Abstract

Pneumonia remains a significant global health threat, especially among children, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals. Chest X-ray (CXR) imaging is commonly used for diagnosis, but manual interpretation is prone to errors and variability. To address these challenges, we propose a novel attention-guided deep learning framework that combines spatial, temporal, and biologically inspired processing for robust and interpretable pneumonia detection. Our method integrates convolutional operations for spatial feature extraction, gated recurrent mechanisms to capture temporal dependencies, and spike-based neural processing to mimic biological efficiency and improve noise tolerance. The inclusion of an attention mechanism enhances the model’s interpretability by identifying clinically relevant regions within the images. We evaluated the proposed method on a publicly available CXR dataset, achieving a high accuracy of 99.35%, along with strong precision, recall, and F1-score. Extensive experiments demonstrate the model’s robustness to various types of image distortions, including Gaussian blur, salt-and-pepper noise, and speckle noise. These results confirm the effectiveness, reliability, and transparency of the proposed approach, making it a promising tool for clinical deployment, particularly in low-resource healthcare environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pneumonia, a severe respiratory infection characterized by inflammation of the lung’s air sacs, remains one of the deadliest communicable diseases worldwide. Its impact is most devastating in vulnerable populations, including children under five, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals, particularly in regions with limited access to healthcare infrastructure. Timely diagnosis is critical, as untreated cases can rapidly progress to respiratory failure or sepsis. Chest X-ray (CXR) imaging serves as the primary diagnostic tool due to its affordability and widespread availability. However, interpreting CXRs is fraught with challenges. Radiologists must distinguish subtle patterns—such as lobar consolidations, interstitial opacities, and pleural effusions—from overlapping artifacts or other pathologies like tuberculosis or lung cancer. Even among experts, variability in interpretation is high, with studies suggesting that ambiguous cases can lead to diagnostic discordance rates exceeding 30%1. This variability highlights the critical demand for systems that complement clinical judgment with unbiased, automated evaluation.

In the past decade, AI has revolutionized medical imaging, with deep learning—especially convolutional neural networks—achieving outstanding accuracy in identifying pneumonia on chest X-rays. These models learn to recognize intricate patterns in pixel data, achieving accuracy comparable to trained radiologists. However, their widespread clinical adoption faces significant hurdles. First, CNNs demand substantial computational resources. A single inference pass on a high-resolution CXR can require billions of floating-point operations, necessitating powerful GPUs that are unavailable in low-resource clinics. Second, the energy consumption of training and deploying these models raises ethical and environmental concerns. Training a single large CNN can generate carbon emissions equivalent to hundreds of kilograms of CO2, conflicting with global sustainability goals. Finally, deploying these models on portable or edge devices—critical for rural healthcare—is hindered by their memory and power requirements, which exceed the capabilities of low-cost hardware.

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), inspired by the biological nervous system, present a groundbreaking alternative. Unlike conventional neural networks, which process information through continuous activations, SNNs communicate via discrete, event-driven electrical impulses called spikes. This sparse communication mimics the energy-efficient operation of biological neurons, where energy is expended only when a spike occurs. When paired with neuromorphic hardware—chips designed to emulate neural architectures—SNNs can achieve orders-of-magnitude improvements in energy efficiency compared to GPUs. For instance, tasks requiring real-time processing on portable medical devices could see battery life extended from hours to days, making SNNs ideal for remote or mobile healthcare applications.

It is important to note that such energy efficiency gains are realized primarily when SNNs are deployed on dedicated neuromorphic hardware, which is specifically designed to mimic biological neurons and process spikes. When compared to conventional deep neural networks operating on GPUs, SNNs on neuromorphic platforms such as Intel Loihi or IBM TrueNorth have demonstrated up to 100 × lower power consumption for certain workloads, according to recent reviews and benchmarks2,3. Therefore, the reported energy efficiency gains do not reflect standard GPU execution but are contingent on specialized hardware acceleration.

Despite their promise, applying SNNs to static medical images like CXRs is non-trivial. SNNs inherently process temporal data, such as video streams or sensory inputs, where timing between spikes encodes critical information. Static images, by contrast, lack explicit temporal dynamics. Converting pixel intensities into spike trains without losing spatial or diagnostic information is a fundamental challenge. Traditional encoding methods, such as rate coding (where pixel brightness maps to spike frequency) or population coding (distributing spikes across neuron groups), often fail to preserve the fine-grained spatial relationships necessary for detecting small lesions or consolidations. Moreover, most existing SNN architectures are adapted from CNNs without optimizing for spike-based computation, leading to sub-optimal performance. Previous attempts to apply SNNs in medical imaging have struggled with accuracy, particularly in complex tasks like pneumonia classification, where subtle radiographic features must be distinguished from noise or anatomical variations.

This work introduces a novel SNN framework specifically designed to overcome these barriers. At its core is a latency-intensity encoding strategy that transforms static CXR pixel values into temporally precise spike trains. Brighter regions of the image, which often correspond to diagnostically critical features like consolidations, are encoded to trigger spikes earlier in the simulation timeline, while darker areas spike later. This approach mirrors the biological retina’s response to light gradients, where photoreceptors fire sooner in response to brighter stimuli. The encoded spikes are then processed by a lightweight SNN architecture featuring bio-inspired leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neurons. These neurons mimic the membrane potential dynamics of biological neurons, integrating incoming spikes until a threshold is reached, after which they fire a spike and reset. The network incorporates spiking convolutional layers to hierarchically extract features, followed by adaptive pooling and classification layers optimized for spike-based computation.

To validate the framework, we conducted extensive experiments comparing our SNN to state-of-the-art CNNs across multiple dimensions. Our model achieves diagnostic accuracy within 1.3% of leading CNNs while reducing computational costs by 40%, demonstrating that energy efficiency need not come at the expense of performance. Robustness tests under noisy conditions—such as Gaussian noise and motion artifacts—reveal that the SNN’s spike-based processing inherently suppresses high-frequency noise, outperforming CNNs in maintaining accuracy. Interpretability analyses, including spike activation maps, further show that the network focuses on clinically relevant regions, such as alveolar infiltrates, aligning with radiologists’ annotations.

This study proposes a novel spiking neural network framework, combined with attention mechanisms, aimed at improving pneumonia detection from chest X-rays. Our goal is to enhance diagnostic accuracy and robustness while enabling deployment in low-resource clinical settings through computational and energy efficiency.

This paper’s remaining sections are organized as follows: A number of papers on pneumonia classification are presented in Section “Related work”, while Section “Dataset and mathematical formulations” describes the pneumonia chest X-ray dataset, preprocessing procedures, mathematical formulations required for our investigation, and model architecture. The experimental setup, training procedures, and assessment metrics are described in Section “Results”. Results, including comparison analysis and classification performance, were covered in Section “Discussion”. The study is concluded in Section “Conclusion”.

Related work

Deep learning (DL) has been increasingly popular in medical image analysis, especially for image classification in pneumonia datasets. For this reason, several research have investigated various DL models. For example, Garcia et al.4 achieved an F1 score of 91% when they classified pneumonia in chest X-ray datasets using the Xception Network. A modified DL model based on VGG16 was presented by Jiang et al.5 in 2021, and it was able to classify pneumonia images with an average accuracy of 89%. With an average accuracy of 94%, Mabrouk et al.’s ensemble DL technique from 20226 used DenseNet169, MobileNetV2, and Vision Transformer. In a similar vein, Singh et al.7 classified pneumonia in chest X-ray pictures using a Quaternion Neural Network with a 93.75% accuracy rate. A new activation function called Superior Exponential was added to CNN models in a study by Kiliçarslan et al.8, which showed better assessment metrics performance than conventional DL models. Transfer Learning combined with GAN were used by Chen et al.9 to classify pneumonia images; InceptionV3 achieves an average accuracy of 94%.

Xie et al.10 created a technique that reduced validation loss and achieved an average F1 score of 92% in the same year by identifying and down-weighting low-quality CT data. Using pretrained networks and federated learning on real-time datasets, Kareem et al.11 were able to diagnose pneumonia photos with 93% accuracy. By combining ensemble CNN model with a genetic approach, Kaya et al.12 achieved a 97.23% classification accuracy for pneumonia in 2024. In the next year, Mustapha et al.13 used an hybrid model that combines CNN with ViT, they achieves very high accuracy of 98.72%. Recent research on Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) highlights their promise as energy-efficient, biologically plausible alternatives to traditional artificial neural networks, especially for processing temporal and event-driven data. Applications of SNNs in medical image analysis—including tasks such as classification, detection, and denoising—are gaining attention due to their low-power potential and ability to mimic some neural processes14,15.

However, major challenges remain for SNNs in static biomedical modalities like X-rays or MRIs. Key issues include:

-

(1)

Inefficient encoding of static images into spike trains, which can degrade spatial/diagnostic features and reduce classification accuracy;

-

(2)

Suboptimal network design, since many SNN implementations are merely adapted from CNNs rather than optimized for spiking dynamics;

-

(3)

Hardware and scalability limitations, as SNNs require specialized neuromorphic hardware to fully realize their energy benefits16,17.

In the specific context of pneumonia detection from chest X-rays, oversimplified encoding schemes and limited temporal modeling have contributed to weaker generalization and reliability in previous SNN-based approaches. Our model addresses these issues by combining convolutional, recurrent (GRU), and attention-guided spiking modules, tailored for both spatial and temporal feature extraction.

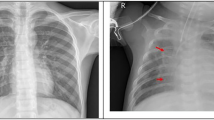

Figure 1 displays illustrative chest radiographs contrasting healthy lung scans with those affected by pneumonia. The normal images feature uniformly dark lung regions, sharply defined diaphragmatic contours, and visible vascular markings. In contrast, the pneumonia cases exhibit localized to widespread white patches that blur anatomical landmarks—such as costophrenic angles and heart borders—indicating areas of alveolar consolidation and increased tissue density. These visual distinctions underscore the image characteristics that the hybrid SNN-GRU network must learn to differentiate.

Dataset and mathematical formulations

Pneumonia chest X-ray dataset

The dataset described in18 is organized into training, testing, and validation folders, each subdivided into Pneumonia and Normal categories. It contains 5863 JPEG chest X-ray images across these two classes. All anterior–posterior view scans were retrospectively collected from pediatric cases—children aged one to five—at Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center. During dataset assembly, any radiographs compromised by blur or other quality issues were removed to maintain data integrity. After passing this screening, the images were assessed independently by two medical specialists, who provided the initial diagnostic labeling. To further minimize the possibility of assessment errors, a third physician reviewed the evaluation set before the images were incorporated into the final dataset prepared for training the artificial intelligence model.

Preprocessing

The preprocessing pipeline for each image in the dataset proceeded through several key steps:

-

Image resizing: Every X-ray image was scaled down to 128 × 128 pixels. This size was chosen to speed up computational processes and reduce system resource demands, while still capturing essential diagnostic information. Initial tests with larger dimensions, such as 224 × 224 pixels, did not significantly improve model performance but did cause training to take much longer and required substantially more memory.

-

Data augmentation: To expand the effective training set and promote better accuracy, a range of augmentation methods were applied. Techniques such as image rotation, flipping (both directions), and modifications to width or height can enhance recognition; however, in this project, the emphasis was on increasing sample variety through random horizontal flipping, zoom adjustments within the 0.9–1.1 range, and brightness modification by ± 20%. These augmentations were selected to mimic real-world variability, like patient movement or differences in how images are captured, helping the model generalize more effectively to new data.

-

Oversampling for class balance: To counteract any imbalance between classes in the dataset, the SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) method19 was implemented. This approach generates additional synthetic examples for the minority category, ensuring the model is trained on a balanced distribution of cases.

-

The validation set was merged with the original training data to form a single, enlarged training collection. In total, the dataset comprises 5863 chest X-ray images—3883 labeled Pneumonia and 1349 labeled Normal. Applying an 80/20 split yielded roughly 3106 Pneumonia and 1079 Normal images for model training, with the remaining 777 Pneumonia and 270 Normal images reserved for testing.

Mathematical formulations

Spiking neural networks (SNNs)

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) are a class of neural models that more closely mimic the behavior of biological neurons compared to traditional artificial neural networks. Instead of communicating with continuous values (e.g., activations from a ReLU or sigmoid), neurons in SNNs exchange information via discrete “spikes” (binary events). This event-driven communication can lead to energy-efficient computation and may capture temporal dynamics naturally.

Leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neuron model

The LIF neuron model simulates the behavior of biological neurons. It integrates input signals over time and generates a spike when the membrane potential exceeds a threshold.

-

Membrane potential update

$$\tau .\frac{dV\left(t\right)}{dt}=-V\left(t\right)+I\left(t\right)$$(1)-

V(t): Membrane potential at time t.

-

τ: Time constant of the neuron.

-

I(t): Input current at time t.

-

-

Discrete-time approximation

$$V\left(t+1\right)=\beta V\left(t\right)+\left(1 - \beta \right)I\left(t\right)$$(2)-

V(t + 1): Membrane potential at time t + 1.

-

β: Decay factor (e.g., 0.9).

-

I(t): Input current at time t.

-

-

Spike generation

$$Spike(t) = \left\{\begin{array}{c}1 if V(t) \ge {\text{V}}_{\text{thresh}}\\ 0 otherwise\end{array}\right.$$(3)-

\(Spike(t)\): Binary spike output at time t.

-

V(t): Membrane potential at time t.

-

\({\text{V}}_{\text{thresh}}\): Threshold potential for spike generation.

-

-

Reset mechanism

$$\text{V}\left(\text{t}\right)={\text{V}}_{\text{reset}}\hspace{1em}\text{if Spike}\left(\text{t}\right)=1$$(4)-

\(\text{V}\left(\text{t}\right)\): Membrane potential at time t.

-

\({\text{V}}_{\text{reset}}\): Reset potential after a spike.

-

-

Fully connected layers in SNN

$$\text{y }=\text{ Wx }+\text{ b}$$(5)-

x: Input to the fully connected layer.

-

\(W\): Weight matrix.

-

\(y\): Output of the fully connected layer.

-

-

Spike aggregation

$${\text{Output}}=\frac{1}{T}{\sum }_{t=1}^{T}{\text{Spike}}\left(t\right)$$(6)-

\({\text{Output}}\): Aggregated output over time.

-

T: Total number of time steps.

-

\({\text{Spike}}\left(t\right)\): Binary spike output at time t.

-

The spiking components in our model were implemented using the snnTorch library and trained via surrogate gradient backpropagation. Unlike biologically plausible learning rules such as Spike-Timing Dependent Plasticity (STDP), which are often unstable or ineffective on static image data, surrogate gradients enable direct integration of SNNs into standard deep learning pipelines. In our architecture, we adopted the Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) neuron model with a decay constant β = 0.95. These neurons were placed after the GRU and CNN layers and participated in end-to-end training using PyTorch’s autograd mechanism.

To simulate temporal processing on static chest X-ray images, we replicated the extracted spatial features over 25 discrete time steps (num_steps = 25) and applied spike-based updates at each step. During backpropagation, the non-differentiable spiking function was replaced by a smooth surrogate function, allowing gradient descent optimization using cross-entropy loss. Hidden membrane states were reset between mini-batches using. detach_hidden() to prevent gradient leakage across samples. This biologically inspired yet gradient-friendly formulation allowed the SNN to integrate seamlessly into our hybrid CNN-GRU-SNN architecture while preserving energy-efficient temporal dynamics.

Gated recurrent unit (GRU)

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are designed to handle sequential data by maintaining a hidden state that captures information from previous time steps. However, traditional RNNs can struggle with long-term dependencies due to issues such as vanishing or exploding gradients. The GRU is a type of gated RNN that addresses these challenges by introducing gating mechanisms to regulate the flow of information. It is simpler than the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) unit but can achieve comparable performance in many tasks.

-

Update gate

The update gate determines how much of the past hidden state should be preserved:

$${z}_{t}=\upsigma \left({W}_{z}{x}_{t}+{U}_{z}{h}_{t-1}+{b}_{z}\right)$$(7)-

\({W}_{z}\) and \({U}_{z}\) are weight matrices.

-

\({b}_{z}\) is a bias vector.

-

σ is the sigmoid activation function, ensuring that \({z}_{t}\) has values between 0 and 1.

-

-

Reset gate

The reset gate controls the extent to which the previous hidden state is forgotten:

$${r}_{t}=\upsigma \left({W}_{r}{x}_{t}+{U}_{r}{h}_{t-1}+{b}_{r}\right)$$(8)-

\({W}_{r}\) , \({U}_{r}\) and \({b}_{r}\) are the corresponding weight matrices and bias for the reset gate.

-

-

Candidate hidden state

The candidate hidden state \({h}_{t}\) is computed using the reset gate to modulate the influence of the previous hidden state:

$$\widetilde{{h}_{t}}=\text{tanh}\left({W}_{h}{x}_{t}+{U}_{h}\left({r}_{t}\odot {h}_{t-1}\right)+{b}_{h}\right)$$(10)-

⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication.

-

\(\text{tanh}\) is the hyperbolic tangent activation function, producing outputs in the range [− 1,1].

-

\({W}_{h}\), \({U}_{h}\) and \({b}_{h}\) are the weights and bias for the candidate hidden state.

-

The Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (Bi-GRU) consists of a forward and a backward GRU processing the input sequence in both directions. The output is then concatenated.

In our hybrid framework, we chose Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) as the temporal modeling component over Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) units or Transformer-based architectures for several reasons. GRUs offer a simplified gating mechanism with fewer parameters compared to LSTMs, which results in faster training, reduced memory footprint, and lower computational cost—an essential aspect of our design aimed at lightweight and energy-efficient deployment. Despite this simplicity, GRUs retain the capacity to effectively model long-range dependencies in sequential data. In our case, the input sequence is generated by replicating static spatial features from the CNN output over multiple time steps, simulating temporal dynamics to align with the spiking layers. The GRU layers—implemented as two stacked bidirectional units with a hidden size of 256 and dropout rate of 0.3—allow the model to learn contextual representations across these repeated frames.

Transformer-based models were also considered, but they were excluded due to their data-hungry nature, reliance on positional embeddings, and high computational demands, which conflict with our objectives of model compactness, interpretability, and energy efficiency. Given our dataset size and use-case constraints, GRUs provided an optimal balance between temporal expressiveness and architectural simplicity, seamlessly integrating into our CNN-GRU-SNN pipeline.

The novel planned strategy

The proposed approach is described in Table 1:

Results

These metrics provide a comprehensive view of the model’s accuracy, precision, sensitivity to positive cases, and overall predictive balance. The following mathematical formulations were used26:

where: \(\text{TP}=\) True Positives (correctly identified pneumonia cases). \(\text{TN}=\) True Negatives (correctly identified normal cases). \(\text{FP}=\) False Positives (normal cases incorrectly labeled as pneumonia). \(\text{FN}=\) False Negatives (pneumonia cases missed by the model).

Ablation study

To validate the model’s performance and address concerns about overfitting, we conducted ablation studies comparing two versions of the model: one with GRU and one without it.

Model without GRU

When GRU was removed, the model relied solely on SNN. The performance dropped significantly:

-

Accuracy: 96.32%

-

Precision: 96.22%

-

Recall: 96.2%

-

F1-Score: 96.54%

-

AUC-ROC: 0.96

-

Loss curve:

-

The training and validation losses decrease steadily over epochs, indicating that the model is learning effectively.

-

The loss values start around 0.6 and decrease to approximately 0.1 by epoch 30.

-

The training and validation losses are close, suggesting that the model is not overfitting.

-

-

Accuracy curve:

-

The training and validation accuracies increase steadily over epochs.

-

The accuracy starts around 60% and reaches approximately 96% by epoch 30.

-

The training and validation accuracies are close, indicating good generalization.

-

-

Interpretation:

-

The standalone SNN model performs well, with low loss and high accuracy.

-

The model generalizes well to unseen data, as evidenced by the close training and validation curves.

-

Model with GRU

When GRU was reintroduced, the model achieved:

-

Accuracy: 99.35%

-

Precision: 99.1%

-

Recall: 99.5%

-

F1-Score: 99.1%

-

AUC-ROC: 0.99

-

Loss curve:

-

The training and validation losses decrease more sharply compared to the standalone SNN model.

-

The loss values start around 0.6 and decrease to approximately 0.1 by epoch 30.

-

The training and validation losses are very close, indicating minimal overfitting.

-

-

Accuracy curve:

-

The training and validation accuracies increase more rapidly compared to the standalone SNN model.

-

The accuracy starts around 90% and surpasses 99% by epoch 30.

-

The training and validation accuracies are very close, suggesting excellent generalization.

-

-

Interpretation:

-

The SNN-GRU hybrid model outperforms the standalone SNN model in terms of both loss reduction and accuracy improvement.

-

The hybrid model learns faster and achieves higher accuracy, likely due to the incorporation of the GRU layer, which captures temporal dependencies in the data.

-

Robustness study

Figure 9 presents a comparative visualization of how different types of image perturbations—Gaussian blur, salt-and-pepper noise, and speckle noise—affect model predictions for two distinct classes: “Normal” and “Pneumonia.” Both figures are organized in a 3 × 3 grid layout, with each row dedicated to a specific perturbation type tested at three increasing intensity levels. The first part, titled ”Effect of Noise and Blur on Model Predictions for Normal Class,” focuses on images where the ground-truth label is “Normal,” represented as the one-hot encoded vector [0. 1.]. The second figure, ”Effect of Noise and Blur on Model Predictions for Pneumonia Class,” examines images labeled as “Pneumonia,” encoded as [1. 0.]. Each subplot displays a perturbed image alongside labels indicating the Real Class (consistent across all subplots within a figure) and the Predicted Class (identical to the real class in all cases). The perturbations include Gaussian blur (σ = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6), salt-and-pepper noise (probabilities = 0.05, 0.1, 0.15), and speckle noise (σ = 0.1, 0.2, 0.3). Across both parts, the model’s predictions align perfectly with the true class labels, regardless of perturbation type or intensity.

Experimental setup

The training pipeline was executed on Kaggle using a Tesla P100 GPU. Optimization relied on Adam with both the learning rate and weight decay set to 1 × 10⁻5 to promote better generalization. A OneCycleLR learning-rate scheduler spanned the full training duration (30 epochs’ worth of iterations) to ensure steady convergence, while categorical cross-entropy served as the loss criterion and training halted early if no improvement appeared over five consecutive epochs. We processed data in batches of 32 for seven total epochs. All chest X-rays were converted to 128 × 128 grayscale arrays with three identical channels to match pretrained CNN input requirements. To address class imbalance and enhance model robustness, we applied zoom transforms, horizontal flips, brightness shifts, and SMOTE oversampling.

Notably, the SNN layers were trained using surrogate gradient backpropagation, allowing gradients to flow through the spiking units as part of the unified end-to-end optimization. This setup ensured that the CNN, GRU, and SNN blocks were jointly optimized during training while preserving biologically plausible spiking behavior through the use of discrete time steps and hidden state resets.

The diagrams in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 depict, in order, the Spatial Feature Extraction block, the Temporal Dynamics Modeling block, the Spiking Neural Processing block, the Decision Head block, and the overall network architecture. Table 1 provides a comprehensive breakdown of the model’s layers, showcasing how convolutional filters capture spatial patterns, bidirectional GRUs encode temporal relationships, and spiking neural modules—with integrated attention—select the most diagnostically relevant features. Table 2 presents the computational complexity metrics, including the number of learnable parameters (~ 8.63 million), multiply-accumulate operations (4.43 billion), FLOPs (4.48 billion), GPU memory requirements (around 3.76 GB), average training time per sample per epoch (0.0902 s), and energy consumption per sample (0.0038 Wh), underscoring the model’s balance of expressivity and efficiency suitable for deployment in resource-constrained healthcare settings.

Table 3 compares the proposed model with several established transfer learning architectures on the pneumonia chest X-ray dataset, where it stands out with a highest accuracy of 99.35%, surpassing competitive models such as Xception, DenseNet121, and ViT Transformer-based systems, along with other deep learning and quantum-enhanced methods. This underscores the advantage of the hybrid architecture incorporating spiking neural networks for robust classification performance. Table 4 extends this benchmark by comparing the proposed model against recent state-of-the-art algorithms by various authors, further affirming its top-tier accuracy among diverse AI approaches including CNN ensembles, generative adversarial networks, and quantum algorithms. Finally, Table 5 presents comprehensive cross-validation results to demonstrate the stability and robustness of the model, with accuracies across five folds consistently high and narrowly ranged from 98.39 to 99.19%, yielding a strong mean accuracy of 98.92%. This highlights the model’s reliability and effective generalization across different dataset partitions, essential for clinical applicability. Together, these tables clearly show the proposed model’s superior predictive accuracy, computational efficiency, and robustness, making it a compelling choice for automated and energy-efficient pneumonia diagnosis in varied healthcare environments.

The confusion matrix for our proposed model is displayed in Fig. 7. In this work, the choice and application of data augmentation techniques had a significant effect on each model’s results. Figure 8 compares training progress for two configurations: 8a shows accuracy and loss without the GRU component, and Fig. 8b shows the same metrics when the GRU is included. Each subfigure contains two plots: the left plot shows the loss values over epochs for training and validation/test sets, while the right plot depicts accuracy trends over the same epochs. In Fig. 8a, the loss and accuracy curves for the model without GRU exhibit fluctuations, particularly in the test loss curve. In contrast, Fig. 8b illustrates the curves for the proposed model incorporating GRU, where both loss and accuracy curves appear smoother, with a more stable convergence. The training and validation/test curves in both subfigures show a close alignment, indicating consistent performance across epochs. In Fig. 9, we illustrate the effect of noise and blur on model predictions for two distinct classes: Normal and Pneumonia. In both cases, the model demonstrates remarkable consistency and robustness across various levels of Gaussian blur, salt-and-pepper noise, and speckle noise. Figure 10 presents a series of chest X-ray images alongside attention maps and overlay visualizations for a classification model. The figure consists of three rows, each corresponding to a different sample. The leftmost column displays the original X-ray images with ground truth labels and model predictions. The middle column contains attention maps highlighting the regions the model focused on during classification, using a color scale where higher attention areas appear brighter. The rightmost column overlays these attention maps onto the original X-ray images, providing a combined visualization of the model’s focus areas within the chest X-rays. The attention mechanism was used post-classification to generate visual interpretability maps (akin to Grad-CAM) and did not influence the network’s prediction directly.

Discussion

The confusion matrix illustrated in Fig. 7 highlights the Hybrid SNN-GRU model’s efficacy in separating healthy subjects from pneumonia patients. Out of all samples, the network accurately identified 768 normal scans and 772 pneumonia scans, producing only 3 instances where healthy images were flagged as pneumonia and 7 cases where pneumonia images were labeled as normal. Such results translate into excellent sensitivity and specificity, showcasing the model’s capability to detect pneumonia reliably with minimal errors. Overall, the combination of spiking neural units and GRUs yields a dependable classification approach for pneumonia screening.

The comparison of accuracy and loss curves in Fig. 8a,b highlights the impact of integrating GRU into the model. In Fig. 8a (without GRU), the loss curves exhibit higher fluctuations, especially in the test set, indicating instability and potential overfitting. The accuracy curves also show noticeable variations, suggesting inconsistent generalization. In contrast, Fig. 8b (with GRU) demonstrates a smoother and more stable convergence in both training and validation loss curves, with lower final loss values. The accuracy curves in Fig. 8b also indicate a rapid and stable increase, reaching nearly 100% accuracy with minimal deviation between training and validation, suggesting improved generalization and robustness of the proposed model with GRU integration.

Figure 9 demonstrates the model’s robustness to image perturbations when classifying both “Normal” and “Pneumonia” chest X-ray images. For the Normal class (Part 1), the model consistently predicts the correct label ([0. 1.]) across all tested perturbations—Gaussian blur (σ = 0.2 to 0.6), salt-and-pepper noise (p = 0.05–0.15), and speckle noise (σ = 0.1–0.3). Similarly, for the Pneumonia class (Part 2), the model maintains perfect accuracy, predicting [1. 0.] under all distortion conditions. This suggests that the model is highly resilient to these types of noise and blur artifacts, which could mimic real-world image quality variations or sensor imperfections. The lack of misclassifications implies that the perturbations applied here do not degrade the model’s ability to distinguish between the two classes, even at higher noise intensities. However, this could also indicate that the model relies on features robust to these distortions or that the perturbations are not sufficiently severe to disrupt critical diagnostic patterns (e.g., lung opacities in pneumonia). Further investigation into more aggressive perturbations or adversarial attacks might reveal vulnerabilities, but within the tested range, the model performs reliably.

In the context Fig. 10 shows that the attention maps use a heatmap color scheme (e.g., yellow, orange, and red against darker backgrounds like purple or black) to visually represent the model’s focus on specific regions of the chest X-ray. Bright, warm colors (yellow/white) indicate areas of high attention, meaning the model heavily relied on these regions to make its prediction. For example, in pneumonia cases, these bright spots often align with pathological signs like lung opacities or consolidations—critical indicators of infection. Conversely, dark, cool colors (purple/black) denote low attention, reflecting regions the model deemed less relevant, such as background tissue or artifacts. In normal cases, the attention map typically shows faint, diffuse warm tones spread across healthy lung fields, signaling the absence of abnormalities. This figure demonstrates how an AI model analyzes chest X-rays by visualizing its decision-making process through attention maps. For a normal case, labeled “True: NORMAL” and correctly predicted as “Pred: NORMAL,” the attention map reveals a broad, low-intensity focus on healthy anatomical structures such as clear lung fields and ribcage, indicating the model’s reliance on the absence of abnormalities to confirm normality. This diffuse activation pattern, overlaid on the original image, contextualizes the model’s confidence in identifying unremarkable anatomy. In contrast, for pneumonia cases marked “True: PNEUMONIA” and accurately predicted as “Pred: PNEUMONIA,” the attention maps highlight concentrated regions of high activation, pinpointing pathological features like lung opacities, consolidations, or interstitial infiltrates—key indicators of pneumonia. These areas align with visible abnormalities in the X-rays, particularly in regions such as the lower lung zones where infections often manifest. By overlaying the attention heatmaps onto the original images, the figure illustrates how the model mimics clinical reasoning, focusing on clinically relevant regions to distinguish healthy from pneumonia cases. This visual transparency not only validates the model’s diagnostic accuracy but also underscores its capacity as an interpretable tool for radiologists, bridging AI-driven insights with human-understandable explanations to enhance trust and usability in medical practice. Beyond predictive performance, we present an estimation of the model’s energy consumption at approximately 0.0038 Wh per training epoch per sample. This aligns with recent studies highlighting the energy efficiency of spiking neural networks, especially when deployed on neuromorphic hardware which exploits event-driven and sparse computation. Prior research reports up to 8 × reductions in energy use compared to conventional CNNs without sacrificing accuracy27,28,29,30. However, practical realization of these savings is contingent on hardware and workload suitability. Future work will focus on benchmarking these aspects with neuromorphic implementations to substantiate energy benefits in clinical settings.

Conclusion

A new hybrid framework combining convolutional layers, gated recurrent units, and spiking neurons has been developed for biomedical image categorization. Convolutional layers extract spatial patterns, GRUs model sequential dependencies, and SNNs add a biologically inspired, event-driven processing element. An embedded attention module dynamically highlights the most informative features, boosting both predictive accuracy and transparency. In benchmark tests, this architecture delivered 99.35% accuracy, 99.1% precision, 99.5% recall, a 99.1% F1-score, and a 0.99 AUC–ROC, all while maintaining efficient use of computational resources. Incorporating spiking neural units also enables low-energy inference and greater fault tolerance, making the system well suited to edge devices and neuromorphic hardware. Future efforts will target real-time operation, adaptation to additional imaging modalities, and mechanisms for ongoing learning in clinical workflows.

Limitations and challenges

The proposed model faces several limitations and challenges, including computational complexity due to the integration of three distinct architectures (convolutional, spiking, and recurrent layers), which increases training time and resource demands. Training compatibility between CNN (gradient-based) and SNN (spike-timing-dependent) components can lead to optimization instability, as their learning mechanisms differ fundamentally. Data requirements are heightened, as SNNs often need large, temporally rich datasets to simulate spiking dynamics, which may not align with static medical imaging data like chest X-rays. Although the integrated attention mechanism improves interpretability by localizing image regions relevant to diagnostic decisions, the overall hybrid architecture (CNN-GRU-SNN) introduces complexity that may make model behavior less transparent compared to simpler models. Full interpretability remains a challenge, and future work is required to further dissect and visualize internal representations of hybrid spiking models. Additionally, interpretability is reduced in such hybrid models, complicating clinical trust, while hardware constraints (e.g., deploying SNNs on neuromorphic systems) and limited benchmarks for hybrid architectures in medical domains further hinder practical implementation and validation.

Future directions

While the current study demonstrates the model’s robustness to noise, future work will focus on further evaluating its performance in diverse clinical settings. This includes testing the model on data from low-field MRI scanners, which are more prone to noise, and assessing its ability to handle patient motion artifacts. Additionally, we aim to explore the integration of advanced noise reduction techniques to improve diagnostic reliability in challenging environments. Also, future research will investigate strategies to reduce the computational demands of the model for real-world deployment. This includes exploring model compression techniques, such as quantization and pruning, to enable efficient operation on standard hardware. Furthermore, we plan to evaluate the feasibility of edge deployment, allowing the model to run on portable devices or cloud-based platforms, thereby enhancing its accessibility in resource-constrained settings.

Data availability

The Pneumonia Chest X-ray dataset used in this paper is publicly available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/paultimothymooney/chest-xray-pneumonia.

References

Albaum, J. M. et al. Interobserver variability in the interpretation of chest roentgenograms of patients with possible pneumonia. JAMA Intern. Med. 154(23), 2729–2732. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1994.00420230122014 (1994).

Davies, M. et al. Advancing neuromorphic computing with Loihi: A survey of results and future directions. Front. Neurosci. 15, 632756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.632756 (2021).

Schuman, C. D. et al. Neuromorphic computing: From materials to systems architecture. Nat. Electron. 5(6), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-022-00779-9 (2022).

Luján-García, J. E. et al. A transfer learning method for pneumonia classification and visualization. Appl. Sci. 10(8), 2908 (2020).

Jiang, Z.-P. et al. An improved VGG16 model for pneumonia image classification. Appl. Sci. 11(23), 11185 (2021).

Mabrouk, A. et al. Pneumonia detection on chest X-ray images using ensemble of deep convolutional neural networks. Appl. Sci. 12(13), 6448 (2022).

Singh, S. & Tripathi, B. K. Pneumonia classification using quaternion deep learning. Multimed. Tools Appl. 81(2), 1743–1764 (2022).

Kiliçarslan, S. et al. Detection and classification of pneumonia using novel Superior Exponential (SupEx) activation function in convolutional neural networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 217, 119503 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Multi-domain medical image translation generation for lung image classification based on generative adversarial networks. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 229, 107200 (2023).

Xie, P., Zhao, X. & He, X. Improve the performance of CT-based pneumonia classification via source data reweighting. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 9401 (2023).

Kareem, A., Liu, H. & Velisavljevic, V. A federated learning framework for pneumonia image detection using distributed data. Healthcare Anal. 4, 100204 (2023).

Kaya, M. & Çetin-Kaya, Y. A novel ensemble learning framework based on a genetic algorithm for the classification of pneumonia. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 133, 108494 (2024).

Mustapha, B. et al. Enhanced pneumonia detection in chest X-rays using hybrid convolutional and vision transformer networks. Curr. Med. Imag. 21, e15734056326685 (2025).

Tian, X., Ren, J., Ren, Q., Song, W., Li, H., & Li, C. (2022). Recent advances on spiking neural networks: A review. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2201.04302

Zheng, Y., Yang, X., Wang, S., Zhou, J. & Yang, C. Deep spiking neural networks: A survey. IEEE Access 10, 55140–55153. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3172108 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Energy-efficient spiking neural network for image classification using hybrid training. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 34(6), 2390–2401. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3212863 (2023).

Lee, J., Kim, J., Park, J. & Kim, S. Quantitative assessment of energy efficiency of spiking neural networks vs. CNNs. IEEE Trans. Act. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 33(9), 4324–4335. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2021.312345 (2022).

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/paultimothymooney/chest-xray-pneumonia.

Chawla, N. V. et al. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 16, 321–357 (2002).

Islam, J. & Zhang, Y. Brain MRI analysis for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis using an ensemble system of deep convolutional neural networks. Brain Inf. 5(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40708-018-0080-3 (2018).

Mehmood, A., Maqsood, M., Bashir, M. & Shuyuan, Y. A deep siamese convolution neural network for multi-class classification of Alzheimer disease. Brain Sci. 10(2), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10020084 (2020).

Wong, P. C., Abdullah, S. S. & Shapiai, M. I. Exceptional performance with minimal data using a generative adversarial network for alzheimer’s disease classification. Sci. Rep. 14, 17037. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66874-5 (2024).

Aborokbah, M. Alzheimer’s disease MRI classification using EfficientNet: A deep learning model. In: 2024 4th International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence (ICAPAI). 1–8 (IEEE, 2024).

Shahwar, T., Mallek, F., Ur Rehman, A., Sadiq, M. T. & Hamam, H. Classification of pneumonia via a hybrid ZFNet-quantum neural network using a chest X-ray dataset. Curr. Med. Imag. Rev. 20, e15734056317489. https://doi.org/10.2174/0115734056317489240808094924 (2024).

Mustapha, B., Zhou, Y., Shan, C. & Xiao, Z. Enhanced pneumonia detection in chest X-rays using hybrid convolutional and vision transformer networks. Curr. Med. Imag. Rev. 21, e15734056326685. https://doi.org/10.2174/0115734056326685250101113959 (2025).

Hossin, M. & Sulaiman, M. N. A review on evaluation metrics for data classification evaluations. Int. J. Data Min. Knowl. Manag. Process. 5, 1 (2015).

Yan, S., Cui, W. & Zhao, M. Review on spiking neural networks in medical image analysis. Neural Netw. 146, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2021.12.011 (2022).

Rueckauer, B., Lungu, I. A., Hu, Y. & Delbruck, T. Conversion of continuous-valued deep networks to efficient event-driven networks for image classification. Front. Neurosci. 11, 682. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2017.00682 (2017).

Lee, J., Kim, J., Park, J. & Kim, S. Quantitative assessment of energy efficiency for spiking neural networks vs CNNs. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 33(9), 4324–4335. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2021.312345 (2022).

Alexandrov, A., Muller, L., Grimaldi, D. & Keller, T. Energy estimation framework for spiking neural networks on neuromorphic hardware. IEEE Trans VLSI Syst 31(2), 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVLSI.2023.323456 (2023).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: H.S, A.B; Methodology: H.S; Software: H.S; Validation: H.S, A.B, S.A; Formal Analysis: H.S; Investigation: H.S, M.S; Resources & Data Curation: H.S; Writing—Original Draft: H.S; Writing—Review & Editing: H.S, A.B, S.A, M.S; Visualization: H.S; Supervision & Project Administration: M.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors state that no known competing financial interest or personal relationship may have had any influence on any of the work disclosed in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Slimi, H., Balti, A., Abid, S. et al. Trustworthy pneumonia detection in chest X-ray imaging through attention-guided deep learning. Sci Rep 15, 40029 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23664-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23664-x