Abstract

Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (LFS) is a severe cancer predisposition syndrome caused by germline TP53 variants and characterized by a wide range of cancers. The TP53 variant p.R181H is enriched in the Swedish germline TP53 cohort and has distinct phenotypical characteristics. Using our nationwide Swedish germline TP53 database (SWEP53, 189 individuals, 86 families), p.R181H was identified in 22% of families (19/86), compared to just 0.6% in the National Cancer Institute (NCI) TP53 database (8/1360). Notably, p.R181H carriers had lower cancer incidence and better survival than carriers of other TP53 variants (both p < 0.0001). Female carriers primarily developed breast cancer (earliest onset 29 years), males mainly prostate cancer (earliest onset 45 years), and no cancers were observed in children. The results were confirmed using the NCI TP53 database. Tumor sequencing confirmed loss of heterozygosity. Additionally, haplotype analysis suggests that p.R181H is a potential Swedish founder variant, estimated to be ~ 550 years old. These findings indicate that, for p.R181H carriers, tailored surveillance could focus on adults by omitting children from testing and surveillance, and by targeting prevention and detection to breast cancer in females and prostate cancer in males. Validation in independent cohorts is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (LFS), also known as heritable TP53-related cancer syndrome (hTP53rc), is a hereditary cancer predisposition syndrome caused by germline variants in the tumor suppressor gene TP531,2. The syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and the lifetime cancer risk is approximately 70% for males and close to 100% for females3,4. Moreover, approximately 50% of affected individuals who develop an initial malignancy will develop a subsequent primary cancer5. Adrenocortical carcinomas (ACC), breast cancers, central nervous system (CNS) tumors, osteosarcomas and soft-tissue sarcomas represent the most frequently observed malignancies and are therefore considered the core cancers of LFS. However, the cancer spectrum is broad and includes a variety of other malignancies, such as leukemia, lung cancer, and skin cancer6,7. LFS patients also display a heterogenous temporal spectrum with certain variants associated with earlier onset of first cancer8. Due to the extreme lifetime cancer risk, current international guidelines recommend intensive tumor screening programs including whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (WB-MRI), abdominal ultrasounds and clinical check-ups. Unfortunately, these screening programs are often one-size-fits-all and fail to take into consideration the various cancer spectra and temporal distribution exhibited by different TP53 variants1,9.

There is a wide spectrum of TP53 variants that are known to cause LFS, and cohorts usually show a large variant and phenotype heterogeneity. To date, more than 1,500 unique TP53 germline variants have been reported in the National Cancer Institute (NCI) TP53 database10. In certain populations specific germline variants can be enriched and observed in a higher frequency than expected. These variants are known as founder variants and originate from a common ancestor in a specific geographical region. Founder variants share the same haplotype, which distinguishes them from hot-spot variants which are identified on different haplotype backgrounds10,11,12,13,14. Only a few founder variants in TP53 have been described15,16,17. The most studied founder variant, p.R337H, is prevalent in parts of Brazil and is thought to have originated from Portuguese migrants18,19. While p.R337H exhibits lower overall cancer penetrance, carriers have higher incidence of ACC, papillary thyroid cancer, renal cancers and lung adenocarcinomas compared to other TP53 variants. Similarly, the other founder variants in TP53 also exhibit a wide cancer spectrum necessitating the use of WB-MRI for tumor surveillance. Consequently, there are no founder variants with enough clinical homogeneity to enable personalized clinical management12,16,17,20,21,22.

Here, we used our Swedish germline TP53 database to identify p.R181H (NM_000546.6:c.542G>A) as a highly enriched variant in the Swedish population. Carriers of the variant exhibited a clinically distinct phenotype characterized by absence of childhood cancers, low cancer penetrance and significantly improved survival. Additionally, the cancer spectrum was narrow and dominated by breast and prostate cancer. The homogenous phenotype could therefore be exploited to enable personalized clinical management.

Methods

Swedish germline TP53 database (SWEP53)

Variant data and clinical data on Swedish LFS families were retrieved from the Swedish germline TP53 database (SWEP53, last update August 2024, 189 individuals from 86 families)23. The nationwide database includes all known TP53 carriers in Sweden with a likely pathogenic (class 4) or pathogenic (class 5) TP53 variant (Table S1)24,25. Patients with multiple variants are not included. Used variables from the database included variant data, pedigree, age at cancer onset, cancer type, pathological reports and survival data. All families were then classified into one of the phenotypical groups: classic LFS, Chompret or hereditary breast cancer (HBC). Families that could not be classified into either of the three phenotypical groups were classified as “other” (Table S2).

Publicly available datasets

The TP53 database (version R20, January 2024) hosted by NCI aggregates germline TP53 variant carriers from published literature since 1989. Data includes age at cancer onset, cancer type and survival information10. Data was retrieved in February 2024. Only individuals with confirmed or mandatory TP53 carriership that were classified as likely pathogenic (class 4) or pathogenic (class 5) were included, all patients with multiple TP53 variants were excluded. In total 1,995 individuals (1,360 families) were selected for further downstream analysis. All patients not classified as either classic LFS or Chompret were classified as “other” since the HBC phenotypical group is not used in the database. For analyses of cancer incidence using the NCI TP53 database, p.R181H carriers from the Swedish cohort were pooled with those from the NCI TP53 cohort to increase statistical power, as the number of p.R181H carriers in the NCI dataset alone was insufficient for robust analysis. The comparator group consisted of all other variant carriers within the NCI TP53 cohort. This allowed external confirmation of findings while avoiding cohort mixing in the comparator group. No survival data were available for p.R181H carriers in the NCI TP53 cohort; therefore, survival analyses included only Swedish p.R181H carriers, with the comparator group drawn from the NCI TP53 cohort. Additionally, we used variant frequency data from the NCI longitudinal Li-Fraumeni syndrome study which included a total of 480 carriers of likely pathogenic or pathogenic TP53 variants26.

For healthy (non-cancer) population allele frequencies, we used the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomad.broadinstitute.org version 2.1.1, non-cancer). Additionally, we used the FLOSSIES database (Fabulous Ladies Over Seventy) which contains data from targeted sequencing of 27 genes associated with breast cancer including TP53. In total 10,000 females, over the age of 70 years, who have never had cancer were included (whi.color.com).

Haplotyping and age estimation

Twelve short tandem repeat (STR) markers flanking the TP53 gene were analyzed (Table S3). All p.R181H variant carriers in the Swedish cohort with available leukocyte genomic DNA were analyzed (18 individuals from seven families). For all families, except family E (Table S3), samples from at least two generations were available, making it possible to better determine the haplotypes and sort the alleles. Primers for the STR markers were retrieved from the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) database and analyzed by conventional PCR and fragment length analysis (ABI3500XL, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The EstiAge software was used to estimate the age of the most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) based on the genetic distance of haplotypes sharing between independent families, assuming a 0.001 global mutation rate per meiosis. Each generation was assumed to be 25 years27.

AlphaMissense

The deleteriousness of the variant was computationally assessed using AlphaMissense, a deep learning model trained to predict pathogenicity based on protein sequence input28. The model was accessed through the web interface developed by Tordai et al. with variants classified into three categories according to their pathogenicity scores: benign/likely benign (0–0.34), uncertain significance (0.34–0.564), and likely pathogenic/pathogenic (0.564–1)29.

Tumor sequencing

DNA was purified from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue and sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) using a paired-end 150 nucleotide readout, aiming at 40 million read pairs per sample using a custom-designed hybridization capture gene panel (GMCKv1, Twist Bioscience) with 387 genes30. Data was analyzed using the Balsamic pipeline version 5.1.0. (https://balsamic.readthedocs.io/en/latest/) and visualized in SCOUT. Variants were manually checked using quality values (total depth > 100; variant depth > 10; variant allele frequency > 3%) and variant databases (gnomAD v2.1.1), Clinvar, COSMIC and our internal database.

Statistical analysis and visualization

Independent t-test was used for comparisons between two continuous variables when normally distributed. Chi-squared test was used for comparisons across two or more categorical variables if the expected value in each cell was higher than five, otherwise Fisher’s exact test was used. Overall survival and cumulative incidence were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test was used to calculate the p-values. All individuals, including those who did not develop cancer during follow-up, were included in the survival and cumulative incidence analyses. In cases where p.R181H carriers would otherwise have been included in a comparator group (e.g., HBC or missense groups), they were removed from that group to avoid overlap. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical computing was performed using the R programming language (version 4.2.2) in RStudio (version 2023.06). The package “dplyr” was used for data wrangling, “ggplot2” was used for creating figures and “survminer”, “survival” and “ggsurvfit” were used for survival analysis, Kaplan–Meier curves and cumulative incidence curves. Adobe Illustrator (version 28.6) was used for further figure annotation and layout adjustment.

Ethical considerations

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the by the regional ethical review board in Stockholm (2021/06932/02) and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2020-02826).

Results

Prevalence of p.R181H in Sweden and Northern Europe

The population frequency of p.R181H in different cohorts is summarized in Table 1. In the NCI Longitudinal LFS Study comprising 480 patients only eight were found to carry the variant p.R181H (1.7%). A similar proportion of p.R181H carriers is indexed in the NCI TP53 database of germline TP53 variant carriers (0.5% of individuals, 0.6% of families). Remarkably, 43 individuals (19 families) in the Swedish TP53 cohort carried the variant, constituting one quarter (23%) of all individuals and one fifth of all families (22%). Amongst healthy (non-cancer) individuals, the variant was reported in one individual in the FLOSSIES cohort (carrier frequency 0.01%) and four individuals in the non-cancer gnomAD database (carrier frequency 0.001%). Interestingly, the individual in FLOSSIES had European American ancestry and the four individuals in gnomAD all had North European ancestry with two being from Sweden, one from Estonia and one from an unspecified Northwestern European location.

In-silico prediction by AlphaMissense

AlphaMissense was used to computationally predict the pathogenicity of p.R181H. Six different missense variants are possible at this codon; p.R181C, p.R181G, pR181H, p.R181L, p.R181P and p.R181S. AlphaMissense calculates a mean pathogenicity score of 0.821 for these variants with a range of 0.59 to 0.952 (Table S4). Among these variants, the Swedish variant p.R181H is predicted to have the lowest pathogenicity score of 0.59 but is still considered likely pathogenic/pathogenic (cutoff for unknown significance < 0.564).

Loss of heterozygosity

Tumor DNA was available from two tumors (gastrointestinal stromal tumor and breast cancer, both at age 38 years) in one patient with the p.R181H germline variant in TP53. The p.R181H variant was detected in both tumors with high variant allele frequency (VAF) indicative of a loss of heterozygosity of the wild-type TP53 locus on the short arm of chromosome 17 as a second hit in the tumor (Table S5). This suggests, but does not definitively establish, a pathogenic role of p.R181H in tumorigenesis.

Distinct phenotypical characteristics

The lifetime risk for developing cancer was significantly lower in p.R181H carriers than carriers of other variants (p < 0.0001, Fig. 1a). For all comparisons, individuals were assigned exclusively to a single group; p.R181H carriers were excluded from comparator groups such as hereditary breast cancer (HBC) or missense to avoid overlap. The difference in cancer incidence persisted even when only comparing against other missense variants or only comparing against individuals classified with the HBC phenotype (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001, Fig. 1a). Furthermore, p.R181H was associated with a lower breast cancer incidence compared to all other variants as well as other HBC individuals (p = 0.045 and p = 0.004, Fig. 1b). The risk for all non-breast cancers was also significantly lower in carriers of p.R181H compared to; all other variants (p < 0.0001, Fig. 1c), all missense variants (p < 0.0001, Fig. 1c) and all patients classified as HBC (p = 0.0005, Fig. 1c).

Difference in lifetime cancer risk stratified by p.R181H carrier status in the Swedish cohort. (a) Cumulative all cancer incidence for all patients (all), carriers of missense variants (missense) and patients classified as hereditary breast cancer phenotype (HBC). (b) Cumulative breast cancer incidence for all patients (all), carriers of missense variants (missense) and patients classified as hereditary breast cancer phenotype (HBC). (c) Cumulative non-breast cancer incidence for all patients (all), carriers of missense variants (missense) and patients classified as hereditary breast cancer phenotype (HBC). Green indicates carriers of the TP53 p.R181H germline variant and red indicates carriers of any other class 4 or 5 TP53 variant. P-values calculated using log-rank test.

Mean age at first cancer onset was significantly higher in carriers of p.R181H (46 years old) compared to all other variant carriers (32 years old, p = 0.0001, Table 2). The density curve for p.R181H carriers is distinctly skewed to the right compared to other variant carriers (Fig. 2). The youngest patient with the p.R181H variant developed a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (her first non-breast malignancy) at the age of 38. (Individual ID 47, concurrent breast cancer, Table S6). In contrast, 33 patients carrying other variants than p.R181H developed non-breast cancers before the age of 38, with the youngest being four months old. Strikingly, none of the p.R181H carriers developed a childhood cancer (< 18 years old) compared to 19% of carriers of other variants (p = 0.02, Table 2). Only 7% of p.R181H carriers developed multiple primary cancers as compared to 25% in carriers of other variants (p = 0.01, Table 2).

Temporal distribution of age at first cancer onset in the Swedish cohort. (a) Carriers of p.R181H. (b) Carriers of all variants except p.R181H. (c) Carriers of missense variants except p.R181H. Mean age at first cancer onset shown by vertical line with corresponding color (46 years old; 32 years old; 31 years old).

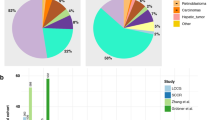

Mean age at first breast cancer onset was also higher in p.R181H carriers compared to carriers of other variants (44 years old vs 36 years old; p = 0.01, Table 1) and a significantly smaller proportion of breast cancers were diagnosed before the age of 40 (39% vs 72%; p = 0.01, Table 1). Furthermore, 81% of cancer patients with p.R181H developed exclusively breast cancers while the corresponding proportion for other variant carriers was 37% (p = 0.0002, Table 1). The narrow cancer spectrum is further illustrated in Fig. 3a where breast cancers constitute 86% of all first cancers and 100% of all first cancers in female carriers (Table S6).

First cancer classified according to core cancers in LFS and distribution of familial phenotypical classification in the Swedish cohort. (a) First cancer in each patient classified according to the cancers: adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), breast cancer, central nervous system (CNS) tumor, sarcoma and prostate cancer, all other cancers classified as “other”. Categorized by only p.R181H carriers (p.R181H), all carriers of other variants (non-p.R181H), missense variants except p.R181H (missense) and patients classified as hereditary breast cancer except p.R181H carriers (HBC). Corresponding proportions written as percentages in each bar. (b) Proportion of families classified as the phenotypical classes classic LFS, Chompret and HBC, all other families classified as “other”. Categorized by only p.R181H carriers (p.R181H), all carriers of other variants (non-p.R181H) and missense variants except p.R181H (missense). Corresponding proportions written as percentages in each bar.

All male p.R181H carriers with cancer developed prostate cancer (Fig. 3a), with a mean age at onset of 59 years. No prostate cancers were observed among carriers of other missense variants or in other HBC families. Thus, prostate cancer is enriched in p.R181H carriers compared to all other variants (Fig. 3a).

The most common phenotypical classification for families carrying p.R181H was HBC (78%) while the rest were classified as Chompret. No family was classified as classic LFS (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the HBC phenotype was the least common amongst carriers of other variants (21%, Fig. 3b). The proportion of p.R181H carriers in each phenotypical group is shown in Table S7.

Overall survival was significantly better amongst the p.R181H group (p = 0.0002, Fig. 4a), irrespective of cancer. At 75 years of age, 84% of the patients with p.R181H were still alive as compared to only 27% for other variant carriers (Fig. 4a). The difference in survival persisted even when comparing p.R181H carriers to only carriers of missense variants (p = 0.0007, Fig. 4b) but diminished when comparing against individuals with the HBC phenotype (p = 0.06, Fig. 4c).

Difference in overall survival stratified by p.R181H carrier status in the Swedish cohort. (a) All patients. (b) Only carriers of missense variants. (c) Only p.R181H carriers and patients with hereditary breast cancer phenotype (HBC). Green indicates carriers of the TP53 p.R181H germline variant and red indicates carriers of any other class 4 or 5 TP53 variant. P-values calculated using log-rank test.

Confirmation using NCI TP53 database

The clinical characteristics of the p.R181H carriers in the NCI TP53 database were similar to the 43 Swedish patients and differed from the carriers of other variants in the TP53 database (Table 3). Carriers of p.R181H had a later age at first cancer onset and only one individual developed a cancer (skin cancer, not LFS core cancer) before the age of 18 (Table 3 and Table S6). Cancer incidence was analyzed by pooling p.R181H carriers from the Swedish and NCI TP53 cohort and comparing against all other variant carriers in the NCI TP53 cohort, with significantly lower cancer risk amongst p.R181H carriers (p < 0.0001, Fig. 5a). Comparing the p.R181H carriers from the Swedish cohort with other variant carriers in the NCI TP53 cohort showed significantly better survival amongst p.R181H carriers (p < 0.0001, Fig. 5b). Both the cumulative cancer incidence and survival analysis (Fig. 5a,b) are in agreement with the findings based on the Swedish cohort.

Differences in phenotype between p.R181H and non-p.R181H carriers in the NCI TP53 database. (a) Cumulative cancer incidence comparing both Swedish and NCI TP53 database p.R181H carriers against all non-p.R181H carriers in the NCI TP53 database. (b) Overall survival comparing Swedish p.R181H carriers against all non-p.R181H carriers in the NCI TP53 database. No p.R181H carriers in the NCI TP53 database had survival data. Green indicates carriers of the TP53 p.R181H germline variant and red indicates carriers of any other class 4 or 5 TP53 variant. (c) Using only the NCI TP53 database; first cancer in each patient classified according to the cancers: adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), breast cancer, central nervous system (CNS) tumor, sarcoma and prostate cancer, all other cancers classified as “other”. Categorized by p.R181H carrier status. Corresponding proportions written as percentages in each bar. (d) Using only the NCI TP53 database; proportion of families classified as the phenotypical classes classic LFS, Chompret and HBC, all other families classified as “other”. Categorized by only p.R181H carriers (p.R181H), all carriers of other variants (non-p.R181H) and missense variants except p.R181H (missense). Corresponding proportions written as percentages in each bar. *HBC families are classified as “other” in the NCI TP53 database.

Classification of first cancer into core cancer group and phenotypical classification of families was performed exclusively using the NCI TP53 cohort and showed similar results as in the Swedish cohort. Carriers of p.R181H exhibited a later age of first cancer onset, with a high proportion presenting with breast cancer as their initial or sole diagnosis (Table 3, Fig. 5c). Phenotypical classification of families in the NCI TP53 cohort showed similar proportions as in the Swedish cohort with no p.R181H families being classified as classic LFS (Fig. 5d).

HER2 status in breast cancers

The proportion of HER2 positive breast cancers was lower amongst carriers of p.R181H compared to carriers of other variants (33% vs 52%, Table S8), although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.3).

Haplotyping

Haplotype analysis was used to evaluate the founder status of the variant and showed two haplotypes flanking a common core shared amongst all families consisting of TP53 and D17S1353 (Table S3); this could suggest a common genetic ancestor. The time to the most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) was calculated using a computational likelihood-based method (EstiAge) and estimated to be 550 years or 22 generations (95% CI [12, 40]), meaning that the original carrier lived in Sweden during the late 15th or early sixteenth century27.

Discussion

Through our extensive Swedish nationwide characterization of germline TP53 carriers we identified p.R181H as a unique variant; carriers exhibit a distinct phenotype characterized by lower cancer penetrance, higher proportion of breast and prostate cancers and improved survival compared to carriers of other TP53 variants.

To date, only three different TP53 founder variants have been suggested through haplotyping, these are p.R337H (Brazilian), p.G334R (Ashkenazi Jews) and p.R181C (Arabs). All these variants exhibit a wide cancer spectrum including several of the LFS core cancers, with presence of both childhood and adult-onset cancers16,17,31. As a result, implications for personalized clinical handling have unfortunately been limited with patients recommended similar surveillance regardless of variant starting from birth9.

The newest Swedish guidelines on LFS will recommend no testing or surveillance of pediatric carriers of p.R181H and only breast-MRI and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing for adult females and males, respectively32. This approach could reduce unnecessary follow-up of non-specific findings from WB-MRI. Approximately one-third of WB-MRI scans in TP53 carriers lead to false positives and benign follow-ups, often associated with psychological stress and, in some cases, harm from invasive diagnostics33,34,35,36. Variant-specific recommendations may reduce unnecessary hospital visits and invasive diagnostics, while improving cost-effectiveness by aligning surveillance with actual risk.

A recent literature review and case report suggested p.R181H could be associated with a breast cancer focused phenotype and lower penetrance37. However, all previous publications of the variant lack inferential statistics due to very limited sample sizes with the largest cohort published consisting of only ten individuals from four families. Furthermore, no survival data has been presented due to limited follow-up37,38. Therefore, there has been no specific guidance for personalized patient management.

By the age of 30 years, only 5% of p.R181H carriers had developed a cancer, which is significantly lower than the 15–20% penetrance observed in carriers of the Brazilian founder variant by the same age39. A recent Swedish prospective study sequencing all children with solid tumors from May 2021 to December 2022 found no germline carriers of the p.R181H variant, confirming its low tumor risk in pediatric carriers40. The incomplete penetrance of p.R181H was further supported by its presence in the non-cancer cohorts in gnomAD and FLOSSIES.

Furthermore, the variant has a relatively low pathogenicity score, as calculated by AlphaMissense, and shows partially functional transcriptional activity (between 20 and 75% of wild type) in functional studies in yeast41. A Danish study used a structure-based protein dynamics approach to investigate the effects of TP53 variants, including p.R181H. Their results reveal a structural alteration in p.R181H leading to decreased TP53 protein dimer formation, thereby affecting its DNA binding42. These structural changes caused by the variant should be further studied to elucidate the potential phenotypical associations.

The haplotype analysis identified two haplotypes with a shared core, excluding the possibility of a hot-spot variant. The small size of the shared core suggests either an ancient founder variant, as indicated by our age estimation software, or the presence of two independent founders. To clarify the variant’s origin, we are initiating collaborations with other European groups to analyze haplotypes in non-Swedish carriers.

In this paper, we present the largest and most comprehensive p.R181H cohort to date. We found its phenotype to be characterized by later-onset breast cancer in females, prostate cancer in males, and no childhood cancers, resulting in significantly improved survival. Our findings suggest that the clinical management of p.R181H carriers could potentially differ from that of carriers of high-risk variants. The data may guide future studies exploring whether management could be optimized by focusing predictive carrier testing and surveillance on adults, and by evaluating an approach that omits whole-body MRI in favor of breast-MRI for adult female carriers and PSA testing for adult male carriers. Thus, the genotype–phenotype correlations of p.R181H enable personalized clinical handling with potential implications for patient care and surveillance recommendations.

Data availability

Deidentified data from the Swedish germline TP53 database is available upon reasonable request by e-mail to the corresponding author. Novel variants have previously been submitted to ClinVar (submission number SUB14867261)43.

References

Frebourg, T. et al. Guidelines for the Li-Fraumeni and heritable TP53-related cancer syndromes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 28, 1379–1386 (2020).

Malkin, D. et al. Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science 250, 1233–1238 (1990).

Chompret, A. et al. P53 germline mutations in childhood cancers and cancer risk for carrier individuals. Br. J. Cancer 82, 1932–1937 (2000).

Evans, S. C. & Lozano, G. The Li-Fraumeni syndrome: an inherited susceptibility to cancer. Mol. Med. Today 3, 390–395 (1997).

Mai, P. L. et al. Risks of first and subsequent cancers among TP53 mutation carriers in the National Cancer Institute Li-Fraumeni syndrome cohort. Cancer 122, 3673–3681 (2016).

Kumamoto, T. et al. Medical guidelines for Li-Fraumeni syndrome 2019, version 1.1. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 2161–2178 (2021).

Kratz, C. P. et al. Cancer screening recommendations for individuals with Li-Fraumeni Syndrome. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, e38–e45 (2017).

Amadou, A., Achatz, M. I. W. & Hainaut, P. Revisiting tumor patterns and penetrance in germline TP53 mutation carriers: temporal phases of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 30, 23–29 (2018).

Giovino, C., Subasri, V., Telfer, F., et al. New paradigms in the clinical management of Li-Fraumeni Syndrome. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. (2024).

de Andrade, K. C. et al. The TP53 Database: Transition from the International Agency for Research on Cancer to the US National Cancer Institute. Cell Death Differ. 29, 1071–1073 (2022).

Ferla R, Calo V, Cascio S, et al. Founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Ann. Oncol. 18(Suppl 6), vi93–8, (2007).

Achatz MI, Zambetti GP. The inherited p53 mutation in the Brazilian population. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 6, 2016

Zeegers, M. P. et al. Founder mutations among the Dutch. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 12, 591–600 (2004).

Jain, A. et al. Founder variants and population genomes-Toward precision medicine. Adv. Genet. 107, 121–152 (2021).

Fischer, N. W., Ma, Y. V. & Gariepy, J. Emerging insights into ethnic-specific TP53 germline variants. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 115, 1145–1156 (2023).

Arnon J, Zick A, Maoz M, et al. Clinical and genetic characteristics of carriers of the TP53 c.541C>T, p.Arg181Cys pathogenic variant causing hereditary cancer in patients of Arab-Muslim descent. Fam. Cancer. 2024

Powers, J. et al. A rare TP53 mutation predominant in Ashkenazi Jews Confers risk of multiple cancers. Cancer Res. 80, 3732–3744 (2020).

Ribeiro, R. C. et al. An inherited p53 mutation that contributes in a tissue-specific manner to pediatric adrenal cortical carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9330–9335 (2001).

Paskulin DD, Giacomazzi J, Achatz MI, et al. Ancestry of the Brazilian TP53 c.1010G>A (p.Arg337His, R337H) founder mutation: Clues from haplotyping of short tandem repeats on chromosome 17p. PLoS One. 10, e0143262 (2015)

Frankenthal, I. A. et al. Cancer surveillance for patients with Li-Fraumeni Syndrome in Brazil: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 12, 100265 (2022).

Pinto EM, Zambetti GP: What 20 years of research has taught us about the TP53 p.R337H mutation. Cancer. 126, 4678–4686 (2020).

Paixao, D. et al. Whole-body magnetic resonance imaging of Li-Fraumeni syndrome patients: Observations from a two rounds screening of Brazilian patients. Cancer Imaging 18, 27 (2018).

Omran M, Liu Y, Sun Zhang A, et al. Characterisation of heritable TP53-related cancer syndrome in Sweden—A nationwide study of genotype-phenotype correlations in 90 families. Eur. J. Human Genet. (2025).

Landrum, M. J. et al. ClinVar: Public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D980–D985 (2014).

Magnusson, S. et al. Prevalence of germline TP53 mutations and history of Li-Fraumeni syndrome in families with childhood adrenocortical tumors, choroid plexus tumors, and rhabdomyosarcoma: A population-based survey. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 59, 846–853 (2012).

de Andrade, K. C. et al. Cancer incidence, patterns, and genotype-phenotype associations in individuals with pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline TP53 variants: An observational cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 22, 1787–1798 (2021).

Genin, E. et al. Estimating the age of rare disease mutations: The example of Triple-A syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 41, 445–449 (2004).

Cheng J, Novati G, Pan J, et al. Accurate proteome-wide missense variant effect prediction with AlphaMissense. Science. 381, eadg7492 (2023).

Tordai, H. et al. Analysis of AlphaMissense data in different protein groups and structural context. Sci. Data 11, 495 (2024).

Grahn, A. et al. Genomic profile—A possible diagnostic and prognostic marker in upper tract urothelial carcinoma. BJU Int. 130, 92–101 (2022).

Achatz, M. I. et al. The TP53 mutation, R337H, is associated with Li-Fraumeni and Li-Fraumeni-like syndromes in Brazilian families. Cancer Lett. 245, 96–102 (2007).

Riktlinjer för uppföljning av individer med en medfödd patogen variant i TP53-genen, National Working Group for Hereditary Cancer (2025).

Saya, S. et al. Baseline results from the UK SIGNIFY study: a whole-body MRI screening study in TP53 mutation carriers and matched controls. Fam. Cancer 16, 433–440 (2017).

Omran M, Tham E, Brandberg Y, et al. Whole-body MRI surveillance-baseline findings in the swedish multicentre hereditary TP53-related cancer syndrome study (SWEP53). Cancers (Basel). 14 (2022)

Alikhassi, A. et al. False-positive incidental lesions detected on contrast-enhanced breast MRI: Clinical and imaging features. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 198, 321–334 (2023).

Spiegel, T. N. et al. Psychological impact of recall on women with BRCA mutations undergoing MRI surveillance. Breast 20, 424–430 (2011).

Freycon C, Palma L, Budd C, et al: Germline p.R181H variant in TP53 in a family exemplifying the genotype-phenotype correlations in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Fam. Cancer. (2024).

Maxwell, K. N. et al. Inherited TP53 variants and risk of prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 81, 243–250 (2022).

Garritano, S. et al. Detailed haplotype analysis at the TP53 locus in p.R337H mutation carriers in the population of Southern Brazil: Evidence for a founder effect. Hum. Mutat. 31, 143–150 (2010).

Tesi, B. et al. Diagnostic yield and clinical impact of germline sequencing in children with CNS and extracranial solid tumors—A nationwide, prospective Swedish study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 39, 100881 (2024).

Kato, S. et al. Understanding the function-structure and function-mutation relationships of p53 tumor suppressor protein by high-resolution missense mutation analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 8424–8429 (2003).

Degn, K. et al. Cancer-related mutations with local or long-range effects on an allosteric loop of p53. J. Mol. Biol. 434, 167663 (2022).

Omran M, Liu Y, Sun Zhang A. et al. Characterisation of heritable TP53-related cancer syndrome in Sweden-a nationwide study of genotype-phenotype correlations in 90 families. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Swedish Clinical TP53 Study Group (SweClinTP53) for providing data to the Swedish germline TP53 database, Clinical Genomics at SciLifeLab for sequencing facility services, Mikaela Bodell-Davoody for haplotype analysis, and all participants in the SWEP53 study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. Radiumhemmet (201052), Cancerfonden (22 2451 Fk), Barncancerfonden (TJ2022-0011, TJ2021-0125) and Region Stockholm (FoUI-973659).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ASZ: conceptualization, project design and planning, data collection, statistical analysis, data analysis and writing of the original draft. MO: conceptualization, data collection and revision of the manuscript. CA: collection of samples and data analysis. HM: data collection and data analysis. RB-M, SS and CO: age estimation. ET: conceptualization, project design and planning, funding acquisition, data analysis and revision of the manuscript. SB-L: conceptualization, project design and planning, funding acquisition and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun Zhang, A., Omran, M., Arthur, C. et al. TP53 p.R181H is enriched in the Swedish cohort (SWEP53) and associated with a distinct breast and prostate phenotype. Sci Rep 15, 35033 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22407-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22407-2