Abstract

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) represent a significant global health burden, and severe exacerbations are associated with worse prognoses. We defined prolonged elevated heart rate (PeHR) as a heart rate exceeding 100 beats per minute for at least 11 h within any continuous 12-hour period. However, the relationship between PeHR and outcomes in patients with AECOPD remains unclear. We identified AECOPD patients in the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV (MIMIC-IV) database and divided them into two groups according to the presence or absence of PeHR. The primary outcome was 28-day mortality. We evaluated the association between PeHR and 28-day mortality using multivariable Cox proportional-hazards models and propensity-score matching. A total of 931 patients with AECOPD were included, 49.6% of whom were male. PeHR occurred in 30.0% of patients. The overall mean age was 72.1 years, and patients with PeHR were younger than those without (71.1 vs. 72.5 years; P < 0.001). Twenty-eight-day mortality was significantly higher in the PeHR group compared with the non-PeHR group (30.3% vs. 15.8%; P < 0.001). In multivariable Cox regression, PeHR was an independent risk factor for 28-day mortality (hazard ratio, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.62–2.87; P < 0.001). After propensity-score matching, the increased mortality in the PeHR group persisted. Prespecified subgroup analyses showed generally consistent effect sizes across all subgroups. PeHR is independently associated with increased 28-day mortality in patients with AECOPD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic respiratory disorder characterized by irreversible, progressive airflow limitation. It causes over 3 million deaths annually, imposing a substantial societal burden1. Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) significantly threaten patient survival; compared with patients without exacerbations, those with AECOPD have a higher risk of respiratory mortality2. Early identification of prognostic factors in AECOPD patients and prompt initiation of effective interventions are crucial for improving survival and quality of life.

Evidence indicates a close association between heart rate and prognosis across various diseases. Studies show that resting heart rate—or heart rate during stable COPD phases—affects patient outcomes. Notably, COPD patients with a resting heart rate below 65 beats per minute (bpm) versus those above 85 bpm exhibit markedly different prognoses3. However, data on heart rate trends during ICU hospitalization for AECOPD patients remain scarce. Moreover, existing studies focus primarily on single time-point measurements—particularly at hospital admission—and their prognostic value. In a multicenter study of 16,485 participants, elevated pre-admission heart rate correlated with increased mortality4.

Current research identifies sustained tachycardia as a risk factor for adverse cardiac events and poor outcomes in critically ill patients5. Nevertheless, the impact of prolonged elevated heart rate (PeHR) on COPD patients has been little explored. A multicenter retrospective study found that PeHR is a risk factor for adverse cardiopulmonary events and poor outcomes in subarachnoid hemorrhage patients6. Similarly, PeHR has been linked to higher mortality in acute pulmonary embolism7, acute pancreatitis8, and sepsis-associated acute kidney injury (S-AKI)9. However, the relationship between sustained heart rate abnormalities and prognosis in AECOPD patients has not yet been specifically investigated.

Method

Data extraction

This study used MIMIC-IV version 3.1. Approval was obtained from the BIDMC Institutional Review Board, and the first author, Xiangtian Liu (certification ID: 65112747), received access to the MIMIC-IV database. MIMIC-IV is a publicly available dataset containing de-identified, comprehensive information on ICU admissions at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Boston, USA) between 2008 and 201910 This study was exempt from human-subjects review because it utilized only anonymous, publicly available third-party data.

Information was extracted via PostgreSQL (version 15.2.1) and Navicat Premium (version 15) using Structured Query Language (SQL). SQL scripts were obtained from GitHub (https://github.com/MIT-LCP/mimic-iv). AECOPD patients were identified by ICD-10 codes J44.0 and J44.1 (Stable 1). Exclusion criteria were ICU length of stay < 24 h, liver cirrhosis, end-stage renal failure, malignancy, or non-first ICU admission. Extracted variables included: (1) Demographics, including age, sex, and race; (2) Primary vital signs within the first day of ICU admission, including mean values of temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and pulse oximetry saturation; (3) Patient comorbidities such as sepsis, and Charlson Comorbidities including myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, rheumatic disease, peptic ulcer disease, diabetes mellitus, and renal disease; (4) Patient treatment information, including hospital length of stay, ICU length of stay, common vasoactive drug use, beta-blockers, hemopurification, and mechanical ventilation. Mechanical ventilation mode during the initial 48 h after ICU admission was recorded. When multiple modes were used simultaneously, patients were assigned to the mode with the highest priority in the following order, with invasive ventilation being highest, followed by non-invasive ventilation, and then other modalities such as high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), supplemental oxygen. (5) Follow-up survival status at 7 days, 14 days, 28 days, and 90 days. (6) Results of initial laboratory measurements following admission, including: Complete blood count: hemoglobin count, red blood cell count, white blood cell (WBC) count, platelet count; Biochemical series: albumin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), glucose, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum sodium, serum potassium, serum chloride; Coagulation function such as prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), international normalized ratio (INR); Cardiac enzymes such as creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), troponin I (TnI), and troponin T (TnT). (7) Scores reflecting disease severity: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II). (8) Patient other diagnoses such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and coronary heart disease. The primary outcome of this study was 28-day mortality. Mortality information for patients discharged from the hospital was obtained from the US Social Security Death Index.

Definition of PeHR

Heart rate measurements after ICU admission were recorded. In our analysis, we defined a peHR episode based on established clinical standards and prior published literature7. PeHR was defined as an average heart rate > 100 bpm sustained for 11 h within any 12-hour window. Due to the possibility of censoring because of the occurrence of death during an eHR episode, we considered patients who had an ongoing high heart rate before death were also classified in the PeHR group (extended definition)5.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using t-tests or ANOVA and are presented as mean ± SD or median (IQR). Categorical variables are presented as n (%) and analyzed with the chi-square test, continuity-corrected chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test. Kaplan–Meier curves assessed 28-day mortality across PeHR strata, with differences tested by log-rank. Cox proportional-hazards models evaluated the association between PeHR and 28-day mortality.

Analyses were performed in R 4.4.1. Variables with > 10% missing data were excluded; those with < 10% were imputed using the missForest package ( SFig 1 ). Propensity-score matching (1:1 nearest-neighbor without replacement) adjusted for confounders. Scores were estimated via multivariable logistic regression. Balance was assessed by standardized mean differences (STable1). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline information and clinical outcomes

Figure 1 shows the flowchart outlining the patient enrollment process. A total of 2,840 AECOPD patients, who met the diagnostic criteria for AECOPD and required ventilator support, were initially enrolled. After applying the exclusion criteria, 931 AECOPD patients were included in the study. Of these, 297 patients were in the PeHR group, and 634 patients were in the non-PeHR group.

Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics. The cohort comprised 931 eligible AECOPD patients, with 31.9% in the PeHR group. Males accounted for 49.6% of the cohort, and White patients represented the largest racial group (66.2%). The PeHR group was younger than the non-PeHR group (71.1 years vs. 72.5 years, p = 0.041). The PeHR group showed significantly higher rates of in-hospital mortality and mortality at 7-Day mortality, 14-Day mortality, 21-Day mortality, 28-day mortality, and 90-Day mortality compared to the non-PeHR group, along with longer hospital and ICU lengths of stay. Regarding the severity assessment scores, patients in the PeHR group had higher Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores (5.00 vs. 4.00, p = 0.001) and Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS-II) scores (39.0 vs. 35.0, p < 0.001). The prevalence of comorbid sepsis was higher in the PeHR group (75.8% vs. 60.9%, p < 0.001), and a higher proportion of patients in the PeHR group received beta-blocker therapy (27.9% vs. 10.1%, p < 0.001).

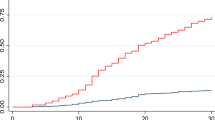

To improve the identification of peHR episodes, we delineated six distinct patterns observed over a 100-hour monitoring period; illustrative examples of these patterns, shown in heart rate tracings from patients with and without peHR episodes, are presented in Fig. 2.

Example heart rate curves. The plots show the hourly heart rate over time (x-axis). The upper panel shows patients without peHR, and the lower panel shows patients with peHR. The red line shows the heart rate threshold of 100/min. A peHR was defined as 11 of 12 consecutive heart rates above 100/min or above the red line in these examples.

Outcome analysis

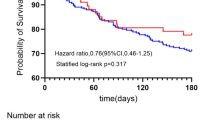

We focused on 28-day mortality. Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves were used to illustrate the survival probabilities of the two patient groups (with and without PeHR). The survival differences were compared using the log-rank test. The results showed a significantly higher mortality rate in the PeHR group compared to the non-PeHR group. The overall 28-day mortality rate for the entire cohort was 25%. Figure 3 presents the Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves depicting the unadjusted survival rates for patients with and without PeHR episodes. A significantly increased unadjusted mortality rate was observed in the PeHR group (30.3% vs. 15.8%, P < 0.001).

The PeHR is an independent risk factor for 28-day mortality

To further explore the relationship between PeHR and patient outcomes, we performed univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses. First, univariable Cox regression analysis was conducted to identify potential risk factors. The results showed a significant association between unadjusted PeHR and 28-day mortality (HR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.59–2.82; P < 0.001) (Table 2). Confounding factors with P < 0.05 in the univariable analysis, combined with our prior clinical experience, were incorporated into the multivariable regression model. In the multivariable Cox regression analysis, we adjusted for potential confounders, including PeHR, age, SOFA score, SAPS-II score, myocardial infarction, respiratory rate, temperature, sepsis, and hemopurification, to assess the association between PeHR and 28-day mortality. After adjustment, PeHR remained significantly associated with 28-day mortality (adjusted HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.30–2.39; P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Outcome after propensity score matching

To address baseline differences, we performed propensity score matching (PSM) using a 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching algorithm. All included covariates demonstrated a standardized mean difference (SMD) below 10% (STable 1), and this balance was visually confirmed. The propensity score regression model was constructed incorporating age, SAPS-II, and SOFA score, selected based on our prior clinical experience. After PSM, 297 matched pairs of PeHR and non-PeHR patients were obtained. Analysis of the post-matching baseline characteristics table (STable 2) indicated that significant differences persisted, with the PeHR group exhibiting higher rates of in-hospital mortality, mortality at 7, 14, 21, 28, and 90 days, along with longer hospital and ICU lengths of stay. Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis (Fig. 4) revealed that even after adjustment via PSM, the PeHR group maintained a significantly higher 28-day mortality rate (30.3% vs. 16.8%, P < 0.001).

Subgroup analyses

To assess the association between PeHR and 28-day all-cause mortality in patients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (AECOPD), we performed subgroup analyses (Fig. 5). The results showed consistent findings across subgroups, demonstrating higher all-cause mortality in the PeHR group within several predefined AECOPD patient subgroups. No significant interaction effects were observed. These findings suggest that the predictive relationship between PeHR and patient mortality remains robust.

Exploration of various thresholds

In a post hoc analysis, we examined the effects of different heart rate thresholds and cumulative durations. Using Cox proportional hazards regression, we estimated hazard ratios (HRs) for 28-day mortality in AECOPD patients across multiple threshold–duration combinations (Fig. 6). Overall, higher heart rate thresholds and longer durations were associated with an increased risk of 28-day mortality.

Discussion

Our study investigated the association between PeHR and outcomes in ICU-admitted AECOPD patients. We extracted data from the MIMIC database on 931 patients diagnosed with AECOPD and analyzed their comprehensive clinical information. Our findings indicate a significant association between PeHR episodes and 28-day mortality among AECOPD patients. To address potential confounding factors, we performed propensity score matching based on a regression tree model using age, SAPS-II score, and SOFA score. This association persisted after adjustment. Furthermore, subgroup analyses revealed consistent trends across all predefined subgroups. These results suggest that PeHR may serve as an important prognostic indicator in AECOPD patients. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of monitoring both the duration and degree of elevated heart rate as valuable prognostic markers in AECOPD patients.

Heart rate, as a vital sign, reflects disease severity to some extent. The increase in heart rate may be driven by factors such as tumor burden, systemic chronic inflammation, anemia, fluid imbalance, or adverse effects of medications (e.g., chemotherapy, targeted therapies). However, transient increases in heart rate are not necessarily indicative of a poor prognosis. While previous studies linked elevated heart rate to mortality in sepsis patients, a recent multicenter cohort study found that septic patients with lactate levels ≥ 5.3 mmol/L in the tachycardia group had lower in-hospital mortality compared to those with normal heart rates11. This suggests that, within a physiological range, tachycardia may act as a compensatory response that improves tissue perfusion and can be beneficial to the patient, rather than merely serving as a marker of poor prognosis. Compared with conventional metrics such as admission heart rate or the mean heart rate at admission, prolonged elevated heart rate (peHR) captures both the magnitude and duration of heart rate exposure over a defined time window and has been associated with disease severity in multiple studies. PeHR appears, in many critical illnesses, to offer greater prognostic discrimination than commonly used summary measures such as mean or peak heart rate. In our study we recorded the mean admission heart rate; the group means were very similar (20.0 vs. 21.7). However, Cox regression revealed markedly different associations with 28-day mortality for mean heart rate versus PeHR (hazard ratios 1.09 vs. 2.12), suggesting that sustained heart rate elevation may better predict adverse outcome than the mean heart rate. In a study of critically ill patients12, patients were stratified by heart-rate thresholds and by the duration that heart rate exceeded 100 bpm; the group with prolonged tachycardia had a markedly higher mortality than the group defined by high heart rate alone (7.9% vs. 57.1%).Similarly, in an acute pancreatitis cohort peHR showed a substantially greater association with 90-day mortality than mean heart rate (HR 2.48 vs. 1.01)8.Additionally, numerous studies have reported similar associations between elevated heart rate and worse outcomes in patients with acute ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke13.

The relationship between heart rate and prognosis in AECOPD patients has been well recognized. Several factors contribute to elevated heart rate in AECOPD. Firstly, tachycardia is closely linked to hypoxia induced by pneumonia, with the degree of elevation potentially reflecting the severity of hypoxia. Beyond hypoxia, long-term oxygen deprivation in COPD patients can lead to cardiac complications, such as right ventricular overload or heart failure, which may manifest as increased heart rate. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation and other atrial arrhythmias is also increased during COPD admissions. A Vietnamese hospital study reported rates of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and atrial arrhythmias at 15.2% and 72.6%, respectively14. Tachycardia resulting from these complications further underscores the association between elevated heart rate and poor outcomes. Studies specifically focusing on heart rate and prognosis in COPD patients support this view. In a cohort of 397 patients with AECOPD, admission heart rate (AHR), defined as the first heart rate recorded at initial admission, showed a non-linear association with in-hospital mortality. When AHR exceeded 100 beats per minute (bpm), each 1-bpm increase was associated with a 9.4% higher risk of in-hospital mortality15. Furthermore, while substantial research has explored the link between heart rate variability (HRV) and AECOPD risk, indicating its prognostic relevance16, the overall body of evidence consistently suggests a significant relationship between elevated heart rate and patient outcomes.

While elevated heart rate is often linked to adverse outcomes, the impact of heart rate control on AECOPD prognosis remains debated. The multicenter BASEL II-ICU trial (n = 314) investigated β-blockers for heart rate control in ICU patients with acute respiratory failure and suggested a potential association with reduced mortality17. Conversely, the BLOCK COPD trial (n = 532), found that metoprolol treatment in COPD patients (without primary cardiovascular indications) might increase the risk of acute exacerbations18. Despite achieving significant heart rate reduction, the trial reported an increased incidence of severe exacerbations, indicating that metoprolol initiated solely for tachycardia reduction may not be safe in this population. Patients who experienced PeHR had a higher utilization of β-blockers. Nevertheless, subgroup analysis failed to show substantial differences in mortality based on β-blocker administration. This complex relationship is influenced by numerous confounders, including the target heart rate for control, timing of initiation, and specific patient subgroups. While many questions and apparent contradictions require further investigation, it is currently evident that excessively high heart rates (> 100 bpm) are detrimental to patients.

Finally, although our study identified an association between PeHR and prognosis, several limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, the retrospective design limits the ability to exclude all potential confounding factors and preclude definitive causal inferences. These aspects may affect the precision of our conclusions and warrant validation in prospective studies. Secondly, reliance solely on data from the single-center MIMIC database may limit the generalizability of our findings to diverse populations or healthcare settings and introduces potential selection bias. Future studies should aim to validate these results in multi-center and multi-regional cohorts to enhance their applicability. Lastly, a short-term elevation in heart rate near the end of life is a recognized physiological phenomenon, and its potential influence on the PeHR definition, although minimized by our duration criteria (11 h in 12), remains a conceptual challenge.

Conclusion

Our study findings reveal a significant correlation between PeHR and higher 28-day mortality in patients with AECOPD.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: the MIMIC-IV database (version 3.1; https://mimic.mit.edu/).

References

Cornelius, T. Clinical guideline highlights for the hospitalist: GOLD COPD update 2024. J. Hosp. Med. 19 (9), 818–820 (2024).

Lenoir, A., Whittaker, H., Gayle, A., Jarvis, D. & Quint, J. K. Mortality in non-exacerbating COPD: a longitudinal analysis of UK primary care data. Thorax 78 (9), 904–911 (2023).

Jensen, M. T. et al. Resting heart rate is a predictor of mortality in COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 42 (2), 341–349 (2013).

Byrd, J. B. et al. Blood pressure, heart rate, and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the SUMMIT trial. Eur. Heart J. 39 (33), 3128–3134 (2018).

Sandfort, V., Johnson, A. E. W., Kunz, L. M., Vargas, J. D. & Rosing, D. R. Prolonged elevated heart rate and 90-Day survival in acutely ill patients: data from the MIMIC-III database. J. Intensive Care Med. 34 (8), 622–629 (2019).

Schmidt, J. M. et al. Prolonged elevated heart rate is a risk factor for adverse cardiac events and poor outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit. Care. 20 (3), 390–398 (2014).

Wang, G. et al. Prolonged elevated heart rate is association with adverse outcome in severe pulmonary embolism: A retrospective study. Int. J. Cardiol. 417, 132581 (2024).

Xie, S., Deng, F., Zhang, N., Wen, Z. & Ge, C. Prolonged elevated heart rate and 90-Day mortality in acute pancreatitis. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 9740 (2024).

Deng, F., Zhu, C., Cao, Y. & Zhao, S. Impact of prolonged elevated heart rate on sepsis-associated acute kidney injury patients: a causal inference and prediction study. Kidney research and clinical practice 2025.

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data. 10 (1), 1 (2023).

Na, S. J. et al. The association between tachycardia and mortality in septic shock patients according to serum lactate level: A nationwide multicenter cohort study. J. Korean Med. Sci. 38 (40), e313 (2023).

Hayashi, M. et al. Prolonged tachycardia with higher heart rate is associated with higher ICU and In-hospital mortality. Acta Med. Okayama. 73 (2), 147–153 (2019).

Nakicevic, A., Alajbegovic, S. & Alajbegovic, L. Tachycardia as a negative prognostic factor for stroke outcome. Materia socio-medica. 29 (1), 40–44 (2017).

Nguyen, H. L., Nguyen, T. D. & Phan, P. T. Prevalence and associated factors of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and atrial arrhythmias during hospitalizations for exacerbation of COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 19, 1989–2000 (2024).

Zhou, R. & Pan, D. Association between admission heart rate and in-hospital mortality in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and respiratory failure: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pulm. Med. 24 (1), 111 (2024).

MacDonald, D. M. et al. Heart rate variability on 10-Second electrocardiogram and risk of acute exacerbation of COPD: A secondary analysis of the BLOCK COPD trial. Chronic Obstr. Pulmonary Dis. (Miami Fla). 9 (2), 226–236 (2022).

Noveanu, M. et al. Effect of oral β-blocker on short and long-term mortality in patients with acute respiratory failure: results from the BASEL-II-ICU study. Crit. Care. (London, England). 14 (6), R198 (2010).

Dransfield, M. T. et al. Metoprolol for the prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD. N. Engl. J. Med. 381 (24), 2304–2314 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the assistance provided by the Yantai Key Laboratory of Sepsis and Organ Injury.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province under Grant [ number ZR2021MH207, ZR2025MS144, ZR2021MH289].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XL. L designed research; XT. L and QX.Y wrote the main manuscript text and all figures; XH.T, RT.Z and YX. Z revised the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Zou, R., Zhai, Y. et al. Prolonged elevated heart rate and 28-day mortality in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients insights from the MIMIC-IV database. Sci Rep 15, 39782 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23555-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23555-1