Abstract

Genome rearrangement is a hallmark of cancer and ageing. DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are highly toxic lesions that can generate genome rearrangements. Several pathways compete for DSB repair, and selection of the appropriate repair process is critical for genetic stability. DSB repair acts according to two steps: (1) the choice between nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) and the resection of DNA ends, generating single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and (2) on generated ssDNA, homologous recombination (HR) and sub-processes. Here, we show that 53BP1, which plays a prime role in the first step by protecting against resection and fostering NHEJ, physically interacts with the catalytic subunits of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKAcs). PKA favours the recruitment of 53BP1 at DNA damage sites and consistently prevents resection, favouring NHEJ. Inhibition of PKA stimulated resection and concurrently reduced NHEJ. Conversely, the activation of PKA with 8-Bromo-cAMP stimulated NHEJ and reduced HR. These data provide new avenues for potential anticancer strategies. More generally, these findings underscore the high complexity of the regulation of DSB repair, identifying PKA as a novel participant in the DNA damage response that acts in the DSB repair process, which may be essential for maintaining genome integrity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genome instability is a hallmark of both cancer and ageing1,2,3,4,5,6. The genome is assaulted daily by different stresses, including both endogenous and exogenous stresses. Remarkably, activation of the DNA damage response (DDR) has been observed at early stages of cancer and senescence7,8,9, suggesting that genetic stresses represent an initial step in these processes.

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are considered the most toxic type of lesion and are also a prominent source of genetic instability through both genome rearrangements and mutagenesis at the sites of repair junctions. However, DSB repair is also used by the cell to generate beneficial genetic diversity in physiological processes such as the establishment of the immune repertoire, meiosis and neuronal gene expression (for review, see So et al.10). In these physiological situations, DSBs are generated by controlled cellular enzymes, after which cells use the same DSB repair machinery as accidental DSBs. Consequently, DSB repair should be finely regulated to maintain the balance between genetic stability and diversity. Therefore, the selection of the most adapted DSB repair pathway becomes a crucial issue.

Two main strategies are used to repair DSBs. One strategy is nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ), which ligates two DNA double-strand ends without requiring sequence homology. In this process, the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer binds to the DSB and recruits DNA-PKcs, ligase IV and its cofactors, such as XRCC4 and Cernunos/XLF10,11,12,13,14,15.

The second DSB repair strategy is based on the use of homologous sequences present in an intact DNA molecule that will be copied; this mechanism is thus called homologous recombination (HR). HR acts on 3’-single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) arising from the resection of the DSB ends, on which RAD51 is loaded by BRCA2. This generates a ssDNA/RAD51 filament that promotes the search for an homologous partner and strand invasion.

The choice of the DSB repair process operates in two steps10,13,16,17: 1- selection of NHEJ versus resection and 2- on resected ssDNA, HR and sub-processes. Consistent with this model, studies in mammalian cells have shown that defects in NHEJ stimulate HR11,12,18,19. 53BP1 plays a prime role in this initial step. Indeed, 53BP1 protects DNA ends from resection, thus favouring NHEJ, and depletion of 53BP1 abrogates HR defects in BRCA1-deficient human cells20.

NHEJ is efficient throughout the cell cycle, whereas HR acts in the S/G2 phases. Therefore, these processes compete in the late S and G2 phases. Thus, to explore the effect of 53BP1 on the choice of DSB repair mechanism, we performed a proteomic screen by immunoprecipitation of 53BP1 in the G2 phase and mass spectrometry analysis to identify partners of 53BP1 that might participate in the choice of DSB repair process, i.e., those that can act both on NHEJ and in HR. This analysis revealed the association of 53BP1 with the cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PKAcs).

PKA has been shown to act on DNA-PKcs, Ligase IV, XRCC4 and Cernunos/XLF; thus, at late steps, downstream the early step of choice between NHEJ and resection, but contradictory consequences for NHEJ efficiency have been reported21,22,23,24,25,26. Here, we show that PKAcs physically interact with 53BP1 and favour the recruitment of 53BP1 to damaged DNA following ionizing radiation (IR). Consistently, we show that PKA protects against resection and favours NHEJ. These data reveal that PKA also acts at the early steps of DSB repair. These findings open new avenues for potential anticancer strategies, and highlight the high complexity of the regulation of DSB repair, identifying a novel actor, PKA, as an actor of the DDR at the choice of the DSB repair process, which may be essential for maintaining genome stability.

Results

PKAcα interacts with 53BP1

Using mass spectrometry, we previously analysed the interactors of 53BP1 in cells synchronized in G2 with RO-3306 through coimmunoprecipitation with 53BP1 antibodies (data to be published). The relevance of these interactions was supported by the fact that the canonical interactors of 53BP1, Tp53, and DNA-PKcs, which plays an important role in NHEJ, were both identified in the proteomic analysis.

Notably, the data also revealed the presence of PKAcα. Additionally, cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulatory type II-α and type II-β (RIIα and RIIβ) subunits were also identified, supporting an interaction between 53BP1 and PKA type II.

Next, we tested the physical interaction between PKAcs and 53BP1 via coimmunoprecipitation in human cell lines (SV40-transformed fibroblasts). In asynchronous cells, the immunoprecipitation of 53BP1 did not result in significant pull down of PKAcs (Fig. 1A). However, in G2-synchronized cells (with RO-3306), PKAcs efficiently coimmunoprecipitated with 53BP1 (Fig. 1A). To confirm these data and the subcellular localization, a proximity ligation assay (PLA) was performed (Fig. 1B). The data confirmed the close colocalization of PKAcs and 53BP1 in G2-synchronized cells but not in asynchronous cells (Fig. 1B). In addition, PLA revealed the colocalization of PKAcs and 53BP1 in the nucleus. Collectively, these data reveal the interaction of PKAcs and 53BP1 into the nucleus in G2 arrested cells.

Physical interaction between 53BP1 and PKA in G2/M. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation in asynchronous (treated with DMSO) cells and G2/M (RO-3306)-arrested cells. Uncropped gels are shown in supplementary data. The lower panel shows the effects of DMSO (left panel) and RO-3306 (right panel) on the cell cycle distribution. (B) Proximity ligation assay. Upper panel: representative images of PLA with the PKAcs antibody alone (left panel), the 53BP1 antibody alone (middle panel), and both the PKAcs and 53BP1 antibodies (right panel). Scale bars: 10 µm. Lower panel: quantification (median) of at least 3 independent experiments (p values: * < 0.05, ** < 0.01).

Following exposure to genotoxic stress (here, hydroxyurea (HU), which generates replication stress), the cells were less efficiently arrested in the G2/M phase than in the RO-3306 phase, and more cells were arrested in the S phase, particularly at the highest dose, 100 μM HU (compare Figs. 1A and 2A). Nevertheless, PKAcs and 53BP1 were also able to interact in cells arrested with HU in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2). Moreover, such interactions were also detected in another cell line, U2OS (human osteosarcoma), and were also increased following exposure to HU (Supplementary data Fig. S1).

PLA 53P1/PKA after exposure to hydroxyurea. (A) Representative images of PLA with PKAcs antibody alone (left panel), 53BP1 antibody alone (middle panel), and both PKAcs and 53BP1 antibodies (right panels) at two different doses of HU. Scale bars: 10 µm. Right panels: effect of the treatment on the cell cycle distribution. (B) Quantification (median) of at least 3 independent experiments (p values: * < 0.05, ** < 0.01).

PKAcs favours the assembly of 53BP1 at DNA damage sites

53BP1 assembles into nuclear foci, corresponding to DNA damage sites in chromatin27. Ionizing radiation (IR) is a convenient genotoxic treatment for measuring the kinetics of 53BP1 foci formation (Fig. 3A) because the treatment is short (approximately 2 Gy/min), and then the kinetics are monitored from a precise starting point. The peak of 53BP1 foci assembly occurred between 30 and 45 min after 2 Gy irradiation (Fig. 3B). Remarkably, PKA was activated by IR, as monitored by the phosphorylation of its effector CREB, with a peak at 30–45 min after radiation, and this effect was inhibited by the PKA inhibitor H89 (Fig. 3C and D), and corresponded to the kinetics of 53BP1 foci assembly. Similarly, PKA was also activated in U2OS cells 30 min after IR (Supplementary data Fig. S2).

Effect of PKA on 53BP1 foci assembly after ionizing radiation (IR). (A) Representative image of nuclear 53BP1 foci after IR (right panel). Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) Kinetics of 53BP1 foci assembly after IR (2 Gy). Upper panel: silencing of PKAcs with siRNA. Lower panel: quantification of 53BP1 (means ± SEMs) foci assembly at different times after IR, with siCTRL (sicontrol) or siPKAcs (20 nM). The data represent at least 3 independent experiments (p values: * < 0.05). (C) Kinetics of pCREB phosphorylation after IR. (D) Effect of the PKA inhibitor H89 on IR-induced pCREB. Uncropped gels are shown in supplementary data.

Silencing PKAcs with siRNA reduced the efficiency of 53BP1 foci formation 30–45 min after IR (Fig. 3B). These data show that PKA participates in the DSB response, favouring the assembly and stabilization of 53BP1 at damaged DNA.

PKA prevents excessive resection of DSBs

The first step of the selection of the competing DSB repair pathways involves the choice between resection initiation and protection against resection of the DSB10,13,16. The absence of resection orientates DSB repair towards NHEJ, whereas resection engages DSB repair towards HR. This choice must be tightly controlled to optimize DSB repair with other cellular parameters, such as the cell cycle; indeed, HR is active only in the S/G2 phase, whereas NHEJ is active throughout the cell cycle18,28,29,30. Errors in appropriate DSB repair pathway selection can jeopardize genome stability. By preventing resection, 53BP1 plays a prime role in this process and thus favours NHEJ. On the basis of the above data, we next tested the effect of PKA on DSB resection.

We used the DIvA system, which allows the quantification of resection at different distances from an Asi-SI cutting site in the genome31,32. Nuclear translocation of the restriction enzyme Asi-SI is induced by 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4-OH-TAM), which then cleaves at restriction sites into the genome, after which the DNA is extracted. Resection of Asi-SI-induced DSBs will generate single-stranded DNA, which is resistant to subsequent in vitro cleavage by restriction enzymes. Because the Asi-SI sites have been mapped, we monitored cleavage at different restriction sites located at different distances from the Asi-SI site. With the use of specific primers, PCR allows the quantification of uncleaved DNA (resulting from resection) and thus extended resection (Fig. 4A). We measured resection at a site located on chromosome 22 that has been mapped and used in previous studies31,32. Resection decreased with increasing distance from the Asi-S1 cleavage site, as predicted, thus validating the approach (Fig. 4B). As a control, silencing CtIP, which initiates resection, significantly decreased the resection efficiency (Fig. 4B). In contrast, silencing 53BP1 strongly stimulated resection (Fig. 4B), which is consistent with its role in protection against resection. Consistent with the above data, silencing PKAcα also stimulated resection. Therefore, PKA favours protection against resection.

Effect of PKA on resection. (A) Scheme of the experimental strategy. The DIvA system is a U2OS cell containing an inducible Asi-SI endonuclease31,32. Nuclear translocation of the restriction enzyme Asi-SI is induced by 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4-OH-TAM), which then cleaves at restriction sites and then DNA. Resection of the Asi-SI-induced DSB will generate single-stranded DNA, which is then resistant to subsequent in vitro cleavage by the restriction enzyme BanI. We monitored cleavage at different BanI cleavage restriction sites located at different distances from the Asi-SI site on chromosome 22, which has been mapped and used in previous studies31,32. With the use of specific primers, PCR allows the quantification of uncleaved DNA (resulting from resection) and thus the extent of resection. (B) Quantification of the different siRNAs used for resection indicated in the figure. The distances of BanI from the Asi-SI site are indicated. The quantification corresponds to the means (± SEM) of 5 independent experiments.

Activation of PKA promotes NHEJ

Because 53BP1 prevents resection and promotes NHEJ, we next measured the effect of PKA on NHEJ. To monitor NHEJ, we used the reporter substrate described in Fig. 5A in human SV40-transformed fibroblasts (CG92), which has been largely characterized11,12,16,17,33,34,35. Silencing PKAcs with siRNA decreased the efficiency of NHEJ (Fig. 5B). Next, we compared the effects of stimulating and inhibiting PKA using Bromo-8-cAMP and H89, respectively. Inhibition of PKA with H89 confirmed the decrease in NHEJ efficiency (Fig. 5C). Reciprocally, activation of PKA activity with 8-Bromo-cAMP increased NHEJ efficiency (Fig. 5C). Moreover, the stimulation of NHEJ by Bromo-8-cAMP was abrogated by cotreatment with H89 (Fig. 5B). Notably, similar results were obtained in U2OS cells (Supplementary data Fig. S3).

Effect of PKA on NHEJ. (A) Strategy and reporter substrate used. Here, the substrate is chromosomally integrated into the genome of SV40-transformed human fibroblasts16. Before cleavage, the cells express the reporter H2Kd. The reporter CD4 is not expressed because it is too far from the promoter (prom). Two cleavage sites for the meganuclease I-SceI (18 nt recognition) are inserted, one between the promoter and the H2Kd sequence and the other between the H2Ks and CD4. The expression of I-SceI results in targeted cleavage of the two I-SceI sites and excision of the H2Kd intervening fragment. The end-joining of the DSBs that bear no sequence homology put the CD4 reporter under the control of the promoter, leading to its expression. The frequency of CD4-positive cells thus provides an estimation of NHEJ efficiency. This substrate has been largely validated and characterized11,12,16,17,33,34,35. (B) Effect of silencing PKA with siRNA. The values are shown normalized to those of the control siRNA and represent the average ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. (C) Effect of stimulating PKA (8-Bromo-cAMP) and inhibiting PKA (H89) on NHEJ. Upper panel: scheme of the experiment. Lower left panel: expression of I-SceI under different conditions. Uncropped gels are shown in supplementary data. Lower right panel: NHEJ efficiency under the different conditions. The values are shown normalized to those of the control (DMSO) and represent the average ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

Collectively, these data show that the activity of PKA increases NHEJ efficiency. These data are consistent with the fact that activation of PKA promotes 53BP1 assembly to damaged DNA and prevents the resection of double-strand DNA ends.

Stimulation of PKA affects homologous recombination

Next, we tested the effect of PKA on HR that is initiated by resection and competes with NHEJ. In a siRNA screen, the silencing of PKA was found to stimulate HR36. This finding is consistent with our findings that silencing PKA increases resection (see Fig. 4), which corresponds to the first step of HR. Therefore, we next addressed the effect of PKA stimulation. To monitor HR, we used the DR-GFP substrate37 (Fig. 6A) with human SV40-transformed fibroblasts (RG37)38, which share the same origin as the GC92 cell line used for monitoring NHEJ above16. HR is strictly cell cycle controlled and is active in the S/G2 phase. We thus first verified whether stimulation with PKA affects the cell cycle distribution of RG37 cells. Treatment with Bromo-8-cAMP led to no significant changes in the cell cycle distribution, other than possibly resulting in a small accumulation of cells in the G1 phase (Fig. 6B).

Effect of PKA stimulation on HR. (A) Strategy and reporter substrate used. Here, the DR-GFP substrate is chromosomally integrated into the genome of SV40-transformed human fibroblasts38. DR-GFP contains a tandem repeat of two inactive EGFP-encoding genes (upper panel). The 5’ repeat is interrupted by the I-SceI cleavage sequence (18 nt), and the 3’ repeat is truncated both at the 5’ and 3’ ends. None of these sequences were expressed and the cells were GFP negative. The expression of the I-SceI enzyme results in a cleavage target into the 5’ repeat (the SceGFP cassette); gene conversion (HR) with the 3’ repeat (iGFP) recreates a functional EGFP, leading to the fluorescence of cells37. Recombinant cells can be detected via FACS. (B) Cell cycle distribution in GC92 cells (human fibroblasts) after I-SceI transfection and PKA activation (8-Bromo-cAmp). The image shows 3 independent experiments. (C) Effect of stimulation of PKA by 8-Bromo-cAMP on HR after I-SceI transfection. Upper panel scheme of the experiment. Uncropped gels are shown in supplementary data. The values are shown normalized to those of the control (DMSO) and represent the average ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

Consistent with the data above, stimulation of PKA activity with Bromo-8-cAMP decreased HR efficiency (Fig. 6C). The putative small accumulation in the G1 phase may, at least in part, contribute to the decrease in HR efficiency, but this may not be significant. Moreover, similar results were obtained in another cell line, U2OS (Supplementary data Fig. S4).

The engagement of DSB repair toward NHEJ should result in a decrease in competing repair processes such as HR. Collectively, these data are consistent with the results of stimulation of HR after silencing PKA with a siRNA36 and with the above data on resection and NHEJ.

Discussion

DSB is a very toxic lesion that can also generates profound genome rearrangements10,13. However, DSBs are also used by cells in physiological mechanisms such as meiosis or the establishment of the immune system. Several repair mechanisms compete for DSB repair. Precise control of DSB repair is essential for selecting the most appropriate DSB repair mechanism, according to cell physiology, to maintain genome stability10,39. The first step in the choice of the DSB repair pathway is the competition between NHEJ and resection10,13,16,17,40. Resection is necessary to initiate DSB repair via HR. At this essential initial step, 53BP1 plays a pivotal role by preventing resection favouring NHEJ10,39. Here, we show that PKA plays a role in this early step of DSB repair. We show that PKA physically interacts with 53BP1, facilitating or stabilizing the binding of 53BP1 to damaged DNA. Consistent with these data, PKA prevents resection, favouring NHEJ. In a mirror effect, the silencing of PKA, which increases resection, as shown here (see Fig. 4), has been shown to stimulate HR36, which is consistent with the fact that HR is initiated by resection. Similarly, we show here that stimulating PKA, which stimulates NHEJ (see Fig. 5), leads to a decrease in HR (see Fig. 6).

Analysis of the 53BP1 sequence in phosphosite databases predicted at least 12 potential sites of phosphorylation by PKA in 53BP1. Therefore, determining whether PKA phosphorylates 53BP1 and identifying the sites at which 53BP1 is phosphorylated by PKA represents an exiting but considerable challenge for future experiments.

An effect of PKA on NHEJ has been previously reported, but the results and conclusions are contradictory. Notably, the previous reports all show an effect of PKA at late steps of DSB repair, i.e., downstream of the choice between NHEJ and resection. A negative impact of cAMP signalling has been described in non-small cell lung cancer (NSLC) cells through the phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs, which plays a central role in NHEJ in mammalian cells, and the recruitment of XRCC4 and ligase IV, i.e., at the last step of NHEJ21. In this study, DSB repair was analysed after IR or on transient episomic plasmids. In both cases, this analysis yielded a great number of DSBs. Indeed, the number of transfected plasmid molecules can be very high and the number of DSBs following IR is estimated to be 40 DSBs/Gy, and the experiments were performed at 2 Gy21. Our reporter substrate was chromosomally integrated, resulting in full chromatin regulation (in contrast with episomic-transfected plasmids), and corresponded to a unique site. Therefore, the effect of PKA on NHEJ may be different on intrachromosomal sequences and/or differ according to the number of DNA ends, as reported for MRE1141. In contrast to this report, but in agreement with our present data, other reports indicate a positive impact of PKA on NHEJ. PKA has been shown to promote the entry of DNA-PK into the nucleus in HEK-B2 cells25. PKA activates DNA-PK expression and upregulates ligase IV in retinal endothelial cells23,26. Notably, the expression of ligase IV is controlled by pCREB, an effector of PKA, in retinal neurocytes23. This finding is consistent with the activation of CREB phosphorylation after IR, as also shown here. In all these cases, PKA promotes NHEJ. Thus, the type of cell tissue may affect the impact of PKA on NHEJ21. Finally, in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the yeast orthologue of PKA, Tpk1, promotes NHEJ through the phosphorylation of Nej1, an NHEJ factor22. In mammalian cells, PKA has been shown to phosphorylate Cernunos/XLF, the Nej1 mammalian orthologue that is a cofactor of ligase IV, thus acting at the last step of NHEJ. Here, we show that PKA physically interacts with 53BP1, preventing resection and acting at the first step of DSB repair, orienting the choice of the repair mechanisms. Collectively, these data highlight the high complexity of the regulation of DSB repair by PKA, which can act both at early and late steps of NHEJ. The roles of PKA in NHEJ are summarized in Fig. 7.

The different roles of PKA in NHEJ. At the earliest step of DSB repair, PKA promotes and/or stabilizes the loading of 53BP1 on DSBs, impairing resection and fostering NHEJ. Resection repression leads to decreased HR efficiency. However, PKA can also act at later steps of NHEJ through the nuclear translocation of DNA-PK and the expression of NHEJ factors, including ligase IV and its cofactors (XRCC4 and XLF/Cernunos).

We have shown that stimulating PKA activity decreases HR. This finding is consistent with the fact that PKA activity also stimulates NHEJ. Therefore, stimulation of PKA activity, by modifying the balance between NHEJ and HR in favour of NHEJ, should lead to a decrease in HR.

These data potentially open new avenues for future therapeutic strategies. Indeed, since NHEJ plays an important role in resistance to ionizing radiation, decreasing NHEJ efficiency, through PKA inhibition, may increase the efficiency of radiation therapy. Moreover, HR-deficient cells are sensitive to PARP inhibitors through a synthetic lethality process42,43. Unfortunately, most tumours are proficient for HR. Therefore, the inhibition of HR may make any tumour eligible for PARP inhibitor therapy. Our data revealed that stimulation of PKA activity can alter HR. However, increasing NHEJ via PKA stimulation may counteract the sensitivity to PARP inhibitors resulting from HR inhibition. Therefore, these effects of PKA on DSB repair may allow the combination of different alternative strategies that deserve to be addressed in the future, providing the opportunity to adapt potential treatments.

PKA should be considered as an actual actor of DDR. Indeed, our data reveal that PKA is an important novel actor at the initial step of DSB repair, controlling the choice of DSB repair process, which may have an effect on genome stability maintenance and lead to potential enticing novel therapeutic strategies. This should confer a role to PKA in very precise regulation(s), allowing selecting the most appropriate DNA repair system according to different cellular and tissues parameters, in order to efficiently maintain genome stability.

Methods

Cells

GC9216 and RG3738 cells were derived from a common SV40-transformed fibroblast line, a gift from R.J. Monnat Jr (University of Washington). They were originally obtained from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Human Genetic Mutant Cell Repository (Camden, N.J.). CG92 cells contain the CD4-3200 bp substrate, which monitors the EJ-mediated deletion of a 3200 bp fragment via expression of the membrane antigen CD411,12,16,17,33,44,45. RG37 contains the DR-GFP substrate37 that monitors HR through GFP expression.

AID-DIvA (AID-AsiSI-ER-U20S) is a U2OS cell line (human osteosarcoma) in which AsiSI endonuclease-induced DSBs at specific regions in the genome. AsiSI is sequestered in the cytoplasm, but the addition of 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4OHT; 300 nM, Sigma‒Aldrich, H7904) to the culture medium for 4 h induces the translocation of AsiSI into the nucleus, which then cleaves DNA. After 4OHT treatment, the cells were washed three times in prewarmed PBS and further incubated with 500 µg/ml auxin (IAA) (Sigma‒Aldrich, I5148) for 2 h to induce the degradation of AsiSI46. The medium was subsequently changed, and the cells were cultured for 18–20 h before DNA collection.

All the cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and were checked monthly for mycoplasma contamination via PCR (primers 5′ GGGAGCAAACAGGATTAGATACCCT 3′ and 5′ TGCACCATCTGTCACTCTGTTAACCTC 3′).

Transfection

The meganuclease I-SceI was expressed by transient transfection of the HA-I-SceI expression plasmid47 in RG37 and GC92 cells with Jet-PEI following the manufacturer’s instructions (Ozyme, #POL101-40N). The expression of HA-tagged I-SceI was verified by Western blotting. For RNA-silencing experiments, 25,000 cells were seeded 1 day before transfection performed using INTERFERin following the manufacturer’s instructions (Polyplus Transfection, New York, NY, USA, #POL409-50) with 20 nM of either control siRNA (5′ UAAGGCUAUGAAGAGAUAC(dTdT) 3′), synthesized by Eurofins (Ebersberg, Germany), or PKAcs siRNA (Cell Signaling, 6574). Seventy-two hours later, the cells were transfected with the pCMV-HA-I-SceI expression plasmid.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence experiments were performed on cells grown on glass coverslips. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 15 min at RT. Soluble proteins were extracted before fixation by incubating coverslips with extraction buffer (50 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete Mini Protease Inhibitor, Roche, 5892970001)) for 5 min on ice. After the samples were blocked in PBS containing 3% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20, immunostaining was performed using mouse anti-53BP1 (1:500, Merck Millipore, MAB3802) and rabbit anti-PKAc (1:100, Cell Signaling, mAb 5842) antibodies. After 2 washes with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, the coverslips were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488- and/or 568-conjugated anti-mouse (Life Technologies, 1:500, A11029) and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Life Technologies, 1:1000, A11036). All the incubations were performed for 45 min at RT with antibodies diluted in PBS containing 3% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20. After 2 washes, the coverslips were mounted in mounting medium (Dako, S302380-2) supplemented with DAPI (Sigma‒Aldrich). Images were acquired using a Leica SPE confocal laser scanning microscope or an Olympus BX63 microscope with a 63 × oil objective. Images were imported, processed and merged via ImageJ 1.53 h software (https://imagej.net/ij/).

Analysis of DSB repair at the CD4-3200 bp intrachromosomal reporters

After transfection with the I-SceI expression plasmid and incubation for 72 h, the cells were collected with 50 mM EDTA diluted in PBS, pelleted and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. The cells were incubated for 10 min with 1 µl of an Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody (rat isotype, RM4-5; Invitrogen). The percentages of CD4-expressing cells were determined via FACS analysis using a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). To eliminate variability due to the transfection efficiency, all values were normalized to those for control cells transfected with the I-SceI plasmid alone.

Where indicated, the cells were treated with 20 µM PKA inhibitor H89 (Sellekchem, S1582) or 50 µM PKA activator Bromo-8-cAMP (Sigma, B5386) during the first 48 h after I-SceI transfection. The medium was subsequently changed for the remaining 48 h of incubation before the cells were collected for FACS analysis.

Western blot analysis

The cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.1% SDS supplemented with Complete Mini Protease Inhibitor (Roche) and treated with 250 U of benzonase (Santa Cruz, sc202391) for 30 min. The proteins (30–40 µg) were denatured, separated on 9% SDS‒PAGE gels, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, which were subsequently incubated with the following specific antibodies: rabbit anti-PKA (1:500, Cell Signaling, mAb 5842), mouse anti-HA (1:1500, Santa Cruz, sc-7392), rabbit anti-pCREB (1:1000, Cell Signaling, #9198 ), anti-53BP1 (1:100, Merck Millipore, MAB3802) and mouse anti-vinculin (1:5000, Abcam, ab18058). Immunoreactivity was visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kit (Pierce).

Proximity ligation assay (PLA)

Cells grown on coverslips were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized, blocked and prepared as described above for immunostaining with the following primary antibody pairs: mouse anti-53BP1 (1:100, Merck millipore, MAB3802) and rabbit anti-PKAcs (1/100, cell signaling, mAb 5842).

PLA was performed using a Duolink In Situ Detection Kit (Sigma‒Aldrich, DUO92001, DUO92005, DUO92008) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Images were acquired with a Leica SPE confocal laser scanning microscope using a 63 × objective lens. The images were processed with ImageJ software.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Cellular proteins were extracted on ice using 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP40 and cOmplete Mini Protease Inhibitor (Roche). Protein extracts were treated with DNase I (15 U/ml, Thermo Scientific, EN0521) for 30 min at RT. The extracts were precleared with Dynabeads (Life Technologies, 10004D) for 30 min at 4 °C, and 300 µg of protein was then incubated with 1 µg of a mouse anti-53BP1 antibody (1 μg/ml, Merck Millipore, MAB3802) O/N at 4 °C. Then, 25 µl of Dynabeads was added, and the mixture was incubated for 4 h at 4 °C. The beads were subsequently washed three times with extraction buffer. Laemmli buffer (2 ×) with 4% ß-mercaptoethanol was used to dissociate and denature the bead‒antibody‒protein complexes. Western blot analysis was performed to detect 53BP1and PKAcs via a rabbit anti-53BP1 antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling, #4938) and a rabbit anti-PKAcs antibody (1:500, Cell Signaling, mAb 5842), respectively.

Foci counts

Foci were automatically counted with ImageJ using the following method.

To define a mask with nuclei in the DAPI channel, Image/Adjust/Threshold/Analyze/Analyze Particles was used. In the foci channel, all the particles in the ROI manager were selected, followed by “OR (Combine)”. All the nuclei are outlined in the foci image. To define the threshold for counting foci, we used Process/Find Maxim and “Single Points” as the output type, and we determined the correct value for detecting the majority of foci (this value should not vary between images in the same experiment). A new window then appeared. In the ROI Manager, “Measure” was used. In the results datasheet, the number of foci by nucleus was obtained by dividing the “Raw Integrated Density number” value by the “Max” value (255).

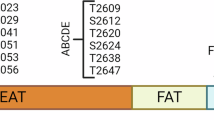

Resection assay

Resection measurements in DIvA cells were performed as previously described31. After 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen treatment, the cells were collected for genomic DNA extraction (DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and 100–200 ng of genomic DNA was treated with 16 U of the appropriate restriction enzyme overnight at 37 °C. After enzyme inactivation, the digested genomic DNA was used for qPCR (mixed for qPCR, Takara, Shiga, Japan) with the primers listed in Table 1.

The percentage of ssDNA was calculated with the following equation: ssDNA % = 1/(2^(△Ct-1) + 0.5)*100, where △Ct = Ct of the digested sample – Ct of the nondigested sample.

Synchronization in G2 with RO-3302

The cells were treated with 7 µM RO-3306 (Calbiochem 217699) 22 h before being fixed and analysed.

nLC-MS/MS analysis

Proteins were extracted with 190 mM ammonium bicarbonate and digested overnight using an on-bead digestion method with trypsin at 37 °C at pH 7.8. The eluted peptides were desalted on Vivapure C18 micro spin columns (Sartorius Stedim Biotech) and desiccated in a SpeedVac.

The dried peptides were resuspended in 10 µl of 0.1% formic acid, and 1 µl was injected for nLC-MS/MS analysis in triplicate. Liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry analyses were performed on an EASY-nLC 1000 paired with a Q Exactive quadrupole-orbitrap hybrid mass spectrometer (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific). The peptides of each sample were separated on an EASY-Spray 15 cm × 75 µm 3 µm 100 Å C18 PepMap® reverse-phase column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a 150 min three-step water‒acetonitrile gradient (0–120 min, 5 → 35% LC buffer B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile); 120–140 min, 35 → 50%; 140–145 min, 50 → 90%; hold for 5 min) at a 300 nL/min flow rate. The mass spectrometers acquired data in positive mode throughout the elution process and operated in a data-dependent scheme with full MS scans acquired, followed by up to 10 successive MS/MS fragmentations and measurements of the most abundant ions detected. The MS scan range was set at 400–2,000 m/z, with a resolution of 70,000, an AGC target of 1E6 and an MIT of 100 ms. MS2 measurements were set at a resolution of 17,500, an AGC target of 5E4, an MIT of 100 ms and an isolation window of 2 m/z, a collision energy of 27 and a 30 s dynamic exclusion.

The raw mass spectrometric data were analysed via Proteome Discoverer using the Homo sapiens Swiss-Prot database. A maximum of 2 missed cleavages was allowed. The precursor mass tolerance was set to 10 ppm, and the fragment mass tolerance was 0.02 Da. Carbamidomethylation of cysteines was set as a constant modification. Deamidation of asparagine and glutamine and oxidation of methionines were set as variable modifications. The false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated using Percolator with 0.01 strict and 0.05 relaxed target cut-off values.

Statistical analysis

Unpaired t tests or Kolmogorov‒Smirnov tests were performed using Graphpad Prism version 6.0c (https://www.graphpad.com/).

Data availability

All the data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. Additional details or explanations are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Negrini, S., Gorgoulis, V. G. & Halazonetis, T. D. Genomic instability–An evolving hallmark of cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 220–228 (2010).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 (2011).

López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M. & Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153, 1194–1217 (2013).

Garinis, G. A., van der Horst, G. T. J., Vijg, J. & Hoeijmakers, J. H. J. DNA damage and ageing: New-age ideas for an age-old problem. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1241–1247 (2008).

Hoeijmakers, J. H. DNA damage, aging, and cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 1475–1485 (2009).

López-Otín, C., Pietrocola, F., Roiz-Valle, D., Galluzzi, L. & Kroemer, G. Meta-hallmarks of aging and cancer. Cell Metab. 35, 12–35 (2023).

Bartkova, J. et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature 434, 864–870 (2005).

Gorgoulis, V. G. et al. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature 434, 907–913 (2005).

Bartkova, J. et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints. Nature 444, 633–637 (2006).

So, A., Le Guen, T., Lopez, B. S. & Guirouilh-Barbat, J. Genomic rearrangements induced by unscheduled DNA double strand breaks in somatic mammalian cells. FEBS J. 284, 2324–2344 (2017).

Guirouilh-Barbat, J. et al. Impact of the KU80 pathway on NHEJ-induced genome rearrangements in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell 14, 611–623 (2004).

Guirouilh-Barbat, J., Rass, E., Plo, I., Bertrand, P. & Lopez, B. S. Defects in XRCC4 and KU80 differentially affect the joining of distal nonhomologous ends. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 20902–20907 (2007).

Bétermier, M., Bertrand, P. & Lopez, B. S. Is non-homologous end-joining really an inherently error-prone process?. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004086 (2014).

Deriano, L. & Roth, D. B. Modernizing the nonhomologous end-joining repertoire: Alternative and classical NHEJ share the stage. Annu. Rev. Genet. 47, 433–455 (2013).

Scully, R., Panday, A., Elango, R. & Willis, N. A. DNA double-strand break repair-pathway choice in somatic mammalian cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 698–714 (2019).

Rass, E. et al. Role of Mre11 in chromosomal nonhomologous end joining in mammalian cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 819–824 (2009).

So, A. et al. RAD51 protects against nonconservative DNA double-strand break repair through a nonenzymatic function. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 2651–2666 (2022).

Delacôte, F. et al. An xrcc4 defect or Wortmannin stimulates homologous recombination specifically induced by double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3454–3463 (2002).

Pierce, A. J., Hu, P., Han, M., Ellis, N. & Jasin, M. Ku DNA end-binding protein modulates homologous repair of double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 15, 3237–3242 (2001).

Bunting, S. F. et al. 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in brca1-deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell 141, 243–254 (2010).

Noh, S. E. & Juhnn, Y. S. Inhibition of non-homologous end joining of gamma ray-induced DNA double-strand breaks by cAMP signaling in lung cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–15 (2020).

Jessulat, M. et al. The conserved Tpk1 regulates non-homologous end joining double-strand break repair by phosphorylation of Nej1, a homolog of the human XLF. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 8145–8160 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Lithium promotes DNA stability and survival of ischemic retinal neurocytes by upregulating DNA ligase IV. Cell Death Dis. 7 (2016).

Castejón-Griñán, M., Herraiz, C., Olivares, C., Jiménez-Cervantes, C. & García-Borrón, J. C. CAMP-independent non-pigmentary actions of variant melanocortin 1 receptor: AKT-mediated activation of protective responses to oxidative DNA damage. Oncogene 37, 3631–3646 (2018).

Huston, E. et al. EPAC and PKA allow cAMP dual control over DNA-PK nuclear translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 12791–12796 (2008).

Zhang, Q. & Steinle, J. J. DNA-PK phosphorylation of IGFBP-3 is required to prevent apoptosis in retinal endothelial cells cultured in high glucose. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54, 3052–3057 (2013).

Anderson, L., Henderson, C. & Adachi, Y. Phosphorylation and rapid relocalization of 53BP1 to nuclear foci upon DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 1719–1729 (2001).

Guirouilh-Barbat, J., Huck, S. & Lopez, B. S. S. S-phase progression stimulates both the mutagenic KU-independent pathway and mutagenic processing of KU-dependent intermediates, for nonhomologous end joining. Oncogene 27, 1726–1736 (2008).

Saintigny, Y. et al. XRCC4 in G1 suppresses homologous recombination in S/G2, in G1 checkpoint-defective cells. Oncogene 26, 2769–2780 (2007).

Delacote, F., Lopez, B. S. S., Delacôte, F. & Lopez, B. S. S. Importance of the cell cycle phase for the choice of the appropriate DSB repair pathway, for genome stability maintenance: The trans-S double-strand break repair model. Cell Cycle 7, 33–38 (2008).

Zhou, Y., Caron, P., Legube, G. & Paull, T. T. Quantitation of DNA double-strand break resection intermediates in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, e19 (2013).

Cohen, S. et al. Senataxin resolves RNA:DNA hybrids forming at DNA double-strand breaks to prevent translocations. Nat. Commun. 9, 533 (2018).

Grabarz, A. et al. A role for BLM in double-strand break repair pathway choice: Prevention of CtIP/Mre11-mediated alternative nonhomologous end-joining. Cell Rep. 5, 21–28 (2013).

Guirouilh-Barbat, J. et al. 53BP1 Protects against CtIP-dependent capture of ectopic chromosomal sequences at the junction of distant double-strand breaks. PLoS Genet. 12, (2016).

Matos-Rodrigues, G. et al. In vivo reduction of RAD51 -mediated homologous recombination triggers aging but impairs oncogenesis. EMBO J. 42, 1–21 (2023).

Adamson, B., Smogorzewska, A., Sigoillot, F. D., King, R. W. & Elledge, S. J. A genome-wide homologous recombination screen identifies the RNA-binding protein RBMX as a component of the DNA-damage response. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 318–328 (2012).

Pierce, A. J., Johnson, R. D., Thompson, L. H. & Jasin, M. XRCC3 promotes homology-directed repair of DNA damage in mammalian cells. Genes Dev 13, 2633–2638 (1999).

Dumay, A. et al. Bax and Bid, two proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members, inhibit homologous recombination, independently of apoptosis regulation. Oncogene 25, 3196–3205 (2006).

Symington, L. S. & Gautier, J. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45, 247–271 (2011).

Thomas, M., Dubacq, C., Rabut, E., Lopez, B. S. & Guirouilh-Barbat, J. Noncanonical Roles of RAD51. Cells 12, 1169 (2023).

Lee, J. H. & Paull, T. T. Direct activation of the ATM protein kinase by the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 complex. Science 304, 93–96 (2004).

Farmer, H. et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 434, 917–921 (2005).

Bryant, H. E. et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 434, 913–917 (2005).

Gelot, C. et al. The cohesin complex prevents the end joining of distant DNA double-strand ends. Mol. Cell 61, 15–26 (2016).

Guirouilh-Barbat, J. et al. 53BP1 protects against CtIP-dependent capture of ectopic chromosomal sequences at the junction of distant double-strand breaks. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006230 (2016).

Aymard, F. et al. Transcriptionally active chromatin recruits homologous recombination at DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 366–374 (2014).

Liang, F., Han, M., Romanienko, P. J. & Jasin, M. Homology-directed repair is a major double-strand break repair pathway in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. U. S. A. 95, 5172–5177 (1998).

Acknowledgements

We thank Emilie Cochet (Gustave Roussy Cancer Institute), Emilie-Fleur Gautier and Virginie Salnot (Institut Cochin) for their help with the mass spectrometry analyses.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Institut National du Cancer (PLBIO21-072, PLBIO24-196-2024-158), La Ligue Nationale Contre Le Cancer (ARN thérapeutiques), Ligue régionale contre le cancer (comité Ile de France), (ITMO Cancer (PCSI 2022), and Fondation ARC (ARCPJA2022060005157).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: BSL; funding acquisition: BSL; investigation: HKS, IM, VO, ED, ER, JGB; methodology: HKS, BSL, IM, VO, ED, ER, JGB; project administration: BSL; resources: BSL; supervision: BSL; validation: HKS, IM, VO ED, ER, JGB and BSL; writing the original draft: BSL; and writing – reviewing & editing: all the authors but VO.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khater-Sellou, H., Dardillac, E., Rabut, E. et al. PKA prevents the resection of DNA double-strand breaks and favours nonhomologous end-joining. Sci Rep 15, 39684 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23200-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23200-x