Abstract

To comprehensively compare the risk of cardiotoxicity with 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (5-HT3RAs) and to explore the underlying pharmacokinetic factors that might contribute to cardiotoxicity. The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) data (January 2004 to March 2023) were extracted. Disproportionality analysis, sensitivity analyses, and time-to-onset assessments were conducted to evaluate cardiac risk signals associated with 5-HT3RAs. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models were developed to study the drug distribution characteristics in cardiac tissues. After excluding duplicate reports, a total of 1174 reports of cardiotoxicity related to 5-HT3RAs (including ondansetron, granisetron and palonosetron) were identified in the FAERS database. Removing cases with diagnosed heart disease and electrolyte disorders at baseline, all cardiotoxicity signals persisted except the arrhythmia signal in palonosetron. Stratified sensitivity analyses (pre-/post-2012 FDA safety alert) revealed the signal for electrocardiogram QT prolonged persisted both in pre-alert and post-alert. Palonosetron demonstrated a longer latency than ondansetron and granisetron, which exhibited similar time-to-onset values. The PBPK model extrapolation results showed that ondansetron concentration in cardiac tissue was 2.3 times higher than that in plasma, which might support that it is more susceptible to cardiotoxicity. The study revealed that different 5-HT3RAs exhibited varying degrees and types of cardiotoxicity. Among these, ondansetron demonstrated the highest signals of cardiotoxicity, followed by palonosetron, with granisetron showing the least. Ondansetron concentration in cardiac tissue far exceeded that in plasma, which might partially explain the observed cardiotoxicity. In conclusion, it suggested to prioritize low cardiac toxicity 5-HT3RAs for patients especially for those with heart diseases, and to strengthen the monitoring and management of cardiac toxicity furtherly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nausea and vomiting are the most prevalent and distressing adverse events (AEs) experienced by cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy1. The drugs 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (5-HT3RAs), a class of commonly used clinical antiemetic agents, play a pivotal role in the prophylaxis of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting, including chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV), radiotherapy-related and postoperative nausea and vomiting2,3. However, as a commonly used adjuvant drug for cancer patients, the AEs of 5-HT3RAs receive insufficient attention, probably attributed to that people are more concerned about the response and toxicity of tumor treatment drugs4. According to FDA drug label, ondansetron and granisetron were categorized as high cardiotoxicity risk drugs in the Drug-Induced Cardiotoxicity Rank5. However, the warnings primarily emphasize the risk of QT interval prolongation, with a significant lack of evidence concerning other AEs in the cardiac system. Recent analysis indicate that QT prolongation can be induced by a single intravenous dose of ondansetron in adult emergency department patients6. However, in non-specialized clinical settings, routine electrocardiogram monitoring is often omitted before and after ondansetron administration, which may lead to underdetection and underreporting of QT interval prolongation events7. Furthermore, ondansetron was observed to be related with postoperative atrial fibrillation and acute kidney injury. This suggests a complex multi-systemic risk profile that remains underrecognized, particularly in vulnerable patient populations8. Additionally, a series of case reports observed torsade de pointes (TdP), bradycardia and cardiac arrest after 5-HT3RAs infusion9,10,11, which has drawn researcher attention to cardiotoxicity associated with 5-HT3RAs. As a vital organ of the body, heart damage may lead to grave even fatal adverse consequences, especially for those patients with heart disease. Currently, there appears to be a relative scarcity of comprehensive comparative research on the cardiotoxic AEs associated with different 5-HT3RAs on a significant scale. Given the widespread global use of 5-HT3RAs and the serious hazards of cardiac AEs, it is imperative to commit more detailed and specific comparisons for drugs among 5-HT3RAs, which might provide evidence-based reference for prescribing optimal 5-HT3RAs to patients.

Generally, the target tissues or site-specific drug concentration is the most direct indicator of safety, which might partially explain some concentration-related adverse reactions. It is reported that ondansetron exerts a more pronounced inhibitory effect on human cardiac K+ HERG channels than other 5-HT3RAs12. This enhanced blockade may contribute to prolonged cardiac repolarization, occurring with a concentration-dependent manner12. It is important to evaluate the exposure levels of 5-HT3RAs in cardiac tissues to further investigate the potential contributors of cardiotoxicity. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model is an effective tool for surveying the time-varying process of drug exposure level in tissues and organs by simulating the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion process of drugs in the body. This study aimed to investigate the signal of cardiotoxicity associated with 5-HT3RAs utilizing The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database and examine the cardiotoxicity reasons from the perspective of pharmacokinetics by a PBPK model.

Results

Data from the FAERS analysis

Descriptive analysis

After excluding duplicate and invalid entries, about 66,032 AEs associated with 5HT3RAs were identified in the FAERS database, of which 1174 were cardiac AEs of interest (Table 1). The incidence of cardiotoxic AEs presented a rising trend post-2012 and peaked in 2018 (Fig. 1A). Remarkably, the overwhelming majority (96.7%, n = 1135) of cardiac AEs were linked to ondansetron, and the most prevalent cardiotoxicity type was electrocardiogram QT prolonged (Fig. 1B). The median age was 49 years (interquartile ranges (IQR) 32–60 years) (Fig. 1D), and females accounted for 51.45% of the cases (Fig. 1C). Healthcare professionals contributed to a significant proportion of the reporters (78.62%), and the United States was the primary reporting country (60.56%). Hospitalization (49.06%) emerged as the predominant outcome of these cardiac AEs (Fig. 1E).

Information about 1174 cases with cardiac adverse events associated with 5-HT3RAs. A Distribution of occurrence years. B Types of cardiac adverse events. C Distribution of sex. D Distribution of age. E Distribution of adverse events outcomes. F TTO of 5-HT3RAs-related cardiac AEs. TTO time-to-onset, 5-HT3RAs 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, AEs adverse events. The pie chart on the left shows the proportional distribution of all TTO, while the right side one indicates the specific distribution of TTO within 30 days.

Reported TTO analysis

After eliminating erroneous reports, 194 cardiac AEs were analyzed for TTO and the outcome is illustrated in Fig. 1F. It indicated that the median onset time of cardiac AEs associated with 5-HT3RAs was 0.5 days (IQR 0.5–7.5 days), and the majority of cases occurred within the first month of treatment initiation (92%, n = 179), even 72% (n = 140) happened within 5 days. Additionally, it is observed that the cardiac AEs associated with 5-HT3RAs appeared with similar probability within the 30 to 360-day period throughout the year, with the exception of a particularly high incidence in the first month. This suggests that AEs could occur at any stage of treatment, underscoring the importance of continuous monitoring, especially during the early phase.

The results of the goodness-of-fit tests indicated that the lognormal model best described the latency of cardiac AEs associated with ondansetron and granisetron, while the weibull model was the best fit for palonosetron (Supplemental Table S1). Accordingly, granisetron was classified as a random failure type, while ondansetron and palonosetron were categorized as wear-out failure type. In the TTO analysis based on parameter distributions and the valid cases, the IQR for cardiac AEs associated with ondansetron, palonosetron, and granisetron were 0.5 (0.5–7.5, n = 173), 4.5 (1–395.5, n = 11), and 0.5 (0.5–2.5, n = 10), respectively (Supplemental Table S2).

Disproportionality analysis

The disproportionality analysis results are depicted in Fig. 2. The analysis mainly included ondansetron, granisetron, and palonosetron. (tropisetron with only 15 AEs was excluded, and dolasetron was excluded because the number of single interested cardiac events was less than 3). Of which, ondansetron exhibited significantly higher signal values compared to other 5-HT3RAs, with a TdP ROR025 of 22.94 (ROR 26.44, 95% CI 22.94–30.48) and electrocardiogram QT prolonged ROR025 of 11.21 (ROR 12.34, 95% CI 11.21–13.60).

A ROR of cardiac AEs associated with 5-HT3RAs. B The Sankey diagram illustrates the relationship between the PTs and 5-HT3RAs. C The spectrum of cardiac AEs in different 5-HT3RAs. “a” the reports number of cardiac AEs associated with 5-HT3RA, “b” the reports number of 5-HT3RA AEs other than cardiac AEs, ROR reporting odds ratio, IC025 the lower end of the 95% confidence interval of the information component, PT preferred term, 5-HT3RA 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, AEs adverse events, CI confidence interval. The numbers in blocks represent the value of IC025 of each cardiac AEs induced by target 5-HT3RAs.

Sensitivity analysis

Supplemental Fig. S1 displayed the outcomes of sensitivity analyses. Removing cases with heart disease diagnosis and electrolyte disorders at baseline, the arrhythmia signal in palonosetron disappeared with original ROR025 = 1.36 (ROR 1.69, 95% CI 1.36–2.09) (removal of cardiac disease diagnosis ROR025 = 0.61 [ROR 1.89, 95% CI 0.61–5.87], and removal of electrolyte disorders ROR025 = 0.60 [ROR 1.85, 95% CI 0.60–5.75]), while the other signals persisted. The signal for electrocardiogram QT prolonged persisted both pre-alert 7.72 (ROR 11.55, 95% CI 7.72–17.27) and post-alert 11.61 (ROR 12.8, 95% CI 11.61–14.11). In contrast, the cardiomyopathy signal post-alert disappeared (ROR 1.44, 95% CI 0.91–2.29; ROR025 < 1) compared to pre-alert one (ROR 5.75, 95% CI 2.99–11.07). Signals such as TdP, arrhythmia, and ventricular fibrillation persisted in both periods.

In Supplemental Fig. S2, each point indicates ondansetron related-AEs and specifically highlights the PT names of AE signals that are significant (P < 0.05) at both Log2 (ROR) values and −Log10 (adjusted P values). Interestingly, despite the higher number of total ondansetron AE cases in females (Supplemental Table S3), male patients showed stronger signals for cardiac AEs such as electrocardiogram QT prolonged, arrhythmia, pericardial effusion, myocardial infarction and cardiomyopathy.

Characterization of ondansetron distribution in cardiac organs

Given that ondansetron exhibited a stronger signal intensity for cardiotoxic AEs among the 5-HT3RAs and was associated with a broad range of AEs, a PBPK model was established to simulate the drug concentration-time curve of ondansetron based on clinical demographic characteristics and dosing regimens (Supplemental Fig. S3). The results demonstrated that 76.3% of the clinically measured drug concentration-time points fell within the 95% CI of the simulated value. Goodness-of-fit plots revealed that most extrapolate values were within a 2.0-fold error range of the measured values (Fig. 3, Supplemental Table S4). The fold errors between extrapolated and observed values of ondansetron pharmacokinetic parameters (AUC, Cmax) were within the 2.0 range (Supplemental Table S5). In addition, the AFE and AAFE values for concentration-time data points were 1.47 and 1.53, respectively. These findings indicated that the PBPK model possessed high accuracy for extrapolating the plasma and tissue concentrations of ondansetron.

The goodness of fit plots of final model. The black line signifies that the observed concentrations are equal to the predicted ones. Black and grey dotted lines were obtained by scaling the observed concentrations by a factor of 2 and 1.25, respectively. Different colours represent concentrations measured in different studies (more detailed information can be found in the supplementary document).

The pharmacokinetic profiles of ondansetron in plasma and cardiac tissue were explored in four different doses, which are recommended by the guidelines3 (Fig. 4). The AUC of single intravenous or oral doses of ondansetron is approximately 1.4 times higher than those in plasma. Notably, the maximum concentration of ondansetron in cardiac tissue was up to 2.3 times greater than that in plasma following a single intravenous dose (Supplemental Table S6).

Discussion

This study revealed that different drugs of 5-HT3RAs presented varying degrees and types of cardiotoxicity. Among these, ondansetron demonstrated the highest signals of cardiotoxicity, followed by palonosetron, with granisetron showing the least. The result might provide evidence-based recommendations to prescribe low cardiac toxicity 5-HT3RAs for patients with heart diseases, and to enhance monitoring practices. Furthermore, it might raise public awareness regarding the safety of adjuvant oncology medications.

To our knowledge, this is the first study integrating pharmacokinetic into pharmacovigilance analyses to explore the potential underlying pharmacokinetic factors of AEs. We initially described the clinical characteristics of patients who experienced cardiotoxic reactions after 5-HT3RAs treatment in FAERS database. Notably, the number of reported cardiotoxic AEs remained relatively stable from 2004 to 2012, yet with a significant increase in cases following 2012. The FDA issued a safety bulletin regarding ondansetron potentially prolonging the QT interval and resulting in lethal arrhythmias in 2012. It is reasonable to assume that the announcement of safety bulletin heightened awareness of 5-HT3RAs-related cardiac AEs among the medical community and public, subsequently, increasing the reporting frequency. We conducted sensitivity analyses to specifically address the potential bias causing by the 2012 alert. The stability of electrocardiogram QT prolonged signals (ROR025 pre-alert: 7.72 [ROR 11.55, 95% CI 7.72–17.27] versus post-alert: 11.61 [ROR 12.8, 95% CI 11.61–14.11]) suggests that the QT electrocardiogram prolongation signal for ondansetron predated the alert and was not merely a consequence of stimulated reporting following alert. Notably, the disappearance of the cardiomyopathy signal post-alert may reflect the safety alert likely influence reporting behavior for less frequently reported adverse events. Patients over 60 years of age who were associated with cardiotoxic AEs related to 5-HT3RAs accounted for 26.4% of the non-missing age data in the FAERS database, which is consistent with the literature findings9,10,11. Given that older cancer patients, who are also the main recipients of 5-HT3RAs, often have multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy13, they may face an elevated risk of cardiac AEs. Notably, serious fatal cases were also predominantly observed in older patients10, highlighting the need for caution when using medications in this population.

Next, in our sensitivity analyses, we found that electrolyte imbalances and the presence of underlying cardiac disease significantly impact cardiac safety, particularly with the use of drugs such as palonosetron. Hypokalemia could lead to QT interval prolongation and TdP14 by enhancing cardiomyocyte excitability. This condition often coexists with hypomagnesemia and hyperphosphatemia, further increasing the risk of cardiac AEs15. Crucially, underlying cardiac disease and electrolyte disturbances may augment susceptibility to drug-induced cardiotoxicity and potentially mask or exacerbate medicine-related cardiac issues. The results of sensitivity analyses excluding cases with baseline cardiac diseases and electrolyte disturbances showed that the arrhythmia signal associated with palonosetron became insignificant, suggesting that palonosetron-related arrhythmia may be primarily attributed to the patient’s pre-existing cardiac risk factors. This finding emphasizes the importance of evaluating a patient’s baseline cardiac status before administrating palonosetron, facilitating a more precise risk assessment to mitigate the risks.

Furthermore, this study found that ondansetron exhibited a significantly high signal values of QT interval prolongation and TdP, which is consistent with previous researches6,16. Our PBPK model showed a significant accumulation of ondansetron drug concentrations in cardiac tissue, which may exacerbate its’ effects on blocking potassium channels, thus leading to a prolongation of the QT interval and TdP. The finding sustained the cardiotoxicity of ondansetron from the pharmacokinetic perspective. However, these insights are specific to ondansetron and may not be applicable to granisetron or palonosetron due to their distinct pharmacokinetic properties. In contrast, the QT interval prolongation of palonosetron and granisetron is somewhat controversial. Kim et al. reported that palonosetron may cause a slight intraoperative QTc interval increase while without statistical significance17, and Morganroth J deemed that palonosetron does not influence QTc interval18. Several research disclosed that the association between granisetron and QT interval prolongation is weak and usually presented as transient or minimal cardiac AEs19. It is undeniable that differences in study designs may affect drug evaluation outcomes, hence, comprehensive prospective studies using uniform methodologies to assess the effects of three 5-HT3RAs on QT interval prolongation are warranted. Our results indicated a clear association between granisetron (with an ROR025 of 1.07 [ROR 2.25, 95% CI 1.07–4.72]) and palonosetron with QT interval prolongation (with an ROR025 of 3.42 [ROR 6.84, 95% CI 3.42–13.71]). In summary, physicians should be cautious in prescribing 5-HT3RAs especially ondansetron, particularly for patients with existing cardiac conditions or those concurrently taking medications that may prolong the QT interval. Regular electrocardiogram monitoring is essential to promptly identify and assess any changes in these patients.

Further analysis manifested that palonosetron (4.5 days, IQR 1–395.5 days) had a significantly longer latency compared with ondansetron (0.5 days, IQR 0.5–7.5 days) and granisetron (0.5 days, IQR 0.5–2.5 days). The PBPK model displayed that intracardiac ondansetron concentrations peaked rapidly, approximately 0.8 h after oral administration (Fig. 4D), which partially supported the finding that the latency of ondansetron cardiotoxic AEs was short. Palonosetron exhibits a 30- to 100-fold higher affinity for the 5-HT3 receptor than ondansetron and granisetron, and its long half-life20 results in its slower distribution and metabolism within the body, which implies that it takes more time to raise concentrations to the threshold of triggering cardiotoxic AEs, and therefore has an extended latency. Additionally, palonosetron shows allosteric interactions and positive cooperativity with the receptor, which is not presented in ondansetron and granisetron21. These findings suggest that palonosetron may possess a diverse pharmacokinetics mechanism of cardiotoxicity compared to other 5-HT3RAs, necessitating a longer duration of exposure to detect its toxic effects.

Our subgroup analysis revealed gender-specific disparities in the cardiotoxicity associated with 5-HT3RAs. Research revealed that females generally receive more frequent prescriptions across multiple drug classes (for instance antidiabetics, anticancer drugs) than males, potentially elevating risks of polypharmacy interactions22. Besides, the notable sex differences in pharmacokinetics also contribute to a higher incidence of AEs in females23. This is reflected in the results of our analysis that in terms of ondansetron—related AEs in the FAERS database, females have a higher proportion of all types of AEs (53.77%) compared to males (38.79%), but cardiotoxic AEs were more conspicuous in males. The cardiotoxic AEs such as electrocardiogram QT prolonged, arrhythmia, pericardial effusion, myocardial infarction and cardiomyopathy were stronger in males than in females with statistical significance (P < 0.05). Literature has demonstrated that estrogen estradiol exhibits significant cardioprotective effects, including the prevention of apoptosis, reduction of myocardial injury during ischemia and reperfusion, enhancement of mitochondrial function, and diminishments of oxidative stress24,25. However, it cannot rule out that the observed sex differences may arise from reporting biases, further research is needed to clarify whether men are generally at greater risk for cardiotoxicity to help clinicians better comprehend and predict drug responses in patients of different sexes.

In drug safety assessments, the AEs of a drug are closely associated with its concentration in specific target tissues. Among 5-HT3RAs, ondansetron exhibits significant cardiac-related signals, prompting to develop PBPK model to explore the pharmacokinetic factors. Traditionally, PBPK models pose challenges to parameterization due to the need to estimate the tissue-plasma partition coefficient and tissue protein binding ratio26. Fortunately, this issue has effectively been addressed by computer simulations of tissue composition, including neutral lipids, phospholipids, and water27. We further developed a validated PBPK model to extrapolate cardiac drug concentration, which showed that ondansetron concentrations in cardiac tissue were 2.3 times higher than that in plasma, probably due to its lipophilic properties28 and an apparent volume of distribution29. Moreover, the abundance of 5-HT3 receptors in cardiac mitochondria promotes selective accumulation of ondansetron in these regions, owing to its high receptor affinity30. The greater accumulation of the drug in the heart might partially explain the observed cardiotoxic effects. Importantly, the 8 mg intravenous dose resulted in higher cardiac concentrations than the 4 mg dose, indicative of a dose-dependent cardiac accumulation. This modeling extrapolation aligns with evidence from a prospective observational study indicating a dose-dependent effect of ondansetron on QT interval prolongation6. The PBPK modeling thus provided valuable insights that complemented the FAERS data, despite the high prevalence of missing or incomplete dosing information in FAERS, which failed to allow us to conduct dose-stratified studies.

We acknowledged that there are several inherent limitations in this study. First, the observational data from FAERS are not sufficient by themselves to establish causality. To strengthen the rigor of causal inferences, we adopted the following strategies to enhance the credibility of our conclusions: sensitivity analyses to mitigate confounding, assessment of temporal plausibility through TTO analysis, assessment of biological plausibility and coherence, as well as evaluation of external consistency. Second, the spontaneous reporting nature of FAERS database implies that AEs under-reporting may occur, and thus the number of reports may not comprehensively reflect the safety landscape of 5-HT3RAs. To mitigate under-reporting, we extended the data collection period to maximize the sample size, enabling a more comprehensive analysis of AEs and improving the robustness of our findings. Third, data from longitudinal studies are likely to offer richer evidence than voluntarily submitted pharmacovigilance information. Nonetheless, our study conducted extensive sensitivity analyses to eliminate the impact of underlying diseases on disproportionate signals detection, making the result more reliable and credible than those based solely on spontaneous reporting31. Fourth, the potential interaction between 5-HT3RAs and other antiemetics possessing independent cardiac risks warrants consideration32. To minimize confounding bias, we focused on reports listing 5-HT3 receptor antagonists as the primary suspected medication. We also performed combined medication analyses, but the available sample size was ultimately insufficient to support statistically robust sensitivity analyses. Future studies utilizing specialized clinical cohorts are needed to adequately explore these potential pharmacodynamic interactions. Finally, it is hard to measure true concentrations in human tissue level, which results in the difficulties of verifying the PBPK simulation analysis. However, we compared the consistency between the concentration-time curves extrapolated in our model and the corresponding real human plasma concentrations of ondansetron in literature. Utilizing PK-Sim and MoBi software, which provide a precise physiological foundation for accurately extrapolating organ concentrations33, further supports this study. Based on the above mentions and evidence indicating that drugs achieving high cardiac-to-plasma concentration ratios increase the risk of cardiotoxic effects34,35, we inferred that the drug accumulation in the heart might also significantly contribute to the risk of cardiotoxicity. Overall, despite the limitations, this study effectively quantified 5-HT3RAs-related cardiac AE risks. The temporal relationship, specificity (confounder-adjusted signals), and coherence (evidence synthesis) provides robust causal inference for ondansetron’s cardiotoxicity. However, our PBPK model currently includes only ondansetron and has not yet compared the pharmacokinetics of other 5-HT3RAs or influence factors such as sex. Future extensions of the model could include other 5-HT3RAs, as well as sex-stratified parameters to explore differences based on sex.

Conclusion

The results indicated that different 5-HT3RAs exhibit varying degrees and types of cardiotoxicity. Among these, ondansetron showed the highest cardiotoxicity signals, followed by palonosetron, with granisetron showing the least. The PBPK simulation analysis demonstrated that the concentration of ondansetron in cardiac tissues was considerably higher than that in plasma, suggesting that ondansetron could potentially pose a high risk of cardiotoxicity. Overall, it highlights the importance of enhancing monitor and assessment of cardiac-related AEs when administering 5-HT3RAs.

Methods

Overview

First, we described the clinical features of cardiotoxicity AEs related to 5-HT3RAs by analyzing data from the FAERS database. Then, the association between 5-HT3RAs and cardiotoxicity was assessed by analyzing metrics such as time-to-onset (TTO) and disproportionality scores. Finally, PBPK modeling was constructed to extrapolate the drug concentration distribution profile of ondansetron, which showed the strongest signal in cardiotoxic AEs and thereby provided a comprehensive perspective of drug safety.

Data sources and study design (FAERS)

FAERS is a robust pharmacovigilance database designed to aid regulatory bodies and healthcare practitioners in surveilling and overseeing drug safety, identifying potential safety concerns associated with medications, and ensuring public medication safety. Data are primarily collected through spontaneous reports submitted by healthcare providers, pharmaceutical companies, and patients (https://fis.fda.gov/extensionS/FPD-QDE-FAERS/FPD-QDE-FAERS.html), which provide information about adverse reactions, medication errors, product quality issues and therapeutic ineffectiveness, stemming from drug use, drug misuse, and manufacturing problems.

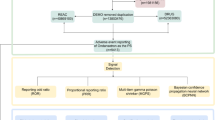

FAERS data from January 2004 to March 2023 were extracted and analyzed. The initiation time was selected based on the earliest time that relevant data were accessible in the FAERS database following FDA approval of the 5-HT3RAs medicines (including ondansetron, granisetron, palonosetron, dolasetron, and tropisetron)36. The flowchart of the FAERS analysis methodology is presented in Fig. 5 and additional files.

The flowchart of the FAERS database processing. FAERS US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System, DEMO demographics, DRUG drug, REAC reaction, INDI indication, RPSR reporting source, THER therapy, OUTC outcome, 5-HT3RAs 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, AEs adverse events, PTs preferred terms. All seven tables above are from the FAERS data file; “n” is the number of adverse drug reaction records in the FAERS database.

Definition of cases and drugs of interest

The Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) (version 26.0) Concept Libraries was used to standardize and map adverse drug reaction (ADR) descriptions within the FAERS database, employing preferred terms (PTs) for consistency. The detailed ADRs of interest are listed in Supplemental Table S7. Both generic and brand names sourced from Drugbank were input as keywords for the database retrieval. Only 5-HT3RAs with over 100 AE reports in FAERS database were included for analysis31 (tropisetron with only 15 AEs was excluded). To mitigate potential influence of confounders associated with non-cardiac AEs, our study exclusively focused on cases where 5-HT3RAs were designated as the ‘primary suspect’ for cardiotoxic AEs.

Reported TTO analysis

The Weibull, lognormal, gamma, and exponential distributions were tested for the TTO analysis, and the scale parameter α and shape parameter β were applied to characterize the parameter distributions37. The Akaike Information Criterion corrected (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and − 2 times the log-likelihood of the model (β) (− 2*Log L(β)) for all candidate distributions were calculated, and the one with smallest AIC, BIC and − 2*Log L(β) values was selected as the optimal parameter distribution model to describe the latency of cardiac AEs induced by 5-HT3RAs.

Data mining and statistical analysis

A case/non-case method was applied to analyze the extracted cases. The reporting odds ratio (ROR) and information component (IC) were calculated to determine whether ADRs were reported more frequently for specific drugs than for others in the dataset38. A significant risk signal is generated when the number of reports exceeds three and the lower limit of 95% confidence interval (CI) of ROR025 is greater than 1 or of IC025 is greater than 0 (dolasetron was excluded because the number of single interested cardiac event less than 3, see Supplemental Tables S8, S9)39. The magnitude of signal value reflected the strength of association between the suspected drug and ADR, namely, higher signal values suggest an increased likelihood of causing ADR40.

Sensitivity analyses

Post-hoc sensitivity analyses directed at the primary outcome of ROR were conducted to find potential confounding factors that may skew the baseline analysis41. The ROR values were recalculated after adjusting the sample in two separate ways: (1) excluding cases with possible cardiac AEs at baseline, (2) excluding cases with potential risk factors such as electrolyte disorder that could cause QT interval prolongation, (3) stratifying analyses by pre-2012 (January 2004 to December 2011) and post-2012 (January 2012 to March 2023) FDA safety alert periods to assess stimulated reporting bias. Furthermore, we delved into individual characteristics and explored sex-specific cardiac AEs associated with 5-HT3RAs (Supplemental Table S10), which was performed primarily for ondansetron because granisetron and palonosetron-associated cardiotoxic AEs ≤ 3 in both sexes.

Establishment and evaluation of the PBPK model

As ondansetron demonstrated the strongest pharmacovigilance signal for cardiotoxicity among the 5-HT3RAs, we investigated its pharmacokinetics to explore the possible factors. A publicly available PBPK model for ondansetron has effectively characterized its pharmacokinetic profile in healthy populations and demonstrated strong evaluative capability28,42,43. Building on this foundation, we further extended the PBPK framework to extrapolate the distribution characteristics of ondansetron in cardiac tissues using PK-Sim and MoBi software (version 9.0, https://open-systems-pharmacology.org, Supplemental Table S11). Based on the recommended dose range in clinical guidelines3, we simulated ondansetron with single doses of 4 mg, 8 mg, 0.15 mg/kg administered intravenously and 8 mg orally in a population sample of 1000 subjects with a 1:1 sex ratio to obtain the pharmacokinetic profiles of plasma and cardiac tissue for each dose regimen, respectively. To visually assess the model’s performance, we compared the agreement between real human plasma concentrations of ondansetron measured in 12 experiments and the corresponding concentration-time curves extrapolation in our PBPK model. Furthermore, the accuracy of model was rigorously validated by examining whether the expected values (the key pharmacokinetic parameters Cmax and AUCt−end) fell within 0.5 to 2 times the measured parameter values28. The average fold error (AFE) and average absolute fold error (AAFE) were also calculated for all concentration-time data points (see Supplementary file). This assessment approach ensured that the model possesses theoretical validity, high credibility, and strong generalization capability in practical applications.

Software

FAERS data were extracted and plotted using SAS (version 9.4), and R statistical computing language version (4.3.1) was utilized for data processing. Additionally, the published drug concentration-time plots were digitized by GetData Graph Digitizer software (GetData Graph Digitizer V.2.26.0.20 ©, S. Fedorov) to obtain concentration data. The PBPK analysis was performed in the PK-Sim and MoBi modeling environment (version 9.0, https://open-systems-pharmacology.org/).

Data availability

Pharmacovigilance data can be found at https://fis.fda.gov/extensionS/FPD-QDE-FAERS/FPD-QDE-FAERS.html. PBPK model data were derived from published studies.

References

Ning, C. et al. Research trends on chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting: a bibliometric analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1369442. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2024.1369442 (2024).

Herrstedt, J. et al. MASCC and ESMO guideline update for the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. ESMO Open 9, 102195 (2024). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.102195

Gan, T. J. et al. Fourth consensus guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth. Analg. 131, 411–448. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004833 (2020).

Juthani, R., Punatar, S. & Mittra, I. New light on chemotherapy toxicity and its prevention. BJC Rep. 2, 41. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44276-024-00064-8 (2024).

Qu, Y. et al. The largest reference list of 1318 human drugs ranked by risk of drug-induced cardiotoxicity using FDA labeling. Drug Discov. Today 28, 103770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2023.103770 (2023).

Rezaei, Z. et al. Single intravenous dose ondansetron induces QT prolongation in adult emergency department patients: a prospective observational study. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 17, 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-024-00621-5 (2024).

Romano, C., Dipasquale, V. & Scarpignato, C. Antiemetic drug use in children: what the clinician needs to know. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 68, 466–471. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000002225 (2019).

Xu, F., Gong, X., Chen, W., Dong, X. & Li, J. Ondansetron use is associated with increased risk of acute kidney injury in ICU patients following cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1511545. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2024.1511545 (2024).

Keith, S. et al. Ondansetron and hypothermia induced cardiac arrest in a 97-year-old woman: a case report. CVIA 7. https://doi.org/10.15212/CVIA.2022.0021 (2022).

Lee, D. Y., Trinh, T. & Roy, S. K. Torsades de pointes after Ondansetron infusion in 2 patients. Texas Heart Inst. J. 44, 366–369. https://doi.org/10.14503/thij-16-6040 (2017).

Al Harbi, M. et al. A case of granisetron associated intraoperative cardiac arrest. Middle East J. Anaesthesiol. 23, 475–478 (2016).

Kuryshev, Y. A., Brown, A. M., Wang, L., Benedict, C. R. & Rampe, D. Interactions of the 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 antagonist class of antiemetic drugs with human cardiac ion channels. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 295, 614–620 (2000).

Whitman, A., Erdeljac, P., Jones, C., Pillarella, N. & Nightingale, G. Managing polypharmacy in older adults with cancer across different healthcare settings. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 13, 101–116. https://doi.org/10.2147/DHPS.S255893 (2021).

Tsuji, Y. et al. Mechanisms of Torsades de pointes: an update. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1363848. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1363848 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. Serum electrolyte concentrations and risk of atrial fibrillation: an observational and Mendelian randomization study. BMC Genom. 25, 280. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-024-10197-2 (2024).

Singh, K. et al. Ondansetron-induced QT prolongation among various age groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Egypt Heart J. 75, 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43044-023-00385-y (2023).

Kim, H. J. et al. Effect of palonosetron on the QTc interval in patients undergoing Sevoflurane anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 112, 460–468. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aet335 (2014).

Morganroth, J., Flaharty, K. K., Parisi, S. & Moresino, C. Effect of single doses of IV palonosetron, up to 2.25 mg, on the QTc interval duration: a double-blind, randomized, parallel group study in healthy volunteers. Support Care Cancer. 24, 621–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2822-6 (2016).

Ganjare, A. & Kulkarni, A. P. Comparative electrocardiographic effects of intravenous ondansetron and granisetron in patients undergoing surgery for carcinoma breast: A prospective single-blind randomised trial. Indian J. Anaesth. 57, 41–45. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5049.108560 (2013).

Chen, R. et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety evaluation of oral palonosetron in Chinese healthy volunteers: a phase 1, open-label, randomized, cross-over study. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 160, 105752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2021.105752 (2021).

Rojas, C. et al. Palonosetron exhibits unique molecular interactions with the 5-HT3 receptor. Anesth. Analg. 107, 469–478. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e318172fa74 (2008).

Lacroix, C. et al. Sex differences in adverse drug reactions: are women more impacted? Therapie 78, 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.therap.2022.10.002 (2023).

Lee, S. M., Jang, J. H. & Jeong, S. H. Exploring gender differences in pharmacokinetics of central nervous system related medicines based on a systematic review approach. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 397, 8311–8347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-024-03190-9 (2024).

Visniauskas, B. et al. Estrogen-mediated mechanisms in hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases. J. Hum. Hypertens. 37, 609–618. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-022-00771-0 (2023).

Javed, A. et al. The relationship between myocardial infarction and Estrogen use: a literature review. Cureus 15, e46134. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.46134 (2023).

Yoshida, K., Budha, N. & Jin, J. Y. Impact of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models on regulatory reviews and product labels: frequent utilization in the field of oncology. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 101, 597–602. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.622 (2017).

Le Merdy, M., Spires, J., Tan, M. L., Zhao, L. & Lukacova, V. Clinical ocular exposure extrapolation for a complex ophthalmic suspension using physiologically based Pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation. Pharmaceutics 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16070914 (2024).

Alqahtani, F. et al. A physiologically based Pharmacokinetic model to predict systemic Ondansetron concentration in liver cirrhosis patients. Pharmaceuticals 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16121693 (2023).

Griddine, A. & Bush, J. S. in StatPearls (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. 5-HTR3 and 5-HTR4 located on the mitochondrial membrane and functionally regulated mitochondrial functions. Sci. Rep. 6, 37336. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37336 (2016).

Anand, K., Ensor, J., Trachtenberg, B. & Bernicker, E. H. Osimertinib-induced cardiotoxicity: a retrospective review of the FDA adverse events reporting system (FAERS). JACC CardioOncol. 1, 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccao.2019.10.006 (2019).

Kamath, A., Rai, K. M., Shreyas, R., Saxena, P. U. P. & Banerjee, S. Effect of domperidone, ondansetron, olanzapine-containing antiemetic regimen on QT(C) interval in patients with malignancy: a prospective, observational, single-group, assessor-blinded study. Sci. Rep. 11, 445. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79380-1 (2021).

Geci, R. et al. Systematic evaluation of high-throughput PBK modelling strategies for the prediction of intravenous and oral pharmacokinetics in humans. Arch. Toxicol. 98, 2659–2676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-024-03764-9 (2024).

Lu, H. R., Hermans, A. N. & Gallacher, D. J. Does terfenadine-induced ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation directly relate to its QT prolongation and Torsades de pointes? Br. J. Pharmacol. 166, 1490–1502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01880.x (2012).

Timour, Q. et al. Doxorubicin concentrations in plasma and myocardium and their respective roles in cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 1, 559–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02125741 (1988).

Machu, T. K. Therapeutics of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists: current uses and future directions. Pharmacol. Ther. 130, 338–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.02.003 (2011).

Zhou, J. X. et al. Exploration of the potential association between GLP-1 receptor agonists and suicidal or self-injurious behaviors: a pharmacovigilance study based on the FDA adverse event reporting system database. BMC Med. 22, 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03274-6 (2024).

Noguchi, Y., Tachi, T. & Teramachi, H. Detection algorithms and attentive points of safety signal using spontaneous reporting systems as a clinical data source. Brief. Bioinform. 22. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbab347 (2021).

Chen, C. et al. Cardiotoxicity induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: a pharmacovigilance study from 2014 to 2019 based on FAERS. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 616505. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.616505 (2021).

Liu, L. et al. Romosozumab adverse event profile: a pharmacovigilance analysis based on the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) from 2019 to 2023. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 37, 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-024-02921-5 (2025).

Burk, B. G. et al. Antipsychotics and obsessive-compulsive disorder/obsessive-compulsive symptoms: a pharmacovigilance study of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 148, 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13567 (2023).

Dallmann, A., Ince, I., Coboeken, K., Eissing, T. & Hempel, G. A physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for pregnant women to predict the pharmacokinetics of drugs metabolized via several enzymatic pathways. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 57, 749–768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-017-0594-5 (2018)

Job, K. M. et al. Development of a generic physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model for lactation and prediction of maternal and infant exposure to ondansetron via breast milk. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 111, 1111–1120. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.2530 (2022)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank FAERS.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yijun Cai: software, writing-original draft; Shaohong Luo: methodology, writing-original draft; Shen Lin: formal analysis, data curation; Xiaoting Huang: investigation; Xiangzhen Wang, Lijing Yang: validation; Xiongwei Xu, Xiuhua Weng: conceptualization, writing-reviewing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, Y., Luo, S., Lin, S. et al. Cardiotoxicity of different 5-HT3 receptor antagonists analyzed using the FAERS database and pharmacokinetic study. Sci Rep 15, 40919 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23217-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23217-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Serotonin-3 receptor antagonist-related cardiotoxicity

Reactions Weekly (2025)