Abstract

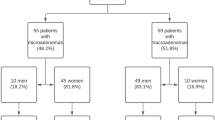

Prolactinomas/lactotroph pituitary neuroendocrine tumors are ten times less frequent in men than in women and their characteristics are less well known. The latest WHO classification includes them among pituitary tumors with a high risk of recurrence. This study aimed to identify clinical parameters suggesting aggressive prolactinomas. We conducted a retrospective study in three hospitals in Galicia, Spain, including 41 men with prolactinomas. The mean age at diagnosis was 46.5 ± 16.2 years. Baseline prolactin levels were a median of 800 ng/ml, with 95% being macroprolactinomas. Aggressive prolactinomas (n = 10) compared to non-aggressive (n = 31), had higher rates of visual disturbances (60% vs. 13%; p = 0.005) and deficiencies of thyroid-stimulating hormone (70% vs. 13%; p = 0.001) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (50% vs. 7%; p = 0.006) at diagnosis. Prolactin levels correlated with tumor maximum diameter, more stronger in aggressive cases (r = 0.68; p = 0.047). In our study, a 24% of the prolactinomas were classified as aggressive. We found that prolactinomas in males presented with significantly elevated prolactin levels that correlate strongly with tumor diameter, as well as, visual disturbances and deficiencies of thyroid-stimulating hormone and adrenocorticotropic hormone, should raise suspicion of aggressive lactotroph pituitary neuroendocrine tumors/prolactinomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lactotroph pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNETs), commonly referred to as prolactinomas are well-differentiated tumors derived from PIT1-lineage adenohypophyseal cells with lactotroph differentiation, according to the 2022 World Health Organization (WHO) classification1. They account for nearly 57% of all pituitary adenomas and show a pronounced sex-related imbalance, being ten times less common in men than in women. The biological and clinical behavior in male patients, however, remains less well understood2. While women of reproductive age typically present with microadenomas, approximately 80% of prolactinomas diagnosed in men are macroadenomas3. In men, these tumors are often large and invasive, frequently associated with mass effects, hypopituitarism, and lower response rates to dopamine agonists4,5.

Most prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs respond favorably to medical therapy, particularly dopamine agonists (DAs), which remain the first-line treatment and are generally effective and well tolerated6. However, a subset of patients exhibit resistance or refractoriness, and a minority evolve into clinically aggressive adenomas4. Rising prolactin levels in previously controlled patients may signal aggressiveness and, in rare cases, malignant transformation4. Beyond tumor growth, macroprolactinomas—and less frequently microprolactinomas—may compromise pituitary function, making comprehensive assessment of hormone deficiencies an essential part of patient management4.

The concept of tumor aggressiveness was already highlighted in the 2017 WHO classification, which noted that lactotroph tumors in men may constitute a subtype of aggressive pituitary adenomas regardless of histological grade7. According to the European Society of Endocrinology, aggressive pituitary tumors are defined as radiologically invasive lesions with unusually rapid growth or clinically significant progression despite optimal standard therapies, including dopamine agonists, surgery, and radiotherapy8. In practice, aggressiveness is suspected when tumors demonstrate invasive growth with persistent hormonal hypersecretion under adequate therapy, often requiring multimodal treatment and showing high recurrence risk6.

Aggressive pituitary adenomas overall comprise about 10% of pituitary tumors, and are clinically relevant because of their association with morbidity and mortality even in the absence of metastases4,9. The true prevalence of aggressive prolactinomas is uncertain due to heterogeneous definitions, scarcity of prospective studies, and publication bias, but they appear to represent a minority6. Risk factors for poor therapeutic response and aggressive behavior include male sex, younger age at diagnosis, radiological and histopathological invasiveness, and proliferative markers such as Ki-67 ≥ 3%, mitotic index > 2/10 high-power fields, and p53 immunopositivity10,11, as well as the loss of expression of p27, ATRX and p53 alterations12,13. In men, prolactinomas tend to follow a more aggressive course, with higher recurrence after surgery and progression despite medical or radiotherapy treatment14,15.

At the molecular level, resistance to DAs may be linked to reduced D2 receptor expression or downstream signaling alterations16, with additional biological factors also implicated17. Pathological evaluation therefore remains crucial to characterizing aggressiveness6.

Taken together, these observations underscore the clinical importance of identifying early predictors of aggressiveness in prolactinomas. The present multicenter study seeks to characterize clinical features that may facilitate the early recognition of aggressive prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs. To our knowledge, studies specifically comparing aggressive versus non-aggressive lactotroph tumors are scarce, and this work aims to provide novel insights into potential predictors of aggressiveness in male patients.

Materials and methods

Study design

This observational, cross-sectional, multicenter, retrospective study was conducted in three tertiary university medical centers in Galicia, Spain. Forty-one male patients with a diagnosis of prolactinoma/lactotroph PitNET were included. Medical records of all patients diagnosed over the past thirty years (up to 2024) were reviewed. The study protocol was approved by the Autonomous Research Ethics Committee of Santiago-Lugo (number 2024/373).

Diagnostic criteria

The diagnosis of prolactinoma/lactotroph PitNET was established by the presence of hyperprolactinemia markedly above the upper normal limit (> 100 ng/mL) together with radiological evidence of pituitary adenoma on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI with gadolinium contrast was the standard imaging modality; computed tomography (CT) was only used when MRI was contraindicated or unavailable. Other causes of hyperprolactinemia, such as stalk compression, were excluded. Mixed secretory tumors were not included. Tumors were classified as microadenomas (< 1 cm) or macroadenomas (≥ 1 cm)2.

Data collection

The following data were extracted: demographic information, presenting symptoms, biochemical profile, imaging findings, and histopathological characteristics when available. Tumor volume was estimated using the modified ellipsoidal formula (calculated as the anteroposterior diameter multiplied by the craniocaudal diameter multiplied by the transverse diameter, divided by 2) at the time of diagnosis18. Pituitary hormone deficiencies, previous treatments (medical, surgical, and radiotherapy) and related outcomes were documented. Clinical manifestations related to mass effect or hyperprolactinemia were also recorded.

Baseline evaluation included thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), testosterone, cortisol, and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). Hormone levels were measured in local hospital laboratories using validated methods (radioimmunoassay, immunoradiometry, or enzyme immunoassay), with reference ranges specific to each assay. Assessments were performed at diagnosis, during follow-up, and at the last clinic visit.

Treatment evaluation

Medical treatment with DAs was analyzed in terms of drug type, cumulative dose, duration, tolerability, and resistance. Surgical management was assessed regarding the approach, number of procedures, and complications. Radiotherapy characteristics, including modality and adverse effects, were also recorded.

Resistance to DAs was characterized by less than 50% reduction in tumor size despite receiving maximum conventional doses of DAs19.

The hormonal response was classified as complete if prolactin levels normalized, partial if there was a greater than 50% reduction in prolactin levels without normalization, or absent if no significant change was observed.

Radiological response was considered complete if MRI revealed no detectable tumor tissue after treatment. Partial response was defined as a reduction in tumor volume of more than 30%. Stability was characterized by no change in tumor volume, a decrease of less than 30% or an increase of less than 20%. Progression was defined as tumor growth greater than 20% or the appearance of new metastases20.

Clinical cure was defined as the achievement and sustained maintenance of normoprolactinemia for more than one year without the need for treatment, accompanied by the absence of radiological evidence indicating the presence of a pituitary tumor.

Histopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis

The surgical specimens were fixed in neutral, phosphate-buffered, 10% formalin and included in paraffin blocks. Formalin-fixed paraffin-encubedded (FFPE) tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Immunohistochemical stains were also performed on 4 μm thick paraffin sections using a peroxidase – conjugated – labeled dextran polymer (Dako EnVision peroxidase/DAB; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), with 3,3`-diaminobenzidine as the chromogen, and using a series of primary antibodies as follows: PIT-1 (clone, D7; dilution 1:200, antigen retrieval, pH 9; manufacturer, Gennova, Sevilla, Spain), PRL (PRL2644, 1:300, Ph 9, Termo-Fisher, Massachusetts, US), GH (GH-2, 1:500, pH 9, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), GATA3 (L50-823, 1:50, Ph 6, BioSystems, Barcelona, Spain), Cytokeratin’s 8/18 (CK8/18) (EP17/EP30, ready to use, pH 9, Dako), estrogen receptor (EP1/IR044IVD; ready-to-use, pH 9, Dako), p27 (SX5368, 1:50, pH 9 Dako), ATRX (AX1, 1:100, Ph 9, Dianova, Hamburg, Germany), p53 (D07, ready-to-use, pH 9, Dako) and Ki67 (MIB1, 1:200; pH 9, Dako). Analysis of somatic mutations through next generations sequencing (NGS) from paraffin-embedded tissue from one of the cases (metastatic PitNET).

The samples were classified according to the criteria of the 5th edition of the WHO classification of the endocrine and neuroendocrine tumors1.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was first performed to characterize the study population. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies, while continuous variables were summarized using measures of central tendency and dispersion. Normally distributed continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and non-normally distributed variables as median and interquartile range (IQR).

Group comparisons for categorical variables were conducted using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. For continuous variables, normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test and homogeneity of variance with Levene’s test. Between-group comparisons were performed using the Student’s t-test for normally distributed data or the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. Associations between quantitative variables were explored using Pearson’s correlation coefficient for parametric data and Spearman’s rank correlation for non-parametric data. Coefficients of determination (r²) were also calculated. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated for categorical associations.

Regression analyses were used to adjust for potential confounding factors. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed with age at diagnosis as a covariate, and multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for age were applied to assess associations between clinical outcomes and exposure variables. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical, endocrine and radiological characteristics

Clinical, endocrine, and radiological characteristics of male patients with prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs are summarized in Table 1. The mean age at diagnosis was 46.5 ± 16.2 years. Hypogonadism was the most frequent clinical manifestation (53.7%), followed by headache (31.7%). Median baseline prolactin levels reached 800 ng/mL. Gonadotropin deficiency was present in 61% of patients. Most cases (95%) corresponded to macroprolactinomas, with a median maximum tumor diameter of 15.7 mm [IQR 21 mm]. Suprasellar extension was observed in 73%, sphenoidal extension in 73.2%, cavernous sinus invasion in 63.4%, and bone invasion in 12.2%.

Primary treatment and surgical indications

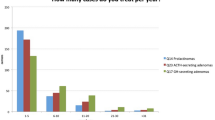

Treatment modalities and outcomes regarding tumor response and biochemical control are shown in Table 2. All patients initially received medical therapy, with a mean cabergoline weekly dose of 2.5 ± 2.0 mg. Overall, 26% required surgery due to resistance to medical treatment and/or extrasellar extension of the tumor; of these, 40% underwent a transsphenoidal approach and 20% a transcranial one, and 60% subsequently received radiotherapy. Surgical indications included resistance to medical treatment (12%), extrasellar extension (12%), visual disturbances (5%), tumor apoplexy (2%), and intolerance to pharmacological therapy (3%).

Aggressive vs. non-aggressive tumors

In this series, aggressive prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs (n = 10), compared with non-aggressive tumors (n = 31), were more frequently associated with visual disturbances (60% vs. 13%; OR 13, 95% CI 2.2–74.1; p = 0.005), TSH deficiency (70% vs. 13%; OR 15, 95% CI 2.8–87.0; p = 0.001), and ACTH deficiency (50% vs. 7%; OR 14.5, 95% CI 2.1–96.0; p = 0.006). These associations remained statistically significant after adjustment for age at diagnosis (Fig. 1).

Aggressive tumors had a larger maximum diameter (36 mm vs. 14 mm; p = 0.001), with higher rates of extrasellar extension (100% vs. 38.7%; p = 0.009), sphenoidal extension (90% vs. 38.7%; p = 0.007), cavernous sinus invasion (100% vs. 51.6%; p = 0.007), and bone invasion (40% vs. 3.2%; p < 0.001). All these associations remained statistically significant after age adjustment. A positive correlation was also observed between baseline serum prolactin levels and maximum tumor diameter, which was stronger in aggressive adenomas (r = 0.679; p = 0.047) (Fig. 2).

With regard to treatment, aggressive tumors showed greater resistance to medical therapy (70% vs. 22%; p = 0.003), required higher weekly cabergoline doses (2.9 mg vs. 2.1 mg; p = 0.005), and more frequently underwent surgery (80% vs. 16%; p = 0.005). These differences also remained significant after age adjustment. Transcranial approaches were exclusively performed in aggressive tumors (20% vs. 0%; p = 0.012). Surgical indications in aggressive tumors included medical resistance (30% vs. 6.4%; p = 0.003), visual disturbances (20% vs. 0%), and tumor apoplexy (10% vs. 0%). Reinterventions (30% vs. 0%; p = 0.002) and postoperative radiotherapy (40% vs. 6.5%; p = 0.004) were also significantly more frequent in aggressive tumors, persisting after adjustment for age.

Long-term outcomes

One patient developed metastasis (metastatic PitNET/pituitary carcinoma) during follow-up. At the end of follow-up, 70% achieved normalized prolactin levels, with a median of 6.8 ng/mL (p = 0.040). Normalization of prolactin remained significant after adjustment for age. Additionally, 36% achieved tumor stability, 25% fulfilled criteria for aggressive progression, and 5% were in remission without treatment. No deaths were attributed to pituitary adenomas.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical findings

Histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses were available for four representative cases (Table 3). Regarding tumor subtype, three were classified as sparsely granulated adenomas and one as densely granulated. All tumors expressed p27 and displayed a wild type p53 staining pattern. Only one lost immunostaining for ATRX. PIT-1 expression was detected in three out of four cases. PRL in two and GATA3 in only one case. Keratin (CK8/18) immunoreactivity showed a peripheral cytoplasmic pattern in three tumors, while the metastatic PitNET was negative. The expression of estrogen receptors was decreased in all cases. The Ki-67 labeling index was high (22%) only in the metastatic PitNET. A somatic CDKN2A p. (Arg80) pathogenic variant (variant allele frequency: 96.6) was found in one case (see Figs. 3 and 4).

Microscopic features of case 1. (A and B) Lactotroph PitNET/adenoma with mostly chromophobic tumor cells, in this case arranged in sheets (hematoxilin and eosin stain). (C) Weak granular cytoplasmic immunoreactivity pattern for prolactin. (D) Diffuse nuclear immunoreactivity for PIT1. (E) Extensive cytoplasmic immunoreactivity pattern for keratins 8/18. (F) Nuclear reactivity for estrogen receptor alpha. (G) Ki67 proliferation index low (< 0.5%) (H) Conserved immunohistochemical expression for p27. Original magnification: A, 200X; B, 400X; C, 200X, inset, 400X; D-H, 200X.

Microscopic features of case 4. (A and B) Metastatic PitNET with nuclear pleomorphism, mitoses (hematoxilin and eosin). (C) Diffuse nuclear immunoreactivity for PIT1. (D) Cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for GH. (E) Cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for PRL. (F) Nuclear reactivity for estrogen receptor alpha. (G) The Ki67 labeling index is high (22%) (H) Strong immunohistochemical expression of p27. Original magnification: A, 200X; B, 400X; C-H, 200X.

Discussion

In our study of 41 prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs, the rate of aggressiveness was as high at 25%. In a case series of 36 males with prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs by Delgrande et al. invasiveness and aggressiveness were observed in 41% and 30% of cases, respectively21. It is important to note that the criteria used to classify aggressive adenomas have been modified in recent years8.

The mean age at diagnosis in our serie was 46.5 years, with variations reported in different studies ranging from 37 to 47 years9,22,23,24,25,26.

At the time of presentation, mean prolactin levels were 800 ng/ml, showing a wide variability compared to different studies, which have reported mean ranges of 99–14,393 ng/ml23,24,26,27,28. A positive correlation between prolactin levels and tumor size has been observed, which is also significantly demonstrated in this case series23. Prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs, in males are considered to be intrinsically more aggressive regardless of tumor size26.

Hypogonadism was highlighted as the most frequent clinical presentation (54%), followed by headache. These data area consistent with previous studies22,23,24,29. Patients with macroprolactinomas have a higher incidence of headache and visual abnormalities compared to patients with microadenomas26,27.

In addition to FSH/LH deficiency, TSH and ACTH deficiencies were among the most commonly observed findings, consistent with previous studies25. Other case series reported gonadal axis involvement in all male patients3,26. Overall, hypopituitarism was present in approximately three-quarters of the patients.

Aggressive prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs, compared to non-aggressive, presented with a higher frequency of visual disturbances, TSH and ACTH deficiency, which may be explained by higher rates of tumor volume, extrasellar and sphenoidal extension, invasion of the cavernous sinuses, and bone24,30,31. Additionally, the thyrotrophic and corticotrophic axes were more frequently affected in patients with macroprolactinomas, compared to microprolactinomas, as has been described previously28,32.

Most patients received primary medical treatment with DAs, while about a quarter of the patients required surgery, data consistent with the findings of other studies9,25,26. The most common indications for surgery, also in line with our series, were resistance and/or intolerance to DAs and/or extrasellar extension of the tumor22,24. In addition, patients who required surgical reintervention also received radiotherapy, a practice observed in other studies9.

Partial biochemical control was achieved at comparable rates in both non-aggressive and aggressive prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs. However, tumor control was more frequent in the aggressive group, likely reflecting the higher use of multimodal treatment strategies, including repeat surgery and postoperative radiotherapy. No mortality directly attributable to prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs was observed. One patient progressed to pituitary carcinoma, but death resulted from respiratory sepsis rather than tumor-related complications.

Pathological examination was limited by the small number of samples, and no differences were observed between prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs and aggressive cases. Although loss of p27 and p53 has often been associated with aggressive behavior12,34,35, all tumors in our series retained positivity for these markers, and ATRX loss was not detected in aggressive or metastatic PitNETs. The only metastatic case combined a markedly elevated Ki-67 index (22%) with a CDKN2A mutation, in line with previous studies that associate high Ki-67 values with aggressive biological behavior21,33. CDKN2A is a tumor suppressor gene in which high levels of mutations and LOH have been reported in prolactinomas and non-functional PitNETs34, and alterations in this gene have been linked to aggressive clinical behavior34,35; our findings seem to reinforce this relationship. Consistent with other studies, aggressive-invasive prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs were associated with unfavorable surgical outcomes, higher recurrence or progression rates during long-term follow-up, and elevated proliferative markers, including mitotic count > 10, Ki-67 > 5%, and frequent p53 positivity36.

This study has several inherent limitations related to its retrospective design. Reliance on medical records may have introduced biases in data collection, and the inability to control variables prospectively limits causal inference. Given the exploratory nature of the study and the limited number of eligible cases, no formal sample size calculation or power analysis was performed; instead, all available patients meeting inclusion criteria were included to maximize statistical power. Nevertheless, the relatively small sample size—particularly in the aggressive prolactinoma group—likely contributed to wide confidence intervals for variables such as visual disturbances and TSH/ACTH deficiencies, reflecting uncertainty in these estimates. Although age at diagnosis was adjusted for in multivariable analyses, residual confounding cannot be excluded, as other potentially important factors could not be systematically controlled due to incomplete historical data. In addition, the limited availability of pathological anatomy data further restricted the depth of analysis.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes valuable information to the relatively limited evidence on clinical predictors of aggressiveness in prolactinomas, with a particular focus on male patients. The direct comparison between aggressive and non-aggressive lactotroph PitNETs/prolactinomas within this subgroup, together with the relatively long follow-up period, provides meaningful insights into clinical outcomes and enriches the growing body of knowledge in this area.

Conclusions

In our cohort, a quarter of prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs were classified as aggressive. Markedly elevated prolactin levels—closely correlated with tumor diameter—as well as visual disturbances and TSH/ACTH deficiencies should raise clinical suspicion of aggressive disease. Future studies should prioritize prospective designs and ideally involve multicenter collaborations to increase sample size, and ensure more standardized data collection. These approaches will be essential to validate our findings and to refine clinical predictors of aggressiveness in prolactinomas/lactotroph PitNETs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Perry, A., Grossman, A., Lopes, M. B. S., Nishioka, H. & Uccella, S. Lactotroph PitNET/adenoma. In Endocrine and Neuroendocrine Tumours (5th ed., WHO Classification of Tumours series, vol. 10) Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (2022). Available at: https://publications.iarc.fr

Klibanski, A. Clinical practice. Prolactinomas. N Engl. J. Med. 362, 1219–1226 (2010).

Shimon, I. et al. Giant prolactinomas larger than 60 mm in size: a cohort of massive and aggressive prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas. Pituitary 19, 429–436 (2016).

Petersenn, S. et al. Diagnosis and management of prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas: a pituitary society international consensus statement. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 19, 722–740 (2023).

Wierinckx, A. et al. Sex-related differences in lactotroph tumor aggressiveness are associated with a specific gene-expression signature and genome instability. Front. Endocrinol. 9, 706 (2018).

Olarescu, N. C. et al. Aggressive and malignant prolactinomas. Neuroendocrinology 109, 57–69 (2019).

Lopes, M. B. S. The 2017 world health organization classification of tumours of the pituitary gland: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 134, 521–535 (2017).

Raverot, G. et al. European society of endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the management of aggressive pituitary tumours and carcinomas. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 178, G1–G24 (2018).

Lamas, C. et al. Efficacy and safety of Temozolomide in the treatment of aggressive pituitary neuroendocrine tumours in Spain. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1204206 (2023).

Raverot, G. et al. Aggressive pituitary tumours and pituitary carcinomas. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 17, 671–684 (2021).

Fainstein Day, P. et al. Gender differences in macroprolactinomas: study of clinical features, outcome of patients and Ki-67 expression in tumor tissue. Front. Horm. Res. 38, 50–58 (2010).

Asa, S. L., Mete, O., Perry, A. & Osamura, R. Y. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of pituitary tumors. Endocr. Pathol. 33, 6–26 (2022).

Mete, O. & Asa, S. L. Clinicopathological correlations in pituitary adenomas. Brain Pathol. 22, 443–453 (2012).

Delgrange, E., Daems, T., Verhelst, J., Abs, R. & Maiter, D. Characterization of resistance to the prolactin-lowering effects of Cabergoline in macroprolactinomas: a study in 122 patients. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 160, 747–752 (2009).

Raverot, G. et al. Prognostic factors in prolactin pituitary tumors: clinical, histological, and molecular data from a series of 94 patients with a long postoperative follow-up. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 1708–1716 (2010).

Molitch, M. E. Management of medically refractory prolactinoma. J. Neurooncol. 117, 421–428 (2014).

Trouillas, J. et al. Clinical, pathological, and molecular factors of aggressiveness in lactotroph tumours. Neuroendocrinology 109, 70–76 (2019).

Di Chiro, G. & Nelson, K. B. The volume of the Sella turcica. Am. J. Roentgenol. Radium Ther. Nucl. Med. 87, 989–1008 (1962).

Melmed, S. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hyperprolactinemia: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 273–288 (2011).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer. 45, 228–247 (2009).

Delgrange, E., Sassolas, G., Perrin, G., Jan, M. & Trouillas, J. Clinical and histological correlations in prolactinomas, with special reference to Bromocriptine resistance. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 147, 751–757 (2005).

Schaller, B. Gender-related differences in prolactinomas: a clinicopathological study. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 26, 152–159 (2005).

Leca, B. M. et al. Identification of an optimal prolactin threshold to determine prolactinoma size using receiver operating characteristic analysis. Sci. Rep. 11, 9801 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. Clinical outcomes in male patients with lactotroph adenomas who required pituitary surgery: a retrospective single center study. Pituitary 21, 454–462 (2018).

Iglesias, P. et al. Prolactinomas in men: a multicentre and retrospective analysis of treatment outcome. Clin. Endocrinol. 77, 281–287 (2012).

Shimon, I., Benbassat, C. & Hadani, M. Effectiveness of long-term Cabergoline treatment for giant prolactinoma: study of 12 men. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 156, 225–231 (2007).

Pinzone, J. J. et al. Primary medical therapy of micro- and macroprolactinomas in men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85, 3053–3057 (2000).

Sibal, L. et al. Medical therapy of macroprolactinomas in males: I. Prevalence of hypopituitarism at diagnosis. II. Proportion of cases exhibiting recovery of pituitary function. Pituitary 5, 243–246 (2002).

Colao, A. et al. Gender differences in the prevalence, clinical features and response to Cabergoline in hyperprolactinemia. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 148, 325–331 (2003).

Shrivastava, R. K., Arginteanu, M. S., King, W. A. & Post, K. D. Giant prolactinomas: clinical management and long-term follow up. J. Neurosurg. 97, 299–306 (2002).

Delgrange, E., Trouillas, J., Maiter, D., Donckier, J. & Tourniaire, J. Sex-related difference in the growth of prolactinomas: a clinical and proliferation marker study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 82, 2102–2107 (1997).

Iglesias, P. et al. Giant prolactinoma in men: clinical features and therapeutic outcomes. Horm. Metab. Res. 50, 791–796 (2018).

Calle-Rodrigue, R. D. et al. Prolactinomas in male and female patients: a comparative clinicopathologic study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 73, 1046–1052 (1998).

Pease, M., Ling, C., Mack, W. J., Wang, K. & Zada, G. Role of epigenetic modification in tumorigenesis and progression of pituitary adenomas: a systematic review. PLoS One. 8, e82619 (2013).

Terry, M. et al. High-grade progression, sarcomatous transformation, and metastasis of pituitary neuroendocrine neoplasms: the UCSF experience. Endocr. Pathol. 35, 338–348 (2024).

Raverot, G. et al. Prognostic factors in prolactin pituitary tumors: clinical, histological, and molecular data from 94 patients with long postoperative follow-up. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 1708–1716 (2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: ED-L, RV-T; data curation: ED-L, EF-R, LC-B, KV-O, JMC-T; formal analysis: ED-L; funding acquisition: JMC-T was supported by grant no. ISCIII-PI23/00722, from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, State Research Agency (Spain), co-funded by the European Union (EU).; investigation: all authors; methodology: ED-L, RV-T; writing – original draft: ED-L; writing – review & editing: all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics declarations

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Autonomous Research Ethics Committee of de Santiago-Lugo under number 2024/373. Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Díaz-López, E.J., Villar-Taibo, R., Fernández-Rodríguez, E. et al. Aggressive prolactinomas in men are associated with visual disturbances and pituitary hormone deficiencies. Sci Rep 15, 39497 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23646-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23646-z