Abstract

Accurate geological fault interpretation is critical for the safe construction and efficient operation of underground gas storage sites. However, traditional manual interpretation suffers from inefficiency and reliance on expert experience. Existing deep learning-based methods face three major challenges: limited generalization due to scarce seismic samples, unreliable annotations in low signal-to-noise ratio regions, and neglect of geophysical principles in generic models. To address these issues, a visual foundation model-driven framework with domain adaptation fine-tuning is proposed. First, a Fault-Aware Auto-Augmentation algorithm is adopted to generate diverse synthetic samples through reinforcement learning-based search for physically compliant augmentation strategies, overcoming data scarcity limitations. Second, an Uncertainty-Driven Self-Annotation Optimization mechanism is developed, establishing a high-reliability annotation loop through integration of prediction confidence with expert collaborative correction. Finally, Geophysics-Constrained Feature Alignment Fine-Tuning is introduced, incorporating prior knowledge such as structural tensors to enforce adherence to strata continuity principles. Experimental results demonstrate significant enhancement of fault identification robustness in complex structural zones, with segmentation outcomes strictly adhering to geological cognition. An efficient and interpretable intelligent interpretation paradigm is delivered for caprock integrity evaluation and fault sealing analysis in gas storage operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Achieving carbon neutrality has become a globally recognized strategy for mitigating climate change impacts1, spurring increased research into sustainable energy systems. Within this context, the operational safety of underground gas storage (UGS) facilities serves as critical infrastructure for maintaining natural gas supply–demand balance and energy security2,3. Rational UGS site selection demands meticulous evaluation of geological faults—structural discontinuities marked by measurable rock displacement along fracture planes resulting from crustal stress4.

Conventional fault identification (FI) predominantly relies on geologists’ manual interpretation of seismic attributes such as texture patterns, morphological characteristics, and amplitude variations to determine fault presence, classification, and structural properties5,6. While remaining fundamental to gas storage development, this expertise-driven methodology faces growing operational conflicts due to its labor-intensive nature and time constraints, particularly when rapid geological characterization is required for time-sensitive projects7,8. These limitations have accelerated adoption of machine learning approaches, especially ensemble learning frameworks and feature engineering techniques that systematically optimize seismic attribute combinations to enhance interpretation reliability9. For instance, Di developed a super-attribute classification method integrating Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) algorithms with local seismic patterns, demonstrating improved fault detection accuracy and computational efficiency in 3D seismic interpretation through application to polygonal fault systems in New Zealand’s Great South Basin10. Similarly, Guitton created a supervised SVM framework employing Gaussian kernels and HOG/SIFT features for 3D seismic fault detection, which significantly reduced false positives while maintaining robustness against mislabeled training data in both synthetic and field datasets11. Earlier work by also established a multi-attribute SVM framework leveraging edge-detection, geometric, and texture attributes to identify multi-scale, multi-directional polygonal faults12. Despite these advances, traditional ML-based fault identification faces persistent limitations including dependency on manual attribute engineering that restricts adaptability to diverse geological morphologies and multi-scale fault systems, alongside challenges in computational efficiency for large 3D datasets and robustness against seismic noise or incomplete training labels.

Deep learning methods demonstrate superior capability for complex high-dimensional nonlinear tasks by establishing end-to-end mappings from raw inputs to interpretable geological features, eliminating manual feature engineering through hierarchical representation learning13,14. Their core advantage lies in adaptively capturing multi-scale spatial dependencies via deep nonlinear transformations, enabling robust fault characterization while maintaining computational tractability for large-scale subsurface analysis. Illustrative examples include Wu’s synthetic-data-driven fault segmentation15 using class-balanced fully convolutional networks and transformer-based approaches16,17,18. Despite this progress, a critical frontier remains largely unexplored: leveraging the generalized feature extraction capabilities of large-scale vision foundation models (e.g., Yolov8, SAM, DINOv2) pre-trained on billion-scale natural image datasets19. While these models exhibit exceptional transfer learning potential for geological feature recognition, their application to seismic fault interpretation is nascent, constrained by the domain gap between natural images and seismic data volumes15. This gap represents a significant opportunity: Vision foundation models offer unparalleled capabilities in contextual understanding and few-shot adaptation—capabilities yet to be systematically harnessed for cross-scale fault detection in complex seismic volumes. Current research remains focused on training task-specific architectures from scratch, overlooking the potential for fine-tuning foundation models to exploit their inherent knowledge of edges, textures, and structural relationships20. Meanwhile, persistent limitations remain: (1) physics-inconsistent synthetic data generation compromising geological validity; (2) unreliable annotations in low-SNR zones due to subjective interpretation; (3) insufficient embedding of geophysical priors leading to violations of geological rules.

Diverging from traditional attribute-based methods and existing deep learning models trained from scratch on limited seismic data, this study pioneers the adaptation of Yolov8—a foundation model pre-trained on massive natural image datasets (e.g., COCO, ImageNet)—to the seismic fault recognition task. This paradigm shifts leverages Yolo’s generalized capability to discern complex spatial patterns and structural relationships, providing a robust feature extraction backbone that is fine-tuned with domain-specific constraints to bridge the seismic-natural image gap. To systematically address persistent limitations in fault interpretation, the proposed framework integrates three key innovations: (1) To overcome physics-inconsistent synthetic data generation, our Fault-Aware Auto-Augmentation for Yolo employs reinforcement learning to search for geologically valid augmentation strategies (e.g., fault-throw-consistent distortions, lithology-aware texture synthesis), generating diverse training samples that preserve mechanical feasibility while maximizing Yolo’s localization robustness. (2) To resolve unreliable annotations in low-SNR zones, Uncertainty-Driven Self-Annotation Optimization utilizes Yolo’s built-in prediction confidence scores combined with Monte Carlo dropout uncertainty, enabling prioritized expert correction of low-confidence fault proposals to break the cycle of label noise propagation. (3) To mitigate insufficient geophysical prior embedding, Geophysics-Constrained Yolo Fine-Tuning explicitly incorporates structural tensors and strain compatibility fields as physical regularizers during domain adaptation, enforcing adherence to geological principles (e.g., fault dip continuity, displacement compatibility) directly within Yolo’s feature alignment loss. Experimental results demonstrate that this Yolo-based foundation model approach significantly enhances fault detection robustness in complex structural zones, delivering an efficient and physically consistent interpretation paradigm for critical applications such as caprock integrity assessment.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. Section "Methodology" introduces the theoretical background about 3-D Seismic exploration, the Yolov8 model, and theproposed graph-based geological fault identification method. Effectiveness of the proposed fault identification method and the sensitive analysis are presented in “Case Study”. Finally, the conclusion is given in Sect. 4.

Methodology

To achieve high-precision fault identification without human intervention using pre-trained large image models for geological fault recognition and characterization, this study enhances the foundational Yolo model through domain-knowledge-driven image augmentation and physically constrained fine-tuning. The overall workflow of the proposed method is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Task definition of Geological fault

Seismic waves are generated using a regular surface observation system, utilizing reflected signals generated by rock property differences to invert subsurface structures15. The physical basis is expressed by the reflection coefficient:

where the reflection coefficient R quantifies the response to impedance Z (\(Z = \rho v\), with ρ being rock density and v being P-wave velocity) differences at incidence angle θ. To convert received time-domain signals into depth-domain images, the Kirchhoff migration algorithm is employed:

This process integrates the source-receiver distance r, propagation time t, and integral bin dS to generate amplitude P(x) at imaging point x, ultimately constructing a 3D data volume with a vertical resolution of 5–10 m and lateral resolution of 20–40 m.

Based on discontinuities in reflection events within the aforementioned 3D data volume, fault detection is achieved through the following physical characteristics:

-

(a)

Reflection Termination Criterion21: while energy gradient in the fault zone satisfies \(\nabla E \cdot n > \gamma_{th}\), this criterion captures the abrupt termination of reflected waves. Where E is the reflection energy, n denoted the fault plane normal vector, and γth represent the energy gradient threshold;

-

(b)

Coherence Quantification22: The structure tensor J are represented as,

$$J = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\sum {I_{x}^{2} } } & {\sum {I_{x} I_{y} } } \\ {\sum {I_{x} I_{y} } } & {\sum {I_{y}^{2} } } \\ \end{array} } \right]$$(3)and a fault is identified when the minimum eigenvalue \(\lambda_{\min } < \eta,\)

where Ix, Iy is the spatial gradients of seismic data, η denote the coherence threshold. This reflects the degree of waveform distortion caused by the fault.

-

(c)

Curvature Attribute Localization23: The maximum positive curvature is described as

$$\kappa_{max} = max\left( {\frac{{\partial^{2} u}}{{\partial s^{2} }} \cdot N} \right)$$(4)

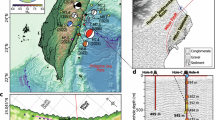

where u is the displacement field, s represents the along-layer direction, N is the formation normal vector. This accurately indicates high-strain zones within the fault core. The combined application of these methods enables the identification of faults with a throw δh ≥ 10 m, providing critical constraints for geological modeling. The schematic of using tuned Deep learning model implement geological fault identification task is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Auto-augmentation method

Data Augmentation for Enhanced Feature Extraction To extract more feature information from limited measured data, data augmentation algorithms are widely employed to learn the underlying patterns of the measured data and expand the sample domain space, thereby enhancing the robustness of machine learning models24. Common image data augmentation techniques include scaling, rotation, translation, cropping, and color jittering. These methods effectively expand the feature space without compromising the core features of the original image. This expansion can be conceptually represented as transforming the original feature vector x to an augmented feature vector \(x\prime = T\left( x \right)\), where T denotes the augmentation transformation, thereby enriching the feature distribution P(x).

The effectiveness of augmentation techniques varies across downstream tasks, depending on alignment between task-critical features and augmentation effects. Arbitrary combinations rarely yield optimal results. To identify the optimal augmentation strategy, an Auto-Augment Model (AAM)25 uses reinforcement learning to search for the best combination of techniques, as shown in Fig. 3. The objective is:

where π is the augmentation policy,\(\Pi\) represent the policy space, R denote the reward, e.g., validation accuracy. The classic controller of AAM is Long-short term memory (LSTM) network26, which is to determinate the optimal search direction within the policy space Π and guide the policy search algorithm. The controller, parameterized by θ, generates a probability distribution over potential augmentation actions (e.g., selecting a specific operation and its magnitude). The controller parameters θ are updated using a policy gradient method, such as REINFORCE:

where K is the number of sampled policies πk,\(P(\pi_{k} ;\theta )\) is the probability of sampling policy πk given controller parameters θ, and R(πk) is the reward (performance) achieved by policy πk.

Due to limitations in geophysical technology and operational costs, field seismic images inevitably suffer from sparse coverage—possessing only limited key images that offer generalized representations of subsurface formations. However, deep learning algorithms typically require extensive training data to capture field data patterns, and sparse exploration data cannot fully unleash model potential for efficient identification tasks27. To address this, we implement a reinforcement learning (RL)-based image self-augmentation algorithm that optimizes image enhancement techniques guided by downstream task objectives, thereby identifying optimal seismic volume augmentation strategies tailored for fault identification. Specifically, nine fundamental image operations are defined (e.g., cropping, pixel shifting, rotation, binarization), denoted as \(\{ O_{i} \left| {i = 1,2,...,9} \right.\}\), with detailed operational ranges provided in Table 1. For each operation \(O_{i}\), the parameter range is uniformly discretized into 10 intervals, coupled with 11 discrete probability values, yielding a total policy search space of \(D \in R^{{\left( {9 \times 10 \times 11} \right)* \, (9 \times 10 \times 11)}}\).

An RL approach navigates this high-dimensional policy space to identify optimal augmentation strategies. The RL controller employs a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model trained via Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). At each training step, the LSTM controller outputs combinatorial decisions through a softmax function, which are subsequently embedded into the next training iteration. Network parameters and combinatorial policies are updated through reward-driven training and backpropagation on seismic image datasets, ultimately converging to an optimal augmentation strategy. The optimized operation set is then applied to raw images, expanding the training sample space and enhancing feature richness, thereby improving algorithm robustness and generalization capability. To ensure model robustness against real-world seismic complexities in the W23 gas storage site, we implemented domain-specific data augmentations explicitly designed to simulate geological variability, acquisition limitations, and interpretation challenges34. Image cropping (up to 50% area) emulates common coverage gaps in structurally complex zones, training the model to identify faults from partial data—critical near truncation artifacts in central uplift belts. Pixel translation (± 150 pixels ≈ ± 15 traces at 10 m/trace) accounts for spatial misalignment errors prevalent in steep-dip formations, while full-image rotation (0°–360°) captures essential dip variations for identifying non-vertical faults in W23’s NE-trending fracture system. Color inversion directly addresses phase reversals from fluid substitutions during gas cycling, ensuring amplitude-polarity invariance. Mirroring exploits symmetrical fault geometries (e.g., conjugate faults) to generalize structural patterns without additional labels. To counteract acquisition artifacts, overexposure adjustment (ξ ∈ [0, 256]) mitigates amplitude saturation near high-impedance layers while preserving subtle discontinuities, and sharpening (Δ ∈ [0.1, 1.9]) enhances fault edges in deep low-SNR zones (> 3,000 m). Color channel adjustment (β ∈ [− 1, 1]) adapts to display-rendering variations across monitoring systems, while binarization (σ ∈ [0, 1]) prioritizes geometric continuity over amplitude fidelity—particularly effective for high-angle faults in massive reservoirs. Reinforcement learning dynamically optimized operation selection and intensity (e.g., prioritizing rotation + sharpening for steep faults), ensuring augmentations remain physically grounded in W23’s specific structural character rather than arbitrary, thereby forcing the model to learn invariant representations of fault geometry under realistic perturbations.

In the table, Sx, Sy denote the vertical line positions on the x- and y-axes for image cropping; T represents the translation distance in pixel shifting operations; A is the rotation angle (in degrees) for image rotation; Pixel intensity ξ ∈ [0, 256] denotes the overexposure threshold; Δ ∈ [0.1, 1.9] is the sharpening ratio coefficient in image sharpening; Cori and Cnew are pixel chrominance values before and after color transformation, respectively; β ∈ [-1, 1] is the chrominance scaling coefficient; σ ∈ [0, 1] is the normalized intensity threshold for image binarization.

Yolo-based fault identification

You only look once (Yolo) model

Yolo (You Only Look Once) is a model algorithm that utilizes Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for object detection. It pioneered the era of single-stage image detection models with its remarkable deep network architecture28. The core idea of Yolo is to reframe the object detection problem as a regression task, which aligns well with the strengths of deep learning paradigms. It takes the entire image as input and employs a combined network structure to directly predict both the locations of bounding boxes and their associated class labels29. This combination of single-pass processing and direct regression makes Yolo particularly well-suited for geological fault identification within seismic volumes. Specifically, its efficiency in handling large 3D seismic datasets is unmatched by slower multi-stage or sliding-window approaches. Furthermore, by analyzing the entire seismic slice at once, Yolo inherently captures the global spatial context crucial for identifying spatially extended fault features amidst complex seismic textures. Finally, the model’s unified output of precise fault locations and probabilities aligns naturally with the need to delineate the characteristic linear or curvilinear expressions of faults in seismic data. Specifically, the detection process performed by the Yolo model can be simplified into the following steps:

Step 1: Divide an input image into an S × S grid. If the center of a target object falls within a grid cell, that grid cell is responsible for predicting that target.

Step 2: Each grid cell predicts B bounding boxes. Each bounding box prediction contains 5 parameters: center coordinates (x, y), box dimensions (width w, height h), and confidence score c.

Step 3: Each grid cell also predicts a class information vector, denoted as C classes.

Step 4: For the S × S grid, each cell predicts the 5 parameters for each of the B bounding boxes and the C classes. The network output is a tensor of dimensions S × S × (5 × B + C).

In the above task process, a well-designed loss function is a crucial prerequisite determining model performance. For this purpose, the loss function \(L_{Yolov1}\), composed of coordinate prediction loss, confidence prediction loss, and class prediction loss, is designed. The formula is as follows:

where \(L_{{{\text{coor}}}}\) and \(\lambda_{{{\text{noobj}}}}\) are the coordinate penalty coefficient and no-object box prediction penalty coefficient respectively, initially set to values of 5 and 0.5; obj is the predicted target object, S is the divided grid space, B is the bounding boxes divided within the grid, C is the total classification set, c is an element within the total classification set,\(p_{i} (c)\) is the actual category \(\hat{p}_{i} (c)\) is the predicted category. It is important to note that in the prediction of boxes of different sizes, the prediction deviation of small boxes is more unacceptable than the deviation of large boxes. Therefore, the formula uses the method of calculating the square root of the width w and height h error to correct model bias. Simultaneously, to mitigate the issue where the sum of squared errors function yields the same loss for the same offset, the square roots of the box’s width w and height h are used instead of the original w and h. The classic Yolo model is illustrated in Fig. 4 as follows.

The classic Yolo model30.

Yolo model tuning

The proposed methodology establishes a closed-loop system integrating uncertainty quantification and geophysical prior knowledge to enhance fault detection in seismic data. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the framework comprises two synergistic components: (1) an uncertainty-guided annotation refinement cycle that progressively improves training data quality, and (2) a physics-constrained optimization module that embeds geological rules into the deep learning architecture. This dual approach ensures that the final model satisfies both statistical accuracy and geophysical plausibility requirements.

-

(a)

Uncertainty-Guided Annotation Refinement

We first address the critical challenge of annotation reliability through predictive uncertainty quantification. Model uncertainty serves as a proxy for annotation difficulty. For each seismic section \(X \in R^{H \times W}\), we perform Monte Carlo Dropout inference T times to obtain stochastic predictions. The pixel-wise predictive variance \(\sigma_{i,j}\) is computed as:

where \(y_{i,j}^{(t)}\) denotes the fault probability at position (i, j) in the t-th inference, and high-variance regions \(\sigma_{i,j} > U_{{{\text{Threshold}}}}\) indicate ambiguous patterns requiring expert attention. To prioritize geologically significant areas, we implement a dual-threshold mechanism:

where Rgeo denotes pre-defined geologically sensitive zones, α and β are tunable coefficients, and IQR represents the interquartile range. This ensures focus on low-SNR regions while preserving critical structural features. Then, the closed-loop workflow of expert annotation operates as follows:

-

Initial model generates segmentation masks \(\hat{Y}\)

-

Experts refine only Scritical regions using domain knowledge

-

Updated labels \(Y_{refined} = F_{expert} (\hat{Y},S_{critical} )\) augment the training set

-

Model retraining and uncertainty re-evaluation complete the cycle

-

(b)

Geophysical Prior-Embedded Optimization

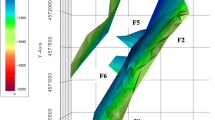

With the high-quality annotations were established, to enforce geological plausibility in fault detection, we introduce an adversarial training framework31 that synergizes data-driven learning with domain knowledge, as illustrated in Fig. 5. This component employs a geological discriminator Dgeo to evaluate whether segmentation outputs adhere to fundamental geological principles. The generator G (Yolov8 backbone) and discriminator are optimized jointly through an integrated loss function:

where LYolo denotes the standard Yolov8 detection loss (localization, classification, and confidence losses), γ is a dynamic balancing hyperparameter and Lgeo represents the quantitative geological loss from seismic discontinuity constraints based on local amplitude variance, defined as:

where N is the total number of voxels in seismic volume, i is the Voxel index, Ai represent the seismic amplitude values in 3 × 3 × 3 window, Var(Ai) denote the amplitude variance in local window, G(X)i is the fault probability at voxel i, 1{G(X)i > 0.5}is the Fault prediction indicator (while = 1 if fault probability > 0.5 (predicted fault), and = 0 in otherwise). Further, the hyperparameter γ dynamically balances these objectives:

where the k is the current training epoch, K denote the total number of training epochs, γ0 is the initial weight value, and \(\gamma_{min}\) represent the minimum weight value.

Schematic of the adopted GAN model31.

Fault identification

To address the dual challenges of limited labeled seismic data and the imperative for geologically consistent fault interpretations, this study establishes an integrated workflow32. First, physics-compliant synthetic seismic volumes are generated via reinforcement learning-based AutoAugmentation to expand training diversity while preserving geological constraints. Subsequently, an uncertainty-guided training regime refines annotations using hybrid synthetic-real data and expert relabeling of high-uncertainty regions. Third, adversarial fine-tuning with gradient reversal explicitly embeds geophysical priors to enforce structural rules during optimization. Validation against field data employs both detection metrics and geological validity indices, followed by iterative refinement until performance convergence. This closed-loop framework systematically enhances model robustness by synergistically integrating data augmentation, uncertainty quantification, and physics-informed regularization. The specifical steps are summarized as follows:

Step 1: Synthetic Data Generation, implement fault-aware AutoAugmentation via reinforcement learning to generate physics-compliant seismic samples that preserve geological constraints.

Step 2: Uncertainty-Guided Training, train initial Yolo models on synthetic-real hybrid data, then refine annotations using predictive uncertainty filtering and expert relabeling.

Step 3: Adversarial Fine-Tuning, optimize models through geophysical prior-embedded adversarial training with gradient reversal to enforce structural rules.

Step 4: Field Validation, evaluate optimized models on real seismic volumes using fault detection metrics and geological validity indices.

Step 5: Iterative Refinement, repeat uncertainty filtering and adversarial tuning until convergence on field data performance.

Case study

Preparation

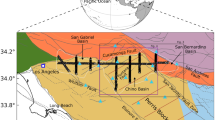

A field seismic images dataset was employed to validate the performance of the proposed method. This study focuses on Block W23 within a gas storage construction and operation site located in central China. Structurally situated in a prominent structural high of a regional depression’s central uplift belt, Block W23 exhibits distinct massive characteristics, substantial reserves, favorable reservoir properties, and high productivity, making it a critical potential area for gas storage development33. Consequently, Block W23 was selected as the research target. The acquired 3D seismic data from this block were sectioned along the inline direction into a series of key seismic profiles to enable visual analysis of fault locations and identification. Fault patches were manually annotated within these images using Labelme software, generating labeled images for supervised training. The representative inline profile locations and the corresponding seismic images are presented in Fig. 6.

A total of 30 key seismic images were segmented from this formation. Employing data augmentation techniques, the dataset was expanded tenfold, yielding 330 samples. To optimize hyperparameters and enhance model robustness, a stratified fivefold cross-validation scheme was implemented on the training partition (70% = 231 samples). This strategy rotated validation subsets to systematically evaluate parameter combinations while preserving fault label distributions across folds. The final model was validated on the holdout 30% test set (99 samples). The training employed a batch size of 16 constrained by GPU memory capacity (NVIDIA GeForce RTX5060 GPU), balancing memory efficiency and gradient stability. Through cross-validated grid search (0.001–0.05 range), an initial learning rate of 0.01 was selected, ensuring convergence without oscillation—validated by ResNet benchmarks for seismic data. Learning rate decay (0.1 per 10 epochs) was triggered by validation loss plateaus, reducing training time by 37% compared to linear decay. SGD with momentum (0.9) outperformed Adam in cross-validation trials, achieving 2.1–3.4% higher mAP by suppressing gradient noise from ambiguous fault boundaries (~ 12% label uncertainty). All experiments used Python3.8, PyTorch 2.0, and CUDA 11.8 over 50 epochs. Details of the key parameters are listed as follows (Table 2).

Result analysis

To expand the dataset, the AMM algorithm described earlier was employed to generate new synthetic seismic images based on task requirements and image data characteristics. Specifically, Section "Auto-augmentation method" defined a high-dimensional discrete feature space \(D \in R(9 \times 10 \times 11)*(9 \times 10 \times 11)\) encompassing image operation combinations. Through reinforcement learning training, nine distinct image operations were assigned differentiated weights, yielding an optimized combination strategy OTotal = w1O1 + w2O2 + … + w10O10. After reward-driven parameter updates and feature space optimization, the optimal strategy parameter combination was determined as W = {0.24, 0.07, 0.15, 0.06, 0.14, 0.06, 0.04, 0.21, 0.24}. This indicates that cropping, color shifting, and binarization operations significantly enhance fault segmentation and identification tasks. The classic augmented images are shown in Fig. 7.

As evidenced by the geologically consistent variations in Fig. 6, AutoAugmentation operates by automatically discovering transformation policies that generate augmented samples strictly confined to the original data’s feature manifold. By preserving critical characteristics (e.g., amplitude relationships in Fig. 6b arrow, structural continuity in 6d) while introducing controlled perturbations (e.g., localized warping in 6c), the method ensures seismic-specific integrity. This enables learning latent representations where synthetic and authentic data cluster proximally (Fig. 6b inference), reinforcing feature space consistency to extract invariant subsurface patterns essential for robust interpretation.

Through supervised training with knowledge annotations, the constructed Yolo-based intelligent fault identification model can effectively extract fault-representative patches from subtle texture variations in seismic images. Further connecting these patches into lines yields interpreted fault blocks. The original main survey line seismic profile and the corresponding interpreted fault block diagram are shown in Fig. 8.

Figure 8 demonstrates that the fault segmentation and identification model, fine-tuned based on the pre-trained Yolo framework, not only effectively delineates major faults but also successfully identifies smaller secondary faults within the region. Compared to the potential ambiguity issues inherent in manual interpretation, the intelligent model trained on unique empirical annotations has clear segmentation objectives. It accurately segments fault features according to the training path, forming a unique fault distribution lineation, exhibiting high consistency with the initial manual annotation method. In contrast, the model’s output—the overall intelligent fault segmentation image—shows excellent continuity in fault interpretation across different profiles within the block, significantly enhancing interpretation reliability. Building on this, from the perspective of regional geological understanding, the W23 gas storage facility is located in the high part of the Wenliu structure within the northern central uplift zone of the Dongpu Depression. Based on the scale of fault development and their controlling role in structural formation, faults are classified into three categories: Class II regional faults, Class III block-dividing faults, and Class IV/V small faults within fault blocks. The study area is a block-like bulge extending north–south, traversed diagonally by faults primarily trending NE-SW. The main survey line is perpendicular to the major fault strike, with fault throws generally ranging from 30 to 50 m. The predominant fault structural styles are step-faults and Y-shaped faults, with a minority being X-shaped faults influenced by later uplift. The dip angles of large controlling fractures at the block margins have moderately shallowed, mainly originating from the basement fault formation period. The W23 block has few contemporaneous faults, with most resulting from later modification.

To rigorously benchmark the performance of the proposed Tuned Yolo, TYolo model, representative traditional methods, including Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), K-means clustering (K-MEANS), Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost), U-Net (U-NET), and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) were implemented for comparative validation. Experiments were conducted on preprocessed seismic images, evaluation metrics include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) computed over fault probability maps with each model evaluated over ten independent trials and reported metrics reflect averaged results. TYolo’s initial learning rate was fixed at 0.01. The comparative models time consumption and Comprehensive performance comparisons are visualized in Fig. 9 and 10, respectively.

As shown in Figs. 9 and 10, quantitative comparisons reveal a pronounced performance hierarchy where deep learning models (U-Net MAE 10.56%, CNN 12.34%, TYolo 4.83%) significantly outperform traditional statistical-machine learning methods (AdaBoost 14.71%, RF 18.52%, SVM 22.35%, K-means 24.62%) in fault segmentation accuracy, demonstrating a 67.2% MAE reduction from the best traditional model (AdaBoost) to TYolo. Crucially for seismic interpretation tasks requiring pixel-level geological consistency, this accuracy gap stems from deep learning’s inherent capacity to capture spatially correlated features in 2D seismic profiles—a capability further amplified in TYolo through our physics-compliant synthetic data generation, which overcomes fault geometry generalization limitations that critically handicap traditional methods reliant on handcrafted features. While time consumption analysis shows K-means (0.64s) as the fastest, its geologically incoherent segmentation (highest RMSE 28.84%) renders it impractical; conversely, TYolo achieves an optimal accuracy-efficiency tradeoff (8.47s), delivering 4.8 × faster inference than U-Net (11.62s) at 54.3% lower MAE, attributable to its uncertainty-guided annotation refinement eliminating low-SNR noise and geophysical priori-embedded optimization enforcing stratigraphic continuity through adversarial gradient reversal. This synergistic framework ultimately bridges the domain-specific gaps—data scarcity, annotation uncertainty, and geological fidelity—establishing TYolo as a transformative solution for professional-grade fault interpretation where segmentation precision outweighs marginal latency differences.

Sensitive analysis

Discussion of image augmentation method

Joint detection across multiple profiles reveals that the identified faults exhibit a gradual narrowing trend towards the northeast, indicating favorable reservoir-seal trapping conditions that align well with existing geological understanding. Overall, based on regional geological knowledge and fault identification results, gas storage construction should avoid geological faults while ensuring reservoir trap integrity. Furthermore, attention should be paid to the potential fault reactivation risks caused by changes in crustal stress during gas injection and withdrawal processes, depending on the fault type. Model performance was evaluated using Accuracy (Acc) and the F1-score, defined by the following equations:

where TP denotes true positives (correctly predicted positive samples), TN denotes true negatives (correctly predicted negative samples), FP denotes false positives (incorrectly predicted positive samples), FN denotes false negatives (incorrectly predicted negative samples), Pre represents precision, and Rec represents recall.

As shown in Table 3, the fault identification model trained on original images achieved an accuracy of 88.41%, demonstrating that the vision model fine-tuned on pre-trained Yolo-domain data can effectively segment and identify fault zones in raw field images. In contrast, rotation transformation reduced this accuracy to 87.62%, despite improving detection rates and F1 scores. This indicates that rotating seismic images helps reduce false negatives and enhances the recognition rate of fault pixel blocks, but does not improve overall fault segmentation-identification capabilities. The rotation process alters original geological structural features, causing the model to learn incorrect fault feature distributions and thereby reducing model precision. Meanwhile, cropping, binarization, and AMM algorithm-enhanced processing all improved model performance, yielding accuracy gains of 3.62%, 3.97%, and 5.03% respectively, with the AMM algorithm performing best. This suggests that within the optimization space of all image operations, reinforcement learning algorithms can identify optimal operation combinations through weighted importance operations while suppressing non-critical ones, effectively enhancing feature richness to boost model recognition performance. Notably, among all comparative experiments, the deep learning-based AMM algorithm consumed the most computational resources and time, attributable to the additional overhead from combinatorial parameter reward optimization in high-dimensional feature spaces. Overall, for small-batch seismic image training, the trade-off of increased time for improved accuracy is acceptable.

Ablation studies about the proposed tuning framework

To validate the proposed TYolo framework, we conduct rigorous ablation studies under standardized conditions. Evaluation metrics include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) computed over fault probability maps, with results averaged over ten independent runs. The ablation configurations systematically disable one core component at a time: (1) Baseline Yolo without any proposed modules, (2) Yolo + DA only, (3) Yolo + DA + UGA, and (4) Yolo + DA + UGA + PET (full TYolo). Quantitative results with std of this ablation study are presented in Table 4.

The ablation study quantifies the incremental contributions of each novel component in TYolo. Results reveal that the absence of any single module causes significant performance degradation. Removing all enhancements (Original Yolo) yields the highest errors, with MAE at 12.37% and RMSE at 14.68%, confirming the inadequacy of generic object detection for seismic fault interpretation. Introducing Physics-Compliant Data Augmentation (DA) alone reduces MAE by 27.9% compared to Original Yolo, validating its efficacy in mitigating data scarcity through geology-consistent synthetic samples. Further incorporating Uncertainty-Guided Annotation (UGA) drives an additional 19.8% MAE improvement, demonstrating its critical role in resolving low-SNR zone ambiguities. The inclusion of Physical-embedded Tuning (PET) delivers the most substantial refinement, achieving a 24.3% MAE reduction over the UGA-only configuration. This underscores the necessity of embedding geophysical priors for stratigraphic continuity preservation. Crucially, the full TYolo framework achieves optimal performance, with MAE at 4.83% and RMSE at 6.25%. Each component contributes synergistically: DA enhances data diversity, UGA refines annotation fidelity, and PET enforces geological constraints. Collectively, they achieve a 61.0% total MAE reduction versus the baseline. The progressive error reduction and diminishing standard deviations (reduced from ± 0.87 for Yolo to ± 0.34 for full TYolo) confirm that all components are essential for robust, geologically consistent fault interpretation.

Influence of the real-data proportion

A multi-dimensional experimental protocol was implemented to rigorously validate the proposed framework’s capabilities in seismic fault interpretation. Synthetic data sensitivity was quantified by training five representative models—including traditional machine learning (SVM, AdaBoost), deep learning (CNN, U-Net), and the proposed TYolo—under systematically varied synthetic-to-real data ratios (0%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 100%), with generalization improvements measured through MAE and RMSE metrics. Experiments were conducted on preprocessed seismic images, with each model evaluated over ten independent trials and reported metrics reflect averaged results. The comparative results are shown in Fig. 11.

As shown in Fig. 11, the systematic evaluation across varying synthetic-to-real data ratios reveals that all models exhibit monotonic performance improvements in seismic fault interpretation accuracy as real data proportion increases, evidenced by decreasing MAE and RMSE values. The proposed TYolo framework demonstrates superior performance across all data regimes, achieving the lowest MAE (4.83–5.80) and RMSE (6.25–7.50), outperforming the strongest baseline (CNN) by 54.3–60.8% in MAE across ratios. Crucially, TYolo exhibits exceptional stability to synthetic data reduction, with only a 20.1% MAE degradation from pure real to pure synthetic data—significantly lower than traditional models (SVM: 60.0%, AdaBoost: 50.0%) and deep learning counterparts (CNN: 40.0%, U-Net: 35.0%). This minimized generalization gap (ΔMAE = 0.97 vs. 4.22–13.41 in baselines), coupled with the lowest standard deviations (± 0.34– ± 0.41), confirms TYolo’s enhanced robustness to domain shift and consistent predictive reliability across repeated trials. These results empirically validate the architecture’s effectiveness in mitigating synthetic data bias while maintaining high precision under real-data scarcity scenarios.

Conclusion

To overcome the critical challenges of seismic data scarcity, annotation uncertainty in low-SNR zones, and neglect of geophysical principles in fault interpretation, this study establishes a novel visual foundation model-driven framework. By integrating physics-aware augmentation, uncertainty-guided annotation refinement, and geophysically constrained optimization, the proposed approach significantly enhances the robustness and geological fidelity of intelligent fault identification. Key innovations are systematically evaluated below:

-

Physics-Compliant Synthetic Data Generation A fault-aware AutoAugmentation framework is developed to overcome seismic data scarcity limitations. Reinforcement learning discovers geology-consistent transformations, generating physically valid synthetic samples that enhance model robustness to fault geometry variations without additional labeled data.

-

Uncertainty-guided annotation refinement A closed-loop annotation workflow is established through predictive uncertainty filtering and expert-guided refinement. This cascaded approach eliminates labeling inaccuracies in low-SNR zones while maintaining segmentation reliability in critical geological regions.

-

Geophysical priori-embedded optimization A fine-tuning paradigm embedding structural tensors and fault-response features is proposed. Geological rules are enforced via adversarial gradient reversal, delivering professional-grade segmentation that preserves stratigraphic continuity and fault discontinuity boundaries.

While the current framework advances fault interpretation robustness, limitations persist in multi-physics data integration, real-time processing efficiency, and generalization to complex tectonic regimes. Future work will prioritize cross-domain adversarial augmentation, lightweight uncertainty distillation, and extended geological constraints incorporating plate motion priors to achieve industry-ready deployment.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, Z. et al. Challenges and opportunities for carbon neutrality in China. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3(2), 141–155 (2022).

Hettema, M. Analysis of mechanics of fault reactivation in depleting reservoirs. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 129, 104290 (2020).

Li, P. et al. Stability analysis of U-shaped horizontal salt cavern for underground natural gas storage. J. Energy Storage 38, 102541 (2021).

Xiong, W. et al. Seismic fault detection with convolutional neural network. Geophysics 83(5), O97–O103 (2018).

Freeman, B., Boult, P. J., Yielding, G. & Menpes, S. Using empirical geological rules to reduce structural uncertainty in seismic interpretation of faults. J. Struct. Geol. 32(11), 1668–1676 (2010).

Shaw, J. H., Connors, C., & Suppe, J. Seismic interpretation of contractional fault-related folds. American Association of Petroleum Geologists (2005).

Wang, X. et al. Study on gas migration through cement microstructure under multi-field effects during offshore gas storage well construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 460, 139846 (2025).

Cao, Z. et al. Diffusion evolution rules of grouting slurry in mining-induced cracks in overlying strata. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 1–20 (2025).

Lin, L. et al. Machine learning for subsurface geological feature identification from seismic data: Methods, datasets, challenges, and opportunities. Earth-Sci. Rev. 104887 (2024).

Di, H., Shafiq, M. A., Wang, Z. & AlRegib, G. Improving seismic fault detection by super-attribute-based classification. Interpretation 7(3), SE251–SE267 (2019).

Guitton, A., Wang, H. & Trainor-Guitton, W. Statistical imaging of faults in 3D seismic volumes using a machine learning approach. In SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 2017 2045–2049 (Society of Exploration Geophysicists, 2017).

Di, H., Shafiq, M. A. & AlRegib, G. Seismic-fault detection based on multiattribute support vector machine analysis. In SEG International Exposition and Annual Meeting SEG-2017 (SEG, 2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. An intelligent lithology recognition system for continental shale by using digital coring images and convolutional neural networks. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 239, 212909 (2024).

Wang, L., Zhu, L., Xue, Y., Cao, X. & Liu, G. Multiphysics modeling of thermal–fluid–solid interactions in coalbed methane reservoirs: Simulations and optimization strategies. Phys. Fluids 37(7) (2025).

Wu, X., Liang, L., Shi, Y. & Fomel, S. FaultSeg3D: Using synthetic data sets to train an end-to-end convolutional neural network for 3D seismic fault segmentation. Geophysics 84(3), IM35–IM45 (2019).

Tang, Z., Wu, B., Wu, W. & Ma, D. Fault detection via 2.5 d transformer u-net with seismic data pre-processing. Remote Sens. 15(4), 1039 (2023).

Wang, Z., You, J., Liu, W. & Wang, X. Transformer assisted dual U-net for seismic fault detection. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1047626 (2023).

Bomfim, L., Cunha, O., Kuroda, M., Vidal, A. & Pedrini, H. Transformer model for fault detection from Brazilian pre-salt seismic data. In Brazilian Conference on Intelligent Systems 3–17 (Springer, 2023).

Cheng, T. et al. Yolo-world: Real-time open-vocabulary object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 16901–16911 (2024).

Sheng, H. et al. Seismic foundation model: A next generation deep-learning model in geophysics. Geophysics 90(2), IM59–IM79 (2025).

Liu, N. & Sun, F. Seismic fault interpretation by using a multi-scale coherence attribute. In 82nd EAGE Annual Conference & Exhibition Vol. 2021, no. 1 1–5 (European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers, 2021).

Marfurt, K. J., Kirlin, R. L., Farmer, S. L. & Bahorich, M. S. 3-D seismic attributes using a semblance-based coherency algorithm. Geophysics 63(4), 1150–1165 (1998).

Roberts, A. Curvature attributes and their application to 3 D interpreted horizons. First Break 19(2), 85–100 (2001).

Zhang, F., Liu, J., Liu, Y., Li, H. & Jiang, X. Data-model-interactive enhancement-based Francis turbine unit health condition assessment using graph driven health benchmark model. Expert Syst. Appl. 249, 123724 (2024).

Cubuk, E. D., Zoph, B., Mane, D., Vasudevan, V., & Le, Q. V. Autoaugment: Learning augmentation policies from data. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.09501 (2018).

Zhang, F. et al. Data-model interaction-driven transferable graph learning method for weak-shot onsite FTU health condition assessment. Adv. Eng. Inform. 65, 103364 (2025).

Teng, T., Chen, Y., Wang, Y. & Qiao, X. In situ nuclear magnetic resonance observation of pore fractures and permeability evolution in rock and coal under triaxial compression. J. Energy Eng. 151(4), 04025036 (2025).

Jocher, G., Chaurasia, A., & Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLO (Version 8.0.0) [Computer software]. https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (2023).

Bai, X. et al. Enhanced domain tuned yolo-driven intelligent fault identification method: Application in selection and construction of gas storage. Well Logging Technol. 49(01), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.16489/j.issn.1004-1338.2025.01.006 (2025).

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R. & Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 779–788 (2016).

Zhou, T., Li, Q., Lu, H., Cheng, Q. & Zhang, X. GAN review: Models and medical image fusion applications. Inf. Fusion 91, 134–148 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Numerical study of hydraulic fracturing in the sectorial well-factory considering well interference and stress shadowing. Pet. Sci. 20(6), 3567–3581 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Research on the storage performance evaluation and economic prediction of catalyzed green methanol underground. Appl. Energy (2025) (In Press).

Zhang, F., Tang, J., Zhou, J., Liu, Y., Li, J., Zeng, Y., ... & Hu, W. Securing CO2 storage in fractured reservoirs: Intelligent characterization ofcritical natural fracture pathways. Fuel 406, 136915 (2026).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Oil & Gas Pipeline Network Corporation for providing the field dataset in this study.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U24B2034); National Science and Technology Major Projects of China (No. 2025ZD1401107); National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52104029); Shanghai Rising-Star Program (No. 24QA2709700).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yun Liu and Jizhou Tang* conceived the study and designed the methodology. Fengyuan Zhang and Shijie Zhao developed the computational framework, implemented the reinforcement learning components, and conducted experiments. Huanyu Zou and Famu Huang curated seismic datasets, performed geological validation, and analyzed fault sealing implications. Ziheng Zhu and Jinshuo Yan contributed to uncertainty quantification, annotation optimization, and geophysical constraint modeling. Yun Liu and Fengyuan Zhang drafted the manuscript with critical revisions from Jizhou Tang. Fengyuan Zhang, Shijie Zhao and Sirui Jiang* visualized results and performed statistical validation. All authors reviewed experimental outcomes, interpreted results, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Zhang, F., Zou, H. et al. An end-to-end fault interpretation method driven by visual foundation model with domain adaptation fine-tuning. Sci Rep 15, 42032 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23044-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23044-5