Abstract

Employee well-being has increasingly emerged as a central concern for both organizations and society. However, our understanding of how and when inclusive leadership enhances employee well-being remains limited. Based on self-determination theory and the socially embedded model of thriving at work, this study explored the relationship between inclusive leadership, growth need strength, employee thriving at work, and well-being. Data were collected from 62 teams that totaled 337 full-time employees through a three-wave time-lagged questionnaire. Path analysis and Monte Carlo simulations were conducted on data for hypothesis testing. The results showed that inclusive leadership is positively related to employee well-being. Employee thriving at work played a mediating role between inclusive leadership and employee well-being. Growth need strength moderated the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee thriving at work. These findings are expected to provide valuable insights for organizations aiming to enhance employee thriving at work and well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Employee well-being has increasingly emerged as a central concern for both organizations and society. Most employees actively strive to maintain their well-being1,2. However, various workplace stressors, including intensified competition, excessive job demands, and intrusive or authoritarian leadership styles, often undermine these efforts, resulting in elevated stress, greater burnout, and worsening mental health3,4,5. Managers therefore face the ongoing challenge of balancing performance demands with protecting employees’ well-being.In the Chinese workplace, where burnout and stress are widespread, this challenge is particularly pronounced and remains underexplored in research6. Identifying ways to improve employee well-being has thus become an urgent research priority7,8.

Inclusive leadership has recently gained attention as a promising approach to enhancing employee well-being2. Unlike transformational leadership, which motivates through vision, and servant leadership, which emphasizes altruism and follower development9,10, inclusive leadership highlights fairness, openness, and the recognition of diverse perspectives11,12,13. By acknowledging and valuing differences, inclusive leaders are more likely to satisfy employees’ intrinsic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, as articulated in self-determination theory (SDT)14,15,16. Fulfilling these needs fosters improved well-being, particularly in diverse and high-pressure contexts such as China. Empirical research supports the positive link between inclusive leadership and employee well-being across various contexts. For instance, inclusive leadership enhances older workers’ well-being through mature-age HR practices17and strengthens knowledge workers’ well-being via psychological contract fulfillment18. It also promotes workplace well-being by improving vigor2 and person–job fit19. At a broader level, CEOs’ inclusive leadership cascades through managerial practices and departmental climates to influence employee well-being8. Psychological capital20, climate for inclusion21, and psychological safety22 are also considered important mechanisms linking inclusive leadership to employee well-being. However, existing research has largely focused on workplace well-being and contextual or relational mechanisms, with limited attention to employees’ intrinsic psychological needs2,23,24. This omission is notable given positive psychology’s emphasis on internal motivational processes in shaping well-being. Furthermore, most studies have been conducted in Western contexts25. Chinese employees, however, face unique challenges, including intense competition, long working hours, and high expectations, which increase well-being concerns6. Examining how inclusive leadership addresses intrinsic psychological needs in China can therefore offer culturally relevant insights and practical guidance for organizations operating in high-pressure environments.

To address these gaps, we developed a moderated mediation framework based on SDT and the socially embedded model of thriving at work to understand how and when inclusive leadership impacts employee well-being. SDT suggests that individuals function most effectively when their basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are satisfied, which in turn promotes well-being14,15,16. Building on this perspective, Spreitzer et al.26 proposed the socially embedded model of thriving at work, which defines thriving as a psychological state in which individuals experience both vitality and learning. The model suggests that when individuals’ basic needs are met at work, they experience thriving. Thus, we propose that thriving at work serves as a key mediating mechanism through which inclusive leadership promotes employee well-being. Inclusive leadership is characterized by behaviors that promote fairness, recognize individual differences, and encourage employees to utilize their unique perspectives and skills2,12,13,26,27. These behaviors create an environment that supports employees’ needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, thereby enhancing intrinsic motivation15. Motivated employees are more likely to experience thriving at work28,29,30. Thriving at work, in turn, enables employees to manage stress, cultivate positive emotions, achieve higher job satisfaction, and ultimately improve overall well-being7,31,32,33,34,35,36,37.

Leadership research also highlights that the effectiveness of leadership behaviors depends on contextual factors. Employees with different characteristics may exhibit varied responses to inclusive leadership38,39,40,41. Research shows that employees with stronger growth needs are more likely to actively engage with their leaders to advance their development42,43,44. Therefore, we propose that growth need strength moderates the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee thriving at work. Growth need strength refers to a personality trait that reflects the desire for achievement, learning, and development at work45,46. Employees with high growth-need strength tend to be proactive, value personal development, and seek challenging tasks47. They are therefore more likely to take advantage of the resources and support provided by inclusive leaders, which enhances their experience of thriving at work44,48,49. By contrast, employees with low growth need strength place less emphasis on personal development and derive fewer benefits from inclusive leadership.

This study advances the literature in three ways. First, it broadens the scope of inclusive leadership research by shifting attention from performance- and engagement-related outcomes to employees’ psychological well-being, thereby underscoring leaders’ role in fulfilling employees’ intrinsic needs at work. Second, building on SDT and the socially embedded model of thriving at work, this study positions thriving as the core explanatory mechanism. It clarifies how inclusive leadership promotes employee well-being by fostering the dual experiences of energy and learning. Third, it introduces growth need strength as a critical boundary condition, demonstrating that inclusive leadership is particularly effective for employees with strong intrinsic motivation for personal development.

Theory and development of the hypothesis

Theoretical background

SDT posits that individuals possess three fundamental psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness14,15,16. These needs are essential for fostering intrinsic motivation and supporting well-being. When these needs are satisfied, employees are more likely to experience vitality, growth, and psychological health. Conversely, when these needs are frustrated, employees tend to encounter stress, disengagement, and diminished functioning. Drawing on this framework, organizational scholars increasingly use SDT to explain how leadership, human resource practices, and job design shape employee outcomes through need satisfaction2,50,51.

Building on SDT, Spreitzer et al.26 proposed the socially embedded model of thriving at work, which offers a complementary lens on how work contexts enable employees to thrive. This model suggests that when individuals’ three basic psychological needs are satisfied, they experience thriving—a state characterized by vitality and learning.

Our study integrates these two perspectives by emphasizing thriving at work as a key psychological pathway linking inclusive leadership to employee well-being. Inclusive leadership meets team members’ basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness by fostering fairness, openness, and recognition of diverse perspectives within the team. When these basic needs are satisfied, employees are more likely to experience thriving, which in turn enhances their well-being. In line with calls by Broeck et al.’s 53 call to extend SDT by incorporating higher-level needs, we further treat employees’ growth need strength as a boundary condition. Employees with stronger growth needs are especially sensitive to opportunities for development and achievement and are thus more likely to experience thriving under inclusive leadership, whereas employees with lower growth need strength may benefit less45,49,52.

Inclusive leadership and employee well-being

Employee well-being refers to employees’ overall evaluation of their quality of work life53,54. It encompasses three interrelated dimensions: life well-being, workplace well-being, and psychological well-being. Life well-being captures positive emotions and life satisfaction55. Workplace well-being refers to job satisfaction and other work-related outcomes56. Psychological well-being reflects self-acceptance, purpose, environmental mastery, positive relationships, autonomy, and personal growth57,58. Together, these dimensions allow employees to experience fulfillment, emotional stability, effective conflict management, and self-actualization59. Employees with high levels of well-being tend to demonstrate greater motivation, creativity, engagement, and performance, while also showing lower levels of deviance and turnover intentions25,60,61,62,63.

Inclusive leadership was first conceptualized by Nembhard and Edmondson64, who described it as a leadership style that encourages voice, values input, and acknowledges contributions. Hollander11 highlighted its collaborative and participatory nature, emphasizing mutual influence and attention to followers’ needs. Carmeli et al.28 defined it as a relational approach characterized by openness, accessibility, and presence. Shore et al.27 further argued that inclusive leaders cultivate both a sense of belonging and recognition of uniqueness, thereby enabling members to feel fully integrated. Building on these foundations, subsequent research identified six core inclusive leadership behaviors. Three of them foster belonging—providing support, ensuring fairness, and encouraging participatory decision-making—while the other three promote uniqueness by seeking diverse input, valuing different perspectives, and enabling individuals to contribute their strengths12,13. A growing body of research demonstrates that leadership style is a key antecedent of employee well-being2,8,19. Inclusive leaders who remain attentive and responsive to their employees’ needs enhance positive emotions and job satisfaction65,66. These outcomes are central components of well-being25,54. Therefore, we argue that inclusive leadership is positively related to employee well-being. Research also shows that inclusive leadership enhances employee well-being through diverse mechanisms, such as HR practices for older workers17, psychological contract fulfillment18, person-job fit19 and inclusive climate8,21. It also fosters well-being via psychological capital20 and psychological safety22. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 1

Inclusive leadership is positively related to employee well-being.

The mediating role of employee thriving at work

SDT argues that individuals reach optimal functioning and experience well-being when their basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are satisfied14,15,16. Building on this perspective, Spreitzer et al. 26 developed the socially embedded model of thriving at work, which suggests that thriving occurs when these needs are fulfilled. Thriving at work is defined as a psychological state characterized by both vitality and learning67. Vitality refers to energy and enthusiasm, whereas learning denotes continual improvement and skill development33,67. Research shows that thriving benefits employees by enhancing health and development, and supports organizations by promoting innovation and sustainable performance7,68,69,70,71.

Drawing on SDT, we argue that inclusive leadership can foster thriving by satisfying employees’ psychological needs. First, when leaders share authority and empower followers, employees are more likely to thrive68. Inclusive leaders support team members’ autonomy by welcoming their perspectives, encouraging proactive behavior, and responding thoughtfully to initiatives72,73. This autonomy support fulfills employees’ need for self-direction, enhancing intrinsic motivation15, which in turn fosters vitality at work16,28,29. Second, inclusive leadership prioritizes quality interpersonal relationships11. Inclusive leaders model prosocial behavior, encourage acceptance, and treat team members equitably, which strengthens group belonging and vitality2,12,16. Employees experience greater vitality when relational needs are met30,74. Moreover, inclusive leaders foster team success by leveraging employees’ strengths and encouraging diverse perspectives, which spark meaningful contributions and innovative ideas12,13,26,75. Through these collaborative team activities, employees acquire new knowledge and skills, which in turn cultivates a sense of thriving at work37.

We further argue that thriving at work enhances employee well-being. Feelings of vitality are positively associated with job satisfaction and psychological health, while reducing stress, depression, and negative affect2,7,33,34. Similarly, the learning component of thriving promotes skill development, enhances job satisfaction, and contributes to psychological and physical well-being33,35,36,76. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 2

Employee thriving at work mediates the positive connection between inclusive leadership and employee well-being.

The moderating role of growth need strength

Although inclusive leadership has been shown to enhance team creativity, innovation, and well-being27,38,41,77, some studies indicate that its effectiveness depends on context. For example, Leroy et al.40 found that inclusive leadership may reduce creativity when teams lack an understanding of diversity. Similarly, Ma and Tang reported that it can weaken engagement when diversity is too high40. These findings highlight the importance of considering situational factors when examining inclusive leadership. Building on SDT, we previously argued that inclusive leadership promotes employee thriving by satisfying the basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. However, higher-order personal needs, especially the need for personal growth, may further shape work experiences. Thus, we argue that employees’ growth need strength moderates the relationship between inclusive leadership and thriving at work. Employees with strong growth needs actively pursue opportunities for self-development and achievement42,43,44,49. They are motivated to take on challenges, exercise independence, and deepen their work engagement47. Inclusive leaders who provide developmental opportunities and recognize employees’ unique strengths create conditions that align with these aspirations12. As a result, employees high in growth need strength are more likely to thrive at work44,48,78. In contrast, employees low in growth need strength place less value on opportunities for learning and development, and may show limited responsiveness to inclusive leadership45,79. For these employees, inclusive leadership may have weaker effects on thriving, as they are less inclined to leverage the autonomy support, encouragement, and resources provided. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 3

Growth need strength moderates the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee thriving, such that the relationship will be stronger when growth need strength is higher.

Hypotheses 2 and 3 can be combined to introduce a mediation of moderation: Employee thriving mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee well-being, and this process of mediation is moderated by growth need strength. Thus, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 4

Growth need strength moderates the mediating role of thriving in the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee well-being such that the mediating effect of thriving is stronger when growth need strength is high.

Method

Participants and procedures

We employed a three-wave survey design with approximately one-month intervals between each wave. To obtain a diverse sample, we collaborated with Sojump, a professional Chinese survey platform, which assisted in recruiting 82 full-time work teams. Participants were informed about the study’s purpose and procedures, and anonymity was guaranteed. At Time 1, 500 questionnaires were distributed across 82 teams to collect data on inclusive leadership, growth need strength, and demographic variables. We received 467 responses from 77 teams. At Time 2, these participants were re-contacted to assess thriving at work, resulting in 411 responses from 66 teams. At Time 3, the 411 respondents were surveyed again to measure employee well-being, yielding 337 valid responses from 62 teams. Among the respondents, 41.8% were male and 58.2% were female. Regarding age, 60.2% were 30 years or younger, 34.1% were between 31 and 40 years, and 5.7% were over 40. In terms of education level, 88.7% held at least a bachelor’s degree. With respect to tenure, 47.8% had less than five years of work experience, 41.5% had five to ten years, 8.0% had ten to fifteen years, and 2.7% had more than fifteen years.

Measurements

Inclusive leadership We measured inclusive leadership using the 11-item Inclusive Leadership Scale developed by Fang et al.78, which was specifically designed for the Chinese context. A sample item is: “The leader treats employees fairly when providing job-related support.” Cronbach’s α was 0.916. Because the items were rated by individual employees, we aggregated scores to the team level. The aggregation was justified by the following indicators: ICC1 = 0.448, ICC2 = 0.817, and average Rwg = 0.970, all of which exceed established thresholds for within-group agreement and between-group reliability80.

Thriving at work Thriving at work was assessed using the 10-item scale developed by Porath et al.34. This scale consists of two dimensions, learning and vitality, each measured with five items A sample item is: “I am full of energy and vitality.” Cronbach’s α was 0.924.

Growth need strength Growth need strength was measured using the seven-item scale developed by Hackman and Oldham46, which assesses employees’ desire for learning, challenges, and development in their work. A sample item is: “I really like exciting and challenging work.” Cronbach’s α was 0.807.

Employee well-being Employee well-being was measured using the 18-item scale developed by Zheng et al.56. This scale was originally developed and validated in the Chinese context, making it particularly suitable for our study population. It comprises three dimensions: workplace well-being, life well-being, and psychological well-being, each with six items. A sample item is: “I am generally satisfied with the sense of fulfillment I get from my current job.” Cronbach’s α was 0.941.

Control variables Following prior studies7,20,30, we controlled for gender, age, education, and tenure, as these variables may influence employee well-being.

Analytical strategies

We first conducted descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations in SPSS 26 and performed Harman’s single-factor test to assess potential common method bias (CMB). Next, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in Mplus 7.4 to examine the discriminant validity of the study variables. Structural path modeling in Mplus 7.4 was then used to test the proposed hypotheses. Finally, to verify the indirect and moderated effects, we conducted Monte Carlo simulations with 100,000 iterations using R version 4.3.2.

Results

Preliminary analyses

The Harman’s single-factor test revealed that the first factor explained only 28.681% of the variance, far below the conventional threshold of 40%. This suggests that common method bias is unlikely to pose a serious problem in this study. Table 1 shows the results of the CFA. the fit of the hypothesized four-factor model (χ² = 1544.493, df = 896, CFI = 0.916, TLI = 0.911, RMSEA = 0.046, SRMR = 0.047) was better than the fit of the alternative models.

Descriptive statistics and correlations for all the variables are presented in Table 2.

Hypotheses testing

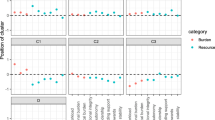

Figure 1 shows the results of path analysis. Inclusive leadership has a significant positive effect on employee well-being (β = 0.364, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. Inclusive leadership significantly and positively correlated with employee thriving at work (β = 0.510, p < 0.01), and thriving at work significantly and positively correlated to well-being (β = 0.418, p < 0.01), suggesting that employee thriving at work mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee well-being. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was confirmed. The interaction term of growth need strength and inclusive leadership had a significant effect on employee thriving at work (β = 0.440, p < 0.01), which supported Hypothesis 3.

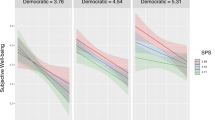

Figure 2 shows the results of simple slope analyses. When employees had a low level of growth need strength (M - SD), the relationship between inclusive leadership and employee thriving at work (β = 0.344, p < 0.001) was significant. When employees reported high levels of growth need strength (M + SD), the positive association between inclusive leadership and thriving at work became stronger (β = 0.675, p < 0.001), providing support for Hypothesis 3.

Results of the Monte Carlo simulation (100,000 resamples) are shown in Table 3. The indirect effect of inclusive leadership on employee well-being via thriving at work was significant (95% CI = [0.065, 0.401]), as the interval does not include zero, supporting Hypothesis 2. Additionally, the indirect effect was significant at both high (95% CI = [0.091, 0.509]) and low (95% CI = [0.033, 0.312]) levels of growth need strength. The difference between these conditional indirect effects was also significant (95% CI = [0.035, 0.271]), indicating that growth need strength moderates the mediating role of thriving at work, confirming Hypothesis 4.

Discussion

Grounded in SDT and the socially embedded model of thriving at work, this study examined how and when inclusive leadership influences employees’ well-being. The findings highlight three key results. First, inclusive leadership positively predicts employee well-being. Second, thriving at work mediates this relationship. Third, growth need strength strengthens the positive effect of inclusive leadership on thriving, thereby amplifying its indirect impact on well-being.

Theoretical contribution

This study makes several theoretical contributions to the leadership and well-being literature. First, it broadens the understanding of inclusive leadership by shifting the research focus from performance- and engagement-related outcomes to employees’ well-being. Inclusive leadership is often linked to innovation and team effectiveness12,13,75. However, its impact on mental health has received little attention. Our study examines inclusive leadership from the perspective of employees’ psychological needs, showing that it functions as a key resource that reduces stress and satisfies intrinsic needs to promote well-being3,4,5. This is vital in workplaces with rising job demands and burnout6. Our study responds to calls for leadership research focused on employee flourishing and mental health1,5,81.

Second, we demonstrate that thriving at work is the psychological mechanism linking inclusive leadership and employee well-being. Prior research has examined how inclusive leadership influences employee well-being from various perspectives, including HR practices, contract fulfillment, vigor, person–job fit, psychological capital, inclusion climate, and psychological safety8,17,18,19,20,21,22. However, most studies have overlooked employees’ basic psychological needs. Although Liu et al.2 acknowledged the importance of need satisfaction, their focus was restricted to workplace well-being. By integrating SDT with the socially embedded model of thriving at work, we propose and demonstrate that inclusive leadership fosters employees’ thriving at work by meeting their needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Employees who experience thriving at work also exhibit higher levels of well-being. This finding extends prior work7,71 by illuminating the underlying psychological mechanism and deepening our understanding of how inclusive leadership operates. It also advances the literature on thriving at work by positioning it as a critical bridge between leadership behaviors and employee well-being.

Third, this study identifies growth need strength as a key boundary condition that clarifies when inclusive leadership is more effective in fostering employee well-being. Prior research has explored contextual moderators such as supervisor family motivation20 or organizational structure8. However, relatively little attention has been paid to individual differences. Our findings show that employees with strong growth needs value developmental opportunities, actively engage with inclusive leaders42,43, and consequently experience higher levels of thriving and well-being. This extends SDT-based research beyond basic need satisfaction2,82 by incorporating aspirations for personal growth. Adopting a person-centered perspective, we demonstrate that inclusive leadership is particularly effective when aligned with employees’ intrinsic motivation for development. Thus, our model incorporates personality differences into the leadership–thriving–well-being pathway.

Practical implications

First, our findings indicate that inclusive leadership plays a critical role in enhancing employees’ work experiences and well-being. Organizations should therefore prioritize the development of inclusive leadership competencies. Employees are likely to benefit from inclusive leadership, particularly in the Chinese context, where high stress, extended working hours, and burnout are common6. This involves encouraging leaders to demonstrate empathy, openness, and recognition of employees’ contributions. Timely feedback and visible support can enhance employees’ sense of inclusion and psychological safety. We recommend that managers undergo training in inclusivity and effective communication. Such training should be designed to help managers address employees’ intrinsic needs and leverage them to foster a positive workplace.

Second, we recognize the positive role of thriving at work in promoting well-being. Employee thriving stems from the dual experience of energy and learning67,74. Organizations should therefore foster a supportive work environment. For example, companies can create a safe atmosphere that encourages idea generation and innovation while minimizing punitive responses to failure, thereby sustaining employees’ energy and learning. Additionally, organizations should provide systematic training, cross-role rotations, and open access to learning resources. These opportunities enable employees to continuously develop knowledge and skills, thereby sustaining learning, progress, and psychological energy.

Third, our research indicates that employees with a strong need for growth are key resources for organizational success. Therefore, HR managers should focus on acquiring, retaining, and developing such employees. HR practices should also prioritize identifying employees’ strengths and enhancing their capabilities, health, and well-being. Organizations can use scales developed by Hackman and Oldham46 or other validated psychometric scales during the recruitment process to assess candidates’ growth need strength. Furthermore, assessments should be tailored to specific organizational and work contexts. More importantly, HR managers and supervisors should communicate with employees, observe their behaviors and attitudes, and identify those with strong aspirations for achievement, learning, and personal development. Such employees should then be offered targeted developmental opportunities.

Research shortcomings and prospects

As with any study, our research also has several limitations. First, the data were collected through employee self-reports. Although statistical tests suggested no serious common method bias, future research could incorporate multi-source data (e.g., supervisor–subordinate dyads) to strengthen validity. Moreover, while this study employed a three-wave time-lagged design, it did not fully meet the criteria for longitudinal research. Longitudinal or quasi-experimental designs would allow stronger causal inferences regarding the dynamic relationships among inclusive leadership, thriving, and well-being.

Second, this study examined only one boundary condition: growth need strength. Future research could expand this scope by considering other individual differences, such as proactive personality, regulatory focus, or resilience. Exploring such traits would provide a richer understanding of when and for whom inclusive leadership is most effective in promoting thriving and well-being. Moreover, future investigations could examine the potential paradoxical effects of inclusive leadership, such as circumstances under which it might inadvertently contribute to role ambiguity or knowledge hiding, similar to some unintended consequences observed for other bottom-up leadership styles.

Third, the sample was drawn exclusively from organizations in China. Given cultural differences between Eastern and Western contexts, the generalizability of our findings may be constrained. To enhance external validity, future studies should test these relationships across diverse cultural settings, thereby advancing a cross-cultural perspective on inclusive leadership and employee well-being. In the current study, we did not focus on any specific sector or industry, and therefore could not examine sector-specific effects. Nevertheless, future studies could explore how inclusive leadership operates across different sectors or industries, which may provide practical guidance for enhancing employee well-being or reducing stress and burnout.

Data availability

The original data presented in this study are included in the supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Faraci, P., Bottaro, R., Valenti, G. D. & Craparo, G. Psychological well-being during the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic: the mediation role of generalized anxiety. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 15, 695–709 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Inclusive leadership and employee workplace well-being: the role of Vigor and supervisor developmental feedback. BMC psychol. 12, 540 (2024).

Kuriakose, V., Wilson, S. S., MR, A. & P. & The differential association of workplace conflicts on employee well-being: the moderating role of perceived social support at work. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 30, 680–705 (2019).

De Jonge, J. et al. Testing reciprocal relationships between job characteristics and psychological well-being: A cross‐lagged structural equation model. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 74, 29–46 (2001).

Khalid, A. & Syed, J. Mental health and well-being at work: A systematic review of literature and directions for future research. Hum Resour. Manage. Rev. 34, 100998 (2023).

Liu, J. & Zhang, Y. Entrepreneurship and mental well-being in china: the moderating roles of work autonomy and subjective socioeconomic status. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11, 1–10 (2024).

Zhu, M., Li, S., Gao, H. & Zuo, L. Social media use, thriving at work, and employee well-being: A mediation model. Curr. Psychol. 43, 1052–1066 (2024).

Cao, M., Zhao, Y. X. & Zhao, S. M. How ceos’ inclusive leadership fuels employees’ well-being: A three-level model. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 34, 2305–2330 (2023).

Sonnentag, S., Tay, L. & Nesher Shoshan, H. A review on health and well-being at work: more than stressors and strains. Pers. Psycho. 76, 473–510 (2023).

Bormann, K. C. & Rowold, J. Construct proliferation in leadership style research: reviewing pro and contra arguments. Organizational Psychol. Rev. 8, 149–173 (2018).

Hollander, E. Inclusive Leadership: the Essential leader-follower Relationship (Routledge, 2009).

Randel, A. E. et al. Inclusive leadership: realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Hum. Resour. Manage. Rev. 28, 190–203 (2018).

Korkmaz, A. V., Van Engen, M. L., Knappert, L. & Schalk, R. About and beyond leading uniqueness and belongingness: A systematic review of inclusive leadership research. Hum. Resour. Manage. Rev. 32, 1–20 (2022).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78 (2000).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Can. Psychol. 49, 14–23 (2008).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can. Psychol. 49, 182–185 (2008).

Teo, S. T., Bentley, T. A., Nguyen, D., Blackwood, K. & Catley, B. Inclusive leadership, matured age HRM practices and older worker wellbeing. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 60, 323–341 (2022).

Rogozińska-Pawełczyk, A. Inclusive leadership and psychological contract fulfilment: A source of proactivity and well-being for knowledge workers. Sustainability 15, 11059 (2023).

Choi, S. B., Tran, T. T. H. & Kang, S. W. Inclusive leadership and employee well-being: the mediating role of person-job fit. J. Happiness Stud. 18, 1877–1901 (2017).

Umrani, W. A., Bachkirov, A. A., Nawaz, A., Ahmed, U. & Pahi, M. H. Inclusive leadership, employee performance and well-being: an empirical study. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 45, 231–250 (2024).

Kuknor, S., Sharma, B. K. & Ouakouak, M. L. The relationship of inclusive leadership with organization-based self-esteem: mediating role of climate for inclusion. SAGE Open 15, 21582440251321994 (2025).

Ahmed, F., Zhao, F., Faraz, N. A. & Qin, Y. J. How inclusive leadership paves way for psychological well-being of employees during trauma and crisis: A three‐wave longitudinal mediation study. J. Adv. Nurs. 77, 819–831 (2021).

Chang, J. H., Huang, C. L. & Lin, Y. C. Mindfulness, basic psychological needs fulfillment, and well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 16, 1149–1162 (2015).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. The what and why of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psycholl Inq. 11, 227–268 (2000).

Diener, E., Oishi, S. & Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behavr. 2, 253–260 (2018).

Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A. & Singh, G. Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. J. Manag. 37, 1262–1289 (2011).

Carmeli, A., Reiter-Palmon, R. & Ziv, E. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: the mediating role of psychological safety. Creat Res. J. 22, 250–260 (2010).

Wang, Z. & Panaccio, A. Thriving in the dynamics: a multi-level investigation of needs-supportive features, situational motivation, and employees’ subjective well-being. Curr. Psychol. 42, 23669–23686 (2023).

Graves, L. M. & Luciano, M. M. Self-determination at work: Understanding the role of leader-member exchange. Motiv Emot. 37, 518–536 (2013).

Ellis, A. M., Bauer, T. N., Erdogan, B. & Truxillo, D. M. Daily perceptions of relationship quality with leaders: implications for follower well-being. Work Stress. 33, 119–136 (2019).

Van Hoek, L., Paul-Dachapalli, L. A., Schultz, C. M., Maleka, M. J. & Ragadu, S. C. Performance management, vigour, and training and development as predictors of job satisfaction in low-income workers. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 18, 1–10 (2020).

Keyes, C. L. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc. Behav. 43, 207–222 (2002).

Porath, C., Spreitzer, G., Gibson, C. & Garnett, F. G. Thriving at work: toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. J. Organ. behav. 33, 250–275 (2012).

Gil-Beltrán, E., Meneghel, I., Llorens, S. & Salanova, M. Get vigorous with physical exercise and improve your well-being at work! Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 17, 6384 (2020).

Abid, G., Ahmed, S., Elahi, N. S. & Ilyas, S. Antecedents and mechanism of employee well-being for social sustainability: A sequential mediation. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 24, 79–89 (2020).

Walumbwa, F. O., Muchiri, M. K., Misati, E., Wu, C. & Meiliani, M. Inspired to perform: A multilevel investigation of antecedents and consequences of thriving at work. J. Organ. behav. 39, 249–261 (2018).

Jiang, Z., Hu, X., Wang, Z. & Griffin, M. A. Enabling workplace thriving: A multilevel model of positive affect, team cohesion, and task interdependence. Appl. Psychol. 73, 323–350 (2024).

Duc, L. A. & Tho, N. D. Inclusive leadership and team innovation in retail services. Serv. Ind. J. 45, 330–350 (2023).

Leroy, H., Buengeler, C., Veestraeten, M., Shemla, M. & Hoever, I. J. Fostering team creativity through team-focused inclusion: the role of leader harvesting the benefits of diversity and cultivating value-in-diversity beliefs. Group. Organn Manag. 47, 798–839 (2022).

Ma, Q. & Tang, N. Too much of a good thing: the curvilinear relation between inclusive leadership and team innovative behaviors. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 40, 929–952 (2022).

Ye, Q., Wang, D. & Li, X. Inclusive leadership and employees’ learning from errors: A moderated mediation model. Aust J. Manag. 44, 462–481 (2019).

Rego, A. & Cunha, M. P. E. Do the opportunities for learning and personal development lead to happiness? It depends on work-family conciliation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 14, 334–348 (2009).

Franken, E., Plimmer, G. & Malinen, S. K. Growth-oriented management and employee outcomes: employee resilience as a mechanism for growth. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 44, 627–642 (2023).

Huo, M. L. Career growth opportunities, thriving at work and career outcomes: can COVID-19 anxiety make a difference? J. Hosp. Tour Manag. 48, 174–181 (2021).

Shalley, C. E., Gilson, L. L. & Blum, T. C. Interactive effects of growth need strength, work context, and job complexity on self-reported creative performance. Acad. Manage. J. 52, 489–505 (2009).

Hackman, J. R. & Oldham, G. R. Work Redesign (Addison-Wesley, 1980).

Bottger, P. C. The job characteristics model and growth satisfaction: main effects of assimilation of work experience and context satisfaction. Hum. Relat. 39, 575–594 (1986).

Jaiswal, N. K. & Dhar, R. L. The influence of servant leadership, trust in leader and thriving on employee creativity. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 38, 2–21 (2017).

Fang, Y., Liu, Y., Dai, X., Chen, N. & Li, Y. Growth need strength, learning from failures, and innovation performance: the moderating effect of inclusive leadership. Curr. Psychol. 44, 10807–10819 (2025).

Zhai, Y., Xiao, W., Sun, C., Sun, B. & Yue, G. Professional identity makes more work well-being among in-service teachers: mediating roles of job crafting and work engagement. Psychol. Rep. 128, 2983–3000 (2025).

Li, S. & Kung, F. Y. Supporting refugee employees’ psychological needs at work: the role of HRM practices. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 35, 183–219 (2024).

Hackman, J. & Oldham, G. R. Motivation through the design of work: test of a theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 16, 250–279 (1976).

Page, K. M. & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. The ‘what’,‘why’and ‘how’of employee well-being: A new model. Soc. Indic. Res. 90, 441–458 (2009).

Zheng, X. M., Zhu, W. C., Zhao, H. X. & Zhang, C. Employee well-being in organizations: theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. J. Organ. behav. 36, 621–644 (2015).

Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 95, 542–575 (1984).

Daniels, K. Measures of five aspects of affective well-being at work. Hum. Relat. 53, 275–294 (2000).

Ryff, C. D. & Keyes, C. L. M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 69, 719–727 (1995).

Ryff, C. D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 1069–1081 (1989).

Jaškevičiūtė, V. Trust in organization effect on the relationship between HRM practices and employee well-being. EDP Sci. 120, 02021 (2021).

Junça Silva, A., Caetano, A. & Rueff, R. Daily work engagement is a process through which daily micro-events at work influence life satisfaction. Int. J. Manpow. 44, 1288–1306 (2023).

Darvishmotevali, M. & Ali, F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: the moderating role of psychological capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 87, 102462 (2020).

Koopman, J. et al. Why and for whom does the pressure to help hurt others? Affective and cognitive mechanisms linking helping pressure to workplace deviance. Pers. Psycho. 73, 333–362 (2020).

Wright, T. A. & Bonett, D. G. Job satisfaction and psychological well-being as nonadditive predictors of workplace turnover. J. Manag. 33, 141–160 (2007).

Nembhard, I. M. & Edmondson, A. C. Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J. Organ. behav. 27, 941–966 (2006).

Ye, Q., Wang, D. & Li, X. Promoting employees’ learning from errors by inclusive leadership: do positive mood and gender matter? Balt J. Manag. 13, 125–142 (2018).

Oh, J., Kim, D. & Kim, D. The impact of inclusive leadership and autocratic leadership on employees’ job satisfaction and commitment in sport organizations: the mediating role of organizational trust and the moderating role of sport involvement. Sustainability 15, 3367 (2023).

Spreitzer, G., Sutcliffe, K., Dutton, J., Sonenshein, S. & Grant A. M. A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organ. Sci. 16, 537–549 (2005).

Spreitzer, G. M. et al. Taking Stock: A Review of More than Twenty Years of Research on Empowerment at Work (Sage, 2008).

Spreitzer, G. & Porath, C. Creating sustainable performance. Harv. Bus. Revw. 90, 92–99 (2012).

Wallace, J. C., Butts, M. M., Johnson, P. D., Stevens, F. G. & Smith, M. B. A multilevel model of employee innovation: Understanding the effects of regulatory focus, thriving, and employee involvement climate. J. Manag. 42, 982–1004 (2016).

Kleine, A. K., Rudolph, C. W. & Zacher, H. Thriving at work: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. behav. 40, 973–999 (2019).

Shore, L. M., Cleveland, J. N. & Sanchez, D. Inclusive workplaces: A review and model. Hum. Resour. Manage. Rev. 28, 176–189 (2017).

Little, L. M., Nelson, D. L., Wallace, J. C. & Johnson, P. D. Integrating attachment style, Vigor at work, and extra-role performance. J. Organ. behav. 32, 464–484 (2011).

Porath, C. L., Gibson, C. B. & Spreitzer, G. M. To thrive or not to thrive: pathways for sustaining thriving at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 42, 100176 (2022).

Liu, Y., Fang, Y. & Chen, N. The impact of inclusive leadership on team innovation: A moderated chain mediation model. J. Bus. Psychol. 40, 1–17 (2024).

Rau, R. Learning opportunities at work as predictor for recovery and health. In Work and Rest: A Topic for Work and Organizational Psychology (eds Sonnentag, S., Perrewé, P. L. & Ganster, D. C.) 158–180 (Psychology Press, 2020).

Fang, Y., Chen, J., Wang, M. & Chen, C. Y. The impact of inclusive leadership on employees’ innovative behaviors: the mediation of psychological capital. Front. Psycho. 10, 1803 (2019).

Li, H., Sun, S. S., Wang, P. & Yang, Y. T. Examining the inverted U-shaped relationship between benevolent leadership and employees’ work initiative: the role of work engagement and growth need strength. Front. Psycho. 13, 699366 (2022).

Lin, X. S., Qian, J., Li, M. & Chen, Z. X. How does growth need strength influence employee outcomes? The roles of hope, leadership, and cultural value. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 29, 2524–2551 (2018).

Bliese, P. D. Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions (eds Klein, K. J. & Kozlowski, S. W. J.) 349–381 (Jossey-Bass/Wiley, 2000).

Liden, R. C., Wang, X. & Wang, Y. The evolution of leadership: past insights, present trends, and future directions. J. Bus. Res. 186, 115036 (2025).

Broeck, A. V., Ferris, D. L., Chang, C. H. & Rosen, C. C. A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. J. Manag. 42, 1195–1229 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all the participants for their valuable cooperation in data collection for this study.

Funding

This study received funding as part of the following programs: National Social Science Foundation of China(20BGL143).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yonghua Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Questionnaire Design, Data Collection, Writing – Original Draft. Yangchun Fang: Methodology, Questionnaire Design, Data Collection. Guibing He: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing. All authors contributed to the conception of this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of management, Zhejiang University of Technology (Approval Number: 2023100902). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. No information that could be used to identify a participant was used in this study. We noted in the introductory statement that the study was to be completed anonymously and that completing the questionnaire in its entirety and submitting it constituted voluntary participation in our survey. The study data are strictly confidential and are for research use only.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Fang, Y. & He, G. The effect of inclusive leadership on employee wellbeing. Sci Rep 15, 39991 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23703-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23703-7