Abstract

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) are common in older adults and are associated with cognitive disorders. They typically arise from small vessel disease, leading to demyelination and axonal loss. WMH are thus considered markers of cerebrovascular changes. However, other pathophysiological processes can lead to WMH, particularly in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Understanding the diverse origins of WMH could enhance the diagnosis and treatment of AD patients. We hypothesize that multimodal neuroimaging could help understand the heterogeneity of WMH and pinpoint their specific origin. We included 142 older adults from the community and memory clinic (with an emphasis on patients within the Alzheimer’s continuum), and tested if multimodal neuroimaging signal within regional WMH (including T1w, T2w, 18F-florbetapir [AV45] and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose [FDG] PET), is associated with amyloid load and cognition. We showed that intra-WMH T1w and T2w signal in the parietal and frontal lobes were linked to amyloid status; intra-WMH T2w signal in all regions negatively correlated with amyloid load, while intra-WMH T1w signals in the parietal lobe positively correlated with amyloid load; finally, intra-WMH T1w signal negatively correlated with cognition while T2w and marginally AV45 signals positively correlated with cognition. This study demonstrates the potential of multimodal neuroimaging to unravel the heterogeneity of WMH, which could enhance their interpretation and improve clinical decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) are frequently found on brain MRI of older adults. They are associated with cognitive disorders and an increased risk of dementia or stroke, although many cognitively unimpaired older adults also present with these lesions1,2. The main pathophysiological pathway leading to WMH in older adults is cerebral small vessel disease, associated with demyelination and axonal loss due to ischemia1. Thus, WMH are commonly considered surrogate biomarkers of cerebrovascular dysfunction. However, various histological changes could be associated with WMH and multiple pathophysiological pathways may be involved3,4,5,6,7. Recently, we discussed the potential origin of WMH in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), suggesting that beyond the “pure vascular origin”, some WMH may result from AD-related processes6. AD-related WMH may involve AD-related neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation as possible triggers, in addition to specific vascular pathways (i.e. cerebral amyloid angiopathy and endothelial dysfunction). However, this hypothesis is still debated8,9,10. A better understanding of the origins of WMH could greatly enhance our knowledge of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying brain ageing and AD, enabling more personalized diagnosis and care for patients with neurocognitive disorders. Clinically, this is especially relevant with the advent of anti-amyloid drugs. Hemorrhagic features of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), such as microbleeds, are risk factors for amyloid-related imaging abnormalities11 and may exclude patients from these therapies12. It is currently unknown whether CAA-related WMH are associated with an increased risk of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities and how this might affect the prescription of these drugs, necessitating further exploration. Additionally, refining the definition of WMH is important for patient care, such as intensifying management of vascular risk factors when WMH are related to such risks.

For all these reasons, better in vivo characterization of WMH is essential. While neuropathological studies provide insights into the origins of WMH5,13,14, unraveling their heterogeneity in vivo could significantly benefit patients. Moreover, in vivo studies are crucial, as postmortem MRI has limitations in accurately detecting WMH due to brain changes and tissue fixation, which can alter relaxation times, water content, and tissue structure15. Assessing the signal intensity within WMH using multimodal neuroimaging could help unravel this heterogeneity. For example, a study showed that retention of the amyloid PET tracer 18F-florbetapir in normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) and in WMH was as marker of demyelination, progression across the AD continuum, and was associated with abnormal AD fluid biomarkers16. Another study showed that lower 18F-florbetapir in WMH was associated with higher extracellular free water (potentially of vascular or inflammatory origin) and lower cognition17. Other studies evaluated the MRI signal (T1-weighted [T1w], T2-weighted [T2w], T1w/T2w ratio, relaxation times from quantitative T1 [qT1] and quantitative T2* [qT2*]) within NAWM and WMH and showed microstructural tissue alterations in WMH18,19. However, a multimodal approach including both MRI and PET imaging signals within WMH, and their association with both biological (amyloid) and clinical (cognition) outcomes is lacking. At this stage, as there are very few studies exploring this question, it remains unclear whether combining imaging methods is superior to using a single one. In addition, the topography of WMH can be important for identifying their origin. Indeed, several studies have shown that the localization of WMH may be linked to underlying etiologies. For example, posterior (i.e. parieto-occipital) WMH are often associated with AD features, such as AD-related neurodegeneration and/or CAA4,20,21, while anterior (i.e. frontal) WMH are more commonly associated with vascular risk factors and hypertensive arteriopathy5,6,20. Therefore, alongside intra-lesion signal characteristics, the topography of lesions can provide valuable insights into the nature of WMH in vivo. Notably, a recent study used automated classification procedures to classify WMH into three distinct classes based on lesion characteristics and their spatial location. They showed that these classes were associated with different clinical risk factors, such as hypertension, physical activity levels, and sleep quality, supporting the notion of heterogeneity in the nature and clinical implications of WMH22.

The main objective of this study is to investigate whether multimodal neuroimaging signals within WMH – specifically T1w, T2w, 18F-florbetapir (AV45) and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) – across different brain regions, are associated with amyloid status (positive or negative) in healthy older adults and in memory clinic patients. Our secondary, exploratory, objectives are to investigate the relationships between multimodal neuroimaging signals within WMH, and amyloid load (standardized uptake value [SUVR] in neocortical regions) as well as cognitive outcomes in the same population. Overall, our aim is to identify intra-WMH imaging signals that can help distinguish WMH heterogeneity in vivo. To be informative, these signals should differ from those in NAWM, vary according to amyloid status, and correlate with cognitive function.

Results

Characteristics of the population

Participants’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Differences between global NAWM and global intra-WMH signals

The neuroimaging signal differed between global NAWM and global intra-WMH for all imaging modalities (T1w, T2w, FDG or AV45), with lower T1w, FDG and AV45 and higher T2w signals in WMH than in NAWM (all p-values < 0.001); greater effect sizes were observed for T1w, T2w and FDG compared to AV45 (Fig. 1). There are not or mild associations between volumetric measures of WMH (i.e. regional volumes of WMH) and intra-WMH signal intensity, except for intra-WMH FDG signal (details in Supplementary Table S1).

Relationships between intra-WMH signal intensity and binary amyloid status

In the frontal lobe, only the intra-WMH T2w signal was associated with the amyloid status, with lower T2w signal in amyloid-positive participants (estimate − 0.04, t-value − 2.14, uncorrected p-value 0.03) in the model controlling for age (Fig. 2), but this association was not significant when the clinical status was added in the model (estimate − 0.02, t-value − 1.10, uncorrected p-value 0.28). Results were unchanged when frontal WMH volume was added in the model. Intra-WMH T1w, FDG and AV45 signals in the frontal lobe were not significantly associated with the amyloid status (details in Supplementary Table S2). In the parietal lobe, intra-WMH T1w signal was higher (estimate 0.06, t-value 2.77, uncorrected p-value 0.01) and T2w signal was lower (estimate − 0.03, t-value − 2.03, uncorrected p-value 0.04) in amyloid-positive participants in the models controlling for age (Fig. 2), but these associations were not significant when the clinical status was added in the model (respectively estimate 0.04, t-value 1.65, uncorrected p-value 0.10, and estimate − 0.02, t-value − 0.97, uncorrected p-value 0.34). Results were unchanged when parietal WMH volume was added in the model. Intra-WMH FDG and AV45 signals in the parietal lobe were not significantly associated with the amyloid status (details in Supplementary Table S2). Finally, no relationships were found with intra-WMH signal in the temporal or occipital lobes (details in Supplementary Table S2). Results were globally unchanged when sex was considered in models as covariate.

Exploratory analyses of the relationships between the intra-WMH signal and cortical amyloid load (continuous)

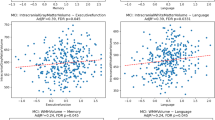

In the models controlling for age, the intra-WMH T1w signal in the parietal lobe positively correlated with the cortical amyloid load (estimate 0.10, t-value 3.13, uncorrected p-value 0.002) (Fig. 3), but not in the other lobes (details in supplementary Table S3). This association remained significant when the clinical status (cognitively impaired/unimpaired) was added in the model (estimate 0.08, t-value 2.07, uncorrected p-value 0.04). The intra-WMH T2w signal in all lobes negatively correlated with the cortical amyloid load (frontal lobe: estimate − 0.08, t-value − 3.19, uncorrected p-value 0.002; parietal lobe: estimate − 0.07, t-value − 2.93, uncorrected p-value 0.004; temporal lobe: estimate − 0.06, t-value − 2.13, uncorrected p-value 0.04; occipital lobe: estimate − 0.07, t-value − 2.20, uncorrected p-value 0.03). These associations remained significant for the frontal and parietal lobes when the clinical status (cognitively impaired/unimpaired) was added in the model (details in Supplementary Table S3). Relationships between cortical amyloid load and intra-WMH FDG or AV45 signal were not significant except for the intra-WMH AV45 signal in the occipital lobe that positively correlated with AV45 SUVR (estimate 0.15, t-value 2.91, uncorrected p-value 0.004), and for the intra-WMH FDG signal in the occipital lobe that negatively correlated with AV45 SUVR when models were adjusted for clinical status (estimate − 0.05, t-value − 2.14, uncorrected p-value 0.03; details in supplementary Table S3). Significant associations remain unchanged when regional WMH volumes were added in the models. Figure 3 illustrates the relationships between intra-WMH signal in the parietal lobe and cortical amyloid load. Results were globally unchanged when sex was considered in models as covariate.

Exploratory analyses of the relationships between intra-WMH signal and cognition

Relationships between intra-WMH signal and MMSE, adjusted for age, gender, level of education and clinical status are detailed in Table 2. The intra-WMH T1w signal in all brain regions, except in the temporal lobe, was negatively associated with the MMSE score, i.e., higher cognition was associated with lower intra-WMH T1w signal (Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 1). The intra-WMH T2w signal in all brain regions was positively associated with the MMSE score, i.e., higher cognition was associated with higher intra-WMH T2w signal (Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 2). The intra-WMH AV45 signal on parietal and temporal regions was positively associated with MMSE (Table 2). Results remain unchanged when region WMH volumes were added in the models. When global cognition was assessed with the Mattis DRS instead of the MMSE, results were globally unchanged.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of participants from cognitively unimpaired amyloid-negative older adults to patients with AD dementia, we examined whether multimodal neuroimaging signals within WMH detected on FLAIR in various brain regions were associated with amyloid pathology and cognitive function. We first showed that global T1w, T2w, FDG and AV45 signals within WMH all significantly differed from those in NAWM. Then, we found that (1) the intra-WMH T1w and T2w signals in the parietal lobe and the intra-WMH T2w signals in the frontal lobe were associated with the amyloid status (amyloid-positive participants had higher T1w and lower T2w signal within WMH than amyloid-negative participants); (2) the intra-WMH T2w signal in all brain regions negatively correlated with cortical amyloid load, while the intra-WMH T1w signal in the parietal lobe positively correlated with cortical amyloid load; and (3) the intra-WMH T1w signal in all brain regions except in the temporal lobe was negatively associated with cognition, while the intra-WMH T2w signal in all brain regions was positively associated with cognition. Overall, the intra-WMH AV45 and FDG signals were not or weakly associated with amyloid load or status and cognition, whereas the T1w and T2w signals demonstrated the most consistent associations.

Imaging signals within WMH significantly differ from those in NAWM across all imaging modalities, with the largest effect sizes observed in FDG-PET signals. Higher T2w signals within WMH compared to NAWM was expected as WMH definition is based on T2w or T2-FLAIR hyperintensities23. We observed lower T1w in WMH compared to NAWM, which was also expected as T1w and T2w signal negatively correlate19, and WMH are quite systematically associated with T1w hypointensity24. The observed reduction in FDG signal in WMH compared to NAWM is consistent with a previous study25 and with the decrease in metabolic activity in damaged tissue. Finally, we found that the intra-WMH AV45 signal was significantly lower than the NAWM signal, aligning with previous studies16,17. The uptake of amyloid tracers in white matter may be due to the similar beta-sheet structure of myelin proteins, and the reduced AV45 signals within WMH could be attributed to microstructural damages or demyelination17. Thus, imaging signals within WMH differed from signals within NAWM for these 4 imaging modalities, and could be modified differently depending on the underlying nature of WMH.

We found that intra-WMH T1w and T2w signals were the most consistently linked to amyloid status, amyloid load, and cognition. Specifically, higher T1w signal and lower T2w signal within WMH, particularly in the parietal lobe, were associated with greater amyloid pathology and worse cognition. The exact pathobiological processes underlying changes in T1w and T2w signal within white matter lesions (WMH) is not yet well understood. Concerning T1w signal within WMH, our findings differ from two previous studies that suggested that T1w hypointense WMH are associated with more severe white matter damage, such as demyelination and axonal loss, as well as greater cognitive decline26,27. Thus, Dadar and collaborators found that lower T1w signals in WMH were associated with the progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia and the time to conversion26. Similarly, Melazzini and collaborators reported that T1w hypointense WMH were significantly associated with lower cognition and higher microstructural damage27. A comparison has been made with multiple sclerosis, where T1w hypointense WMH (referred to as “black holes”) are considered as permanent damage and associated with lower cognition28. The apparent discrepancy between our findings and previous studies may reflect different relationships of WMH T1w and T2w signal to cognition depending on their origin. Our results suggest that amyloid-related WMH are associated with higher T1w and lower T2w signals, which might reflect reversible damage, such as AD-related neuroinflammation, but still correlate with worse cognition due to their connection to Alzheimer’s disease. In line with this hypothesis, a previous study showed that lower quantitative T1 signal is associated with lower axonal, myelin density and microglial activation in AD29. As quantitative T1 negatively correlated with T1w signal19, we could expect that greater microglial activation would be associated with higher T1w signal. On the other hand, lower T1w and higher T2w signals might indicate non-amyloid related WMH, such as those caused by vascular factors, where the most hypointense T1w signals represent the most severe, permanent WM damage and are linked to worse cognitive outcomes. Overall, based on our results, we could hypothesize that AD-related or amyloid-related WMH are associated with higher T1w and lower T2w signal within WMH, while non-amyloid-related WMH may be associated with lower T1w and higher T2w signal. If confirmed, this would suggest that T1w and T2w signals might be helpful to distinguish WMH of different origins. Future studies, including radio-pathological correlation studies are needed to better understand the nature of T1w and T2w changes in white matter and in WMH.

In this study, the intra-WMH AV45 and FDG signals were globally weakly associated with amyloid load or status. Specifically, no associations were found with the amyloid status, and, for both FDG and AV45, correlations with amyloid load were restricted to the intra-WMH signals in the occipital lobe. For AV45, this is in line with the hypothesis that uptake of amyloid tracers in white matter, and a fortiori in WMH, may not reflect the presence of cortical amyloid pathology, but a local feature of white matter composition. One previous study did report significant difference in the intra-WMH FDG signal according to the amyloid status in 50 participants with subjective cognitive decline or mild cognitive impairment30. However, since our findings do not align with this earlier study, replication in larger cohorts is needed. Regarding the link with cognition, we found that lower intra-WMH AV45 signals in the parietal and temporal lobes were associated with lower cognitive performance in models adjusted for age, gender, education and clinical status. This result is consistent with previous studies showing that lower AV45 signal in the white matter was associated with lower white matter integrity (higher free water and lower fractional anisotropy)17 and with higher Alzheimer’s and neurodegeneration biomarkers16. Intra-WMH FDG signal was not associated with cognition in models adjusted for age, gender, education and clinical status.

Beyond intra-WMH neuroimaging signals, we also tested whether the topography of lesions was differentially associated with amyloid deposition or cognition. Associations between intra-WMH signals and amyloid status were found only in the parietal lobe for T1w and in the parietal and frontal lobes for T2w. Similarly, cortical amyloid load was associated with intra-WMH T1w only in the parietal lobe, with intra-WMH T2w signals in all regions and with intra-WMH AV45 signal in the occipital lobe. Moreover, intra-WMH T1w and T2w signals in the parietal lobe were more strongly associated with cognition than in other regions. Thus, the only region in which we found an association between T1w and T2w signal and (1) amyloid status, (2) cortical amyloid load, and (3) cognition is the parietal lobe. Previous studies suggest that anterior lesions are more closely linked to vascular risk factors, while posterior lesions are more commonly linked to the amyloid pathway6,20,31. While the results of this study do not allow us to prejudge the precise nature of WMH origin, our findings related to the parietal lobe align with previous studies highlighting the specificities of parietal WMH in AD4,6,32, and suggesting a possible AD-related pathophysiology for these particular lesions. However, if the results show stronger associations with intra-WMH signals in the parietal lobe, we also found associations in other brain regions, suggesting that while amyloid-related WMH may be more prevalent in the parietal lobe, they are not exclusively restricted to this area.

Notable strengths of our study include the inclusion of a large group of participants older adults from the community and memory clinics (with an emphasis on patients within the Alzheimer’s continuum), with multimodal neuroimaging including both MRI and FDG/AV45 PET, all acquired at a single site under consistent conditions for all participants. The study also has several limitations. The lack of neuropathological assessments limits our ability to directly link intra-WMH multimodal neuroimaging signals to underlying pathology. The cross-sectional design prevents causal interpretations, and other, possibly relevant, imaging measures, such as diffusion imaging and other quantitative MRI metrics (such as quantitative T2*) could be relevant19. LST-LPA was used for WMH automated segmentations, and several other WMH segmentations algorithms exist33. While LST-LPA is highly sensitive for detection of WMH, the use of other segmentation algorithms could give different lesion volumes and maps, and therefore potentially modify these results. Comparing results with other WMH segmentation algorithm would be valuable. Note that when these results were also adjusted for lesion volumes, results remain globally unchanged (data not shown). Moreover, AV45 PET signals to measure amyloid status and amyloid load in participants were extracted from PET images corrected for partial volume effects, whereas intra-WMH PET signals were extracted from non-corrected PET images. This could increase the risk of errors due to partial volume effects. We used 4 neuroimaging modalities (MRI-T1w, MRI-T2w, FDT-PET, AV45-PET) because they were available in the IMAP cohort, but other neuroimaging modalities, like Tau-PET imaging would be very interesting in this context34 and need to be studied in the future. Finally, while our findings suggest that intra-WMH T1w and T2w signals may help distinguish AD-related WMH from non-AD-related WMH, further research is needed to establish specific processing techniques, thresholds, stages, populations and conditions before these findings can be applied clinically.

To conclude, this study brings new insights into the pathophysiology of WMH in vivo through the analysis of intra-WMH multimodal neuroimaging signals. One of the key findings is that WMH tend to exhibit lower T2w signal and higher T1w signal in amyloid-positive participants compared to amyloid-negative participants, especially in the parietal lobe. The use of T1-weighted and T2-weighted sequences is particularly advantageous, as they are routinely performed and do not increase acquisition time or require additional costly techniques. This approach could pave the way for differentiating the origins of WMH in AD patients, particularly for distinguishing amyloid-related (or AD-related) WMH from those caused by sporadic hypertensive angiopathy. Future studies utilizing additional imaging modalities, longitudinal design and radiopathological correlations are essential to validate and expand these findings. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of the specific mechanisms behind each type of lesion could significantly impact clinical practice, especially in the context of emerging anti-amyloid immunotherapies for AD.

Methods

Study population

One hundred forty-two participants from the IMAP+ (Multimodal neuroimaging of early Alzheimer’s disease) cohort35,36 were included in the present study. They were all native French speakers, with at least 7 years of education, living at home, without history or clinical evidence of neurological or psychiatric disorders, alcohol use disorder or drug abuse, and with a normal somatic examination. The inclusion and group classification of the participants were based on a clinical interview and a standardized neuropsychological assessment, according to internationally agreed criteria. The participants included in the present study were divided in 71 cognitively unimpaired older adults (including 57 amyloid-negative and 14 amyloid-positive individuals; see infra for details), and 71 cognitively impaired patients (17 amyloid-negative and 54 amyloid-positive; see infra for details). The cognitively unimpaired group consisted of 44 individuals with no subjective cognitive complaint recruited from the community and 27 individuals with subjective cognitive complaint recruited from memory clinics. All 71 cognitively unimpaired participants had normal performance for their age and educational level in all neuropsychological tests and had no history or clinical evidence of major neurological or psychiatric disorders, detailed in previous publications. The cognitively impaired patients, recruited from memory clinics, were selected based on Petersen’s criteria for amnestic mild cognitive impairment (n = 48) or on National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke, and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) clinical criteria for probable Alzheimer’s disease (n = 23) based on international clinical criteria37,38. Clinical diagnosis was assigned by consensus under the supervision of a senior neurologist and neuropsychologists. The IMAP + study was approved by the local ethics committee (CPP Nord-Ouest III) and registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01638949, date of registration 2012-05-22). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants gave their written informed consent to the study before the examinations.

Multimodal neuroimaging acquisition and processing

All participants performed a high-resolution anatomical MRI, as well as an 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) and a 18F-florbetapir (AV45) PET scans, within a few days or weeks at the same neuroimaging center (Cyceron, Caen, France).

MRI acquisition and processing

MRI acquisition and processing was previously described2,21. Briefly, MRI scans were acquired on a Philips Achieva 3 T scanner (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) using a 3D fast-field echo sequence. A high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical volume (3D-T1-FFE sagittal; repetition time TR = 20 ms; echo time TE = 4.6 ms; flip angle = 10°; 180 slices with no gap; slice thickness = 1 mm; field of view = 256 × 256 mm2; in plane resolution = 1 × 1 mm2), a high-resolution T2-weighted spin echo anatomical acquisition (2D-T2-SE sagittal; SENSE factor = 2; repetition time = 5500 ms; echo time = 80 ms; flip angle = 90°; 81 slices with no gap; slice thickness = 2 mm; field of view = 256 × 256 mm2; in-plane resolution = 1 × 1 mm2) and a high-resolution T2-weighted FLAIR anatomical volume (3D-IR sagittal; TR/TE/TI (inversion time) = 8000/348/2400 ms; flip angle = 90°; 90 slices with no gap; slice thickness = 2 mm; field of view = 250 × 250 mm2; in-plane resolution = 0.78 × 0.78 mm2) were acquired (Fig. 4). All images preprocessing steps were performed with using Statistical Parametric Mapping 12 (SPM12, MatLab v. 2018b; MathWorks, Natick, MA) unless stated otherwise.

FLAIR and T1w images were coregistered, and WMH were segmented by the lesion prediction algorithm LPA (Schmidt, 2017, Chap. 6.1) as implemented in the Lesion Segmentation Toolbox version 2.0.15 (www.statistical-modelling.de/lst.html for SPM), based on the calculation of a lesion probability score for each voxel, using FLAIR + T1w as inputs. Lesion probability maps were binarized by applying a threshold of 0.5 for signal intensity, with a minimal cluster extent of 10 mm3. For each individual binary lesion map, WMH were classified regionally based on anatomical atlases (frontal, temporal, parietal, occipital lobes with Hammers atlas40. Topography of WMH in the IMAP cohort was previously detailed21,31, showing a common distribution, with periventricular and deep lesions and a mild posterior predominance. T1w MRI was segmented and normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using the SPM ‘Unified Segmentation’ procedure. The deformation parameters obtained from this procedure were used to align all the imaging modalities into the MNI space. The T2w images were also coregistered onto the T1w and normalized into the MNI space using the deformation parameters obtained from the MRI segmentation procedure. T1w and T2w images were quantitatively normalized using a global mask encompassing white matter (WM), grey matter (GM), and cerebrospinal (CSF). To construct this mask, we used the individual GM, WM and CSF segments spatially normalized to MNI space derived from the segmentation of the corresponding T1-weighted images. For each tissue class, a mean image was created by averaging across all subjects. Each of these three mean images was then thresholded at 3% to generate binary masks of GM, WM and CSF, which were subsequently combined to yield a single global mask. This global mask was then applied to each spatially normalized individual T1w, and T2w images to extract a global mean intensity value per subject. Each voxel in the corresponding T1w, and T2w image was then divided by this global value to achieve intensity normalization. Finally, intra-WMH signals were extracted by applying individual binary WMH maps to the corresponding intensity normalized T1w and T2w images. Regional mean signals were obtained by averaging values across all WMH within each lobe, i.e. in frontal, temporal, parietal, occipital lobes defined by the Hammers Atlas, as previously described (Fig. 4).

18F-Florbetapir PET (AV45) and 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET (FDG)

Both AV45 and FDG PET scans were acquired on a GE Healthcare Discovery RX VCT 64 PET-CT device (General Electric Healthcare).

For AV45 PET, participants received an intravenous injection of ~ 4MBq/Kg of florbetapir and a 10-minutes or a 20-minutes scan was acquired 50 min after the injection. Scans were acquired with a resolution of 3.76 × 3.76 × 4.9 mm3 (field of view = 157 mm). Forty-seven planes were obtained with a voxel size of 1.95 × 1.95 × 3.27 mm3. The 10-min or 20-min PET scan acquisition began 50 min after the injection. A transmission scan was performed for attenuation correction before acquisition. After correction for randoms, decay, deadtime, attenuation, and scatter, raw data were reconstructed using OSEM 2D and a Gaussian post-filter (fwhm 2.14 mm) using Discovery VCTHD-64 GE Medical Systems version 1.23.V40. PET images were corrected for partial volume effects (PVE) with PMOD Technologies Ltd, coregistered onto the corresponding T1-weighted image and spatially normalized into the MNI space using the deformation parameters derived from the MRI segmentation procedure, previously computed with SPM. Then, the resulting images were scaled, using cerebellar grey matter as a reference to obtain standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) images. Finally, to measure cortical amyloid load for each participant, normalized and scaled AV45-PET images were used to extract the individual global cortical SUVR with a predetermined neocortical mask (including the entire grey matter, except the cerebellum, occipital and sensory motor cortices, hippocampi, amygdala and basal nuclei)41. Amyloid-positivity was defined when SUVR (with partial volume correction) was superior to 0.99, which corresponds to the 99.9th percentile of SUVR distribution among cognitively unimpaired young adults aged < 40 years (n= 45)42.

For FDG PET, participants were fasted for at least 6 h and remained in a quiet, dark environment for 30 min before injection of the radiotracer. Fifty minutes after the intravenous injection of 180 MBq of FDG, a 10 min PET acquisition began. FDG PET images were coregistered onto the corresponding T1w and spatially normalized into the MNI space using the deformation parameters derived from the MRI procedure, previously computed with SPM. Then, the resulting images were scaled, using cerebellar grey matter as a reference to obtain SUVR. Based on the binary map of WMH for each subject, as previously described for normalized T1w and T2w signals, intra-WMH normalized AV45 and FDG SUVR were extracted in each brain region (Fig. 4).

Clinical and cognitive variables

Sociodemographic variables consisted of age, sex, and level of education (in years). The participants underwent the measure of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and a neuropsychological assessment, fully described elsewhere2,35. Global cognition was evaluated with the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (Mattis-DRS), and with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)43.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the R/RStudio software Version 2023.09.1 + 494 (2023.09.1 + 494) (R Core Team). The study population characteristics were described using the mean (standard deviation SD), or the number and percentage, as appropriate. Firstly, we compared the global intra-WMH multimodal neuroimaging signal to the global NAWM signals using t-tests, and Cohen’s d (effect size) were calculated in the whole population. Then, to assess the relationships between intra-WMH multimodal neuroimaging signal (respectively T1w, T2w, FDG, AV45) and amyloid status, linear models were run with the intra-WMH signal as the dependent variable, and the amyloid status (binary: positive/negative) as the independent variable, controlling for age. Next, models were run with the intra-WMH signal as the dependent variable and amyloid load (continuous: AV45 SUVR) as the independent variable, controlling for age. Moreover, to explore the relationships with cognition, linear models were employed with the intra-WMH signal as the dependent variable and global cognitive scores (Mattis DRS and MMSE in separate models) as independent variables, adjusting for age, gender and level of education as they are usually associated with cognition. All models were also adjusted for the clinical status (cognitively impaired versus cognitively unimpaired), to check if the results obtained are driven by a clinical group or not. Finally, models were adjusted for regional WMH volumes, when indicated in the manuscript. In case of missing data, the participant was excluded from the corresponding analysis. The significance level was set to p < 0.05.

Comparison between global NAWM versus intra-WMH signals for each neuroimaging modality. Boxplots comparing the global signal intensity within NAWM versus in WMH according to the different imaging modalities (T1w, T2w, FDG, AV45). Uncorrected p-values (p) of the t-tests and Cohen’s d (effect sizes) are indicated in the plot. AV45: Amyloid PET (florbetapir, 18 F-AV45); FDG: Fluorodeoxyglucose PET (18 F-FDG); NAWM: normal-appearing white matter; WMH: white matter hyperintensities.

Relationships between the intra-WMH T1w or T2w signal in the frontal and parietal lobes and the amyloid status. Boxplots comparing the intra-WMH T1w or T2w signal within the frontal and parietal lobes according to the amyloid status (positive/negative). Uncorrected p-values (p) of the linear model adjusted for age and univariate Cohen’s d (effect size) are indicated in the plot. Aβ(-): amyloid-negative (AV45 PET); Aβ(+): amyloid-positive (AV45 PET); CI: cognitively impaired; CU: cognitively unimpaired.

Relationships between intra-WMH signal intensity in the parietal lobe and cortical amyloid load. Plots of the associations between intra-WMH signal (Y-Axis) in the parietal lobe for each neuroimaging modality (T1w, T2w, FDG and AV45) and cortical amyloid load (SUVR; X-Axis), controlling for age (with 95% confidence intervals). Standardized betas (β), estimates and uncorrected p-values are indicated for each plot. CI: cognitively impaired; CU: cognitively unimpaired.

Overall schematic representation of data analyses. A. Raw FLAIR images were segmented with the Lesion Prediction Algorithm (LST LPA), and the probability maps were binarized (threshold 0.5) to generate a binary map of WMH. B. The signal intensity from T1w, T2w, FDG and AV45 imaging within each lesion was extracted and averaged by brain region. Images do not come from the same participant.

Data availability

Data related to the current study are derived from the IMAP study. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and pending approval by the study coordinator.

References

Prins, N. D. & Scheltens, P. White matter hyperintensities, cognitive impairment and dementia: an update. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 11, 157–165 (2015).

Garnier-Crussard, A. et al. White matter hyperintensities across the adult lifespan: relation to age, Aβ load, and cognition. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 12, 127 (2020).

Wardlaw, J. M., Valdés Hernández, M. C. & Muñoz-Maniega, S. What are white matter hyperintensities made of? Relevance to vascular cognitive impairment. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 4, e001140 (2015).

McAleese, K. E. et al. Parietal white matter lesions in alzheimer’s disease are associated with cortical neurodegenerative pathology, but not with small vessel disease. Acta Neuropathol. 134, 459–473 (2017).

McAleese, K. E. et al. Frontal white matter lesions in alzheimer’s disease are associated with both small vessel disease and AD-associated cortical pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 142, 937–950 (2021).

Garnier-Crussard, A., Cotton, F., Krolak-Salmon, P. & Chételat, G. White matter hyperintensities in alzheimer’s disease: beyond vascular contribution. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 3738–3748 (2023).

Kuchcinski, G. & Wright, C. B. Show me your white Matter, I will tell you who you are …. Stroke 52, 631–633 (2021).

Brickman, A. M. & Rizvi, B. White matter hyperintensities and alzheimer’s disease: an alternative view of an alternative hypothesis. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 4260–4261 (2023).

Garnier-Crussard, A. & Chételat, G. White matter hyperintensities in alzheimer’s disease: beyond (but not instead of) the vascular contribution. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 4262–4263 (2023).

Lorenzini, L. et al. Regional associations of white matter hyperintensities and early cortical amyloid pathology. Brain Commun. 4, fcac150 (2022).

Hampel, H. et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA): radiological, biological and clinical characteristics. Brain 146, 4414–4424 (2023).

Cummings, J. et al. Lecanemab: appropriate use recommendations. J. Prev. Alz Dis. 10, 362–377 (2023).

Beach, T. G. et al. Cerebral white matter rarefaction has both neurodegenerative and vascular causes and May primarily be a distal axonopathy. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 82, 457–466 (2023).

Erten-Lyons, D. et al. Neuropathologic basis of white matter hyperintensity accumulation with advanced age. Neurology 81, 977–983 (2013).

Schmidt, R. et al. Heterogeneity in age-related white matter changes. Acta Neuropathol. 122, 171–185 (2011).

Moscoso, A. et al. 18F-florbetapir PET as a marker of Myelin integrity across the alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 49, 1242–1253 (2021).

Ottoy, J. et al. Amyloid-PET of the white matter: relationship to free water, fiber integrity, and cognition in patients with dementia and small vessel disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 43, 921–936 (2023).

Lee, S. N., Woo, S. H., Lee, E. J., Kim, K. K. & Kim, H. R. Association between T1w/T2w ratio in white matter and cognitive function in alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 14, 7228 (2024).

Parent, O. et al. Assessment of white matter hyperintensity severity using multimodal magnetic resonance imaging. Brain Commun. 5, fcad279 (2023).

Pålhaugen, L. et al. Brain amyloid and vascular risk are related to distinct white matter hyperintensity patterns. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 41, 1162–1174 (2021).

Garnier-Crussard, A. et al. White matter hyperintensity topography in alzheimer’s disease and links to cognition. Alzheimers Dement. 18, 422–433 (2022).

Jung Keun-Hwa et al. Heterogeneity of cerebral white matter lesions and clinical correlates in older adults. Stroke 52, 620–630 (2021).

Duering, M. et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease—advances since 2013. Lancet Neurol. 22, 602–618 (2023).

Wardlaw, J. M. et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 12, 822–838 (2013).

Jiaerken, Y. et al. Microstructural and metabolic changes in the longitudinal progression of white matter hyperintensities. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 39, 1613–1622 (2019).

Dadar, M., Maranzano, J., Ducharme, S. & Collins, D. L. White matter in different regions evolves differently during progression to dementia. Neurobiol. Aging. 76, 71–79 (2019).

Melazzini, L. et al. White matter hyperintensities classified according to intensity and Spatial location reveal specific associations with cognitive performance. Neuroimage Clin. 30, 102616 (2021).

Nowaczyk, N. et al. Spatial distribution of white matter degenerative lesions and cognitive dysfunction in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 53, 18–25 (2019).

Gouw, A. A. et al. Heterogeneity of white matter hyperintensities in alzheimer’s disease: post-mortem quantitative MRI and neuropathology. Brain 131, 3286–3298 (2008).

Kalheim, L. F. et al. Amyloid dysmetabolism relates to reduced glucose uptake in white matter hyperintensities. Front Neurol 7 (2016).

Gaubert, M. et al. Topographic patterns of white matter hyperintensities are associated with multimodal neuroimaging biomarkers of alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 13, 29 (2021).

Brickman, A. M. et al. Reconsidering harbingers of dementia: progression of parietal lobe white matter hyperintensities predicts alzheimer’s disease incidence. Neurobiol. Aging. 36, 27–32 (2015).

Gaubert, M. et al. Performance evaluation of automated white matter hyperintensity segmentation algorithms in a multicenter cohort on cognitive impairment and dementia. Front Psychiatry 13 (2023).

Moscoso, A., Grothe, M. J. & Schöll, M. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging Initiative. Reduced [18F]flortaucipir retention in white matter hyperintensities compared to normal-appearing white matter. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 48, 2283–2294 (2021).

Besson, F. L. et al. Cognitive and brain profiles associated with current neuroimaging biomarkers of preclinical alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 35, 10402–10411 (2015).

La Joie, R. et al. Region-Specific hierarchy between Atrophy, Hypometabolism, and β-Amyloid (Aβ) load in alzheimer’s disease dementia. J. Neurosci. 32, 16265–16273 (2012).

Petersen, R. C. et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch. Neurol. 58, 1985 (2001).

McKhann, G. et al. Clinical diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of department of health and human services task force on alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 34, 939–944 (1984).

Schmidt, P. Bayesian Inference for Structured Additive Regression Models for large-scale Problems with Applications To Medical Imaging (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, 2017).

Hammers, A. et al. Three-dimensional maximum probability atlas of the human brain, with particular reference to the Temporal lobe. Hum. Brain Mapp. 19, 224–247 (2003).

André, C. et al. Brain and cognitive correlates of sleep fragmentation in elderly subjects with and without cognitive deficits. Alzheimers Dement. 11, 142–150 (2019).

Jack, C. R. et al. Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 13, 205–216 (2017).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr Res. 12, 189–198 (1975).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to G. Rauchs, E. Arenaza-Urquijo, A. Bejanin, C. Tomadesso, S. Egret, M. Fouquet, R. La Joie, R. De Flores, M. Leblond, C. Malle, K. Mevel, J. Mutlu, V. Ourry, A. Pelerin, A. Perrotin, G. Poisnel, S. Segobin, N. Villain, A. Manrique, L. Paly, E. Touron, I. Moulinet, S. Rehel, S. Dautricourt, V. Lefranc, A. Cognet, F. Viader, M. Gaubert, A. Abbas, L. Barré, D. Guilloteau, F. Pasquier, S. Belliard, (A) Lutz, F. Eustache, (B) Desgranges and the Cyceron MRI-PET staff members, and to the participants of the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicale (INSERM), the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (PHRCN 2011-A01493-38 and PHRCN 2012 12-006-0347), the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR LONGVIE 2007), Fondation Plan Alzheimer (Alzheimer Plan 2008–2012), Fondation LECMA-Vaincre Alzheimer (grant no. 13732), Association France Alzheimer et maladies apparentées, the Région Basse-Normandie, the Agence régionale de santé Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (grant 667696). Funding sources were not involved in the study design, data acquisition, analysis, and manuscript writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AGC and GC contributed to the study concept and design. AGC, BL, FM, JG, DR, GC took part in the acquisition and processing of the data, and quality check control. Analysis and interpretation of MRI data were done by AGC, BL, FM, FC and GC. AGC, BL and FM contributed to the statistical analysis. AGC and GC drafted the manuscript. AGC, GC and FC interpreted the findings. GC was the study supervisor. All authors took part in revising the manuscript for content. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No disclosure to report.Independent of this work, A.G.-C. is an unpaid sub-investigator or local principal investigator in NCT04867616 (UCB Pharma), NCT04241068 (Biogen), NCT05310071 (Biogen), NCT03446001 (TauRx Therapeutics), NCT03444870 (Roche), NCT04374253 (Roche), NCT04777396 (Novo Nordisk), NCT04777409 (Novo Nordisk), NCT04770220 (Alzheon), NCT05423522 (Medesis Pharma), NCT06079190 (GlaxoSmithKline).Independent of this work, F.C. has received consulting and lecturing fees, travel grants and unconditional research support from Alexion, Biogen, Bracco, Guerbet, Philips Medical imaging, Novartis, Telediag and Roche.Independent of this work, G.C. has received research support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement number 667696), Fondation d’entreprise MMA des Entrepreneurs du Futur, Fondation Alzheimer, Région Normandie, Association France Alzheimer et maladies apparentées, Fondation Vaincre Alzheimer, Fondation Recherche Alzheimer, Fondation Bettencourt Schueller and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (all to Inserm), and personal fees from Fondation Alzheimer and Lilly.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garnier-Crussard, A., Landeau, B., Mezenge, F. et al. Heterogeneity of white matter hyperintensities in Alzheimer’s disease captured by multimodal neuroimaging. Sci Rep 15, 38433 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23371-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23371-7