Abstract

Often characterized as thoughts unrelated to the ongoing task, mind-wandering occupies up to 50% of our waking hours and impacts neural and behavioural functioning. Until now, research has focused on the impact of mind-wandering on immediate task performance, but its relationship to neural states that support learning-related gains over time remains unclear. Previous research examining brain signal complexity during task performance showed that periods of mind-wandering were associated with higher signal complexity compared with on-task states, reflecting increased neural flexibility. The primary aim of this study was to investigate whether higher signal complexity associated with mind-wandering may represent a flexible neural state conducive to longer-term learning. Twenty-six adults underwent electroencephalography recording while performing a visual texture discrimination task before and after a training period, with their attention state probed throughout the task. Task performance improved and N1 and P3 event-related potential (ERP) amplitudes were modulated significantly following training (p’s < 0.01). Moreover, greater pre- and post-training mind-wandering, better post-training performance, and larger ERP amplitudes were all associated with higher signal complexity (p’s < 0.05). Overall, these results suggest that greater engagement in mind-wandering is linked to a high-flexibility brain state that supports longer-term learning in low-level perceptual tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Humans engage in mind-wandering, or thoughts unrelated to an ongoing task1, up to 50% of our waking time during daily activities such as working, watching television, and exercising2,3,4,5. Episodes of mind-wandering are associated with altered brain function6,7,8, task performance9,10,11, and mood12,13,14,15. Generally, mind-wandering impairs cognitive performance10, but is beneficial for tasks that require flexible responding9,16 and has been linked to higher neural flexibility17. These findings suggest that flexibility associated with mind-wandering may be relevant when studying learning and plasticity.

In terms of behavioural effects, mind-wandering is associated with impaired performance on low-demand cognitive tasks. One of the most widely used tasks to elicit these behavioural effects is the Sustained Attention to Response Task (SART)18, which involves responding to frequent non-target stimuli (go) and withholding responses to infrequent target stimuli (no-go). Studies consistently demonstrate that mind-wandering during the SART leads to decreased accuracy and increased response times19,20,21,22,23. This decreased accuracy is apparent in both greater errors (i.e., failure to withhold a response to target stimuli) and omissions (i.e., failure to respond to non-target stimuli), suggesting both sustained attention and response inhibition are disrupted during mind wandering10,24,25.

In terms of neural effects, a large body of empirical work has examined the influence of mind-wandering on event-related potentials (ERPs) in response to external stimuli. In line with the perceptual decoupling hypothesis suggesting that attention is disengaged from the environment during mind-wandering so that resources can be directed to self-generated thoughts26,27,28, empirical evidence indicates that mind-wandering suppresses task-relevant evoked neural activity29,30. Specifically, the P1 and N1, which reflect initial sensory level visual processing31, and the P3, which reflects recruitment of cognitive processes such as attention, memory, and decision-making32,33, are significantly reduced when mind-wandering compared to focusing on the task during sustained attention tasks29,34,35,36,37. Further, frequency of mind-wandering during a task has also been linked to attenuation of task-relevant ERP amplitudes38. The convergence of behavioural and ERP findings clearly show that mind-wandering dampens neural processes that support successful task performance.

Although ERPs provide valuable insights into how neural processes unfold over time, they do not take into consideration that the brain is a highly nonlinear system that is in a constant state of adaptation39. This feature is characteristic of a complex adaptive system, with activity that is neither completely predictable nor completely random. Moment-to-moment fluctuations occur across different spatial and temporal scales to enable transitions between neural network configurations, reflecting the range of possible responses that can be generated40,41. Multiscale entropy (MSE) is a measure of EEG signal complexity that characterizes the entropy (i.e., predictability) of the time series over increasing temporal scales, ranging from fine (e.g., 1 ms windows) to coarse (e.g., minute-long windows)42,43. MSE can mathematically separate completely random and completely predictable signals from those that contain both random and predictable properties42,43. Importantly, research has shown that measuring complexity across timescales captures relevant space–time structures within a neural signal, with increased complexity at fine timescales reflecting greater local flexibility, and increased complexity at coarse time scales reflecting greater flexibility within long-range interactions39,44,45,46.

The functionally optimal level of brain signal complexity appears to vary based on task requirements. Generally, lower complexity represents a reduced need for flexibility in response to more predictable environmental demands, which may be less suitable in the context of adaptive responding to dynamic stimuli. Alternatively, higher complexity supports a greater degree of network flexibility by allowing for quicker transitions between potential network configurations and, in some cases, improved performance. Several studies have shown that higher signal complexity is associated with less variable response times and greater performance accuracy40,45,47. In a recent study, Cnudde and colleagues17 examined signal complexity during periods of mind-wandering while participants completed Navon’s task, which involves visual processing of both local and global stimulus features. Compared with focused states, periods of mind-wandering led to decreased performance accuracy, but were associated with increased signal complexity at coarse timescales17. Although disengagement from a task reduces evoked neural responses through perceptual decoupling, these findings suggest that mind-wandering states may promote increased neural flexibility.

While past research has almost exclusively focused on the neural dynamics of mind-wandering in the context of immediate task performance, the longer-term consequences of mind-wandering on learning-related change remains unclear. Although Cnudde and colleagues17 observed that periods of mind-wandering were associated with transiently impaired task performance, the relatively unconstrained nature of mind-wandering may facilitate the formation of new network configurations to support new behaviours, a process that could be adaptive in the context of learning a new skill. Visual perceptual learning tasks represent a well-delineated method for inducing measurable performance change. These tasks involve extended practice of discrimination or detection of simple visual features such as orientation, colour, and contrast48,49,50,51,52. For example, in a seminal study using a texture discrimination task, Karni and Sagi49 demonstrated that the speed of perception for three diagonal bars among an array of horizontal bars significantly improved with training. When participants complete thousands of practice trials over the course of days or weeks, they show long-lasting improvements in task proficiency and brain changes in regions that support sensory and visual processing49,53,54,55,56,57,58. Functional plasticity associated with perceptual task training can be indexed by changes in P1, N1, and P3 components. For example, both decreases and increases in parieto-occipital P1 amplitudes have been reported after training on orientation59,60,61 and texture62 discrimination tasks. Following training, consistent decreases in parietal and occipital N1 amplitudes60,63,64,65,66 and increases in parietal and occipital P3 amplitudes63,65,66 are seen across a variety of perceptual learning tasks. To our no knowledge, no studies thus far have assessed how a flexible neural state relates to mind-wandering frequency and its potential to support longer-term perceptual learning.

In the current study, we examined whether increased signal complexity associated with mind-wandering represents a flexible neural state conducive to learning over time during a low-level visual perceptual learning task. Across two sessions, neurotypical adults underwent EEG acquisition while completing a texture discrimination task (TDT)49 with two training sessions in between. Participants were periodically queried on their attention state to examine the relationship between mind-wandering, brain signal complexity, relevant ERP components, and task proficiency. In line with previously reported training effects on the TDT, we hypothesized improvements in performance, increased P1 and P3 amplitudes, and decreased N1 amplitudes following training54,62,63. As an extension, we hypothesized that greater mind-wandering would be associated with higher brain signal complexity, in line with Cnudde and colleagues17. Considering both lines of evidence related to ERPs and signal complexity within the mind-wandering literature, two competing hypotheses emerge. Based on existing findings of decreased ERP amplitudes during mind-wandering through perceptual decoupling, we hypothesized that greater engagement in mind-wandering would be associated with a neural state related to lower performance gains following training. However, given that higher signal complexity supports the exploration of multiple response options to generate potentially new behaviours40,41, and performance improvements in perceptual learning tasks are likely supported by functional brain changes54, we hypothesized that greater mind-wandering would be associated with higher signal complexity, a neural state that may be linked to improved performance following training.

Method

Participants

Study participants included 26 neurotypical adults (M = 25.04 years old, SD = 3.74) with a mean of 17.54 years of education (SD = 2.49) recruited from the Calgary community (see Table 1 for demographic information). Eligibility criteria included normal or corrected-to-normal vision and sufficient proficiency in the English language to complete study requirements. Exclusion criteria included current or recent (within the past 2 years) psychiatric, neurological, or cognitive impairment and/or use of psychotropic medication. All participants provided written informed consent and were compensated in the form of an electronic gift card with a maximum value of $120. This study was approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Faculties Research Ethics Board (REB20-1335) and was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

The sample size was selected according to Cohen’s67 recommendation that a minimum of 20 participants per condition is sufficient for detecting small to large effects in electrophysiological research. A priori power estimates using G*Power68 indicated that our sample size was sufficient to detect moderate to large effects with 80% power in our behavioural analyses. Finally, while there is not a standardized approach to estimate power for non-parametric multivariate analyses, previous research using our chosen analysis method suggests that significant effects can be found with less than 30 participants per condition45,69,70.

Procedure

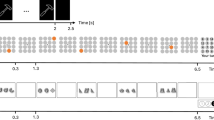

See Fig. 1a for a schematic diagram of the study procedure. Participants completed the TDT during the pre- and post-training EEG sessions, which occurred seven days apart. Two separate behavioural training sessions (on different days) occurred between the EEG sessions, during which participants completed the TDT with auditory feedback to facilitate training.

Schematic diagram of the study procedure and example stimulus frames. (a) Participants completed 400 trials of the texture discrimination task (TDT) during an EEG session before and after completing 1500 TDT trials during training sessions on two separate days. Auditory feedback was provided on correct responses during the training sessions only. (b) The peripheral target angle (PTA) was continuously adjusted (± 0.5 degrees) to maintain performance at 80% accuracy throughout the experiment. Translucent red rectangles highlight the peripheral target within each stimulus frame (for illustrative purposes only).

Texture discrimination task

Set-up

The task program was developed with Unity software (Unity Technologies, 2023) and executed on an ASUS TUF Gaming A15 laptop with Windows 11. Participants were seated 60 cm from a Ben Q LED monitor (60 Hz refresh rate, 1080p resolution).

Stimuli

During each trial, a blank screen was presented for 100 ms, a fixation cross (0.76° × 0.76° of visual angle) for 500 to 1000 ms (random uniform distribution), and another blank screen for 17 ms. The target stimulus was then presented for 100 ms, consisting of a peripheral target composed of three diagonal bars arranged in either a vertical or horizontal orientation (random uniform distribution) among a 19 × 19 array of horizontal bars (23.54° × 23.54° of visual angle). The location of the peripheral stimulus varied randomly within the horizontal array to minimize expectancy. A letter, either an L or a T, was placed in the centre of the array for central fixation. A blank screen was then presented for 400 ms followed by a visual mask for 33 ms, consisting of a 19 × 19 array of randomly oriented < s (23.54° × 23.54° of visual angle), and another blank screen for 500 ms. To minimize habituation, the physical position of the centre of each element within the stimulus array was randomly jittered, in vertical and horizontal position, drawn from a uniform distribution within ± 1/10th of the distance in horizontal array spacing. After each trial, participants indicated whether the peripheral stimulus was oriented horizontally or vertically using the left or right arrow key on a keyboard placed in front of them. Task difficulty was continuously adjusted based on response accuracy by altering the distinctness of the peripheral target from the horizontal lines in terms of the angle of the target lines. All participants began the task with the peripheral target lines oriented at 35-degree angles from horizontal midline. Performance was maintained at 80% accuracy throughout the experiment in an effort to minimize differences in task proficiency and visual function across participants. Performance was evaluated in consecutive blocks of five trials, with the peripheral target angle (PTA) increased or decreased by 0.5 degrees if performance was below or above 80%, respectively (see Fig. 1b). If the PTA was incremented in the same direction for multiple consecutive blocks, then it would increase or decrease at a faster rate (e.g., 0.5 degrees * the number of consecutive blocks of increase). Blocks without an increment or decrement would interrupt this PTA change acceleration.

EEG sessions

Participants completed 400 trials of the TDT during the pre-and post-training EEG sessions (described above).

Training sessions

Participants completed 1500 trials of the TDT during two training sessions that occurred on separate days between the pre- and post-training EEG sessions. Auditory feedback was provided through headphones with a tone indicating a correct response. The PTA at the end of the previous session was used as the starting PTA for the training sessions to ensure all participants maximally trained at their individual 80% performance threshold.

The mean number of days between the pre-training and first training sessions was 2.08 (range: 1–5), between the first and second training sessions was 2.31 (range: 1–5), and between the second training and post-training sessions was 2.73 (range: 1–5).

Experience sampling

The probe-caught method was used to assess attention state, which is the most common experience sampling technique used in the mind-wandering literature1,71. This method involves prompting participants at random intervals during a task to explicitly ask whether they had been engaging in task-related thought (i.e., focused) or task-unrelated thought (i.e., mind-wandering). Every 30 to 90 s (mean = 60 s), participants were queried on whether they had been focused or mind-wandering and provided their response using the left or right arrow key, respectively. Variable inter-probe intervals were used to minimize expectancy. Before beginning the task, participants were assured that probes were not included as attentional catch items and asked to respond truthfully. The amount of mind-wandering was quantified as the proportion of probes endorsed as mind-wandering during the pre- and post-training EEG sessions separately.

EEG data collection and preprocessing

Continuous EEG data were acquired in a dimly lit, electrically shielded room using a Brain Vision actiCHamp system (Brain Products GmbH; Gilching, Germany) with a 500 Hz sampling rate and no online filtering. An array of 64 active electrodes (universal 10–10 system) referenced online to Cz were used, and impedances of ≤ 20 kΩ were established prior to recording.

Pre- and post-training EEG datasets were preprocessed separately offline in MATLAB 2019a (MathWorks, Inc.) using the EEGLAB v14.1.172 toolbox with the ERPLAB v9.1073 plug-in. Data were bandpass filtered (IIR Butterworth, half-amplitude cut-off: 0.5–55 Hz, second order, slope: 12 dB/octave) and channels with significant noise were manually identified and spherically interpolated. Data were then re-referenced to the common average and noisy segments were manually removed before submission to independent components analysis (excluding interpolated and reference electrodes, Infomax decomposition algorithm). Individual components reflecting eye blinks, saccades, muscle activity, and electrode noise were manually identified and removed (mean of 6.15 and 6.38 components removed in pre- and post-training conditions, respectively). Noisy channels were re-interpolated and data were separated into 1.2 s epochs (-200 to 1000 ms) around target stimulus onset and baseline corrected (-200 to 0 ms). Trials with significant noise (-100 to 100 µV simple voltage threshold) were detected and removed using the ERPLAB artifact detection algorithm. On average, 2.03% (SD = 2.89%) of pre-training EEG trials and 4.04% (SD = 6.71%) of post-training EEG trials were removed during artifact rejection. The mean number of trials included in subsequent ERP and MSE analyses were 386.19 (range: 281–416) and 377.42 (range: 279–401) in the pre- and post-training conditions, respectively.

Behavioural analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out in IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29). To confirm that accuracy in the TDT was maintained at 80% during both the pre- and post-training EEG sessions, a paired t-test was conducted comparing the proportion of correct responses between pre- and post-training EEG sessions. To test the hypothesized change in performance following task training, a paired t-test was conducted to compare the modal PTA during the pre- and post-training EEG sessions. Finally, two paired t-tests were conducted to compare response times and the proportion of thought sampling probes endorsed as mind-wandering during the pre- and post-training EEG sessions. The assumption of normality was violated for the PTA data (Shapiro–Wilk p < 0.05), as one participant had an outlier score in the post-training EEG condition (> 3 SDs from the mean). An examination of their dataset indicated that outlier PTA values occurred only during the final 25% of trials (likely due to fatigue). Behavioural and EEG data from these trials were therefore discarded.

EEG analyses

Event-related potential (ERP) components

ERPs were computed for each participant in pre- and post-training conditions using ERPLAB v9.1073. Relevant electrodes with prominent ERP component activity were chosen for analyses based on visual inspection of peak latency and polarity, recommendations outlined by Luck74, and parameters used by Ahmadi and colleagues63 to maximize replicability and comparability. Our analyses focused on the P1 and N1 as indices for sensory level visual processing and the P3 for cognitive processing. The P1 component was not reliably observed within the expected time window (80–130 ms) and electrode sites (parietal and occipital) and was therefore excluded from analyses. P1 component characteristics are influenced by varying stimulus properties, including the location within the visual field, with maximal amplitudes elicited by foveal-presented stimuli75. In our study, target stimuli were pseudo-randomly presented peripherally within all four quadrants of the visual field, likely contributing to an undetectable P1 component. The N1 component, which is most prominent at lateral parietal and lateral occipital electrode sites74, was characterized as the average amplitude within 100 and 150 ms following stimulus onset measured at electrodes P8, P6, PO8, PO7, P5, and P7. The P3 component, which is most prominent at midline parietal electrode sites74, was characterized as the average amplitude measured from 200 and 400 ms following stimulus onset at electrodes P4, P2, Pz, P1, and P3. To test the hypothesized change in ERP amplitudes following task training, two separate paired t-tests were conducted comparing mean amplitude values across electrodes for the N1 and P3 from pre- and post-training EEG sessions.

Although a commonly implemented approach in the mind-wandering literature is to examine how certain processes often captured by EEG measures differ during mind-wandering versus focused states, our experimental design did not provide sufficient data to address this question. Specifically, previous work has established that data within the 15 s prior to an experience sampling probe provide an accurate representation of a participant’s reported attention state at the probe while maximizing the amount of data to obtain reliable measures for analyses31. Using this time window, the mean number of EEG trials classified as mind-wandering were 39.62 (SD = 20.00) and 48.62 (SD = 24.14) in the pre- and post-training conditions, respectively, and the mean number of trials classified as focused were 52.58 (SD = 20.90) and 42.50 (SD = 24.24) in the pre- and post-training conditions, respectively. Given only 31% of participants (n = 8) had sufficient EEG trials76 for both mind-wandering and focused states in each condition, we chose not to analyze mind-wandering and focused brain states separately and instead used frequency of mind-wandering as a parametric variable in subsequent analyses.

Multiscale entropy (MSE)

Multiscale entropy (MSE) was used to estimate brain signal complexity and was calculated in MATLAB R2019a (MathWorks, Inc.) using the algorithm available at https://www.physionet.org/content/mse/42,43,77. Detailed descriptions of the applicability of MSE in analyzing neurophysiological signal complexity are available elsewhere42,43. Although a different method for MSE calculation has been proposed for situations where comparisons are made across groups in which spectral power differences in brain signal likely exist (e.g., young versus old individuals78), we employed the more commonly used estimation of MSE42,43 because our analyses are within-subject and for ease of comparison with previous work (e.g.,17,40,79). In addition, MSE values are influenced by the filtering parameters chosen78,80. For example, absolute MSE values at fine timescales may have been underestimated due to our use of a low-pass filter of 55 Hz80.

The MSE algorithm calculates sample entropy as a measure of the predictability, or regularity, of a signal at increasing timescales. The calculation of MSE involves two steps. First, data are resampled to create several discrete timescales. For each scale, an increasing number of datapoints within non-overlapping windows are averaged. In the current study, Scale 1 is the original time series (i.e., 2 ms windows in the context of a 500 Hz sampling rate), Scale 2 averages over two non-overlapping time points (i.e., 4 ms windows), and Scale 12 averages over 12 timepoints (i.e., 24 ms windows). Second, sample entropy is calculated for each timescale by evaluating the probability of repetitive patterns over time within each epoch based on two parameters to measure the regularity of corresponding time series. The pattern length, m = 2, means that two consecutive data points were used for pattern matching, and the tolerance level/similarity criterion, r = 0.50 (not to be interpreted as a Pearson r), means that the absolute amplitude difference between two data points should be less than or equal to 50% of the original time series standard deviation to be considered matching (see figures in Costa et al., 200543 for a visual depiction of the full calculation procedure). Briefly, the pattern matching procedure compares the amplitude values of two consecutive datapoints (m = 2), and if their absolute difference does not exceed the chosen similarity criterion (r = 0.50 × signal standard deviation), they are considered a match. If the absolute difference exceeds the similarity criterion, they are considered a non-match. MSE calculates the probability of these patterns of matches continuing to hold if the pattern length is increased to m + 1. This process is repeated across all possible sequences in the time series, and the ratio of the total number of matches for m and m + 1 is calculated, with the resulting value for each electrode and timescale ranging from 0 to 1. The greater the proportion of matches that extend to m + 1, the lower the entropy value, and the more predictable the underlying signal is. Conversely, higher entropy values represent greater temporal unpredictability43. MSE was calculated for participants at every electrode for each timescale within single trials and then averaged across all trials within pre- and post-training EEG conditions. Note that MSE is not influenced by the mean of evoked activity within the epoch, because it is capturing the temporal structure of the underlying signal, rather than absolute amplitude values.

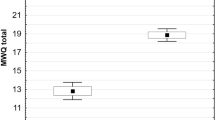

Behavioural outcomes associated with texture discrimination task (TDT) training. (a) The mean number of correct responses did not differ between pre- and post-training EEG sessions (consisting of 400 trials each). (b) The mean modal peripheral target angle (PTA) significantly decreased from pre- to post-training EEG sessions, indicating improved performance following training. (c) The mean response time to stimuli significantly decreased from pre- to post-training EEG sessions. (d) The mean proportion of total attention probes endorsed as “Mind-wandering” significantly increased from pre- to post-training EEG sessions. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01.

Partial least squares (PLS) analyses.

We used behaviour PLS (bPLS; https://www.rotman-baycrest.on.ca/index.php?section=345)81,82 in MATLAB 2019a (MathWorks, Inc.) to examine brain-behaviour correlations. Our ‘brain’ measure was MSE at each electrode and timescale. Our ‘behaviour’ variables included the amount of mind-wandering, modal PTA, N1 ERP amplitudes, and P3 ERP amplitudes. N1 amplitude values were inverted prior to bPLS analysis to enhance interpretability across ERPs, so that larger values corresponded with larger amplitudes, while smaller values indicated smaller amplitudes, regardless of peak polarity. Note that PLS was not used to test for relationships between the behaviour variables. We chose PLS because it is a multivariate, data-driven technique that allowed us to explore the entire data-space rather than confining our analyses to testing for a small subset of “expected” effects, given the relationships we were looking at are new in the literature. In general, PLS is similar to canonical correlation in relating two (or more) blocks of data but performs better when there is redundancy in the dependent measures, such as with MSE (and brain data generally).

bPLS uses singular value decomposition to identify latent variables (LVs) that show similarities or differences between conditions and brain-behaviour correlations (as described above). Each LV contains three vectors: the first vector (singular value) represents the strength of the effect expressed by the LV. The remaining two vectors represent experimental design and brain signal. The experimental design vector (design saliences) indicates the degree to which each behaviour measure within a condition is related to the brain-behavior correlation pattern identified in the LV. The brain signal vector (electrode saliences) contains numerical weights that, as a whole, identify the electrode/timescale pattern that optimally relates MSE to the variables it optimally correlates with in the LV.

Statistical assessment in PLS was carried out across two levels, and the resampling statistics used emphasize reproducibility and reliability81,83,84. First, the overall significance of each LV was determined by permutation testing85. The data were randomly shuffled between conditions and bPLS was recomputed on the permuted data. Five-hundred permutations were conducted to obtain a probability value for the number of times the singular value from each permuted dataset was greater than or equal to the singular value (from the first vector) obtained from the original data. An LV was considered significant if the observed singular value exceeded the permuted singular value in > 95% of the permutations (p < 0.05). Second, bootstrap resampling was used to estimate the stability of the identified pattern across participants83. Bootstrap samples were created by replacing 50% of participants with randomly resampled individuals but maintaining the same number of data entries as the original sample (i.e., a subset of participants was included more than once, while other participants were omitted). The pattern was considered reliable if the electrode salience value was not dependent on which combination of participants were included in each sample. This reliability was quantified by the bootstrap ratio (ratio of individual weights over estimated standard error), which are proportional to z-scores but should be interpreted as a confidence interval. We used 500 bootstrap samples and designated a minimum bootstrap ratio threshold of 2.0, corresponding to a 95% confidence interval (p < 0.05). As each comparison is computed in one mathematical step, corrections for multiple comparisons are not required.

Results

Behavioural analyses

Accuracy did not significantly differ between pre-training (M = 81.94% correct, SD = 1.62) and post-training (M = 81.06% correct, SD = 2.24) EEG sessions, t(25) = 1.64, p = 0.114, d = 0.32 (Fig. 2a), suggesting that task difficulty was successfully maintained. As illustrated in Fig. 2b, participants had a significantly lower modal PTA during the post-training (M = 11.7 degrees, SD = 2.8) as compared to the pre-training (M = 13.7 degrees, SD = 2.7) EEG session, t(25) = 3.56, p = 0.002, d = 0.70, indicating improved performance following training. As illustrated in Fig. 2c, participants had significantly faster response times to target stimuli during the post-training (M = 241.44 ms, SD = 100.08) as compared to the pre-training (M = 325.94 ms, SD = 126.29) EEG session, t(25) = 3.70, p = 0.001, d = 0.73. Finally, as illustrated in Fig. 2d, participants reported significantly more mind-wandering during the post-training (M = 54.98%, SD = 27.67) as compared to the pre-training (M = 43.28%, SD = 21.43) EEG session, t(25) = 2.62, p = 0.015, d = 0.51. We conducted two post-hoc exploratory repeated measures ANOVA analyses to examine the change in modal PTA (Supplementary Fig. S1) and mind-wandering frequency (Supplementary Fig. S2) across all four sessions. Relevant analytic details are provided in the Supplementary Information.

ERP analyses

The grand average N1 component trace across electrodes PO7, P7, P5, P6, P8, and PO8 is presented in Fig. 3a. Consistent with our hypothesis, N1 amplitudes were significantly reduced in the post-training (M = − 2.39, SD = 2.51) as compared to the pre-training (M = − 3.04, SD = 2.71) EEG session, t(25) = 3.03, p = 0.006, d = 0.59.

Grand average ERP component traces before and after texture discrimination task (TDT) training. (a) Grand average N1 trace measured at electrodes PO7, P7, P5, P6, P8, and PO8 and (b) grand average P3 trace measured at electrodes P3, P1, Pz, P2, and P4 while participants completed 400 trials of the TDT before (orange) and after (teal) two training sessions. The vertical line at time = 0 represents the onset of the stimulus. The shaded grey segments highlight the time windows in which average ERP amplitudes were calculated. The shaded ribbons around the traces illustrate the standard error of the mean amplitude values. Electrodes are referenced to the common average.

The grand average P3 component trace across electrodes P3, P1, Pz, P2, and P4 is presented in Fig. 3b. Consistent with our hypothesis, P3 amplitudes increased significantly in the post-training (M = 1.61, SD = 0.93) as compared to the pre-training (M = 1.07, SD = 1.06) EEG session, t(25) = 3.50, p = 0.002, d = 0.69. See Supplementary Fig. S3 for topographic maps of post-stimulus effects.

MSE analyses

The bPLS analysis identified two significant LVs. As illustrated in Fig. 4, LV1 (p < 0.001) showed that higher MSE across pre-and post-training was linked to greater mind-wandering before training, as well as a lower modal PTA (i.e., better performance) following training. The overall MSE pattern of this LV across electrodes and timescales is illustrated in Fig. 4b. Generally, the identified brain-behaviour relationship was most stable across distributed regions within medium (10–16 ms) to coarse (16–24 ms) timescales.

First partial least squares latent variable (LV 1) illustrating the relationship between multiscale entropy (MSE) and behaviour variables. (a) Bar graph depicting the significance of associations between MSE and behaviour variables identified in the first LV as determined by permutation testing. Pre-training behaviour variables are represented by solid bars and post-training behaviour variables are represented by textured bars. Orange bars represent significant positive correlations, purple bars represent significant negative correlations, and grey bars represent non-significant correlations between MSE and behaviour variables. Our results indicate significant correlations between pre-training mind-wandering, post-training modal PTA (i.e., performance), and MSE. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. (b) Statistical image plot (bootstrap ratio map) representing electrodes and timescales at which the correlations between MSE and pre-training mind-wandering and post-training performance were most stable (bootstrap threshold of 2.0, corresponding to a 95% confidence interval). Regions in orange highlight timescales and electrodes where MSE was higher with greater pre-training mind-wandering and better post-training performance (modal PTA). This effect was most stable across distributed regions, primarily within middle (10–16 ms) to coarse (16–24 ms) timescales.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, LV2 (p = 0.048) indicated that lower MSE at fine timescales (2–10 ms) and higher MSE at coarse timescales (16–24 ms) was associated with larger pre- and post-training N1 amplitudes, larger post-training P3 amplitudes, and greater post-training mind-wandering. Fine timescale MSE effects were most stable across frontal and parietal electrodes, and coarse timescale MSE effects appeared across widespread regions.

Second partial least squares latent variable (LV 2) illustrating the relationship between multiscale entropy (MSE) and behaviour variables. (a) Bar graph depicting the significance of associations between MSE and behaviour variables identified in the second LV as determined by permutation testing. Pre-training behaviour variables are represented by solid bars and post-training behaviour variables are represented by textured bars. Orange bars represent significant positive correlations and grey bars represent non-significant correlations between MSE and behaviour variables. Our results indicate significant correlations between pre- and post-training N1amplitudes, post-training P3 amplitudes, post-training mind-wandering, and MSE. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. (b) Statistical image plot (bootstrap ratio map) representing electrodes and timescales at which the correlations between MSE and pre- and post-training N1 amplitudes, post-training P3 amplitudes, and post-training mind-wandering were most stable (bootstrap threshold of 2.0, corresponding to a 95% confidence interval). Regions in purple highlight timescales and electrodes where lower MSE was associated with larger N1and P3 amplitudes and greater post-training mind-wandering, with this effect most stable at fine timescales (2–10 ms), primarily in frontal and parietal electrodes. Regions in orange highlight timescales and electrodes where higher MSE was associated with larger N1 and P3 amplitudes and greater post-training mind-wandering, with this effect most stable at coarse timescales (16–24 ms) across distributed regions.

Finally, we conducted two post-hoc exploratory behaviour PLS analyses to more directly examine the individual relationship between PTA change from pre- to post-training (corrected for initial performance level) and MSE (Supplementary Fig. S4), as well as the frequency of mind-wandering and MSE (Supplementary Fig S5). Relevant analytic details are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Discussion

In the current study, we made use of a well-established visual perceptual learning task49 to replicate improved perception and neural plasticity associated with training. We extended these findings by demonstrating that the extent of these perceptual gains are related to neural dynamics that are also associated with greater engagement in mind-wandering. Consistent with our behavioural hypothesis, participants performed significantly better following TDT training, also reporting more frequent mind-wandering with training. Consistent with our neural hypotheses, evoked responses were altered with training, as evidenced by reduced N1 and increased P3 component amplitudes, and more frequent mind-wandering was associated with higher brain signal complexity across widespread timescales and electrodes. Notably, these widespread increases in signal complexity were associated with improved performance following training, suggesting that higher neural flexibility may facilitate learning-related gains. Finally, increased N1 and P3 component amplitudes were associated with lower brain signal complexity at fine timescales and higher complexity at coarse timescales, highlighting the relationship between evoked brain activity and underlying signal dynamics. Taken together, our results suggest that higher widespread brain signal complexity may play a key functional role in both mind-wandering and performance improvements supported by neural plasticity.

Target discrimination improved and response time decreased following TDT training, which are hallmark features of visual perceptual learning tasks86. Improvements in perceptual acuity are driven by a selective reweighting process in the brain aimed to increase the signal-to-noise ratio of incoming visual input86,87. With training, communication between sensory and cognitive regions is improved, which allows for a more efficient process of selecting task-relevant information and filtering out irrelevant sensory representations87. Along with improved discrimination and faster performance, participants reported more frequent mind-wandering following training. Previous research has shown that individuals tend to adjust their levels of mind-wandering based on task demands, with greater frequency reported during less difficult and more familiar tasks88,89,90,91. Therefore, participants were likely able to allocate more attentional resources to task-unrelated thoughts as perceptual processing became more efficient with training26,27,28.

Training on the TDT was associated with changes in amplitude for two relevant sensory and cognitive ERP components, the N1 and the P3, respectively. As described above in the Method section, we were unable to reliably detect the P1 component, likely due to the non-foveal presentation of stimuli within all four quadrants of the visual field. We therefore did not perform analyses on the P1.

N1 component amplitudes decreased significantly following training, which has been reported in the literature following training on a wide range of perceptual learning tasks60,63,64,65,66,92. Our findings directly replicated those reported by Ahmadi and colleagues63, who found improved performance and decreased N1 amplitudes following training on a TDT. Larger N1 amplitudes have been linked to selectively attending toward a target visual stimulus93,94 and making visual discriminations within the locus of visual attention95. Decreased N1 amplitudes with training (along with improved performance) likely reflect improved efficiency of the selective reweighing process underlying perceptual gains, as individuals become better able to select and respond to relevant visual features within a stimulus.

P3 component amplitudes increased significantly following TDT training, which also replicates findings reported by Ahmadi and colleagues63 and has been reported in the broader visual perceptual learning literature60,65,66. The P3 component is thought to represent the integration of higher-level cognitive functions, such as working memory and attention, within information processing operations in response to a stimulus32. As proposed by Kelly and colleagues96, neural plasticity following task practice can be represented by a global redistribution of functional activations. According to this model, regions within a task network generally remain involved throughout training, but the levels of activation within these regions can either decrease or increase after moving from unskilled and effortful initial stages to more efficient performance96. Decreased activations within the task-specific network (i.e., N1 reductions) may represent greater perceptual processing efficiency following training, whereas increased activations (i.e., P3 enhancement) may represent recruitment of additional neural resources or increased response strength96. As such, following TDT training, the visual system may filter out unnecessary stimulus features with increased efficiency, whereas higher cognitive functions (i.e., attention and decision-making) may become enhanced with task mastery. Therefore, these changes in evoked responses associated with training may represent improved coordination between the sensory and cognitive systems underlying perception87.

Although we cannot assume causation of training effects due to the lack of a control task, the alignment of observed changes in ERPs and behaviour with outcomes reported in the literature62,63, along with previous research suggesting that perceptual learning effects are likely supported by plasticity54, led us to interpret these measures as sensitive indicators of training-related change.

The primary finding from our multiscale entropy analysis, represented in LV 1, showed that patterns of brain signal complexity associated with mind-wandering before task training may support subsequent learning-related perceptual gains. Specifically, we showed that higher distributed signal complexity, primarily within middle and coarse timescales, was associated with greater mind-wandering and better performance following training on the TDT. Our results complement those reported by Cnudde and colleagues17, who found that, compared to focused states, periods of mind-wandering were associated with increased signal complexity, primarily at coarse time scales. The authors concluded that the comparatively unconstrained thought patterns associated with mind-wandering may be represented in the decreased predictability of the underlying neural signal17. Consistent with this notion, Szostakiwskyj and colleagues97 observed higher brain signal complexity during rest (which presumably is more likely to be characterized by unconstrained thought processes) compared with on-task neural activity. Taken together, these results imply that when brain activity is not constrained to task demands, either during periods of rest or while engaged in mind-wandering, the underlying signal becomes increasingly flexible to support the exploration of new networks and the generation of new behaviours41,98,99.

Our findings represent a key novel extension to what has been previously reported. Although periods of mind-wandering were associated with greater neural flexibility, participants in Cnudde and colleagues’ study17 performed significantly worse on Navon’s task during these periods. In contrast, when participants in our study more frequently disengaged from external task demands, we observed a widespread increase in neural flexibility, which was linked with improved performance following training. Traditionally known to have adverse impacts on immediate task performance, our results suggest that greater engagement in mind-wandering is associated with a flexible brain state that may be adaptive in the context of long-term learning. Although the extensive literature related to ERP attenuation during perceptual decoupling26,27,31 would lead to predictions of impaired performance with mind-wandering, our findings highlight the utility of exploring mind-wandering in the context of signal complexity. While research supports the hypothesis that plastic changes both within and beyond the primary visual cortex are key substrates of perceptual learning54, our understanding of the neural mechanism driving this plasticity is limited. Given that higher brain signal complexity enables the exploration of new networks and behaviours98,99, and our finding that higher signal complexity associated with greater mind-wandering is related to improved performance over time, engaging in mind-wandering may promote transition to a neural state that is conducive to plasticity. It is crucial to note, however, that we are limited in our ability to make mechanistic inferences based on correlational data, and future research should explore the causal mechanisms underlying plasticity.

The results represented in LV 2 highlight the relationship between engagement with external task stimuli (i.e., ERPs) and mind-wandering after extensive task training. Here, we showed a direct relationship between evoked neural activity and signal complexity. Specifically, larger N1 and P3 component amplitudes were associated with lower complexity at fine timescales, with the strongest effects observed in frontal and parietal electrodes, and higher distributed coarse scale complexity. This pattern of signal complexity was also associated with greater mind-wandering following training. Generally, higher complexity at fine timescales reflects greater flexibility within local neuronal processing, whereas higher complexity at coarse timescales reflects greater flexibility across distal regions, indicative of increased global processing capacity44,45,46. The optimal level of neural complexity often depends on biological and environmental demands, with higher complexity associated with quicker transitions between neural network configurations and lower complexity with more efficient transmission of task-relevant information41,97,100. While conclusions based on scalp topography are limited by the spatial resolution of EEG, lower frontal and parietal fine scale complexity may reflect increased localized signal transmission within the frontoparietal network, which has been implicated in certain types of mind-wandering and self-generated thought broadly101,102. Considering that mind-wandering tends to increase when tasks become less difficult and more familiar88,89,90,91, and performance improved and mind-wandering increased following training on the TDT, participants were likely able to efficiently allocate attentional resources to both mind-wandering and external task stimuli with increased proficiency. Therefore, this pattern of lower signal complexity may represent the exertion of control to orient attention to self-generated thoughts during mind-wandering while maintaining engagement with task stimuli, as evidenced by larger ERPs. Further, the pattern of higher coarse scale complexity shows that increased global neural flexibility may represent efficient integration with widespread task-relevant regions during task performance. Taken together, our results suggest that more predictable and less noisy neural signals in regions relevant to mind-wandering, coupled with greater flexibility within distal task-relevant regions, support both increased evoked responses and the ability to engage in mind-wandering to a greater extent following training. Consequently, a shifting balance between fine and coarse scale temporal dynamics may support sufficient engagement with both external task demands and self-generated thoughts following improved task efficiency.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. We did not obtain a sufficient number of focused and mind-wandering responses to thought sampling probes to analyze these neural states separately. Thus, we could not compare behavioural and neural activity during periods of focused and mind-wandering states, as is commonly done in the literature. It is worth noting, however, that including mind-wandering as a parametric (as opposed to grouping) variable allowed our analyses to be sufficiently powered and aligned with our primary aim of examining the relationship between brain signal complexity and engagement in mind-wandering. Regardless, future research should increase task length to incorporate sufficient thought sampling probes to examine the neural activity associated with periods of mind-wandering during perceptual learning.

Although we recruited a multi-ethnic community-based sample, participants generally reported high levels of education (see Table 1). While higher education is unlikely to influence basic sensory functions such as visual perceptual processing, it may relate to factors such as motivation, executive functioning, and working memory, all of which are hypothesized to influence the experience of mind-wandering71,103,104,105. Future research should therefore include samples with representative distributions of educational backgrounds.

Finally, perceptual task difficulty was maintained at 80% accuracy across participants to mitigate the influence of baseline proficiency on tendency to engage in mind-wandering. However, participants’ subjective appraisal of task difficulty may still have influenced their responses to thought-sampling probes. Future work could benefit from independently assessing both perceived task difficulty and mind-wandering to parse apart their respective relationships with brain signal complexity.

Conclusions

In the current study, we demonstrated performance improvements and functional neural changes associated with visual perceptual training. Lower local and higher global signal complexity was related to larger evoked potentials and greater post-training mind-wandering. Higher widespread signal complexity was associated with greater mind-wandering and better performance following training. Our results suggest that neural flexibility associated with greater mind-wandering may have an important functional impact on performance improvements supported by plasticity.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. The science of mind wandering: empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 487–518 (2015).

Kane, M. J. et al. For whom the mind wanders, and when, varies across laboratory and daily life settings. Psychol. Sci. 28, 1271–1289 (2017).

Kawashima, I., Hinuma, T. & Tanaka, S. C. Ecological momentary assessment of mind-wandering: Meta-analysis and systematic review. Sci. Rep. 13, 2873 (2023).

Killingsworth, M. A. & Gilbert, D. T. A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science 330, 932–932 (2010).

Seli, P. et al. How pervasive is mind wandering, really?. Conscious. Cogn. 66, 74–78 (2018).

Fox, K. C. R., Spreng, R. N., Ellamil, M., Andrews-Hanna, J. R. & Christoff, K. The wandering brain: Meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of mind-wandering and related spontaneous thought processes. Neuroimage 111, 611–621 (2015).

Groot, J. M., Csifcsák, G., Wientjes, S., Forstmann, B. U. & Mittner, M. Catching wandering minds with tapping fingers: Neural and behavioral insights into task-unrelated cognition. Cereb. Cortex 32, 4447–4463 (2022).

Smallwood, J. et al. The neural correlates of ongoing conscious thought. Science 24, 102132 (2021).

Baird, B. et al. Inspired by distraction: Mind wandering facilitates creative incubation. Psychol. Sci. 23, 1117–1122 (2012).

Mooneyham, B. W. & Schooler, J. W. The costs and benefits of mind-wandering: a review. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 67, 11–18 (2013).

Randall, J. G., Oswald, F. L. & Beier, M. E. Mind-wandering, cognition, and performance: A theory-driven meta-analysis of attention regulation. Psychol. Bull. 140, 1411–1431 (2014).

Kam, J. W. Y. et al. On the relationship between unprompted thought and affective well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 150, 621–641 (2024).

Poerio, G. L., Totterdell, P. & Miles, E. Mind-wandering and negative mood: Does one thing really lead to another?. Conscious. Cogn. 22, 1412–1421 (2013).

Ruby, F. J. M., Smallwood, J., Engen, H. & Singer, T. How self-generated thought shapes mood–the relation between mind-wandering and mood depends on the socio-temporal content of thoughts. PLoS ONE 8, e77554 (2013).

Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S. & D’Argembeau, A. Concern-induced negative affect is associated with the occurrence and content of mind-wandering. Conscious. Cogn. 22, 442–448 (2013).

Aru, J., Drüke, M., Pikamäe, J. & Larkum, M. E. Mental navigation and the neural mechanisms of insight. Trends Neurosci. 46, 100–109 (2023).

Cnudde, K. et al. EEG complexity during mind wandering: A multiscale entropy investigation. Neuropsychologia 180, 108480 (2023).

Robertson, I. H., Manly, T., Andrade, J., Baddeley, B. T. & Yiend, J. ‘Oops!’: Performance correlates of everyday attentional failures in traumatic brain injured and normal subjects. Neuropsychologia 35, 747–758 (1997).

Leszczynski, M. et al. Mind wandering simultaneously prolongs reactions and promotes creative incubation. Sci. Rep. 7, 10197 (2017).

McVay, J. C. & Kane, M. J. Conducting the train of thought: working memory capacity, goal neglect, and mind wandering in an executive-control task. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 35, 196–204 (2009).

McVay, J. C. & Kane, M. J. Drifting from slow to “d’oh!”: Working memory capacity and mind wandering predict extreme reaction times and executive control errors. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 38, 525–549 (2012).

Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Maj, M., Van Der Linden, M. & D’Argembeau, A. Mind-wandering: phenomenology and function as assessed with a novel experience sampling method. Acta Psychol. 136, 370–381 (2011).

Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Catale, C. & D’Argembeau, A. Relationships between mind-wandering and attentional control abilities in young adults and adolescents. Acta Psychol. 148, 25–36 (2014).

Cheyne, J. A., Solman, G. J. F., Carriere, J. S. A. & Smilek, D. Anatomy of an error: a bidirectional state model of task engagement/disengagement and attention-related errors. Cognition 111, 98–113 (2009).

Smallwood, J., McSpadden, M. & Schooler, J. W. The lights are on but no one’s home: meta-awareness and the decoupling of attention when the mind wanders. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 14, 527–533 (2007).

Handy, T. C. & Kam, J. W. Y. Mind wandering and selective attention to the external world. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 69, 183–189 (2015).

Kam, J. W. Y. & Handy, T. C. The neurocognitive consequences of the wandering mind: A mechanistic account of sensory-motor decoupling. Front. Psychol. 4, 725 (2013).

Schooler, J. W. et al. Meta-awareness, perceptual decoupling and the wandering mind. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 319–326 (2011).

Kam, J. W. Y. et al. Slow fluctuations in attentional control of sensory cortex. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23, 460–470 (2011).

Posner, M. I. & Petersen, S. E. The attention system of the human brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 25–42 (1990).

Kam, J. W. Y., Rahnuma, T., Park, Y. E. & Hart, C. M. Electrophysiological markers of mind wandering: A systematic review. Neuroimage 258, 119372 (2022).

Polich, J. Updating P300: An integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clin. Neurophysiol. 118, 2128–2148 (2007).

Polich, J. Neuropsychology of P300, in The Oxford Handbook of Event-Related Potential Components (eds. Luck, S. J. & Kappenman, E. S.) 159–188 (Oxford University Press, Inc., 2012).

Jaswal, S. M. et al. The influence of acetaminophen on task related attention. Front. Neurosci. 13, 444 (2019).

Jin, C. Y., Borst, J. P. & Van Vugt, M. K. Predicting task-general mind-wandering with EEG. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci 19, 1059–1073 (2019).

Maillet, D. et al. Differential effects of mind-wandering and visual distraction on age-related changes in neuro-electric brain activity and variability. Neuropsychologia 146, 107565 (2020).

Smallwood, J., Beach, E., Schooler, J. W. & Handy, T. C. Going AWOL in the brain: mind wandering reduces cortical analysis of external events. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 20, 458–469 (2008).

Barron, E., Riby, L. M., Greer, J. & Smallwood, J. Absorbed in thought: the effect of mind wandering on the processing of relevant and irrelevant events. Psychol. Sci. 22, 596–601 (2011).

Deco, G., Jirsa, V. K. & McIntosh, A. R. Emerging concepts for the dynamical organization of resting-state activity in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 43–56 (2011).

McIntosh, A. R., Kovacevic, N. & Itier, R. J. Increased brain signal variability accompanies lower behavioral variability in development. PLoS Comput. Biol. 4, e1000106 (2008).

McIntosh, A. R. et al. The development of a noisy brain. Arch. Ital. Biol. 148, 323–227 (2010).

Costa, M., Goldberger, A. L. & Peng, C.-K. Multiscale entropy analysis of complex physiologic time series. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 068102 (2002).

Costa, M., Goldberger, A. L. & Peng, C.-K. Multiscale entropy analysis of biological signals. Phys. Rev. E. Stat. Nonlin. Soft. Matter. Phys. 71, 021906 (2005).

McIntosh, A. R. et al. Spatiotemporal dependency of age-related changes in brain signal variability. Cereb. Cortex 24, 1806–1817 (2014).

Wang, H., McIntosh, A. R., Kovacevic, N., Karachalios, M. & Protzner, A. B. Age-related multiscale changes in brain signal variability in pre-task versus post-task resting-state EEG. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 28, 971–984 (2016).

Vakorin, V. A., Lippé, S. & McIntosh, A. R. Variability of brain signals processed locally transforms into higher connectivity with brain dvelopment. J. Neurosci. 31, 6405–6413 (2011).

Mišić, B., Mills, T., Taylor, M. J. & McIntosh, A. R. Brain noise is task dependent and region specific. J. Neurophysiol. 104, 2667–2676 (2010).

Dorais, A. & Sagi, D. Contrast masking effects change with practice. Vis. Res. 37, 1725–1733 (1997).

Karni, A. & Sagi, D. Where practice makes perfect in texture discrimination: evidence for primary visual cortex plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 4966–4970 (1991).

Özgen, E. & Davies, I. R. L. Acquisition of categorical color perception: a perceptual learning approach to the linguistic relativity hypothesis. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 131, 477–493 (2002).

Sagi, D. Perceptual learning in vision research. Vis. Res. 51, 1552–1566 (2011).

Vogels, R. & Orban, G. A. The effect of practice on the oblique effect in line orientation judgments. Vis. Res. 25, 1679–1687 (1985).

Ball, K. & Sekuler, R. A specific and enduring improvement in visual motion discrimination. Science 218, 697–698 (1982).

Dosher, B. & Lu, Z.-L. Visual perceptual learning and models. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 3, 343–363 (2017).

Fiorentini, A. & Berardi, N. Perceptual learning specific for orientation and spatial frequency. Nature 287, 43–44 (1980).

Karni, A. & Sagi, D. The time course of learning a visual skill. Nature 365, 250–252 (1993).

Kumano, H. & Uka, T. Neuronal mechanisms of visual perceptual learning. Behav. Brain Res. 249, 75–80 (2013).

Yotsumoto, Y., Watanabe, T. & Sasaki, Y. Different dynamics of performance and brain activation in the time course of perceptual learning. Neuron 57, 827–833 (2008).

Wang, F., Zhong, X., Huang, J., Ding, Y. & Song, Y. Comparison of perceptual learning of real and virtual line orientations: An event-related potential study. Vis. Res. 93, 1–9 (2013).

Wang, Y., Song, Y., Qu, Z. & Ding, Y. Task difficulty modulates electrophysiological correlates of perceptual learning. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 75, 234–240 (2010).

Zhang, G.-L., Cong, L.-J., Song, Y. & Yu, C. ERP P1–N1 changes associated with Vernier perceptual learning and its location specificity and transfer. J. Vis. 13, 1–13 (2013).

Wang, F. et al. Predicting perceptual learning from higher-order cortical processing. Neuroimage 124, 682–692 (2016).

Ahmadi, M., McDevitt, E. A., Silver, M. A. & Mednick, S. C. Perceptual learning induces changes in early and late visual evoked potentials. Vis. Res. 152, 101–109 (2018).

Ding, Y., Song, Y., Fan, S., Qu, Z. & Chen, L. Specificity and generalization of visual perceptual learning in humans: An event-related potential study. NeuroReport 14, 587–590 (2003).

Song, Y. et al. An event-related potential study on perceptual learning in grating orientation discrimination. NeuroReport 18, 945–948 (2007).

Song, Y. et al. Neural substrates of visual perceptual learning of simple and complex stimuli. Clin. Neurophysiol. 116, 632–639 (2005).

Cohen, M. X. Analyzing Neural Time Series Data: Theory and Practice (The MIT Press, 2014).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191 (2007).

Protzner, A. B. et al. This is your brain on Scrabble: Neural correlates of visual word recognition in competitive Scrabble players as measured during task and resting-state. Cortex 75, 204–219 (2016).

Wang, H., Pexman, P. M., Turner, G., Cortese, F. & Protzner, A. B. The relation between Scrabble expertise and brain aging as measured with EEG brain signal variability. Neurobiol. Aging 69, 249–260 (2018).

Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. The restless mind. Psychol. Bull. 132, 946–958 (2006).

Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 134, 9–21 (2004).

Lopez-Calderon, J. & Luck, S. J. ERPLAB: An open-source toolbox for the analysis of event-related potentials. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 213 (2014).

Luck, S. J. An Introduction to the Event-Related Potential Technique (The MIT Press, 2005).

Luck, S. J. & Kappenman, E. S. ERP components and selective attention. In The Oxford Handbook of Event-Related Potential Components (eds Luck, S. J. & Kappenman, E. S.) 295–327 (Oxford University Press Inc, 2012).

Woodman, G. F. A brief introduction to the use of event-related potentials in studies of perception and attention. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 72, 2031–2046 (2010).

Goldberger, A. L. et al. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation 101, e215–e220 (2000).

Kosciessa, J. Q., Kloosterman, N. A. & Garrett, D. D. Standard multiscale entropy reflects neural dynamics at mismatched temporal scales: what’s signal irregularity got to do with it?. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16, e1007885 (2020).

Burles, F. et al. Revisiting mental rotation with stereoscopic disparity: a new spin for a classic paradigm. Brain Cogn. 136, 103600 (2019).

Courtiol, J. et al. The multiscale entropy: Guidelines for use and interpretation in brain signal analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 273, 175–190 (2016).

McIntosh, A. R. & Lobaugh, N. J. Partial least squares analysis of neuroimaging data: applications and advances. Neuroimage 23, S250–S263 (2004).

McIntosh, A. R., Bookstein, F. L., Haxby, J. V. & Grady, C. L. Spatial pattern analysis of functional brain images using partial least squares. Neuroimage 3, 143–157 (1996).

Efron, B. & Tibshirani, R. The bootstrap method for assessing statistical accuracy. Behaviormetrika 12, 1–32 (1985).

Kovacevic, N., Abdi, H., Beaton, D. & McIntosh, A. R. Revisiting PLS resampling: Comparing significance vs. reliability across range of simulations. In New Perspectives in Partial Least Squares & Related Methods (eds Abdi, H. et al.) 159–171 (Springer, 2013).

Good, P. Permutation Tests: A Practical Guide to Resampling Methods for Testing Hypotheses 2nd edn. (Springer, 2000).

Lu, Z.-L. & Dosher, B. A. Current directions in visual perceptual learning. Nat. Rev. Psychol 1, 654–668 (2022).

Dosher, B. A., Jeter, P., Liu, J. & Lu, Z.-L. An integrated reweighting theory of perceptual learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 13678–13683 (2013).

Barrington, M. & Miller, L. Mind wandering and task difficulty: the determinants of working memory, intentionality, motivation, and subjective difficulty. Psychol. Conscious. Theory Res. Pract. https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000356 (2023).

Mason, M. F. et al. Wandering minds: The default network and stimulus-independent thought. Science 315, 393–395 (2007).

Rummel, J. & Boywitt, C. D. Controlling the stream of thought: working memory capacity predicts adjustment of mind-wandering to situational demands. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 21, 1309–1315 (2014).

Zanesco, A. P., Denkova, E. & Jha, A. P. Mind-wandering increases in frequency over time during task performance: An individual-participant meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000424 (2024).

Song, Y., Ding, Y., Fan, S. & Chen, L. An event-related potential study on visual perceptual learning under short-term and long-term training conditions. NeuroReport 13, 2053–2057 (2002).

Luck, S. J. et al. Effects of spatial cuing on luminance detectability: psychophysical and electrophysiological evidence for early selection. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 20, 887–904 (1994).

Luck, S. J., Woodman, G. F. & Vogel, E. K. Event-related potential studies of attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4, 432–440 (2000).

Vogel, E. K. & Luck, S. J. The visual N1 component as an index of a discrimination process. Psychophysiol. 37, 190–203 (2000).

Kelly, C., Foxe, J. J. & Garavan, H. Patterns of normal human brain plasticity after practice and their implications for neurorehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 87, 20–29 (2006).

Szostakiwskyj, J. M. H., Willatt, S. E., Cortese, F. & Protzner, A. B. The modulation of EEG variability between internally- and externally-driven cognitive states varies with maturation and task performance. PLoS ONE 12, e0181894 (2017).

Deco, G., Jirsa, V. K. & McIntosh, A. R. Resting brains never rest: Computational insights into potential cognitive architectures. Trends Neurosci. 36, 268–274 (2013).

Garrett, D. D. et al. Moment-to-moment brain signal variability: A next frontier in human brain mapping?. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 610–624 (2013).

Ponce-Alvarez, A., Thiele, A., Albright, T. D., Stoner, G. R. & Deco, G. Stimulus-dependent variability and noise correlations in cortical MT neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 13162–13167 (2013).

Christoff, K., Gordon, A. M., Smallwood, J., Smith, R. & Schooler, J. W. Experience sampling during fMRI reveals default network and executive system contributions to mind wandering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8719–8724 (2009).

Turnbull, A. et al. Left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex supports context-dependent prioritisation of off-task thought. Nat. Commun. 10, 3816 (2019).

McVay, J. C. & Kane, M. J. Does mind wandering reflect executive function or executive failure? Comment on Smallwood and Schooler (2006) and Watkins (2008). Psychol. Bull. 136, 188–197 (2010).

Seli, P., Schacter, D. L., Risko, E. F. & Smilek, D. Increasing participant motivation reduces rates of intentional and unintentional mind wandering. Psychol. Res. 83, 1057–1069 (2019).

Soemer, A. & Schiefele, U. Working memory capacity and (in)voluntary mind wandering. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 27, 758–767 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grants to A.B.P. (05299–2020) and J.W.Y.K. (2020-00076). L.K. was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research CGS-M and Hotchkiss Brain Institute scholarships.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.K. drafted the manuscript with guidance from A.B.P. and J.W.Y.K. and contributed to the conceptualization of the project and the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. F.B. contributed to the conceptualization of the project and created new software for data acquisition. K.C. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. M.K. contributed to the acquisition of data. A.B.P. and J.W.Y.K. contributed to the conceptualization of the project, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation. All authors critically reviewed and approved of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krile, L., Burles, F., Chohan, K. et al. Brain signal complexity tracks mind-wandering and visual perceptual learning. Sci Rep 15, 39839 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23562-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23562-2