Abstract

This article introduces a reduced switch-multiple active bridge (RS-MAB) DC-DC converter as a building block of a three-stage modular solid-state transformer (SST), which decreases the number of switching devices and high-frequency transformers, thereby increasing power density and efficiency. Additionally, the extended triangular current mode (TCM) modulation is employed to enable soft switching across the entire operational range. A theoretical analysis of the general structure of the RS-MAB converter is presented. Numerical analysis, simulation, and laboratory-scale experimental results for a reduced switch-symmetrical quadruple active bridge (RS-SQAB) converter are provided to confirm the feasibility and validity of the proposed converter topology and its modulation method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the primary objectives of the smart grid is to increase the flexibility and controllability of the power system. The solid-state transformer (SST) is a modern technology that enables efficient and controllable power flow in distribution grids. It consists of power electronic converters (PECs) and one or more medium-frequency (MF) transformers that have lower weight and volume than traditional low-frequency transformers (LFTs). In addition to providing LFT functionalities such as voltage matching and galvanic isolation of the primary and secondary sides, the SST also provides other functionalities such as bidirectional power flow control, harmonics reduction, integration of distributed energy resources (DERs), voltage stabilization, frequency regulation, power quality improvement, and fault current reduction1,2,3,4,5,6.

SSTs based on the number of power conversion stages are categorized into four different configurations: single-stage (ac-ac)7,8,9, two-stage (ac-dc-ac) with an LVDC link or HVDC link10,11,12, and three-stage (ac-dc-dc-ac) with an LVDC link and an HVDC link13,14,15. The most preferred configuration for smart grid applications is the three-stage SST. This configuration includes two decoupled DC links at both the MV and the LV sides. It can compensate grid disturbances and allow the direct integration of DERs to the grid either at the LV or the MV side16,17,18,19.

In smart grid applications, the voltage and current of SSTs can reach several kilovolts and kiloamperes. This makes it impractical to use a single-module converter with conventional low nominal value semiconductor switches. Semiconductor switches with high nominal values are very expensive and have high switching losses at high switching frequencies. To address this challenge and enhance the power and voltage of the converter for the DC-DC stage, cascade modular input series-output parallel (ISOP) converters are one of the most widely proposed and developed structures20,21,22. Modular converters enable the use of switches with low nominal voltage values, which have low on-state resistance to enhance overall efficiency. Additionally, using a smaller capacitor and inductor increases the power density of the converter and improves its dynamic response performance. These converters facilitate the converter’s thermal design because each modular converter’s basic module transfers only a portion of the total power. This approach also enhances the system’s overall reliability by reducing thermal and electrical stresses on the converter components. Additionally, the modular structure reduces the time and cost of the converter design process and allows for easy expansion of the converter’s power23,24.

Based on various studies, the dual active bridge (DAB)25,26, multiple active bridge (MAB)27,28, series resonant converters (SRCs)29,30, and multiple active bridge- series resonant converters (MAB-SRC)31,32 are the most suitable topologies for use as basic modules of modular SSTs. The DAB converters present bidirectional power transfer, wide voltage range capability, zero-voltage switching (ZVS) operations, and a simple control method33. MAB converters offer the same functionality as DAB converters, with some, such as asymmetrical quadruple active bridge (AQAB) converters, requiring fewer modules, resulting in decreased costs and improved efficiency34,35. Compared to DAB converters, SRC converters have higher efficiency and lower complexity; however, they cannot control power flow, which is a notable deficit36. The MAB-SRC DC-DC converter integrates the characteristics of both MAB and SRC topologies, resulting in higher overall efficiency compared to MAB and SRC32,35.

This paper presents and analyzes a reduced switch-multiple active bridge (RS-MAB) DC-DC converter as a building block of a three-stage modular solid-state transformer (SST), aiming to reduce both cost and size while maintaining the transferred power.

The phase-shift modulation (PSM) and triangular current modulation (TCM) techniques, which were previously utilized in DAB and QAB converters37,38, can also be implemented in the RS-MAB to modulate the converter. The PSM provides zero-voltage switching (ZVS) turn-on for the switches. However, this feature depends on the relationship between the input and output voltages and the load. Specifically, at light loads, ZVS can be lost. Another drawback of PSM is the high level of circulating reactive power in the high-frequency transformer. In the DAB converter, TCM enables zero-current switching (ZCS) turn-on for all switches and ZCS turn-off for six switches, and it reduces circulating reactive power. However, the root-mean-square (rms) current on the transformer and semiconductors can increase compared with that of the PSM39,40. In this article, the TCM method has been developed and used for the proposed converter modulation, considering that the SST load can vary from light to the rated load.

Construction and operation principle

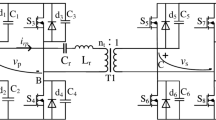

The general topology of the RS-MAB converter is shown in Fig. 1. Like MAB converters, it consists of m bridges on the primary side and n bridges on the secondary side, connected via a one-phase and a k = m + n winding MF transformer. Except that the switches of the bridges between the two windings on each side are integrated and common. Therefore, there are four non-common switches on both sides of the transformer, and 2(m-1) and 2(n-1) common switches on the primary and secondary sides, respectively.

According to the intended application as the solid-state transformer integrated with the distribution grid, the converter’s bridges are series on the medium voltage side to share the high input voltage and are parallel on the low voltage side to share the high output current (ISOP architecture). Other possible architectures (i.e., ISOS, IPOS, and IPOP) are also available by changing the bridges in series or parallel.

To facilitate converter analysis, the Y-model equivalent circuit of the k-winding transformer, illustrated in Fig. 2, is employed. In this model, the LV side parameters are referred to the MV side. The equivalent circuit parameters are derived from the original parameters displayed in Fig. 1 and the transformer turn ratio, as expressed in (1).

According to the application of the SST in a smart distribution grid, the following assumptions should be considered41:

-

All bridges on the MV side have equal voltage values, VM, and all bridges on the LV side have equal voltage values, VL.

-

The power balance conditions are satisfied in both the MV and LV side bridges.

-

The phase-shift angle between the MV and the LV bridges is the same.

-

The turn ratios between the MV windings and the LV windings are the same.

-

The leakage inductance of the MV side windings is equal to that of each other (L1p = L2p=…=Lmp=Lp). Likewise, the leakage inductance of the LV side windings is also the same (L1s = L2s=…=Lns=Ls).

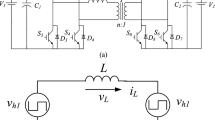

The equivalent circuit of the RS-MAB, considering these assumptions, is shown in Fig. 3. In this case, the RS-MAB is similar to the standard DAB. Therefore, TCM modulation is extended and used to achieve zero-current switching (ZCS) in the RS-MAB converter as an alternative to resonance circuits. The TCM provides three degrees of freedom to control the converter: the MV side duty cycle (Dp), the LV side duty cycle (Ds), and the phase shift(φ). These control parameters are used to determine the amount and direction of the transferred power and to achieve zero current switching.

The switching pattern and key waveforms of the proposed converter with the TCM for transferring power from the MV to the LV side are shown in Fig. 4. The detailed description of each time interval for the positive half-cycle is as follows:

Interval I [0- DpTs]: Before time 0, the current of inductors is zero. At time 0, switches S2, S4, … and S1, S3, …, and Sm of the MV side are turned on at zero current switching, and the voltage VM/m on each MV side winding is applied. Additionally, the body diodes of the switches Q1, Q2, Q3, …, and Qn on the LV side are turned on at zero current switching, and voltage VL is applied on each LV side winding, leading to NVL at the MV side of the transformer. As a result, the difference between two voltages (VM/m- NVL) across the equivalent inductor is positive, and its current increases linearly from zero to its maximum. The maximum value of the current at the end of Interval I can be found using (2). Figure 5 depicts the converter’s configuration with two series bridges on the MV side and two parallel bridges on the LV side during this time interval.

Interval II [DpTs– DsTs]: At time DpTs, switches S1, S3, …, and Sm are turned off. The MV side bridges enter freewheeling mode through S2, S4, …, and the body diode of S’2, S’4, …, applying zero voltage to each MV side winding. The body diodes of switches Q1, Q2, Q3, …, and Qn on the LV side remain on, and voltage VL is applied to each LV side winding. Therefore, the voltage across the inductors will become negative, and the current slope will change from positive to negative. The current changes in this time interval is expressed by (3). The condition defined in (4) must be fulfilled to ensure that the current reaches zero at the moment DsTs and that the ZCS transition is guaranteed. Therefore, the relationship between Dp and Ds is obtained by (5). The configuration of the converter during Interval II is shown in Fig. 6.

Interval III [DsTs–Ts/2]: At time DsTs, the current of inductors is zero, and switches S2, S4, …, and the body diodes of S’2, S’4, …, on the MV side, and the body diode of Q1, Q3, …, Qn on the LV side are turned off at ZCS. For both the MV side and the LV side bridges, zero voltage is applied on each winding. The voltage across the inductors is zero, and their current remains zero until the end of the positive half-cycle. The negative half-cycle process is similar to the positive half-cycle process. The configuration of the converter during Interval III is shown in Fig. 7.

Transformer and semiconductors currents

Based on the current waveforms depicted in Fig. 4, the rms currents on the windings of the MV and LV sides of the transformer are calculated by (6) and (7), respectively.

The voltage and current waveforms of the MV and LV side switches are shown in Fig. 8. As seen, at the MV side, the rms and average current on the switches are unequal and are calculated by (8) and (9) for odd-numbered switches and (10) and (11) for even-numbered switches, respectively.

On the LV side, the rms and average current of common semiconductors are twice that of non-common semiconductors. The rms and average current of non-common semiconductors were calculated by (12) and (13), and for common semiconductors, calculated by (14) and (15), respectively.

To calculate the transferred power, the average value of the MV side current (IM) is calculated by (16), and the transferred power is subsequently calculated by (17).

Configuration, design, and control of the RS-MAB

Different configurations of the RS-MAB can be considered as a building block of the DC-DC stage converter for the ISOP SST structure. In this work, to ensure a fair comparison with the DAB and symmetrical quadruple active bridge.

(SQAB), the RS-MAB unit is considered with two series bridges on the MV side and two parallel bridges on the LV side, and it is named reduced switch symmetrical quadruple active bridge (RS-SQAB).

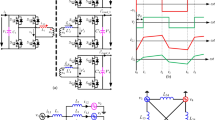

Figure 9 displays one phase of a three-phase modular ISOP SST structure, comprising U number of DAB units (Fig. 9a) and U/2 number of SQAB and RS-SQAB units (Fig. 9b,c). All of these units transfer the same power and have identical input and output voltages and currents.

Design procedure

For the comprehensive analysis and design of the RS-SQAB unit depicted in Fig. 9c, the specifications of the sample grid stated in Table 1 have been used.

If semiconductors with a voltage rating of 1.2 kV, 1.7 kV, and 3.3 kV were selected for the design, and the utilization factor of the switches was considered about 0.65, five RS-SQAB units per phase are required. Therefore, the specifications of each RS-SQAB unit in the three-phase system are: \({V_M}={{{V_{MVDC}}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{V_{MVDC}}} {{N_{unit}}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{N_{unit}}}}={{10.2} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{10.2} 5}} \right. \kern-0pt} 5}=2040\,V,\,\,\,\,\,\,{V_L}={V_{LVDC}}=700\,V\) and \({P_{RS - SQAB}}={{{P_{SST}}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{P_{SST}}} {{N_{unit}}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{N_{unit}}}}={{630\,kw} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{630\,kw} {15}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {15}}=42kw\). Additionally, the selected switching frequency and transformer turn ratio are fs= 20 kHz and N = 1.2, respectively.

The maximum value of the LV side duty cycle is Ds = 0.5. To achieve zero-current switching (ZCS) operation, it is necessary to have a small zero time. Therefore, the nominal duty cycle of Ds = 0.48 is chosen for the LV side27.

Based on Eq. (5), the duty cycle of the MV side is obtained as shown in (18). Using the obtained values and Eq. (17), the equivalent inductance is calculated as shown in (19).

The average and rms current of the semiconductors and the rms current on the MV side and LV side of the transformer are calculated using (6)–(15). The results are summarized in Table 2.

Suitable semiconductor devices for the converter are selected based on the voltage and current stresses encountered during operation. Table 3 summarizes the selected devices along with their key specifications at a junction temperature of 100 °C.

The MF transformer is another crucial element to consider during the design process of the RS-MAB converter. The efficiency and power density of the converter are closely linked to the performance of the MF transformer. The flux density optimization method outlined in reference42 has been implemented to enhance efficiency. Following this method and the design process described in reference32, the appropriate ferrite core and Litz wire were selected. Specifications for the transformers are provided in Table 4. Litz wires have been used to reduce skin and proximity effects43. Also, to ensure equal leakage inductance, a special concentric winding method was employed. As shown in Fig. 10, in this method, the wires of the LV side’s coils in each layer are arranged side by side over the core, while the wires of the MV side’s coils in each layer are placed alongside each other over the LV side’s coils. This design ensures that the length of the coils and their distance from one another and the core are equal, resulting in nearly equal leakage inductance for all coils. The leakage inductances have been calculated based on the core’s geometrical dimensions and the winding parameters44.

As seen, the leakage inductance of the transformers is lower than the required equivalent inductance, determined based on Eq. (19). Therefore, two additional inductors of 31.5 µH should be added to the LV side winding of the transformers.

The specifications of the inductors are shown in Table 5. The core is chosen based on the energy stored in the inductor, the maximum flux density of the core, and the temperature rise in the inductor. After selecting the core, the next step is to design the winding, which involves determining the number of turns and choosing the appropriate wire size. The number of turns (N) in the winding is calculated using the inductance per turn value (AL) provided by the core manufacturers. Additionally, the wire size is determined based on the current density, which considers the desired temperature rise of the windings and the core-window winding area product42.

Also, the value of the DC link capacitor is calculated on the basis that the output voltage ripple does not exceed 0.5%. Therefore, one 150 µF can be used as an LV side DC link capacitor. The specifications of the capacitors are shown in Table 6.

Control system

One of the tasks of the DC-DC converter in the three-stage SST is to control the LVDC link, provide a regulated DC voltage to the LV stage, and control the power flow. The control system shown in Fig. 11 regulates the output voltage and is responsible for the total amount of power transferred from the MV side to the LV side using the DP variable. In this system, the LVDC link voltage is compared with its reference value, and its error is adjusted by a PI controller. Furthermore, to achieve the ZCS condition, the duty cycle of the LV side bridges is calculated using Eq. (5).

Simulation results

To evaluate the converter’s performance and confirm the theoretical analysis presented in this paper, the converter was simulated using PSIM software, based on the parameters outlined in Table 1.

The simulation results for the RS-SQAB converter under steady-state conditions at rated power (42 kW) are presented in Figs. 12 and 13. These results aim to demonstrate the fundamental operation of the converter as analyzed using the TCM discussed in the previous section. Figure 13 demonstrates the voltage and current on the MV side (v1p, v2p, i1p, and i2p) and the LV side (v1s, v2s, i1s, and i2s) of the transformer.

The current and voltage waveforms for the common and non-common switches on the MV side are shown in Fig. 13a,b, respectively. It is noted that the voltage across the common switches is twice that of the non-common switches. Additionally, Fig. 13c,d present the current and voltage waveforms for the common and non-common switches on the LV side. In this case, the current through the common switches is twice that of the non-common switches. Also, these figures illustrate that all switches on the LV side exhibit ZCS during both the turn-on and turn-off. On the MV side, common switches demonstrate ZCS during both the turn-on and turn-off, whereas non-common switches only show ZCS during turn-on.

To assess the dynamic performance of the converter, both with and without the control system, step changes were applied to the load and input voltage. The simulation begins with 70% of the rated load and the nominal input voltage. At t = 0.1s, the load decreases to 40% of the rated value, then increases to 100% at t = 0.2s. Additionally, at t = 0.3s, the input voltage rises by 15%. Figure 14 illustrates the variations in the output voltage of the LV side of the converter without the control system, demonstrating its inability to stabilize the voltage. Figure 15 presents the output voltage variations of the LV side with the control system. In this scenario, the control system utilizes a PI controller to rapidly adjust the duty cycle of the primary (DP) and secondary (DS) sides, ensuring that the LV-side output voltage remains at its nominal value while maintaining the ZCS condition. Figure 16 depicts the variations in the duty cycles of the primary (DP) and secondary (DS) sides.

Losses analysis and comparison

Switching devices are the most critical components that influence the efficiency and cost of modular converters. This section begins by comparing the three topologies in terms of the number of switching devices and total standing voltage (TSV). Subsequently, a loss analysis is conducted to assess and compare the efficiency of each structure.

Eight, sixteen, and twelve power switches are used in each unit of the DAB, SQAB, and RS-SQAB, respectively. Eight switches of the RS-SQAB are non-common, and four switches are common. The standing voltage (SV) of each switch on the LV side and MV side of the DAB and SQAB-based structures can be calculated as follows, respectively45:

Thus, the TSV in the DAB and SQAB-based structures can be calculated as follows, respectively:

In the RS-SQAB-based structure, the SV of each switch on the LV side and each non-common switch on the MV side is the same as that in the DAB and SQAB-based structures, but the SV of common switches on the MV side of the RS-SQAB-based structure is twice that of non-common switches. Thus, the TSV of the RS-SQAB-based structure can be calculated as follows:

The comparison results, summarized in Table 7, demonstrate that the proposed RS-SQAB topology requires fewer switching devices and exhibits a lower TSV, indicating its potential for better performance compared to the DAB and SQAB configurations.

Power switches

The loss of power switches includes switching and conduction losses. As described in the previous section, when the power transfers from the MV side to the LV side, all of the switches turn-on and turn-off under soft-switching conditions, except for non-common switches on the MV side, which turn-off under hard-switching conditions. Consequently, only the turn-off losses for the non-common switches on the MV side are considered, while switching losses for the other switches are neglected. Also, in forward power flow, most of the current flows through the channel of the semiconductors on the MV side, while on the LV side, it predominantly passes through the body diode. Therefore, the losses of power switches can be calculated using Eq. (25).

Where, \(P_{{cond}}^{{MV\,side}},P_{{cond}}^{{LV\,side}}\,and\,P_{{sw}}^{{MV\,side(non - common)}}\) represent the conduction losses of the MV side switches, conduction losses of the LV side switches, and turn-off losses for the non-common switches on the MV side, respectively, and are defined as (26):

In (26), \({R_{DS(on)}}\)is the on-state resistance, \({I_{DS}}\)is the forward current, and tf is the falling time of the switches. Additionally, \({R_{d(on)}}\)is the on-state resistance, \({I_d}\)is the forward current and \({V_{d(on)}}\)is the forward voltage of the body reverse diodes.

Magnetic components

Losses in magnetic components, i.e., inductors and transformers, can be categorized into core and winding losses or copper losses. For non-sinusoidal voltage waveforms, the natural extension of the Steinmetz equation (NSE) can be utilized to calculate core losses per unit volume (in W/m³). The simplified version of the NSE for a square voltage waveform with a duty ratio D is presented in (27)46.

Additionally, the copper losses for each transformer and inductor are calculated using Eq. (28), where RAC denotes the AC resistance of the wires, which is affected by skin and proximity effects at high frequencies. The AC resistance of Litz wires is determined as outlined in reference [47].

Capacitors

The losses of the output DC link capacitors are calculated using Eq. (29), where \({R_{ESR}}\) represents the equivalent series resistance of the capacitor.

The losses associated with various components of the proposed converter were calculated using Eqs. (25)–(29), incorporating the parameter values listed in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. Figure 17 depicts the loss distribution across the converter’s components during forward power flow. Clearly, the conduction losses in the body diodes on the low-voltage (LV) side represent the dominant portion of the total losses.

Next, the efficiency of the proposed converter was calculated and compared with that of the DAB and SQAB converters. The TCM and design procedure described in the previous sections were also applied to the compared converters. The efficiency of converters is illustrated in Fig. 18. The RS-SQAB converter is more efficient than other converters because it has fewer components, particularly switches and high-frequency transformers (HFTs).

Experimental results

To verify the feasibility of the proposed converter topology with the TCM, a 500 W lab-scale prototype was built, and experimental results were obtained. Figure 19 illustrates the experimental prototype of the proposed converter, and its specifications are provided in Table 8. The MOSFET IRFP450s are used on the MV side and LV side bridges.

The maximum duty cycle for the LV side was set at Ds = 0.45. Therefore, the duty cycle for the MV side and the required equivalent inductance were calculated as Dp = 0.3 and Leq = 28.7 µH, respectively. The measured leakage inductance of the transformer from each HV side winding was 7 µH. To address this, two additional inductors of 35 µH were added to the LV side winding of the transformer. As a result, the equivalent inductance measured from the HV side increased to 28.7 µH. The voltage and current on the MV side and LV side of the transformer are depicted in Fig. 20a,b, respectively. As illustrated in the figure, the experimental voltage and current waveforms closely match the theoretical predictions. On the LV side, all switches operate under ZCS conditions during both turn-on and turn-off transitions. On the MV side, common switches also achieve ZCS during both switching events, while non-common switches exhibit ZCS only during turn-on.

Figure 21a,b illustrate the current and voltage waveforms of the common and non-common switches on the LV side. As is evident, the current through the common switches is twice that of the non-common switches, corroborating the theoretical analysis. Moreover, these figures confirm that all switches on the LV side operate under zero-current switching (ZCS) during both turn-on and turn-off transitions. Also, Fig. 22 shows the measured efficiency of the converter across output power levels from 100 W to 500 W. The maximum efficiency of 92.61% occurs at 250 W, while the efficiency at the rated output power is 91.93%.

Conclusion

This article discusses the RS-MAB converter, which can be utilized in the DC-DC stage of solid-state transformers. The RS-MAB converter shares the same features as the MAB converter, such as soft-switching and a reduced number of high-frequency transformers. Additionally, the RS-MAB converter has the unique advantage of reducing the number of switches. This is achieved by integrating and sharing the switches of the bridges between the two windings on each side. Reducing the number of switches can enhance efficiency and increase the power density.

The triangular current modulation (TCM) strategy, previously employed in dual-active bridge (DAB) and quad-active bridge (QAB) converters, was adopted to modulate the proposed converter. This approach enables zero-current switching (ZCS) over a broad range of load and voltage conditions, thereby substantially reducing switching losses. The operating principles and fundamental equations governing the converter under TCM have been systematically derived and presented.

To evaluate the proposed converter and compare it with other suitable DC-DC converters, such as the DAB and SQAB, the RS-MAB, which has two series bridges on the MV side and two parallel bridges on the LV side (i.e., RS-SQAB), was selected, designed, and simulated. The proposed RS-SQAB has fewer devices and TSV than the DAB and SQAB under the same conditions. Additionally, the simulation results verified the theoretical analysis. Furthermore, an efficiency analysis was conducted by calculating element losses. The proposed RS-SQAB demonstrates better efficiency and power density than the DAB and SQAB, because of its lower device count and reduced TSV.

Ultimately, the experimental findings demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed converter topology along with TCM, which ensures ZCS for the converter’s switches.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Shadfar, H., Pashakolaei, M. G. & Akbari Foroud, A. Solid-state transformers: an overview of the concept, topology, and its applications in the smart grid. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 31(9), e12996 (2021).

Huber, J. E. & Kolar, J. W. Solid-State transformers: on the origins and evolution of key concepts. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 10(3), 19–28 (2016).

Adabi, M. E. & Martinez-Velasco, J. A. Solid state transformer technologies and applications: A bibliographical survey. AIMS Energy. 6(2), 291–338 (2018).

Huang, A. Q. Medium-Voltage Solid-State transformer: technology for a smarter and resilient grid. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 10(3), 29–42 (2016).

Saleh, S. A. M. et al. Solid-State Transformers for distribution Systems–Part I: technology and construction. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 55(5), 4524–4535 (2019).

Hannan, M. A. et al. State of the Art of Solid-State transformers: advanced Topologies, implementation Issues, recent progress and improvements. IEEE Access. 8, 19113–19132 (2020).

Basu, K., Shahani, A., Sahoo, K. & Mohan, N. A single stage solid-state transformer for Pwm ac drive with source-based commutation of leakage energy. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 30(3), 1734–1746 (2015).

Qin, H. & Kimball, J. W. Solid-state transformer architecture using ac-ac dual-active-bridge converter. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 60(9), 3720–3730 (2013).

Chen, H., Prasai, A., Moghe, R., Chintakrinda, K. & Divan, D. A 50-kva three-phase solid-state transformer based on the minimal topology: Dyna-c. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 31(12), 8126–8137 (2016).

Glinka, M. & Marquardt, R. A new AC/AC multilevel converter family. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 52(3), 662–669 (2005).

Sabahi, M., Hosseini, S. H., Sharifian, M. B., Goharrizi, A. Y. & Gharehpetian, G. B. Zero-voltage switching bi-directional power electronic transformer. IET Power Electron. 3(5), 818–828 (2010).

Drabek, P., Peroutka, Z., Pittermann, M. & Cedl, M. New configuration of traction converter with medium frequency transformer using matrix converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 58(11), 5041–5048 (2011).

Fan, H. & Li, H. High-Frequency transformer isolated bidirectional DC–DC converter modules with high efficiency over wide load range for 20 kVA Solid-State transformer. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 26(12), 3599–3608 (2011).

Madhusoodhanan, S. et al. Solid-State transformer and MV grid tie applications enabled by 15 kV SiC IGBTs and 10 kV SiC mosfets based multilevel converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 51(4), 3343–3360 (2015).

She, G. R., Husain, X., Huang, A. Q. & I. & Solid-State-Transformer-Interfaced permanent magnet wind turbine distributed generation system with power management functions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 53(4), 3849–3861 (2017).

Han, B., Choi, N. & Lee, J. New bidirectional intelligent semiconductor transformer for smart grid application. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 29(8), 4058–4066 (2014).

Vaca-Urbano, S. F. & Alvarez-Alvarado, M. S. Power quality with solid state transformer integrated smart-grids. 2017 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference - Latin America (ISGT Latin America) 1–6 (2017).

Costa, L. F., De Carne, G., Buticchi, G. & Liserre, M. The smart transformer: A solid-state transformer tailored to provide ancillary services to the distribution grid. IEEE Power Electron. Mag. 4(2), 56–67 (2017).

Ruiz, F. et al. Surveying Solid-State transformer structures and controls: providing highly efficient and controllable power flow in distribution grids. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 14(1), 56–70 (2020).

Shi, J., Gou, W., Yuan, H., Zhao, T. & Huang, A. Q. Research on voltage and power balance control for cascaded modular solid-state transformer. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 26(4), 1154–1166 (2011).

Zumel, P. et al. Modular Dual-Active Bridge converter architecture. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 52(3), 2444–2455 (2016).

Luo, C. & Huang, S. Novel voltage balancing control strategy for Dual-Active-Bridge Input-Series-Output-Parallel DC-DC converters. IEEE Access. 8, 103114–103123 (2020).

Duan, J., Zhang, D., Wang, L., Zhou, Z. & Gu, Y. A Building block method for Input-Series-Connected DC/DC converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 36(3), 3063–3077 (2021).

Kim, S. H., Kim, B. J., Park, J. M. & Won, C. Y. Decentralized control method of ISOP converter for input voltage sharing and output current sharing in current control loop. Energies 13(5), 1114 (2020).

She, X., Yu, X., Wang, F. & Huang, A. Q. Design and demonstration of a 3.6-kv 120-v/10-kva solid-state transformer for smart grid application. IEEE Trans. Power Elect. 29(8), 3982–3996 (2014).

Liu, T. et al. High-Efficiency control strategy for 10-kV/1-MW Solid-State transformer in PV application. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 35(11), 11770–11782 (2020).

Costa, L. F., Buticchi, G., Liserre, M. & Quad-Active-Bridge DC–DC converter as Cross-Link for Medium-Voltage modular inverters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 53(2), 1243–1253 (2017).

Naseem, N. & Cha, H. Quad-Active-Bridge converter with current balancing coupled inductor for SST application. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 36(11), 12528–12539 (2021).

Ortiz, G., Leibl, M. G., Huber, J. E. & Kolar, J. W. Design and experimental testing of a resonant DC–DC converter for Solid-State Transformers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 32(10), 7534–7542 (2017).

Costa, L. F., Buticchi, G. & Liserre, M. A. Family of Series-Resonant DC–DC converter with Fault-Tolerance capability. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 54(1), 1–7 (2018).

Krismer, F., Böhler, J., Kolar, J. W. & Pammer, G. New Series-Resonant Solid-State DC Transformer Providing Three Self-Stabilized Isolated Medium-Voltage Input Ports. 10th International Conference on Power Electronics and ECCE Asia (ICPE 2019 - ECCE Asia) 1–9 (2019).

Khani, S., Hosseini, S. H. & Sabahi, M. An asymmetrical quadruple active Bridge series resonant DC–DC converter for modular solid-state Transformers. IET Power Electron. 17, 1699–1711 (2024).

Cúnico, L. M. & Kirsten, A. L. Improved ZVS range for Three-Phase Dual-Active-Bridge converter with Wye-Extended-Delta transformer. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 69(8), 7984–7993 (2022).

Costa, L. F., Hoffmann, F., Buticchi, G. & Liserre, M. Comparative analysis of multiple active Bridge converters configurations in modular smart transformer. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 66(1), 191–202 (2019).

Pereira, T., Hoffmann, F., Zhu, R. & Liserre, M. A. Comprehensive assessment of multiwinding Transformer-Based DC–DC converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 36(9), 10020–10036 (2021).

Costa, L. F., Buticchi, G. & Liserre, M. Highly efficient and reliable SiC-Based DC–DC converter for smart transformer. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 64(10), 8383–8392 (2017).

Kheraluwala, M. N., Gascoigne, R. W., Divan, D. M. & Baumann, E. D. Performance characterization of a high-power dual active Bridge DC-to-DC converter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 28(6), 1294–1301 (1992).

Ortiz, G., Bortis, D., Kolar, J. W. & Apeldoorn, O. Soft-switching techniques for medium-voltage isolated bidirectional DC/DC converters in solid state transformers. IECON –38th Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics Society 5233–5240 (2012).

Costa, L. F., Buticchi, G. & Liserre, M. Quadruple Active Bridge DC-DC converter as the basic cell of a modular Smart Transformer IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC) 2449–2456 (2016).

Noroozi, N., Emadi, A. & Narimani, M. Performance evaluation of modulation techniques in Single-Phase dual active Bridge converters. IEEE Open. J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2, 410–427 (2021).

Costa, L. F. Modular Power Converters for Smart Transformer Architectures. PhD thesis, Kiel University, (2019).

Hurley, W. G. & Wölfle, W. H. Transformers and Inductors for Power Electronics: Theory, Design and Applications(Wiley, 2013).

Kazimierczuk, M. K. High-Frequency Magnetic Components (Wiley, 2013).

Colonel, W. & McLyman, K. T. Transformer and Inductor Design Handbook (CRC, 2011).

Taheri, A., Rasulkhani, A. & Ren, H. P. An asymmetric switched capacitor multilevel inverter with component reduction. IEEE Access. 7, 127166–127176 (2019).

Valchev, V. C. & Bossche, A. V. Inductors and Transformers for Power Electronics (CRC, 2005).

New England Wire Technologies. Litz Wire Technical Information. (2016). http://www.litzwire.com/nepdfs/Litz_Technical.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: S.KH, S.H.H, and M.S; methodology: S.KH; software, S.KH; validation: S.KH, S.H.H, and M.S; investigation: S.KH; resources: S.KH; data curation: S.KH; writing-original draft preparation: S.KH.; supervision: S.H.H, and M.S.; Visualization: S.KH; writing-review and editing: S.KH; project administration: S.KH, S.H.H, and M.S; Formal analysis: S.KH. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khani, S., Hosseini, S.H. & Sabahi, M. Reduced switch multiple active bridge DC-DC converter for modular solid-state transformers. Sci Rep 15, 39728 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23427-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23427-8