Abstract

Breast cancer (BC) is the most prevalent malignancy among women, and the steadily increasing disease burden has garnered considerable global attention. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) are critical in the initiation and progression of BC. This study aimed to elucidate the associations between diverse PTMs and the prognosis of patients with BC. We collected genes associated with multiple PTMs and evaluated the activity of each PTM using GSVA. We aggregated PTM scores to derive the PTMS and identified differentially expressed genes between the high- and low-PTMS groups. A PTM-related gene signature (PTMRS) was developed based on the optimal combination among 117 machine learning models, and its predictive performance was benchmarked against other published signatures. In addition, we investigated the associations between PTMRS, tumor immunity, and treatment response. Gene expression across different cell types was evaluated using single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses. Gene expression levels in cancerous and paired adjacent noncancerous tissues were validated by PCR. The results of GSVA showed that most of the PTMs were dysregulated in cancer. Tumor immunity levels were elevated in the low-PTMS group compared with the high-PTMS group. The PTMRS comprised five genes: SLC27A2, TNFRSF17, PEX5L, FUT3, and COL17A1. The predictive performance of the PTMRS exceeded that of the clinical profile and 14 other published gene signatures. Patients in the high-PTMRS group exhibited poorer prognosis and reduced anti-tumor immunoreactivity. In addition, patients in the low-PTMRS group showed improved responses to chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Spatial transcriptomics analysis revealed that SLC27A2 exhibited higher expression in malignant spots, whereas COL17A1 and TNFRSF17 showed lower expression in malignant spots. SLC27A2 mRNA expression was elevated in tumor tissues relative to adjacent noncancerous tissues, whereas the mRNA expression levels of the other four genes were decreased. This study reveals the important role of PTMs in BC prognosis and provides new perspectives for the prognostic assessment of BC patients as well as personalized treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC), a major global public health concern that poses a serious threat to women’s health, has garnered considerable attention due to its increasing disease burden. Global cancer statistics show that breast cancer ranks first among female malignant tumors with about 2.3 million new cases per year1, and its incidence is still on the rise, which is predicted to exceed 3 million new cases per year by 20402. Although substantial advances have been achieved in early screening and diagnostic technologies for BC in recent years, challenges such as diagnostic delays and heterogeneity in treatment outcomes persist, adversely affecting patient prognosis3. With the continuous advancement of molecular biology, biomarkers have become pivotal in the diagnosis and prognosis of BC. Recent studies have demonstrated that both individual genes and multigene signatures can serve as biomarkers for BC4,5. High expression of AIMP2 has been shown to be closely associated with poor prognosis in BC patients, whereas AIMP2 knockout inhibits BC proliferation and invasion, suggesting its potential as a prognostic biomarker6. As one of the tools for assessing patient prognosis, gene signature not only predicts disease progression and treatment response, but also provides a scientific basis for the development of individualized treatment plans7,8. Therefore, the establishment and application of robust gene signatures are of great significance for enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of BC and improving patient prognosis.

In recent years, PTMs have emerged as a research focus due to their pivotal roles in the dynamic regulatory networks governing protein function. As a core mechanism of protein functional regulation, PTMs modulate protein activity, stability, and subcellular localization by covalently adding or removing specific chemical groups9. Currently recognized PTMs include acetylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, phosphorylation, and glycosylation10. PTMs are dynamically regulated processes, and this process is usually regulated by three key components: writers, readers, and erasers11. Dysregulated PTMs have been shown to drive malignant phenotypes, including uncontrolled cell proliferation, metabolic reprogramming, and immune evasion, thereby promoting BC progression12. As one of the earliest identified PTMs, dysregulated deubiquitination has been shown to be closely associated with the onset and progression of BC13. Another study reported that sumoylation promotes BC cell progression via cancer-associated fibroblasts14. Moreover, drugs targeting key enzymes involved in various PTMs have been developed and entered clinical evaluation15. Given the critical role of PTMs in cancer, the development of PTM-related gene signatures offers novel perspectives for prognostic assessment and personalized treatment of BC patients.

In this study, we collected genes associated with various PTMs and evaluated their activity. We then aggregated the PTM scores to derive the PTMS and analyzed the immune landscape and biological processes associated with it. We identified differentially expressed genes between the high- and low-PTMS groups and screened prognosis-related genes using univariate Cox regression. Based on these prognosis-related genes, we developed a PTM-related gene signature (PTMRS) within a machine learning framework. In addition, we examined the associations of the PTMRS with tumor immunity, treatment response, and cancer-related biological processes. Finally, we verified the expression levels of the genes in the PTMRS by PCR and spatial transcriptome.

Results

Characterization of the PTMS

PTM-related genes were collected from the GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org/) and previous studies 16, which included 17 different PTMs. The details are as follows: Acetylation (n = 41), Succinylation (n = 7), Malonylation (n = 4), Crotonylation (n = 7), Palmitoylation (n = 27), Myristoylation (n = 5), Ubiquitination (n = 415), Sumoylation (n = 17), Neddylation (n = 22), ISGylation (n = 8), ATG8ylation (n = 12), FAT10ylation (n = 4), UFMylation (n = 5), Methylation (n = 50), Glycosylation (n = 59), Phosphorylation (n = 33), and Deubiquitination (n = 127). We assessed the levels of 17 PTMs in normal and breast cancer patients and summed multiple PCD scores to obtain the PCDS. Most of the PTM scores differed between the two groups except for the deubiquitination score (Fig. 1A). The PTMS were higher in cancer patients compared to normal samples (Fig. 1B). In addition, the levels of PTMS were significantly higher in patients with different clinical characteristics (stage, T, age, N, and M) (Fig. 1C-F).

Comprehensive analysis of the PTMS

Based on the median PTMS, we categorized the patients into a high PTMS group and a low PTMS group. Compared with the low PTMS group, the high PTMS group had higher levels of immune cells (Fig. 2A). Meanwhile, the levels of most immunomodulatory factors were significantly different between the two groups (Fig. 2B). We analyzed the biological processes associated with PTMS. The levels of inflammatory response, TNFA signaling via NFKB, and apoptosis were higher in the low PTMS group (Fig. 3A), while the levels of unfolded protein response, cell cycle, and DNA repair were higher in the high PTMS group (Fig. 3B).

Acquisition of the prognostic gene

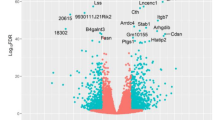

We extracted genes common to DEGs and different datasets. The venn diagrams showed a total of 204 intersecting genes (Fig. 4A). One-way Cox analysis further identified 26 genes with prognostic significance (Fig. 4B).

Construction and validation of the PTMRS

Based on the prognostic genes obtained above, we executed a machine learning framework containing 117 machine learning combinations to screen the best combinations for constructing PTM-related gene siganture. We calculated the C-index and the AUC value for predicting 1-year survival for the 117 combinations in different datasets, and finally chose the combination with the highest average of C-index and AUC value to construct the PTMRS. The combination of RSF + Ridge algorithm ranked the top in the average of C-index and AUC value (Fig. 5A, B), and therefore we chose this combination to construct the PTMRS. Fig. S1A-D shows scatter plots of PTMRS and survival status in different datasets. In TCGA, GSE96058, GSE11121, and GSE131769, the high PTMRS group had a worse prognosis (Fig. 6A-D). In TCGA, the AUC values of PTMRS predicting 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival outcomes were 0.722, 0.714, and 0.692 (Fig. 6E). In GSE96058, the AUC values for PTMRS were 0.662, 0.653, and 0.638 (Fig. 6F). In GSE11121, the AUC values for PTMRS are 0.676, 0.735, and 0.686 (Fig. 6G). In GSE131769, the AUC values for PTMRS were 0.802, 0.643, and 0.771 (Fig. 6H).

Comparison of PTMRS with published gene sigantures

We compared the predictive performance of the PTMRS with 14 published features in different datasets. Since some of the datasets lacked genes for some of the sigantures, we only compared the sigantures that these datasets owned. It is worth noting that the C-index of PTMRS is ranked first in different datasets with high prediction performance (Fig. 7A-D).

Relationship between PTMRS and clinical features

Fig. S2A demonstrates the relationship between clinical characteristics and PCDRS. In the TCGA cohort, PCDRS differed significantly across Status, Stage, T, and Age (Fig. S2B-E). In addition, we further tested the performance of PCDRS by dividing the sample into different subgroups. The results showed that PCDRS was a good predictor of patient prognosis in different subgroups (age < 65, age > = 65, stage I-II, stage III-IV, T1-T2, and T3-T4) (Fig. S2F-K).

Construction of PTM-related nomogram

The results of unifactorial Cox and multifactorial Cox showed that PTMRS was an independent predictor of patient prognosis (Fig. 8A, B). We then constructed a PTM-related nomgram by combining PTMRS and clinical characteristics (Fig. 8C). The results of the ROC curve showed that the nomgram predicted 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival with AUC values of 0.867, 0.808, and 0.797 (Fig. 8D). The calibration curve showed that the nomogram-predicted survival probability was close to the actual survival probability (Fig. 8E). In addition, the C-index and AUC values of the PTMRS were significantly higher than the clinical features (Fig. 8F, G).

Construction of PTM-related nomogram. (A, B) Univariate and multivariate Cox analyses of PTMRS and different clinical characteristics in the TCGA dataset. (C) PTM-related nomogram. (D, E) ROC curves and calibration curves of the nomogram. (F, G) C-index and AUC values for PTMRS and different clinical characteristics.

PTMRS-associated immune landscape

The low PTMRS group had higher levels of immune cells and immunomodulatory factors compared to the high PTMRS group (Fig. 9A, B). The high PTMRS group had higher levels of tumor purity, while the low PCDRS group had higher ESTIMATE score, Immune score, and Stomal score (Fig. 9C, D). Levels of the release of cancer antigens were higher in the high PCDRS group, while levels of the other 6 immune cycle processes were higher in the low PCDRS group (Fig. 9E).

PTMRS-associated immune landscape. (A, B) Differences in the levels of immune cells and immune regulatory factors between the PCDRS groups. (C) Relationship between PTMRS and tumor purity. (D) Relationship between PTMRS and tumor microenvironment score. (E) Relationship between PTMRS and anti-cancer immune cycle. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Association of PTMRS with cancer-related features

The low PTMRS group had higher levels of inflammatory responses (Fig. S3A), whereas the high PTMRS group had higher levels of glycolysis, hypoxia, DNA damage, DNA repair, and cell cycle ( Fig. S3B-F).

Prediction of drug sensitivity

The IPS was higher in the low PCDRS group, which suggests higher sensitivity to immune checkpoint inhibitors in the low PTMRS group (Fig. 10A-D). The sensitivity of docetaxel, epirubicin, fludarabine, vinorelbine, vincristine, gemcitabine, and vinblastine was better in the low PCDRS group (Fig. 10E-J).

Expression validation of core genes

The error rate plot of the RSF algorithm is illustrated in Fig. 11A.The RSF algorithm screened a total of five genes: SLC27A2, TNFRSF17, FUT3, PEX5L, and COL17A1 (Fig. 11B). The expression of SLC27A2 was up-regulated in cancer tissues compared to normal tissues, while the expression of TNFRSF17, PEX5L, FUT3, and COL17A1 was down-regulated in cancer tissues (Fig. 11C-G). Figure 11H demonstrates the expression levels of these genes in different breast cancer cell lines. In addition, we analysed the relationship between genes and different PTMs. The results showed that five key genes were closely associated with most of the PMTs (Fig. S4 A-F).

Enrichment analysis of core genes

We explored the potential molecular mechanisms of the genes by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). SLC27A2 is involved in biological processes including fatty acid metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, and the Notch pathway (Fig. S5A), whereas COL17A1 is involved in biological processes including endothelial mesenchymal transition, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, and glycolysis (Fig. S5B). As shown in Fig. S5C, FUT3 is involved in biological processes including the mTORC1 pathway, glycolysis, and inflammatory response. PEX5L is involved in biological processes including apoptosis, the P53 pathway, and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (Fig. S5D), whereas TNFRSF17 is involved in biological processes including inflammatory response, interferon gamma response, and DNA repair (Fig. S5E).

Single-cell and spatial transcriptome analysis

Figure 12A shows the different cell types in the GSE161529 dataset. Figure 12B and C displays the percentage of cells in GSE161529 and within each sample. TNFRSF17 is abundantly expressed in plasma cells (Fig. 12D), while other genes are less expressed in different cells (Fig. 12E-H). The disease type of the BRCA_BlockASection2 sample is invasive ductal carcinoma, with a spatial resolution of 55 µm. Figure 13A depicts the various cell types in the BRCA_BlockASection2_10x distribution of cell types. Malignant spots showed higher expression of SLC27A2 than non-malignant spots (Fig. 13B). FUT3 expression does not differ significantly between malignant and non-malignant spots (Fig. 13C). PEX5L expression decreased in malignant spots, but not significantly (Fig. 13D). Malignant spots showed decreased expression of TNFRSF17 and COL17A1 (Fig. 13E, F).

Validation of expression levels of genes by PCR

Compared with paraneoplastic tissues, the expression levels of SLC7A2 mRNA were up-regulated in cancer tissues (Fig. 14A), whereas the expression levels of TNFRSF17, FUT3, PEX5L, and COL17A1 mRNA were down-regulated in cancer tissues (Fig. 14B-E).

Comprehensive analysis identifies SLC27A2 as a key gene in PTMRS

We assessed the importance of genes in the PTMRS by RSF and GBM algorithms, and the results showed that SLC27A2 ranked first in the importance ranking (Fig. 15A, B). We evaluated the diagnostic performance of SLC27A2 by ROC curves in different datasets. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) values of SLC27A2 in the TCGA, GSE10780, GSE54002, GSE109169, and GSE134359 datasets were 0.616, 0.697, 0.807, 0.777, and 0.854, respectively (Fig. S6A-E). We validated the mRNA and protein expression of SLC27A2 in different datasets. Compared to normal tissues, the expression of SLC27A2 was significantly upregulated in cancer tissues (Fig. 15C-H). The results of the immunohistochemical pictures show that the SLC27A2 protein stains more darkly in the tumour tissue (Fig. 15I, J).

Comprehensive analysis identifies SLC27A2 as a key gene in PTMRS. (A, B) The prognostic importance of genes revealed by RSF and GBM algorithms. (C-F) Expression of the SLC27A2 in different datasets. (G, H) The immunohistochemical image of SLC27A2 protein in cancer and normal tissues. (I, J) The expression of the SLC27A2 protein in tumour tissues and paracancerous tissues. T, tumour; N, normal; *** p < 0.001.

Discussion

BC is among the most prevalent malignancies in women, with its development and progression governed by multiple molecular mechanisms. Recent studies have increasingly demonstrated that PTMs are closely associated with proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance in BC cells17,18. For instance, elevated phosphorylation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway-associated proteins results in aberrant activation of this signaling pathway, thereby promoting cancer development and progression19. As a newly identified PTM, succinylation has been reported to promote BC cell proliferation and DNA damage repair20. USP36 has been reported to promote BC tumorigenesis and tamoxifen resistance via deubiquitination and ERα signaling pathways21. Another study reported that hypoxia induces downregulation of PGK1 crotonylation in BC cells, thereby promoting glycolysis, inhibiting TCA cycling, and ultimately facilitating BC progression22. Recent studies have demonstrated that various PTMs are interdependent, and their crosstalk plays a critical role in BC development and progression23,24. Therefore, an in-depth investigation into the mechanisms of multiple PTMs in BC may not only elucidate the molecular basis of the disease but also identify novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for personalized patient treatment.

In this study, we collected genes associated with various PTMs and evaluated their levels using GSVA. Most PTMs exhibited significant differences between normal and tumor tissues, indicating that PTM dysregulation is closely linked to BC development and progression. To quantify overall PTM activity, we aggregated individual PTM scores to derive the PTMS. PTMS levels were significantly elevated in tumor tissues compared with normal tissues. All BC samples were then stratified into low- and high-PTMS groups based on the median PTMS. The high-PTMS group exhibited reduced levels of immune cells and immunomodulatory factors relative to the low-PTMS group. Functional enrichment analysis revealed that cancer-suppressive biological processes, including TNFA signaling via NFKB, inflammatory response, and apoptosis, were enriched in the low-PTMS group, whereas cancer-promoting pathways, such as the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, DNA repair, and Myc pathway, were preferentially enriched in the high-PTMS group. Previous studies have demonstrated that aberrant activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and Myc pathways is closely linked to BC development and progression25,26. Collectively, these findings suggest that PTM dysregulation is associated with alterations in immune, inflammatory, and other cancer-related biological processes, providing insight into the interplay between PTMs and tumor progression.

With the rapid development of science and technology, machine learning shows great potential in the medical field. Owing to its powerful data mining capabilities, advantages in nonlinear modeling, and capacity for high-dimensional feature extraction, machine learning offers a novel technological approach for early screening, treatment decision-making, and prognosis prediction of diseases27,28. In this study, prognosis-related genes were extracted from distinct PTMS groups, and PTM-related gene signatures were constructed using 117 combinations encompassing 10 machine learning algorithms. Combinations exhibiting the highest mean C-index and AUC values across multiple datasets were selected to construct the PTMRS. The PTMRS demonstrated robust predictive performance in both the training and external validation sets. Moreover, the PTMRS outperformed clinical features and maintained strong predictive performance across various clinical subgroups. Subsequently, a PTM-associated nomogram incorporating clinical features was constructed, demonstrating even greater predictive accuracy. Calibration curves indicated that the PTM-related nomogram predicted prognosis in accordance with observed outcomes.

Given the pivotal role of PTMs in cancer progression, previous studies have established several gene signatures associated with individual PTMs in BC. For example, a ubiquitination-related gene signature in BC was reported to predict patient prognosis27. Another study reported a glycosylation-related gene signature in BC that predicted overall survival and immune cell infiltration levels29. We compiled 14 published BC gene signatures related to ubiquitination, deubiquitination, immunity, and metabolism. These signatures were reconstructed following the methods described in the original literature, and their predictive performance was compared with that of the PTMRS. The PTMRS exhibited superior predictive performance, achieving the highest C-index across multiple datasets compared with other signatures. These results indicate that PTMRS may serve as a potential biomarker for predicting prognosis in BC patients.

With the advancement of biological technologies, researchers have gradually used gene expression profiles as a means to identify disease-associated molecular markers and as an effective approach for disease onset and recurrence. For example, the 70-Gene Signature Test (70-GS) has been approved by the U.S. government for the early diagnosis of breast cancer and the assessment of recurrence risk30. Similarly, Oncotype DX (21-gene signature) was developed to assess the prognostic risk in breast cancer patients and has been extensively validated in clinical studies31. Although PTMRS has demonstrated promising predictive capabilities across different cohorts, its value in clinical practice remains largely untapped. To fully realize its clinical application potential, further exploration is needed into the complementarity between PTMRS and established clinical biomarkers such as Oncotype DX. Future research should focus on integrating PTMRS with these established biomarkers to enhance the accuracy and reliability of prognosis prediction for breast cancer patients. This integrated approach may provide a more comprehensive and precise prognostic assessment than relying on any single biomarker alone.

With ongoing advances in cancer research, the role of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in cancer progression has become increasingly recognized. The TME comprises tumor cells, immune cells, cytokines, extracellular matrix components, and stromal cells32. The immune components of the TME, including immune cells and immunomodulatory factors, collectively constitute the tumor immune microenvironment, and their interactions influence tumor development33,34. In this study, higher levels of immune cells and immunomodulatory factors were observed in the low-PTMRS group. Moreover, immune and ESTIMATE scores were elevated in the low-PTMRS group, whereas tumor purity was higher in the high-PTMRS group. Furthermore, beyond the release of cancer antigens, other cancer immune cycle processes were elevated in the low-PTMRS group. Previous studies have shown that the high PTMS group with high PTMs activity had lower levels of anticancer immunity, potentially due to immune cell dysfunction induced by multiple PTMs. This phenomenon has been corroborated by recent studies demonstrating that diverse PTMs facilitate immune evasion and promote malignant progression by impairing immune cell function within the TME35,36. Patients in the high-PTMRS group exhibited diminished anti-tumor immunity, which may contribute to their poorer overall survival. In summary, PTMRS may serve as a potential indicator for assessing anticancer immune status in BC patients.

In recent years, the continuous progress of science and technology has made the treatment means of breast cancer more and more abundant. Clinical practice increasingly emphasizes multidisciplinary integrated treatment and the development of individualized therapeutic plans for patients. Recent studies have shown that the third-generation antibody–drug coupling Trastuzumab Duocarmazine significantly reduced the risk of progression in patients with breast cancer37,38. Additionally, Pabolizumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, has been approved for the treatment of patients with triple-negative breast cancer39,. For patients with early-stage BC, breast-conserving surgery is the preferred local treatment, typically followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy40. In this study, we investigated the association between PTMRS and the response to chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Compared with the high-PTMRS group, patients in the low-PTMRS group exhibited greater sensitivity to both chemotherapeutic agents and immune checkpoint inhibitors. These findings suggest that PTMRS may serve as a predictive biomarker for treatment response in BC patients, thereby enhancing guidance for personalized therapeutic strategies.

The PTMRS comprises five genes: SLC27A2, TNFRSF17, PEX5L, FUT3, and COL17A1. Previous studies have elucidated the roles of these genes in various cancers. Reduced expression of SLC27A2 was reported to induce cisplatin resistance in lung cancer stem cells via negative regulation of Bmi1-ABCG2 signaling41. Another study reported that low SLC27A2 expression promoted the progression of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by modulating the cell cycle and apoptosis42. TNFRSF17, a member of the TNF superfamily, promotes breast cancer cell stemness as a co-receptor for BAFF and APRIL43. Furthermore, numerous treatment methods targeting TNFRSF17, such as antibody–drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, and chimeric antigen receptor T cells, have demonstrated promise efficacy in multiple myeloma44. PEX5L is closely associated with peroxisomes, and its genetic variants have been reported to predict survival in non-small cell lung cancer45. Highly expressed COL17A1 has been shown to promote proliferation, migration, and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells via the epithelial-mesenchymal transition pathway and is closely associated with poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer patients46. As a member of the fucosyltransferase family, loss of FUT3 expression has been closely linked to breast cancer development, and subsequent DNA sequencing revealed two variants in the FUT3 promoter region associated with breast cancer progression47. Furthermore, previous studies have indicated that these genes play crucial roles in cancer progression via PTM-related pathways. For example, FUT3 has been shown to promote proliferation, migration, and glucose metabolism in lung adenocarcinoma through activation of the NF-κB pathway48. COL17A1 has been reported to activate mTORC2 signaling, thereby promoting colorectal cancer cell dormancy49. Another study demonstrated that COL17A1 overexpression inhibited breast cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth via inactivation of the AKT/mTOR pathway50. High SLC27A2 expression is strongly associated with poor prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and subsequent experiments revealed that SLC27A2 knockdown suppresses proliferation of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells via the AKT pathway51. Additionally, TNFRSF17 has been confirmed to promote growth of human multiple myeloma and induce immunosuppression within the bone marrow microenvironment via the NF-κB pathway52. These findings suggest that key genes may participate in malignant progression by regulating PTM-related pathways through influencing PTM processes, but the specific mechanisms still require further investigation. In this study, we analyzed the expression levels of these five genes in cancer and paired paracancerous tissues as well as breast cancer cell lines. With the exception of SLC27A2, the expression of all genes was downregulated in tumor tissues, and the expression of cell lines was consistent with the results of the dataset. Finally, the results of the PCR also confirmed the differential expression of these genes.

We evaluated the prognostic significance of these genes using RSF and GBM algorithms, revealing that SLC27A2 was the most prominent among the five genes. Subsequently, we analyzed the expression patterns and diagnostic potential of SLC27A2 across multiple datasets. SLC27A2 exhibited robust diagnostic performance across datasets, effectively distinguishing between healthy individuals and breast cancer patients. Moreover, Western blot analysis of clinical samples further validated the diagnostic potential of SLC27A2. Collectively, these findings indicate that SLC27A2 may serve as a promising diagnostic biomarker for breast cancer.

Of course, our study has some limitations. First, the PTMRS model was constructed using retrospective databases, potentially introducing selection bias and limiting the generalizability of the findings. Second, the model relies on machine learning algorithms, whose black-box nature makes it difficult to fully elucidate its underlying mechanisms. Furthermore, only a limited number of validation experiments were performed in this study. The functional roles of key genes in breast cancer and their potential molecular mechanisms warrant further investigation through additional experimental and clinical validation.

Conclusion

This study revealed the critical role of PTMs in BC prognosis and developed a multi-PTM-related gene signature (PTMRS). The PTMRS exhibits strong predictive power for patient prognosis and treatment response. Overall, this study offers novel insights into prognostic assessment and personalized therapy for patients with BC.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition and processing

The TCGA-BRCA dataset was downloaded from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer. gov/). GSE96058, GSE11121, GSE131769, GSE10780, GSE54002, GSE109169, and GSE134359 were downloaded from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). PTM-related genes were obtained from the GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org/) and from previous studies16, which included 17 different PTMs (Table S1). The details are as follows: Acetylation (n = 41), Succinylation (n = 7), Malonylation (n = 4), Crotonylation (n = 7), Palmitoylation (n = 27), Myristoylation (n = 5), Ubiquitination (n = 415), Sumoylation (n = 17), Neddylation (n = 22), ISGylation (n = 8), ATG8ylation (n = 12), FAT10ylation (n = 4), UFMylation (n = 5), Methylation (n = 50), Glycosylation (n = 59), Phosphorylation (n = 33), and Deubiquitination (n = 127).

Construction of the PTM score (PTMS)

The activities of 17 different PTMs in TCGA-BRCA were evaluated by GSVA analysis, and the activities of the different PTMs in each sample were summed to constitute the PTMS. Based on the median PTMS, we divided the samples from TCGA into high and low PTMS groups. We analyzed the immune landscape as well as biological processes associated with PCDS. Immune cell levels were assessed using the “deconvo_tme” function in the “IOBR” R package, which includes CIBERSORT53, EPIC54, TIMER55, MCPcounter56, quantiseq57, xCell58, and ESTIMATE59 algorithms. Supplementary Tables S2 and S3 present the cell annotation genes in the xCell and EPIC algorithms. We evaluated the correlation between PCDRS and immunomodulatory factors (immunosuppressants, immunostimulants, major histocompatibility complex molecules, chemokines, and chemokine receptors). In addition, we analyzed the association of PTMS with HALLMARK signatures, which were downloaded from the MsigDB database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp).

Screening of prognosis-related genes

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in normal and tumor tissues in TCGA were obtained by limma package with the screening criteria of adj.p < 0.05 and logFC ≥ 1. Meanwhile, we extracted differentially expressed genes (PTMSRGs) between different PTMS groups with the screening criteria of adj.p < 0.05 and logFC ≥ 2. Subsequently, we extracted differentially expressed genes (DEGs) shared across different datasets and PTMSGs as protein post-translational modification-related genes (PTMRGs), and screened for prognostically relevant PTMRGs using univariate Cox analysis.

Construction of the PTM-related gene signature

Referring to the methodology in a previous study60, a machine learning framework using 117 combinations consisting of 10 machine learning algorithms was constructed on the TCGA-BRCA, GSE96058, GSE11121, and GSE131769 datasets. The 10 machine learning algorithms include RSF, Enet, StepCox, Ridge, Survival-SVM, plsRCox, Lasso, CoxBoost, and SurperPC. Due to their ability to screen features, Lasso, RSF, and CoxBoost can be combined with other algorithms to construct prognostic models. We integrated 117 combinations into the machine learning framework and performed tenfold cross-validation. For the parameters of these algorithms, please refer to Supplementary Table S4. We calculated the C-index of each machine learning combination in the four datasets, and finally chose the machine learning combination with the highest average of AUC value and C-index in the four datasets to construct the gene signature (PTMRS). The samples were divided into high PTMRS and low PTMRS groups based on the median PTMRS, and the survival outcomes of the patients in the low-risk and high-risk groups were analyzed by Kaplan–Meier curves. In addition, ROC curves for PTMRS predicting 1-, 3- and 5-year survival were plotted.

Comparison of PTMRS with published gene signatures

We collected 13 published gene sigantures (Table S5) in breast cancer, which are related to various aspects of ubiquitination, deubiquitination, metabolism, and tumor microenvironment. We constructed these signatures in different datasets and compared the performance of these signatures with the PTMRS.

Construction of the PTM-related nomogram

The nomogram is composed of the PTMRS and other clinical features. We also plotted 1-, 3-, and 5-year ROC curves and calibration curves for the nomogram. In addition, we compared the predictive performance of the nomogram with other clinical features.

Analysis of immune cell infiltration

The “IOBR” R package was used to assess immune cell infiltration in the high- and low-PTMRS groups. In addition, the correlation of the PTMRS with immunomodulatory factors, tumor microenvironment scores, and anticancer immune cycles was analyzed.

Assessment of cancer-related characteristics

We downloaded cancer related features from CancerSEA (http://biocc.hrbmu.edu.cn/CancerSEA/) and analyzed their differences between the various PTMRS groups. Additionally, we explored potential molecular mechanisms involving key genes through gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA).

Drug sensitivity analysis

Drug sensitivity analyses were performed using the ‘oncoPredict’ R package, which uses the drug data from the GDSC v2 and CTRP v2 databases. The half-maximal inhibition concentrations (IC50) were used to express drug sensitivity. In addition, we downloaded data on immunophenotype scores (IPS) of BC patients from TCIA (https://tcia.at/) and compared their differences between subgroups.

Single-cell and spatial transcriptome analysis

The expression levels of the key genes in different cells in the GSE161529 dataset were analyzed using the TISCH2 database (http://tisch.compbio.cn/home/). Supplementary Table S6 presents sample information from GSE161529. The spatial distribution of key genes in BRCA_BlockASection2_10x was analyzed by SpatialTME database (https://www.spatialtme.yelab.site/).

Validation of expression levels of key genes

We analyzed the expression levels of key genes in cancer and paired paracancerous tissues in TCGA-BRCA, and analyzed the expression levels of key genes in different breast cancer cell lines in the CCLE database (https://depmap.org/portal/).

Comprehensive analysis of the SLC27A2

We assessed the importance of the genes through GBM and RSF algorithms and selected the most important gene (SLC27A2) for further study. We evaluated the diagnostic performance of the SLC27A2 in the TCGA , GSE10780, GSE54002, GSE109169, and GSE134359 datasets by ROC curves. In addition, we downloaded the immunohistochemical images of SLC27A2 in the HPA database (https://www.proteinatlas.org/).

RT-PCR

We performed BLAST alignment and evaluated the stability of GAPDH and ACTB in our experimental system. We selected the more stable GAPDH as the housekeeping gene for this study. The primer information of the gene was shown in Table S7. The BLAST alignment results for the PCR primers are shown in Table S8. The Research Ethics Committee of Shanxi Provincial Cancer Hospital has approved this study (Grant No.:KY2023163). Tissue samples of breast cancer patients were provided by Shanxi Provincial Cancer Hospital, and total RNA was extracted from the tissues using Trizol kit. Takara kit was used for reverse transcription and Real Time PCR reaction. Finally, we calculated the relative expression of gene mRNA with GAPDH as an internal reference gene.

Western blotting

Tumour or paracancerous tissue was lysed using RIPA buffer , and protein concentration was measured using the BCA Protein Assay Kit. Proteins were separated using an SDS-PAGE polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight, after which the membranes were washed using TBST and incubated with labelled secondary antibodies for half an hour. Primary antibodies used included anti-SLC27A2 (1:1000, mouse) and anti-GAPDH (1:100,000, rabbit). The target bands were detected using a ChemiScope 6100 chemiluminescent imaging system and photographed on a gel imaging system. The grey scale values of the proteins were determined using the ImageJ software (version 1.54p), and the relative expression of the proteins was calculated as the ratio of the target protein to the internal reference protein.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses and statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.4.0). The Wilcoxon test was used to compare data between two groups, and the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare data between multiple groups. p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Data availability

The dataset provided in this study can be downloaded in the online website. TCGA-BRCA: https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/. GEO: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J Clinicians 74, 229–263 (2024).

Coles, C. E. et al. The Lancet Breast Cancer Commission. The Lancet 403, 1895–1950 (2024).

Nolan, E., Lindeman, G. J. & Visvader, J. E. Deciphering breast cancer: from biology to the clinic. Cell 186, 1708–1728 (2023).

Cursano, G. et al. Trop-2 as an Actionable Biomarker in Breast Cancer. CG 24, 129–131 (2023).

Hussain, M. S. et al. Beyond the Genome: Deciphering the Role of MALAT1 in Breast Cancer Progression. CG 25, 343–357 (2024).

Qiu, J. et al. Pan-cancer Analysis Identifies AIMP2 as a Potential Biomarker forBreast Cancer. CG 24, 307–329 (2023).

Oliveira, L. J. C., Amorim, L. C., Megid, T. B. C., De Resende, C. A. A. & Mano, M. S. Gene expression signatures in early breast cancer: Better together with clinicopathological features. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 175, 103708 (2022).

Lemij, A. A. et al. Gene expression signatures in older patients with breast cancer: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 181, 103884 (2023).

Jensen, O. N. Interpreting the protein language using proteomics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7, 391–403 (2006).

Li, Z. et al. Functions and mechanisms of non-histone post-translational modifications in cancer progression. Cell Death Discov. 11, 125 (2025).

Hao, B. et al. Substrate and Functional Diversity of Protein Lysine Post-translational Modifications. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 22, qzae019 (2024).

Liu, J., Wang, Q., Kang, Y., Xu, S. & Pang, D. Unconventional protein post-translational modifications: the helmsmen in breast cancer. Cell Biosci 12, 22 (2022).

Kong, L. & Jin, X. Dysregulation of deubiquitination in breast cancer. Gene 902, 148175 (2024).

Martínez-López, A. et al. SUMOylation regulates the aggressiveness of breast cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Oncol. 48, 437–453 (2025).

Zhai, L., Chen, K., Hao, B. & Tan, M. Proteomic characterization of post-translational modifications in drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol Sin 43, 3112–3129 (2022).

Zhang, P. et al. Novel post-translational modification learning signature reveals B4GALT2 as an immune exclusion regulator in lung adenocarcinoma. J Immunother Cancer 13, e010787 (2025).

Neagu, A.-N. et al. Bio-Pathological Functions of Posttranslational Modifications of Histological Biomarkers in Breast Cancer. Molecules 29, 4156 (2024).

Miao, C. et al. Post-translational modifications in drug resistance. Drug Resist. Updates 78, 101173 (2025).

Miricescu, D. et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Breast Cancer: From Molecular Landscape to Clinical Aspects. IJMS 22, 173 (2020).

Mu, R. et al. Role of succinylation modification.

Zhuang, T. et al. USP36 promotes tumorigenesis and tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer by deubiquitinating and stabilizing ERα. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 43, 249 (2024).

Guo, Z. et al. Hypoxia-induced downregulation of PGK1 crotonylation promotes tumorigenesis by coordinating glycolysis and the TCA cycle. Nat Commun 15, 6915 (2024).

Bejan, D. S., Lacoursiere, R. E., Pruneda, J. N. & Cohen, M. S. Ubiquitin is directly linked via an ester to protein-conjugated mono-ADP-ribose. EMBO J 44, 2211–2231 (2025).

Wei, B., Yang, F., Yu, L. & Qiu, C. Crosstalk between SUMOylation and other post-translational modifications in breast cancer. Cell Mol Biol Lett 29, 107 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway: An important driver and therapeutic target in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer 31, 539–551 (2024).

Stipp, M. C. & Acco, A. c-Myc-targeted therapy in breast cancer: A review of fundamentals and pharmacological Insights. Gene 941, 149209 (2025).

Ma, H.-Y. et al. The clinical prediction value of the ubiquitination model reflecting the microenvironment infiltration and drug sensitivity in breast cancer. J. Cancer 16, 784–801 (2025).

Ahmad, I. & Alqurashi, F. Early cancer detection using deep learning and medical imaging: A survey. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 204, 104528 (2024).

Gao, S., Wu, X., Lou, X. & Cui, W. Identification of a prognostic risk-scoring model and risk signatures based on glycosylation-associated cluster in breast cancer. Front. Genet. 13, 960567 (2022).

Tsai, M. et al. Association of 70-gene signature assay findings with physicians’ treatment guidance for patients with early breast cancer classified as intermediate risk by the 21-gene assay. JAMA Oncol 4, e173470 (2018).

Paik, S. et al. A Multigene Assay to Predict Recurrence of Tamoxifen-Treated, Node-Negative Breast Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine (2004).

Shah, D. D. et al. Tumor microenvironment: recent advances in understanding and its role in modulating cancer therapies. Med Oncol 42, 117 (2025).

Fu, T. et al. Spatial architecture of the immune microenvironment orchestrates tumor immunity and therapeutic response. J Hematol Oncol 14, 98 (2021).

Binnewies, M. et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med 24, 541–550 (2018).

Duan, X. et al. The role of histone post-translational modifications in cancer and cancer immunity: functions, mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Front. Immunol. 15, 1495221 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Novel post-translational modifications of protein by metabolites with immune responses and immune-related molecules in cancer immunotherapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 277, 133883 (2024).

Turner, N. et al. Trastuzumab duocarmazine in pretreated human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive advanced or metastatic breast cancer: an open-label, randomized, phase III Trial (TULIP). JCO 43, 513–523 (2025).

Araghi, M. et al. Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab monotherapy or combined therapy in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Curr Gene Ther 25, 72–88 (2025).

Cardoso, F. et al. Pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in high-risk, early-stage, ER+/HER2− breast cancer: a randomized phase 3 trial. Nat Med 31, 442–448 (2025).

Cardoso, F. et al. Early breast cancer: ESMO clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1194–1220 (2019).

Su, J. et al. Reduced SLC27A2 induces cisplatin resistance in lung cancer stem cells by negatively regulating Bmi1-ABCG2 signaling. Mol. Carcinog. 55, 1822–1832 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. SLC27A2 is a potential immune biomarker for hematological tumors and significantly regulates the cell cycle progression of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BMC Med. Genomics 17, 105 (2024).

Pelekanou, V. et al. BCMA (TNFRSF17) induces APRIL and BAFF mediated breast cancer cell stemness. Front. Oncol. 8, 301 (2018).

Zheng, H. et al. BCMA-targeted therapies for multiple myeloma: latest updates from 2024 ASH annual meeting. J. Hematol. Oncol. 18, 23 (2025).

Chen, A. S. et al. Genetic variants in DDO and PEX5L in peroxisome-related pathways predict non-small cell lung cancer survival. Mol. Carcinog. 61, 619–628 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. COL17A1 facilitates tumor growth and predicts poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 632, 1–9 (2022).

Nascimento, J. C. F. D. et al. Fut3 role in breast invasive ductal carcinoma: Investigating its gene promoter and protein expression. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 99, 409–415 (2015).

Lin, L. et al. FUT3 facilitates glucose metabolism of lung adenocarcinoma via activation of NF-κB pathway. BMC Pulm. Med. 23, 436 (2023).

Lin, J. et al. Collagen XVII promotes dormancy of colorectal cancer cells by activating mTORC2 signaling. Cell. Signal. 120, 111234 (2024).

Lothong, M. et al. Collagen XVII inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation and growth through deactivation of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 16, e0255179 (2021).

Lu, L. et al. High expression of SLC27A2 predicts unfavorable prognosis and promotes inhibitory immune infiltration in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Transl. Oncol. 45, 101952 (2024).

Tai, Y.-T. et al. APRIL and BCMA promote human multiple myeloma growth and immunosuppression in the bone marrow microenvironment. Blood 127, 3225–3236 (2016).

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods 12, 453–457 (2015).

Racle, J., De Jonge, K., Baumgaertner, P., Speiser, D. E. & Gfeller, D. Simultaneous enumeration of cancer and immune cell types from bulk tumor gene expression data. Elife 6, e26476 (2017).

Li, B. et al. Comprehensive analyses of tumor immunity: implications for cancer immunotherapy. Genome Biol 17, 174 (2016).

Becht, E. et al. Estimating the population abundance of tissue-infiltrating immune and stromal cell populations using gene expression. Genome Biol 17, 218 (2016).

Finotello, F. et al. Molecular and pharmacological modulators of the tumor immune contexture revealed by deconvolution of RNA-seq data. Genome Med 11, 34 (2019).

Aran, D., Hu, Z. & Butte, A. J. xCell: digitally portraying the tissue cellular heterogeneity landscape. Genome Biol 18, 220 (2017).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun 4, 2612 (2013).

Liu, H. et al. Mime: A flexible machine-learning framework to construct and visualize models for clinical characteristics prediction and feature selection. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 23, 2798–2810 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of the GEO and TCGA databases.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from the Basic Research Program of Shanxi Province (Free Exploration Category) [Grant number: 202103021224428].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LZ: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. LS: conceptualization, resources, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. HW: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—review & editing. WT: conceptualization, visualization, writing—review & editing. JX: data curation, methodology, writing—review & editing. BZ: visualization, data curation, validation, writing—original draft. YC: funding acquisition, software, validation, writing—review & editing. LH: software, supervision, validation, writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shanxi Province Cancer Hospital (Grant No. KY2023163). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, L., Song, L., Wang, H. et al. Integrating machine learning and experimental validation identifies a post-translational modification gene signature for prognosis and treatment response in breast cancer. Sci Rep 15, 39962 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23772-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23772-8