Abstract

Additive manufacturing (AM) revolutionised the modern plastics industry. Its flexibility and ability to build almost any complex geometry without the need for conventional tooling or machining is especially desirable. In our article, we analysed two resins which can be processed by vat photopolymerisation: High Temperature and Rigid10K. They are especially recommended for rapid tooling because of their resistance to heat loads, high strength and stiffness. The application of vat photopolymerisation to produce prototype injection moulds is a definite novelty because the international research community has not realised the potential of this AM technology in rapid tooling. We performed dynamic mechanical analysis in temperature sweep and creep time temperature superposition (TTS) modes to determine the temperature-dependent stiffness and creep characteristics of the resins. The storage modulus of the High Temp resin was 2960 MPa at room temperature while it was 4055 MPa for Rigid10K. Their difference in storage modulus gradually diminished as they were heated to 123 °C. Above that, the High Temp resin showed higher modulus. The creep compliance of Rigid10K was considerably lower compared to the High Temp resin until 90 °C but it was excessive above that. After the material tests, two injection mould inserts were printed and post-cured. The inserts were fitted with strain gauges and thermocouples, which measured the operational deformations and the temperature of the inserts during injection moulding. The Rigid10K insert showed nearly an order of magnitude lower maximum deformation than the High Temp insert. The Rigid10K insert endured the injection moulding test while the High Temp insert cracked. The results proved that both resins are applicable in prototype injection mould making, but the durability of the Rigid10K insert is considerably better.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) technologies reshaped plastic part making1. These technologies make the direct production of 3D parts feasible with almost any complexity, in a single technological step2,3. AM can also produce moulds for conventional plastic processing technologies like injection moulding. Polymeric injection moulds can produce parts in low volumes, which is especially useful when physical product prototypes have to be manufactured and tested. These injection moulded prototypes provide vital information to determine the suitability of a product concept before a significant investment is made into large-volume production. This way, the costly design errors can be screened out at an early stage of the product development process. The ideal materials of polymeric low-volume injection moulds are heavily crosslinked photopolymer resins, which can be processed by material jetting (MJ) or vat photopolymerisation.

Material jetting already has a well-established record in low-volume mould making because of the excellent dimensional accuracy of the printed parts4,5. Bagalkot et al.6 applied MJ to print injection moulds from DigitalABS. They identified the injection moulding parameters which had the most influence on insert lifetime: mould temperature, injection pressure and speed, holding pressure and cooling time. Giorleo et al.7 also printed injection mould inserts from a high temperature (HT) resin because it has excellent stiffness and high glass transition temperature. The typical failure of the inserts was the chipping of the cavity edges and localised deformations on the cavity surface. Bagalkot et al.8 printed injection mould inserts from DigitalABS. They injection moulded polycarbonate because of the high required melt temperature (275 °C) and high injection pressure, which cause excessive thermomechanical load on the insert. They identified the typical failure modes of the mould inserts: burning and deterioration of the cavity surface, delamination and fracture. Stampone et al.9 injection moulded poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) at a high melt temperature (270 °C), high mould temperature (80 °C) and high injection pressure (800 bar) to analyse the applicability of polymeric injection mould inserts under extreme conditions. They also printed mould inserts from a HT resin using MJ and they applied thermal post-curing (65–75 °C for more than 8 h). The insert endured 15 injection moulding cycles before failure. Gülcür et al.10 analysed the applicability of MJ in micro injection moulding (MIM). They used X-ray computer tomography to check the dimensional accuracy of microfeatures on a polypropylene (PP) part injection moulded into a Vero PureWhite (RGD837) resin insert. They found the accuracy of MJ printing sufficient for MIM. Stampone et al.11,12 printed microfluidic injection mould inserts by MJ from a VisiJet M2S HT250 resin. They also proved that the printing resolution of MJ is ideal for prototype microfluidic injection moulds. Gülcür et al.13 demonstrated that the surface quality of MJ printed parts is determined by the surface finish method, which influences the demoulding force requirement of injection moulded parts.

Vat photopolymerisation is also steadily developing, and thorough reviews are available on the research directions and the potential applications14,15. The main research focus is on increasing the dimensional accuracy of parts printed by vat photopolymerisation. It is because vat photopolymerisation can only reach limited dimensional stability compared to MJ. Zhao et al.16 created a thermal model to calculate the temperature distribution of arbitrary geometries during printing, because thermal state has a vital role in reducing warpage and proper controlling of the vat photopolymerisation process. Choi et al.17 introduced the concept of a sub-build plate, where they printed the parts on a supplementary plate and performed the washing and the post-curing of the part while it was still on the plate. After the post-treatment, the plate was removed and the warpage of the printed part was checked. This way, they managed to halve the deformation of the printed part after post-treatment. Davoudinejad et al.18 created an experimental printer to build polymeric parts with microfeatures by vat photopolymerisation. They managed to print box features with an uncertainty of ± 27 μm and cylinder features with ± 18 μm. Kowsari et al.19 developed special resin formulations and managed to reduce printing resolution down to 7 μm in the lateral and 4 μm in the vertical direction. Special, experimental microstereolitography (µSl) devices also allow outstanding printing resolution (even 10 μm layer thickness)20. Stansbury et al.21 discussed the operation of various additive technologies in-depth. They highlighted that resins used in vat photopolymerisation have typically high photoinitiator content (3–5 wt%) to achieve fast polymerisation. However, this also results in significant residual initiator content after printing, which allows the later post-curing of the printed parts. Li et al.22 set up a theoretical model of the photopolymerisation process during digital light processing (DLP) printing (the relationship between the absorbed UV light energy and the cured thickness of the photosensitive resin). Westbeek et al.23 created a modelling method for the 3D simulation of DLP printing. They validated the capacity of their simulation to predict dimensional accuracy with 3D scanned images of actual printed parts and they proved the quality of their method. Yang et al.24 set up a mathematical model to determine the degree of curing in vat photopolymerisation (with 94% accuracy) and predict the tensile strength and hardness of the printed parts. Wu et al.25 analysed the distortion of thin-walled photopolymer parts, printed by DLP. They found that the warpage of the parts are determined by the degree of post-curing and the stiffness of the structure. Guven et al.26 created a mathematical model of the light-induced curing during DLP printing. They optimised the lighting of each layer using grayscaling to improve the dimensional stability of the printed parts and validated their method by actual printing trials. Dizon et al.27 reviewed the mechanical properties of parts manufactured by various additive technologies. They concluded that the mechanical properties of vat photopolymerisation printed parts are determined more by build layer thickness than printing orientation.

Vat photopolymerisation is used more and more in several different areas like medical applications or cellular structures. A prime application field of vat photopolymerisation is dentistry and dental implants because freeform and customised geometries can be printed even from biocompatible materials28. Melchels et al.29 concluded that vat photopolymerisation is suitable to print soft, freeform porous structures. Chartain et al.30 also found that vat photopolymerisation is ideal to print complex tissue scaffolds. Xu et al.31 reviewed the widespread application of vat photopolymerisation in the customised production of medical devices and implants. Alongside medical applications, sensor technology also uses vat photopolymerisation32. Despite the widespread application of vat photopolymerisation in medicine and sensor technology, the injection mould making and rapid prototyping industry has not explored the potential of the technology yet. Only a few case studies are available on the application of injection moulds printed by vat photopolymerisation. Davoudinejad et al.33,34 compared the behaviour of an insert printed by vat photopolymerisation with a machined steel insert. They applied a laser scanning digital microscope to measure the deformations of the polymeric inserts after injection moulding. They also set up a coupled thermomechanical finite element model to calculate the transient temperature distribution and the stress field of the injection mould inserts. The potential failure locations of the inserts were validated with actual measurements.

The conclusion of the literature review is that MJ is already a popular prototype injection mould making technology. On the other hand, vat photopolymerisation is rarely applied to make injection moulds, even though the available resins have adequate mechanical and thermomechanical properties. The main reason for this is that the dimensional accuracy of vat photopolymerisation is still behind that of MJ. This article demonstrates that injection mould inserts can be printed by vat photopolymerisation from state-of-the-art photopolymer resins and these resin inserts have acceptable dimensional accuracy and outstanding mechanical performance. The application of vat photopolymerisation in rapid tooling and prototype injection mould making allows the use of several high-performance resins in mould making, which is a significant novelty. This way, the application of vat photopolymerisation in rapid tooling can be expanded. Vat photopolymerisation has the advantage over MJ that some special, high-performance resins (fibre-reinforced resins or metal powder-filled resins) can only be processed by it. This study paves the way for the more widespread use of vat photopolymerisation and the high-performance photopolymers.

Materials and methods

Sample and mould insert printing and post-curing

We analysed two resins which are potentially suitable for prototype injection mould making: High Temperature (HT) and Rigid10K by Formlabs Inc. (Sommerville, United States). Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) specimens (4 × 10 × 59 mm) and one injection mould insert were printed from each material. The parts were printed with a Form2 stereolitography printer by Formlabs Inc. The specimens and the mould inserts were washed from the remaining resin in isopropyl alcohol with a FormWash unit. The parts made from the HT resin were washed for 5 min while the parts printed from the Rigid10K resin were washed for 20 min, in accordance with the recommended wash times35. Following the washing and the drying of the samples, the parts were post-cured in a Form Cure unit. The parts made from the HT resin were subjected to UV curing for 60 min at 60 °C, while the Rigid10K specimens were UV cured for 120 min at 80 °C, based on36.

According to the manufacturer, both resins are suitable for prototype injection mould making. It is because both materials have outstanding strength, stiffness, hardness and heat deflection temperature (HDT). These properties are all essential for applications where significant heat load is expected. If mould inserts are operated above their HDT, they fail relatively fast due to the excessive deformations. Table 1 shows the relevant mechanical and thermomechanical properties of the two resins after post-curing, according to their datasheets.

Material testing

The specimens were tested after combined thermal and UV light post-curing with a TA Instruments (USA) Q800 dynamic mechanical analyser (DMA). The specimens were tested in air atmosphere, in 3-point bending arrangement. The analysed temperature range was 25–170 °C for both materials. The frequency of loading was 1 Hz and the heating speed was 3 °C/min. The storage modulus and loss factor were measured.

Creep testing was also performed on a TA Instruments Q800 DMA in creep time temperature superposition (TTS) mode. Table 2 presents the creep testing parameters. The test temperature range was chosen to entirely include the possible operational temperatures of the mould inserts.

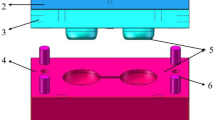

Comprehensive state monitoring of mould inserts

The comprehensive state monitoring system comprises of the measurement of temperature, strain, cavity pressure and the surface temperature of the polymeric mould inserts. Figure 1 presents the test mould setup. Strain is measured with two strain gauges (KMT-LIAS-06-3-350-5EL, Hungary) glued into the slots at the back of the moving-side insert. Strain data is gathered by a Spider 8 unit (Hottinger Baldwin Messtechnik GmbH, Austria). Temperature is measured by a thermowire (Ahlborn NiCr-Ni thermowire T 190-0) and the data is collected by an Ahlborn Almemo 8990–6 unit (Ahlborn Mess- und Regelungstechnik GmbH, Germany). The strain gauges and the thermowire were glued with a 3 M Scotch-Weld Plastic and Rubber Instant Adhesive PR100 (3 M Company, USA). The injection moulded product was a plate with dimensions of 65 mm × 55 mm × 2 mm. The cavity was filled through a 1 mm edge gate. The printed injection mould insert had the overall dimensions of 75 mm × 65 mm × 15 mm.

The injection moulding of samples

The plates were injection moulded from Tipplen H145F polypropylene homopolymer (MOL Group Plc., Hungary). Its recommended processing temperature range is low (190–235 °C) while its melt flow rate (MFR) is excellent (29 g/10 min at 230 °C and 2.16 kg). Both properties are important because the low processing temperature minimizes the heat load on the polymeric mould, while the high melt flow rate helps to reduce the required injection (filling) pressure.

The injection moulding tests were carried out with an Arburg Allrounder Advance 270 S 400 − 170 machine (ARBURG GmbH, Germany), equipped with a 30 mm diameter screw. The applied injection moulding parameter set is presented in Table 3. Minimizing the injection rate is important, as it reduces the maximum injection pressure at switchover, which also lowers the required clamping force. With polymeric mould inserts, a longer holding time is necessary due to two key factors. First, polymeric inserts have a thermal conductivity approximately two orders of magnitude lower than that of steel moulds. This difference leads to slower gate freeze and melt solidification. Second, the slower cooling rate amplifies product shrinkage, which can be compensated for by increasing the holding time. Furthermore, a prolonged delay time between cycles is essential to prevent the overheating and early failure of the polymeric inserts.

Initially, we injection moulded 10 cycles with a constant holding pressure of 75 bar to assess the stability and reproducibility of the process. Once stable production was confirmed with this parameter set, holding pressure was increased in increments of 25 bar in every second cycle. We varied holding pressure from 50 bar up to 300 bar to evaluate the durability of the mould inserts. Following this, a further 10 cycles were injection moulded with a holding pressure of 125 bar, another 10 cycles with 175 bar, and a final set of 10 cycles with 225 bar.

3D scanning of the mould inserts

The dimensional accuracy of the mould inserts was evaluated with a GOM ATOS Core 5 M optical 3D scanner (Carl Zeiss GOM Metrology GmbH, Germany). The scanner provides a theoretical resolution of 0.01 mm. We scanned the polymeric mould inserts as-printed to measure their baseline geometry. The inserts were then also scanned after post-curing for its effect on dimensional stability. We finally scanned the inserts a third time after the injection moulding series to quantify residual deformations after use.

Results and discussion

Specimen testing

Dynamic mechanical analysis

We performed dynamic mechanical analysis in temperature sweep mode and measured the storage modulus (E’) and loss factor (tanδ) (Fig. 2) to characterise the temperature dependence of the stiffness and the state changes of the two materials. The storage modulus at room temperature was 4055 MPa for the Rigid10K resin while it was 2960 MPa for the High Temp resin. It is because Rigid10K is a fibre-reinforced resin, while the High Temp resin does not contain additional reinforcement. The difference between the two materials gradually diminishes as the temperature increases and the two materials show the same storage modulus (1029 MPa) at 123 °C. From that temperature, the High Temp resin exhibited significantly higher storage modulus, while the Rigid10K resin had minimal stiffness, especially above 150 °C. It is because the matrix material of Rigid10K is considerably less heat-resistant than the High Temp resin. The loss factor–temperature curves of the two materials are fundamentally different. The High Temp resin showed two slight local maxima: one 100 °C and one at 219 °C but no drastic changes can be observed on the curves. On the other hand, the Rigid10K resin shows one sharp peak at 140 °C indicating the well-defined glass transition temperature range of the material. Based on these results, the Rigid10K resin has higher stiffness below 123 °C but above that it enters its glass transition temperature range and the advantage in stiffness diminishes. For extreme high temperature applications, the High Temp resin is more suitable.

Creep tests

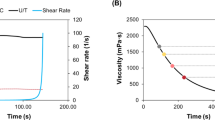

Creep is a major contributor to the deformation of polymeric injection moulds, particularly under elevated operating temperatures. The creep behaviour of polymeric materials was characterized by dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) in creep time–temperature superposition (TTS) mode. Creep compliance (J) is defined as the ratio of time-dependent flexural strain (εfl.) and the applied constant flexural stress (σ₀), as expressed by Eq. (1). An increase in creep compliance indicates a higher tendency for time-dependent deformation under constant load.

From room temperature to 80 °C, the creep compliance of Rigid10K is less than half that of the High Temp resin. It means that at this temperature range, the Rigid10K material suffers significantly lower viscoelastic deformation. It is caused by the fibre reinforcement of the resin and the fact that the matrix material is well below its glass transition temperature. In the 90–95 °C temperature range, the difference in creep compliance between the two materials gradually diminishes and they show almost the same creep compliance. In this temperature range, the matrix of the Rigid10K material gradually enters the glass transition range. At 120 °C, the Rigid10K resin shows excessive creep deformation (characterised by the large creep compliance). This temperature is well in the glass transition range of the Rigid10K matrix material. It indicates that Rigid10K is not ideal for extremely high temperature applications where the parts are subjected to mechanical load for a longer time (Fig. 3).

The accuracy of printing mould inserts and their dimensional stability after heat treatment

Dimensional stability is an essential requirement for injection moulds. The inserts were 3D scanned after printing and after thermal treatment. Figure 4 shows the scanning results of the HT resin insert as-printed and after thermal post-curing. The as-printed state shows direction-dependent shrinkage. The maximal dimensional deviations are around + 0.30 mm at the back of the insert, while they are − 0.50 mm and + 0.41 mm at the two perpendicular sides of the insert. Post-curing had a beneficial effect on the dimensional accuracy of the mould insert. The dimensional deviations at the back of the mould insert were reduced by an average of 0.15 mm, meaning that post-curing can reduce the warpage-induced bending of the printed part. Post-curing did not have a fundamental effect on the dimensions in the two other perpendicular directions. The dimensional accuracy enhancing effect of post-curing improves the applicability of injection mould inserts printed by vat photopolymerisation.

Figure 5 presents the 3D scanned images of the Rigid10K insert as-printed and after post-curing. The dimensional stability of the Rigid10K insert also improved due to post-curing, which can be clearly seen at the back of the injection mould insert. The shrinkage of the Rigid10K material is not as direction-dependent as that of the High Temp insert. However, the remnants of the support structure can be clearly seen at the back of the moving-side insert, while it was negligible in the case of the High Temp insert.

Injection moulding tests

Injection moulding with increasing holding pressure

Following the thermal post-curing and scanning of the inserts, we conducted injection moulding tests. During these tests, the operational deformations of the injection mould inserts were measured with strain gauges. Initially, 10 cycles were injection moulded with a holding pressure of 75 bar. Subsequently, the holding pressure was increased in 25-bar increments from 50 to 300 bar, with two cycles injection moulded with each pressure. The default clamping force was 5 tons, but it was increased when excessive flash occurred due to partial mould opening, which typically occurred with holding pressures of 275 and 300 bar.

The shapes of the strain curves are similar for both materials. The curves start with a small drop at mould closing as the inserts are compressed by the applied clamping force. After that, the strains increase fast in the filling phase (~ 1.2 s). The fast increase in strain is caused by the melt, which is injected at high pressure and speed. After the switchover point from filling to holding, the curves diverge depending on the applied holding pressure. In the holding phase, the screw of the injection moulding machine is regulated to maintain a constant holding pressure. At lower holding pressures (50–150 bar), strain does not increase further in the holding phase because there is only a small amount of additional material injected into the cavity. This small amount of additional injected melt can barely compensate for the product shrinkage, which causes the lower strains of the mould insert. On the other hand, at higher holding pressures (175–300 bar) the amount of additional injected melt is considerably higher. At these holding pressures, strain increases even in the holding phase and the rise is proportional to the applied holding pressure. Maximum deformation is reached in the holding phase and a higher holding pressure results in maximum deformation delayed in time. In the late holding phase and the residual cooling time, the product cools down and transfers heat to the injection mould inserts. This heat causes three simultaneous phenomena: thermal expansion, creep and decrease in stiffness. These effects determine the shape of the strain curves until mould opening. At mould opening, the clamping force is removed and the part is ejected, which causes a stepwise increase in the strain curves. After the part is ejected, the mould insert cools down and the strain decreases in the idle time between the cycles. The maximum deformations of the High Temp insert were 0.17%, 0.23% and 0.29% at 250, 275 and 300 bar holding pressures, respectively. On the other hand, maximum deformations of the Rigid10K insert at these holding pressures were 0.02%, 0.03% and 0.05%, respectively. The results indicate nearly an order of magnitude difference in the maximum deformations which is a substantial difference. This difference is caused by the higher stiffness and better creep resistance of the Rigid10K resin in the lower temperature range where the mould inserts operate. These maximum deformations prove that the Rigid10K resin is considerably better for prototype injection mould making in this heat and pressure load range (Fig. 6).

Repeatability tests with different holding pressures

Following the increasing holding pressure section, three series of repeatability tests were performed with different holding pressures. These holding pressures were the following:125 bar, 175 bar and 225 bar. Ten cycles were injection moulded with each holding pressure. Figure 7 presents the strain curves measured with a constant holding pressure of 175 bar. The maximum deformation of the High Temp insert was 0.04%, which occurred in the middle of the holding phase, while the maximum deformation of the Rigid10K insert was only 0.02% which happened at the end of the filling phase. If the maximal deformation occurs right at the end of the filling phase, it indicates that the elastic deformation component of the polymer is the dominant. However, when the maximal deformation occurs in the holding phase, it indicates that the viscoelastic deformation and creep are dominant.

Figure 8 presents the operational strains of the two mould inserts when a constant 225 bar holding pressure was applied. The maximum strain of the High Temp insert varied minimally between 0.17% and 0.18% and it occurred in the middle of the holding phase. On the other hand, the maximum strain of the Rigid10K insert was 0.02% and it was measured at the end of the filling phase. The difference in the maximum strain can be explained with the results of DMA. The Rigid10K material showed considerably higher stiffness and significantly lower creep compliance in the lower temperature region, where the mould inserts operate. The operational strain results of the injection moulding tests are in accordance with the findings of the material tests.

Both materials showed minimal scatter in the strain curves, which means that both inserts can be used in a stable and reproducible injection moulding process.

Cavity pressure acting on the mould inserts

The cavity pressure was also measured at the end of the flow length. Figure 9 presents the cavity pressure with constant holding pressure of 175 bar, measured in the cavity of the High Temp and the Rigid10K inserts. The first maximum on the cavity pressure curves corresponds to the end of volumetric filling and the compression of the melt in an early section of the holding phase. This first maximum typically occurs between 3 and 4 s. After that, the cavity pressure slowly begins to decrease until approximately 12 s in the case of the High Temp insert and 20 s in the case of the Rigid10K insert. Then, both cavity pressure curves slowly increase again. It is because the heat is transferred from the melt to the cavity insert, which results in the thermal expansion of the mould inserts. Thermal expansion compresses the cavity volume, which causes an increase in cavity pressure. The injection moulding parameters and the injection moulded material were identical and the cavity volume of the mould inserts is close to nominal as was already proved by 3D scanning. Therefore, the differences in the cavity pressure curves from approximately 11 s can be explained by the considerable difference in the coefficients of thermal expansion. The coefficient of thermal expansion of the High Temp resin is 87.5 μm/(m∙°C) while it is 47 μm/(m∙°C) for the Rigid10K material37. The more intense thermal expansion of the High Temp material causes the increase in cavity pressure in the residual cooling phase. As the clamping force is removed and the part is ejected, the compressive effect of the injection moulded product disappears and cavity pressure drops. The standard deviation of the cavity pressure curves is minimal in both cases, which means a stable and reproducible injection moulding process.

Temperature of the mould inserts

The volumetric temperature of the mould inserts was also measured at their back (Fig. 10). Both inserts operated in a nearly identical volumetric temperature range (25–54 °C for the High Temp and 25–56 °C for the Rigid10K insert). The cyclic variation of temperature is more significant in the case of the Rigid10K insert because its thermal conductivity is more than double that of the High Temp resin. This increase in thermal conductivity is caused by glass fibre content and the different formulation of the resin.

The dimensional accuracy of mould inserts after injection moulding

The dimensional accuracy of the mould inserts was checked after the injection moulding tests. Figure 11 shows the 3D scanned images. Only minimal residual deformation can observed on the cavity surfaces of the two mould inserts. However, the High Temp insert cracked in the 70th cycle, when the holding pressure was 225 bar. Figure 12 presents the cracked High Temp insert after the injection moulding series. It was caused by the fatigue induced by the cyclic thermomechanical load. Alongside the crack, there was considerable pitting on the cavity surface as small pieces of material broke from there. The chipping of the cavity edges were also clearly visible. The Rigid10K insert did not show residual deformation or observable tool wear. It is because the glass fibre content of the resin increases its wear resistance. It is therefore recommended to primarily use the Rigid10K resin for rapid tooling tasks instead of the High Temp resin.

Conclusions

-

Two high-performance photopolymers were compared which can be processed by vat photopolymerisation. The High Temp resin and the Rigid10K resin were compared by dynamic mechanical analysis in temperature sweep and creep test mode. The storage modulus of Rigid10K at room temperature was 4055 MPa while the High Temp resin showed 2960 MPa at that temperature. As the temperature increased, the difference in the storage modulus gradually diminished until 123 °C was reached. Above that temperature, the High Temp resin showed higher modulus. Creep properties had a similar tendency. The creep compliance of Rigid10K was considerably lower from room temperature to 90 °C. Above that temperature (in the 95–170 °C range), the Rigid10K resin suffered excessive creep deformation, while the High Temp resin showed only moderate creep.

-

Two injection mould inserts were printed from the two resins. The inserts were 3D scanned after printing to check the dimensional stability of the AM process. The cavity surfaces of both inserts showed nearly nominal dimensions while their sides suffered considerable deformation. The inserts were then subjected to post-curing with a combination of heat and UV light. The applied post-curing reduced the warpage of both inserts, enhancing their dimensional accuracy. This is desirable for prototype injection mould making.

-

Injection moulding tests were carried out after the 3D scanning of the post-cured injection mould inserts. The operational strains of the High Temp insert were 0.17%, 0.23% and 0.29% with holding pressures of 250, 275 and 300 bar, respectively. The Rigid10K insert only showed 0.02%, 0.03% and 0.05% deformations with those holding pressures. The lower deformations of the Rigid10K insert indicate its better applicability in low-volume injection mould making. After the increasing holding pressure section, the inserts were subjected to constant holding pressures of 125, 175 and 225 bar for 10 cycles each. The High Temp insert showed higher deformation compared to the Rigid10K insert in all cases.

-

Both the Rigid10K and the High Temp resins can be used in prototype injection mould making. The Rigid10K resin shows lower creep compliance and higher stiffness compared to the High Temp resin, which makes it more suitable for injection mould making tasks. Overall, vat photopolymerisation can be an appropriate additive manufacturing process to print low-volume moulds. The finding that vat photopolymerisation is a suitable additive technology for prototype injection mould making is a definite novelty. The dimensional accuracy of the printing process is still inferior compared to material jetting, but a further development of the printers, especially digital light processing (DLP) can eliminate these shortcomings. Vat photopolymerisation also allows the printing of special, high-performance resins (fibre-reinforced or metal powder-filled) which cannot be processed by MJ. This way, the application of additively manufactured injection moulds can be enhanced.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. If you would like to receive the research data, please write an email to [krizsmasz@pt.bme.hu] (mailto: krizsmasz@pt.bme.hu).

References

Srivastava, M., Rathee, S., Patel, V., Kumar, A. & Koppad, P. G. A review of various materials for additive manufacturing: recent trends and processing issues. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 21, 2612–2641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.10.015 (2022).

Güney, A. & Kernebeck, L. Grijpma: 3D printing of porous poly(ε-caprolactone)-poly(trimethylene carbonate)-poly(ε-caprolactone) triblock copolymers and nano-apatite composite structures. EXPRESS Polym. Lett. 18 (4), 371–390. https://doi.org/10.3144/expresspolymlett.2024.26 (2024).

Ficzere, P. Surface anisotropy on 3D printed parts. Period Polytech. Mech. Eng. 68 (3), 272–277. https://doi.org/10.3311/PPme.37770 (2024).

Krizsma Sz, G., Suplicz, A. & Gere, D. Customised production of injection moulded parts from recycled materials using rapid tooling approach and coupled injection moulding-thermal and mechanical simulation. Results Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.105272 (2025).

Krizsma Sz, G. & Suplicz, A. Comprehensive in-mould state monitoring of material jetting additively manufactured and machined aluminium injection moulds. J. Manuf. Process. 84, 1298–1309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2022.10.070 (2022).

Bagalkot, A., Pons, D., Clucas, D. & Symons, D. A methodology for setting the injection moulding process parameters for polymer rapid tooling inserts. Rapid Prototyp. J. 25 (9), 1493–1505. https://doi.org/10.1108/RPJ-10-2017-0217 (2017).

Giorleo, L., Stampone, B. & Trotta, G. Micro injection moulding process with high-temperature resistance resin insert produced with material jetting technology: effect of part orientation. Addit. Manuf. 56, 102947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.102947 (2022).

Bagalkot, A., Pons, D., Symons, D. & Clucas, D. Categorization of failures in polymer rapid tools used for injection molding. Processes 7 (1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr7010017 (2019).

Stampone, B., Giorleo, L. & Trotta, G. The behaviour of micro-injection moulding inserts produced with material jetting technology. Compos. B: Eng. 288, 111913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2024.111913 (2025).

Gülçür, M. et al. X-ray computed tomography for predictive quality assessment, 3D visualisation of micro-injection mouldings and soft-tool deformation. Mater. Des. 227, 111741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2023.111741 (2023).

Stampone, B. et al. Rapid tooling for microinjection moulding of Proof-of-Concept microfluidic device: resin insert capability and preliminary validation. Appl. Sci. 14 (8), 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14083157 (2024).

Stampone, B., Ravelli, M., Giorleo, L. & Trotta, G. Thermal behaviour of resin inserts for micro injection moulding: a FEM analysis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 217, 1360–1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.12.334 (2022).

Gülçür, M., Isakov, D., Charmet, J. & Gibbons, G. J. Investigating demoulding characteristics of material jetted rapid mould inserts for microinjection moulding using inline monitoring and surface metrology. Rapid Prototyp. J. 30 (7), 1322–1336. https://doi.org/10.1108/RPJ-03-2024-0129 (2024).

Zhang, F. et al. The recent development of vat photopolymerization: A review. Addit. Manuf. 48, 102423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2021.102423 (2021). Part B.

Rashid, A. A., Ahmed, W., Khalid, M. Y. & Koç, M. Vat photopolymerization of polymers and polymer composites: processes and applications. Addit. Manuf. 47, 102279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2021.102279 (2021).

Zhao, L. et al. Developing the optimized control scheme for digital light processing 3D printing by combining numerical simulation and machine learning-guided temperature prediction. J. Manuf. Process. 132, 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2024.10.049 (2024).

Choi, J. W. & Ha, C. W. Strategy for minimizing deformation of DLP 3D printed parts using sub-build plate. J. Manuf. Process. 131, 2340–2349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2024.10.016 (2024).

Davoudinejad, A. et al. Additive manufacturing with vat polymerization method for precision polymer micro components production. Procedia CIRP. 75, 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2018.04.049 (2018).

Kowsari, K. et al. Photopolymer formulation to minimize feature size, surface roughness, and stair-stepping in digital light processing-based three-dimensional printing. Addit. Manuf. 24, 627–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2018.10.037 (2018).

Mostafa, K. G., Arshad, M., Ullah, A., Nobes, D. S. & Qureshi, A. J. Concurrent modelling and experimental investigation of material properties and geometries produced by projection microstereolithography. Polymers 12 (3), 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12030506 (2020).

Stansbury, J. W. Idacavage: 3D printing with polymers: challenges among expanding options and opportunities. Dent. Mater. 32 (1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2015.09.018 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Theoretical prediction and experimental validation of the digital light processing (DLP) working curve for photocurable materials. Addit. Manuf. 37, 101716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2020.101716 (2021).

Westbeek, S., Remmers, J. J. C., van Dommelen, J. A. W., Maalderink, H. H. & Geers, M. G. D. Prediction of the deformed geometry of vat photo-polymerized components using a multi-physical modeling framework. Addit. Manuf. 40, 101922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2021.101922 (2021).

Yang, Y., Li, L. & Zhao, J. Mechanical property modeling of photosensitive liquid resin in stereolithography additive manufacturing: bridging degree of cure with tensile strength and hardness. Mater. Des. 162, 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2018.12.009 (2019).

Wu, D., Zhao, Z., Zhang, Q., Jerry Qi, H. & Fang, D. Mechanics of shape distortion of DLP 3D printed structures during UV post-curing. Soft Matter. 15, 6151–6159. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9SM00725C (2019).

Guven, E., Karpat, Y. & Cakmakci, M. Improving the dimensional accuracy of micro parts 3D printed with projection-based continuous vat photopolymerization using a model-based grayscale optimization method. Addit. Manuf. 57, 102954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.102954 (2022).

Dizon, J. R. C., Espera, A. H., Chen, Q. & Advincula, R. C. Mechanical characterization of 3D-printed polymers. Addit. Manuf. 20, 44–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2017.12.002 (2018).

Andjela, L. et al. A review on vat photopolymerization 3D-printing processes for dental application. Dent. Mater. 38 (11), e284–e296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2022.09.005 (2022).

Melchels, F. P. W., Feijen, J. & Grijpma, D. W. A review on stereolithography and its applications in biomedical engineering. Biomaterials 31 (24), 6121–6130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.050 (2010).

Chartrain, N. A., Williams, C. B. & Whittington, A. R. A review on fabricating tissue scaffolds using vat photopolymerization. Acta Biomater. 74, 90–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2018.05.010 (2018).

Xu, X. et al. Vat photopolymerization 3D printing for advanced drug delivery and medical device applications. J. Control Release. 329, 743–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.10.008 (2021).

Zhao, W. et al. Vat photopolymerization 3D printing of advanced soft sensors and actuators: from architecture to function. Adv. Mater. Technol. 6, 2001218. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202001218 (2021).

Davoudinejad, A. et al. Experimental investigation and thermo-mechanical modelling for tool life evaluation of photopolymer additively manufactured mould inserts in different injection moulding conditions. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Tech. 102, 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-018-3163-7 (2019).

Davoudinejad, A., Khosravani, M. R., Pedersen, D. B. & Tosello, G. Influence of thermal ageing on the fracture and lifetime of additively manufactured mold inserts. Eng. Fail. Anal. 115, 104694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2020.104694 (2020).

Form Wash and Form & Wash, L. time settings (https://support.formlabs.com/s/article/Form-Wash-Time-Settings?language=en_US) (date of download: 2025.07.14.).

Form Cure time. and temperature settings (https://support.formlabs.com/s/article/Form-Cure-Time-and-Temperature-Settings?language=en_US) (date of download: 2025.07.14.).

Thermal properties of selected Formlabs SLA resins. (https://support.formlabs.com/s/article/Thermal-properties-of-selected-Formlabs-SLA-resins?language=en_US) (date of download: 2025.07.14.).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank ARBURG HUNGÁRIA KFT. for the ARBURG Allrounder injection moulding machine, and TOOL-TEMP HUNGÁRIA KFT., LENZKES GMBH and PIOVAN HUNGARY KFT. for the accessories.

Funding

Project no. RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00009, titled National Laboratory for Renewable Energy has been implemented with the support provided by the Recovery and Resilience Facility of the European Union within the framework of Programme Széchenyi Plan Plus. This research was funded by the Horizon Europe Framework Programme and the call HORIZON-WIDERA-2021-ACCESS-03, under the grant agreement for project 101079051 – IPPT_TWINN. Project no. TKP-6-6/PALY-2021 has been implemented with the support provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the TKP2021-NVA funding scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed to conceptualization and methodology equally. Investigation, visualization, data curation and writing the original draft were performed by S. K. Formal analysis, review and editing were performed by A. S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krizsma, S., Suplicz, A. Applying high-performance resins in stereolitography printing to produce prototype injection moulds. Sci Rep 15, 39652 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23249-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23249-8