Abstract

The blood pressure (BP) estimation plays a crucial role in assessing cardiovascular health and preventing related complications. One of the early warning indicators for heart disorders is elevated blood pressure. Thus, monitoring of blood pressure continuously is needed. The study aims to develop and validate a reliable deep learning-based approach for blood pressure estimation using photoplethysmography from the publicly available database MIMIC-II. The continuous wavelet transform (CWT) was used to transform the photoplethysmogram (PPG) signals into scalograms, which were then input into six different deep learning models: VGG16, ResNet50, InceptionV3, NASNetLarge, InceptionResNetV2 and ConvNeXtTiny. The obtained deep features from each one of these models were employed to estimate BP values using random forest. The proposed approach uses a unique transfer learning framework that integrates deep feature extraction from scalograms with random forest regression, providing a new pathway for blood pressure estimation. The models were assessed using mean absolute error (MAE) and standard deviation (SD) in estimating the systolic and diastolic blood pressure values. Out of six models, ConvNeXtTiny and VGG16 showed good performance. ConvNeXtTiny achieved mean absolute error of 2.95 mmHg and standard deviation of 4.11 mmHg for systolic blood pressure and mean absolute error of 1.66 mmHg and standard deviation of 2.60 mmHg for diastolic blood pressure. The achieved result complies with the clinical standards set by Advancement of Medical Instrumentation Standard (AAMI) and the British Hypertension Society standard (BHS). This can enhance cardiovascular health monitoring with continuous, non-invasive and reliable blood pressure measurement, assisting in early detection of the disease. The suggested method shows that reliable blood pressure estimation from photoplethysmography signals is possible with the use of deep learning and transfer learning. Above all, ConvNeXtTiny offers a dependable method for continuous blood pressure monitoring that satisfies clinical requirements and may help in the early identification of cardiovascular problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Blood Pressure (BP) levels that are abnormal can have lethal consequences, increase the risk of Cardiovascular Disease (CVD), and damage organs. Heart attacks, strokes, renal failure, and other conditions can all be brought on by chronic hypertension1. Hypertension constitutes a major risk factor for CVD, which continues to be the primary cause of mortality globally2. In 2019, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), CVD accounted for 17.9 million deaths, representing 31.4% of total fatalities worldwide including countries such as United Kingdom and Northern Ireland registered them as second leading cause of fatalities with 28.7% and 23.4% of total deaths respectively3. The CVD mortality has risen consistently, with figures increasing from 14.2 million in 2000 to 15.9 million in 2010, and reaching 17.9 million in 2019 (Fig. 1a). The WHO also recorded that across most European countries, the Russian Federation, India, China, and the United States, CVDs have consistently remained the leading cause of fatality with 28.1% of total (Fig. 1b).

With the rising trend, it is essential to continuously monitor BP to detect, control, and treat hemodynamic abnormalities and CVD in their early stages4. Thus, this motivates to develop a reliable and non-invasive deep learning (DL) based framework for reliable BP estimation using PPG signals, enabling timely monitoring, early detection of cardiovascular abnormalities and enhance patient care. Blood pressure can be intermittently or continuously monitored. Sphygmomanometry and oscillometry are two examples of intermittent approaches; the former uses Korotkoff noises, while the latter provides automated, hands-free measurements. However, intermittent approaches have drawbacks such as the need for training, quiet environments, and time lag between readings5,6.

Continuous monitoring techniques include volume clamp, invasive arterial BP estimation, arterial tonometry, electrocardiogram (ECG), and photoplethysmography (PPG). Invasive methods are commonly used in healthcare but are limited to in-house patients7. The common method for ECG recording is done by using electrodes as explained by Satter et al.8. It is non-invasive and reliable for cardiovascular diagnosis but not feasible for continuous monitoring for non-patients. PPG uses optical approaches to measure variations in blood volume without the need for intrusive procedures9. PPG can be captured in transmissive or reflective modes and has applications in clinical and mobile settings10,11. Smartwatches and wearable technologies can benefit from its real-time monitoring capabilities, which are especially helpful for athletes, exercisers, and the elderly. The study aims to use advanced DL techniques by employing a unique transfer learning framework with scalogram-based BP estimation.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: The second section elaborates on the review of literature over the past years, highlighting their evolution from traditional approaches to advanced Machine Learning (ML) and DL methods. Subsequently, the methodology and materials adopted for BP estimation are explained including dataset, windowing, and scalogram generation, continuous wavelet transform (CWT), and pre-trained CNNs. Section Hardware and software specifications encompasses discussions about the paper’s outcomes and performance comparisons with various pre-trained CNN models.

Related work

From statistics to deep learning techniques, PPG signal analysis has changed over time. For blood pressure estimation, a variety of parameters have been used, including Pulse Transit Time (PTT)12, Pulse Wave Velocity (PWV)13,14 etc. A measure of arterial stiffness is PWV, while PTT counts the time an arterial wave travels between two arterial sites. Multiple sensors are needed for statistical methods, which are impacted by variables such as age, weight, etc.15,16. PWA uses linear regressions to assess PPG waveform morphological aspects to predict blood pressure14,17. Because of their potential, PTT and PWV approaches are still being investigated; nevertheless, one of their limitations is that they require two sensors that can precisely measure the distance between artery sites.

ML approaches, such as Random Forests (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) have been used to estimate BP using constructed features generated from PPG data18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Feature engineering can be time-consuming and may not guarantee accuracy in PPG signal analysis18,25,26,27,28,29,30. The optimum features are selected by incorporating various correlation techniques. Alternatively, deep neural networks can learn characteristics or features directly from PPG signals, eliminating the necessity of manually crafting features31,32,33. Due to the ability of deep learning approaches which can automatically extract high dimensional features from PPG signals, it has received attention. Researchers have used auto-encoders, multi-layered neural networks, and deep neural network models to estimate BP, achieving improved results compared to traditional methods34,35,36,37. The U-Net architecture has been applied for image segmentation38,39, leading to its utilization for PPG signal mining. However, existing models still have limitations, such as information redundancy and gradient vanishing. Researchers have made improvements by incorporating attention modules, residual modules, and enhanced U-Net models40,41. These optimizations have demonstrated success in image segmentation but are still in the early stages of application of continuous blood pressure monitoring using physiological signals42,43,44,45,46. Although several deep learning algorithms have been investigated, they frequently need significant computer resources and memory.

Recent research in transfer learning and domain adaption highlights the growing focus on improving model efficiency and adaptability across various tasks and domains. A comprehensive overview of transfer learning in deep reinforcement learning is given by Zhuang et al.47, while Wang et al.48 investigate source free unsupervised domain adaptation, which enables models to adapt without having access to the source data. Zhang et al.49 focus on learning from multi sources for domain adaptation, and Luo et al.50 address the challenge of handling inaccurate label spaces in multi source domain adaptation. These techniques could be used for BP estimation using PPG signals as they help models adapt to various populations and sensor types, reduce reliability on large, labelled datasets, and maintain performance despite label noise. Deep neural networks have high computational and memory demands, but pretrained CNNs enhanced through transfer learning, reduce these requirements and improve efficiency. This approach decreases the need for extensive labelled data and enables adaptation to new tasks with lower resources consumption.

Pretrained CNNs have been used in clinical areas like brain tumour detection from MRI scans, histopathology image classification, and brain image analysis51,52,53. These successes suggest that pretrained CNNs, which have been effectively used in prior studies for BP estimation, could be valuable for this task, thereby allowing us to take advantage of their established strengths, improving both the efficiency and accuracy of the system while also making it more resource efficient in BP estimation. The following are the key research gaps identified after rigorous literature survey:

-

Dependency on sensor placement: The measurement process is difficult with the methods such as PTT and PWV which requires two or more sensors.

-

Hand crafted feature engineering: The identification of hand-crafted features by exhaustive search and optimizing it requires time and considerable effort.

-

Computational complexities: The deep learning models automatically extract features, but it requires high computational and memory.

These gaps underline the need for insightful methods like transfer learning to overcome the limitations by reducing memory and high computational requirements.

In order to apply transfer learning to time series inputs, PPG signals can be transformed into images by using visibility graphs54 but preserving a relevant temporal and frequency information remains a challenging task. On the other hand, scalograms that represents time–frequency information at different scales, offers a more simple and straightforward way to preserve relevant time and frequency information, unlike visibility graphs which involve identifying complex points, checking for visibility and creating edges and nodes. The utilization of scalograms has been done in epilepsy diagnosis from EEG signals55 has prompted the application of scalograms in estimating BP values from PPG signals. Scalograms retain both time and frequency details of PPG signals, making them valuable for BP regression tasks. Though, a previous study has demonstrated the effectiveness of utilizing scalograms for BP classification using models such as pretrained CNN models56,57,58 and deep CNN architectures59,60 and evaluated the performance of their model using accuracy metric. These studies have primarily focused on blood pressure classification based on hypertension stages, laying a foundation that can be further extended to BP regression. Thus, it can be built upon these approaches to estimate continuous BP values and evaluate them against clinical standards such as the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) and the British Hypertension Society (BHS) guidelines.

In one of the research works21, time and frequency features were separately extracted for BP estimation wherein frequency features were obtained by taking Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Time-varying autoregressive (TV-AR) methods have been used for estimating heart rate variability61. Unlike scalograms that provides direct time–frequency representation, TV-AR captures spectral changes over time by varying parameters making it tedious and complex to implement effectively, and thus resolution is affected. The Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) has been used in PPG based blood pressure estimation62 and obtained accuracy by classifying it as normal or Hypertension. It could be explored in future studies for BP regression task from PPG signals as it provides time–frequency information. However, the CWT has been used in this study. Due its ability to adapt to different frequency components at varying time points, offers a promising alternative for capturing the nuanced dynamics of PPG signals.

Based on the existing literature, the utilization of scalograms for blood pressure estimation has been explored in a few studies, where deep learning models such as CNN-SVR, compound multichannel CNN, and image encoding and fusion BP techniques have been applied to perform BP regression. Maharajan et al.63 assessed performance using RMSE, while Lu et al.64 employed Mean Error and standard deviation. Liu et al.65 utilized custom image fusion methods instead of scalograms and evaluated MAE. Their study incorporated BHS-based evaluation and achieved Grade A, and further exploration of standard deviation assessment can enhance alignment with AAMI clinical standards, presenting an opportunity for advancement.

To address the challenge of blood pressure estimation, this algorithm offers a data driven, end to end solution using PPG signals. It employs pretrained models, which provide low computational cost. Additionally, to meet clinical standards, the approach emphasizes scalogram based preprocessing, yielding deep features and eliminating the need for manual feature engineering. The following are the primary contributions of the current study:

-

The application of continuous wavelet transform using Morlet wavelets to generate scalograms, effectively captures both time and frequency information from PPG signals and estimates BP accurately. Morlet wavelet has the capability of analysing oscillatory signals such as PPG, as its kernel consist of complex exponential wrapped in gaussian envelop.

-

Instead of training models from scratch, the pretrained CNN models are employed to extract deep features from generated scalograms, minimizing the computational cost.

-

The random forest was used to estimate systolic and diastolic BP values in compliance with clinical standards, due to its robustness and ability to handle complex data patterns as compare to other machine learning techniques.

-

Unlike previous studies, the BP estimation was validated using both AAMI and BHS standards making it reliable in health care applications.

The next section gives the detailed description about the methodology and materials used in the paper starting from dataset used, PPG segmentation, obtaining scalograms, pretrained models for deep features and random forest to estimate BP values.

Methodology and materials description

The proposed model for continuous and non-invasive estimation of BP pressure using PPG signals is depicted below in Fig. 2.

The Fig. 2 gives the detailed information about the data which is collected from the “Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care” (MIMIC II) database, a valuable source of medical information. Then, the collected PPG data is pre-processed and subsequently, a CWT is employed to the preprocessed data, resulting in the generation of two-dimensional representations known as scalograms. Furthermore, the VGG16, ResNet50, InceptionV3, NASNetLarge, InceptionResNetV2, and ConvNeXtTiny are used to capture the deep features, i.e., characteristics from Scalograms. Finally, the Random Forest model utilizes the extracted features in BP estimation.

The significance of this research lies in the use of scalograms for blood pressure estimation based on clinical standard evaluation. This approach sets itself apart from existing methods by transforming PPG signals into scalograms with a focus on BP regression and evaluating performance based on clinical standards. The proposed model achieves MAE and SD below 5 mmHg and 8 mmHg respectively, while also attaining Grade A classification under BHS.

The RF model was chosen for its effectiveness in managing complex feature sets derived from scalograms. A prior study66 compared machine learning algorithms for BP estimation from HCFs and showed that Random Forest outperformed other methods with MAE of 4.45 mmHg while adhering to AAMI standards. Its ensemble learning techniques aggregates predictions from several decision trees, reducing variance and preventing overfitting making it a good choice for handling the varied feature outputs from different pretrained CNNs. It provides feature importance rankings and helping in identifying the most relevant features from the scalograms.

A key aspect of integration of scalograms with pretrained CNN models, combined with a Random Forest (RF) algorithm. The RF model is tuned with number of estimators set to 100. This unique combination uses the strengths of pretrained models that captures intricate pattern in PPG signals while incorporating the robustness of RF for BP regression. The proposed model aims to enhance the generalizability and reliability of BP estimation.

These pretrained models were selected to address a range of architectural challenges, from the classic VGG16 to more recent designs like ConvNeXtTiny. This consistent representation enables a direct assessment of each model’s ability to handle the time–frequency information of the PPG data. The RF model further refines these extracted concrete features, enhancing the stability of BP predictions.

This structured methodology not only improves performance metrics but also reinforces the clinical relevance and real-world applicability of the proposed model, making it well-suited for practical deployment in wearable and healthcare applications.

Dataset

The dataset used was obtained from the University of California Irvine (UCI) Machine Learning Repository67, which is a subgroup of the MIMIC-II waveform database68. It is which is made available online by the PhysioNet organization. The UCI dataset, basically collected from Physionet database, consist of 12,000 records that has synchronized measurements of PPG, arterial blood pressure (ABP), and ECG, all sampled at a frequency (fs) of 125 Hz. The ABP measurements were measured invasively which is widely acknowledged as the gold standard for BP assessment69. Hence, the ABP waveforms available in MIMIC II database serve as the reference values for blood pressure in the research. The MIMIC II offers a well-established collection of waveform data that has been widely used in research studies related to healthcare analytics and monitoring. In this work, ABP and PPG waveforms were utilized for non-invasive blood pressure measurement and the details are listed in Table 1.

The MIMIC II dataset was used from where the PPG and ECG signals were loaded and extracted which is shown in Algorithm 1.

Following the comprehensive exploration of the dataset, the next stage of this methodology is to uproot the temporal and spectral dynamics encompassed in the PPG signals through windowing and scalogram generation.

Windowing and scalogram generation

The PPG and ABP data were windowed and scalograms were generated which is shown in Table 2. By segmenting the records into non-overlapping segments and applying the Morlet transform to PPG signals, converts it into 2D array called as scalograms.

The scalograms effectively represent the signals by retaining temporal and spectral characteristics. The following steps demonstrate the windowing of signals and generation of scalograms:

-

1.

The PPG and ABP was segmented into non-overlapping segments of 1000 samples (8 s) which is mentioned in Algorithm 2. The duration of each segment is calculated by using the Eq. (1).

$$Duration = \frac{No. \;of\;Samples}{{Sampling\;Frequency\;\left( {f_{s} } \right)}} = \frac{1000}{{125}} = 8\;{\text{seconds}}\;\;({\text{Since}}\;f_{s} = 125\;{\text{Hz}})$$(1) -

2.

The PPG data is filtered from 0.1 Hz to 8 Hz (Algorithm 3) as this range has significant information related to the DC component (baseline) and the AC component (blood volume changes due to heart pump). This range was determined by analyzing the Fourier Transform (FT) of PPG signals, detailed in Section Continuous wavelet transform and illustrated in Fig. 3, and is consistent with prior studies analyzing PPG signals for blood pressure estimation32,35,36,46. The diastolic and systolic BP reference values were obtained from segments of ABP waveforms, corresponding to each PPG segment (Algorithm 4).

-

3.

A Morlet transform, using a continuous wavelet transform with 128 scales, was applied to the PPG segments (Algorithm 5).

-

4.

Scalograms were generated, with each scalogram having a size of 128 by 1000.

-

5.

The scalograms were resized to dimensions suitable for the pre-trained CNN model, ensuring compatibility with its input requirements.

Thus, this process helps us to prepare the scalograms (two-dimensional data) which is applied as input for further analysis using the pre-trained CNN model, ensuring that the original time and frequency components of the PPG signals were preserved and utilized in the subsequent analysis.

Continuing on the use of the Morlet wavelet to obtain scalograms, the subsequent section discusses continuous wavelet transform. Moving forward to a greater understanding of CWT, its kinds, and its mathematical complexities, we hope to clarify how this transformative method aids in the preservation and application of crucial signal characteristics.

Continuous wavelet transform

Similar to the FT, the CWT calculates the similarity between an input signal and analyzing function using inner products.

The analytic function used by the CWT is wavelets, while the FT uses complex exponentials. The process involves comparing the input signal with various scales and positions of the shifted, compressed, or stretched wavelet versions to construct a two-variable function. This representation enlarges a one-dimensional signal into a two-dimensional function, capturing location and scale information, and offers a rich and detailed characterization. Depending upon the nature of the wavelet, the CWT can be complex-valued or real-valued. Equation 2 illustrates the CWT formula, which is dependent on the wavelet choice as well as scale (a) and position (b) factors.

where ψ(t) is the wavelet basis, * denotes the complex conjugate, and f(t) denotes the signal. The wavelet’s time point, scale, and shift are represented by the letters “t,” “a,” and “b,” respectively. The choice wavelet affects the continuous wavelet transform coefficients in addition to the scale and position values.

Typical wavelets that are employed in the continuous wavelet transform are the Poisson, Morlet, and Mexican Hat70. The wavelets have distinct qualities and are appropriate for various signal processing applications. Mathematically, it is defined as:

where H(t) is the Heaviside step function. It has 0 for t < 0 and 1 for t ≥ 0; c is a normalization constant; λ is the decay parameter; t is the time variable; n is a positive integer determining the degree of the polynomial term.

The Poisson wavelet is a popular tool for transient signal analysis, and it’s especially good at identifying and describing abrupt changes or discontinuities in time-series data.

The Ricker wavelet, often called the Mexican Hat wavelet, is another kind of wavelet used in analysis of signals. It is the second derivative of gaussian function, mathematically defined as follows:

where A is a normalization constant; t is the time variable; σ is a positive parameter determining the width of the wavelet.

It is widely applied in many different fields, including pattern recognition, image processing, and seismic research. It is particularly useful for identifying patterns like peaks and troughs in data. A complex sinusoid and a Gaussian window are combined in the Morlet wavelet, which makes it an excellent tool for oscillatory signal analysis. Based on the specific needs and attributes of the signal under analysis, one can choose from several wavelets, each with unique characteristics.

When the signal is convolved with the different Morlets, amplitude information is obtained at these specific frequencies. This analysis makes it easier to thoroughly explore the temporal and spectral content of the signal and provides insightful information about its time–frequency properties. Consequently, the Morlet wavelet’s capacity to analyze oscillatory signals and efficiently capture time and frequency information is one advantage of using it as an analyzing function60. Furthermore, convolution preserves temporal resolution, its Gaussian frequency pattern lowers misleading ripple effects, and its minimal calculations using the fast Fourier transform result in improved computing efficiency. This feature is particularly beneficial for the analysis physiological signals like electrocardiograms and photoplethysmograms.

The Morlet wavelet is mathematically defined as:

where j is the imaginary operator, f denotes frequency in Hz, and t indicates time in seconds.

The width of the Gaussian, denoted as σ, is defined as

The parameter ‘n’ establishes a trade-off between time and frequency precision, often termed as the “no. of cycles”. For neurophysiological data like EEG, and MEG, the parameter ‘n’ usually varies between 2 and 15 for frequencies ranging from 2 to 80 Hz71. Considering that PPG signals, similar to EEG, are physiological data with a range of frequencies from 0.5 Hz to 10 Hz and the mapping suggests that the value of ‘n’ can be selected as 3.

The Fourier transform of a PPG segment, shown in the Fig. 3, clearly indicates this frequency range. It has a DC Components indicating the baseline and the AC component indicating the volumetric changes of blood in the tissue due to Heartbeat.

The Fourier transform analysis (Fig. 3) indicates that the frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 8 Hz captures the most significant information in PPG signals. The DC component reflects the baseline level, while the AC component, primarily within this range, corresponds to the volumetric changes in blood due to cardiac activity, making it critical for accurate blood pressure estimation.

Further, the real and imaginary part of Morlet Wavelet for different values of cycles and scale factor is shown in Fig. 4.

With the positive aspects of the Morlet transform established, the utilization of a pre-trained CNN model has been explored as the next phase of this research. The next section focuses on the incorporation of the pre-trained CNN model to further enhance the analysis and estimation of blood pressure.

Convolutional neural networks: an overview

CNNs are a kind of DL model made especially for processing grid-like input. It represents a powerful paradigm in signal processing that uses hierarchical feature extraction to enhance model accuracy. In the proposed framework, CNNs are employed learn by itself and identify features within the input data, facilitating the understanding of complex signals. The key elements of CNN are discussed below.

Key elements of a CNN

-

1.

Convolutional Layers: These layers are the heart of a CNN. They consist of kernels. also known as filters, that systematically slide by s over the input array to extract relevant features. The convolution operation is mathematically defined as:

$$I\left(x,y\right)*f\left(x,y\right)=\sum_{i}\sum_{j}I\left(i.j\right)f\left(x-i,y-j\right)$$(6)where I(x, y) is an input array corresponding to individual colour channel, f(x, y) is a kernel.

The output dimension is given by

$$\left[\frac{m+2p-f}{s}+1\right]\times \left[\frac{m+2p-f}{s}+1\right]$$(7)where, m is the dimension of input image, p is number of zero padding around the border of the image, f is the kernel size and s is stride value.

-

2.

Activation Functions: Commonly used activation functions include Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) and Sigmoid. They introduce non-linearity, enabling it to learn complex relationships in the data.

$$ReLU: \text{a}\left(\text{t}\right)=\text{max}\left(0,t\right)$$(8)$$sigmoid: \sigma \left(t\right)=\frac{1}{1+{e}^{-t}}$$(9) -

3.

Pooling Layers: These layers decimate the spatial dimensions of the feature maps, reducing computational complexity. Max pooling takes the maximum value from a local region of the feature map. If max pooling size is 2 by 2 and applied with stride 2 then the dimension of output will be reduced by half.

-

4.

Fully Connected Layers: These layers connect every neuron in one layer to every neuron in the next layer. They are typically found towards the end of a CNN and are responsible for high-level reasoning.

CNNs are trained through backpropagation, where the weights of the network are updated to minimize the difference between predicted and actual outputs. Thus, CNN automatically learns the hierarchical features from data makes them an indispensable tool in Biomedical signal processing applications.

Pretrained CNN models

For photoplethysmography (PPG) based blood pressure estimation, pretrained models were used which has capability to extract remarkable deep features from extensive training on large datasets. In our framework, pretrained models serve as efficient feature extractors which processes two-dimensional arrays derived from PPG segments using continuous wavelet transform.

This research seeks to analyze and compare the accuracy of different pretrained models, namely, as VGG16, ResNet50, InceptionV3, NASNetLarge, InceptionResNetV2 and ConvNeXtTiny, in capturing relevant features from the scalograms and their effectiveness in accurately estimating systolic and diastolic BP values.

VGG16

In blood pressure estimation framework, VGG16 pretrained model was incorporated which was introduced by Simonyan and Zisserman in 2014, as a foundational CNN. VGG16 is recognized for its architectural simplicity and efficacy, maintaining uniformity with a consistent kernel size of 3 × 3, a stride of 1, and MAXPOOL layers of size 2 × 2 with a stride of 2. There are 16 levels as the number of kernels gradually rises by a factor of two to 512. A RGB image with dimensions of 224 × 224 is required as input for VGG16, which uses input normalization by the subtraction of mean pixel values72. Upon applying the Morlet wavelet to the PPG segment, a scalogram with initial size of 128 by 1000 is generated. However, a further transformation is required for compatibility with the VGG16 design, which demands a 224 by 224 by 3 input. This means that the 128 by 1000 grayscale array must be converted to RGB format. By doing so, a modified array of dimensions 224 by 224 by 3 was obtained that ensures seamless integration with the input requirements of the VGG16 pretrained model. The Fig. 5 illustrates the adapted architecture of VGG16 utilized in the blood pressure estimation framework with output dimension 7 × 7 × 512.

ResNet50

The deep residual network ResNet50, which was first introduced by He et al.73, is a key part of this approach for blood pressure assessment. With 50 layers, ResNet50 makes it easier to train incredibly deep CNNs and is now commonly used for a variety of computer vision tasks. Like VGG16, ResNet50 applies input normalization by removing the mean pixel values from a 224 × 224 RGB image as input73. ResNet50’s design is illustrated by a decrease in feature map dimension as depth increases, as seen in Fig. 6. The final output dimension of this model is 7 × 7 × 2048, yielding 2048 feature maps of size 7 × 7.

The obtained scalogram of dimensions 128 by 1000 is resized to meet the input requirements of ResNet50. The adapted ResNet50 architecture, showcased in the Fig. 6, serves as a feature extractor.

Inceptionv3

The pretrained Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model InceptionV3, created by Google74, is essential to the system for estimating blood pressure. To collect characteristics across different scales, InceptionV3 uses multiple concurrent convolutional paths with varied kernel sizes.

InceptionV3 expects a 224 by 224 by 3 input dimensions. The scalogram, which is originally 128 by 1000 in size, is transformed to fit the input specifications of InceptionV3. As part of this, the grayscale array must be formatted into RGB to make sure the model is compatible. The architecture of InceptionV3 is shown in the picture, which includes its convolutional, batch normalization, and pooling layers. This results in the creation of 2048 feature maps of dimension 5 by 5. InceptionV3 is also used as a feature extractor in the blood pressure prediction pipeline.

NASNetLarge

NASNetLarge, introduced by Zoph et al.75, is a neural architecture search-based network that achieves cutting-edge performance on various image recognition tasks. It also utilizes input normalization through subtracting the mean pixel values. It requires an input dimension of 331 by 331 by 3, thus the scalogram of size 128 by 1000 is transformed to align with the model’s input specifications. Thus, in the proposed approach, the pretrained CNN models (VGG16, ResNet50, Inception v3 and NASNetLarge) are used as feature extractors with the top layers being removed. The layers of the models are frozen except the fully connected dense layers. The output obtained from these pretrained models, referred to as deep features, captures high-level representations automatically extracted from the input images.

InceptionResNetV2

The Inception architecture and residual connections from ResNet are combined in InceptionResNetV2, which was created by Szegedy et al. in 201776. The combination produces a deep CNN that is highly effective in a several computer vision tasks. InceptionResNetV2, like NASNetLarge, applies input normalization through the subtraction of mean pixel values. It requires that input should be of dimensions of 299 by 299 by 3. To ensure that it is compatible with the model, input data i.e. scalograms is preprocessed. Together with other pretrained CNN models, InceptionResNetV2 is used as a feature extractor in the suggested methodology. In order to extract deep characteristics from input images, the network’s architecture involves freezing all layers other than the dense layers that are completely connected. The network’s architecture involves freezing all layers except the top layer and thereby produce deep features which are used in BP estimation.

ConvNeXtTiny

ConvNeXtTiny is a small CNN architecture that was presented by Liu Z et al. in 202077 and is intended for high performance in image recognition applications through efficient computing. ConvNeXtTiny’s architecture is optimized for resource-restricted situations, which sets it apart from the rest five models, and makes it appropriate for applications with constrained computational resources. One common preprocessing procedure that ensures consistency among input data is input normalization. The network anticipates that input images will have 224 × 224 by 3 dimensions. ConvNeXtTiny has frozen layers and the fully connected dense layers are fine-tuned. By using this method, deep characteristics from input can be effectively extracted and create useful representations for later tasks i.e. estimating blood pressure.

The process of extracting and flattening deep features from scalograms using the pretrained models mentioned above is shown in Algorithm 6.

The deep features extracted from the pretrained models are flattened to create a one-dimensional feature vector. This vector serves as the input to a random forest regressor described in the subsequent subsection, which predicts the blood pressure values.

Random forest

In random forest regression model, multiple decision trees are built by training on different bootstrapped subset of the feature vector (fattened) obtained from CNN. The dataset consists of m samples, denoted by D, \({\left\{\left({x}_{k}, {y}_{k}\right)\right\}}_{k=1}^{m}\) has p features in each sample, where \({x}_{k}\) is the feature vector and \({y}_{k}\) is the output vector. The next step is to create B bootstrapped datasets i.e. the no. of estimators (trees), denoted as \({D}_{b}\), \({\left\{\left({{x}_{k}}^{(b)}, {{y}_{k}}^{(b)}\right)\right\}}_{k=1}^{m}\) for b = 1, 2…B.

Once the bootstrapped dataset is created then the training process is started which involves repeatedly splitting the sample space into disjoint regions \({R}_{j}\) based on the features values. For each node, q features are randomly selected from p features. The best features are chosen with the corresponding split points such that the MAE is minimized within each region.

In each region \({R}_{j}\), the predictions \({c}_{j}\) is made by taking the average of the target values for \({y}_{k}\) for all the training samples that fall in that region, which is given by:

where \(\left|{R}_{j}\right|\) is the number of samples in region \({R}_{j}\).

For a new input \({x}_{k}\), the prediction from a single tree is determine by the region \({R}_{j}\) that the input \({x}_{k}\) falls into and the \({c}_{j}\) is obtained which is mathematically given as

where \({x}_{k}\) = new data.

F = no. of regions or splits in the sample space.

Where \(I\left({x}_{k}\in {R}_{j}\right)\) = indicator function which is given by

The final prediction of the Random Forest model is obtained by averaging the predictions from all B decision trees. The overall prediction \(f\left({x}_{k}\right)\) is given by

where B = no. of bootstrapped subsets (or trees).

The Algorithm 7 gives the detailed steps of implementation of Random Forest and predictions made by multiple trees. The averaging of the predictions made from multiple trees helps in reducing the variance thus reduces overfitting making the model more robust and generalizable.

The k-fold cross validation is also employed (Algorithm 7) to increase the robustness of random forest. In k-fold cross validation, the dataset is split into ‘k’ folds and the model is trained on ‘k-1’ folds and tested on the remaining one fold. The procedure is repeated for each fold and the average of performance metrics are calculated. The performance metrics used are MAE and Standard Deviation (SD) which is necessary to have compliance with clinical standards. The mathematical formula for both is given by

where n = number of observations; \({y}_{k}\) = target value; \({\widehat{y}}_{k}\) = predicted value.

where n = number of observations.

The number of estimators is set to 100. As discussed, the overfitting is reduced and prediction accuracy is improved by this ensemble model of decision trees. Thus, generates an effective model that captures a variety of data properties by combining the outputs of several trees. Also, the k value is set to 10, thereby dividing the dataset into ten subsets, maintaining ninefold for training and the remaining one for testing as part of a tenfold validation technique. Thus, the model that has been thoroughly evaluated using AAMI and BHS standard (Algorithm 8) using Random Forest with 100 estimators and tenfold validation is more robust and dependable.

Hardware and software specifications

The hardware and software specifications used in these experiments are displayed in Table 3.

Results and discussion

The proposed models, utilizing random forest with 100 estimators, are employed to estimate blood pressure at the systolic and diastolic levels, and their results are compared. The study’s findings are presented in Table 4, which offers a thorough summary of the accuracy obtained by each transfer learning model and demonstrates how successful they are as feature extractors for precise systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) measurement.

The results must satisfy the criteria set by AAMI clinical78 and BHS standards79. As per AAMI standard, the mean difference between a device and mercury standard should lie within 5 mm Hg and not exceed a SD of 8 mm Hg. The BHS’s objectives align with those of the AAMI standard. Table 5 lists the BHS classifications.

The BHS clinical standard states the validity of blood pressure measurement devices or algorithms based on the percentage of BP readings that fall within predefined error threshold when compared to a reference standard. The grading criteria are as follows:

-

Grade A: It requires ≥ 60% of BP samples to be within ± 5 mmHg, ≥ 85% within ± 10 mmHg, and ≥ 95% within ± 15 mmHg.

-

Grade B: It requires ≥ 50% of BP samples to be within ± 5 mmHg, ≥ 75% within ± 10 mmHg, and ≥ 90% within ± 15 mmHg.

-

Grade C: It requires ≥ 40% of BP samples to be within ± 5 mmHg, ≥ 65% within ± 10 mmHg, and ≥ 85% within ± 15 mmHg.

Grade A corresponds to the highest level of accuracy, followed by grade B and then grade C.

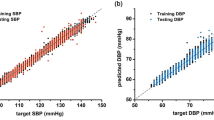

The achieved results (Figs. 7 and 8) illustrate the efficacy of various DL models in estimating BP using photoplethysmography (PPG) signals. Notably, the ConvNeXtTiny model and VGG16 exhibit the best performance, with MAE of 2.95 mmHg and 3.94 mmHg, respectively, for SBP and 1.66 mmHg and 2.56 mmHg, respectively, for DBP. These values fall well within the clinical standard of acceptable error. Additionally, both models maintain a relatively low standard deviation of 4.11 mmHg and 5.19 mmHg for SBP and 2.6 mmHg and 3.8 mmHg for DBP. This further confirms its reliability in terms of standard deviation. Even though the result achieved for ConvNeXtTiny and VGG16 had minimum error but the result obtained using the other three models also indicated good performance and compliance with the AAMI standard for DBP.

Considering the BHS criteria for grade A, where results should be greater than 60%, 85%, and 95%, the models’ performance can be assessed as follows:

-

For Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP):

-

ConvNeXtTiny meets the criteria A (Fig. 9) for all error thresholds, showcasing robust performance with high accuracy percentage (81.33%, 97.33% and 96.33% of the input data falls within the error of < 5 mmHg, within < 10 mmHg, and within < 15 mmHg respectively). And VGG16 also meets the criteria A with 68%, 96.67% and 98.67% of the input data that falls within the specified error.

-

Albeit the performance of ResNet50, InceptionV3, NASNetLarge, and InceptioResNetV2 aligns closely with grade A criteria for all error thresholds, it can be categorized as meeting grade B criteria (Figure 9) due to its proximity to the established benchmarks.

-

For Diastolic Blood Pressure (DBP):

-

All models perform well within grade A criteria (Fig. 10) for all error thresholds, with most of their estimates falling within the defined ranges.

Thus, the results show that the features extracted from PPG signals by the pretrained CNN models capture physiologically relevant information that correlates with blood pressure variations. The PPG signal reflects change in blood volume as heart pumps, which in turn is exhibited in their time–frequency representation. The scalograms obtained using continuous wavelet transform capture the dynamic variations of physiological data such as the systolic correlates with the rising edge and diastolic blood pressure with dicrotic notch. The DL models are capable of identifying intricate patterns in these time–frequency representation, which are challenging to capture manually. This complies with the clinical standard as discussed earlier.

Another important statistical metric used to quantify the linear relationship between two variables is the correlation coefficient (Pearson) which is denoted by ‘r’. Its value lies between −1 and 1. The value ‘−1’ indicates perfect negative linear relationship, ‘ + 1’ indicates perfect positive linear relationship, and no linear relationship is indicated by −0. The correlation coefficient between two variables X and Y is calculated by using following formula:

where \({X}_{i}\) and \({Y}_{i}\) are the individual records, \(\overline{X }\) and \(\overline{Y }\) are the mean of X and Y respectively.

In context of blood pressure estimation, Pearson correlation coefficient can be used to find out how close the estimated SBP and DBP values are with respect to target SBP and DBP. It provides a more complete picture of the result reliability. Table 6 shows that ConvNeXtTiny and VGG16 has greater correlation coefficient around 0.8 for both SBP and DBP as compare to other four models.

In summary, the presented results indicate that the models, particularly ConvNeXtTiny and VGG16, largely satisfies AAMI standard in BP estimation. Both achieved grade A for both SBP and DBP estimation, thereby meeting the BHS standard with good correlation. The superior performance is due to the fact that it has a consistent architecture with uniform filter and max-pooling dimensions. The other four models met the BHS clinical standard for DBP estimation with grade A and approached grade A for SBP estimation, demonstrating their effectiveness and proximity to meeting the BHS standard.

These findings highlight the potential of using pretrained models, such as VGG16, ResNet50, InceptionV3, NASNetLarge, InceptionResNetV2 and ConvNeXtTiny, as reliable tools for accurate BP estimation, satisfying the standards established by both AAMI and BHS in clinical blood pressure monitoring.

Benchmarking against established algorithms

In this analysis, an evaluation of the proposed method has been presented alongside several well-established approaches in the clinical field for BP estimation using physiological signals. The various algorithms were conducted on the MIMIC II and MIMIC III databases, employing various types of input features and machine learning models for comparison (Table 7).

According to the research papers, upon comparing their results, it has been discerned that the findings present a challenging perspective. Specifically, the obtained results demonstrate a notable advancement in the medical sciences field, specifically in the estimation of blood pressure values as per clinical standards.

This method grasps scalogram-based features and employed six pretrained models for prediction. The results demonstrate promising performance for ConvNeXtTiny and VGG-16 with mean absolute errors (MAE) in compliance with AAMI standard, underlining its potential for accurate blood pressure estimation. Furthermore, this approach meets BHS criterion with grade A, attesting to its clinical validity. For remaining four models, satisfying AAMI standard but achieved grade A BHS standard for DBP and grade B BHS standard for SBP. A comparative analysis was conducted exclusively with studies employing deep learning models, as this approach incorporates deep features in conjunction with deep learning architectures.

The primary novelty of the proposed model is highlighted in the study, which focuses on the application of the Morlet wavelet transform which results in so called scalograms and its distinctive features are highlighted below:

-

(a)

Multiresolution analysis:

The model captures both localized and global fluctuations in the time-frequency domain because of the multiresolution analysis of the PPG signals provided by the Morlet wavelet transform. Comparing this method to conventional time-domain techniques yields a more thorough description of the underlying physiological dynamics.

-

(b)

Frequency localization:

Morlet wavelet transform is very useful for evaluating non-stationary signals such as PPG, because it offers superior frequency localization compared to Fourier-based techniques. Thus, the model filter out unnecessary information and noise while focusing on specific frequency components that are relevant to blood pressure dynamics.

-

(c)

Adaptive representation:

In situations where the signal contains complex patterns as in case of PPG signals, scalograms provide a more reliable depiction of such PPG signals. The Morlet wavelet technique gives the PPG signals an adaptable representation, thus the model can capture changes in frequency content over time. Its adaptability is crucial for precisely characterizing the dynamic nature of blood pressure fluctuations since blood pressure changes can vary significantly in response to physiological and environmental stimuli.

-

(d)

Integration of pre-trained models with scalogram:

By using the Morlet wavelet transform in conjunction with pre-trained models for feature extraction, the model’s ability to extract discriminative representations from the scalograms is enhanced. Due to this integration, the model performs better on blood pressure estimation tasks by utilizing the benefits of both deep learning expressiveness and wavelet-based signal processing.

Integrating Morlet wavelet pre-processing into blood pressure estimation models can significantly enhance their performance. This blood pressure estimation method, that uses a Morlet wavelet preprocessing based scalograms of raw PPG signals and it complies with clinical standards. Although PPG signals and derivatives were included in the paper36,37,43, our focus on utilizing scalograms emphasizes the effectiveness of Morlet wavelet preprocessing in achieving challenging results through a simplified input method. The Morlet wavelet transform enhances the modeling process by capturing the nonlinear interactions present in physiological data, thereby improving the accuracy and robustness of BP estimation.

Overall, the proposed method exhibits competitive performance in comparison to prior works, demonstrating its potential as a reliable tool for blood pressure estimation in clinical applications by achieving results comparable to those of the previous studies listed in the above table. This thorough assessment serves as a baseline for further studies in this area.

The outcomes of the aforementioned implementation are as follows:

-

(a)

Scalogram-based transfer learning: The proposed algorithm presents a novel method for accurate blood pressure measurement from PPG data by combining transfer learning with scalogram-based preprocessing.

-

(b)

Data-driven solution: This research provides a simplified, data-driven methodology for continuous blood pressure monitoring, increasing efficiency and reliability by doing away with human feature engineering.

-

(c)

Model evaluation and selection: The study presents a methodical comparison of several deep learning models and shows that the most accurate blood pressure predictions are obtained when random forest regression is employed in conjunction with the ConvNeXtTiny and VGG16 models.

-

(d)

Standards compliance: The performance of the suggested approach is carefully assessed in accordance with accepted standards (AAMI and BHS), demonstrating its dependability for practical blood pressure monitoring applications.

-

(e)

Pearson connection Coefficient: For both ConvNextTiny and VGG16, a significant correlation was found between the estimated and true BP values.

Conclusions

In this study, a reliable and clinically validated approach for PPG based non-invasive blood pressure estimation using transfer learning is proposed. The proposed method, being a unique pathway for blood pressure estimation, uses transfer learning framework integrating deep features obtained from scalograms with Random Forest regression. The pretrained CNN models, such as VGG16, ResNet50, InceptionV3, NASNetLarge, InceptionResNetV2, and ConvNeXtTiny which are demonstrated to be effective in the study as feature extractors for estimating SBP and DBP from photoplethysmography (PPG) signals. The findings demonstrated the six models’ potential for accurate blood pressure measurement in clinical settings by showing that they all correlated well and met the AAMI’s accuracy standards for SBP and DBP estimation.

Additionally, the models performed very well when satisfying the BHS clinical criteria; ConvNeXtTiny and VGG16, for example, achieved grade A results for both SBP and DBP estimate. The other models approached grade A for SBP estimation and successfully satisfied the BHS criteria for DBP estimation. These findings suggest that pretrained models have the potential to enhance blood pressure monitoring accuracy, contributing to improved healthcare decision-making.

For future scope, further investigations can focus on expanding the analysis to include a larger dataset encompassing diverse patient populations. But, in handling larger dataset, the application of Morlet wavelet and pre-trained CNN models may require scalable computational resources, effective GPU acceleration, and optimised data pretreatment for computational efficiency, with any implementation issues taken into account. In additional to the this, exploring different CNN architectures and evaluating their performance on specific subgroups or medical conditions could provide valuable insights.

One potential area could be the evaluation of the impact of model performance at different frequency ranges in PPG signals, which provides an opportunity to increase the depth of the analysis. Incorporating other physiological signals and exploring multimodal approaches may also enhance the accuracy of blood pressure estimation. Finally, conducting real-time experiments and deploying the developed models in clinical environments would offer practical validation and help bridge the gap between research and clinical application. However, the implementation of this future scope could present challenges, such as the need to optimise for real-time processing constraints, handle legal and ethical issues about patient privacy, and ensure robust adaptability to various clinical data. These challenges emphasise the necessity of implementing a comprehensive plan to successfully integrate trained models into changing healthcare environments.

Data availability

In this study, the publicly available dataset was used for analysis. The dataset is accessible from University of California Irvine (UCI) Machine Learning Repository at the following link: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/340/cuff%2Bless%2Bblood%2Bpressure%2Bestimation.

References

Lawes, C. M., Vander Hoorn, S. & Rodgers, A. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet 371(9623), 1513–1518 (2008).

Lim, S. S. et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 380(9859), 2224–2260 (2012).

CVD Statistics. Accessed: Sep. 19. (2024). Available: https://www.ulster.ac.uk/cardiovascular/cvd-prevalence

Ding, X. R. et al. Continuous blood pressure measurement from invasive to unobtrusive: celebration of 200th birth anniversary of Carl Ludwig. IEEE J. Biomedical Health Inf. 20(6), 1455–1465 (2016).

Thomas, G. & Rees, D. Monitoring arterial blood pressure. Anaesth. Intensive Care Med. 19(4), 194–197 (2018).

Meidert, A. S. & Saugel, B. Techniques for non-invasive monitoring of arterial blood pressure. Front. Med. 4, 231 (2018).

Saugel, B., Dueck, R. & Wagner, J. Y. Measurement of blood pressure. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 28(4), 309–322 (2014).

Sattar, Y. & Chhabra, L. Electrocardiogram (StatPearls Publishing, 2023).

Allen, J. Photoplethysmography and its application in clinical physiological measurement. Physiol. Meas. 28(3) (2007).

Kamal, A. A., Harness, J. B., Irving, G. & Mearns, A. J. Skin photoplethysmography—A review. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 28(4), 257–269 (1989).

Nachman, D. et al. Comparing blood pressure measurements between a photoplethysmography-based and a standard cuff-based manometry device. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 16116 (2020).

Martin, S. L. et al. Weighing scale-based pulse transit time is a superior marker of blood pressure than conventional pulse arrival time. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 39273 (2016).

Vlachopoulos, C., Aznaouridis, K. & Stefanadis, C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55(13), 1318–1327 (2010).

Proença, M. et al. Pulse Wave Analysis Techniques. The Handbook of Cuffless Blood Pressure Monitoring: A Practical Guide for Clinicians, Researchers, and Engineers 107–37 (2019).

Mukkamala, R. et al. Toward ubiquitous blood pressure monitoring via pulse transit time: Theory and practice. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 62(8), 1879–1901 (2015).

Nichols, K. H., Rice, M. & Howell, C. Anger, stress and blood pressure in overweight children. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 26(5), 446–455 (2011).

Sood, P., Banerjee, S., Ghose, S. & Das, P. P. Feature extraction for photoplethysmographic signals using pwa: Ppg waveform analyzer. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Healthcare Service Management 250–255 (2018).

Elgendi, M. On the analysis of fingertip photoplethysmogram signals. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 8(1), 14–25 (2012).

Haddad, S., Boukhayma, A. & Caizzone, A. Continuous PPG-based blood pressure monitoring using multi-linear regression. IEEE J. Biomedical Health Inf. 26(5), 2096–2105 (2021).

Khalid, S. G., Zhang, J., Chen, F. & Zheng, D. Blood pressure estimation using photoplethysmography only: comparison between different machine learning approaches. J. Healthc. Eng. (2018).

Hossain Chowdhury, M. et al. Estimating blood pressure from photoplethysmogram signal and demographic features using machine learning techniques. arXiv e-prints. 2020 May:arXiv-2005.

Ye, Y., He, W., Cheng, Y., Huang, W. & Zhang, Z. A robust random forest-based approach for heart rate monitoring using photoplethysmography signal contaminated by intense motion artifacts. Sensors 17(2), 385 (2017).

Zhang, Y. & Feng, Z. A SVM method for continuous blood pressure estimation from a PPG signal. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Machine Learning and Computing 128–132 (2017).

Martinez-Ríos, E., Montesinos, L., Alfaro-Ponce, M. & Pecchia, L. A review of machine learning in hypertension detection and blood pressure estimation based on clinical and physiological data. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 68, 102813 (2021).

Kurylyak, Y., Lamonaca, F. & Grimaldi, D. A Neural Network-based method for continuous blood pressure estimation from a PPG signal. In 2013 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC) 280–283. (IEEE, 2013).

Atomi, K., Kawanaka, H., Bhuiyan, M. S. & Oguri, K. Cuffless blood pressure Estimation based on Data-Oriented continuous health monitoring system. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2017(1), 1803485 (2017).

Yoon, Y. Z., Kang, J. M., Kwon, Y., Park, S., Noh, S., Kim, Y., Hwang, S. W. Cuff-less blood pressure estimation using pulse waveform analysis and pulse arrival time. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 22(4), 1068–1074 (2017).

Monte-Moreno, E. Non-invasive estimate of blood glucose and blood pressure from a photoplethysmograph by means of machine learning techniques. Artif. Intell. Med. 53(2), 127–138 (2011).

Kachuee, M., Kiani, M. M., Mohammadzade, H. & Shabany, M. Cuff-less high-accuracy calibration-free blood pressure estimation using pulse transit time. In 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS) 1006–1009. (IEEE, 2015).

El Hajj, C. & Kyriacou, P. A. Cuffless and continuous blood pressure estimation from PPG signals using recurrent neural networks. In 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC) 4269–4272. (IEEE. 2020).

Xing, X. et al. An unobtrusive and calibration-free blood pressure estimation method using photoplethysmography and biometrics. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 8611 (2019).

Mousavi, S. S. et al. Blood pressure estimation from appropriate and inappropriate PPG signals using a whole-based method. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 47, 196–206 (2019).

Khalid, S. G. et al. Cuffless blood pressure Estimation using single channel photoplethysmography: A two-step method. IEEE Access. 8, 58146–58154 (2020).

Shimazaki, S., Bhuiyan, S., Kawanaka, H. & Oguri, K. Features extraction for cuffless blood pressure estimation by autoencoder from photoplethysmography. In 2018 40Th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) 2857–2860. (IEEE, 2018).

Slapničar, G., Mlakar, N. & Luštrek, M. Blood pressure estimation from photoplethysmogram using a spectro-temporal deep neural network. Sensors 19(15), 3420 (2019).

Harfiya, L. N., Chang, C. C. & Li, Y. H. Continuous blood pressure estimation using exclusively photopletysmography by LSTM-based signal-to-signal translation. Sensors 21(9), 2952 (2021).

El-Hajj, C. & Kyriacou, P. A. Cuffless blood pressure estimation from PPG signals and its derivatives using deep learning models. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 70, 102984 (2021).

Zhang, L., Ji, Y., Lin, X. & Liu, C. Style transfer for anime sketches with enhanced residual u-net and auxiliary classifier gan. In 2017 4th IAPR Asian Conference on Pattern Recognition (ACPR) 506–511. (IEEE, 2017).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5–9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III 18 234–241. (Springer, 2015).

Chen, X., Yao, L. & Zhang, Y. Residual Attention u-net for Automated Multi-class Segmentation of Covid-19 Chest ct Images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.05645 (2020).

Wang, J., Zhang, X., Lv, P., Zhou, L. & Wang, H. EAR-U-Net: EfficientNet and Attention-Based Residual U-Net for Automatic Liver Segmentation in CT. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.01014 (2021).

El-Hajj, C. & Kyriacou, P. A. Deep learning models for cuffless blood pressure monitoring from PPG signals using attention mechanism. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 65, 102301 (2021).

Yu, M., Huang, Z., Zhu, Y., Zhou, P. & Zhu, J. Attention-based residual improved U-Net model for continuous blood pressure monitoring by using photoplethysmography signal. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 75, 103581 (2022).

Vijayaraghavan, V. BP-Net: Efficient Deep Learning for Continuous Arterial Blood Pressure Estimation using Photoplethysmogram. arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.14558 (2021).

Mahmud, S., Ibtehaz, N., Khandakar, A., Tahir, A. M., Rahman, T., Islam, K. R., Chowdhury, M. E. A shallow U-Net architecture for reliably predicting blood pressure (BP) from photoplethysmogram (PPG) and electrocardiogram (ECG) signals. Sensors, 22(3), 919 (2022).

Athaya, T. & Choi, S. An estimation method of continuous non-invasive arterial blood pressure waveform using photoplethysmography: A U-Net architecture-based approach. Sensors 21(5), 1867 (2021).

Zhu, Z., Lin, K., Jain, A. K. & Zhou, J. Transfer learning in deep reinforcement learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intelligence (2023).

Zhang, N., Lu, J., Li, K., Fang, Z. & Zhang, G. Source-free unsupervised domain adaptation: Current research and future directions. Neurocomputing 564, 126921 (2024).

Li, K., Lu, J., Zuo, H. & Zhang, G. Multi-source contribution learning for domain adaptation. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 33(10), 5293–5307 (2021).

Li, K., Lu, J., Zuo, H. & Zhang, G. Multi-source domain adaptation handling inaccurate label spaces. Neurocomputing 594, 127824 (2024).

Fan, J., Lee, J. & Lee, Y. A transfer learning architecture based on a support vector machine for histopathology image classification. Appl. Sci. 11(14), 6380 (2021).

Swati, Z. N. et al. Brain tumor classification for MR images using transfer learning and fine-tuning. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 75, 34–46 (2019).

Kaur, T. & Gandhi, T. K. Deep convolutional neural networks with transfer learning for automated brain image classification. Mach. Vis. Appl. 31(3), 20 (2020).

Wang, W., Mohseni, P., Kilgore, K. L. & Najafizadeh, L. Cuff-less blood pressure estimation from photoplethysmography via visibility graph and transfer learning. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 26(5), 2075–2085 (2021).

Türk, Ö. & Özerdem, M. S. Epilepsy detection by using scalogram based convolutional neural network from EEG signals. Brain Sci. 9(5), 115 (2019).

Gupta, S., Singh, A. & Sharma, A. Automated detection of hypertension from PPG signals using continuous wavelet transform and transfer learning. In Signal Processing Driven Machine Learning Techniques for Cardiovascular Data Processing 121–133. (Academic Press, 2024).

Al Fahoum, A., Al Omari, A. & Al Omari, G. Development of a novel light-sensitive PPG model using PPG scalograms and PPG-NET learning for non-invasive hypertension monitoring. Heliyon, 10(21). (2024).

Moghaddam Mansouri, S. R.,Gholamhosseini, H., Lowe, A. & Lindén, M. Systolic blood pressure estimation from electrocardiogram and photoplethysmogram signals using convoluional neural networks. EJBI 16(2), 2–34 (2020).

Arvanaghi, R., Danishvar, S. & Danishvar, M. Classification cardiac beats using arterial blood pressure signal based on discrete wavelet transform and deep convolutional neural network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 71, 103131 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Improving the accuracy in classification of blood pressure from photoplethysmography using continuous wavelet transform and deep learning. Int. J. Hypertens. (2021).

Orini, M., Bailón, R., Mainardi, L. & Laguna, P. Synthesis of HRV signals characterized by predetermined time-frequency structure by means of time-varying ARMA models. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 7(2), 141–150 (2012).

Nasir, N., Sameer, M., Barneih, F., Alshaltone, O. & Ahmed, M. Deep Learning Classification of Photoplethysmogram Signal for Hypertension Levels. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14556 (2024).

Maharajan, R. Blood pressure estimation from wavelet scalogram of PPG signals using convolutional neural networks. Open Biomed. Eng. J. 18(1) (2024).

Lu, C.G. & Wang, L. Multiple feature extraction based on ppg signal to realize blood pressure measurement of composite multi-channel convolutional neural network model. In 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Electronic Communications, Internet of Things and Big Data (ICEIB) 307–312. (IEEE, 2023).

Liu, Y., Yu, J. & Mou, H. Photoplethysmography-based cuffless blood pressure estimation: an image encoding and fusion approach. Physiol. Meas. 44(12), 125004 (2023).

Chen, X., Yu, S., Zhang, Y., Chu, F. & Sun, B. Machine learning method for continuous noninvasive blood pressure detection based on random forest. IEEE Access. 9, 34112–34118 (2021).

Kachuee, M., Kiani, M. M., Mohammadzade, H. & Shabany, M. Cuffless blood pressure estimation algorithms for continuous health-care monitoring. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 64(4), 859–869 (2016).

Saeed, M. et al. Multiparameter intelligent monitoring in intensive care II: A public-access intensive care unit database. Crit. Care Med. 39(5), 952–960 (2011).

Romagnoli, S. et al. Accuracy of invasive arterial pressure monitoring in cardiovascular patients: An observational study. Crit. Care. 18, 1–1 (2014).

Torrence, C. & Compo, G. P. A practical guide to wavelet analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 79(1), 61–78 (1998).

Cohen, M. X. A better way to define and describe Morlet wavelets for time-frequency analysis. NeuroImage 199, 81–86 (2019).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale im kage recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556. 2014 Sep 4.

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 770–778 (2016).

Szegedy,C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2818–2826 (2016).

Zoph, B., Vasudevan, V. & Shlens, J. Le QV. Learning transferable architectures for scalable image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 8697–8710 (2018).

Szegedy, C., Ioffe, S., Vanhoucke, V., Alemi, A. Inception-v4, inception-resnet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 31, No. 1) (2017).

Liu, Z,, Mao, H., Wu, C.Y., Feichtenhofer, C., Darrell, T., Xie, S. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 11976–11986 (2022).

Stergiou, G. S. et al. A universal standard for the validation of blood pressure measuring devices: Association for the advancement of medical Instrumentation/European society of Hypertension/International organization for standardization (AAMI/ESH/ISO) collaboration statement. Hypertension 71(3), 368–374 (2018).

O’Brien, E. et al. The British hypertension society protocol for the evaluation of automated and semi-automated blood pressure measuring devices with special reference to ambulatory systems. J. Hypertens. 8(7), 607–619 (1990).

Li, Y. H., Harfiya, L. N., Purwandari, K. & Lin, Y. D. Real-time cuffless continuous blood pressure Estimation using deep learning model. Sensors 20(19), 5606 (2020).

Esmaelpoor, J., Moradi, M. H. & Kadkhodamohammadi, A. A multistage deep neural network model for blood pressure Estimation using photoplethysmogram signals. Comput. Biol. Med. 120, 103719 (2020).

Yang, S., Zhang, Y., Cho, S. Y., Correia, R. & Morgan, S. P. Non-invasive cuff-less blood pressure Estimation using a hybrid deep learning model. Opt. Quant. Electron. 53, 1–20 (2021).

Li, Z. & He, W. A continuous blood pressure estimation method using photoplethysmography by GRNN-based model. Sensors 21(21), 7207 (2021).

Zhou, K., Yin, Z., Peng, Y. & Zeng, Z. Methods for continuous blood pressure estimation using temporal convolutional neural networks and ensemble empirical mode decomposition. Electronics 11(9), 1378 (2022).

Subramanian, S., Mishra, S., Patil, S., Kolekar, M. H. & Ortiz-Rodriguez, F. Integrating transfer learning with scalogram analysis for blood pressure estimation from PPG signals.https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4479594/v1 (2024).

Jeong, D. U., & Lim, K. M. Combined deep CNN–LSTM network-based multitasking learning architecture for noninvasive continuous blood pressure estimation using difference in ECG-PPG features. Scientific Reports 11(1), 13539 (2021).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Symbiosis International (Deemed University). This work was supported by the Research Support Fund (RSF) of Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, India.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., S.M. and S.P.; methodology, S.S., S.M. and S.P.; software, S.S., S.M. and S.P.; validation, S.S., S.M. and S.P.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, S.S. and S.M.; resources, S.S.; data curation, S.S., S.M., S.P., M.K., and F.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.M. S.P., M.K., and F.O.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, S.M., S.P., M.K., and F.O; project administration, S.M., S.P., M.K., and F.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Subramanian, S., Mishra, S., Patil, S. et al. Integrating transfer learning with scalogram analysis for blood pressure estimation from PPG signals. Sci Rep 15, 39647 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23350-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23350-y