Abstract

We investigate the degradation physics of AlGaN-based UV-C LEDs emitting at 265 nm, by combined experimental measurements and numerical simulations. We demonstrate that: (i) during long-term operation, devices show degradation in the optical emission, which is more prominent at low measuring current levels; (ii) a strong correlation was found between the emission decrease and the increase in the forward leakage current, which suggests that the same process is responsible for the electrical and optical degradation; (iii) the observed long-term optical degradation was reproduced by numerical simulations, as being due to the increase in the defect density in the QW during the ageing, demonstrating the impacting role of SRH recombination on device reliability. (iv) The degradation kinetics follow the square-root of stress time. By solving Fick’s differential equation near the quantum well, we ascribed degradation to the out-diffusion of hydrogen from the quantum well region, leading to the activation of non-radiative recombination centers, through the de-hydrogenation of point-defects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

AlGaN-based deep ultra violet (UV) light emitting diodes (LEDs) are crucial for applications in disinfection and water purification1,2,3, sterilization4,5,6, in the field of communication7,8,9 and for bioagent detection10. Compared to conventional mercury gas-discharge lamps, LEDs emitting in the UV-C spectral range at 265 nm to 275 nm have exceptional properties, such as tunable optical power, lower footprint and a much higher environmental friendliness11,12. However, their market penetration still finds some roadblocks, mainly due to the limited lifetime of such solid-state emitters12,13,14. Several physical degradation mechanisms responsible for the short- and long-term reduction in optical emission have been identified and discussed by the scientific community, most of which are related to the generation or activation of point defects15,16,17,18. Such defects can act as non-radiative recombination centers19, thus leading to a decrease in the internal quantum efficiency20 or to the increase in the forward leakage current21. However, the physical origin of these defects and the specific mechanism involved in the worsening of UV-C LED performance still need to be clarified.

This paper advances our previous studies21,22 in which only the electrical characteristics were investigated, focusing on the reasons for the optical degradation of UV-C LED devices, by combining experimental analysis and numerical simulations. Differently from previous reports23,24,25, this analysis finds a strong correlation between the optical and electrical degradation processes in UV-C single quantum well LEDs, suggesting the presence of a unique degradation mechanism. In order to identify the latter, we succeeded in defining a model able to reproduce the optical degradation of the device simultaneously at different measuring current levels. Thanks to a careful calibration of the model, this approach allows to extrapolate an estimation of the defect’s density trend within the active region during a constant current ageing test. The outcome of the analysis suggests the presence of an impurity diffusion process, possibly related to hydrogen, as the driving process for the observed degradation of the device.

Experimental details

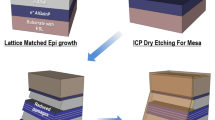

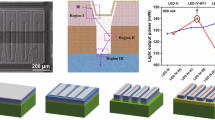

The analyzed LEDs have a nominal emission wavelength of 265 nm and an area of \(\:0.1\:m{m}^{2}.\) A schematic drawing of the structure is reported in Fig. 1. The devices are grown by metalorganic vapor phase epitaxy (MOVPE) on high temperature annealed (HTA) epitaxially laterally-overgrown (ELO) AlN on sapphire, with a threading dislocation density of \(\:9\:\cdot\:{10}^{8}\:{\text{c}\text{m}}^{-2}\)26. Above this layer, the epitaxial stack continues with a 400 nm thick AlN layer, followed by a 25 nm thick AlGaN Si-doped layer. Then, \(\:1\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) Si-doped Al0.76Ga0.24N buffer layer and 100 nm Al0.65Ga0.35N Si-doped transition layer are grown, followed by a 200 nm thick Si-doped Al0.65Ga0.35N contact layer featuring a doping density \(\:{\text{N}}_{\text{D}}=4\:\cdot\:{10}^{18}\:c{m}^{-3}\). On top of the contact layer, a 38 nm thick Si-doped Al0.62Ga0.38N “first barrier” is grown, followed by a single 6 nm thick Al0.48Ga0.52N quantum well (QW) and a second 10 nm thick u.i.d. Al0.62Ga0.38N “last barrier”. An undoped 10 nm thick Al0.8Ga0.2N interlayer separates the p-region from the last barrier. The p-side consists of 25 nm p-doped Al0.75Ga0.25N electron blocking layer (EBL), with a nominal Mg concentration of \(\:1\:\cdot\:{10}^{19}\:c{m}^{-3},\) and of a p-doped 230 nm thick GaN layer featuring a Mg concentration of \(\:6\:\cdot\:{10}^{19}\:c{m}^{-3}\). Finally, the LEDs were processed by standard micro-fabrication techniques using Pd/Au p-contacts and V/Al based n-contacts27. Additional details on similar structures and on the fabrication process can be found in21,28.

Experimental results

In order to investigate the degradation mechanisms affecting the device during operation, we carried out constant current stress tests at \(\:100\:\text{A}\cdot\:{\text{c}\text{m}}^{-2}\) (100 mA) for 20 000 min (more than 330 h), at a heatsink temperature of 25 °C. The investigated sample has been chosen after a preliminary characterization during which several tens of devices have been analyzed in order to select a single device representative of the average characteristic of these LEDs. During the aging experiment, both the optical and electrical characteristics of the LED were monitored through current–voltage (I–V) and optical power–current (L–I) measurements, carried out at exponentially-spaced stress time intervals. The voltage and current were imposed and read by a source meter, whereas the optical power was monitored by means of a Si-based amplified photodiode.

Figure 2 reports the variation in the optical power, measured at different current levels, derived from the L-I measurement performed at different time intervals during the constant current stress at \(\:100\:\text{A}\cdot\:{\text{c}\text{m}}^{-2}\). As can be noticed, the degradation kinetics strongly depend on the measuring (test) current level. At higher measuring current levels, the trend is characterized by the presence of a positive ageing (recovery) phase, during which the optical emission increases up to + 15% with respect to the initial value. This recovery phase apparently ends after 500 –1000 min of stress. Subsequently, a significant optical degradation is observed at all measuring current levels, especially at low test currents, causing an optical power reduction of 80% with respect to the initial value. Hence, the experimental data suggest the coexistence of two opposing mechanisms, whose interplay determines the observed trend of the optical power.

As far as the recovery process is concerned, a well-known mechanism that typically induces similar variations in InGaN/GaN LEDs during their early stage of operation29,30, is represented by the breaking of Mg–H complexes located at the p-side. Such events can increase the conductivity of the p-doped quasi-neutral regions, and improve the efficiency of hole injection into the QW31,32. Another possible explanation could be related to the stress-induced generation of shallow charged defects at the heterointerfaces contained within the active region, or within neighboring layers33. This process can screen the effect of the piezoelectric polarization34,35, thus altering the local band bending, eventually impacting the injection efficiency36,37. This is true, in particular, for LEDs featuring wide QWs38,39, which are very sensitive to changes in the overlap between electron and holes wavefunctions, and at high injections levels. In this paper, no detailed model will be presented for this positive ageing process, since the focus is the electro-optical degradation of the LEDs.

With regard to the optical degradation (negative ageing), it is well known that current stress can induce the generation of point defects within the active region of a LED15,16,17,18. These defects can act as non-radiative recombination centers, significantly reducing the optical efficiency of the device40,41, especially at low current levels where the recombination is dominated by non-radiative SRH process. The SRH rate can be approximated as \(\:An\), where A is proportional to the defect concentration in the QW (i.e., \(\:\propto\:{N}_{T,QW}\))42. Thus, the trend of the optical power at low currents represents an indicator of the defect density variation occurring in the active region during aging. However, the physical mechanism responsible for the rapid increase in the defect density in UV-C LEDs is still under debate in the literature.

In our previous study21, we showed that the electrical characteristic of these devices exhibit also a significant increase in the forward leakage current, due an increase in defect density in the interlayer, probably caused by a diffusion process, that contribute to raise the trap-assisted tunneling (TAT). Thus, if the optical emission decrease originated from the same mechanism responsible for the increase in the forward leakage current, we would expect to observe a correlation between the leakage current variation, measured in the bias region where TAT dominates22, and the reduction in the optical emission at low current, where the SRH recombination is dominant. This is clearly evidenced by Fig. 3, which reports the normalized leakage current at 3 V as function of the normalized optical power emission at 2 mA: the strong correlation between the trends of the two quantities indicates that the same defect propagation, or generation, mechanism is responsible for both the previously described electrical and optical degradation processes. It is worth stressing that this process involves traps located in different layers, as the defects located in the QW affects the optical emission and the ones in the interlayer generate the TAT, even though they probably are the same kind of traps. Since the mechanism responsible for the defect increase in the interlayer has already been investigated21, in the following analysis we focus on the optical degradation, investigating the role of the increase in the defect density within the active region in the optical power decrease, and on the analysis of the related processes.

Results of numerical simulations

To further support this hypothesis, we implemented and simulated the device structure by means of the TCAD Sentaurus suite from Synopsys Inc. The doping of the different layers was included by placing the donor or acceptor traps (Si and Mg) at their characteristic thermal activation energies. Specifically, silicon was placed at \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{C}}-24\:\text{m}\text{e}\text{V}\) for n-doped AlGaN layers, whereas magnesium was placed at \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{V}}+150\:\text{m}\text{e}\text{V}\) and \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{V}}+380\:\text{m}\text{e}\text{V}\) for the p-GaN layer and the EBL, respectively43,44,45. All the main recombination processes were activated: the radiative recombination coefficient was set to \(\:5\times\:{10}^{-11}{cm}^{3}{s}^{-1}\)46, whereas an Auger–Meitner coefficient of \(\:5\times\:{10}^{-31}{cm}^{6}{s}^{-1}\) was selected, according to the values reported in47,48. SRH recombination, instead, has been implemented by including deep-levels near midgap21, at variable densities. Finally, also the piezoelectric polarization was enabled with an activation percentage of 0.7. The simulations are carried out by solving self-consistently coupled Schrodinger-Poisson equations with a 2D scheme.

Simulated band diagram of the investigated structure at two different current levels: 2 mA (a) and 50 mA (b). With equal defect density in the QW, the impact of defects on the radiative efficiency prevails at low current, where we can spot a reduction of 80% (at 2 mA), against a 20% reduction at 50 mA.

Figure 4 (a) and (b) report the simulated band diagram of the device at 2 mA and 50 mA, as well as the respective carrier densities and local rates of radiative recombination. The defect density in the QW (\(\:{\text{N}}_{\text{T},\text{Q}\text{W}}\)) has been set at two different values: \(\:5\times\:{10}^{15}{cm}^{-3}\) and \(\:2.45\times\:{10}^{16}{cm}^{-3}\), i.e. the typical defect density of an unaged or slightly aged sample estimated by means of deep level optical spectroscopy (DLOS)21 and a higher one, respectively. The simulations show that this specific structure exhibits a high density of electrons in the QW around \(\:1-2\times\:{10}^{19}{cm}^{-3}\) even at 2 mA, whereas the hole density is an order of magnitude lower. The simulated increase in defect density leads to a reduction in the carrier density, and therefore in the rate of radiative recombination. This is due to an increase in the SRH recombination which reduces the effective carrier lifetime. This effect is much stronger at lower injection levels, since holes are present in a lower density, and non-radiative SRH recombination is favored over radiative recombination. It is worth noticing that the rate of SRH recombination has no strong dependence on the energy level of the defects in wide-bandgap semiconductors, as long as the trap level is sufficiently far from the conduction or valence band edges49, consistent with our previous assumption on the energetic placement of the states. It is also important to pinpoint that, for a fixed capture cross-section value \(\:({\sigma\:=\sigma\:}_{n}={\sigma\:}_{p})\), the recombination rate is proportional to the product of the cross-section and the defect density\(\:,\:i.e.\:\propto\:{N}_{T}\sigma\:\)., as we can observe from the implemented equation for the rate of SRH recombination36:

where \(\:{v}_{th}\) is the carrier thermal velocity, \(\:{N}_{T}\) the defect density, \(\:{\sigma\:}_{n}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{p}\) are the scattering cross-sections of the trap for electrons and holes and \(\:{n}_{i,eff}={p}_{i,eff}\) is the intrinsic carrier density. Finally \(\:{n}_{1}={N}_{C}{e}^{\left(\frac{{E}_{T}-{E}_{C}}{{K}_{B}T}\right)}\) and \(\:{p}_{1}={N}_{V}{e}^{\left(\frac{{E}_{V}-{E}_{T}}{{K}_{B}T}\right)}\) where \(\:{N}_{C}\) and \(\:{N}_{V}\) are the carrier effective densities of states, \(\:{E}_{T}\) the trap energy level, T the temperature, \(\:{E}_{C}\:\)and\(\:\:{E}_{V}\) respectively the conduction and valence energy level. For this analysis, the defect density has been chosen according to experimental measurements in similar samples21,50 and the cross-section has been considered as a fitting parameter choosing it at \(\:{6\times\:10}^{-16}\:{cm}^{2}\), a value also consistent with the typical cross-section for defects in the forbidden gap in GaN51.

With the purpose of confirming the hypothesis of a stress-induced increase in point defects concentration within the QW, we followed the procedure described in the following. First, we imposed an initial defect density within the active region equal to \(\:5\times\:{10}^{15}{cm}^{-3}\), in agreement with experimental data21. Subsequently, the defect density \(\:{N}_{T}\) was fitted to reproduce the decay of optical power with operation time. As our simulation model describes only the degradation but not the recovery mechanism, we normalize the output power to the values after 1000 min, in order to exclude the initial recovery effect, which ends after \(\:1000\) min (see Fig. 2). It must be noted that the increase in defect density within the QW starts at the beginning of the stress, as is clearly observable from the decrease in the optical emission at low measuring currents, but its effects at high currents are masked by the recovery process. Both the experimental and simulated data are reported in Fig. 5. The values of \(\:{N}_{T}\) extracted from the simulations are reported in Table 1.

A good agreement was found between experimental and modeling data, extending for more than one order of magnitude of bias currents. Furthermore, it is worth underlining that the simulation reproduces the trend at different currents just increasing the single parameter of trap density. These results confirm that (i) the measured data can be well reproduced by an increase in defect density in the QW during operation and (ii) this observed degradation is mainly caused by an increase in the SRH recombination rate. Finally, (iii) the results allow to quantify the variation in the concentration of the defects \(\:{N}_{T}\) contributing to the process.

Physical interpretation and final considerations

The causes of this increase in defect density in the QW is still under investigation. Recently, Ma et al.40 found, in similar AlGaN-based MQW structures, that high current stress can induce the propagation of point defects within the active region, especially in the QW closest to the p-side, suggesting the existence of a diffusion process originating in this device region. They also found that TD-related defects do not represent the dominant non-radiative recombination centers for AlGaN-based LEDs, but rather contribute to the generation of point defects, associated with nonradiative recombination centers, possibly caused by a diffusion process taking place along the dislocation line. Similar considerations were made by Ruschel et al. in31: in that case, optical degradation was assumed to be caused by hydrogen diffusion. Owing to the specific growth conditions, the p-side and the adjacent layers are typically rich of residual hydrogen, bound to the Mg acceptors [36] or with negatively charged point defects, such as group-III vacancies37, forming defect complexes. During ageing, high energy carriers, generated by Auger-Meitner recombination processes52, can provide sufficient energy to break these H-related defect complexes, resulting in the activation of point defects within the interlayer and the active region which were previously passivated by hydrogen. This mechanism has been experimentally proposed by Glaab et al.53,54 and Chichibu et al.18 by means of SIMS measurements. They found that the initial H concentration inside the EBL and the p-GaN layer significantly decreases, especially during the first hours of the stress, and H atoms migrate from these regions toward the n-side. In addition to that, by leveraging positron annihilation spectroscopy analysis (PAS), Chichibu et al. in18 also found that hydrogen migration and optical degradation were correlated with the increase in concentration of vacancy-related point-defects.

However, such hypothesis has not been supported by numerical calculations so far. To bridge this gap, we developed a 1D model, to verify that the degradation kinetics observed from 1000 min can be effectively reproduced by an impurity diffusion process, originating in the region with the highest recombination rate, i.e. the QW. We consider that, prior to stress, a high density of hydrogenated defects (vacancies) is present within the device structure and in the QW40. Hydrogenated vacancies do not severely impact the non-radiative recombination rate, until one or more hydrogen atoms are removed18,55. During the ageing of the device, Auger-Meitner recombination processes, favored by the high carrier density of this region, provide sufficient energy to break the bonds between the hydrogen and defects52. The \(\:{H}^{+}\)atoms become free to diffuse outside the QW, leaving the defects able to act as non-radiative recombination centers, thus increasing the SRH recombination rate, as observed in the simulations. Assuming that the initial \(\:{H}_{0}\) density in the QW is constant, we solved numerically the Fick’s diffusion equation, through the finite difference method, to determine the variation over time of the hydrogen profile.

In this formula, \(\:D\) is the diffusion coefficient and \(\:H(x,t)\) is the hydrogen profile.

The results (Fig. 6) showed that with increasing stress time, the hydrogen concentration in the quantum well decreases, as H atoms diffuse towards the neighboring layers, leaving behind de-hydrogenated vacancies, acting as non-radiative recombination centers. Remarkably, the decrease in hydrogen concentration within the QW was found to (a) follow the square-root of stress time, similar to the optical degradation kinetics of several nitride-based devices investigated in the literature15,56; (b) to nicely match the variation in trap-density estimated by simulating by Sentaurus the optical degradation of the devices. In fact, the density of the active defects inside the QW is \(\:{N}_{T}\left(t\right)=\:{N}_{0}-H\left(t\right)\) where \(\:{N}_{0}\) is the initial density of the hydrogenated vacancies. For the calculation, the initial hydrogen concentration \(\:{N}_{0}\) and the diffusion coefficient \(\:D\) have been taken as fitting parameters. From this assumption the simulated hydrogen density is estimated as\(\:\:H\left(t\right)=\:{N}_{0}-{N}_{T}\left(t\right)\). We note here that \(\:{N}_{0}\) is in agreement with the simulations and experimental estimations21, whereas the value of D almost matches the values reported in the literature for hydrogen diffusion in gallium nitride56,57.

As discussed above, this process does not take place only in the active region but it is plausible that this diffusion process involves a wider region, and the activated defects have different effects in the device performance depending on the layer they are in.

Conclusions

In summary, we analyzed the degradation of AlGaN based UV-C LEDs by combining experimental measurements and numerical simulations. From the optical characterization performed during a constant current stress at \(\:100\:\text{A}\cdot\:{\text{c}\text{m}}^{-2}\), we observed the presence of two different mechanisms that affect the optical emission of the devices. The first is an optical recovery process (positive ageing), mainly visible at high measuring currents, whereas the second one is a degradation process (negative ageing), which prevails for long stress time and at low bias current levels.

Focusing on the negative ageing process, we found that it has a strong correlation with the increase in forward leakage current, suggesting that both processes are related to the increase in the defect density, involving the interlayer (thus enhancing forward current leakage), and the quantum well region (where it favors non-radiative recombination).

In order to investigate the role of the defects within the active region, we reproduced the structure by means of a TCAD model that succeeded in emulating the optical behavior of the device. In particular, a good matching between the simulated and experimental optical trends at different currents could be achieved by considering only an increase in trap density within the QW, indicating that defect generation/activation in the active region is of crucial importance in the degradation process affecting device performance. With the purpose of identifying their physical origin we numerically solved Fick’s diffusion law. The excellent matching observed between the simulated data and the Fick’s law indicates that the degradation is compatible with an out-diffusion of hydrogen - previously bound to defect complexes - from the QWs. These results support the hypothesis that degradation is related to the de-hydrogenation of vacancies, promoted by the non-radiative recombination events taking place in the quantum well.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Würtele, M. A. et al. Application of GaN-based ultraviolet-C light emitting diodes–UV LEDs–for water disinfection. Water Res. 45, 1481–1489 (2011).

Kneissl, M. & Rass, J. III-Nitride Ultraviolet Emitters, vol. 227 (Springer, 2016).

Wang, C. P. & Liao, J. Y. Effect of UV-C LED arrangement on the sterilization of Escherichia coli in planar water disinfection reactors. J. Water Process. Eng. 56, 104399 (2023).

Glaab, J. et al. Skin tolerant inactivation of multiresistant pathogens using far-UVC leds. Sci. Rep. 2021. 111 (11), 1–11 (2021).

Lee, Y. W., Yoon, H., Do, Park, J. H. & Ryu, U. C. Application of 265-nm UVC LED lighting to sterilization of typical gram negative and positive bacteria. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 72, 1174–1178 (2018).

Luo, W. et al. Watts-level ultraviolet-C LED integrated light sources for efficient surface and air sterilization. J. Semicond. 43, 072301 (2022).

Gong, C. et al. 266 nm ultraviolet communication under unknown interference using UVC micro-LED. Opt. Express 31, 16406–16422 (2023).

Guo, L., Guo, Y., Wang, J. & Wei, T. Ultraviolet communication technique and its application. J. Semicond. 42, 081801 (2021).

Shan, X. et al. Multifunctional Ultraviolet-C Micro-LED with monolithically integrated photodetector for optical wireless communication. J. Light Technol. 40, 490–498 (2022).

Won, W. S. et al. UV-LEDs for the disinfection and Bio-Sensing applications. Int. J. Precis Eng. Manuf. 2018 1912. 19, 1901–1915 (2018).

Amano, H. et al. The 2020 UV emitter roadmap. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 53, 503001 (2020).

Loveless, J. et al. Performance and reliability of state-of-the-art commercial UVC light emitting diodes. Solid State Electron. 209, 108775 (2023).

Trivellin, N. et al. Reliability of commercial UVC leds: 2022 State-of-the-Art. Electron. 2022. 11 (11), 728 (2022).

Yoshikawa, A. et al. Improve efficiency and long lifetime UVC leds with wavelengths between 230 and 237 Nm. Appl. Phys. Express. 13, 022001 (2020).

Monti, D. et al. High-Current stress of UV-B (In)AlGaN-Based leds: Defect-Generation and diffusion processes. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 66, 3387–3392 (2019).

Ma, Z., Cao, H., Lin, S., Li, X. & Zhao, L. Degradation and failure mechanism of AlGaN-based UVC-LEDs. Solid State Electron. 156, 92–96 (2019).

Maraj, M., Min, L. & Sun, W. Reliability analysis of AlGaN-based deep UV-LEDs. Nanomaterials 12, 3731 (2022).

Chichibu, S. F. et al. Operation-induced degradation mechanisms of 275-nm-band AlGaN-based deep-ultraviolet light-emitting diodes fabricated on a Sapphire substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 201105 (2023).

Monti, D. et al. Defect-Related degradation of AlGaN-Based UV-B leds. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 64, 200–205 (2017).

Monti, D., Meneghini, M., De Santi, C., Meneghesso, G. & Zanoni, E. Degradation of UV-A leds: physical origin and dependence on stress conditions. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 16, 213–219 (2016).

Roccato, N. et al. Modeling the electrical degradation of AlGaN-based UV-C leds by combined deep-level optical spectroscopy and TCAD simulations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 161105 (2023).

Roccato, N. et al. Modeling of the electrical characteristics and degradation mechanisms of UV-C leds. IEEE Photonics J. 16, 1–6 (2024).

Gong, M. et al. Study on the degradation performance of AlGaN-Based deep ultraviolet leds under thermal and electrical stress. Coatings. 14, 904 (2024).

Maraj, M., Min, L. & Sun, W. Reliability analysis of AlGaN-based deep UV-LEDs. Nanomaterials 12 (2022).

Letson, B. C. et al. Review—Reliability and degradation mechanisms of deep UV AlGaN leds. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 12, 066002 (2023).

Susilo, N. et al. Improved performance of UVC-LEDs by combination of high-temperature annealing and epitaxially laterally overgrown AlN/sapphire. https://doi.org/10.1364/PRJ.385275 (2020).

Sulmoni, L. et al. Electrical properties and microstructure formation of V/Al-based n-contacts on high Al mole fraction n-AlGaN layers. Photonics Res. 8, 1381–1387 (2020).

Piva, F. et al. Degradation of AlGaN-based UV-C SQW leds analyzed by means of capacitance deep-level transient spectroscopy and numerical simulations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 181102 (2023).

Liu, L. et al. Efficiency degradation behaviors of current/thermal co-stressed GaN-based blue light emitting diodes with vertical-structure. J. Appl. Phys 111 (2012).

Roccato, N. et al. Modeling the electrical characteristic of InGaN/GaN blue-violet LED structure under electrical stress. Microelectron. Reliab. 138, 114724 (2022).

Ruschel, J. et al. Reliability of UVC leds fabricated on AlN/sapphire templates with different Threading dislocation densities. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 241104 (2020).

Meneghini, M. et al. Reversible degradation of GaN LEDs related to passivation. Annu. Proc. Reliab. Phys. 457–461. https://doi.org/10.1109/RELPHY.2007.369933 (2007).

Roccato, N. et al. Investigation and modeling of the role of interface defects in the optical degradation of InGaN/GaN leds. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/AD7039 (2024).

Bochkareva, N. I. et al. The effects of interface States on the capacitance and electroluminescence efficiency of InGaN/GaN light-emitting diodes. Semicond. 2005 397. 39, 795–799 (2005).

Schaake, C. A. et al. A donor-like trap at the InGaN/GaN interface with net negative polarization and its possible consequence on internal quantum efficiency. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 28, 105021 (2013).

Zhao, H., Liu, G., Zhang, J., Arif, R. A. & Tansu, N. Analysis of internal quantum efficiency and current injection efficiency in III-nitride light-emitting diodes. IEEE/OSA J. Disp. Technol. 9, 212–225 (2013).

Wang, C. H. et al. Hole injection and efficiency droop improvement in InGaN/GaN light-emitting diodes by band-engineered electron blocking layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 261103 (2010).

Zhu, S. et al. Influence of quantum confined Stark effect and carrier localization effect on modulation bandwidth for GaN-based leds. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 171105 (2017).

Yu, H. et al. Enhanced performance of an AlGaN-Based Deep-Ultraviolet LED having graded quantum well structure. IEEE Photon. J. 11 (2019).

Ma, Z. et al. The influence of point defects on AlGaN-based deep ultraviolet leds. J. Alloys Compd. 845, 156177 (2020).

Muhin, A. et al. Radiative recombination and carrier injection efficiencies in 265 Nm deep ultraviolet Light-Emitting diodes grown on AlN/Sapphire templates with different defect densities. Phys. Status Solidi. 220, 2200458 (2023).

Renso, N. et al. Degradation of InGaN-based leds: demonstration of a recombination-dependent defect-generation process. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 185701 (2020).

Zhao, C. Z., Wei, T., Chen, L. Y., Wang, S. S. & Wang, J. The activation energy for Mg acceptor in AlxGa1-xN alloys in the whole composition range. Superlattices Microstruct. 109, 758–762 (2017).

Nakano, Y. & Jimbo, T. Electrical properties of acceptor levels in Mg-Doped GaN. Phys. Status Solidi. 0, 438–442 (2003).

Silvestri, L., Dunn, K., Prawer, S. & Ladouceur, F. Hybrid functional study of Si and O donors in wurtzite AlN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 122109 (2011).

Qian, Z. et al. Analysis of the efficiency improvement of 273 Nm AlGaN UV-C micro-LEDs. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 55, 195104 (2022).

Ni, R. et al. Light extraction and Auger recombination in AlGaN-Based ultraviolet Light-Emitting diodes. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 32, 971–974 (2020).

Pant, N. et al. Carrier confinement and alloy disorder exacerbate Auger-Meitner recombination in AlGaN ultraviolet light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 125, 21109 (2024).

Synopsys & Inc. Sentaurus™ Device User Guide. http://www.synopsys.com/Company/Pages/Trademarks.aspx (2015).

Piva, F. et al. Modeling the degradation mechanisms of AlGaN-based UV-C leds: from injection efficiency to mid-gap state generation. Photonics Res. 8 (11), 1786–1791 (2020).

Buffolo, M. et al. Defects and reliability of GaN-Based leds: review and perspectives. Phys. Status Solidi. 219, 2100727 (2022).

Knauer, A. et al. Current-induced degradation and lifetime prediction of 310 Nm ultraviolet light-emitting diodes. Photonics Res. 7 (7), B36–B40 (2019).

Glaab, J. et al. Degradation of (In)AlGaN-Based UVB leds and migration of hydrogen. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 31, 529–532 (2019).

Glaab, J. et al. Impact of operation parameters on the degradation of 233 Nm AlGaN-based far-UVC leds. J. Appl. Phys. 131, 014501 (2022).

De Santi, C. et al. Modeling the degradation mechanisms of AlGaN-based UV-C leds: from injection efficiency to mid-gap state generation. Photonics Res. 8 (11), 1786–1791 (2020).

Orita, K. et al. Analysis of diffusion-related gradual degradation of InGaN-based laser diodes. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 48, 1169–1176 (2012).

De Santi, C., Meneghini, M., Meneghesso, G. & Zanoni, E. Degradation of InGaN laser diodes caused by temperature- and current-driven diffusion processes. Microelectron. Reliab. 64, 623–626 (2016).

Acknowledgements

Project funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component C2, Investment 1.1, by the European Union – NextGenerationEU. PRIN Project 20225YYLEP, “Empowering UV Led technologies for high-efficiency disinfection: from semiconductor-level research to SARs-Cov-2 inactivation. The authors would like to thank Sylvia Hagedorn and Markus Weyers (Ferdinand-Braun-Institut (FBH), Berlin, Germany) for providing ELO AlN/sapphire templates for the LED growth. This work was partially supported by the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the “Advanced UV for Life” consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nicola Roccato, Francesco Piva, Matteo Buffolo, Carlo De Santi, Nicola Trivellin, and Matteo Meneghini wrote the main manuscript text, prepared figures and equally carried out the experimental investigation and data analysis. Nicola Roccato performed also the numerical simulations. Norman Susilo, Daniel Hauer Vidal, Anton Muhin, Luca Sulmoni, Tim Wernicke and Michael Kneissl provided the samples and supported the experimental investigation. Gaudenzio Meneghesso, Enrico Zanoni and Matteo Meneghini provided also the resources for the experimental investigation and simulations. All the authors reviewed the paper and supported the methodology approach.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roccato, N., Piva, F., Buffolo, M. et al. Diffusion mechanism as cause of optical degradation in AlGaN-based UV-C leds investigated by TCAD simulations. Sci Rep 15, 39655 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23645-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23645-0