Wilkinson, J. L. et al. Pharmaceutical pollution of the world’s rivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2113947119 (2022).

Pharmaceutical Residues in Freshwater, OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/c936f42d-en (2019).

González-González, R. B. et al. Persistence, environmental hazards, and mitigation of pharmaceutically active residual contaminants from water matrices. Sci. Total Environ. 821, 153329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153329 (2022).

Ortúzar, M., Esterhuizen, M., Olicón-Hernández, D. R., González-López, J. & Aranda, E. Pharmaceutical pollution in aquatic environments: A concise review of environmental impacts and bioremediation systems. Front. Microbiol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.869332 (2022).

Hunter, N. S., Anderson, K. C. & Cox, A. Pimavanserin, drugs of today. 51 645. https://doi.org/10.1358/dot.2015.51.11.2404001 (2015).

Yunusa, I., El Helou, M. L. & Alsahali, S. Pimavanserin: A novel antipsychotic with potentials to address an unmet need of older adults with dementia-related psychosis. Front. Pharmacol. 11 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.00087 (2020).

Kurhan, F. & Akın, M. A new hope in alzheimer’s disease psychosis: Pimavanserin, curr. Alzheimer Res. 20, 403–408. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205020666230825124922 (2023).

Hemine, K., Skwierawska, A., Kernstein, A. & Kozłowska-Tylingo, K. Cyclodextrin polymers as efficient adsorbents for removing toxic non-biodegradable Pimavanserin from pharmaceutical wastewaters. Chemosphere. 250, 126250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126250 (2020).

Su, D. et al. Projections for prevalence of parkinson’s disease and its driving factors in 195 countries and territories to 2050: modelling study of global burden of disease study 2021. BMJ. 388 https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ-2024-080952 (2025).

Pimavanserin Market Size. (n.d.). Share & Trends Analysis (2033). https://www.marketresearchintellect.com/product/global-pimavanserin-market/ (accessed 13 July 2025).

Eniola, J. O., Kumar, R., Barakat, M. A. & Rashid, J. A review on conventional and advanced hybrid technologies for pharmaceutical wastewater treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 356, 131826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131826 (2022).

Kanakaraju, D., Glass, B. D. & Oelgemöller, M. Advanced oxidation process-mediated removal of pharmaceuticals from water: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 219, 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.04.103 (2018).

Gopalakrishnan, G., Jeyakumar, R. B. & Somanathan, A. Challenges and emerging trends in advanced oxidation technologies and integration of advanced oxidation processes with biological processes for wastewater treatment. Sustainability. 15, 4235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054235 (2023).

Kujawska, A., Kiełkowska, U., Atisha, A., Yanful, E. & Kujawski, W. Comparative analysis of separation methods used for the elimination of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) from water—A critical review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 290, 120797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120797 (2022).

Taoufik, N., Boumya, W., Achak, M., Sillanpää, M. & Barka, N. Comparative overview of advanced oxidation processes and biological approaches for the removal pharmaceuticals. J. Environ. Manag. 288, 112404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112404 (2021).

Nasrollahi, N., Vatanpour, V. & Khataee, A. Removal of antibiotics from wastewaters by membrane technology: Limitations, successes, and future improvements. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 156010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156010 (2022).

Ferreira, I. A., Carreira, T. G., Diório, A., Bergamasco, R. & Vieira, M. F. Occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals from water using modified zeolites: a review, desalin. Water Treat. 302, 171–183. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2023.29762 (2023).

Mansouri, F., Chouchene, K., Roche, N. & Ksibi, M. Removal of pharmaceuticals from water by adsorption and advanced oxidation processes: state of the Art and trends. Appl. Sci. 11, 6659. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11146659 (2021).

Al-sareji, O. J. et al. Removal of emerging pollutants from water using enzyme-immobilized activated carbon from coconut shell. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 109803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.109803 (2023).

Sophia, C. & Lima, A. E. C. Removal of emerging contaminants from the environment by adsorption. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 150, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.12.026 (2018).

Karimi-Maleh, H. et al. Recent advances in using of chitosan-based adsorbents for removal of pharmaceutical contaminants: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 291, 125880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.125880 (2021).

Quesada, H. B. et al. Surface water pollution by pharmaceuticals and an alternative of removal by low-cost adsorbents: A review. Chemosphere 222, 766–780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.02.009 (2019).

Zhai, M. et al. Simultaneous removal of pharmaceuticals and heavy metals from aqueous phase via adsorptive strategy: A critical review. Water Res. 236, 119924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2023.119924 (2023).

Alfonso-Muniozguren, P., Serna-Galvis, E. A., Bussemaker, M., Torres-Palma, R. A. & Lee, J. A review on pharmaceuticals removal from waters by single and combined biological, membrane filtration and ultrasound systems. Ultrason. Sonochem. 76, 105656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105656 (2021).

Qalyoubi, L., Al-Othman, A. & Al-Asheh, S. Recent progress and challenges of adsorptive membranes for the removal of pollutants from wastewater. Part II: environmental applications, case stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 3, 100102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscee.2021.100102 (2021).

Qalyoubi, L., Al-Othman, A. & Al-Asheh, S. Recent progress and challenges on adsorptive membranes for the removal of pollutants from wastewater. Part I: fundamentals and classification of membranes, case stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 3, 100086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscee.2021.100086 (2021).

Chong, W. C., Choo, Y. L., Koo, C. H., Pang, Y. L. & Lai, S. O. Adsorptive membranes for heavy metal removal—A mini review. 020005. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5126540 (2019).

Vo, T. S., Hossain, M. M., Jeong, H. M. & Kim, K. Heavy metal removal applications using adsorptive membranes. Nano Converg. 7, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40580-020-00245-4 (2020).

Cui, Z., Drioli, E. & Lee, Y. M. Recent progress in fluoropolymers for membranes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 39, 164–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.07.008 (2014).

Zou, D. & Lee, Y. M. Design strategy of poly(vinylidene fluoride) membranes for water treatment. Prog. Polym. Sci. 128, 101535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2022.101535 (2022).

Saxena, P. & Shukla, P. A comprehensive review on fundamental properties and applications of poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF). Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 4, 8–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-021-00217-0 (2021).

Mohammadpourfazeli, S. et al. Future prospects and recent developments of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) piezoelectric polymer; fabrication methods, structure, and electro-mechanical properties. RSC Adv. 13, 370–387. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2RA06774A (2023).

Liu, F., Hashim, N. A., Liu, Y., Abed, M. R. M. & Li, K. Progress in the production and modification of PVDF membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 375, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2011.03.014 (2011).

Kang, G. & Cao, Y. Application and modification of poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) membranes—A review. J. Memb. Sci. 463, 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2014.03.055 (2014).

Ahmed, M. M. et al. Revisiting the polyvinylidene fluoride heterogeneous alkaline reaction mechanism in propan-2-ol: an additional hydrogenation step. Eur. Polym. J. 156, 110605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2021.110605 (2021).

Ahmed, M. M., Nowacka, D., Skwierawska, A. M. & Řezanka, M. Cyclodextrins functionalized polyvinylidene fluoride membranes: strategies and diverse applications. Tetrahedron 134385 https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TET.2024.134385 (2024).

Chen, C. et al. A high absorbent PVDF composite membrane based on β-cyclodextrin and ZIF-8 for rapid removing of heavy metal ions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 292 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120993 (2022).

Kong, F. et al. Rejection of pharmaceuticals by graphene oxide membranes: role of crosslinker and rejection mechanism. J. Memb. Sci. 612 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2020.118338 (2020).

Ndlovu, L. N. et al. Beta cyclodextrin modified polyvinylidene fluoride adsorptive mixed matrix membranes for removal of congo red. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 139 https://doi.org/10.1002/app.52302 (2022).

Wacławek, S. et al. Cyclodextrin-based strategies for removal of persistent organic pollutants. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 310, 102807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2022.102807 (2022).

Řezanka, M. Monosubstituted cyclodextrins as precursors for further use. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 5322–5334. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.201600693 (2016).

Iv Slavkova, M., Momekova, D. B., Kostova, B. D., Tz Momekov, G. & Petrov, P. D. Novel dextran/β-cyclodextrin and dextran macroporous cryogels for topical delivery of Curcumin in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (2017).

Ho, Y. & McKay, G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process. Biochem. 34, 451–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-9592(98)00112-5 (1999).

Revellame, E. D., Fortela, D. L., Sharp, W., Hernandez, R. & Zappi, M. E. Adsorption kinetic modeling using pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order rate laws: A review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 1, 100032. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CLET.2020.100032 (2020).

Belhachemi, M. & Addoun, F. Comparative adsorption isotherms and modeling of methylene blue onto activated carbons. Appl. Water Sci. 1, 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-011-0014-1 (2011).

Foo, K. Y. & Hameed, B. H. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 156, 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2009.09.013 (2010).

Cao, Y. et al. Synthesis and antimicrobial applications of the inclusion complexes of β-cyclodextrin copolymers with potassium sorbate. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 135, 46885. https://doi.org/10.1002/APP.46885;WGROUP:STRING:PUBLICATION (2018).

Jialanella, G. L. Advances in bonding plastics. In Adv. Struct. Adhes. Bond., 237–264. https://doi.org/10.1533/9781845698058.2.237 (Elsevier, 2010).

Omar, H. A., Yusoff, N. I. M., Mubaraki, M. & Ceylan, H. Effects of moisture damage on asphalt mixtures. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (English Ed.) 7, 600–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtte.2020.07.001 (2020).

Metcalf & Eddy Wastewater Engineering Treatment and Resource Recovery, 5th edn (McGraw-Hill Education, 2014).

Fagundez, J. L. S., Netto, M. S., Dotto, G. L. & Salau, N. P. G. A new method of developing ANN-isotherm hybrid models for the determination of thermodynamic parameters in the adsorption of ions Ag+, Co2 + and Cu2 + onto zeolites ZSM-5, HY, and 4A. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 106126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2021.106126 (2021).

Callies, O., Hernández, A. & Daranas Application of isothermal titration calorimetry as a tool to study natural product interactions. Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 881–904. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5NP00094G (2016).

Zamel, D. & Khan, A. U. New trends in nanofibers functionalization and recent applications in wastewater treatment. Polym. Adv. Technol. 32, 4587–4597. https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.5471 (2021).

El-Aswar, E. I., Ramadan, H., Elkik, H. & Taha, A. G. A comprehensive review on preparation, functionalization and recent applications of nanofiber membranes in wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Manag. 301, 113908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113908 (2022).

Okasha, A. T. et al. Progress of synthetic cyclodextrins-based materials as effective adsorbents of the common water pollutants: comprehensive review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 109824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.109824 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the Student Grant Competition of the Technical University of Liberec under the project No. SGS-2021-4026, by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic and the European Union-European Structural and Investment Funds in the frames of Operational Programme Research, Development and Education-project Hybrid Materials for Hierarchical Structures (HyHi, Reg. No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000843), and from the Research Infrastructure NanoEnviCz, supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic under Project No. LM2023066.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing-original draft. C.J.H.: Investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing-review and editing. A.M.S.: Methodology, writing-review and editing. M.Ř.: Conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisitions, writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, M.M., Hobbs, C.J., Schmidt, A.M. et al. Adsorptive removal of pimavanserin from water using β-cyclodextrin polymer coated PVDF nanofibers. Sci Rep 15, 38387 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22227-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22227-4