Abstract

In warm and dense plasmas (WDP), ionization potential depression (IPD) plays a crucial role in determining the ionization balance and in understanding the resulting microscopic properties of the plasma. However, the applicability of widely used IPD models, such as the Stewart-Pyatt (SP) and Ecker-Kröll (EK) models, are found to be limited under such conditions. In WDP, the Coulomb potential of neighboring ions directly influences the screening potential around a target ion, thereby altering its ionization potential (IP). Moreover, similar to solid state systems, outer atomic orbitals expand into continuous energy bands due to the influence of neighboring ions and plasma electrons. Electrons can populate into these bands through inelastic collision processes, which will further contribute to the screening potential. Electrons in these continuous bands can migrate into neighboring ions and become delocalized. Consequently, even with total energy E < 0, electrons excited into these bands can be considered as ionized, a behavior distinct from that in isolated situations. In our previous work, using an atomic-state-dependent screening model, we incorporated the influence of band electron distributions resulting from inelastic collisions and found significant contributions to the screening potential under WDP conditions. We now extend this framework by including the effects of neighboring ions on both the screening potential and ionization conditions. This extension reveals that neighboring ions substantially affect IPD in WDP and lead to a weaker temperature dependence compared to cases where such influences are neglected. These findings suggest a potential competitive mechanism between the contributions from band electrons considered in the screening potential and those from direct Coulomb potential of neighboring ions. Furthermore, we discuss how to identify atomic shells that have expanded into bands and should be included in the screening and ionization treatments across a broader range of plasma conditions. The proposed model shows good agreement with experimental results for Al, Mg, and Si plasmas over a wide range of temperatures (18–700 eV) and densities (1–3 times solid density), including measurements of hollow Al ions. With low computational cost and broad applicability, this model offers a promising tool for studying ionization balance, atomic processes, and related radiation and particle transport properties in WDP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Warm and dense plasmas (WDP) widely exists in stars or giant planets1,2 and can be created in experiments with high-power lasers and Z pinches3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. For atoms embedded in a dense plasma, atomic parameters are significantly influenced by the plasma screening due to complicated many-body interactions with the surrounding plasma12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Ionization potential depression (IPD) is one of the most important phenomena of plasma screening. In dense plasma, IPD can significantly alter the ionization balance22,23,24 and further impact several critical optical and thermodynamic properties of the plasma, such as opacity and equation of state (EOS)25,26. Therefore, accurate IPD is fundamentally important for research in astrophysics, inertial confinement fusion, and the study of matter under extreme conditions.

Owing to the quantum many-body correlations between electrons and ions, an accurate description of IPD in dense plasma is extremely complicated. For practical applications, semi-empirical models such as the Stewart-Pyatt (SP)4,5,27 and Ecker-Kröll (EK)6,28 models have been proposed and widely adopted in the numerical modeling and analysis of plasma since the 1960s. Recently, the development of X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) has enabled precise laboratory measurements of IPDs4,5. However, experiments conducted in solid-density Al plasmas revealed that the SP model underestimates IPD, while the earlier EK model shows better agreement with the measurements4. Moreover, subsequent measurements across a wider range of elements and plasma conditions indicate clear deviations of both the EK and SP models from experimental results5,6. Owing to the discrepancy between experiments and theory, a more fundamental understanding of WDP is urgently needed. Therefore,, a series of advanced models have been developed to address the complexity of quantum many-body interactions in plasma. These models aim to capture essential plasma characteristics within specific parameter ranges while maintaining a balance between computational tractability and physical accuracy.

Models such as finite-temperature density functional (DFT) simulations29,30, classical molecular dynamics simulations31,32 and quantum statistical models33,34,35,36 are primarily based on quantum statistical theory from an ensemble perspective, focusing mainly on the dielectric function that characterizes the system response and its closely related dynamic structure factor. However, interactions in plasma are often treated with substantial approximations to manage computational complexity, and most models are restricted to local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE) conditions, thereby limiting their applicability to non-LTE plasma regimes. Furthermore, these models are burdened by high computational costs, and accurate treatment of ions in highly excited states remains challenging.

In contrast to ensemble-based approaches, a distinct category of plasma models employs single-atom approximation. These include the Debye–Hückel (DH) model37, two-step Hartree–Fock (HF) model38, self-consistent ion sphere (IS) model23,39, atomic‒solid‒plasma models40, generalized ion-sphere model41,42 and our recently established atomic-state-dependent screening model43,44. In these models, detailed atomic configurations and complicated many-body correlations and dynamic atomic processes in ions can be included; thus, the influence of plasma electrons that deviate from LTE conditions can be discussed. Compared to models based on quantum statistical theory, models based on single-atom approximation have lower computational costs and offer better flexibility in application. Notably, the theoretical connection between these two classes of models is established through quantum statistical theory. Specifically, the DH model emerges as a limiting case within the random phase approximation (RPA) framework under static conditions33, thereby bridging single-atom models with more fundamental quantum statistical treatments.

In a plasma environment, an ion is influenced by other ions and electrons. Under WDP conditions, the distances between ions become small, making the effect of neighboring ions on the target ion important. The influence of neighboring ions can be categorized into three interrelated parts:

-

1.

The Coulomb potential from neighboring ions directly affects the screening potential around the target ion.

-

2.

Due to the presence of surrounding ions and plasma electrons, the outer atomic orbitals of the target ion expand into continuous energy bands, which is similar to the situation in solid-state systems45,46. Through processes such as three-body recombination (TBR), dielectronic recombination (DR), and other inelastic electron–ion collisions, plasma electrons can temporarily recombine and populate into these continuous bands44. These band electrons contribute to plasma screening. Moreover, owing to their continuous energy distribution, Even when their total energy \({{E}} < \text{ 0}\), their contribution to screening is difficult to be distinguished from that of free electrons with \({{E}}\text{ > 0}\), and should be included in the overall screening potential.

-

3.

As the wavefunctions of electrons in these continuous bands remain significantly non-zero at the boundary of the target ion, such electrons can migrate into neighboring ions and become delocalized47. Consequently, electrons excited into these bands can be considered as ionized even with total energy \(E < 0\)45, which contrasts with the case in isolated situation, where ionization typically requires excitation to states with \(E>0\).

The influence of neighboring ions has been partially or comprehensively incorporated in models such as density functional theory (DFT)29,30, classical molecular dynamics simulations31,32, and quantum statistical models33,34,35,36. However, in conventional single-atom approximation models such as the DH or self-consistent ion-sphere models, despite their computational efficiency, the effect of neighboring ions is not explicitly accounted for. The two-step Hartree–Fock (HF) model attempts to address changes in ionization conditions in dense plasma by introducing an “inner-ionization” correction to IPD38, it does not consider the delocalization of electrons within continuous energy bands, which may lead to an underestimation of the ionization condition shift. In the recent developed generalized ion-sphere model41,42, continuous bands are treated as a bound-free mixture. Electrons in these bands contribute to the screening potential, and those excited into these valence-band-like structures are regarded as a mixture of both excitation and ionization. This model achieves excellent agreement with solid-density experiments41,42. However, it assumes a fixed distribution of band electrons across different channels, similar to the neutral atom approximation discussed in Ref. 5. Such band electrons distribution is independent of temperature. Consequently, the model exhibits negligible temperature dependence. Moreover, IPDs are derived by including all channels and related transitions. But in broader plasma conditions, the channels and related transitions may become complicated, which will limit the application of the model in wider plasma conditions.

In our recent works on atomic-state-dependent screening model43,44, the contribution of band electrons is described using a temperature-dependent non-LTE distribution, rather than a fixed distribution in the generalized ion-sphere model. As a result, the computed IPDs show a stronger temperature dependence. Nevertheless, none of the above single-atom approximations fully incorporates the direct Coulomb potential from neighboring ions into the target ion’s screening potential. Furthermore, the effect of this direct interaction on temperature dependence remains unexplored. Additionally, a criterion for identifying atomic shells that have expanded into bands and should therefore be included in the screening potential in extended density and temperature regimes is still absent. These limitations may restrict the applicability of current models to a wider range of plasma conditions.

In this work, we refine the atomic-state-dependent screening model by incorporating the direct contribution of neighboring ions to the screening potential and accounting for changes in ionization conditions caused by neighboring ions. Furthermore, in wider plasma conditions, the identification of atomic shells that have expanded into continuous bands and should be considered in both the screening potential and ionization condition is also discussed in this work. The developed model is successfully validated by accurately reproducing the IPD values from recent experiments on Al, Mg, and Si plasmas across a wide range of temperatures (18–700 eV) and densities (1–3 times solid density), as well as measurements of hollow Al 1 s ions4. Our results demonstrate the important role of neighboring ions and the change of ionization condition in determining IPD in WDP. Compared to existing experimental data and other analytical or more complex models, our approach captures plasma characteristics across a wider range of conditions and can be applied to ions in highly excited states, such as hollow ions. With its computational efficiency and broad applicability, the model provides a practical tool for studying IPD in WDP, thereby supporting future research on radiation and particle transport properties.

Theory and calculation method

In a dense plasma environment characterized by electron temperature \(T_{e}\) and average plasma electron density \(n_{0}\), which can be calculated as \(n_{0} = \overline{Q} \times n_{i}\), with the average ionization degrees \(\overline{Q}\) and the density of ions \(\it {\text{n}}_{\text{i}}\), electrons around ions experience a screening potential arising from the target ion, bound and plasma electrons, and other ions. In this work, we include the direct Coulomb potential from neighboring ions in the screening potential. Similar to the Thomas–Fermi model, we treat the plasma background as overlapping uniform charge distributions of positive and negative charges, each with density \(\it {\text{n}}_{0}\). By introducing the target ion and its neighboring ion into this background, electrons redistribute under the combined influence of these ions, while the positive charges are treated as stationary due to their large mass. The resulting screening potential \(\it {\text{V}}_{\text{scr}}\) satisfies the following Poisson equation (in atomic units unless stated otherwise):

Here, \(\it {\text{Z}}\) and Z′ are the nuclear charge number of target and neighboring ion, respectively. \(n_{b}\) and \(n_{b}\), are the density distribution of bound electrons of target and neighboring ion, respectively. \({n}({\bf{r}})\) is the redistributed plasma electron density, \(\it {\text{n}}_{0}\) in Eq. (1) is the uniform positive charge backgrounds. \({{R}}\) is the distance between target and neighboring ions, the influence from neighboring ions is highly sensitive to the distance \({{R}}\), while in present work, we mainly consider the statistical average influence from neighboring ions, so the distance between ions \({{R}}\) is chosen as two times of the Wigner–Seitz radius as \(R = 2\left( {\frac{3}{{4\pi n_{i} }}} \right)^{1/3}\).

In the region near the target ion, the Coulomb potential of the target ion dominates the screening potential. The direct contribution from neighboring ion can be treated as a residual Coulomb potential outside the region where neighboring ion dominates. Within the mean-field approximation and accounting for the influence of neighboring ion, the screening potential around the target ion can be expressed as:

here, \({{r}}_{0}\) is the distance where \({{V}}_{{scr}}\) has the maximum value between the target and neighboring ions, which can be viewed as the boundary of the target and neighboring ion. The third term in Eq. (2) is the residual Coulomb potential from neighboring ion, and \({{Z}}_{{n}}\) is the effective residual charge number of neighboring ion, which can be calculated as \(Z_{n} = Z ' - \mathop \smallint \limits_{0}^{{R - r_{0} }} [n_{b} ' (\bf{r'} ) + n_{n} (\bf{r'}) - n_{0} ]\bf{dr'}\), with \({{n}}_{{n}}\) the the redistributed plasma electron density around neighboring ion. It can be found in Eq. (2), the exchange terms between plasma electrons and bound electrons are not included, since as discussed in Ref. 41 and 48, the contribution from these terms is small. In dense plasma environment, there will be several neighboring ions around the target ion; for simplicity, the screening potential is approximated as spherically symmetrical as \({\bf{r}} \to {{r}}\) and \({\bf{|R}} - {\bf{r|}} \to {{|R}} - {{r|}}\) in present work.

The ionization degree of neighboring ions \({{Q}}_{{n}}\) used in the calculations will decide the \({{n}}_{{b}}{'}\) around the neighboring ion, and also affects the screening potential. In a plasma environment, neighboring ions in different ionization degrees coexist. To account for the average influence of neighboring ions, the average ionization degree \(\overline{Q}\) under the given plasma conditions should, in principle, be adopted directly as the ionization degree of the neighboring ions \({{Q}}_{{n}}\). However, since the average ionization degree \(\overline{Q}\) is usually non-integer, its direct use would complicate the computation of bound-state orbitals of neighboring ions. Therefore, for computational convenience, the average ionization degree \(\overline{Q}\) is rounded to the nearest integer and used as the ionization degree of the neighboring ions \({{Q}}_{{n}}\).

The plasma electron density distribution \({{n}}\text{(}{{r}}\text{)}\) relate to the screening potential in Eq. (2). When the plasma environment reaches equilibrium, the plasma electron density \({{n}}\text{(}{{r}}\text{)}\) can be written as

where \(f_{FD} = {1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 {\left[ {\exp \left[ {\left( {\varepsilon + V_{scr} - \mu } \right)/T_{e} } \right] + 1} \right]}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left[ {\exp \left[ {\left( {\varepsilon + V_{scr} - \mu } \right)/T_{e} } \right] + 1} \right]}}\) is the Fermi‒Dirac distribution, \(\varepsilon\) is the kinetic energy of electrons, \(\varepsilon_{0}\) is the lower limit of \(\varepsilon\), which can be decided as \(\varepsilon_{0} = E_{\min } - V_{scr} \left( r \right)\), with \({{E}}_{{\min}}\) the lower limit of the total energy of the electron that have been considered in the plasma screening, and \(\mu\) is the chemical potential, which can be determined by \({{n}}_{0}\).

In most of the present plasma models, only electrons with total energy \({{E }} = \varepsilon + {{V}}_{{{{scr}}}} \left( {{r}} \right) > {0}\) are considered, i.e. \({{E}}_{\min}= \text{0}\). However, in a dense plasma environment, similar to solid-state systems, outer atomic orbitals expand into continuous energy bands due to the influence of neighboring ions and surrounding electrons45,46, plasma electrons can temporarily recombine with ions and distribute into these continuous band even with \({{E}}\text{ < 0}\) through the TBR, DR and other inelastic collision processes between electrons and target ions. These band electrons also contribute to the screening potential in Eq. (3). Therefore, in present work, the lowest shell that has merged into continuum is considered to have expanded into continuous energy bands. Electrons distributing in this shell are included in the screening potential, and the orbital energy of this shell is selected as the lower limit of the total energy \({{E}}_{\min}\).

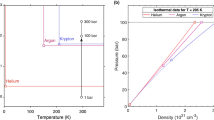

On the other hand, as illustrated in Fig. 1, the ionization conditions change in a dense plasma environment38,41,45,46. As presented in Fig. 1a, in an isolated ion, electrons excited into states with \({{E}}\,{ > 0}\) are considered as ionized. However, in a dense plasma environment, under the influence of plasma electrons and neighboring ions, the ionization potential (IP) becomes lower than that of an isolated ion. As depicted in Fig. 1b, earlier models define a region around the ion using the Wigner–Seitz radius \(r_{s} = \left( {\frac{3}{{4\pi n_{i} }}} \right)^{1/3}\), at the boundary of the ion, the screening potential \(V_{scr} (r_{s} ) < 0\), electrons excited into states with \(V_{scr} (r_{s} ) < E < 0\) are so called “inner ionization” and are treated as ionized38. Nevertheless, as presented in Fig. 1c, the presence of neighboring ions causes the outer orbitals of the target ion to expand into continuous bands. Electrons excited in these bands can migrate into neighboring ions and become delocalized, which is similar to behavior in solid materials. Therefore, even when their total energy \(E < V_{scr} (r_{s} )\), electrons excited into these bands can be considered as ionized41. Neglecting this delocalization effect may cause the “inner-ionization” picture to underestimate the contribution of ionization condition changes in IPD calculation.

(a) Schematic of ionization in an isolated ion. (b) “Inner ionization” in dense plasma. (c) Influence of neighboring ions on the target ion in WDP. The outer orbitals of the target ion expand into continuous bands, and electrons excited into these continuous energy bands become delocalized and can be considered as ionized41.

In present work, the lowest shell that have merged into continuum is considered as a continuous energy band, and electrons excited into this shell are considered as ionized. IPD of ions in ground states can be calculated as

where \(I_{0}\) is the IP in absence of plasma outside, \({{E}}_{{{1}{{s}}}^{2}}\) is the energy of the ground state and \({{E}}_{{1}{{snl}}}\) is the energy of the delocalized state with one electron have been excited into the continuous energy band nl. Here, \({{E}}_{{{1}{{s}}}^{2}}\) and \({{E}}_{{1}{{snl}}}\) can be obtained by applying a Multi-Configuration Dirac Fock (MCDF) calculation49, the related N-electron Hamiltonian can be written as

where \(H_{D} = c\alpha \cdot p + (\beta - 1)c^{2} + \left[ {V_{scr} - \mathop \smallint \limits_{0}^{{r_{0} }} \frac{{n_{b} }}{{\left| {\bf{r - r'} } \right|}}\bf{dr'} } \right]\) is the single-electron Dirac Hamiltonian under the screening potential. Here \(\mathop \smallint \limits_{0}^{{r_{0} }} \frac{{n_{b} }}{{\left| \bf{r - r' } \right|}}\bf{dr'}\) is subtracted in the single-electron Dirac Hamiltonian to avoid double-counting of the Coulomb potential between electrons. In the present calculation, we use the modified GRASP2K code50, which can include the screening potential to perform MCDF computations. The program is designed to solve the Dirac equation within a region larger than the actual influence radius \({{r}}_{0}\) of the target ion under the assumption of a single-center potential. However, the screening potential obtained in this work is only physically meaningful as a single-center potential within \({{r}}_{0}\). To incorporate this screening potential into the program, it must be extended from \({{r}}_{0}\) to the entire solution region required by GRASP2K. Therefore, as an additional approximation, we adopt a muffin-tin potential for the region beyond \({{r}}_{0}\), defined as \(V_{scr} (r \ge r_{0} ) = V_{scr} (r_{0} )\).

In the present calculations for Al, Mg, and Si plasmas at solid density and temperatures around 100 eV, as observed in experiments4,5, the M shell is the lowest shell that have merged into continuum, and the lowest orbital energy of the M shell is chosen as the lower limit of the total energy as \(E_{\min } = \varepsilon_{0} + V_{scr}\). Furthermore, an electron excited into the M shell is considered as ionized, and the corresponding IPDs are calculated using Eq. (4).

Before the calculation, based on temperature \({{T}}_{{e}}\) and density of ions \({{n}}_{{i}}\), the average ionization degree \(\overline{Q}\) should be decided, then the average plasma electron density \({{n}}_{0}\) and the ionization degree of neighboring ions \({{Q}}_{{n}}\) can be obtained. In present work, \(\overline{Q}\) is determined by solving the Saha-Boltzmann equations for detailed configuration accounting51,52. In this calculation, the energies of ions in different states are pre-calculated using the MCDF method without plasma screening. The IPs used in the calculation are derived from the difference in ground state energies between two adjacent ionization degrees and are then modified by IPDs. Theoretically, the IPDs used in the Saha–Boltzmann equation directly influence the ionization balance and further influence the \(\overline{Q}\) values. In principle, a self-consistent calculation simultaneously treating both IPD in present model and \(\overline{Q}\) is required. However, such calculations are relatively complex and, based on tests conducted at selected parameter points, such calculations are found to have limited corrections on the results. Therefore, this more computationally intensive approach was not adopted in the present work. The IPDs applied in the Saha-Boltzmann equations are obtained from the revised EK model (with \({{C}}_{{EK}} \, = \text{ 1}\))4 in solid density and \(T_{e} \le 150 \text{eV}\), or SP models in higher density or temperature conditions. Within these two ranges, the revised EK and SP models achieve better agreement with experiment5,6, respectively.

For most conditions considered here, specifically, at solid density and \({{T}}_{{e}}\) on the order of tens of eV, the degeneracy parameter \(\Theta = \frac{{T_{e} }}{{ \in_{F} }}\) is significantly greater than 1, where \(\in_{F} = \frac{{(3\pi^{2} n_{0} )^{2/3} }}{2}\) is the Fermi energy. Furthermore, as discussed in Ref. 46, non-LTE deviations remain limited under such conditions, and are not the primary focus of the present work, the Saha-Boltzmann equation remains applicable. However, for cases with solid density and \({{T}}_{{e}}\) of only a few eV, the Saha-Boltzmann equation overestimate \(\overline{Q}\). Under these conditions, it is appropriate to directly adopt \(\overline{Q}\) and average electron density of the solid states without relying on the Saha-Boltzmann equation.

After all parameters needed are obtained, we can begin the calculation of IPDs. In the first step, the atomic orbitals (AOs) of isolated ions are prepared by using the GRASP2K code with the MCDF framework. Then, the density of bound electrons \({{n}}_{{b}}\) can be obtained via AOs and the occupation numbers of ion as:

where N is the number of orbits, \({\text{N}}_{\text{i}}\) is the occupation number of each orbit, \({{P}}_{{i}}{(}{{r}})\) and \({{Q}}_{{i}}{(}{{r}}{)}\) are the large and small components of AOs, respectively. In the second step, \({{n}}_{{b}}\) is substituted into Eq. (2), the initial trial plasma electron density around target and neighboring ion \({{n}}{(}{{r}}{)}\) and \({{n}}_{{n}}{(}{{r}}{)}\) can be chosen as 0, then the effect potential with only the influence of the bound electrons of target and neighboring ions \({{V}}_{{b}}\) is obtained. In the third step, we substitute \({{V}}_{{b}}\) as the trial solution into Eq. (3), and a plasma electron density \({{n}}{(}{{r}}{)}\) and \({{n}}_{{n}}{(}{{r}}{)}\) related to \({{V}}_{{b}}\) can be calculated from Eq. (3). By substituting \({{n}}{(}{{r}}\text{) and }{{n}}_{{n}}{(}{{r}}{)}\) into Eq. (2), a new screening potential \({{V}}_{{scr}}\) is obtained. \({{V}}_{{scr}}\) is substituted into Eq. (3), and the second and third steps are repeated until \({{V}}_{{scr}}\) converges. Finally, IPDs can be obtained by substituting the converged \({{V}}_{{scr}}\) into an MCDF calculation with Hamiltonian in Eq. (5). With the energy of target ion in different states is obtained, IPDs can be calculated by applying Eq. (4).

In the present calculation, due to the selection rules, only np orbits in the delocalized shell are considered. It should be noted that transitions from 1 s to nl states with \({{l }} \ne {1}\) are also possible due to Stark mixing in dense plasmas41. We also try to include ns orbitals in the delocalized shell. The resulting IPD values showed slight numerical discrepancies compared to those obtained with np orbitals, though these differences do not affect the final conclusions or the agreement with experiments. On the other hand, multiple detailed 1snp delocalized states arise from various angular momentum coupling schemes between the electrons. For simplicity, the lowest dipole-allowed delocalized state is selected for IPD calculation in this work.

Notably, AOs are also influenced by the screening potential. But under the present density and temperature conditions, the Debye length \({{D}}\)18, which characterizes the spatial range of plasma screening remains much larger than the radius of the K and L shells. Therefore, the effect of plasma screening on the AOs is limited and has been neglected in this work. Compared to other more sophisticated IPD models, the computational cost of our model depends on the desired precision. In the present implementation, a single ionization degree can be computed within seconds using a single thread on a personal computer.

To validate the influence of neighboring ions, the effective screening potentials \({{V}}_{{scr}}\) of the Al3+, Al6+ and Al9+ ions in ground states with and without the influence of neighboring ions at solid density and Te = 100 eV are presented in Fig. 2. In such condition, the average ionization degree \(\overline{Q}\) is about \(\text{8.7}\), thus Al9+ ions are chosen as the neighboring ions. The density of ions \(n_{i} = 6.02 \times 10^{22} \text{cm}^{ - 3}\) is derived from the solid density of Al \((\rho = 2.7 \text{g}/\text{cm}^{3} )\) and its molar mass (\(\text{27 g/mol}\)), the average free electron density \(n_{0} = 5.23 \times 10^{23} \text{cm}^{ - 3}\). For comparison, the direct contribution from neighboring ions, which is represented by the third term in Eq. (2) is neglected in the calculation without the influence of neighboring ions. As shown in Fig. 2, neighboring ions significantly influence the screening potential, particularly near the boundary of the target ion. Specifically, at the distance \({{r}}{ = }{{r}}_{{s}}\), the screening potential including the influence of neighboring ions is significantly lower than that without the influence of neighboring ions.

Under such conditions, the radial wave functions y(r) of the M shell are calculated. As an example, Fig. 3a shows y(r) of Al6+ in the [1s2s22p33l] configuration. At the boundary of the target ion, the radial wave function y(r0) of the M shell orbital remains significantly non-zero, indicating that electrons occupying these orbitals can migrate into neighboring ions and become delocalized47. In the present model, electrons excited into the delocalized shell are considered as ionized45, even though their total energy is probably lower than \(V_{scr} (r_{s} )\). As illustrated in Fig. 3b, under such conditions, the IPD includes two components: the change in orbital energy of the 1s orbital, and the change in ionization conditions. Consequently, the inclusion of neighboring ions directly affects both the screening potential and the ionization conditions.

Results and discussion

The present model is first applied to calculate the IPD under plasma conditions corresponding to the LCLS experiments, where the ion density \({{n}}_{{i}}\) is close to that of solid materials and the electron temperature \({{T}}_{{e}}\) ranges from 70 to 180 eV. We initially compute the IPDs of Al, Mg, and Si ions in their ground states at Te = 100 eV and solid density using the present model, and compare the results with experimental data, as shown in Fig. 4. The density of ions \({{n}}_{{i}}\), the average density of free electrons \({{n}}_{0}\) and the ionization degree of neighboring ion \({{Q}}_{{n}}\) applied in present calculation are also presented in the figure. To evaluate the influence of neighboring ions, IPDs calculated without their contribution are included in Fig. 4. In these calculations, the direct contribution from neighboring ions, i.e., the third term in Eq. (2) is omitted from \({{V}}_{{scr}}\), and the “inner-ionization” criterion is applied. Such IPDs are evaluated as \(\Delta I_{0 } = \langle \Psi |V_{scr} - V_{iso} |\Psi\rangle - V_{scr} (r_{s} )\), where \(\left| {\Psi\rangle } \right.\) represents the AO of 1 s electrons. As discussed earlier, the effect of plasma screening on inner orbitals is negligible; thus, for simplicity, the AOs are computed in the absence of plasma screening. Here, \({{V}}_{{iso}}\) denotes the effective potential for an isolated ion, and an electron is considered as ionized when its energy exceeds \({{V}}_{{scr}}\left({{r}}_{{s}}\right)\), following the “inner-ionization” concept38. For comparison, IPDs obtained from the SP model, the revised EK model (with \({{C}}_{{{EK}} \, }= \text{ 1}\))4, and the recent generalized ion-sphere model41 in the same conditions are also presented.

IPD calculated in the present model and comparison with the LCLS experiment. (a), (b), (c): IPDs of Mg, Al and Si ions with solid density and \({{T}}_{{e}}\text{ = 100 eV}\), respectively. \(\Delta I\) represents the results of the present model, and \(\Delta I_{0}\) represents the results without the influence from neighboring ions in \({{V}}_{{scr}}\) and uses the widely applied “inner-ionization” conditions. For comparison, results from SP, revised EK4 and the recent generalized ion-sphere models41 in the same conditions are presented in the figure..

As shown in Fig. 4a–c, the IPDs calculated with the present model show good agreement with the experimental results4,5. In contrast, when the contribution from neighboring ions is neglected, the results \(\Delta I_{0}\) are evidently lower than the experimental range, indicating an underestimation of the IPDs under these conditions. These findings highlight the importance of incorporating the influence of neighboring ions. For comparison, the SP model fails to reproduce the experimental data, whereas the revised EK model exhibits better agreement, consistent with earlier studies5. On the other hand, the recent generalized ion sphere model provides very good agreement within the experimental error bars41.

During the experiments, the plasma temperature increases continuously, leading to corresponding changes in the ion population distribution across different ionization degrees. Consequently, the IPDs for each ionization degrees should be associated with a specific temperature. However, it is not trivial to establish a distinct temperature corresponding to ions in each ionization degrees. Experimentally, neither the temporal evolution of the temperature nor the ion populations were directly measured, these quantities can currently only be inferred through simulations. For example, Ref 3. simulated the temperature variation as a function of incident laser photon energy, while Ref. 5 simulated the characteristic temperatures at which the average ionization degree equals specific ionization degrees. Ref. 46 simulated the characteristic temperatures at which the population of each ionization degree peaks, and found that the average ionization degree at that point nearly coincides with the corresponding specific ionization degree. Therefore, the temperatures associated with the average ionization degree can be considered equivalent to those corresponding to the peak populations of ions in individual ionization degrees. Based on the simulations from Ref. 46, the generalized ion sphere model is applied to calculate the IPDs of Al ions in different ionization degrees under different temperatures, and excellent agreement with experiment is achieved in such conditions41.

However, in LCLS experiments, when the incident photon energy is exactly at the experimentally observed K-edge position, a K-shell electron is firstly excited into the continuous energy bands by the laser. The subsequent filling of the K-shell hole occurs via Auger decay or radiative transitions from the L-shell. Alternatively, as discussed in Ref. 42, the electron excited into the energy band may retain bound-state characteristics and can decay back to the K-shell, emitting a Kβ photon in a resonant process. Among these decay channels, the radiative decay from the L-shell corresponds to the Kα emission observed in experiment, and the Kα emission is used to measure the K-edge of ions. Throughout this process, the intensity of the Kα emission is directly proportional to the population of ions with a K-shell hole. Since these hollow ions are produced through photoionization of ground-state ions, their population is, in turn, proportional to the product of the ground state ion population and the incident laser intensity. Therefore, the observed Kα emission intensity is also proportional to the product of the ground state ion population and the laser intensity. Consequently, both the incident laser intensity and the ion population should be taken into account.

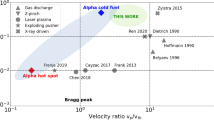

Here we choose the Kα emission of Al3+ in the ground state as an example. In solid Al at room temperature, the ions can be considered as triply ionized, thus, the peak population of Al3+ occurs at the beginning of the laser pulse. The laser pulse can be viewed as exhibiting a Gaussian intensity profile, meaning the intensity is relatively weak at the beginning of the pulse. As a result, although the Al3+ population peaks at the beginning of the pulse, the Kα emission intensity does not reach its maximum at that time. As shown in Fig. 5, we extract the temporal evolution of temperature for an incident photon energy of 1580 eV from Ref. 3 and calculate the evolution of the populations of Al ions in different ionization degrees under this temperature using a quasi-equilibrium assumption. By calculating the product of the population of Al3+ and the intensity of incident laser with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 80 fs, we estimate the temperature corresponding to the peak of Kα emission intensity.

(a) The temporal evolution of temperature with 1580 eV incident photon energy extracted from Ref. 3. (b) The temporal evolution of the population of Al3+ ions, the relative laser pulse intensity with a FWHM of 80 fs, and the relative signal intensity of the Kα emission.

This estimation method can be applied to ions in other ionization degrees. In the present work, the temporal temperature evolution corresponding to an incident photon energy of 1580 eV is applied to Al3+ and Al4+, the evolution corresponding to an incident photon energy of 1630 eV is used for Al5+ and Al6+, the evolution corresponding to an incident photon energy of 1680 eV is applied to Al7+ and Al8+, and the evolution corresponding to an incident photon energy of 1730 eV is applied to Al9+3. The temperatures corresponding to the peak Kα emission intensity are estimated as \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{1 }= \left[\text{18 eV, 30 eV, 44 eV, 58 eV, 73 eV, 91 eV, 110 eV}\right]\) for Al3+ to Al9+, respectively. The IPDs of Al at these temperatures and solid density are calculated, and the results are presented in Fig. 6. For comparison, IPDs of Al with solid density and \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{2} \, = \left[\text{4 eV, 29 eV, 38 eV, 51 eV, 67 eV, 87 eV, 110 eV}\right]\) simulated in Ref. 5 and \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{3 }= \left[\text{8 eV, 30 eV, 42.5 eV, 58 eV,82 eV, 104 eV, 132 eV}\right]\) simulated in Ref. 46 are also calculated and presented. Additionally, results from the generalized ion sphere model under conditions of \({\left[{\text{T}}_{\text{e}}\right]}_{3}\) and solid density41 are also provided for reference.

IPDs of Al ions calculated in present model with solid density and \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{1}\) relate to the peak intensity of the Kα emission, \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{2}\) relate to the peak population of each ions simulated in Ref. 5, \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{3}\) relate to the peak population of each ions simulated in Ref. 46. The results from generalized ion sphere model with solid density and \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{3}\)41 are also presented for comparison.

In the present calculations, both \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{2}\) and \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{3}\) correspond to the peak population of ions in each ionization degrees, in such conditions the average ionization degree is nearly equal to the ionization degree of the target ions. Thus the neighboring ions are assigned the same ionization degree as the target ion. The average plasma electron density \({\text{n}}_{0}\) is taken as the product of the ionization degree of target ion and the ion density \({{n}}_{{i}}\). It is observed that \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{1}\) exhibits values similar to \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{2}\) for all ions except Al3+. Therefore, the same computational scheme is applied to \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{1}\) for ions except Al3+. For Al3+, the average ionization degree \(\overline{Q} \, \text{= 3.3}\), the ionization degree of neighboring ions is taken as \(Q_{n} = 3\), and \(n_{0} = 2.0 \times 10^{23} \text{cm}^{ - 3}\).

As shown in Fig. 6, for the temperatures \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{2}\) and \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{3}\) associated with the peak ion populations, the calculated IPDs for Al3⁺ are significantly higher than the experimental data, while the result for Al⁹⁺ under \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{3}\) is slightly lower. In contrast, the results obtained using the present model with \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{1}\) corresponding to the peak Kα emission intensity are in good agreement with experiments, with all values lying within the experimental error bars. It is also observed that the generalized ion sphere model, applied at solid density and \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{3}\), shows good agreement with experiments, performing even better than our model for low ionization degrees. Considering the weak temperature dependence of the generalized ion sphere model, the results at \({{T}}_{{{e}} \, }= \text{ 100 } {\text{eV}}\) and \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{3}\) are nearly identical. It can therefore be inferred that the generalized ion sphere model would also achieve good agreement with experiments when applied at \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{1}\).

A comparison of the temperatures in \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{1}\), \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{2}\) and \({\left[{{T}}_{{e}}\right]}_{3}\) reveals discrepancies between those associated with the peak Kα emission intensity and those corresponding to the peak ion population, particularly for Al3⁺. In our simulation, the temperature relateed to the peak Kα emission intensity is 18 eV, which is significantly higher than the values of 4 eV and 8 eV predicted in Ref. 5 and 41 for the peak population of Al3⁺ ions.

It should be noted that the current method for estimating the temperatures corresponding to the peak Kα emission intensity is relatively approximate. The quasi-equilibrium assumption does not hold strictly due to the ultrashort pulse duration of ~ 160 fs. A more precise description of the ion population evolution would require directly solving the time-dependent rate equations. However, accurately solving these equations is challenging and computationally expensive, as all the relevant rate coefficients are influenced by the plasma environment, which extends beyond the scope of the present work. And as discussed in Ref. 46, non-LTE deviations remain limited under these conditions, thus a quasi-equilibrium assumption in a rough estimation of the population evolution of ions can be adequate. Furthermore, the same study notes that due to the short duration of the XFEL pulse, the ionization balance lags behind the quasi-equilibrium value46. As shown in Fig. 5, a slower population evolution of Al3+ ions results in a higher temperature associated with the peak Kα emission intensity, which in turn leads to improved agreement between our calculations and the experimental data for Al3+.

The main purpose of the estimation is to demonstrate that using temperatures corresponding to the peak ion population in IPD calculations may potentially deviate from actual conditions, especially for ions in the lowest ionization degrees, such as Al3+, where such temperatures may be significantly underestimated. Moreover, even among temperatures derived from different simulations for the peak populations of ions in each ionization degrees, considerable discrepancies exist. We therefore recommend that further experiments incorporate more rigorous time-resolved analysis of Kα emission signals, along with direct measurements of temperature evolution, to accurately determine the plasma conditions relevant to IPD measurements.

As shown in Figs. 4 and 6, the recent generalized ion sphere model also obtains values within the experimental range under these conditions. As discussed above, the influence of neighboring ions on IPD can be categorized into three components: the Coulomb potential from neighboring ions directly affects the screening potential around the target ion; the outer orbitals of the target ion expand into continuous bands due to the surrounding ions and electrons, electrons distributed in these bands also contribute to the screening potential; the ionization criteria change relative to those in isolated systems, since electrons in these continuous bands become delocalized and can be considered as ionized. In the generalized ion sphere model, these continuous bands are treated as a bound-free mixture. Electrons occupying these valence-band-like structures contribute to the screening potential, and those excited into such states are viewed as mixture of excited and ionized41. Thus, the second and third components of the contributions from neighboring ions are effectively incorporated in this model. Moreover, the generalized ion sphere model assumes a fixed distribution of band electrons across channels, which may lead to a stronger screening potential compared to our model. Consequently, the generalized ion sphere model achieves excellent agreement with experimental results, even though the ion sphere model requires electrical neutrality within the ion sphere, neighboring ions can not affect the target ion via the direct contribution of the Coulomb potential.

Among the widely used analytical models, the revised EK model shows better agreement with experimental measurements under plasma conditions relevant to the LCLS experiments, whereas the SP model tends to underestimate the IPD under such conditions4,5. However, under the higher density and temperature conditions reported in the Orion experiment6, the revised EK model significantly overestimates the IPD, while the SP model exhibits relatively better agreement with the measurements6. In addition to the LCLS and Orion experiments, recent studies have reported IPD for Mg7+ ions at solid density and a temperature of \({{T}}_{{e}}= \text{75 eV}\)11,35. To further validate the present model, we also calculated the IPDs under plasma conditions corresponding to the Orion experiments. The results are presented in Table 1.

As presented in Table 1, under conditions where \(n_{0} = 3 \times 10^{23} \text{cm}^{ - 3} ,\) and \({{T}}_{{e}}\text{ = 75 eV}\), which are similar to the conditions of the LCLS experiments4,5, our results are close to those of the revised EK model, which are in good agreement with the measurements, while the SP model evidently underestimates the IPDs. However, at higher temperatures and densities, our model yields values closer to those of the SP model. Specifically, under the conditions reported in the Orion experiment53, we calculate the IPDs of Al11+ and Al12+ ions and compare with experiment. When the density of the plasma is \(\rho = 5.5 \text{g}/\text{cm}^{3}\), corresponding to \(n_{i} = 1.22 \times 10^{23} \text{cm}^{ - 3}\) and \({{T}}_{{e}}\text{ = 550 eV}\), the \(K\beta\) lines of both Al11+ and Al12+ remain observable, indicating that the M shells are still well bound. The IPDs under such condition are therefore expected to be lower than the IPs of the M shell, approximately 220 and 256 for Al11+ and Al12+ ions, respectively. Therefore, in the present calculation, the orbital energies of the N shell are selected as the lower limit of the total energy \({{E}}_{\text{min}}\), and electrons excited into the N shell are considered as ionized. Under this condition, our results are close to those of the SP model, and the calculated IPDs remain below the M-shell IPs, consistent with experimental observations. In contrast, the revised EK model significantly overestimates the IPDs under such conditions53.

When the density is increased to \(\rho = 9 \text{g}/\text{cm}^{3}\), corresponding to \(n_{i} = 2.00 \times 10^{23} \text{cm}^{ - 3}\) and \({{T}}_{{e}}\text{ = 700 eV}\), the \(K\beta\) lines of both Al11+ and Al12+ disappear in the experiment, indicating that the IPDs now exceed the M-shell IPs. Under these conditions, the SP model still predicts an IPD for Al12+ below the IP, suggesting a slight underestimation. In our model, because the M shells have merged into the continuum, the orbital energies of the M shell are used as the lower limit of the total energy \({{E}}_{\text{min}}\). As presented in Table 1, the IPDs calculated under these conditions exceed the M-shell IPs for both Al11+ and Al12+, which are in agreement with experimental observation. Overall, as evidenced by both Fig. 4 and Table 1, our model demonstrates broader applicability across diverse plasma conditions and improved consistency with experimental results4,5,6.by comparing to the traditional analytical SP and EK models.

In the LCLS experiments, after one K-shell electron is ionized, the residual K-shell electron of hollow ions can be further ionized by the incident laser. Then the resulting K-shell hole can be filled via Auger decay or radiative transitions from the L-shell, or through radiative decay from the energy band as discussed in Ref. 42. The radiative decay from the L-shell emits a Kα photon. The entire process can be expressed in two steps: (1)\(K^{1} L^{x} + \hbar \omega_{XFEL} \to K^{0} L^{x} + e\) and (2) \(K^{0} L^{x} \to K^{1} L^{x - 1} + \hbar \omega_{K\alpha }\), where \(\hbar \omega_{XFEL}\) is the incident XFEL photon, \(\hbar \omega_{K\alpha }\) is the emitted \(K\alpha\) photon and \({\text{e}}\) is the ionized electron from the K-shell. The Kα emission originating from the L-shell of such hollow ions have been experimentally observed, which offer a chance to determine the IPDs of hollow ions4,5,54. Compared to ground state ions, these hollow ions have very short lifetimes due to rapid Auger and radiative decay processes. As a result, the electron distribution around them may deviate from LTE conditions. The IPDs of such highly excited hollow ions cannot be accurately described by widely used analytical models such as SP or EK, which are not state-resolved. Similarly, it is difficult for DFT, as it primarily focuses on ground state ions.

To further validate the validity of present model, the IPDs of such hollow Al ions are calculated with the solid density \(n_{i} = 6.02 \times 10^{22} \text{cm}^{ - 3}\),\({{T}}_{{{e}} \, }= \text{ 70 eV}\), \(n_{0} = 4.43 \times 10^{23} \text{cm}^{ - 3}\). The ionization degree of neighboring ions is taken as \({{Q}}_{{n}}\text{ = 7}\), corresponding to the average ionization degree \(\overline{Q} = 7.4\) under such condition. The results are compared with experimental values. The experimental IPD values are derived by extracting the K-edge positions of hollow ions from Fig. 1 of Ref. 3, and then comparing them with the IPs of hollow ions in the absence of plasma screening, which are computed using the MCDF method in this work. The uncertainty in the experimental values is taken as 10 eV, consistent with the uncertainty assigned to IPDs of ground state ions. However, due to the much weaker signals observed for hollow ions, this uncertainty may be underestimated. The extracted K-edge values from the experiment, the corresponding MCDF calculated IPs, and the resulting experimental IPDs are summarized in Table 2.

A comparison between the IPDs calculated by the present model and the experimental values is presented in Fig. 7. It can be observed that our results show good agreement with the measurements. The slight discrepancies may originate from an underestimation of experimental uncertainties or from non-LTE electron distributions around these hollow ions, such as the selection effect of the pump laser44. These findings demonstrate that, in contrast to widely used SP and EK models or more sophisticated DFT methods, our model is state-resolved and can be effectively applied to compute highly excited ions.

Finally, to discuss the temperature dependence of the present model, we calculated the IPDs of Al3+, Al6+ and Al9+ in their ground states at solid density \(n_{i} = 6.02 \times 10^{22} \text{cm}^{ - 3}\) over a temperature range of 70 to 700 eV. For comparison, the experimental values5, results without considering the influence of neighboring ions \(\Delta I_{0}\), as well as those from the SP and revised EK models, are also calculated. The results are presented in Fig. 8. The same method used to obtain \(\Delta I_{0}\) in Fig. 4 is applied here.

IPD of Al3+, Al6+ and Al9+ ions as a function of temperature (from 70 to 700 eV) with respect to solid density and comparison with the results from experiment5, the SP and EK models.

As shown in Fig. 8, for lower ionization degrees, our results are close to those of the SP model, while for higher ionization degrees, our results lie between the SP and EK predictions. At lower temperatures, the present model exhibits evident temperature dependence, particularly for highly ionized ions. As temperature increases, however, the dependence becomes weak, and the variation tendency is similar to that of the SP model, which have a very weak temperature dependence. As indicated in our previous work, the temperature dependence primarily arises from the contribution of band electrons44. In the high-temperature area, the distribution of band electrons becomes negligible, and the temperature dependence becomes weak. Moreover, compared to the results of \(\Delta I_{0}\), the overall temperature dependence of the present model is weaker, suggesting a possible competition between the screening contributions from band electrons and the contribution from direct Coulomb potential of neighboring ions. In contrast, the revised EK model only depends on electron and ion densities. Since the ion density remains constant, the electron density increases with temperature. as a result, IPDs calculated by the revised EK model even increases with increasing temperature in such cases.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the influence of neighboring ions should be carefully considered under WDP conditions. Their contribution to IPDs can be categorized into three interrelated parts. First, the Coulomb potential from neighboring ions directly affect the screening potential around the target ion, thereby influence the IPs. Second, the outer orbitals of the target ion expand into continuous energy bands due to the presence of neighboring ions and electrons around. Through inelastic collision processes, electrons can distribute into these bands and also contribute to the screening potential. Third, since the wavefunctions of electrons in these continuous bands remains significantly non-zero at the boundary of the target ion, these electrons can migrate into neighboring ions and become delocalized. As a result, even when their total energy is \({{E}}\text{ < 0}\), electrons excited into these bands can be considered as ionized. The ionization conditions change compared with those in isolated situations. By incorporating both the direct contribution of neighboring ions to the screening potential and the changes in ionization conditions, we have refined our atomic-state-dependent screening model for application in WDP environments. The developed model is applied to calculate IPDs across a wide range of temperatures and densities relevant to recent experiments. By comparing with experiment and results from other models, it can be found the contributions from neighboring ions are important, by including them, good agreement with experiment can be achieved in our model. Furthermore, based on IPD behavior under different temperatures, we suggest a more rigorous time-resolved analysis of signals from the Kα emission, along with the measurements of temperature evolution in further experiment to obtain the actual plasma conditions relate to the measurement of IPDs. The developed model is successfully validated by effectively reproducing IPDs from various experiments under different temperature and density conditions. The inclusion of the direct Coulomb potential from neighboring ions lead to a weaker temperature dependence compared to model neglecting these effects, which suggest a competitive mechanism between the contributions from band electrons and those from the direct Coulomb potential of neighboring ions. Additionally, in wider plasma conditions, how to determine the shells that have expanded into bands, and should be considered in both the screening potential and ionization condition are also discussed in this work. Compared to existing experimental measurements, our model can hold the characteristics of plasma across a wide range of conditions and can be applied to highly excited states, such as hollow ions. With its computational efficiency and broad applicability, this model provides a practical tool for studying IPDs in WDP conditions, and will facilitate future studies of radiation and particle transport properties.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Tayler, R. J. The stars: Their structure and evolution (Cambridge University Press, 1994).

Helled, R., Anderson, J. D., Podolak, M. & Schubert, G. Interior models of uranus and neptune. Astrophys J 726, 15 (2010).

Vinko, S. M. et al. Creation and diagnosis of a solid-density plasma with an x-ray free-electron laser. Nature 482, 59–62 (2012).

Ciricosta, O. et al. Direct measurements of the ionization potential depression in a dense plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 065002 (2012).

Ciricosta, O. et al. Measurements of continuum lowering in solid-density plasmas created from elements and compounds. Nat. Commun. 7, 11713 (2016).

Hoarty, D. J. et al. Observations of the effect of ionization-potential depression in hot dense plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 265003 (2013).

Gomez, M. R. et al. Experimental demonstration of fusion-relevant conditions in magnetized liner inertial fusion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 155003 (2014).

Nagayama, T. et al. Systematic study of L-shell opacity at stellar interior temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 235001 (2019).

Hansen, S. B. et al. Changes in the electronic structure of highly compressed iron revealed by X-ray fluorescence lines and absorption edges. High Energy Density Phys. 24, 39–43 (2017).

Bailey, J. E. et al. A higher-than-predicted measurement of iron opacity at solar interior temperatures. Nature 517, 56–59 (2015).

van den Berg, Q. Y. et al. Clocking femtosecond collisional dynamics via resonant X-ray spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 055002 (2018).

Nguyen, H., Koenig, M., Benredjem, D., Caby, M. & Coulaud, G. E. Atomic structure and polarization line shift in dense and hot plasmas. Phys. Rev. A 33, 1279–1290 (1986).

Chang, T. N., Fang, T. K. & Gao, X. Redshift of the lyman-α emission line of H-like ions in a plasma environment. Phys. Rev. A 91, 063422 (2015).

Janev, R. K., Zhang, S. B. & Wang, J. G. Review of quantum collision dynamics in Debye plasmas. Matter and Radiation at Extremes 1, 237–248 (2016).

Fang, T. K., Wu, C. S., Gao, X. & Chang, T. N. Redshift of the he α emission line of He-like ions under a plasma environment. Phys. Rev. A 96, 052502 (2017).

Fang, T. K., Wu, C. S., Gao, X. & Chang, T. N. Variation of the oscillator strengths for the α emission lines of the one- and two-electrons ions in dense plasma. Phys. Plasmas 25, 102116 (2018).

Chang, T. N., Fang, T. K., Wu, C. S. & Gao, X. Redshift of the isolated atomic emission line in dense plasma. Phys. Scr. 96, 124012 (2021).

Chang, T., Fang, T., Wu, C. & Gao, X. Atomic processes, including photoabsorption, subject to outside charge-neutral plasma. Atoms 10, 16 (2022).

Wu, C., Wu, Y., Yan, J., Chang, T. N. & Gao, X. Transition energies and oscillator strengths for the intrashell and intershell transitions of the C-like ions in a thermodynamic equilibrium plasma environment. Phys. Rev. E 105, 015206 (2022).

Wu, C., Chen, S., Chang, T. N. & Gao, X. Variation of the transition energies and oscillator strengths for the 3C and 3D lines of the Ne-like ions under plasma environment. J. Phys. B-Atom. Mol. Optic. Phys. 52, 185004 (2019).

Ma, Y. et al. KLL dielectronic recombination of hydrogenlike carbon ion in Debye plasmas. J. Quantitive Spectroscopy Radiative Trans. 241, 106731 (2020).

Mazzitelli, G. & Mattioli, M. Ionization balance for optically thin plasmas: Rate coefficients for Cu Zn, Ga, and Ge ions. Atom. Data Nuclear Data Tables 82, 313–356 (2002).

Zeng, J., Li, Y., Gao, C. & Yuan, J. Screening potential and continuum lowering in a dense plasma under solar-interior conditions. Astron. Astrophys. 634, A117 (2020).

Erez-Callejo, G. P. et al. Dielectronic satellite emission from a solid-density mg plasma: Relationship to models of ionization potential depression. Phys. Rev. E 109, 045204 (2024).

Salzman, D. Atomic physics in hot plasmas (OxfoldUniversity Press, 1998).

H.R. Griem, edited by J.E.A.L. Thompson (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 1986), p. 885–910.

Stewart, J. C. & Pyatt, K. D. J. Lowering of ionization potentials in plasmas. Astrophys. J. 144, 1203 (1966).

Ecker, G. & Kröll, W. Lowering of the ionization energy for a plasma in thermodynamic equilibrium. Phys. Fluids 6, 62–69 (1963).

Vinko, S. M., Ciricosta, O. & Wark, J. S. Density functional theory calculations of continuum lowering in strongly coupled plasmas. Nat. Commun. 5, 3533 (2014).

Hu, S. X. Continuum lowering and fermi-surface rising in strongly coupled and degenerate plasmas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 065001 (2017).

Jin, R., Abdullah, M. M., Jurek, Z., Santra, R. & Son, S. Transient ionization potential depression in nonthermal dense plasmas at high x-ray intensity. Phys. Rev. E 103, 023203 (2021).

Plummer, D. et al. Ionization calculations using classical molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 111, 015204 (2025).

Lin, C., Roepke, G., Kraeft, W. & Reinholz, H. Ionization-potential depression and dynamical structure factor in dense plasmas. Phys. Rev. E 96, 0132021 (2017).

Lin, C. Quantum statistical approach for ionization potential depression in multi-component dense plasmas. Phys. Plasmas 26, 122707 (2019).

Zan, X., Lin, C., Hou, Y. & Yuan, J. Local field correction to ionization potential depression of ions in warm or hot dense matter. Phys. Rev. E 104, 025203 (2021).

Davletov, A. E., Arkhipov, Y. V., Mukhametkarimov, Y. S., Yerimbetova, L. T. & Tkachenko, I. M. Generalized chemical model for plasmas with application to the ionization potential depression. New J. Phys. 25, 063019 (2023).

Debye, P. & Huckel, E. The theory of electrolytes i. The lowering of the freezing point and related occurrences. Physikalische Zeitschrift 24, 185–206 (1923).

Son, S., Thiele, R., Jurek, Z., Ziaja, B. & Santra, R. Quantum-mechanical calculation of ionization-potential lowering in dense plasmas. Phys. Rev. X 4, 031004 (2014).

Zeng, J., Li, Y., Hou, Y., Gao, C. & Yuan, J. Ionization potential depression and ionization balance in dense carbon plasma under solar and stellar interior conditions. Astron. Astrophys. 644, A92 (2020).

F.B. Rosmej (2018) Ionization potential depression in an atomic-solid-plasma picture. J. Phys. B-Atom. Mol. Optic. Phys. 51: 09LT01.

Li, X. & Rosmej, F. B. X-ray transition and K-edge energies in dense finite-temperature plasmas: Challenges of a generalized approach with spectroscopic precision. Matter Radiation Extremes 10, 027201 (2025).

Li, X. & Rosmej, F. B. VB-BFC model for calculation of the IPDs in dense finite temperature plasmas. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 345, 109563 (2025).

Zhou, F. et al. Atomic-state-dependent screening model for hot and warm dense plasmas. Commun. Phys. 4, 148 (2021).

Wu, C. et al. Ionization potential depression model for warm/hot and dense plasmas. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, 085202 (2024).

Deschaud, B., Peyrusse, O. & Rosmej, F. B. Generalized atomic processes for interaction of intense femtosecond XUV- and X-ray radiation with solids. Europhys. Lett. 108, 53001 (2014).

Deschaud, B., Peyrusse, O. & Rosmej, F. B. Simulation of XFEL induced fluorescence spectra of hollow ions and studies of dense plasma effects. Phys. Plasmas 27, 063303 (2020).

Thelen, T. Q., Rehn, D. A., Fontes, C. J. & Starrett, C. E. Predicting excitation energies in warm and hot dense matter. Phys. Rev. E 110, 015207 (2024).

Yan, T. et al. Bound state energies and critical bound region in the semiclassical dense hydrogen plasmas. Phys. Plasmas 31, 042110 (2024).

Grant, I. P. Relativistic quantum theory of atoms and molecules (Springer-Verlag, 2007).

Jönsson, P., He, X., Fischer, C. F. & Grant, I. P. The GRASP2K relativistic atomic structure package. Comput. Phys. Commun. 177, 597–622 (2007).

Jun, Y. & Jia-Ming, L. Theoretical simulation of the transmission spectra of Fe and Ge plasmas. Chin. Phys. Lett. 17, 194–196 (2000).

Li, J., Yan, J. & Peng, Y. Spectral resolved x-ray transmission in hot dense plasmas. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 59, 181–184 (2000).

Hoarty, D. J. et al. The first data from the orion laser Measurements of the spectrum of hot, dense aluminium. High Energy Density Phys. 9, 661–671 (2013).

Rosmej, F. B. & Fontes, C. J. Hollow ion atomic structure and X-ray emission in dense hot plasmas. Matter Radiation Extremes 9, 067202 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants No. 12204057 and No. 62165007, the Yunnan Applied Basic Research Projects under Grant No. 202401CF070090, and the Foundation of the National Key Laboratory of Computational Physics. We acknowledge the computational support provided by the Institute for Applied Physics and Computational Mathematics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chensheng Wu: Developed the theoretical framework, implemented computational codes, and write the original manuscript. Jiao Sun: Performed numerical simulations, conducted data analysis, and co-wrote the original manuscript. Chunhua Zeng and Qinghe Song: Participated in the conceptualization and mathematical formulation of the theoretical model. Xiang Gao and Jun Yan: Provided critical theoretical guidance, validated methodological rigor, and oversaw manuscript revisions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, C., Sun, J., Song, Q. et al. Ionization potential depression model with the influence of neighboring ions in warm and dense plasmas. Sci Rep 15, 39678 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23384-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23384-2